Higher education research in the Asia-Pacific

Futao Huang and Simon Marginson

It is a time of tremendous growth in higher education in East and Southeast Asia. In the two

decades leading up to 2013 the worldwide Gross Tertiary Education Ratio (GTER) moved

from 15 to 33 per cent. Nevertheless, the growth of Asia-Pacific regional engagement in

higher education was even more impressive. By 2013 the rate of participation in colleges

and universities in all East Asian nations except China was at 60 per cent plus (UNESCO,

2016). China is almost certain to exceed the official target of 40 per cent by 2020.

The output of research science is growing with equal rapidity, in China, South Korea,

Taiwan, Singapore, Thailand and Malaysia. South Korea is now the world’s largest investor

in R&D as a proportion of GDP. On present trends, China will pass the United States in total

expenditure on R&D and output of published science by 2025. The United States remains by

far the largest producer of high citation science, but China is beginning to close the gap in

the Physical Sciences, especially Chemistry, Engineering and Computing (NSF, 2014).

Japan developed mass higher education and scientific output well ahead of the rest of East

Asia. Though its science system is not growing like the rest of the region at present, it is

especially strong in domains such as Physics and Mathematics, and a range of technologies.

With science output expanding, the number of World-Class Universities in East and

Southeast Asia, as measured by position in global ranking systems, is also on the rise.

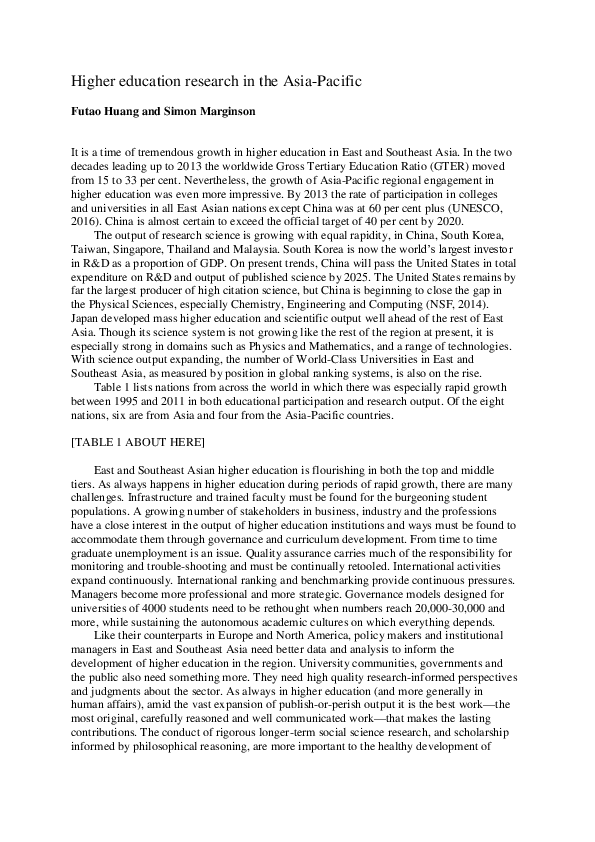

Table 1 lists nations from across the world in which there was especially rapid growth

between 1995 and 2011 in both educational participation and research output. Of the eight

nations, six are from Asia and four from the Asia-Pacific countries.

[TABLE 1 ABOUT HERE]

East and Southeast Asian higher education is flourishing in both the top and middle

tiers. As always happens in higher education during periods of rapid growth, there are many

challenges. Infrastructure and trained faculty must be found for the burgeoning student

populations. A growing number of stakeholders in business, industry and the professions

have a close interest in the output of higher education institutions and ways must be found to

accommodate them through governance and curriculum development. From time to time

graduate unemployment is an issue. Quality assurance carries much of the responsibility for

monitoring and trouble-shooting and must be continually retooled. International activities

expand continuously. International ranking and benchmarking provide continuous pressures.

Managers become more professional and more strategic. Governance models designed for

universities of 4000 students need to be rethought when numbers reach 20,000-30,000 and

more, while sustaining the autonomous academic cultures on which everything depends.

Like their counterparts in Europe and North America, policy makers and institutional

managers in East and Southeast Asia need better data and analysis to inform the

development of higher education in the region. University communities, governments and

the public also need something more. They need high quality research-informed perspectives

and judgments about the sector. As always in higher education (and more generally in

human affairs), amid the vast expansion of publish-or-perish output it is the best work—the

most original, carefully reasoned and well communicated work—that makes the lasting

contributions. The conduct of rigorous longer-term social science research, and scholarship

informed by philosophical reasoning, are more important to the healthy development of

�2

higher education than another round of student satisfaction surveys; though the regular

student surveys have their place too, as part of a culture of continuous improvement.

Higher education across the Asia-Pacific needs a networked scholarly community of

researchers on higher education, capable of both immediately useful applied research when

needed, and sustained, reflective and critical work that lifts the conversation on higher

education and encourages sharper innovation. The development of higher education studies

in the region long lagged behind the explosive growth of educational participation and

research science, but recently the higher education scholars have been catching up.

The papers for this Special Issue of International Journal of Educational Development

evolved from presentations at the third conference of the Higher Education Research

Association (HERA) in Taipei, Taiwan, in 21-22 May 2015. The United States has ASHE

(Association for Studies in Higher Education), and the United Kingdom has SRHE (Society

for Research into Higher Education). Both are fairly large scholarly conferences given that

they service a specialist research field such as higher education studies, reflecting the size of

the networks in the English-speaking countries and especially the scale of American higher

education. Europe has the Consortium of Higher Education Researchers (CHER), which is a

smaller scholarly conference, with longer time spent on each paper than at ASHE. Of these

three regular meetings outside Asia, HERA is probably closest in form to CHER. As at

CHER, the papers at HERA reflect a broad range of research interests within the higher

education field, and in their methods range from big policy picture making and reflection to

closely structured statistically-based analysis and micro interview work.

The 2015 HERA conference in Taipei, and also the 2016 HERA conference in Hong

Kong, brought together significant groups of participants from China, Hong Kong SAR,

Taiwan, Japan—which has the largest and longest established community of researchers on

higher education—and South Korea, as well as scholars from other countries and world

regions. Most leading scholars of higher education based in East and Southeast Asia are

active in HERA. Researcher-scholars who participate in HERA know that it is a young

organisation with much developing to do before its deliberations achieve the quality and

range of the longer established conferences in other regions. All the same, a promising start

has been made. Ultimately HERA’s development will be carried forward by the advances of

higher education in the region, the need of all countries for closer cooperation, and the value

that participants derive from exchange with each other. Knowledge is always a collaborative

process and each of us achieves what we achieve only because of the work of many others.

In his opening paper, developed from a keynote address to HERA 2015, Simon

Marginson reflects on the longstanding policy question of the relationship between higher

education, social mobility and social equality/inequality. He reviews the extraordinary

increase in income inequality in the United States since 1980, concluding that

(nothwithstanding the assumptions of human capital theory) higher education was not the

driver of the trend to inequality. However, the highly stratified and tuition differentiated

American higher education sector, where the top institutions have great strengths but the

educational quality and labour market power of lower tier institutions appears to be in

decline, is compatible with a highly unequal income structure and contributes to the

reproduction of social inequality. While expectations that higher education by itself can

foster a more equal society have been overstated, under certain circumstances egalitarian

reforms in higher education can make a difference. These reforms are more effective when

coupled with a progressive taxation system and moderate wage differentials in the

workplace, as in the Nordic countries. In fostering a more equal higher education system in

which both World-Class Universities (WCUs) and mass higher education institutions are of

good quality, it is important to maintain relatively modest differences in status and resources

between top tier WCUs and other institutions. However, East Asian countries have two

�3

advantages enabling them to avoid the worst excesses of American inequality—the profound

commitment to educational formation in the family, extending to poor as well as middle

class families, and the close attention to education policy by East Asian governments.

In their survey-based paper on faculty attitudes to institutional governance in Taiwan,

Sheng-Ju Chan and Chia-Yu Yang identify a standardized pattern of governance and reach

conclusions that may surprise some—bureaucratic and collegial modes of governance, not

corporate forms, are dominant; while bureaucratic and corporate governance is associated

with the greatest organisational effectiveness at the institutional level. Nevertheless, as they

normally do elsewhere, faculty in Taiwan express a strong commitment to collegial forms.

Dian-Fu and Ni-Jung Lin use innovative analytical and data presentation methods to

discuss internationalisation in higher education in Taiwan, presenting the outcomes of a

survey of 612 staff and students. They find that there are gaps between the expectations

attached to internationalisation and the resources to practice it, expected and actual results,

and student and faculty support for internationalisation.

In their survey on strategic planning in universities in China, Juan Hu, Hao Liu,

Yingxia Chen and Jiali Qin summarize the findings in relation to awareness of strategic

planning, the types of strategic plans used, the coverage of plan text, the within-university

groups with the main influence in planning and the approach taken to evaluation of

planning. Higher tier higher education institutions (HEIs) tend to be more ambitious in their

plans and their plans are more driven by internal constituencies, whereas vocational and

private HEIs are to a greater degree influenced by students, alumni, and external specialists.

The authors also reflect on the highly stratified higher education system in China.

Huang Futao presents the data on university governance in four-year universities in

China and Japan that were generated in a major cross-national academic survey conducted

using a common questionnaire in 2011-2012. Both countries have been influenced by

entrepreneurialism and the new public management but they do not always replicate the

American model. Neither shared governance, corporate/entrepreneurial approaches, nor

flexible/learning architectures have dominated the two countries. The two national systems

also vary with each other. China is more characterized by a top-down style while Japan is

more concerned with a bottom-up one. The evolution of governance of higher education in

the two countries cannot be satisfactorily explained in terms of massification, or other

generic notions in the research literature. Rather, the specificities of each country, and the

differences between them, must be explained in terms of the academic origins, traditions,

cultural values, and especially the current political and social systems of China and Japan.

Ka Ho Mok and Jin Jiang critically reflect on massification and marketization of higher

education in the East Asian region, and the development of graduate labour markets, noting

that an increasing enrolment in higher education does not always promote upward social

mobility. Often it can intensify inequality in education. The authors supply striking graphs

and tables to illustrate problems becoming apparent in many countries of a mismatch

between university education and the labour market, as and stagnant social mobility. Again

this demonstrates that higher education cannot be expected to be the great equaliser in

societies in which the structures of the labour market, rewards to labour, and ever increasing

capital flows are fostering growing social stratification.

In a review that captures key features in the recent history of government and policy in

higher education in South Korea, Jung Cheol Shin, one of the chief founders of HERA,

explains the evolution of the quality assurance system. The system underwent three major

changes in 1982, 1994, and 2008. The successive modifications in quality assurance

responded to shortfalls in the prior quality assurance system rather than international

pressures. Although growing similarities at global level, in quality assurance, have become

evident, in Korea the local prism filters the external pressures.

�4

Wen Wen, Die Hu, Jie Hao discuss international student mobility into China, where the

nation is positioning itself for a larger global role as a provider of education for students

from East and Southeast Asian countries, Africa and around the world. They draw on their

own system-level analysis, a nation-wide census of international students, and the Survey of

International Students’ Experience and Satisfaction, to reflect on the international student

experience in China. Challenges for international students include limited English-language

resources, inadequate student-faculty interaction on campus, and difficulties in sociocultural adjustment.

Reiko Yamada provides an overview of changes in Japanese higher education policy

since the 1990s, highlighting reductions in government funding and the increase in

accountability requirements; and focusing especially on the regulation of private education.

At the same time that corporatisation reforms were introduced into the national universities,

government control of private universities was increased, as evidenced by the framework for

providing financial assistance, which includes competitive finance aimed at improving

governance and promoting educational reform. The 2013 survey conducted by The

Promotion and Mutual Aid Corporation for Private Schools of Japan highlights inequalities

between universities and reveals that private universities’ assessments of their financial

situations differ depending on size, history, location, and fields of study at the university.

Keiichiro Yoshinaga makes a distinctive contribution to the global literature on mergers

in higher education, focusing on departments of veterinary medicine in Japan. The old

paradigm of research-related training has given way to a more practical training because of

changing social needs. At the same time faculty members have built critical mass by

initiating mergers across university boundaries, often against the wishes of university

leaders. Professional associations, local communities and the Ministry of Education have all

influenced the merger process. International standards have been used as a rationale. The

outcome has been a particular kind of merger, that of joint undergraduate degree programs,

in which two departments combine with each remaining in its original university. This has

partially addressed issues of size and clinical training.

The range of material in this issue of International Journal of Educational Development

is a sign not only of the diverse scholarship and research on higher education in the region,

but on the fertility and range of higher education studies itself as a field of knowledge.

Higher education studies is a cross-disicplinary field that draws variously on sociology,

policy studies, economics, psychology, anthropology and other social science. It uses

quantitative and qualitative analysis, historical synthesis that combines material from a range

of sources, and is the platform for much policy advice and formation. It joins practical issues

of the running of systems and institutions to larger perspectives on the philosophy and

purposes of higher education, the social nature of knowledge, and the place of universities in

national and global political economy, societies and cultural relations. It is heterogeneous,

but that diversity, when combined with the strong focus on practical institutions and systems

that has always been a chief driver of the field, is the source of its intellectual potential and

its capacity to contribute to reflexive improvement in higher education.

In short, we can be confident that in future years many more good papers will come

from the Higher Education Research Association’s proceedings and from the work of

scholar-researchers from the Asia-Pacific region. We sincerely thank our authors for their

careful work on the revised papers, and the journal editor, Dr. Stephen P. Heyneman, for

providing scholars in the region with the opportunity to share these papers with the global

scholarly community interested in developments in East and Southeast Asia.

Hiroshima and London, 21 July 2016.

�5

References

National Science Foundation. (2014). Webcapar data portal. Accessed from:

https://ncsesdata.nsf.gov/webcaspar/

United Nations Educational, Social and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), 2015. UNESCO

Institute for Statistics data on education. http://data.uis.unesco.org/

�6

Table 1.

Nations which exceptional growth in both enrolments in

tertiary education and the number of published journal papers

in science, 1995-2011.

National system

Iran

China

Tunisia

Thailand

Malaysia

Turkey

Singapore

Brazil

Annual rate of

growth in tertiary

enrolment

%

9.9

11.8

8.2

4.8

10.5

7.7

6.7

8.8

Source: UNESCO, 2016; NSF, 2014

Annual rate of

growth in number

of journal papers

%

23.5

15.4

13.0

12.7

11.5

10.4

9.0

8.7

�

Futao Huang

Futao Huang