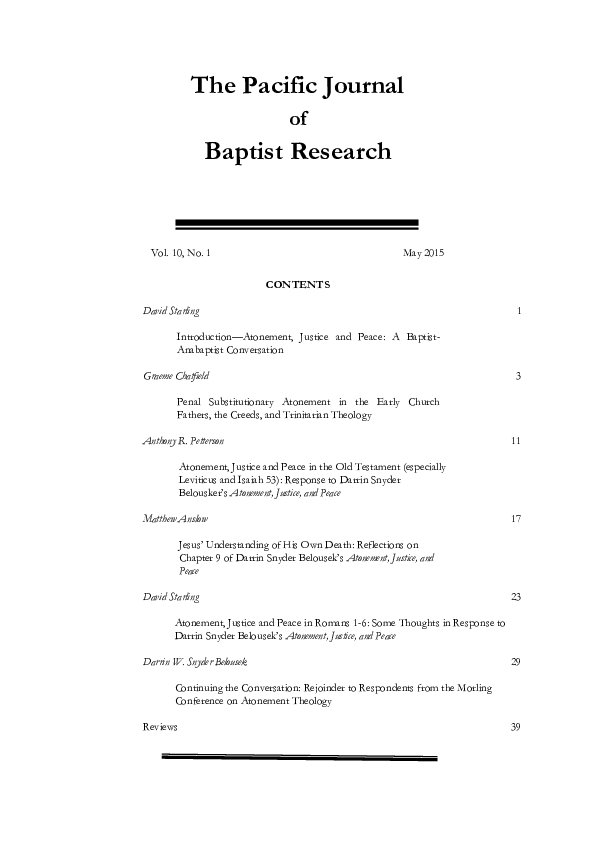

The Pacific Journal

of

Baptist Research

Vol. 10, No. 1

May 2015

CONTENTS

David Starling

1

Introduction—Atonement, Justice and Peace: A BaptistAnabaptist Conversation

Graeme Chatfield

3

Penal Substitutionary Atonement in the Early Church

Fathers, the Creeds, and Trinitarian Theology

Anthony R. Petterson

11

Atonement, Justice and Peace in the Old Testament (especially

Leviticus and Isaiah 53): Response to Darrin Snyder

Belousker’s Atonement, Justice, and Peace

Matthew Anslow

17

Jesus’ Understanding of His Own Death: Reflections on

Chapter 9 of Darrin Snyder Belousek’s Atonement, Justice, and

Peace

David Starling

23

Atonement, Justice and Peace in Romans 1-6: Some Thoughts in Response to

Darrin Snyder Belousek’s Atonement, Justice, and Peace

Darrin W. Snyder Belousek

29

Continuing the Conversation: Rejoinder to Respondents from the Morling

Conference on Atonement Theology

Reviews

39

�The Pacific Journal

of

Baptist Research

ISSN 1177-0228

Editor

Dr Myk Habets

Carey Baptist College,

PO Box 12149,

Auckland, New Zealand

myk.habets@carey.ac.nz

Associate Editors

Rev Andrew Picard

Dr John Tucker

Book Reviews Editor

Dr Sarah Harris

Carey Baptist College,

PO Box 12149,

Auckland, New Zealand

sarah.harris@carey.ac.nz

Editorial Board

Prof Paul Fiddes

Regent’s Park College

Dr Steve Harmon

Gardner-Webb University

Dr Steve Holmes

St. Andrews

Dr Donald Morcom

Malyon College

Dr Michael O’Neil

Vose Seminary

Dr Frank Rees

Whitley College

Dr Jason Sexton

University of SoCal

Dr David Starling

Morling College

Dr Martin Sutherland

Laidlaw College

Dr Brian Talbot

Dundee, Scotland

Contributing Institutions

Carey Baptist College (Auckland, New Zealand)

Malyon College (Brisbane, Australia)

Whitley College (Melbourne, Australia)

Morling College (Sydney, Australia)

Vose Seminary (Perth, Australia)

The Pacific Journal of Baptist Research (PJBR) is an open-access online journal which aims to

provide an international vehicle for scholarly research and debate in the Baptist tradition,

with a special focus on the Pacific region. However, topics are not limited to the Pacific

region, and all subject matter potentially of significance for Baptist/Anabaptist communities

will be considered. PJBR is especially interested in theological and historical themes, and

preference will be given to articles on those themes. PJBR is published twice-yearly in May

and November. Articles are fully peer-reviewed, with submissions sent to international

scholars in the appropriate fields for critical review before being accepted for publication.

The editor will provide a style guide on enquiry. All manuscript submissions should be

addressed to the Senior Editor: myk.habets@carey.ac.nz.

URL: http://www.baptistresearch.org.nz/the-pacific-journal-of-baptist-research.html

All business communications

Dr John Tucker

Carey Baptist College

PO BOX 12149

Auckland

New Zealand

Fax: +64 9 525 4096

Email: john.tucker@carey.ac.nz

The Pacific Journal of Baptist Research is sponsored by the N.Z. Baptist Research and Historical Society and

the R.J. Thompson Centre for Theological Studies at Carey Baptist College.

© Pacific Journal of Baptist Research, All Rights Reserved, Auckland, New Zealand

��Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

1

INTRODUCTION

ATONEMENT, JUSTICE, AND PEACE: A BAPTISTANABAPTIST CONVERSATION

DAVID STARLING

Morling College

Sydney, Australia

davids@morling.edu.au

The articles in this issue of PJBR all derive from a symposium at Morling College, Sydney, in May 2014,

organized by the Anabaptist Association of Australia and New Zealand. The principal speaker on the day

was the North American Anabaptist philosopher, Darrin Snyder Belousek, who presented lectures based

on the argument in his book, Atonement, Justice, and Peace: The Message of the Cross and the Mission of the Church.

Short responses to Belousek’s lectures were offered by local Baptist and Anabaptist scholars and their

papers (revised and edited in light of the conversations on the day) make up four of the five articles that

follow.

Graeme Chatfield’s article is a revised version of the paper that he offered at the symposium in

response to Belousek’s lecture on “Jesus’ Death and Christian Tradition: Ancient Creeds and Trinitarian

Theology.” In it, he explores the relationship between Penal Substitutionary Atonement (PSA) theory and

the teachings of the early church, concluding that the writings of the fathers and the language of the

creeds anticipate the themes of PSA but do not require it as the only possible theory consistent with

Christian orthodoxy: new cultural contexts may occasion the formulation of new theories. In the

formulation of such theories, Chatfield argues, the contemporary cultural antipathy toward hierarchical

institutions lends itself to a congregational hermeneutic along the lines of that argued for in the early

writings of Balthasar Hubmaier.

Anthony Petterson’s article responds to Belousek’s lecture on “Jesus’ Death and the Old

Testament: Atoning Sacrifice and the Suffering Servant,” focusing on Belousek’s interpretation of the

atonement language of Leviticus and the sufferings of the Servant in Isaiah 53, and his claims about the

relationship between sin, wrath and punishment within the Old Testament. Within both Leviticus and

Isaiah, Petterson argues, the surrounding literary context strongly supports an interpretation of the guilt

offering and atonement language that relate them to the plight of divine wrath aroused by human sin.

Matt Anslow’s article is a response to Belousek’s lecture on “Jesus’ Death and the Synoptic

Gospels: New Exodus and New Covenant,” with particular focus on the “ransom saying” in Mark 10:45

and the interpretation of his death given by Jesus in the context of the Last Supper. In both instances,

Anslow’s evaluation of Belousek’s overall case is largely positive, though he poses a number of critical

questions on matters of interpretive detail and method, e.g. whether Belousek is convincing in his

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

2

argument for excluding an intertextual reference to Isa 53 in the ransom saying of Mark 10:45, and

whether he pays sufficient attention to the arguments of scholars who find a substitutionary meaning in

the ransom saying without relying on the assumption of an Isaian echo.

David Starling’s article responds to Belousek’s lecture on “Jesus’ Death and the Pauline Epistles:

‘Mercy Seat’ and Place-Taking,” and takes Rom 1–6 as a case study in how Paul describes the relationship

between atonement, justice and peace. Starling finds common ground with Belousek on a number of key

points: God’s justice is not one-dimensionally retributive, his saving righteousness does not terminate at

justification, and the peace announced in the gospel demands visible social embodiment, not merely the

inward tranquillity of the soul. Nevertheless, Starling insists, the frame within which Paul expounds the

saving work of Christ in Rom 3:21–26 offers strong support for a reading that interprets Paul’s depiction

of Christ as a hilastērion against the backdrop of divine, judicial wrath, and suggests no good reason for

taking this as inconsistent with these other, complementary, Pauline emphases.

The final article, by Darrin Snyder Belousek, offers brief rejoinders to each of the four papers,

dealing first with the two that offer a more favourable assessment of his argument and second with the

two that respond more sceptically. The total conversation represented in the articles and rejoinders, like

the face-to-face conversation at the symposium, adds up to a valuable exercise in careful, gracious, and

critical engagement on a set of issues that are of the utmost importance for Baptist and Anabaptist

theology and practice.

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

3

PENAL SUBSTITUTIONARY ATONEMENT IN THE

EARLY CHURCH FATHERS, THE CREEDS, AND

TRINITARIAN THEOLOGY

GRAEME CHATFIELD1

Australian College of Theology

Sydney, Australia

gchatfield@actheology.edu.au

In July 2005 London School of Theology jointly hosted with the Evangelical Alliance (EA) a symposium

on the Theology of the Atonement. The EA had hosted a discussion on the same topic in October 2004,

and the 2005 event was organised to allow for differences of opinion within the EA on this topic to be

more fully canvased. For Steve Chalke and Alan Mann, who perhaps inadvertently sparked the EA 2004

meeting, a significant motivation for their challenge to the dominant penal substitution interpretation of

the atonement (PSA) was how to communicate the message of the cross in a cultural context in which it is

questioned whether it is possible to reconcile a God of love and justice with a God of violence and anger,

as they claim God is popularly depicted in evangelical preaching of penal substitutionary.2 Responses to

Chalke and Mann ranged from the more irenic response of I. Howard Marshall who prayed for “an

understanding of it [PSA] that can command general assent and form the basis for our evangelism,”3 to

that of Joel Green’s plea that interpretations of penal substitution are not used to “distinguish Christian

believer from non-believer or even evangelical from non-evangelical,”4 to Garry Williams who concludes,

“I cannot see how those who disagree [with PSA as he defines it] can remain allied [to the EA] without

placing unity above truths which are undeniably central to the Christian faith.”5

In 2012 Darrin Belousek published his contribution to the atonement debate. His motivation was

to provide a theological bridge between the mission of the church to proclaim salvation through the cross

of Christ and Christian action for justice and peace.6 In his view, the present teaching of PSA does not

1

Graeme Chatfield is Associate Dean of the Australian College of Theology. He previously taught Church History at

Morling College, and is an adjunct faculty member of TCMI, where he teaches Historical Theology at the Austrian

campus and other locations in Eastern Europe. He can be contacted by email: gchatfield@actheology.edu.au

2 S. Chalke, “The Redemption of the Cross,” in The Atonement Debate: Papers form the London Symposium on the Theology of

Atonement (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), 35.

3 I. Howard Marshall, “The Theology of Atonement,” in The Atonement Debate: Papers form the London Symposium on the

Theology of Atonement (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), 63.

4 Joel B. Green, “Must we imagine the atonement in penal substitutionary terms? Questions, caveats and a plea,” in

The Atonement Debate: Papers form the London Symposium on the Theology of Atonement (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008),

167.

5 G. Williams, “Penal Substitution: a response to recent criticism,” in The Atonement Debate: Papers form the London

Symposium on the Theology of Atonement (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 2008), 188.

6 D. W. S. Belousek, Atonement, Justice, and Peace: The Message of the Cross and the Mission of the Church (Grand Rapids:

Eerdmanns, 2012), 5.

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

4

provide such a bridge. He takes issue with the claims of PSA proponents such as Mark Dever7 who states,

“At stake is nothing less than the essence of Christianity”; while Steve Jeffery, Michael Ovey and Andrew

Sach assert “differences over penal substitution ultimately lead us to worship a different God and to

believe a different gospel.”8 In his book on atonement Belousek the philosopher tests these claims.

In May 2014 the Anabaptist Association of Australia and New Zealand (AAANZ) invited Belousek

to Australia and New Zealand for a series of fora to discuss his work on the atonement, justice and peace.

As a Church Historian with a research interest in 16th century Anabaptism I was invited to respond to

Belousek’s presentation of two sections of his work: chapter 6 “The Apostolic Faith Taught by the Early

Church,” and chapter 16 “‘God was in Christ’: Propitiation, Reconciliation, and Trinitarian Theology.”

At the May 2014 conversation Belousek explored the claims of Dever, and Jeffery, Ovey and Sach

by exploring two questions: “Is penal substitution the faith of the Apostles and bishops of the early

church, taught in the ancient creeds of the church catholic?” and “Is penal substitution compatible with

the orthodox doctrine of Trinitarian theology?” He refined this second question by exploring two

additional questions: “Does PSA represent God divided against Himself, and God alienated from

Himself?” He rejected Dever’s claim that PSA was the faith of the Apostles. While he initially conceded

that that PSA may be compatible with the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity as expressed in the creeds of

the church, he later concluded that PSA does in fact represent “a Trinity comprising not only distinct but

separable, even conflicting, persons—quite contrary to the ecumenical creedal affirmations of Nicaea and

Constantinople.”9

ATONEMENT IN THE FAITH OF THE EARLY CHURCH FATHERS AND CREEDS

I agree with Belousek that PSA was not the faith of the Apostles and early church fathers and taught in

the ancient creeds of the church catholic. While Jeffery, Ovey and Sach claim PSA has been affirmed from

the earliest days of the Christian church, and that it was “central to the Christian faith and a foundational

element of God’s plan for the world”10 in Athanasius theology, a person represented as the defender of

the orthodox faith of the early Christian church, they also recognize that PSA was not the only

understanding of the atonement held by the early church fathers. More tellingly, Belousek rightly

challenges Jeffery, Ovey and Sach about reading back into Athanasius’ theology of the atonement an

Augustinian view of sin, death and punishment.11

I am persuaded by the arguments of Frances Young that PSA is only anticipated in the work of the

patristic theologians. She writes: “scholars telling the history of the doctrine of the atonement have always

been able to find anticipations of later doctrines in the patristic material. The classic histories were written

7

Ibid., 96.

Ibid., fn. 14, 100.

9 Ibid., 293.

10 S. Jeffery, M. Ovey and A. Sach, Pierced for our Transgressions: Rediscovering the glory of penal substitution (Nottingham:

IVP, 2007), 203.

11 Belousek, Atonement, Justice, and Peace, fn. 10, 365.

8

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

5

at the beginning of this century, and they were shaped by the current conflict between so-called liberals

and conservatives both catholic and evangelical. The latter asserted that the traditional doctrine of the

atonement, as enunciated by Anselm in the Middle Ages and anticipated in the early material, was in terms

of “penal substitution.”12

Young and Belousek alert us to a key problem when interpreting historical data; identifying the

same word in documents from different periods and investing the older word with the meaning from the

more recent context. Historical explorations of atonement often fall into this trap. Interpretations of

Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo illustrate this problem. Key to the debate is the term “satisfaction.” Belousek

objects to proponents of PSA “conflating” Anselm’s idea of “satisfaction” with Calvin’s “penal

substitution,” and favourably cites Paul Fiddes in support of his view.13 However, Fiddes continues to

locate Anselm in a feudal setting, contrasting the feudal setting with the revival of Roman Law during the

period of the Reformation. Fiddes summaries Anselm’s argument: “Christ is not punished in our place,

but releases us from punishment through satisfaction,” whereas Calvin from his context builds on Anselm’s

premise that where honour is offended, satisfaction needs to be made, but understands the honour of

God to be linked to the divine law to which only punishment can provide satisfaction.14 While I agree

with Fiddes’ premise that historical context greatly influences theological development, more recent study

on the nature of feudalism, and the probable historical context in which Anselm lived and worked, would

question whether it is legitimate to understand Anselm’s understanding of “satisfaction” in terms of a

feudal worldview.15

There have been a series of key words used by theologians when writing about the atonement such

as, but not limited to, salvation, satisfaction, sacrifice, sin, justice, wrath, expiation, propitiation,

forgiveness, peace, reconciliation, obedience, honour, order. Across the centuries, these words have been

invested with meaning drawn from their specific context. Subsequent theologians have used the same

words, demonstrating a kind of continuity with those who have preceded them, but amended the previous

meaning by drawing on the worldview of their own context. For example, Cyprian’s writings (c. 249-258)

use many of the terms and phrases found in the writings of proponents of PSA. Cyprian, in his

controversy about re-admission of the lapsed, attributes the persecution engulfing the church at that time

to be the result of empowering Satan with authority to punish believers because they do not obey “the

12

F. Young, The Making of the Creeds (London: SCM Press, 1991), 89.

Belousek, Atonement, Justice, and Peace, 101-102.

14 Paul S. Fiddes, Past Event and Present Salvation: The Christian Idea of Atonement (London: Darton, Longman and Tood,

1989), 97-98.

15 For a convincing case for a non-feudal setting for Anselm see David L. Whidden III, “The Alleged Feudalism of

Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo and the Benedictine Concepts of Obedience, Honor, and Order,” Nova et Vetera English

Edition, Vol. 9, No. 4, (2011): 1060-1068. However the argument that the Rule of St Benedict provides the

interpretive framework for Cur Deus Homo does not convince me entirely. While Anselm as an Abbot lived with the

Rule as a daily framework, he also lived in a world that saw order beyond the walls of the monastery, a world where

Popes, Emperors, Kings, Princes, Lords, and Knights vied to assert their authority over people within their

territories on the basis of God’s revealed order for the world, a revelation open to varied interpretations.

13

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

6

commandments of the Lord, while we do not keep the salutary ordinances of the law that He has given.”16

He challenges his fellow priests to follow the example of Christ to pray so that satisfaction can be made to

the Father: “But if for us and for our sins He both laboured and watched and prayed, how much more

ought we to be instant in prayers; and, first of all, to pray and to entreat the Lord Himself, and then

through Him, to make satisfaction to God the Father!”17 To the lapsed who seek the peace of the church

he notes that it is by “divine law” that only bishops hold the power to forgive sins, and the lapsed should

be “submissive and quiet and modest, as those who ought to appease God, in remembrance of their

sins.”18 In a telling outburst he contrasts the schismatics with the lapsed. “This is a worse crime than that

which the lapsed seem to have fallen into, who nevertheless, standing as penitents for their crime, beseech

God with full satisfactions. In this case, the Church is sought after and entreated; in that case, the Church

is resisted.”19

However, when Cyprian explains how Christ is able to restore the relationship of people with God,

he echoes Irenaeus’ focus on the incarnation rather than the cross:

Therefore of this mercy and grace the Word and Son of God is sent as the dispenser and

master, who by all the prophets of old was announced as the enlightener and teacher of the

human race. He is the power of God, He is the reason, He is His wisdom and glory; He

enters into a virgin; being the holy Spirit, He is endued with flesh; God is mingled with man.

This is our God, this is Christ, who, as the mediator of the two, puts on man that He may

lead them to the Father. What man is, Christ was willing to be, that man also may be what

Christ is.20

This concept of Christ becoming man so that man may be what Christ is does not appear as a

dominant theme in proponents of PSA. Similarly, Cyprian’s idea of salvation being initiated in baptism,

and guaranteed only when the baptized remain in obedient relationship to the bishops who represent the

Church catholic,21 would not resonate with proponents of PSA who identify continuity not through a line

of bishops but through the gospel as revealed in Christ in the Scriptures. Cyprian puts in place the ideas

that will develop into the medieval penitential system, of an order within society where clergy and laity

were divided, and salvation for the laity depended upon them staying in right relationship with the clergy

through obedience to complete the penance required of them by the Church representatives, the clergy.

However, the understanding of salvation and atonement enunciated by Cyprian was based on a pre“Epistle VII. To the Clergy, Concerning Prayer to God,” in Hippolytus, Cyprian, Caius, Novatian, Appendix (vol. 5 of

Ante-Nicene Fathers, ed. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson; revised Cleveland Coxe; Peabody, MA:

Hendrickson, 1999), 286.

17 Ibid.

18 “Epistle XXVI: Cyprian to the Lapsed”, vol. 5 of Ante-Nicene Fathers, 305.

19 “On the Unity of the Catholic Church”, vol. 5 of Ante-Nicene Fathers, 427.

20 “Treaties VI: On the Vanity of Idols,” vol. 5 of Ante-Nicene Fathers, 468.

21 From baptism “springs the whole origin of faith and the saving access to the hope of life eternal, and the divine

condescension for purifying and quickening the servant of God.” “Epistle LXXII. To Jubaianus, Concerning the

Baptism of Heretics,” vol. 5 of Ante-Nicene Fathers, 382; “Thence, through the changes of time and successions, the

ordering of bishops and the plan of the Church flows onwards; so that the Church is founded upon the bishops, and

every act of the Church is controlled by these same rulers.” “Epistle XXVI. Cyprian to the Lapsed,” vol. 5 of AnteNicene Fathers, 305.

16

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

7

Christendom worldview. Monks had not yet become a major sub-set of the clergy, who by the time of

Anselm vied with the priests in the minds of the laity as to which group could do for them what they

could not do. While the sacraments of the church were necessary, the intercessory prayers of monks and

nuns were also appreciated as effecting forgiveness for post-baptismal sins. By the time of Anselm the

Western Church had an adequate explanation for how the work of Christ achieved atonement for sinners;

the Church catholic as the representative of Christ through its priests mediated the prevenient grace of

God through the sacrament of baptism, and the medicine of grace through the sacrifice of Eucharist,

providing for the removal of punishment through penance, including the intercessory prayer of monks

and nuns. This was received by faith as the truth revealed by God through the church.

Anselm’s Cur Deus Homo does not challenge this understanding of the atonement.22 We might ask

the question “Why address the question of the incarnation and atonement in 1090 when no theologian

had addressed the topic for centuries?” Rather than posit a change in worldview based on the

development of feudalism, there is a more pressing issue that changed Anselm’s world, Islam. Not the

mere existence of that faith, but the increasing interaction of Christians on pilgrimage to the Holy Land

where pilgrims encountered people who argued that the Christian claim that God became man was

contrary to reason.23 Cur Deus Homo might then be seen as an early instalment of the underlying struggle

between revived Aristotelianism and Platonism that played out in parallel with the rise of universities that

began to rival the authority of the church as the locus of “truth,” a struggle that continued to inform the

context of Protestant Reformers when they located “truth” in the revelation of Christ in Scripture,

focused on the cross.

I would suggest that PSA is anticipated in the writings of the early church fathers and the creeds in

the sense that the language used to support PSA existed at that time and is not incompatible with the later

fully developed meanings attributed to it by those who support PSA. This means that other theories of the

atonement can also be anticipated in the writings of the early church and creeds. Each needed to wait till

a worldview existed that would nourish its ideas and assist it to dominate the landscape. The other

theories remained, remnants in isolated locations, until the cultural climate and context changed to allow

them to dominate. Such is the situation today, when the Western Church’s cultural context sees alternative

views to PSA begin to flourish as they are better able to engage with issues raised in the present cultural

context.

Fiddes helpfully notes that while history can only provide “probability” that an event did take place,

there is no need to retreat from locating Jesus in history and making faith only existential encounter.

Rather he would place “historical fact (that is probability) alongside the insights of faith,” not that historical

“Boso. Therefore, since I thus consider myself to hold the faith of our redemption, by the prevenient grace of

God, so that, even were I unable in any way to understand what I believe, still nothing could shake my constancy.”

Cur Deus Homo, ch 2, CLLL, 186.

23 “infidels are accustomed to bring up against us, ridiculing Christian simplicity as absurd … for what necessity, in

sooth, God became man, and by his own death, as we believe and affirm, restored life to the world; when he might

have done this, by means of some other being, angelic or human, or merely by his will.” Cur Deus Homo, ch. 1, 185.

22

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

8

fact can “prove faith; rather, belief that certain events have happened will shape and educate a faith that

comes from encounter with Christ today.”24

The trajectory of this line of thought leads us to ask: Are all views of the atonement equally

legitimate? Who decides which are or are not legitimate? Representatives of the Western Church prior to

the Reformation identified the Church as the locus of authority: for the Conciliarist of the 15 th century the

Church was identified as the Council of Bishops gathered together; the supporters of Papal Primacy

identified the Church with the bishop of Rome. The Reformers rejected the idea that the Church was the

locus of authority to validate doctrine, replacing the Church with Scripture. The Reformers argued

Councils and Popes were fallible; Scripture as the revelation of God was not. Further, they rejected the

notion that the Church established Scripture, insisting that it was Scripture that established the Church. To

counter the accusation that this position would lead to unbridled individualism, the Reformers continued

with the hierarchical model they inherited from their Roman Catholic heritage, the differentiation of clergy

and laity, and investing their creeds established by their learned clergy with authority to determine which

positions were valid and which were not.

There was a third view during the early Reformation which was rejected by both Roman Catholics

and Magisterial Reformers, that the church as the body of Christ, that is believers (having no division

between clergy and laity) when gathered together, considered the Scriptures under the leading of the Holy

Spirit, taking into account the contribution of the scholars learned in the ancient languages and history of

the church, determined the validity of doctrine.25 Fiddes hints at the role the community of believers

played in understanding the cross and the resurrection, a role the present followers of Jesus need to also

undertake when understanding our present day encounters in faith with Jesus.26 Perhaps today’s Western

cultural context with its antipathy towards institutional authority will provide fertile soil in which

congregational hermeneutics can flourish.

GOD DIVIDED AND ALIENATED FROM HIMSELF

Belousek’s conclusion that PSA divides God and alienates God the Father from God the Son is in part

based on his assessment of Christ’s cry from the cross, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”27

He argues that if as John Stott, a preeminent proponent of PSA claims, this is an “actual and dreadful

separation,” then it cannot be avoided that God is divided and alienated at the moment of this cry of

dereliction. Where Stott sees the reality of an “actual and dreadful separation” is “balanced” by the faith

statement that there can be “no separation” in God, Belousek sees “incoherence.”28 Once again Belousek

24

Fiddes, Past Event and Present Salvation, 38.

This is a summary of Balthasar Hubmaier’s congregational hermeneutic that he initiated in Waldshut and

Nicolsburg 1525-1527 but moved away. G. Chatfield, Balthasar Hubmaier and the Clarity of Scripture (Eugene, OR:

Pickwick Publications, 2013), 365.

26 Fiddes, Past Event and Present Salvation, 41.

27 Belousek, Atonement, Justice, and Peace, 301.

28 Ibid, 302.

25

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

9

the philosopher demands logical clarity. He summaries the PSA interpretation of Jesus’ cry of dereliction

as follows:

This separation between the Father and the Son happens … because at the cross Jesus both

bears the sins of all humanity and suffers the penalty for those sins in place of humanity,

both of which are necessary in order for Jesus to satisfy divine retribution as the universal

penal substitute. The Father, whose justice requires this punishment for sin but whose

holiness can have nothing to do with sin, must separate himself from the sin the son bears

and so must separate himself from—and, hence, “turn his back” on or “hide his face”

from—the sin-bearing Son.29

Defenders of PSA have recognized the problem of alienation of Father and Son inherent in PSA,

and have offered solutions other than that of Stott cited above. Jeffery, Ovey and Sach suggest the cry of

dereliction is only metaphoric, but this does not support the reality of the separation between Father and

Son PSA teaches. I. Howard Marshall focuses on the relational nature of sin, and the infliction of

proportionate suffering by God on the sinner, being exclusion from the presence of God. Christ as our

substitute on the cross not only experiences the wrath of God for our sin but also bears in himself the

consequences of our sin, “eternal exclusion” from God’s presence.30 Belousek claims the logical

conclusion of Marshall’s approach is an eternal separation in the Godhead. However, as Tony Campolo

put it, “It’s Friday, but Sunday’s coming,” the resurrection challenges the idea of eternal separation. I find

the insight of Paul Fiddes helpful at this point.

If we understand the “wrath” of God to be his confirming of the natural consequences of

human estrangement … and if we see Christ as participating in the deepest human

predicament, then we can speak (with Karl Barth) of God’s suffering his own contradiction

of sinful humanity; we need not speak of God’s contradicting himself. … The shock of the

silence at the cross is God’s exposure of his very being to non-being, as the Son is identified

with those for whom the Father must, with infinite grief, confirm death as the goal of their

own direction of life. This breach in God cannot be diminished, even by saying with Boff

that Jesus turns his deepest despair into “trust in the Mystery.” The cry of forsakenness

cannot be abridged like this; it is not resolved, at the cross, into a word of trust, but rings out

in all its starkness. But it is not the last word; the resurrection tells that as God takes death

into himself, he is not overcome by it. All hangs in the balance as the being of God and

death strike against each other; yet God sustains his being in the face of death, and makes it

serve him.31

As “God was in Christ” on the cross reconciling the world to himself, God the Father experiences

relationally in himself the reality of the consequences of sin as experience by God the Son. One of those

consequences is separation, a separation based on mutual consent. However, Belousek rejects the idea that

29

Ibid, 301.

Ibid, 303.

31 Fiddes, Past Event and Present Salvation, 194.

30

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

10

mutual consent allows for abandonment. “How, though, can one consent to be abandoned or forsaken by

another? If I consent to your taking leave of me, then I have not been forsaken by you and you have not

abandoned me—we have merely parted; I am left alone, but not derelict.”32 If it could be shown that a

case could be imagined where two people could by mutual consent separate so that one was left

abandoned, totally forsaken to face death alone, then Belousek’s objection to the real abandonment of the

Son by the Father would be brought into question. Imagine a couple, married for many years and deeply

in love, driving in their car which crashes through a barrier into a lake. As the car is sinking, one is

trapped, the other can escape from the car. They both face death, but by mutual consent because of their

love for one another, they separate; the trapped one to die alone and abandoned, the other to experience

in the separation their own suffering from abandonment. Yet, mutual love which motivated the consent,

gives meaning to the act, while still not cancelling out the reality of the separation, suffering and death. If

such a scenario is possible for human beings, surely it is possible for God.

While it is helpful for the philosophers to challenge the thinking of theologians, there are some

areas of our faith where the limitations of human logic become evident. The creeds provided boundaries

around the mystery that is the Trinity, but the Trinity remains a mystery to be accepted by faith. If this

were not the case, then human reason would be sufficient to encompass God. In my view reason may

support faith, but the biblical revelation allows for mystery and paradox within faith. The atonement, be it

PSA interpretation or any of the other approaches must all, in the end, confront the finitude of our

human reason in the face of the mystery that God should willingly choose to become human to effect the

restoration of relationship with Him.

32

Belousek, Atonement, Justice, and Peace, 306.

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

11

ATONEMENT, JUSTICE AND PEACE IN THE

OLD TESTAMENT (ESPECIALLY LEVITICUS

AND ISAIAH 53): A RESPONSE TO DARRIN

SNYDER BELOUSEK’S ATONEMENT, JUSTICE,

AND PEACE

ANTHONY R. PETTERSON1

Morling College

Sydney, Australia

AnthonyP@Morling.edu.au

Darrin Snyder Belousek’s book is written out of the conviction that theology shapes life, especially one’s

theology of Jesus’ atonement. This is admirable and I appreciate the opportunity to engage with his work

on the OT concerning such an important topic. While there is much with which I agree, in this limited

response I want to identify three significant points of disagreement, particularly his claims about God’s

wrath in the OT, the nature of atonement in Leviticus, and the significance of the Servant’s suffering in

Isa 53.

1. GOD’S WRATH AGAINST SIN IS IMPLIED EVEN IN PASSAGES WHERE IT IS NOT

MENTIONED

Belousek seeks to break the link between sin, God’s wrath, and the necessity of punishment for sin. He

says: “The personal wrath of God cannot be reduced to the middle term of a syllogism between sin and

punishment, as penal substitution would have it.”2 Yet the evidence that is mounted to support this thesis,

when examined more closely, actually supports the traditional connection between sin and God’s wrath

and punishment. For instance, Belousek contends that God brought about the flood in Noah’s day, “not

out of holy wrath against human evildoing … but rather out of heart-felt regret and sorrow for his own

having created a humankind whose heart is inclined toward evil (Gen 6:5-7; cf. 8:21).”3 Hence, the flood is

not an instance of God’s wrath, but his “heart-felt regret and sorrow.” While Belousek is correct to

observe that God’s wrath is not mentioned anywhere in the Genesis flood account, Isa 54:9 interprets the

1

Anthony Petterson lectures Old Testament and Biblical Hebrew at Morling College in Sydney. His email address is:

AnthonyP@Morling.edu.au

2 D. S. Belousek, Atonement, Justice, and Peace: The Message of the Cross and the Mission of the Church (Grand Rapids:

Eerdmans, 2012), 213.

3 Ibid., 182.

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

12

flood in exactly these terms: “To me this is like the days of Noah, when I swore that the waters of Noah

would never again cover the earth. So now I have sworn not to be angry with you, never to rebuke you

again” (cf. 2 Pet 2:5-9). Significantly, in Isaiah this turning aside of God’s wrath is a result of the work of

the Servant in the previous chapter, Isa 53, something that I will come to later. Isaiah 54:9 demonstrates

that God’s wrath against sin is implied even in passages where it is not mentioned.4

God’s wrath and punishment are much more closely connected than Belousek allows.5 Even when

wrath is not explicitly mentioned in connection with punishment, there are several important passages that

establish this as the theological framework through which God’s punishment for sin in the OT is to be

viewed. For instance, the covenant curses in Lev 26 and Deut 28–29 provide a framework for interpreting

God’s punishment in Israel’s history, to which the prophets often refer. Here the covenant curses are

explicitly said to be an outworking of God’s anger (Lev 26:28; Deut 29:23-28). While the book of Judges

traces the spiralling of the nation deeper into sin, it only occasionally mentions God’s anger or wrath, yet

the framework established in Judg 2:6–3:6 indicates that the reader of the book is to interpret Yahweh’s

punishment for sin as an outworking of his wrath (vv. 14, 20).6 Solomon’s prayer at the dedication of the

temple also looks towards Israel’s subsequent history and indicates that sin arouses God’s anger and leads

to the punishment of exile (1 Kgs 8:46). Similarly, the writer of Kings explains the exile of the northern

kingdom in exactly these terms (2 Kgs 17:17-18).

So, my first point is: just because wrath is not mentioned, does not mean that wrath is not present.

The wider OT context clearly establishes an interpretative framework that teaches us to infer that God’s

wrath is a “middle term” between sin and its necessary punishment.

2. ATONING SACRIFICES IN LEVITICUS NOT ONLY CLEANSE BUT ALSO RANSOM

Belousek seeks to demonstrate that the atoning sacrifices in Leviticus make no sense in terms of penal

substitution, but in doing so he tells only one side of the story. Belousek rightly talks about the

rites bringing cleansing, but in Leviticus the rites not only bring cleansing, they also serve as a

ransom to appease Yahweh.7

4

Belousek seeks to demonstrate that there is no necessary link between wrath and punishment by citing the instance

of Uzzah reaching out his hand to steady the ark when David was transporting the ark to Jerusalem (2 Sam 6:6-7).

Belousek calls this “inadvertent contact with the holy” and that God’s wrath is “for a cause other than sin.” Yet most

commentators agree that David and Uzzah sin in transporting the ark on a cart in violation of Yahweh’s earlier

instruction (Num 4:15; 7:9; cf. Exod 25:12-15; 1 Chr 15:13). In transporting the ark on a cart, in the context of the

books of Samuel, the Israelites are acting just like the Philistines (1 Sam 6:7-12). Moreover, it may be that David is

guilty of manipulating Yahweh into his service. See for instance, R. P. Gordon, I & II Samuel: A Commentary (The

Library of Biblical Interpretation; Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1986), 232. Hence, this is not simply “inadvertent

contact”—it is the climax of a series of sins for which God’s wrath and punishment are a consequence.

5 A sample of passages that explicitly connect God’s wrath with his punishment of sin in the OT include: Exod 32:910; Lev 26:14-33; Num 12:9-15; Deut 4:25; 6:15; 7:4; 1 Kgs 8:46; 11:9; 2 Kgs 17:17-18; Ezra 9:13-14; Ps 11:5-6; Isa

10:5-6; Jer 4:4; Lam 3:42-43; Ezek 7:3, 8-9; Zech 1:12, 15.

6 God’s anger at sin which is expressed in punishment is explicit in Judg 3:8; 6:39; 10:7.

7 J. Sklar, Sin, Impurity, Sacrifice, Atonement: The Priestly Conceptions (Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press, 2005). This is also

suggested by J. Milgrom, Leviticus 1–16 (AB 3; New York: Doubleday, 1991), 1082, and R. E. Averbeck, “,” in

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

13

It is important to note that the rites only functioned in certain circumstances. Normally the

consequence of intentional sin in the priestly literature is death, either by the hand of Yahweh directly, or

by the hands of the covenant community.8 The sacrifice (also referred to in Isa 53) is only for sin

that may be atoned for. The or “guilt” seems to refer to some sort of general suffering that

prompts the sinner to seek out the sin they have committed, or to confess the sin that they have tried to

hide.9 If the sin was not properly dealt with through the appropriate sacrifice, then the implication is that

the person would also die.10

In determining the meaning of it is important to study the use of the cognate noun, .

It refers to the “payment” or “ransom” that in some sin contexts can appease the injured party and bring

peace to a damaged relationship (e.g., Exod 21:28-32; 30:11-16; Num 35:30-34). Jay Sklar, in a recent study

of atonement in Leviticus determines that a is:

…a legally or ethically legitimate payment which delivers a guilty party from a just

punishment that is the right of the offended party to execute or have executed. The

acceptance of this payment is entirely dependent upon the choice of the offended party, it is

a lesser punishment than was originally expected, and its acceptance serves both to rescue

the life of the guilty as well as to appease the offended party, thus restoring peace to the

relationship.11

Sklar demonstrates from several passages that the verb (“to make atonement”) in sin contexts,

refers to the effecting of a (“ransom”) on behalf of the guilty party (as well as purification).12 For

instance, Lev 10:17: “Why have you not eaten the purification offering in the place of the sanctuary, since

it is a thing most holy, and he has given it to you in order to bear away the sin of the congregation, to

make atonement for them before the LORD.”13 Note how the offended party (the LORD) has agreed to a

(the “purification offering”) by which sin is removed (“to bear away”) so that the sinner no longer

needs to face the consequences of their sin.14

Belousek notes that also occurs in the context of impurity and quite naturally asks: “Why

would YHWH be wrathful toward the very altar he has just ordained for the tabernacle? … [Why] is God

wrathful against a woman for having given birth or a man for having a skin lesion?”15 The answer is that

while it is clear that these are not sins that have aroused God’s anger, in the Levitical system, impurity

endangers life. Both sin and uncleanness have a polluting effect. For instance, Lev 20:2-3: “Any Israelite

New International Dictionary of Old Testament Theology and Exegesis vol. 2 (ed. W. A. VanGemeren; Grand Rapids:

Zondervan, 1997), 689-710 (693-695).

8 Sklar, Sin, Impurity, Sacrifice, Atonement, 41, notes the terms “death,” “cutting off,” and “to bear sin” are all found in

the context of intentional sin and refer to the death of the sinner.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid., 43.

11 Ibid., 78. is also used to refer to an ethically questionable payment which delivers a guilty party from a just

punishment and is translated “bribe” (e.g. 1 Sam 12:1-5; Prov 6:34-35; Amos 5:12).

12 Ibid., 100. Note that the means of kipper is not always sacrifice (cf. the scapegoat in Lev 16:21-22; a golden plate in

Exod 28:38).

13 Following the translation of ibid., 94.

14 Ibid., 95.

15 Belousek, Atonement, Justice, and Peace, 176-177.

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

14

or any foreigner residing in Israel who sacrifices any of his children to Molek is to be put to death. The

members of the community are to stone him. I myself will set my face against him and will cut him off

from his people; for by sacrificing his children to Molek, he has defiled my sanctuary and profaned my

holy name.”16 Those who suffer from a major impurity also defile the sanctuary, even if they do not come

in direct contact with it. This is seen in Lev 15:31: “You must keep the Israelites separate from things that

make them unclean, so they will not die in their uncleanness for defiling my dwelling place, which is

among them.”17

While impurity and sin have different starting points, they both end at the same place: they both

defile (requiring cleansing) and they both endanger (requiring ransom).18 This is why the rites must

not only cleanse and remove pollution, they must also ransom and appease. The life of the offerer is

ransomed by means of the life of the animal, its blood (cf. Lev 17:11), which is payment that the offended

party (Yahweh) has agreed to and provided.19 Hence atonement () sacrifices not only cleanse, they

also ransom. The life of the animal substitutes the penalty of death for those who are defiled by

uncleanness or sin.

3. THE SUFFERING SERVANT DEALS WITH GOD’S WRATH

Belousek claims that in Isa 53: “There is not so much as a single allusion to, much less mention of, God’s

wrath in the entire Song, no suggestion that God is angry and needs to be appeased.”20 While it is true that

the fourth Servant Song does not mention God’s wrath, the claim that God’s wrath is nowhere in view is

mistaken when the Song is read in the context of the book. Isaiah 1 sets up the frame for understanding

the book as a whole and central to Israel’s problem is God’s wrath at their sin (1:24-26; cf. 1:9, 18-20).21

Indeed, in Isa 40–66, a variety of vocabulary is used to refer to Yahweh’s anger/wrath: (42:24-25; 48:9;

63:6; 66:15); (47:6; 54:8-9; 57:16-17; 60:10; 64:5, 9); (42:25; 51:17, 20, 22; 59:18; 63:3, 5, 6;

66:15).

God’s wrath is the presenting issue in Isa 53. For instance: Isa 51:17, 19 “Awake, awake! Rise up,

Jerusalem, you who have drunk from the hand of the LORD the cup of his wrath … These double

calamities have come upon you—who can comfort you?” The question posed from the wider and

immediate context is—how can the cup of God’s wrath be removed so that God’s people can be

restored? The answer is that it is the Servant who effects salvation and turns aside God’s wrath. Isaiah 49–

52 anticipates this salvation and in 54–55, the people are invited to participate. As noted earlier, on the

other side of the Song, Yahweh states: “‘In a surge of anger I hid my face from you for a moment, but

16

The polluting effect of sin is seen also in Lev 16:30 and 18:24-25a.

Num 6:9-11 shows that the inadvertent defiling of something that has been sanctified is considered sinful—if

someone dies in the presence of a Nazirite, the Nazirite is considered to have sinned. In the priestly literature,

defiling the sacred is a serious sin itself.

18 Sklar, Sin, Impurity, Sacrifice, Atonement, 159.

19 Ibid., 173-174.

20 Belousek, Atonement, Justice, and Peace, 226.

21 Cf. M. A. Sweeney, Isaiah 1–39 with an Introduction to Prophetic Literature (FOTL 16; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1996),

70: “The oracles contained in this chapter summarize the main themes and message of the book.”

17

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

15

with everlasting kindness I will have compassion on you,’ says the LORD your Redeemer. ‘To me this is

like the days of Noah, when I swore that the waters of Noah would never again cover the earth. So now I

have sworn not to be angry with you, never to rebuke you again’” (54:8-9). Isaiah 53 is the turning point

where the “arm of the LORD” (v. 1) will bring salvation through the Servant, just as it had in the Exodus

(cf. 51:9).22 The salvation is salvation from Yahweh’s wrath, like the days of Noah.

The language of this Servant Song resonates with the priestly world of sacrifice, which links the

function of the Servant with the substitutionary sacrificial motif.23 Given the context of exile, which is

explicitly connected with God’s wrath elsewhere in the OT (see my first point), and the way that the wider

context of Isaiah understands God’s wrath as the presenting problem, the wider context demands that

Isaiah 53 be understood as the solution to God’s wrath at sin.

While Belousek is correct to note that Isa. 53:5a should be translated “He was wounded ‘because

of’ or ‘by’ our transgressions” rather than “for our transgressions,” this is not the most compelling reason

for reading the Servant Song in terms of penal substitution. There are other more substantial reasons.

Verse 4 indicates that the Servant’s suffering is related to the people’s “pain” and “suffering.”24 Verses 1112 then indicate that the “pain” and “suffering” are the consequence of sin. The statement of v. 4, “surely

he took up () our pain” uses the same Hebrew verb as v. 12, “he bore () the sin of many.”

Similarly, “he bore () our suffering” in v. 4, uses the same verb as v. 11, “he will bear ( ) their

iniquities.” Using the same verbs, the terms for suffering early in the Song are replaced with terms for sin

at the end. The Servant does more than just share in the suffering of the people—there is a transfer of

suffering and sin to the Servant.

The verb “bear, lift up” (), is used in connection with “sin” () in eight other passages in

the OT. Four times it means “incur guilt” (by a person’s own wrong actions) (Lev 19:17; 22:17; 22:9; Num

18:22, 32) and in the four other instances it means “experience punishment” (for a person’s own wrong

actions) (Lev 20:20; 24:15; Num 9:13; Ezek 23:49). In all eight instances, the person incurs guilt or

experiences punishment for their own wrongdoing.25 In contrast, here the Servant incurs

guilt/experiences punishment not for his own sins, but for the “sins of many” (v. 12). There is clearly a

transfer of penalty from “us” to the Servant, a transfer that in the context of the Song brings salvation—

the “punishment that brought us peace” (v. 5). This transfer is traditionally captured in the phrase “penal

substitution” (cf. 1 Pet 2:24).

Furthermore, since in Leviticus the sacrifice both cleanses and ransoms, it seems defensible

to read these ideas from Leviticus into the sacrifice of the Servant (v. 10) as the way that God’s wrath is

J. N. Oswalt, The Book of Isaiah: Chapters 40–66 (NICOT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 385: “Yes, Israel had

suffered temporal results for its sins, but that did not mean that it was automatically restored to fellowship with God.

For that to happen, for Israel to be enabled to be the servants of God, atonement was necessary.”

23 M. J. Boda, A Severe Mercy: Sin and Its Remedy in the Old Testament (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2009), 209. For

instance, “sprinkle” (52:15); “bear” (53:6); “guilt offering” (53:10).

24 The following summarises R. B. Chisholm Jr., “Forgiveness and Salvation in Isaiah 53,” in The Gospel According to

Isaiah 53 (ed. D. L. Bock and M. Glaser; Grand Rapids: Kregel, 2012), 191-210 (199).

25 Ibid., 200.

22

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

16

dealt with. Of course the sacrifice of the Servant here is unique, which is expected given the sacrificial

system was not designed to cover the kind of sin the people had committed.26

Belousek contends that the Servant intercedes for the people by “standing in the breach,” as Moses

did in the aftermath of the sin with the Golden Calf (Exod 32). Yet while Moses’ intercession mitigates

God’s anger and punishment, it does not remove it completely.27 God only relents from his earlier

intention to destroy the nation (v. 14), he still punishes them—the Levites strap swords to their side and

kill three thousand of the people (v. 28). Significantly, after this punishment Moses offers to substitute his

own life as atonement for sin (32:30-32). Yahweh rejects Moses’ offer and declares he will punish the

people for their sin, striking them with a plague (32:34-35). Moses’ intercession mitigates God’s

punishment (he will not destroy the nation), it does not remove it—the people suffer. Indeed, the whole

sacrificial system of Leviticus must be understood in the narrative flow of the Pentateuch as instituted by

God to deal with his wrath at sin.28 Furthermore, perhaps it is this instance in Exodus which provides the

background for the Servant.29 While Moses offered to substitute his own life as atonement for sin and was

rejected, God will provide a Servant whose obedience to death will bring atonement.

Admittedly, there are aspects of Isa 53 which are difficult to interpret. Yet, when the theological

framework of the OT is taken into account (which connects the exiles of Israel and Judah directly with

God’s wrath and punishment for sin), and the context of Isa 53 is acknowledged (which looks to a

solution to the problem of God’s wrath amongst other things), and the sacrificial language from Leviticus

is fully appreciated (where the sacrifice is shown to include cleansing and ransom), then it becomes

clear that the work of the Servant in dying to bear the sin of many is what finally brings atonement, deals

with God’s wrath, and restores fellowship with God. Yet this is not the end-point in Isaiah’s vision.

Yahweh’s salvation through the work of his Servant is a work of justice that not only brings about

restoration for the nation, it also brings about a new community who are agents of God’s justice and

righteousness in the world—people who have experienced Yahweh’s justice and so are to bring justice and

righteousness to the nations as part of the transformation of all creation, for the display of his splendour

(e.g., Isa 51:1-8; 55:13; 58:6-14; 60:21).30

26

Boda, A Severe Mercy, 209.

Belousek, Atonement, Justice, and Peace, 212, uses the Golden Calf incident to argue that God’s wrath sometimes “is

turned away by human actions, including prophetic or priestly intercession (Exod 32:7-14; Num 11:1-3; Num 14;

Deut 9:15-21; Ps 106:32).”

28 Cf. Boda, A Severe Mercy, 49: “[Leviticus] contains the legislation that will make possible the enduring presence of

Yahweh in the camp (Exodus 40) and nurture the covenant relationship established with Yahweh in Exodus 19–24.”

29 Suggested by G. P. Hugenberger, “The Servant of the Lord in the ‘Servant Songs’ of Isaiah,” in The Lord’s Anointed:

Interpretation of Old Testament Messianic Texts (ed. P. E. Satterthwaite, R. S. Hess and G. J. Wenham; Carlisle:

Paternoster, 1995), 105-140 (137). While Moses provides the background for the idea of a human substitute for the

nation, I would contend that for Isaiah the Servant is a Davidic figure. Also G. V. Smith, Isaiah 40–66 (NAC 15B;

Nashville: B&H Publishing, 2009), 448.

30 On the relationship between Yahweh’s justice in the atonement and justice, righteousness, and peace among God’s

people see A. Sloane, “Justice and the Atonement in the Book of Isaiah,” Trinity Journal 34 (2013): 3-16. E. A.

Martens, “Yahweh, Justice, and Religious Pluralism in the Old Testament,” in The Old Testament in the Life of God’s

People: Essays in Honor of Elmer A. Martens (ed. J. Isaak; Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 2009), 126, notes how in the OT,

“Justice has both a retributive and a compassionate edge.”

27

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

17

JESUS’ UNDERSTANDING OF HIS OWN DEATH:

REFLECTIONS ON CHAPTER 9 OF DARRIN SNYDER

BELOUSEK’S ATONEMENT, JUSTICE, AND PEACE

MATTHEW ANSLOW

Educator, TEAR Australia

PhD Candidate, Charles Sturt University

matt.c.anslow@gmail.com

I begin my reflections by expressing my gratitude to Dr. Belousek. I am deeply appreciative of his service

to the church by way of his monumental work on the subject of the atonement. It is crucial that we be

willing to thoroughly and critically engage the Scriptures and the history of Christian theology in order to

refine our understanding(s) of the central event of Christian belief—indeed, the central event of history

itself—the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. Equally important is our ongoing reflection on the

implications of this event for our discipleship; the mission to which we are called must of course be

understood in light of Christ’s person and work. Belousek does both in an impressive fashion.

OVERALL REFLECTIONS

Before moving to discussion of the chapter in question (“Jesus’ Understanding of His Own Death”), I

offer some overall reflections on Atonement, Justice, and Peace. As one who shares in Belousek’s commitment

to Anabaptism, I am well aware of the tension between, say, the teaching of Jesus regarding love of

enemies and biblical images of violence. How we interpret the cross is, in some ways, an indication of our

wider hermeneutical commitments. For those committed to Jesus’ teaching regarding peace, questions

around penal substitution have been pervasive in recent times given the obvious implications for Christian

discipleship of propitiatory sacrifice as a descriptive attribute of God.

Belousek’s book is important in regard to such ongoing debates, not least because of the approach

it represents. While it is nowadays common for Christians to cast doubt over doctrines such as penal

substitution, I cannot help but wonder whether such doubt is often motivated by a feeling of discomfort,

a subjective sense of dis-ease. Such feelings may be somewhat valid, but they hardly constitute a

meaningful refutation of the doctrine in question. Belousek’s work stands against such an approach by

committing to engage with the Scriptures in a robust and (I would say) orthodox fashion. In fact,

anecdotally, some people have commented to me regarding the conservative nature of Belousek’s

exegetical approach. I take this as a strength, since it means people from all stripes can engage with his

work (not always the case with critiques of PSA).

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

18

Related to this is that I am impressed with Belousek’s commitment to an inductive approach on the

question of atonement. This involves his insistence on sifting through the textual evidence rather than

moving from a general theory of sin, sacrifice or justice toward more narrow conclusions. In this sense

Belousek’s approach is quite distinct from, say, the increasingly fashionable espousal of Girardian

sociological and anthropological theories for interpreting the atonement. This is not to say that

Girardianism or similar frameworks are without value—on the contrary, I think there is much value in

Girard’s work—but just that such theories are unconvincing to those who do not share their basic

presuppositions. Belousek’s work, focusing as it does on scriptural evidence as the starting point for a

larger theory, centres debate on the biblical text itself rather than on the theories that only potentially form

the basis of engagement with the text. This provides a methodologically suitable approach for people from

a wide range of theological and philosophical backgrounds.

Not that Belousek is blind to the necessity of presuppositions in biblical interpretation—indeed he

spends some time addressing the retributive paradigm as a commitment that exists prior to the act of

reading. Where, perhaps, Belousek’s book could be strengthened is in the exposition of his own

philosophical commitments as they relate to the act of biblical interpretation, although I acknowledge this

could easily be a tome in itself.

I also make note of the scope of Belousek’s work. While his treatment of penal substitution will no

doubt be a point of interest for enthusiasts and critics alike (hence this issue of PJBR), this is by no means

the sole aim of Atonement, Justice, and Peace, nor is a general treatment of atonement in an abstract sense.

Rather, Belousek’s work takes seriously the ethical implications for any atonement doctrine, noting from

the beginning that the retributive paradigm, particularly as reflected in certain approaches to Christian

doctrine, manifests itself very concretely in human society, including public policy. It is fitting, then, that

he sets out to explore the mission of the Church in terms of justice and peace as an expression of a

cruciform worldview.

JESUS’ UNDERSTANDING OF HIS OWN DEATH

From here we move to discuss the content of the book chapter in focus, “Jesus’ Understanding of His

Own Death.” Though in this chapter he will eventually move to analyse three key passages for his overall

case—two that are often used in support of PSA—Belousek begins with a methodological consideration

regarding the question of the historical Jesus. This allows him to set out his commitment to the historical

authenticity of the Gospels’ accounts of Jesus’ sayings about his own death. Such is in contrast to the

scepticism of some historical Jesus scholars who give primacy to their own historical presuppositions over

the evidence of Scripture. This may turn off some progressive readers, but they are probably not the target

audience since they are more likely to have already rejected PSA. Such readers would, however, benefit

from familiarising themselves with Belousek’s critiques of some of the recent attempts to formulate a

nonviolent atonement.

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

19

Belousek then discusses the Lukan Transfiguration account, concluding that Luke understands

Jesus’ death as fitting the pattern of the rejected prophets, and as a New Exodus. Again, this is somewhat

uncontroversial, though the implications are not minor. I imagine some exploration of the Matthean and

Markan accounts of the Transfiguration may have been helpful since they also picture Jesus as fitting the

pattern of a prophet, but with particular focus on the relationship with Elijah/John the Baptist, though I

am sympathetic to the sole choice of Luke’s account for the sake of brevity.

The “Ransom Saying” (Mark 10:45)

Where the chapter moves into more challenging and controversial territory is in the section dealing with

the so-called “ransom saying” in Mark 10:45, and indeed this is the section most requiring attention. The

ransom saying is one of the most difficult and debated verses in the NT. Belousek is critical of John

Stott’s insistence that this verse is connected with the Suffering Servant of Isa 53, preferring instead to

connect it to the Son of Man reference in Dan 7. Despite the towering influence of Stott, particularly his

The Cross of Christ, I am left wondering why Belousek makes him his primary conversation partner at the

outset of this section. There have been more scholarly treatments of this passage in subsequent decades,1

including by those who concur with Stott’s insistence that Mark 10:45 should be connected to Isa 53.

Belousek does refer at some points to significant studies on the topic—including those of Hooker,

McKnight and Kaminouchi—but these are not primary. Moreover, given Belousek’s eventual dealing with

Isa 53,2 whereby he interprets the Suffering Servant poem as not supporting PSA, it is not clear why

separating Mark 10:45 from Isa 53 is critical to his overall case. In fact, in light of Belousek’s enlightening

discussion of the Suffering Servant in a later chapter of his book, an intertextual discussion of these texts

would have proved interesting, if nothing else. It may be that Belousek is too stringent, and in principle I

do not see why an echo of both Isa 53 and Dan 7 cannot exist concurrently in Mark 10:45.3 It may also

have been a strengthening factor for Belousek’s book to have engaged with more Markan commentators

on this question, since many of them associate Mark 10:45 with Isa 53.4 To be fair, Belousek does

1

See especially the discussion by well-known scholars in William H. Bellinger, Jr. and William R. Farmer, eds., Jesus

and the Suffering Servant: Isaiah 53 and Christian Origins (Harrisburg: Trinity, 1998), esp. Morna Hooker, “Did the Use of

Isaiah 53 to Interpret His Mission Begin with Jesus?” 88–103; Rikki E. Watts, “Jesus’ Death, Isaiah 53, and Mark

10:45: A Crux Revisited,” 125–51; and N. T. Wright, “The Servant and Jesus: The Relevance of the Colloquy for the

Current Quest for Jesus,” 281–97. See also G. R. Beasley-Murray, Jesus and the Kingdom of God (Grand Rapids, Mich.:

W.B. Eerdmans, 1986), 273–83; Adela Yarbro Collins, “Mark’s Interpretation of the Death of Jesus,” JBL 128/3

(2009): 545–54; Craig A. Evans, Mark 8:27–16:20 (WBC 34b; Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2001), 109–25; Peter

Stuhlmacher, “Vicariously Giving His Life for Many, Mark 10:45 (Matt 20:28),” in Reconciliation, Law, and Righteousness

(Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1986), 16–29; Rikki E. Watts, Isaiah’s New Exodus in Mark (Tübingen: J. C. B. Mohr,

1997), 270–87; N. T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996), 579–91. For seminal

examples prior to Stott’s work see C. K. Barrett, “The Background of Mark 10:45,” in New Testament Essays (ed. A. J.

B. Higgins; Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1959), 1–18; Morna Hooker, Jesus and the Servant: The Influence of

the Servant Concept of Deutero-Isaiah in the New Testament (London: SPCK, 1959).

2 Chapter 13 of Atonement, Justice, and Peace.

3 For an example of seeing echoes of both passages see Brant Pitre, “The ‘Ransom for Many,’ The New Exodus, and

the End of the Exile: Redemption as the Restoration of All Israel (Mark 10:35-45),” Letter & Spirit 1 (2005): 41–68.

4 E.g. R.T. France, The Gospel of Mark (NIGTC; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2002), 419–21; Ben Witherington III, The

Gospel of Mark: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2001), 288–89; R. Alan Cole, The Gospel

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

20

acknowledge that even if one sees a textual link between Mark 10:45 and Isa 53, this is not sufficient

grounds for equating ransom with penal substitute—a point with which I agree—and so he does make

space for his argument even if his conclusion about the link between Mark 10:45 and Isa 53 were to be

incorrect.

In any case, Belousek is correct to note that any interpretation of the ransom saying should begin

not with Isa 53, another external passage, or any presupposition about Jesus, but with Mark 10:45 itself.

Belousek notes some basic literary-critical observations, and I think incontrovertible his suggestion that

the ransom saying is an elaboration of the entire pericope found in Mark 10:35–45 dealing with greatness

and servanthood. However, when Belousek draws an intertextual comparison between Mark’s ransom

saying and Luke 19:10 (“the Son of Man came … to serve … to give his life”) he opens himself to the

criticism of conflating two distinct narratives, even if he has already stated a hermeneutic of trust

regarding the historicity of the accounts of Jesus’ statements in the Gospels. I am not necessarily opposed

to such a connection, but the point that he makes—that Jesus’ serving is a reference to his whole life and

not just his death—need not rely on Luke 19 since it can be inferred from Mark 10’s insistence that the

disciples are to serve in the same way Jesus serves. Such service cannot refer solely to Jesus’ atoning death

since the disciples cannot emulate it. Belousek’s conclusion that Jesus’ service involves his whole life, and

not merely his death, helps overcome the problem of reducing Jesus’ life and ministry to a mere prelude to

the crucifixion.

In the next part of Belousek’s argument he argues that “ransom” (lytron) refers neither to sacrifice

nor punishment but to the price of the liberation of a slave.5 In this way, Jesus’ way of servanthood

becomes the ransom, the way of liberation. This conclusion regarding this verse is of course not novel; it

was reached by Ched Myers over 25 years ago in his Binding the Strong Man.6 Others have offered various

versions of this interpretation.7 Nonetheless it is necessary to repeat it; Mark 10:45 is one of those

passages that arises regularly for those that seek to explore alternatives to penal substitionary atonement,

and the sole reason is this word “ransom.” Indeed, John Phillips calls 10:45 the “key verse in Mark’s

gospel,” before associating it directly with the lex talionis.8 Belousek goes to some lengths to define lytron in

a way that is consistent with the Hebrew OT (kōpher)/LXX, thus freeing this passage from the imposition

of an external substitutionary paradigm. Moreover, his demonstration of the logical problems of seeing

ransom as substitution is also helpful in clarifying what precisely is meant by the relevant terms

According to Mark: An Introduction and Commentary (TNTC; Leicester: IVP, 1989), 244–45; John R. Donahue & Daniel

J. Harrington, The Gospel of Mark (Sacra Pagina; Collegeville: Liturgical Press, 2002), 313–15.

5 A contested claim, no doubt. See especially Collins, “Mark’s Interpretation,” 545–49.

6 Ched Myers, Binding the Strong Man (2nd ed.; Maryknoll: Orbis, 2008), 279.

7 See for example Sharyn Dowd & Elizabeth Struthers Malbon, “The Significance of Jesus’ Death in Mark: Narrative

Context and Authorial Audience,” JBL 125/2 (2006): 271–97; Alberto De Mingo Kaminouchi, But It Is Not So Among

You: Echoes of Power in Mark 10:32–45 (London: T&T Clark, 2003), 88–156; also those works referenced in Belousek’s

chapter.

8 John Phillips, Exploring the Gospel of Mark: An Expository Commentary (Grand Rapids: Kregel Academic, 2004), 227–

28.

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

21

“substitution,” “exchange,” “ransom,” and “life.” Too often references are made to substitution—

whether for or against the idea—without a firm understanding of what substitution logically entails.9

One issue with Belousek’s work is in his critique and response to the “penal substitution view.” As

stated above, Belousek summarises the PSA view of Mark 10:45 as being in agreement with Stott’s

association of the verse with Isa 53. But this is an incomplete summary. For example, Collins, though

affirming the connection between Mark 10:45 and Isa 53, bases her affirmation of the synonymous

relationship between lytron in Mark 10:45 and hilasterion not on any Isaian connection, but rather on a

combination of a lexical study of lytron in OT and Greek literature and literary-critical considerations in

Mark.10 It would have been helpful for Belousek to engage with such a perspective, or others like it that

do not rely on Isa 53 to hold to a substitutionary reading of Mark 10:45, since they conflict with the

chapter being discussed without being directly addressed in it.11

Another issue worth mentioning is Belousek’s insistence, following Leon Morris, that the ransom

of Mark 10:45 is not literally paid to anyone, that the ransom is not an “exact description of the whole

process of salvation.”12 I am sympathetic to this perspective, though I do wonder if rejecting the need for

a literal explanation of the mechanism of ransom is hermeneutically problematic in light of Belousek’s

very literal rendering and critique of the notion of “substitution” vis-à-vis “exchange.” If we are able to

take the concept of ransom as a “useful metaphor”13 in which certain details are not exact (to whom the

price paid), why can we not, in principle, do the same with other concepts embedded in the metaphor

(“exchange”)? This concern cascades into another regarding the persuasiveness of Belousek’s argument

for his intended evangelical audience. Specifically, will those who subscribe to an alternative and exact

explanation of the mechanism of ransom within the framework of PSA be convinced by Belousek’s

argument here? Of course, this last point is not a criticism of Belousek’s position, since even if he is

correct, he will not be convincing to all readers.

The Last Supper

Belousek moves finally to discuss the Last Supper accounts. He rectifies the PSA insistence on associating

the “cup of Jesus’ blood” with the Levitical sacrifices by pointing out that, narratively speaking, the Last

Supper is actually associated with the Passover. Here Belousek must be careful not to create a false

dichotomy, as if the Last Supper cannot reference more than one narrative of the past. Belousek does

defend the exclusion of a reference to Levitical sacrifice by pointing out Jesus’ bypassing of the temple

system, but there is still the possibility that Jesus intends his act at the Last Supper to reference and subvert

See Collins, “Mark’s Interpretation,” 547 for an example of blurring the distinction between “substitution” and (in

Belousek’s language) “exchange.”

10 Collins, “Mark’s Interpretation,” 545–49. See also Adela Yarbro Collins, “The Signification of Mark 10:45 among

Gentile Christians,” HTR 90/4 (1997): 371–82.

11 Belousek, Atonement, Justice, and Peace, 149–56.

12 Belousek (quoting Leon Morris), Atonement, Justice, and Peace, 156.

13 Ibid.

9

�Pacific Journal of Baptist Research

22

this system. Jesus’ forgiveness of sins, and thus his assumption of the atoning function of the temple cult,

prior to the Last Supper, however, suggests Belousek is probably correct on this point.

The remainder of Belousek’s discussion of the Last Supper is fairly detailed, and I am not able to

do justice to it in this context. His acumen in deconstructing the logical problems of seeing Jesus the

Passover Lamb as a penal substitute is clear and formidable. The same is the case with his treatment of the

blood of the covenant as seal of relationship rather than instrument of remission of sins. By portraying

Jesus’ death as the moment of a New Exodus and the restoration of covenant, Belousek puts forward an

aspect of the atonement that includes liberation from slavery to sin and death, the renewal of relationship

with God, the forgiveness of sins, return from exile, the healing of disease, and the coming of God’s

kingdom, all without giving up anything of crucial importance within the penal substitutionary model. It

does this without the need for a retributive approach to justice and peace but with a profound

appreciation for the details of the biblical story.

CONCLUSION

I conclude by noting that among Belousek’s most sage pieces of advice is his reminder to us that, “When

interpreting Jesus’ death, we must be careful neither to collapse its manifold of meaning into a singularity,

nor to superimpose the view of Jesus’ followers onto Jesus himself.”14 This does not entail accepting every

proposed meaning for Jesus’ atonement (indeed Belousek clearly does not), but it does mean being

attentive to the varied aspects of the scriptural witness. May the ongoing discussions of Belousek’s work

be open to more than just our favourite texts. Furthermore, may these discussions approach the subject of