Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser.

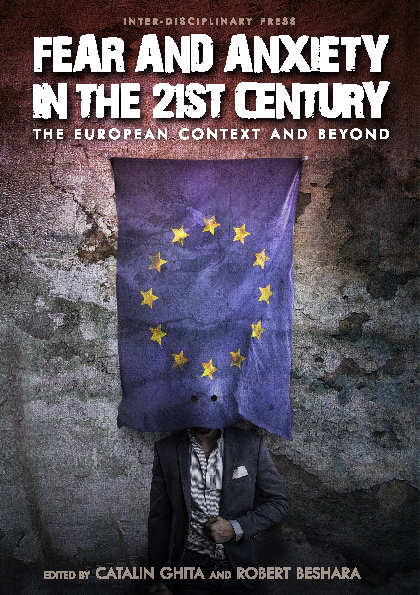

Fear and Anxiety in the 21st Century: The European Context and Beyond

Fear and Anxiety in the 21st Century: The European Context and Beyond

Fear and Anxiety in the 21st Century: The European Context and Beyond

Fear and Anxiety in the 21st Century: The European Context and Beyond

Fear and Anxiety in the 21st Century: The European Context and Beyond

This inter-disciplinary volume is centred upon the complex and ever-changing issues entailed by fears and anxieties in contemporary Europe and, thence, the whole world. Indeed, the fate of Europe mirrors the fate of the world itself: events are no longer localized, but, as soon as they have occurred, they have become part and parcel of our experience as a genuinely cosmopolitan species. Some of these fears and anxtieties are nurtured by real events, whilst others are rooted in imaginary phenomena. The experts who have contributed to this exciting work come from different fields of study (from history to economics and from anthropology to linguistics), yet what they have in common is a genuine commitment to the integrity of inter-disciplinary research, which teaches mutual respect and scientific curiosity.

Related Papers

At first glance, the main concerns this collective volume is dealing with could be formulated by means of several inquiries, as such: are we trapped in a sphere dominated by anxiety? Are we constantly forced to look back or forward in order to get rid of the fear that seems to be an inherent factor of the contemporary world? Are we able to change something? – these are some of the essential questions brought into our attention by the book entitled Fear and Anxiety in the 21st Century, The European Context and Beyond. Additionally, it must be clearly stated that the essays included in this volume, rather than being separate units of writing, are a cohesive work depicting some of the major episodes that affected human beings, especially throughout the last century. Thus, by making use of an inter-disciplinary method, scholars coming from distinct fields of thought, such as economics, politics, anthropology or linguistics have managed to correlate their visions and embody a consistent work which shows that not only xenophobia, Islamophobia or Russophobia can alter the state and the relationship between various nations, thus provoking wars of thought or hostilities, but, very frequently, there is an innate tendency of individuals to generate a certain level of disquietude. All these factors maintain the fear and anxiety known as peculiar attributes of the 21st century.

Today almost half of the global population is online and an estimated 3.2 billion people stay connected. How many of them will fall victim to cybercrimes and cyberbullying? How many will suffer from Internet Addiction and cyber-related disorders? How many will be cheated by other online users? How many will be haunted by their own past mistakes which have suddenly been posted online? On the Internet every information may become a permanent record, following the users who were not aware of the consequences of their ‘click’ when they shared a photo, posted a text, or filled a form, not knowing who was on the other end. A friend of a cyber-friend may turn into a cyberbully, online love affairs may end in cyberstalking, sharing too much information may lead to cybercrimes, Internet frauds and identity thefts. Hackers, Cyberbullies, Online Predators, Catfish, and Trolls – they live offline and thrive online.

There’s More to Fear than Fear Itself: Fears and Anxieties in the 21st Century

EVIL States of Mind: Perceptions of Monstrocity2016 •

There can be little doubt that monsters and other evil entities have found a permanent place in human's conceptual systems. This is hardly surprising given there have been many monstrous types that people have encountered during the various stages of societal and cultural development. One of the possible reasons why monsters survive so persistently in culture and language is that they are within, making them internal and thus eternal. What is perceived as monstrous and the ways in which monstrosity is visualised may vary. The basic components, however, will come from a predictable repertoire of loathsome and grotesquely distorted features. Gilmore states that ‘[t]he organic components constituting the monster are symbolic manifestations of emotions displaced, or projected in visual form’. This could be explained by the fact that a number of individuals are increasingly reported in grisly and disturbing news-stories as having carried out inhuman acts of particular cruelty. Noting the differences between the two, Gilmore asserts that ‘there is always a non-fixed boundary between men and monsters. In the end, there can be no clear division between us and them, between civilisation and bestiality’. Cultural models of fear-inducing objects or events owe as much to instinct as to folk wisdom and classical mythology — Greek mythology, in particular. Various narratives which frame certain emotions, such as fear, carry a strong telic element. This is partly why modern narratives utilise the language of myth or folk stories to formulate particular world-views, ethical values and emotional responses. It is a common occurrence for people today to be prisoners of their fear, particularly because most, horrors are man-made. This multidisciplinary paper aims to demonstrate how modern monsters and demons emerge from fear-induced narratives.

In: There’s More to Fear than Fear Itself. Fears and Anxieties in the 21st Century, edited by Izabela Dixon, Selina E. M. Doran, and Bethan Michael, 111-122. First edition: Oxford: IDPress 2016; second edition: Leiden: Brill 2019, Inter-Disciplinary Press Sociology, Politics and Education Special E-book Collection, 2009-2016. ISBN: 978-1-84888-404-5. doi: https://doi.org/10.1163/9781848884045.

Contemporary democracies, weakened by an increasing distrust in politics and politicians, more frequently have to face up to the threat of radical political movements like extreme right groups and parties. According to Piero Ignazi, the contemporary far-right constructs its identity on the foundations of xenophobia, racism, authoritarianism and an anti-system approach. 1 In recent years, the outcomes of the elections both to the and national parliaments show that the extreme right is moving from the margins of the political scene into its centre. At the same time, a significant growth of followers of far-right groups is visible amongst the youth that, in response to unemployment and a lack of social stability, seek radical and populist solutions. In order to better understand the present-day extreme right and meaning of their communication codes, it is essential to examine the language they employ, since language fulfils the most important role in creating and reproducing reality. Semantics research shows that words convey certain meanings constituting ideological worldviews. Even a neutral word linked with other words in particular contexts can create new meanings, specific for a given discourse, and/or alter their semantics. The main goal of this chapter is the reconstruction of the linguistic/ideological worldview of the Polish and British extreme right. Comparing the language employed by the and the in their online publications, the author will attempt to identify the core values and elements of far-right ideological concepts, their semantics and communicational functions. The main thesis is that the contemporary extreme right is frequently employing words typical of mainstream politics in order to disseminate extreme views. This article originally appeared in book "There’s more to Fear than Fear Itself: Fears and Anxieties in the 21st Century" edited by Izabela Dixon, Selina E. M. Doran and Bethan Michael (2016), first published by the Inter-Disciplinary Press.

RELATED PAPERS

Trauma and Meaning Making

Loss and Dis/Orientation of the Emotional and Geographical Exile in Nancy Huston's Losing North2016 •

2016 •

Crafting Media Personas

Shadowy Reflections: Nazis, Commies and Uncle Sam in the Indiana Jones Series2016 •

Negotiating Childhoods

Remembering and Creating Childhood in the Works of Ingmar Bergman and August StrindbergSins, Vices and Virtues

Freedom, Anxiety, and Sin: Kierkegaard and the Temporal Progression of Experience2013 •

Gdańsk Juornal of Humanities (Jednak Książki. Gdańskie Czasopismo Humanistyczne)

Holocaust Satire on Israeli TV: the Battle against Canonic Memory Agents2016 •

Humour, Language and Protests in Romania

Humour, Language and Protests in Romania2018 •

2017 •

Care, Loss and the End of Life

Surviving the ‘Dark Night’ with the ‘Rising of the Sun’: When the Monarch Dies2016 •

University of California Undergraduate Journal of Slavic and East/Central European Studies

"The Romanian New Wave: Witnessing Everyday Life in the Ceausescu Era and Understanding Post-Communist Dilemmas"2012 •

A Journey through Forgiveness

Felicia Hemans, the Psycho-Dynamics of Hope, and 'Trend Forgiveness

Catalin Ghita

Catalin Ghita Robert Beshara

Robert Beshara