Claytronics-modular robotics to a new extreme

Programmable Matter

Rajat Sharma

Department of Electronics and Communication Engineering

Model Institute of Engineering and Technology

Jammu, India.

rajatkathua@gmail.com

Abstract—The present paper deals with the concept of new

emerging technology called Claytronics. This paper explores the

published articles that report on results from research conducted

by the Intel and Carnegie Mellon University. Claytronics is a

form a programmable matter that takes the concept of modular

robots to a new extreme. The research is the brainchild of Seth

Goldstein, an Associate Professor in the Computer Science

Department at Carnegie Mellon University and Todd Mowry,

Director of Intel Research Pittsburgh. They determined that, by

taking advantage of advances in Nano-scale assembly, they might

create human replicas from ensembles of tiny computing devices

that could sense, move, and change colour and shape, enabling

more realistic videoconferencing. The vision behind this research

is to provide users with tangible forms of electronic information

that express the appearance and actions of original sources.

Keywords- Research design: Dynamic Physical rendering;

ensemble.

I.

INTRODUCTION

Imagine a lump of clay in hands. Children will love to

squeeze it in between fingers, potters will fire it into bowls and

artists will shape it into sculptures. This simple clay consists of

hundreds and thousands of microscopic particles. Can a

material be so intelligent that it changes its shape as we require.

The idea is simple: make basic computers housed in tiny

spheres that can connect to each other and rearrange

themselves. Each particle, called a Claytronic atom or Catom,

is less than a millimetre in diameter. With billions any object

can be created.

Catoms, or Claytronics Atoms, are also referred to as

'programmable matter'. These are basically miniature pieces of

matter so intricate that they can shape-shift into actual shapes

of whatever desired based on a quick, programmable system.

Catoms are described as being similar in nature to a Nanomachine, but with greater power and complexity. While

microscopic individually, they bond and work together on a

larger scale. Catoms can change their density, energy levels,

state of being, and other characteristics. This vision of

nanotechnology is light years away from today's world of

carbon nanotubes.

The research called "Claytronics" at Carnegie-Mellon

University, and "Dynamic Physical Rendering" at Intel is

already underway. According to the Claytronics project's Seth

Goldstein and Todd Mowry, programmable matter is:

An ensemble of material that contains sufficient

•

Local computation

•

Actuation

•

Storage

•

Energy

•

Sensing & communication

which can be programmed to form interesting dynamic

shapes and configurations.

This novel idea has evolved into an ambitious collaboration

involving almost 30 researchers. Jason Campbell, a senior

researcher at Intel Research Pittsburgh, is the Principal

Investigator for the DPR project. Goldstein is leading the

project for Carnegie Mellon, and Mowry provides additional

leadership. The project is being funded by Intel, Carnegie

Mellon University, the National Science Foundation, and the

Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA).

Creation of claytronics technology is the bold objective of

collaborative research between Carnegie Mellon and Intel,

which combines nano-robotics and large-scale computing to

create synthetic reality, a revolutionary, 3-dimensional display

of information.

Claytronic emulation of the function, behaviour and

appearance of individuals, organisms and objects will fully

mimic reality - and fulfil a well-known criterion for artificial

intelligence formulated by the visionary mathematician and

computer science pioneer Alan Turing.

In 1950, in a ground-breaking article, Turing asked "Can

Machines Think?" and offered a criterion to "refute anyone

who doubts that a computer can really think." His proposal

was that "if an observer cannot distinguish the responses of a

programmed machine from those of a human being, the

machine is said to have passed the Turing Test."

Although the Turing Test remains a robust source of

discussion among those who devote their lives to artificial

intelligence, philosophy and cognitive science, claytronics

conceives of a technology that will surpass the Turing Test for

the appearance of thought in the behaviours of a machine.

�The Carnegie Mellon Intel Claytronics Research Project

combines two principal paths to create technology that will

represent information in dynamic, life-like 3-D form-

Engineering design and testing of modular robotic

catom prototypes that will be suitable for

manufacturing in mass quantities

Creation of programming languages and software

algorithms to control ensembles of millions of catoms

II.

HARDWARE

At the current stage of design, claytronics hardware

operates from macro-scale designs with devices that are much

larger than the tiny modular robots that set the goals of this

engineering research. Such devices are designed to test

concepts for sub-millimeter scale modules and to elucidate

crucial effects of the physical and electrical forces that affect

nano-scale robots.

A. Electrostatic latches

Electrostatic Latches model a new system of binding and

releasing the connection between modular robots, a connection

that creates motion and transfers power and data while

employing a small factor of a powerful force. A simple and

robust inter-module latch is possibly the most important

component of a modular robotic system. The electrostatic latch

in Figure 1 was developed as part of the Carnegie Mellon-Intel

Claytronics Research Project. It incorporates many innovative

features into a simple, robust device for attaching adjacent

modules to each other in a lattice-style robotic system. These

features include a parallel plate capacitor constructed from

flexible electrodes of aluminium foil and dielectric film to

create an adhesion force from electrostatic pressure. Its

physical alignment of electrodes also enables the latch to

engage a mechanical shear force that strengthens its holding

force.

The electrodes that form the latch fit into "genderless" faces

constructed as star-shaped plastic frames carried by each

module. In the design of the circuits, each electrode functions

as one-half of a complete capacitor. A latch forms when the

faces of two adjacent modules come together and create an

electrostatic field between the flexible electrodes.

Figure 1. Electrostatic Latches (Source-www.cs.cmu.edu/~claytronics)

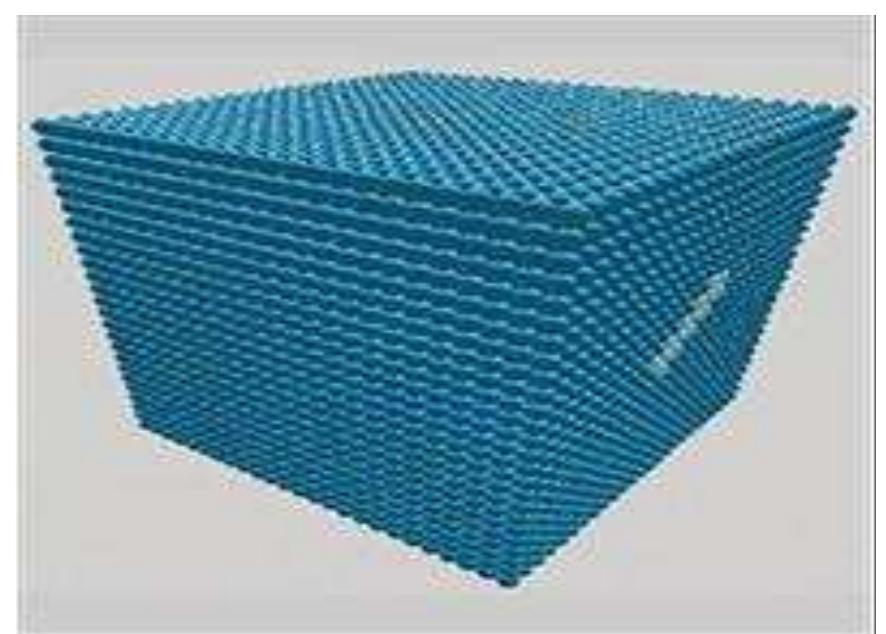

B. Cubes

A lattice-style modular robot, the 22-cubic-centimeter

Cube, which has been developed in the Carnegie Mellon-Intel

Claytronics Research Program, provides a base of actuation for

the electrostatic latch that has also been engineered as part of

this program. The Cube shown in Figure 2 also models the

primary building block in a hypothetical system for robotic

self-assembly that could be used for modular construction.

Cubes employ electrostatic latches to demonstrate the

functionality of a device that could be used in a system of

lattice-style self-assembly at both the macro and nano-scale.

The design of a cube, which resembles a box with

starbursts flowering from six sides, emphasizes several

performance criteria: accurate and fast engagement, facile

release and firm, strong adhesion while Cube latches clasps one

module to another. Its geometry enables reliable coupling of

modules, a strong binding electrostatic force and close spacing

of modules within an ensemble to create structural stability.

With extension and retraction of stem-drive arms that carry

the latches, the module achieves motion, exchanges power and

communicates with other Cubes in a matrix that contains many

of these devices.

Combining these forces of motion,

attachment and data coupling, Cubes demonstrate a potential to

create intricate forms from meta-modules or ensembles that

consist of much greater numbers of Cubes; numbers

determined by the scale of Cubes employed in an ensemble of

self-construction.

C. Planar Catoms

The self-actuating, cylinder-shaped planar catom tests

concepts of motion without moving parts, power distribution,

data transfer and communication that will be eventually

incorporated into ensembles of nano-scale robots. It provides a

test bed for the architecture of micro-electro-mechanical

systems for self-actuation in modular robotic devices.

Employing magnetic force to generate motion, its operations

as a research instrument build a bridge to a scale of

engineering that will make it possible to manufacture selfactuating nano-system devices.

Figure 2. Cubes

(Source-www.cs.cmu.edu/~claytronics)

�Figure 4. Matrix of 20,000 catoms (Source-www.cs.cmu.edu/~claytronics)

Figure 3. Planar Catoms

(Source-www.cs.cmu.edu/~claytronics)

The planar catom is approximately 45 times larger in

diameter than the millimeter scale catom for which its work is

a bigger-than-life prototype. It operates on a two-dimensional

plane in small groups of two to seven modules in order to

allow researchers to understand how micro-electro-mechanical

devices can move and communicate at a scale that humans

cannot yet readily perceive or imagine.

Among the six faces, the triangular flaps provide each

catom with the means to form an electrostatic latch with

another cube from 24 positions - providing the cubes with a

capacity to move at right angles in any direction. In addition

to motion, the latches also equip the GHC with the means to

communicate across the ensemble of catoms. In Figure 4, one

Giant Helium Catom pivots across the surface of another,

revealing the positions and attachments of triangular

electrostatic flaps.

III.

SOFTWARE

A. Distributed Computing in Claytronics

In a domain of research defined by many of the greatest

challenges facing computer scientists and robot-cists today,

perhaps none is greater than the creation of algorithms and

programming language to organize the actions of millions of

sub-millimeter scale catoms in a claytronics ensemble.

As a consequence, the research scientists and engineers of

the Carnegie Mellon-Intel Claytronics Research Program have

formulated a very broad-based and in-depth research program

to develop a complete structure of software resources for the

creation and operation of the densely distributed network of

robotic nodes in a claytronic matrix.

A notable characteristic of a claytronic matrix is its huge

concentration of computational power within a small space.

For example, an ensemble of catoms with a physical volume of

one cubic meter could contain 1 billion catoms. Computing in

parallel, these tiny robots would provide unprecedented

computing capacity within a space not much larger than a

standard packing container. This arrangement of computing

capacity creates a challenging new programming environment

for authors of software.

A representation of a matrix of approximately 20,000

catoms can be seen in the figure 5 shown. Because of its vast

number of individual computing nodes, the matrix invites

comparison with the worldwide reservoir of computing

resources connected through the Internet, a medium that not

only distributes data around the globe but also enables nodes

on the network to share work from remote locations. The

physical concentration of millions of computing nodes in the

small space of a claytronic ensemble thus suggests for it the

metaphor of an Internet that sits on a desk.

B. An Internet in a box

Comparison with the Internet, however, does not represent

much of the novel complexity of a claytronic ensemble. For

example, a matrix of catoms will not have wires and unique

addresses which in cyberspace provide fixed paths on which

data travels between computers. Without wires to tether them,

the atomized nodes of a claytronic matrix will operate in a

state of constant flux. The consequences of computing in a

network without wires and addresses for individual nodes are

significant and largely unfamiliar to the current operations of

network technology.

Languages to program a matrix require a more abbreviated

syntax and style of command than the lengthy instructions that

widely used network languages such as C++ and Java employ

when translating data for computers linked to the Internet.

Such widely used programming languages work in a network

environment where paths between computing nodes can be

clearly flagged for the transmission of instructions while the

computers remain under the control of individual operators

and function with a high degree of independence behind their

links to the network.

In contrast to that tightly linked programming environment

of multi-functional machines, where C++, Java and similar

languages evolved, a claytronic matrix presents a software

developer with a highly organized, single-purpose, densely

concentrated and physically dynamic network of unwired

nodes that create connections by rotating contacts with the

closest neighbors. Matrix software must also actuate the

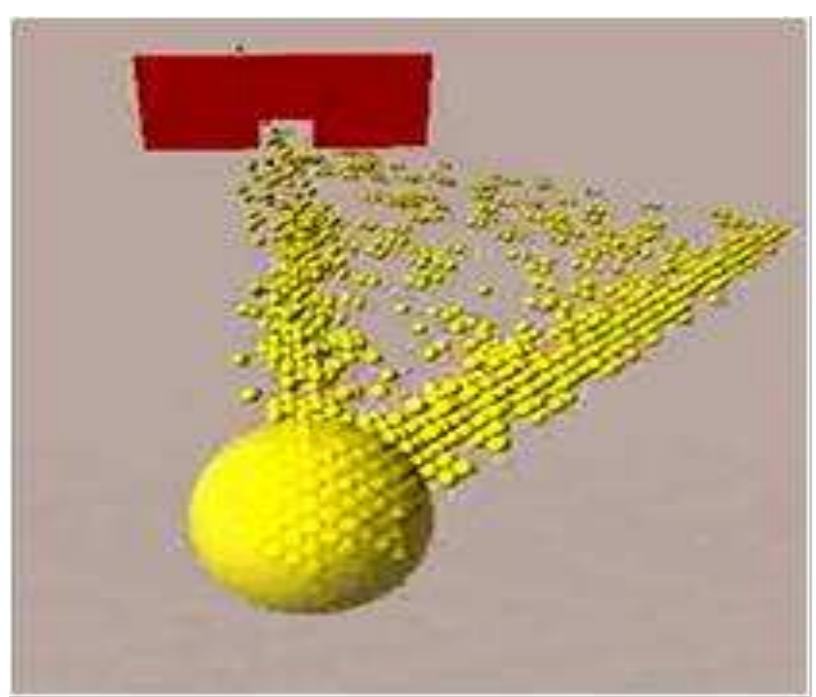

�Figure 5. Simulation of Meld (Source-www.cs.cmu.edu/~claytronics)

Figure 6. Snapshot in DPRSim (Source-www.cs.cmu.edu/~claytronics)

constant change in the physical locations of the anonymous

nodes while they are transferring the data through the network.

test and visualize the behaviour of catoms. The simulator

creates a world in which catoms take on the characteristics

that researchers wish to observe.

DPRSim operates as a Linux-based system on desktop

computers. It is available as open source software. DPRSim

has become the primary tool of the Carnegie Mellon-Intel

Claytronics Research Project for observing real-time

performance when designing, testing and debugging modular

robots in claytronic ensembles.

The simulated world of DPRSim manifests characteristics

that are crucial to understanding the real-time performance of

claytronic ensembles. Most important, the activities of catoms

in the simulator are governed by laws of the physical universe.

Thus simulated catoms reflect the natural effects of gravity,

electrical and magnetic forces and other phenomena that will

determine the behaviour of these devices in reality. DPRSim

also provides a visual display that allows researchers to

observe the behaviour of groups of catoms. In this context,

DPRSim allows researchers to model conditions under which

they wish to test actions of catoms. Figure 8 presents snapshot

from simulations of programs generated through DPRSim.

C. Programming Languages

Researchers in the Claytronics project have also created

Meld and LDP. These new languages for declarative

programming provide compact linguistic structures for

cooperative management of the motion of millions of modules

in a matrix. Figure 7 shows a simulation of Meld in which

modules in the matrix have been instructed with a very few

lines of highly condensed code to swarm toward a target.

Meld is a programming language designed for robustly

programming massive ensembles. Meld was designed to give

the programmer an ensemble-centric viewpoint, where they

write a program for an ensemble rather than the modules that

make it up. A program is then compiled into individual

programs for the nodes that make up the ensemble. In this way

the programmer need not worry about the details of

programming a distributed system and can focus on the logic of

their program.

Because Meld is a declarative programming language

(specifically, a logic programming language), the programs

written in Meld are concise. Both the localization algorithm

and the metamodule planning algorithms are implemented in

Meld in only a few pages of code.

While Meld approaches the management of the matrix from

the perspective of logic programming, LDP employs

distributive pattern matching. As a further development of

program languages for the matrix, LDP, which stands for

Locally Distributed Predicates, provides a means of matching

distributed patterns. This tool enables the programmer to

address a larger set of variables with Boolean logic that

matches paired conditions and enables the program to search

for larger patterns of activity and behaviour among groups of

modules in the matrix.

D. Dynamic Simulation

As a first step in developing software to program a

claytronic ensemble, the team created DPR-Simulator, a tool

IV.

CAPABILITIES OF CATOMS

Computation: Researchers believe that catoms could

take advantage of existing microprocessor technology.

Given that some modern microprocessor cores are now

under a square millimeter, they believe that a

reasonable amount of computational capacity should fit

on the several square millimeters of surface area

potentially available in a 2mm-diameter catom.

Motion: Although they will move, catoms will have no

moving parts. This will enable them to form

connections much more rapidly than traditional microrobots, and it will make them easier to manufacture in

high volume. Catoms will bind to one another and

move via electromagnetic or electrostatic forces,

depending on the catom size.

Imagine a catom that is close to spherical in

shape, and whose perimeter is covered by small

electromagnets. A catom will move itself around by

�

Power: Catoms must be able to draw power without

having to rely on a bulky battery or a wired

connection. Under a novel resistor-network design the

researchers have developed, only a few catoms must be

connected in order for the entire ensemble to draw

power. When connected catoms are energized, this

triggers active routing algorithms which distribute

power throughout the ensemble.

Communications: Communications is perhaps the

biggest challenge that researchers face in designing

catoms. An ensemble could contain millions or billions

of catoms, and because of the way in which they pack,

there could be as many as six axes of interconnection.

At a high level, there are two steps:

energizing a particular magnet and cooperating with a

neighbouring catom to do the same, drawing the pair

together. If both catoms are free, they will spin equally

about their axes, but if one catom is held rigid by links

to its neighbours, the other will swing around the first,

rolling across the fixed catom's surface and into a new

position. Electrostatic actuation will be required once

catom sizes shrink to less than a millimeter or two. The

process will be essentially the same, but rather than

electromagnets, the perimeter of the catom will be

covered with conductive plates. By selectively

applying electric charges to the plates, each catom will

be able to move relative to its neighbours.

Another unique feature of catom networks is that

catoms are homogeneous. Thus, unlike cell phones or

other communications devices, the identity of an

individual catom is sometimes (but not always)

unimportant. An application is more likely to care

about routing a message to the catoms comprising a

specific physical part of an ensemble (for instance, the

catoms comprising a "hand") rather than sending the

same message to specific catoms based on their serial

numbers. Furthermore, catoms may be in motion

periodically, as the shape of the ensemble changes.

Creating the replica: Researchers at Carnegie Mellon

University also are exploring 3D image capture, in the

Virtualized Reality project. They have developed

technology that points a set of cameras at an event and

enables the viewer to virtually fly around and watch

the event from a variety of positions. The DPR

researchers believe a similar approach could be used to

capture 3D scenes for use in creating physical, moving

3D replicas.

Figure 7. Replica Formation

(Source: www.intel.com)

•Capturing a moving, three-dimensional image and

•Rendering it as a physical object.

Replicas will be created from Catoms. Catoms

can be framed into different shapes, and it can change

color, through light-emitting diodes on its surface.

Embedded photo cells will enable it to sense light, so

that a human replica can "see." Catoms might even

simulate the texture of the person or object being

replicated. A replica will have computing capabilities,

but these will be accessed through touch, voice, or

another natural interface rather than a keyboard or

mouse. Catoms will be as close to spherical as possible

to support multiple packing densities.

V.

APPLICATIONS

The potential applications of dynamic physical rendering

are limited only by the imagination. Following are a few of the

possibilities:

Medicine: A replica of your physician could appear in

your living room and perform an exam. The virtual

doctor would precisely mimic the shape, appearance

and movements of your "real" doctor, who is

performing the actual work from a remote office.

Disaster relief: Human replicas could serve as standins for medical personnel, firefighters, or disaster relief

workers. Objects made of programmable matter could

be used to perform hazardous work and could morph

into different shapes to serve multiple purposes. A fire

hose could become a shovel, a ladder could be

transformed into a stretcher.

Entertainment: A football game, ice skating

competition or other sporting event could be replicated

in miniature on your coffee table. A movie could be

recreated in your living room, and you could insert

yourself into the role of one of the actors.

3D physical modeling: Physical replicas could replace

3D computer models, which can only be viewed in two

(Source: www.cs.cmu.edu/~claytronics)

Figure 8. 3D model of Car formed by Catoms

�dimensions and must be accessed through a keyboard

and mouse. Using claytronics, you could reshape or

resize a model car or home with your hands, as if you

were working with modeling clay. As you manipulated

the model directly, aided by embedded software that's

similar to the drawing tools found in office software

programs, the appropriate computations would be

carried out automatically. You would not have to work

at a computer at all; you would simply work with the

model. Using claytronics, multiple people at different

locations could work on the same model. As a person

at one location manipulated the model, it would be

modified at every location.

VI.

ENVISIONING THE FUTURE

Backed by the microchip manufacturer Intel, first

generation catoms, measuring 4.4 centimeters in diameter and

3.6 centimeters in height have already been created. The goal is

to eventually produce catoms that are one or two millimeters in

diameter-small enough to produce convincing replicas. It's not

just a problem of building tiny robots, but figuring out how to

power them, to get them to stick together and to coordinate and

control millions or billions of them. These catoms, which are

ringed by several electromagnets, are able to move around each

other to form a variety of shapes containing rudimentary

processors and drawing electricity from a board that they rest

upon. So far only four catoms have been operated together. The

plan though is to have thousands of them moving around each

other to form whatever shape is desired and to change colour,

also as required.

Five years from now, the DPR researchers expect to have

working ensembles of catoms that are close to spherical in

shape. These catoms still will be large enough that no one will

confuse a replica with the real thing (for that, catoms will

probably have to shrink to less than a millimeter in diameter).

But the catoms will be sufficiently robust that researchers can

experiment with a variety of shapes, test hypotheses about

ensemble behaviour, and begin to envision where the

technology might lead within a decade or two.

While the potential applications of dynamic physical

rendering are exciting, the work being done at Intel Research

Pittsburgh and Carnegie Mellon University has broader

implications. At its core, the research involves learning to

design, power, program and control a densely packed set of

microprocessors. These are similar to the key challenges facing

the computer industry today. As a result, the DPR research is

likely to produce new insights and technologies that could

influence the future of computing and communications.

If, in 1960, someone had suggested that one day you could

buy a million transistors for a penny, the prediction would have

seemed outlandish. But today Intel sells transistors for less than

a micro cent, thanks to the continuing technology advances

predicted by Moore's Law. It's not unreasonable to predict that

one day far in the future; it may be possible to buy a million

catoms for a penny.

But dynamic physical rendering could become viable long

before Moore's Law drives down the cost of a catom to a

micro-cent. Even if catoms could be produced for a dollar each,

some visualization applications might be economically viable.

Whatever the cost, building catoms that are one millimeter

in diameter-small enough to create convincing replicas-will be

a difficult engineering challenge. But given current industry

knowledge and the state of the art of silicon technology, it is

not outside the realm of possibility. The challenge lies less in

developing new technology than in bringing together a number

of research areas in which the industry has made tremendous

technical progress in the last decade.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

In the preparation of this research paper, I am grateful to

the Principal of MIET and specially to Lecturer Parshotam

Sharma, H.O.D. of E.C.E. Dept., who have left no stone

unturned for the successful completion of this paper.

I have received help and encouragement for which I am

deeply grateful to my friends- Shwetanshu Gupta, Vivek Singh,

Rajat Basotra, Sahil Dogra, Rahul Lakhanpuria, Rameshwar

Sharma, Varinder Singh, Sourab Sharma and Ankush Sharma.

My special dept. of gratitude to my grandfather Sh. Jai Dev

Sharma, my father Sh. Joginder Raj Sharma and my mother

Smt. Suman Sharma for their help and motivation.

REFERENCES

[1]

www.cs.cmu.edu/~claytronics(Carnegie Mellon University official

website: dated- 09/09/11)

[2] S.Goldstein, J. Campbell, and T. Mowry, “Programmable matter,” IEEE

Computer, vol. 38, 6, pp. 99–101, May 2005.

[3] G. Chirikjian, A. Pamecha, and I. Ebert-Uphoff, “Evaluating efficiency

of self-reconfiguration in a class of modular robots,” Journal of robotic

systems, vol. 13, no. 5, pp. 317 – 338, 1996.

[4] Michael P. Ashley-Rollman, Michael De Rosa, Siddhartha S. Srinivasa,

Padmanabhan Pillai, Seth Copen Goldstein, Jason Campbell,

“Declarative programming for modular robots” unpublished.

[5] M. Ashley-Rollman, S. C. Goldstein, P. Lee, T. Mowry, and P. Pillai,

“Meld: A declarative approach to programming ensembles,” in

Proceedings of IEEE/RSJ Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems

(IROS), 2007.

[6] Brian Kirby, Jason Campbell, Burak Aksak, Padmanabhan Pillai, James

Hoburg, Todd Mowry, Seth Copen Goldstein “Catoms: moving robots

without moving parts” unpublished.

[7] A. Pamecha, I. Ebert-Uphoff, and G. Chirikjian, “Useful metrics for

modular robot motion planning,” in IEEE Transactions on Robotics and

Automation, vol. 13, 1997.

[8] James Cameron and William Wisher Jr. Terminator 2: Judgment Day.

Columbia TriStar, 1991.

[9] D. Soloveichik and E. Winfree, “Complexity of self-assembled shapes,”

in DNA Computers 10, 2005.

[10] Dprsim available[Online]:

http://www.pittsburgh.intelresearch.net/dprweb/

�

Rajat Sharma

Rajat Sharma