Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser.

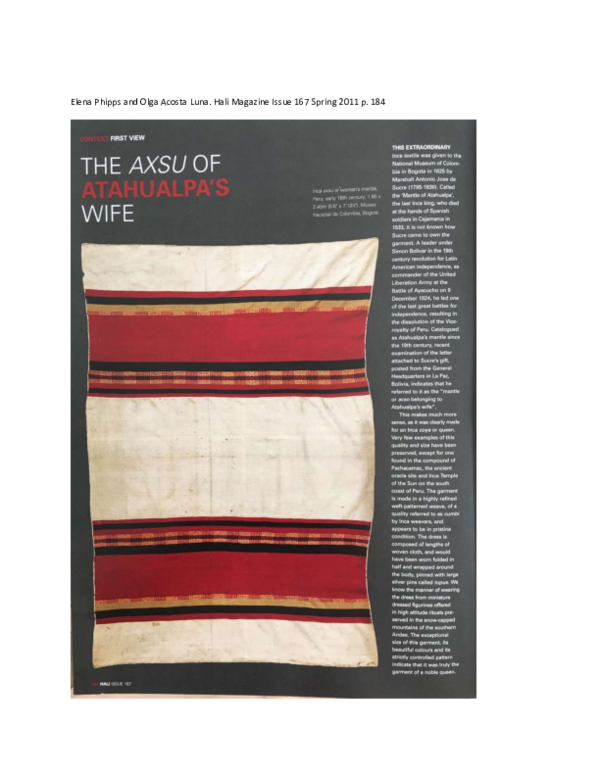

The AXSU of Atahualpa's Wife

The AXSU of Atahualpa's Wife

Extraordinary garment in the Museo Nacional in Colombia. The attached is the one page published version, joined with the original text version

Related Papers

2008 •

This publication is based on papers presented in a conference on the Incas, held in 2014 at the Linden-Museum. 30 other authors also have papers published in this volume, and the linked PDF includes all of them.

Wearing Culture: Dress and Regalia in Early Mesoamerica and Central America

Aspects of Dress and Ornamentation in Coastal Oaxaca's Formative Period2014 •

“Mesoamerican Archaeological Textiles, Materials, Techniques, and Contexts”

Filloy Nadal, L. “Mesoamerican Archaeological Textiles, Materials, Techniques, and Contexts”, L. Bjerregaard y A.P.(eds.), PreColumbian Textile Conference VII/Jornadas de Textiles Precolombinos VII, Lincon Nebraska, Zea Books/University of Nebraska Press, 2017: 7-392017 •

Wearing Culture: Dress and Regalia in Early Mesoamerica and Central America

Making the Body Up and Over: Body Modification and Ornamentation in the Formative Huastecan Figurine Tradition of Loma Real, Tamaulipas2014 •

This paper examines an unidentified Peruvian textile from the Ditto Collection at the College of William and Mary and attributes the textile to the Chimú culture of the Ancient Andes. This attribution is based on a careful analysis of the Ditto textile and a comparison to Chimú textiles, which includes an examination of weave, color and fringe style. Additionally, this paper attempts to reconstruct the function of the Ditto textile by examining the social hierarchy of Chimú society and proposes that the Ditto Textile was in a preparatory stage. Since the Ditto Textile has uncommon characteristics such as plain decor and braided fringe, this attribution to Chimú suggests that not textiles were elaborate and intricate.

RELATED PAPERS

The Arts and Sciences of Judo Vol. 1 No. 2

The Origins and Development of Kano Jigoro's Judo Philosophies2021 •

2020 •

INTED2018 Proceedings

VARIABLES INSEPARABLE IN HIGHER EDUCATION: TEACHING AND RESEARCH2018 •

16 COURT OF APPEAL TAX CASES-2022.

16 COURT OF APPEAL TAX CASES-20222023 •

Case Reports and Images In Oncology

Brain Cystic Metastases in a Patient with Advanced Atypical Lung Carcinoid2020 •

Journal of Educators Online

Experiential Work in a Virtual World: Impactful and Socially Relevant Experiential LearningIndonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

Game innovation: a case study using the Kizzugemu visual novel game with Tyranobuilder software in elementary schoolbioRxiv (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory)

Best Paper awards lack transparency, inclusivity, and support for Open Science2023 •

RELATED TOPICS

- Find new research papers in:

- Physics

- Chemistry

- Biology

- Health Sciences

- Ecology

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

Elena Phipps

Elena Phipps