2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

Roman Art at the Art Institute of Chicago

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

Published by: Art Institute of Chicago

Cat. 7

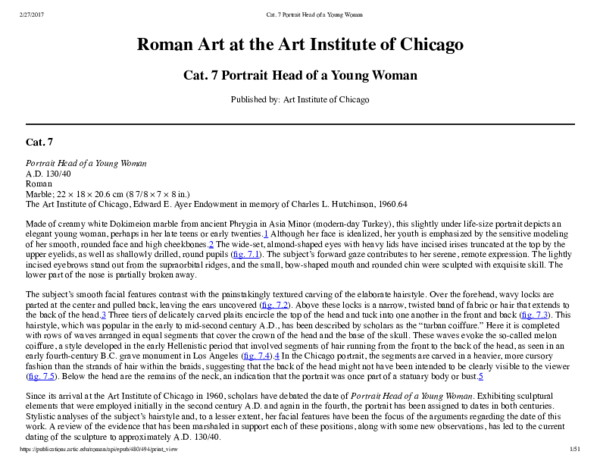

Portrait Head of a Young Woman

A.D. 130/40

Roman

Marble; 22 × 18 × 20.6 cm (8 7/8 × 7 × 8 in.)

The Art Institute of Chicago, Edward E. Ayer Endowment in memory of Charles L. Hutchinson, 1960.64

Made of creamy white Dokimeion marble from ancient Phrygia in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey), this slightly under life-size portrait depicts an

elegant young woman, perhaps in her late teens or early twenties.1 Although her face is idealized, her youth is emphasized by the sensitive modeling

of her smooth, rounded face and high cheekbones.2 The wide-set, almond-shaped eyes with heavy lids have incised irises truncated at the top by the

upper eyelids, as well as shallowly drilled, round pupils (fig. 7.1). The subject’s forward gaze contributes to her serene, remote expression. The lightly

incised eyebrows stand out from the supraorbital ridges, and the small, bow-shaped mouth and rounded chin were sculpted with exquisite skill. The

lower part of the nose is partially broken away.

The subject’s smooth facial features contrast with the painstakingly textured carving of the elaborate hairstyle. Over the forehead, wavy locks are

parted at the center and pulled back, leaving the ears uncovered (fig. 7.2). Above these locks is a narrow, twisted band of fabric or hair that extends to

the back of the head.3 Three tiers of delicately carved plaits encircle the top of the head and tuck into one another in the front and back (fig. 7.3). This

hairstyle, which was popular in the early to mid-second century A.D., has been described by scholars as the “turban coiffure.” Here it is completed

with rows of waves arranged in equal segments that cover the crown of the head and the base of the skull. These waves evoke the so-called melon

coiffure, a style developed in the early Hellenistic period that involved segments of hair running from the front to the back of the head, as seen in an

early fourth-century B.C. grave monument in Los Angeles (fig. 7.4).4 In the Chicago portrait, the segments are carved in a heavier, more cursory

fashion than the strands of hair within the braids, suggesting that the back of the head might not have been intended to be clearly visible to the viewer

(fig. 7.5). Below the head are the remains of the neck, an indication that the portrait was once part of a statuary body or bust.5

Since its arrival at the Art Institute of Chicago in 1960, scholars have debated the date of Portrait Head of a Young Woman. Exhibiting sculptural

elements that were employed initially in the second century A.D. and again in the fourth, the portrait has been assigned to dates in both centuries.

Stylistic analyses of the subject’s hairstyle and, to a lesser extent, her facial features have been the focus of the arguments regarding the date of this

work. A review of the evidence that has been marshaled in support each of these positions, along with some new observations, has led to the current

dating of the sculpture to approximately A.D. 130/40.

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

1/51

�2/27/2017

A Second-Century Date

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

Since the 1960s, roughly half of the scholars who have studied this portrait head have argued for a date in the second-century A.D.6 These claims

have been based primarily on the hairstyle, which, as previously noted, has been identified as an example of the second-century turban coiffure.

Characterized by a series of narrow braids that encircle the upper part of the head, this style is thought to have developed in part out of the elaborate

female hairstyles of the Flavian (A.D. 69–96) and Trajanic (A.D. 98–117) periods, which frequently included a coil of braids at the back of the head.

Whereas this braided feature often took the form of a small bun in the Flavian period, it expanded into a much larger “nest” in the Trajanic period, as

seen in a portrait that might depict the deified Matidia (A.D. 68–119) (fig. 7.6), the mother of the empress Sabina.7 The turban coiffure was worn by

private women in the Trajanic period and was especially popular in the Hadrianic period (A.D. 117–38), but it might have been worn into the early

part of the Antonine period (A.D. 138–93).8 Although imperial women are known to have worn variations on the style, there are no extant portraits

that clearly represent an empress wearing it.9

The hairstyle depicted in Portrait Head of a Young Woman bears a clear resemblance to the turban coiffures represented in a number of secondcentury female portraits.10 Significant attention was paid to the accurate representation of women’s hairstyles in Roman portraiture, no doubt in part

due to the association of artfully styled hair with cultus.11 Numerous variations on this basic coiffure have been identified, perhaps resulting from

sitters’ individual preferences.12

A close comparison to the hairstyle of the Chicago portrait is found in an early Hadrianic bust of a woman in the Musei Capitolini in Rome (fig.

7.7).13 The subject wears an arrangement of neatly parted waves over the forehead, surmounted by a thin, twisted band of hair or fabric marked by

short, diagonal lines, above which sits a turban comprising several rows of braids. Additionally, the hair on the top and back of the head displays

melon-coiffure-like waves similar to those of the Chicago portrait (fig. 7.8). In both sculptures the crown of the head is clearly visible above the

turban, although in the Chicago work a larger portion of it is seen due to the slightly lower placement of the braids at the back of the head.14 Despite

the similarities of the two hairstyles, the carving of the Chicago portrait’s coiffure is of notably higher quality, as evidenced by the graceful rendering

of the individual strands of hair in the braids and locks over the forehead. In contrast, the details of the Capitoline portrait’s coiffure are substantially

harder and more linear throughout.

The Chicago portrait’s facial features, especially the eyes and eyebrows, are also thought to lend some support to a second-century date. In Roman

portraits, the articulation of the eyes through the drilling of the pupils and the incising of the irises appeared as a stylistic feature in the Hadrianic

period, around A.D. 130, after which it became a common component of the sculptural repertoire, thus offering a terminus post quem for this work.15

It has been suggested that the treatment of the eyes in the Chicago portrait, with their nearly circular irises that terminate at the lower edge of the upper

eyelid, along with the drilled pupils, is characteristic of the second century.16 Moreover, the heavy upper eyelids that extend past the outside corners

of the lower lids are associated particularly with Antonine portraiture.17 Finally, the eyebrows, which are distinguished by prominent supraorbital

ridges, reflect a slightly softened version of the more sharply faceted treatment of the eyebrows that appears in numerous Trajanic and Hadrianic

examples, a feature that is thought to have died out during the Antonine period.18

Comparable elements are found in a portrait bust of a woman named Bilia from the ancient city of Apollonia in the Roman province of Macedonia (in

modern-day Albania) (fig. 7.9).19 Much like the subject of the Chicago portrait, this young woman, who also wears an elaborate turban coiffure, is

shown with heavy-lidded, deep-set, almond-shaped eyes; large pupils that appear to be nearly circular in form; and prominent eyebrows, complete

with delicately incised hairs. Although the subject gazes to her right rather than to the front, both likenesses are characterized by a calm, somewhat

distant gaze.

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

2/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

Although the findspot of the Chicago portrait is unknown, certain aspects of the eyes, in particular the round pupils, might be evidence for an origin in

the Greek East.20 This, when considered in light of the marble’s origin in Asia Minor, makes it tempting to speculate that the work might have been

created in the eastern part of the Roman Empire.21 On the other hand, is also possible that the marble was exported and carved elsewhere; indeed,

Dokimeion marble was known to be exported to Rome for use in statuary.22

Regardless of where the portrait was created, the rendering of the eyes and other facial features appears to support a second-century date, specifically

after A.D. 130, when the articulation of the pupils and irises became a common feature, and likely by the early part of the Antonine period, given the

association of the heavy upper lids with the portraits of this era. Taking into account the additional evidence of the turban hairstyle, which was most

popular during the Hadrianic period but is not widely attested in Antonine portraiture, it seems probable that this portrait was created between A.D.

130 and 140.23

A Fourth-Century Date

Portrait Head of a Young Woman has also been dated to the fourth century A.D., albeit to different imperial reigns within that epoch.24 Scholars who

have taken this position have suggested that, like a number of other female portraits assigned to the same period, the Chicago work is a product of a

late antique revival, in which Emperor Constantine (r. A.D. 306–37) and his successors looked to the styles of earlier, favored dynasties for

inspiration.25 However, many of the stylistically closest examples that have been assigned to the fourth (and in some cases fifth) century are marked

by debates analogous to that about the dating of the Chicago portrait.26 Consequently, such portraits in fact offer no secure grounds in support of a

late antique date. While comparisons might be made to more firmly dated portraits from the fourth century, this endeavor is complicated by two

factors: a considerably smaller number of portraits was produced in late antiquity,27 and extant examples have been infrequently found in securely

datable contexts.28 Nevertheless, based on the limited parallels that do remain, there seem to be notable differences between the turban coiffures

favored in the second century and the version of the hairstyle that was popular two centuries later.

In support of an early Constantinian date for the Chicago portrait, Cornelius C. Vermeule argued that the hairstyle of this sculpture resembles that

worn by Constantia (after A.D. 293–c. 330), the half sister of Emperor Constantine, in her posthumous numismatic portrait of A.D. 330.29 Although

the details are difficult to discern due to its small scale, this commemorative coin type clearly depicts Constantia wearing a thick braid that encircles

her head but does not fully cover it (see fig. 7.10).30 In this regard, it is similar to the turban coiffure of the Chicago portrait, although the latter

comprises three narrow braids rather than one thick one. The comparison to this coin type was the sole support for Vermeule’s identification of the

subject of the Chicago portrait as Constantia in 1960. His interpretation was accepted soon after by Michael Milkovich, George M. A. Hanfmann, and

James D. Breckenridge;31 subsequently the subject was identified more generally as a woman of the Constantinian court.32

Constantia’s coiffure in her numismatic portrait more closely resembles a hairstyle seen in some securely dated fourth-century portraits in the round

that is formed by one or two thick plaits encircling the head, often extending down to the nape of the neck.33 Described as the “Zopfkranzfrisur”

(braided crown hairstyle), this coiffure is seen in a seated statue with a fourth-century portrait that is thought to depict Helena (c. A.D. 250–330), the

mother of Emperor Constantine, in the Musei Capitolini in Rome (fig. 7.11).34 Here the turban is composed of two wide braids, the individual strands

of which are cursorily worked, in contrast to the finely carved individual hairs of the braids in the Chicago portrait.

An even closer comparison to the numismatic portrait of Constantia, which illustrates the clear distinction between late antique examples of the turban

coiffure and those of the second century, is found in an early fourth-century portrait of a woman from Fulda, Germany, in the Museum Schloss

Fasanerie (fig. 7.12).35 In this sculpture, three thick braids encircle the head, wrapping from the top of the head to the base of the skull in a nearly

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

3/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

vertical orientation rather than horizontally around the crown. Tongue-shaped locks formed by flattened ringlets cover the forehead, fully conceal the

ears, and extend relatively low on the back of the neck, creating a heavy, almost helmetlike style.36

Based on these comparisons, it is evident that such late antique hairstyles, although incorporating one or more braids encircling the head, are

nevertheless distinct from the second-century turban coiffure as represented in numerous portraits dated securely to that period. The delicate and

elegant hairstyle of the Chicago portrait clearly has more in common with the second-century than the fourth-century examples. While it is unclear

whether the late antique coiffures intentionally evoked this earlier style, the fact that the basic form of a turban of braids was repeatedly used in

numerous portraits in both centuries seems to suggest that it might have held some general significance, as will be addressed below.

Scholars arguing for a fourth-century date have also called attention to certain aspects of the portrait’s facial features, namely the size of the eyes and

the subject’s fixed, forward gaze. In late antique portraiture, the eyes are often enlarged, at times unnaturally so.37 When combined with an intense

gaze, such eyes are thought to convey a sense of greater expressivity.38

The eyes of the Chicago portrait have frequently been described as “large.”39 On closer inspection, however, it is apparent that they are proportional

to the face as a whole; rather, it is the pupils that appear somewhat generously sized. It is perhaps due to the size of the pupils that the subject has been

described as having a “visionary gaze” or a “heavenward glance” of the type often associated with late antique portraits.40 Still, the eyes are not

characterized by the same enlarged proportions seen in some fourth-century examples, such as a portrait thought to depict Fausta (A.D. 289–326), the

wife of Constantine, in the Musée du Louvre (fig. 7.13).41 In this sculpture, the subject’s heavy eyebrows, which nearly meet at the bridge of the nose,

frame oversize, wide-set eyes. Although the eyes similarly include nearly circular irises and large, shallowly drilled pupils, here the large size of the

eyes as a whole clearly distinguishes them from those of Portrait Head of a Young Woman. The “late antique gaze” that some have read into the latter

may therefore owe more to a subjective interpretation of the emotional communication of the work than to the sculptor’s treatment of the facial

features.

Bente Kiilerich argued that the face of the Chicago portrait might have been reworked in late antiquity, given what she saw as the fourth-century

rendering of the eyes, along with the soft treatment of the surface and the precision of the carving.42 If the face was recarved, one might expect the

hairstyle (provided that it was preserved) to be disproportionately large.43 However, examination of the portrait suggests that the proportions of the

face are appropriate to the head as a whole. Furthermore, recarved eyes often appear very deeply set and unnaturally large, which is not the case

here.44 It therefore seems most probable that the entire portrait, including the eyes, the rest of the facial features, and the hairstyle, were carved in the

second century.

The Turban Coiffure as a Symbol of Virtue

As noted above, the turban coiffure’s characteristic arrangement of plaits encircling the head appears to have developed in part out of the smaller bun

or the more sizable nest of braids at the back of the head that was featured in earlier Flavian and Trajanic hairstyles, which also included diadem-like

toupets or crests of hair over the forehead (see fig. 7.6). It has been argued that, rather than being simply an elaboration upon the braided features of

these earlier styles, the turban coiffure might have been intentionally created to communicate a distinct message.

Numerous scholars have observed that the turban coiffure resembles the hairstyle depicted in portraits of Roman priestesses, particularly the

headdresses of the Vestal Virgins, the high-ranking priestesses of Vesta, the Roman goddess of the hearth.45 Recently, Molly M. Lindner has explored

this connection, arguing that private women in Italy of nonelite status developed the turban coiffure to emulate the infula that the Vestals wrapped

around their heads (see fig. 7.14).46 Viewed as a sign of sanctitas (holiness, inviolability, and sacredness), the infula was also worn by other Roman

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

4/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

priests and priestesses, suppliants seeking pardon or protection, and sacrificial victims.47 According to Lindner, following the increased emphasis on

morality (especially that of women) under the emperors Domitian (r. A.D. 81–96) and Trajan, nonelite women sought to imitate the Vestals in order to

demonstrate their own adherence to moral standards, devotion to the gods, and embodiment of sanctitas (by the second century, sanctitas had become

synonymous with the virtue of castitas—chastity, viewed broadly in the context of purity).48 To a lesser extent, the turban coiffure might also have

evoked the distinctive hairstyle the Vestals wore beneath the infula, known as the seni crines (generally translated as “six tressed”), which involved

rows of braids wrapped around the head.49 This style was worn by both Vestals and Roman brides as a symbol of their castitas, here specifically

referring to their virginity.50 For Roman matrons, the allusion to the seni crines might instead have suggested the associations of castitas with marital

fidelity.51

Lindner further proposed that the turban coiffure was soon adopted by Roman women of elite (but not imperial) status, some of whom were

priestesses of other cults.52 Priestesses gained considerable prominence in their local communities, and in some cases they were honored with

portraits in life and in death, which might have incorporated the turban coiffure in order to suggest the infula of the Vestals.53 The association of this

hairstyle with portraits of women of priestly (but non-Vestal) status is evident in an over-life-size, second-century portrait of an elderly priestess in the

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, which shows her wearing a turban of five braids that decrease in width as they proceed from her forehead upward;

below, the locks over the forehead are parted in the center and brushed to the sides of the head (fig. 7.15).54 The subject’s engagement in a religious

act is implied by the palla drawn over her head as a veil; she is identified as a priestess because she is depicted in the act of burning incense, a rare

occurrence in Roman portraiture.55 This portrait, which was the only sculpture found in a vaulted tomb in Pozzuoli in Campania, Italy, was

undoubtedly a lavish and costly commemoration that alluded to the subject’s elevated status and presumably also her significant public role.56

Based on the use of the turban coiffure in the Chicago portrait, Evelyn B. Harrison hypothesized that it might represent a priestess.57 This hypothesis

cannot be verified, due to the absence of the portrait’s statuary body or bust and any accompanying inscription, as well as a lack of information

regarding the context in which it was found. Regardless of the subject’s social standing or potential priestly role, it seems reasonable to suppose that

her hairstyle of neatly wrapped braids helped communicate a message about her character. Although the motivations behind the development and

popularity of the turban coiffure are still not entirely clear, its associations with the headdresses and hairstyles of esteemed women of high virtue, most

notably the Vestal Virgins, suggest that it may have been intended to convey specific ideas about the subject, perhaps emphasizing her morality,

modesty, and chastity.

Conclusion

Portrait Head of a Young Woman is characterized by a hairstyle and facial features that have long been thought to support a date in either the second

or the fourth century A.D. Based on the evidence examined here, the work most likely dates to the second century A.D., specifically to A.D. 130/40.

The turban hairstyle can be confidently dated to the second century on the basis of its resemblance to the coiffures of numerous portraits made in the

Hadrianic period, many of which have been dated according to other stylistic features, including the articulation (or lack thereof) of the eyes. The

drilled pupils and incised irises of the Chicago portrait indicate a date after around A.D. 130, while other aspects of the eyes, such as the heavy

eyelids, are characteristic of Antonine portraiture, suggesting that it was made during the transition from the Hadrianic to the Antonine style. Given

the general similarities between the turban coiffure and the headdresses and hairstyles worn by women known for their virtue, particularly the Vestal

Virgins, it is possible that the subject’s elegantly braided tresses projected a comparable image of her virtuous nature.

Katharine A. Raff

Technical Report

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

5/51

�2/27/2017

Technical Summary

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

This object is a fragment of a portrait bust or statue depicting a young woman. The fragment was carved from a single block of exceedingly finegrained, white marble, marked by exceptional translucency and brilliance, that has been identified as Dokimeion (fig. 7.16). A variety of toolmarks are

visible across the surface. No evidence of polychromy or gilding has been detected. Burial conditions have given the stone a slight ocher tone overall,

and further evidence of antiquity can be found in the abundance of root marks distributed over the surface, particularly in the braids on the back of the

head. As a whole the head is in stable condition; however, it has suffered a number of noticeable losses. Documentation in the curatorial and

conservation files indicates that the object has undergone various surface treatments, generally of an aesthetic nature, in particular to mitigate a onceheavier incrustation of rootlets.

Structure

Mineral/Chemical Composition

The marble is a warm, bright white with a slightly ocher hue that is due to the presence of surface deposits in carved areas. In highly polished areas,

the translucency of the marble is readily apparent. Vertical striations and veins are visible throughout.

Primary mineral: calcite (calcium carbonate, CaCO3)58

Accessory minerals: graphite, C (traces)

Petrographic Description

A sample roughly 2.1 cm high by 1.6 cm wide was removed from an area of existing loss at the base of the neck on the proper right side. The sample

was then used to perform minero-petrographic analysis. Part of the sample was finely ground, and the resulting powder was analyzed using X-ray

diffraction to determine whether dolomite is present. The remaining portion of the sample was mounted onto a glass slide and ground to a thickness of

30 µm for study under a polarizing microscope.59

Grain size: fine (average MGS less than 2 mm)

Maximum grain size (MGS): 0.24 mm

Fabric: homeoblastic mosaic

Calcite boundaries: embayed

Microscopic examination of the prepared thin-section sample revealed some intercrystalline decohesion60 and confirmed the presence of traces of

micritic protolith.61

Thin-section photomicrograph: fig. 7.17

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

6/51

�2/27/2017

Provenance

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

Marble type: Dokimeion (marmor docimenum)62

Quarry site: Dokimeion, near modern-day İscehisar, Afyonkarahisar Province, Turkey63

The determination of the marble as Dokimeion was made on the basis of the results of both minero-petrographic analysis and isotopic analysis.64

Isotopic ratio diagram: fig. 7.18

Fabrication

Method

The head is a fragment of a portrait bust or statue. The existing fragment was carved from a single block of stone using the various hand tools and

implements that would have been customary for the period, such as chisels, drills, rasps, and scrapers.65

The break edge along the neck has a somewhat flat but nonetheless irregular profile, and the simplest explanation for its topography is that the head

was broken away without intent from a larger mass of stone. If the portrait was originally a bust, it was in all probability carved from a single block of

stone, and the neck would have been a point of particular vulnerability, prone to damage or fracture. If the head was carved separately to be included

in a larger sculpture, it would likely have included a projection made up of the neck and perhaps the collarbone, and it would have been finished with

a keyed terminus or tenon meant for insertion into a cavity or socket.66 This extension of stone would also have been highly susceptible to impact and

damage. It is also possible that the head was removed purposefully. A deep gouge extends across the surface of the break edge from the front of the

neck toward the back on the proper right side, near an area of damage toward the front of the neck. It is possible that this gouge is the result of a

percussive blow intended to separate the head from the stone below. While it is impossible to say for certain exactly what happened to the head, it is

clear, based on the presence of rootlets on the break edge of the neck, that it was broken prior to burial.

Evidence of Construction/Fabrication

Drills of varying sizes were used to create the nostrils, vestiges of which remain visible in the damaged end of the nose; the pupils of the eyes; and the

front edge of the proper left ear, as evidenced by the circular depressions at the ends of the carved line (fig. 7.19).67 At the inside corners of the eyes,

a drill approximately 1.75 mm in diameter was used to make tear ducts, increasing the naturalism of the portrait and drawing attention to the eyes.

The sculptor used a flat chisel to carve the irises. The proper left iris is somewhat irregular in shape, which may betray a slip of the sculptor’s hand

(fig. 7.20). A very fine flat chisel was employed to delineate the many strands of hair and the braids that are wound around the head. To achieve this

fine detail, the sculptor used the edge of the tool, held at an angle to the stone. The sculptor appears to have taken much less care in the execution of

the waves of hair below the turban at the nape of the neck. This more perfunctory handling of the carving is particularly noticeable directly behind the

ears (see fig. 7.21). This suggests that, although the object was intended to be viewed in the round, this area was not a particular focal point.68

Traces of a rasp are visible on the back of the neck (fig. 7.22), a roughness that contrasts with the high level of finish on the face. This provides further

evidence that this area of the sculpture was not expected to be noticed. Encrusting rootlets overlying the rasp marks indicate their presence prior to

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

7/51

�2/27/2017

burial.

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

The philtrum was carved with a roundel (fig. 7.23).

The marble on the face is highly polished, an effect that would have been realized using a slurry of an abrasive powder such as pumice.69

Artist’s/Fabricator’s Marks

No artist’s or fabricator’s marks were observed.

Additional or Applied Materials

Microscopic examination of the stone’s surfaces revealed no traces of polychromy or gilding.70

Condition Summary

The sculpture has sustained several conspicuous losses. Most notably, the end of the nose is missing, and laminar cleavage, vertically oriented in line

with the veins, is visible in association with the fracture. The back halves of both ears are also missing. There is a large, ovoid spall, with a smaller

lacuna adjacent to it, on the bottom proper right edge of the neck. A lesser but still significant area of damage can be seen on the front edge of the

neck. Residues from the burial environment in the form of red-brown material are present on the surface of this loss. There is a sizable loss to the

topmost braid on the back of the head.

Elsewhere minor chips, spalls, and lacunae are in evidence, particularly throughout the hair. There is a gouge with associated bruising and friable

material on the middle braid on the proper left side of the head. A small chip is present on the outside edge of the bottom proper left eyelid. A spall is

visible nearby on the proper left cheekbone.

Root incrustation—desirable evidence of antiquity—can be seen overall, particularly in the braids on the back of the head and in the hair at the nape of

the neck (fig. 7.24).

Extremely fine scratches and abrasions are present across the surface of the face. These may be the result of efforts to remove burial incrustations.

When the object is examined under ultraviolet radiation, the extent of this scratching is all the more apparent (fig. 7.25).71

A white, chalky material, likely the remains of a plaster support, is present on the surface of the break edge of the neck. A shiny substance, perhaps

from a previous intervention, is visible on the face of the large spall at the base of the neck on the proper right side.

Conservation History

A 1964 condition report in the Conservation Department files, documenting the application of a spray coating of a synthetic resin consolidant,

references a previous cleaning, although no date or details of the prior intervention are supplied.72 Additional documentation in the curatorial object

file reveals that the object was cleaned again in 1976 using an aqueous solution with added detergent. In 1981 further refinements to these cleaning

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

8/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

efforts were performed, this time with some amount of mechanical cleaning of the encrusting rootlets.73 Undated collection photographs in the

curatorial object file demonstrate that the head was previously much more heavily encrusted with rootlets and that the base of the neck once bore a

plaster support, but it is difficult to construct a time line for the removal of these features based on the existing documentation.

Rachel C. Sabino, with contributions by Lorenzo Lazzarini

Exhibition History

Worcester (Mass.) Art Museum, Roman Portraits: A Loan Exhibition of Roman Sculpture and Coins from the First Century B.C. through the Fourth

Century A.D., Apr. 6–May 14, 1961, cat. 34 (ill.).

Boston, Museum of Fine Arts, Roman and Barbarians, Dec. 17, 1976–Feb. 27, 1977, cat. 118 (ill.).

New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century, Nov. 19, 1977–Feb. 12,

1978, cat. 268 (ill.).

Art Institute of Chicago, Featuring Faces, May 23, 1986–Mar. 25, 1987, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, Sculpture from the Classical Collection, Sept. 1, 1987–Aug. 31, 1988, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, Classical Art from the Permanent Collection, Feb. 1989–Feb. 17, 1990, no cat.

Art Institute of Chicago, Private Taste in Ancient Rome: Selections from Chicago Collections, Mar. 3, 1990–Sept. 16, 1990, cat. 7.

New Haven, Conn., Yale University Art Gallery, I, Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome, June 6–Dec. 1, 1996; San Antonio Museum of Art, Jan. 3–Mar.

2, 1997; Raleigh, North Carolina Museum of Art, Apr. 6–June 15, 1997, cat. 128 (ill.).

Thessaloniki, Museum of Byzantine Culture, Everyday Life in Byzantium, Oct. 21, 2001–Jan. 10, 2002, cat. 464.

Selected References

John Maxon, “Report of the Director of Fine Arts,” in Art Institute of Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago Annual Report 1959–1960 (Art Institute of

Chicago, 1960), p. 14.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Two Masterpieces of Athenian Sculpture,” Art Institute of Chicago Quarterly 54, 5 (Dec. 1960), pp. 6–10; p. 8 (ill.).

Michael Milkovich, Roman Portraits: A Loan Exhibition of Roman Sculpture and Coins from the First Century B.C. through the Fourth Century A.D.,

April 6–May 14, 1961, exh. cat. (Worcester Art Museum, 1961), pp. 76–77, cat. 34 (ill.).

George Maxim Anossov Hanfmann, Roman Art: A Modern Survey of the Art of Imperial Rome (New York Graphic Society, 1964), pp. 103; 187; cat.

98 (ill.).

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

9/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Greek and Roman Portraits in North American Collections Open to the Public: A Survey of Important Monumental

Likenesses in Marble and Bronze which Have Not Been Published Extensively,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 108 (1964), p.

103.

Evelyn B. Harrison, “The Constantinian Portrait,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 21 (1967), pp. 79–96, fig. 31.

James D. Breckenridge, Likeness: A Conceptual History of Ancient Portraiture (Northwestern University Press, 1968), pp. 247–48, fig. 131.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, Roman Imperial Art in Greece and Asia Minor (Harvard University Press, 1968), pp. 58; 356; 364–65, fig. 179.

Wilhelm Von Sydow, Zur Kunstgeschichte des spätantiken Porträts im 4. Jahrhundert n. Chr. (Habelt, 1969), p. 152.

Helga Von Heintze, “Ein spatantikes Madchenportrat in Bonn: zur stilistischen Entwicklung des Frauenbildnisses,” Jahrbuch für Antike und

Christentum 14 (1971), pp. 78–83.

Raissa Calza, Iconografia Romana Imperiale da Carausio a Giuliano (L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1972), pp. 268–69, cat. 181, pl. 94, figs. 331–32.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Roman and Barbarians, exh. cat. (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1976), pp. 110–11, cat. 118 (ill.).

Sandra Knudsen Morgan, “Letter From Boston: Romans and Barbarians,” Apollo 184 (June 1977), p. 499, fig. 8.

Kurt Weitzmann, Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh Century, exh. cat. (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979),

pp. 289–90, cat. 268 (ill.).

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, Greek and Roman Sculpture in America: Masterpieces in Public Collections in the United States and Canada (University

of California Press/J. Paul Getty Museum, 1981), pp. 372–73 (ill.), fig. 323.

Klaus Fittschen and Paul Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts in den Capitolinischen Museen und den anderen kommunalen Sammlungen der

Stadt Rom, vol. 3, Kaiserinnen- und Prinzessinnenbildnisse, Frauenporträts (Zabern, 1983), pp. 65–66, cat. 86, item o.

Karen Alexander and Mary Greuel, Private Taste in Ancient Rome. Selections from Chicago Collections, exh. brochure (Art Institute of Chicago,

1990), cat. 7.

Diana E. E. Kleiner and Susan B. Matheson, I, Claudia: Women in Ancient Rome, exh. cat. (Yale University Press, 1990), p. 173, cat. 128 (ill.).

Bente Kiilerich, Late Fourth Century Classicism in the Plastic Arts: Studies in the So-Called Theodosian Renaissance (Odense University Press,

1993), p. 117.

Cornelius C. Vermeule III, “Roman Art,” in “Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” special issue, Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 20, 1

(1994), pp. 73–74, cat. 51 (ill.).

Demetra Papanikola-Bakirtzi, Everyday Life in Byzantium, exh. cat. (Hellenic Ministry of Culture, 2002), pp. 379–80, cat. 464.

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

10/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

Ioli Kalavrezou, Byzantine Women and Their World, exh. cat. (Harvard University Art Museums/Yale University Press, 2003), p. 83, n. 1.

Karen B. Alexander, “From Plaster to Stone: Ancient Art at the Art Institute of Chicago,” in Recasting the Past: Collecting and Presenting Antiquities

at the Art Institute of Chicago, ed. Karen Manchester (Art Institute of Chicago, 2012), p. 32.

Other Documentation

Examination Conditions and Scientific Analysis

Visible Light

Normal-light and raking-light overalls: Nikon D5000 with an AF-S DX NIKKOR 18–55 mm f/3.5–5.6G VR lens

Normal-light and raking-light macrophotography: Nikon D5000 with an AF Micro NIKKOR 60 mm 1:2.8 D lens

Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Light Fluorescence

Nikon D5000 with an AF-S DX NIKKOR 18–55 mm f/3.5–5.6G VR lens and a Kodak Wratten 2E filter

High-Resolution Visible Light

Phase One 645 camera body with a P45+ back and a Mamiya 80 mm f2.8 f lens. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software

and Adobe Photoshop.

High-Resolution Ultraviolet-Induced Visible Light Fluorescence

Canon EOS1D with a PECA 918 lens and a B+W 420 (2E) filter pack. Images were processed with Phase One Capture One Pro software and Adobe

Photoshop.

Microscopy and Photomicrographs

Visible-light microscopy: Zeiss OPMI-6 stereomicroscope fitted with a Nikon D5000 camera body

Petrographic and thin-section analysis: Leitz DMRXP polarizing microscope equipped with a Leica Wild MPS-52 camera head

Isotope Ratio Mass Spectrometry

Finnigan MAT 5000 mass spectrometer

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

11/51

�2/27/2017

X-Ray Diffraction

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

PANalytical Empyrean diffractometer with vertical goniometer (CuK /Ni at 40 kV, 20 mA)

1) On the marble identification, see Provenance in the technical report.

2) On idealized beauty as a virtue, see Fejfer, Roman Portraits in Context, p. 351; Meyers, “Female Portraiture,” p. 454.

3) On the possibility that this type of band might be composed of fabric, see cat. 5, Portrait Head of a Woman, para. 4.

4) Harrison, “Constantinian Portrait,” p. 88. On the melon coiffure, see Connelly, Portrait of a Priestess, p. 157; Trimble, Women and Visual

Replication, p. 47. On the association of the melon coiffure with portraits of girls and young women and its popularity in the second century A.D., see

Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, p. 86, cat. 118. I thank Simone Kaiser for translating various passages from this

publication.

5) For a discussion of the irregular profile of the bottom edge of the neck, see Method in the technical report. For the advantages of separately

sculpting portrait heads, see Lindner, “Woman from Frosinone,” p. 47.

6) For the second-century dating of the Chicago portrait’s hairstyle, see Harrison, “Constantinian Portrait,” p. 88; Sydow, Zur Kunstgeschichte des

spätantiken Porträts, p. 152; Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 65–66, cat. 86, item o; Fittschen, “Courtly Portraits,”

p. 51 n. 42; Davies, “Portrait of a Woman,” p. 173, cat. 128; Vermeule, “Roman Art,” p. 74, cat. 51; Kiilerich, Late Fourth Century Classicism, pp.

116 n. 374, 117 (here the hairstyle is dated to the second century, while the surface treatment and delicate carving of the face as well as the rendering

of the eyes are dated to the Theodosian period, A.D. 379–95); Manchester and Greuel, “Marble Portrait Head of a Young Woman” (listing previously

assigned dates from the middle of the second to the late fourth century).

7) For the development of the turban coiffure out of Flavian and Trajanic hairstyles, see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3,

p. 63, cat. 84. See also The Turban Coiffure as a Symbol of Virtue for an alternative explanation of the origins of this hairstyle. On the portrait of Diva

Matidia (?) in the Musei Capitolini, Rome (Hadrianic period; 889), see Wegner, Hadrian, Plotina, p. 124, pl. 37 (here listed as located in Galleria 75,

Museo del Palazzo dei Conservatori, Musei Capitolini); Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 9–10, cat. 8, pl. 10. For a

portrait that includes a smaller, slightly sunken example of the Trajanic braided nest, see cat. 5, Portrait Head of a Woman, para. 32, fig. 5.16 and note

67.

8) On the prevalence of the turban coiffure during the Hadrianic period, see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 62–63,

cats. 83–84; Fittschen, “Courtly Portraits,” pp. 42, 44. Klaus Fittschen questioned the extent to which the turban hairstyle was worn during the

Antonine period, noting that it might have been worn into the early part of that period but that this cannot be determined with certainty; see Fittschen

and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, p. 63, cat. 84; p. 65, cat. 85; p. 66, cat. 86, n. 6. However, other scholars have suggested that it

was worn into the Antonine period; see Breckenridge, Likeness, p. 247, fig. 131; Vermeule, Roman Imperial Art in Greece and Asia Minor, p. 365;

Breckenridge, “Head of a Lady,” p. 290, cat. 268; Schade, Frauen in der Spätantike, p. 101.

9) Sabina (A.D. 83/86–136/137), the wife of Emperor Hadrian, wore a variation on the turban coiffure; see Fittschen, “Courtly Portraits,” p. 42. This

variation is apparent in her most widespread portrait type, in which the wavy locks parted over her forehead are pulled back into a loosely wound,

nest-like coil placed on the upper part of the back of her head. For an example, see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp.

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

12/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

10–12, cat. 10. It has been suggested that a portrait of a woman in the guise of Venus Genetrix that incorporates the turban coiffure is a portrait of

Sabina; see Calza, Ritratti greci e romani, pp. 77–78, cat. 124, pl. 72. However, it has also been argued that this portrait depicts a private woman; see

D’Ambra, “Nudity and Adornment,” pp. 107–08. See also Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, p. 62, cat. 83.

10) For examples of portraits in the Musei Capitolini in Rome incorporating the turban coiffure, along with lists of additional examples in other

collections, see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 61–66, cats. 83–86, pls. 104–08.

11) See cat. 5, Portrait Head of a Woman, Roman Female Portraiture. On cultus and hairstyles, see Bartman, “Hair and the Artifice,” pp. 5–6. On the

artificial enhancement of hairstyles, see Olson, Dress and the Roman Woman, pp. 70–76.

12) For hairstyle variations as a means of allowing women to distinguish themselves from their peers, see Bartman, “Hair and the Artifice,” p. 22.

Contra Bartman, Eve D’Ambra argued that certain hairstyles, such as the Flavian toupet coiffure, were chosen by women in order to reflect their

identification as members of a group; see D’Ambra, “Beauty and the Roman Female Portrait,” p. 172. In the turban coiffure, variations might include

the number and thickness of braids, the manner in which the braids are stacked (i.e., in a cylindrical or a funnel shape), and the positioning of the

turban on the head. Additionally, there are also differences in the arrangement of the locks over the forehead (if present) and of the braids and other

tresses in the back, below the turban.

13) On this bust, see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 61–62, cat. 83, pls. 104–05, with a list of additional

comparisons.

14) With regard to the shape and orientation of the turbans, that of the Capitoline portrait projects out and up in the back, while the braids of the

Chicago portrait hew more closely to the contour of the head. For an arrangement of the turban coiffure that is strikingly similar to that of the

Capitoline portrait, particularly in terms of the placement and arrangement of braids at the back of the head, see the under-life-size bronze bust of a

woman in the Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, N.J. (Hadrianic period, c. A.D. 135; 1998-419), in Meyer, “Portrait Bust of a Woman.”

15) Amanda Claridge indicated that the carving of the pupil and iris of the eye began as a regular practice from A.D. 130 onward; see Claridge,

“Marble Carving Techniques,” p. 109. Jane Fejfer suggested that the carving of the iris and pupils “appeared tentatively” during the early part of the

Hadrianic period; see Fejfer, Roman Portraits in Context, p. 278. See also Kleiner, Roman Sculpture, p. 238; Smith, “Cultural Choice and Political

Identity,” p. 62.

16) Davies, “Portrait of a Woman,” p. 173, cat. 128.

17) For the association of heavy, seemingly sleepy eyelids with Antonine portraiture, see Kleiner, Roman Sculpture, pp. 270–71. For the Antonine

dating of upper lids that extend past the outside corners of the lower lids, see Van Voorhis and Lenaghan, “Bust and Head of a Young Woman.” For

another portrait in the Art Institute’s collection that includes the heavy eyelids characteristic of the Antonine period, see cat. 8, Portrait Bust of a

Woman.

18) Harrison, “Constantinian Portrait,” p. 88. For a Trajanic example of this faceted treatment of the eyebrows, see the portrait of a woman (perhaps

Plotina) in the Musei Capitolini, Rome (440), in Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 7–8, cat. 6, pls. 7–8. For a late

Hadrianic example, see Sabina in the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen (774), in Johansen, Roman Portraits, vol. 2, pp. 116–17. For an early

Antonine example in the Art Institute’s collection, see cat. 8, Portrait Bust of a Woman, fig. 8.12.

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

13/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

19) On this bust, see Korkuti, Shqiperia arkeologjike, p. 14, pl. 88. Although Muzafer Korkuti dated this portrait to the second or third century A.D., a

date in the late Hadrianic or early Antonine period seems reasonable due to the use of the turban coiffure, the articulated irises and pupils, and the

heavy eyelids that resemble those found in portraits of the Antonine period.

20) Evelyn B. Harrison suggested that the Chicago portrait might have been from Asia Minor, but did not expound on this possibility; see Harrison,

“Constantinian Portrait,” p. 88. Cornelius C. Vermeule suggested that the portrait was found in Athens but did not cite any evidence regarding this

possible findspot; see Vermeule, “Two Masterpieces,” p. 6.On the association of nearly circular, deeply drilled pupils with an origin in the Greek East,

in contrast to the association of pupils in the shape of a bean or a crescent with an origin in the Latin West, see Fittschen, “Unidentified but

Important,” p. 9. See also cat. 8, Portrait Bust of a Woman, para. 19.

21) For a close comparison to the Chicago portrait that is also made of Dokimeion marble, see the slightly under life-size portrait bust of a woman

wearing a turban coiffure, which was found in modern-day Chania (ancient Kydonia) (c. A.D. 410; Archaeological Museum of Chania, Crete, Λ

3176), in Tzanakaki, “Bust of a Lady.” Much like the Chicago work, this sculpture has also been dated variously from the second century through late

antiquity because of its hairstyle and the sensitive rendering of its facial features. On the basis of the use of Dokimeion marble and the high quality of

the carving, it has been suggested that the portrait might have been imported into Crete following its creation in a workshop in Asia Minor,

specifically in Aphrodisias. Could the Chicago portrait have been produced under similar circumstances? For an overview of the quarries of

Dokimeion and their importance to the Roman marble trade, see Long, “Urbanism, Art, and Economy,” pp. 133–72. For an overview of issues

surrounding the study of Roman sculpture produced in Asia Minor, see Ng, “Asia Minor.”

22) See Provenance, para. 37 in the technical report.

23) Two portraits of women wearing turban coiffures in the Musée du Louvre in Paris (Ma 2342 and Ma 2275) are similarly dated to A.D. 130/40, in

part due to the combination of their hairstyles with other features evoking the early Antonine period; see Kersauson, Catalogue des portraits romains,

pp. 180–81, cat. 76; pp. 184–85, cat. 78. For a bust of a woman in the Musei Capitolini in Rome (201) that exhibits a hairstyle incorporating Hadrianic

and Antonine features, which might have been created in this same period, see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 76–

77, cat. 100, pls. 125–27.

24) For an early fourth-century date, see Vermeule, “Two Masterpieces,” pp. 6, 9–10; Milkovich, Roman Portraits, p. 76, cat. 34; Hanfmann, Roman

Art, p. 103, cat. 98; Vermeule, “Greek and Roman Portraits in North American Collections,” p. 103; Breckenridge, Likeness, p. 247, fig. 131; p. 248;

Vermeule, Roman Imperial Art in Greece and Asia Minor, pp. 356, 364–65; Calza, Iconografia romana imperiale, pp. 268–69, cat. 181, pl. 94;

Vostchinina, Le portrait romain, p. 194, cat. 79; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Romans and Barbarians, p. 110, cat. 118; Morgan, “Letter from

Boston,” p. 499, fig. 8; Vermeule, Greek and Roman Sculpture in America, p. 372, no. 323. For a late fourth-century date (i.e., between 360 and 400),

see Heintze, “Ein spätantikes Mädchenporträt,” pp. 78 (group 5, no. 4), 79, pls. 13d, 15a (A.D. 360/90); Breckenridge, “Head of a Lady” (A.D.

370/80); Ledig Heuser, “Head of a Female Figure,” p. 85 n. 1, cat. 27 (in comparison to a female portrait dated to A.D. 375/400); Manchester and

Greuel, “Marble Portrait Head of a Young Woman” (listing previously assigned dates from the middle of the second to the late fourth century).

25) The hypothesis of a fourth-century revival of the second-century turban coiffure was first proposed by Tamara Uschakoff, who in 1928 dated a

portrait of a woman in the collection of the State Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia ( Р-3581), to the first quarter of the fourth century.

(As of this writing, this is still the date assigned to the portrait by the museum; see http://www.hermitagemuseum.org/wps/portal/hermitage/digitalcollection/06.+Sculpture/220038/?lng.) Uschakoff’s dating was based in part on a comparison of the Hermitage portrait to certain coin portraits of

Constantine’s mother, Helena; see Uschakoff, “Ein römisches Frauenporträt.” Subsequently other scholars dated numerous portraits with the turban

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

14/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

hairstyle to late antiquity, spurring further debate; see Schade, Frauen in der Spätantike, pp. 98–99; Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen

Porträts, vol. 3, p. 66, cat. 86.

26) A study of more than fifty female portraits wearing some version of the turban coiffure was published by Helga von Heintze in 1971, at which

time she dated the various portraits to the fourth and fifth centuries A.D.; see Heintze, “Ein spätantikes Mädchenporträt.” However, Heintze’s

divisions have been called into question, as have her suggested dates for the portraits; see Kiilerich, Late Fourth Century Classicism, p. 116. In

support of second-century dates for a number of these portraits, see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 64–66, cats. 85–

86.

27) Although this decrease in the production of new portraits has been attributed to a variety of economic, political, artistic, and religious factors, it

appears that it was connected primarily to broader changes in forms of representation and communication. For a recent overview of the decline of new

portrait statuary in late antiquity, see Witschel, “Late Antique Sculpture,” pp. 325–28. The number of women’s portraits decreased significantly from

the mid-third century onward; see Meyers, “Female Portraiture,” p. 458.

28) Kiilerich, Late Fourth Century Classicism, p. 115.

29) Vermeule was the first scholar to identify the subject of the Chicago portrait as Constantia, who was also the daughter of Emperor Constantius I

(r. A.D. 293–306) and the wife of Constantine’s coemperor, Licinius I (r. A.D. 308–24); see Vermeule, “Two Masterpieces,” pp. 6, 9–10. For

additional identifications as a possible portrait of Constantia, see Milkovich, Roman Portraits, p. 76, cat. 34; Hanfmann, Roman Art, p. 103, cat. 98;

Breckenridge, Likeness, p. 247, fig. 131; p. 248; Vermeule, Roman Imperial Art in Greece and Asia Minor, pp. 356, 364–65; Vermeule, Greek and

Roman Sculpture in America, p. 372, no. 323.

30) For the coin of Constantia, see Pridik, “Neuerwerbungen römischer Münzen,” p. 76, no. 12, pl. 3, 12; Delbrueck, Spätantike Kaiserporträts, p. 86,

pl. 11; Heintze, “Ein spätantikes Mädchenporträt,” p. 63; Schade, Frauen in der Spätantike, p. 45 (identified here as a follis). For a comparison

between the Chicago portrait and the coin of Constantia, see Vermeule, “Two Masterpieces,” p. 10; Vermeule, Roman Imperial Art in Greece and Asia

Minor, p. 364. Vermeule did not illustrate the coin type in either of his publications but rather cited Richard Delbrueck’s book. For an argument that

the hairstyle depicted in the numismatic portrait of Constantia does not resemble that of the Chicago portrait, see Harrison, “Constantinian Portrait,” p.

88.

31) Milkovich, Roman Portraits, p. 76; Hanfmann, Roman Art, p. 103, cat. 98; Breckenridge, Likeness, p. 247, fig. 131; p. 248.

32) On the possibility that the subject was a member of Constantine’s family, see Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Romans and Barbarians, p. 110, cat.

118 (“Portrait of a lady of Constantine’s family, possibly Constantia”); Morgan, “Letter from Boston,” p. 499.

33) For an overview of the distinctions between fourth-century and second-century hairstyles, see especially Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der

römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 64–65, cat. 85; p. 66, cat. 86. See also Kiilerich, Late Fourth Century Classicism, p. 116; Schade, Frauen in der

Spätantike, p. 99; Harrison, “Constantinian Portrait,” p. 88.

34) On the “Zopfkranzfrisur,” see Schade, Frauen in der Spätantike, pp. 96–98. On the portrait of Helena, see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der

römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 35–36, cat. 38, pls. 47–48. On the possibility that this portrait and four others depicting Helena were recarved from

earlier portraits of empresses, including Faustina the Elder (A.D. 100–140/141) and Faustina the Younger (A.D. 125/130–175), see Prusac, From Face

to Face, pp. 73, 156–57, cats. 482–86, pls. 139–40, figs. 151a–d, 152a–b. For a reconsideration of the hairstyle of the portrait of Helena in the Musei

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

15/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

Capitolini, which might at one time have included features of the “Scheitzelzopffrisur” (parted braid hairstyle), specifically the locks over the nape of

the neck that turn upward and are woven into braids covering the back of the head, see Arata, “La statua seduta.”

35) On this portrait head, see Schade, Frauen in der Spätantike, p. 172, cat. I 7, pl. 26, with additional bibliography.

36) For a similar example, see the portrait head of a young woman in the Museo Nazionale Romano, Rome (Constantinian period; 61632), in Schade,

Frauen in der Spätantike, pp. 172–73, cat. I 8, pl. 27. Some late antique portraits with the Zopfkranzfrisur preserve a further variation in the form of

locks of hair over the nape of the neck that turn upward in small loops, creating a coiffure that resembles an omega (Ω); see Schade, Frauen in der

Spätantike, p. 96.

37) Marina Prusac identified large eyes and a forward orientation as two of the common denominators of late antique portraiture; see Prusac, From

Face to Face, p. 59. Heintze suggested that a discussion of late antique portraits must begin with the eyes, which she argued offer a more secure

chronological classification than the hairstyle; see Heintze, “Ein spätantikes Mädchenporträt,” p. 62.

38) For the modern viewer, this is often taken to signify a strong interior spirituality or psychology on the part of the subject, which has frequently

been connected to the rise of Christianity in late antiquity. On this point, see especially L’Orange, Studien zur Geschichte; Kitzinger, Byzantine Art in

the Making. On the subjective nature of such psychological interpretations, see Prusac, From Face to Face, p. 60. More recently, the emphasis on the

eyes in late antique portraits has been attributed instead to a symbolic claim to numerous positive qualities, such as vision, strength, knowledge,

justice, energy, and personal intensity, depending on the broader context in which the image was displayed; see Smith, “Public Image of Licinius I,”

pp. 198–201; Smith, “Late Antique Portraits in a Public Context,” pp. 182–89.

39) Vermeule, “Two Masterpieces,” p. 10; Milkovich, Roman Portraits, p. 76, cat. 34; Vermeule, Roman Imperial Art in Greece and Asia Minor, p.

364. They are also described as “enlarged eyes”; see Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Romans and Barbarians, p. 110, cat. 118.

40) For the “visionary gaze,” see Breckenridge, “Head of a Lady,” p. 289, cat. 268. For the “heavenward glance,” see Hanfmann, Roman Art, p. 103.

The portrait has also been described as having an “abstracted, staring expression”; see Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Romans and Barbarians, p. 110,

cat. 118. See also Davies, “Portrait of a Woman,” p. 173, cat. 128, which describes the portrait’s “upward, distant gaze.”

41) On the portrait of Fausta, see Kersauson, Catalogue des portraits romains, pp. 524–25, cat. 250.

42) Kiilerich, Late Fourth Century Classicism, p. 117. Kiilerich noted that the facial features of the portrait resemble those of portraits dated to the

Theodosian period. Klaus Fittschen and Paul Zanker similarly suggested that some portraits dated to late antiquity might have been created from

earlier images; see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, p. 64, cat. 85. For an example, see Roman Woman in the Ny

Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen (Hadrianic period, reworked in the 4th century; 710), in Johansen, Roman Portraits, vol. 3, pp. 196–97, cat. 87. For

an example of a head (perhaps from an ideal statue) recarved into a female portrait with this hairstyle (Constantinian period; Museo Nazionale

Romano, Rome, 61632), see Felletti Maj, I ritratti, pp. 157–58, cat. 316; Schade, Frauen in der Spätantike, pp. 172–73, cat. I 8, pl. 26. On the

recarving of portraits, see especially Prusac, From Face to Face; and, most recently, Varner, “Reuse and Recarving.” For examples of portraits in the

Art Institute’s collection bearing traces of ancient recarving, see cat. 5, Portrait Head of a Woman; cat. 15, Portrait Head of a Man; cat. 16, Portrait

Head of a Youth; and cat. 19, Portrait Head of a Philosopher.

43) For an overview of recarving methods employed in reworked portraits and diagnostic elements indicating recarving, see Prusac, From Face to

Face, pp. 79–92.

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

16/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

44) On the characteristics of recarved eyes, see Prusac, From Face to Face, pp. 87–89.

45) On the similarity of the turban coiffure to hairstyles of priestesses, see Calza, “Statua iconica femminile da Ostia,” p. 201; Harrison,

“Constantinian Portrait,” p. 88. On the similarities to the headdresses or hairstyles of the Vestal Virgins, see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der

römischen Porträts, vol. 3, p. 63, cat. 84; p. 66, cat. 86; Schade, Frauen in der Spätantike, p. 101. Additional studies of the portraits of the Vestal

Virgins include Jordan, Der Tempel der Vesta, pp. 43–56, pls. 8–10; Van Deman, “Value of the Vestal Statues”; Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der

römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 92–94, cats. 134–35, pls. 160–61; Walker, “Portrait Head of a Life-Sized Statue of a Vestal”; Lindner, “Vestal Virgins

and Their Imperial Patrons,” pp. 64–97; Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins.

Some Roman priestesses appear to have worn, rather than popular hairstyles, “nonfashion” coiffures with their hair hanging in long tresses or pulled

back loosely and with locks hanging down in a manner resembling that of images depicting goddesses. For example, see the female head wearing a

lunate diadem (identified here as a stephane), which might depict a priestess of Aphrodite, from the Hadrianic baths at Aphrodisias, in modern-day

Turkey (2nd/3rd century A.D.; 66-270), in Dillon, “Female Head Wearing Stephanē.”

46) Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins, pp. 100–02 (on the infula), 164–86 (on the infula and turban coiffure); see also p. 174 for Lindner’s use of

the term nonelite to refer specifically to women of equestrian rank and members of the middle class. John R. Clarke summarized the basic distinction

between elite and nonelite members of Roman society as follows: “An elite Roman possessed the four prerequisites necessary to belong to the upper

strata of society: money, important public appointments, social prestige, and membership in an ordo. (The ordines are those of senator, decurion, and

equestrian.) The non-elite person lacked one or more of the four prerequisites.” Clarke, Art in the Lives of Ordinary Romans, p. 4. For an overview of

the use of the modern term middle class in scholarship on ancient Roman society and culture, see Mayer, Ancient Middle Classes, pp. 1–21.

On this portrait head of a Vestal Virgin in the British Museum, London (c. 2nd century A.D.; 1979,1108.1), see Walker, “Portrait Head of a Life-Sized

Statue of a Vestal”; see also Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins, pp. 130–32, cat. 2, figs. 26–27.

47) For additional discussion of the infula, see Cleland, Davies, and Llewellyn-Jones, Greek and Roman Dress, p. 96; La Follette, “Costume of the

Roman Bride,” p. 57; Fantham, “Covering the Head at Rome.”

48) Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins, pp. 184 (on the quoting of the infula to suggest sanctitas), 187, 197 (on the association of sanctitas with

chastity). Fittschen observed that the turban coiffure in a portrait of a woman on a modern bust in the Musei Capitolini in Rome (late Hadrianic

period; 676) features locks of hair encircling the head that are smooth rather than braided. These locks appear to resemble the infula worn by Vestal

Virgins; see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 65–66, cat. 86, pl. 108.

49) For an example of a portrait showing the seni crines hairstyle beneath the infula, see the head of a Vestal Virgin in the Antiquario Forense, Rome

(A.D. 130/50; 634, alternate no. 424492), in La Follette, “Costume of the Roman Bride,” p. 58, fig. 3.4; p. 59; Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins,

pp. 134–35, cat. 5, figs. 32–34. Portraits of the Vestals that depict the seni crines hairstyle do not always include six braids; see Lindner, Portraits of

the Vestal Virgins, pp. 116–17.

50) On the literary and visual evidence of the seni crines hairstyle, which is often obscured by the infula in portraits, as well as its association with its

wearer’s virginal state, see Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins, pp. 114–18. On the literary evidence, see also La Follette, “Costume of the Roman

Bride,” pp. 56–57. Henri Jordan proposed that the infula worn by the Vestal Virgins functioned as a cloth substitute for the seni crines hairstyle; see

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

17/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

Jordan, Der Tempel der Vesta, pp. 47–48. For additional scholarly acceptance of this hypothesis, see La Follette, “Costume of the Roman Bride,” p.

59; Walker, “Portrait Head of a Life-Sized Statue of a Vestal,” p. 17.

51) Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins, p. 184.

52) Lindner employed the term elite to refer specifically to women of senatorial rank, viewing the women of equestrian status, the next lower rank, as

members of the nonelite; Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins, pp. 173–74; see also p. 182 for the adoption of the turban coiffure by elite women.

53) For an overview of the public roles of women in the Latin West, including the roles of priestess and benefactress, see Hemelrijk, “Public Roles for

Women.” For the public prominence of imperial cult priestesses in the Latin West, see Hemelrijk, “Local Empresses,” p. 343. On women’s public

roles in the Greek East, see MacMullen, “Women in Public”; Bremen, Limits of Participation. For the possibility that the turban coiffure was worn by

priestesses to visually evoke the infula of the Vestals, see Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins, p. 182. For an example of a public honorific statue

from a religious sanctuary that depicts a priestess wearing the turban coiffure, see the portrait of Minia Procula, who was named flaminica perpetua

(public priestess appointed for life), from Bulla Regia in modern-day Tunisia, now in the Musée du Bardo in Tunis (2nd century A.D.; C 1020). For

this portrait, see Fittschen and Zanker, Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, p. 63, cat. 84, item l; Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins, p. 182.

54) On this portrait, see Comstock and Vermeule, Sculpture in Stone, p. 224, no. 355; Vermeule and Comstock, Sculpture in Stone and Bronze, p. 115,

no. 355; Kondoleon, Classical Art, p. 46.

55) On the palla, see Olson, Dress and the Roman Woman, pp. 33–36; Cleland, Davies, and Llewellyn-Jones, Greek and Roman Dress, pp. 136–37.

The veil was also worn by brides and matrons and thus was associated with “wifely virtues”; see Bartman, Portraits of Livia, pp. 44–45. See also

Sebesta, “Symbolism in the Costume of the Roman Woman,” pp. 48–49. On the rarity of depictions of women burning incense, see Lindner, Portraits

of the Vestal Virgins, pp. 244–45.

Additional portraits depicting veiled women wearing the turban coiffure (although not necessarily identified as priestesses) include the following: (1)

statue of a woman, Small Herculaneum Woman type (early Hadrianic period; Musei Capitolini, Palazzo Braschi, Rome), in Fittschen and Zanker,

Katalog der römischen Porträts, vol. 3, pp. 63–65, cat. 85, pl. 107; (2) statue of a woman, Large Herculaneum Woman type, from Philadelphia

(modern-day Alaşehir, Turkey) (Trajanic or Hadrianic period; Manisa Müzesi, Turkey, 1298), in Inan and Rosenbaum, Roman and Early Byzantine

Portrait Sculpture, p. 163, cat. 214, pls. 115, 2, and 118, 1–2; (3) statue of a woman, Pudicitia type, from Ostia (Antonine period or 3rd century;

Museo Ostiense, Ostia, Italy, 22), in Calza, Iconografia romana imperiale, pp. 251–52, cat. 165, pls. 87–88, figs. 307–10. Kathrin Schade has

suggested that popular female statuary types such as those noted above, each of which depicts the figure standing in a closed, seemingly restrained

pose, might have conveyed a message of feminine virtue, much like the turban coiffure; see Schade, Frauen in der Spätantike, p. 102. However,

Jennifer Trimble has argued that the self-contained gestures of such statuary types “do not seem to be a specifically feminine characteristic, connoting,

for example, modesty,” given the use of closed poses in male portraiture; see Trimble, Women and Visual Replication, p. 165. For an overview of the

main statuary types used in portraits of women, which include the three types mentioned here, see Fejfer, Roman Portraits in Context, pp. 335–44.

56) For the statue’s discovery in a tomb, see Lindner, Portraits of the Vestal Virgins, p. 246, with bibliography.

57) Harrison, “Constantinian Portrait,” p. 88.

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

18/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

58) Calcite (the hexagonal form -CaCO3) is the most thermodynamically stable form of calcium carbonate. Other forms are the orthorhombic CaCO3, known as the mineral aragonite, and -CaCO3, known as the mineral vaterite. See Ropp, Encyclopedia of the Alkaline Earth Compounds, pp.

359–70. Calcite is composed of 56 percent calcium oxide (CaO) and 44 percent carbon dioxide (CO2), although manganese (Mn), iron (Fe), or

magnesium (Mg) may be present in trace amounts in place of calcium. See Pough, Field Guide to Rocks, p. 145.

59) The thin-section petrography and X-ray diffraction were performed at the Laboratorio di Analisi dei Materiali Antichi (LAMA), Università IUAV,

Venice, by Lorenzo Lazzarini, Director, LAMA. The purpose of the minero-petrographic analysis was to determine the following parameters: (1) the

type of fabric (either homeoblastic or heteroblastic, the former consisting of grains of roughly equal dimensions and the latter consisting of grains of

variable dimensions), which is directly related to the type of metamorphism (equilibrium, nonequilibrium, retrograde, or polymetamorphism); (2) the

boundary shapes of the calcite/dolomite grains, which are also correlated with the types of metamorphic events that generated the marble; (3) the

maximum grain size, a parameter that has diagnostic significance because it is linked to the grade of metamorphism achieved by the marble; and (4)

the qualitative and semiqualitative presence of accessory minerals, which are sometimes of diagnostic value. In the formulation of the petrographic

description, previous specific studies of the most important “major” ancient marbles (Gorgoni et al., “Reference Database”; Lazzarini, Moschini, and

Stievano, “Contribution to the Identification”), other archaeometric studies of “minor” marbles, and seminal treatises on petrotectonics (e.g., Spry,

Metamorphic Textures) were taken into consideration. Lazzarini, “Report on the Results,” pp. 1–2. This essay is greatly indebted not only to Lorenzo

Lazzarini’s analysis, which facilitated a better understanding of this object in the newly cast light of its secure attribution with respect to marble type

and provenance, but also to his graciousness and generosity in sharing the vast knowledge and wisdom acquired over the course of his decades-long

career.

60) The degree of crystal decohesion may be determined in thin section by observing whether the sample has very marked crystal boundaries

(indicating little or no decohesion), intercrystalline microcracks, intracrystalline microcracks, or inter- and intracrystalline microcracks (indicating

very strong decohesion). Lazzarini, “Report on the Results,” p. 3.

61) For further information on the specific role of micrite in the classification of carbonate rocks, see Folk, “Practical Petrographic Classification of

Limestones”; and Dunham, “Classification of Carbonate Rocks.” The Folk and Dunham classifications are the two most widely used descriptors for

limestones; in both, the subdivisions are determined by the matrix composition, e.g., micrite.

62) The identification of Dokimeion marble with the naked eye is challenging, because it can easily be mistaken for good-quality Carrara or Pentelic

marble. Isotopic analysis is normally sufficient to confirm the identification, although there may be some overlap with Carrara. In such cases, thinsection petrography may be helpful, since Dokimeion marble shows a much more strained fabric than Carrara, commonly with deformed

polysynthetic twins. Lazzarini, “Report on the Results,” p. 6.

63) A certain amount of marble from Dokimeion seems to have been exported to imperial Rome, especially for statuary, because of its very fine grain

and good carving properties. Marmor docimenum was already used in Hellenistic times (for example, at Tralles); it continued to be exploited in

Roman and Byzantine times, for statuary as well as sarcophagi (for example, of the Sidamara type), and is still quarried today. The quarries were

probably under the control of the nearby ancient village of Dokimeion, in the province of Synnada in ancient Phrygia, hence its other ancient names,

marmor synnadicum and marmor phrygium. Lazzarini, “Report on the Results,” p. 6. For further reference, see Monna and Pensabene, Marmi

dell’Asia Minore, pp. 29–77; and Pensabene, “Cave de marmo bianco.” For information on the quarries at Dokimeion, see Fant, Cavum antrum

Phrygiae, pp. 17–320.

https://publications.artic.edu/roman/api/epub/480/494/print_view

19/51

�2/27/2017

Cat. 7 Portrait Head of a Young Woman

64) The stable isotope ratio analysis was done at the Isotopen Labo, Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg (FAU), Germany, and

interpreted by Lorenzo Lazzarini, Director, LAMA. Isotopic characterization has proved to be very useful in the identification of ancient marble. Its

use is becoming more and more widespread owing to its outstanding sensitivity, the small quantity of material necessary for the analysis, and the

availability of a rapidly growing isotopic database, often associated with other laboratory methodologies (Attanasio, Brilli, and Ogle, Isotopic

Signature of Classical Marbles; Barbin et al., “Cathodoluminescence”; Gorgoni et al., “Reference Database”; Lazzarini, “Archaeometric Aspects of

White and Coloured Marbles”), that permits increasingly trustworthy comparisons, especially if the isotopic data are evaluated together with the

minero-petrographic results from the same samples, as in the present study. The present study used reference data from petrographic databases as well

as data compiled from thin-section samples taken in fifty ancient Mediterranean marble quarries. Lazzarini, “Report on the Results,” pp. 2, 3.

Isotopic analysis was carried out on the carbon dioxide derived from a small portion (20–30 mg) of the powdered sample obtained through dissolution

by phosphoric acid at 25°C in a vacuum line, according to the procedure suggested by McCrea, “Isotopic Chemistry of Carbonates,” and Craig,

“Isotopic Standards for Carbon and Oxygen.” The resulting carbon dioxide was then analyzed using mass spectrometry. The mass spectrometer is

fitted with a triple collector and permits the measurement of both isotopic ratios (13C/12C and 18O/16O) at the same time. The analytical results are

conventionally expressed in δ units, in parts per thousand, in which δ = (Rsample/Rstd – 1) × 1000, and Rsample and Rstd represent the isotopic ratios of

oxygen and carbon in the sample and in the reference standard, respectively. The standard adopted is PDB, or δ13C, for both oxygen and carbon. The

PDB standard for isotope ratio measurements in carbonates is the rostrum of the Belemnitella americana, a Cretaceous marine fossil from the Pee Dee

Formation in South Carolina. Lazzarini, “Report on the Results,” p. 2.

65) For a fuller discussion of the use and handling of the tools mentioned in this section (including the subtle difference imparted to the carving by

altering the strike angle or hold of the tool), as well as diagrammatic representations of each tool, see Rockwell, Art of Stoneworking, pp. 31–68. For a

brief discussion of the artisans themselves (their training, workshops, status, etc.) as well as a more concise summary of marble-working tools and

techniques, see Claridge, “Marble Carving Techniques.”

66) The topic of joining heads and appendages onto marble sculpture, during either initial fabrication or subsequent alteration, is a rich and complex

one. For a thorough explanation of the ways in which heads and other appendages were affixed either by pinning or by the use of sockets and tenons,

as well as the chronology of these methods, see Claridge, “Ancient Techniques of Making Joins.” Diagrammatic representations of the many shapes

and profiles of tenons commonly found on ancient marble statuary can be found on page 145 of Claridge’s text. For further information, see Claridge,

“Marble Carving Techniques.”There is a very remote possibility that the base of the neck could have terminated in a flat surface. Were this the case,

the object would most likely have been a replacement head. For further information on the technical aspects of removing, fitting, and securing