Title: Abjection and Disgust in a Ritual of Defilement: N.Nikolaides’ Singapore Sling

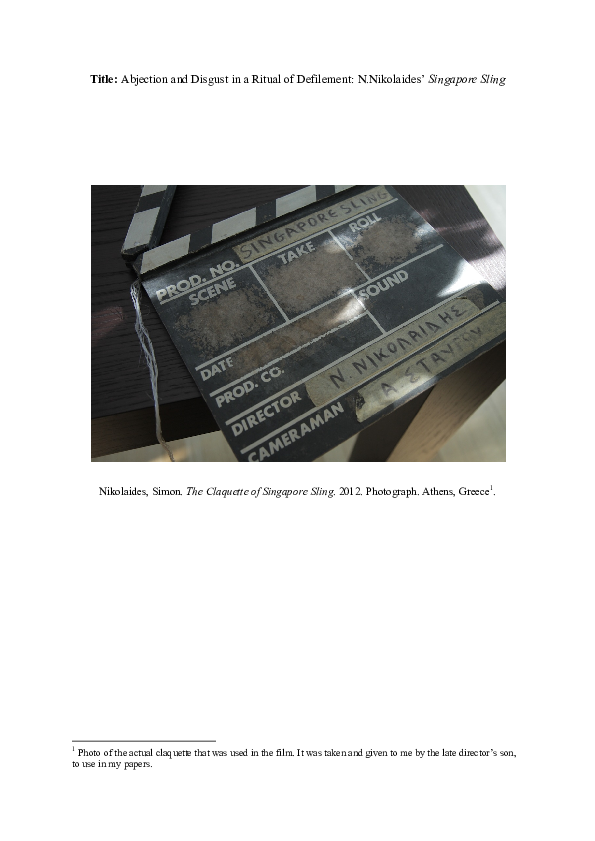

Nikolaides, Simon. The Claquette of Singapore Sling. 2012. Photograph. Athens, Greece1.

1

Photo of the actual claquette that was used in the film. It was taken and given to me by the late director’s son,

to use in my papers.

�Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of: MA in Cultural Studies

Student Name: Maria Daskalaki

Student Number: 200641173

Module code and title: Dissertation ARTF5910M

Supervisor: Barbara Engh

Date of submission: September 3rd , 2012

Word count: 14.988

University of Leeds

Department of Fine Art, History of Art and Cultural Studies

The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has

been given where reference has been made to the work of others.

�ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This is a potentially endless part of the dissertation, since I feel I owe so much to so many

people, that I would not even know where to begin. But for the sake of brevity and

consideration of the readers’ time, I would just like to thank my BA professor Nikolas Kontos

for his delightful teaching and encouragement to pursue postgraduate studies. I also owe a lot

to my professor and supervisor Barbara Engh who has been remarkably inspiring, helpful and

supportive throughout this MA course. The entire department of Fine Art, History of Art and

Cultural Studies has also been precious this year. I would additionally like to express my

gratitude to the late director’s Nikos Nikolaides’ wife and son, Marie-Louise and Simon

Nikolaides for their cooperation and the helpful material that they provided. Of course I could

never neglect my family’s, friends’ and partner’s support which has been precious and

finally, I am grateful to late Annie Redman King for her Scholarship, without which I would

not be writing this very dissertation.

ABSTRACT

After reviewing the theory and history of Disgust which has only taken off since 1990, this

paper will set to explore why and how N. Nikolaides’ Singapore Sling is disgusting and it

will follow a revision of the theory of Abjection as well as its further appropriation and

developments. Furthermore, there will be an attempt to correlate Disgust with Abjection and

by some means enrich the theory of the latter. The theory will be then applied to film and will

be used in order to explore in what ways Singapore Sling could be considered abject(ive) and

a ‘ritual of defilement’.

�Table of Contents

Introduction.........................................................................................................

1

Chapter One: Disgusting Singapore Sling........................................................

6

From Core to Moral Disgust

The CAD Hypothesis Organisation

How and Why Singapore Sling is Disgusting

Chapter Two: Abject(ive) Singapore Sling.......................................................

16

The Theory and origins of Abjection

Abjection and Disgust: The Common Ground

Filmic Representationality of Abjection

How is Singapore Sling abject(ive)?..............................................................

24

1. Unstable Borders and Areas of Ambiguity; the Composite.....................

24

Boundaries between Living and Dead

Boundaries between Love and Destruction

Boundaries between Clean and Unclean

Boundaries between Male and Female

The Composite

2. Images of Pollution and Disgust...............................................................

32

3. The Maternal and/or the Female Body.....................................................

34

4. Other Abjective Qualities.........................................................................

38

Fetishism/Perversion

The Liar, the Criminal

The Abject Always Returns

5. How is the Film Itself, Abject?.................................................................

42

Chapter Three: A Ritual of Defilement............................................................

43

Conclusion...........................................................................................................

49

Figures.................................................................................................................

53

Bibliography........................................................................................................

72

�List of Illustrations

Stills from Singapore Sling

Figure 1

The Mummy-Father

52

Figure 2

The Chauffeur’s Hand Pleading For One Last Time

52

Figure 3

The Detective With a Bullet in his Shoulder.

53

Figure 4

The Detective in The Mother’s Clothes and Make-up

53

Figure 5

The Mother is Feeding the Detective Chewed Food.

54

Figure 6

The Paraphilias

55

Fig. set 2:

Vomiting as a Part of the Family Dinner

57

Fig. set 3:

The Gun Changes Hands and Gets Hidden in a Sex Scene

58

Fig. set 4:

Viscera and a Pulsating Heart

60

Fig. set 5:

The Bourgeois House and Clothing

61

Fig. set 6:

The Water Surrounds Death

63

Fig. set 7:

Placing the Clean and the Dirty Together

65

Fig. set 8:

Blood

66

Fig. set 9:

The Detective Unfed, Unwashed, with Cracked Lips and

Bleeding

68

Fig. set 10:

Masturbation with a Kiwi Fruit

69

Fig. set 11:

Accentuated Feminisation of Internal Organs

70

�1

Abjection and Disgust in a Ritual of Defilement: N.Nikolaides’ Singapore Sling

Introduction

Singapore Sling: The Man Who Loved a Corpse (1990), is a film that was aiming -according

to its creator Nikos Nikolaides12- to represent Greece of the decade that preceded it. The

1980s came after the end of the seven year dictatorship in Greece (1967-1974) and hopes had

been raised then, regarding the establishment of a socialist regime. Those hopes have been

often characterised as collective illusions, because communism seemed as an absolute effect

of a cause. People were under the impression that Greece would turn into a socialist paradise.

Especially after the United States lost the Vietnam War those delusions as well as the

collective chimera were intensifying beyond control and politicians of the time were

encouraging them (Tsakoniatis 37). Therefore the 1980s in Greece were a time when the

country started negotiations with foreign nations in Europe, borrowed money and gave it to

the people. Education and Health were free for all, taxes were next to none and therefore the

Greeks, partly influenced by the rising European Union and partly due to their idiosyncrasy at

the time, quickly turned the socialist promise into a capitalist funfair of uncontrollable

spending sprees (Tsakoniatis 37).

1

All the quotes from interviews that feature in this paper were originally given in Greek and are translated into

English by me. Some of them lack the actual source, interviewer name or date, because they were given to me in

digital, scanned form by the director’s wife and therefore that data was not properly included for all.

This particular claim is found in the interview by Nikos Kavvadias, cited in the bibliography.

2

Biography taken from the official website:

Nikos Nikolaidis, the multi-award winning director and writer, was born in Athens on the 25th of October 1939.

His directorial debut began with the short film: Lacrimae Rerum 1962, and his official entrance into world of

filmmaking was in 1975, with the feature film Eurydice .Β.Α 2037. Aside from film directing, Nikolaidis has

worked for a record company and has put his signature on more than 200 television commercials. He is the only

Greek filmmaker to have been awarded five times as "Best Director" at the Thessaloniki Film Festival, yet never

for the "Best Film" category. He passed away on the 5th of September 2007.

�2

More specifically, in the 80s the Greek society is getting familiar with envy,

competition and the concept of ‘social status’. New money, consumerism and the struggle to

become ‘civilised like the others’ are the reasons why the lifestyle started to get westernised.

This led to a diversity that is today experienced as inequality. Moreover, the Greek home

turns from a space of food preparation to a space of food consumption, since Greece is

introduced to pizza and the food delivery service (Vailakis). There is next to zero taxation on

the big businesses or the wealthy, and tax evasion of the lower middle class is met with

tolerance. Everyone is happy in the 1980s, because no one knows that due to lack of taxation

the country is borrowing more and more money. The people are content and the political

system survives because the citizens can enjoy a state that does not impose, but works in

order to merely meet the minimum requirements (Vailakis). The 1980s are a period in which

the contradictions and conflicts are not resolved, smoothed or suppressed, but emerge as a

central component of the political and social scene. There is political pluralism on one side

and failure of political understanding and prevalence of the two-party model on the other.

There is artistic experimentation and personal style but kitsch poetry as well, gyms and

frozen pizza, social benefits and homophobic ‘macho’ video tapes, communication

technologies and populism in the media (Papanikolaou). It is a time when nationalism also

flourishes, as is evident in the statement of the President of the Hellenic Republic from 19851990, Christos Sartzetakis, that ‘Greece is a nation with no siblings’3, which was met with

agreement and enthusiasm. The neo-conservatism that emerges once more during the 1980s,

touches Greece as well.

3

Therefore, departing from the commonly accepted and scientifically unshakable […] concept of the nation, the conclusion

which I publicly expressed during the Easter of 1985, that we, Greeks, are a nation with no siblings, indicates an indisputable

and tangible truth […] and indeed no nation on earth is related to us, we have siblings nowhere, unlike other nations and

peoples such as the Anglo-Saxons, the Romanic people, the Slavic people or the Arabs. Since all of them comprise not one

nation, but families of nations; with the exception of Jewish people, who are also a nation with no siblings (Sartzetakis,

1994)

http://www.sartzetakis.gr/points/thema1.html

�3

Hence when during such a period which is perceived as luminous, a director creates a

film that discusses ‘hell on earth’, confinement of the mind, mutilation of emotions and a life

of nightmare, he is treated as an unwanted pariah. However, he is now more topical and

timely than ever, since the people born during the 80s are currently experiencing the climax

of the ongoing fermentation described above. A fermentation always aided by ‘a European

Union that has, until now, reproduced and strengthened social and economic inequalities

throughout Europe and extended forms of intra-European racism through discriminatory

economic regulations and austerity measures’4. The ‘80s Greece’, through the indexing of

large or small social and political issues, ideological currents and artistic events of the period,

–implicitly yet clearly- gave prominence to all those parameters which foreshadowed with a

mathematical and almost incredible precision, what Greece is today (Vailakis). Consequently,

despite the unwelcoming reception of the film at the time, since it discusses various subjects

in highly controversial manners, Nikolaides’ vision proves insightful when analysed in a

crisis-ridden Greece of 2012. His words resonate like a warning from the past:

When I was shooting “Singapore Sling”, I was under the impression that I was

making a comedy with elements taken from Ancient Greek Tragedy . . . Later,

when some European and American critics characterized it as “one of the most

disturbing films of all times”, I started to feel that something was wrong with

me. Then, when British censors banned its release in England, I finally

realized that something is wrong with all of us.5

The contextualisation of the film was important for this paper to move forward, as it

illuminates Nikolaides’ motivation to create such an angry film. It was a statement against

4

Statement of Solidarity to the Greek Left by Chantal Mouffe, Costas Douzinas, Drucilla Cornell, Ernesto

Laclau, Etienne Balibar, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, Judith Butler, Jacqueline Rose, Jaen-Luc Nancy, Joanna

Bourke, Jacques Ranciere and Wendy Brown

http://greekleftreview.wordpress.com/2012/06/16/statement-by-balibar-brown-butler-spivak-on-greek-left/

5

From the director’s official website:

http://www.nikosnikolaidis.com/mainenglish/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=54&Itemid=15

�4

nationalism and homogenisation as well as his own sense of confinement stemming from the

feeling that people were trying to trap him inside a stereotype6. The contextualisation also

delineates the premise behind the selection of this particular work of art, as I belong to the

generation experiencing the aforementioned climax. Additionally, Singapore Sling proudly

stands as a masterpiece on its own and what is interesting, is that it attempts to represent the

formerly neglected female psychopath. ‘An excess that has rarely been seen before, a woman

whose violence, cunning and monstrosity are almost unparalleled in the women who form her

cinematic predecessors’ (Jermyn 251). However, this is not to proffer that this particular

representation of the contemporary woman’s conflicting roles offers a positive image that

should be sought out by a feminist appropriation project. In Barbara Creed’s words ‘I am not

arguing that simply because the monstrous-feminine is constructed as an active rather than

passive figure that this image is ‘feminist’ or ‘liberated’. The presence of the monstrousfeminine in the popular horror film speaks to us more about male fears than about female

desire or feminine subjectivity’ (“Monstrous” 7).

To return to the selection rationale, the film discusses decidedly controversial

subjects, through a stunning cinematography which attracted my attention and admiration.

Especially after encountering Julia Kristeva’s theory of abjection, the film -in my mind- was

transformed into an elaborate orchard of abjects and disgust, waiting for the grotesque fruits

to be harvested and brought to light. In chapter one, after reviewing the theory and history of

Disgust which has only taken off since 1990, this paper will explore why and how Singapore

Sling is disgusting. In chapter two, there will be a revision of the theory of Abjection as well

as its further appropriation and developments. The issue of film for example, has often been

overlooked by scholars who read Kristeva, and her own writing on film is also scarce as she

is mostly interested in the impact that a text has on the reader. Furthermore, in chapter two

6

It was stated in the “They’ve put us all in a supermarket” interview, 1990.

�5

there will be an attempt to correlate Disgust with Abjection and by some means enrich the

theory of the latter. This is because although Kristeva develops her own kind of theory of

Disgust in Powers of Horror, she avoids mentioning any others that have preceded it and

seems unaware of them, even though she is familiar with Freud’s. The theory of abjection

will be applied to film and will be used in order to explore in what ways Singapore Sling

could be considered abject(ive). The qualities which render the film a ‘ritual of defilement’

will be demonstrated in chapter three. Analysing the film based on the theory of abjection is

the primary goal of this paper. In forming a part of the first chapter, the CAD hypothesis will

be the main guiding line. The CAD triad hypothesis, was proposed by the cultural

anthropologist Richard A. Shweder and his colleagues, who discovered that ‘contempt, anger

and disgust are typically elicited, across cultures, by violations of three moral codes . . . The

proposed alignment links Contempt to Community (violation of communal codes), Anger to

Autonomy (individual rights violations), and Disgust to Divinity (violations of purity)’

(Rozin, Lowery, Imada, and Haidt 574). All three emotions play an important role in locating

disgust and abjection in and around the film, since in it, the ethics of Autonomy, Community

and Divinity, are constantly being attacked and undermined.

Singapore Sling7 is a manifold film consisting of horror, black-comedy and film-noir

among other genres. It is about a private detective (Panagiotis Thanassoulis) who arrives at a

mansion on a rainy night looking for a woman called Laura that has been missing for years

and is suspected to be already dead. This suspicion is inherent to the subtitle ‘A Man Who

Loved a Corpse’, which in its turn gave rise to reactions to narratives that were never part of

7

The film took its title after a cocktail whose name was found in the journal of the detective in the film as a

clue. After the Daughter in the film reads it out loud, she decides that they should name the man ‘Singapore

Sling’. The fact that the film itself is a cocktail of several genres, often leads reviewers to express the correlation

between the film and the actual cocktail.

�6

the plot8. The mansion is owned by a Mother (Michele Valley) and a Daughter (Meredyth

Harold) who open the film digging a grave for the chauffeur they have just murdered, under

pouring rain and the wet sounds of non-diegetic instruments that dampen one’s core. The

detective is watching them from a distance, unable to react, as he has been shot under

circumstances that are never disclosed. When the Mother and Daughter finish their ritual, the

viewers learn that they systematically kill their servants, burry them in the garden and plant

decorative plants on them, in a continuation of a tradition initiated by the Father of the family

who is now supposedly dead. His death is surrounded by uncertainty, since judging by the

Daughter’s point of view and the Mother’s occasional paranoid clues, he lives on in the form

of an un-dead mummy (Figure 1). Therefore when the detective rings their bell and the

Daughter finds him collapsed on the doorstep, the audience can easily presume that what is to

follow, will not be pleasant. Indeed, the psychopath duo drags him into their incestuous,

dangerous, gory sexual games that among other things involve murder, emetophilia9, hardcore bdsm10, rape and urolagnia11 (Figure set 1). And so the disgusting narrative begins.

Chapter One: Disgusting Singapore Sling

From Core to Moral Disgust

Charles Darwin described Disgust as ‘something offensive to the taste’ and classified it

among the most powerful and fundamental human emotions (250). It has got ‘an animal

8

Some people mention explicit acts of necrophilia in their reviews, or even cannibalism, which never actually

takes place, but the connotations were apparently strong enough to create a false impression.

9

A paraphilia involving individuals being sexually aroused by vomit.

10

BDSM stands for Bondage and Discipline, Sadism and Masochism.

11

A paraphilia involving individuals being sexually aroused by urine.

�7

precursor, called distaste, and it has a non-moral primordial form, called core disgust . . .

which is best described as a guardian of the mouth against potential contaminants (Haidt,

“The Moral Emotions” 575). Indeed, most evolution-psychologists agree that ‘disgust is

revulsion at the prospect of oral incorporation of an offensive object. . . The offensive objects

are contaminants’ (Rozin, Haidt, and Mccauley 757-758). What is served by Disgust, many

psychologists argue, is the denial of death; the repression of the knowledge and certainty of

death found only among humans. Indeed, a strong correlation has been found there between

disgust and the fear of death, during research on terror-management theory. Rozin et al have

also argued that disgust arises when people are confronted with their animal nature. Although

humans eat, excrete and reproduce like any other animal, culture defines the ‘decent’ way to

perform these actions and the ones who ignore the prescriptions are thought to be disgusting

and animal-like. What is more, blood and soft viscera seem to elicit disgust exactly because

they remind us of our connection to animals (Rozin, Haidt, and Mccauley 761). Disgust then

is the avoidance of contaminants. All animals that had the behavioural tendency to avoid

objects and situations that put them at risk of disease, gained an adaptive advantage.

Therefore, although the specifics of Disgust are shaped by culture, there is indeed a biological

pattern to our revulsions, rendering Disgust a part of human nature (Curtis and Biran “Natural

History” 660).

The regulation of bodily functions that protects humans from confronting their animal

nature is often inherent to ‘the moral codes of cultures and religions . . . where they appear to

function as guardians of the soul against pollution and degradation’ (Haidt, “The Moral

Emotions” 575). It thus seems, Rozin et al claim, that disgust ‘originated as a rejection

response to bad tastes, and then evolved into a much more abstract and ideational emotion. In

this evolution, the function of disgust shifted: A mechanism for avoiding harm to the body

became a mechanism for avoiding harm to the soul’. Although elicitors of Disgust have

�8

become widely diverse, what they have in common is how ‘decent’ people keep them all at

bay; a kind of behaviour that turns Disgust into a moral emotion and a powerful form of

negative socialisation. (Rozin, Haidt, and Mccauley 771). Many philosophers have attempted

to define morality more closely and for ‘Westerners, at least, sociomoral disgust can be

described most succinctly as the guardian of the lower boundary of the category of humanity.

People who “de-grade” themselves, or who in extreme cases blur the boundary between

humanity and animality, elicit disgust in others’ (Haidt, “The Moral Emotions” 857). What

began as an avoidance of actual parasites evolved to serve an aversion to social ones, which

consequently brought about their punishment and exclusion based on a set of virtues that a

culture considers essential.

The CAD Hypothesis Organisation

To expand the CAD Hypothesis, let us revisit the premise which holds that contempt, anger

and disgust are elicited across cultures through the violations of the following moral codes:

Community, Autonomy and Divinity respectively12. The ethics of Autonomy are attacked when

individuals are physically or psychologically abused, or when fairness, freedom of choice,

equality and human rights are harmed. When I first encountered the hypothesis, what

appeared as fully possible was that it is not only anger that is elicited when the ethics of

Autonomy are undermined. I sought correlations between anger and disgust, which proved to

be a standing postulation. Indeed, Rozin, Haidt, and Mccauley claimed that ‘studies which

ask people to recall times they were disgusted, elicit stories that often focus on moral

violations, and that involve high levels of anger as well’ (762). Furthermore, Catherine

Cottrell and Steven Neuberg maintain that both anger and disgust are ‘elicited when people

encounter a physical or moral contaminant, suggesting that intergroup disgust [and anger are]

12

The initial letters of each emotion and its respective moral code are conveniently the same, which led to the

name of the hypothesis.

�9

likely to occur when an out-group promotes values and ideals that oppose those of the ingroup’ (773). Another means by which anger and Disgust are related, is through the

connection of their moral codes. As Lene Jensen claims, ‘Christian concepts have become

redefined to an extent where they only vaguely resemble the ideals of traditional Christianity.

Instead, people bestow “something like a sacred status” on individual autonomy’ (72) which

automatically links autonomy to divinity.

Similarly, upon reading that the ethics of Community focus on the interests of

collective entities such as family, country, society, traditions, and that any harm to social

order and harmony elicits contempt, I searched for correlations between contempt and

disgust. William Ian Miller in his Anatomy of Disgust, called ‘contempt a close cousin of

disgust, which works with disgust to maintain social hierarchy and political order’ (Haidt,

“The Moral Emotions” 575). In his own words:

Disgust surely has some close affinities with other sentiments. In routine

speech we use contempt, loathing, hatred, horror, even fear, to express

sentiments that we also could and do express by images of revulsion or disgust

. . . There is no doubt that the most intense forms of contempt overlap with

disgust. Darwin called this extreme contempt “loathing contempt”. (24-32)

Lastly, the ethics of Divinity are founded on Divinity/purity violations, which elicit Disgust

when people commit ‘sin’ or do not protect the soul or the world ‘from degradation and

spiritual defilement’. When they do not respect their obligations to God’s authority, the

scriptural authority, or Nature’s Law, people are considered disgusting. The CAD hypothesis

is very useful when explaining the moral differences across social classes and cultures and it

also helps in ‘understanding such things as the culture wars that currently put liberals and

progressivists (whose morality is limited to the ethics of autonomy) against conservatives and

�10

orthodox (with a broader moral domain, including community and divinity) (Haidt, “The

Moral Emotions” 576).

How and Why Singapore Sling is Disgusting13

In Singapore Sling, one cannot miss the extravagance of gory imagery and challenging

narrative. The incestuous, murderous, bourgeois Mother-Daughter duo constantly undermines

all three moral codes discussed above. They frequently bring the audience to a state of utter

disgust pervaded with fear and ‘we have a name for fear-imbued disgust: horror’ (Miller 26).

Indeed, it is a horror film among other things, which pays no respect to any constructed moral

codes. But how exactly are the ethics of Autonomy undermined in it, for example? To begin

with, the women of the house rape, torture and murder their servants or anyone who enters

13

There are numerous reviews on the film and most of them seem to revolve around two prevailing concepts; that of

uniqueness and that of Disgust. Here are a few examples in English (although those two main concepts are also found in

German, Spanish and Greek reviews):

Simultaneously hypnotic and repulsive, "Singapore Sling" is an absolutely one-of-a-kind film-watching experience’ (Kate

Tenebrous http://tenebrouskate.blogspot.co.uk/2010/11/singapore-sling-1990.html).

This is one of the most unique films I've ever seen, and I'll probably remember scenes from it till the day I die . . . A mix of

utter revulsion and sensuous, wayward eroticism (http://www.myduckisdead.com/2010/06/singapore-sling-1990.html).

“Singapore Sling” is one of the most brutal, sick, unpleasant, and stomach-churning films to be made. That it is artfully

shot, well-acted, philosophically poignant, and mannered only seems to add to the discomfort levels. There are no films like

this one (Witney Seibold https://witneyman.wordpress.com/2009/10/07/singapore-sling-1990/).

While the weird sex is often repulsive and sometimes hard to watch, I can’t say some of it wasn’t damn well

executed. Singapore Sling is a cheeky and nasty little film I found unique and thoroughly mesmerizing

(http://goregirl.wordpress.com/2011/03/05/singapore-sling-1990-the-dungeon-review/).

�11

their mansion for that matter. This symbolically connotes the massive lewdness that takes

place on the bodies of servants all around the world, or even on certain ideas. It undoubtedly

attests to the lack of any concept of human rights, fairness, individuality or equality and

therefore is a downright confirmation of the ethics of Autonomy being violated.

Consequently, the women’s actions lead to emotions of anger and Disgust. The ethics of

Community suffer an analogous affliction, since there is no respect to any authority, political

or divine, and by murdering people they act against the preservation of the community.

Moreover, at the family table food and vomit play an equal role, since the two women eat to

the point of vomiting without being affected (Figure set 2). The Mother forbids smoking

inside the house when apparently murder and rape are encouraged, and she arrogantly

proclaims: ‘Honesty is the first virtue I demand in this house . . . you must be a virgin to be

accepted here’. Therefore by engaging in a murderous, incestuous relationship and by

ridiculing traditional family values, Nikolaides has them corrode the constructed ideals and

traditions of the Family and the social order and harmony. In fact as Anna Powell suggests,

horror elements are commonly used devices in order to threaten this symbolic construct; this

abstract ideal of the nuclear family and its validity (137). In addition, regarding the Mother

and the Daughter being hard-core fetishists, Louise Kaplan when elaborating on fetishism

suggests that

the first principle of the fetishism strategy defines fetishism as a mental

strategy that enables a human being to transform something or someone with

its own enigmatic energy and immaterial essence into something or someone

whose form of being makes them controllable. (5)

Kaplan also noticed that Karl Marx’s theory of surplus labour tightly resonates with that

principle:

�12

a human being transforms other human beings, with their own enigmatic

energies and vitalities, into things that are material and tangibly real. Through

the process of providing surplus labor value for the capitalist, the worker is

transmogrified into a commodity. (qtd in 6)

This juxtaposition effectively reflects the relationship between the bourgeois and the fetishist.

In the case of Singapore Sling, those two coincide in the characters of the Mother and the

Daughter, who act as enemies of both Autonomy and Community. By abusing each other and

the man, they undermine Autonomy and on a symbolic level, they also attack the culturally

structured ideals of Community. Through both extreme sexual acts and exploiting and killing

their servants, they personify two of society’s threats against Human Rights: Sexual abuse

and Capitalism.

Finally, the ethics of Divinity which are directly connected to Disgust are degraded to

such extent that one can only assume that Nikolaides enjoyed every moment of degrading

religion. Before proceeding to providing examples which illustrate this kind of transgression,

here follows Daniel Kelly’s elaboration on the domain of divinity:

Purity norms, which are central to the moral codes of many traditional or

religious cultures, are said to regulate the domain of divinity. In such cultures,

transgressors of purity norms are thought to be defiling their selves or very

souls, either by showing disrespect toward God or the gods, or by violating the

sacred, divine order. Purity norms are present but more peripheral in the moral

codes of secular cultures, where they are often justified differently, usually by

appeal to the so-called natural order. Consequently, transgressions of purity

norms in secular societies are often thought of as unnatural acts or crimes

�13

against nature . . . Purity norms also address the specifics of which sexual

activities are permissible and what is forbidden, deviant, or “dirty”. (121)

In Singapore Sling, there is an on-going role-playing game between the Mother and the

Daughter, in which the Mother plays the Father and the Daughter plays Laura when she first

arrives at the mansion14. The game always begins with Laura introducing herself and the

‘Father’ asking her: ‘How long has it been since you last confessed?’ before ‘he’ proceeds to

force her to perform fellatio on a fake penis. The purity norms of the Western culture have

always condemned sexually deviant activities, which certainly abound in the film, in a wide

inventory of perversions15. However, deviant sex is not the only means by which Nikolaides

playfully turns his back to purity norms. He also has the women burry their chauffeur’s body

without giving him a proper burial, but they throw a ceremonial wreath at the body in a

joking manner nonetheless. Incest is supposedly against Nature’s Law and therefore a crime

and finally, when the Daughter is shown having sex with the mummy-Father, they exchange

the following words:

Daughter: How cruel, Father; how cruel… Heaven will punish us.

Father: My little darling, heaven is the last thing that concerns us in this world.

Religion has now been blatantly mocked and this supposedly accounts for explicit

expressions of Disgust since it is our response to our demotion from our supposed position of

godlike stature (McGinn 74). It is interesting how core and moral disgust converge within the

phraseology employed by religion:

The good is “pure” and “clean”; evil is “filthy” and “foul”. We must be “pure

in heart” and not succumb to “moral corruption”. The body is our “temple”

and must be kept “undefiled”. Our soul must remain “spotless”. We must not

let ourselves be “contaminated” by “rotten” doctrines. (Colin Mcginn 218)

14

Laura is the young secretary that the detective has been looking for

Paedophilia (the Father took the Daughter’s virginity when she was eleven years old), urolagnia, emetophilia,

torture, rape and hints of necrophilia.

15

�14

Additionally, ‘the idea of “want” tied to sin as debt and iniquity is therefore coupled with that

of an overflowing, a profusion, even an unquenchable desire, which are pejoratively branded

with words like lust or greed’ (Kristeva “Powers” 123). Therefore lust and greed seem to be

directly related to violations of divinity. The Mother and the Daughter being sexually

insatiable and eating until they regurgitate, embody both lust and greed to an exaggerated

extent, and subsequently to a disgusting extent.

Naturally, Singapore Sling was not perceived as disgusting by the audience based

solely on its violation of moral codes. Curtis and Biran, after reviewing and matching

research conducted by several evolutionary psychologists, came to the conclusion that there

are five broad categories of objects or events that elicit disgust: Bodily excretions and body

parts, certain categories of ‘other people’, decay and spoiled food, particular living creatures,

and violations of morality or social norms (20-21). The last category has already been

explored but the film covers the first three as well. ‘Bodily excretions and body parts’ abound

in Singapore Sling for example, since the women urinate on the man while raping him, they

vomit on him and on the family table, and they disembowel their servants after they kill them.

Colin McGinn, when commenting on internal organs and their impact, says:

We can stand the thought of these soggy monstrosities when they are

ensconced safely inside the body’s fragile envelope, but once they are brought

out into the open— in surgery or trauma—disgust beats its drum loud. Few

things are more revolting to us than disembowelment, when the intestines are

exposed and ripped from the still-living body; but the mere sight of a pulsating

bloody heart is enough to turn most people’s stomachs. (24)

Interestingly enough, a pulsating bloody heart is exactly what features in the film at some

point surrounded by other organs (See Figure set 3), leaving the audience with a turned

stomach. What is meant by ‘other people’ is ‘in poor health, of lower social status,

�15

contaminated by contact with a disgusting substance, or immoral in their behavior’ (Curtis

and Biran 21). Judging by the contemporary standards of what is considered immoral or

‘contaminated’, the incestuous lesbian couple could be argued to belong to the category of

‘other people’ and qualify as elicitors of disgust. Additionally, since they come in contact

with food of ambiguous consistency that they disgorge on their own table, they cover the

category of ‘spoiled food’ along with being contaminated by contacting a disgusting

substance.

‘Other people’ supposedly includes those of ‘lower social status’ but the Mother and

Daughter clearly belong to the bourgeoisie, as indicated by their house, their clothes and the

way that Mother speaks. The house is heavily decorated in baroque style, with elaborate

patterns and various fabrics around; mirrors with intricate framing, layers of satin and lace,

numerous pillows and extravagant furniture (Figure set 4). Their flowing gowns remind of

post-Victorian, rich suffragettes and the Mother speaks first in French and then translates

herself into English, clearly embodying the degrading bourgeois in a satiric manner.

Although filth is usually connected to poverty, the ones who are represented as filthy and sick

are the wealthy family. Nikolaides’ choice to put the bourgeoisie in a disgusting position is

all but coincidental, since he would often express his contempt towards the idiotic morals and

habits of the declining aristocracy. When the Mother and the Daughter are depicted by

torturing, raping and murdering the ones below them, it is a direct critique on how ‘lowness’

is considered a threat by the high, who are aware that they owe their position to the contrast

provided by the low. Moreover, the connection between filth/cleanliness and the bourgeoisie

has often been commented on: ‘Frenchmen from the 18th century onward began to manifest

intense disgust at a new range of objects, they began using the emotion to motivate a variety

of new sanitary and cosmetic behaviors and to justify new social distinctions between the

washed and the unwashed’ (Stearns 24). Miller adds: [The Christians’] disgust made

�16

vulgarity a moral issue, and a Marxist might wish to claim that such philosophies were

merely supporting a new class-based social order by elevating bourgeois social tastes into

moral demands (193).

The Mother and Daughter’s bodies emit fluids indiscreetly and always seem on the

verge of erupting, manifestly defying and transgressing the censures of bourgeois norms,

morals and manners. They seem to have leapt out of Rabelais, since the urine, vomit,

masturbation with a kiwi fruit and disembowelment, ‘transform the erotic into the emetic’

(Kipnis, 225). ‘Control over the body has long been associated with the bourgeois political

project, with both the ability and the right to control and dominate others’ (Kipnis 226) and

therefore the representation of such uncontrollable bodies raises particular political

discussions. As Stallybrass and White put it, the bourgeois subject has ‘continuously defined

and redefined itself through the exclusion of what it marked out as low–as dirty, repulsive,

noisy, contaminating . . . [the] very act of exclusion was constitutive of its identity’ (191). ‘So

disgust has a long and complicated history, the context within which should be placed the

increasingly strong tendency of the bourgeois to want to remove the distasteful from the sight

of society’ (Kipnis 227). Conclusively, through the depiction of the uncontrollable, disgusting

–albeit aristocratic- body and its atrocities, dominant Ideology with its exclusionary devices,

becomes the object of severe criticism within Singapore Sling. The fact that the film has been

rejected or banned, also reflects the impulse to remove any ‘disgusting’ elements that are

perceived as ‘contaminants’ that threaten the body of Ideology.

Chapter two: Abject(ive) Singapore Sling

The Theory and origins of Abjection

�17

The term ‘abjection’ originates from the Latin abjectiō which means to ‘cast away’, ‘throw

down’, ‘reject’. It was adopted by Julia Kristeva in the 1980s to mean among other things

‘the jettisoned object, [that] is radically excluded and draws me toward the place where

meaning collapses’ (“Powers” 2). Before a further reviewing of the term begins, it is

important to highlight its incipient relation to Disgust, since ‘Disgust is manifested as a

distancing from some object, event, or situation, and can be characterized as a rejection’

(Rozin, Haidt, and Mccauley 757-758). Therefore both Abjection and Disgust derive from the

motivation to expel. Mary Douglas in the 1960s was one of the first to write on ‘dirt’

rejection. She claimed that ‘if we can abstract pathogenicity and hygiene from our notion of

dirt, we are left with the old definition of dirt as matter out of place’ (36). Dirt according to

her is not an isolated event, but inherent to systems and their order, as it is their by-product.

When ordering and classification of matter implies rejecting elements that are not

appropriate, there will be dirt (36). In her theory of pollution, Douglas locates social structure

at the centre, as the base from which Disgust develops. This entails that Disgust and what is

disgusting are socially delineated. The idea that Disgust seems to require enculturation has

indeed proven to be accurate by scientists who have worked on Disgust since Douglas’s

writing. However, Kristeva uses Douglas and then departs from her. With her theory of

Abjection, she attempts to facilitate the understanding of our fear of being disgusting and of

the experience of Disgust. She makes use of Douglas’ anthropological work to ‘contend that

abjection also plays out on the social level body’ (Farrar 21), since the body, Douglas

suggests, ‘is a model which can stand for any bounded system. Its boundaries can represent

any boundaries which are threatened or precarious’ (6). It is the body’s ideas of pollution and

purity through which the body gives itself a fragile status, since it is those ideas that ‘codify

ambiguous boundaries and reify indeterminate identities in to manageable differences’

(Farrar 21). In Douglas’ words:

�18

Ideas about separating, purifying, demarcating and punishing transgressions

have as their main function to impose system on an inherently untidy

experience. It is only by exaggerating the difference between within and

without, above and below, male and female, with and against, that a

semblance of order is created. (4)

Consequently, as it happens with Disgust that is culturally circumscribed, what is considered

acceptable, clean, ‘good’ and civilised in a culture, is separated from what is regarded as

abject, dirty, evil and uncivilised, through the means of the Law, morals, taboos or even

space. Our entire social system, through its prescriptions of hygiene and propriety, is

structured around confining the abject, keeping it ‘away from the space of the self’ (Farrar

21).

According to Kristeva, there is a pre-symbolic stage in our lives, defined by intense

feelings of horror and repugnance when we approach certain situations, people or objects that

are considered abject and are inherently undesired. This implies that the connotations

surrounding the abject are decidedly negative, since it is what an individual abjects/rejects

due to its horrific qualities. The corpse for example, as stated by Kristeva, ‘is the utmost of

abjection. It is death infecting life. It is something rejected from which one does not part,

from which one does not protect oneself as from an object’ (“Powers” 4). However, this kind

of rejection according to Kristeva is what forms the Ego, since the procedure of abjection is

translated into the Ego’s strife for autonomy. More specifically, our mother expels us and we

have to expel our mother at some point in our lives, in order to enter language and the

symbolic as autonomous individuals. This is ‘the first intimation of the interdiction against

incest. . .Our feeling of revulsion when we come into contact with the objects that we find

disgusting (except under specially defined circumstances), keeps taboos in place’ (Lechte

10). The abject is ‘both that by which the child is separated from the mother and the mother

�19

herself’ (Markotic 828). In order for the child to cultivate a sense of self, they have to learn

about what is other than the self; to learn about the abject and what is impure. ‘To become

social, the self has to expunge certain elements that society deems impure: excrement,

menstrual blood, urine, semen . . . vomit, masturbation, incest and so on’, even though these

elements Kristeva maintains, can never be fully eradicated; they haunt and threat the subject’s

identity (McClintock 71). However, ‘the abject is not only the product of subjection . . . but

the very process through which the individual self achieves the status of becoming what

Sigmund Freud has defined as ego and is at once repulsive and attractive’ (Wilkie-Stibbs

319). In short, ‘Kristeva’s abjection offers the opportunity to theorize an aesthetics of disgust

founded upon ambiguity’ (Meagher 30).

Abjection and Disgust: The Common Ground

According to Jonathan Haidt, even though the elicitors of Disgust developed from core to

sociomoral Disgust, the reactions to it have not been subjected to much change. All forms of

Disgust embody an impulse to ‘avoid, expel, or otherwise break off contact with the

offending entity, often coupled to a motivation to wash, purify, or otherwise remove residues

of any physical contact that was made with the entity’ (“The Moral Emotions” 857). The

theory of Disgust, begins with Darwin who related it to food rejection16 and Rozin, Haidt and

McCauley developed it to mean a ‘phylogenetic residue of a voluntary vomiting system. . .

Disgust is a mechanism for avoiding harm to the body’ (638-650). Vomiting is inherent to

Abjection as well, according to Kristeva: ‘Loathing an item of food, a piece of filth, waste, or

dung. The spasms and vomiting that protect me . . . Loathing is perhaps the most elementary

Disgust literally means ‘distaste’ from des- “opposite of” + gouster “taste”

http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=disgust

16

�20

and archaic form of abjection’ (“Powers” 2). Vomiting as a means of protecting the body,

clearly brings Disgust and Abjection together. Abjection is

an extremely strong feeling which is at once somatic and symbolic, and which

is above all a revolt of the person against an external menace from which one

wants to keep oneself at a distance, but of which one has the impression that it

is not only an external menace but that it may menace us from the inside.

(“Powers” 135)

The ambiguity between the external and the internal menace, is an issue raised within the

discourse of Disgust as well, since the latter not only protects us from contaminants (external

menace), but also keeps us at a distance from our animalist side (internal menace), as

mentioned in chapter one. Interestingly enough, the abject confronts us, Kristeva upholds,

‘with those fragile states where man strays on the territories of animal’ (“Powers 12

Kristeva’s italics).

Another common element is the prototypical elicitors of Abjection and Disgust.

Several evolutionary psychologists suggest that the stimuli which trigger the latter ‘include

waste products of the human body, poor hygiene, violations of the body envelope, and death.

Disgust appears to have a cultural domain and can be elicited by immorality and violations of

social rules’ (Miller; Rozin et al. in Curtis 18). Elicitors of Abjection according to Kristeva

are ‘vomit and shit, decay and death. Such images tend toward a representation of the body

turned inside out, of the subject literally abjected, thrown out’ (Foster 112). When it comes to

the cultural domain, crime is also considered abjective since ‘it draws attention to the fragility

of the law’ (Kristeva “Powers” 4). Violations of social rules are not explicitly stated as

abjective by Kristeva, but Judith Butler has taken the theory of abjection further, to critisise

Ideology and how it relieves its fear of disintegration by stigmatising certain groups or

practices as ‘abject’. In her own words:

�21

this exclusionary matrix by which subjects are formed requires the

simultaneous production of a domain of abject beings, those who are not yet

“subjects”, but who form the constitutive outside to the domain of the subject

[…] the subject is constituted through the force of exclusion and abjection,

one which produces a constitutive outside of the subject, an abjected outside,

which is, after all, “inside” the subject as its own founding repudiation. (3)

Tina Chanter seems to concur: ‘I do not think [Abjection’s] scope should be restricted to a

description of the infant’s rejection of the mother. On the contrary, I see abjection as

inherently mobile, and as descriptive of a mechanism by which various others are stipulated

as excluded’ (“Revolt” 158). In the sphere of the socially constructed rules of

heteronormativity for example, homosexuality becomes abject(ed) and it resonates with how

it is often considered as contagious and threatening ‘filth’ or disgusting. Disgust, similarly to

Abjection, ‘has an unfortunate habit of bringing condemnation down on people for what they

are, not just for what they do’ (Haidt “The Moral Emotions” 858).

Finally, Abjection and Disgust share the common element of simultaneous repulsion

and fascination. The chora17 must be abjected when the child enters the symbolic, or it will

keep threatening the borders of identity that have just formed. However, the abject also

fascinates to an overwhelming extent, because regardless of having expelled the maternal

chora, the self longs for a reunion with it. ‘One thus understands why so many victims of the

abject are its fascinated victims -if not its submissive and willing ones’ (Kristeva “Powers”

9). Similarly, there is the ‘macabre allure of disgusting objects; they invite our attention and

seek to keep it. Simultaneously, the object draws the senses in, magnetically, and also repels

17

Chora: The earliest stage in your psychosexual development (0-6 months), according to Julia Kristeva. In this

pre-lingual stage of development, you were dominated by a chaotic mix of perceptions, feelings, and needs. You

did not distinguish your own self from that of your mother or even the world around you. Rather, you spent your

time taking into yourself everything that you experienced as pleasurable without any acknowledgment of

boundaries. This is the stage, then, when you were closest to the pure materiality of existence, or what Lacan

terms "the Real." At this stage, you were, according to Kristeva, purely dominated by your drives (both life

drives and the death drives). http://www.cla.purdue.edu/english/theory/psychoanalysis/psychterms.html

�22

them’ (McGinn 46). Even the dead body which is the utmost of Abjection and Disgust, exerts

a certain fascination:

People find themselves mesmerized by the dead body, drawn to it against their

will, even as their stomach turns queasy . . . Disgust is not boring. It has a kind

of negative glamour. And the human psyche is drawn to the interesting and

exceptional— the charged object, with its magical potency. . . We gaze

between our fingers, stimulated and appalled simultaneously. . . Necrophilia,

coprophilia, and fetishism of various stripes are cases in which aversion is

eclipsed by attraction. The disgusting becomes wholly or mainly attractive,

with the aversive element in retreat or silenced we are all fascinated by what

disturbs us most, by our own responsiveness to the gross and repugnant.

(McGinn 48-49)

Conclusively, Kristeva essentially developed her own theory of Disgust, since for her, ‘all

present and objective experiences of disgust. . .can only have a phobic effect, because they

recall that abject (because originally repressed) maternal body which lies behind all

difference of subject and object’ (Menninghaus 374).

Filmic Representationality of Abjection

The abject is considered to be ‘unspeakable’ because it is outside the discourse domain and

practically invisible. Therefore representing it, poses a serious challenge for any artist,

especially since it always orbits the ‘taboo’. As a consequence, the abject ‘has to be

stylistically downgraded’ (Berressem 31) and is usually employed by artists who intend to

‘provoke horror and thus regenerate an affective relation to art in place of a relation that had

become too cerebral’ (Lechte 11). Indeed, it is horror films which illustrate many

characteristics that are inherent to the abject:

�23

Firstly, the idea that the abject is both repellent and fascinating. Secondly, the

notion that the abject is always present; although horror films usually expel the

abject by the ending, its existence has nevertheless been acknowledged and

may indeed return. Thirdly, there is the idea of ritual, that the formulaic nature

of horror exists as a tolerable means of exploring, and finally rejecting, the

abject. Finally, there is the link between the feminine and the abject, both as

configurations in opposition to the paternal symbolic, and through woman's

unclean functions of menstruation and childbirth. (Jermyn 254 my italics)

For Kristeva, what causes abjection is what ‘disturbs identity, system, order. What

does not respect borders, positions, rules’ (“Powers” 4). Horror therefore emerges when the

boundaries that maintain the social order are threatened. Such boundaries according to

Katherine Goodnow and Barbara Creed, are the ones between the living and the dead, human

and nonhuman, clean and unclean, love and destruction, male and female. Subsequently,

when those unstable borders and areas of ambiguity are detected within a film, they can serve

as a steeping stone for locating the abject (Goodnow 28-29). Especially when there are

several of them combined together, the horror is intensified. Creed places emphasis on the

concept of the border, as she considers it to be central to the composition of the ‘monstrous’

in the genre of horror film and ‘[a]lthough the specific nature of the border changes from film

to film, the function of the monstrous remains the same - to bring about an encounter between

the symbolic order and that which threatens its stability (“Monstrous” 10-11). Despite

reminders of borders and their fragility being certainly powerful sources of horror, by

themselves alone, they do not provide a sufficient account of the abject. In Kristeva's

analysis, the abject covers as well all images of pollution (Goodnow 32). Naturally, the

horror film does not fail to employ imagery that directs to the abject, as in the genre, there is

a persistent obsession with the depiction of how disgusting the physicality of the body can be,

�24

with all its excrements, discharges and obviously its final stage -the corpse. Creed confirms

and expands:

[M]odern horror texts are grounded in ancient religious and historical notions

of abjections - particularly in relation to the following religious ‘abominations’: sexual immorality and perversion; corporeal alteration, decay and

death; human sacrifice; murder; the corpse; bodily wastes; the feminine body

and incest. These forms of abjection are also central to the construction of the

monstrous in the modern horror film. . . The horror film abounds in images of

abjection, foremost of which is the corpse, whole and mutilated, followed by

an array of bodily wastes such as blood, vomit, saliva, sweat, tears and

putrefying flesh. (“Horror” Screen 46-48)

Conclusively, in attempting to locate abjection within a film, there are certain indicators that

ought to be taken into account: volatile borders and zones of equivocation, images of

pollution, the relation of the abject to the maternal and the feminine, the eternal return of the

abject, and other elicitors such as the hypocrite criminal among others.

How is Singapore Sling abject(ive)?

The reason for the suffix –ive being within parenthesis, lies in the qualities of the film which

render it both Abjective and abject. Abjective in the sense of attempting to represent the

abject, and abject because the film itself possesses characteristics that classify it as a byproduct of rejection. Regarding the abject’s representation, as mentioned above, there are

several pointers.

1. Unstable Borders and Areas of Ambiguity; the Composite

�25

In order for an individual to develop psychically, the borders between oneself as subject and

others as objects, need to be clearly defined and established (Meagher 31). The abject ‘draws

[us] toward the place where meaning collapses’ (Kristeva “Powers” 62). This is the reason

why Goodnow and Creed argue that horror and the abject emerge when those boundaries of

identity and the social order are being threatened, under the menace of the collapse of

meaning and the eradication of the self. Furthermore, Kristeva explains that what causes

abjection is ‘[t]he in-between, the ambiguous, the composite . . . when death, which, in any

case, kills me, interferes with what, in my living universe, is supposed to save me from death’

(“Powers” 4 my italics). When for example the clean and the dirty are placed together, or

when innocence and violence appear side by side, the composite appears (Goodnow 37 my

italics). Let us then explore those fluid boundaries and the composite, within the scope of

Singapore Sling.

1.a Boundaries between living and dead

The oscillation between life and death in the film, begins in the first scene with what seems to

be the dead body of the chauffeur who albeit cut open, vainly manages to raise his arm for a

last plead for salvation (Figure 2). The moment when the hand of the disembowelled body

unexpectedly extends begging for help, presents a strong image of a transgressed boundary.

An additional ambiguous border is the Father of the family himself, who appears to be an

active mummy. He thus becomes the archetype of the un-dead, the living corpse, condemned

to eternally vacillate between the living and the dead and to remind us of the fragility of the

borders. When the detective is tortured and raped by the Mother and the Daughter at the

beginning and he is being deprived of food and water, he personifies the ‘corporeal

expression of abjection through a body [that] is itself precariously balanced between life and

death’ (Wilkie-Stibbs 321).

�26

1.b Boundaries between Love and Destruction

The whole relationship between the Mother and the Daughter, seems to be dangerously

balancing between love and destruction, since there is supposed to exist a family bond

between them as well as a sexual relationship. However, there is so much violence and

torture involved, that destruction always seems to await somewhere near. Indeed, the climax

of the destructive Mother-Daughter relationship is reached by the Mother’s murder by her

child. An interesting depiction of (making) love tied with lurking destruction, is a smooth,

choreographed sex sequence among the three characters, in which a gun is discretely

changing hands from one character to the other while each one is trying to hide it (Figure set

5). Love also seems to be the motivation behind the Daughter’s advances towards the man, as

she has convinced herself that she is the beloved Laura whom the detective has been looking

for. But this does not stop her from inflicting pain on him or shoot him, which indicates

destruction interfering with love and blurring the boundaries.

1.c Boundaries between Clean and Unclean

It has been demonstrated so far, that ‘cleanliness’ has powerful denotations and connotations.

It can be used both metaphorically and literally and still convey its importance. As far as the

film and the literal meaning of cleanliness are considered, the most striking example of the

boundaries between the clean and the unclean being threatened, is the family table. The first

time it appears on screen, it gives the impression of a spotless, affluent space of food

consumption, but when the women sit down to eat, their eating ritual transforms it into a

locus of utter disgust and filthiness. Another example is the bathtub in which the decrepit

man is placed to be cleaned, which reflects ‘[t]he desire within modernity to transcend

corporeality, [which] inevitably results in the condition of abjection’ (Mohanram Par. 35).

Radhika Mohanram goes on to suggest that

�27

the Victorian insistence on the trope of hygiene and the colonisation of water

that enables [that] trope, is precisely to ward off the threat of abjection that

besets bourgeois subjectivity and its desire to transcend corporeality. The flow

of water and its cleansing properties that can deodorize and disembody can

thus control abjection and disperse its threats. Water is the natural ally of

strong subjectivity within modernity and postmodernity. (Par. 36)

This leads us back to the bourgeoisie that shaped the distinction between the washed and the

unwashed, aiming to transform it into a device of social division and discrimination. The

figurative meaning of cleanliness is yet again represented as undermined by the supposedly

clean bourgeois family. They are engaging in ‘dirty’ if not the dirtiest activities. The

Daughter’s ‘purity’ is defiled when she is eleven years old and her Father takes her virginity,

and generally what is socially constructed and considered as ‘dirtiness’, takes place inside the

mansion. Water as an element is considered to have cleansing qualities in general, but in

Singapore Sling, it surrounds death. They wash the man in a bathtub but he almost gets

drowned, the burials are always performed under rain, there is a sex scene where the

Daughter is being choked by water and finally, the Mother is killed inside a bathtub filled

with water18 (Figure set 6).

1.d The boundaries between Male and Female

Alison Goeller, among several other theorists of gender, has concluded that ‘the inability to

detect the gender of the body is [a] source of anxiety since gender is one of the major

signifiers of human identity (287). Indeed, ‘for Kristeva the ultimate excitement and the

ultimate anxiety are caused by not knowing how to classify someone or something’ (Oliver

5). Therefore when the borders between male and female ‘contained in the social and

18

The scene of the Mother being murdered in the bathtub by the lovers that have conspired is remarkable

because it opens a dialogue with the circle of the Mycenae. It evokes (an adapted) version of the murder scene

where Clytemnestra is murdered by Orestis and Electra, directly referring to the ancient drama and the cursed

House of Atreides. (Tsakoniatis et al 140)

�28

symbolic order’ collapse, the imminent instability becomes a source of horror and abjection

(Goodnow 40). Additionally, horror can reside in the reminders of the differences or the

similarities between males and females. For Kristeva the menstrual blood for example, is

considered horrific partly due to its differentiating qualities. As far as the differences are

concerned, their loss ‘occurs by way of the male creature being assigned a passive state

normally assigned to women. He is completely under her control, ‘feminized’ and with his

life and death at the mercy of her vacillating mood’ (Goodnow 42). The detective in

Singapore Sling arrives at the mansion with a bullet-shot in his shoulder (Figure 3). This

connotes that he is already bleeding and helpless in an inadvertently passive, malleable state

which is made worse in the hands of the Mother and the Daughter. Nikolaides places him in a

vulnerable position, constantly threatened and with his life depending on the women’s will or

mood. The detective is thus bleeding and at their mercy, ‘feminised’ by them to the point

where he replaces the Mother after her death and is now wearing her clothes and make-up

(see fig 4).

Deborah Jermyn claims that ‘[c]lothes, makeup, hairstyles and accessories, all take on

huge significance in film, and within the female gothic as a whole, as the stuff that women

use to construct their identities (264-265). Although the detective is not technically a woman,

his feminisation to the point of cross-dressing could be argued to symbolise Irigaray’s

suggestion that femininity is a performance that women give in certain social contexts as a

masquerade which is necessary for their ‘survival’ (76). ‘For Irigaray, women learn to mimic

femininity as a social mask’ (McClintock 62) and this masquerade discusses the problematic

of femininity as a social, artificial construction. The blending of male and female in

Singapore Sling could therefore be considered as potential elicitor of horror. Another instance

of the masquerading is the Daughter pretending to be Laura, a harmless secretary. But her

failure to actually become Laura by copying her,

�29

illustrates the futility of this notion of the construction of femininity. As the

female foil, [the Daughter] still represents the unacceptable face of femininity

which must be defeated. As the abject she must be expelled, destroyed for her

symbolic castration of the men she attacks, her violence and, particularly, her

sexual excess. [She] represents deviant female sexuality . . . for her . . . lesbian

desire and for masturbating. While the film must ultimately show her as

unbalanced, and she must be punished for this, it also exhibits fascination and

abject pleasure in her sexuality. (Powell 265)

The Mother and Daughter’s lesbian desire is an area of representation in which the

boundaries between female and male collapse, due to the long history of the lesbian woman

being ascribed male qualities or even being identified with men. Freud played a major part in

this categorisation, by maintaining that ‘[o]nly as a man can a female homosexual desire a

woman who reminds her of a man’ (qtd. in Irigaray 194). In his account of fetishism, after

discovering that lesbian sex extensively employs fetishist activities, he even goes on to equate

the lesbian with the man, in order to support his assertion that it is only men who fetishise

(“Fetishism” 190-205). Subsequently, ‘[i]f women are provisionally admitted into fetishism,

it is not as bearers of our own insistent desires, but on strictly male terms, as mimics and

masqueraders of male desire’ (McClintock 62). As a consequence, the Mother and the

Daughter who exhibit both fetishist and lesbian desire, cause those fabricated boundaries

between male and female to collapse, paving the path to Abjection.

Additionally, the detective remains silent throughout the film, with the director giving

the audience an insight into the man’s thoughts through a voice-over. Although the voiceover in film-noir is an indication of authority over the plot, the man is kept passive,

submissive and silenced. Hence, according to Christine Wilkie-Stibbs:

�30

If language is perceived as the mode of empowerment and is related to

accession to identity and subjective agency through the paternal authority, and

if language is named in patriarchy as the space from which acculturated

subjects may speak their lives, the loss or lack of it marks out the subject as

powerless, silent or silenced, by extension “feminized,” and as a potential

victim to be exploited, expunged, exterminated. (329)

On account of the man’s silence, his feminisation is yet another means by which the

boundaries between male and female are disturbed. While the speechless man lacks

articulation and expression within the film, the Mother and Daughter who suggest lesbian

desire, personify the groups who are rendered ‘speechless’ in reality and practically

‘abjected’. Especially in a world that is linguistically constructed however, those groups that

are according to Judith Butler ‘unviable (un)subjects – abjects, we might call them – who are

neither named or prohibited within the economy of the law’, can disorganise culture from

within (qtd. in Berressem 29). Furthermore, by providing a family grouping where the Father

is essentially absent and the Mother is in charge and having sex with the Daughter, the

boundaries between male and female are transgressed once more.

The alternative family grouping and their deviation from the culturally conditioned

femininity, offer potential spaces for women characters and viewers to act out their repressed

desires in fictional form. As it is a horror text, the activities of this released libido are

manifest in dark and disturbing shapes (Powell 155), through the psychopath characters. The

psychopath characters function within a house in which women would be ‘normally’

confined in real life, but in this case becomes a space of pure evil. The female psychopath

according to Jermyn is ‘woman's abject since she crosses the borders other women are forced

to maintain, lives out their fantasies about escaping their place in the symbolic, and, in her

�31

defeat at the end, represents women's necessary attempts to expel their desire for the abject’

(255).

1.e The Composite

When death interferes with what is supposed to save us from it, the composite comes forth.

One of the composites in Singapore Sling, is placing the clean and the dirty together. The

most illustrative instance is the scene where the Mother and the Daughter disembowel Laura

over the kitchen sink. The sink is normally a space of cleansing and within seconds receives

Laura’s bloody viscera and is converted into a space of utter Disgust and death (Figure set 7).

The setting of the film is itself a composite, since the mansion which typically connotes

excess protection, becomes the siting of horror. The detective seeks refuge in a domestic

environment which is traditionally a quotidian locus of safety, but gets raped and tortured

instead. When the Mother, who is the symbol of love and protection, rapes and tortures her

Daughter, she provides us with an additional composite. Another composite paradigm is the

Daughter, who personifies innocence and violence appearing side-by-side (Goodnow 38),

through the way she speaks. She is a stutterer, she has quirks, ticks, she stammers, splutters

and she hiccups while she speaks. All these give her an infantile, seemingly innocent status

which is not consistent with her vengeful and murderous personality. She also exposes her

vagina several times. Since this is taking place within a horror film, it makes one ponder how

society, by referring to the vagina with words such as ‘gash’ or ‘slit’, turns the woman’s

genitals into a composite. Society linguistically ascribes to them characteristics that connote

threat to life, whereas at the same time comprehends and recognises the literal life-giving

qualities. Finally, to join Abjection and Disgust together once more, McGinn notices:

Death may be a necessary condition of disgust, but it is not a sufficient

condition. . . It is death in the context of life that disgusts. . . Disgust occurs in

that ambiguous territory between life and death, when both conditions are

�32

present in some form: it is not life per se or death per se that disgusts, but their

uneasy juxtaposition. . . Disgust occupies a borderline space, a region of

uncertainty and ambivalence, where life and death meet and merge. (87-90)

2. Images of Pollution and Disgust

In order for a film to be considered abjective, along with boundaries that have collapsed there

have to be images of pollution as well. To remember Hal Foster, images of ‘vomit and shit,

decay and death’, evoke abjection because they serve as a representation of the body thrown

out – literally abjected (112). In Kristeva’s words, ‘[c]ontrary to what enters the mouth and

nourishes, what goes out of the body, out of its pores and openings, points to the infinitude of

the body proper and gives rise to abjection’ (108). In general it is hence agreed that ‘[a]bjects

tend to centre around bodily openings through which exchanges with the environment are

materially regulated and channelled’ (Berressem 42). When these exchanges become

excessive (for instance when there are uncontrollable flows and fluxes such as bleeding or

diarrhoea), or when they are reversed as in the case of vomiting, abjects are created.

(Berressem 43). As indicated above, faeces and vomit are usually interrelated. That is

because as Miller has observed:

The mouth and the anus bear an undeniable connection. They are literally

connected, each being one end of a tube that runs through the body . . . Once

food goes into the mouth it is magically transformed into the disgusting.

Chewed food has the capacity to be even more disgusting than feces . . . The

sight of chewed food, either in the mouth or ejected from it, is revolting in the

extreme. . . The true rule seems to be that once food enters the mouth it can

only properly exit in the form of feces. This helps account for why vomit may

be more disgusting than feces. (96)

�33

Singapore Sling abounds in such images. One case in point is the Daughter vomiting on the

man while she rapes him. But a moment which stands out is at the family table, when the

women chew their food, make it visible to the audience by pulling it out and they even throw

up because of eating too much. The Daughter is clearly excited when she vomits, but the

Mother seems disgusted by it, causing her to be sick as well but without hesitating to do so on

the table. She even chews the food and feeds it to the man (Figure 5), placing the scene

among what I believe is one of the most disgusting ones in the film. Those images of filth and

vomit are abject in account of being unruly and disorderly as well, since they disturb the

system, the order and the rules of cinema which are established through agencies of order

such as setting, costume, tempo etc (Johnston 23).

Blood is another substance that pours out of the body giving rise to abjection.

Kristeva describes it as ‘a fascinating semantic crossroads, the propitious place for abjection

where death and femininity, murder and procreation, cessation of life and vitality all come

together’ (96). Blood is an indication of the boundaries between inside and outside having

collapsed, since it presupposes rupture on the skin that serves as our protector from viewing

what lies inside us. It functions as a border that keeps our intestines and blood inside and

gives a sense of wholeness of self. Therefore cuts in the skin connote a collapse of that

border: ‘It is as if the skin, a fragile container, no longer guaranteed the integrity of one's

'own and clean self but, scraped or transparent, invisible or taut, gave way’ (Kristeva 53).

Needless to say, in a horror film such as Singapore Sling, cuts in the skin could not be

missing. In fact they go beyond mere ‘cuts’ and appear in the form of gashes and