tarting from the notion of ‘post-democracy’ elaborated by Colin Crouch,

which indicates an increasing tendency towards the deterioration of

democratic principles and the narrowing of the public sphere, this book

explores how, in the Dutch context, this process is influenced by theatre

and performance practice, art policy and governmental action. It points

out that, within discourses of post-democracy, aspects of depoliticisation

are commonly assessed through theatrical concepts such as spectacle,

play, game and theatre.

At the same time, this work argues by an analysis of three performances,

‘Wijksafari Utrecht’ by Adelheid Roosen, a political protest by Quinsy

Gario, and ‘Labyrinth’ by the refugee group ‘We are Here Cooperative’,

that there might be a role for theatre in this age of depoliticisation. It

proposes to scrutinise, based on the writings of Samuel Weber, a paradox

of theatre. Namely, while concepts of theatre are applied to convey

disapproval of government and politics, theatre has a possible emancipatory character to dispute the given order.

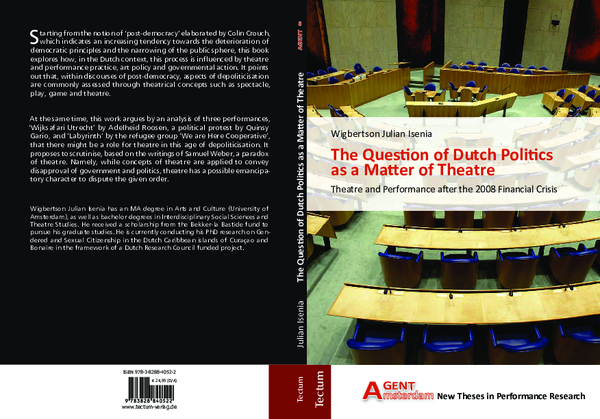

Wigbertson Julian Isenia

The Question of Dutch Politics

as a Matter of Theatre

Theatre and Performance after the 2008 Financial Crisis

€ 24,95 (D/A)

www.tectum-verlag.de

Tectum

ISBN 978-3-8288-4052-2

Tectum

Julian Isenia

Wigbertson Julian Isenia has an MA degree in Arts and Culture (University of

Amsterdam), as well as bachelor degrees in Interdisciplinary Social Sciences and

Theatre Studies. He received a scholarship from the Bekker-la Bastide fund to

pursue his graduate studies. He is currently conducting his PhD research on Gendered and Sexual Citizenship in the Dutch Caribbean islands of Curaçao and

Bonaire in the framework of a Dutch Research Council funded project.

The Question of Dutch Politics as a Matter of Theatre

S

AGENT

8

AGENT

New Theses in Performance Research

�ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I want to thank those who have aided me theoretically in writing

this MA thesis, especially Professor. Dr. Kati Röttger. Without you,

this MA thesis would have never been devised. Dr. Jan Lazardzig

and Dr. Sruti Bala for an amazing and inspiring year. You have each,

in your distinct way, instigated a passion in me for research and

writing. I am indebted to my partner Daniel van Dijck for helping

me carry on. My parents and sisters for their moral support.

Friederike Ernst for her generous help, and especially Roberto

Tweeboom and Paul Brand for the proofreading. I would like to

acknowledge the valuable input by Adriano Jose Habed. Special

thanks to artists Quinsy Gario and Nicolas Stemann to whom I could

always go to without any hesitation and for being an inspiration for

this thesis. Even though others have contributed in many ways to

this thesis, I am responsible for the omissions, errors and

conclusions. My gratitude goes to Stichting Bekker la Fostide, who

made the school year financially possible. The University of

Amsterdam and the Echo Foundation, who have (unknowingly)

forced me to assess critically the world I live in.

And lastly to Rennes, Zagreb, Antwerp, Modena, Tokyo, Paris,

Dublin, Valence and not to forget Angelica Liddell, and all my

colleagues (students and actors) that all made this journey last just

long enough.

| 5

�6 |

�PREFACE

Due to the neoliberal agenda of the Dutch cultural ministry in recent

years, the younger generation of theatre makers and scholars in The

Netherlands is confronted with a drastically shifting field of cultural

politics and harsh consequences for the status of theatre. This

problem is aggravated by the lack of a profound analysis of these

developments. Against this backdrop, the significance and actuality

of the thesis Julian Isenia is presenting here, cannot be

underestimated. While being clearly focused on Dutch cases, the

topic extends much further, critically resonating the global problem

of post-democracy which encompass depoliticisation and the

narrowing of the public sphere.

For the sake of in-depth analysis, Isenia has chosen for a double

agenda that is clearly announced in the title of this book: The

Question of Dutch Politics as a Matter of Theatre. Theatre and

Performance after the 2008 Financial Crisis indicates the double-bind

notion of theatre at stake here, which is explained and implemented

in the first chapter. It covers the tension between the Platonian

metaphorical use of the notion to indicate a false theatre of politics

on the one hand and a notion that – in the course of Hanna Arendt stresses the inherent political impact of theatre constituting public

sphere. Delving into the critic on the ongoing deterioration of

democracy – coined by Colin Crouch with the term post-democracy

– he highlights the antitheatrical attitude lurking behind. He shows

to which extend critical approaches to post-democracy are pervaded

by (anti)theatrical terms like the “illusory, deceptive, exaggerated,

artificial, or affected. (…) [And] the acts and practices of roleplaying, illusion, false appearance, masquerade, façade, and

impersonation” (Davis, Postlewait). Making these concepts and

terms an integral part of his analysis, the specific merit of the thesis

| 7

�is the aim to deconstruct the antitheatrical binary inherent in this

approach. Or in the words of Isenia: “The aim of this thesis is to

change the value of the concept of theatre; to transform a ‘bad’ term

into a ‘good’ one and vice versa, and enable a deep understanding of

theatre and politics, not as separate entities, but as processes in a

conundrum with each other” (p. 7).

This more general proposition is concretely linked up with two

questions: “How do these symptoms and characteristics of postdemocracy and theatricality define current Dutch politics?

Moreover, what are the ramifications of this diagnosis for the

question of our democracy, as well as for the worlds of the arts and

the theatre in the Netherlands?” (p.8)

To dispute these questions, Isenia starts with an analysis of the

general election in The Netherlands in 2010 to find out what kind of

theatre is currently performed in politics. Concluding a narrowing of

the public sphere and a radical trend of the Dutch neoliberal

government to restrict certain rights and social services under the

disguise of freedom of choice, responsibility, independence and

efficiency, he explores how these aspects both influence and are

influenced by theatre and performance practice, art policy and

governmental action. Analyzing in a second step the current

inheritance of these new politics, he delves into the cultural policy

agenda. More concretely, departing from a letter to the House of

Representatives, from the succeeding Minister of Culture, Jet

Bussemaker, Cultuur Verbindt: Een Ruime Blik op Cultuurbeleid

(Culture Unites: A Broader Interpretation of Culture Policy) (2014), he

concludes that she took her predecessor’s plans further by asserting

that not only should art institutions “be flexible and potent” and

take (financial) risks, but more importantly that the relationship

between the arts and other social domains should be brought

forward more coherently. “Artists, the Minister assesses, ‘should

take responsibility for the social context in which [their artworks]

take place’. This cryptic formulation gets a relatively concrete

interpretation when Minister Bussemaker links a specific social

problem to the domain of art” (p. 31), making the relationship

between culture and three social domains - healthcare, sport and

education - explicit by means of examples from the art world that

can be used as a benchmark for others.

In the following, he presents three performance-cases to explore

the consequences of this policy agenda for performance practice and

8 |

�the question to which extend theatre can re-politicise the public

sphere.

While the first example, Wijksafari Utrecht by Adelheid Roosen

(2013), presents the problem of being benchmarked by the

governmental politics to prove art’s instrumentalisation to deal with

social problems, the other two cases are chosen to demonstrate to

which extend – as the last chapter is headed – performance can

become a political affair. The first case in this is a clear example of so

called artivism. It highlights the case of Quinsy Gario who

performed an intervention into the popular arrival ceremony of

Sinterklaas (Sint Nicholas) protesting against the tradition of staging

a parade of “Zwarte Pieten”, the blackface ‘helpers’ of the Sint.

Together with another activist, he had posed alongside the parade

carrying a banner with the text “Zwarte Piet is Racisme” (Black Pete

is Racism), for which reason they were arrested violently by the

police. While this case “served as a catalyst to re-politicise the

discussion around Black Pete” (p. 48), the last example undermined

governmental power structures by drawing attention to the

refugees’ state of being. It was a participatory theatre project led by

the ‘We are Here Cooperative’ under the direction of Nicolas

Stemann that staged the production Labyrinth (2015).

The ‘We are Here Cooperative’ consists out of approximately

200 refugees that are out of procedure (Wijzijnhier.org) residing in

Amsterdam. For all of them, the asylum applications have been

refused, and all legal remedies have been exhausted in the

Netherlands, in spite of the fact that they could not return to their

home country. Together, they wrote a play about their own

experience with the Dutch asylum policy and performed it

confronting the audience with an uncomfortable and confusing

experience.

Drawing on theories of Jacques Rancière, Pascal Gielen, Martin

Jay, Colin Davis, and – last but not least - Colin Crouch, Julian Isenia

offers detailed and careful analyses of the three cases to provide

important insights into the vibrant question how theatre could be

able to re-politicise post-democratic public spheres. A book that

should be recommended for theatre students and makers who are

interested in the actual problems of the fields they are aligned with.

Kati Röttger

Amsterdam 2017

| 9

�10 |

�1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1

DUTCH POLITICS AS A MATTER OF THEATRE .................. 13

2

DIAGNOSING A POLITICAL MALAISE ............................. 27

2.1. The 2010 Dutch general election and its aftermaths ......... 27

2.1.1 The Binnenhof deliberations ...................................... 29

2.1.2 The coalition agreement ........................................... 30

2.1.3 The Catshuis deliberations ........................................ 32

2.2 Why post-democracy? ................................................. 35

2.2.1 The Dutch Polder Model and

the idea of governmentality ...................................... 35

2.2.2 The trivialisation of politics: is it the media? ................ 37

2.2.3 Active citizenship, participation society and apathy ....... 40

2.3 The theatricalisation of politics. What theatre? ................ 41

3

THE STATE ASSUMING A MORE CEREMONIAL AND

THEATRICAL ROLE ...................................................... 45

3.1 The inheritance of the Rutte I cabinet ............................ 45

3.2 Wijksafari Utrecht by Adelheid Roosen ........................... 48

3.2.1 Zina Neemt de Wijk ................................................. 51

3.2.2 Wijksafari en Tepito ................................................. 53

3.3 The instrumentalisation of the arts?............................... 55

3.3.1 Recent developments within citizen initiatives and

participatory art ...................................................... 58

| 11

�4

RE-POLITICISING THE PUBLIC SPACE ............................ 61

4.1 The Question of Democracy .......................................... 61

4.2 Protest by Quinsy Gario ............................................... 63

4.3 Politics as theatre, theatre as politics ............................. 73

5

THE POLITICS OF AESTHETICS

AND THE AESTHETICS OF POLITICS ............................. 77

5.1 Labyrinth by We are Here Cooperative

and Nicolas Stemann ................................................... 77

5.2 Citizenship, democracy, and humanity ........................... 84

5.2.1 Democracy: a distinction between

human rights and the rights of the citizen? .................. 85

CONCLUSIONS .................................................................. 89

WORKS CITED .................................................................. 95

12 |

�1

DUTCH POLITICS AS A MATTER OF THEATRE

The final step is that we need to stimulate our cultural and creative

industries to add value to society. We have to take them beyond the

boundaries of the cultural world and help them to connect with other

areas of society, such as healthcare, infrastructure and environmental

sustainability. This goal is rooted in our growing awareness of how

fruitful these crossovers can be, both today and in the future

(Rijksoverheid, 2014c)1.

In this thesis, I want to engage in an enigmatic and unsettling

political development of our time, often delineated as a shift towards

post-democracy, since, in my view, to some extent, similar

mechanisms prevail in contemporary Dutch politics. The notion of

post-democracy broadly encompasses the inclination towards

processes of (1) depoliticisation – “a governing strategy [that places]

at one remove the political character of decision-making” (Burnham,

2001, p. 128) and the privatisation of public services in the

Netherlands. In the case of outsourcing of government tasks, a

private party bent on maximising profits but performing a public

task, democratic control, transparency and moral accountability are

increasingly compromised (Graaf, 2015). (2) The deterioration of

democratic principles – by increasingly denying some ethnic and

religious minorities full citizenship due to the supposed “threat to

the Dutch progressive moral order” (Hurenkamp, Tonkens, &

Duyvendak, 2012, p. 130) and (3) the narrowing of the public sphere

in neoliberal governments – by labelling certain aspects of life as

______

1

The translations of non-English texts and quotes are mine when not stated

otherwise.

| 13

�‘private’ (as racist cultural practices such as ‘Black Pete’2) and thus

not admissible to the public domain (Fraser, 1990) and not to be the

concern of the state. Political scientist and sociologist Colin Crouch,

coined this term in his critically acclaimed book Post-democracy

(2004)3 and persuasively articulates this tendency. “Under this

model,” Crouch asserts:

While elections certainly exist and can change governments, [the]

public electoral debate is a tightly controlled spectacle, managed by

rival teams of professional experts in techniques of persuasion, and

considering a small range of issues selected by those teams. The mass

of citizens plays a passive, quiescent, even apathetic part, responding

only to the signals given them. Behind the spectacle of the electoral

game, politics is really shaped in private by [the] interaction between

elected governments and elites that overwhelmingly represent

business interests (2004, 4 emphases added).

Following Crouch, the theatrical concepts of ‘spectacle, ‘playing a

part’ and ‘game’4 seem to have in this sense some similarities with

the notion of post-democracy. The participation of the citizen is

apparently weak, as Crouch describes “the mass of citizens plays a

passive (…) part” (Crouch, 2004, p. 4) in the political arena,

reminiscent of the perceived passive spectator within the theatre

(Rancière, 2009). Also, in the words of Crouch, “behind the spectacle

of the electoral game” (Crouch, 2004, p. 4), the government, as an

______

2

Sinterklaas and Black Pete (Dutch: Black Pete), a holiday tradition in the

Netherlands, clearly show that old habits die hard. Opponents of this

black-faced helper of Sinterklaas reiterate the offensive caricature of black

people, but supporters, in turn, say that Black Pete is not at all offensive,

and the celebration is a tradition that needs to be cherished. The United

Nations urged the Netherlands to stop this racist portrayal of black people

(United Nations, 2014), but the government reaction was that this

celebration was a private celebration and not to be the concern of the state.

3

Crouch first introduced this term in an earlier work Coping with PostDemocracy (2000)

4

Concerning the word game, Willmar Sauter explains, “The basic experience

of art is playing. Playing has its own rules, and those who participate,

subordinate their will to the rules of the game. The game is playing the

players, as [Hans-George] Gadamer [in ‘Truth and method’] puts it:

something is being played. In the case of art, this playing is also a playing

for someone, an observer, a spectator” (Sauter, 2000, p. 5). In this sense, I

consider the word game also as a theatrical concept.

14 |

�actor playing a role on stage (Goffman, 1959)5, gives the impression

of representing the best interest of the citizenry, but allegedly

mostly serves the interest of “privileged elites in the manner

characteristic of pre-democratic times” (Crouch, 2004, p. 6). To be

more precise, Crouch borrows theatrical terms and concepts not

merely to label politics or the government as inauthentic or artificial,

but to denote a shift towards less interest in strong egalitarian

policies for the redistribution of power, where democratically

advanced societies6 “have gone beyond the idea of rule by the

people to challenge the idea of rule at all” (Crouch, 2004, p. 21). Here

Crouch deploys the language and terms of theatre and theatricality,

as epithets, to explain a phenomenon characterised by ordinary

people being increasingly squeezed out of the affairs of state while

the economic elite supposedly becomes more and more powerful

(Crouch, 2014, pp. 116–117). In the previous quotation, Crouch also

uses the idea of the perceived passive and apathetic spectators, as in

a theatre, to express the growing incapacity and unwillingness of

citizens to address the current so-called post-democratic tendency.

The domain of politics becomes increasingly de-politicised.

Dwelling on Jacques Rancière’s critique on the perceived

passivity of the spectator (Rancière, 2009, pp. 3–6), the question

arises: “what makes it possible to pronounce the spectator seated in

her place inactive, if not previously posited [a] radical opposition

between the active and the passive?” (2009, p. 12). In our case, what

makes it possible to pronounce the citizen inactive, if not beforehand

assuming that the citizen is passive and more importantly that

she/he/they7 needs to be ‘activated’? Furthermore, what allows us to

insert the prefix ‘post-’ to the concept of democracy, without

questioning the very idea of representative democracy, which is

defined by a “power-laden division between ruling and beingruled”? (Green, 2010, p. 53) A beforehand assumption connected to

this idea is that there is a kind of a mythical past in which

______

5

In this specific citation, the notions of ‘front’, where the individual

performs before a set of observers, and ‘backstage’, where the individual

can polish his or her performance without incurring any judgment by the

observers is especially noteworthy.

6

Colin Crouch sees Japan, Western Europe and the United States of America

as part of the advanced democratic societies (Crouch 2004, 1).

7

They as a personal pronoun of undetermined gender

| 15

�representative democracy was ‘authentically’ democratic and people

were fully involved in democratic processes. In this thesis, I want to

rethink and problematize the very idea of representative democracy

without asserting the need to replace citizens or “the audience,

previously conceived as a ‘viewer’ or ‘beholder’ (…) [uncritically

with] co-producer or participant” (Bishop, 2012, p. 2). Participation

encouraged by the state, as Claire Bishop argues, seemed to be

perceived as corresponding to collectivism; to a collective control

over production and distribution. However, this trend needs to be

more thoroughly addressed “in tandem with the dismantling of the

welfare state” (2012, p. 5) as a vital element in the post-industrial

neoliberal capitalistic policy (2012, p. 14).

One might say that within the discourse of Crouch’s postdemocratic writing there seems to be an ‘anti-theatrical prejudice’ in

the way terms and concepts of the theatre are appropriated to

convey disapproval of government and politics (Barish, 1981).

However, rather than eschew derogatory, belittling or disapproving

terms derived from theatrical activity from my research (for example

‘spectacle,’ ‘playing a part’ and ‘game’), I want to make these

concepts and terms an integral part of my analysis. The aim of this

thesis is to change the value of the concept of theatre; to transform a

‘bad’ term into a ‘good’ one and vice versa, and enable a deep

understanding of theatre and politics, not as separate entities, but as

processes in a conundrum with each other. Theatre, as Barish

suggests, due to the ontological prejudice it clings to from the

writings of Plato, Rousseau and Nietzsche among others8 - a

prejudice that seems to be “a condition inseparable from our beings”

(Barish, 1981, p. 2) - might “reflect something permanent about the

way we think of ourselves and our lives” (Ibid). By scrutinising the

ocular (visual) model of democracy and the spectator-citizen, we

might find how spectatorship can empower ordinary citizens and

“provide them with a sense of solidarity with other ordinary citizens

[that are] also consigned to experience politics […] in a spectating

capacity” (Green, 2010, p. 28).

Still, how do these symptoms and characteristics of postdemocracy and theatricality define current Dutch politics?

______

8

16 |

See Rousseau 1968 and Deleuze 1986, due to the scope of this thesis I will

be only discussing Plato.

�Moreover, what are the ramifications of this diagnosis for the

question of our democracy, as well as for the worlds of the arts and

the theatre in the Netherlands? Kati Röttger throws more light on

this matter in her essay “Theaterwetenschap aan de Universiteit van

Amsterdam in de Eenentwintigste Eeuw” (Theatre Studies at the

University of Amsterdam in the Twenty-First Century), specifically

within a Dutch theatre policy context. Röttger starts her delineation

with reference to the 2008 financial crisis, which resulted in drastic

economic reforms in various aspects of life in the Netherlands. In a

far-reaching austerity campaign, the government has expressed a

desire to limit its role in subsidising sectors such as art and

education, among others. The former policy of public subsidies is

labelled ineffective; “it is said that [the state] is financing leftist

hobbies: a government bureaucracy that has cuddled the arts to

death and led to the culturing of addict institutions” (Röttger, 2014,

p. 92). These sectors should instead be more efficient, more

resourceful, and creative, and are only denominated in financial

terms (2014, Ibid). “This undemocratic act,” Röttger assesses, due to

“the rapid pace in which the policy change is implemented” without

any dialogue, rightly raises the question, “for whom is such an

effective subsidy actually an advantage: for the arts or the [financial]

market?” (Ibid my emphasis). Röttger asserts, through an analysis of

sociologist

Pascal

Gielen’s

essay

Creativity

and

Other

Fundamentalisms, that in this construction the arts are called upon to

mimic the corporate world's characteristics, “to strengthen the

economic potential of culture and creativity” (2014, Ibid), as well as

creatively adapt to the financial market to guarantee infinite

economic growth.

What is interesting about these two essays, within the context of

this thesis, is that both Röttger and Gielen indicate the increasing use

of the word creativity in government policies and austerity measures

related to the cultural sector, and likewise the designated specific

role the arts and theatre should fulfil within society. The government

encourages entrepreneurship and philanthropy to dispense with a

culture of public subsidy dependency9, where little attention is

______

9

See for example the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science and the

Ministry of Economic Affairs its policy document ‘Ons Creatieve

Vermogen’ (Our Creative Capacity): “Creative industries are being

stimulated to gain more insight into market opportunities. (...) However,

| 17

�apparently given to public outreach. This new strategy of

government policy, however, ignores the fact that precisely through

the system of government subsidies, the professionalisation of Dutch

avant-garde theatre took off in the ‘60s (Röttger, 2014, p. 93).

Moreover, as argued by Crouch, by displacing the distribution of

power increasingly towards concentrations of private businesses and

wealthy elites, a self-referential political class is conceived, which is

increasingly more preoccupied with creating lasting relationships

with wealthy businesses and funding bodies than with pursuing a

political agenda that meets the common interests of ordinary people

(Crouch, 2004, pp. 4–5).

In this sense, and to return to current Dutch politics, although

both authors do not actually employ the term post-democracy in

their writings, the essays not only describe specific symptoms of an

inclination towards processes of depoliticisation in the

Netherlands10, but also offer clear examples of how the concepts of

theatre and theatricality are unceasingly intermingled with the

question of politics and the gradual limitation of democratic systems

respectively. This gradual limitation of democracy is increasingly

more visible, as Gielen argues in the role played by mass media

(Gielen, 2013, p. 74). The mass media, such as newspapers, TV and

radio, which are highly concentrated within a small group of key

players in the Netherlands and naturally unchallenged11, do echo not

we are still not using these economic opportunities to their full potential.

Primary cause: creativity and economy are too two divorced worlds. (…)

What we don't not know, we fear. Because of this, there is insufficient

dynamics in the chain from initial creation to marketing. In addition,

subsidised sectors from the creative industries are unilaterally dependent

on the government. They have insufficient access to private money from

patrons and sponsors, and entrepreneurship has not been sufficiently

developed” (Rijksoverheid, 2009, p. 3).

10

Röttger discusses the limitation of the government’s (financial) role in the

culture, education and heritage sector. In contrast, these sectors should

position themselves as entrepreneurs. This has major implications for our

democracy, she assures, since hardly any time is taken to assess common

ways we would want to advance. Gielen, in contrast, uses the words depoliticised and apolitical in his writing when he describes a neoliberal

trend to measure, manage and control liberty.

11

The Dutch Media Authority (Commissariaat voor de Media), which

regulates and supervises the Dutch Media Act, concluded that the

18 |

�only politics but also produce a political reality that is suited to

their demands. “The [Dutch] mass media,” Gielen explains

through an analysis of Walter Benjamin’s The Work of Art in the Age of

Mechanical Reproduction, is “the expression of a stylised barbarism,

an aesthetics of persuasion that also aestheticizes politics. In the

mass media, politics becomes theatricality (…), in which good

arguments are always defeated by good looks” (2013, p. 75).

This meaning of theatre, employed by Gielen as an adjective

to describe a particular quality of Dutch politics, is quite different

from the one Röttger applies in her essay. Röttger, in contrast, sees a

role for theatre in this age of depoliticisation. Although Röttger

never employs the terms depoliticisation or post-democracy, she

rightly reiterates the increasingly undemocratic way in which the

government acts in the implementation of austerity measures. “In a

very un-democratic way, no time is taken to jointly reflect on how

people want to address [the budget cuts within] the arts in the

Netherlands as a society” (2014, p. 93). At the same time, theatre and

theatre studies are increasingly determined by efficiency and

participation policies. When is there democratic participation by the

arts in shaping the idea of an equivalent human community; and

when is participation by the arts within the idiom of

entrepreneurship and market logic defined as stimulating the

formation of an audience” (2014, p. 98). Theatre and performance

studies, she contends, have an important task to respond to these

developments in a pragmatic and idealistic manner. Röttger

undersigns Alain Badiou’s idea of theatre in his Rhapsody for the

Theatre. “Theatre,” she asserts, “is of all the arts that [which is]

homologous to politics, in that theatre is the place where a truly

emancipated collective subject is performed” (Röttger, 2014, p. 107).

As Badiou rhetorically asks, “what does theatre talk about if not the

state of the State, the state of society, the state of revolution, the state

of consciousness relative to the State, to society, to the revolution, to

politics?” (Badiou, 2013, p. 36) Röttger also emphasises, on the basis

of Jean-Luc Nancy’s Being Singular Plural, “That theatre — also in the

Netherlands’ “regional and national press sectors are highly concentrated

with three players dominating the markets. The television sector is also

highly concentrated, and three main players, including the public service

broadcaster, RTL/HMG and SBS are largely unchallenged in terms of

competition from other operators” (Ward, Fueg, & D’Armo, 2004, p. 125).

| 19

�sense of spectacle — is the art form that allows for the intensification

of relations, of concentration and fellowship, which are necessary to

offer a new perspective on and the practice of co-existence, of copresence, in a being-singular-plural, to be created” (2014, Ibid). Thus,

how theatre can contemplate on the idea of a plural society, without

reducing this ‘we’ into a substantial and exclusive individuality. I

will expand on this argument in the present book by critically

reflecting on the idea of spectatorship in chapter 3 and 4.

The preceding discussion implies that two conflicting

definitions of theatre underlie the statements cited above. One

definition characterises theatre as a political affair, that is, a matter of

critically assessing forms and ways of living together in a communal

space. I will conceive this interpretation of theatre, for the sake of

simplicity, as a positive denomination of theatre. This is the view

that Röttger holds. The term political, within this definition is used

in its broadest sense, encompassing the interrelationships and the

distribution of resources and power in a given society. In contrast,

Gielen, as well as Crouch, offers a different definition of theatre,

where the word theatre is used as an adjective and a metaphor for

something of our contemporary time that masquerades as politics

but, in essence, is not. This interpretation of theatre, I will, on the

other hand, conceive as a negative denomination of theatre. Within

this definition, politics is used in its narrowest sense, encompassing

the daily activities of the government, as well as the electoral vote.

Erik Swyngedouw wonders in his essay Interrogating PostDemocratization: Reclaiming Egalitarian Political Spaces, “whether the

political can still be thought” in a post-democratic context, in which

politics is increasingly reduced “to ‘policing’, to managerial

consensual governing” (Swyngedouw, 2011, p. 376). The political,

deduced from Jacques Rancière’s Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics

(2010) and The Politics of Aesthetics (2006), is understood here as a

retroactive event “of eruption (…), opening a procedure that

disrupts any given socio-spatial order, one that addresses a wrong in

the name of an axiomatic and presumed equality of each and every

one” (Swyngedouw, 2011, p. 375). “This wrong”, he asserts, “is a

condition in which the presumption of equality is perverted through

the contingent socio-spatial institution of an oligarchic police order.

The political arises then in the act of performatively staging equality, a

procedure that simultaneously makes visible the wrong of the given

situation” (2011, p. 375). On the basis of the description above, it

20 |

�seems fair to suggest that despite the negative connotations of

theatre defining our contemporary representative democracy, there

seems to be, on the other hand, a potential emancipatory value

within theatre and performance, which acts as a possible rupture,

disrupting the given order, thus which can interrogate the

established and accepted question of democracy.

Following this observation, the primary argument of this

thesis is that, although ‘Dutch politics as a matter of theatre’ (c.f.

Crouch 2004; Gielen 2013) and ‘performance being a political event’

(c.f. Swyngedouw 2011; Badiou 2013; Röttger 2014) are two

problematics that differ radically from each other in their use of the

notion of theatre, they are perhaps intimately related, or at the very

least react to one another. This work sets out to explore the widely

neglected post-democratic enigma in a Dutch context, to examine the

potential theatre and performance have to reflect upon or slightly

irritate the state of affairs. Theatre and performance, as I will argue,

can play a major role in their ability to materialise and discursively

foster a political arena.

This necessity of this book is emphasised by the radical trend

of the Dutch neoliberal government to restrict certain rights and

social services under the disguise of freedom of choice,

responsibility, independence and efficiency. These plans are

presented as necessary evils and unavoidable, causing the public not

to question or reject these plans and ultimately adopting this

discourse. Art and creativity, and specifically in the context of this

thesis, theatre, are being drastically instrumentalised within

governmental policies with the result that these have become

increasingly empty and vague concepts. On top of this, the

legitimacy of the cultural connoisseur, specialised in various arts

sectors, which can provide a possible critical view, seems to be

increasingly undermined. As Jet Bussemaker, Minister of Education,

Culture and Science states, “the authority of the traditional expert or

culture specialist is decreasing [according to whom, I might add?]; at

the same time, the public needs experts to guide [them] in the

supply [of cultural manifestations]” (Rijksoverheid, 2015a). Art

scholars and critics are thus devalued to be merely salesmen,

| 21

�contracted out to compile appealing sales brochures12, which may

result in an increasing cultural and historical amnesia (Gielen, 2013,

p. 40), which then further complicates possible critical advances.

Before us lies a pressing question to re-conceptualise the question of

theatre and re-weight its potential, especially in light of the growing

concern about the future of our democracy. The present work is an

attempt firstly to map these trends of depoliticisation and

theatricality, and subsequently to describe contemporary theatre

projects against the backdrop of these developments.

To fully comprehend this line of reasoning, I set out to disclose

in Chapter 1 Diagnosing a Political Malaise the Dutch general election

of 2010, which revolved heavily around the European debt crisis and

the growing national debt. Through a discourse analysis of

newspaper articles, economic analysis and forecasts of the

Netherlands Bureau of Economic Policy Analysis (CPB), political

election campaigns and government documents, I argue that politics,

necessitates a specific performance in order to be prosperous. That

is, the voters must have the impression that the politician did

everything in their position ‘backstage’ to serve the interests of the

people and that the austerity measures were inevitable, even though

this might not always be the case. This framework will help me to

conceptualise the power dynamics that underlie the social relations

between politicians, on the one hand, and citizens, on the other, and

how politicians mask and adopt theatrical roles. However, we might

ask, what follows when politics becomes increasingly theatrical, and

what are the immediate implications of this?

Based on this material, further questions concerning the

theatricality of Dutch politics will be discussed. In Chapter 2, The

State Assuming a More Ceremonial or Theatrical Role, I will analyse the

socially engaged location-based theatre production Wijksafari Utrecht

______

12

22 |

As the former Minister of Education, Culture and Science stated, “The

changes in the assessment system are also intended to create more

widespread support. In the past, when the emphasis was almost

exclusively on artistic quality, the assessment of the arts was left to 'the arts

and culture experts'. Now, there is often more room for experts in various

other fields of study (for example business management, marketing or

cultural education) and more attention is paid to the (potential) interest of

the public” (Rijksoverheid, 2012a).

�by theatre director Adelheid Roosen. Wijksafari Utrecht is a theatre

project where the stories and lives of several migrants from the

Middle East and Sub-Sahara Africa, among others, are blended into

a theatrical performance. The spectator gets the opportunity to relate

to ‘foreign’ cultures and practices and gets a chance to experience,

guided by a local, problem areas in three contested neighbourhoods

of Utrecht (Overvecht, Zuilen and Ondiep). The project fabricates a

caricature portrayal of these migrant locals to play with the

expectations and stereotypes the viewers have of them.

However, this project becomes critical when it is used as a

benchmark by the government for how the arts can assume an

instrumental role to resolve societal problems and thus, as the

Minister of Education, Culture and Science asserted, “to take full

advantage of the added value of creativity, in all kinds of social and

economic ways” (Rijksoverheid 2014; see also Ministerie van

Onderwijs 2012). This project, I will argue, despite its noble

intentions, can be seen as a possible catalyst of the theatricality of

current Dutch politics. That is, following Claire Bishop (2012), the

more theatre groups and private organisations adopt the state its

obligations, the more politicians can assume a ceremonial or

theatrical role. This liberal government defines the individual as selfadministered and self-governing, allowing the welfare state to

deteriorate further in so-called democratic, advanced societies.

Crouch points out that those societies, as a result of this

deterioration, will be experiencing a shift that seems to reverse most

of the political achievements made during the twentieth century

(Crouch, 2004, p. 4). Moreover, one might ask, what are the

ramifications for the functioning of our democracy and the way we

can address our problems when the responsibility of the public

services is relocated into our hands? Alternatively, when social

provision is transposed into the hands of a theatre group?

In Chapter 3, The Destabilisation of the Public Space, I will

problematize the notion of theatricality. In this chapter, I will

illustrate the second case study of this thesis, a protest by the

theatre-maker and artist Quinsy Gario. In this chapter as argued by

Zihni Özdil, I will illustrate that the “political economy of Dutch

exceptionalism has both discursively and institutionally served to

exclude black and non-white Dutch people of colour from the public

debate, thus marginalising their voice and delegitimizing them as

cultural stakeholders” (Özdil, 2014, p. 49). However, this protest by

| 23

�Gario, by re-claiming the protest as a performance, visualises,

however temporarily a public space, which exposes that which is

repressed in the hegemony of the social order.

On November 12, 2011, Gario and Kno’ledge protested the

celebration of Black Pete during the national arrival of Sinterklaas.

This event formed part of a large chain of events that re-politicised

what it means to be black in the contemporary Netherlands. Earlier

written accounts of Gario’s political protest will be used to explore

this act. It is important to note that Gario later delineated this event

as part of his work of art. This morphing or rephrasing, I would

argue, offers an unusual perspective, as it gives the opportunity to

review and scrutinise this protest in the context of the arts,

specifically within the realm of theatre. To facilitate this step, I will

attempt to define this protest on the basis of the descriptions of

theatre by William Sauter and by notions of performance and

performativity. The questions that this theoretical framework pose

are as follows. Can this event solely be perceived as a protest, or also

as a (theatre) performance? What connections can be made between

a protest and the notion of theatre? This consideration will

eventually lead to the question: how can cultural-political

intervention, through theatre, broaden the discourse of democratic

politics to include multiple spaces of power. The aim of this chapter

is not solely to feed into current social debates on racism in the

Netherlands, but to illustrate how the voices of minorities are being

repressed within the white Dutch hegemonic order and how these

minorities through their practices create politics beyond the state and

formal electoral politics.

In Chapter 4, The Politics of Aesthetics and the Aesthetics of

Politics, I will discuss the performance Labyrinth by the We are Here

Cooperative in collaboration with theatre director Nicolas Stemann.

In this production, the experiences of refugees are played out and

reflected upon within the context of theatre. By employing roleplaying and role-reversal methods, the audience becomes a refugee

while the refugee plays the lawyer, the case manager or the IND (the

Immigration and Naturalisation Service) officer. The play, as I will

argue, exposes structures of power and powerlessness that would

otherwise remain obscured. The performance addresses notions of

humanity, citizenship and democracy, and revolves around the

questions: who has the right to have rights and who has the power

to decide this? I will use the writings of Hannah Arendt and Jacques

24 |

�Rancière to elaborate what role theatre can take in bringing into

play demands by the refugees who have not yet been

acknowledged as legitimate political subjects in the Netherlands,

and how these subjects interrogate, through theatre, the question of

our democracy.

| 25

�26 |

�2

DIAGNOSING A POLITICAL MALAISE

People may feel vaguely aware that they have little understanding of

what is going on in government and politics, and that they may feel

bewildered that all they hear about are political personalities,

scandals and inflated bits of trivia. But the trail back from there to the

logic of a certain kind of fast-moving market is impossible for them

to find (Crouch, 2004, p. 48).

2.1. The 2010 Dutch general election and its aftermaths

Before starting my line of reasoning, I will describe the Dutch

general election of 2010 to contextualise the actual question

considered. The Dutch general election, which was brought forward

almost a year due to the premature fall of the Balkenende IV cabinet

(2007 – 2010), revolved heavily around the European debt crisis and

the growing national debt. According to the Netherlands Bureau for

Economic Policy Analysis (CPB), austerity measures seemed

inevitable, as the public finances were, in the case of unchanged

policy, not sustainable in the long-term. “The deficit will rise

significantly over the coming decades and will explode the national

debt” (CPB, 2010, p. 3). The question recurring throughout the

general election was not if there should be cuts, but how much and

what.

The conservative-liberal People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy

(VVD) won the election with 31 of 150 seats in the House of

Representatives, followed by the social democratic Labour Party

(PvdA) (30 seats) and the national conservative Party for Freedom

(PVV) (24 seats). A coalition formation between the VVD, PVV and

the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA) (21 seats) had already failed at

a very early stage (NRC, 2010b), and after that a coalition between

| 27

�the PvdA and the VVD proved to be very complicated and timeconsuming due to insufficient common ground (NRC, 2010a). The

turning point in the government formation was the reconsideration

of the PVV to support the minority coalition of the centre-right

Christian Democrats and the Liberal VVD party. This collaboration

came as a huge surprise, given the disparity of the parties’

immigration and cultural policies, and that no clear resemblances

between the parties were apparent in previous electoral debates to

suggest a possible collaboration. While the VVD campaigned for a

restriction of immigration law to refit public finances13, and the CDA

called for a strong policy to address the rapid changes in

demographics and the impact of globalisation on our economy14,

they were not nearly as controversial as the PVV. Geert Wilders, the

political leader of the PVV, campaigned all year long for a ‘Head

Rag’ tax (Dutch: Kopvoddentax) for every Muslim headscarf and an

embargo on the Quran (New York Times, 2010). Wilders argued that

the rising ‘Islamisation’ in the Netherlands can be an economic

disaster: “it corrupts the Dutch education system, (…) drives out

Jews and gays and deteriorate the long-fought emancipation of

women” (PVV, 2010, p. 6). According to some politicians

(NRCnext.nl, 2010; Nu.nl, 2010b), forms of populism, such as

embodied in the forms of the PVV, would ultimately threaten the

______

13

The election campaign programme of the VVD states, “The VVD wants a

fair and restrictive immigration policy. The VVD sees opportunities for

highly educated and knowledgeable migrants to strengthen our country

and our economy. The uncontrolled influx of disadvantaged and lowskilled migrants, however, led to major problems in the neighbourhoods, in

schools, in the labour market and the field of crime. The persistent influx of

disadvantaged migrants counteracts solving integration problems and

must, therefore, be stopped. Thanks to the VVD, necessary steps have been

taken since 2002 to apply a stricter, equitable and consistent asylum and

immigration policy. The VVD wants to continue this policy, and therefore

good monitoring and control of the external European borders are

important ". (VVD 2010, 36)”. (VVD, 2010, p. 36)

14

The CDA election campaign programme states, “The Netherlands remains

committed to protecting people who are subject to prosecution in a

European and international context. However, the widespread support for

the admission of foreigners in the Netherlands is under pressure. Only

clear choices can maintain this support. The CDA stands for the protection

of refugees, but it within a selective migration policy: strictly where it is

needed, accessible where necessary” (CDA, 2010).

28 |

�fate of democracy. Therefore, proper measures should be taken to

combat it. Collaboration with the PVV would logically stand in the

way (Nu.nl, 2010a).

2.1.1 The Binnenhof deliberations

The three-party leaders of the CDA, VVD and the PVV eventually

gathered behind closed doors at the Binnenhof (the political centre

of the Netherlands) to discuss the coalition agreement. Occasionally

they came outside, laughing and talking enthusiastically to

colleagues, albeit without making any comprehensive declaration to

the media standing outside about the ongoing negotiations (NOS.nl,

2010b). When they did exchange information to the press, vague

assurances were given: “there were some questions raised towards a

particular party during the deliberation”, “that they talked about it

in good spirit”. Also, that they will now “deliberate to answer some

of the questions raised” (Ibid). Alternatively, “That the

conversations were going well and although these discussions were

intense, the political leaders had every reason to be confident that

everything will work out all right” (NOS.nl, 2010a). The coalition

negotiations were interrupted at one point due to the withdrawal of

three dissidents of the CDA party that threatened the parliamentary

majority (Nu.nl, 2010c), but after a miraculous and unknown

“political development,” the three parties regained confidence in

each other and could continue their negotiations (NOS.nl, 2010c).

Meanwhile, a demissionary cabinet (or caretaker cabinet), the

former Balkenende IV coalition, led by the former party leader of the

CDA, conducted a 3.2-billion-euro austerity plan on measures to

restore public finances (Rijksoverheid, 2010b)15. Amidst the ongoing

coalition negotiations, the demissionary cabinet, with the approval

of the States-General of the Netherlands, had implemented, largely

unnoticed or uncontested by the media or the coalition opposition, a

set of actions with far-reaching consequences (Nu.nl, 2010d),

without ever jeopardising its prestige, since they had already

resigned, and most of the politicians of the Balkenende IV cabinet

had secured a job outside politics (only three ministers of this

cabinet returned to politics). Moreover, at the same time, the

demissionary cabinet, by way of this procedure, could pave the way

______

15

See also how the Dutch media have covered this story (Joop.nl, 2010)

| 29

�for the forthcoming government to start more or less with a clean

slate. As the resigned Minister of Finance assured, “The caretaker

cabinet (…) [wants to] delegate the state budget ‘clean and tidy’ to

the next government” (Joop.nl, 2010).

2.1.2 The coalition agreement

113 days after the election results, Mark Rutte, leader of the VVD

and soon to become prime minister, presented a coalition and

‘support agreement’ (Dutch: gedoogakkoord), with the title: ‘Vrijheid

en Verantwoordelijkheid’ (Liberty and Responsibility), indicating the

neoliberal notions of empowerment and policing. Liberty here

meant freedom for private property owners, multinationals and

businesses to pursue their endeavours freely without the

interference of the government. “This government,” as the coalition

agreement emphasises, “believes in a cabinet that only does what it

needs to do” (Rijksoverheid, 2010c, p. 3). This statement specifically

implies making “space for entrepreneurship” (Ibid), corporations

and businesses. However, in contrast to the state, these companies

and businesses do not need to be called to account and have no

responsibility whatsoever for the diverse and demanding Dutch

population.

The term responsibility in the title of the coalition agreement

implies in a neoliberal state, personal liability, as David Harvey

explains, where “the social safety net is reduced to a bare minimum

in favour of a system that emphasises personal responsibility”

(Harvey, 2005, p. 76). The point made by Harvey is not made

unambiguously in the coalition agreement. This sentence in the

coalition agreement, however, makes the objectives of the

government a little clearer: “the cabinet wants to put the house in

order in many sectors and restore the balance between rights and

duties” (Rijksoverheid, 2010c, p. 3 my emphasis). This statement

implies that The Netherlands, which was always viewed as a

progressive country in terms of welfare state policies, seems to be

quickly eroding the very fundamentals they were praised for and

reversing most of its accomplishments made during the twentieth

century. The difference between public-service of basic needs and

commercial provision seems to disappear as corporations and

businesses outside politics increasingly take responsibilities that

used to be in the hands of the state. Although privatisation in social

welfare democracies has a longer history (Kamerman & Kahn, 1989)

and specifically in the Dutch context (Cox, 2001; Esping-Andersen,

30 |

�1996; Pavolini & Ranci, 2008), at this time in history we are noticing

the peak of privatisation in the Netherlands at the critical juncture

of deterioration of democratic principles and the narrowing of the

public space.

In front of a canvas displaying a forced perspective, baroque,

classical Trompe-l'œil background – a much-used canvas within the

history of (Western) modern theatre - Rutte emphasised the strong

solidarity between the three parties, while also articulating the

breach between them concerning the anti-Muslim campaigning of

Wilders. Immediately upon this assertion, Rutte announced an

intensification of the integration policy by “limiting the large influx

of hopeless immigrants” (Volkskrant, 2010a), which contrasts with

the election programme of the CDA (2010), and assured more

dedication to the “protection and safety” of Dutch civilians

(Volkskrant, 2010a), which makes clear that the interests of the farright voters of the PVV had not been overlooked. As an example of

the latter, the new Prime Minister Rutte conveyed that if criminals

performed a criminal act they would be made financially

accountable for their wrongdoings; he also assured anecdotally that

“if you are ever confronted by a burglar in your house, and you give

him a few firm punches, you will not be disposed of in chains. The

burglar, however, will be” (Volkskrant, 2010a). After the speech had

ended, hands were shaken, people in the crowd smiled and nodded,

photos were taken, and subsequently, the three politicians went off

the stage.

Rutte did not question the feasibility of his legal statements

during his presentation, nor did the opposition or the press

convincingly. Neither did he disclose in which areas his party had to

give ground during the coalition negotiations, and, more

importantly, for what price. From these observations, one can

conclude that this far-reaching agreement necessitated a

performance to emphasise elements of character and to engage with

the voters emotionally, by making big yet unrealistic electoral

promises, without ever disclosing a substantive view. The

mobilization and management of images are seen as a primary mode

of governance (Glynn, 2008). These descriptions are at the heart of

the inclination towards the so-called post-democratic condition.

| 31

�2.1.3 The Catshuis deliberations

After 509 days, the Rutte I cabinet culminated at the formal

residence of the Prime Minister, the ‘Catshuis’. Following a deficit of

4.5% of the government budget, calculated again by the CPB (Nu.nl,

2012a), the coalition partners decided to negotiate new austerity

measures. During the Catshuis deliberations, no official statements

were given to the media for 47 days, and again the outside world

could only catch glimpses of the politicians through the media’s

telephoto lenses. It seemed that as an outsider, you were able to

follow what was going on in the house. Moreover, that the

politicians wanted to make it very clear to the public, by standing at

crucial moments on strategic points outside the mansion, whether or

not the negotiations were proceeding according to plan. One day

you could see pictures of heated discussions among the three

politicians on the terrace. Another day video fragments of one

politician pacing up and down in front of the house, and finally, on

the last day, the abrupt departure of Geert Wilders, while talking

erratically outside on the telephone in front of the front door,

indicating that the talks between the VVD, CDA and PVV had

ultimately faltered. After this, two separate press conferences were

given; one by the PVV, and another by the VVD alongside the CDA,

to indicate that the Catshuis deliberations, despite all efforts, had

failed. During the press conference, Rutte’s tone was confessional:

We were almost ready. (…) We had a plan of austerity reforms to

bring the state finances in order. These reforms would make the

Netherlands [economically] stronger and distribute the burden

equally. The PVV pulled back at the last moment, based on to the

consequences of an agreement we formulated in the formation a halfyear ago. (…) I can only conclude that this party lacked the political

will to carry on. For this reason, we are standing here empty-handed

(Rijksoverheid, 2012b).

Ditto Wilders:

In the end, there was a batch of austerity measures, which would

have had drastic consequences. All this to achieve a European

requirement of the three-percentage deficit in 2013. I do not accept

that the elderly have to [economically] bleed in the Netherlands. It is

unacceptable and not in the interest of our PVV voters. If less rested

on the three-percentage [deficit], if less were cut back, we could have

agreed. If I did not believe in this [agreement], I would never have

started. That is why I am genuinely disappointed. However, if it is

32 |

�not possible, then not. [Thus] new elections as soon as possible! (NOS.nl,

2012).

Given these descriptions, these events of the Dutch general election

of 2010 can be conceived of as a classical theatre play. The dramatic

structure followed more or less Gustav Freytag’s 5-act pyramid

structure (Freytag, 1863), which forms the dominant Western

dramatic flow of storytelling – although with some variations. There

was a definitive curve of exposition, where after the election results

the important players were introduced to the political arena. The

series of events leading to the support agreement at the Binnenhof

and the presentation of this support could be seen as part of the

rising action. These events build towards the point of greatest

interest or climax, namely the Catshuis deliberations following a

deficit of 4,5% of the government budget. The complications surged

during these deliberations could be seen as the falling action. And

lastly, the catastrophe of the tragedy, where the misfortune of the

tragic heroes, Rutte and Wilders were brought about by some error

of judgement.

These acts, in the theoretical framework of Erving Goffman’s

The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, come across as if a play was

performed to prove that these politicians did everything in their

position ‘backstage’ at the Catshuis to serve the interests of (some of)

the people, and that they were personally disappointed by the

negative outcome. One could say that the politicians publicly

employed ‘defensive practices’ to salvage the definition of the

situation projected by them (Goffman, 1959, p. 12). In their actions,

the three politicians made a moral appeal to the voters, by showing

their grief and frustrations, to ensure their projected-self-image (e.g.

Would the voters blame me for the failure of the Catshuis

negotiations?) remained intact. These performances called for an

audience, in this case, the voters, who can witness a pattern of

actions being performed in the ‘front’. This front, as Goffman

explains, is a setting that circumscribes a geographical location,

where, as in a theatre, the audience has to bring themselves to. And

the actors must terminate their performance when the audience

leaves this place (Goffman, 1959, p. 19). In the case of both the

Binnenhof and the Catshuis, the front was an important political

building where strategic gatherings of politicians took place, which

was more or less publicly accessible and covered by the media. What

is also striking at this point is that the performances that were

carried out by the politicians at a given point became “a collective

| 33

�representation and a fact in its own right” (Crouch, 2004, p. 24)16.

People did not ask afterwards which deals were brokered

‘backstage’ in the Catshuis, but automatically accepted what was

said at the press conference or shown in pictures and video

fragments. In other words, the idea of the theatre in this context does

not solely ‘represent’ or mirrors reality, but constitutes through

language, gesture and symbolic acts a social reality with far-reaching

consequences.

Here, an oversimplification of politics can be noted, whereby

the parties stumble over something trivial after so many weeks of

deliberation. Charismatic personalities such as Wilders and Rutte

utter a vague and incoherent set of clarifications, which reflects no

explicitly articulated concerns, except an unclearly expressed unease

by Wilders about the financial situation of the elderly (but how and

to what extent?). Alternatively, an intention by Rutte to make the

economic climate more favourable (to whom and, again, how?). Also

— and Wilders is not exceptional by asserting that the policies are

“not in the interest of the PVV voters” — a vague and broad middleclass is addressed to resolve the decline of clarity in the profile of the

electorate. This class materialises, in the case of Wilders, in the

personages of Henk and Ingrid, the conceited autochthonous white

middle-class, hard-working nuclear family, versus Mohammed and

Fatima, the allochthonous17 black and brown, presumed lazy,

criminal Other that impedes the freedom and economic

development of the former18 (see Duyvendak, 2011; Essed, 1994,

______

16

See also (Nu.nl, 2012a)

17

For a critical analysis of the terms autochtonous/allochthonous in Dutch

policy see van der Haar and Yanow 2011.

18

As an example, see a speech by Wilders during a parliamentary session:

“The multicultural society is an expensive joke. Thanks to a study of the

CPB (...) we know that an average non-Western immigrant family costs the

Dutch taxpayer 230,000 euros. That is more than one hundred billion euros

in total. (...) Think about what we could do with that money. We had been

able to give all the elderly in nursing homes their own room a year ago,

with a personal nurse. We could all have stopped working on our 50th. Or

give everyone a sailboat for free. We could have bought another country,

just for fun. We could swim in the money. But who pays the bill? Who pays

that hundred billion? Those are the People who have built the Netherlands,

the people who work hard, the people who save money and pay their taxes

34 |

�2002; Essed & Goldberg, 2002; Essed & Hoving, 2001; Mepschen,

Duyvendak, & Tonkens, 2010; Uitermark, Mepschen, &

Duyvendak, 2014; Yuval-Davis, 2011).

Arguably, it can be said that politics require a specific

performance in order to prosper. Voters should get the impression

that politicians will do their utmost to look after the best interests of

the country and the voters, even if this means an alliance with a

party with conflicting ideals. This holds true in countries with

proportional election and strong political culture of coalition

building, such as the Netherlands. In other words, politics is

theatrical in the sense that it necessitates a place where the

politicians can perform a favourable display of themselves. In this

way, voters can judge these politicians for their ‘true’ personality

and good intentions while ignoring potential flaws in the presented

policy or politicians can conceal a substantive political

argumentation, and hence making the political arena consistently a

theatrical space. However, it is not (only) the acts that politicians

perform what makes this theatricality so self-referential, but the

increasing depoliticisation and squeezing of the public sphere such

theatricality contributes to.

2.2 Why post-democracy?

The 2010 Dutch general election, the consequent formation

deliberation and the fallout of the Rutte I cabinet are exemplary

cases to discuss the issue of the Dutch inclination towards postdemocracy for several reasons: the Dutch Polder and the idea of

governmentality, the trivialisation of politics and the growing

apathy of the public.

2.2.1 The Dutch Polder Model and

the idea of governmentality

After the results of the Dutch electoral vote consistently no party is

per se excluded from a possible coalition or, in the words of the VVD

leader Mark Rutte, “the VVD does not exclude any party”

neatly. The ordinary Dutchman who does not get it. Henk and Ingrid pay

for Mohammed and Fatima.”

| 35

�(Nieuws.nl, 2014), thus allowing drastic concessions in the political

agreement to be made19. This strategy is emblematic of the Dutch

‘Polder model’. The ‘Polder model’20 is “a notion that signifies

successful tripartite cooperation and central-level dialogue between

employers’ associations, unions and the government on welfare state

reform and other relevant socio-economic matters (Hendriks, 2010,

p. 14)”. The consensus model erases the most contentious parts of a

possible agreement so that all parties can meet halfway and thus

preventing the parties to advocate significant change. This kind of

highly artificial agreement, as Rancière sharply states:

Means that whatever your personal commitments, interests, and

values may be, you perceive the same things [and] you give them the

same name. But there is no contest on what appears, on what is given

in a situation and as a situation. Consensus means that the only point

of contest lies in what has to be done as a response to the given

situation (Rancière, 2003, p. 4).

In reality, this means that progressive political parties extensively

co-operate with conservative parties in the Netherlands. Decisionmaking revolves around a consensual composition in which

everyone who is elected takes part and participates in a given and

generally accepted division of social order and spatial distribution.

While there may be conflicts of interest and opinion, there is a

general agreement in guarding the “existence of the neo-liberal

political, economic configuration” (Swyngedouw, 2011, p. 372).

Besides, successive coalitions follow similar austerity plans as their

predecessors21, and earlier enforced policy plans are hardly ever

______

19

However, during the general election of 2017 most parties including the

VVD excluded a possible collaboration with the PVV of Geert Wilders due

to his racist comments. See also footnote 26.

20

The ‘Polder model’ is very much in fashion in the Netherlands. The word

‘polder’ refers to man-made lands with elevations below sea level, which

are protected by fabricated dykes, and the term ‘Polder model’ is

commonly used to imply an artificial consensus-based decision-making in

the Netherlands.

21

Many policy plans are implemented over a longer period, the succeeding

government is then not willing or able to change them. A good example is

the culture budget cuts introduced by the Rutte I cabinet, which was

adopted wholescale by the Rutte II cabinet.

36 |

�revoked, despite countless pledges made during electoral

campaigns (see for example, Nu.nl, 2012b).

Although this consensus ideal gives the impression of a noble

and fair achievement, it is anything but democratic. That is, in this

construction, alternative viewpoints are automatically dismissed

from the political arena to accommodate the needs of the mass while

conserving the current state of affairs. This results in fabricated and

arranged deals between conflicting parties by not remaining

intransigent on the very issues these parties campaigned for.

“Agonistic debate”, as Erik Swyngedouw discuss, “is increasingly

replaced by disputes over the mobilization of a series of new

governmental technologies, managerial dispositifs and institutional

forms, articulated around reflexive risk-calculation (self-assessment),

accountancy

rules

and

accountancy

based

disciplining,

quantification and benchmarking of performance (Swyngedouw,

2011, p. 372)”. Substansive arguments are eschewed for the

measurement of performance “in terms of success, accomplishment,

growth, reputation, or inversely, non-performance, failure, collapse

and inadequacy (…) [and] the fulfillment of a goal or the failure to

do so (Bala, 2013, p. 15) - a point I will return to below.

Also, the Netherlands Bureau of Economic Policy Analysis

(CPB) now seems to have a much larger role than an advisory body.

That there had to be budget cuts indicated by the CPB was clear. The

only point of contestation among the political parties was what

should be cut and how this was to be done. It is interesting to note

that the government did not legitimise the necessity of the Catshuis

deliberation by referring to a political ideology, but by citing

external or seemingly non-political factors indicated by the CPB.

Pascal Gielen explains that “[i]n such a framework politicians give

the impression of being ‘forced’ to take certain decisions, while

relegating their ideological and active freedom of choice to the

background” (Gielen, 2011).

Moreover, politicians, as political scientist Colin Hay argues,

increasingly accept as a fact that economic freedom in a globalized

era is of the utmost concern, instead of taking care of the demands of

citizens (Hay, 2007).

2.2.2 The trivialisation of politics: is it the media?

Second, it seems that contemporary politicians rarely aspire to any

complexity of an argument, allowing the political debate to be overly

| 37

�trivialised: “very brief messages, requiring extremely low

concentration spans; the use of words to form high-impact images

instead of arguments appealing to the intellect” (Crouch, 2004, p.

26). Little space is available for political and ideational reasoning’s,

except perhaps a nationalistic and racist discourse of which Wilders

is an exemplary case. The way in which the underlying objective of

the coalition agreement of the Rutte I cabinet was presented and the

justification for the Catshuis deliberations were unnecessarily

simplified. Indicative of this, is the intention uttered by Rutte at the

failed Catshuis deliberations to “make the Netherlands

[economically] stronger” without thoroughly explaining which

policies needs to be implemented, which social programs cut-back

and who will benefit from these policies.

One could attribute the ills of democracy and the

trivialisation of politics to the mass media, namely, how we see and

experience politics are mediatised through the various press, radio

and TV media. These media outlets, as noted by Crouch, frame

political relevant communications,

On a certain form of the idea of a marketable product. (…) This

prioritises extreme simplification and sensationalization, which in

turn degrades the quality of political discussion and reduce the

competence of citizens. (…) Political actors themselves are then

forced into the same mode if they are to retain some control over

how they formulate their own utterances: if they do not adopt the

style of rapid, eye-catching banality, journalists will completely

rewrite the message (Crouch, 2004, pp. 46–47).

“The power of a politically highly relevant group of corporations –

those in the media industry”, Crouch continues, “is in fact involved

directly in reductions of choice and the debasement of political

language and communication which are important components of

the poor health of democracy” (Crouch, 2004, p. 46). Arguably, these

statements implicate a gradual aestheticisation of politics.

This notion of the aestheticisation of politics can directly be

attributed to Walter Benjamin in his essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age

of Mechanical Reproduction’ (1969). Here Benjamin links, at a time

where Adolf Hitler briefly came to power, cultural mass production

with the aestheticisation of politics and fascism. Fascism, Benjamin

contends, “attempts to organise the newly proletarianized masses

while leaving intact the property relations which they strive to

abolish. It sees its salvation in granting expression to the masses –

but on no account granting them rights (Benjamin, 1969, p. 41)”. The

38 |

�extensive attention the Catshuis deliberations received was not

possible without the mass media. The coverage, a reproduction of

the event itself, can be infinitely reproduced and re-transmitted

endlessly and has become the authority of the event in itself. Mass

movements and rallies “are more clearly apprehended by the

camera than by the eye. (…) [Since] the image formed by the eye

cannot be enlarged in the same way as a photograph” (Benjamin,

1969, p. 54). How we see and experience politics is generally only

through various printed, radio and TV media. The media makes

these events accessible to us.

Similar to the days of Walter Benjamin where a connection

could be made between the media, the mass and emerging fascism,

populist nationalism can, nowadays, according to Gielen, replace

fascism (Gielen, 2013, p. 82). As media magnates and famous TV

stars in such societies have every opportunity in positions of

political power to dictate what is seen and unseen within the visible.

In Gielen’s argument, in a time of a growing emphasis on image and

the value of media to convey information, the media is decisive in

the formation of the post-democratic state we live in. The growing