Do rituals promote social cohesion?

Dimitris Xygalatas

Department of Anthropology, University of Connecticut, USA

Introduction

Rituals are strange – if not to those who enact them, certainly to outsiders. They involve

large expenditures of time, effort, and resources but offer no obvious benefits and often

have no apparent purpose. (Think of all the extravagant rituals of the British monarchy

that seem utterly comical to any foreigner.) But there is strange, and then there is

dangerous: Some rituals can involve high levels of stress, effort, and pain, and pose

serious risks for their practitioners. Examples of such extreme rituals include being stung

by a swarm of venomous bullet ants, getting nailed on a cross, and walking on fire. Given

such high costs, the prevalence of those practices around the world and throughout

history constitutes an evolutionary puzzle (Xygalatas 2012).

Based on ethnographic observations (the human activities and relationships

anthropologists observe in the field), various scholars have argued that the answer to this

puzzle lies in the social functions of these rituals. Specifically, the reason such behaviors

survive despite the risks they involve is that they contribute to social cohesion, that is,

they strengthen the bonds between community members by producing emotional

alignment (shared emotions), fostering collective identities, and promoting solidarity

(Atran and Henrich 2010; Sosis 2003). For example, sociologist Emile Durkheim (1915)

described a phenomenon he called “collective effervescence”: an ecstatic feeling of

togetherness, which is experienced by participants of high-arousal rituals and makes

them feel one with the group. My colleagues and I investigated this phenomenon by

measuring heart-rate activity among performers and spectators of a fire-walking ritual in

Spain (Konvalinka et al. 2011). Our measurements revealed the physiological markers of

collective effervescence, showing that people’s heart rates were synchronized during the

ritual, irrespective of their physical activity, and that this extended not only to active

1

�performers but even to local spectators. My ethnographic research in the village

suggested that this physiological alignment was also felt at the level of subjective

experience: Participants reported that during the ritual they felt that they became one with

the crowd, and this event changed their relationship with other participants, bringing them

closer together.

Nonetheless, there is still a gap between these phenomenological reports (related

to participants’ own lived experience), and our physiological measurements. If ritual

intensity really contributes to social cohesion, then we should be able to see the effects

of participation at the behavioral level. But how can we measure a vague concept like

social cohesion? The answer to this question depends on what is theoretically interesting

as well as feasible in a real-life setting. Anthropologists can convey a sense of this

cohesion by looking at everyday interactions between participants, but such anecdotal

evidence is highly subjective and is hard to systematize and quantify. Taking a more

quantitative perspective, one could use surveys, for example asking participants to rate

how close they feel to their peers or to the group as a whole. The problem with this

approach is that self-reports are often poor indicators of actual behavior, as they are

plagued by various biases and serious limitations in individuals’ awareness and

introspective abilities (Xygalatas & Martin 2016). In addition, self-reports are particularly

problematic when they relate to traits and behaviors that are regarded as positive or

desirable, because people are more likely to exaggerate these desirable traits (which is

why this problem is known as “social desirability bias” (Fisher 1993). Alternatively, one

could try to measure specific aspects of those interactions, such as how often people

touch one another or how frequently they visit their peers after performing the ritual

together. However, in the context of a collective ritual that can involve hundreds or

thousands of participants, the logistics of such an undertaking would probably be

unmanageable.

And then there is the issue of ritual intensity: Since we are interested in examining

the effects of extreme rituals, we need a measure of this extremity, which is our

independent variable (the thing that we expect to be the cause of something else). In an

ideal world, we would be able to manipulate this variable by randomly assigning people

2

�to varying degrees of ritual intensity. This is what Elliott Aronson and Judson Mills (1959)

did in a study where they asked college women to take a test in order to be admitted to a

reading group. In the severe condition, the test required participants to read out a series

of sex-related, obscene words, which were aimed to provoke embarrassment. In the mild

condition, participants read a series of words that were not obscene, and in the control

condition, there was no test. After they joined the group, researchers asked the women

how interesting they found the group’s discussion sessions (which were the same for all

conditions). Those participants who went through the embarrassing initiation reported

liking the group more.

At the time, Aronson and Mills’ study made a seminal contribution to social

psychology. However, it lacked what we call ecological validity, i.e., the ability to make

reasonable generalizations about real-life situations based on what was observed in the

laboratory. The experiment was conducted among college students, who went through

an artificial task that was neither framed nor perceived as a ritual, in order to join a group

of little or no personal importance to them. Moreover, the embarrassment task did not

even come close to the kinds of costs involved in real-world, high-intensity rituals.

In fact, such rituals could never be studied in a laboratory setting, for a variety of

ethical as well as practical reasons. For example, an institutional review board (a

university committee that oversees the ethical treatment of participants in research) would

never allow an experimenter to subject people to some of the excruciating ordeals found

in some hazing or initiation rites. But even if they did, and even if researchers managed

to convince people to participate in such a study, these activities would be meaningless

outside of their natural context. An important factor underlying the prosocial effects of

ritual is the fact that all participants regard the actions involved as sacred. Indeed, in our

study of the Spanish fire-walking ritual, we found that the emotional alignment brought

about by the ceremony extended only to locals (including both performers and spectators

of the ritual), who shared the same cultural background as the fire-walkers. The outsiders

who came to watch the ritual as curious tourists did not experience this emotional

alignment (Xygalatas et al. 2011).

These limitations, however, do not mean that we have to give up. In fact, there are

3

�many scientific areas where true experiments (involving a manipulation and random

assignment) are often practically impossible (think of astronomy) or ethically

unacceptable (think of epidemiology), but those areas apply rigorous scientific methods

nonetheless (Diamond and Robinson 2012). The scientific process consists in systematic

observation that leads to the formulation and examination of testable hypotheses about

cause-and-effect relationships between variables. This can be done both in the laboratory

and in a more natural setting. But while in the laboratory the experimenters manipulate

the variables of interest, in a naturalistic experiment (also known as a quasi-experiment)

these variables occur “in the wild.” Thus, instead of taking the phenomena or people we

wish to study out of their natural context and moving them into a lab, we take the lab into

context by moving it into the field (Xygalatas 2013).

Setting

In order to test the effects of ritual intensity on prosociality, I needed to find some really

extreme rituals. There are many such rituals in the world, but few are as intense and at

the same time as widespread as the Thaipusam Kavadi. This ritual is performed by

millions of Tamil Hindus in India and around the globe in honor of Lord Murugan, the

Hindu god of war, also known as Kartikeya. The Thaipusam festival involves a ten-day

period of fasting and prayer that culminates with the kavadi ceremony, which involves

piercing the body with sharp metallic objects. Although women do not engage in the

extreme forms of this ritual (they either have a single piercing or just a scarf around their

mouth), men can have hundreds of piercings throughout their body, ranging from needles

and hooks from which they hang lime fruit to skewers and rods the size of broomsticks

pierced through their cheeks. These rods are often so long and heavy that the bearer has

to support them with both hands to prevent tearing of the face. Once these piercings are

in place, devotees embark on a several-hour-long procession to the temple of Murugan,

each carrying a kavadi attam. The kavadi is a large structure made of bamboo, wood, or

metal and decorated with flowers and peacock feathers. It can weigh over 40 kilograms

(almost 90 pounds) and is carried on the pilgrims’ shoulders throughout the entire

procession (the word kavadi in Tamil literally means “burden”). Some devotees walk on

4

�shoes made of nails; the rest walk barefoot, which can be terribly painful because this

ritual is typically performed in tropical places, where the sun makes the asphalt scorching

hot. In addition to all this, some practitioners drag enormous chariots the size of minivans,

using chains that are attached to their skin by hooks. To make matters worse, temples of

Murugan are traditionally built on hilltops, which means that pilgrims have to carry their

kavadi all the way to the top of the hill, where they can finally have their piercings

removed. During the entire procession, they are not allowed to drink, eat, or speak, and

they never put their burden down. Clearly, this is a very intense ritual, and in order to

study it, I decided to go to Mauritius.

Mauritius is a tiny island nation in the middle of the Indian Ocean. Although it was

one of the last places in the world to be inhabited by humans, it is one of the most diverse

societies in the world and home to a great variety of religious traditions (Xygalatas et al.

2016). Participation in the kavadi is massive in Mauritius, not just by Tamils but by all

Hindus and even by members of other religious groups. The ceremony is organized by

hundreds of temples all over the island, some of which draw thousands of participants.

This was exactly the kind of context I was looking for.

Methodology

Before conducting a field experiment, one must become familiar with the local culture and

establish a social network of connections with participants, local assistants, and

gatekeepers (key local contacts who are in position to provide or facilitate access to

informants). And the only way to do this is by conducting ethnographic fieldwork, that is,

by living with the local community, participating in people’s everyday lives, and observing

their customs and behaviors. This is a very time-consuming, demanding, often frustrating,

but ultimately extremely rewarding process. In this case, it took me almost two years of

fieldwork and preparation before I was able to run this experiment. Moreover, field

experiments such as this one involve the combination of various methods and skills, as

well as a lot of labor, which means that a single researcher cannot easily conduct this

kind of study. For this specific study, I brought together an interdisciplinary team

consisting of experts in religious studies, anthropology, psychology, statistics, and

5

�computer coding, as well as a group of local research assistants.

We designed a field experiment (Xygalatas et al. 2013) with the goal of testing two

hypotheses. First, based on previous empirical and theoretical work on the communal

effects of rituals ( Konvalinka et al. 2011; Norenzayan & Shariff 2008; Sosis & Ruffle

2003), we hypothesized that ritual intensity would increase prosocial behavior for the

entire community. And second, based on psychological studies of social identification

(Tajfel, Billig, & Bundy 2005; Festinger 1962) and evolutionary theories of parochial

altruism (directed preferentially towards members of one’s group) (Choi & Bowles 2007;

Ginges, Hansen, & Norenzayan 2009), we hypothesized that ritual intensity would

increase participants’ affiliation with their religious subgroup at the expense of more

inclusive superordinate (larger, more inclusive) identities.

In a field setting, we cannot always manipulate our key variables, so we need to

find situations where these variables occur naturally (which is why this is also called a

naturalistic study). The kavadi ritual in the town of Quatre Bornes provided ideal situations

for this study. Within the span of a few days (i.e., during the Thaipusam festival), the same

people perform two dramatically different types of rituals at the same place, in the context

of the same festival: a low-intensity collective prayer that involves three hours of chanting

and singing, and the high-intensity kavadi ordeal that involves all the painful activities

described above. Moreover, there are many devotees who take part in the high-intensity

ritual without engaging in any of the painful activities: They do not have any piercings,

they do not carry a burden, and they do not walk barefooted or on nails – they simply

accompany the procession as pilgrims. Thus, this setting provided three naturally

occurring conditions: a low-ordeal group, a group of high-ordeal performers, and a group

of high-ordeal observers.

6

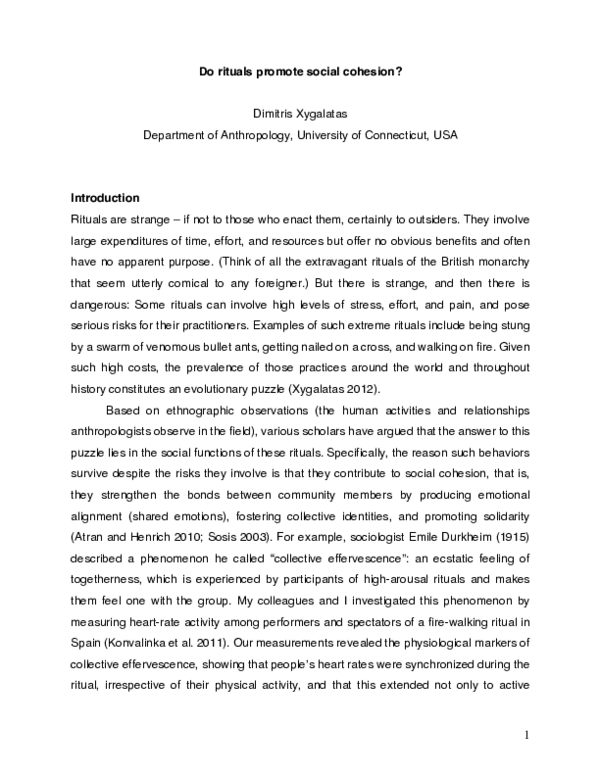

�Image 1: A “high-ordeal performer” accompanied by “high-ordeal observers” during the ritual.

Image 2: In addition to carrying the kavadi, many participants also drag chariots by chains

attached to their skin by hooks.

7

�During the festival, we recruited eighty-six men (that is because, as you will

remember, only men engage in the extreme forms of the ritual). Specifically, we tested

thirty-five participants after the “low-ordeal” collective prayer and fifty-one participants

after the “high-ordeal” kavadi ritual, including people who had performed the painful

ordeal and others who had merely observed it. All of our participants were members of

the same Hindu community, lived in the same neighbourhood, worshipped the same

gods, and attended the same temple. Importantly, the people in our sample took part in

both rituals, and even the observers had participated as performers in the past. This

allowed us to make a reasonable assumption that any behavioral differences observed

between these groups as they went through each ritual would be due to the nature of the

ritual actions involved and not due to self-selection bias, that is, due to pre-existing

differences in participants’ personalities.

Immediately after each ritual, our local assistants approached participants and

invited them to enter a room near the temple, where they were presented with a short

questionnaire (written in the local Creole language) that we used to collect demographic

information, ratings of the perceived painfulness of the ritual experience, and reports on

social identity. Our design involved a comparison between people’s identification with a

more exclusive, parochial religious group (Mauritian Hindus) and a more inclusive,

superordinate national identity (Mauritians). Although my ethnographic work suggested

that these two identities were not binary (people felt both Hindu and Mauritian, not one or

the other), we were interested in seeing how the intensity of religious rituals, which are

meaningful reminders of the more parochial affiliation, might affect the dynamic overlap

between these two social identities. For this reason, our questionnaires used continuous

sliding scales on a screen, which were anchored by one of these identities at each end.

In other words, imagine a straight line ranging from “Hindu” to “Mauritian”, where

participants can choose which exact point on the line best represents how they feel. This

allowed us to see under what circumstances people viewed themselves as being more

Hindu or more Mauritian. Using the same type of question, participants also reported on

their views of the other main ethno-religious groups on the island, so that we could see

8

�how ritual participation would affect attitudes towards religious outgroups such as

Christians and Muslims.

Pain is a subjective sensation, so self-reported measures are the best way to

assess it. The same goes for social identity, which is an intangible and subjective concept.

However, as we mentioned, self-reports of prosociality are not reliable, so it is best to look

at people’s real behaviors. But what kinds of behaviors? In other words, we needed to

operationalize prosocial behavior, that is, to define this phenomenon in terms of a specific

manifestation that could be measured precisely. Although there are numerous ways of

assessing nonverbal behavior (Manusov 2005), one of the most common paradigms in

the study of prosociality focuses on economic interactions, because they involve actual

monetary costs that are salient to the participants, forcing them, quite literally, to put their

money where their mouth is. However, one problem with economic experiments is that

they often feel alien to participants because they do not resemble real-life economic

exchanges. To deal with this problem, we looked at how much money people chose to

donate to a charity, a task that was familiar and felt natural to our participants. And to

avoid demand characteristics (participants changing their behavior when they know that

they are taking part in an experiment), we presented the task outside of the context of the

experiment.

After they answered our questionnaire, we paid participants 200 Mauritian rupees

(a substantial amount) as compensation for taking part in the study and thanked them for

their participation. However, as they exited the room, a confederate (an actor who is

actually part of the experiment) informed them of a local charity and asked them if they

would like to make a contribution from their earnings. If they agreed, they were shown a

private booth where they could make their contribution. This was done to ensure

anonymity, because people behave differently when they know that their behavior is

publicly accessible. To facilitate a variety of choices in the amount people would donate,

we had made their payments in ten coins of 20 rupees each, which provided them with a

behavioral scale of 1-10 right in their pocket.

The need to observe anonymous behavior raised both ethical and practical

problems. How could we record people’s choices without compromising their anonymity,

9

�which was crucial to our design? To solve this problem, we used a system of marked

envelopes that the confederate handed to each participant for their donation. The

envelopes contained a hidden serial number, which could be linked to participants’

answers to the questionnaire without revealing their name. In fact, we never recorded

their names, so we could not trace their personal data even if we wanted to.

This design allowed us to compare a high-arousal ritual with a low-arousal one.

But to get a more complete understanding of the relationship between ritual intensity and

prosociality, we would also need a control group. For this reason, we returned to the same

location several months later and collected data from a different group of fifty locals

outside of the context of the ritual. This allowed us to get a baseline measurement of

prosociality within that community.

Results

Our first prediction was that the painful ritual would incite more prosocial behaviors among

all attendants, irrespective of their role. Our results confirmed this prediction. After taking

part in the “low-ordeal” collective prayer, participants donated an average of 81 rupees.

On the other hand, after attending the “high-ordeal” kavadi ritual, people on average

donated 151 rupees – a difference that was highly significant. But when we compared

performers to observers of that ritual, there was no significant difference between the

groups. In other words, everyone who took part in the high-intensity ritual was more

generous. As for the control group, they donated an average of 52 rupees, which was

significantly lower than even the low-intensity ritual. To examine the effects of ritual

intensity more closely, we looked at the relationship between pain and donations. We

found that there was a positive correlation between the two variables, meaning that the

more participants suffered during the ritual, the more money they donated to the charity.

Taken together, these findings suggest that a) collective rituals can have positive effects

on generosity; b) those effects are amplified by ritual intensity; and c) they can extend to

the entire community.

Our second prediction was that the painful ritual would have an effect on social

identification, resulting in stronger identification with the religious ingroup at the expense

10

�of more inclusive social identities. However, the results suggested a more interesting

story. Specifically, we found that higher pain drove people to identify more with the

inclusive Mauritian identity. Similarly, we found that those who took part in the painful

ritual saw not only themselves but also other religious groups, i.e. Christians and Muslims,

as being more Mauritian. These results suggest that participation in the high-intensity

ritual led to an expansion of the prosocial circle for this community.

Image 3: Both performers and spectators of the high-ordeal ritual were significantly more

generous compared to participants in the low-ordeal ritual, who in turn were more generous

than the people who took part in no ritual (the control group).

Discussion

The results of our field experiment provide support for long-standing theories on the role

and function of extreme rituals. Specifically, we found that ritual intensity increased

prosocial behaviors and attitudes, an effect which applied to the entire community, that

11

�is, not only for those who underwent the painful ordeal but also for spectators of the event.

In contrast, people’s self-reported religiosity had no bearing on generosity. This confirms

research in the cognitive science of religion suggesting that religious prosociality is a

matter of situational factors (circumstances) rather than dispositional ones (personality)

(Shariff and Norenzayan 2007; Xygalatas and Martin 2016).

In addition, we saw that ritual intensity led participants to identify with a more

inclusive social identity and to see other social groups as being closer to that overarching

identity as well. In a different context, the ritual practices of a group might increase ingroup

cohesion at the expense of the outgroup, i.e., might serve to mark this group as distinct

from and superior to others. However, in the Mauritian context, the Thaipusam kavadi is

celebrated on a national scale and is frequently attended by members of other ethnoreligious groups, who co-exist in a relatively non-confrontational way (Xygalatas et al.

2017). In this context, this ritual serves as a celebration of Mauritian-ness, affirming the

inclusive nature of the superordinate Mauritian national identity (Gaertner et al. 1999;

Hornsey & Hogg 2000; Clingingsmith, Khwaja, & Kremer 2009). Once again, we are

reminded that human cognition and behavior are always situated (embedded) within

specific socio-cultural contexts, and we must take these contexts into account when

designing, conducting, and interpreting our studies (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan 2010).

However, each individual study only adds a single piece to the puzzle. Science is

a cumulative process, which means that in order to solve the puzzle of extreme rituals we

need to look at multiple lines of evidence. For example, although our study was the first

to quantify the prosocial effects of ritual intensity in a real-life ritual, it did not address the

question of how these effects come about, i.e., the specific mechanisms that drive the

effects. To answer this question, we can turn to other relevant findings from the disciplines

of psychology and anthropology.

One obvious feature of extreme rituals is that they involve a lot of effort and pain.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that the higher the cost of an activity, the more

meaningful and important it feels to its practitioners (Festinger 1962; Bem 1967; Norton,

Ariely, & Mochon 2012). And when this activity is performed in a collective context, then

this meaningfulness is extended to the entire group, leading to increased liking for fellow

12

�participants (Aronson & Mills 1959; Gerard & Mathewson 1966). Similarly, research on

pain also shows that suffering can increase prosocial behavior (Olivola & Shafir 2011)

and sharing dysphoric (unpleasant) experiences can lead to increased cooperation

(Bastian, Jetten, & Ferris 2014). This can happen via the alignment of empathic

responses among ritual participants (Konvalinka et al. 2011; Xygalatas et al. 2011), the

formation of shared memories and narratives about their common experience

(Whitehouse 1992; Xygalatas & Schjoedt 2013; Schjoedt et al. 2013), and the activation

of powerful collective identities produced by this shared experience (Whitehouse &

Lanman 2014).

At the same time, performing a strenuous ordeal can signal commitment to the

community’s norms and values (Henrich 2009), because only those who are really serious

about their group membership would pay such a high cost to partake in the community’s

traditions. This is known as the costly signaling theory (Sosis 2000), and it has received

empirical support from anthropological studies. For example, those who pay higher ritual

costs enjoy reputational and cooperative benefits (Sosis & Ruffle 2003; Power 2017a;

Power 2017b) within their communities, and religious groups that have costlier ritual

requirements have better survival rates, i.e., are less likely to dissolve (Sosis & Bressler

2003).

Finally, extreme rituals might produce beneficial effects at the individual level. Such

rituals are often believed to have healing powers, and there might well be some healthrelated benefits to participation, whether these function merely as placebos or are the

products of such things as physical activity and socialization (Snodgrass, Most, &

Upadhyay 2017; Tewari et al. 2012). In addition, research suggests that despite the

suffering involved, the neurochemical effects of prolonged pain and exertion may bring

about feelings of bliss and euphoria (Fischer et al. 2014).

Extreme rituals have always puzzled scholars of religion, leading to fascinating

descriptions and speculations about their functions. These scholars proposed insightful

theories to explain the existence and persistence of those rituals, arguing that they play

an important role in boosting social cohesion and maintaining social order. However, they

lacked the proper scientific tools to put them to the test. Recent developments in research

13

�areas like the cognitive science of religion are now providing these tools by using new

interdisciplinary methods to shed fresh light on these age-old questions.

14

�References

Aronson, E, & Mills, J. (1959). The effect of severity of initiation on liking for a group.

Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology 59 (2): 177–81.

Atran, S. & Henrich, J. (2010). The evolution of religion: How cognitive by-products,

adaptive learning heuristics, ritual displays, and group competition generate deep

commitments to prosocial religions. Biological Theory 5 (1): 18–30.

Bastian, B., Jetten, J., & Ferris, L.J. (2014). Pain as social glue: Shared pain increases

cooperation.

Psychological

Science,

September.

SAGE

Publications,

0956797614545886. doi:10.1177/0956797614545886.

Bem, D.J. (1967). Self-perception: An alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance

phenomena. Psychological Review 74 (3): 183–200.

Choi, J. K., & Bowles, S. (2007). The coevolution of parochial altruism and war. Science

(New York, NY) 318 (5850). American Association for the Advancement of Science:

636–40. doi:10.1126/science.1144237.

Clingingsmith, D., Khwaja, A. I. & Kremer, M. (2009). Estimating the impact of the Hajj:

Religion and tolerance in Islam's global gathering.” The Quarterly Journal of

Economics 124 (3). Oxford University Press: 1133–70.

Diamond, J. & Robinson, J.A. (2012). Natural experiments of history. Harvard University

Press.

Durkheim, É. (1915). The elementary forms of the religious life. George Allen & Unwin.

Festinger, L. (1962). A theory of cognitive dissonance. Stanford University Press.

Fischer, R., Xygalatas, D., Mitkidis, P., Reddish, P., Tok, P., Konvalinka, I., & Bulbulia, J.

(2014). The fire-walker’s high: Affect and physiological responses in an extreme

collective ritual. Edited by B. Bastian. PLoS ONE 9 (2). Public Library of Science:

e88355. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0088355.

Fisher, R. J. (1993). Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. Journal

of Consumer Research 20 (2): 303–15. doi:10.1086/209351.

Gaertner, S.L., Dovidio, J.F., Rust, M.C., Nier, J.A., Banker, B.S., Ward, C.M., Mottola,

G.R. & Houlette, M. (1999). Reducing intergroup bias: Elements of intergroup

15

�cooperation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76 (3): 388–402.

Gerard, H.B. & Mathewson, G.C. (1966). The effects of severity of initiation on liking for

a group: A replication* 1. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 2 (3): 278–87.

Ginges, J., Hansen, I. & Norenzayan, A. (2009). Religion and support for suicide attacks.

Psychological Science 20 (2). SAGE Publications: 224–30.

Henrich, J. (2009). The evolution of costly displays, cooperation and religion: Credibility

enhancing displays and their implications for cultural evolution. Evolution and Human

Behavior 30 (4). Elsevier Inc.: 244–60. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2009.03.005.

Henrich, J., Heine, S.J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world?.

Behavioral and Brain Sciences 33 (2-3): 61–83. doi:10.1017/S0140525X0999152X.

Hornsey, M. & Hogg, M. (2000). Assimilation and diversity: An integrative model of

subgroup relations. Personality and Social Psychology Review 4 (2): 143–56.

doi:10.1207/S15327957PSPR0402_03.

Konvalinka, I., Xygalatas, D., Bulbulia, J., Schjoedt, U., Jegindø, E-M. E., Wallot, S., Van

Orden, G., & Roepstorff, A. (2011). Synchronized arousal between performers and

related spectators in a fire-walking ritual. Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences

of

the

United

States

of

America

108

(20):

8514–19.

doi:10.1073/pnas.1016955108.

Manusov, V.L. (2005). The sourcebook of nonverbal measures: Going beyond words.

New York: Routledge.

Norenzayan, A. & Shariff, A.F. (2008). The origin and evolution of religious prosociality.

Science (New York, NY) 322: 58–62.

Norton, M.I., Ariely, D., & Mochon, D. (2012). The IKEA effect: When labor leads to love.

Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22 (3): 453–60.

Olivola, C. Y. & Shafir, E. (2011). The martyrdom effect: When pain and effort increase

prosocial contributions. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 26 (1): 91–105.

doi:10.1002/bdm.767.

Power, E. A. (2017a). Discerning devotion: Testing the signaling theory of religion.

Evolution

and

Human

Behavior

38

(1).

Elsevier

Inc.:

82–91.

doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2016.07.003.

16

�Power, E. A. (2017b). Social support networks and religiosity in rural South India. Nature

Human Behavior 1 (3). Macmillan Publishers Limited, part of Springer Nature.: 1–6.

Schjoedt, U., Sørensen, J., Nielbo, K.L., Xygalatas, D., Mitkidis, P., & Bulbulia, J. (2013).

Cognitive resource depletion in religious interactions. Religion, Brain & Behavior 3 (1):

39–55. doi:10.1080/2153599X.2012.736714.

Shariff, A. F. and Norenzayan, A. (2007). God is watching you. Psychological Science 18

(9): 803–9.

Snodgrass, J. G., Most, D.E. & Upadhyay, C. (2017). Religious ritual is good medicine for

indigenous Indian conservation refugees: Implications for global mental health.

Current Anthropology, March, 000–000. doi:10.1086/691212.

Sosis, R. (2000). Costly signaling and torch fishing on Ifaluk Atoll. Evolution and Human

Behavior 21 (4): 223–44.

Sosis, R. (2003). Why aren’t we all Hutterites? Human Nature 14 (2): 91–127.

Sosis, R. & Ruffle, B.J. (2003). Religious ritual and cooperation: Testing for a relationship

on Israeli religious and secular kibbutzim. Current Anthropology 44 (5): 713–22.

Sosis, R. & Bressler, E.R. (2003). Cooperation and commune longevity: A test of the

costly signaling theory of religion. Cross-Cultural Research 37 (2): 211.

Tajfel, H., Billig, M.G. & Bundy, R.P. (2005). Social categorization and intergroup

behavior. European Journal of Social Psychology 1 (2): 149–78.

Tewari, S., Khan, S., Hopkins, N., Srinivasan, N., & Reicher, S. (2012). Participation in

mass gatherings can benefit well-being: Longitudinal and control data from a North

Indian Hindu pilgrimage event. Ed. by P. Holme. PLoS ONE 7 (10): e47291.

doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0047291.t001.

Whitehouse, H. (1992). Memorable religions: Transmission, codification and change in

divergent Melanesian contexts. Man 27 (4): 777–97.

Whitehouse, H. & Lanman, J.A. (2014). The ties that bind us. Current Anthropology 55

(6): 674–95. doi:10.1086/678698.

Xygalatas, D. & Martin, L. (2016). Prosociality and religion. Mental Religion.

Xygalatas, D. & Schjoedt, U. (2013). Autobiographical memory in a fire-walking ritual.

Journal of Cognition and Culture 13: 1–16. doi:10.1163/15685373-12342081.

17

�Xygalatas, D. (2012). The burning saints. London: Equinox.

Xygalatas, D. (2013). Přenos laboratoře do terénu: Využití smíšených metod během

terénního studia náboženství. Sociální Studia 10 (2): 15–25.

Xygalatas, D., Klocová, E.K., Cigán, J., Kundt, R., Maňo, P., Kotherová, S., Mitkidis, P.,

et al. (2016). Location, location, location: Effects of cross- religious primes on

prosocial behavior. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion 26 (4).

Routledge: 304–19. doi:10.1080/10508619.2015.1097287.

Xygalatas, D., Konvalinka, I., Roepstorff, A., and Bulbulia, J. (2011). Quantifying collective

effervescence heart-rate dynamics at a fire-walking ritual. Communicative &

Integrative Biology 4 (6): 735–38.

Xygalatas, D., Mitkidis, P., Fischer, R., Reddish, P., Skewes, J., Geertz, A.W., Roepstorff,

A., & Bulbulia, J. (2013). Extreme rituals promote prosociality. Psychological Science

24 (8): 1602–5. doi:10.1177/0956797612472910.

Xygalatas, D., Kotherová, S., Maňo, P., Kundt, R., Cigán, J., Klocová, E.K., and Lang, M.

(2017). Big gods in small places: The random allocation game in Mauritius. Religion,

Brain & Behavior 10 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1080/2153599X.2016.1267033.

18

�

Dimitris Xygalatas

Dimitris Xygalatas