Fields of Fire:

Researching and Modeling Peleliu’s

WWII Invasion Beaches

Toni L. Carrell, Madeline J. Roth, Jennifer F. McKinnon

2020

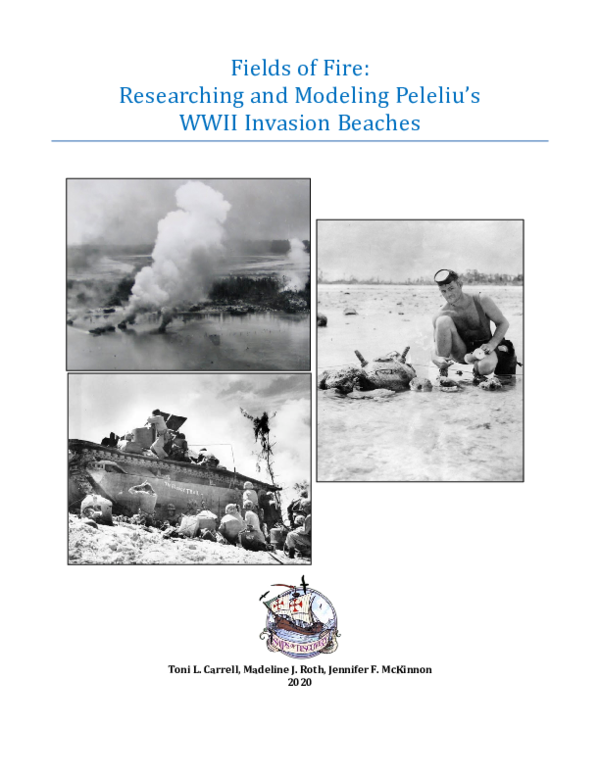

�Historic photographs clockwise from upper left: NARA RG-127; U.S. Navy Seal Museum; Hatch Collection,

National Museum of the Pacific War

�Fields of Fire:

Researching and Modeling Peleliu’s

WWII Invasion Beaches

Grant Agreement No. GA-2287-17-015

Final Report

Toni L. Carrell, Madeline J. Roth, Jennifer F. McKinnon

2020

This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions,

findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the

views of the Department of the Interior.

Obtain copies from

Department of the Interior, National Park Service

American Battlefield Protection Program

1849 C Street, NW, Room 7228

Washington, DC 20240

�Portion of a 1944 Japanese Defensive Plan showing fields of fire. Beleliu Museum

�Executive Summary

The focus of this project is the World War II (WWII) Battle of Peleliu that began on September

12, 1944 in the Palau Islands in the Caroline Island archipelago. The scope of the project is

limited to the Peleliu invasion beaches, designated as White 1, White 2, Orange 1, Orange 2,

and Orange 3, to approximately 30 meters (100 ft.) inland. Seaward, it includes the lagoon, the

reef, and the immediate area just beyond the reef.

This project is the first effort to study the Peleliu WWII invasion beaches and the offshore

battlespace. It is a Phase I historical and archival research effort and follows guidelines for

identification activities as defined by the Secretary of Interior Standards for Archeology and

Historic Preservation. The methodology focused on the results from prior archaeological

investigations, archival background research, primary and secondary accounts of the battle,

historic maps, photographs, a battlefield visit, and reconnaissance survey.

KOCOA battlefield analysis is used to understand the activities that influenced the invasion and

the decisions and limitations imposed by the natural terrain and built environment upon the

amphibious landing and the invasion beaches.

The impacts of post-war scrap salvage have been so great as to dramatically influence the

survivability of the underwater cultural heritage (UCH) of the submerged battlefield. As a result,

only a limited number of UCH sites were located.

Based upon prior archaeological investigations, historical accounts, invasion and post-invasion

land modifications to the project area, the KOCOA analysis, and the results of a site visit and

reconnaissance survey, this report assesses the cultural heritage sites that remain.

iii

�Table of Contents

Executive Summary.........................................................................................................................iii

Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................iv

List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. vii

List of Tables ................................................................................................................................... xi

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations ............................................................................................... xi

Acknowledgements....................................................................................................................... xiii

Chapter 1: Introduction ................................................................................................................ 14

Introduction............................................................................................................................... 14

Methodology, Limitations ..................................................................................................... 14

Legislation and Jurisdiction.................................................................................................... 15

Chapter 2: Previous Research, Archival Resources, Repositories ................................................ 16

Previous Research ..................................................................................................................... 16

Archival Resources and Repositories Consulted ....................................................................... 18

Chapter 3: Historical Background 1911-1945 ............................................................................... 21

The Palau Islands 1911-1941..................................................................................................... 21

The Palau Islands in WWII, 1941-1945...................................................................................... 24

Pre-Assault Air Operations and Reconnaissance................................................................... 26

Operation STALEMATE II ....................................................................................................... 27

Amphibious Strategy and Planning ....................................................................................... 28

UDT Operations ..................................................................................................................................... 30

Japanese Defences on Peleliu................................................................................................ 32

Pre-Assault Bombardment .................................................................................................... 36

The Assault............................................................................................................................. 37

White Beaches 1 and 2 ........................................................................................................................ 42

Orange Beaches 1 and 2 ..................................................................................................................... 45

Orange Beach 3 ...................................................................................................................................... 48

D-Day Plus .............................................................................................................................. 50

iv

�The Aftermath of the Battle ...................................................................................................... 52

Chapter 4: Peleliu Invasion Beaches and KOCOA Analysis ........................................................... 53

Introduction............................................................................................................................... 53

Pre-invasion Beach Reconnaissance ......................................................................................... 56

D-Day Landing and Initial Assault .............................................................................................. 58

White Beaches ....................................................................................................................... 59

Orange Beaches ..................................................................................................................... 65

Summary of KOCOA Features and Battlefield Boundaries ....................................................... 69

Battlefield, Core, and PotNR Boundaries .............................................................................. 69

Chapter 5: Landscape Modification and Salvage .......................................................................... 72

Introduction............................................................................................................................... 72

Orange Beaches......................................................................................................................... 72

Pontoon Causeway and Harbor ............................................................................................. 73

Airfield Complex .................................................................................................................... 76

Base Development................................................................................................................. 78

Orange Beach Cemetery ........................................................................................................ 80

Orange Beach Shoreline and Marina Dumpsites .................................................................. 82

White Beaches........................................................................................................................... 83

Post War Salvage ....................................................................................................................... 84

Chapter 6: Potential Losses and Invasion Beach Investigation .................................................... 87

Potential Losses in the Project Area.......................................................................................... 87

Peleliu Invasion Beach Investigation ......................................................................................... 88

Terrestrial Inshore Survey ..................................................................................................... 89

Previously Recorded Japanese Defensive Positions................................................................ 91

Previously Unrecorded Japanese Defensive Positions ........................................................... 91

Sites Inshore of the Invasion Beaches........................................................................................... 96

Lagoon Survey...................................................................................................................... 101

Reef Towed Swimmer Survey .............................................................................................. 106

Chapter 7: Modeling ................................................................................................................... 111

Introduction............................................................................................................................. 111

v

�Site Location Analysis .............................................................................................................. 115

White Beaches 1 and 2 ........................................................................................................ 115

Orange Beaches 1, 2, and 3 ................................................................................................. 117

Chapter 8: Conclusion ................................................................................................................. 122

References Cited ......................................................................................................................... 124

Appendix 1: Sites Investigated and Documented ....................................................................... 132

Appendix 2: Modern Finds ......................................................................................................... 136

vi

�List of Figures

Figure 1. Sites identified during the 1981 survey by Denfeld. Denfeld 1988:5, Figure 21. .......... 16

Figure 2. Location of Palau in the Western Caroline Island. USMC map n.d. .............................. 21

Figure 3. Japanese Mandated Islands in 1921. United States Military Academy, 1941............... 22

Figure 4. Palau Islands. Hough 1950:5, Map 2.............................................................................. 23

Figure 5. The extent of Japanese military control in the Pacific. The two-pronged battle plan to

the Japanese home islands went through Palau to the Philippines. Major battles indicated in

red. U.S. forces offensive drive strategy indicated in blue. NPS, War in the Pacific National Park,

n.d. ................................................................................................................................................ 25

Figure 6. The first wave of LVT(A)s move toward the invasion beaches, passing through the

inshore bombardment line of LCI gunboats, September 15 1944. Cruisers and battleships are

bombarding from the distance. The landing area is hidden by dust and smoke. Photographed

from a USS Honolulu (CL-48) plane. NARA RG-80-G-283533. ...................................................... 29

Figure 7. UDT teams documented an array of obstacles offshore of the Orange beaches, similar

to the double row of wooden posts at Scarlet 1 and 2 on the opposite side of the island from

the invasion beaches. Navy Seal Museum, 2002.0034.19. .......................................................... 30

Figure 8. UDT Team 6 map of obstacles and blast ramps for the amphibious landing at Orange 3.

Logsdon 1944. NARA RG-38, Box 788. .......................................................................................... 31

Figure 9. Andy Anderson, GM1/c, of UDT 7, with a J-13 mine at Peleliu. This type of ‘horned’

mine was particularly dangerous because it was so unstable. Navy Seal Museum, 2002.0034.12.

....................................................................................................................................................... 32

Figure 10. Japanese defensive plan. Garand and Strobridge 1971:74 Map 3 by E.L. Wilson;

reproduced in Hough 1950:38, Map 5.......................................................................................... 34

Figure 11. U.S. Scheme of Maneuver for Peleliu Operation. Hough 1950:20, Map 4.................. 39

Figure 12. Aerial view of White Beaches 1 and 2 on D-Day, September 15, 1944. White 1 and 2

were assigned to the 1st and 3rd Battalions, 1st Marines. Company K, 3/1 is on the extreme

north flank. The “Point” is on the northern promontory. NARA RG-127, USN Photo 283745. ... 40

Figure 13. The LVTs move toward the invasion beaches, September 15, 1944. NARA RG-80-G283533. ......................................................................................................................................... 42

Figure 14. Assault on Peleliu showing assigned beaches for each Marine Regiment. USMC

Historical Center, 1950, Map by R. Johnstone.............................................................................. 43

Figure 15. Marine riflemen take temporary shelter behind an LVT. The name of the LVT [The

Bloody Trail] was more than prophetic. DOD Photo, USN 95253. ............................................... 45

Figure 16. D-Day Showing disposition of troops. Hough 1950:56, Map 6 by E.L. Wilson. ........... 46

Figure 17. Marines landing on Orange Beach 1. Burning amtracs in the distance. NARA RG-127.

....................................................................................................................................................... 47

vii

�Figure 18. Japanese anti-tank ditch on Orange 3 providing cover for 7th Marines Command Post

on D-Day. DOD Photo, USMC 94939............................................................................................. 49

Figure 19. Operational Assault objectives September 15 to October 15, 1944. U.S. Army of

Military History, Battle of Peleliu, Source:

http://www.army.mil/cmh/brochures/westpac/p27(map).jpg, 2005......................................... 51

Figure 20. U.S. Invasion Objectives at Peleliu. Top inset: Location of Landing Beaches in Palauan

Archipelago. Bottom inset: Location of Landing Beaches on Peleliu Island. Image by Roth/Ships

of Discovery................................................................................................................................... 57

Figure 21. Reconnaissance Map of the White Beaches created by UDT 7. Burke 1944. NARA RG38. ................................................................................................................................................. 58

Figure 22. Smoke from the naval and aerial bombardment rises from Peleliu the morning of

September 15, 1944. Photograph taken from USS Clemson. Bureau of Aeronautics Materials,

247290. ......................................................................................................................................... 60

Figure 23. Japanese beach obstacles and fields of fire from coastal defenses on the White

beaches. Although most of the range markers were removed by UDT 7, they remain in this

image to aid reader with artillery visualization. Artillery caliber sizes and associated ranges were

calculated from 2018 site investigation and previous investigation of coastal defenses (Denfeld

1988; Price et al. 2012; Price and Knecht 2015). Map by Roth/Ships of Discovery. .................... 61

Figure 24. Burning amphibious vehicles off White beaches 1 and 2 on September 15, 1944. The

White/Orange coral promontory is visible with smoke rising behind in center of image. Note

range markers and posts off the beach. Bureau of Aeronautics Materials, 46697. .................... 63

Figure 25. The White/Orange promontory, seen on the right, caused minimal delay in troop

movement on White 2. By the time Davis reached the area, the majority of men were already

nearing the airfield. Frederick R. Findtner Collection, USMC Archives, 2-10. .............................. 64

Figure 26. Lt. (jg) “Butch” Robbins, UDT 7, with a Japanese J-13 “horned” mine at Peleliu, 1944.

National Navy UDT Seal Museum 2001.0105.14. ......................................................................... 65

Figure 27. Japanese beach obstacles and fields of fire from coastal defenses on the Orange

beaches. Artillery caliber sizes and associated ranges were calculated from 2018 site

investigation and previous investigation of coastal defenses (Denfeld 1988; Price et al. 2012;

Price and Knecht 2015). Map by Roth/Ships of Discovery. .......................................................... 66

Figure 28. KOCOA terrain features on the Peleliu Landing Beaches. Map by Roth/Ships of

Discovery. ...................................................................................................................................... 70

Figure 29. Suggested Battlefield, Core, and Potential National Register Boundary following 2018

fieldwork. Map by Roth/Ships of Discovery. ................................................................................ 71

Figure 30. Within hours of landing on the beaches, the Seabees began clearing damaged

equipment and materiel. Norm Hatch Photo Collection, National Museum of the Pacific War,

Image Peleliu 031, 1944. ............................................................................................................... 73

viii

�Figure 31. Seabees and engineers, working under fire, had this causeway operative by D+ 6 to

bridge the reef at the Orange beaches. Angaur Island at the top edge. Hough 1950:22. ........... 74

Figure 32. UTD 6 blasted a 15 ft wide channel through a shallow rock and gravel area in

preparation for a pontoon causeway (right). Logdson 1944. NARA RG-38.................................. 75

Figure 33. The construction of the harbor completely reconfigured the former area of the

causeway and a small unnamed islet. The UDT map overlays the current configuration of the

area. Graphic, Roth/Ships of Discovery. ....................................................................................... 75

Figure 34. Orange beach harbor construction, May 15, 1945. Orange beaches to the right. U.S.

Department of the Navy, Bureau of Yards and Docks, 1947:331................................................. 76

Figure 35. Japanese airfield on Peleliu on September 16, 1944, taken by a TBM-1C off USS San

Jacinto (CVL30). View to south. Orange beach in the upper right. NARA RG-80-G, Box 960...... 77

Figure 36. Airfield complex March 1945 showing the amount of development immediately

inshore of the Orange beaches. Military housing and other development extended along the

shore at the Orange beaches and inshore of White Beaches (upper left). NARA RG-127........... 77

Figure 37. View to the north along the Orange beaches showing extensive shoreline

modifications. By July 1945, the development extended to less than 10 m (33 ft.) of the shore,

destroying the Japanese defensive positions. NARA RG-127. ...................................................... 78

Figure 38. Detail from 1946 map of Peleliu titled “Ngarmoked NW-D, Palau Islands.” Note

southern harbor and tent areas on the White and Orange beaches. U.S. Army Map Service,

1946. ............................................................................................................................................. 80

Figure 39. A September 1944 aerial view of Orange Beach shows a portion of the extensive

Japanese tank traps and complexity of foxholes. Beginning of cemetery circled. NARA RG-127

(after Knecht et al., Figure 4.5, pg. 52). ........................................................................................ 81

Figure 40. Orange Beach cemetery with chapel in background. In 1946-47, all of the remains of

service personnel were removed and transferred to Manila, Hawaii, or the mainland. NARA RG127 (after Knecht et al. 2012:62). ................................................................................................. 82

Figure 41. View toward “The Point” at the north end of White Beach 1 showing the quantity of

heavy equipment and supplies being offloaded. Note the presence of a row of obstacles in the

lagoon. NARA RG-127. .................................................................................................................. 84

Figure 42. Landing craft, Orange Beach, Peleliu, March 1951. UHM Library Digital Image

Collections, Margo Duggan, accessed February 11, 2020,

https://digital.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/items/show/7808. ...................................................... 85

Figure 43. Landing craft, Peleliu, March 1951. UHM Library Digital Image Collections, Margo

Duggan, accessed February 11, 2020,

https://digital.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/items/show/7727. ...................................................... 86

Figure 44. Survey areas. Map Roth/Ships of Discovery. ............................................................... 89

Figure 45. Section of an August 1944 Japanese defensive plan. The red arrows are the Japanese

presumed US avenues of approach for the invasion. The blue arrows represent the fields of fire

ix

�of the gun emplacements across the invasion beaches and reef. The blue half-circles on the

beaches represent general defensive positions. Peleliu State Museum...................................... 90

Figure 46. UDT 6 reconnaissance map Orange beaches 1 and 2. Note the rows of wood posts to

the left and right of the cleared channels. Logsdon 1944. NARA RG-38, Box 788. .................... 111

Figure 47. UDT 6 reconnaissance map Orange 1. Note the row of mines (center) posts (left and

right) and 50 Kg aircraft bombs (far right). Logsdon 1944. NARA RG-38, Box 788. ................... 112

Figure 48. Japanese defensive positions map with invasion beach overlay shows the intensity of

the enfilading fire directed at the beaches. Approximate locations: White beach black lines,

Orange beach orange lines. Map section extracted from 1944 Japanese map, courtesy Peleliu

Museum. Illustration Carrell/Ships of Discovery. ....................................................................... 113

Figure 49. UDT 7 reconnaissance map of White Beaches 1 & 2. NARA. Note the presence of

range markers in approximately 3 ft. of water (indicated by X), and barbed wire closer in to

shore (indicated by x-x-x). Immediately inshore is a line of rifle pits. Burke 1944. NARA RG-38.

..................................................................................................................................................... 114

Figure 50. Sites identified at White Beaches 1 and 2, and the northern portion of Orange 1. Map

Roth/Ships of Discovery. ............................................................................................................. 116

Figure 51. Sites identified at Orange beaches 1, 2, and 3 (top to bottom). Map Roth/Ships of

Discovery. .................................................................................................................................... 118

Figure 52. Landing beach obstacles, blast channels, and cleared paths offshore of the Orange

beaches. Map Roth/Ships of Discovery. ..................................................................................... 120

x

�List of Tables

Table 1. Estimated Japanese Weapons on Peleliu and Ngedebus ............................................... 36

Table 2. Ships Involved in the Naval and Aerial Bombardment ................................................... 37

Table 3. Overview of KOCOA Attributes (after NPS 2016:5 and Babits et al. 2011) .................... 53

Table 4. Terrain Features and KOCOA Attributes Associated with Peleliu Amphibious Invasion 54

Table 5. Previously Recorded Japanese Defensive Positions ....................................................... 91

Table 6. Previously Unrecorded Japanese Defensive Positions ................................................... 92

Table 7. WWII Sites Inshore of the Invasion Beaches................................................................... 96

Table 8. WWII Lagoon Sites ........................................................................................................ 102

Table 9. WWII Reef Sites ............................................................................................................. 106

List of Acronyms and Abbreviations

AA

ABPP

AT

BB

CA

cal

CBD

CL

CP

CV

CVE

D+

DD

DMS

DOD

DOI

DON

DUKW

ft.

HPO

Anti-Aircraft

American Battlefield Protection Program

Anti-tank

Battleship

Heavy Cruiser

caliber

Construction Battalion Detachment

Light Cruiser

Command Post

Aircraft Carrier

Escort Carrier

Assault Day + 1, 2, 3 etc.

Destroyer

Destroyer minesweeper

Department of Defense

Department of the Interior

Department of the Navy

Amphibious truck

feet

Historic Preservation Officer

xi

�IJA

IJN

km

LCI

LCI(G)

LCUs

LCT

LCM

LCVP

LSD

LST

Lt. Col.

Lt. Gen.

LVTs

LVT(A)s

KOCOA

m

mm

NARA

NHCC

NOAA

NPS

OPC

RCT

RG

SCRU

SCUBA

TF

UCH

UDT

U.S.

USN

UXO

WWII

YMS

Imperial Japanese Army

Imperial Japanese Navy

kilometers

Landing Craft, Infantry

Landing Craft, Infantry, Gunboat

Landing Craft, Utility

Landing Craft, Tank

Landing Craft, Mechanized

Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel

Landing Ship, Dock

Landing Ship, Tank

Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant General

Landing Vehicle, Tracked

Landing Vehicle, Tracked, Armored

Key terrain, Observation, Cover and concealment, Avenue of approach and

withdrawal

meters

millimeter

National Archives and Records Administration

Naval History and Heritage Command

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

National Park Service

Objective 1, 2, etc.

Submarine Chaser

Regimental Combat Team

Record Group

Submerged Cultural Resources Unit

Self Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus

Task Force

Underwater Cultural Heritage

Underwater Demolition Team

United States of America

United States Navy

Unexploded Ordnance

World War II

Auxiliary Motor Minesweeper

xii

�Acknowledgements

This project would not have occurred without the help of a number of individuals and groups.

The Palau Historic Preservation Office was instrumental in making this project happen, clearing

the way for a site visit and assisting with the field reconnaissance. Special thanks go to Sunny

Ngirmang, HPO, and Calvin T. Emesiochel, Deputy HPO. Both were extremely helpful and

gracious with their time and support.

The agencies and organizations that supported this project on island include the Office of the

President Republic of Palau, the Office of the Governor State of Peleliu, the Belau National

Museum, the Office of the Palau Automated Land and Resource Information Systems (PALARIS),

the Palau National Aviation Administration, and the Bureau of Customs and Border Protection.

Thanks go to Shawn Arnold, John Burns, Jeff Enright, Mark Keusenkothen, Jason Nunn, Kailey

Pasco, and Jason Raupp, their field skills, hard work, and sense of humor made the project

memorable in the best possible way. A special thank you goes to Madeline Roth and Jennifer

McKinnon who contributed their considerable research, writing, and investigative expertise.

The project and this report benefited greatly as a result.

A thank you is also extended to the American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) for

providing the funding for this project. We would particularly like to thank Kristen McMasters,

Philip Bailey, and Emily Kambic for their support and guidance. A National Oceanic and

Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Ocean Exploration and Research Grant

(NA17OAR0110214) augmented the ABPP funds, allowing a longer site visit and remote sensing

survey.

Toni L. Carrell, Santa Fe

Ships of Discovery

xiii

�Chapter 1: Introduction

Introduction

The focus of this project is the World War II (WWII) Battle of Peleliu that began on September

12, 1944 in Palau Islands in the Caroline Island archipelago. Peleliu is located at the southern

end of the Palau Island chain and was a strategic objective for both the Japanese and U.S.

militaries. This project is the first effort to study the Peleliu WWII invasion beaches and the

offshore battlespace. It is a Phase I historical and archival research effort and follows guidelines

for identification activities as defined by the Secretary of Interior Standards for Archeology and

Historic Preservation. It analyzes information on the U.S. battle plan and execution, the

amphibious assault, the reported locations and extent of known losses, the positions and

influence of Japanese defensive batteries and gun emplacements, post-war cleanup, and

salvage operations.

The battlefield is examined using KOCOA analysis to understand the activities that influenced

the invasion and the decisions and limitations imposed by the natural terrain and built

environment. Based upon prior archaeological investigations, the historical record, a site visit

and reconnaissance survey of the invasion beaches and shoreline, post-invasion land

modification and salvage, and the KOCOA analysis, this report assesses the potential range of

sites and the underwater cultural heritage sites that remain.

This project was funded by a grant from the Department of the Interior (DOI), National Park

Service (NPS), ABPP under agreement GA-2287-17-015. A NOAA Ocean Exploration Grant,

under agreement (NA17OAR0110214), augmented these funds and permitted a longer site visit

and survey. The result of the NOAA remote sensing survey is reported by Carrell et.al. 2020.

Methodology, Limitations

The methodology focused on archival background research, primary and secondary accounts of

the battle, maps, and photographs, prior archaeological research, a battlefield visit, and

reconnaissance survey. It does not include site testing or in depth site investigation. The scope

of the project is limited to the Peleliu invasion beaches designated as White 1, White 2, Orange

1, Orange 2, and Orange 3, to approximately 30 m (100 ft.) inland. Seaward, it includes the

lagoon, the reef, and the immediate area just beyond the reef.

14

�Legislation and Jurisdiction

Historic shipwrecks in the Republic of Palau are protected through laws passed by the Republic

and the U.S. Federal government. The following is a list of legislation relevant to UCH and

military heritage:

•

•

•

•

•

The Abandoned Shipwreck Act 1987 protects historic shipwrecks “embedded in State’s

submerged lands.”

The Sunken Military Craft Act 2005 confirms right, title and interest of the U.S. to any

sunken military craft anywhere in the world as well as the same rights and protection to

non-U.S. military craft sunk in U.S. controlled bottomland.

The National Historic Preservation Act 1966 under Section 106 and 110 provides

protection for shipwrecks and other submerged sites concerning permit and mitigation

processes and requires inventory and assessment of such sites as standard procedure.

The Archaeological Resources Protection Act 1979 prohibits damage to archeological

sites that are 100 years or older and provides archeological and permit guidelines.

Palau Historical and Preservation Act of 1995 protects all cultural heritage stating, “The

national government reserved to itself the exclusive right and privilege of ownership

and control over historical sites and tangible cultural property located on lands or

waters owned or controlled by the national government. Each state reserves to itself

the exclusive right and privilege of ownership and control over historical sites and

tangible cultural property located on lands or waters owned or controlled by the state….

The Division may issue permits …for the purpose of historical and cultural preservation.

SS 134.

The Historic Preservation Office has the overall administrative responsibility for cultural

heritage in the Palau Islands. This obligation extends off shore to all UCH, whether or not they

have been identified or are yet to be investigated.

15

�Chapter 2: Previous Research, Archival Resources, Repositories

Previous Research

Archeological research on Peleliu has been remarkably limited given the importance and

tremendous loss of life during the battle. D. Colt Denfeld’s survey in 1981 was the first, funded

through the NPS as part of the on-going Micronesian Archeological Survey. The results of his

investigations, Peleliu Revisited: An Historical and Archaeological Survey of World War II Sites on

Peleliu Island (1988) identified 46 loci, most with several discrete features, totaling 142 sites. Of

particular interest to this project are the sites identified near the White and Orange invasion

beaches (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Sites identified during the 1981 survey by Denfeld. Denfeld 1988:5, Figure 21.

16

�The entire island of Peleliu was nominated to the National Register of Historic Places in 1984

(National Park Service 1984) and was considered for national landmark status in 1991 and again

in 2003 (National Park Service 2003).

From 1981 to 1989, archeologists from the NPS Submerged Cultural Resources Unit (SCRU)

visited a number of islands in the Pacific to support requests for assistance with submerged

sites. Each project generated its own small trip report, but it was not until 1990 that Dr. Toni

Carrell brought together the disparate information under one cover. The resulting Submerged

Cultural Resources Assessment of Micronesia (1991), not intended to be comprehensive nor

definitive, was designed “within a resources management framework . . . [to] generat[e]

information useful in submerged cultural resources site interpretation, protection, and

conservation; . . . [to] contribut[e] to the historical understanding of the region; and . . . [to]

answer questions of general archeological and historical interest” (Carrell 1991:1).

Included in the report was a discussion of sites in the Palau Islands. From April 11 to June 17,

1988, the SCRU team visited and documented a number of shipwreck sites within Ngemelachel

(Malakal) Harbor, Ngeruktabel (Urukthapel) Anchorage, the channel to Kobisang Harbor, and

Chelbacheb (the Rock Islands). In addition to shipwrecks, the team examined aircraft, landing

craft, and a sunken village. During a brief visit to the island of Ngargersiul to the north of

Peleliu, wreckage of at least two Japanese G4M “Betty” bombers were documented (Carrell

1991:537).

The team also conducted a limited four-lane magnetometer survey in Peleliu along the reef

edge offshore from the invasion beaches. The first lane was close to the reef in 30 ft. of water,

the second was in 50 ft. of water, the third and fourth runs were at 50 and 100 yards off the

reef in deeper water. No sites were located during this admittedly uncontrolled very brief

survey. Importantly, information from boat captain Pablo Siangeldep and Faunny Blunt

revealed that in addition to the considerable post-invasion salvage and cleanup effort of the

U.S. military, a “Chinese” company worked on contract to remove wreckage from the reef and

beaches and the wreckage was dumped into the extremely deep waters in the channel

between Peleliu and Angaur (Carrell 1991:542).

A long needed revisiting, reexamination, and expansion on Denfeld’s 1981 survey was

completed in 2010. Funded under an NPS ABPP Grant, Rick Knecht, Neil Price, and Gavin

Lindsay lead a team on an intensive nine-day survey of a portion of the Peleliu terrestrial

battlefield. Their report WWII Battlefield Survey of Peleliu Island, Peleliu State, Republic of Palau

(2012) includes updates to and cross-references of 72 of Denfeld’s sites and 200 additional

sites, not previously recorded. In total, they documented 285 sites related to the battle. Their

17

�updated information, including the invasion beaches, is particularly valuable for this study. A

second archaeological survey of Peleliu in 2014, built upon and expanded the 2010 fieldwork.

Peleliu Archaeological Survey 2014: WWII Battlefield Survey of Peleliu Islands, Peleliu State,

Republic of Palau by Lindsay, Knecht, Price, Raffield, and Ashlock (2015) recorded an additional

113 new sites. These two publications are a major contribution to the study of the Peleliu

battlefield.

In the post-war years numerous histories, accounts, monographs, and official military accounts

of the battle were published. The most comprehensive are: The History of the U.S. Marine Corps

Operations in World War II: Volume IV, Western Pacific Operations by Garand and Strobridge

(1971); History of US Naval Operations in WWII: Volumes VIII and XIII by Samuel Eliot Morison

(1962); and United States Army in World War II, The War in the Pacific: The Approach to the

Philippines by Robert Ross Smith (1996).

Numerous others provide a wealth of additional material: McMillan 1949, Hough 1950, Craven

and Gate 1953, Smith 1953, and Fane and Moore 1956. Other syntheses include Gailey 1983,

Ross 1991, Hallas 1994, Gilliland 1994, Moran and Rottman 2002, Wright 2002 and 2005,

Rottman 2003 and 2004, and Murray 2006. Histories and memoirs include Leckie 1957, Sledge

1981, Hunt 1958, Gayle 1996, and Croziat 1999. Recent unit histories include Blair and

DeCioccio 2011, Camp 2008, and Woodard 1994. Price et. al. (2013) offer a thoughtful

discussion of multi-cultural perspectives in conflict archeology.

Archival Resources and Repositories Consulted

Declassified WWII documents, including unit histories, field reports, operations reports, and

maps produced while the battle was in progress, along with extensive archival photographic

records, are available to the public at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

These documents and photographs are becoming available for download through their online

site. For images taken before 1982, it is necessary to contact the Still Pictures Branch.

Of particular use for the study of Marine Corps actions during WWII, is the Record Group 127.9

Records of Marine Units, 1914-1949. This record group includes the following textual records:

Records of Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, including general correspondence, 1942-1946; and

"geographical" operation file ("Area File"), 1940-1946. Geographical and subject files of the 2nd

Brigade, Fleet Marine Force, 1933-1942. General correspondence, 1st-6th Marine Divisions,

1941-1946. Organization records of ground combat units, 1941-1946. Correspondence and

reports of Headquarters, 2nd Marine Division, 1942-1949. Correspondence of the 1st, 3d, and

18

�10th Marine Defense Battalions, 1943-1944. Issuances, 1914, and correspondence, 1917- 1919,

of the 5th Marine Regiment. Administrative records of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, 1942-1947.

Aircraft action reports of the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing, 1944-47. Records of the 2nd Marine

Aircraft Wing, consisting of correspondence and reports, 1941-1945; and administrative file,

issuances, and miscellaneous personnel reports, 1946. Selected general correspondence files,

1933-1934, and logbooks, 1931-1934, of Marine Aircraft Squadrons VS-14M and VS-15M.

The Naval History and Heritage Command (.NHCC) has an extensive website. Of particular use

to researchers is their extensive digital collection of ship histories and images.

The National Museum of the Pacific War (http://www.pacificwarmuseum.org/) has a range of

exhibits and interpretive programs. Of the most use is their digital archive collections from the

Nimitz Education and Research Center archival collection. The collection includes WWII

veterans’ oral histories, the Chester W. Nimitz Personal Letters Collection (1893-1911), and the

Norm Hatch WWII Photographic Collection. Hatch joined the Marine Corps in 1939 and served

as a combat photographer. This collection includes official Marine Corps photographs taken by

Hatch while on duty from Tarawa, Iwo Jima, Okinawa, Peleliu, the Marshall Islands, Guam,

Tinian, Saipan, New Britain, and Nagasaki.

The U.S. Navy Seal Museum’s main objective is the promotion of public education through

interpretive history (https://www.navysealmuseum.org/). Of particular use for researchers is

the Navy Seal Museum Online Collections Database that includes photographs, textual

documents, and images of objects (https://navysealmuseum.pastperfectonline.com/).

The U.S. Navy Seabee Museum’s mission is to select, collect, preserve and display historic

material relating to the history of the Naval Construction Force, better known as the Seabees,

and the U.S. Navy Civil Engineer Corps

(https://www.history.navy.mil/content/history/museums/seabee.html). Of the most use are

unit histories, an online reading room, and a digital collection of historic photos. Photos of the

Peleliu operation are limited. Of more use is a finding aid for Seabee records, available by

request.

The Marine Corps History Division, Archives Branch (mcu_archives@usmcu.edu) holds

extensive online materials that include personal papers, command chronologies, Marine Corps

University materials, select official and unofficial Marine Corps unit materials, and oral

histories. Among the personal papers collections are those of General Roy S. Geiger and

General Holland M. Smith, both pivotal commanders in the Pacific theater. The campaign

collection on Peleliu includes an official document finding aid, photographs, and monographs

19

�by General Gordon D. Gayle (1996) and Major Frank O. Hough (1950). Of particular use for this

project was the Peleliu Collection finding aid (COLL/3687). Marine Corps University research

papers include an online finding aid. Extensive finding aids are available as well as selected

digitized publications.

The Historic Naval Ships Association ( https://www.hnsa.org/) is comprised of an international

membership of naval ship museums. Of the most use are their submarine war reports digital

collection of over 1,500 patrol reports (https://www.hnsa.org/manuals-documents/submarinewar-reports/). Appendices provide tabulations of information across multiple war patrols. In

addition, there is an Excel formatted spreadsheet with the Special Operations Research Group

Summary of U.S. Submarine Attacks in WWII.

Perhaps the most useful resource among the online databases is Fold3, a subscription resource

of more than 1 million digitized records on WWII. It includes photographs, reports, casualty

lists, diaries, and similar. Other online sources of information consulted include the numerous

digitized WWII publications at HyperWar, a Hypertext History of the Second World War

(http://www.ibiblio.org/hyperwar/). Of use was the Pacific Theater of Operations. The site

includes a number of Japanese Monographs (http://ibiblio.org/hyperwar/Japan/Monos/)

addressing political strategy, pre-war planning, and regional operations. The Ike Skelton

Combined Arms Research Library Digital Library had limited but useful information in their

World War II Operational Documents collection.

20

�Chapter 3: Historical Background 1911-1945

The Palau Islands 1911-1941

The end of World War I had important ramifications for the Caroline Islands, including the

Palaus. Located in the Western Caroline Islands (Figure 2), Palau effectively became a Japanese

Imperial possession in October 1914 when a Japanese occupation force arrived at Koror Island.

They quickly established administrative control over the island chain and began limited military

development with a harbor facility at Malakal, an airfield at Peleliu, and a seaplane base at

Arkabesan. After October 14, all ships “... entering or leaving the islands ... were under the

jurisdiction of the Japanese Minister of the Navy.... Nothing could be done without the

permission of the Japanese military forces” (Purcell 1967:89-90). The islands were firmly under

military control throughout World War I. However, Japanese administration did not officially

began in the Caroline Islands until 1921 when the League of Nations approved the defacto

occupation of Palau as one of their mandated territories. By 1921, the face of the Palaus had

changed dramatically. With Japan’s power firmly established, coupled with its expansionist

visions, the islands were essentially possessions, effectively sealed off, and fully integrated into

the Japanese Empire.

Figure 2. Location of Palau in the Western Caroline Island. USMC map n.d.

21

�During the inter-war years, Japan developed the mandated islands under their control (Figure

3) as advanced naval facilities, fighter and bomber long-range patrol bases, and as submarine

bases. Increasingly militaristic and expansionist, Japan sought to strengthen its presence in the

Pacific.

Figure 3. Japanese Mandated Islands in 1921. United States Military Academy, 1941.

Despite extensive efforts from 1931-1941 to establish interlocking air bases and to provide

suitable naval harbors and intermediate repair facilities, these areas never fully developed into

first-class facilities until 1943 (Boyer 1991:259).

The Palau islands are an example of the limitations of the Japanese military build-up prior to

WWII. The administrative headquarters for the all of the Japanese mandated islands was Koror,

in the Palaus (Figure 4). The largest island in the chain, Babelthaup, was an ideal base for

ground troops, but had only a small airstrip. By 1941, however, Koror had seaplane docks and

AA defenses while nearby Arakabesan Island had a seaplane base and a submarine base. The

greatest value of the Palaus lay in the large anchorages at Malakal Harbor in the west and

22

�Kossol Passage to the north. The anchorage at Malakal served as a strategic staging area for the

Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) units. With the large and well-developed airfield in Peleliu, both

naval and aircraft units could access and support the Japanese held Netherlands Indies and

New Guinea (Hough 1950:9).

Figure 4. Palau Islands. Hough 1950:5, Map 2.

23

�The Palau Islands in WWII, 1941-1945

Across the Pacific, word spread that war was coming, however, only Japan knew when and

where it would start. Shortly after the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii,

Japanese forces initiated air attacks over Guam, which they had been openly monitoring since

November. Poorly defended by the U.S., Guam fell on December 10 within six hours of the

Japanese military invasion. With this prize under its belt, the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and

Navy mounted very successful aggressive operations across the Pacific in the early years of the

war. By August 1942, the Japanese forces extended their areas of control as far as Attu Island in

the Aleutians to the north, Guadalcanal to the south, and Tarawa to the west (Figure 5).

Palau served as the jumping-off point for a small carrier task force that assaulted the southern

Philippines at Davao. Assault troops for the Mindanao invasion also staged through Palau, and

the area remained a critical link in the Japanese supply routes from Saipan in the north to New

Guinea in the south and east toward Truk. Air bases on Peleliu and Babelthaup were enlarged

and developed to protect the islands and for aircraft on route to the Southern and Central

Pacific battlegrounds. The islands also served as an amphibious training ground for various

military units. Despite this buildup, the Japanese military had not really given much thought to

heavily fortifying the Palau base. They appeared to be more interested in offensive operations

to ensure capture and consolidation of the oil-rich southern areas than in strong defensive

fortification of their existing major Central Pacific bases.

In September 1943, following a string of defeats, the Japanese military began serious efforts to

improve the fortifications of their inner defensive perimeter, particularly in Palau and the

Marianas (Boyer 1991:259). By early 1944, the Palau islands were host to 14,500 IJA and 3,000

IJN personnel on Babelthaup. A garrison of approximately 6,900 IJA and 4,000 IJN personnel

were stationed on Peleliu, and a perimeter garrison of 1,400 men were on Angaur to the south

and another garrison on Ngesebus, to the north of Peleliu. Nearly 10,000 Korean and Okinawan

conscripted laborers formed a support construction battalion (Knecht et.al. 2012:7; Hough

1950:17-18). The buildup of Babelthaup, in particular, had long-term consequences for the

planned U.S. invasion.

24

�Figure 5. The extent of Japanese military control in the Pacific. The two-pronged battle plan to

the Japanese home islands went through Palau to the Philippines. Major battles indicated in

red. U.S. forces offensive drive strategy indicated in blue. NPS, War in the Pacific National Park,

n.d.

After the U.S. entered WWII in 1941, military planners quickly developed an island-hopping

strategy for a westward push across the Pacific to the Japanese home islands. The two-pronged

offensive drive involved the Army, led by General Douglas MacArthur, advancing from New

Guinea to the Philippines and the Navy, led by Admiral Chester Nimitz, pushing through the

Gilbert and Marshall Islands across the Central Pacific to take the Marianas, then to move

quickly westward across the Pacific (Figure 5).

25

�This broad strategy proved successful for the U.S., and the Japanese government realized, “A

strangling noose was tightening around the inner perimeter guarding the path to their

homeland” (Lodge 1954). By February 1944, successful operations in the Solomon Islands and

in the Bismarck Archipelago in the south and the Gilbert and Marshall Islands in the central

Pacific paved the way for the next phase and the westward advance to the Marianas and

Caroline Islands (Moran and Rottman 2003:14).

Pre-Assault Air Operations and Reconnaissance

By March 1944, plans were well underway for the invasion of Hollandia, New Guinea. The fast

carrier strikes by Task Force (TF) 58 on Truk on February 17-18, forced the IJN Combined Fleet

to retreat to Palau. Intelligence reports suggested that Koror, Malakal Harbor, and Kossol Roads

were the most important Japanese naval bases east of Manila. On Peleliu, the Japanese airfield

was within easy flying distance of Hollandia and the airfield on Babelthaup was being enlarged.

The presence of the IJN fleet in Palau and the extensive use of the Peleliu airfield in support of

Japanese troops in New Guinea was considered a potential threat to the Hollandia offensive

(Morrison 1953:28).

On March 30-31, TF 58 conducted 11 group air strikes throughout the island chain against

shipping, aircraft, and installations to reduce operational capacity (Montgomery 1944:1). Over

the two days 839 sorties were flown, 186 tons of bombs dropped, 12 torpedoes launched, and

29 mines laid by U.S. Grumman F6F Hellcats and TBM Avengers, a first for carrier based

bombers (Morison 1953:32). Final counts include 53 Japanese planes destroyed in and around

Koror and an additional 52 damaged or destroyed at the Peleliu airfield (Montgomery 1944:6,

10). Importantly, the operation was the first systematic aerial surveillance of the island chain

and Peleliu (Garand and Strobridge 1971:77).

Although IJN warships escaped prior to the March 30 assault, U.S. aircraft sank 22 vessels,

including four older Wakatake class destroyers, fuel tankers, and cargo ships, in the Palau

harbor while damaging a further 36 single and twin engine aircraft (Montgomery 1944:7,11,

17). Finally, pilots reported ground installations across the archipelago as damaged or

destroyed. On Peleliu, the airfield bore the brunt of the bombings with damage to fuel tanks,

airplane hangars, warehouses, and the tarmac (Montgomery 1944:11).

In the wake of the March attack, the Japanese military began rebuilding the Peleliu airstrip and

redoubled their efforts to enlarge and expand the island’s underground defenses. In a further

effort to reinforce the island’s garrison, the 6,500-man battle-hardened Second Infantry

Regiment was dispatched. They brought with them 24 75mm artillery pieces, 13-15 light tanks,

approximately 100 .50-cal machine guns, 15 81mm heavy mortars, and about 30 dual-purpose

26

�AA guns. These complimented existing 141mm mortars, naval AA guns, and rocket launchers

(Gayle 1996:24-25).

Because the Palaus were under Japanese military control and public access was strictly

controlled beginning in 1914, intelligence data was limited and charts and maps were

completely inadequate. In June 1944, and again in August, submarine photographic

reconnaissance of the beaches was attempted. On August 11, USS Burrfish (SS312) was able to

deploy a five-person team to gather critical information on water depths, locations of potholes,

sand bars, the configuration of the fringing reef, and seabed (USS Burrfish Report of Third War

Patrol, 11 July to 27 August 1944). The carrier raids on March 30-31, 1944 provided aerial

imagery of the island, supplemented by dedicated photographic flights in July and August.

According to Denfeld, the photographic coverage was excellent and clearly showed the various

geographical features of the island. Disastrously, the jagged pinnacles and crevice-filled

limestone ridges hidden by dense foliage were interpreted by analysists as gentle hills (Denfeld

1988:6).

Operation STALEMATE II

Planning for the Palau invasion went through several iterations beginning on June 2, 1944.

MacArthur's forces were preparing for the Philippines operation and planners decided that the

Western Caroline Islands were critical to secure the right flank of the Philippine invasion.

Although badly damaged by repeated airstrikes in March, Peleliu’s air base was considered a

threat to an amphibious landing on Mindanao. Palau was viewed as the last major obstacle to

the Philippines and Peleliu was the key.

Pre-assault air operations began on June 9, 1944 with a strike on Peleliu’s airfield by land-based

Army Air Forces. Subsequent strikes were mounted from fast carrier groups (Morison 1953

[2002 ed.]:174). Between July 25-28, 1944, TF 58.2 and 58.3 attacked the three airfields in

Palau, destroying 47 planes, and searched the surrounding sea for ships (Morison 1953 [2002

ed.] 367).

By August 1, 1944, the planning and logistical guidelines for Operation Stalemate II were set.

Babelthaup was dropped from the list of targets because of the presence of a large garrison of

well-trained Japanese navy and army troops (Denfeld 1988:41). Plans coalesced around Peleliu

for the main attack, Angaur, and Ulithi. Under the plan, the three islands would become U.S. air

and sea bases to neutralize Japanese military bases and operations in the Caroline Islands.

Peleliu’s strategic location was ideal for flights to and from the Philippines in support of the

larger war effort (Denfeld 1988:6).

27

�The operation involved the 1st Marine Division and the U.S. Army's 81st Infantry Division, with

their attached units, totaling more than 43,500 officers and men. They faced battle-seasoned

and well-trained soldiers, primarily from the Japanese Army's 14th Division, originally part of

the Kwantung Army in China. This four-to-one advantage was illusory, however, because the

fighting involved about even numbers on both sides, a situation “...that should have made even

the most optimistic planners shudder” (Gailey 1983:23).

Long-range reconnaissance and carrier-based attacks continued in August 1944 with the Fifth

Air Force’s B-24 Liberators beginning a concentrated operation to knock out defenses

throughout the archipelago. A series of flights from August 8 to September 14 dropped 91 tons

of fragmentation, demolition, and incendiary bombs over the islands, and beginning on August

25 the heavy bombers started making daylight bombing runs encountering heavy AA fire. Over

394 sorties, the Liberators dropped 793 tons of explosives and destroyed over 500 buildings in

Koror Town. Reconnaissance on September 5 showed only 12 Japanese fighter planes, 12

floatplanes, and 3 observation aircraft still based in the islands (Garand and Strobridge

1971:101). The cumulative result was that nearly all Japanese aircraft were destroyed, what

few ships remained were sunk, the harbors were sown with mines, and the garrisons on

Babelthaup and Koror were isolated and trapped (Knecht et. al. 2012:7).

However, to achieve success against well-fortified islands required an unprecedented level of

coordination between the U.S. Navy, Marines, and Army. It also required a completely new way

of thinking, new equipment designed specifically for the task (amphibious craft), and specially

trained teams of men. The new strategy was predicated on getting the maximum number of

men safely on shore as quickly as possible. In the case of Peleliu, it was to get 4,500 Marines

ashore in the first 19 minutes of the assault. Paving the way for the remaining 24,000 to land

within 90 minutes.

Amphibious Strategy and Planning

The complex technique devised for putting men ashore on an enemy held coast fringed by a

reef and lagoon, involved hard lessons learned. From Tarawa, the amphibious landing force

stalled getting across the reef because of unknown obstacles. From Guam and Makin, forcing

men to wade from the reef edge across an exposed lagoon raked with enfilading fire, cost many

lives. Those mistakes were not to be repeated at Peleliu.

The new plan involved five imaginary parallel lines offshore where various elements of the task

force would stage with their ships and troops before the assault. Farthest out at 18,000 yards

were the big ships and transports. Alongside the battleships were the LSTs (landing ship, tank)

28

�carrying the troops in LVTs (landing vehicle tracked) in their cavernous holds. At 6,000 yards

from shore, the LSTs opened their bow doors and the small LVTs (sometimes called amtracs)

embarked. The fourth line was 4,000 yards from shore, still 30 minutes travel time to the beach.

This was the rendezvous line for all of the assault waves to form groups opposite their

designated beaches. The final line before the reef was at 2,000 yards and 15 minutes from

shore, where the LVTs returned after carrying the assault waves to the beach and where the

next groups of men and supplies transferred from small boats. When the troop carrying

amphibious fleet reached the last line at 1,000 yards, they were on their own to cross the reef

and get to shore (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The first wave of LVT(A)s move toward the invasion beaches, passing through the inshore

bombardment line of LCI gunboats, September 15 1944. Cruisers and battleships are bombarding from

the distance. The landing area is hidden by dust and smoke. Photographed from a USS Honolulu (CL-48)

plane. NARA RG-80-G-283533.

Stewarding the small fleet at each line were submarine chasers, patrol craft, and Higgins boats

(LCVP) hoisting signaling flags, forming up the waves, coordinating the ship-to-shore

movement, and in constant radio contact (Hough 1950:22). Preceding the first waves of

personnel, were armored LVT(A)s (landing vehicle tracked, armored, sometimes called

amphibious tanks) armed with machine guns and howitzers, to neutralize beach defenses and

support the landings. LCI(G) (landing craft, infantry, gunboats) armed with rockets stood

29

�offshore at the 1,000-yard line and raked defensive positions and provide covering fire for the

LVT(A)s. Overhead, naval gunfire pummeled the island and aircraft bombed and strafed. The

landing was a complex maneuver requiring precise timing and coordination (Denfield 1988:12).

UDT Operations

As careful as the plan was, unless the amphibious craft could get over the reef, avoid the mines,

navigate the concrete anti-boat obstacles, the coral heads, boulders, and land on shore, it was

doomed to failure. The Navy underwater demolition teams (UDTs) were formed in 1942 in

response to this fundamental problem. However, it was not until the near failure of the landing

at Tarawa that their importance was recognized. From that point forward, UDT reconnaissance

was integral to all planning.

In the run up to the Peleliu operation, UDT 10 scouted the invasion beaches in USS Burrfish. The

information gathered in August 1944, revealed an array of concrete tetrahedrons, a double row

of wooden posts 75 yards from shore, barbed wire, and horned mines. Importantly they

discovered that in some areas the reef was awash with barely 2 ft. of water at low tide (Figure

7).

Figure 7. UDT teams documented an array of obstacles offshore of the Orange beaches, similar to the

double row of wooden posts at Scarlet 1 and 2 on the opposite side of the island from the invasion

beaches. Navy Seal Museum, 2002.0034.19.

30

�On September 12, under the cover of the unrelenting naval and carrier fire, UDTs 6 and 7

landed for the third time on the offshore reefs off the Orange Beaches while periodic sniper

and machine gun fire from shore targeted the unarmed swimmers. Their role was to create

avenues of approach for the assault teams by blasting wide ramps for the LSTs and pathways

for the DUKWs (amphibious trucks) to enter the shallow lagoon (Burke 1944:3, Hutson 1944:2).

They previously mapped the depth of the lagoon, charted obstacles, and placed buoys and

markers (Garand and Strobridge 1971:103).

On this final mission, the UDTs crawled ashore to finish the job of demolishing rock cribs, posts,

barbed wire, concrete cubes, and set buoys off the reef to mark the newly blasted passageways

(Figure 8, Figure 9).

Figure 8. UDT Team 6 map of obstacles and blast ramps for the amphibious landing at Orange 3.

Logsdon 1944. NARA RG-38, Box 788.

31

�Figure 9. Andy Anderson, GM1/c, of UDT 7, with a J-13 mine at Peleliu. This type of ‘horned’ mine was

particularly dangerous because it was so unstable. Navy Seal Museum, 2002.0034.12.

Japanese Defences on Peleliu

After a string of losses and the fall of Saipan, the Japanese military developed a new strategy

for island defense. The tactics used in the battles at the Gilbert, Marshall, and Mariana Islands

was to meet and destroy the enemy at the beach and, if necessary, push them back into the sea

using counterattacks. The new defensive plan retained that core element, but added the

strategy of organizing defenses in depth (Denfield 1988:9). Lt. Gen. Sadae Inoue, the

commander of the Japanese 14th Division and the Palau Sector Group, and his chief of staff,

Colonel Tokechi Tada agreed there would be no useless banzai charges or attempts to throw

the enemy back into the sea at the beach in the Palaus. Instead, defenses needed to thwart U.S.

naval and air bombardment with deep caves and allow defenders to fall back on previously

developed positions. On Peleliu alone, over 500 natural and manmade caves were developed

(Boyer 1991:262). The new doctrine dictated by the Imperial Government Headquarters

outlined the defense strategy:

32

�We will maintain a firm hold on the high ground and prevent the enemy from

establishing or using an airbase. We will commence … guerrilla warfare and … will

carefully guard the breaks in the high ground (CINCPAC Item No. 11, 902, A Battle Plan

for the Defense of Peleliu Island, September 1, 1944).

On Peleliu, Navy Colonel Kunio Nakagawa, commander of the 2nd Regiment and Commander of

the Peleliu Sector Unit, had artillery, mortar, signal, and light tank units under his command.

Bolstering that combat strength were the 346th Independent Infantry Battalion of the 53rd

Independent Mixed Brigade and the 3rd Battalion, 15th Infantry. The Navy added the 144th and

126th AA units, the 45th Guard Force Detachment, and construction units and airbase

personnel. In all, Nakagawa had approximately 6,500 combat troops, service troops, and noncombatants, bringing the garrison up to 10,500. Some 25,000 troops on the other Palau Islands,

many specially trained in amphibious operations, were reinforcements (Garand and Strobridge

1971:68-69).

Army Major General Kenjiro Murai, a fortifications expert, took command of the garrison on

Peleliu. Because of the rivalry between the Japanese Navy and Army, Mauri oversaw the

construction and location of defensive fortifications and caves. The model for the in depth

strategy was Biak. The Japanese commander there prolonged the fighting by digging in and

forcing the U.S. troops to rout out each defensive position in a long, bloody operation. This

lesson, applied to Peleliu, focused on a main line of defense inland, holding back reserve troops

to mount counterattacks, and numerous layered defensive positions. In deploying the reserve

troops Inoue directed that “there will be no rapid exhaustion of battle strength” and soldiers

were to “advance at a crawl, using terrain, natural objects, and shell holes” (Garand and

Strobridge 1971:72). The resulting defense system was organized, integrated, and flexible with

four zones: northwest, southwest, southeast, and east (Figure 10).

Colonel Nakagawa’s and General Murai’s coastal defenses centered on the southwest coast,

the only realistically usable landing beaches on Palau. Preparation of the beach defenses

followed previously developed strategies. The natural offshore fringing reef was augmented by

the strategic positioning of tetrahedron-shaped tank obstacles, barbed wire, aerial bombs

adapted to serve as mines, over 300 single- and double-horned anti-invasion mines, extending

30 m (100 yards) or so inland and long anti-tank trenches running parallel to the beach (Garand

and Strobridge 1971:72-73).

33

�Figure 10. Japanese defensive plan. Garand and Strobridge 1971:74 Map 3 by E.L. Wilson;

reproduced in Hough 1950:38, Map 5.

34

�The efficacy of the offshore mining was well demonstrated by the losses of USS Perry (DD-340

re-designated DMS-17) on September 13, 1944, USS Woodstock (PC-1180) on September 19

both off Angaur. The loss of LCI(G)-459 also on September 19 off Peleliu, and USS YMS -19 sunk

off Angaur September 24, 1944 (NHHC USS Perry-340; NHHC USS Woodstock; NARA Report of

USS LCI(G)-458 of September 18-19, 1944, accessed in Fold3).

Peleliu’s southwestern promontory and a small island, a few hundred yards offshore, had antiboat guns and machine guns to furnish enfilading fire on the southern beachheads.

Everywhere, the dominating terrain was used for the placement of artillery, previously zeroedin on the beaches, to wreak havoc among the assaulting troops. The defensive positions took

full advantage of modified and natural cover and concealment to dominate all invasion

approaches (Garand and Strobridge 1971:73-74). According to Denfeld, the Peleliu landing

beaches had a defensive strategy and trench network of a density only surpassed by those on

Iwo Jima (Denfeld 1988:44).

On the flat terrain inland from the beaches, the defense consisted of direct fire against

advancing troops from well-camouflaged pillboxes, trenches, and other defensive positions,

with artillery and mortar fire from the dominating ridges to the north of the airfield. Pillboxes

dug into these ridges and a casemate for a 75mm mountain gun commanded the entire

southern portion of the island. At least one steel-reinforced concrete blockhouse had as many

as 16 mutually supporting automatic weapons (Garand and Strobridge 1971:73).

Tactical reasons determined the location of the Army’s caves in the ridges and mountains. The

placement of fortifications, weapons, and soldiers provided a mutually interlocking system of

concrete pillboxes, entrenchments, gun emplacements, and riflemen’s positions all dominating

the strategic areas. Near every important artillery or mortar emplacement were underground

positions with automatic weapons for protective fire. Communication trenches or tunnels

connected these mutually supporting locations. Observation posts on top of the ridge in natural

limestone cavities or crevices provided a strategic overview while being well hidden. The

approaches to vital installations were covered from all angles by fire from caves halfway up the

surrounding ridges. At most strategic points and in the final defensive area numerous smaller

underground positions were placed to provide interlocking support fire from small arms

(Garand and Strobridge 1971:75-76).

The U.S. estimate of Japanese weapons on Peleliu and Ngedebus in August 1944 was woefully

inadequate. It did not account for the weapons brought to the island by Colonel Nakagawa’s

2nd Infantry Regiment, which included 24 75mm artillery pieces, 15 light tanks, approximately

35

�100 .50-cal heavy machine guns, 15 81mm heavy mortars, and about 30 dual-purpose AA and

coastal defense guns. These complimented existing 141mm mortars, naval AA guns, and rocket

launchers (Table 1). Nor did it account for two 200mm anti-boat guns, one on Bloody Nose

Ridge the other on Ngedebus (Denfeld 1988:46). When combined with the formidable and

extensive cave system, the Japanese defensive position on Peleliu was both strategic and well

executed.

Table 1. Estimated Japanese Weapons on Peleliu and Ngedebus

Weapon Type

Rifles 7mm

Grenade Discharger

Light Machine Gun 6.5x50mm

Heavy Machine Gun .50 cal

13mm AT (anti-tank)

20mm AT

37mm AT

70mm Howitzer

81mm Mortar

75mm Field Artillery (FA)

105mm Howitzer

Tanks

Flame Throwers

20-40mm AA

105-127mm Dual Purpose (DP)

3” – 5” DC

20-40mm Anti-Boat Guns

Pillboxes

Blockhouses

Number

5,066

171

200

58

7

3

9

7

55

12

4

12

2

99

4

5

2

17

12

1st Marine Division Operation Plan 1-44, August 1944:15.

Pre-Assault Bombardment

The three-day pre-invasion carrier and naval bombardment of Peleliu began on September 6,

1944. Despite previous shelling by both aircraft and warships, naval pilots encountered heavy

AA activity. “Much time and many bombs were expended before return fire was sufficiently

reduced to let us get down low for close observation and detection of small but important

enemy positions, bivouac areas, etc.” (Report of R.L. Kibble, Commander of Air Group Thirteen,

September 6-16, 1944, dated November 25, 1944, quoted in Garand and Strobridge 1971:102).

The pre-assault element of the Palau operation began at 0530 on September 12, 1944, when

the first echelon of the Escort Carrier Group, under the command of Rear Admiral George H.

Forte, and two groups comprising the Peleliu Fire Support Group, under the commands of Rear

36

�Admiral W.L. Ainsworth and Vice Admiral Jesse Oldendorf, started firing on Peleliu and Angaur.

The pattern was two hours of naval gunfire then two hours of carrier-based aircraft attack

(Table 2). This alternating pattern continued without pause for 72 hours. Oldendorf was so

pleased with the bombardment that on September 14, 1944 he reported that there were no

more targets, a comment he would later regret. During the bombardment, the warships used

519 rounds of 16-inch shells, 1,845 rounds of 14-inch shells, 1,427 rounds of 8-inch shells, 1,020

rounds of 6-inch shells, and 12,937 rounds of 5-inch shells, a total of 2,255 tons of ammunition.

While the shelling transformed the interior of Peleliu from heavy jungle cover to a denuded

harsh environment, the carefully prepared Japanese defenses were largely unscathed. Troops

and artillery sheltered in the prepared caves, some of which had iron blast doors, and the

defenders suffered few casualties (Garand and Strobridge 1971:103-104).

Table 2. Ships Involved in the Naval and Aerial Bombardment

Type

Battleship (BB)

Heavy Cruiser (CA)

Light Cruiser (CL)

Destroyer (DD)

Escort Carrier (CVE)

Light Aircraft Carrier (CVL)

Aircraft Carrier (CV)

Number of Ships

5

4

4

14

10

4

4

Group

Fire Support

Fire Support

Fire Support

Fire Support

Carrier

Carrier

Carrier

Based on Garand and Strobridge 1971:103.

During this part of the operation, the Kossol Passage Detachment began minesweeping

operations along the approaches to the designated transport and fire support areas. They also

cleared the Kossol Passage, the roadstead where the support ships carrying supplies, stores,

and ammunition waited (Garand and Strobridge 1971:103).

The Assault

At 0530 on September 15, the fire support group under the command of Admiral Oldendorf,

opened fire in preparation for the first assault waves. On board the amphibious command

ships, USS Mount Olympus and Mount McKinley, the Navy and Marine commanders observed

the complicated landing operation, while the staff of the 1st Marine Division operated from the

assault transport USS DuPage (Garand and Strobridge 1971:107). The scheme of maneuver

called for landing three regimental combat teams (RCTs) in formation across a 2,200-yard-wide

beachhead, followed by a drive straight across the island to seize the airfield, divide the

Japanese forces, and cut the island in half (Figure 11). This meant that each participant in the

operation was dependent on the others to reach their positions according to a tight schedule.

37

�The ships involved in the delivery of the troops and equipment to their designated stations

included the large ocean going LSDs (landing ship, dock) with a dry dock to transport and launch