Journal of Economic Growth, 4: 81–111 (March 1999)

c 1999 Kluwer Academic Publishers, Boston.

°

Economic Growth and Political Regimes

J. BENSON DURHAM

Columbia University, New York, NY 10027

The absence of continuous regime type measures that focus on institutions rather than outcomes besets studies on

whether democratic or authoritarian regimes grow faster. Additional shortcomings include the failure to consider

development stages and the erroneous endogenous specification of regimes. Given panel data on 105 countries from

1960 to 1989, the effective party/constitutional framework measure does not correlate with growth or investment

in the total sample. But considering development levels, some evidence indicates that discretion decreases growth

in advanced areas, and, contrary to theory, inhibits investment in poorer countries. Also, single-party dictatorships

have higher investment ratios but do not grow faster than party-less regimes.

Keywords: growth, investment, regimes

JEL classification: 040, 057

1.

Introduction

Do dictatorships or democracies better promote economic growth? Given strong normative

preferences for both democracy and development, this political economy question receives

much deserved attention among scholars as well as policy entrepreneurs. After considerable

debate and econometric evidence, however dubious, an influential literature review concludes that the inquiry “is wide open for reflection and research” (Przeworski and Limongi,

1993, p. 66). To begin, one must first inquire how regimes, which refer to the methods

politicians must use to gain and maintain control of the state, affect growth. The key causal

institutional characteristic of regimes is the degree of policymaker discretion or freedom

of action that such methods give sovereigns. Some social scientists recommend extensive

sovereign discretion, while others endorse limited government. Discretion is the crux of

both arguments.

Persistent problems in econometric studies warrant additional evaluation. First, and perhaps most important, the literature does not consider continuous proxies for regime type that

focus more acutely on institutions as opposed to outcomes. Given that arguments rest on the

continuous underlying concept of policymaker discretion, proxies for political regime type

should also be continuous and thereby distinguish among democracies and dictatorships,

hitherto a residual econometric category. Furthermore, considering the practical policy

implications of the debate, measures should capture a continuum of discretion with respect

to meaningfully serviceable institutional concepts, such as the number of effective political parties and constitutional frameworks, rather than outcome proxies that economists

routinely employ. Therefore, this article presents an alternative regime type proxy to com-

�82

DURHAM

plement existing measures that is continuous rather than discrete and objective rather than

subjective.

But before applying a measure that focuses more acutely on institutions, two additional

issues germane to this econometric question should be thoroughly outlined. First, existing

tests do not explicitly evaluate the tacit consensus that dictatorship is more useful in less

developed nations, while democracy is more suitable in advanced countries—a critical

addendum that posits ambiguous results for universal samples. Therefore, unlike previous

studies, the sample is divided according to levels of GDP per capita to approximate the

developmental circumstances under which discretion is either beneficial or debilitating.

Second, some social scientists erroneously suggest that the inquiry is intractably fraught

with simultaneity and/or survival bias. Rather, given the routine distinction between the

level and rate of economic development, the estimation problem is collinearity between

initial GDP per capita and regime type.

The remainder of Section 1 reviews the two competing perspectives. Section 2 outlines

the effective party/constitutional framework measure. Section 3 discusses additional econometric issues—namely, development stages and simultaneity and/or survivor bias, which

must be addressed before econometric estimation. Section 4 presents the econometric results for growth and investment in the total sample, across eight per capita GDP breaks, and

exclusively in authoritarian regimes. Section 5 concludes.

1.1.

The Authoritarian View

Authoritarian regimes bestow considerable discretion on sovereigns and are by definition

not susceptible to the “political business cycle.” In Kurth’s estimation, dictatorships more

effectively stimulate growth and investment by suppressing labor unions, wages, and consumer demand—very unpopular measures (1979, p. 334; see also March, 1988; Sirowy and

Inkeles, 1990). Put simply, democratic governments that wish to maximize tenure must

respond to popular demands for spending and consumption. Assuming considerable sacrifices associated with capital accumulation and inherently myopic voters, political parties

simply cannot simultaneously advocate sacrifices and win elections (Rao, 1984–85, p. 75;

see also Weede, 1983, p. 36).

Gershenkron’s early contributions are also illustrative and particularly relevant to historical development stages. Writing in contrast to the Marxist view that established industrial

countries foreshadow development for less developed areas, he argues that “the advantages

of backwardness,” the combination of cheap labor and technological backlogs, can accelerate development in poorer countries (1962, p. 8). Therefore, the rate of development differs

across cases, and the political consequences are clear—namely, the greater the initial backwardness, the greater the required state intervention necessary to affect industrialization.

Extensive state intervention, in turn, instinctively relates to authoritarian government. Effective policies require great sacrifice, and policymakers must have sufficient discretion to

command such (myopic) hardship from the subject polity.

An important subtlety to this view is that authoritarian rule is perhaps a necessary but

certainly not a sufficient condition for industrialization. That dictators do not always extol

discipline is not lost on Gerschenkron (1962, p. 20). Seemingly, regimes must be strong

�ECONOMIC GROWTH AND POLITICAL REGIMES

83

enough to affect investment, yet that very strength can potentially inhibit resource allocation

and accumulation. This foreshadows the alternative view that democracy better fosters

development.

1.2.

The Democratic View

Unlike dictatorships, democracies limit sovereign discretion and thereby more effectively

promote economic growth because they solve the “credible commitment problem.” According to North and Weingast, if subjects suspect that sovereigns might alter property rights to

extract rents, they will have less incentive to invest. Therefore, sovereigns cannot merely

establish rights: they must also make subjects believe ex ante that they will not renege on

their commitments (1989, p. 803). In contrast to authoritarian regimes, democracies check

arbitrary rule, perhaps more effectively limit corruption, and thereby preserve established

property rights. As Scully suggests, legal uncertainties increase transaction costs, and capital accumulation increases with more secure legal claims on property and income (1988,

p. 653; see also Pourgerami, 1991, pp. 189, 194; Kohli, 1986, p. 165; Wittman, 1989,

pp. 1397, 1411).

Przeworski and Limongi reject this logic and consider the argument that democracy

protects property rights a “recent” and “far-fetched invention” (1993, p. 52). They list

Mackintosh, Ricardo, Macaulay, and Marx, who all suggest that extending suffrage to

lower classes threatens private property. One might add Laske to this list, but the recent

nature of the assertion that democracy ameliorates the credible commitment problem does

not make it wrong. While Przeworski and Limongi argue that North does not directly relate property rights to democracy, Olson (1993), whom the authors neglect in this context,

persuasively links the “state of nature,” sovereigns, property rights, and democracy. Very

briefly, Olson argues that distortionary taxes are lower in democracies compared to dictatorships. In democracies, both the incumbent and the majority receive wealth transfers,

as such governments redistribute some receipts to the constituents, while autocrats simply

indulge themselves.1 Coupled with the succession problem in dictatorships that supposedly debilitates long-run commitments, democracies are therefore more efficient because

at least some portion of the polity, the majority, also receives rents. Democratic consent

limits sovereign discretion, and therefore policymakers spread wealth beyond (presumably

kleptocratic) sovereigns to subjects.2

2.

Toward a Continuous Regime Type Measure with Institutional Referents

However efficient alternative regimes, arguments for either democracy or dictatorship ultimately rest on notions about sovereign constraint. The substance of policy notwithstanding,

regimes should either give sovereigns the freedom of action to take benevolent measures or

restrain them from malevolent actions. This central concept of discretion is a continuous

and not a dichotomous variable, as many studies dubiously conceive.

Also, the question has considerable ex ante proscriptive relevance: considering the ubiquitous preference for development, should new regimes in Congo, Indonesia, and Nigeria,

�84

DURHAM

for example, facilitate or inhibit executive action? Unfortunately, existing measures used

in econometric studies do not adequately capture the continuous nature of executive discretion and objectively measurable institutions that distinguish regimes. Of course, existing

scales, which influential studies such as Kormendi and Meguire (1985), Grier and Tullock

(1989), and Barro (1996) employ, are ordinal values in raw form, but these ex post measures

do not isolate specific institutions or address key constitutional choices relevant to policy

entrepreneurs.

2.1.

Common Econometric Measures

To begin a brief review of common measures, Jaggers and Gurr (1995) provide a useful discussion of the plethora of quantitative expressions of regime type. These include data sets

such as their own that are based on subjective criteria, including historical monographs,

and more objective data sets such as Vanhanen’s, which relies exclusively on electoral

data.3 Briefly, Jaggers and Gurr’s Polity III measures employ nine indicators of “institutionalized authority characteristics.” These indicators, in turn, endeavor to capture three

concepts—“the influence dimensions of authority,” “the recruitment of chief executives,”

and “government structure” (Jaggers and Gurr, p. 470). Another measure of regime type,

perhaps the most popular, is Gastil’s Freedom House dual indices of political and civil rights.

Political rights refer to the “capacity of individuals to participate freely and effectively in

the selection of policymakers and binding decision rules affecting the national, regional,

and local community.” Civil rights “are defined by the freedom of individuals to develop

views, institutions and personal autonomy apart from the state” (Jaggers and Gurr, p. 474).

Turning to validity and estimation, like Jaggers and Gurr’s, the Gastil indicators are

inherently subjective, and time-series validity of these indices is highly questionable. Even

the Freedom House judges readily admit that “changes in information and judgment since

1973 make many ratings not strictly comparable from year to year” (Gastil, 1987, p. 53).4

Validity aside, one might employ the ordinal forms to capture the degrees of executive

discretion, but the unit changes in both variables have little substantive meaning. As Clague

et al. note, the indices capture outcomes of processes rather than define specific features of

a democratic political system (1996, p. 251). They do not refer to the institutions involved

in, to borrow DiPalma’s (1990) phrase, “crafting democracies” ex ante. Few economists

or political scientists have an intuitive understanding of how, say, a country with a measure

of “1” differs from another with a measure of “5” on the twenty-one-point Polity III scale.

More important, policy entrepreneurs cannot readily replicate such outcomes in, say, Congo,

Indonesia, or Nigeria.

2.2.

An Alternative Proxy: The Effective Party/Constitutional Framework Measure

Given these practical shortcomings of common outcome measures, a useful alternative

measure of regime type should capture more servicable concepts that relate to the critical

notion of discretion. Furthermore, such a proxy should be continuous rather than discrete

without losing its intuitive appeal and empirical relevance. This section outlines a measure

�ECONOMIC GROWTH AND POLITICAL REGIMES

85

that endeavors toward these ends. The alternative incorporates the number of effective

political parties in government and the position of the executive vis-à-vis legislative offices.

2.2.1. Determination of the Existence and Number of Effective Parties The number of

“effective” political parties in government constrains policymakers in two respects, within

and without the governing party. Both internal policy discipline and external party competition constrain policymakers. The first obtains if a party exists in government. The second

obtains if competitive elections allow additional parties in government. The fewer parties

in government, the more discretion the regime has in policymaking.

Before one can determine the “effective” number, one must define “political party.”5

This stipulative definition draws from Ranney (1968), Duverger (1954), LaPalombara and

Weiner (1966), Von Der Mehden (1964), and Huntington (1968) and includes three essential elements. First, a party refers to an organized group that describes itself as such and

seeks to control the state. Whoever occupies the executive office in government must be

a member of such a party or the regime is party-less.6 Second, a party must compete in

elections, competitive or otherwise. Elections, even noncompetitive contests, are critical

because such practice indicates that the party attempts to channel or mobilize the polity,

which Huntington (1968) emphasizes in the context of political development. Third, a

party must exhibit organizational continuity. That is, the life span of the party does not

depend on its founders. The party must either continue after the demise of its founders or an

effective change in leadership must occur.7 This consideration measures the relative institutionalization of parties and, especially among authoritarian regimes, distinguishes them

from more traditional political organizations. The stipulative definition applies irrespective

of the number of effective parties in the regime. Also, given the emphasis on economic

policymaking, the definition refers exclusively to the “ ‘party-in-the-government’—persons

holding public legislative and executive offices who sometimes act with solidarity on certain

matters” (Ranney, 1968, p. 154).

Recall that proponents of the authoritarian model suggest that discretion is beneficial. If

ideal parties mobilize or channel political sentiment from the entire polity, then the more embedded party would similarly resist unpopular measures for growth and investment. Thus,

policymakers in one-party dictatorships should enjoy less discretion than their counterparts

in party-less regimes. As Huntington suggests, “Patriot Kings” and “conservative nonroyal

leaders” like Sarit, Ayub Khan, Franco, or Rhee view political parties as divisive because

they challenge authority and complicate unification and modernization. More important,

the bureaucracy that executes economic policy views political parties suspiciously because

they introduce irrational corruption into the pursuit of unproblematic goals, such as growth

(Huntington, 1968, pp. 403–404). Thus, even in an autocratic context, party discipline

constrains dictators and limits their ability to pursue unpopular measures.8 Considering the

general authoritarian view that discretion is beneficial, single-party dictatorships should

grow more slowly than their party-less counterparts. Conversely, assuming the general

democratic view that discretion is malevolent, single-party regimes should grow faster.9

Given the existence of a party, the second step is to determine the number of “effective”

parties in government, which produces subtypes of democracies. Following Laakso and

Taagepera, who do not apply their measure to economic outcomes, the “effective number

�86

DURHAM

of parties is the number of hypothetical equal-size parties that would have the same total

effect on fractionalization of the system as have the actual parties of unequal size” (Laakso

and Taageper, 1979, p. 4). The effective number N is the inverse of the sum of the squared

fractured seat shares for each party in government.10 That is,

N = Pn

1

l=1

Pl2

,

(1)

where N is the number of effective parties, and Pl represents the share of the total number of

parliamentary seats that the lth party holds. Therefore, if the share of seats is equal among

all parties, then N equals the actual number of parties n. If, in the authoritarian case, one

party competes in a noncompetitive election and seats are distributed accordingly, then N

equals one, the actual number of parties.

2.2.2. Incorporation of the Constitutional Framework With respect to policymaking

discretion, in addition to the raw number of effective legislative parties, the constitutional framework in which those parties exist is very important. Accordingly, the effective

party/constitutional framework proxy modifies Laakso and Taageper’s original formulation

(1) to incorporate the relative position of the legislative vis-à-vis the executive branch, which

is a critical locus of economic policy implementation if not formulation. This modification endeavors to more comprehensively capture governmental discretion. The distinction

isolates “parliamentary” from other categories such as “presidential,” “semipresidential,”

“mixed,” and “authoritarian” regimes.

In Stepan and Skach’s terms, a “pure parliamentary regime” is a system of mutual dependence, where parliamentary majorities must support executive power, and the executive

office can dissolve the legislature and call elections (such as in Italy, Japan, Jamaica, or the

United Kingdom). On the other hand, a “pure presidential regime” is a system of mutual independence, where both the executive and legislative powers have fixed electoral mandates

that are the sole sources of legitimacy (such as in Columbia, Costa Rica, the United States,

or Venezuela) (Stepan and Skach, 1993, pp. 3–4, emphasis added). Similarly, unelected

dictators, who may or may not permit the existence of a multiparty parliament, occupy the

executive branch, and the system exhibits exclusive independence.

In short, the raw number of effective parties captures discretion for parliamentary regimes,

but the figure adjusts for nonparliamentary categories because the executive branch in such

cases typically accommodates only one party. That is, given that “legitimacy” exclusively

derives from the legislature in a parliamentary regime, the raw effective parties measure (1)

is the proxy. But for systems of mutual dependence or exclusive independence the measure

is the mean of the number of parties across the executive and legislative branches, as in

Pn1

N=

l=1

Pl2

+ Pn1

e=1

2

Pe2

,

(2)

where Pe , the number of effective political parties in the executive branch, is equal to one.11

�ECONOMIC GROWTH AND POLITICAL REGIMES

2.3.

87

Some Advantages and Disadvantages of the Effective Party/Constitutional

Framework Measure

This section briefly outlines the correlation matrix of alternative measures, notes more

specific examples with respect to Table 1, and discusses the relative appropriateness of outcome versus institutional measures with respect to this econometric issue. In addition to the

useful ordinal distinctions among democracies and dictatorships, which common outcome

alternatives do not produce, the effective party/constitutional framework measure complements common proxies because it more directly relates to the institutional characteristics

of regimes. Such is not to argue that outcome based proxies have no purpose. Rather,

an alternative that focuses more acutely on institutions should more directly address the

debate’s applicable implications.

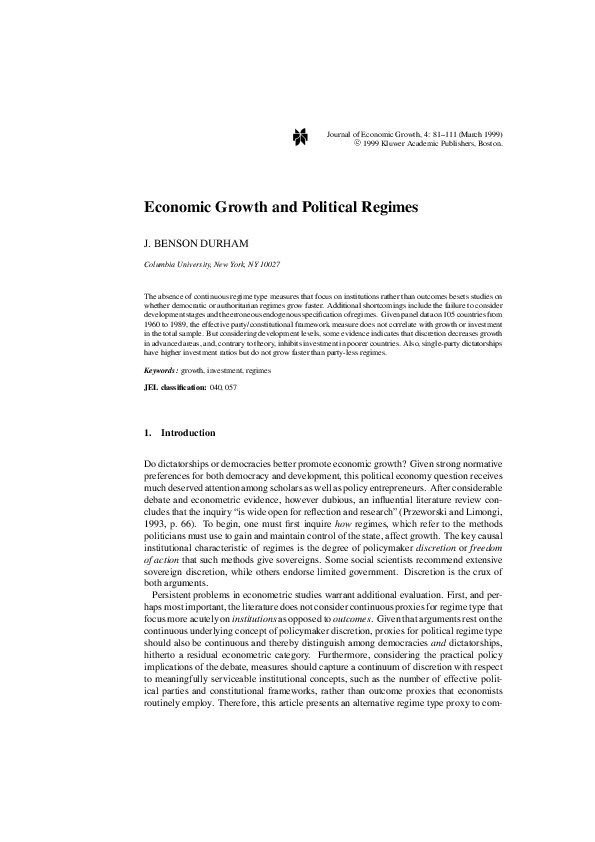

With respect to the reliability of the measure, the alternative proxy correlates comparatively highly with more common measures. The effective party/constitutional framework

measure correlates closely with both the Polity III (.727) and Gastil (.720) measures, but

not as closely as the Polity III and Gastil indices (.918).12 Turning to examples listed in

Table 1, very few cases diverge considerably in rank. For example, the fifteen countries

with the greatest number of effective parties are all clearly classified as democratic according to both the Gastil and Polity III indices.13 Conversely, the thirty-nine single-party and

party-less regimes (as well as averages in between) are all dictatorships in a dichotomonous

transformation.

With respect to validity, the alternative measure for regime-type is not necessarily a better

proxy for “democracy” in general. As Jaggers and Gurr (1995) clearly suggest, different

measures of regime-type are effective for different research purposes. If the only objective

is to classify regimes, a true measure should include institutions and outcomes, both of

which can be useful. For example, the effective party/constitutional framework measure

is probably not as effective as the Gastil scale at measuring human rights abuses and civil

rights, a distinct scholarly endeavor from explaining growth. “Democracy” is a slippery

concept with several meanings.14

Given this particular econometric question, the effective party/constitutional framework

measure is useful in two aspects. First, continuous expression of the proxy not only maintains its intuitive appeal, unlike the outcome measures, but also makes key distinctions

where the Gastil and Polity III measures do not. For example, with respect to democracies,

the rankings in Table 1 show considerable variation in the effective party/constitutional

framework measure among the most advanced pluralistic democracies, while the Gastil and

Polity III produce identical ordinal values for fourteen (“1”) and twenty-two (“10”) countries, respectively. The outcome measures assign a considerable population of democratic

countries with indistinguishable values, while the alternative institutional measure quantitatively differentiates party systems and presidential and parliamentary democracies.15

In addition to the continuous differentiation of democracies, to distinguish between authoritarian regimes is an important objective because econometric studies exclusively consider

it a residual category. For example, Barro writes that “the theory that determines which kind

of dictatorship will prevail is missing” (1996, p. 2). Similarly, Przeworski and Limongi cite

Sah’s contention that economic performance varies more dramatically among dictatorships

�88

DURHAM

Table 1. Regime-type measures: Effective party/constitutional framework, Gastil, and Polity III: five-year

average, 1960–1989.a

Country

Belgium

Denmark

Netherlands

Papua New Guinea

Israel

Iceland

Italy

Norway

Sweden

Finland

West Germany

Japan

Switzerland

Ireland

Australia

Thailand

Sir Lanka

Turkey

Canada

Austria

France

Mauritius

United Kingdom

India

Cyprus

Greece

New Zealand

Venezuela

Argentina

Costa Rica

Guatemala

Colombia

South Korea

Jamaica

Ecuador

Bolivia

Trinidad and Tobago

Nicaragua

El Salvador

United States

Brazil

Gambia

Philippines

Dominican Republic

Panama

Effective

Party/

Constitutional

Framework

Measure

4.885

4.734

4.540

4.521

4.133

3.805

3.530

3.347

3.254

3.085

2.997

2.712

2.681

2.609

2.491

2.396

2.372

2.356

2.314

2.258

2.243

2.174

2.105

2.080

2.076

2.025

1.970

1.930

1.738

1.714

1.564

1.533

1.527

1.513

1.497

1.492

1.488

1.481

1.468

1.462

1.447

1.441

1.436

1.417

1.409

a. The Gastil measures begin in 1973.

(Rank)

Gastil

Ordinal

Measure

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

1.000

1.000

1.000

2.000

2.125

1.000

1.375

1.000

1.000

1.750

1.250

1.250

1.000

1.125

1.000

3.000

3.500

2.750

1.000

1.000

1.500

2.375

1.000

2.375

2.125

1.667

1.000

1.750

1.500

1.000

3.000

2.625

5.167

2.125

3.000

3.500

1.750

4.250

3.000

1.000

3.500

2.500

4.000

2.167

5.375

(Rank)

Polity III

Ordinal

Measure

(Rank)

1

1

1

26

27

1

18

1

1

23

16

16

1

15

1

38

42

37

1

1

19

31

1

31

27

22

1

23

19

1

38

35

72

27

38

42

23

55

38

1

42

33

51

30

74

10.000

10.000

10.000

10.000

9.233

10.000

10.000

10.000

10.000

10.000

10.000

10.000

10.000

10.000

10.000

−0.600

5.760

8.667

10.000

10.000

7.560

9.400

10.000

8.433

9.400

7.400

10.000

8.400

3.500

10.000

−1.650

7.533

−5.900

10.000

2.680

−1.450

8.300

−6.250

0.900

10.000

−3.000

9.400

0.733

0.400

−3.600

1

1

1

1

26

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

1

47

35

27

1

1

32

23

1

28

23

34

1

29

38

1

52

33

64

1

39

51

30

70

41

1

54

23

42

44

57

�89

ECONOMIC GROWTH AND POLITICAL REGIMES

Table 1. Continued.

Country

Peru

Paraguay

Zimbabwe

Botswana

Guyana

Malaysia

Bangladesh

South Africa

Uruguay

Chile

Sierra Leone

Egypt

Indonesia

Mexico

Portugal

Taiwan

Zambia

Poland

Senegal

Honduras

Singapore

Kenya

Hungary

Liberia

Yugoslavia

USSR

Czechoslovakia

Bulgaria

Sudan

Togo

China

Romania

Mozambique

Cameroon

Congo

Tunisia

Algeria

East Germany

Malawi

Zaire

Spain

Pakistan

Syria

Iraq

Benin

Myanmar

Mali

Ghana

Haiti

Effective

Party/

Constitutional

Framework

Measure

1.398

1.384

1.377

1.369

1.367

1.351

1.346

1.340

1.310

1.300

1.225

1.196

1.150

1.145

1.128

1.126

1.087

1.079

1.071

1.030

1.005

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

1.000

0.989

0.925

0.879

0.755

0.750

0.750

0.667

0.527

0.502

(Rank)

Gastil

Ordinal

Measure

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

67

86

87

88

89

90

90

92

93

94

3.833

4.625

4.750

2.500

3.750

3.833

4.000

5.500

3.750

4.000

5.000

4.500

5.125

3.750

1.500

4.625

5.125

4.833

4.125

3.500

4.625

5.250

4.833

5.500

5.375

6.250

6.500

7.000

5.500

6.125

6.333

6.667

6.500

5.750

6.500

5.000

5.750

6.500

6.375

6.500

2.667

4.625

6.333

6.833

6.750

6.833

6.333

6.000

6.500

(Rank)

Polity III

Ordinal

Measure

(Rank)

49

57

61

33

46

49

51

76

46

51

65

56

69

46

19

57

69

62

54

42

57

73

62

76

74

87

92

104

76

86

88

99

92

82

92

65

82

92

91

92

36

57

88

101

100

101

88

84

92

2.440

−7.800

0.100

10.000

−3.100

7.867

−5.400

4.000

4.350

−0.900

−4.680

−5.400

−6.880

−4.800

0.400

−7.400

−6.240

−6.067

−3.360

0.500

−2.000

−5.520

−6.200

−6.200

−6.200

−6.520

−6.950

−7.000

−7.000

−7.000

−7.133

−7.400

−7.600

−7.640

−8.000

−8.240

−8.600

−9.000

−9.000

−9.000

−0.720

−0.833

−8.500

−7.100

−6.500

−7.250

−7.000

−5.700

−9.200

40

90

46

1

55

31

60

37

36

50

58

60

73

59

44

85

69

65

56

43

53

62

66

66

66

72

74

75

75

75

83

85

87

89

92

94

97

98

98

98

48

49

96

82

71

84

75

63

101

�90

DURHAM

Table 1. Continued.

Country

Rwanda

Niger

Uganda

Nepal

Lesotho

Iran

Central African Republic

Jordan

Kuwait

Bahrain

Swaziland

Effective

Party/

Constitutional

Framework

Measure

0.500

0.333

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

(Rank)

Gastil

Ordinal

Measure

95

96

97

97

97

97

97

97

97

97

97

6.000

6.500

7.000

4.833

5.125

5.500

6.833

5.500

5.000

5.000

5.500

(Rank)

Polity III

Ordinal

Measure

(Rank)

84

92

104

62

69

76

101

76

65

65

76

−7.000

−7.000

−7.000

−7.600

−7.950

−8.100

−8.333

−9.300

−9.600

−10.000

−10.000

75

75

75

87

91

93

95

102

103

104

104

than among democracies, largely because some dictators are constructively “developmentalist,” while others are simply “thieves.” Similar to Barro (1996) and Alesina et al. (1996),

they lament that “we have no theory that would tell us in advance which we are going to

get” (Przeworski and Limongi, 1993, p. 65). By quantitatively distinguishing authoritarian

regimes, this measurement begins to address the lack of testable hypotheses. The effective

party distinction does not purport to truly distinguish benevolent technocratic authoritarian regimes from malevolent kleptocratic despots. But given its crucial link to executive

discretion—party-less regimes enjoy more discretion than single-party dictatorships—the

proxy at least provides an objective hypothesis on which type should outperform, depending

on whether one generally espouses the authoritarian or democratic view of development. If

discretion is benevolent, then party-less dictatorships should grow faster, otherwise, checks

on arbitrary capriciousness in single-party authoritarian regimes should lead to better performance. In short, the effective party/constitutional framework measure makes a first cut

at objective econometric distinctions and therefore testable hypotheses regarding subtypes

of both democracies and dictatorships.

A second advantage regards its more explicit institutional focus. While outcome measures

address a broader conception of democracy and a fuller spectrum of freedoms, an institutional proxy focuses more acutely on regime type characteristics that relate to the origins

of government policymaking and constitutional framing. Whether democracies or dictatorships grow faster is not a purely academic inquiry. The effective party/constitutional framework measure complements common outcome proxies because the former more directly addresses the question, perhaps initially motivated by North and Thomas (1973), as to whether

social scientists can identify objectively measurable institutions that promote growth.

Policy entrepreneurs cannot plausibly construct a polity to instantaneously possess some

value on an ordinal outcome scale. They cannot directly compel such results, but they

can craft procedural institutions.16 With respect to the political parties, the first component,

the alternative measure ultimately relates to the constitutional choice in voting procedures

�ECONOMIC GROWTH AND POLITICAL REGIMES

91

among first-past-the-post, proportional representation and various combinations thereof.

Also, some dictators have the option to surround themselves with political party machinery.

Furthermore, with respect to the second component, constitutional frameworks ultimately

refer to serviceable stipulations—actual choices regarding the relationship between the executive and legislative government functions. In short, economists and policy entrepreneurs

alike can supplement outcome proxies with institutional measures that have more concrete

empirical and applicable referents.

2.4.

Hypotheses: Linear and Nonlinear Forms

The continuous nature of the effective party/constitutional framework measure enables tests

of three hypotheses.17 First, the relationship between the number of effective parties and

growth might be linear, which perhaps becomes less intuitive after certain values in the

independent variable. One might question whether there is a monotonic effect of parties on

growth after some threshold. Put differently with respect to specific examples, the (beneficial or deleterious) effect of the 4.1 effective parties in Israel compared to the 2.1 in the United

Kingdom might be less pronounced than the approximately equivalent difference between

the United Kingdom and a party-less regime such as Jordan. Thus, possibility of diminishing marginal positive or negative effects recommends investigating curvilinear functional

forms. Preserving the direction of a given hypothesis, linear-log forms test whether the

effect on economic growth becomes less pronounced or tails off after some democratic (or

discretion) threshold. This form suggests that the most pronounced effect occurs form zero

to one effective party, which might not as accurately reflect this nonlinearity.

In contrast to the linear and linear-log forms, the effect of political regimes might not

be unidirectional. Another curvilinear form evaluates a more balanced view. A concave

quadratic form tests whether the effect on economic growth is positive at an increasing

rate approaching a critical value of effective parties and then tapers increasingly downward.

More substantively, the quadratic form suggests that governing institutions must restrain

sovereigns, compel a credible commitment to property rights, but also restrain them from

wasteful consumption. A certain level of party development or competition ensures commitment, but too many parties make the state vulnerable to demands for consumption.18

One might expect that in terms of the effective party/constitutional framework measure, the

critical maximum might be between one and two parties, which should reflect the existence

of a credible opposition but yet sufficient discretion for unpopular (and presumably ultimately benevolent) measures. Less intuitively but still quite possibly, a critical maximum

between, say, three or four parties would suggest that democracies generally outperform

dictatorships, with the exception of the most fragmented systems.

3.

Additional Econometric Issues: Developmental “Stages” and Simultaneity and/or

Survivor Bias

Before econometric analysis of the effective party/constitutional framework proxy, two

crucial issues that studies fail to address must be outlined. The first regards the possibility

that the efficacy of particular regimes is circumstantial rather than universal, as no study tests

whether dictatorships (democracies) are more efficient in less (more) developed areas. The

�92

DURHAM

second concerns the misguided critique that studies (Kormendi and Meguire, 1985; Grier

and Tullock, 1989; Barro, 1996) are prone to simultaneity and/or survivor bias. Contrary

to this sweeping criticism (Brunetti, 1997; Przeworski and Limongi, 1993, 1997), given

the routine distinction between the level and rate of economic development, regime type is

exogenous to growth.

3.1.

The “Stages” of Economic Development

The literature fails to test persuasive but implicit notions about the “stages” of development.

Again, a given sovereign must be strong enough to protect property rights and prevent the

anarchical state of nature, yet institutions must also restrain them from abusing monopoly

power for unproductive ends. These paradoxical requirements are important, yet debaters

typically emphasize only one component of this relationship between sovereign and subject

and make universal assertions. But both characteristics might seemingly have organizational advantages under certain circumstances,19 and unfortunately growth econometrics

render no explicit evaluations of possible conditions under which discretion is beneficial.

Drawing on sweeping generalizations of economic history, an historical growth trajectory illustrates more implicit hypotheses about the conditions under which some regimes

are optimal. Consider Kurth’s (1979) outline of industrial phrases and the concomitant

political outcomes. These successive phases include “the production of non-durable consumer goods, intermediate and capital goods, and consumer durables” (Kurth, 1979, p. 319).

Briefly, the first and last stages are complementary for democracy because investment requires “relatively modest” sums of capital in relation both to the available stock and the

large amount required for industrial development (Kurth, 1979, p. 330). Some scholars,

then, Gerschenkron certainly included, instinctively associate the greater amount of capital

required and attendant extensive state intervention during the second phase with authoritarianism.

On the one hand, most agree that today the wealthiest countries are democracies (Przeworski and Limongi, 1993, p. 62). Perhaps consequently, few scholars explicitly argue

that advanced democracies, such as the United States or Japan, would grow faster if they

were authoritarian.20 This largely conforms to Kurth’s suggestion that democracies are

more efficacious in the latest phase. Conversely, even in the paradigmatic case of liberal

nineteenth-century Great Britain, few economic historians argue that the process of heavy

industrial development occurred under truly democratic auspices. Granted, this assertion

depends on one of many possible operationalizations of democracy, but if procedural universal suffrage and full working-class inclusion are indices, then the generalization largely

holds. For example, Schwarz (1992) suggests that OECD countries industrialized under

less than liberal political tutelage, while democratization followed heavy industrial development. Even Moore (1966), who differentiates democratic, fascist, and communist

development, notes that industrialization proceeded universally without subject approval.

He writes, “There is no evidence that the mass of the population anywhere has wanted an

industrial society. . . . At bottom of all forms of industrialization so far have been revolutions

�ECONOMIC GROWTH AND POLITICAL REGIMES

93

from above, the work of a ruthless minority” (p. 506). This hardly suggests a democratic

option in the early phases.

On the other hand, few economic historians counterfactually argue that heavy industrial development would have been more efficient under democratic auspices. Even Kurth’s

sweeping trajectory aside, the supposed virtues of democracy seem more relevant in comparatively advanced stages of development. The democratic view largely assumes a modicum

of wealth, existing entrepreneurs, and readily available capital. In more destitute countries,

there are simply fewer enterpreneurs and households with the wherewithal to invest, and the

credible commitment problem is perhaps comparatively less pressing. In poor countries,

one might argue that the shear dearth of capital supersedes the commitment to credible

property rights. After all, the establishment of property rights generally coincides with the

development of property (capital) itself. Put differently, the ratio of unskilled labor to the

total human capital stock decreases with development (national income), which implies that

dictatorships, given their purported advantage in compelling savings from underprivileged

classes, become increasingly ineffective and costly.

This review does not suggest that the literature explicitly conforms to Kurth’s outline, but

neither do scholars evaluate the tacit contention that dictatorship is more efficacious during

heavy industrial development or that democracies better govern advanced states. Critics

and defenders of each regime type talk past one another if one considers (very) long-term

growth and development. Therefore, one might expect that in the universal sample, the effect

of regime type should be ambiguous because the negative effect of discretion in advanced

countries vitiates the positive impact in poorer areas. Such consensus, however implicit,

invites explicit evaluation.

3.2.

Simultaneity Bias, Survival Bias, or Collinearity?

Just as many social scientists argue that political regime type affects economic development,

many others also advance the notion that economic development affects political regime

type. Similar to Brunetti’s (1997) discussion, Przeworski and Limongi’s (1993) conclusion

is that the evidence of simultaneous determination and survival bias between political regime

type and development “suffices to render suspect any study that does not treat regimes as

endogenous.”21 This profound criticism applies to Kormendi and Mequire (1985), Grier

and Tullock (1989), and Barro (1996). But briefly, an important yet routine distinction

between the level and rate of economic development shows that the estimation problem

involves neither simultaneity nor survival bias but collinearity between the initial level of

income and regime type.22

Again, the debate concerns whether regime type determines growth. That is, either dictatorships or democracies exhibit better economic performance. To suggest that economic

development in turn affects regime type necessarily implies that development determines

the manifestation of either democracy or dictatorship. Economic development determines

a particular regime type. Brunetti (1997) as well as Przeworksi and Limongi (1993, 1997)

do not satisfactorily evaluate the distinct (purported) effects of the rate and level of economic development. Whether the rate, level, or both aspects of economic development help

determine political regime type implies different econometric problems and solutions. If

�94

DURHAM

the level of development determines regime type, a regression that explains growth as some

exogenous function of regime type should control for the initial level of development, which

in turn should exhibit some degree of collinearity with regime type. If growth is jointly

determined with regime type, as the growth rate must help determine regime type not regime

longevity, then the statistical problem is simultaneity bias. That is, growth must specifically

affect democratic or authoritarian outcomes, not the general likelihood of regime survival.

While the econometric section explores this question anew, a brief review of published

results is instructive. Scholars thoroughly document the empirical relationship between the

level of economic development and democracy.23 Theory is less complete,24 but enough

evidence warrants evaluating the relationship between the level of development and regime

type because the vast majority of developed nations are democratic under most definitions.

Levels of development correlate with instances of democracy, a particular regime type.

But no published evidence suggests that the rate of economic development affects regime

type.25 Growth rates do not correlate with manifestations of democracy or dictatorships.26

Perhaps more important, Przeworski et al. (1995) as well as Przeworski and Limongi (1997)

provide no theoretical reason why democracies should be more sensitive than dictatorships

to poor economic performance in the short–run but not to mention the long run. Contrarily,

Bardhan suggests that authoritarian regimes are actually less stable under deteriorating performance because they lack popular legitimacy. He notes the possibility that authoritarian

regimes might survive during periods of sustained economic growth, but when an economy

persistently underperforms, democracies sometimes survive because they possess popular

legitimacy, whereas dictators do not (Bardhan, 1994, p. 237). Empirical referents might

include the “bureaucratic-authoritarian” model in Latin America or Marx’s explanation for

Bonapartism in nineteenth-century France, instances in which economic performance is the

regime’s raison d’être.

4.

Econometric Results

Given the three theoretical addenda, the final issue of possible simultaneity bias in these

data must be addressed before considering the direct effect of regimes on growth and

investment in the total sample, across income breaks to address development stages, and

exclusively within single-party and party-less dictatorships. Each model employs a GLS

random-effects procedure,27 and to ameliorate some validity issues associated with such

(unbalanced) “panel” models the regressions follow Grier and Tullock’s (1989) design with

five-year averaging for the medium-run specifications and dummy variables for continent

and time period to absorb specific spatial and temporal effects, respectively.28

4.1.

Regime Type Measures

Regressions on each democracy proxy, which include many of the factors that Barro (1996),

Przeworski et al. (1995), and Helliwell (1992) employ, statistically support the conclusion

regarding the exogenous nature of political regime type. More formally, the purported

�ECONOMIC GROWTH AND POLITICAL REGIMES

95

simultaneous equation system includes

Y1 = β0 + β2 Y2 + β3 Y3 + β4 X + µ

(3)

Y2 = α0 + α1 Y1 + α3 Y3 + α4 Z + ε,

(4)

and

where Y1 is economic growth, Y2 is some measure for political regime type, Y3 is the initial

level of development, X refers to the set of variables that identifies the first equation, and Z is

the set of variables that identifies the second equation. To determine whether a simultaneous

procedure is empirically necessary to estimate Y1 , α1 should be statistically significant. If

not and especially given no persuasive theory as discussed in the previous section, little

recommends substituting the instrumental variables derived in (4) for the actual regime type

measure in (3). If α3 is significant, the coefficient for the initial level of development, then

Y2 and Y3 , the measures of regime type and the initial level of development, respectively,

likely exhibit some degree of collinearity in growth regressions such as (3).

Regressors include the growth rate, the initial level of economic development, male and

female education levels, and factors that identify (4) with respect to (3)—the proportions

of contemporary democracies in the continent of a given country and the rest of the world,

a dummy for British colonial heritage and, in some specifications, lagged values of Y2 .29

The regressions30 include short-, medium-, and long-run averages, which respectively imply

two panels and a pure cross-sectional design. Turning to the results, the coefficient of the

growth rate α1 is not statistically significant in any regression for regime type Y2 , while the

coefficient for the log initial level of development α3 is significant within the 10 percent level

in every pooled but in no cross-sectional regression. This includes alternative regressions

on the Polity III data, the number of effective political parties, and logistic regressions on

the Polity III dummy variable in a pure cross-sectional mode.31 Perhaps more persuasively,

this analysis considers a subset that solely includes the poorest areas, which addresses

the contention in Przeworski et al. (1995) that more destitute democracies are particularly

fragile. But no regression for countries with per capita incomes of less than $2,000 or $1,000

yields a statistically significant coefficient for the growth rate α1 , while the coefficient for

the log initial level of development α3 is significant in all but one regression.32 Again, these

include short-, medium-, and long-run models; alternative considerations of Polity III and

effective party data.

In short, given comparatively consistent significant values for α3 , the results clearly indicate that the level and not the rate of development correlates with regime type. Specifically,

to confirm Lipset’s (1959) hypothesis and Barro’s (1996) more recent findings, both of

which do not control for growth, more developed nations are more likely to exhibit democratic characteristics. This further recommends inclusion of initial per capita incomes in the

neoclassical equations on growth and suggests the possibility of some collinearity, but a simultaneous equation procedure is neither theoretically essential nor empirically necessary,

which contradicts Brunetti (1997) and Przeworski and Limongi (1993, 1997).33 Political

regime type is therefore exogenous to growth.

�96

4.2.

DURHAM

Growth and Investment: Total Sample

Given no simultaneity bias, the growth and investment equations extend a neoclassical34

model to include regime type.35 As Levine and Renelt (1992) suggest, with approximately

fifty statistically significant growth regressors reported in the literature, specification bias is

prevalent (p. 943). Indeed, even among carefully specified studies that address this question

such as Kormendi and Meguire (1985), Grier and Tullock (1989), and Barro (1996), there

is no precisely common set of controls. This study follows Levine and Renelt’s four “base”

regressors that economists most commonly include in growth regressions, including the

log initial level of development, the level of investment in physical capital, the level of

investment in human capital (male and female education rates),36 and population growth.

However sensitive or empirically insignificant, two more controversial macroeconomic

variables control for relevant theoretical considerations particularly germane to executive

discretion, including the government ratio and openness to world trade.37 First, “supplyside” theories argue that increased taxes and government spending distort incentives and

reduce the efficiency of capital allocation. Regardless, any government more involved in the

economy, irrespective of regime type, would more likely have an effect on macroeconomic

performance generally and growth specifically, however virtuous. The model must distinguish regime type and the general effects of government intervention.38 Second, classical

liberal economic theorists such as Ricardo advance the virtues of comparative advantage.

More recently, Romer expounds this view with a different emphasis. In contrast to the

conventional focus on “objects,” Romer suggests that international trade creates greater

prosperity through the diffusion of productive ideas into the periphery (1993, p. 546). But

besides the economic rationale, this variable addresses the impact of international influences

on policy choice—exposure to the world economy39 constrains sovereigns and thereby limits their discretion (Gourevitch, 1978).40

Turning to the results, as the total sample regressions in Table 2 indicate, none of the

three alternative functional forms of the effective party/constitutional framework measure

are statistically significant—which generally differs from Kormendi and Meguire (1985),

Grier and Tullock (1989), and Barro (1996). The linear and linear-log forms indicate positive

yet insignificant relationships, and unlike Barro’s finding (1996, p. 14), the quadratic form

is also insignificant and suggests no optimal degree of discretion.

Besides inferences regarding the regime type proxy, the three equations substantiate

enduring neoclassical hypotheses. That is, the evidence generally supports the convergence

hypothesis, the benefits of investment and openness to international trade, and the negative

effects of population growth and government spending. Also, the proxy for male education

rates is positive, and female education rate is negative, consistent with previous findings.

But both human capital measures are insignificant.

As Levine and Renelt (1992) note, scholars commonly advance certain growth determinants that relate more intuitively to investment. Similarly, the argument that dictatorships

grow faster than democracies suggests that authoritarian regimes avoid electoral cycle consumption, which in turn facilitates increases in the physical capital stock. Conversely, the

democratic view argues that entrepreneurs have the incentive to invest under secure property rights. Like the growth equations in Table 2, regressions listed in Table 3 suggest

�97

ECONOMIC GROWTH AND POLITICAL REGIMES

Table 2. Growthb regressions: Total sample, GLS random effects models: Medium-run (five-year averages),

1960–1989.

Regression 1

β

Independent Variable

Effective party/constitutional

framework (EP/CF)

Log EP/CF

Square EP/CF

0.043

p value

Regression 2

β

p value

0.774

0.009

Regression 3

β

p value

0.078

0.803

−0.008

0.897

0.828

Log initial GDP

Investment ratio

Male education rate

Female education rate

Population growth

Openness to trade

Government ratio

Dummy for Africa

Dummy for Central

and North America

Dummy for South America

Dummy for Europe

Dummy for Oceania

Intercept

−1.077

0.110

0.173

−0.077

−0.443

0.008

−0.093

−0.814

0.000

0.000

0.383

0.708

0.010

0.042

0.000

0.130

−1.053

0.109

0.170

−0.074

−0.442

0.008

−0.092

−0.835

0.000

0.000

0.401

0.721

0.010

0.040

0.000

0.122

−1.070

0.110

0.172

−0.078

−0.442

0.008

−0.093

−0.821

0.000

0.000

0.386

0.707

0.010

0.043

0.000

0.127

−1.245

−1.797

−1.273

−2.001

10.278

0.047

0.004

0.041

0.061

0.000

−1.273

−1.810

−1.262

−1.991

10.173

0.045

0.004

0.040

0.060

0.000

−1.259

−1.806

−1.275

−2.008

10.210

0.046

0.004

0.040

0.059

0.000

Observations

Cases

Mean time periods per case

450

105

4.286

450

105

4.286

450

105

4.286

R2 within

R2 between

R2 overall

0.359

0.435

0.417

0.359

0.436

0.417

0.359

0.437

0.417

b. The source for all growth calculations is the inital GDP values from the Summers and Heston data set.

that neither the linear, linear-log, nor quadratic forms of the effective party/constitutional

framework measure are statistically significant in the total sample.41

4.3.

Developmental “Stages”

Another econometric objective is to explicitly test hypotheses regarding the levels of development. Indeed, this distinction perhaps directly addresses the dearth of significant findings

in the complete sample. That is, given that political regime type (discretion) does not apparently affect growth or investment universally, the organizational efficiency of dictatorship or

democracy possibly depends on certain circumstances. The malevolent effect of discretion

in rich countries perhaps neutralizes its benevolent impact in more destitute cases, which

produces the ambiguous universal effect reported in Section 4.2.

“Phases” or “stages” of industrialization are slippery concepts, but this inductive exercise

�98

DURHAM

Table 3. Investmentc regressions: Total sample, GLS random effects models: Medium-run (five-year

averages), 1960 to 1989.

Regression 4

Independent Variable

β

p value

Regression 5

β

p value

Regression 6

β

EP/CF

Log EP/CF

Square EP/CF

−0.326

Log initial GDP

Male education rate

Female education rate

Population growth

Openness to trade

Government ratio

Dummy for Africa

Dummy for Central

and North America

Dummy for South America

Dummy for Europe

Dummy for Oceania

Intercept

1.936

0.694

0.211

0.736

0.056

−0.096

−4.283

0.009

0.110

0.651

0.019

0.000

0.048

0.005

1.674

0.557

0.328

0.751

0.057

−0.101

−4.519

−3.836

−0.770

5.797

1.304

−5.917

0.032

0.677

0.001

0.679

0.293

−4.227

−1.045

5.355

0.595

−3.771

Observations

Cases

Mean time periods per case

451

105

4.295

451

105

4.295

451

105

4.295

R2 within

R2 between

R2 overall

0.164

0.725

0.622

0.166

0.725

0.622

0.170

0.732

0.630

0.294

0.117

p value

0.753

0.197

−0.242

0.029

0.021

0.204

0.482

0.017

0.000

0.035

0.003

1.844

0.644

0.232

0.747

0.059

−0.097

−4.494

0.012

0.137

0.617

0.017

0.000

0.043

0.003

0.018

0.571

0.002

0.848

0.501

−4.135

−0.972

5.877

1.396

−5.843

0.020

0.595

0.001

0.653

0.295

0.153

c. The source for all investment data is from the Summers and Heston data set.

is to divide the sample across eight percentiles of initial per capita GDP levels.42 That is,

“less developed” samples include countries below the twentieth ($1,114), thirtieth ($1,487),

fortieth ($2,093), and fiftieth ($2,904) percentiles. Conversely, the “developed’ samples

include countries above the eightieth ($7,638), seventieth ($5,463), sixtieth ($3,892), and

fiftieth ($2,904) percentiles. This division of the sample hardly captures subtleties such

as “industrial profiles” or sufficient “backward linkages,” but nonetheless countries above

(below) certain income breaks should be relatively more (less) developed, however complex

the concept. Again, the hypothesis is that discretion is effective in less developed areas but

deleterious in advanced economies with respect to both the allocation and accumulation of

resources.43

The data strongly contradict the view that discretion is more suitable in less developed

areas. According to Table 4 and Table 5, neither linear nor linear-log forms of the effective

party/constitutional framework measure is significant in growth regressions using any less

developed sample break. More problematic for Kurth and the tacit consensus, executive

discretion actually inhibits capital accumulation in poorer areas. For example, the linear-

�99

ECONOMIC GROWTH AND POLITICAL REGIMES

Table 4. Growth regressions: Less developed sample (20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% per capita GDP percentiles),

Linear effective party/constitutional framework hypothesis, GLS random effects models: Medium-run (five-year

averages), 1960 to 1989.

Per Capita GDP Level:

Regression 7

<$1,114

Regression 8

<$1,487

β

Regression 9

<$2,093

Independent Variable

β

p value

EP/CF

Log initial GDP

Investment ratio

Male education rate

Female education rate

Population growth

Openness to trade

Government ratio

Dummy for Africa

Dummy for Central

and North America

Dummy for

South America

Dummy for Europe

Dummy for Oceania

Intercept

−0.223

−0.589

0.190

−0.724

1.588

−0.254

−0.013

−0.040

−1.165

0.662

0.596

0.000

0.083

0.013

0.635

0.327

0.309

0.172

−0.473

0.496

0.172

−0.493

0.655

−0.066

−0.008

−0.085

−1.514

0.196

0.541

0.000

0.122

0.150

0.803

0.468

0.011

0.038

−0.302

0.164

0.144

0.022

0.025

0.007

0.005

−0.086

−1.198

0.390

0.814

0.000

0.945

0.954

0.980

0.549

0.012

0.146

−0.390

0.580

0.131

−0.041

0.047

0.099

0.006

−0.089

−1.588

0.129

0.181

0.000

0.857

0.866

0.650

0.386

0.000

0.004

−2.641

0.083

−2.772

0.009

−1.981

0.057

−2.639

0.000

−3.900

0.088

−2.537

−1.559

0.025

0.380

6.198

0.382

0.722

0.888

−2.659

−1.422

−2.074

0.881

0.012

0.365

0.437

0.856

−2.889

−1.296

−2.097

−1.660

0.000

0.182

0.307

0.584

p value

β

Regression 10

<$2,904

p value

β

Observations

Cases

Mean time periods

per case

88

31

134

46

179

59

224

70

2.839

2.913

3.034

3.200

R2 within

R2 between

R2 overall

0.304

0.881

0.591

0.268

0.586

0.500

0.308

0.445

0.431

0.308

0.638

0.471

p value

log form equations for the twentieth, thirtieth, and fiftieth percentiles (Regressions 19, 20,

and 22 in Table 7) suggest that increases in the number of effective parties increases the

investment ratio at a decreasing rate in less developed countries. Furthermore, while the

linear form is insignificant in the more affluent remaining breaks, the twentieth percentile

(under $1,114) equation, Regression 15 in Table 6, indicates a significantly positive linear

effect. In short, however robust these unexpected results, the data clearly reject the view

that dictatorship is more suitable for poorer economies.

With respect to advanced countries, the data render some support for the trajectory hypothesis. For example, the linear-log form is consistently significant in growth regressions

for the three highest percentiles (Regressions 27, 28, and 29 in Table 9), which suggests

a positive impact on expansion in more advanced economies. Less compelling, the linear

form is also positive and significant, albeit within the 10 percent confidence interval, in

samples above the seventieth and sixtieth income percentiles (Regressions 24 and 25). But

interestingly, discretion only seems to inhibit resource allocation but not accumulation in

advanced areas. The coefficients for the linear and linear-log forms are insignificant in

�100

DURHAM

Table 5. Growth regressions: Less developed sample (20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% per capita GDP percentiles),

Linear-log effective party/constitutional framework hypothesis, GLS random effects models: Medium-run (fiveyear averages), 1960 to 1989.

Per Capita GDP Level:

Regression 11

<$1,114

Regression 12

<$1,487

β

Regression 13

<$2,093

Independent Variable

β

p value

EP/CF

Log initial GDP

Investment ratio

Male education rate

Female education rate

Population growth

Openness to trade

Government ratio

Dummy for Africa

Dummy for Central

and North America

Dummy for

South America

Dummy for Europe

Dummy for Oceania

Intercept

0.021

−0.681

0.178

−0.830

1.763

−0.272

−0.012

−0.036

−1.184

0.784

0.537

0.001

0.048

0.006

0.612

0.340

0.361

0.170

−0.037

0.313

0.175

−0.529

0.664

−0.112

−0.009

−0.085

−1.344

0.560

0.693

0.000

0.104

0.158

0.671

0.424

0.013

0.076

−0.027

0.311

0.146

0.028

−0.005

0.122

0.007

−0.077

−1.415

0.662

0.649

0.000

0.930

0.990

0.636

0.409

0.022

0.085

−0.056

0.502

0.134

−0.018

0.011

0.086

0.006

−0.090

−1.435

0.266

0.246

0.000

0.938

0.968

0.695

0.379

0.000

0.011

−2.721

0.077

−2.589

0.018

−2.176

0.035

−2.509

0.000

−3.954

0.085

−2.578

−1.333

0.027

0.463

6.735

0.343

1.468

0.783

−2.849

−1.148

−3.395

−0.958

0.006

0.435

0.145

0.842

−2.829

−1.242

−3.171

−1.713

0.000

0.203

0.090

0.578

p value

β

Regression 14

<$2,904

p value

β

Observations

Cases

Mean time periods

per case

88

31

134

46

181

60

224

70

2.839

2.913

3.017

3.200

R2 within

R2 between

R2 overall

0.304

0.886

0.591

0.269

0.574

0.493

0.293

0.488

0.435

0.308

0.632

0.468

p value

every investment equation for developed samples, with the exception of the linear form in

the third highest percentile (above $3,892, Regression 33), which is unexpectedly negative.

4.4.

Growth and Investment in Dictatorships

Again, the preceeding discussion suggests that the effective party/constitutional framework

measure quantitatively distinguishes different authoritarian regimes. To extend Jowitt’s and

Huntington’s arguments about corruptive tendencies in political parties, the testable hypothesis, under the general authoritarian perspective, is that party-less dictatorships promote

growth and investment more effectively than single-party regimes. Conversely, according

to the broad democratic view, single-party regimes should be more effective than party-less

despots. Turning to the results, with respect to allocation, Regression 39 in Table 12 suggests

that single-party regimes had slightly higher growth rates, but the figure is insignificant.

But regarding capital accumulation, single-party regimes had investment ratios on average

�101

ECONOMIC GROWTH AND POLITICAL REGIMES

Table 6. Investment regressions: Less developed sample (20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% per capita GDP percentiles),

Linear effective party/constitutional framework hypothesis, GLS random effects models: Medium-run (five-year

averages), 1960 to 1989.

Per Capita GDP Level:

Regression 15

<$1,114

Regression 16

<$1,487

β

Regression 17

<$2,093

Independent Variable

β

p value

EP/CF

Log initial GDP

Male education rate

Female education rate

Population growth

Openness to trade

Government ratio

Dummy for Africa

Dummy for Central

and North America

Dummy for

South America

Dummy for Europe

Dummy for Oceania

Intercept

2.344

2.750

0.298

−0.716

−2.510

0.195

−0.050

−7.301

0.011

0.260

0.795

0.710

0.022

0.000

0.535

0.011

1.293

2.226

−0.430

0.269

−0.362

0.124

−0.080

−4.711

0.129

0.288

0.608

0.835

0.485

0.000

0.335

0.066

0.105

3.188

−0.156

1.836

−0.112

0.068

−0.072

−1.740

0.869

0.026

0.814

0.037

0.807

0.000

0.274

0.365

0.452

2.934

0.085

1.085

0.006

0.062

−0.115

−2.633

0.399

0.011

0.887

0.132

0.989

0.000

0.048

0.110

−8.516

0.075

−5.149

0.166

−4.265

0.080

−3.553

0.089

13.341

0.068

0.860

17.558

0.826

0.009

−7.725

0.620

−6.864

0.615

0.050

8.597

0.400

−15.078

0.984

0.012

0.946

0.134

0.302

7.890

−0.837

−12.194

0.889

0.002

0.877

0.129

p value

β

Regression 18

<$2,904

p value

β

Observations

Cases

Mean time periods

per case

88

31

134

46

179

59

224

70

2.839

2.913

3.034

3.200

R2 within

R2 between

R2 overall

0.617

0.469

0.414

0.321

0.396

0.349

0.257

0.548

0.414

0.221

0.645

0.479

p value

and ceteris paribus about three percentage points greater than their party-less counterparts

during the period, which is significant at the 5 percent level according to Regression 40.

This contradicts Jowitt’s and Huntington’s views based on more qualitative evidence, and

the results suggest, in support of the general democratic view, that greater discretion within

dictatorships enhances investment.44 A plausible interpretation is that institutionalized parties on average restrain capricious autocrats and thereby create a more suitable investment

environment.

5.

Conclusions

In summary, a crucial shortcoming in the debate on regimes and growth concerns the dearth

of continuous measures that focus on institutions rather than outcomes. While not necessarily a superior proxy for all econometric applications, the institutional focus of the

effective party/constitutional framework measure more directly addresses the serviceable

implications of this particular debate. Also, two additional problems beset previous studies.

First, the literature ignores the possibility that the effectiveness of particular regime types

�102

DURHAM

Table 7. Investment regressions: Less developed sample (20%, 30%, 40%, and 50% per capita GDP percentiles),

Linear-log effective party/constitutional framework hypothesis, GLS random effects models: Medium-run (fiveyear averages), 1960 to 1989.

Per Capita GDP Level:

Regression 19

<$1,114

Regression 20

<$1,487

β

Regression 21

<$2,093

Independent Variable

β

p value

EP/CF

Log initial GDP

Male education rate

Female education rate

Population growth

Openness to trade

Government ratio

Dummy for Africa

Dummy for Central

and North America

Dummy for

South America

Dummy for Europe

Dummy for Oceania

Intercept

0.287

2.884

0.448

−0.817

−2.237

0.195

−0.048

−7.780

0.022

0.245

0.697

0.671

0.045

0.000

0.562

0.006

0.263

2.001

−0.408

0.222

0.295

0.131

−0.074

−5.487

0.037

0.333

0.623

0.862

0.563

0.000

0.368

0.031

0.150

2.981

−0.268

1.857

−0.115

0.069

−0.068

−2.156

0.187

0.036

0.685

0.033

0.801

0.000

0.297

0.264

0.198

2.860

−0.030

1.124

0.028

0.064

−0.109

−3.054

0.065

0.012

0.960

0.116

0.948

0.000

0.058

0.064

−8.870

0.059

−5.648

0.123

−4.570

0.058

−3.928

0.059

12.687

0.078

0.858

16.875

0.824

0.011

−6.886

0.668

−3.896

0.776