Her Fight is Your Fight: “Guest Worker” Labor

Activism in the Early 1970s West Germany

Jennifer Miller

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville

Abstract

When the postwar economic boom came to a crashing halt in early 1970s West Germany,

foreign “guest workers,” often the first to be laid off, bore the brunt of high inflation, rising

prices, declining growth rates, widespread unemployment, and social discontent.

Following the economic downturn and the ensuing crisis of stagflation, workers’

uprisings became increasingly common in West Germany. The summer of 1973 saw a

sharp increase in workers’ activism broadly, including a wave of “women’s strikes.”

However, historical attention to the role of foreign workers, especially of foreign

female workers, within these strikes has been limited. This article presents a case study

of wildcat strikes spearheaded by foreign, female workers in the early 1970s, focusing

specifically on the strikes at the Pierburg Autoparts Factory in Neuss, West Germany.

For these foreign women, activism in the early 1970s had a larger significance than just

securing better working conditions. Indeed, striking foreign workers were no longer

negotiating temporary problems; they were signaling that they were there to stay.

Foreign workers’ sustained and successful activism challenged the imposed category of

“guest worker,” switching the emphasis from guest to worker. Ultimately, the Pierburg

strikes’ outcomes benefited all workers––foreign and German, male and female––and

had grave implications for wage discrimination across West Germany as well.

“The public is astonished by the determination of the foreign women,” proclaimed a West German television reporter on December 13, 1973.1 “And

rightly so,” she continued, “the foreign workers––women no less––threatened

to disrupt the entire West German automobile industry.”2 The 1971 – 1973

wildcat strikes at the Pierburg Auto Parts Factory (near Dusseldorf) did

indeed send shockwaves through the West German auto industry. The

summer of 1973 saw a sharp increase in workers’ activism broadly, including a

wave of “women’s strikes.” On July 16, four thousand, mostly foreign, female

workers went on strike at the Hellawerk Factory in Lippstadt; thirty female

workers went on strike at the Opal factory in Herner; and seamstresses protested speedups in Cologne.3 These strikes were part of a labor insurrection

of men and women, foreign and German, that swept the country in the early

1970s as the postwar economic boom came to a crashing halt. Foreign “guest

workers,” often the first to be laid off, bore the brunt of high inflation, rising

prices, declining growth rates, widespread unemployment, and social discontent.

For foreign workers, activism in the early 1970s had a larger significance than

just securing better working conditions. Striking foreign workers were no

longer seeking solutions to short-term problems; they were signaling that they

International Labor and Working-Class History

No. 84, Fall 2013, pp. 1– 22

# International Labor and Working-Class History, Inc., 2013

doi:10.1017/S014754791300029X

�2

ILWCH, 84, Fall 2013

were there to stay. Through their activism, “guest workers” created a different

future for themselves in Germany by demonstrating political consciousness.

Their actions also highlighted the unsustainability of the “guest worker”

program itself––and their participation in it––as they shifted from temporary

participants to more permanent actors within German industry and society.

After a brief introduction of the “guest worker” program, this article examines a few representative strikes that illuminate the implications of foreign

workers’––especially women’s––activism in the early 1970s. A closer look at a

key strike at the Pierburg Auto Parts Factory in Neuss, West Germany,

reveals more than just an argument against the sexist “light wage category

II,” which allowed the company to dodge equal pay for equal work. In choosing

to strike, these foreign women also asserted a new identity––one forged through

their intersecting experiences as women, as foreigners, as “guest workers,” and

as factory workers.4 Ultimately, their labor activism benefited all workers at the

factory and challenged the imposed category of “guest worker,” switching the

emphasis from guest to worker. As such, these foreign workers stand at a

crucial intersection of immigration history, labor history, and German citizenship debates.

The “Guest Worker” System

Across Western Europe economies grew at historic rates in the postwar era.

German GDP per head more than tripled in real terms between 1950

and 1973.5 The postwar rapid growth coupled with lingering labor shortages

spurred West Germany (and Western Europe in general) to turn to

foreign labor. Starting in 1955, West Germany used bilateral “guest worker”

treaties to begin recruiting foreign workers from southern European and

Mediterranean countries. Over the course of a decade, West Germany imported

increasing numbers of workers from a variety of countries, with workers from

Turkey forming the majority by the end of recruitment in 1973.6

The “guest worker” arrangement was designed to recruit single, preferably

male workers for a two-year stay in West Germany. However, this description

rarely matched the applicant pool or employers’ demands, given the need for

female workers to fill jobs deemed “women’s work.” Historian Monika

Mattes notes that the dubious yet popular cliché of the male “guest worker”

who later sends for his wife and children has yet to be seriously critiqued by

scholars.7 The increased demand for female labor occurred at the exact time

that West German women were encouraged to leave the work force to

restore nuclear families in German society. As a result, West German factories

relied heavily on foreign women to fill so-called “women’s positions.”8 By 1973,

at the peak of the “guest worker” program, there were about 2.3 million foreign

workers in West Germany and more than 52,000 of them were women.9 By the

time of the Pierburg strike, there had been a long history of importing foreign

female workers, starting slowly at first, dipping during the 1967 recession, and

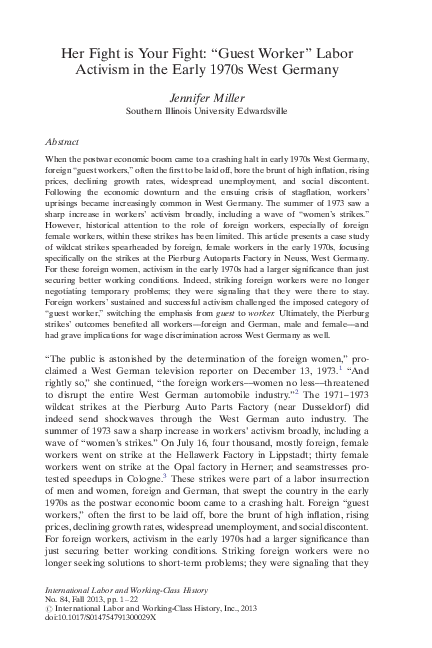

rebounding with a large surge beginning in 1968 (see Table 1). In the early

�Her Fight is Your Fight

TABLE ONE

Year

Italy

Spain

Greece

Turkey

Portugal

Yugoslavia

Total

Year

Italy

Spain

Greece

Turkey

Portugal

Yugoslavia

Total

3

Foreign Female “Guest Workers” in West Germany, 1961–1973

1961

1962

1963

1964

1965

1966

1967

2,942

6,280

5,879

46

–

–

15,147

1,608

8,615

11,852

504

–

–

22,579

545

9,013

13,681

2,476

–

–

25,715

517

8,078

11,155

5,022

5

–

24,777

729

8,050

14,310

11,107

232

–

34,428

520

7,508

14,035

9,611

1,188

–

33,505

157

1,436

1,471

3,488

334

–

6,886

1968

1969

1970

1971

1972

1973

212

4,646

10,740

11,302

1,118

–

28,088

224

6,816

21,328

20,711

2,313

14,754

66,146

111

6,924

19,931

20,624

3,298

19,908

70,810

55

5,689

12,092

13,700

3,627

17,252

52,484

32

4,632

5,629

16,498

3,489

12,432

42,992

14

4,226

1,776

23,839

5,550

16,461

52,070

Source: Monika Mattes. ‘Gastarbeiterinnen’ in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Anwerbepolitik, Migration

und Geschlecht in den 50er bis 70er Jahren. Frankfurt am Main: Campus, 2005. 39.

1970s, female workers from Turkey, Greece, and Yugoslavia formed the

majority of foreign female “guest workers” in West Germany. (See Table 1)

Origins of Foreign Labor Activism in Germany

Since the early nineteenth century, foreign workers in Germany have used labor

activism, legal and illegal, to negotiate definitions of belonging; of local,

national, and class identity; and of solidarity. Historian John Kulczycki has

argued that ethnic Polish miners in nineteenth-century Germany, though

aware of cultural and linguistic differences, worked together with their native

German coworkers toward common working-class goals, with the main

barrier to class solidarity being the German workers’ prejudice against

them.10 What connects the nineteenth century movements with more contemporary protests is not only the role of migrants, but also the civic participation

inherent in labor activism. For nineteenth-century foreign miners, according

to David F. Crew, “occupation . . . provided the miner with an ‘integrated’ role

in German society . . . [that] combined economic, social, and legal functions,”

and it is this “occupational community” more than material deprivation that

explains why workers strike.11 In the case of postwar “guest workers,” occupational community cannot be assumed as a goal as many workers maintained

a desire eventually to return “home.” However, through labor activism both

supposedly temporary workers and their reluctant hosts often achieved “occupational community,” whether they intended to or not.

�4

ILWCH, 84, Fall 2013

By the 1970s, foreign workers were well integrated into the West German

economy, and the reporter’s comments about the 1973 Pierburg Strike shutting

down an entire industry were not hyperbolic: By the early 1970s, the West

German construction, steel, mining, and automobile industries had become

largely dependent upon foreign labor.12 In 1973, 35.7 percent of all “guest

workers” were employed in the iron and metals industry, 24.1 percent in processing trades, and16.6 percent in construction.13 In 1973, 11.9 percent of all workers

in West Germany were foreign. In other words, every ninth worker in West

Germany was foreign; in the manufacturing sector, it was every sixth worker.14

Yet despite the vital role they played, labor unions and smaller elected

workers’ councils often isolated foreign workers, while employers exploited

them.15 German labor unions were initially critical of “guest worker” programs,

fearing they would depress wages and degrade working conditions.16 However,

unions strategically ended their resistance to the program in order to be involved

in the planning process, for example, to secure the same wages across the board

and to recruit foreign workers into their organizations.17 By the end of the 1960s

about 20 percent of foreign workers had joined unions––a significant number

considering that only 30 percent of West German workers were organized.18

“Guest workers” participated in and initiated both legal and illegal labor

activism from the beginning of the program.19 On April 30, 1962, in the city

of Essen, 300 Turkish workers went on strike over underpaid Kindergeld, or

child benefit payments, and the police responded with rubber bullets and by

deporting ten of the strikers.20 Turkish workers were indeed eligible for

German child benefit payments, but not for children left behind in Turkey––

an arrangement that did not suit the transnational families that the “guest

worker” arrangement prompted. The West German Federal Labor Ministry

complained that officials in Istanbul had been falsely promising workers

benefit payments for children left behind in Turkey. Those on strike in Essen

appealed to West German labor unions for help. They replied, “You’re right,

but there is nothing that we can do for you.” The foreign workers also appealed

unsuccessfully to the Turkish Consulate in West Germany.21 Neither the West

German unions nor the Turkish consulate would represent these workers,

placing them in a no-man’s-land that mirrored their lived reality: not truly

welcome in West Germany and yet no longer under Turkish protection.

Foreign workers’ problems stemmed from the fact that “equal rights” were

not “equal” for foreign workers. Both employers and the West German government deducted money for taxes, pensions, social benefits, and rent from

workers’ pay checks, regardless of whether or not foreign workers planned to

take part in the social services such payments supported. A patronizing orientation pamphlet, titled Hallo Mustafa! explained that such deductions were

simply a part of life and not meant to be understood by foreigners.22 “You

don’t understand,” the pamphlet chided, “and can’t tell the difference

between gross and net pay, and most of all you don’t understand the deductions

for social benefits and taxes. . . . At first, you get the feeling that they are trying to

take you for a ride with these complicated numbers and figures. . . . [Dear]

�Her Fight is Your Fight

5

Mustafa, in my opinion, you all are much too suspicious.”23 However, Turks’ suspicions were reasonable: The West German Liaison Office in Istanbul could not

offer workers a clear idea of what their wages or benefits would be in West

Germany, and the information they did distribute was often misleading, erroneous, or misunderstood.

Many “guest workers” were disappointed with their jobs for a variety of

reasons ranging from low wages, strenuous working conditions, the risk of workplace injury, and general underemployment.24 Most significantly, whatever the

length of their stay, “guest workers” had few chances of promotion or overtime.25

“In the beginning our wages were very low. [But] everyone who wanted to go

didn’t care about the wages very much,” reported a man from Bursa, Turkey,

who went to West Germany in 1963. “[T]he [West German] government didn’t

give this much importance. . . . I earned 3DM per hour. A German worker

doing something much simpler was earning about 6–7DM per hour.”26

Foreign workers often had larger problems with their employers than their

poor wages. Company housing was often a key point of exploitation of workers

who had few alternatives but to live in company-supplied housing, with rent

deducted from their paychecks. In a documentary film about the Pierburg

strikes, one woman declared that the firm’s housing represented “modern-day

feudalism.”27 She paid 60DM a month to live four-to-a-room with no running

water. Furthermore, the building manager restricted all visitors, especially

union representatives.28 This “guest worker” emphasized that during the 1973

Pierburg strike, “foreign women haven’t forgotten how they have been

treated by the company.” She responded by drawing up fliers that proclaimed,

“Does feudalism still exist?” The fliers cited the West German Constitution’s

Article 13, which stated that one is guaranteed freedom within one’s home,

including the ability to receive guests. Another female employee at Pierburg

apparently paid 200DM in rent for a damp cellar room that had previously

been used to keep pigs.29 Such horrific housing problems, which were specific

to foreign workers, engendered unusual and fraught relationships between

employer and employee, fueling mistrust.

Foreign workers also suffered from poor working conditions. Akkordarbeit,

the piecework system that many West German employers used with foreign

workers, was particularly exasperating. According to Akkordarbeit, wages

could vary based on the number of days worked and the completion of

certain tasks.30 A spinning factory’s orientation booklet explained in Turkish,

“As you know, nobody can work at the same speed and produce the same

amount. . . . The Akkord system is simple. Whoever produces more gets paid

more.”31 Despite the system’s “simplicity,” one former worker explained the

potential for confusion and errors in an Akkord paycheck: “Because we

worked on different machines . . . and different work was worth different

amounts . . . sometimes there were mistakes; sometimes it says you were on a

different machine than you were. Then you go to the boss, and he checks it

with his notes . . . And then you go to the payment office, and they make corrections as well.”32 Piecework also depended upon collaboration with German

�6

ILWCH, 84, Fall 2013

coworkers, too, leading to aggravation and misunderstandings due not only to

language problems but also to differing work speeds. There were even reports

that West German workers complained Turkish workers were “spoiling the

Akkord” by working too quickly.33

Foreign workers, especially women, were ripe for labor organizing as the

West German economy began to decline in the late 1960s, and the “guest

worker” system began to crack under the weight of long-standing problems.

The particular hardships foreign workers faced, on and off the shop floor,

coupled with their perceived temporary status often hindered solidarity with

German colleagues. Yet despite their vastly different experiences, within

many strikes there were imperfect moments of solidarity, when German and

foreign workers came together, motivated by either common concerns or the

potential for personal gain.

Economic Downturns and Worker Responses

A short-lived recession from 1966 –1967 was the first point of stagnation in the

postwar period to combine high unemployment and lower real wages.

Correspondingly, this period witnessed the first significant wave of postwar

labor activism, foreign and domestic, to spread across West Germany.34 When

the West German economy began to falter in 1966, employers reacted immediately by laying off around 1.3 million foreign workers.35 Employers also

responded by increasing mechanization and production speeds, worsening

working conditions. Workers responded in kind. During September 1969,

140,000 workers from 69 different companies within the steel, metal, textile,

and mining industries made news throughout West Germany with their labor

strikes.36 Shortly thereafter, the 1973 OPEC oil embargo prompted further

economic downturn and stagflation, while workers’ wages could not keep up

with cost-of-living increases.37 The West German “economic miracle’” had

relied on increasing productivity by hiring more workers to use increasingly

mechanized, faster machinery. At the same time, employers maintained low

wages––wages that remained low especially in relation to profit margins,

inflation, and the new speeds of production. The progressively insecure economic situation made workers’ uprisings common.38

Foreign and West German workers had varying degrees of solidarity in

labor organizing in the late 1960s and early 1970s. In some cases, West

German and foreign workers did not support one another, and yet both ultimately benefited, as was the case at the Hella Automobile Producer in

Lippstadt, West Germany. On July 16, 1973, 800 German skilled workers

received a raise of fifteen cents per hour, while unskilled, mostly foreign,

workers received no increase.39 In response, the foreign workers went on

strike, demanding fifty cents more per hour, scaring the workers’ council.

“They will kill us if we force them to work!” claimed the president of the

workers’ council at Hella, referring fearfully to the 3,000 foreign workers

from Spain, Greece, Italy, and Turkey who went on strike from July 17 –19,

�Her Fight is Your Fight

7

1973.40 Their West German coworkers did not join the strike, offering instead

mocking words of support, such as the awkwardly phrased, “You do good

job!”41 The foreign workers were, however, successful and, in the end, all

workers gained raises of between thirty and forty cents per hour. The foreign

workers had risked more than their German coworkers: They could have lost

their jobs and their housing, as well as the work and residency permits they

needed to stay in country.

There were also cases of temporary German-foreign solidarity, such as the

strike at the Duisburg-Huckingen steel mill May 18 –28, 1973. In this case, 380 of

700 workers went on strike over increasingly poor working conditions, including

speedups and dangerous tasks, such as having to handle burning hot materials.42

At first, organizers had not included Turkish workers in their plans for work

stoppage. By the end of the strike, however, Turkish workers joined their striking West German colleagues, prompting management’s attempts to fire them.

This risky act of solidarity produced results: All workers received twenty-five

to seventy cents more per hour.43

In these two contrasting examples, a precarious occupational community

was achieved: in the first case, through the result––raises for all; in the second,

through joint involvement. In the end, whether they were foreign or native

born, they were all, de facto “German workers,” even if they would not have

acknowledged this at the time. In the majority of cases, foreign workers lent

their support to West German workers; the reverse was less likely to occur.44

One of the most famous strikes among foreign workers was prompted over

vacation leave: the so-called “Turkish Strike” at the Cologne Ford August

24– 30, 1973.45 Because of the great distances foreign workers wished to

travel during their vacations, in order to visit their homes and families in

remote places like Turkey, they had different needs than their West German

counterparts when it came to vacation allotments. This became a common

source of conflict.46 In 1973, Ford management fired Turkish workers who

had returned late from vacation, and 300 Turkish workers protested with a

strike and sit-in, against the wishes of their union.47 Seeing an opportunity,

German workers joined the strike to request higher wages for themselves.

When the Metalworkers Union and the company’s workers’ council joined in,

management agreed to a small wage increase to offset inflation. The German

workers and union members were satisfied, but the company continued to

ignore the Turkish workers, prompting outrage and an escalation of the strike.

Turkish workers were 53.1 percent of the workforce, but only 12.7 percent of

the workers’ council.48 A large fight, attracting police intervention, ensued,

and the management fired many of the Turkish workers in retribution,

leading to their deportation.49 For the Turkish workers who remained, the

outcomes were a repeal of some of the layoffs but also increased “resentment

of the foreigners’ rabble-rousing.”50

Labor activism in the 1960s and early 1970s began to forge new and even surprising alliances between West German and foreign coworkers, even as the two

groups continued to view each other as distinct. Over time moments of solidarity

�8

ILWCH, 84, Fall 2013

also worked to dissipate tensions between the two groups, as they demonstrated

that the presence of “guest workers” in West Germany was perhaps more permanent than even the workers themselves had intended or were willing to acknowledge. That West Germans and foreign-born “guests” came together through labor

activism is not surprising considering that the workplace provided the main

sources of interaction. The Pierburg Strikes, the subject of the next section,

present case studies that highlight both the tensions among different groups

and, at the same time, the success they were able to achieve through solidarity.

Foreign female workers initiated wildcat strikes at Pierburg over discriminatory

wages but continued the strike to protest poor living conditions (especially

housing) and inadequate union representation. But, by the end of the strike, all

workers––male and female, foreign and German, skilled and unskilled––joined

together in an increasingly effective coalition.

Postwar “Wage Categories” and the Pierburg Strikes

While scholars tend to pay more attention to the “Turkish strike” at Ford, the

Pierburg strikes in Neuss, Germany, were arguably more significant, as they

were spearheaded by foreign women, achieved full participation by all employees, and successfully challenged a federally-mandated wage system. Foreign

women do not make up a very large part of the literature on labor activism in

postwar Europe, but they, often acting in solidarity with women of different

national origins, were the primary instigators of many battles over pay inequities

for both foreign and German women. Women workers of various nationalities

participated in the Pierburg Strike, and in this case gender provided the main

source of solidarity. After an introduction to the history of the West German

“wage categories,” this section turns to the Pierburg strikes that impacted

both foreign and German women’s wages.

West German “wage categories” differentiated and set the wages for

“skilled” (often German men) and “unskilled” (often foreign and female)

workers. The 1949 West German constitution guaranteed equal rights through

a series of antidiscrimination guidelines in its Article 3. In response, a 1955

Federal Labor Court declared the existing “women’s wage” categories unconstitutional. This ruling should have meant that women’s salaries would increase by

an average of twenty-five percent, or more. Employers, who understandably

wanted to keep wages down, invented a new category, the “light wage category,”

meant to designate unskilled and “light work,” to replace the now-illegal

“women’s wage category.” From 1955 on, companies argued that women’s

lower wages were not due to their sex, but because women had “less strength”

and “lighter” work to do. When accused of renewed discrimination, employers

countered that men were also employed in the light-wage categories.

“Employers always get creative whenever it comes to the constitutional right of

equal pay for equal work,” reported the West German weekly, Stern, in 1973.51

Union leaders, most of them male, were generally unsupportive of female

workers’ causes and did not protest the creation of the light-wage categories.

�Her Fight is Your Fight

9

According to historian Ute Frevert, both employers and trade unions could

agree on the new wage categories: For unions, higher wages for women might

well have delayed the attainment of “more important trade union goals such

as the implementation of the forty-hour week or the extension of paid

holidays.”52 In collective bargaining agreements, officials designated unskilled

and semi-skilled jobs according to the physical strength required, while in

skilled and professional jobs the degree of “responsibility” was the criterion

used for classification. “Easy” and “simple” jobs were classified under Wage

Categories I or II or, at best, under Wage Category III, while jobs that called

for hard physical labor were generally classified under Wage Categories IV or

V, which commanded considerably higher wages. In a kitchen furniture

factory, where both men and women worked on assembly lines drilling holes

into doors, the women were in Wage Categories I and II, but the men were in

Wage Categories III and IV, based on the rationale that the men were drilling

holes in “bigger and heavier doors.”53 In short, the new wage categories

quickly came to differentiate men’s from women’s work. A 1970s governmentsponsored study on the proper criteria for job evaluation recommended that

only physical exertion be used for assessment, but it could do no more than

provide suggested guidelines to the private sector.54

Foreign female workers in West Germany had long been performing heavy

manual labor as “guest workers,” a category largely gendered male; at the same

time, employers paid foreign women according to the light wage categories, gendered female, regardless of their jobs’ degree of physicality. For “guest workers,”

the German Employment Offices in Turkey defied the spirit of the 1955 ruling

and openly listed wages as “Wage Category I (women)” and “Wage Category

III (men).”55 Protective legislation designed for female workers meant that

foreign female workers were paid less, but not that they were excluded or actually “protected” from physically demanding jobs.56 It was this hypocrisy, more

than anything else, that prompted the strikes at Pierburg in Neuss.

With the importation of “guest workers,” foreign women became the new

“women workers” of West Germany. “Expanded employment of German

females was economically a reasonable and feasible step, but it was undesirable

from the standpoint of ‘family policy,’” reported the industrial newspaper,

Industriekurier, in a 1955 article explaining why “guest workers” were necessary.57 Though this policy of encouraging West German women to stay home

to rebuild nuclear families was primarily a product of the immediate postwar

years, especially in contrast to its East German counterpart, the real need for

female workers remained unchanged, and West German companies increasingly

sought foreign women to fill vacancies in “women’s work.”58

Like many West German industrial companies, Pierburg Auto Parts, which

supplied carburetors to most of the West German automobile industry, both

relied heavily upon and profited from foreign female labor. Foreign workers,

especially women, were drawn to these employment opportunities, as the

Pierburg factory in Neuss was one of the few in its area to hire women.59

Pierburg also recruited the wives of men working in the surrounding area’s

�10

ILWCH, 84, Fall 2013

metal industry, in addition to foreign employees’ wives, correctly guessing that

working couples would put up with most any situation to be able to live in

West Germany together.60 By 1973, Pierburg employed 3,600 workers, among

them 2,100 foreign workers and a total of 1,700 women (1,400 of them

foreign) in the “Light Wage Categories.”61 About 70 percent of the foreign

workers at Pierburg were women, comprising the majority of all women

workers, all of whom were in the lower wage categories.62 According to

German sociologist Godula Kosack, who researched the strike in 1976,

Pierburg employed 900 Greeks, 850 Turks, 380 Yugoslavs, 300 Spaniards, 200

Portuguese, 150 Italians, and 850 Germans.63 Women in the “Light Wage

Category I” earned 30 to 40 percent less than their male colleagues.

Pierburg’s heavy reliance on foreign female workers made it ripe for a challenge

to the discriminatory wage categories.

The first strike by foreign women at Pierburg took place in 1970, initiated

by 300 Yugoslavian women who were the first to be hired by contract in 1969.

Pierburg housed them in three barracks on site, prompting, in the words of a

workers’ council member, an “uncanny sexual state of emergency” and the subsequent banning of male visitors.64 These women apparently went on strike to

protest the restrictions on their personal lives as well as wage discrimination.65

On May 15, 1970, foreign and German female Pierburg workers protested

against “Light Wage Category I.” Citing poor working conditions, unequal

work distribution, and gender discrimination in raises, 800 foreign and

German women signed a resolution requesting higher wages for all female

employees.66 Management did not respond until the next day when around

1,000 women were standing in protest on the factory grounds. Neither the

union nor the all-male, all-German worker’s council at Pierburg supported

this initial strike. According to a 1970 newspaper report, Pierburg’s management was not above threatening the striking women, especially the foreign

ones.67 Various department heads attempted to scare off the women with the

threat of firing and deporting them: “If you don’t want to work, then you’ll go

with the police to the airport!”68 The risk of deportation was real, as their

West German residence permits were contingent upon proof of employment

and housing. Despite compromise attempts, intimidation efforts, and police

intervention, the women (who numbered 1,400 in the end) persisted until

they achieved the following: twenty cents more per hour for Wage Categories

II – V, a bonus of 20DM, and the establishment of a representative body to

evaluate the Wage Categories of jobs.69 After only a few days, management

ended the strike by agreeing to eliminate Wage Categories I and II, but, in practice, Wage Category II remained.70

Two years later, on June 7, 1973, becoming impatient about the promised

wage reforms, three hundred female workers at Pierburg conducted a

“warning strike” and made the following demands:

(1) The Wage Category II (WC2) must be eliminated. All women of WC2 must be

re-categorized to Wage Category III (WC3). (2) Those with seniority should earn

�Her Fight is Your Fight

11

more than newly-hired workers. (3) Because there are no clean work places in the

firm, every employee is to receive a supplement for the dirty conditions. (4)

Everyone (male and female) is to receive an additional 1DM per hour. (5) The

women who are working on the special machines are to be regrouped in Wage

Category IV. (6) Workers must be paid for the wages lost during these proceedings

[the strike]. (7) All of the women who perform heavy manual labor must finally be

paid as much as men. (8) There cannot be any firings due to taking too many sick

days. (9) Overtime may not be unfairly distributed. (10) Whenever one is sick and

wants to go to a doctor, he or she should receive half a day paid leave. (11) One

day a month should be paid for housekeeping [“housewife’s day”]. . . . (12)

Travel money must be increased. (13) Tomorrow everyone should be able to

leave the factory two hours earlier to pick up his [sic] money.71

The elimination of Wage Category II and a 1DM-per-hour raise for all workers

were the main demands. In an attempt at solidarity, those on strike distributed

fliers in workers’ various languages––Spanish, Serbo-Croatian, Italian, Greek,

and Turkish––proclaiming: “Two months ago, 200 of our workers mustered up

the courage and went on strike for two days for higher wages.”72 It continued,

“[the company said it] would not be coerced by terrorists, [and] that the majority

of the employees were satisfied with their wages, since they were not striking

along with them . . . Colleagues, why didn’t you support us and strike with us?

The demands are still valid: 1DM more an hour for everyone! “Wage

Category 2” must be eliminated!”73 The organizers emphasized transethnic

worker solidarity against management. After the union stepped in to negotiate,

the strike ended on the second day. Management, however, maintained its goal

of retaining the “Cheap Wage Categories” at all costs, leaving most dissatisfied.

Pierburg did not take the strike seriously and planned to fire and replace

the 300 workers with new, and therefore more insecure, foreign workers in

the fall. The June “warning strike” ended with the promise of negotiations

between management and the workers’ council, but new arrangements were

not secured nor did the union follow up.74 The foreign women who initially protested their placement in Wage Category II found little support among their coworkers, in their workers’ council, or in their union. Company founder,

Professor Alfred Pierburg, called and spoke to the chair of the workers’

council, Peter Leipziger, on June 14, 1973 and promised that there would be

no firings, only paid suspensions of those the council fingered.75 The Workers’

Council incriminated the striking women by reporting them to management

(instead of representing their interests), and Pierburg deported six of the

foreign women as a result.76

After such an unsatisfying result, it is little surprise that foreign women at

Pierburg went on strike again two months later, in August 1973, calling once

again for the elimination of Wage Category II. The union would not support

the strike and responded aggressively with an article in the union newsletter

titled, “Guest Workers Are Not Discriminated Against: The Pierburg Strike is

Illegal.”77 In a press release that was translated into Turkish, Greek, and

�12

ILWCH, 84, Fall 2013

Italian, the Industrial Union of Metalworkers reported on August 15 that,

“based on legal conditions in the Federal Republic, the Metalworkers Union

cannot deem the work stoppage at the A. Pierburg Company legal.”78

However, the press release continued, in order to dissipate the tensions, negotiations continued: “For some time the workers’ council and the

Metalworkers union have been negotiating with management for an equitable

practice in the wage contracts. The hard work of the approximately 1,700

employees, especially the foreign women, is being unjustly characterized as

‘physically light’ (Wage Category II).”79 The foreign female workers,

however, lost patience with the negotiations and with the workers’ council

and carried out the strike on their own terms to great success.

The August 1973 Strike over Light Wage Category II

On Monday, August 13, 1973, as the 6 A.M. shift began to arrive at around 5:30

A.M. , twenty foreign female workers distributed fliers, announcing that in an

hour workers would go on strike for the elimination of Wage Category II and

1DM more per hour.80 By 5:50 A.M. , between 200 and 250 (mostly foreign)

male and female workers stood before the factory gates, declaring their

support for the strike. At first, the German foreman just observed. Then, at

6:30 A.M . sharp, he demanded that they get to work. Shortly thereafter, the

police arrived with patrol wagons and demanded that the factory gates be

cleared of the striking workers. According to documentation published by

strike leaders in 1974, the following mêlée occurred:

One of the foremen fingers Elefteria Marmela––a Greek woman who, along with

her husband, is a union member––as the organizer of the strike. As the police

attempt to arrest Marmela, she resists and a scuffle ensues. Another Greek

worker has a camera with him and snaps photos . . . The police respond by confiscating his camera. Another Greek man manages, however, to rip the camera out of

his hand and throw it to another Greek worker. A new scuffle begins. Suddenly an

officer grabs his pistol and screams, ‘Get back!’ A Greek woman steps up and yells,

‘So shoot me then! Or are you afraid?’81

The police tried to arrest Marmela, who resisted and was injured; she returned

with a bandaged arm. In the end, no one was arrested, but as the police

wagons were pulling away, one officer apparently called back, “Dirty foreigners!

I’ll kill you!”82 Three hours later, three VW buses filled with police officers

arrived. This time, the officers surrounded the protesters and arrested three

Greeks, two women and one man, who were held for ten hours and interrogated.

The police presence scared off many of those on strike, so that at the beginning of

the breakfast break, there were only 150 left on the picket line. The strikers cried

“Everyone out!” in an attempt to secure solidarity with other workers. Their

chants worked. By the end of the break, 600 additional workers (male and

female) had joined the strike, completely stopping all production at Pierburg.83

�Her Fight is Your Fight

13

The following day, the entire early shift stood in front of the factory gates,

about 350 people. At 6:30 A.M. , three buses filled with police arrived, and officers

jumped out and immediately began battering the protesters. Many foreign

women were injured and subsequently hospitalized.84 The police again attacked

Marmela, injuring her severely. The media arrived, including television and

radio reporters, and began filming beatings and scuffles that were aired later.

The German weekly, Stern, published a photograph of two policemen dragging

a foreign woman away by the arm.85 Once the cameras began recording, the

police pulled back and there were no more arrests. By 11:40 A.M . the factory

had closed. The striking workers had achieved almost total solidarity among

the 2,000 foreign workers, male and female alike; likewise, the Metalworkers

Union now stepped in to protest the violent police presence.

On the third day, the strike continued, with the morning shift blocking the

factory gates in the early morning light. Several foreign female workers went

into the factory, changed clothes, punched in, and then returned immediately

to the strike. As a result, management, which was still refusing to negotiate,

locked the main gates and, in so doing, locked the women out. According to eyewitnesses, the breakfast break again resulted in solidarity between those striking

in front of the factory gates, who were calling “Al-le-raus!” (“Every one out!”) to

those still inside.86 One participant recalled that, as workers greeted and hugged

each other through the locked gate, they would break into tears and mutual hugs

and the “will to strike remained unbroken.”87 In order to hinder their reunification, management apparently hung a chain about ten meters from the factory

gate, which the workers repeatedly pulled down; twelve female workers even

stood on the chain so that it could not be pulled taut again.88

As the strike entered the fourth day, the women achieved the final turning

point––they won the German skilled workers to their side. As the strike escalated, the strike committee presented the following demands: 1DM more for

all workers, an end to Wage Category II, payment for all days spent on strike,

and no firings.89 These were conditions German and foreign workers alike

could agree upon. The deciding moment was when the most highly skilled

German workers in the factory, those of the tool shop, presented management

with an ultimatum and stopped working at 9 A.M . sharp.90 When the factory

gates opened at 9 A.M ., the solidarity between the German and foreign

workers, which now united all workers against the management, was boisterously celebrated. Eyewitnesses offer a slightly more romantic version of the

same event: The striking women handed each entering worker of the morning

shift a red rose, to which was attached the statement, “We are expecting you

at 9 o’clock.”91 The German-foreign solidarity “was a real blow to the management, who had hoped to break the strike through the loyalty of the German

workers,” reported eyewitnesses. “From that moment on the strike was

won.”92 Telegrams from workers at other factories arrived to express support

and solidarity.93 An eyewitness reported, “Cash donations also arrived.

Everyone stopped working. There were dances for joy as the German and

foreign workers hugged each other. Foreign women fainted. The German

�14

ILWCH, 84, Fall 2013

workers . . . [who were] the skilled labor of the factory, gave an ultimatum to the

management; at 10 A.M . you will have an agreement.”94 In the end, the solidarity

among the workers––male and female, skilled and unskilled, foreign and

native––changed the course of the strike, riding the momentum the foreign

women had already set in motion.

The following morning, the first results of the negotiations were made

known: twelve cents more per hour, effective immediately, and, beginning

January 1, 1974, twenty cents an hour more.95 The results were disappointing,

and a Turkish man called out, “If you stay at twelve cents, we will continue striking for twelve years!”96 The negotiations continued, and at 1 P.M . the chairmen

of the local employers’ association also stepped in to thwart the spread of

workers’ uprisings (strikes had begun breaking out in nearby areas, such as in

Lippstadt).97 By 4 P.M . the decision was announced: Pierburg had eliminated

Light Wage Category II, guaranteed a raise of thirty cents more per hour, and

promised a 200DM cost of living bonus.98 Together these two raises equaled

fifty-three to sixty-five cents more an hour. Those on strike accepted the

terms and declared themselves ready to return to work on Monday.99

However, on Monday, 150 foreign women continued to strike for payment of

the days on strike. Management attempted to block them with trucks and

shouted at them with megaphones. An office window was broken and the

police were called in. Again, the German skilled workers stood up on behalf

of the striking workers until management met their terms. Management

issued a “warning” to those on strike.100 The real warning was to management,

however, which learned through the course of the strike that the division of

German versus foreign was becoming increasingly irrelevant, as the category

of “worker” had expanded to include all.

The Strike’s Impact

In the early 1970s, the Pierburg strike could have served as the perfect case

study. However, it was largely misunderstood or ignored by contemporary feminists and progressive sociologists. The striking women at Pierburg did not

necessarily view their actions in the same ways as their contemporaries,

especially those drawing on negative stereotypes of Mediterranean women. A

1973 report told the story of Anna Satolias, a Greek woman who participated

in the May 1970 strike, declaring at the end that becoming a migrant was a

way for these Mediterranean women to find emancipation. In the article,

Satolias describes her dissatisfaction with her working conditions thusly:

The work went from bad to worse, more production, more work, more workers,

less working space. And the speed: faster and faster, the supervisor and the

foreman shouting at us all the time––all that in the lowest wage category, which

is called “light.” First I joined the trade union––like my husband––then we

women started making demands. We wanted the abolition of Wage Category I,

because the work was and is heavy and not light––and because Category I is

�Her Fight is Your Fight

15

supposed to be only for beginners, although we had been working five or six years

in this category.101

The article continues, pointing out that that same year Pierburg promoted

Anna’s husband, Nikiforus, to the position of toolsetter, and placed him

together with his wife and her colleagues in the machine room. “Perhaps,”

Anna said, “the firm thought we would be more docile then, because I would

have to do what my husband said.102 “Perhaps,” Nikiforus responded, “the

firm thought that as a toolsetter I would earn so much that I could let my

wife stay at home––and there were even colleagues who said such things

aloud.”103 Anna reported incredulously to the West German women’s magazine, Jasmin: “The firm might well have thought that he would leave his wife

at home, and I would obey him.”104 Even though sociologist Kosack centers

her 1973 discussion of the Pierburg strike on the strong figure of Anna

Satolias, her thesis is a nationalistic one: migration to western Europe could

be a step toward emancipation for foreign women. “This is a term [equal

rights] that she [Anna] has learned in Western Germany for the first time.”105

In a troubling way, Kosack locates foreign women’s exploitation in West

Germany solely in their home cultures, which are placed in marked contrast

to that of their host country: “[Migrant women] are virtually their husbands’ servants. Their activities are limited to those typical in their home countries and

indeed for all women in pre-capitalist societies––the kitchen, the children and

the appropriate religious rituals.”106 The sociologist saw the strike as a sign of

a rising tide of women’s liberation movements and a raised consciousness,

especially on the part of migrant women, who through their exploitation in

West Germany had apparently come to realize a new feminist consciousness:

It is the extreme form of discrimination, which makes migrant women fight. They

get much lower pay than male workers, have to suffer authoritarian behavior from

the almost inevitably male foremen and, in addition, have a second day’s work

waiting for them at home––household and children––while their husbands consider it their right to relax after work. This obvious injustice mobilizes many

migrant women against their previously unquestioned position as their husbands’

servants.107

However, to assume that migrant women were necessarily less progressive than

West German women was a fallacy. It was not until 1956 that West German

women were allowed to take jobs without their husbands’ permission.108 This

interpretation fails to take into account migrant women’s unique circumstances,

which compounded gender discrimination and the poor conditions “guest

workers” (both male and female) had experienced in West Germany over the

previous ten years. It was these very foreign women from the Mediterranean,

not West German women, who first instigated successful protests against

sexist wages in West Germany.

�16

ILWCH, 84, Fall 2013

The Pierburg strike also holds important lessons about West German

women’s political consciousness and the West German feminist movement in

the early 1970s. Although foreign women protested the light wage categories

before West German women did, this point was not always remembered. By

1973, West German women had not launched significant challenges to misuses

of Wage Category II. One reporter wrote after the conclusion of the Pierburg

strikes that foreign women’s heightened political consciousness impressed

him, especially when compared to that of German women: “German female

workers of this wage category [II] have neither at the Pierburg factories or elsewhere demonstrated that they were prepared to strike.”109 He continued with an

even more stinging critique: “Among the German women of this wage category

there is unfortunately missing, to a large extent, leadership personalities.” And

yet, despite the significance of the Pierburg strike, it was all too easily forgotten

in the larger narrative of the German women’s movement. It was not until 1978

that media reports on West German women’s efforts to challenge wage categories first appeared and, significantly, they did not reference the Pierburg

strike at all.110 The Pierburg strikes quickly faded from view. In these later

reports, it is a German Industrial baker, Irene Einemann, who is credited as

the first to challenge the sexist use of wage categories:

At long last, in the spring of 1978, Irene Einemann, a female baker’s assistant in

the North German city of Delmenhorst, filed suit demanding that her pay be

brought up to the level of her male colleagues and won the case. Her wage was

raised from the previous DM6.86 per hour to DM8.24 per hour, plus an additional

supplement of DM100 [that] her male counterparts were earning also, and the

decision was made retroactive, with back pay due her as of January 1, 1976.111

When reporting on Einemann, syndicated newspaper commentator Tatjana

Pawlowski, five years after the Pierburg strike, (falsely) credited Einemann as

the first to stop “complaining” and protest her Wage Category: “Injustice

cannot be overcome if justifiable criticism limits itself to complaining . . .Who,

until now, would have had the courage to oppose the long-established wage policies of many industrial enterprises?”112 The courageous actions of the striking

foreign women in 1973 at Pierburg seem to have been forgotten or lost on the

broader West German population.

These lesser-known strikes provide important lessons about solidarity and

the conditions that support it. First, certain homogenizing conditions––such as

poor worker housing and discrimination––promoted solidarity among foreign

workers, uniting even antagonistic national groups such as Turks and Greeks

in new ways. Also workplace sexism, wage differentials, and low representation

among women encouraged solidarity among foreign and native women. Finally,

the solidarity of all workers, despite the union’s disinterest, provided the tipping

point for the illegal Pierburg strike, which challenged the traditional role unions

have played in representing workers and negotiating on their behalf.

�Her Fight is Your Fight

17

The impact of the Pierburg strike and other strikes led by foreign workers

in the early 1970s were not one-dimensional. Indeed, the Pierburg and Ford

strikes were not truly “foreigners’ strikes,” as all of the strikes fundamentally

altered the working conditions, workers’ solidarity, and wage structure of the

entire West German economy by challenging the wage categories and the

exploitation of foreign labor upon which it depended. Significantly, the strikes

drew attention to the long-term effects of labor models that were meant to be

“temporary fixes,” such as the “guest worker” program itself.

Conclusion: Her Fight is Your Fight!

“That is no longer a strike. That is a movement!” declared Federal Chancellor

Willy Brandt about the 1973 “Turkish Strike” at the Cologne Ford plant.113

The Ford management apparently replied with resignation, “Over the years,

we have discovered that foreigners came to us with a much too highly developed

confidence.”114 Both Brandt’s and the Ford management’s comments effectively

invoked the new image of “guest workers” in 1973 West Germany. After more

than a decade of life and work in West Germany, they had indeed developed a

political awareness that was effectively channeled into a successful labor movement. “The power that lay behind such a strike [at Pierburg] in the automobile

parts supply industry demonstrates, for the first time, a real threat to West

Germany’s Fordist production model,” commented journalist Martin Rapp in

2006.115 However, the Pierburg strikes challenged more than just the West

German economic and industrial model. In 1979, economist Martin Slater

reported that foreigners’ successful labor activism––not just the recession of

1973––directly affected employers’ decision to end the recruitment of temporary

foreign labor:

[Foreign] migrants, by the early 1970s, had increasingly come to be regarded as a

. . . political burden . . .[Migrants] had come to be regarded as [a] social liability . . .

[due to their] own political transformation. By the early 1970s, the docile, hardworking migrant of the 1950s and 1960s had apparently transformed into a

radical member of the working class. . . . Following close on the heels of protests

and demonstrations by migrants over their housing conditions, these strikes

were seen by governments as a sure sign that migrants were politically

unreliable.116

In other words, “guest workers’” political consciousness and transformation into

members of a larger, national working class helped to end the exploitative laborrecruitment program. As a result, the official end of the German “guest worker”

programs was in 1973. However, the year 1973 is a false end to the “guest

worker” program, which was in many ways never temporary and never really

ended, as this population continues to impact Germany today.

The narrative of the Pierburg strike is neither a tale of victimization nor a

triumph of good over evil. Rather it tells of an evolution and slow integration of

�18

ILWCH, 84, Fall 2013

a supposedly temporary migrant population into a larger class and national consciousness. Foreign workers’ activism and collective bargaining, which occurred

from the 1960s through 1973, provided an early sign of foreign workers’ commitment to West Germany as their home––a transition occurring earlier than scholars have previously acknowledged.117 Historians have long connected the

decision to stay in West Germany as occurring after the 1973 official end of

recruitment. However, I would argue that foreign workers, who had been

saying for over a decade that they planned to return home, demonstrated

even earlier, through their activism, a more permanent investment in West

German society. Workers’ protests, whether about housing or wages, demonstrated solidarity across nationalities and with West German coworkers alike.

During these strikes, foreign workers participated in German industry as

“German workers” (consciously or not) and impacted German policy even if

they were not officially included in the national polity, calling into question

later conservative claims about foreign workers’ rights to German citizenship.

Foreign workers’ dynamic roles in strikes and protests is not surprising,

considering that workers were not just reacting to poor conditions at work,

but also to poor conditions in employer-managed housing as well as memories

of their deplorable train rides to West Germany and the long and tedious application process that preceded those trips.118 However, material conditions alone

cannot explain labor activism: There was also a more complicated social reality

embedded in “guest workers’” negotiations with their increasingly permanent

lives in West Germany. Labor activism for foreign workers in the 1970s

served an integrating function by combining demands for economic, social,

and, in some cases, legal parity––demands that signaled a claim on “occupational community” and a newfound sense of permanence in West German

society. These strikes raised important questions about who was a de facto

German citizen and “German” worker long before the immigrant population

dominated public political debates.

NOTES

1. “Rebellion am Fließband: Erfahrungen aus Frauenstreiks,” Barbara Schleich, WDR II

December 13, 1973, 15 min.

2. Ibid.

3. “Dossiers: Die Chronik der neuen Frauenbewegung: 1973.” http://www.frauenmediaturm.de/themen-portraets/chronik-der-neuen-frauenbewegung/1973/ (Accessed February 3,

2013).

4. Scholars have argued that multiple identities (e.g., female, foreign) “intersect” to create

unique forms of discrimination. For more on “intersectionality,” see Kimberle Crenshaw,

“Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of

Color,” Stanford Law Review 43 (1991): 1241–99; Philomena Essed, Everyday Racism:

Reports from Women in Two Cultures (Claremont, CA, 1990); Essed, Diversity: Gender,

Color, and Culture (Amherst, MA, 1996); Patricia Hill Collins, Black Feminist Thought:

Knowledge, Consciousness and the Politics of Empowerment (New York, 2000); Chandra

Mohanty, “Under Western Eyes: Feminist Scholarship and Colonial Discourses,” Feminist

Review 30 (1988): 61–88; Gloria Anzaldua, Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza

�Her Fight is Your Fight

19

(San Francisco, 1987); Irene Browne, and Joya Misra, “The Intersection of Gender and Race in

the Labor Market,” Annual Review of Sociology 29 (2003): 487– 513.

5. Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945 (New York, 2005), 324– 55.

6. Duncan Miller and İshan Çetin, Migrant Workers, Wages, and Labor Markets (Istanbul,

1974).

7. Monika Mattes, Gastarbeiterinnen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland: Anwerbepolitik,

Migration und Geschlecht in den 50er bis 70er Jahren (Frankfurt am Main, 2005).

8. Ibid.

9. Miller and Çetin, Migrant Workers; Mattes, 39.

10. John J. Kulczycki, The Foreign Worker and the German Labor Movement: Xenophobia

and Solidarity in the Coal Fields of the Ruhr, 1871–1914 (Berg, 1994); Kulczycki argues against

the idea that ethnic Poles chose between class interests and national consciousness, which

Christoph Klessman terms, “double loyalty” in Klessman, “Zjednoczenie Zawodowe Polskie

(ZZP-Polnische Berufsvereinigung) und Alter Verband im Ruhrgebiet,” Internaltionale

Wissenschaftliche Korrespondenz zur Geschichte der deutschen Arbeiterbewegung 15 (1979):

68; Erhard Lucas, Zwei Formen von Radikalismus in der deutschen Arbeiterbewegung

(Frankfurt am Main, 1976); Lucas, Der bewaffnete Arbeiternaufstand im Ruhrgebiet in seiner

inneren Struktur und in seinem Verhältnis zu den Klassenkämpfen in den verschiedenen

Regionen des Reiches (Frankfurt am Main, 1973).

11. David F. Crew, Town in the Ruhr: A Social History of Bochum (New York, 1986), 181.

12. Karin Hunn, ‘Nächstes Jahr Kehren wir zurück . . . Die Geschichte der türkischen

‘Gastarbeiter’ in der Bundesrepublik (Göttingen, 2005); Gottfried E. Voelker, “More Foreign

Workers––Germany’s Labour Problem No. 1?” in Turkish Workers in Europe, 1960–1975, ed.

Nermin Abadan-Unat (Leiden, 1976), 331–345, here 336; Ulrich Herbert, A History of

Foreign Labor in Germany: Seasonal Workers, Forced Laborers, Guest Workers, trans. William

Templer (Ann Arbor, 1993). Herbert points out that ninety percent of foreign males were bluecollar workers compared with only forty-nine percent of the German male work force, 216.

13. Ulrich Herbert, A History of Foreign Labor, 230.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. Oliver Trede, “Misstrauen, Regulation und Integration: Gewerkschaften und und

‘Gastarbeiter’ in der Bundesrepublik in den 1950er bis 1970er Jahren” in Das “Gastarbeiter”

System: Arbeitsmigration und ihre Folgen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und Westeuropa,

eds. Jochen Oltmer, Axel Kreienbrink, and Carlos Sanz Diaz (Munich, 2012), 183–97.

17. Ibid., 186.

18. Ibid., 188; Hunn, “Die türkischen Arbeitsmigranten und ihre Arbeitgeber,” in Nächest

Jahr, 101–136.

19. Manuela Bojadzijev, Die windige Internationale: Rassismus und Kämpfe der Migration

(Münster, 2008), 151.

20. Der Bundesminister für Arbeit und Sozialordnung, Bonn, an BAVAV Nürnberg, 2. Mai

1962, BArch B119/3071 II.

21. Ibid.

22. Giacomo Maturi, Willi Baumgartner, Stefan Bobolis, Konstantin Kustas, Vittorio

Bedolli, Guillermo Arrillage, and Sümer Göksuyer, eds., Hallo Mustafa! Günther Türk

arkadaşı ile konuşuyor (Heidelberg, 1966), 22.

23. Ibid.

24. Hunn, Nächest Jahr, 117.

25. Herbert, A History of Foreign Labor, 241.

26. Ali Gitmez, Göçmen İşçilerin Dönüşü: Return Migration of Türkish Workers to Three

Selected Regions (Ankara, 1977), 81.

27. Edith Schmidt and David Wittenberg, “Pierburg: Ihr Kampf ist Unser Kampf” (West

Germany, 1974/75), 49’ (motion picture).

28. Ibid.

29. Ausburger Allgemeine, August 22, 1973.

30. “Akort nedir?” Eilermark’a Hoş geldiniz: Türk İşçi Arkadaşlarımız için Kılavuz,

Eilermark AG, Spinnerei u. Zwirnerei, Gronau, (2 May 1973, Milli Kütüphanesi 5262, DM

4671– 73), 17–19.

31. Ibid., 17– 18.

32. Author’s interview, “F,” Berlin 2003.

�20

ILWCH, 84, Fall 2013

33. Mathilde Jamin reports that Turkish workers worked faster than their West German

coworkers, who complained that they were “spoiling the Akkord.” “Migrationserfarungen,”

in Fremde Heimat: Eine Geschichte der Einwanderung/Yaban, Sılan olur, eds. Aytaç Eryılmaz

and Mathilde Jamin (Essen, 1998), 216.

34. Hunn, “Die Rezession von 1966/67: Auswirkungen und Reaktionen” in Nächstes Jahr,

188– 202.

35. Ibid.

36. “Schwerpunkte, Aufmass und Verlauf der Streikbewegung” in Spontane Streiks 1973,

Krise der Gewerkschaftspolitik, Redaktionskollektiv ‘express,’ edition, eds. Reihe Betrieb und

Gewerkschaften (Offenbach, 1974), 22. This is a published source complied by the collective,

express Zeitung für sozialistische Betriebs und Gewerkschaftsarbeit, in which the editors collected strike materials and interviewed participants of the strikes during the year 1973.

37. Spontane Streiks, 18.

38. Hans Schuster, “Wilde Streiks als Warnsignal,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, September 13,

1969; “Streikbewegung greift auf den Bergbau über: Tarifgespräche schon in dieser Woche,“

General-Anzeiger für Bonn und Umgebungen, September 8, 1969; “Streikbewegung greift auf

den Bergbau uber: Eisen erkaltet im Hochofen,” Westdeutsche Rundschau Wuppertal,

September 8, 1969; Wilhem Throm, “Wilde Streiks treffen die Gewerkschaften,” Frankfurter

Allgemeine Zeitung, September 8, 1969; “Eine große Lohnwelle kündigt sich an: Die

Stahlarbeiter fordern 14 Prozent mehr,” Franfurter Allgemeine, September 8, 1969;

“Lohnverhandlung am Donnerstag,” Solinger Tagblatt, September 8, 1969; “Auch im

Bergbau . . .” Butzbacher Zeitung, September 8, 1969; “Jetzt Streiks um Bergbau: Neue

Lohnforderungen im Rheinland,” Hannoversche Rundschau, September 9, 1969; “Wilde

Streikwelle nun auch im Saar-Bergbau: Tarifpartner bemühen sich um schnelle

Entspannung,” Ludwigsburger Kreiszeitung, September 9, 1969.

39. Ibid.

40. “Streik bei Hella, Lippstadt,” in Spontane Streiks, 75.

41. “Du schon machen gut!” [sic], Ibid.

42. “Streik bei Mannesmann, Duisburg-Huckingen,” in Spontane Streiks, 64.

43. Ibid., 63.

44. Ibid.

45. “Die Türken probten den Aufstand,” Die Zeit, September 7, 1973.

46. Strikes over vacation time for foreign workers were common across West Germany, as

when 1,600 Portuguese workers at the Karmann factory and 250 Spanish workers in Wiesloch

went on strike to argue for the right to use their vacation days contiguously. “Zur Rolle der

Ausländischen Arbeiter,” in Spontane Streiks, 30.

47. “Einwanderung und Selbstbewusstsein: Der Fordstreik 1973,” in Geschichte und

Gedächtnis in der Einwanderungsgesellschaft: Migration zwischen historishcer Rekonstruktion

und Erinnerungspolitik, eds. Jan Motte and Rainer Ohliger (Essen, 2004); Der Spiegel,

September 3, 1973; Karin Hunn, “Der ‘Türkenstreik’ bei Ford von August 1973: Verlauf und

Analyse” and “Die zeitgenössischen Deutungen des Fordstreiks und dessen Konsequenzen

für die türkischen Arbeitnehmer,” in Nächstes Jahr, 243 –261; Manuela Bojadzijev, Die

windige Internationale, 157– 162.

48. “Die Türken probten den Aufstand,” Die Zeit, September 7, 1973.

49. “Beispiele für Maßregelungen,” in Spontane Streiks, 46; Hans-Günter Kleff,

“Täuschung, Selbsttäuschung, Enttäuschung und Lernen: Anmerkungen zum Fordstreik im

Jahre 1973” in Geschichte und Gedächtnis, 251– 259.

50. “Die Türken probten den Aufstand,” Die Zeit, September 7, 1973.

51. “Frauen im Beruf: Arbeiten und kuschen,” Stern, 1973.

52. Ute Frevert, Women in German History: From Bourgeois Emancipation to Sexual

Liberation, trans. Stuart McKinnon-Even, Terry Bond and Barbara Norden (New York,

1989), 279.

53. Harry Shaffer, Women in the Two Germanies: A Comparative Study of Socialist and

Non-Socialist Society (New York, 1981), 100.

54. W. Rohmert and J. Rutenfranz, Arbeitswissenschaftliche Beurteilung der Belastung und

Beanspruchung an unterschiedlichen industriellen Arbeitsplätzen (Berlin, 1975).

55. “Lohntarifvertrag vom 2.6.1965 für die gewerblichen Arbeitnehmer der feinkeramischen Industrie,” Bayern quoted in, BAVAV Türkei an BAVAV Nürnberg 7.12.1965

BArch B 119/3073.

�Her Fight is Your Fight

21

56. For a comparison of similar cases in the United States against discriminatory protective

legislation, see J. Ralph Lindgren et al., The Law of Sex Discrimination (Boston, 2011).

57. “Es geht nicht ohne Italiener,” Industriekurier, October 4, 1955, quoted in Herbert,

A History of Foreign Labor, 206.

58. For a reference to recruiters’ demands specifically for female foreign workers, see

“Wochenbericht der deutschen Verbindungsstelle in der Türkei,” November 1969 BArch B

119/4031; Berlin Aa10. November 1965, “Informationsbesuch bei der Firma Sarotti AG”

Landesarchiv Berlin, B Rep 301 Nr 297 Acc 2879 “Arbeitsmarktpolitik.”

59. Pierburg-Neuss: Deutsche und Ausländische Arbeiter––Ein Gegner- Ein Kampf/ Alman

ve Meslektaslar Tek Rakıp tek Mücadele, Streikverlauf, Vorgeschichte, Analyse, Dokumentation,

Nach dem Streik (Internationale Sozialistsche Publikationen, 1974) DoMit Archive, Sig. No.

1177, 6.

60. Ibid., 167.

61. These numbers vary slightly, depending on the source. Bojadzijev bases her numbers

on information provided by the union, in Die windige Internationale, 163.

62. Hildebrandt and Olle, 39.

63. Godula Kosack, “Migrant Women: The Move to Western Europe––a Step towards

Emancipation?” Race and Class 70 (1976): 374 –75.

64. “Interview mit einem Betriebsratmitglied über die Arbeitskonflikte Ausländischer

Arbeiter bei Pierburg Neuss im Februar 1975,” in Ihr Kampf ist Unser Kampf: Ursachen,

Verlauf und Perspektiven der Ausländerstreiks 1973 in der BRD (Teil I),eds. Eckart

Hildebrandt and Werner Olle (Offenbach, 1975), 155; The source, Pierburg-Neuss: Deutsche

und Ausländische Arbeiter, cites the number as 400 Yugoslavian women, 6.

65. Ibid., 155.

66. Ibid., 37.

67. Deutsche Volkszeitung, May 29, 1970.

68. Ibid.

69. Hildebrandt and Olle, 37.

70. Deutsche Volkszeitung, May 29, 1970.

71. “Forderungen der Beschäftigten der Versammlung der Belegsscahftsmitglieder der

Firma Pierburg,” DoMit Archive Pierburg File.

72. Multilingual Flier, referring to the June 7 –8, 1973 Strike. DoMiT Archive, Pierburg

File.

73. Ibid.

74. Kosack, 375.

75. “Telefonnotiz,” June 14, 1973 in “Telefongespräch mit Herrn Prof. Pierburg am 14. Juni

1973 nach 16 Uhr,” Neuss, June 15, 1973, DoMit Pierburg File.

76. Hildebrandt and Olle, 38.

77. “IG Metall: Gastarbeiter Nicht Diskriminiert: Der Streik bei Pierburg in Neuss ist

illegal,” Handesblatt August 17–18, 1983.

78. Micheal Geuenich, Industriegewerkschat Metall, F. D. Bundesrepublik Deutschland,

Verwaltungsstelle Neuss-Grevenbroich August 15, 1973 in “Flugblatt-Dokumentation” in

Pierburg-Neuss: Deutsche und Ausländische Arbeiter––Ein Gegner- Ein Kampf, 27; DoMiT

Archive, Pierburg file.

79. Ibid.

80. The narrative of the Pierburg strike is told by the striking workers themselves. A socialist industry and union publication collective, named “express,” documented strikes across West

Germany, focusing on fourteen different companies and published their findings in 1974 to

make sure that the strikes entered the historical record. They remain the voice of the strikes.

See “Pierburg” in Reihe Betrieb und Gewerkschaften: Redaktionskollektiv ‘express,’ editions,

Spontane Streiks 1973 Krise der Gewerkschaftspolitik” (Verlag 2000 GmbH, Januar 1974).

Other scholars drawing on this material include Eckart Hildebrandt and Werner Olle, Ihr

Kamf ist unser Kampf. Ursachen, Verlauf und Perspektiven der Ausländerstreiks 1973 in der

BRD. Teil I, (Offenbach, 1975); Manuela Bojadzijev, Die windige Internationale: Rassismus

und Kämpfe der Migration (Münster, 2008).

81. “Pierburg” in Reihe Betrieb und Gewerkschaften: Redaktionskollektiv ‘express,’

editions, Spontane Streiks 1973 Krise der Gewerkschaftspolitik (Verlag 2000 GmbH, Januar

1974), 79.

82. Ibid.

�22

ILWCH, 84, Fall 2013

83. Hildebrandt and Olle, 40.

84. Ibid.

85. “Frauen im Beruf: Arbeiter und kuschen,” Stern, October 25, 1973, no. 44, 84.

86. Hildebrandt and Olle, 40.

87. “Strike bei Pierburg Neuss,” Spontane Streiks 1973, 80.

88. Ibid.

89. Hildebrandt and Olle, 40.

90. Ibid.

91. “Strike bei Pierburg Neuss”; Godula Kosack, 375; The DoMiT Archive Pierburg file

contains a dried rose from the strike.

92. Ibid.

93. Ibid; Hildebrandt and Olle, 40.

94. “Streik Bei Pierbrug Neuss,” 80.

95. “Streik bei Pierburg Neuss,” 81.

96. Ibid.

97. Ibid.

98. Ibid.

99. “Keine Ruhe nach dem Streik: Wieder kurze Arbeitsniederlegung, wieder Polizei vor

dem Werkstor,” Kölner Stadtanzeiger, August 22, 1973; “Unternehmensleitung in Neuss glaubt

an politische Motive: ‘Streik war von außen gesteuert,’” Frankfurter Rundschau, August 22,

1973.

100. Hildebrandt and Olle, 41.

101. Quoted in Kosack, 376; See also, “Anna, geh du voran,” Jasmin (1973); See also

Barbara Schleich, “Streik am laufenden Band: In der Vergaserfirma Pierburg streikten vor

allem ausländische Arbeiterinnen,” Vorwärts, August 25, 1973.

102. Kosack, 376.

103. Ibid.

104. “Anna, geh du voran: Anna Satolias––die Geschichte einer griechischen

Gastarbeiterin, die Sprecherin der Frauen in einem deutschen Betrieb wurde,” Jasmin 20

(1973).

105. Kosack, 376.

106. Ibid., 369.

107. Ibid.

108. Wiebke Buchholz-Will, “Wann wird aus diesem Traum Wirklichkeit? Die

gewerkschaftliche Frauenarbeit in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland,” in Geschichte Der

Deutschen Frauen Bewegung, ed. Florence Herve (Cologne, 1995), 185–208.

109. Augsburger Allgemeine, August 22, 1973.

110. Harry Shaffer, Women in the Two Germanies: A Comparative Study of A Socialist and

Non-Socialist Society (New York, 1981).

111. Ibid., 101– 102.

112. Ibid.

113. “Das ist kein Streik mehr, das ist eine Bewegung,” Martin Rapp and Marion von Osten

“Ihr Kampft ist unser Kampf,” Bildpunkt: Zeitschrift der IG Bildende Kunst (2006), 23.

114. Ibid.

115. Ibid.

116. Martin Slater, “Migrant Employment, Recessions, and Return Migration: Some

Consequences for Migration Policy and Development,” Studies in Comparative International

Development 14 (1979): 4, emphasis added.

117. Ursula Mehrländer, “The Second Generation of Migrant Workers in Germany:

The Transition from School to Work,” in Education and the Integration of Ethnic Minorities,

eds. D. Rothermund and J. Simon (London, 1986), 12– 24.

118. Jennifer Miller, “On Track for West Germany,” German History: The Journal of the

German History Society 30 (2012): 550– 73.

�

Jennifer Miller

Jennifer Miller