ESHET 2022

AISPE session "Women and economic thought in Italy (1850-1950)"

POLITICAL ECONOMY IN THE SALON OF EMILIA TOSCANELLI PERUZZI

Monika Poettinger

ABSTRACT

Emilia Toscanelli Peruzzi (1827-1900), from the high bourgeoisie of Pisa, married, in 1850,

Ubaldino Peruzzi, scion of an ancient Florentine family, politically active in the Grand Duchy of

Tuscany as in the later unified Italy. Conscious of her role in strengthening her husband’s position,

she immediately opened the salon of the Florentine mansion to politicians, literates, bankers and

whomever she deemed might contribute to a lively discourse. Her correspondence followed up

the discussions held in the salon and with its consistency of ten thousands of letters constitutes

today a precious archival source for the understanding the critical role of salons in the Italian

political and cultural scene of the second half of the nineteenth century. At that time the

professionalisation of economists was still in its infancy and the salon Peruzzi was crucial in the

formation of several young economists – lato sensu - who would later hold important positions in

academia, in the administration of the Italian state and in major companies. While the case of

Vilfredo Pareto has been researched, a general evaluation of the influence of Emilia Peruzzi on

Italian political economy is still lacking.

This paper will firstly reconstruct the economic ideas of Emilia Peruzzi herself, as related to the

environment in which she grew up and her marriage with Ubaldino. Then, the analysis will

encompass the wide network of friends and correspondents that Emilia built in time, trying to

understand the logic of its functioning and the use that both Emilia and Ubaldino made of it. After

1871 Emilia dedicated her attention increasingly to a young generation of protégés, selected by

Ubaldino but nurtured by her to become a political élite alien to the logic of parties but of high

morals and profound culture. In the same years Ubaldino switched his attention to political

economy and so, these young protégés, all born in the 1840s, increasingly studied and anlysed

economic and social questions. Among them: Vilfredo Pareto, Sidney Sonnino, Carlo Fontanelli and

Francesco Genala. While the political mission of the salon, salvaging liberalism and political

representativeness, was lost, a major legacy consisted in the habit to analyse questions based on

accurate empirical studies.

�THE ECONOMY FOR A 19TH CENTURY WOMAN OF THE TUSCAN ELITE

Emilia Toscanelli Peruzzi (1827-1900) 1 was born in Pisa into the wealthy bourgeois family of the

Toscanelli (Menconi 2005). The family of small building contractors had migrated from Canton

Ticino to Tuscany in the last decades of the 18th century and had made a fortune during the

Napoleonic occupation. Emilia’s mother, Angiola Cipriani, had been quite instrumental in this

ascent, since her family, of Corsican origin, was acquainted and related to the Bonaparte family.

Already in 1810, Giovanni Battista Toscanelli had been able to acquire the stately villa La Cava in

the countryside of Pontedera. In the same year of the birth of Emilia, then, her father bought the

prestigious palazzo Lanfranchi Chiccoli on the Lungarno Mediceo, the best possible address in Pisa.

After the death of her mother, at the age of sixteen Emilia reigned over these two mansions 2 and

supervised the entertainment activity that collected there many intellectuals from the university

of Pisa and many a young patriot, friend to the two brothers of Emilia: Giuseppe and Domenico

who actively contributed to the Italian independence movement. As a young lady, Emilia learnt

foreign languages – French, English and German – practiced sports and enjoyed reading literary

works (Benucci 2007, p.XI) but in her twenties, the involvement of her family, friends and

acquaintances in revolutionary activities definitively moved her attention toward politics (Soldani

2002; Benucci 2007 pp.CV-CXVIII).

Her diaries, only scantily preserved (Toscanelli Peruzzi 1922, Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007), give an

insight over these early years. In 1847, aged 20, Emilia would write down: “Let’s defy the bad

opinion others have of us, the greatest obstacle to our risorgimento; let’s unite for the love of our

country and of ourselves. We will be strong, we will be formidable, we will be grand. Yes, all of us,

brothers from the Alps to Lilibeo, all united in the same scope, in the same idea: independence,

Italy as a nation. May this not only be a dream, but a reality, may I see it come true” (Toscanelli

Peruzzi 1922, p.153). During the upheavals of 1848, Emilia read all possible newspapers and cried

and quivered over the results of battles and uprisings (Toscanelli Peruzzi 1922, p.161). The

1

No complete biography exists of Emilia Toscanelli Peruzzi. Major sources still consist of obituaries and the sparse

remembrances of family and friends (Benucci 2007, pp.XX-XXI). For a more recent, brief, appraisal, see: Cuccoli 1966.

2

In 1845 she wrote in her diary: “I speak frankly and in abundance, I act ardently. In a bad mood or when I’m excited, I

might be pungent, but I immediately repent and if i would offend someone I would not shy from offering my excuses.

That has never happened to this day and whenever offended I excused, and I never held a grudge or looked for

vengeance. I will never be able to hate or to wish evil on someone. I like to command and not to obey. I usually do

what I wish, and I don’t like to be opposed. The absence of our mother has made out of us independent women, since

our father is almost never at home and he leaves petty decisions to us, only influencing the big ones. Usually, we know

when to ask for permission and our father tries to accommodate our wishes anyway. I fear I am a little spoiled since

the cases in which father denies me I am not happy at all. Poor me if I should marry an intransigent man, I would have

many a bitter pill to swallow!” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 1922, pp.131-132).

�passionate tone of her diary entries, though, must not deceive. She analysed the political and

military situation with rational understanding and strategic vision. Her brothers, on the front in the

north of Italy, sent home precise reports on the numbers of soldiers and military equipment on

each side, other data was retrieved from newspapers and asked for to corresponding friends 3.

Emilia also had, already, a very precise political stance. She defined herself a liberal and a

constitutionalist (Toscanelli Peruzzi 1922, p.301). Republican and democratic endeavours, let alone

popular revolutions were condemned and even considered one of the causes for the failing of the

1848 attempt at unifying Italy. Giuseppe Mazzini, the Giovane Italia and Francesco Domenico

Guerrazzi were all harshly judged. After 1848, she wrote: “The righteous man cries: “I’m not a

democrat”, and means: “I’m not guilty” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 1922, p.312).

While Emilia’s political credo was already set in her teenage years, informed by the stance of her

family, her ideas about the economy received a clear definition only after her marriage in 1850.

Before, the only entry regarding liberalism concerned the famous Cobdenian tour of Italy in 1847.

At the time, while demonstrations in favour of liberty were repressed, as Emilia duly noted in her

diary, acclaiming free trade was acceptable, making liberalism one of the legitimate claims that

patriots could pursue4: “in absence of other liberties, having the freedom of trade is still

something” (Peruzzi 2007, p.93). The 13th of May 1847, Emilia wrote: “Today there is a great

banquet at Ardenza in honour of Richard Cobden. From Pisa the professors Montanelli, Regny and

Castinelli have gone there to participate, as did the jurist Dell’Hoste. Cobden, the English

defendant of free trade has been welcomed in Italy with great enthusiasm. In Genoa, Rome,

Naples, Bologna, Florence and now Livorno great banquets have been organised for him. On these

occasions important men have pronounced speeches in favour of free trade” (Toscanelli Peruzzi

1922, p.154). Unregistered by her diaries, the banquet in Florence, held days before, the 2nd of

May, had been hosted by the then mayor – gonfaloniere – of the city, Vincenzo Peruzzi (Arcangeli,

1848). On this occasion Cobden himself had admitted the ground-breaking role of Tuscany in

embracing free trade much in advance of the rest of the world, England included (Anonymous

1847). The reforms of Pietro Leopoldo, in fact, had liberalised, since the 1780s, many aspects of

the Tuscan economy, allowing the free import and export of agricultural products and the sale of

3

The usage to circulate letters containing information about war efforts was diffused. In the case of the Crimean war,

for example, Emilia received “second-hand” letters of the Piedmontese officer Agostino Petitti through her uncle

Pietro Torrigiani (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p. 56 and p.65).

4

See: Poettinger 2017, pp.193-194.

�land through the abolition of the fideicommissum: this the content of the speech held in front of

the 110 guests by the banker and industrialist Emanuele Fenzi (Ibid.).

The brothers Carlo and Emanuele Fenzi were family acquaintances of the Toscanellis, and, as most

of the Tuscan élite, shared the liberal view of the economy supported by the reigning Lorena

family. Emanuele became, as seen, a veritable champion of free trade and endorsed the then

current plan for a trade union among Italian states on the example of the German one, an

economic union that could become the base for an Italian political federation, led by the Pope.

Emanuele Fenzi also played a pivotal role in the modernisation of the Tuscan economy. He

financed both the main railway and tramway lines and the first tentative ventures for the

extraction of iron and combustible material needed to produce rails and mechanical components

for the emerging railway industry. This part of the Tuscan economy, the emerging industrial

ventures, was mainly alien to Emilia until the encounter with Ubaldino Peruzzi (1822-1891), son of

Vincenzo, who followed in the paternal steps and became gonfaloniere of Florence at a very young

age. As such he was presented to Emilia in the salon of Carlotta Marchesini Torrigiani. While in the

diary entry of the 10th of March 1850 Emilia recounts this as a casual event (Benucci 2007 p.XXVII),

the reality of what would become a love match was more complex. According to Emilia’s own

writings, the choice of the spouse was not something to be left to pure romanticism. Commenting

the wedding of a friend, in 1846, she wrote about a choice that determined future perspectives

(Toscanelli Peruzzi 1922, p.136). On the contrary, a great love could easily and rapidly fade, as in

the case of Massimo d’Azeglio (Toscanelli Peruzzi 1922, p.137). A good impression and a personal

inclination were essential to cement a good marriage, but common beliefs, goals and aspirations

were likewise necessary. A little help in such a momentous choice might be useful and welcome. In

the case of Emilia and Ubaldino the matchmakers were members of the Torrigiani family, one of

the most prominent in Florence, to which both youngsters were directly related. Believing that the

characters, perspectives, and inclinations of Emilia and Ubaldino would be a good match, they

arranged a meeting. The wedding was celebrated in the very same year.

According to a superficial scrutiny, the marriage between Emilia and Ubaldino appears to be a

classic match between a rich merchants’ daughter of recent acquired nobility and the scion of a

family of ancient lineage but little wealth. Emilia would so be the one used to discussing trade,

speculations and innovative ventures, by precisely weighing costs and benefits, while Ubaldino

should have been the idle nobleman with good connections but no practical capabilities. To the

contrary, the diaries of Emilia show a young lady whose family had chosen to leave behind trade

�and embrace the life of landed proprietors, while Ubaldino had been educated to be a driving

force behind the modernisation of Tuscany. After attending the renown liceo Cicognini in Prato,

Ubaldino had obtained, at the age of 18, a degree in law at the university of Siena, but his family

insisted at that point that he should move to Paris to study in the prestigious École des mines. The

elders of the noble but impoverished Peruzzi family, in fact, and specifically his father, Vincenzo,

who had invested in many of the new stock companies, wanted Ubaldino to become a mining

engineer so that he could take advantage of a sector that would blossom in the wake of the

modernisation of the economy5. After his degree, Ubaldino returned home enthusiastically

reporting of the changes he had witnessed in Paris: the gigantic public works and the sprouting of

railway lines. Ubaldino, then, went on to Germany, where he visited mines and manufactures,

extensively relating his findings to the Accademia dei Georgofili (Peruzzi 1846, Peruzzi 1848), the

most important discussion forum for economic issues in Florence. The premature death of his

father and the precipitating events of 1848 steered Ubaldino’s career, as seen, toward politics.

After the return of the Lorena family, accompanied by the invasion of Austrian military forces,

Ubaldino briefly acted as gonfaloniere of Florence, but in 1850, only days after his marriage, he

was deposed in consequence of his opposition to the disbandment of the Parliament imposed by

the Austrians. As many of his peers, he decided to leave the active political scene, de facto

withdrawing the long-standing support of the local nobility to the reigning family. After the

dismissal, thanks to the enormous dowry brought by Emilia, 300.000 Lire, the couple, financially

independent, travelled6, visited friends and family, leaving a quiet life. Ubaldino, though, did not

remain idle. He firstly applied new scientific methods to the managing of his landed properties. In

May 1854 Emilia registered in her diary that her husband was completing a statistical work on

Tuscany’s farmers (Peruzzi 1857) for his former professor at the École des mines, Pierre-GuillaumeFrederic Le Play (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.9) a founding father of French sociology. Ubaldino, in

fact, participated to a generalised European study, based on the new analytical method of Le

Play7, to measure the living standards of the working class (Le Play 1855), contributing an

5

Ubaldino came back from Paris, where he lived with his uncle, diplomatic representant of the Grand Duke at the

French court, with more than a technical education. He created long lasting relationships among the French liberal

and technocratic elite. Instrumental in this sense was the prestigious school he attended. There he gained the

friendship of fellow students like Pierre Paul Ernest vicomte Benoist D'Azy (1824-1898) and of his professor PierreGuillaume-Frederic Le Play (1806-1882).

6

In 1851 the couple visited Paris, while in 1853 they went to Venice (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p. 7). In 1855 they were

again in Paris (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.107).

7

Le Play founded, in 1856, the Société internationale des études pratiques d'économie sociale to spread his statistical

method for the social sciences (Le Play 1879). He also obtained political recognition for his pioneering work and was

held in the highest regard by Napoleon III. Politically he was a reactionary and that costed him future recognition as

�exceptionally analytical analysis of the Tuscan sharecropper (Peruzzi 1877). Ubaldino could also

finally express his passion for the railway sector, having been nominated, in 1853, director of the

Leopolda, the line that connected Florence with Pisa and Livorno, a position he would maintain

until 1861. “Ubaldino manages a great estate and directs all his energies in industrial ventures”

wrote Emilia in her diary in July 1856 (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.139).

Only after her marriage, then, Emilia was introduced at the centre of economic change and started

to learn and discuss about economic questions. The 11th April 1856, for example, Emilia wrote in

her diary: “On the road conversation with Ubaldino on the real estate- and land-credit and on

mortgage loans – new banking institutions that are to be introduced also here [in Tuscany]”

(Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.83). The new awareness was not limited to the intercourse with her

husband. Many Tuscan notables, having abandoned the political scene, dedicated their efforts to

the modernisation of the economy (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.139). Another figure that influenced

her in the first marriage years was that of a cousin, though senior in years, of Ubadino Peruzzi:

Bettino Ricasoli. Ricasoli, a Baron of ancient lineage, had suffered the same fate as the Peruzzis

and, impoverished, had dedicated himself to restoring the family fortunes by applying scientific

methods to the agriculture and viticulture in the Chianti region, where he possessed a great estate

around the castle of Brolio (Poettinger 2019). When Emilia got acquainted with him, Bettino

Ricasoli had already been successful in his endeavour and had risen to be the leading political

figure of the Tuscan élite. The setback in local politics after 1848 had not dampened his factual

energy. In November 1855, Emilia wrote down: “Now Bettino goes to the Maremma; he has

bought land and house; he has also procured machines of all kinds from France and England and

will try them out. He needs action. For the country there is nothing to be done in the sphere of

high politics and in Brolio his mission has been accomplished; so Maremma it is: another type of

agriculture, other experiments that if successful will benefit all of Tuscany. But for all of this to be

achieved he needs to be there, his control is needed over the working men, and he will bury

himself in that desert, he will pass there all winter, and, worse, also the pernicious time of harvest,

when the reaping and threshing machines will be in use. Here is a man who succeeds or dies: he

possesses an iron will that is rare in our days; he has a patient and persevering nature that sees

the obstacle, measures it and overcomes it, or at least has the courage and merit to try”

(Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p. 71). Just half a page and Emilia perfectly depicted the struggle of

one of the founding fathers of French sociology. Only recently, with the spreading of structuralism, his analysis on

family structures has been rediscovered and appreciated for its worth (Augustine 1989, pp. 103-109).

�modernising the Tuscan economy by Schumpeterian heroes (Barsanti 2010), a struggle that could

be mortal, since the Maremma plain was marshy and plagued by malaria. Bettino Ricasoli, in fact,

caught the terrible fever in July 1856 (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.145), as Emilia duly registered: “I

found Bettino with the traces of the malady on his face – but nonetheless he did not change his

resolve. I did not address the issue because I didn’t want to touch a hurtful subject. When a man is

miserable, he looks for an optimal occupation, something that won’t leave him alone with himself”

(Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.161).

The efforts of Bettino Ricasoli and his brother Vincenzo in the Maremma were not successful. The

difficulty in finding specialised workers, the hostility of the local farmers, leading to episodes of

luddism, the impossibility for the local mechanical factory to produce and repair machines with

the cast iron available at the time in the Grand Duchy of Tuscany made the endeavour of the

brothers uneconomical. The big estates were so subdivided into smaller pieces of land, each

managed by a farm, lent to one family. It would take time, the development of an efficient iron

industry, the drying of the marshlands and the emerging of a modern workforce to allow the

intensive exploitation of the Maremma. Nonetheless, transferring the efforts of the Tuscan élite

into industrial pursuits obtained its goal. Emilia, always attentive toward the subtle changes in

political equilibria, discussed these results at length in her diaries in June 1856. The humiliation of

being deprived of political representativeness suffered by the Tuscan nobility after the return of

Leopoldo II was vindicated by the visibility and influence gained on economic ground (Toscanelli

Peruzzi 2007, pp.126-128). Among the receivers of the medal for industrial merits were, on this

occasion, Bettino Ricasoli, Cosimo Ridolfi and Antonio Salvagnoli, all - duly noted Emilia adherents to the party of constitutionalists. Only Raffaello Lambruschini could not obtain an

invitation to the court, despite his undeniable innovativeness in agriculture and industry, for the

opposition of the Church, sparked by his “protestant” stance. A good sign, in the eyes of Emilia,

who wrote: “Whenever Austrians and the clerical party show fear and react, the liberal party stirs

and resurges, also in Tuscany” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.127). In the same diary entry Emilia

extensively reported on the state of the Tuscan economy, a topic that had become the centre of

the debate between the prime minister, Giovanni Baldasseroni, and the clerical party. The

repeated failing of many crops due to climatic reasons and the new fungal diseases that affected

the precious vineyards had caused a decisive drop in tax income and consequently an increased

disorder in the finances of the state. “The biggest landed proprietors are in trouble; the little ones

are ruined. The countryside, once a quiet, joyous, and secure place is now full of thefts and

�disorder. (…) Public works are not enough to counterbalance this state of things” (Toscanelli

Peruzzi 2007, p.128). While the drying of marshlands was proceeding slowly, the enormous works

started to enlarge the port of Livorno were heftily criticised by engineers and politicians alike as a

waste of funds. At this point, Emilia did not shy to express a personal opinion on the question. She

did not approve the general criticism: to appreciate the economic results of the public works,

particularly of those in Livorno, more time was needed (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.129).

All in all, during the first decade of her marriage, the view that Emilia had of economic matters

was fairly conventional, notwithstanding the influence of Ubaldino Peruzzi. Ubaldino himself, as

seen, although enthusiastic about new technologies and industrial innovation, was, in the political

sphere, a conservative prone on cautious reforms. This general view of things was not changed by

the extensive travelling of the couple8 or by the knowledge gathered through friends,

conversations, or readings. If possible, these experiences reinforced their conventional wisdom.

Modernity had its positive sides, one of the foremost being the beloved railways. “Easy transports

are a means to multiplying the existence” wrote Emilia in 1854 (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.8). She

also registered with surprise how the line from Livorno to Florence, built to enhance the trading

activity of the Grand Duchy, had rapidly become a way for Tuscans to reach the seaside and enjoy

a day or two of vacations. Emilia called these the “trains of pleasure” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007,

p.141), transporting thousands of newly become tourists on Sundays during the summer season.

Modernity, though, had also some perils, brought about by the rapid changes in the economy. One

of the rare readings of Emilia was so dedicated, in August 1856, to the comedy “La Bourse” by

Francois Ponsard (1856) and to a satirical piece by Louis Veron (1856) on the life of the new

millionaires, both dedicated to the moral condemnation of easy earnings (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007,

p.155). A moral judgement that Emilia would apply also in respect to her brother, who squandered

the family fortune in risky ventures and in opaque affairs linked with the scandal of the Italian

emission banks, which ultimately led to the abolition of the convertibility in gold of the Lira in

1866. Morality was, in this case but always, for Emilia, the rule on which to measure economic

activities. She wrote to her brother: “The issue of Banks is a serious question for the huge amount

of circulating capital involved and you as all rentiers could find yourself in a disastrous situation.

8

Every year the couple organised a travel abroad. Paris was a recurrent destination, but Ubaldino also extensively

visited Spain, having left Emilia in Paris, in 1862, and in 1869 the couple was invited by the Kedivè of Egypt to the

opening of the Suez canal (Toscanelli Peruzzi 1922, p.28). On the interesting observations of Ubaldino about the

economic situation of Spain, see: Ragozzino 2013, pp.74-75. On Egypt, see the joyous letter of Emilia to her sister-inlaw Vittoria: Ragozzino 2013, pp.199-200. In 1873 the couple visited Sweden (Pareto 1968a, p.253), in 1874

Switzerland (Pareto 1968a, p.394).

�Sell your share, all of you should sell your shares, but for God’s sake take yourself out of the peril

represented by the Banks. You already had many debts, you had to sell the family villa in Livorno,

you speculated and threw yourself, for electoral reasons, in a business that is even more delicate

for a member of the local government as you are. This is dangerous for your and your children’s

patrimony” (Ragozzino 2013, pp.221-222).

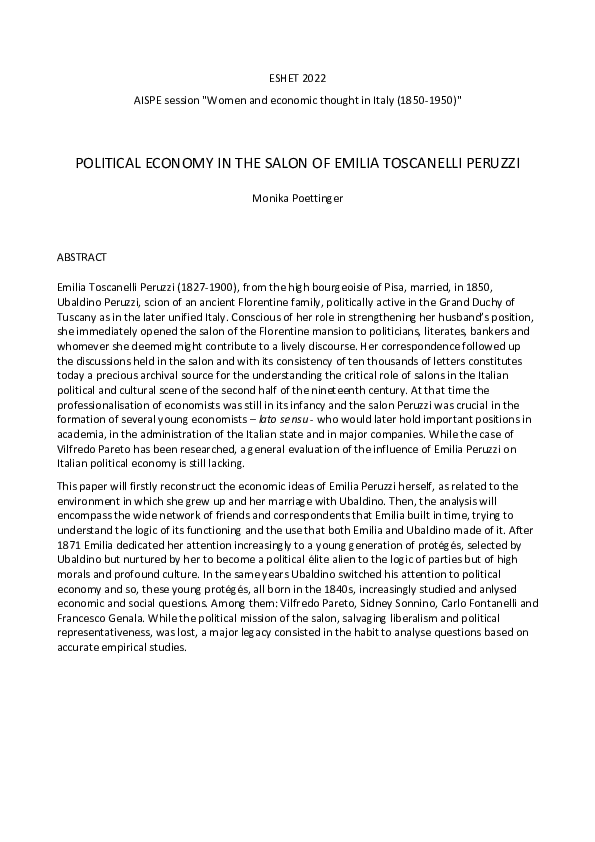

Fig. 1 Emilia Peruzzi in a caricature of the early 1860s. Emilia is, interestingly, characterised as a

woman with political interests, wielding power in the form of a muff representing a document

folder inscribed with the ministerial post held by Ubaldino at the time, the ministry of internal

affairs.

�PARETO AND A 19TH CENTURY SOCIAL NETWORK

Emilia Peruzzi has been widely recognised, already in her time9 and today, as being an

exceptionally influential woman. Her salon, held in the Florentine house situated in Borgo de’

Greci or in the villa dell’Antella in the southern hills of Florence (Giacalone Monaco 1968), was

attended by literates, politicians, the local aristocracy, and many foreigners10. Her vast

correspondence, of which the received part has been preserved at the National Library in

Florence(BNCF) (Fontana Semeraro, Gennarelli Pirolo 1980; Fontana Semeraro, Gennarelli Pirolo

1984), testifies of the respect she enjoyed. Since she had no outstanding qualities or capacities,

being neither a literate, a poet, a scientist nor an exceptionally beautiful, fashionable or witty

woman11, it might be asked how and why she became the pivotal point of a varied and widespread

network of illustrious, intelligent and powerful people. The answer to this question lies in modern

social media culture. Emilia Peruzzi’s outstanding ability lied in her incessant conversation and

widespread and continuously flowing correspondence. She was even capable of writing while

engaging in multiple conversations (Pareto 1968a, p.111). This made her an early example of

influencer in the cultural and political spheres.

Emilia Peruzzi used her salon and her correspondence in a way that is easily comparable with

today’s participation to social media platforms. Emilia considered conversation to be her preferred

engagement and the main tool to obtain knowledge. She did not like to read. In 1854, quoting

Dante, she confided to her diary: “During my life, that has now reached its half, I have written

much, little I have read” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007 p.1). Apart from some classics, her literary

knowledge derived from others who read the books and commented them to her (Benucci 2007,

pp.XC-CV). In fact, she was more interested in being able to converse about literature than having

a profound understanding of it. Advising her nephew, in later years, she said “Dear child, one must

be utilitarian. From everyone you can learn much more than by studying, if you lead the

conversation on the topic that interests him, or that he has especially studied” (Toscanelli Peruzzi

1922, p.25). Her network, though, was not only the main source of her knowledge, but also a

world of her creation in which she represented herself, expressed her own personality and reigned

supreme.

9

For a complete account of the obituaries and homages dedicated to Emilia Peruzzi in life and after her death in 1900,

see: Benucci 2007, p.XX n.25.

10

For a bibliography on the salon Peruzzi, see: Benucci 2007, pp.XX-XXI n.26.

11

She wrote many times in her diaries on her lack of beauty, always appreciating the fact that this circumstance held

many unwanted attentions at bay.

�Despite all recounts about Emilia’s goodness of heart, by her own admission she had always been

quite a wilful person. In 1845 she wrote in her diary: “I speak frankly and in abundance, I act

ardently. In a bad mood or when I’m excited, I might be pungent, but I immediately repent and if

I’d offended someone, I would not shy from offering my excuses. (…) I like to command and not to

obey. I usually do what I wish, and I don’t like to be opposed. The absence of our mother has made

out of us [she and her sisters] independent women, since our father is almost never at home and

he leaves petty decisions to us, only influencing the big ones. Usually, we know when to ask for

permission and our father tries to accommodate our wishes anyway. I fear I am a little spoiled

since when father denies me, I am not happy at all. Poor me if I should marry an intransigent man,

I would have many a bitter pill to swallow!” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 1922, pp.131-132). Luckily for her,

Ubaldino Peruzzi was not one to oppose her wishes and she could even write recommendation

letters on his behalf, without asking, and get only a mild scolding in return when he was accosted

by someone thanking him for a favour he could not recall having granted.

Social intercourse was for her a form of competition. Exemplary the case of her visit to Mary

Somerville, in May 1856. Mary, according to Emilia’s narrative, was in conversation with Giulia

Ridolfi, a friend and rival of Emilia. In consequence, she engaged in conversation the husband of

Mary, William Somerville who was, up to that moment, sitting nearby, reading a newspaper. “He

lay down the paper, looked at me, stood up and came near me and when I sat up to leave, he

kissed my wrists, not wanting to kiss the glove, and told me that he would never forget the things

that I had told him (…). Mrs Somerville and Giulia smiled astonished by the success that I had

ensured in just a few minutes. And these are my triumphs” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p. 108). Only

a little while before she had admitted that middle aged men were, in fact, her preferred partners

in conversation (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007 p.84). The reason for this choice was, to her, clear:

“Elderly men show a great affection towards me. Among the younger ones only one. Youngsters

are conquered by beauty, coquetry, romantic temperament, melancholia, a mysterious look, and a

tormented soul. Happy women, with serenity in their eyes and a tranquil face; not ugly but like

many others; with no caprices, no mood swings, transparent, fair, sincere, good, inspire esteem

and a general appreciation, have many friends, many admirers but they don’t provoke love, if not

one or two times in life” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p. 108). Emilia, so, abstained from all social

gatherings were beauty, fashionable attire and vain conversations were required. There was also

an undercurrent of moralism in her decision. In May 1856, on her way from Florence to the villa

all’Antella, she penned down: “Tomorrow countryside, solitude, none of what are called

�entertainments, instead peace, quiet, the beauties of nature, freedom and independence: the real

delights of life. My city life has ended for this year, and I salute it with no regrets and no yearning.

How many sighing hearts at the arrival of Spring, by mere distancing, fall prey to oblivion! How

many passing quarrels are extinguished by distance, how many caprices end, how many gallantries

are interrupted! How many fantasies born in candlelight are extinguished by the splendour of a

true spring sunshine!” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, 111). Notorious her refusal to join Ubaldino in

hosting the Emperor of Brasil, one of the grandest events that her husband presided as mayor of

Florence (Ragozzino 2013, pp.563-564). She preferred the limited spaces of the living rooms in

Borgo de’Greci, where the number of guests had to be restricted and she could decide whom to

admit and whom not. Women, unsurprisingly, were scarce. She did not shy to admit: “My taste is

that of a man more than that of a woman. Patriotism, studies, all kind of occupations, with the

exclusion of feminine works, travels, politics, public life are my passions, the things in which I

engage with enthusiasm” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p. 76). Her correspondence also shows an

overproportionate presence of males in respect to females and an alarmingly high level of

bossiness. Younger correspondents like Sidney Sonnino (1847-1922) and Vilfredo Pareto (18481923) had to continuously justify themselves for not having written often enough, long enough,

accommodating enough. Even the Iron Baron, Bettino Ricasoli, one of the most respected and

revered figures of Tuscany’s nobility, went not without occasional scolding. The 21st of November

1856, Emilia noted down: “I wrote some time ago to Bettino reprimanding him that he never took

the initiative in writing and only answered back and many other things, sweet and sour. He

answered that I’m a thorny rose. I answered that the roses without thorns are of a species that

doesn’t have much scent, and I don’t want them in my garden, and, in my house, I rule” (Peruzzi

2007, p.198). The complacency of this observation reveals how much Emilia depended on her

network to express her will and cement her sense of worthiness. Her increasing addiction to

conversation and letters resembles today’s dependence on “likes” and other forms of recognition

in social networks. “I received yesterday 8 letters, 8 people had thought about me and had

engaged with me!” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007 p.1) wrote Emilia with delight in 1854. And more: “All

the action in my present life happens through correspondence” (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.33). As

a final confirmation of how much she came to rely on her own peculiar form of social recognition

it is worthwhile quoting a last entry from her diaries: “and I believe that for a traveller the

possibility to speak about her/his travels is one of the main pleasures” (Peruzzi 2007, 18). The

narrative of the events of her life to her network became, so, more important than the event

�itself. Her identity building and the way she constructed her experience into knowledge were so

the result of her interaction with conversation partners and correspondents: a social and

socialising media (Menduni 2013, pp.124-126).

As in social networks today, dominated by influencers, the prevailing form of opinion building and

rule of choice in the network of Emilia was the principle of authority (Guadagno 2013, 326-328).

Vilfredo Pareto, an assiduous guest of the Peruzzis, immediately noted how in the discussions held

in the salon all opinions could be expressed, but the outcome was already decided. Furthermore,

ideas acquired value and were ordered not according to their internal logic and empirical

verifiability, but with regard to the importance, fame and name of the person who upheld them.

The scholar Gaetano Imbert remembered vividly how the scientific approach of Pareto upset the

orderly functioning of the salon. “When the marquis Vilfredo Pareto attended, the conversation

never languished. He told incendiary things, because his economic and social theories were new

and courageous. He was scandalous among those fogies. - But dear Fried, - would the dame say –

these things cannot be published on L’Economista and even less on the Revue des Deux Mondes. No, dear Mrs Emilia! The truth, that is light must enlighten not only us but also the foreigners”

(Giacalone Monaco 1968b, p. XXI)12. The observation of Emilia was not idle. When Pareto penned

down an answer to an article published in the Gazzetta d’Italia that criticised the idea of

proportionality, and asked Carlo Fontanelli to print it on the Florentine newspaper La Nazione,

Emilia, being befriended with the author, denied the wish of Pareto who had to step back (Pareto

1968a, pp.205-207). Pareto relinquished by writing to Emilia: “Fontanelli will not publish the

article unless thou will give him thy permission. I shouldn’t even have to write it down, thou know

that I would never do anything that could displease thou and I would sacrifice not one but ten

articles (…) to prove my gratitude” (Pareto 1968a, p.206). Notwithstanding his profession of

obedience, Pareto came back on the topic of authority multiple times, mostly with vehement

denial13. In a letter to Emilia written in Vienna the 5th of February 1873, in complete opposition to

12

An example of how Pareto confronted adversaries in animated conversations is given in the letter dated 21 March

1876. “Yesterday evening great discussion with Padeletti on liberal theories. Padeletti says that the guelfism of

Florence will create embarrassment to the government and that this tendency should be repressed. Fridino [Pareto]

fights as a lion and says that if you want freedom for yourself, you must grant it to the others also. Philipson agrees

with the Germanic ideas of Padeletti and Frid [Pareto] in such a nest of vipers doesn’t back down and shouts as both

his adversaries together, denies that he has a partiality for the Scolopi, but praises the Florentine municipality for

subsidising private schools. This heretical notion that the state should not monopolise education flabbergasted

Padeletti and Philipson. Frid [Pareto] is accused of being a clericalist but he shouts that he is honoured by this

definition if it is synonymous of liberal “(Pareto 1968a, p.579).

13

See the letter dated 10th February 1873 (Pareto 1968a, pp.164-168); the letter dated 12 march 1874 (Pareto 1968a,

pp.325-326).

�the principle governing the salon, Pareto declared: “I believe ideas to be everything, the man that

upholds them nothing and often the ideas that prevailed [in the history of science] were

supported by mediocre minds and opposed by luminous intelligences. So that if on some occasion

my tone is too sharp, this is a consequence of my faith in my ideas and not in myself (Pareto

1968a, p.152). Of the two, the principle of authority and the principle of scientificity, Pareto,

despite all scolding by Emilia, would always follow the second.

The principle of authority gave way to sentimental judgements. In the words of Pareto:

“Judgments based on sentiments have always been wrong and if it happens that one should be

right, I wouldn’t know how bad became good and false became right. The sentimental judgment is

always rush, sudden, absolute and is never to be changed, even, you admit it yourself, when the

victorious reason proves it false and unfair” (Pareto 1968a, p.47). Nonetheless, the authority of

Emilia made sentimental judgements the rule in her network: “Perhaps, more than reason,

sentiments divide us and on this terrain I cannot but lose. Thou feel so exquisitely and delicately

that everyone is on thy side, and I stand alone in battle against all my adversaries, only excused by

thy uncommon benevolence” (Pareto 1968a, p.53). The self-representation of Pareto as a solitary

hero armoured in reason and logic, against the rest of Peruzzi’s guests and friends14, underlines

how Emilia’s social network was made out of a majority of common minded followers. The

principle of authority worked, so, as a self-reinforcing mechanism: “What leads astray is that the

esteem and the benevolence of the public are easily possessed by whom does not depart from the

ideas of the majority” (Pareto 1968a, p.60). Pareto, again, perfectly understood and denounced

the fallacy of this rule of choice. He wrote: “The justice and goodness of a doctrine depend on

causes that are external to the doctrine itself, never on the major or minor number of its

followers” (Pareto 1968a, p.58). More: “To take as a rule to follow the opinion that counts the

highest number of followers can lead us to err with the same easiness of a rush judgement, since it

has been observed, rightly in my opinion, that every error has had a time and place in which it was

followed by a majority”. There was only one exception, for Pareto, to the distorted functioning of

networks operating under the principle of authority: networks of science. “I cannot leave it unsaid

that there is one case in which we must judge according to the mind of others: when we are

Pareto’s heroic vision of innovation followed his reading of John Stuart Mill. “I become more and more convinced of

the assertion of John Stuart Mill that all greatness of humanity has been the result of eccentric men that opposed the

ideas commonly held. Examples are infinite and quoting all of them would mean writing the history of the progress of

humankind. Today, luckily, science does not follow authority anymore and authority is only the realm of political and

social questions” (Pareto 1968a, p.73). See also the Darwinian metaphor in the letter of the 2 June 1875 (Pareto

1968a, pp.513-514).

14

�ignorant of a science. Then, we accept the theorems that are reputed true by all the scientist that

practice it” (Pareto 1968a, p.59). Networks were not bad in themselves, but only if they were

governed by the principle of authority, an authority cemented by the numerosity of followers, and

diffused by sentimental judgements. A network, instead, built around a scientific community could

be helpful and positively inform the worldview of the general public.

PATRONAGE AND ÉLITE FORMATION

An influencer, today, is someone who, by the authority given by the number of followers, can

affect the consumption patterns and opinion of a significant number of people. Emilia Peruzzi,

despite managing a network that functioned, as seen, along the same lines as modern social

media, surely did not use her power in the realm of consumerism. Both her and Ubaldino were

rather modest people. They lived sparingly, ate with restraint, and enjoyed long walks.

Nonetheless, Emilia exercised her influence over her followers in no minor measure. To

understand how, the time of Emilia as an influencer should be subdivided in two periods. The first

comprises the brief period in which Florence was capital of the Kingdom of Italy, from 1865 to

1871 (Poettinger, Roggi 2017) The salon Peruzzi, both in Florence and Antella, was then at the

centre of the Italian political life. Emilia thrived in it. Her knowledge of politics made her an

interesting conversation partner and confidante for many politicians15. Thanks to her international

network of correspondents, built up in the many travels and diplomatic missions she shared with

her husband, Emilia was also a reliable source of information on international political events and

moods. All the while the connections of Ubaldino in the Tuscan elite and in the emerging national

financial and industrial ventures, made the couple a reference point for a Tuscany-wide network

of political affiliations. In newly unified Italy, politics was practiced by managing a restricted

electorate made out of notables, through concessions, favours and recommendations. Emilia was

a perfect aid for her husband also in this context. Only a passing glance at the later

correspondence between Emilia and Carlo Fontanelli (1843-1890), one of her and her husband’s

protégés, reveals a continuous flow of requests: a recommendation for a chair in history at the

Naval Institute in Livorno (BNCF Fondo Peruzzi 70, 2, 15); a recommendation for the son of an

employee of the Circolo Filologico to be admitted to Art School, possibly without paying the

15

Examplary of this is the political testament of Luigi Guglielmo Cambray-Digny that he wrote in a letter to Emilia

Peruzzi in May 1876 (Fontana Semeraro, Gennarelli Pirolo 1980, pp.201-202).

�necessary fee, given the poor condition of the family (BNCF Fondo Peruzzi 70, 2, 21) a

recommendation for a chair in Italian, History and Geography at a high school in Prato (Fontanelli

2012, p.251); a recommendation in favour of Francesco Genala (1843-1893) for a chair in

commercial law at the Social Sciences School (Fontanelli 2012, p.255; Fontanelli 2012, p.256); a

recommendation for Tullio Martello for a chair in political economy at the University of Bologna

(Fontanelli 2012, p.262) and so on. The correspondence of other protégés, like Emilio Broglio

(1814-1892), this time with Ubaldino Peruzzi as with Emilia, also shows the same pattern and

contents16.

When Rome became capital of Italy, in fact, the political life and liveliness moved there too,

leaving Florence in disastrous financial conditions and a much quieter place. The social activity of

Emilia, then, transferred from her salon, as seen, more onto her correspondence and the focus of

her attention switched from middle-aged followers to younger protégés. There is no doubt that,

also in this phase, political influence remained the aim of her social activity, at least up to the

fateful 1876 when Ubaldino Peruzzi became instrumental in the fall of the right-wing party and

lost much of his political weight, but her attention inexorably shifted toward a younger

generation. The absence of her diaries for this delicate period of passage and the fact that only

few of her letters have been preserved do not help in understanding the reasons for this

undeniable change. An easy explanation lies in the childlessness of the marriage of Emilia Peruzzi.

Although in many passages of her writings she denied feeling in any way diminished by her want

of motherhood, her intercourse with the youngsters of her family and of her salon shows many

maternal traits, at least in her narrative. As seen, Emilia represented herself as a woman of

mediocre beauty and great virtue, attracting the affection of many middle-aged men but not the

unwanted passion of younger ones. As such she distanced herself from the likes of Marie Laetitia

Bonaparte Wyse, spouse of a rising star of Italian politics, Urbano Rattazzi, who exercised her

influence in Florence with a salon where magnificent toilets, mundane conversations and

libertinism ruled. The rivalry between the two grand dames became legendary (Imbert, 1949) and

no viciousness was spared (Bonaparte Wyse Rattazzi, 1867). The virtuous public image of Emilia

could only be reinforced, given the accusation that the rival threw at her. There surely was also

some genuine moralism behind her attitude toward her protégés, despite a measure of

satisfaction in having to scold some of them for their attempts at passionate declarations of love.

16

The BNFC, Fondo Ubaldino Peruzzi, registers many brief letters from Broglio to Ubaldino and Emilia Peruzzi. Mostly,

Broglio asks for favours and recommendations as in use at the time (Faucci and Bianchi 2005, pp.242-247).

�This last was the case of her first protégé: Eduardo de Carbajal (1831-1895), an Uruguayan painter

who came to Italy to complete his education (Benucci 2007, p.LXXIV). He stayed in Florence

between the end of 1853 and the beginning of 1855 when he relocated to Rome17. Starting in

1855 up to 1864 he wrote 15 letters to Emilia (BNCF, Fondo Peruzzi, 38, 10). Most of the flattery

he bestowed on his patroness was quickly dismissed as an expression of his South American

passionate character (Toscanelli Peruzzi 2007, p.33). Nonetheless, Emilia wrote down with

assiduousness in her diary her dealings with him. The case of Carbajal is worth quoting because it

shows some of the traits that would become typical of Emilia’s style of patronage. While usually

patronesses would encourage young intellectuals and politicians and offer them much needed

connections and recommendations, Emilia also delivered, mostly unwanted, advice on their moral

character and how to meliorate it. About Carbajal, she penned down in her diary, also quoting one

of her letters to him: “I advise him on readings on art and painters, some poetry and ‘Le mie

prigioni’ by Silvio Pellico: ‘I consider it an excellent book for everyone to read but perfect for you.

You would read about the importance of faith for a man who was unjustly martyrised for so many

years. You would have sworn, cursed and consumed yourself. Pellico, in his isolation, found God

and submitted to His wishes, believing in His goodwill’” (Peruzzi 2007, p.17). This duplicity in

scolding young ardent admirers, the literate Edmondo de Amicis would be one such a case, while

boasting with others of their flattering speeches would persist in time, so much so that Pareto

would candidly feel the necessity to explain to Emilia that such compliments were a social

convention in European salons and no real admiration or sentiment lay behind them18.

The most interesting and fruitful patronage would develop in the salon during the 1870s, when

the hustle and bustle of the Capital had passed, and visitors rarefied. The fact that much of it

would be bestowed on youths preparing to enter the political arena or one of the sprouting

economic ventures in new sectors as railways, testifies for the influence of Ubaldino in selecting

them and introducing them in the salon. Ubaldino, in fact, was not extraneous to Emilia’s network.

17

In Rome he would marry Luisa Gramgee, the daughter of an English family living in Florence. In 1858 he would then

return to Monteviedo were he became the most important national painter in the neoclassical academic style. How

much Emilia might have been instrumental in arranging his marriage is not known.

18

Emilia had written to Pareto about the flattering that a young Frenchmen had bestowed on her. Pareto answered:

“These are the usual compliments that you use with dames, I believe that you are too superior in respect to other

women to fall into them. I met a woman, that you know also, Elisa Vita, that confronted with much spirit the poor

devils who tried the usual compliments that educated men believe they have to bestow on women, on her. They were

mortified because Elisa was much too intelligent to believe true words that are vain. I have the fault to love sincerity

and I believe the words that I say. I think it stupid to make compliments that everyone makes and as such loose every

significance. I cannot admire, then, the words of your French friend” (Pareto 1968a, p.173).

�Whenever possible he enjoyed the social life orchestrated by his wife. Ubaldino was also very

thoughtful of her, and it might well be possible that he chose these young people having in mind

to assuage the maternal instincts of Emilia. Nonetheless this newest generation of protégés

reflected in no minor measure his own interests: politics, engineering, and the modernisation of

the Tuscan economy19. As in the case of the economic ideas of Emilia, mostly derived from her

husband, also the economists – lato sensu – who started to attend her circle came so to know her

through initiatives of Ubaldino.

The question that firstly coalesced this cohort of young protégés was that of political

representation (Nieri 1980, Busino 1989 pp.33-62). Carlo Fontanelli, as first, had published, in

1864 a booklet dedicated to this issue for lower grade students (Fontanelli 1864). This, probably,

what caught the attention of the Tuscan moderates, Bettino Ricasoli first and then Ubaldino

Peruzzi. The simple text, explaining to the working class the best possible form of government,

already addressed the main problem of the voting system that had emerged after the Unification

of Italy: the tyranny of the majority and the oppression of minorities. In the words of Fontanelli:

“to avoid that one portion of society be oppressed by another, the government should represent

all interests, all parts of society, not just one” (Fontanelli 1864, p.24). While everyone had the right

to be represented, though, few had a right to represent. Only an élite possessed the morality and

the knowledge necessary to govern with justice (Ibid. p.25, p.52). “The democratic element does

not enter into the government through the entirety of the population (…), but with the election,

i.e. the choice of the most capable made by the population itself. The election is so an essential

part of the representative government” (Ibid. p.78). The booklet written by Fontanelli already

contained two major points of Italian and Tuscan moderates’ thinking on the best representative

system: the necessity firstly to give space to the interests of minorities and secondly to secure the

emergence of personalities that distinguished themselves for their moral and intellectual

capacities. These issues would be underlined also by Emilio Broglio who dedicated his work on

parliamentary forms, published in 1865, to Ubaldino Peruzzi, recognising already at that date his

leading role, as a reformer of the faulty voting system. The jurist Guido Padelletti (1843-1878),

close friend of Fontanelli and later part of the wider circle around the salon Peruzzi20, instead,

published in 1867 a complex historical essay on the theory of political elections (Padelletti 1870)

19

There were others, like the poet Renato Fucini (1843-1921), the literate Edmondo de Amicis (1846-1908) of the

same age group who actively participated to Emilia’s network. Given their occupation they are not included in this

study. Both correspondences have been partially or totally published (Dota 2015, Lazzeri 2006, Vannucci 1973).

20

The archive at the BNCF counts 34 letters from Padelletti to Emilia, written in the timespan 1874-1892.

�that won a prize of the Neapolitan Accademia di scienze morali e politiche and would be published

in 1870. Along the same lines as Fontanelli, Padelletti had a providential idea of history and

wanted the government to follow rules of universal and divine justice (Padelletti 1870, p.7).

Interestingly, after condemning the divorce between political science and religion, Padelletti also

argued in favour of taking into consideration the principles of political economy, particularly the

distribution of income, when deciding the best possible form of government (Ibid. p. 9). This due

to the fact that the right to vote could not be granted to everyone, but exclusively according to the

ability to read and write21 and having reached a certain age, but also in consideration of a grade of

intelligence that could be inferred by applying three criteria: the exercise of a profession, being

employed in public service and possessing a determined level of income. A further criterion of

exclusion, insurmountable for Padelletti, was gender (Padelletti 1870, pp.230-238). Contrary to

the opinion of the otherwise revered John Stuart Mill, women could never be made into electors

or, God forbid!, elected. Amid so much conservatism, Padelletti still found some criticism toward

the Italian representative system that, since Unification, allocated the parliamentary seats to the

most voted candidate in every constituency. Such a system, in which the imposed restrictions

allowed just under 2% of the population the right to vote, completely unrepresented the losing

minorities. On the same lines as Fontanelli, Padelletti (1870, pp.246-257) condemned the

consequent tyranny of the majority and advocated the adoption of the quota system, proposed by

Thomas Hare (Hare 1857, 1873) and divulged by John Stuart Mill (Urdánoz 2019). This system

rather than being proportional, was personal, in the sense that voters had the right to choose

whatever candidate they preferred nationwide and, granted that this candidate coalesced enough

votes to reach the quota level (n. of voters/n. of parliamentary seats), he would be elected. Once

reached the quota level, ulterior votes for the same candidate would be switched to a second

preference, then a third and so on, so that every vote would, in the end, be represented. What

Hare and Mill wanted to achieve with such a system was to take away power from the party

system, usually polarised, while giving the possibility to worthy personalities outside of the parties

to be elected. The élites would so enter Parliament, without the need of constraining party

affiliations (Mill 1963, p.456). “With the actual system – underlined Padelletti – the majority is

obliged to accept the candidates of the party and to obey to its vote indications, in order not to

lose votes. This, according to Stuart Mill is not democracy but a figment of democracy. With the

21

At the time in Tuscany 74% of the population was illiterate. In 1911 still 37% of Tuscans could neither read nor write

(De Mauro 1963, p.95).

�Hare system, instead, not only would minorities be represented, but each deputy would be

elected by unanimous voters, who would then be truly represented. Each voter would so give his

vote to a candidate confiding in his character and intelligence, agreeing with his opinions and the

elections would thus hold a much greater value. (…) It is easy to see how this voting method would

elevate the quality level of the Chamber of Deputies. Minorities would have every incentive to

elect illustrious men who would worthily represent the ideas of their party and would have the

possibility to exercise a greater influence, by sometimes convincing the majority, in parliamentary

discussions, of their theses, thanks to their great capabilities” (Padelletti 1870, 253).

While Thomas Hare and John Stuart Mill theorised this new personal system of voting, that would,

as seen, immediately be commented and divulged in Italy22, in Geneva, in August 1864, the

disastrous turmoil following an election that had sanctioned the victory of one candidate for just a

few votes, convinced the philosopher Ernest Naville (1816-1909) to start a campaign in favour of

introducing proportionality, via a version of the Hare system, into the local voting system (Naville

1864). In 1865 he so set up a Reform league, on the example of the Cobdenian Anti-Corn Law

League, with the aim of diffusing the idea of proportionality worldwide (Busino 1989, pp.41-42)23.

His activity is of interest because his father had been a close correspondent of Tuscan intellectuals

of the calibre of Raffaele Lambruschini and had visited Tuscany, becoming acquainted with the

local notables. Ernest himself, who had been in Florence between 1839 and 1840, became a

correspondent of Lambruschini and through him of Bettino Ricasoli. In 1869, in Geneva, he met

Francesco Genala (Busino 1989, pp.43), who was travelling all over the Continent in a sort of

reversed Grand Tour. After discussing at length with Naville, Genala published a book in which he

related the theories of Hare and Mill, but also presented the Genevan association to the Italian

public (Genala, 1871). At the same time, Naville rekindled the acquaintance with the Peruzzis, as

proved by the 65 letters written to Emilia between 1871 and 1897 and preserved at the BNCF. His

main advocate in Italy, though, at this point, was the jurist Attilio Brunialti (1849-1920), another

22

The first to introduce the Hare system had been Giuseppe Saredo, professor of Constitutional Law at the University

of Parma, in his course of 1861-62. After him Padelletti, as seen, dedicated a chapter of his book to Hare. Then

Francesco Genala and Sidney Sonnino would both propose versions of Hare’s voting system in their works. On this,

see: Genala 1871, p.47; Maglie 2014, pp. 144-146.

23

The network of the league included: John Stuart Mill and Thomas Hare in Great Britain, Victor D’Hondt and Jules de

Smedt in Belgium, Maurice Vernes in France, Francis Fischer in Philadelphia, and Sydney Myers in Chicago.

�young attendant of the salon Peruzzi24. Brunialti, also in 1871, published a work that resumed,

translated, and divulged the activities of the Genevan Reform League (Brunialti 1871).

So much political interest and activity25 coalesced in May 1872 in the first meeting of the

promoting committee for the foundation of an Italian Association for the Study of the Proportional

Representance. Obviously, Ubaldino Peruzzi was among the promoters, along with Brunialti,

Genala, Padelletti, Broglio and the long time friend of the Peruzzis, Ruggero Bonghi26. Among the

others, we find many politicians and jurists of the time, with which Ubaldino had connections:

Terenzio Mamiani, Giuseppe Saredo, Alessandro Spada, Luigi Luzzatti, Angelo Messedaglia,

Pasquale Stanislao Mancini, and Marco Minghetti27. The chart of the association, as signed by the

members of the committee, stated that “to fulfil its ends, the representative system must collect

in the Council of the elected the representants of the ideas, interests and needs of the entire

community - and at the same time must guarantee that these representants should be the

persons better suited, for their knowledge and virtue, to accomplish the task that has been

entrusted onto them (…) Then the representance truthfully portrays the state of things and of

spirits and by putting these elements, so different, to work together and for the common good,

constrains them to discuss with maturity and to converge, at the end, toward a decision that will

surely comply with the will of the true majority and will probably be the best that that people

would on that occasion think of and want” (Piretti 1990, pp.21-23). To achieve this ambitious goal

there was just one voting principle to be applied, that of Thomas Hare.

President of the Association became Terenzio Mamiani. Francesco Genala and Attilio Brunialti

were nominated as secretaries with the task to organise the manifold activities of the Association

and publish its Bulletin. The first public assembly of the Association was held in Florence at the

Accademia dei Georgofili in June 1872 (Busino 1989, pp.45-47), becoming the fateful occasion in

24

The BNCF registers two letters sent by Brunialti to Ubaldino Peruzzi, without a date (Fontana and Gennarelli 1980,

p.212).

25

The question also occupied Emilia’s salon in the villa all’Antella. Emilia wrote to Sonnino in 1872: “A long discussion

on the representation of minorities – some argue that in Italy minorities are far better represented than the majority!

Hillebrand eloquently argues against this thesis, Giorgini makes many subtle observations. Between Hillebrand and

Giorgini a wonderful discussion, witnessed by all others, on old and modern societies, on social problems, on

questions of political economy, on the more elevated questions – the eternal and the mutating things” (Sonnino 1989,

p.292).

26

The BNCF registers 264 letters sent by Bonghi to Emilia between 1859 and 1886 (Fontana and Gennarelli 1980,

p.211)

27

Marco Minghetti was a sporadic guest of the salon Peruzzi.

�which the young speakers and organisers, Sonnino (1970; 1872), Pareto28. and Genala29, came in

touch with Carlo Fontanelli, who also held a speech on the occasion (Fontanelli 1872), and Emilia

Peruzzi. Invited to join in the salon, they all became protégés of the Peruzzis and started a long

lasting correspondence.

The importance of the new voting system for Ubaldino Peruzzi cannot be underestimated. He so

much believed in the new voting system that he tried to introduce it in local institutions and

private companies, according to the indications received from Ernest Naville. First of all, obviously,

not without raising protests from older associates, the personal voting system à la Hare became

the rule in the Circolo Filologico (Maglie 2014, pp.148-150), then in the Società per l’industria del

Ferro of which Ubaldino was president (Busino 1989, p.53). Proportional representation was also

introduced, with the help of Vilfredo Pareto, who was at the time general director of the Società

per l’industria del Ferro, in its workers’ association, the Società operaia di San Giovanni Val d’Arno

(Ibid.). Here the new voting system produced positive effects. Before, of the three categories of

workers employed: metal workers, machinists and porters, the first were numerically superior and

with the majority system acquired all representative positions in the board, causing protests and a

tense working environment. After including representatives of the minority workers into the

board, the situation de-escalated. Thanks to the campaigning of Pareto, the new voting system

was also adopted in Genoa, in the Banca operaia mutua di Sampierdarena, and the Società per la

costruzione di case di Sampierdarena. Lastly, many cooperatives in Central Italy decided to change

their representance into the Hare system (Ibid.). The success was so important that Naville would

boast about the Italian case at the reunions of the Genevan League. Nonetheless every attempt to

introduce proportional reforms into the Italian voting system, according to the proposals made by

Genala and Minghetti in 1879, came to nothing (Maglie 2014, pp.151-153). The only advancement

would be, in 1882, the easing of the requirements for suffrage and the extension of voting rights

to almost 7% of the population.

The reason why the staunch belief of Ubaldino in personal representance is so important in the

context of this paper is that he, with no minor help by Emilia, put in practice the ideas of Mill not

28

A previous knowledge between Ubaldino Peruzzi and the father of Vilfredo Pareto must be excluded, given the

content of the correspondence between Raffaele Pareto and Emilia/Ubaldino Peruzzi. The letters have been published

as an Appendix to Pareto 1968b, pp. 641-676.

29

Ubaldino was well connected with the Tuscan Jewish business community and so knew both Isacco Sonnino, father

of Sidney (Carlucci 1998, p.XIII), and the banker Abramo Philipson, father of Eduardo, who would become his pupil

and another of Emilia’s protégés. On this circle, see: Funaro 2017.

�only campaigning for a reform of the voting system, but also dedicating a lifetime of effort in

nurturing those morally irreprehensible and culturally knowledgeable young men who, when

elected in Parliament, would enrich the quality of politics and benefit the whole country. Having

been selected for their merits, promising qualities and knowledge, these youngsters, all born in

the decade between 1843 and 185330, became assiduously present in the salon and in Emilia’s

correspondence. Carlo Fontanelli sent her 590 letters between 1868 and 189031, Francesco Genala

a staggering 1999 letters between 1872 and 1893, Vilfredo Pareto 1397 letters between 1872 and

1900 (Pareto 1968aa, Pareto 1968ab), Eduardo Philipson 233 letters between 1873 and 1897, and

Sidney Sonnino 165 letters between 1872 and 1878 (Sonnino 1998). As in the building of a

functional élite should be, they also became friends, as Carlo Fontanelli himself testified through a

witty poem written about the salon, dedicated to Emilia:

“Whatever my future and fortune will be

I will never forget your courtesy

or the elegant and appreciated conversations

of which you were the centre, the soul and life;

all the questions we gratefully discussed,

often to the point of exhaustion;

dear Sidney about universal suffrage,

my sweet Genala on proportional representation,

Pareto about a free, emancipated woman,

voting and voted, judge and lawyer” (Carlucci 1998, p.XVII; Fontanelli 2012, pp.250-251)

Although the salon was a merry place, where adults played social games, engaged in singing and

music, recited poems and even acted in childlike manner, there is no doubt that Ubaldino

practiced a very precise operation of élite selection and formation. The fact that the participants,

here analysed, engaged in economic studies must not mislead. They were mostly prepared for a

political career. Francesco Genala would be elected in Parliament as soon as he reached the

30

Carlo Fontanelli (1843-1890), Francesco Genala (1843-1893), Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923), Edoardo Philipson (18531944), Sidney Sonnino (1847-1922).

31

The correspondence of Fontanelli with Emilia has been partially published in Fontanelli (2012) pp.249-266.

�necessary age and would maintain his seat from 1874 al 1893. In this timespan, he would also act

twice as minister for public works. Interestingly, he would always side with the left-wing party, not

with the right, of which Ubaldino Peruzzi was a leader. A proof that, for Ubaldino and Emilia, what

mattered was the quality of the elected, not their political side, nor their party affiliation.

Fontanelli wrote it clearly in a letter to Emilia: “Please insist with Genala that if elected he won’t

refute his seat. He is one of the young people that I’d love to see in Parliament. A sharp mind,

serious studies, straight character, refined language: he possesses all qualities needed to be

excellent deputy. Persuade him. I tried many times but to no avail” (Fontanelli 2012, p.254). As a

side effect, the network managed by Emilia would be influential across all the spectrum of Italian

politics. Sydney Sonnino underwrote the vision of Ubaldino on a proportional reform (Sonnino

1989, p.105), also sharing his dislike for the nefarious influence that parties had on the level of

political discussion. In 1877, he would confess to Emilia: “In Rome I was disgusted by the condition

of the parties, right- and left-wing. What a total absence of civil courage! I almost fear of stepping

at one point into the Chamber as deputy and let myself be overcome by that sickness that takes

away the ability to see the great questions, concentrating the activity and vitality of so many

people on trivialities and unworthy gossip” (Sonnino 1989, p.264). Sonnino would sit in Parliament

from 1880 to 1919, to be made senator in 1920 up to his death in 1922. A right-wing liberal,

Sonnino would become a primary figure of Italian politics and hold over time the position of prime

minister and various other ministerial posts. His position, though, would never be that of party

servility32. Lastly, Vilfredo Pareto, before his call to the chair in economics at Lausanne, tried to be

elected in Parliament, with the help of the Peruzzis, without success (Mornati 2018, pp.162-171;

Giacalone Monaco 1965), but was nonetheless politically active as a municipal Councillor in San

Giovanni Valdarno for several years (Mornati 2018, pp.171-173).

As early as in 1868, Carlo Fontanelli was the first to become part of Emilia’s circle, through the

recommendation of Bettino Ricasoli (Pallini 2012, p.7). He might seem an exception among

Peruzzi’s protégés, and he was, in regard to pursuing a political career. In reality, he was an

essential part of the Peruzzis’ network, more important for its functioning than any of the others.

While the young politicians to be would bring their excellence into the national Parliament and

local administrations, along with the ideals and interests of the network, Fontanelli had the vital

In 1874, he wrote to Emilia: “If this is the credo of the Right; if to belong I must abiure every belief I have on

economics, if I must abstain from every individual judgement, even on secondary questions (…) then I really don’t

know into wich party I shouls classify myself” (Sonnino 1989, p.189).

32

�scope to divulge the activities of the network and of its adherents far and wide, through

newspaper articles, popular booklets, manuals and courses dedicated to as many different

audiences as possible (Pallini 2012, pp. 9-10), from popular to female schools, from primary

instruction to the renown Social Sciences School of superior studies (Pallini 2012, pp. 15-17).

Fontanelli, in essence, extended the number of followers outside the network of Emilia. He

created the voters that the young politicians needed to be elected and to enact their policies.

Fontanelli embraced this mission and dedicated his life to it (Pallini 2012, p.10). To this end,

Ubaldino put him in a neuralgic position in all his institutional initiatives. Fontanelli was so among

the first associates of the Società Adamo Smith (Poettinger 2022), editor of the journal

L’Economista (Poettinger 2013), vice-secretary of the Circolo Filologico33 and lifelong professor of

economics at the Social Sciences School34.

Fontanelli also represents the shift of the attention of Tuscan liberals and specifically of Ubaldino

Peruzzi from politics and the problem of representation toward economic policies. Liberal

economics, ideally represented by the thought of Adam Smith and practically by free-trade

movements following the Cobdenian example, had always been an essential part of the Italian

Risorgimento. The Piedmontese Count Cavour, the mastermind of Italian Unification, had been a

passionate liberalist and Tuscans had a tradition of liberalism that dated back, as seen, to the

Lorenian reforms of the 18th century (Poettinger 2022, pp.150-153). From its birth, in 1861, Italy

had so embraced liberalism as its official economic ideology. The Franco-Prussian war, though,

although it regaled Italy with its coveted capital Rome, also popularised the economic practice of

the victorious German Empire: protectionist measures and social reforms. In the 1870s one of the

main political battlefields would so become economic policy. Liberalism got under siege. This the

reason for the frantic activity of the Peruzzis’ network in trying to spread liberalism in the new

parliamentary élite, among the electorate and even in the wider population. A proof of this change

in attitude of Ubaldino, in respect to economics, comes from his relationship with the Società

italiana di economia politica35. Founded in 1868, thanks to the driving force of Francesco Ferrara,

the Society shared many promoters with the Italian Association for the Study of the Proportional

33

On this initiative, see: Carlucci 1998, p.XIII.

The pervasive diffusion activity done by Fontanelli on newspapers and journals is difficult to reconstruct, given that

many articles were published anonymously. Here just one example taken from one off his letters concerning the

opening of the Social Sciences School: “In regard to the School [of Social Sciences] I have written an article for La

Nazione, one for L’Economista and I will write another. If the others don’t do the same is not my fault” (Carlo

Fontanelli a Emilia Peruzzi s.d. BNCF Fondo Peruzzi 70, 2, 18).

35

On this society, created by Francesco Ferrara on the example of the Parisian Société d’économie politique see:

Poettinger 2022, 55.

34

�Representance: Luigi Luzzatti, Angelo Messedaglia and Marco Minghetti (Protonotari 1868, p.630).

Ubaldino, though, refuted a direct involvement and simply delegated one of his trusted men,

Emilio Broglio, to represent him36. The Society rarefied its operations between 1871 and 1872, due

to the increased divergence in the political stance of Italian economists. Liberalists coalesced

around Francesco Ferrara and Ubaldino Peruzzi, who promoted, in 1874, this time with renewed

enthusiasm, the foundation of the Society Adam Smith. The Society reflected the intent of Peruzzi