Yavne and Its Secrets

קובץ מחקרים

Collected Papers

, ליאת נדב־זיו, אלי הדד:עורכים

, פבלו בצר, דניאל וורגה,יוחנן (ג'ון) זליגמן

אורן טל ויותם טפר,עמית שדמן

Editors: Elie Haddad, Liat Nadav-Ziv,

קובץ מחקרים:יבנה וצפונותיה

יבנה וצפונותיה

Jon Seligman, Daniel Varga, Pablo Betzer

Amit Shadman, Oren Tal and Yotam Tepper

�1*

Yavne and Its Secrets

Collected Papers

Editors:

Elie Haddad

Liat Nadav-Ziv

Jon Seligman

Daniel Varga

Pablo Betzer

Amit Shadman

Oren Tal

Yotam Tepper

Jerusalem 2022

�2*

Editors

Elie Haddad

Liat Nadav-Ziv

Jon Seligman

Daniel Varga

Pablo Betzer

Amit Shadman

Oren Tal

Yotam Tepper

Editorial Coordinator

Einat Kashi

Language Editors

Hana Hirschfeld

Galit Samora-Cohen

Anna de Vincenz

Production Editor

Ayelet Hashahar Malka

Typesetting, Layout and Production

Ann Buchnick-Abuhav

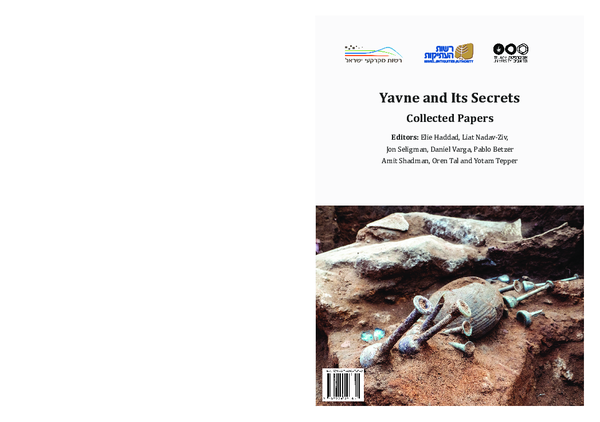

Cover Illustrations

Hebrew: The excavation at the foot of Tel Yavne (photography: Asaf Peretz)

English: Glass bottles and cooking pot from the Roman period (photography: Asaf Peretz)

© 2022, The Israel Antiquities Authority, Tel Aviv University and Israel Land Authority

ISBN 978-965-406-765-2

EISBN 978-965-406-766-9

Printed at Digiprint Zahav Ltd. 2022

�3*

CONTENTS

5*

List of Abbreviations

7

Editorial

13

Present, Future, Past: Israel Antiquities Authorityʼs Excavation Project

at Yavne (East)

Diego Barkan and Amit Shadman

ARCHAEOLOGICAL-HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

19

Ancient Yavne: Preliminary Finds from the Extensive Excavations at the Foot of

Tel Yavne

Liat Nadav-Ziv, Elie Haddad, Jon Seligman, Daniel Varga and Pablo Betzer

9*

The Geomorphology and Sedimentology of the Tel Yavne Environs, Southern

Coastal Plain of Israel, and its Connection to Ancient Human Settlement

Joel Roskin, Oren Ackermann, Yotam Asscher, Jenny Marcus and Nimrod Wieler

25*

Land and Sea: On the Relationships, Similarities, and Differences between

Yavne and Yavne-Yam from the Persian to the Beginning of the Crusader Period

Itamar Taxel

55

The Hasmonaean Battle near Iamnia (Yavne)

Ze’ev Safrai

THE ARCHAOLOGICAL REMAINS

73

A New Site from the Chalcolithic Unearthed in Yavne

Yael Abadi-Reiss

89

The Yavneh Pit: A Repository (Genizah) of a Philistine Temple

Raz Kletter, Wolfgang Zwickel and Irit Ziffer

111

A New Inscribed Sling Bullet from Iamnia (Yavne)

Yulia Ustinova, Pablo Betzer and Daniel Varga

125

Preliminary Insights on the Economy and Industry of Yavne in the Roman

Period: A Zooarchaeological View

Lee Perry-Gal, Pablo Betzer and Daniel Varga

143

Glass Production at Yavne, First Impressions from Area L

Yael Gorin-Rosen, Pablo Betzer, Daniel Varga and Ariel Shatil

161

“May My Coffin Be Perforated to the Earth” (JT, Ketubot 12.3.3): Roman-Period

Cemeteries at Yavne

Eriola Jakoel, Alla Nagorsky, Pablo Betzer and Daniel Varga

�4*

55*

Put Your Shoulder to the Wheel: Bone Tools Made from Animal Shoulder

Blades from Tel Yavne—Uses and Reconstruction

Inbar Ktalav, Ariel Shatil, Natalia Solodenko, Yotam Asscher and Lee Perry-Gal

185

Beachrock Finds from Yavne-East Excavations: Preliminary Results

Amir Bar, Elie Haddad, Yotam Asscher, Chen Elimelech, Aliza van Zuiden, Revital

Bookman and Dov Zviely

WINE AND COMMERCE

205

It’s a “hangover”: The Winepress Complex of Byzantine Yavne

Mor Viezel and Hagit Torge

219

Jar Mass Production for the Yavne Wine Industry: The Relationship between

the Pottery Kilns and the Pottery Dumps

Orit Tsuf

241

Yavne and the Wine Industry of Gaza and Ashqelon

Jon Seligman, Elie Haddad and Liat Nadav-Ziv

265

Eastern Mediterranean Trade Routes in Late Antiquity

Deborah Cvikel

�5*

List of Abbreviations

AAAS

Annales archéologiques arabes syriennes 1966–

AJA

American Journal of Archaeology

BAIAS

Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society (Strata BAIAS from

2009)

BAR Int. S.

British Archaeological Reports (International Series)

BASOR

Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research

DOP

Dumbarton Oaks Papers

HA–ESI

Hadashot Arkheologiyot–Excavations and Surveys in Israel

(from 1999)

IAA Reports Israel Antiquities Authority Reports

IEJ

Israel Exploration Journal

IJNA

International Journal of Nautical Archaeology

INR

Israel Numismatic Research

JAMT

Journal of Archaeological Methos and Theory

JAS

Journal of Archaeological Science

JFA

Journal of Field Archaeology

JGS

Journal of Glass Studies

JIPS

Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society (Mitekufat Haeven)

JMA

Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology

JNES

Journal of Near Eastern Studies

JRA

Journal of Roman Archaeology

JWP

Journal of World Prehistory

LA

Liber Annuus

NEA

Near Eastern Archaeology

NEAEHL 5

E. Stern ed. The New Encyclopedia of Archaeological Excavations in the

Holy Land 5: Supplementary Volume. Jerusalem 2008

NGSBA

The Nelson Glueck School of Biblical Archaeology

OBO.SA

Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis Series Archaeologica

PBSR

Papers of the British School at Rome

PL

J.-P. Migne ed. Patrologiae cursus completus, series latina.

Paris 1844–1880

QDAP

Quarterly of the Department of Antiquities of Palestine

RB

Revue Biblique

RDAC

Report of the Department of Antiquities, Cyprus

SCI

Scripta Classica Israelica

�6*

ZPE

TMO

ZPE

Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik

Travaux de la Maison de l’Orient

Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik

�7*

List of Contributors

Diego Barkan, Israel Antiquities Authority

diego@israntique.org.il

Amit Shadman, Israel Antiquities Authority

shadman@israntique.org.il

Liat Nadav Ziv, Israel Antiquities Authority

liat.ziv26@gmail.com

Elie Haddad, Israel Antiquities Authority

haddad@israntique.org.il

Jon Seligman, Israel Antiquities Authority

jon@israntique.org.il

Daniel Varga, Israel Antiquities Authority

daniel@israntique.org.il

Pablo Betzer, Israel Antiquities Authority

pablo@israntique.org.il

Joel Roskin, Bar Ilan University, Israel Antiquities

Authority

joel.roskin@biu.ac.il

Oren Ackermann, Ariel University

orenack@gmail.com

Yotam Asscher, Israel Antiquities Authority

yotama@israntique.org.il

Jenny Marcus, Ariel University, Israel Antiquities

Authority

jenny@israntique.org.il

Nimrod Wieler, Israel Antiquities Authority

nimrodw@israntique.org.il

Itamar Taxel, Israel Antiquities Authority

itamart@israntique.org.il

Ze`ev Safrai, Bar Ilan University

zeev.safrai@gmail.com

Yael Abadi-Reiss, Israel Antiquities Authority

yaelab@israntique.org.il

Raz Kletter, Helsinki University

kletterr@gmail.com

Wolfgang Zwickel, Johannes Gutenberg-University,

Mainz

zwickel@uni-mainz.de

Irit Ziffer, Eretz Israel Museum, Tel Aviv

irit.ziffer@gmail.com

Yulia Ustinova, Ben-Gurion University

yulia@bgu.ac.il

Lee Perry-Gal, University of Haifa, Israel Antiquities leepg@israntique.org.il

Authority

Yael Gorin-Rosen, Israel Antiquities Authority

gorin@israntique.org.il

Ariel Shatil, Israel Antiquities Authority

arielsh@israntique.org.il

Eriola Jakoel, Israel Antiquities Authority

ejakoel@walla.co.il

Alla Nagorsky, Israel Antiquities Authority

alla@israntique.org.il

Inbar Ktalav, University of Haifa, Israel Antiquities

Authority

ananlotus@gmail.com

Natalia Solodenko, Hebrew University

natalya.solodenko-vernovsky@

mail.huji.ac.il

Amir Bar, University of Haifa, Israel Antiquities

Authority

hazirbar@gmail.com

Chen Elimelech, Israel Antiquities Authority

chene@israntique.org.il

�8*

Aliza van Zuiden, Israel Antiquities Authority

alizavanz@gmail.com

Revital Bookman, University of Haifa

rbookman@univ.haifa.ac.il

Dov Zviely, Ruppin Academic Center

dovz@ruppin.ac.il

Mor Viezel, Israel Antiquities Authority

morv@israntique.org.il

Hagit Torge, Israel Antiquities Authority

torge@israntique.org.il

Orit Tsuf, Independent Scholar

oritsuf@netvision.net.il

Deborah Cvikel, University of Haifa

dcvikel@research.haifa.ac.il

Editors

Elie Haddad, Israel Antiquities Authority

haddad@israntique.org.il

Liat Nadav Ziv, Israel Antiquities Authority

liat.ziv26@gmail.com

Jon Seligman, Israel Antiquities Authority

jon@israntique.org.il

Daniel Varga, Israel Antiquities Authority

daniel@israntique.org.il

Pablo Betzer, Israel Antiquities Authority

pablo@israntique.org.il

Amit Shadman, Israel Antiquities Authority

shadman@israntique.org.il

Oren Tal, Tel-Aviv University

orental@tauex.tau.ac.il

Yotam Tepper, Israel Antiquities Authority

yotam@israntique.org.il

�The Geomorphology and Sedimentology of the Tel

Yavne Environs, Southern Coastal Plain of Israel, and its

Connection to Ancient Human Settlement

Joel Roskin, Oren Ackermann, Yotam Asscher,

Jenny Marcus and Nimrod Wieler

Introduction

This paper aims to comprise a basic geomorphic framework for archaeological and

geoarchaeological analyses of the mega site excavation of Tel Yavne. We present the

basic geomorphic, sedimentological, hydrological, and geological features of the tel

and its environs based on academic literature, reports, GIS-based geospatial analysis,

and preliminary surveys at the excavation and its surroundings. We also provide

initial mineralogical ratios from Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), a

method to characterize materials based on their molecular composition and used in

archaeology to identify ancient materials (Weiner 2010).

Geographic Setting

Tel Yavne is located in Israel’s inner and southern coastal plain (Fig. 1) in a

Mediterranean climate of 480 mm/yr annual average precipitation (Negev, Simin

and Keller 1970). South of Yavne begins a north-south climate gradient with the

Negev desert. Only fifty km south of Yavne, south of the Shiqma basin, begins the

Negev desert fringe, where precipitation is 200–300 mm/yr. The gradient is sensitive

to climate change.

The general geological components of the environs of Tel Yavne contain discrete

aeolianite (kurkar in Hebrew) ridges that run parallel to the past and modern

coastline (Figs. 1b, 2), red sand and loam, and Holocene alluvium. The surface is

characterized by red sandy soils (also known locally as ḥamra) and alluvial brown

and hydromorphic soils (Vertisols/Grumusols) (Dan et al. 1972; 1976; Dan, Fine and

Lavee 2007).

The site is located within the Mediterranean vegetation belt. However, the natural

vegetation is absent. The current vegetation is dominated by volunteer crops and

ruderal species of annual herbaceous plants. These species characterize neglected

�10*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

and disturbed lands and agricultural crops. These species dominate since the area

has undergone intensive anthropogenic and agricultural activity for millennia. These

anthropogenic processes affected the late Holocene surficial processes that, in turn,

changed the ancient landscape, yielding today’s anthropogenic one.

Aeolianite Ridges Dictate Landscape and Settlement patterns

North-south trending aeolianite ridges comprise the morphological and topographical

backbone of the coastal plain of Israel (Fig. 1a, b). The southern coastal plain has the

most significant amount of discrete inland aeolianite ridges. Aeolianites are ancient

coast-parallel accumulative dunes that, following sand deposition, became a rock

due to precipitation of calcium carbonate. The ridges and their interdune valleys

or troughs are usually many hundreds of meters to several kilometers wide. The

aeolianite cliffs along the Sharon and Carmel coast near the shoreline have been

dated by optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) to the late Pleistocene. However,

the inland aeolianite ridges have been sporadically dated to the middle to early

Pleistocene (Malinsky-Buller et al. 2016; Harel et al. 2017; Zaidner et al. 2018). The

aeolianite ridge of Yavne has not been dated.

The fertile Grumusol clay-rich soils and sediments in the interdune valleys

between the aeolianite ridges have been an important factor in ancient settlement.

The nineteenth-century Arab villages that appear on the Palestine Exploration

Fund (PEF) map (1871–1877) were commonly situated upon remains of ancient

settlements (Schaffer and Levin 2016). These villages usually were located on the

slopes of the aeolianite ridges, probably to maximize the agricultural potential of the

adjacent interdune valleys.

Tel Yavne is bordered by valleys and plains that are relatively wide for Israel’s

southern and central coast (Fig. 1b). The Soreq-Gamliel segment of the Naḥal Soreq

valley to the east is one of the widest and largest valleys. The aeolianite ridge 5 km

southeast of the Soreq-Gamliel plain, where the ancient village of El-Maghar was

situated, at 94 m above sea level, is the highest in the region (Gophna, Paz and Taxel

2010). This ridge may have provided regional security and control on the valuable

agricultural expanses of the Soreq-Gamliel plain between Yavne and El-Maghar.

Fig. 1. Tel Yavne in the southern coastal plain: (a) Orthophoto; (b) Elevation map

►

demonstrating the wide valley of the northern flowing Soreq with lines of two topographic

cross-sections (see Fig. 2). Grey dashed arrows delineate five aeolianite ridges of different

elevations and widths (orthophoto and map: N. Wieler).

�The Geomorphology and Sedimentology of the Tel Yavneh Environs

(A)

|

11*

(B)

Yavne

Plain

SoreqGamliel

valley

W

Tel

Yavne

Tel

Yavne

Soreq stream

Elevation

(m.a.s.l)

110

20

a

(B)

N

Yavne

Plain

Tel

Yavne

Tel

Yavne

Elevation

(m.a.s.l)

110

b

20

Al Ma

gha

r

am

ridg

e

SoreqGamliel

valley

W

S

Soreq stream

E

S

Soreq stream

�12*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

Elevation (meters)

B 100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

South

North

Tel Yavne

Soreq-Gamliel valley

Soreq stream

Tel Yavne

aeolianite ridge

0

2000

Topographic

saddle

4000

Tel Yavne

aeolianite ridge

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

Distance (meters)

Fig. 2. Cross-sections of the Yavne environs (see location in Fig. 1). Top: Crosssection perpendicular to the coastline (ca. west–east), exemplifying the SoreqGamliel valley and the Maghar aeolianite ridge to its east. Bottom: Cross-section

parallel (ca. north–south) to the coastline along the Tel Yavne aeolianite ridge.

Note the dashed line connecting similar ridge elevations on both sides of

the Soreq-Gamliel valley within an ancient valley of the palaeo-Soreq stream

(drafting: N. Wieler).

Fluvial Geomorphology of Naḥal Soreq

The dynamics of Naḥal Soreq appear to have been the major geomorphic force

dictating a wide range of impacts on the anthropogenic activities of the various

populations of Yavne. The Soreq basin, also known as Wadi Qalunia/Sarar/Beit

Ḥanina in the Judean Hills (Highlands), drains westward into the Mediterranean Sea

(Figs. 1, 4a, b). The currently ephemeral and highly meandering basin, extending over

c. 760 km2, is the most extensive, deepest, and oldest (see below) drainage system

in the Judea and Samaria Hills. The Soreq drainage includes three main segments:

the Judean Hills segment (800–250 m a.s.l.), the Judean Foothills (400–200 m a.s.l.),

and the coastal plain (250–0 m a.s.l.) segment where Tel Yavne is located. Here the

average wadi gradient is very subtle, 6.3m/km (Nir 1964). The Soreq sediment is

fine-grained in the Yavne environs, and clasts are rare.

�The Geomorphology and Sedimentology of the Tel Yavneh Environs

|

13*

Fluvial Regime of Naḥal Soreq

Naḥal Soreq has been found to have an extensive range of flow discharges. The mean

annual discharge of the Soreq based on data from the 1950s–60s was reported as

2.7–3 M m3/s (Nir 1964). Discharge measured at the outlet of the Soreq from the

Judean Hills into the Judean Shephela (Lowlands) is only about 2% of the rainfall

on the catchment. This stems from high infiltration attributed to the cracked and

karstic-rich geology of the highland slopes. Thus, local runoff partly influences the

flow in the coastal lowlands. Today the Soreq flow is channeled in the Yavne environs

(Fig. 3), making current data less reliable for hydrological reconstruction.

Today, the flows of the Soreq transport relatively small amounts (by a magnitude)

of suspended sediment estimated at 47 m3/km/yr, compared to other Israeli

ephemeral wadis in Mediterranean environments. This anomaly may be due to the

highly vegetated and terraced character of the Jerusalem Hills basin in a preserved

environment in relation to the environmentally neglected Judea and Samaria Hills

under split Palestinian and Israeli administrations. Current suspended (fine-grained)

sediment is only 1% of the total fluvial load (Avron 1973). The Soreq neither incises

nor aggrades in the hills and deposits fluvial sediment in its channel and floodplains.

Thus, most of the suspended sediment of the Soreq is transferred to the coastal

lowlands, where it is either deposited or flushed into the Mediterranean Sea.

Quaternary Geology of the Yavne Environs

Tel Yavne is spread over the crest, slopes, and colluvial slope of an aeolianite ridge

adjacent to the fringe of the Naḥal Soreq valley. The tel rises to 55 m a.s.l. near the

northern tip of the aeolianite ridge (Yavne ridge) that trends north–south (Figs. 2–4).

Tel Yavne is not a classic tel mound, and its position was probably a result of ancient

geomorphic-based logic – to settle the best controlling grounds in the region adjacent

to water sources and significant available croplands.

The tel is upon a high point of the aeolianite ridge, approximately 25 m above

two topographic saddles to its north and south (Fig. 3). To the west of the tel is a

ca. 2 km wide valley at 2–25 m a.s.l. that hosts Naḥal Soreq and Naḥal Gamliel that

runs parallel to the Soreq to its north. Here these wadis flow to the north-northwest

between two prominent aeolianite ridges of the southern coastal plain of Israel. To

the east runs the El-Maghar ridge (Fig. 1a, b).

West of the Yavne aeolianite ridge lies the Yavne (Palmaḥim) dune field (Fig. 1a).

However, from the Bronze Age to Byzantine times, the area of the dune field was

devoid of dunes. Dunes apparently encroached several km inland into the coastal

plain only during the last centuries (Roskin et al. 2015, 2017; Taxel et al. 2018).

�000

177

000

176

000

Yavne and Its Secrets

|

175

14*

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

644

20

20

20

Yavne

megasite

Naḥal

20

20

20

20

20

20

000

20

20

20

20

20

Main roads

20

20

20

Buildings

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

Elevation

lines

20

20

20

20

20

high: 250

20

20

20

Value

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

low: 5

20

643

30

20

20

20

000

20

20

20

20

30

20

20

20

20

20

30

20

20

30

20

20

20

30

40

30

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

20

30

20

20

20

30

20

642

20

000

30

40

C H

30

Tel Yavneh

50

L

20

S

K

40

30

R J

30

A

641

000

U

Naḥ al Sore q

M

B

20

30

20

G

30

O

04

D

40

30

30

40

500

m

40

0

30

40

30

40

30

30

Fig. 3. Elevation map of the Tel Yavne environs (drafting: Y. Gumani). Elevations are based

on the Digital Elevation Model (DEM) from the ALOS-PALSAR satellite (Alaska Satellite 210

Facility). Letters mark excavated areas at the Yavne mega site. The yellow-colored elevation

marks aeolianite ridges and remains of such ridges. The low, green-colored areas have alluvial

deposits. Note, the hypothesized remains of the ancient Soreq marked by a dashed-dot blue

line via the topographic saddle south of the tel, west of Area R.

�The Geomorphology and Sedimentology of the Tel Yavneh Environs

|

15*

Instead, the surface was comprised of sandy brown loam soil with thin sand sheet

additives (Taxel et al. 2018; Roskin and Taxel 2021) and probably served as an

agricultural area. Thus, the tel developed upon an elevated peninsula-like ridge

between two vast and flat agricultural zones; the Tel Yavne-Yavne Yam plain and the

Soreq-Gamliel valley (Fig. 1b, 3).

Main Sediment Types

The aeolianite ridge, slope, base of Tel Yavne, and Soreq valley reveal a wide

range of geological and mainly sediments dictated by fluvial, slope, and aeolian

geomorphological processes. These display granular textures from medium size

sand to clay loam with significantly different geotechnical properties that challenge

geophysical prospecting (Reeder et al. 2019). Quartz-dominated sand is a significant

component in most of the sediments and settings. The lower and moderate colluvial

slope of the tel between Areas C to H exposes a 0.3–2 m. thick, mixed grey-brownish

sandy loam anthropogenic soil bearing quartz sand pockets (up to 5 cm diam. in

places) and ceramics and other artifacts (Fig. 5a). Here at Area H, Middle Bronze

features and artifacts were found buried in 4 m thick Soreq valley sediments.

The silicates to carbonate ratio measured by FTIR of the grey-brownish sandy loam

anthropogenic soil is distinctly 1.5:1, while the modern topsoil of the site is 1:1. This

anthrosol comprises the contemporary topsoil filling the base of the aeolianite ridge

that was shaped by diverse and intense human construction and anthro-stratigraphic

buildup since Chalcolithic times. At the tel base in Areas R and C (Fig. 3) also appear

weathered exposures of aeolianite, comprised of weakly consolidated and dipping

sand beds (Fig. 5b). Here, a carbonate-rich quartz sand unit appears at the surface

and beneath the anthrosol. Carbonate-rich quartz sand comprises abundant calcium

carbonate concretions in various shapes, including root casts within loose and

massive yellow sand. FTIR silicates to carbonate ratio of the carbonate-rich quartz

sand are 1:1 as opposed to unconsolidated aeolian sand, which is 5:1. Carbonaterich quartz sand appears to be a poor, inert, and porous substrate poorly suitable

for agriculture. Therefore, it is not surprising that the sand units were targeted as a

substrate for the construction of installations.

The base of the tel is a contact zone between sequence of sandy soils and the tel

substrate, colluvial tel anthrosols (Fig. 5 c, d), and the edge of the Soreq floodplain

deposits (Fig. 5e). The sandy soils appear in a wide range of yellow-red colors with

different amounts of silt and clay contents (Fig. 5d). These soils probably range from

incipient sandy Regosols to ḥamra soils of varying maturity. Here, these ḥamra-like

soils developed upon loose sand and not upon aeolianite rock as often perceived. FTIR

�16*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

a

b

c

Fig. 4. The geomorphology and sedimentology of Naḥal Soreq: (a) The Soreq-Gamliel valley

with Tel Yavne in the background. Note the low topographic saddle on the far left where the

train station is situated (Photography: O. Ackermann); (b). The modern channel of Naḥal

Soreq, whose modern flow is partially supplied by agricultural excesses (Photography: O.

Ackermann); (c) Section in Soreq floodplain by Area J (Fig. 3). Here, couplet laminas cover

Chalcolithic remains (Photography: E. Marco).

�The Geomorphology and Sedimentology of the Tel Yavneh Environs

|

17*

a

b

c

b

e

d

Fig. 5. Photo gallery of sediments and soils (Photography: J. Roskin). (a) Grey colluvial

anthrosol/archeosediment in Area C; (b) Weathered and exposed aeolianite in Area R; (c)

Section with a wide range of sediments suggesting periods of deposition and truncation in

Area C; (d) Grey colluvial anthrosol/archeosediment overlying sandy ḥamra-like soils; (e)

Grumusol at the edge of the Soreq floodplain by the margin of Area A.

�18*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

silicates to carbonate ratio of the ḥamra-like soil is 3:1, indicating more carbonate

than aeolian sand. Some of the sandy soils and deposits may also be anthropogenic.

(1–3 m thick). Within this region, remains of the aeolianite ridge were found at

depths of 3–5 m (Fig. 5b).

The fringes of the Soreq valley near the tel are slightly sloped and are comprised

of a sequence of brownish sandy Grumusol (up to 4 m thick) bearing charcoals and

ceramic artifacts at depths of 1.5 and 3.5 m (Fig. 5e). A prismatic brown and more

clayey Grumusol comprises the upper 1.5 m of the section with up to ~40% carbonate

concretions. FTIR silicates to carbonate ratio of this floodplain material are 3:1,

similar to the ḥamra-like sediment.

In the flat Soreq-Gamliel valley, sand layers appear more frequently at shallow

depths and interfinger with clay loam units often, hosting groundwater (Fig. 4c).

The sandy character of many of the sediments allowed good drainage of water that

limited erosive fluvial effects and often generated competent drainage of the soils

making them suitable for agriculture.

The surrounding deposits and raw materials of Tel Yavne were well-utilized: Soreq

floodplain clay-rich deposits were mixed in the sandy substrates below the walls, and

aeolianite stones were used as construction materials. Young beach rock slabs and

shells, probably from the shore interface and beach pockets near Yavne-Yam, were

used as construction materials and in plaster production respectively (Bar et al., this

volume). Altogether, an extensive range of sediment types and textures reflect the

fluctuations and complex interactions between human activity and the environment,

and periods of post-abandonment impacts on sheet flow and the overflow of the

Soreq. The character of each sediment reflects a unique anthro-geomorphic response

to human or human-induced landforms.

The Morpho-Fluvial Impact of the Plio-Pleistocene Soreq Drainage system

The morpho-fluvial impact of the Plio-Pleistocene drainage system of Naḥal Soreq

explains the wide valley of Naḥal Soreq east and north of Yavne, with a gap of several

km between the Yavne aeolianite ridge and its continuation by the southern outskirts

of Reḥovot (Fig. 1a, b). This gap suggests that the flow and ancient canyon of the

Soreq never permitted the development of a pre-aeolianite dune.

The topographic saddles on both sides of Tel Yavne may be remains of ancient

pathways of the Soreq before or following the development of the aeolianite ridge

despite the lack of observed fluvial remains (Fig. 3). If so, this hypothesized ancient

and buried channel may still be a conduit for shallow underground floodwater of the

Soreq.

�The Geomorphology and Sedimentology of the Tel Yavneh Environs

|

19*

The Soreq and its tributaries in the coastal plain cross several aeolianite ridges

upstream of the Soreq-Gamliel valley. As such, a significant part of its suspended

load should include fine to medium size quartz sand grains eroded from the

aeolianites. The other fraction of the load may be dominated by cyclic dust-sourced

red Mediterranean silt-loam soil mantles (Frumkin, Stein and Goldstein 2022). These

probably originated on the steep slopes of the Naḥal Soreq segment in the Judean

Hills. During the Quaternary, ample fine-grained sediments were fluvially delivered

to the Soreq-Gamliel valley near Yavne. Different grain sizes are expected in the

Soreq-Gamliel sediments and soils as a mixture and in cases where flow was absent,

probably in the form of couplets where the lower unit is sandy and the upper loam

and clay. Fine-grained couplets are common where aeolian and fluvial environments

interact (aeolian-fluvial interactions; Fig. 4c) (Robins et al. 2022).

The Soreq-Gamliel valley is often flooded and is part of the (spatial) water losses

(contribution) to the shallow aquifer along the path. Unfortunately, fluvial sediment

monitoring in Israel is sparse, and there is limited data on the modern Soreq sediment

budget. However, the study of the excavated sections at the Yavne mega site may be

able to provide valuable insight that can be inferred to reconstruct ancient flows and

sediment loads and investigate sedimentation amounts and rates.

Ancient Fluvial Regime of Naḥal Soreq

The general hydrological regime of Naḥal Soreq in the Late Holocene was probably

similar to earlier Holocene times and relatively stable. In the Judean Hills, the

vegetation cover, the karstic and jointed nature of the strata, and the thin sediment

cover do not allow short-term rainwater storage on the slopes and flow within the

alluvium. The theorized stable character of the Soreq basin in the Hills for at least

100,000 years (Ryb et al. 2013) suggests that the flow regime was relatively steady

and usually dry (see below). The paucity of fluvial terraces in the Hills is also field

evidence that the Soreq flows produced a limited range of flow discharge values

during the Holocene. Therefore, these low floodplains are stable surfaces and are not

usually prone to flooding (Roskin et al. 2022). This stable regime, though, does not

necessarily imply that the sediment loads were the same. However, a mostly stable

fluvial-sedimentological regime may have led to general gradual aggradation in the

Yavne-Gamliel plain.

The runoff and flow regime in Naḥal Soreq differs today from historic and

prehistoric times due to the current climate and human-shaped geomorphology.

While the terraced slopes reduce the present-day flow, increased and concentrated,

urban runoff may cause a trade-off. These low fluvial load values may not indicate

�20*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

brief intervals when terraces were absent, and erosion rates of fine-grained material

were higher, especially when vegetation cover was degraded by anthropogenic

agents or decimated, say by fire (Inbar, Tamir and Wittenberg 1998). However, the

fluvial regime may have been different in the past before the intensive terracing of

its headwaters in the Judean Hills, mainly since the Roman–Byzantine periods and

especially in Ottoman times (Porat et al. 2019). Thus, before the terracing of the

uplands, sediment yield and consequent deposition were probably higher in the

coastal plains, leading to floodplain aggradation near Yavne. The fertile sediment fill

may mask underlying aeolianite exposures that may have been fluvially eroded, and

mixed with the suspended load, resulted in sandy loam floodplain deposits.

Role of the Fluvial Regime of Naḥal Soreq upon Ancient Settlement

The sediment availability and depositional regime of the coastal plain of Israel

are highly variable. In several broad valleys, thick 3–5 m alluvial deposits cover

Chalcolithic sites (Itach et al. 2019; Brink et al. 2019). In other valleys, even Roman–

Byzantine fills hide evidence of earlier energetic flows that deposited coarse sand,

pebbles, and gravel (Roskin, Asscher and Bennestein 2021). It appears that the

depositional environment of Naḥal Soreq in the Yavne environs is one of the most

prominent ones on the whole coastal plain of Israel. This fact makes the Yavne

environs a prime settlement setting at a regional level!

The Soreq-Gamliel plain narrows to the north. The southern coast has ephemeral

to locally perennial stream segments. The central coastal streams and Sharon and

Carmel coast streams are perennial and transect a narrower coastal segment than

south of the Yarkon. Thus, the southern coast’s longer and less steep gradient allows

for more fine-grained sedimentation. Furthermore, the Soreq stream has one of the

largest basins and, accordingly, sediment availability for deposition on the coast.

Thus, the Terra-Rossa sourced clay-rich Grumusol valleys of the western segment

of Naḥal Soreq near Yavne, still within the Mediterranean climate zone, are one of

the most extensive and most fertile zones of the coastal plain. This may explain the

region’s relatively high 19th-century Arab village density (Schaffer and Levin 2016).

Possible Role of Late Holocene Dune Incursion on the Naḥal Soreq Path

The aeolianite ridges south of Yavne are undergoing substantial erosion leading to

fluvial choking of local wadis with sand (Laronne and Shulker 2002). This process

can lead to overflow and enhanced floodplain sedimentation. Current urbanization

that increases local discharges not fit to natural channel cross-sections can also

enhance flood-plaining. This process may have also happened during peak times of

ancient settlement.

�The Geomorphology and Sedimentology of the Tel Yavneh Environs

|

21*

The flat base of the tel is actually the edge of the Naḥal Soreq floodplain that seems

to have significantly expanded and aggraded several meters of sediments since the

middle Holocene, covering Bronze Age and Byzantine features as reported 6 km

downstream (Jakoel and Rauchberger 2014). The incursion of sand sheets during

the late Holocene across the Yavne dune field and into the Soreq valley (Fig. 1a),

downstream of the site where the Soreq breaks to the west, may have contributed

to channel narrowing, meandering and loss of transmission energy, leading to

upstream sedimentation in floodplains and vertical and lateral growth of the

floodplains. Damming the Soreq by encroaching dunes would surely lead to water

bodies depositing amplified amounts of sediment. However, the amount of dunes

required to dam a stream the size of the Soreq were probably not present before the

last centuries.

Conclusions

The ancient Tel Yavne environs have undergone considerable and non-linear

anthrogeomorphic evolution since the middle Holocene (Chalcolithic times). Earlier

aeolian and fluvial processes shaped the physical setting and character of the region.

The Naḥal Soreq-Gamliel valley floor was several meters lower and less wide than

today’s geometry. The hydrological regime was probably more copious and reliable

for ancient water needs. The agricultural soils were slightly different than today’s

that may explain the transition from vines during Mishanaic times to orchards and

field crops today.

It is unclear if the geologically rapid aggradation and growing spatial cover of the

fluvial deposits along the fringes of the Naḥal Soreq valley had a deterministic impact

during the settlement and expansion phases of ancient Yavne. This preliminary study

highlights the importance of detailed geoarchaeological investigations to decipher

ancient landscapes that are found to be substantially different from today’s.

References

Avron M. 1973. Sediment Yield and Differences in Erosional Regimes in Several Streams of Israel.

M.A. thesis. The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (Hebrew).

Bar A., Haddad E., Asscher Y., Zuiden A. van, Elimelech C., Bookman R. and Zviely D. This volume.

Beachrock Finds at Yavne-East Excavations: Preliminary Results.

Brink E.C.M. van den, Ackermann O., Anker Y., Dray Y., Itach G., Jakoel E., Kapul R., Roskin J. and

Weiner. S. 2019. Chalcolithic Groundwater Mining in the Southern Levant: Open, Vertical

Shafts in the Late Chalcolithic Central Coastal Plain Settlement Landscape of Israel. Levant

51(3):236–270.

�22*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

Dan J., Fine P. and Lavee H. 2007. The Soils of the Land of Israel. Jerusalem (Hebrew).

Dan J., Yaalon D.H., Koyumdjisky H. and Raz Z. 1972. The Soil Association Map of Israel. Israel

Journal of Earth Sciences 21:29–49 (Hebrew).

Dan J., Yaalon D.H., Koyumdjisky H. and Raz Z. 1976. The Soils of Israel (Volcani Center Institute

of Soils and Water Pamphlet 159). Bet Dagan (Hebrew).

Frumkin A., Stein M. and Goldstein S.L. 2022. High Resolution Environmental Conditions of the

Last Interglacial (MIS5e) in the Levant from Sr, C and O Isotopes from a Jerusalem Stalagmite.

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 586:110761.

Gophna R., Paz Y. and Taxel I. 2010. Al-Maghar: an Early Bronze Age Walled Town in the Lower

Soreq Valley and the EB IB–II Sequence in the Central Coastal Plain of Israel. Strata: BAIAS

28:9–37.

Govmap - Soil Types Layer https://www.govmap.gov.il/?c=197509.43,661024.28&z=5&lay

=SOIL_TYPES (retrieved 11 January 2022)

Harel M., Amit R., Porat N. and Enzel Y. 2017. Evolution of the Southeastern Mediterranean

Coastal Plain. In M. Harel, R. Amit, N. Porat and Y. Enzel eds. Quaternary of the Levant:

Environments, Climate Change, and Humans. Cambridge. Pp. 433–446.

Inbar M., Tamir M.I. and Wittenberg L. 1998. Runoff and Erosion Processes After a Forest Fire

in Mount Carmel, a Mediterranean Area. Geomorphology 24(1):17–33.

Itach G., Brink E.C.M. van den, Golan D., Zwiebel E.G., Cohen-Weinberger A., Shemer M., Haklay

G., Ackermann O., Roskin J., Regev J., Boaretto E. and Turgeman-Yaffe Z. 2019. Late Chalcolithic

Remains South of Wienhaus Street in Yehud, Central Coastal Plain, Israel. Journal of the Israel

Prehistoric Society 49:190–283.

Jakoel E. and Rauchberger L. 2014. El-Jisr. HA–ESI 126 (August 28) https://www.hadashot-esi.

org.il/report_detail_eng.aspx?id=9565&mag_id=121 (accessed July 23, 2022).

Laronne J.B. and Shulker O. 2002. The Effect of Urbanization on the Drainage System in a

Semiarid Environment. In E.W. Strecker and W.C. Huber eds. Global Solutions for Urban

Drainage (Proceedings of the Ninth International Conference on Urban Drainage, Portland,

OR, 8–13 September 2002). Reston, VI. Pp. 1–10.

Malinsky-Buller A., Barzilai O., Ayalon A., Bar-Matthews M., Birkenfeld M., Porat N., Ron H.,

Roskin J. and Ackermann O. 2016. The Age of the Lower Paleolithic Site of Kefar Menachem

West, Israel—Another Facet of Acheulian Variability. Journal of Archaeological Science:

Reports 10:350–362.

Negev M., Simin A and Keller P. 1970. Surface Water in the Soreq Drainage Near the Coastal

Road. Tahal report HG/70/024. Tel-Aviv (Hebrew).

Nir Y. 1964. Studies on Recent Coarse Clastic Sediments from Nahal Soreq. Israel Journal of

Earth Sciences 13(1):27.

Porat N., López G.I., Lensky N., Elinson R., Avni Y., Elgart-Sharon Y., Faershtein G. and Gadot Y.

2019. Using Portable OSL Reader to Obtain a Time Scale for Soil Accumulation and Erosion in

Archaeological Terraces, the Judean Highlands, Israel. Quaternary Geochronology 49:65–70.

�The Geomorphology and Sedimentology of the Tel Yavneh Environs

|

23*

Reeder P., Pol H.M., Bauman P., Darawsha M., Workman V., Yanklevitz S., Freund R. and

Savage C. 2019. From Bethsaida to Yavne and Beyond. In F. Strickert and R. Freund eds. A

Festschrift in Honor of Rami Arav “And They Came to Bethsaida…”. Newcastle Upon Tyne.

Robins L., Roskin J., Yu L., Bookman R. and Greenbaum N. 2022. Aeolian-Fluvial Processes

Control Landscape Evolution Along Dunefield Margins of the Northwestern Negev (Israel)

Since the Late Quaternary. Quaternary Science Reviews 285:107520.

Roskin J., Asscher Y. and Bennestein N. 2021. Function and Development Stages of WadiTerrace and Field Walls in the Nahal Zanoah Valley, Judean Foothills, Israel. Judea and

Samaria Research Studies 30(2):189–220 (Hebrew).

Roskin J., Asscher Y., Khalaily H., Ackermann O. and Vardi J. 2022. The Palaeoenvironment and

the Environmental Impact of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic Motza Megasite and its Surrounding

Mediterranean Landscape in the Central Judean Highlands (Israel). Mediterranean

Geoscience Reviews 4:215–245.

Roskin J., Sivan D., Shtienberg G., Porat N. and Bookman R. 2017. Holocene Beach Buildup and

Coastal Aeolian Sand Incursions off the Nile Littoral Cell. Geophysical Research Abstracts

19:844.

Roskin J., Sivan D., Shtienberg G., Roskin E., Porat N. and Bookman R. 2015. Natural and Human

Controls of the Holocene Evolution of the Beach, Aeolian Sand and Dunes of Caesarea

(Israel). Aeolian Research 19A:65–85.

Roskin J. and Taxel I. 2021. “He Who Revives Dead Land”: Groundwater Harvesting

Agroecosystems in Sand Along the Southeastern Mediterranean Coast Since Early Medieval

Times. Mediterranean Geoscience Reviews 3(3):293–318.

Ryb U., Matmon A., Porat N. and Katz O. 2013. From Mass-Wasting to Slope Stabilization:

Putting Constrains on a Tectonically Induced Transition in Slope Erosion Mode: A Case Study

in the Judea Hills, Israel. Earth Surface Processes and Landforms 38(6):551–560.

Schaffer G. and Levin N. 2016. Reconstructing Nineteenth Century Landscapes from Historical

Maps—the Survey of Western Palestine as a Case Study. Landscape Research 41(3):360–379.

Taxel I., Sivan D., Bookman R. and Roskin J. 2018. An Early Islamic Inter-Settlement

Agroecosystem in the Coastal Sand of the Yavneh Dunefield, Israel. Journal of Field

Archaeology 43(7):551–569.

Weiner S. 2010. Microarchaeology: Beyond the Visible Archaeological Record. Cambridge.

Zaidner Y., Porat N., Zilberman E., Herzlinger G., Almogi-Labin A. and Roskin, J. 2018. GeoChronological Context of the Open-Air Acheulian Site at Nahal Hesi, Northwestern Negev,

Israel. Quaternary International 464A:18–31.

��Land and Sea: On the Relationships, Similarities, and

Differences between Yavne and Yavne-Yam from the

Persian to the Beginning of the Crusader Period

Itamar Taxel1

In antiquity, the southern coastal plain of historical Palestine (between Naḥal

Yarqon and Naḥal Besor) had a unique phenomenon in terms of local settlement

patterns and inter-settlement relationships, namely the development of pairs of

inland and seashore urban/semi-urban centers that shared a similar name and

nurtured connections based on mutual reliance alongside lines of independence

and uniqueness. This paper discusses the northernmost pair of these “twin cities,”

i.e., Yavne and Yavne-Yam (Figs. 1, 2).2 Although the first major phase of existence

of both settlements occurred as early as the Middle Bronze Age II, this study only

concentrates on the Persian period until the beginning of the Crusader period (fifth

century BCE–twelfth century CE).3 This article is based on the preliminary published

Yavne-Yam excavations and Yavne Map survey projects (see below) and on the

published and unpublished results of many excavations carried out in Yavne, mainly

before the present mega-excavation. Considering this vast amount of data, in the

following pages, I will rather briefly describe the historical evidence and primarily

focus on the archaeological findings regarding Yavne and Yavne-Yam (and, to a

1

2

3

This article is dedicated to the blessed memory of my teacher, colleague, and friend, Professor

Emeritus Moshe Fischer, who passed away on August 22, 2021. Under the auspices of his

academic home, Tel Aviv University (hereafter TAU), Moshe dedicated much of his time

during the last three decades to the investigation of ancient Yavne, Yavne-Yam, and their

surroundings, and I will always be grateful for the opportunity I had to work with him on

these projects.

The two other most prominent pairs of this kind were Ashdod and Ashdod-Yam and Gaza

and Gaza Maiumas.

For the archaeology of Yavne in the Middle and Late Bronze and Iron Ages, see Fischer and

Taxel 2007:215–218; Kletter and Nagar 2015; Kletter, Ziffer and Zwickel 2010; Kletter,

Zwickel and Ziffer, this volume. For Yavne-Yam in the same periods, see Fischer 2005:176–

183; 2008:2073; Uziel 2008:54–114.

�26*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

lesser extent—their hinterland/s) during the discussed time period in an attempt to

provide a first cross-period and simultaneous assessment of both sites.

General Background

Yavne was one of the major ancient cities in the southern coastal plain of Israel,

situated about midway between Jaffa and Ashdod and 7 km east of the Mediterranean

(Fig. 1). The main part of the site of ancient Yavne is a large, raised tel (c. 150 dunams

in size), which developed on a natural kurkar (fossilized sandstone) hill located close

to the western bank of Naḥal Soreq, the main river of the area (Fig. 2:1). Surface

finds and architectural remains indicate that the mound was inhabited, possibly

even continuously, between the MB II and British Mandate times, although virtually

in every period the plain and hills that surround the tel were also inhabited or used

for various activities (primarily funerary or industrial; see below).4 Although the

former Arab village of Yubnā (situated on the mound) and the medieval monuments

inside and around it were already documented in the late nineteenth century CE,

modern archaeological research at the site began only in the mid-twentieth century

and continues to the present day. This activity includes dozens of (mostly salvage)

excavations carried out by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) and a thorough

regional survey of the Map of Yavne (Archaeological Survey of Israel, no. 75) carried

out by M. Fischer and the author on behalf of Tel Aviv University (TAU).5

The site of Yavne-Yam is located about 7 km northwest of the modern city of Yavne

and 2.5 km to the south of Naḥal Soreq’s estuary (Fig. 1). It developed on the shore

of a small natural bay which was delimited from the south by a promontory that

protrudes c. 75 m into the sea (Fig. 2:2). In ancient times, this bay served as one of

the few anchorages located on the southern coast of Israel (Galili 2009). The ancient

settlement stretched to the east and northeast of the promontory covering an area

of approximately 250 dunams delimited to the north, east and south by MB II earth

ramparts.6 The site was inhabited, probably continuously, until the beginning of the

Crusader period (early twelfth century CE) while only temporarily occupied during

4

5

6

Although the recent excavations revealed evidence for a Chalcolithic-period settlement on

the plain to the east of Tel Yavne (Fadida et al. 2021; Abadi-Reiss, Betzer and Varga 2022)

there is currently no indication that the mound itself was inhabited prior to the MB II.

The final survey results are yet unpublished; for a preliminary discussion of the survey

results and a review of excavations as for the early 2000s see Fischer and Taxel 2007.

In Yavne-Yam, no evidence of a pre-MB II occupation has yet been found. However, intensive

activity from the Chalcolithic period and the Early Bronze Age was found in various locations to

the north and northeast of the site (e.g., Gorzalczany 2018).

�Land and Sea: On the Relationships, Similarities, and Differences between Yavne and Yavne-Yam

|

27*

180

000

175

000

170

000

165

000

655

ran

ean

Sea

000

Bet Hanan

ter

Nahal S

or

000

Me

di

650

Gan Soreq

Tel Ya‘oz

eq

Yavne-Yam

Yavne-Yam (South)

el-Jisr

Tel Mahoz

Khirbat el-Furn

Ṭirat Shalom

Yavne dunefield P&B

645

000

Khirbat ed-Duheisha

Yavne

Ben-Zakkay

640

000

0

2

km

Fig. 1. Location map (drafting: Y. Gumenny).

the following centuries. Here too, the first archaeological investigations date back to

the late nineteenth century, but actual excavations began at Yavne-Yam only in the

1960s, followed by several salvage (IAA) excavations and (between 1992 to 2011)

a large-scale excavation project headed by M. Fischer and the author on behalf of

TAU. The TAU excavations were concentrated on six main areas: Areas A and C on the

promontory and the saddle to its east, Area B to the north of Area A over the sea cliff,

Areas B1 and B2 east of Area B, and Area T further to the east close the site’s fringes

(for preliminary discussions, see Fischer 2005; 2008; Fischer and Taxel 2014; 2021;

Piasetzky-David et al. 2020).7

7

Due to the untimely death of Moshe Fischer, the first volume of the Yavne-Yam excavations final

report, which will mainly concentrate on the MB II to Hellenistic period, is being prepared for

publication by a team headed by Alexander Fantalkin and the author (hereafter YY1, in prep.).

The second volume will deal with the Roman to Islamic periods and is prepared for publication

by the author and additional scholars (hereafter YY2, in prep.).

�28*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

1

2

Fig. 2. (1) General views of Tel Yavne, looking west (photography: M. Fischer);

(2) Yavne-Yam, looking south (photography: Sky View).

�Land and Sea: On the Relationships, Similarities, and Differences between Yavne and Yavne-Yam

|

29*

The Yavne regional survey (c. 10 × 10 km; see Fischer and Taxel 2006; 2007;

2008; 2021; Taxel 2013a), initiated in 2001 and aimed at assembling data about the

hinterland of Yavne and Yavne-Yam throughout their history, included systematic

field walking over larger areas and collecting and documenting the finds visible on

the surface. Thus far, most of the Yavne Map’s accessible area has been surveyed,

with close to 100 sites identified, dating from prehistoric times through the British

Mandate period. It should be noted, though, that most of the sites, or at least the

largest and more intensively-settled ones, are located within the eastern half of the

survey map, i.e., in the alluvial plain on both sides of Naḥal Soreq and the inland kurkar

hills. On the contrary, the western half of the area, a strip of sand dunes extending

about 5 km inland from the Mediterranean seashore, is characterized by smaller,

often short-lived sites. However, likely, additional sites predating the intensive and

relatively recent sand coverage are still hidden under the dunes.

The Persian Period

The mound of Tel Yavne, which formed the core of the settlement since the MB II,

seems to continue to be the core during the Persian period (fifth to late fourth century

BCE), as indicated by Persian-period pottery found across the mound in our survey

and a salvage excavation carried out at its northeastern fringes. Persian-period

pottery was also found in a few locations in the mound’s immediate surroundings,

including on a hill known in Arabic as el-Deir (to the west of Tel Yavne), where a

salvage excavation revealed a temple favissa containing clay figurines (Fischer and

Taxel 2007:218–219, with references therein; on the same hill a favissa of an Iron

Age temple was excavated sometime later; see Kletter, Ziffer and Zwickel 2010;

Kletter, Zwickel and Ziffer, this volume). An important contribution to the knowledge

of Persian-period Yavne was revealed in the 2019–2022 excavations to the southeast

of the mound, in the form of an extensive industrial winery (that covered an earlier,

smaller winepress, probably from the late Iron Age/early Persian period). Three

pottery kilns were attributed to a transitional late Persian-early Hellenistic phase; at

least one of them produced cooking pots. The construction of these kilns dismantled

parts of the Persian-period winery. A well discovered to the north of the winery was

probably constructed in the late Iron Age but continued to be used during the Persian

and Hellenistic periods (Haddad et al. 2021; Nadav-Ziv et al., this volume).

A substantial Persian-period phase was revealed at Yavne-Yam, mainly in the TAU

excavations (in Areas A and C). Some of the associated building remains (among

�30*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

them a complete room) were built according to the Phoenician technique combining

ashlar piers with fieldstone fills in between. Notable small finds include imported

Greek pottery, i.e., Black- and Red-Figure jugs and black-glazed bowls, fragmentary

clay figurines, and a small limestone altar (Fischer 2005:183–184; 2008:2073–2074;

YY1, in prep.). At the northern fringes of the site, to the north of the MB II rampart,

remains of a Persian-period pottery kiln and three winepresses were excavated (by

the IAA) and dated to either the Persian or Hellenistic period (Ajami and ‘Ad 2015).

These remains seem to reflect the revival of the coast after the assumed Babylonianperiod settlement hiatus of the sixth century BCE, even though Persian-period

historical sources do not mention the site. The site’s architectural and artifactual

evidence reflects the Phoenician supremacy and the permanent supply and support

of Grecized population along the southern Phoenician coast enjoyed on the eve of

Alexander the Great’s conquest (Fischer 2005:184–185; 2008:2074).

Shalev (2014:75, 112) suggested that in the Persian period, Yavne was the main

settlement in the lower Naḥal Soreq area, with Yavne and Yavne-Yam maintaining

strong connections between each other and between them and their rural hinterland.

‘Ad (2016:21, 357, Map 1) tends to attribute the status of main settlement in the

area to Yavne-Yam, while claiming that inland Yavne was seemingly somewhat less

important, constituting a large village. Noteworthy excavated and surveyed rural

settlements—farmsteads and villages of various sizes—in the area roughly between

Yavne and Yavne-Yam (see Fig. 1) include Tel Ya‘oz (Segal, Kletter and Ziffer 2006;

Fischer, Roll and Tal 2008, according to whom the site was an administrative center),

Gan Soreq (‘Ad 2016a; 2016b:53–115), Ṭirat Shalom, Ben-Zakkay and Tel Maḥoz

(Fischer and Taxel 2006).

The Hellenistic Period

The archaeological evidence for the Hellenistic period (late fourth–early first century

BCE) in Yavne is somewhat restricted, consisting of scattered pottery and a few

coins on Tel Yavne and its surroundings—including a stamped Rhodian amphora

handle (Fig. 3:1) (Fischer and Taxel 2007:221)—and a few remains unearthed in

recent excavations to the east of the mound. These include (intentionally?) disturbed

burials (second–first centuries BCE) found under the remains of a Roman-period

cemetery (Yannai 2014; Yannai and Taxel, unpublished)8 and a pottery kiln in which

8

The final report of the IAA excavations directed by E. Yannai at Yavne in 2010–2012 will be

published by Yannai and the author.

�Land and Sea: On the Relationships, Similarities, and Differences between Yavne and Yavne-Yam

|

31*

bowls, cooking pots, stands, and storage jars were probably produced and a pool

for mudbrick production, both dated mainly to the third century BCE (Haddad et

al. 2021). This dearth of archaeological materials contrasts the many references to

Yavne in the Books of the Maccabees, referring to its important role during the war of

the Jews against the Seleucids in the second century BCE. Yavne received the status

of a polis named Iamneia as early as the beginning of the Hellenistic period and had a

predominantly polytheistic population. It became part of the Hasmonean kingdom in

the late second century after being taken by John Hyrcanus (for recent reviews on the

literary evidence on Hellenistic-period Yavne, see Fischer and Taxel 2007:220–221;

Farhi and Bachar 2020:111–112; Safrai, this volume).

The picture reflected from Yavne-Yam regarding the Hellenistic period is quite the

opposite of that seen in Yavne in terms of abundant archaeological finds and lesser

historical documentation. The TAU and some IAA excavations revealed various

remains and rich artifactual assemblages. Building remains were found within the

settlement proper (mainly in Area A), sometimes directly over the Persian-period

structures. Correctly, some of the latter continued to be used in Hellenistic times.

Moreover, a well was built on the seashore. Three winepresses were unearthed at

the site’s northern fringes, which probably continued to be used from the Persian

period (see above). Small finds include a variety of local and imported ceramics; the

latter mainly consisting of fine table wares (notably Eastern Terra Sigillata bowls and

kraters as well as mold-made bowls) and wine amphorae with stamped handles from

the Greek islands (Fig. 3:2) as well as from southern Italy. A significant local vessel

is a jug whose handle bears a stamp of a certain Aristokrates, the agoranomos (the

agora/market overseer), dated to 133/2 BCE. Other noteworthy objects are a clay

figurine of a harp player and a glass pendant of Harpocrates (the Greek-Egyptian

god of silence and confidentiality) (Ajami and ‘Ad 2015; Fischer 2005:188–190;

2008:2075; Nir and Eldar 1991; YY1, in prep.).

These finds are accompanied by an important Greek inscription accidentally found

at the site in the 1980s. This inscription consists of a letter and a petition representing

the correspondence dated 163 BCE between the Seleucid king Antiochus V Eupator

and the citizens of Yavne-Yam (“harbor of Iamneia”), named “Sidonians” in that letter.

The inscription mentions the latter as providing a certain “marine service” to the

king’s grandfather. Thus, the inscription should be interpreted against the background

of the Seleucid-Jewish wars and the fear of Yavne-Yam’s Hellenized population of the

Maccabean force. It should also be noted that the inscription mentioned above and

the Book of Maccabees are the first sources in which the site’s name is directly linked

to inland Yavne, as the latter’s harbor (CIIP III, No. 2267; Fischer 2005:187–188;

�32*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

1

2

0

1

Fig. 3. Hellenistic-period Rhodian amphora stamped handles:

(1) from Yavne; (2) from Yavne-Yam (photography: P. Shrago).

2008:2074–2075, with references therein). Altogether, the artifactual evidence

from Yavne-Yam reflects a society that has gone through Hellenization, with wellestablished connections within the East Mediterranean koine. The latest pottery

(including dated amphora stamps) and coins found in the Hellenistic stratum in

Yavne-Yam date the settlement’s final phase to around 100 BCE, and its destruction

can be attributed to the conquests of John Hyrcanus or Alexander Jannaeus (Fischer

2005:190; 2008:2075; YY1, in prep.).

It would be reasonable to assume that Yavne and Yavne-Yam shared—at least until

the Hasmonean expansion—some similar characteristics in terms of population and

�Land and Sea: On the Relationships, Similarities, and Differences between Yavne and Yavne-Yam

|

33*

cultural identity, even though Yavne-Yam’s people may have had, as in the Persian

period, a stronger “Phoenician” affiliation identified as such also by foreign imperial

authorities. At any rate, this “sisterhood” between the inland town and its haven

supported (and also leaned on) a relatively prosperous hinterland of farms and

villages such as the sites mentioned above of Tel Ya‘oz, Ṭirat Shalom, Ben-Zakkay

and Gan Soreq (the latter may have functioned as a settlement of foreign veterans of

the Seleucid army; ‘Ad 2016b:113–115), and the site of el-Jisr which was probably

established for the first time in the Hellenistic period (Fischer and Taxel 2006).

Although Yavne-Yam was not necessarily the only place through which imported

goods were distributed across the discussed micro-region, being the closest entrepot

suggests that it was the primary source for commodities such as wines marketed in

amphorae. Stamped Rhodian amphora handles found in our survey at Yavne (above),9

Ṭirat Shalom, el-Jisr, and other sites may testify to this activity.

The Roman Period

As will be shown below, archaeological evidence for Roman-period (late first century

BCE–fourth century CE) occupation in Yavne mainly includes funerary remains.

Architectural remains and finds associated with the settlement proper are relatively

scarce. These include pottery and coins (of both the Early and Late Roman periods)

found on Tel Yavne and its surroundings during our survey, and the lower part of

a marble statue discovered on the mound in 1937, which can be dated to the third

century CE and portrays a slightly undersized man, possibly a high provincial official

or the god Aesculapius (Fischer and Taxel 2007:224–226). Most recently, segmented

architectural remains and refuse pits from the Early Roman period (first century

BCE–first century CE) and better-preserved remains of a large structure dated to the

Middle Roman period (first–third centuries CE) were unearthed in the excavations to

the east of the mound (Perry-Gal, Betzer and Varga, this volume).

However, Roman-period Yavne is most clearly illustrated by tombs of various types

and related elements which were excavated or documented since British Mandate

times in multiple locations around the mound and at different distances. Close to the

eastern foot of Tel Yavne, clusters of tombs were found, consisting of built cist tombs,

9

The single Rhodian amphora handle found in our survey at Yavne was discovered on the

northern slope of the mound itself.

�34*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

at least one built vaulted tomb, and about 120 infant jar burials (Fig. 4:1),10 limestone

sarcophagi, and at least two lead coffins. Most of these burials were dated, based on

the pottery, glass and other finds associated with them, including the jar types used

for the infant burials, to the mid/late first to second/third century CE. Interestingly,

some of these tombs were covered with thick deposits of pottery production waste

and domestic refuse from the late Byzantine and beginning of Early Islamic periods

(see Jakoel et al., this volume; Fischer and Taxel 2007:227; Segal 2011; Yannai 2014;

Yannai and Taxel, unpublished; Varga, Betzer and Weingarten 2022; IAA Mandatory

Archive, file Yibna, SRF_194). To the north of Tel Yavne, a mausoleum was excavated

containing two sarcophagi and many finds (including gold jewelry) dated to the first–

second century CE. Moreover, a built vaulted tomb that probably dates to the Late

Roman period was also unearthed here. More distant tombs—single and clustered

burial caves—were excavated between 1.5 to 4 km to the west and south of Tel Yavne.

These caves had loculi, arcosolia, or floor-cut troughs, and their contents date them

to various stages of the Roman as well as to the Byzantine period; some of the caves

contained limestone ossuaries which clearly attribute these burials to the Jewish

population which resided in Yavne or its immediate vicinity during the first to early

second century CE. A fragment of another ossuary found in our survey on the mound

itself should be added to this class of finds. Fragmentary (and complete?) sarcophagi

made of limestone and marble were found in various locations around the mound

since the late nineteenth century. A limestone slab, apparently a tombstone initially

identified as a sarcophagus fragment, bears a Latin inscription indicating that the

deceased was Julia Grata, the wife or daughter of Mellon, the local Roman procurator

(financial officer or governor) of Yavne in the early first century CE (CIIP III, No. 2268;

Fischer and Taxel 2007:227–230).

These finds, which clearly point to the coexistence of Jewish and polytheistic

communities in Yavne, seem to reflect rather faithfully the historical sources related to

Yavne. According to these sources, the town had a mixed Jewish and gentile population

since the beginning of the Roman period, including when Yavne constituted a royal

estate from King Herod’s time until about the mid-first century CE.11 Following the

10

Close to 100 jar burials were discovered in Yannai’s excavation (Yannai and Taxel,

unpublished), and about 20 additional jars were found in the recent excavations (Alla

Nagorsky, pers. comm., May 2022).

11

It was recently suggested that Yavne even minted coins for a short period in the mid-first

century BCE, following the Roman conquest and the apparent upgrading of the town’s

administrative status (Farhi and Bachar 2020).

�Land and Sea: On the Relationships, Similarities, and Differences between Yavne and Yavne-Yam

|

35*

destruction of the Second Temple and up until the Bar Kokhba Revolt, Yavneh was a

major center of Jewish learning. Sometime in the second century or shortly afterward,

Samaritans began to settle in Yavne and its vicinity, apparently at the expense of the

declined Jewish population (see CIIP III:152–154; Farhi and Bachar 2020:112–113;

Fischer and Taxel 2007:221, 223–224, with references therein).

Compared to Yavne, Roman-period Yavne-Yam is lesser known from historical

sources. However, the apparent (continuous) relation between the two is attested

by first- and second-century CE Roman authors, e.g., Pliny the Elder, who mentioned

Iamneae duae, altera intus (“the two [towns of] Iamneia, one of them inland”; Farhi

and Bachar 2020:113; Piasetzky-David et al. 2020:470, with references therein).

Still, the archaeological evidence from Yavne-Yam points to an apparent gap in the

site’s occupation from the time of the Hasmonean destruction to about the early first

century CE. Scant architectural remains dated to the first or second centuries CE

were unearthed within the settlement proper, in Areas B and B1 (and possibly B2),

accompanied by contemporary pottery, coins, and some fragments of chalk vessels

(such as “measuring mugs”) typical to the Jewish material culture of Early Roman

times. Also tentatively attributed to this period is a Latin-inscribed bronze personal

tag (signaculum) of a ship’s operator (Fig. 4:2), which was found in an Early Islamic

context (CIIP III, No. 2273; Fischer 2005:190–191; Eich and Eck 2009; PiasetzkyDavid et al. 2020:473, 545; YY2, in prep.). In the IAA excavation at the northern

fringes of the site, evidence for the renovation and continuous use of the three

Persian-Hellenistic winepresses (above) into the first and second centuries CE was

found, in addition to an Early Roman storeroom that served one of the winepresses

and another installation of an unknown nature, perhaps part of a workshop which

produced fishing gear. The finds accompanying these remains included additional

fragments of Jewish chalk vessels and several Jewish coins from the Jerusalem mint.

Also attributed to this period is a cluster of about 20 built cist tombs (Ajami and

‘Ad 2015). Funerary remains dated to the Early Roman period were also revealed

in previous (the 1960s and 1980s) excavations at the foot of the MB II rampart and

over its northern and northeastern sections, in the form of four additional clusters

of tombs, primarily built cist tombs but also rock-cut chamber tombs, dug pit tombs,

one jar burial, and three limestone ossuaries. The latter naturally indicates Jewish

presence at the settlement during this period (Ayalon 2005; Piasetzky-David et al.

2020:477–482).

The Middle and Late Roman period (second–fourth centuries CE) at Yavne-Yam

is similarly represented by segmented architectural remains, mostly plastered

industrial installations, walls, and drainage channels excavated in Areas A, B, B1 and B2

�36*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

(Fischer 2005:191; Piasetzky-David et al. 2020:474; YY2, in prep.). These are

accompanied by five rock-cut arcosolia burial caves excavated in the 1980s on a hill to

the northeast of the settlement; based on their contents, at least some of these caves

were hewn and used already in the third or fourth century CE, most probably by a

polytheistic population, and continued in use into the Byzantine period (PiasetzkyDavid et al. 2020:482–544, 549).

Archaeological evidence for Roman-period activity in the area between Yavne and

Yavne-Yam is rather poor. The most notable site in this regard is el-Jisr (see Fig. 1),

where our survey revealed some Early Roman-period sherds (Fischer and Taxel

2006), and later IAA salvage excavations unearthed remains of a contemporary

cemetery composed of cist tombs, clusters of storage jars and a refuse pit. The identity

of the population who occupied the site during this period is unknown (Ajami and

Rauchberger 2008; Jakoel and Rauchberger 2014).

1

2

0

1

Fig. 4. (1) Part of a Roman-period cemetery with infant jar burials from Yavne (photography:

E. Yannai); (2) Roman-period signaculum from Yavne-Yam (photography: P. Shrago).

�Land and Sea: On the Relationships, Similarities, and Differences between Yavne and Yavne-Yam

|

37*

The Byzantine Period

This period no doubt represents the heyday of Yavne in antiquity. Literary (mainly

ecclesiastical) sources of the early fourth–seventh centuries CE, archaeological

evidence (below), and the depiction of Yavne on the late sixth-century Madaba

mosaic map, with the accompanying Greek inscription “Iabneel is also Iamneia” (CIIP

III:154–156; Fischer and Taxel 2007:230–231, with references therein), indicate that

Byzantine-period Yavne had a mixed population of Christians, Samaritans and perhaps

Jews and that the place grew in size and importance to form a medium-sized town.

The distribution of surface finds dated to the fourth and mainly fifth to seventh

centuries CE is most extensive in Yavne compared to earlier and later periods and

includes widespread areas around the mound. Our survey, which preceded the

intensive IAA excavations to the east of Tel Yavne (below), revealed numerous

Byzantine-period finds, including pottery, coins, marble, granite and limestone

architectural and furnishing elements as well as other small finds (Fischer and Taxel

2007:232–233). The latter include a fragmentary ceramic vessel/object decorated

with the motif of the Holy Cross on Golgotha depicted upside-down (Fig. 5:1). These

finds are accompanied by two marble slabs with incised Samaritan inscriptions

containing the Ten Commandments that were found in the area of Tel Yavne in the early

and late twentieth century, and which can be dated to either the Byzantine or Early

Islamic periods (CIIP III, Nos. 2265, 2266; Fischer and Taxel 2007:243, 245–246).

Segmented Byzantine-period architectural remains, including pottery production

kilns and refuse pits (some related to pottery workshops), were unearthed in smallscale salvage excavations or documented in inspection activities carried out in

various locations around Tel Yavne between the 1980s and early 2000s (see Fischer

and Taxel 2007:233, 235, 237–239; Feldstein and Shmueli 2011; Feldstein and ‘Ad

2014; Kletter and Nagar 2015:21*–26*; Segal 2011). Some of the excavated remains

provided the first evidence for the production of the so-called Gaza amphorae (or

Late Roman Amphora 4) in Yavne, the hallmark of the wine industry and marketing

on the southern coast of late antique Palestine.

A substantial contribution to our knowledge about Yavne in the Byzantine and

beginning of the Early Islamic periods was provided by the recent extensive IAA

excavations to the east and northeast of the mound. Eli Yannai’s excavations (2010–

2012) unearthed well-preserved remains of a pottery workshop that included

two clusters of three kilns each and four peripheral, colonnaded buildings which

enclosed the kilns from all directions. The various parts of the complex collapsed

simultaneously during a major earthquake. The collapse of the kilns, or at least

�38*

|

Yavne and Its Secrets

the fully excavated one, which contained dozens of whole in situ bag-shaped jars,

occurred while they were loaded with already fired vessels. The ceramic evidence

from the kiln complex confines the time of the collapse to the seventh century CE,

and palynological assemblages that included spring-blooming plants trapped under

the collapse strongly suggest that the destruction of the kiln complex occurred

as a result of the historically documented earthquake of June 659 CE. There is

no evidence of a restoration of the pottery workshop after the earthquake. This

workshop specialized in the production of bag-shaped jars, Gaza amphorae, and a

newly identified type of globular amphora; the latter was relatively short-lived and

was documented only in the Yavne region and in Egypt. Other noteworthy Byzantineperiod remains unearthed in Yannai’s excavations belonged to a (private? or public?)

building paved with white and colored mosaics, which was probably built in the sixth

century and abandoned during the seventh century CE (Yannai 2014; Langgut et al.

2016; Taxel and Cohen-Weinberger 2019; Yannai and Taxel, unpublished). The more

recent excavations (2019–present) revealed, among other remains, sections of large

buildings associated with industrial activity, seven winepresses, a glass workshop, a

water reservoir, pottery workshop waste piles, and domestic refuse dumps. Most of

these remains are dated to the sixth and seventh centuries, with some reflecting a

more prolonged period of activity, into the eighth century CE (for further discussions,

see Gorin-Rosen et al., this volume; Nadav-Ziv et al., this volume; Tsuf, this volume;

for preliminary reports see Nadav-Ziv 2020; Nadav-Ziv et al. 2021; Varga, Betzer and

Weingarten 2022). Altogether, these remains shed much new light on Yavne in Late

Antiquity, specifically on its intensive and varied industrial activity and potential

major role in the regional (and inter-regional?) economy.

This regional perspective brings us back to Yavne-Yam. Unlike the rich archaeological evidence (below), literary sources on Byzantine-period Yavne-Yam are

meager. They seem to include only two early sixth-century CE Syriac essays dealing

with the life and activity of the Monophysite bishop Peter the Iberian. He spent his