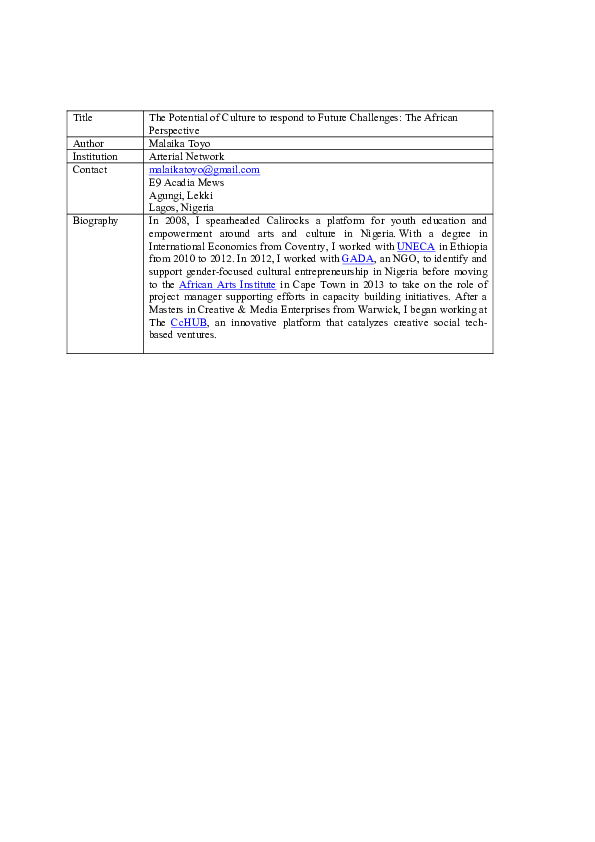

Title

Author

Institution

Contact

Biography

The Potential of Culture to respond to Future Challenges: The African

Perspective

Malaika Toyo

Arterial Network

malaikatoyo@gmail.com

E9 Acadia Mews

Agungi, Lekki

Lagos, Nigeria

In 2008, I spearheaded Calirocks a platform for youth education and

empowerment around arts and culture in Nigeria. With a degree in

International Economics from Coventry, I worked with UNECA in Ethiopia

from 2010 to 2012. In 2012, I worked with GADA, an NGO, to identify and

support gender-focused cultural entrepreneurship in Nigeria before moving

to the African Arts Institute in Cape Town in 2013 to take on the role of

project manager supporting efforts in capacity building initiatives. After a

Masters in Creative & Media Enterprises from Warwick, I began working at

The CcHUB, an innovative platform that catalyzes creative social techbased ventures.

�Abstract

With the 2015 deadline for the MDGs fast approaching there is an argument for more human-centered

approaches that address entrenched concerns such as social exclusion, marginalization and inequality.

With this comes the increasing recognition of culture as a major tool in contextualizing development

–particularly the contributions and potential of cultural and creative industries to promote local

community development. However, in spite the global debate on creative economy, the Common

African Position on a post-2015 sustainable development agenda still makes no mention of the role of

culture in ensuring localized ownership of future development agendas. This paper considers the

relevance of culture to Africa’s Post-2015 development strategy and develops a critical analysis of the

strategic usefulness of the Nairobi Plan of Action on Cultural and Creative industries in guiding local

and regional understanding of the ways cultural policies can work to support social and economic

development.

Keywords: Creative economy, Cultural policy, creative industries, cultural industries, Africa,

development

Word count: 5467

2

�Table of Contents

Introduction

Evolving Concept of the Creative and Cultural Industries

The growing importance of culture to development and in Africa

Towards an understanding of the relevance of the Nairobi Plan of Action

Recommendation

Conclusion

Reference

Appendix

3

4

5

6

8

10

11

12

14

�Introduction

In the last century, the world has been through many frameworks for development and each

successive framework has sought to take a more optimistic view than the last in its approach to

addressing the challenges of development. Addressing the models and frameworks for development

and their challenges requires a growing availability of comprehensive, coordinated and contextualized

approaches. For such approaches to be human-centered and address entrenched concerns such as

social exclusion, marginalization, inequality and the unsustainable use of natural resources, they need

to be sustainable.

As a result, an unprecedented global consensus to find ways to tackle some of the world’s most

pressing development challenges was arrived at through the Millennium Development Goals

(MDGs)1 - with the core objective of eliminating poverty.

Still, even with such a strong consensus, the MDGs like previous frameworks for development

continue to face strong contextual issues and thus lacks localized ownership (See: Easterly, 2009;

Puko and Whitman, 2012; Vandermootele, 2012; Waage et al, 2010). In my view, localized

ownership comes through the embedding of values, particularly those values steeped in culture. As

will be shown in this paper a culture of development which is contextualized has great potential for

enabling and driving rapid development.

By 2015 we will have arrived at the deadline set for attaining the MDGs. It has been argued therefore

that beyond the MDGs - although a successful tool for advocacy and benchmarking development - the

world is still in need of a more sustainable institutional framework which is in keeping with the

concept of a ‘Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda’ 2 . (See: Puko and Whitman, 2012;

Vandermootele, 2012; Waage et al, 2010).

This renewed call for a more sustainable framework comes with the recognition that culture will serve

as a major tool in contextualizing development –particularly the contributions and potential of cultural

and creative industries in promoting local community development. Moreover, this point is

particularly pertinent with regards to Africa, which has an expanding labor force and creative

enterprises that exist with the potential to create linkages between culture, community building and

economic development (See: Kwanasie et al., 2009; Ruigrok, 2008).

Against this backdrop, in this paper, I take a closer look at the relevance of culture in Africa’s post2015 sustainable development agenda given the disregard of culture as a policy issue by policymakers

in Africa. I will further support this assessment by making a critical analysis of the strategic

usefulness of the 2008 Nairobi Plan of Action on Cultural and Creative industries (NPoA) as a tool in

guiding local and regional understanding of the ways cultural policies can work to support social and

economic development.

I look at the NPoA as it presents an Africa-specific framework that demonstrates a cultural approach

building on the gains of the MDGs and which has the potential to foster local ownership and drive

normative action. Altogether these components lead to greater acknowledgement of the relational

1

http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/: (1) To eradicate extreme poverty and hunger; (2) To achieve universal

primary education; (3) To promote gender equality and empowering women; (4) To reduce child mortality rates;

(5) To improve maternal health; (6) To combat HIV/AIDS, malaria, and other diseases; (7) To ensure

environmental sustainability; (8) To develop a global partnership for development.

2

The outcome document of the 2010 High-level Plenary Meeting of the General Assembly on the

MDGs requested the Secretary-General to initiate thinking on a post-2015 development agenda and the outcome

of the Rio+20 Conference on Sustainable Development initiated an inclusive intergovernmental process to

prepare a set of sustainable development goals (SDGs). There is broad agreement on the need for close linkages

between the two processes to arrive at one global development agenda for the post-2015 period, with sustainable

development at its center. (http://www.un.org/en/ecosoc/about/mdg.shtml)

4

�interdependence between the local context and the contributions of individuals to their social and

economic transformation.

Methodologically, the argument contained herein builds on critical readings and analyses of the

NPoA, while using a combination of literature review, comparative analysis and empirical facts to

deepen the analysis. This is mainly because the arguments articulated in this paper are based on global

and continental views of a future agenda that is yet to be ascertained. It is worth noting that the sole

use of secondary data proved to be an advantage to this paper by aiding in the assessment of various

strong statements that were made and created a strong foundation of supporting information that lend

substance to the arguments in this essay.

Evolving Concept of the Creative and Cultural Industries

Although it is customary to start a paper of this sort by shedding some light on the complexity and

multiplicity of meanings in the terms culture and development, for the purpose of focus, I wont3. The

focus of this paper can be divided into two main strands, (1) the role of culture in a post-2015

development agenda vis-a-vis the contribution and potential of the cultural and creative industries and

(2) an analysis of the NPoA which is a plan for the culture and creative industries in Africa. Therefore

it is important to explore and illustrate the concept of “cultural” and “creative” industries.

In the 19th century, the emergence a cultural industry was spurred on by global socio-economic and

political changes. The production and distribution of art that had up to that time prospered under

forms of sponsorship and patronage, reorganized itself around the market model that had become

typical of the time. The organization of the market for creativity and creative products broadened and

incrementally became more complex in form, having at its core “a symbolic or expressive element

(UNESCO, 2013)”.

More recently, the application of communication technology, branding and

information to the market has turned it into the cultural industry we know. In its present form the

cultural industry is a job and wealth creator, and its myriad sectors constitute what is termed the

“creative economy” (Hesmondhaigh, 2007:4)4.

The 2005 Nairobi plan of Action defines cultural industry as “the mass production and distribution of

products, which convey ideas, messages, symbols and opinions, information and moral aesthetic

value” (2005:5). The plan uses the UNESCO definition which states that cultural industries “produce

tangible and intangible artistic and creative output and have a potential for wealth creation and

income generation through the exploitation of cultural assets and production of knowledge based

goods and services (both traditional and contemporary). The definition further points out that the

term cultural and creative industries are used interchangeably. In the case of the former, emphasis is

on industries whose inspirations derives from heritage, traditional knowledge and the artistic elements

of creativity and the latter which applies a much wider productive set include goods and services

produced by individual creativity, innovation, skill and talent in the exploitation of intellectual

property.

Some argue that culture and creative industries not only drive growth through the creation of value,

but have also become a key element in the innovation system of the entire economy (UNESCO &

UNDP, 2013). This means that these industries contribute substantial economic value, while

stimulating the emergence of new ideas and technologies, and the process of transformative change.

Whatever the case, whether big or small, cultural and creative industries are increasingly contributing

to the global economy.

3

For an in-depth exploration of these concepts, see my research paper Toyo, M. (2013) Effectively integrating

culture into the Post-2015 Sustainable Development Agenda: An African Perspective

4

Reference to the “Creative economy” in this document consist of cultural goods and services which are at the

core of a powerful new economy as well as manifestations of creativity in domains that will not be understood

as cultural. See UNESCO & UNDP report for a comprehensive analysis of the definition of ‘creative economy’

5

�Such contribution is not a function of the definition, classification and mode of recognizing “cultural”

or “creative” industries5, but arise from the different means of production involved. Irrespective of

the diversity of definitions, it is clear that these various modes of production tend to involve the same

collection of industries that deal with distribution and production of copyrighted materials. In general,

these specific industries include: the creative arts: cultural heritage; audio-visual media (music,

video, television, film and video game); print media and publishing and other subsidiary industries

such as retail bookselling, commercial art dealer, design, advertising, fashion and architecture etc.

Some models include industries like sport and software, by and large; these classifications look very

similar (Thorsby, 2002).

Critiques point out that although it seems plausible that cultural expressions could be the source of

ideas, stories and images that can be reproduced in other forms in different economic sector, there is

lack of a mechanism the clearly identifies what drives creativity. It may simply be that more

innovative firms are buying more creative inputs such as branding, design and advertising. Therefore,

one cannot say for sure that all aspects of social, economic and political creativity are generated from

cultural and creative process themselves (UNESCO & UNDP).

For this reason, in this paper, the contributions from activities classified under the cultural and

creative industries will be used to show both the economic value these industries can bring and the

increasing symbolic relationship between culture, economy and place.

The growing importance of culture to development in Africa

Estimates are that the creative economy is growing annually at 5% per annum worldwide, accounting

for nearly 8% of annual turnover of the global economy. This figure is expected to triple in size

globally by 2020 (Howkins, 2001). At a continental level, the creative sector in the Middle East is

experiencing growth rates of 17.6%; 13.9% in Africa, 11.9% in South America; 9.7% in Asia; and

6.9% in North and Central America (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2008). In Africa, cultural and creative

industries form a large part of the informal economy and have shown huge potential to contribute

beyond economic measures to redressing inequality and engaging local community. For example, in

Newton and Soweto in South Africa, a culture-led urban development strategy drew on political

history and the local culture to boost the economy through culture and tourism based activities. By

giving these districts new images, the City’s development agency was able to transform them into

vibrant and income generating areas; attracting many local artists and serving as new hubs of cultural

life in South Africa (D’Almeida, 2009).

According to UNCTAD (2010), world trade in cultural products has continued to increase despite the

recent fragility of the global economy. Gross worldwide tourism grew at an average rate of 7% from

1998 to 2010 and cultural tourism that relies on tangible and intangible cultural assets accounts for

40% of world tourism revenues (UNWTO, 2011). In addition, cultural and creative industries also

contribute to employment. Depending on the scope of the sector, the contributions of cultural

industries usually account for around 2 to 8% of the workforce in any given economy (UNCTAD,

2010). It is further argued that these industries are equally important in promoting other non-monetary

benefits. For instance, they often provide tools to fight poverty by broadening the capacities and

opportunities of vulnerable groups, accelerating resilience by fostering intellectual dialogue,

proffering conflict resolution and promoting equality. Clearly, from these points of view, culture is a

valuable resource. Thus promoting and supporting cultural expressions strengthens the social capital

of a community and fosters trust in public institutions (UNESCO, 2012).

Beyond the potential for culture as an economic and social asset, it is necessary to reflect on how

various models of development and their accompanying frameworks have failed to capitalize

on culture as a means/vehicle of/for delivering sustainable solutions to current and emerging

developmental issues. UNCTAD (2010) defines cultural sustainability as “a development process that

5

From this point on Creative and cultural industries will be referred to as one and the same

6

�maintains all types of cultural assets from minority languages and traditional rituals to artworks,

artifacts and heritage buildings and sites”. The notion of sustainable cultural development demands

that culture-sensitive approaches address poverty eradication by acknowledging and promoting

diversity within a human rights-based approach which can facilitate intercultural dialogue, protect the

rights of marginalized groups and therefore create optimal conditions for their development.

The point on diversity is very important within the African context, as sustainable cultural and

creative approaches need to grow and thrive in an inclusive way so as to produce stable local,

regional, international outlets to support the cultural industry – access to capital and skills to create

products that can compete globally requires cultural codependence in a continent of such cultural

plurality (Kwanashie et al, 2009). Currently, with an average annual growth rate of 5.4% (20042012), Africa is the world’s second fastest growing region - trialing only behind Asia. The points that

this essay has pressed on thus far suggest that Africa’s economic development can be enhanced

through the cultural economy of the region. Yet, according to UNCTAD’s 2008 Creative Economy

report, Africa contributes less that 1% to world trade in cultural goods and services. Concurrently, as

of 2010, it was reported that 48.5% of Africans live in poverty (on less than $1.25 per day); income

inequality is very high, 1 in 9 children die before age 5, 1 in 20 adults living with HIV accounting for

69% of the people living with HIV worldwide (MDG Report, 2013).

With all these staggering facts, the importance of focusing on the creative economy cannot be

overemphasized. Although culture cannot singlehandedly solve issues of development in Africa, as

argued by De Beukelaer (2014) it should be taken into account to make things better.

However, cautions advocacy is needed when viewing claims that creative and cultural industries

contribute to the development process through poverty alleviation, addressing inequality (including

gender), and the search for environmental sustainability. These assertions can be over-ambitious in

their scope and can detract from the power of the arguments for the broader cultural vision above

(UNESCO & UNDP, 2014: 72). These assertions have their limitations, and such limitations must be

recognized – to begin with, there exists insufficient quantitative evidence to substantiate these claims.

This is not to say they are wrong, it is merely to ensure that one does not get bogged down in specifics

at the expense of the wider picture.

Despite long term efforts to acknowledged the importance of culture and cultural diversity for

sustainable development by UNESCO and recent messages reflected in the outcome documents of the

United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio+20) entitled ‘The future we want’,

suggesting a positive evolution, The implications for the post-2015 development agenda are yet to be

seen.

In Africa, there have been considerable difficulties in translating, articulating, and marketing the

cultural turn in development studies to politicians and policy makers. This is evident in the fact that

the role of culture was not mentioned in the Common African Position on the Post-2015 development

agenda that was agreed upon on 31 January 20146. As Graan (2011) argues, where there has been

some success in convincing politicians of the validity of the concept, they tend to be at the bottom of

the food-chain without any real power.

Yet, focus remains on the local level as they have the potential to tailor action to the particular needs

of the community and respond to changes that particularly suit the culture field (De Beukelaer: 2014).

The questions remain, can local policymakers in Africa be galvanized to see the relevance of culture

to future development strategies and if they can, do they have the ability to relate to national policy

challenges - such as issues regarding export strategies matters - which tend to be difficult to deal with

at a local level.

6

This position was agreed upon by heads of State and Government of the African Union assembled in Addis

Ababa, Ethiopia, during the 22nd Ordinary Session of the Assembly of the Union on 31 January 2014.

7

�Isamah (1992) argues that traditional values of people are closely related to the pace with which such

people accept or reject the demands of modern or commercial operations. Thus it is the role of local

authorities to strengthen and empower cultural agents, the citizenry, and the public administration so

that they can reinforce the sense and the significance of developmental framework processes within

their local contexts. The Nairobi Plan of Action on cultural and creative industries is one of such

frameworks for development that seeks to integrate social development and economic growth with

other indicators of development.

Towards an understanding of the relevance of the Nairobi Plan of Action

It may be argued, “that for at least 40 years, the cultural dimensions of development has been

recognized internationally and in Africa” (Van Graan, 2011). The origins of African Cultural Policies

date back to the colonial period when culture was considered a political tool for combating

colonialism and the perpetuation of European culture on African societies (Kovacs, 2009). At that

time African artists and intellectuals, political groups, and liberalization movements utilized culture as

a way of advancing Pan-Africanism during the independence movement era (Diouf, 2002). In 1969, a

Pan African Cultural Manifesto was adopted by the participants of the Symposium of the Pan-African

Cultural Festival in Algiers. This manifesto would become a pioneer framework for culture and

development, and would inform the formulation of a series of basic principles underpinning the

construction of a vision of post-colonial Africa.

To further utilize the role of culture in development, the World Decade for Culture Development was

initiated by UNESCO in January 1988 spanning the period 1988 – 1997 where more than 1200

projects were launched; the outcomes of which were a number of new conventions, treaties,

agreements and charters that were developed and endorsed globally (Kapwepwe, 2011). This included

a series of consultations launched by the then OAU and UNESCO to address the problems associated

with promoting cultural industries in Africa7. The consultations led to the adoption of the Dakar Plan

of Action for the Development of Cultural Industries at the OAU Summit in 19928. Due to the rapid

changes that occurred in the cultural sphere under the impact of globalization and the rapid

advancement of information and communication technologies, in 2005, the AU Conference of

Ministers of Culture decided to revise and update the Dakar Plan of Action (1992). Thus at the first

session of AU Ministers of Culture in 2005, the Nairobi Plan of Action for Cultural and Creative

Industries (NPoA) was embraced. The plan was once again revised to take into consideration ongoing

and emerging issues in culture and this revised plan was re-adopted by the African Union ministers of

culture in Algiers in October 2008.

The fundamental objectives of the plan included tapping into the vast economic and social potential of

African cultural and creative resources in order to bring about tangible improvement in the living

standards of African artists and contribute to achieving the objectives set out in the MDGs. This was

to be done under three objectives classified as economic, social and political development. It was

envisaged that the NPoA would build on existing frameworks and encourage the development of new

approaches by tapping into available as well as potential internal and external cultural resources. To

do this, the Plan lists 11 priority areas supported by objectives, strategies, and recommended actions

(See: Appendix 1 for a list of priority areas) 9.

7

The Organization of African Unity (OAU) was established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, on signature of

the OAU Charter by representatives of 32 governments. A further 21 states have joined over the years to

constitute 53rd members by May 1994. In July 2000, to replace the OAU, the Assembly of Heads of State and

Government of the OAU, adopted the Constitutive Act of the African Union. The Constitutive Act entered into

force on 26 May 2001 and all 53 previous member states of the OAU are members of the AU. The new state of

South Sudan became the 54th member state when it was officially admitted on 15 August 2011.

8

It is important to note that all frameworks adopted by the OAU and later the AU was done by all member

states as at the time of their formation.

9

For more on the plan outline, see: http://www.arterialnetwork.org/uploads/2011/08/Nairobi_Plan_of_Action_2008.pdf

8

�Unlike the MDGs which have a clear deadline, the NPoA speaks in terms of phases with no defined

timeframe. These 3 phases which are to guide the sequence of implementation are: Phase 1 Advocacy, sensitivity and laying foundation; Phase 2 - Promoting cultural industries as a key

contributor to sustainable development of African countries, and Phase 3 - Ensuring the

competitiveness of cultural industries. In addition, it adds a plan for “Monitoring and Evaluation”

which recommends mechanisms and parameters for assessing the effectiveness of the policies that

stress the importance of the involvement of stakeholders at the grassroots level.

A summarization of the plan shows that through cultural initiatives, it encourages regional and

national political consensus, advocates sustainable development strategies, and promotes policies that

open up access to global market opportunities for Africans. Importantly, the NPoA remains rooted in

both global and continental dynamics, taking into consideration the importance of the African identity

and authenticity, and at the same time respecting its cultural diversity. The NPoA takes a democratic

and inclusive approach to development by stressing the importance of utilizing the diversity of

African creativity, and also by underlining the need to enlarge participation in cultural efforts beyond

educated elites to all groups of the population especially women and youth (Kovacs, 2009). This

policy of inclusion makes ‘the people’ its point of departure and recognizes the need for people to

work differently and have the ability to make choices that impact positively on their lives. With

regards to measuring these contributions, the abstract nature of culture subjects its impact to

evaluation difficulties, as a result, unlike the MDGs the NPoA does not set numeric indicators for

measurement, but leaves it open to contextual interpretations.

Even as it is, the NPoA which is a phased framework for development, that is supposedly bottoms-up

and participatory in its approach, suffers from some weaknesses. One such weakness is the delinking

of the policy declarations from the means for implementation. Rwagweri (2011) draws attention to

the lack of concrete effort to promote and implement the plan, noting the absence of an inbuilt

mechanism of self-perpetuation. Without an inbuilt mechanism of it own tracking like time-bound

targets or reporting schedules, which would have been helpful to in pushing for action and measuring

progress, it is difficult to track, monitor and ultimately implement the plan. Furthermore, the lack of

specific time-frames for achievement of results may explain lengthy delays in the implementation of

the plan.

Beyond this, at an institutional level, the AU may lack the force of will to compel member states to

implement its programmes of action. Therefore in the absence of these checks on compliance,

governments are not driven to accelerate the pace of implementation. Hence, like many policy

statements in the past, the NPoA has not gathered the much-needed momentum required for any

tangible results to be seen, and as a result remains a good idea only in theory. This is further marred

by a weak system of managing information on the sector in Africa.In addition, much of the

responsibility for capacity building, the strengthening of networks and the creation of platforms for

sharing ideas is left in the hands of pan-African, regional and member state authorities. The plan does

not explicitly recognize the crucial role of civil society who can succeed where public sector agencies

fail to move urgently.

The question remains, could this be another African agreement or treaty with a list of wide range of

ideas with varying degrees of relevance, feasibility and urgency that cannot be implemented? How

useful is the NPoA to ensuring the integration of culture in post-2015 sustainable development

agenda? What can be done to ensure that the NPoA does not fall into the “wheel of reinvention rather

than forward motion” (Kapwepwe, 2011)?

Recommendation

Moving beyond the role of pan-African and regional institutions in guiding the implementation of the

plan, civil society and cultural practitioners can use the plan to develop projects and programmes that

are inline with the many conventions the plan is rooted in. The plan creates a platform for sharing

9

�information on the relevance of culture in a post-2015 development agenda with local, national and

international social actors. By engaging civil society as active stakeholders vested in the

implementation of the plan, they can once again start conversations with policy-makers to raise

awareness for the African creative economy and engage in local and international affairs about

inclusive economic and social development.

With the growing recognition that African policy makers are not fulfilling the commitments they

made to ensure the implementation of the plan, it is up to the civil society to engage government to

actualize the treaties by actively engaging creative practitioners, artist and cultural workers in the

implementation of the plan. It is not for civil society or cultural practitioners to engage government in

new arguments, but to consider the broad priority areas and recommendations of the plan and engage

(through activism) governments in directional steps that lead them to take action. These engagements

could be in the form of the rethinking and generation of creativity from within Africa that will benefit

the African creative economy.

There is no clear cost-benefit analysis of the NPoA i.e. no mention is made of the scope or cost of any

of the proposed initiatives or recommendation. As funding and financing remain a challenge within

the sector, more focus needs to be given to the establishment of a financial mechanism for both

mitigation and reduction of cultural sector risk as well as promoting the trade of goods and services.

Linking cultural policy, African markets and aesthetics with a strong normative objective remains a

priority for the NPoA.

Conclusion

The inclusion of culture in Africa’s post-2015 development agenda is crucial for Africa given the

global uptake of the potential contributions of culture to policy which can lead to normative action.

Given the challenges Africa faces, and its performance in current development frameworks, the

starting point for Africa cannot be its economic growth, but rather its peoples. I used the logic of a

rights-based approach imbued with the values of culture and cultural diversity (such as those

enunciated in the NPoA) to show that normative action towards development is better driven, if there

is localized ownership and leadership.

This papers preoccupation with NPoA demonstrates its appreciation of and commitment to a postMDG era, noting that it is not yet time to set aside the plan given the unexplored benefits of culture in

the development process of the continent. Although it has been difficult to identify practical

programmes implementing the components of the plan, the NPoA provides a good set of arguments to

further engage policy-makers in the factual convergence of culture and development policies which

has received little attention so far.

In Africa, looking forward - rather than simply embracing the solutions offered based on experiences

elsewhere - we need to be rigorous in defining our priorities in order to determine how culture-led

strategies fit in with these priorities that we set - The Nairobi Plan of Action is one step in this

direction. I must mention at this point that insofar as cultural and creative industries remain the

backbone of the plan, they can be obstacles to sustainable development if these industries are a

reflection of unequal global markets forces and access to resources.

The question for Africa remains - how to adopt best practices to a diversity of cultural contexts as the

“developing” points for each country are different and how do we engage key stakeholder like civil

society, artist and creative actors to rethink strategies that can activate creative resources that

strengthen the Creative Economy?

We cannot continue to rely on the so-called best practices prevalent in mainstream discourse and this

breakaway can only be done through understanding the complexity of the relationship between

individual agencies and cultural continuity in institutional change. Working on gradual improvement

10

�of small institution practices may help to see how development frameworks are promoted or held

back and how global standards can be adapted to the local context.

REFERENCE

11

�African Union (2014) Common African Position on Post-2015 Development Agenda. Available http://www.uneca.org/sites/default/files/uploaded-documents/Macroeconomy/post2015/cappost2015_en.pdf

African Union (2008) Plan of Action on the Cultural and Creative Industries in Africa. Available online at http://www.arterialnetwork.org/uploads/2011/08/Nairobi_Plan_of_Action-_2008.pdf

De Beukelaer C. D (2014) “The UNESCO/UNDP 2013 Creative Economy Report: Perks and Perils

of an Evolving Agenda.” The Journal of Arts Management, Law and Society 44: 90 – 100.

Diouf, M. (2002) Working Document, Consultative Meeting on the Preparation of the Pan-African

Cultural Congress, Nairobi, Kenya, 16-18 December 2002.

D’Almeida, F. (2009) Culture and Development: A response to the challenges of the

future.http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/FIELD/Brussels/pdf/Culture_and_devel

opment_series.pdf Accessed 5 October 2013.

Easterly, W. (2009) How the Millennium Development Goals are Unfair to Africa. World

Development Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 26-35

Graan, V, M. (2011) Culture and Development. In Contemporary Arts and Cultural Discourse:

African Perspectives. Arterial Network, Cape Town

Hesmondhaigh, D (2007) The Cultural Industries, Sage.

Howkins, John (2001), The Creative Economy, Penguin Books.

IFACCA, IFCCD & Culture 21 (2014) “Culture as a Goal: In the post-2015 Development Agenda.”

Available at http://www.interarts.net/descargas/interarts1694.pdf

Kapwepwe, M. (2011) Cultural and Creative Industries in Africa, Suggestions for civil society

response. In Contemporary Arts and Cultural Discourse: African Perspectives. Arterial Network,

Cape Town

Kovacs, M. (2009) Cultural Policies

in Africa: Compendium of reference documents.

http://www.aecid.es/galerias/programas/Acerca/descargas/Cuadernos_Acerca_ingles.pdf

last

Accessed 7 September 2013

Mukanga-Majachani (2011) The African Union and its Plan of Action on Culturaal Industries: ally or

obstacle to the African creative sector? Presented at the 2011 African Creative Economy Conference

in Dakar, Senegal

Njoh, A. J. (2006) Tradition, Culture and Development in Africa: Historical Lessons for Modern

Development. Ashgate Publishing.

PriceWaterHouseCooper. (2008) Global Entertainment and Media Market Outlook: 2008 - 2012

http://www.swissmediatool.ch/_files/researchDB/210.pdf Last accessed 2 September 2010

Throsby, D. (2002) From Cultural to Creative Industries:the Specific Characteristics of the Creative

Industries. Available online at jec.culture.fr/Throsby.doc

Ruigrok, I. (2009) The missing dimensions of the Millennium Development Goals: culture and local

governments.

Available

on-line

at

12

�http://agenda21culture.net/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=85%3Areport-2culture-local-governments-and-millennium-development-goals&catid=58&Itemid=89&lang=en

UNESCO & UNDP (2013) Creative Economy Report: Widening Local Development Pathways.

Available at http://www.unesco.org/culture/pdf/creative-economy-report-2013.pdf

Vandemoortele, J. (2009) The MDG Conundrum: Meeting the Targets without Missing the Point,

Development Policy Review, Vol. 27, No. 4, pp. 355 -71

Vandemoortele, J. (2012) Advancing the UN development agenda post-2015: some practical

suggestions.

http://www.wssinfo.org/fileadmin/user_upload/resources/DESA---post-2015-paper--Vandemoortele.pdf Last Accessed 29 August 2013

Waage, R., Banerji, R., Campbell, O., Chirwa, E., Collender, G., Dieltiens, V…Unterhalter, E. (2010)

The Millennium Development Goals: a cross-sectoral analysis and principles for goal setting after

2015. Available on-line from http://eprints.soas.ac.uk/16774/1/S0140673610611968.pdf Accessed 21

August 2013

Puko, N, K. and Whitman, J. (2011) The millennium Development Goals and Development after

2015. The World Quarterly, Vol 32, No. 1, pp 181 -198

Appendix 1

Key Priority Area of the Nairobi Plan of Action

a. Reinforcing African ownership and leadership of the processes and strategies to be

developed as the frameworks of this Plan of Action;

b. Addressing the needs for statistical data on cultural and creative industries;

c. Institutional and legislative capacity building at the National, Regional and

Continental levels;

d. Building the Capacity of Stakeholders;

e. Facilitating Access to Markets and Audience;

f. Improving infrastructure for the cultural and creative industries;

g. Improving the working conditions of artists, creators, actors and operators in Africa;

h. Targeting and Empowering women, vulnerable groups, including artists and creators

with disabilities, refugees, and poor communities;

i. Protecting African Intellectual property Rights and Labels;

j. Preservation of African tangible and intangible cultural heritage and indigenous

knowledge; Mobilization of resources for sustainable implementation of the Plan of

Action for the development of Cultural and creative industries in Africa.

13

�