English Language and Linguistics, page 1 of 7. © The Author(s), 2023. Published by

Cambridge University Press

Review

doi:10.1017/S1360674322000430

Rodney Huddleston, Geoffrey K. Pullum and Brett Reynolds, A student’s introduction

to English grammar, 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022. Pp. xx +

400. ISBN 9781316514641 (hb), 9781009088015 (pb).

Reviewed by Bas Aarts , University College London

The second edition of this textbook (henceforth SIEG2) was published twenty years after the

publication of the Cambridge Grammarof the English Language (CGEL) on which it is based,

and seventeen years after the first edition (SIEG1). The latter has acted as an introduction to the

larger work for many generations of students. I use the book on a Master’s course in English

linguistics. Quite a few students find it challenging, not only because many of its analyses are

different from what they have been taught on previous undergraduate degrees, but also because

the book’s account of certain areas of English grammar can be quite complex.

How is the second edition different? SIEG2 is published in a new, much more attractive

format and layout. It has an additional chapter on adjuncts, and some of the material in

SIEG1 has been moved online, specifically the chapter on morphology and the

glossary. The text of the other chapters is largely the same, but has been updated.

There are quite a few further notable changes, some of which I will discuss below,

concentrating on exposition, terminology and the online support materials.

Exposition

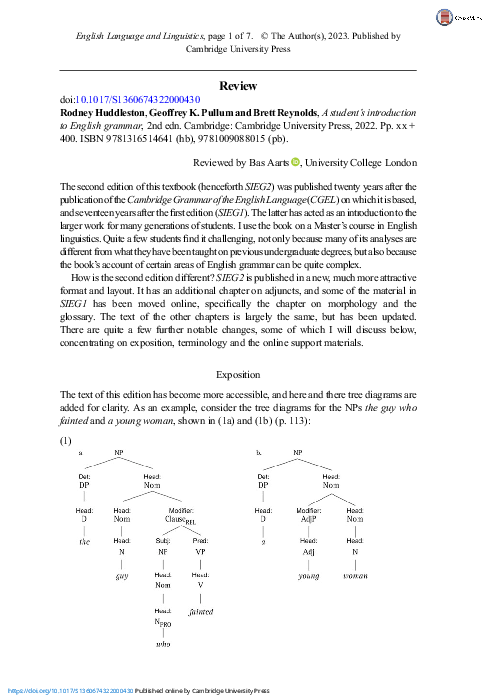

The text of this edition has become more accessible, and here and there tree diagrams are

added for clarity. As an example, consider the tree diagrams for the NPs the guy who

fainted and a young woman, shown in (1a) and (1b) (p. 113):

(1)

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674322000430 Published online by Cambridge University Press

�2

E NG L I S H LA N GU A GE A ND L I N GU I S T I C S

As in CGEL, the trees in SIEG2 show both form and function labels. However, unlike

in CGEL, they make explicit that a single word on its own can constitute a phrase. In Aarts

(2004: 370) I criticised CGEL for representing a single determinative as just ‘D’ in tree

diagrams, and asked why it is not a determinative phrase (DP) as well. That was

unjustified, because I didn’t spot an easy-to-miss comment on page 329 in CGEL: ‘We

simplify the tree diagrams by omitting the higher-level constituents if they consist of

just a head element.’ The fully explicit trees in SIEG2 avoid this potential

misunderstanding. However, confusion may still occur for some readers over the label

‘DP’ which is also used in generative frameworks in an entirely different way; ‘DetvP’

would perhaps have been better.

Avery welcome new chapter on adjuncts (which had been circulating as a pdf for quite

a few years) has been added. The chapters in SIEG2 now align with CGEL.

Terminology

In this section I will discuss some issues concerning the use of terminology in SIEG2.

Head

In SIEG1 the concept of ‘head’ is defined as follows: ‘The head of a phrase is, roughly,

the most important element in the phrase, the one that defines what sort of phrase it is’

(p. 13). This is replaced in SIEG2 by the following: ‘A phrase in our terms is a

constituent … with a word functioning as head and some number (zero or more) of

dependents’ (p. 23, emphasis in original). This is a more useful definition, but note

that neither definition caters for the VP disturbs me in the tree diagram in (2) which

functions as the head of the VP that immediately dominates it, which in turn

functions as predicate.

(2)

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674322000430 Published online by Cambridge University Press

�REVIEW

3

Here the function of head is realised by a phrase, not by a word. (The same point

applies to other phrase structures, for example to noun phrases, where ‘Nom’

functions as head; see the tree diagram of a young woman in (1b).) Incidentally,

notice that in (2) the extraposed subject clause that he was acquitted is treated as

a complement, positioned within the higher Predicate VP. The reader may wonder

what this clause is a complement of, given that complements are defined in an

earlier chapter as ‘an integral and sometimes obligatory part of a phrase that the

specific lexical head permits or requires’ (p. 23). The structural configuration in

the tree in (2) (VP-adjunction) does not make clear which lexical head licenses

this complement. One might say that the extraposed clause is ‘indirectly licensed’

by the verb disturb, but this would need to be made explicit, as the tree does not

represent the usual head-complement configuration. CGEL (p. 1403) states that

‘[a]n extraposed subject, like a displaced subject, is not a kind of subject, but an

element that is related to a dummy subject’, and it refers to ‘the extraposed

subject position’ as being ‘at the end of the matrix clause’, without further

specification. This is unhelpful, because it does not tell us exactly where the

extraposed clause is placed. As the tree in (2) shows, in SIEG2 we have more

detail than in CGEL, but I would have liked to see some justification for

regarding the extraposed clause as a complement, and for positioning it within the

higher VP. The latter could easily have been achieved with a standard VP

constituency test: I said that it disturbs me that he was acquitted and [VP disturb

me that he was acquitted] it did.

In SIEG1 the coordination Jennifer is a great teacher and her students really respect

her is represented as in (3):

(3)

In SIEG2 the structure has been revised to look like (4) (p. 342):

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674322000430 Published online by Cambridge University Press

�4

E NG L I S H LA N GU A GE A ND L I N GU I S T I C S

(4)

The earlier structure was problematic (not least because two constituents carry the

identical label ‘Coordinate2’), but the newly proposed structure is also not without

problems, because the text reads: ‘The coordinates … have equal syntactic status: each

makes the same sort of contribution to the whole thing.’ But this is not what the tree

diagram shows, since the clause and her students really respect her has a different

structure: it is introduced by a coordinator which grammatically functions as marker.

Notice also the label ‘coordination’ at the top of the diagram, which was not explained

in SIEG1. In the new edition the authors write: ‘We’re essentially using the term

coordination as the name of a syntactic category to which all coordinations belong – a

category that is neither lexical nor phrasal’ (p. 342). But this does not help much,

because the exact syntactic nature of this category is still left unexplained. We have one

further kind of unit in CGEL and both editions of SIEG that is neither lexical nor

phrasal, and this is ‘Nom’ (N-bar) inside noun phrases, but clearly ‘coordination’ is not

on a par with Nom.

Finite(ness)

The discussion of the notion of finiteness has been moved from chapter 3 in SIEG1

(‘Verbs, tense, aspect and mood’) to chapter 14 in SIEG2 (‘Non-finite clauses’).

This means that it is not until readers get to page 311 of the book that this

important grammatical concept is explained. In line with recent work in linguistics,

CGEL (p. 88) regards finiteness as a property of clauses, rather than of verbs,

because the traditional definition ‘doesn’t work at all for present-day English’

(SIEG2: 311; see also e.g. Nikolaeva 2007). In CGEL and SIEG1/2 finiteness is a

property of clauses that contain a primary verb form, and of imperative and

subjunctive clauses. Dropping the traditional definition of ‘finite clause’ as ‘a

clause headed by a finite verb’ entails that CGEL and SIEG1/2 allow for tensed

non-finite clauses, as in I was happy to have met him, where the underlined clause

contains a secondary perfect tense. CGEL and SIEG1/2 also allow for finite clauses

to lack a tensed verb, as in subjunctive and imperative clauses. While all this

makes sense to those who are well versed in English grammar, it is hard for

students to understand, especially if they have previously been taught the

traditional definition of finiteness.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674322000430 Published online by Cambridge University Press

�REVIEW

5

Particle

The label ‘particle’ is used in almost all grammars as a word class label, so students can be

forgiven for misunderstanding this notion in SIEG2, where it is used as a grammatical

function label, so that in the sentence He switched the light off, the verb SWITCH takes

two internal complements, namely the NP the light, which functions as direct object,

and the prepositional phrase off (headed by an intransitive preposition), which

functions as particle. The discussion in SIEG2 is an improvement on SIEG1, because

the fact that ‘particle’ is a function label is more clearly signposted, but I believe

that this will still cause a great deal of confusion, especially when we read that

‘[d]erivatively, we can call a word a particle if it has the POTENTIAL to function as a

particle complement’ (p. 199, emphasis in original). I’m really not sure what the

authors have in mind here. None of this is helped by the fact that the chapter in which

the discussion of ‘particle’ occurs is entitled ‘Prepositions and particles’, which mixes

form and function labels.

Catenative verb

Catenative verbs have played a role in English linguistics at least since Palmer (1965/

1987) and Huddleston’s earlier work (1984). These verbs also play a major role in

CGEL and SIEG1. In SIEG2, the label ‘catenative verb’ is dropped. I have mixed

feelings about this. On the one hand, I argued in Aarts (2004: 371) that it is

superfluous, and can be confusing for students. I stand by that view, but removing the

concept from this textbook will pose problems for students who wish to study this area

of grammar in greater detail by consulting CGEL. They will find that the CGEL

treatment of verbs occurring in this construction uses very different terminology from

SIEG2 (apart from ‘catenative verb’, CGEL also has the labels ‘catenative

complement’, ‘catenative-auxiliary analysis’ and ‘catenative construction’ – the latter

occurs in various guises: simple/complex/oblique/for).1

Transparent verb

This label is used in the chapter on non-finite clauses (p. 325) to designate raising verbs, as

in Al appeared to like Ed. The authors explain that in this sentence ‘[i]t’s as if the

intervening verb were merely some kind of modifier – as if it were transparent to the

subject–verb semantic relation. The meaning … is very close to that of Al apparently

liked Ed, where the adverb apparently modifies the like VP’ (p. 325). I think that quite

a few students will be puzzled by this, not least because it does not follow from the

fact that we can paraphrase this sentence in this way that the ‘transparent verb’ is

syntactically like a modifier. Moreover, with a nod to Occam, the new terminology is

unwarranted, because SIEG2 retains the label ‘raised subject’, so this kind of verb

1

‘Catenative complement’ appears in the online document ‘A complete taxonomy of CGEL functions’, even though

the notion is not used in SIEG2.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674322000430 Published online by Cambridge University Press

�6

E NG L I S H LA N GU A GE A ND L I N GU I S T I C S

might as well have kept the label ‘raising verb’, as in CGEL and SIEG1. And here again, as

with ‘catenative verb’, CGEL does not use the label ‘transparent verb’, so it will again

confuse students who wish to ‘level up’ to the larger work.

Online support materials

SIEG2 offers students and instructors copious online support materials (cambridge.org/

SIEG2). For students there are pdfs with chapter summaries, supplemental tree

diagrams for chapters 3–5, a glossary, lists of determinatives, prepositions and

grammatical functions, a morphology appendix (formerly a chapter in SIEG1), and a

document with further reading suggestions. For instructors (who need to apply for

access), there are solutions to all the exercises, a ‘test bank’ for all the chapters in the

form of multiple-choice exercises, and files for all figures in the book, made available

in jpeg and ppt formats.

These materials are immensely valuable, though to my mind some of them should

have remained inside the book, e.g. the glossary. It is irritating for readers to have to go

online to check the meaning of a particular concept, when they could have just turned

to the end of the book.

Although the ‘Further Reading’ document is very useful indeed, it would have been

even more valuable had it been more comprehensive. As things stand, what we get is

‘a miscellaneous assembly of things’, but ‘[s]pace limitations made it quite impossible

for us to provide in print the kind of full bibliographical referencing that our book

would have in an ideal world, and the sheer bulk of the enormous linguistics literature

pertaining to English makes it impossible for us to be complete here either’ (p. 1). But

this is odd, given that the document is posted online, where there aren’t any space

limitations.

The document with fifty-two ‘supplemental tree diagrams’ clarifies the analyses

adopted in the book. This will be enormously helpful to students and instructors too.

Intriguingly, these tree diagrams also offer an exegesis of many of the analyses in

CGEL, which has only forty tree diagrams, so that in many cases SIEG2 is more

explicit in visualising the analyses of particular constructions than the larger grammar.

Maybe it’s also time for a second edition of CGEL.

Conclusion

In many ways this second edition is a much-needed improvement on the first: its writing is

more accessible, there are more exercises, and the analyses proposed have been made

much more explicit by using more tree diagrams, both in the text and in the online pdf.

Unfortunately, not all the changes are to be welcomed. This is true especially with

regard to some of the new terminology used in the book which is not in sync with

CGEL, while some other terminology has been dropped, making ‘levelling up’ to

CGEL harder. The book is designed for a one-semester course, but it will be

challenging for instructors to cover all the chapters within that time period. Two

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674322000430 Published online by Cambridge University Press

�REVIEW

7

semesters are more appropriate for teaching the material effectively and at a more

manageable pace.

Reviewer’s address:

Department of English Language and Literature

University College London

Gower Street

London WC1E 6BT

United Kingdom

b.aarts@ucl.ac.uk

References

Aarts, Bas. 2004. Grammatici certant. Review Article of Rodney Huddleston and Geoffrey Pullum

(2002) The Cambridge grammar of the English language. Journal of Linguistics 40(2), 1–18.

Huddleston, Rodney. 1984. Introduction to the grammar of English. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press.

Huddleston, Rodney & Geoffrey Pullum et al. 2002. Cambridge grammarof the English language.

Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nikolaeva, Irina. 2007. Introduction. In Irina Nikolaeva (ed.), Finiteness: Theoretical and

empirical foundations, 1–19. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Palmer, Frank. 1965/1987. The English verb. London: Longman.

(Received 11 November 2022)

https://doi.org/10.1017/S1360674322000430 Published online by Cambridge University Press

�

Bas Aarts

Bas Aarts