Foreword by Jason Bailey

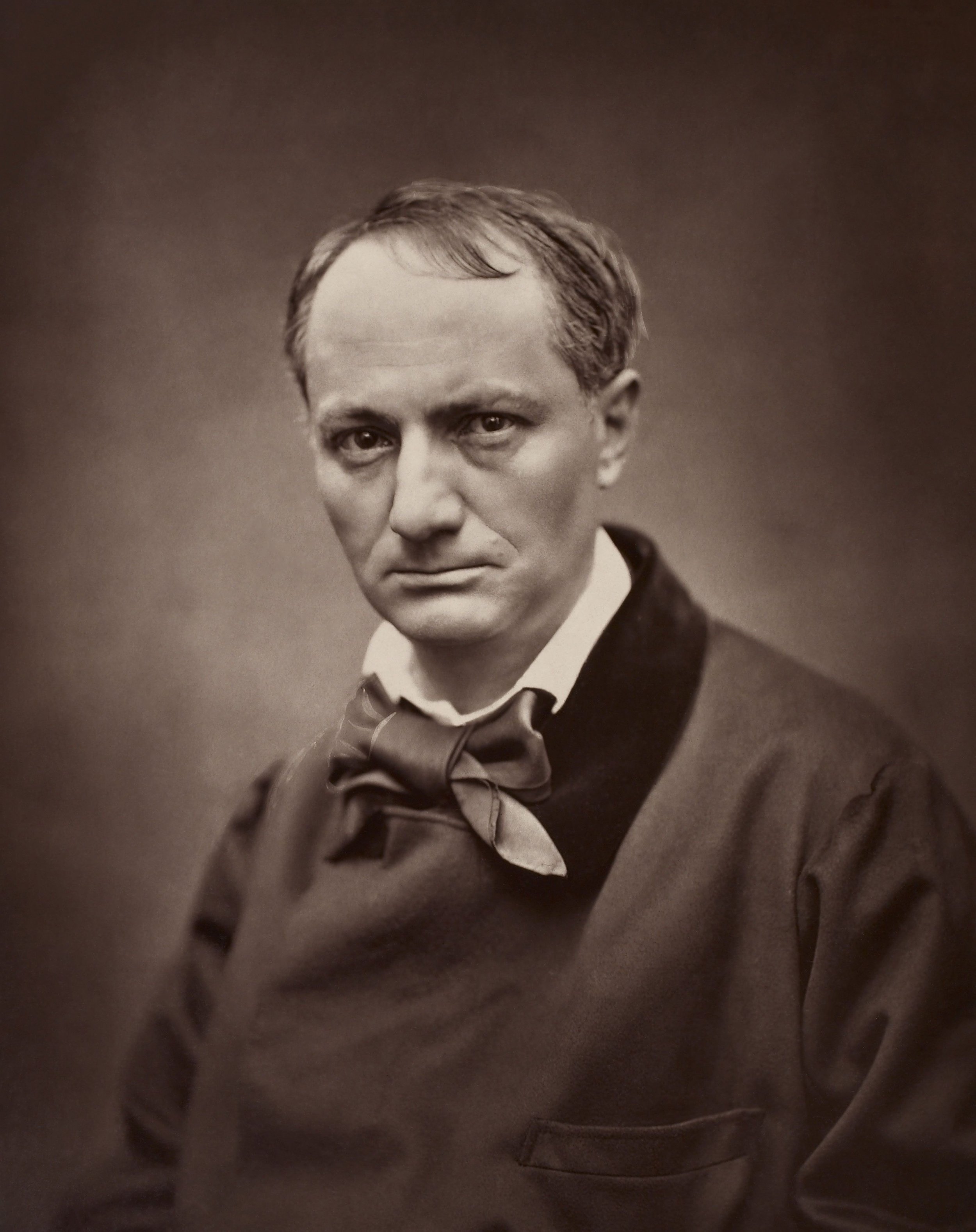

It may be hard to believe, but there was a time in the not too distant past when photography was viewed with as much prejudice and suspicion by the the art world as digital art is today. Many believed that because photography involved chemicals and machinery instead of the “human hand and spirit,” it could not be considered on par with drawing and painting. Instead, photography was seen as being closer to the fabrics being mass produced by machines in the mills than it was to the fine arts. The influential French poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire even worried that photography would erode the very foundation of the fine arts:

As the photographic industry was the refuge of every would-be painter, every painter too ill-endowed or too lazy to complete his studies, this universal infatuation bore not only the mark of a blindness, an imbecility, but had also the air of a vengeance. I do not believe, or at least I do not wish to believe, in the absolute success of such a brutish conspiracy, in which, as in all others, one finds both fools and knaves; but I am convinced that the ill-applied developments of photography, like all other purely material developments of progress, have contributed much to the impoverishment of the French artistic genius, which is already so scarce.

Just a few years after making this bold anti-photography statement Baudelaire’s stance on photography must have softened a bit as he chose to sit for the photographer Étienne Carjat for the portrait shown below. It would, however, take more than one hundred years before a popular market for photography as fine art would develop.

Étienne Carjat, Charles Baudelaire - 1863

In the early 1950s, photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson, often referred to with reverence as “the father of photojournalism,” published his book The Decisive Moment. In it, he differentiates photography from painting by pointing out that painting can be slowly worked over time in contrast to the photographer, who is capturing a precise moment which will never be reproduced or occur in the same way again. As an extension of this ethos, Cartier-Bresson was against manipulation and cropping of photographs in the darkroom. The art of photography was in the framing of unique events in real time through the camera’s view finder, not in the manipulation of chemicals and machinery.

Henri Cartier-Bresson, Behind the Gare Saint-Lazare - 1932

As Cartier-Bresson shared in a 1957 interview in The Washington Post:

Photography is not like painting. There is a creative fraction of a second when you are taking a picture. Your eye must see a composition or an expression that life itself offers you, and you must know with intuition when to click the camera.

That is the moment the photographer is creative. Oop! The Moment! Once you miss it, it is gone forever.

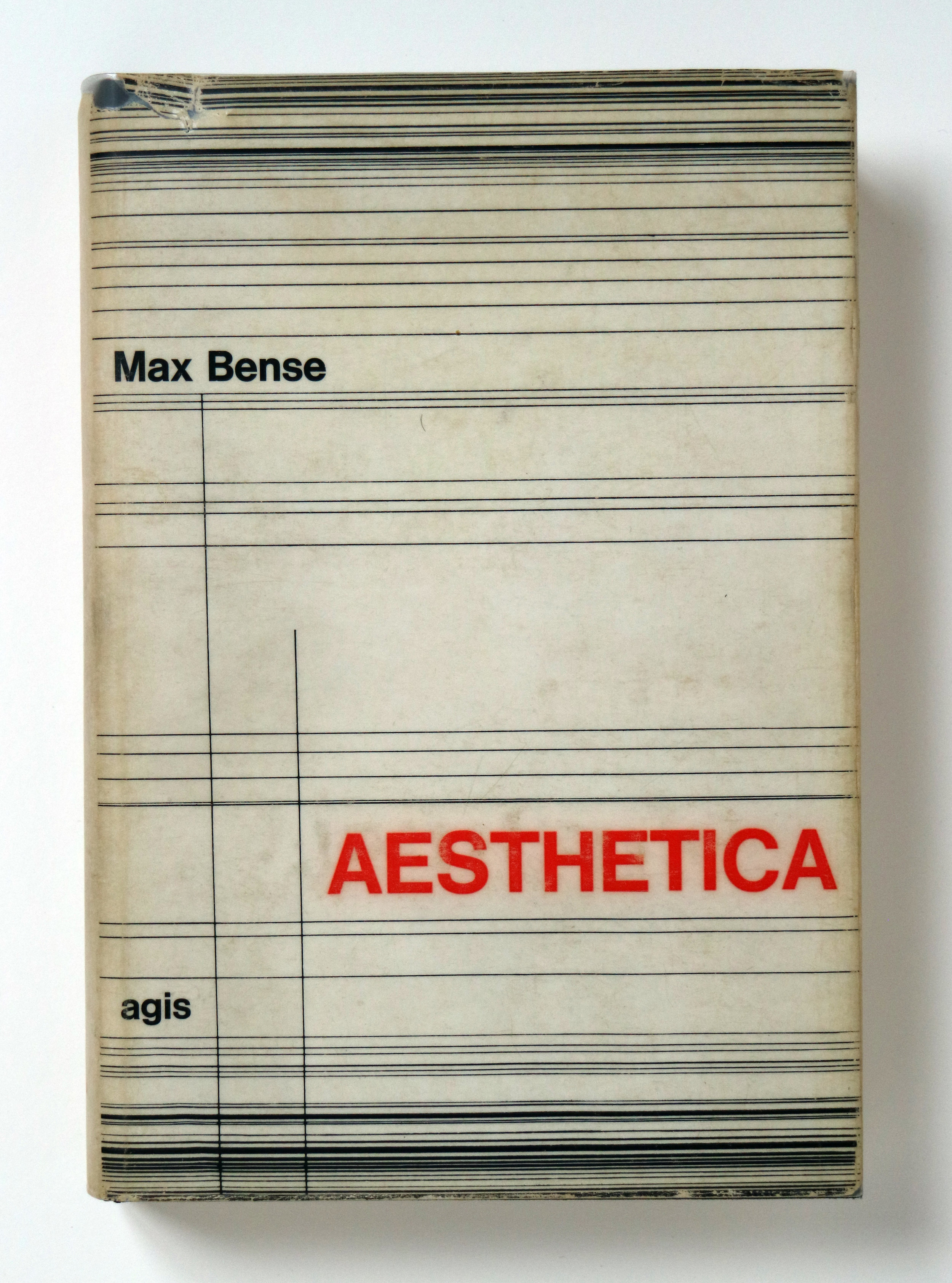

Against this popular conception of photography as means of faithfully capturing fleeting moments of reality, and decades before a popular market for photography as fine art would emerge, a group of radical photographers posed a direct challenge to Cartier-Bresson’s notion of the “decisive moment.” They created non-representational photographs that could be mechanically reproduced through a series of algorithmic actions. Rather than capture moments of reality, these photographers were producing their own realities or “aesthetic states” through mechanical and chemical manipulation. Though they owed a debt to concrete art with its strong emphasis on geometrical abstraction, these photographers were more influenced by media theory, cybernetics, and semiotics than the traditional art history and art theory of their time. They borrowed the term “generative” from German semiotician Max Bense’s book, Generative Aesthetics, to describe their approach, eventually settling in on “generative photography”. The generative photographers developed repeatable programs for photographic image making which predated and then evolved side by side with early generative computer-based art.

While generative photographers like Gottfried Jäger, Herbert W. Franke, and Hein Gravenhorst may not be household names yet, they should be. I believe generative art is the most important art of our generation as it makes the digital revolution visible and best reflects all that separates us from those who came before us. First through photography and then through computers, the ideas and work of these artists form the foundations for all of generative art.

Porträt Gottfried Jäger, Paris photo - 2017 - photographer unknown

One reason you may not know of these great pioneers is that although they were prolific and have written hefty volumes of theory explaining their approach, few of these books have been translated into English. We are seeing renewed interest in this work, with several generative photographers having been shown in the recent exhibition Shape of Light at the Tate Gallery London and in the current show Automat und Mensch at the Kate Vass Galerie in Zurich. I was lucky enough to co-curate the latter show with generative photography expert Georg Bak. It was through Bak that I learned of these pioneers and their important contributions. Bak has had the foresight to interview these important artists while they are still available to shed light on their important work and contributions to the history of generative art.

What follows is the first of several important interviews between Georg Bak and the early pioneers of generative photography. In this interview, Bak speaks with Gottfried Jäger, who is credited with naming the movement “generative photography” and is one of its most important practitioners. We at Artnome are thrilled to feature Bak’s interview with Jäger in English for an audience who may not otherwise learn of his important work and the ideas behind the origins of generative photography and the generative art movement.

Interview with Gottfried Jäger by Georg Bak

Gottfried Jäger presents his pinhole structure 3.8.14 F 2.6, 1967, b/w camera - photograph by Ursel Jäger

Georg Bak (GB): In the exhibition Automat und Mensch, we have curated a show around artificial intelligence within its art historical context. The title of this exhibition refers to a book by Karl Steinbuch from 1961, which you have mentioned to me several times in our numerous conversations. Can you describe to us how you discovered this book in the early 1960s and to what extent it was influential for your artistic practices?

Gottfried Jäger (GJ): This book was recommended to me by Hein Gravenhorst, a longtime friend of mine and fellow artist in generative photography, who brought it to my attention in the mid-1960s. I met Hein for the first time through Manfred Kage, whom I was visiting for an interview in Winnenden near Stuttgart. Gravenhorst and Kage were successfully collaborating in the making of "polychromatic variations." Our first meeting was very fruitful and the beginning of a long-term collaboration which lasted up until now.

Karl Steinbuch: Automat und Mensch. Kybernetische Tatsachen und Hypothesen. Springer Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg-New York, 3. ed., 1965. First ed. in 1961.

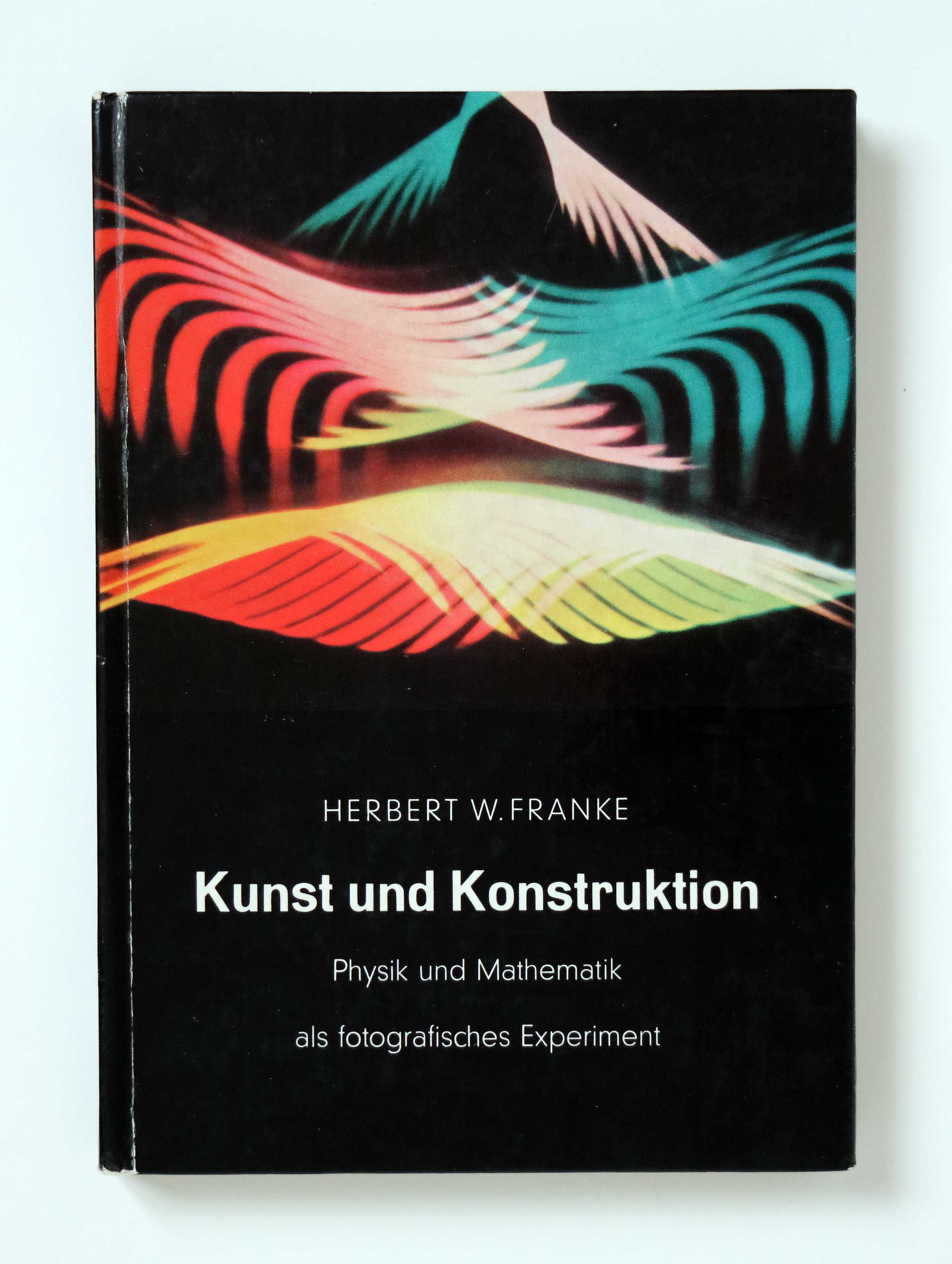

Herbert W. Franke: Kunst und Konstruktion. Physik und Mathematik als fotografisches Experiment. F. Bruckmann Verlag, Munich, 1957

The book Automat und Mensch - Kybernetische Tatsachen und Hypothesen was seminal for my way of thinking. It was written by an engineer, and his language was congruent to mine, both being knowledgeable about new technology in those days. This book got me familiar with the term "information," which helped me to get away from the myth of the "Geistigen" (spiritual) and metaphysics in art. Steinbuch stated:

What we are observing regarding intellectual functions is reception, processing, and transfer of information... It isn't evident or likely at all that you need further requirements than physics in order to explain intellectual functions.

According to this statement, a human brain and a hand weren't necessary anymore for an artistic expression. It could be also a technical apparatus. A camera or a computer were capable of achieving intellectual results. Nowadays these kind of questions have become obsolete and photography is undoubtedly acknowledged as a form of art. But in those days it was not the case, and it had to be legitimized and justified.

GB: Another book that you often talked about is Kunst und Konstruktion by one of the earliest pioneers of computer art, Herbert W. Franke, with whom you are still befriended. How did you meet him and how was your exchange?

GJ: I came across that book at the Bibliothek der Staatlichen Höheren Fachschule für Photographie (State College Library for Photography) in Cologne, where I had studied photography from 1958 to 1960. That little book from 1957 published at F. Bruckmann in Munich instantly woke my interest. It was not only the title and a nice cover of the book, but especially its subtitle, Physik und Mathematik als fotografisches Experiment (Physics and Mathematics as a Photographic Experiment). That was a credo, a program. And nowadays I realize: This approach has led my way throughout my whole career as an artist.

Double page 38/39 from Kunst und Konstruktion: (l.): Herbert W. Franke and Andres Hübner, Pendulum Oscillogram, Contaflex, photographed from a screen; (r.): idem, Verdrillter Gummiring, camera photograph; both photographs not dated (c. 1957)

I began my approach to this completely new and fascinating world through imitation. I was reproducing some of the images that I had discovered in the book - for example, the photograph Verdrillter Gummiring (Twisted Rubber Ring) by Herbert W. Franke and Andreas Hübner. But a few years later in 1966 during my summer vacation at Bodensee, I decided to contact Herbert W. Franke and asked for an appointment ... granted! This was followed by an exciting first meeting in Wolfratshausen near Munich. We became friends and have been cooperating on several occasions. The first results of our cooperation were the exhibition Generative Fotografie in 1968 and the book Apparative Kunst. Vom Kaleidoskop zum Computer, which we had published together in 1973 with DuMont in Cologne and had gained wide international recognition.

Gottfried Jäger: Untitled, Hommage à H. W. F., camera photograph, silver gelatine print, 16 x 10.5 cm, 1958

GB: In 1968 you organized the exhibition Generative Fotografie at Kunsthaus Bielefeld which can be regarded retrospectively as the manifesto of this important art movement. Can you share with us how you came up with this exhibition and what the reaction was within the art scene at that time?

GJ: Let me tell you the whole story. In 1965 I was invited to show my "Lichtgrafiken" (light graphics) at the group show Fotografie '65 in Bruges. I was visiting the show alongside some students of my class at Werkkunstschule Bielefeld. Although the succinct title of the show wouldn't suggest any specific expectations, this exhibition was a counter-reaction to another exhibition taking place at the same time, also in Bruges, an exhibition organized by Karl Pawek in conjunction with the German magazine by Stern,Weltausstellung der Photographie: Was ist der Mensch. While the latter was the "grand opera," our show Fotografie '65 was rather a chamber concert. A sensational realism was countered by a radical formalism. This is how we experienced it on spot and how I later featured it in the article Signale eines neuen Programms at the art magazine Foto-Prisma. Some works that captured my attention were landscape studies by the Belgian artists Yves Auquie and Robert Besard, close-ups by Anton Dries, nudes by the Swiss artist René Mächler, and especially the filigrane "chemigrams" by Pierre Cordier and the elegant "photograms" by Kilian Breier, as well as the "Lichtstrukturen" (light structures) by Roger Humbert. The latter inspired me to organize my own group exhibition with a special focus on the formative potential - concrete as well as constructive - of photography. This was the moment when the idea was born to organize an exhibition titled Generative Fotografie which would take place three years later at Kunsthaus Bielefeld.

Max Bense: Aesthetica. Einführung in die neue Ästhetik. Agis Verlag, Baden-Baden, 1965

It took me a few travels to visit this small circle of artists until I finally spoke about the idea to the former director at Kunsthaus Bielefeld, Joachim von Moltke, in 1967. I presented him my "Lochblendenstrukturen" (pinhole structures) alongside some photographic works by Kilian Breier, Pierre Cordier, and Hein Gravenhorst. Surprisingly, he instantly agreed to make this exhibition happen in January, 1968, and it was to become the last show at the beautiful Kunsthaus Bielefeld. Soon after, the building was torn down and instead the Bielefeld Kunsthalle was built at another place.

For the title of the show, I was inspired by the last chapter of the book Aesthetica by Max Bense. His theories were summarized under the title Projekte generativer Ästhetik. The following sentences were seminal for me:

Generative aesthetics is an aesthetic by creation. It allows a methodical creation of aesthetic states by dissecting the creation in a finite number of specifiable and describable single steps.

So basically it was not about creating "high art," but about generating "aesthetic states." This was a key element for a new discipline in the art. I called up Herbert W. Franke and asked him for his opinion regarding the exhibition title Generative Fotografie, and spontaneously he thought, "It sounds good.”

Generative Fotografie, invitation card for the exhibition at Kunsthaus Bielefeld, 1968, designed by Heinz Baier

The exhibition was quite successful. Local press reacted in a rather positive way. Even such prominent artist colleagues such as Otto Steinert affirmed during a board meeting of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie (German Society for Photography) which took place in the exhibition space of Generative Fotografie. Follow-up exhibitions around this topic took place at Galerie Spektrum in Hannover, in Antwerp, and at other places. The studies class of Kilian Breier from HFBK Hamburg came to visit the show. Among the students was Karl Martin Holzhäuser, a later colleague and friend of mine at Fachhochschule Bielefeld (Bielefeld University of Applied Sciences). But it was only after the manifesto-like book Generative Fotografie from 1975 which I co-published with Holzhäuser and Franke when theory of this art movement became more widespread in the broad public.

Exhibition view of Generative Fotografie at Kunsthaus Bielefeld, 1968; included works by Kilian Breier (l.), Pierre Cordier, Hein Gravenhorst (l.) and Gottfried Jäger (r.; curator); catalogue text by Herbert W. Franke

GB: Could you define what generative photography means and how this term evolved? Looking back in art history from our perspective, wouldn't it be almost evident that generative photography was the origin or source of digital photography?

GJ: I have already mentioned the definition of generative aesthetics by Max Bense. We discovered therein a new artistic approach in the handling of photographic techniques. Nowadays the term is widely acknowledged and can be retrospectively seen as an early artistic form from the mid-1960s, which was exploring for the first time the synthesis between light images and data images, an interplay between cameras and computers. The imagery was on an abstract level, without any reference to objects or symbolic signs. It was all about generating aesthetic states, where natural analog media (light, camera, light-sensitive support) and mathematical instruments (number, computer, program) were interacting.

But I have to clarify that in the early days, generative photography was not made with computers. They were primarily light images made through experimental photography. But we have connected the techniques with the methods of computers, meaning numeric programs. Our method was also a rejection of the single image and the "decisive moment" (Cartier-Bresson) towards a serial and logically reproducible work series.

Ursel and Gottfried Jäger with “pinhole structures” (Lochblendenstrukturen), 1967, from the exhibition Generative Fotografie; photograph by Günter Rudolf, 1968

My first definition of generative photography reads as follows:

"Generating aesthetic structures on the basis of predefined programs which are processed through photo-chemical, photo-optical, or photo-technical operations in order to achieve an ideal and functional connection within all involved elements that form the composition of the aesthetic structure."

This was the opposite to "subjective photography" (Steinert) or "totale photographie" (Pawek). It was an alternative to these very dominant positions in photography at the time.

Insofar I wouldn't dare to say that "generative photography" was the origin of digital photography. Digital photography is a general expression for a chip-based optical image technique of our time. The origin goes back to Steven Sasson and his patent at Kodak in Rochester in 1975.

Herbert W. Franke (l.) and Gottfried Jäger (r.) at the exhibition Wege zur Computerkunst, Kunsthalle Bielefeld, 1971; photograph by Ursel Jäger

GB: In the 1960s there was an international computer art movement with the New Tendencies in Zagreb and the extensive exhibition Cybernetic Serendipity at the ICA in London in 1968. Was there any awareness for this rather marginal movement at that time? Were there any connections to, for example, the ZERO or the Op-Art movement?

GJ: We were active participants of these movements. We contributed with lectures and publications as well as presentation of our artworks in exhibitions. So for example, Gravenhorst and myself were exhibiting in Zagreb, and we also took part at the symposium. Kage and Breier were both part of the ZERO group. Nevertheless, the art establishment didn't truly take notice.

Regarding the acknowledgement of our work (generative photography) as a legitimate form of art, we had to fight on two levels against the perception of "photography as illegitimate art" (Bourdieu, 1983). It was only in 1984 when photographs were being accepted legally as works of visual art according to German copyright law. On the other hand there was a general skepticism whether computers could be regarded as an artistic medium. The rather cold outputs of computer art couldn't withhold the traditional conception of high art. So as photographers, we were basically not regarded as real artists, and as generative photographers, we were not regarded as real photographers.

GB: Was there a market for computer art? Who were the collectors and gallerists dealing with that type of art?

GJ: In the 1960s, there didn't exist a significant market for generative art. For photography it was Käthe Schroeder who opened Galerie Clarissa, the first gallery for photography in Germany. This gallery also specialized in experimental and generative art. When she donated her collection to the Kestner Museum in Hannover in 1968, the list of included artists was almost an encyclopedia of the avantgarde movement in photography in the 1960s. Among the artists were Théodore Bally, Monika von Boch, Hein Gravenhorst, Heinz Hajek-Halke, Roger Humbert, Manfred Kage, Gottfried and Ursel Jäger, René Mächler, Floris Neusüss, Heinrich Riebesehl - just to name a few.

GB: In the exhibition "Automat und Mensch," we are presenting a series of your pinhole structures from 1967. Each artwork is titled with a code such as, for example, 3.8.14 D 3.1. Can you describe the underlying method and idea behind this series and how you developed your concept of pinhole structures further at the dawn of the digital age?

GJ: The first so-called "Lochblendenstruktur" (pinhole structure) was conceived on the light table where I was experimenting with transparent superimposed slides containing patterns and dot matrices. The results were peculiar geometric patterns and shapes which I have further developed by using optical devices.

Multiple pinhole camera which can be rotated

The program and steps in order to make pinhole structures I have described later in a diagram, Entscheidungsstufen beim Aufbau modifizierter Lochblendenstrukturen, in 1976. This diagram was recently published in the exhibition catalogue Shape of Light by Tate Modern in 2018, and it illustrates the steps which lead to a certain pinhole structure. The code is equivalent to the steps as, for example, in 3.8.14 F 2.5, 1967, depicted in the diagram.

Although the first numeric character stands for the aparative system (multiple pinhole camera), the second one for the geometry of the multiple pinhole aperture, and so forth, I wouldn't want to describe all the parameters that lead finally to an "aesthetic state." But maybe you can comprehend now that I was basically building step by step a rational "history" of a photo- and data-based process.

Gottfried Jäger: Entwicklungsstufen beim Aufbau modifizierter Lochblendenstrukturen der Serie 3.8.14., 1967, diagram, drawing on paper, 70 x 100 cm, 1976

In the 1990s I started to use computers in my work. My friend and IT engineer Peter Serocka, at that time director at the visual laboratory of the mathematical faculty at University of Bielefeld, has developed a computer program based upon my optical system of two superposed pinhole structures - which he called matrices - which enabled him to imitate my pinhole structures. At the same time I shockingly became aware by reading a magazine that, independently from us, a Japanese group of mathematicians came up with the same results. So we got in touch with each other and we started a fruitful technological exchange with them, which resulted in reciprocal publications. This was basically my first access into my artistic practices with computers.

It was high time to deal with the new system also practically and not only theoretically. And as it is often the case when a historical shift of a system takes place, the shift started again through imitation and simulation of the pre-existing. I tied in with the pinhole structures and edited them with inherent instruments of computer technology and developed new image orders. Nowadays I am working in a hybrid way, a mix between conventional photographic techniques as well as cybernetic, computer-based instruments.

GB: In the beginning of generative photography, it was difficult to categorize this new form of photography while in Europe, especially, two main directions of photography were dominating the discourse on photography. On the one side there was subjective photography and the Otto Steinert school; on the other side, Karl Pawek's conception of documentary photography. You mentioned to me several times that leading art theorists were rather suspicious about generative photography. Retrospectively, one can say that generative aesthetics is widely used as a term among contemporary artists. Can we say that generative photography has finally entered into the art historical canon?

GJ: I have already referred to these two names in a previous question. Both were antipodes at the time when I developed the idea of generative photography. On the other hand, they also enhanced a disruptive evolution. Nowadays it is almost unimaginable how intense these grave battles between the two sides of realism and formalism, between document and experiment, were waged. It was a power struggle for interpretive sovereignty of what photography fundamentally was - its ontology - assuming that it would be possible to define this ambiguous notion exclusively.

An important step in the evolution on the subject was the exhibition Ungegenständliche Fotografie in Basel in 1960, which led to the exhibition Konkrete Fotografie in Bern in 1967, organized by an independent group of four Swiss artists referring to their idea of a self-referential form of photography to "concrete painting" (van Doesburg, 1930) and the Swiss concrete artists (Max Bill, etc.). One year later this was followed by the exhibition Generative Fotografie in Bielefeld. This is a short review of the history.

Nowadays the term "generative photography" can be found in almost every encyclopedia on photography. Currently, it will be used in the context of "pre-digital art," mentioned as such in the exhibition catalogue Shapes of Light - 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art at the Tate Modern in London in 2018.

Exhibition view Shape of Light. 100 Years of Photography and Abstract Art at Tate Modern, London 2018. Gottfried Jäger, Lochblendenstrukturen (pinhole structures), 1967

According to Wikipedia, it is described as "attempt for photography by using the tools of emerging computer technology and its graphic to enable a new form of artistic imagery". Fifty years after its introduction, it is an established category of photography and has entered in the art historical canon.

GB: Looking back 50 years, one can say that you are the father of generative photography, and you have published so many important books and essays. A selection of your most important writings have been assembled by Bernd Stiegler in Gottfried Jäger. Abstrakte, konkrete und generative Fotografie. Gesammelte Schriften, which was published in 2016. What would you consider as the theoretical basis of generative photography? Which essays (theory) are essential?

Vilém Flusser and Gottfried Jäger at 5th. Bielefeld Symposium on Fotografie at Fachhochschule Bielefeld, 1984, photography by Ralph Hinterkeuser

GJ: Partly I have already responded to this question through my previous statements. I could add to it a few names and thoughts. Based on Noam Chomsky's "generative grammar" as well as the thoughts on "generative aesthetics" by Max Bense and "cybernetic aesthetics" by Herbert W. Franke, the sources of generative photography derive not primarily - as opposed to "concrete photography" - from art historical sources, but rather from linguistics and philology, mostly from semiotics. My colleague from Bielefeld, Kirsten Wagner, has published an important essay in the exhibition catalogue Die Bielefelder Schule. Foto Kunst im Kontext in 2014: Generative Ästhetik im Kontext der Bielefelder Schule. This text contains a much more comprehensive answer to this question than I am capable to give you at this point. From my point of view, I would like to mention Herbert W. Franke as my first spiritus mentor and Vilém Flusser as my sharpest critic. Both have fundamentally influenced my career as an artist. I learned from Franke how to play with the machine - and from Flusser how to play against the machine. Today I would count the philosopher Lambert Wiesing and the literary theorist Bernd Stiegler among the theorists who help me on my way.

This interview took place on 29th July 2019 in German and was translated into English by Georg Bak