14 Central Quadrant Technique

14 Central Quadrant Technique

Uploaded by

maytorenacgerCopyright:

Available Formats

14 Central Quadrant Technique

14 Central Quadrant Technique

Uploaded by

maytorenacgerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

14 Central Quadrant Technique

14 Central Quadrant Technique

Uploaded by

maytorenacgerCopyright:

Available Formats

Oncoplastic Surgery: Central Quadrant Techniques

Kristine E. Calhoun and Benjamin O. Anderson

12

12.1

Introduction

Breast-conserving therapy was introduced as an alternative to breast sacrice for women affected by breast cancer beginning in the 1970s and clinical trials have since demonstrated equivalency in terms of overall survival between lumpectomy plus radiation and mastectomy [1, 2]. Although there are clear contraindications to lumpectomy, for the appropriately selected individual, breast-conserving therapy offers both effective treatment and the psychological benet of retention of the breast. In a traditional lumpectomy, there is no specic effort to obliterate the internal resection cavity. In fact, closing broglandular tissue can result in unsightly defects if alignment of the breast tissue is suboptimal. Fibroglandular tissue that is sutured closed at middle depth in the breast while the patient is supine on the operating table can result in a dimpled, irregular appearance when the patient stands up. Given this potential, most surgeons choose to close the skin of a lumpectomy without approximation of the underlying tissue. Although the simple scoop and run approach to lumpectomy may work well for small tumors, declivity of the skin and/or displacement of the nipple areola complex (NAC) may occur if the lesion removed from the breast is sizable and may create especially troubling defects for central lesions. For breast conservation to be effective, the primary tumor must be resected with adequate surgical margins while simultaneously maintaining the breasts shape and appearance, goals which may prove challenging and in

K. E. Calhoun B. O. Anderson (&) Breast Health Clinic, Department of Surgery, University of Washington, Seattle, USA e-mail: banderso@fhcrc.org K. E. Calhoun e-mail: calhounk@u.washington.edu

some settings seem to be conicting [3, 4]. In 1994, Audretsch [5] was one of the rst to advocate the use of oncoplastic surgery for repair of partial mastectomy defects by combining the techniques of volume reduction with immediate ap reconstruction. Although initially used to describe partial mastectomy combined with large myocutaneous ap reconstruction using the latissimus dorsi or the rectus abdominis muscles, oncoplastic surgery now more commonly describes numerous surgical techniques that utilize partial mastectomy and breast-ap advancement to address tissue defects following wide resection. Compared with breast reconstruction using a myocutaneous ap, breast-ap advancements are easily learned and implemented by breast surgeons, even those lacking formal plastic surgery training. A comprehensive understanding of normal ductal anatomy is critical to planning an oncoplastic partial mastectomy [3, 6]. The modern anatomic analysis of ductal anatomy suggests that the number of major ductal systems is probably fewer than ten [7]. The size of ductal segments is variable and whereas some ducts pass radially from the nipple to the periphery of the breast, others travel directly back from the nipple toward the chest wall. In contrast, well-dened breast vasculature allows the surgeon to remove and remodel large amounts of broglandular tissue without major risk of breast devascularization and/or tissue necrosis. The commonest sources of arterial blood supply in the human breast arise from the axillary and internal mammary arteries. By maintaining communication with one of these two arterial connections, one maintains an adequate blood supply for the breast parenchyma during tissue advancement and mastopexy closure. The use of oncoplastic surgical techniques for breast conservation allows wider resections without subsequent tissue deformity, and thereby allows surgeons to achieve wide surgical margins while preserving the shape and appearance of the breast [8]. Such techniques can be especially useful for more centrally located lesions, which when resected with standard surgical techniques may result

C. Urban and M. Rietjens (eds.), Oncoplastic and Reconstructive Breast Surgery, DOI: 10.1007/978-88-470-2652-0_12, Springer-Verlag Italia 2013

117

118

K. E. Calhoun and B. O. Anderson

in suboptimal cosmetic outcomes. Although specic oncoplastic techniques differ from one another, all of the approaches involve fashioning the tissue resection to the anatomic shape of the cancer while ensuring that wide margins, ideally more that 1 cm, are achieved in an optimal number of patients [3, 6]. The indications and contraindications for oncoplastic surgery are the same as those for traditional breast-conserving surgery, and such techniques should only be offered to those otherwise believed to be breast-preservation candidates on the basis of size and centricity. The techniques described in this chapter include those used for central segmental resections that utilize breast-ap advancement (so-called tissue displacement techniques) and include central lumpectomy, batwing mastopexy lumpectomy, donut mastopexy lumpectomy, and variations on reduction mastopexy lumpectomy which utilize a pedicle ap to restore the NAC.

third of MRI studies will show some area of enhancement that needs further assessment that ultimately proves to be histologically benign breast tissue [3]. A consensus statement from the American Society of Breast Surgeons [12] updated in 2010 supports the use of MRI for determining the extent of ipsilateral tumor or the presence of contralateral disease in patients with a proven breast cancer (especially those with invasive lobular carcinoma) when dense breast tissue precludes an accurate mammographic assessment. For cancers containing both invasive and noninvasive components, a combination of imaging methods may yield the best estimate of overall tumor size [13].

12.3

Perioperative Planning

12.2

Preoperative Planning

Patients undergoing central quadrant resections should undergo standard preoperative history taking and physical examination, with the elements of gynecologic, family, and social history, including smoking, emphasized. Special attention should be given to any prior breast surgical history, including the placement of breast implants. Needle sampling should be performed to provide tissue diagnosis of malignancy. At our institution, internal review of all external pathology slides is required to conrm that we agree with the histopathologic diagnosis. Those being considered for oncoplastic resections should undergo a standard preoperative breast imaging workup, which typically includes some combination of mammography, ultrasonography, and in selected circumstances breast MRI. Although mammography may underestimate the extent of ductal carcinoma in situ by as much as 12 cm, it is still warranted and is often the initial diagnostic study [9]. Although controversial, the use of MRI may contribute to the surgeons ability to preoperatively determine the extent of disease, especially for mammographically subtle and/or occult cancers, and to conceptualize the location of the tumor more three-dimensionally than allowed on mammography. Compared with mammographic and ultrasonographic images, the extent of disease seen on MRI may correlate best with the extent of tumor found on pathologic evaluation. In addition, MRI has the lowest false-negative rate in detecting invasive lobular carcinoma [10]. Although its sensitivity for detection of invasive breast cancer is high, MRI unfortunately has a low specicity of 68 % in the diagnosis of breast cancer before biopsy [11]. Up to one-

Once a central oncoplastic approach has been selected, decisions regarding the use of preoperative wire localization for nonpalpable malignancies must be made. In planning oncoplastic resections, the surgeon needs to accurately identify the area requiring removal. Silverstein et al. [14] suggested the preoperative placement of two to four bracketing wires to delineate the boundaries of a single lesion. In a study by Liberman et al. [15], wire bracketing of 42 lesions allowed complete removal of suspicious calcications in 34 patients (81.0 %). It has been suggested that single wire localization of large breast lesions is likelier to result in positive margins, because the surgeon lacks landmarks to determine where the true boundaries of nonpalpable disease are located. For such scenarios, multiple bracketing wires may assist the surgeon in achieving complete excision at the initial intervention. For more palpable lesions, such wire localizations may be a moot point. Skin landmarks should be marked with the patient sitting up in the preoperative area, including the inframammary crease, the anterior axillary fold at the pectoralis major muscle, the posterior axillary fold of the latissimus dorsi muscle, the sternal border of the breast, and the periareolar circle. Identifying these entities with the patient in the upright position is very important for the nal cosmetic outcome, because these anatomic sites may prove challenging to accurately locate once the patient is anesthetized and lying supine on the operating room table. Generally, for reductiontype procedures, markings will be placed on both breasts. For all oncoplastic techniques, the patient should be supine on the operating room table and with both arms abducted on arm boards and secured. It is preferable to have both breasts prepared and draped into the eld so that visual comparison with the patient in a beach chair position is possible as the wound is closed. Such an approach allows the surgeon to identify any areas of unnecessary tugging or dimpling which are inadvertently created so that they can be corrected.

12

Oncoplastic Surgery: Central Quadrant Techniques

119

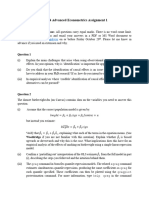

Fig. 12.1 Central lumpectomy. a Preoperative marking with the patient in the upright position. b Intraoperative marking with the patient in the supine position illustrating positional shift of the breast landmarks. c Initial skin incision revealing wide exposure over the target lesion. d Central resection. e Postexcision cavity. f Final closure

12.4

Central Quadrant Techniques

12.4.1 Central Lumpectomy

For those cancers involving the NAC, including Pagets disease of the nipple, the cosmetic impact of nipple removal with central lumpectomy typically accounts for the common use of mastectomy in this situation. In recent years, with improved NAC reconstructive capabilities, central lumpectomies have been utilized more. Although central lumpectomy removes the NAC and underlying central tissues, it typically leaves behind a signicant breast mound, especially for those with larger breasts at the baseline. The cosmetic outcome with central lumpectomy can range from good to outstanding, depending on the womans body habitus, and is likely to be better tolerated than reconstruction of an entire breast [3]. Central lumpectomy can be

particularly valuable in women with large breasts where loss of the entire breast with mastectomy may create prominent asymmetry. Surgical issues of NAC reconstruction in an irradiated eld, including wound-healing issues and NAC loss, must be considered, so early referral for plastic surgery is warranted. In central lumpectomy, the incision can be made in the pattern of a large parallelogram that encompasses the entire NAC, or can be more circular in nature (Fig. 12.1af). After excision of the skin island/NAC, short-distance mastectomy-type skin aps are raised along both sides of the wound. The dissection is carried down to the chest wall and the breast gland is lifted off the pectoralis muscle. After full-thickness excision of the tumor, four to six marking clips are typically placed at the base of the defect within the surrounding broglandular tissue for future imaging and radiation oncology purposes. A small drain may also be placed in the lumpectomy wound in cases where the

120

K. E. Calhoun and B. O. Anderson

dissection is more extensive and fear of seroma is increased. For adequate evaluation of margin status by the pathologist, sharp rather than cautery dissection should be considered, as sharp dissection will not alter the histological margins of the resected tissues with the so-called cautery effect. Larger intraparenchymal vessels can be ligated or coagulated during the dissection, and cautery can then be used on the exposed broglandular tissue faces to control bleeding. Once tissue specimens have been resected and hemostasis has been obtained, the broglandular tissue at the level of the pectoralis fascia is undermined so that breast-tissue advancement can be performed over the muscle. Once the broglandular tissues have been sufciently mobilized and hemostasis has been conrmed, the margins of the residual cavity are shifted together by the advancement of breast tissue over muscle and the defect is sutured at the deepest edges using 3-0 absorbable sutures. The direction of tissue advancement can be adjusted depending upon the location of the broglandular defect and the excess tissue that can be shifted to close it. The goal of the mastopexy is to perform as complete a closure over the pectoralis muscle as possible to discourage communication between the anterior skin and the deeper tissues. Side to side comparisons with the patient in an upright position are warranted to ensure that no unusual retractions of the tissues or unsightly cosmetic results have occurred. The supercial tissue layer is next closed with an interrupted subdermal 3-0 absorbable suture, and the skin is closed with 4-0 absorbable subcuticular sutures in routine fashion. Two variations on closure exist. The rst, which is more typical, involves closure in a manner which results in a scar that is a horizontal, straight line, and the second involves closing the wound utilizing a purse-string closure to facilitate areolar tattooing.

creating redundant skin folds at closure. Fibroglandular tissue dissection is carried down deep to the known cancer, with the depth in relation to the chest wall dictated by the position of the lesion within the breast. In most situations, the dissection is carried down to the chest wall and the breast gland is lifted off the pectoralis muscle in a fashion similar to that for central lumpectomy. The principles of sharp dissection and the placement of marking clips are also similar to those utilized in central lumpectomy. Following full-thickness resection of the target, mobilization of the broglandular tissue for mastopexy closure will likely be required. The breast tissue is elevated off of the chest wall at the plane between the pectoralis muscle and breast gland, and the broglandular tissue is advanced to close the resulting defect. The deepest parts are approximated by interrupted sutures. We typically secure the broglandular tissue to broglandular tissue and do not place anchoring stitches into the chest wall, thereby allowing the approximated breast tissues to move along the chest wall. The supercial layer is closed in the same fashion as in central lumpectomy. As this procedure can cause some lifting of the nipple, it may create asymmetry compared with the noncancerous breast. A contralateral lift can be performed after adjuvant radiation therapy has been completed and the treated breast has declared its new size and shape to achieve symmetry, although some plastic surgeons may choose to perform this symmetry procedure concurrent with the oncologic surgery.

12.4.3 Donut Mastopexy Lumpectomy

For segmentally distributed cancers located in the upper or lateral breast that approach the NAC, donut mastopexy lumpectomy can be used to achieve effective resection of long, narrow segments of breast tissue. Donut mastopexy avoids a visible long radial scar which is against Kraissls line or Langers line. In this procedure (Fig. 12.3af), two concentric lines are placed around the areola and a periareolar donut skin island is excised, with only a periareolar scar visible after this operation. Deepithelialization by separating this skin island from the underlying tissues is done, taking care to avoid full devascularization of the areolar skin. The width of the donut skin island should be approximately 1 cm, but is somewhat dependent on the size of the areola and the expected extent of excision. Removal of this tissue ring is required, as it allows both adequate access to and exposure of the breast tissue and closure of the skin envelope around the remaining broglandular tissue that will reduce tissue volume overall. A skin envelope is created in all directions around the NAC. The quadrant of breast tissue containing the target lesion is fully exposed utilizing the same dissection used for

12.4.2 Batwing Mastopexy Lumpectomy

For cancers adjacent to or deep to the NAC, but without direct involvement of the nipple, lumpectomy can successfully be performed without sacrice of the nipple itself. The batwing approach preserves the viability of the NAC while preserving the breast mound by using mastopexy closure to close the resulting broglandular defect of the full-thickness resection. This procedure may result in lifting of the nipple into the upper breast, and a contralateral lift may need to be performed to achieve symmetry, especially when the native breast is large and pendulous. Two similar semicircle incisions are made with angled wings on each side of the areola (Fig. 12.2ae). The two half-circles are positioned so they can be reapproximated to each other at wound closure. Removal of these skin wings allows the two semicircles to be shifted together without

12

Oncoplastic Surgery: Central Quadrant Techniques

121

Fig. 12.2 Batwing mastopexy lumpectomy. a Preoperative marking with the patient in the upright position. b Intraoperative marking with the patient in the supine position. c Resection cavity. d Final closure. e Postoperative result with the patient in the upright position

a skin-sparing mastectomy. The full-thickness breast gland is then separated from the underlying pectoralis muscle and delivered through the circumareolar incision. The segment of breast tissue with the tumor is resected in a wedgeshaped fashion, with the width of tissue excision required to achieve adequate surgical margins balanced against the difculty that will be created by virtue of an oversized segmental defect. The remaining broglandular tissue is returned to the skin envelope and the peripheral apical corners of the broglandular tissue are secured to each other and then anchored to the chest wall. This anchoring step maintains proper orientation of the mobilized broglandular tissue within the skin envelope during the initial phases of healing. A purse string using a 3-0 absorbable suture is placed around the areola opening, and is clamped at a size that reapproximates the original NAC. Interrupted inverted 3-0

absorbable sutures are placed subdermally around the NAC, at which time the purse-string suture is tied and then 4-0 subcuticular sutures are used to close the wound. Uplifting of the NAC may create mild asymmetry in comparison with the untreated breast. If desired, a contralateral lift can be performed to achieve symmetry.

12.4.4 Reduction Mastopexy Lumpectomy Modifications

Initially used in women with macromastia and excessive breast ptosis, this procedure is currently used for resection of lesions in the lower hemisphere of the breast between the 4 oclock and 8 oclock positions, where scoop and run lumpectomy using circumareolar incision would result in unacceptable down-turning of the nipple owing to scar

122 Fig. 12.3 Donut mastopexy lumpectomy. a Preoperative marking including marking of the region to be removed based on preoperative bracketing wires and concentric circles for skin donut excision. b Initial skin incision. c Delivery of tissue segment through the periareolar incision. d Remaining cavity after resection. e Purse-string closure. f Final operative result

K. E. Calhoun and B. O. Anderson

contracture after radiotherapy. This unpleasant cosmetic outcome can be prevented by using the technique of reduction mastopexy lumpectomy (Fig. 12.4af). Recently, the indications for using reduction techniques have been expanded to include women with centrally located tumors faced with NAC loss. In these situations, the reduction is coupled with a deepithelialized pedicle ap with an overlying skin island to recreate the NAC, ultimately resulting in a Wise-type scar and a neo-nipple [16]. In traditional reduction mammoplasty, a keyhole pattern incision is made and the skin above the areola is deepithelialized in preparation for skin closure. A superior pedicle ap is created by inframammary incision and undermining of the breast tissue off the pectoral fascia to mobilize the NAC and underlying tissues. Mobilization of the breast tissue allows palpation of both the deep and the supercial surfaces of the tumor, which can aid the surgeon in determining the lateral margins of excision around the

target lesion. When it is used for a central lesion, the primary tumor and overlaying NAC are resected down to the chest wall. The principle of sharp dissection and the placement of marking clips are the same as those for parallelogram mastopexy lumpectomy. A caudally located inferior ap is then deepithelialized, except for an appropriately sized skin island that will function as the neo-nipple. Following this, redundant medial, lateral, and superior tissues are then resected while preserving the pedicle tissue. An incision at the inframammary crease facilitates mobilization and assists in restoration of normal breast shape and contour. Once all tissues have been resected, the central, inferior pedicle is mobilized, brought cephalad, and utilized to occupy the defect created by removal of the prior NAC. The neo-nipple is sutured to the margins of NAC resection. The medial and lateral breast aps are undermined and sutured together to ll the excision defect, leaving a typical

12

Oncoplastic Surgery: Central Quadrant Techniques

123

Fig. 12.4 Reduction mastopexy lumpectomy. a Preoperative skin markings showing the keyhole incision pattern. b Initial skin incision. c Full-thickness resection. d Excised specimen and residual cavity. e Closure. f Final result

inverted-T scar. Variations of this technique have been reported, including the Grisotti ap, which extends the pedicle laterally and results in an inferior and laterally sweeping incision [16], and free nipple graft from the skin of the contralateral reduction tissue [17]. Finally, some choose to utilize the reduction ap without creation of a neo-nipple, leaving the patient with a Wise-type incision and the choice of NAC in a delayed fashion [16].

the dissected breast that might distort the oncoplastic closure. These drains are typically removed either prior to discharge or on the rst postoperative day in the clinic.

12.6

Complications

12.5

Postoperative Management

Although drains are rarely required in standard partial mastectomy cases, with more extensive dissections, such as donut mastopexy lumpectomy, uid accumulation can become more pronounced and require postoperative aspiration. In recent years, we have started to place small, 15F drains overnight to avoid excessive uid accumulation in

When using central oncoplastic approaches, surgeons without formal plastic surgery training must determine which procedures they are comfortable performing without plastic surgery consultation or intraoperative collaboration [3]. Although these techniques appear to be relatively safe in the immediate postoperative period, issues such as wound infection, fat necrosis, and delayed healing with the more advanced techniques are all potential, reported complications [1820]. Despite more extensive resections, hematomas requiring reoperation appear to be infrequent, occurring roughly 23 % of the time in two recent studies [19, 20]. The

124

K. E. Calhoun and B. O. Anderson

blood supply of the external nipple arises from underlying broglandular tissue using major lactiferous sinuses rather than the collateral circulation from surrounding areolar skin, so nipple necrosis may occur if dissection extends high up behind the nipple, but is also fortunately rare [3]. Finally, in a review of 84 women who underwent partial mastectomy and radiation therapy, Kronowitz et al. [21] showed that immediate repair of partial mastectomy defects with local tissues results in fewer complications (23 vs. 67 %) and better aesthetic outcomes (57 vs. 33 %) than that with a latissimus dorsi ap, which some surgeons used for delayed reconstructions [22].

12.7

Results

Fig. 12.5 Specimen inked by the surgeon to designate anterior, posterior, medial, lateral, inferior, and superior margins

The main goal of oncoplastic lumpectomy remains negative surgical margin resection. Complete excision of calcied lesions and masses should be conrmed with specimen radiography during surgery. Additional oriented margins can be resected prior to mastopexy closure when the radiograph suggests inadequate resection may have occurred, hopefully eliminating the need for a delayed re-excision. Although some centers use intraoperative analysis with a frozen section to aid in decisions regarding the resection of additional segments of tissue, thus is not our policy. Multicolored inking performed by the surgeon in the operating room helps to improve margin identication. Inking kits are now available with six colors (black, blue, yellow, green, orange, and red), which are very useful for labeling all of the surgical margins (superior, inferior, medial, lateral, supercial, and deep) (Fig. 12.5). Clear uniformity between the surgeon and the pathologist in terms of what color means what margin is required, especially when inadequate margins are identied that require reoperation. Although the historical gold standard for a negative surgical margin has been 10 mm, what constitutes a true negative margin differs widely from center to center, with 3 mm or greater accepted at our institution. Low local recurrence rates after breast conservation therapy, especially in the era of postlumpectomy irradiation, can be achieved with an intermediate surgical margin width between 1 and 10 mm [1, 2]. If re-excision is needed for inadequate surgical margins following the initial resection, both the surgical approach and the timing of the operation must be considered [3]. When the positive margin involves a minority of the specimen, the entire biopsy cavity does not need to be re-excised, and instead can be directed toward the inadequate region. If re-excision is delayed for 34 weeks, the previous seroma cavity may be nearly reabsorbed, which leaves a brous biopsy cavity that can be

easily located by intraoperative palpation. With noninvasive cancer, Silverstein et al. [14] have suggested that it is feasible to delay re-excision for up to 3 months, at which point the seroma cavity has been fully reabsorbed. When all the resection margins are positive, mastectomy may be needed to attain satisfactory surgical clearance. In this instance, it may be technically challenging to include both the initial oncoplastic incision and the NAC in a subsequent total mastectomy, and consultation with the plastic surgeon in the event of immediate postmastectomy reconstruction is mandatory. Despite a clear ability to resect widely with these central oncoplastic techniques, inadequate margins remain an issue. Although reports remain sparse, reported rates of inadequate margins following initial resection range from 8 to 22 % [19, 20, 2328]. The decision between a re-excision and a mastectomy must be based on the operating surgeons ability to appropriately localize the involved region, and with more advanced resections this may only be possible with breast sacrice. Although large studies of long-term outcomes specically addressing oncoplastic approaches in breast conservation are lacking, the limited available results continue to look promising. One investigation from Europe followed 148 women for a median of 74 months (range 10108 months) and only two were lost to follow-up. Among the 146 individuals available for analysis, there were only ve women (3 %) who had an ipsilateral inbreast cancer recurrence after 5 years and all had either T2 or T3 tumors at presentation. Rietjens et al. [29] argued that recurrence rates for women with oncoplastic resections and concurrent radiation therapy were comparable to the inbreast recurrence rates reported with standard breast conservation techniques. Studies of more limited follow-up recently reported no in-breast local recurrences at 26 months [19], 38 months [20], and 34 months [16],

12

Oncoplastic Surgery: Central Quadrant Techniques

125 6. Chen CY, Calhoun KE, Masetti R, Anderson BO (2006) Oncoplastic breast conserving surgery: a renaissance of anatomically-based surgical technique. Minerva Chir 61(5):421434 7. Love SM, Barsky SH (2004) Anatomy of the nipple and breast ducts revisited. Cancer 101(9):19471957 8. Silverstein MJ (2003) An argument against routine use of radiotherapy for ductal carcinoma in situ. Oncology (Huntingt) 17(11):15111533; discussion 15331534, 1539, 1542 passim 9. Holland R, Faverly DRG (2002) The local distribution of ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast: whole-organ studies. In: Silverstein MJ (ed) Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast, 2nd edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 240254 10. Boetes C, Veltman J, van Die L, Bult P, Wobbes T, Barentsz JO (2004) The role of MRI in invasive lobular carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat 86(1):3137 11. Bluemke DA, Gatsonis CA, Chen MH, DeAngelis GA, DeBruhl N, Harms S et al (2004) Magnetic resonance imaging of the breast prior to biopsy. JAMA 292(22):27352742 12. The American Society of Breast Surgeons Consensus Statement: The use of magnetic resonance imaging in breast oncology, 27 July 2010. http://www.breastsurgeons.org/statements 13. Silverstein MJ, Lagios MD, Recht A, Allred DC, Harms SE, Holland R et al (2005) Image-detected breast cancer: state of the art diagnosis and treatment. J Am Coll Surg 201(4):586597 14. Silverstein MJ, Larson L, Soni R, Nakamura S, Woo C, Colburn WJ et al (2002) Breast biopsy and oncoplastic surgery for the patient with ductal carcinoma in situ: surgical, pathologic, and radiologic issues. In: Silverstein MJ (ed) Ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast, 2nd edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 185204 15. Liberman L, Kaplan J, Van Zee KJ, Morris EA, LaTrenta LR, Abramson AF et al (2001) Bracketing wires for preoperative breast needle localization. AJR Am J Roentgenol 177(3):565572 16. Huemer GM, Schrenk P, Moser F, Wagner E, Wayand W (2007) Oncoplastic techniques allow breast-conserving treatment in centrally located breast cancers. Plast Reconstr Surg 120(2):390398 17. Schoeller T, Huemer GM (2006) Immediate reconstruction of the nipple/areola complex in oncoplastic surgery after central quadrantectomy. Ann Plast Surg 57(6):611616 18. Iwuagwu OC (2005) Additional considerations in the application of oncoplastic approaches. Lancet Oncol 6(6):356 19. Meretoja TJ, Svarvar C, Jahkola TA (2010) Outcome of oncoplastic breast surgery in 90 prospective patients. Am Jour Surg 200(2):224228 20. Roughton MC, Shenaq D, Jaskowiak N, Park JE, Song DH (2012) Optimizing delivery of breast conservation therapy: a multidisciplinary approach to oncoplastic surgery. Ann Plast Surg 69(3):250255 21. Kronowitz SJ, Feledy JA, Hunt KK, Kuerer HM, Youssef A, Koutz CA et al (2006) Determining the optimal approach to breast reconstruction after partial mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg 117(1):111 22. Nahabedian MY (2006) Determining the optimal approach to breast reconstruction after partial mastectomy: discussion. Plast Reconstr Surg 117(1):1214 23. Bong J, Parker J, Clapper R, Dooley W (2010) Clinical series of oncoplastic mastopexy to optimize cosmesis of large volume resections for breast conservation. Ann Surg Oncol 17(12): 32473251 24. Naguib SF (2006) Oncoplastic resection of retroareolar breast cancer: central quadrantectomy and reconstruction by local skinglandular ap. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst 18(4):334347 25. Clough K, Lewis J, Couturuad B et al (2003) Oncoplastic techniques allow extensive resections for breast conserving therapy of breast carcinomas. Ann Surg 237(1):2634

although some distant recurrences were reported. These results appear equivalent to those for women treated with traditional lumpectomy and should serve to allay any fears of cosmesis being favored over cancer control.

12.8

Conclusions

Although shown to be a reasonable alternative to mastectomy for the appropriately selected breast cancer patient, traditional scoop and run lumpectomy may result in poor cosmesis. Central oncoplastic techniques, including central lumpectomy, batwing mastopexy lumpectomy, donut mastopexy lumpectomy, and variations of reduction mastopexy lumpectomy have been developed to address this issue. By combining large-volume tumor removal with breast-ap advancements, the oncoplastic approaches allow wider margins of resection and better breast shape and contour preservation. Candidates are those felt to be standard lumpectomy candidates and include those with no evidence of multicentric disease. Standard preoperative workup, including dedicated breast imaging, and preoperative wire localization are necessary to aid the surgeon in successful resection. Complications of tissue necrosis are fortunately rare, despite sometimes signicant remodeling of the broglandular tissues due to the breasts rich blood supply. Outcomes appear at least equivalent to those for standard breast conservation techniques, although large case series are lacking. Despite this paucity of long-term results, oncoplastic lumpectomy can be learned by individuals familiar with breast surgical techniques and generally results in better cosmesis and equivalent oncologic outcomes.

References

1. Veronesi U, Cascinelli N, Mariani L, Greco M, Saccozzi R, Luini A et al (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347(16):12271232 2. Fisher B, Anderson S, Bryant J, Margolese RG, Deutsch M, Fisher ER et al (2002) Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. N Engl J Med 347(16):12331241 3. Anderson BO, Masetti R, Silverstein MJ (2005) Oncoplastic approaches to partial mastectomy: an overview of volumedisplacement techniques. Lancet Oncol 6(3):145157 4. Masetti R, Pirulli PG, Magno S, Franceschini G, Chiesa F, Antinori A (2000) Oncoplastic techniques in the conservative surgical treatment of breast cancer. Breast Cancer 7(4):276280 5. Audretsch WP (2006) Reconstruction of the partial mastectomy defect: classication and method. In: Spear SL (ed) Surgery of the breast: principle and art, 2nd edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, pp 179216

126 26. Losken A, Elwood E, Styblo T et al (2002) The role of reduction mammoplasty in reconstructing partial mastectomy defects. Plast Reconstr Surg 109(3):968975 27. McCulley S, Macmillan R (2005) Therapeutic mammoplastyanalysis of 50 consecutive cases. Br J Plast Surg 58(7): 902907

K. E. Calhoun and B. O. Anderson 28. Caruso F, Catanuto G, De Meo L et al (2008) Outcomes of bilateral mammoplasty for early stage breast cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol 34(10):11431147 29. Rietjens M, Urban CA, Rey PC et al (2007) Long-term oncological results if breast conservation treatment with oncoplastic surgery. J Breast 16(4):387395

You might also like

- The Sword of Caine A V5 Guide To The Sabbat - V5 10-15-2021Document158 pagesThe Sword of Caine A V5 Guide To The Sabbat - V5 10-15-2021Cirion Barboza75% (12)

- 2022 FlowFit Prep ManualDocument10 pages2022 FlowFit Prep ManualMOVEMENT SCHOOLNo ratings yet

- Review: Benjamin O Anderson, Riccardo Masetti, Melvin J SilversteinDocument13 pagesReview: Benjamin O Anderson, Riccardo Masetti, Melvin J SilversteinsanineseinNo ratings yet

- 03 AnatomyDocument9 pages03 AnatomymaytorenacgerNo ratings yet

- Clough K Oncoplasty BJSDocument7 pagesClough K Oncoplasty BJSkomlanihou_890233161No ratings yet

- Mammoplasty Nottingham (6028)Document13 pagesMammoplasty Nottingham (6028)imtinanNo ratings yet

- Oncologic Safety of Conservative Mastectomy in The Therapeutic SettingDocument10 pagesOncologic Safety of Conservative Mastectomy in The Therapeutic SettingIdaamsiyatiNo ratings yet

- Atlas of Breast DeformityDocument17 pagesAtlas of Breast Deformitykomlanihou_890233161100% (1)

- Incision in Breast Oncoplastic SurgeryDocument26 pagesIncision in Breast Oncoplastic Surgeryccmcshh surgery100% (1)

- OncoplasticDocument14 pagesOncoplasticYefry Onil Santana MarteNo ratings yet

- Defining Skin-Sparing Mastectomy Surgical TechniquesDocument9 pagesDefining Skin-Sparing Mastectomy Surgical TechniqueswillyoematanNo ratings yet

- JBC 15 350Document6 pagesJBC 15 350Andres VasquezNo ratings yet

- Kopkash 2018Document6 pagesKopkash 2018Yefry Onil Santana MarteNo ratings yet

- Clinical Study: Extreme Oncoplastic Surgery For Multifocal/Multicentric and Locally Advanced Breast CancerDocument9 pagesClinical Study: Extreme Oncoplastic Surgery For Multifocal/Multicentric and Locally Advanced Breast CancerAsti DwiningsihNo ratings yet

- Treatment of Symptomatic Macromastia in A Breast Unit: Research Open AccessDocument6 pagesTreatment of Symptomatic Macromastia in A Breast Unit: Research Open AccessRamiro Castro ApoloNo ratings yet

- BreastReconstruction Review 2016Document9 pagesBreastReconstruction Review 2016Mohammed FaragNo ratings yet

- Oncoplastic and Reconstructive BreastDocument14 pagesOncoplastic and Reconstructive BreastYefry Onil Santana Marte100% (1)

- Residual Breast Tissue After Mastectomy, How Often and Where It Is LocatedDocument11 pagesResidual Breast Tissue After Mastectomy, How Often and Where It Is LocatedBunga Tri AmandaNo ratings yet

- Palliative Mastectomy Revisited - PMCDocument4 pagesPalliative Mastectomy Revisited - PMCTony YongNo ratings yet

- Breast Cancer SurgeryDocument6 pagesBreast Cancer SurgeryΔρ Βαιος ΑγγελοπουλοςNo ratings yet

- MastopexyDocument10 pagesMastopexyMei WanNo ratings yet

- Case ReportDocument7 pagesCase Reportjeryesmadanat5No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S174868151730181X MainDocument9 pages1 s2.0 S174868151730181X MainChiara BoccalettoNo ratings yet

- 2 StageprepecDocument10 pages2 StageprepecsalyouhaNo ratings yet

- ASCO 2014 CrossDocument6 pagesASCO 2014 Crossdrrajeshb77No ratings yet

- Oncological Safety of Prophylactic Breast Surgery: Skin-Sparing and Nipple-Sparing Versus Total MastectomyDocument9 pagesOncological Safety of Prophylactic Breast Surgery: Skin-Sparing and Nipple-Sparing Versus Total MastectomynariecaNo ratings yet

- Janie Grumley EODocument6 pagesJanie Grumley EOAeijaz NoorNo ratings yet

- Selective Capsulotomies and Partial Capsulectomy inDocument8 pagesSelective Capsulotomies and Partial Capsulectomy inirdaNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s12609 019 0305 3Document8 pages10.1007@s12609 019 0305 3Yefry Onil Santana MarteNo ratings yet

- Dorsal FlapDocument11 pagesDorsal FlapDjeify PessoaNo ratings yet

- 34 Use of Ultrasound in Breast Surgery.Document16 pages34 Use of Ultrasound in Breast Surgery.waldemar russellNo ratings yet

- Asian GynecomastiaDocument5 pagesAsian GynecomastiaAngga Putra Kusuma KusumaNo ratings yet

- BR 17102023Document19 pagesBR 17102023Maxi AbalosNo ratings yet

- Index Study Chest Wall Perforator Flaps For Partial BreastDocument7 pagesIndex Study Chest Wall Perforator Flaps For Partial BreastKushicaNo ratings yet

- Minimizing Clearance Issues With Prone Breast Patients On Varian Linear Accelerators Through Isocenter PlacementDocument18 pagesMinimizing Clearance Issues With Prone Breast Patients On Varian Linear Accelerators Through Isocenter Placementapi-484763634No ratings yet

- Parotidectomy For Benign Parotid Tumors: An Aesthetic ApproachDocument6 pagesParotidectomy For Benign Parotid Tumors: An Aesthetic ApproachamelNo ratings yet

- Curroncol 28 00413Document9 pagesCurroncol 28 00413Mahmoud ShahinNo ratings yet

- Sili Kono MaDocument4 pagesSili Kono MaDella Rahmaniar AmelindaNo ratings yet

- December 2017 1512132618 151Document3 pagesDecember 2017 1512132618 151D Tariq HNo ratings yet

- Colectomiile Deschise Si LaparoDocument28 pagesColectomiile Deschise Si LaparoAdrian Marius SilaghiNo ratings yet

- Oncoplastic Breast SurgeryDocument27 pagesOncoplastic Breast SurgeryReem Amr El-DafrawiNo ratings yet

- Consensus Guideline On Breast Cancer Lumpectomy MarginsDocument6 pagesConsensus Guideline On Breast Cancer Lumpectomy MarginsSubhamSarthakNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Breast Rekon Presentasi 10 Okt 18 RevisiDocument57 pagesJurnal Breast Rekon Presentasi 10 Okt 18 RevisiFebriadi RNo ratings yet

- Endoscopic Mammae (Rev1)Document18 pagesEndoscopic Mammae (Rev1)Ronaldo BafitNo ratings yet

- Preservation of Breast Ligamentous Structures in MDocument9 pagesPreservation of Breast Ligamentous Structures in MLaura ZambranoNo ratings yet

- Cutaneous Breast Radiation-Associated AngiosarcomaDocument8 pagesCutaneous Breast Radiation-Associated AngiosarcomatiaoyueasplNo ratings yet

- Robotic Image Guided BiopsyDocument6 pagesRobotic Image Guided BiopsymnasihsNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Ultrasound Diagnosis For Intraductal Spread of Primary Breast CancerDocument10 pagesComprehensive Ultrasound Diagnosis For Intraductal Spread of Primary Breast CancerferdiNo ratings yet

- Postmastectomy Breast Reconstruction With The Totally Autologous Latissimus Dorsi Flap in The Thin, Small-Breasted Woman - Give It More Thought!Document14 pagesPostmastectomy Breast Reconstruction With The Totally Autologous Latissimus Dorsi Flap in The Thin, Small-Breasted Woman - Give It More Thought!562rjgnf8hNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal (Quantitative) Title: Minimizing Clearance Issues With Prone Breast Patients On Varian Linear AcceleratorsDocument4 pagesResearch Proposal (Quantitative) Title: Minimizing Clearance Issues With Prone Breast Patients On Varian Linear Acceleratorsapi-484763634No ratings yet

- Mastectomy - UpToDateDocument41 pagesMastectomy - UpToDateraphael.nascimentoNo ratings yet

- A Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy Retrospective Planning Study oDocument25 pagesA Volumetric Modulated Arc Therapy Retrospective Planning Study oDAHI ELHADJNo ratings yet

- Procedural Difficulty Differences According To TumDocument11 pagesProcedural Difficulty Differences According To TumDaniel Gonzales LinoNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1653808Document16 pagesNihms 1653808luis david gomez gonzalezNo ratings yet

- Component SeparationDocument23 pagesComponent Separationismu100% (2)

- Gougoutas 2016Document2 pagesGougoutas 2016salyouhaNo ratings yet

- Mastectomy (Case Analysis)Document7 pagesMastectomy (Case Analysis)Lester_Ocuaman_2248No ratings yet

- Postoperative Outcomes of Breast Reconstruction AfDocument6 pagesPostoperative Outcomes of Breast Reconstruction AfDiana AlexandraNo ratings yet

- Early Postoperative Complications After Oncoplastic Reduction - PMCDocument14 pagesEarly Postoperative Complications After Oncoplastic Reduction - PMCluis david gomez gonzalezNo ratings yet

- Pezner 2015Document5 pagesPezner 2015drrajeshb77No ratings yet

- Breast MRI: Guidelines From The European Society of Breast ImagingDocument12 pagesBreast MRI: Guidelines From The European Society of Breast Imagingdoni AfrianNo ratings yet

- Oncoplastic Breast Surgery Techniques for the General SurgeonFrom EverandOncoplastic Breast Surgery Techniques for the General SurgeonNo ratings yet

- My Search For The Truth About UFOs - Part 1 - The First Sighting. - by Jeremy McGowan - MediumDocument22 pagesMy Search For The Truth About UFOs - Part 1 - The First Sighting. - by Jeremy McGowan - MediumgigajohnNo ratings yet

- Australian Paper ManufacturersDocument3 pagesAustralian Paper ManufacturersAhsan Khan100% (1)

- Acute Care Toolkit 15 Flowcharts Nov19 0Document7 pagesAcute Care Toolkit 15 Flowcharts Nov19 0Ash AmeNo ratings yet

- Parker Sarah A - Crystal Bloom 3 - To Flame A Wild FlowerDocument415 pagesParker Sarah A - Crystal Bloom 3 - To Flame A Wild FlowermichchoroNo ratings yet

- Zeiss Axiolab5 ManualDocument137 pagesZeiss Axiolab5 Manualasel.samaranayakeNo ratings yet

- Tle 1Document2 pagesTle 1Baby Jenn MoradoNo ratings yet

- Kadina Designs Company Profile: A InaDocument8 pagesKadina Designs Company Profile: A Inaayman sobhyNo ratings yet

- Mark Z. Jacobson Stanford UniversityDocument45 pagesMark Z. Jacobson Stanford Universityanmn123No ratings yet

- Ppe Coverall FinalDocument58 pagesPpe Coverall FinalKrishna Chaitanya V SNo ratings yet

- SL - No Chainage Distance (M) Area (SQM) Avg Area (SQM) Volume (Cum) Remarks A - ExcavationDocument5 pagesSL - No Chainage Distance (M) Area (SQM) Avg Area (SQM) Volume (Cum) Remarks A - ExcavationbalasubramaniamNo ratings yet

- Soot Yeild Data PDFDocument241 pagesSoot Yeild Data PDFAda Darmon100% (1)

- Spreading Dynamics of Polymer Nanodroplets: Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185, USADocument10 pagesSpreading Dynamics of Polymer Nanodroplets: Sandia National Laboratories, Albuquerque, New Mexico 87185, USAmh123456789No ratings yet

- Linear Ic Applications: Unit-1 & Unit-2 Long Answer QuestionsDocument4 pagesLinear Ic Applications: Unit-1 & Unit-2 Long Answer QuestionsPraneetha VarmaNo ratings yet

- Restorative With Answers (9.2023) Students' VersionDocument48 pagesRestorative With Answers (9.2023) Students' Versionasad0% (1)

- I CL Oz NewsletterDocument29 pagesI CL Oz NewsletterElvio ATNo ratings yet

- Flower and PollinationDocument2 pagesFlower and Pollinationedgdel03No ratings yet

- Dieting: BBC Learning English 6 Minute EnglishDocument5 pagesDieting: BBC Learning English 6 Minute EnglishEzequiel García PalomoNo ratings yet

- MS For Rectification Work of Air BubblesDocument10 pagesMS For Rectification Work of Air BubblesFa DylaNo ratings yet

- Water Insight - TU Delft - Part 1Document61 pagesWater Insight - TU Delft - Part 1carolinaNo ratings yet

- Dokter IGD Jan 2021Document22 pagesDokter IGD Jan 2021Valentina IndahNo ratings yet

- Maamoura and Baraka Development Project 3314.02.DACC.15059Document18 pagesMaamoura and Baraka Development Project 3314.02.DACC.15059AHMED AMIRANo ratings yet

- A Modified Switching Strategy For Asymmetric Half-Bridge Converters For Switched Reluctance MotorDocument6 pagesA Modified Switching Strategy For Asymmetric Half-Bridge Converters For Switched Reluctance MotorEmílio FerroNo ratings yet

- RA 6969 Toxic Substances and Hazardous and Nuclear Wastes Control ActDocument4 pagesRA 6969 Toxic Substances and Hazardous and Nuclear Wastes Control ActFender BoyangNo ratings yet

- Nail Cakirhan - TurkeyDocument67 pagesNail Cakirhan - TurkeyDavit J VichtoraNo ratings yet

- Learning Autodesk Inventor 2010 Sheet Metal DesignDocument2 pagesLearning Autodesk Inventor 2010 Sheet Metal DesignHazem AlsharifNo ratings yet

- EC374 Advanced Econometrics Assignment 1Document2 pagesEC374 Advanced Econometrics Assignment 1Paramjot PandaNo ratings yet

- Aboard The Space ShuttleDocument37 pagesAboard The Space ShuttleBob AndrepontNo ratings yet

- At5St14 - 010 - Rivadeneira Et Al - Hobbits From The Deep South + RevisorDocument4 pagesAt5St14 - 010 - Rivadeneira Et Al - Hobbits From The Deep South + RevisorIvan HacheNo ratings yet