Learning To See in Melanesia

Learning To See in Melanesia

Uploaded by

Sonia LourençoCopyright:

Available Formats

Learning To See in Melanesia

Learning To See in Melanesia

Uploaded by

Sonia LourençoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Learning To See in Melanesia

Learning To See in Melanesia

Uploaded by

Sonia LourençoCopyright:

Available Formats

L ECTURER S L EARNING

INTRODUCTION :

TO SEE IN

M ELANESIA

Up to a point, the longer one lives or works, the more one knows, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say the more knowing one has done, the more occasions there have been when one is aware that some piece of knowledge has become displaced by another. The facility for displacement is at the heart of the imaginative life. (There is a point, indeed, to learning it!) Yet there always remain comprehensionsideas, understandings, concepts, interpretationsthat are hard to dislodge, or that one may not wish to, or that grow precisely as other things move, and we can include here certainties as well as prejudices. The oscillation between what stays in place and what shifts and travels applies to any order of phenomena, despite radically different ways of apprehending or sensing things. So it is as true for what we see with the eyes as for anything else. There is, of course, nothing at all new in saying this. However, these lectures are an attempt to make that oscillation evident, playing offas different possibilities for knowingwhat we think we see against what we might be seeing, for one very interesting part of the world. I leave the we open for whoever might wish to be included.

Introduction

Over the period when I was teaching undergraduates and masters students in Cambridge, I gave, on several occasions, a short set of lectures that in their time contributed to diverse papers (courses). These included an area paper on the Pacific, an option paper on Anthropology, Communication, and the Arts, and the MPhil option

MARILYN STRATHERN

on the Work of the Museum. Whereas other lectures were constantly changing, Learning to see in Melanesia more or less kept the form that is presented here. Given the multiple lives that Ialong with colleagues and students of coursewas leading, they became for me a moment to catch breath, to pause at a specific ethnographic / theoretical juncture, to draw again on a never-ceasing source of stimulus. That moment was also a return to and thus a continuing propelling forward of certain truisms about anthropological work.

Preliminary comments to the present lectures

The questions that time fails to wash away arise from the particulars of inquiry. However erroneously or awkwardly the particulars are framed, the prompt for every description is what it is that requires describing. That relation is as fundamental to the didactic or pedagogic enterprise as it is to the whole descriptive enterprise of academia. Description includes explanation, and sometimes explanations can vaporize what requires explainingan original puzzle vanishes. But since what they are often trying to explain are aspects of peoples work and lives they know that they have only partially grasped, anthropologists will as often try not to erase the original puzzle. On the contrary they (the anthropologists) may take pains to convey what interested them in the first place and made them see a puzzle. Among the filaments that connected me to the issues captured in these lectures was that they enabled a demonstration of the

2

1. Between 19932008, in the company of diverse colleagues: Amiria Henare, Anita Herle, James Leach, Gilbert Lewis, Andrew Moutu, Carole Pegg, Susanna Rostas. At the Cambridge Department of Social Anthropology, as it then was, lecture courses were organized and examined by the Department as whole, there being either four or five examinations (also called papers) that an undergraduate or masters student would sit in any one year. It would be rare for a course (a paper) to be given by one person; courses were generally composed of several contributions from different members of staff. This four-part series was one such contribution. (The shortand intenseteaching term at Cambridge meant that eight was the most regular unit of hour-long lectures to be offered as part of a course, and a half unit of four not uncommon. From the students point of view, lectures were supplemented by seminars and supervisions [tutorials], which demanded constant essay writing.) 2. One of Wagners favorite quotations refers to the anthropologist wanting to be figure and ground at the same time (see, for example, Wagner 2011).

LECTURERS INTRODUCTION

consequent entailment: even if one made a terrible hash of interpretation one could show that there were issues demanding exploration. The puzzles would outreach attempts to grasp them. In a way (the conversation takes place in retrospect) this matched what teachers were trying to say to their students in general: Immerse yourself in your readingthere are things to be understood that go way beyond what we can tell you. But if you can see that, then you will also see why we pay so much attention to how we make our accounts, to framing, theory, explanation. Many of the photographs that accompanied these lectures were proxy for textual immersionhowever fleetingly, the image occupied the whole screen. There was another match, that is, between these specific lectures and what a teacher in anthropology might hope was a truism for their students. Not everything need be seen though the prism of current interests; it is not only for their historic value or for a narrative of social change, so-called, that one attends to practices perceived to be of other times. Whereas problems and issues in the present have the self-evident character of current concerns, past puzzles are illuminating precisely because they cannot conceal their contingent or assembled character. Any temporal / cultural moment is ripe for such attention, regardless of what happens(ed) subsequently, and anthropologists disparage their own capacities for response on the occasions when they insist that interest in a phenomenon lies primarily in its relevance to what is perceived as the present. There are very good reasons why a specifically social anthropology, and its always rejuvenated crop (as in seeds sown and grown) of current students, should be alert, astutely, to what is going on around it. Yet one of such an anthropologys gifts is to be able to make as part of that contemporary going-on diverse epochs, venues, conjunctures, and assemblages from all kinds of passages of social life. The photographs were not just illustrativethey were also up on the screen in the here and now in your face.

3

There is a consequence to this. It is to do with how we problematize present-day concerns. There is no dearth of imaginings here, though, as often as not, present-day problems take the form of a crisis of some sort. We might be thinking of the forced relocation of populations; of the twin mirrors of cosmopolitanism and global3. With a nod to Paul Rabinow (2008).

MARILYN STRATHERN

ization; of the pressing interests of an era of financialization that cuts across everything in its computations of personal and material value; of the desperate ubiquity of violence, witting and unwitting; of unprecedented ecological shifts. Yet it would be an illusion to think that past concerns have no role to play in the present, and I do not necessarily mean concerns relating directly to such issues. The illusion derives from specific knowledge practices that focus on measuring the relevance of different materials to whatever concerns are at hand. This assumes that the concerns are shared (are ubiquitous), and that differentiations come in cultures and societies diverse ways of conceiving of them, including not conceiving them at allas in practices that seem to have no bearing on them. However, conceptualization is also itself an issue, that is, the very way in which problems are set up or concerns are analyzed or otherwise comprehended depends crucially on the concepts they mobilize. As an alternative open to it, anthropology might do well to reflect on another face to this: on the idea that it is instead the faculty of conceptualization that everyone shares, and it is bound to be directed towards quite different and diverse concerns. In retrospect, the lectures might belong here. In any event, it is surely a truism that there is huge diversity in the puzzles that people make for themselves.

4

Catching breath. In the midst of diversions elsewhere, these lectures brought me again and again to Melanesia, and particularly to Papua New Guinea, at a certain moment in time, yet to what I can only describe as a depth of intellectual refreshment. The phrase good to think with has become a familiar companion to many and in many circumstances. However, I would like to give to that good something close to an ethical connotation. It made of me a good person to be thinking through the materials that have been so richly reported from that country. It felt as though I was using my brain appropriately. It also felt that I was properly acknowledging the life of

5 6

4. To paraphrase Viveiros de Castro (2003) 5. It should be said that many of them are materials that, following the establishment in 1966 of Papua New Guineas first university and the practice of local research, Papua New Guinean academics also draw on. 6. I dont know how else to put it. (And, needless to say, this was no guarantee of a good analysis.) Engaging with these materials was in and of itself a rewarding exercise; at the same time the backdrop was the increasing instrumentalism of academic activity across the UK. The audit culture had bitten deep into ones

LECTURERS INTRODUCTION

relationships; certainly they reminded me that there was something still, and always, owed. The last occasion on which the lectures were given, as a free-standing set, they were dedicated to acquaintances in Mt. Hagen. However, from another point of view, the inadequacy of such an acknowledgement is patent: I am afraid that the acknowledgement will have to stand in for the personal credits due to many of the people who feature in the photographs that follow. And the puzzles to which I referred? Well, what is it that one sees?

Notes for the reader

A subject is of course as big as the time one takes to deal with it, but these four lectures always felt particularly constrained. Nonetheless, I do not take the opportunity of potentially limitless space to expand them now (in truth, that would only expand the constraint). Rather, I have kept more or less to what was spoken in an hour and, more or less, to their more-than-notes less-than-text form. I have added a few annotations in the text for current purposes. The constraint was an interesting one for the lecturer on the spot (interesting as in challenging), and intensified the ever-present sense of dissolving and reproducing puzzles at the same time. In restricting the elucidation to materials from Melanesia, the lectures opened wide the question of how to convey enough of sufficient breadth for those who knew little of the area, in order to develop arguments in at least some detail. For at the outset I wanted the lectures to do double work as a commentary, bringing to the fore what was in the background quite

approach to research, findings becoming first rated as outputs and then requiring the self-authentication of impacts. I say self-authentication since although impacts are supposedly all about the effects of research on definable others, they give academic work a credibility that may have little to do with its scholarship or contribution to a discipline and much more to do with practices of verification and presentation peculiar to the audit world. The students would not have had much sense of all that, but they would be able to seeby its apparent evocation of somewhere far away and long agothat this set of lectures was non-instrumentalist in terms of contemporary cannons of relevance. Or rather, that its instrumentalism was precisely to do with how one sees things how one argues, how writers organize their material, how to address assumptions, how indebted anthropologists are to their interlocutors, and so on, as a matter of nothing more, and nothing less, than the apparatus of intellectual training.

MARILYN STRATHERN

as much as attending to what was ostensibly foregrounded. Yet the lectures, in a way, took overand I think, had I articulated it at the end, I might then have suggested that the puzzle is not (only) what we need to know about the background, but how to see what to the EuroAmerican observer would appear as the very foreground. At the time I thought of this in simple terms as a matter of an ongoing dialogue with colleagues and the manner in which Melanesian materials found their way into the anthropological record, and in less obvious terms as a matter of dialogue with those who cannot see beyond feathers and paint. The initial point was that there was a background to be understood in relation to that state of cannot-see too. (I paid some attention to this in the first lecture, drawing on a photographers magnificent pictorial record, which had its own rationale but is here deployed very much for my own purposes; in the light of the comments on phenomena that outrun our grasp of them, I hope the pictorial images have lost none of their stature thereby.) I am not referring here to a horizon that the anthropologist is in a privileged position to scan, but to what that personage shares with any viewer or observer. This meant leaving the initial point behind. We could say that people not familiar with Melanesia do not know what they are seeing when they see a painted person decked out in feathers, leaves, and shells precisely because (and this is what they share with the anthropologist) people already do know what they see: they see feathers and paint. The issue of showing anything to be seen then becomes that of displacement: substituting one impression for another. Perhaps something not dissimilar to this motivates Melanesian display. So it seemed that maybe a way forward would be to contrive something not unlike Melanesians inveterate play on concealment and revelation. This would be in order to build some places and moments where a Euro-American student might be able to see the extent to which he or she hasnt seen what is in front of their eyes.

7

An oral format, and being able to stage a sequence of illustrations, are aids that a lecturer can exploit in the way a writer cannot. Much more so than a listener, an anthropological reader is of course used to seeing a text relate(d) to other texts. However, I have tried to keep the

7. For 1970s reflections on the provocative use of feathers and paint in Amazonia see Conklin (1997).

LECTURERS INTRODUCTION

immediacy of the original lecture format, less in terms of the way they (the lectures) were spoken and more in terms of forcing a focus on the material. This is not with any intent to hide anyones authorship, or the dispersed authorship of countless anthropological disquisitions for that matter, or the bias or controversy in the nature of the selections I made; it was a contrivance on my part to try to make the images do (some of) the work (of exposition). One consequence is that ordinary rules of exposition are truncated, in places drastically. Of course, it is never possible to prepare the grounds for everything one wants to say, but the saying wasnt the all of it. One reader of this introduction commented that there was an implicit analogy between two sets of relations: the relation between a more or less fixed format here and the ever changing character of other lectures I was giving at the time, on the one hand, and, on the other, the relation between the confined way these lectures were prepared for listeners and the potentialities that texts normally have for readers.

8

At the same time, the visual presentation of the images had their limitation, or rather, one may say they perpetually recreated the problem that I began with. I hoped for those following the oral lectures that the sequence of images on occasion illuminated switches in the way one might see things, but that of course depended on a temporal sequence that the reader of a text can ignore. However, the observation to make here is that the images (photographs by and large, some drawings and diagrams, but all static) repeatedly bring the viewer back to some kind of original standpoint. Whatever the subject, whether with people in or not, whether familiar or not, whether readable or not, an image is instantly absorbed. So you first see a man in bird feathers, and then you are told it is a man transformed, or is a man in the form (say) of a tree, or that it is the colors, not the feathers, that matter. It is as though an initial view, already taken, has to be dislodged, always again, each time. And the dislodging comes through another idiom (the verbal interpretation), as a kind of supplement. As a consequence, epistemologically speaking, the image is grasped as something that forever remains interpreted. Here, perhaps, the verbal displacements and innovations that can be

8. One example of a concept left hanging is given in the original rubric of the lectures that refers to the construction of knowledgeknowledge was occupying a space more like that of a signpost than an argument.

MARILYN STRATHERN

built up through a sustained text, one that creates its own context, can sustain a complexity of a kind that is constantly obviated in the kind of presentation given here. The title (Learning to see in Melanesia) had, in truth, a textual origin. This was in Anthony Forges description of how boys and men from Abelam, Papua New Guinea, acquire expectations about what they will see in flat, two-dimensional paintings displayed on the elevated faades of ceremonial houses. One outcome was their inability to interpret other two-dimensional images (as in photographs) outside the orbit of such paintings, for everything else would be threedimensional. It would have been wonderful to match his insights for the several materials presented here. They include many moments when Papua New Guineans are put into a position of not knowing what they are seeing, or ineffectually looking without seeing. However, the learning in my own title referred more to the student of anthropology than to participants on the spot. My eye was always on how the anthropologist built up a description. It was a matter of elucidating the categories of thought or apprehensionin Englishthat one would need to formulate in order to make such a description. This is less an issue of how to arrive at an appropriate interpretation of particular images than how to make oneself (as the observer, ethnographer, student) open to apprehending (some of) the effects such images might have. Anthony Forge (1970: 290) said as much in his concluding sentence: One of the main functions of the initiation system with its repetitive exposure of initiates to quantities of art is, I would suggest, to teach the young m[a]n to see the art, not so that he may consciously interpret it but so he is directly affected by it.

9

Descriptive categories are not trivial. Old colonial (Australian) slang for mens rear covering used the Pidgin English term for grass, perhaps on an analogy with grass skirts. Across the Papua New Guinea Highlands people did indeed wear front and back coverings, some of which can be called skirts, the once invariable styles now reserved for special occasions. However, in certain areas (including Mt. Hagen in the Western Highlands) the colonial and humorous / nasty-matey shorthand for mens grass coverings was always a misnomer. They were not made of grass, and in any case what they

9. The lectures were not intended to deal with the physiology or psychology of sight.

LECTURERS INTRODUCTION

are made of is only part of their significance or interest. Better look again.

10

* * *

Note: Square brackets indicate points of clarification added in this version of the lectures. Italics indicate the text, often in note form, of parts of the lectures that might or might not have been delivered, depending on time.

* * *

10. Though it should be noted that the Pidgin gras had a wider range of referents than the English term. As across the Western Highlands, Hagen men wore bustles made from cordyline leaves. [Ragnar Johnson (2001) shows Ommura men and women from the Eastern Highlands dancing at Independence Day celebrations in 1975 wearing grass skirts on the lower body, whose substance look a little like the tall grass from which thatch is made for houses. Maureen Mackenzie (1990) refers to grass skirts in Telefolmin, worn by girls and women (see Lecture Three). There are other examples, although it should also be said that string skirts woven from bark or other fiber might have the appearance of grass from a distance.]

10

MARILYN STRATHERN

Original outline and reading list for the course

[Original rubric.] These lectures take up a number of artifacts for examination and theorization; they are ones specifically made to be seen. Euro-Americans often point to the construction of knowledge when they say they see things. But what about other visual intentions? Here the lectures have an identifiable set of coordinates in space and time: material drawn from one ethnographic region (Melanesia), and from ethnographies produced at about the same time together (1970s80s), enable one to build up an appreciation of a visual theory that challenges certain enduring Euro-American preconceptions.

11

(1) FEATHERS AND SHELLS: Learning to see. How do we know what we see? Ceremonial exchange and the possibility of an indigenous visual theory.

Forge, Anthony. 1966. Art and environment in the Sepik. Proceedings of the Royal Anthropological Institute for 1965, 2331. London: Royal Anthropological Institute. . 1970. Learning to see in New Guinea. In Socialization: The approach from social anthropology, edited by Philip Mayer, 26990. London: Tavistock. [Abelam]

The New Guinea Highlands:

Biersack, Aletta. 1982. Ginger gardens for the ginger woman. Man 17: 23958 [Paiela] Gillison, Gillian. 1980. Images of nature in Gimi thought. In Nature, culture, and gender, edited by Carol MacCormack and Marilyn Strathern, 14373. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. . 1993. Between culture and fantasy: A New Guinea Highlands mythology. Chicago: Chicago University Press. [Gimi] Kirk, Malcom. 1981. Man as art. New York: Viking Press OHanlon, Michael. 1983. Handsome is as handsome does. Oceania 53: 31733.

11. One or two later readings were added to indicate continuing debate.

LECTURERS INTRODUCTION

11

. 1989. Reading the skin: Adornment, display and society among the Wahgi. London: British Museum Press. . 1995. Modernity and the graphicalization of meaning: New Guinea Highland shield design in historical perspective. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 1: 46993. [Wahgi] Strathern, Andrew and Marilyn Strathern. 1971. Self-decoration in Mt. Hagen. London: Duckworth. [Hagen] Strathern, Marilyn. 1979. The self in self-decoration. Oceania 49: 241 57. . 1997. Pre-figured features. In Portraiture: Facing the subject, edited by Joanna Woodall, 25968. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Reprinted in Strathern, Marilyn. 1999. Property, substance and effect: Anthropological essays on persons and things, 2944. London: Athlone.] [Hagen]

Compare:

Astuti, Rita. 1994. Invisible objects: Mortuary rituals among the Vezo of western Madagascar. RES: Anthropology & Aesthetics 25: 111-22. [Vezo, Madagascar] Gell, Alfred. 1998. Art and agency: An anthropological theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

(2) AXES AND CANOES: Traveling objects. Ideas of mobility and fixity in human relationships. How specific artifacts carry relations. Rituals as a focus for dispersed life.

The Massim:

Battaglia, Debbora. 1983. Projecting personhood in Melanesia: The dialectics of artefact symbolism on Sabarl Island. Man 18: 289304. . 1990. On the Bones of the serpent: Person, memory, and mortality in Sabarl Island society. Chicago: Chicago University Press. . 1992. The body in the gift: Memory and forgetting in Sabarl mortuary exchange. American Ethnologist 19: 318.] [Sabarl Island] Leach, Edmund and Jerry W. Leach, eds. 1983. The Kula: New perspectives on Massim exchange. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [See esp., Chapters 8 and 9.]

12

MARILYN STRATHERN

Munn, Nancy. 1986. The fame of Gawa: A symbolic study of value transformation in a Massim (Papua New Guinea) society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [See esp., pp. 10514; 13847.] Young, Michael. 1987. The tusk, the flute and the serpent: Disguise and revelation in Goodenough mythology. In Dealing with inequality: Analysing gender relations in Melanesia and beyond, edited by Marilyn Strathern. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Goodenough Island]

Compare:

Campbell, Shirley. 2001. The captivating agency of art: many ways of seeing. In Beyond aesthetics: Art and the technologies of enchantment, edited by Christopher Pinney and Nicholas Thomas, 11735. Oxford: Berg. . 2002. The art of kula. Oxford: Berg. [Massim] Kchler, Susanne. 2002. Malanggan: Art, memory and sacrifice. Oxford: Berg. [New Ireland]

(3) NETBAGS AND MASKS: Containers. Persons inside other persons. Borrowing power and stealing power. Concealment and revelation as aesthetic and reproductive acts.

Sepik and Mt. Ok areas:

Barth, Frederik. 1987. Cosmologies in the making: A generative approach to cultural variation in Inner New Guinea. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Mountain Ok] Gell, Alred, 1975. Metamorphosis of the cassowaries: Umeda society, language and ritual. London: Athlone. [Umeda] Mackenzie, Maureen. 1990. The Telefol string bag: A cultural object with androgynous forms. In Children of Afek: Tradition and change among the Mountain-Ok of central New Guinea, edited by Barry Craig and David Hyndman, 88108. Sydney: Oceania Monographs No. 40. . 1991. Androgynous objects: String bags and gender in central New Guinea. New York: Gordon & Breach. [Mountain Ok] Strathern, Marilyn. 1991. Partial Connections. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. [See esp., pp. 7990.]

LECTURERS INTRODUCTION

13

Werbner, Richard. 1989. Ritual passage, sacred journey: The process and organization of religious movement. Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Institution Press. [See esp., Chapters 4 and 5.] . 1992. On dialectical versions: The cosmic rebirth of West Sepik regionalism. In Shooting the Sun: Ritual and meaning in West Sepik, edited by Bernard Juillerat, 21450. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press. [Umeda]

Compare:

Hauser-Schublin, Brigitta. 1996. The thrill of the line, the string, and the frond, or why the Abelam are a non-cloth culture. Oceania 67 (2): 81106. [Abelam] Kchler, Susanne. 2005. Materiality and cognition: The changing face of things. In Materiality, edited by Daniel Miller. Durham: Duke University Press. [New Ireland]

(4) WIG / SHELL / TREE: Hiding forms. Multiple forms, ambiguous images: play with perception and the framing of images. Invention and innovation.

Highlands, coastal, and island PNG:

Clark, Jeffrey. 1991. Pearlshell symbolism in Highlands Papua New Guinea, with particular reference to the Wiru people of Southern Highlands Province. Oceania 61 (4): 30939. . 1995. Shit beautiful: Tambu and kina revisited. Oceania 65 (3): 195211. [Wiru] Feld, Steven. 1982. Sound and sentiment: Birds, weeping, poetics, and song in Kaluli expression. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Third Edition, 2012. Durham: Duke University Press.] [Kaluli] Foster, Robert. 1990. Nurture and force feeding: Mortuary feasting and the construction of collective individuals in a New Ireland society. American Ethnologist 17 (3): 43148. [Tanga] Goldman, Laurence. 1983. Talk never dies: The language of Huli disputes. London: Tavistock. [See esp., pp 23445.] [Huli] Schieffelin, Edward. 1976. The sorrow of the lonely and the burning of the dancers. New York: St Martins Press. [Kaluli]

14

MARILYN STRATHERN

Wagner, Roy. 1987. Figure-ground reversal among the Barok. In Assemblage of spirits: Idea and image in New Ireland, edited by Louise Lincoln, 5662. Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts. [Reprinted in 2012. HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 2(1): 535 42] . 1986. Asiwinarong: Ethos, image and social power among the Usen Barok of New Ireland. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [See esp., Chapters 7 and 8.] [Barok] Weiner, James. 1988. The heart of the pearlshell: The mythological dimension of Foi sociality. Berkeley: University of California Press. [See esp., pp. 6377.] [Foi]

Compare:

Dalton, Douglas. 1996. The aesthetic of the sublime: An interpretation of Rawa shell valuable symbolism. American Ethnologist 23 (2): 393415. [Rawa] Demian, Melissa. 2004. Seeing, knowing, owning: Property claims as revelatory acts. In Transactions and creations: Property debates and the stimulus of Melanesia, edited by Eric Hirsch and Marilyn Strathern, 6082. Oxford: Berghahn. [Suau, Massim]

Additional bibliography

Conklin, Beth. 1997. Body paint, feathers, and vcrs: Aesthetics and authenticity in Amazonian activism. American Ethnologist 24 (4): 71137 Rabinow, Paul, et al. 2008. Designs for an anthropology of the contemporary. Durham: Duke University Press. Johnson, Ragnar. 2001. The anthropological study of body decoration as art: Collective representations and the somatization of affect. Fashion Theory 5 (4): 41734 Wagner, Roy. 2011. Vj de and the quintessentialists guild. Common Knowledge 17 (1): 159 Viveiros de Castro, Eduardo. 2003. And: After-dinner speech given at Anthropology and science, the fifth decennial conference of the Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth. Manchester: Manchester Papers in Social Anthropology, Vol. 7.

L ECTURER S A CKNOW LEDGMENTS

While I add my personal gratitude to all the publishers, and in some cases authors, who have so kindly allowed illustrations to be reproduced here, I must reserve special thanks for Malcolm Kirk for his generosity in sharing his images; he brings from the art world a quite distinctive perspective, and to be able to see these images again is not at all of the same order as looking at any of the other illustrations, fine as many are. In thanking the HAU team for their splendid work, I am particularly grateful to the contribution that Phil Swift and Sean Dowdy have made to the presence and presentation of the reproductions and to the flow of the text. The team at HAU who have given so generously of their time and expertise include Davide Casciano (IT and website); Sean Dowdy (copyediting and layout); Stphane Gros (technical supervision); Teodora Hasegan (proofreading); Randolph Mamo (cover and imagerelated work) and Philip Swift (copyright and permission work, imagerelated work). My gratitude to them all, and to Giovanni da Col for the invitation to publish these lectures in the HAU Masterclass series, and the unwavering encouragement on his part that accompanied it. I have already indicated my debt to acquaintances in Papua New Guinea, and add too the many I did not know but who have contributed to these lectures. Perhaps I can also acknowledge here the generations of students without whose interest they would not have been given.

A CKNOW LEDGMENTS

TO PUBLISHERS

AND AUTHORS

Figures 111, 16, and 68. From Kirk, Malcom. 1981. Man as art, New York: Viking Press. Photographs: Malcom Kirk. Malcolm Kirk. Reproduced with permission of the author. Figures 1215, 1739, 42, 43, 60, 67, and 81. Photographs: Marilyn Strathern. Figures 40 and 41. From Polhemus, Ted and Lynn Procter. 1978. Fashion and anti-fashion: An anthropology of clothing and adornment. London: Thames and Hudson. Photograph: Author / copyright holder unknown. Figure 44. From Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1922. Argonauts of the Western Pacific. London: George Routledge and Sons, Ltd. Reproduced with publishers permission. Figure 45. From Munn, Nancy. 1986. The fame of Gawa: A symbolic study of value transformation in a Massim (Papua New Guinea) society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Photograph: Nancy D. Munn. Reproduced with permission of the author.

Editors note: Every effort has been made to obtain permission for the reproduction of copyrighted images. HAU would be very glad to hear from any copyright holders not acknowledged herein.

18

Marilyn STRATHERN

Figure 46. From Scoditti, Giancarlo G. 1980. Fragmenta ethnographica. Rome: Serafine Editore. Photograph: Giancarlo Scoditti. Reproduced with permission of the author. Figures 47 and 48. From Campbell, Shirley. 2002. The art of Kula. Oxford: Berg. Reproduced with permission of the author. Figures 49, 50, 52 and 53. From Battaglia, Debbora. 1990. On the bones of the serpent: Person, memory and mortality in Sabarl Island society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Reproduced with publishers permission. Figure 51. From Figure 5, Diagram of the measured view. Drawn by Carolyn Van Lang, in Starn, Randolph. 1989. Seeing Culture in a Room for a Renaissance Prince. In The new cultural history, edited by Lynn Hunt, 20534. Berkeley: University of California Press. by the Regents of the University of California. Reproduced with publishers permission. Figures 5459. From Mackenzie, Maureen. 1991. Androgynous objects: String bags and gender in central New Guinea. Gordon & Breach. Reproduced with permission of the author. Figure 61. From Schmitz, Carl. 1963. Wantoat: Art and religion of the northeast New Guinea Papuans. The Hague: Mouton & Co. Reproduced with publishers permission. Figure 62. From Heintze, Diete. 1987. On trying to understand some Malagans. In Assemblage of spirits: Idea and image in New Ireland, edited by Louise Lincoln, 4255. Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts / George Braziller, Inc. Photograph: Dieter Heintze. Reproduced with publishers permission. Figure 63. From Clay, Brenda. 1987. A line of Tatanua. In Assemblage of spirits: Idea and image in New Ireland, edited by Louise Lincoln, 6373. Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts / George Braziller, Inc. Photograph: Brenda Clay. Reproduced with publishers permission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS TO PUBLISHERS AND AUTHORS

19

Figures 6466. From Gell, Alfred. 1975. Metamorphosis of the cassowaries: Umeda society, language, and ritual. London: Athlone Press. Drawn by Alfred Gell. Reproduced with permission of Simeran Gell. Figure 69. Photograph: Author / copyright holder unknown. Figures 70 and 71. From Goldman, Laurence. 1983. Talk never dies: The language of Huli disputes. London: Tavistock. Reproduced with permission of the author. Figures 72 and 73. From Clark, Jeffrey. 1991. Pearlshell symbolism in highlands Papua New Guinea, with particular reference to the Wiru people of Southern Highlands Province. Oceania 61 (4): 309 39. Reproduced with publishers permission. Figures 74 and 75. From Roy Wagner, Roy. 1987. Figure-ground reversal among the Barok. In Assemblage of spirits: Idea and image in New Ireland, edited by Louise Lincoln, 5662. Minneapolis: Minneapolis Institute of Arts / George Braziller, Inc. Drawn by Roy Wagner. Reproduced with publishers permission. Figures 76 and 77. From Feld, Steven. (1982) 2012. Sound and sentiment: Birds, weeping, poetics, and song in Kaluli expression. Durham: Duke University Press. Photographs: Steven Feld. Steven Feld. Reproduced with permission of the author. Figure 78. From Gillison, Gillian. 1980. Images of nature in Gimi thought. In Nature, culture and gender, edited by Carol MacCormack and Marilyn Strathern, 14373. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Photograph: David Gillison. Reproduced with publishers permission. Figures 79 and 80. From Nilsson, Lennart. 1990. A child is born. New York and London: Doubleday. Reproduced with publishers permission.

You might also like

- The Mantle of the Earth: Genealogies of a Geographical MetaphorFrom EverandThe Mantle of the Earth: Genealogies of a Geographical MetaphorNo ratings yet

- Temporal Dimension Summary ArnavDocument7 pagesTemporal Dimension Summary Arnavarnav saikia67% (3)

- How Novels Think: The Limits of Individualism from 1719-1900From EverandHow Novels Think: The Limits of Individualism from 1719-1900No ratings yet

- Naturalness: Is the “Natural” Preferable to the “Artificial”?From EverandNaturalness: Is the “Natural” Preferable to the “Artificial”?No ratings yet

- Speaking Hermeneutically: Understanding in the Conduct of a LifeFrom EverandSpeaking Hermeneutically: Understanding in the Conduct of a LifeNo ratings yet

- Envisioning Eden: Mobilizing Imaginaries in Tourism and BeyondFrom EverandEnvisioning Eden: Mobilizing Imaginaries in Tourism and BeyondNo ratings yet

- Moment to Monument: The Making and Unmaking of Cultural SignificanceFrom EverandMoment to Monument: The Making and Unmaking of Cultural SignificanceLadina Bezzola LambertNo ratings yet

- Europe, or The Infinite Task: A Study of a Philosophical ConceptFrom EverandEurope, or The Infinite Task: A Study of a Philosophical ConceptRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Reasoning from Faith: Fundamental Theology in Merold Westphal's Philosophy of ReligionFrom EverandReasoning from Faith: Fundamental Theology in Merold Westphal's Philosophy of ReligionNo ratings yet

- Inheriting the Future: Legacies of Kant, Freud, and FlaubertFrom EverandInheriting the Future: Legacies of Kant, Freud, and FlaubertNo ratings yet

- Philanthropic Discourse in Anglo-American Literature, 1850–1920From EverandPhilanthropic Discourse in Anglo-American Literature, 1850–1920Frank Q. ChristiansonNo ratings yet

- Tropological Thought and Action: Essays on the Poetics of ImaginationFrom EverandTropological Thought and Action: Essays on the Poetics of ImaginationMarko ŽivkovićNo ratings yet

- Retellings: Opportunities for Feminist Research in Rhetoric and Composition StudiesFrom EverandRetellings: Opportunities for Feminist Research in Rhetoric and Composition StudiesNo ratings yet

- Strange Words: Retelling and Reception in the Medieval Roland Textual TraditionFrom EverandStrange Words: Retelling and Reception in the Medieval Roland Textual TraditionNo ratings yet

- Asubjective PhenomenologyFrom EverandAsubjective PhenomenologyĽubica UčníkNo ratings yet

- Clarissa Harlowe; or the history of a young lady — Volume 1From EverandClarissa Harlowe; or the history of a young lady — Volume 1No ratings yet

- The Limitations of Social Media Feminism: No Space of Our OwnFrom EverandThe Limitations of Social Media Feminism: No Space of Our OwnNo ratings yet

- Transplanting the Metaphysical Organ: German Romanticism between Leibniz and MarxFrom EverandTransplanting the Metaphysical Organ: German Romanticism between Leibniz and MarxNo ratings yet

- Essays On Pragmatic Naturalism: Discourse Relativity, Religion, Art, and EducationFrom EverandEssays On Pragmatic Naturalism: Discourse Relativity, Religion, Art, and EducationNo ratings yet

- The Funeral Casino: Meditation, Massacre, and Exchange with the Dead in ThailandFrom EverandThe Funeral Casino: Meditation, Massacre, and Exchange with the Dead in ThailandNo ratings yet

- If Babel Had a Form: Translating Equivalence in the Twentieth-Century TranspacificFrom EverandIf Babel Had a Form: Translating Equivalence in the Twentieth-Century TranspacificNo ratings yet

- Unsettling Nature: Ecology, Phenomenology, and the Settler Colonial ImaginationFrom EverandUnsettling Nature: Ecology, Phenomenology, and the Settler Colonial ImaginationNo ratings yet

- Osiris, Volume 31: History of Science and the EmotionsFrom EverandOsiris, Volume 31: History of Science and the EmotionsOtniel E. DrorNo ratings yet

- Meaning, Truth, and Reference in Historical RepresentationFrom EverandMeaning, Truth, and Reference in Historical RepresentationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Totality Inside Out: Rethinking Crisis and Conflict under CapitalFrom EverandTotality Inside Out: Rethinking Crisis and Conflict under CapitalNo ratings yet

- Environment and Post-Soviet Transformation in Kazakhstan’s Aral Sea Region: Sea changesFrom EverandEnvironment and Post-Soviet Transformation in Kazakhstan’s Aral Sea Region: Sea changesNo ratings yet

- Locating Lynette Roberts: ‘Always Observant and Slightly Obscure'From EverandLocating Lynette Roberts: ‘Always Observant and Slightly Obscure'Siriol McAvoyNo ratings yet

- Transcendence and Inscription: Jacques Derrida on Ethics, Religion and MetaphysicsFrom EverandTranscendence and Inscription: Jacques Derrida on Ethics, Religion and MetaphysicsNo ratings yet

- The Politics of Survival: Peirce, Affectivity, and Social CriticismFrom EverandThe Politics of Survival: Peirce, Affectivity, and Social CriticismNo ratings yet

- Wittgensteins Remarks on Colour: A Commentary and InterpretationFrom EverandWittgensteins Remarks on Colour: A Commentary and InterpretationNo ratings yet

- Feelings Materialized: Emotions, Bodies, and Things in Germany, 1500–1950From EverandFeelings Materialized: Emotions, Bodies, and Things in Germany, 1500–1950Derek HillardNo ratings yet

- Culture and RhetoricFrom EverandCulture and RhetoricIvo StreckerNo ratings yet

- Unguessed Kinships: Naturalism and the Geography of Hope in Cormac McCarthyFrom EverandUnguessed Kinships: Naturalism and the Geography of Hope in Cormac McCarthyNo ratings yet

- The Public Work of Rhetoric: Citizen-Scholars and Civic EngagementFrom EverandThe Public Work of Rhetoric: Citizen-Scholars and Civic EngagementNo ratings yet

- Nature Speaks: Medieval Literature and Aristotelian PhilosophyFrom EverandNature Speaks: Medieval Literature and Aristotelian PhilosophyNo ratings yet

- Rivière Peter O Indivíduo e A Ociedade Na Guiana Cap. 7 - e - 8 PDFDocument21 pagesRivière Peter O Indivíduo e A Ociedade Na Guiana Cap. 7 - e - 8 PDFSonia Lourenço100% (1)

- Gow - An Amazonian Myth and Its History PDFDocument182 pagesGow - An Amazonian Myth and Its History PDFSonia Lourenço100% (3)

- Seremetakis - The Memory of The SensesDocument17 pagesSeremetakis - The Memory of The SensesSonia Lourenço100% (1)

- Gabal PerformanceDocument25 pagesGabal PerformanceSonia LourençoNo ratings yet

- Upper Rio Negro Cultural and Linguistic PDFDocument290 pagesUpper Rio Negro Cultural and Linguistic PDFCamila FrancoNo ratings yet

- Fassin Biopolitics (2015 - 04 - 04 17 - 01 - 34 UTC)Document6 pagesFassin Biopolitics (2015 - 04 - 04 17 - 01 - 34 UTC)Emilio NocedalNo ratings yet

- Wagner - Are There Social Groups in New GuineaDocument28 pagesWagner - Are There Social Groups in New GuineaFlora GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- DA COL, Giovanni. On Topology, Ethnographic Theory, and The Method of Wonder PDFDocument10 pagesDA COL, Giovanni. On Topology, Ethnographic Theory, and The Method of Wonder PDFSonia LourençoNo ratings yet

- Dogon Cosmology - Griaule Et AlDocument28 pagesDogon Cosmology - Griaule Et AlJulian West100% (1)

- Bruno Latour and The Anthropology of The ModernsDocument13 pagesBruno Latour and The Anthropology of The ModernsSonia Lourenço100% (1)

- Balinese Character A Photographic AnalysisDocument290 pagesBalinese Character A Photographic AnalysisSonia LourençoNo ratings yet

- Hau CompletaDocument259 pagesHau CompletaSonia LourençoNo ratings yet

- Surinameiachrsaramakajudgmentnov 07 EngDocument63 pagesSurinameiachrsaramakajudgmentnov 07 EngSonia LourençoNo ratings yet

- SOAL AKM Contoh HOTSDocument2 pagesSOAL AKM Contoh HOTSUtarii NurhayatiNo ratings yet

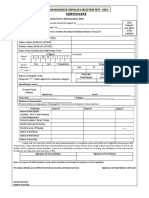

- Application Form For Admission PDFDocument2 pagesApplication Form For Admission PDFmark louie colandogNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument21 pagesLesson PlanAbegailNo ratings yet

- Company Profile: University: Nature and DescriptionDocument7 pagesCompany Profile: University: Nature and DescriptionWilly WonkaNo ratings yet

- Women in Tourism - Realities, Dilemmas and OpportunitiesDocument7 pagesWomen in Tourism - Realities, Dilemmas and OpportunitiesEquitable Tourism Options (EQUATIONS)100% (2)

- Influencing Factors of Cosplay To The Negrense YouthDocument44 pagesInfluencing Factors of Cosplay To The Negrense YouthMimiNo ratings yet

- Effects of Social Media On Interpersonal Communication of First Year Engineering Students of de La Salle University-DasmariñasDocument23 pagesEffects of Social Media On Interpersonal Communication of First Year Engineering Students of de La Salle University-DasmariñasJohn Joselle Macaspac67% (3)

- June Accom. ReportDocument1 pageJune Accom. ReportNikkoNo ratings yet

- Today PhilosophyDocument5 pagesToday PhilosophyGeorgy PlekhanovNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Amsco First Civilizations - Griffin HowellDocument27 pagesChapter 2 Amsco First Civilizations - Griffin HowellgriffinNo ratings yet

- Tariq Modood Et All (Eds.) - Tolerance, Intolerance and Respect - Hard To Accept - Palgrave Macmillan UK (2013)Document264 pagesTariq Modood Et All (Eds.) - Tolerance, Intolerance and Respect - Hard To Accept - Palgrave Macmillan UK (2013)Dailan KifkiNo ratings yet

- INsight YOUng 20X21 BookDocument90 pagesINsight YOUng 20X21 Bookrohit100% (1)

- Open Clearning ScriptDocument3 pagesOpen Clearning ScriptCHRISTIAN BUYOCNo ratings yet

- DRF Brief2018 1Document4 pagesDRF Brief2018 1api-356772067No ratings yet

- 01 c1 Set 1 Que 1204-511 Paragraph Headings PDFDocument2 pages01 c1 Set 1 Que 1204-511 Paragraph Headings PDFTanító TanulóNo ratings yet

- Question List - Purpose of Trip To Usa: Gummadi Educational Consultants, 4Document25 pagesQuestion List - Purpose of Trip To Usa: Gummadi Educational Consultants, 4Sampath Kumar GummadiNo ratings yet

- Lexilogus A Critical Examination of The Meaning and Etymology of Numerous Greek WordsDocument622 pagesLexilogus A Critical Examination of The Meaning and Etymology of Numerous Greek WordstepaabvNo ratings yet

- CV Adrian MailoorDocument1 pageCV Adrian MailoorAdrian MailoorNo ratings yet

- A Rough Guide To Gypsies and TravellersDocument24 pagesA Rough Guide To Gypsies and TravellersJames Barlow0% (1)

- Clinical Legal EducationDocument7 pagesClinical Legal EducationLalit Kumar Reddy0% (1)

- Things Fall Apart AnalysisDocument10 pagesThings Fall Apart Analysistaurai oliverNo ratings yet

- Navodaya Application FormDocument1 pageNavodaya Application Formphanidatta vNo ratings yet

- Narrative Report Inset Summer 2017Document4 pagesNarrative Report Inset Summer 2017Edrin Roy Cachero SyNo ratings yet

- Real Development Should Transform PeoplesDocument2 pagesReal Development Should Transform PeoplesArshad UsmanNo ratings yet

- Doskvol AcademiaDocument1 pageDoskvol AcademiaAnonymous rIYNcDwlkKNo ratings yet

- Hancart Petitet CV Ang Juil 2010Document5 pagesHancart Petitet CV Ang Juil 2010pascalehpNo ratings yet

- Origin and Development of Modern Arabic LiteratureDocument3 pagesOrigin and Development of Modern Arabic LiteratureNajam Hassan Khan SialNo ratings yet

- Imago Dei, and The Sanctity of Human Life, Robert Barry - ArticleDocument39 pagesImago Dei, and The Sanctity of Human Life, Robert Barry - ArticlePishoi ArmaniosNo ratings yet

- Mary Joy B. Beato: AccountantDocument4 pagesMary Joy B. Beato: AccountantStefanie FerminNo ratings yet