The Firebird's Nest

The Firebird's Nest

Uploaded by

Anca FilipCopyright:

Available Formats

The Firebird's Nest

The Firebird's Nest

Uploaded by

Anca FilipOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

The Firebird's Nest

The Firebird's Nest

Uploaded by

Anca FilipCopyright:

Available Formats

Salman Rushdie

1 THE FIREBIRDS NEST

Now I am ready to tell how bodies are changed Into different bodies. Ovid, The Metamorphoses, translated by Ted Hughes

IT IS A hot place, flat and sere. The rains have failed so often that now they say instead, the drought succeeded. They are plainsmen, livestock farmers, but their cattle are deserting them. The cattle, staggering, migrate south and east in search of water, and rattle as they walk. Their skulls, horned mileposts, line the route of their vain exodus. There is water to the west, but it is salt. Soon even these marshes will have given up the ghost. Tumbleweed blows across the leached grey flats. There are cracks big enough to swallow a man. An apt enough way for a farmer to die: to be eaten by his land. Women do not die in that way. Women catch fire, and burn. Within living memory, a thick forest stood here, Mr Maharaj tells his American bride as the limousine drives towards his palace. A rare breed of tiger lived in the forest, white as salt, wiry, small. And songbirds! A dozen dozen varieties; their very nests were built of music. Half a century ago, his father riding through the forest would hum along with their arias, could hear the tigers joining in the choruses. But now his father is dead, the tigers are extinct, and the birds have all gone, except one, which never sings a note, and, in the absence of trees, makes its nest in a secret place that has not been revealed. The firebird, he whispers, and his bride, a child of a big city, a foreigner, no virgin, laughs at such exotic melodramatics, tossing her long bright hair; which is yellow, like a flame. There are no princes now. The government abolished them decades ago. The very idea of princes has become, in our modern country, a fiction, something from the time of feudalism, of fairy-tale. Their titles, their privileges have been stripped from them. They have no power over us. In this place, the prince has become plain Mr Maharaj. He is a complex man. His palace in the city has become a casino, but he heads a commission that seeks to extirpate the public corruption that is the countrys bane. In his youth he was a mighty sportsman, but since his retirement he has had no time for games. He heads an ecological institute, studying, and seeking remedies for, the drought; but at his country residence, at the great fortress-palace to which this limousine is taking him, cascades of precious water flow ceaselessly, for no other purpose than display. His library of ancient texts is the wonder of the province, yet he also controls the local satellite franchises, and profits from every new dish. The details of his finances, like those of his many rumoured romances, are obscure. Here is a quarry. The limousine halts. There are men with pickaxes and women bearing earth in metal bowls upon their heads. When they see Mr Maharaj they make gestures of respect, they genuflect, they bow. The American bride, watching, intuits that she has passed into a place in which that which was abolished is the truth, and it is the government, far away in the capital, that is the fiction in which nobody believes. Here Mr Maharaj is still the prince, and she, his new princess. As though she had entered a fable, as though she were no more than words crawling along a dry page, or as though she were becoming that page itself, that surface on which her story would be written, and across which there blew a hot and merciless wind, turning her body to papyrus, her skin to parchment, her soul to paper.

Salman Rushdie

It is so hot. She shivers. It is no quarry. It is a reservoir. Farmers, driven from their land by drought, have been employed by Mr Maharaj to dig this water-hole against the day when the rains return. In this way he can give them some employment, he tells his bride, and more than employment: hope. She shakes her head, seeing that this great hollow is already full; of bitter irony. Briny, brackish, no use to man or cow. The women in the reservoir of irony are dressed in the colours of fire. Only the foolish, blinded by languages conventions, think of fire as red, or gold. Fire is blue at its melancholy rim, green in its envious heart. It may burn white, or even, in its greatest rages, black. Yesterday, the men with pickaxes tell Mr Maharaj, a woman in a red and gold sari, a fool, ignited in the amphitheatre of the dry water-hole. The men stood along the high rim of the reservoir, watching her burn, shouldering arms in a kind of salute; recognizing, in the wisdom of their manhood, the inevitability of womens fate. The women, their women, screamed. When the woman finished burning there was nothing there. Not a scrap of flesh, not a bone. She burned as paper burns, flying up to the sky and being blown into nothing by the wind. The combustibility of women is a source of resigned wonder to the men hereabouts. They just burn too easily, whats to be done about it? Turn your back and theyre alight. Perhaps it is a difference between the sexes, the men say. Men are earth, solid, enduring, but the ladies are capricious, unstable, they are not long for this world, they go off in a puff of smoke without leaving so much as a note of explanation. And in this heat, if they should spend too long in the sun! We tell them to stay indoors, not to expose themselves to danger, but you know how women are. It is their fate, their nature. Even the demure ones have fiery hearts; perhaps the demure ones most of all, Mr Maharaj murmurs to his wife in the limousine. She is a woman of modern outlook and does not like it, she tells him, when he speaks this way, herding her sex into these crude corrals, these easy generalizations, even in jest. He inclines his head in amused apology. A firebrand, he says. I see I must mend my ways. See that you do, she commands, and nestles comfortably under his arm. His grey beard brushes her brow. Gossip burns ahead of her. She is rich, as rich as the old, obese Nizam of , who was weighed in jewels on his birthdays and so was able to increase taxes simply by putting on weight. His subjects would quake as they saw his banquets, his mighty halvas, his towering jellies, his kulfi Himalayas, for they knew that the endless avalanche of delicacies sliding down the Nizams gullet meant that the food on their own tables would be sparse and plain; as he wept with exhausted repletion so their children would weep with hunger, his gluttony would be their famine. Yes, filthy rich, the gossip sizzles, her American father claims descent from the deposed royal family of an Eastern European state, and each year he flies the elite employees of his commercial empire by private aircraft to his lost kingdom, where by the banks of the River of Time itself he stages a four-day golf tournament, and then, laughing, contemptuous, godlike, fires the champion, destroys his life for the hubris of aspiring to glory, abandons him by the shores of Times River, into whose tumultuous, deadly waters the champion finally dives, and is lost, like hope, like a ball. She is rich; she is a fertile land; she will bring sons, and rain. No, she is poor, the gossip flashers, her father hanged himself when she was born, her mother was a whore, she also is a creature of wilderness and rocky ground, the drought is in her body, like a curse, she is barren, and has come in the hope of stealing brown babies from their homes and nursing them with bottles, since her own breasts are dry. Mr Maharaj has searched the world for its treasures and brought back a magic jewel whose light will change their lives. Mr Maharaj has fallen into iniquity and brought Despair into his palace, has succumbed to yellow-haired doom.

Salman Rushdie

So she is becoming a story the people tell, and argue over. Travelling towards the palace, she too is aware of entering a story, a group of stories about women such as herself, fair and yellow, and the dark men they loved. She was warned by friends at home, in her tall city. Do not go with him, they cautioned her. If you sleep with him, he will not respect you. He does not think of women like you as wives. Your otherness excites him, your freedom. He will break your heart. Though he calls her his bride, she is not his wife, So far, she feels no fear. A ruined gateway stands in the wilderness, an entrance to nowhere. A single tree, the last of all the local trees to fall, lies rotting beside it, the exposed roots grabbing at air like a dead giants hand. A wedding party passes, and the limousine slows. She sees that the turbaned groom, on his way to meet his wife, is not young and eager, but wispy-haired, old and parched; she imagines a tale of undying love, long denied by circumstance, overcoming adversity at last. Somewhere an elderly sweetheart awaits her wizened amour. They have loved each other always, she imagines, and now near their stories conclusion they have found this happy ending. By accident she speaks these words aloud. Mr Maharaj smiles, and shakes his head. The bridegrooms bride is young, a virgin from a distant village. Why would a pretty young girl wish to marry an old fool? Mr Maharaj shrugs. The old fellow will have settled for a small dowry, he replies, and if one has many daughters such factors have much weight. As for the oldster, he adds, in a long life there may be more than a single dowry. These things add up. Flutes and horns blow raucous music in her direction. A drum crumps like cannon-fire. Transsexual dances heckle her through the window. Oh, America, they screech, arr, howdy-podner, say what? OK, you take care now, Im-a-yankee-doodle-dandy! Ooh, baby, wah-wah, maximum cool, Miss America, shake that thing! She feels a sudden panic. Drive faster, she cries, and the driver accelerates. Dust explodes around the wedding party, hiding it from view. Mr Maharaj is solicitude personified, but she is angry with herself. Excuse me, she mutters. Its nothing. The heat. (America. Once upon a time in America, they had shared an Indian lunch three hundred feet above street-level, at a table with a view of the vernal lushness of the park, feasting their eyes upon an opulence of vegetation which now, as she remembers it in this desiccated landscape, feels obscene. My country is just like yours, hed said, flirting. Big, turbulent and full of gods. We speak our kind of bad English and you speak yours. And before you became Romans, when you were just colonials, our masters were the same. You defeated them before we did. So now you have more money than we do. Otherwise, were the same. On your street corners the same bustle of differences, the same litter, the same every-thing-at-onceness. She guessed immediately what he was telling her: that he came from a place unlike anything she had ever experienced, whose languages she would struggle to master, whose codes she might never break, and whose immensity and mystery would provoke and fulfil her greatest passion and her deepest need. Because she was an American, he spoke to her of money. The old protectionist legislation, the outdated socialism that had hobbled the economy for so long, had been repealed and there were fortunes to be made if you had the ideas. Even a prince had to be on the ball, one step ahead of the game. He was bursting with projects, and she had a reputation in financial circles as a person who could bring together capital and ideas, who could conjure up, for her favoured projects, the monetary nourishment they required. A rainmaker. She took him to the opera, was aroused, as always, by the power of great matters sung of in words she could not understand, whose meaning had to be inferred from the performers deeds. Then she took him home and seduced him. It was her city, her stage, and she was confident, and young. As they began to make love, she guessed that she was about to leave behind everything she knew, all the

Salman Rushdie

roots of her self. Her lovemaking became ferocious, as if his body were a locked gateway to the unknown, and must batter it down. Not everything will be wonderful, he warned her. There is a terrible drought.) His palace, unfortunately, is abominable. It crumbles, stinks. In her room, the curtains are tattered, the bed precarious, the pictures on the wall pornographic representations of arabesque couplings at some petty princelings court. No way of knowing if these are her husbands ancestors or a job-lot purchased from a persuasive pedlar. Loud music plays in ill-lit corridors, but she cannot find its source. Shadows scurry from her sight. He installs her, vanishes, without an explanation. She is left to make herself at home. That night, she sleeps alone. A ceiling fan stirs the hot, syrupy air. It simmers, like a soup. She cannot stop thinking of home: its nocturnal sirens, its cooling machinery. Its reification of the real. Amid that surplus of structures, of content, it is not easy for the phantasmagoric to gain the upper hand. Our entertainment is full of monsters, of the fabulous, because outside the darkened cinemas, beyond the pages of the books, away from the gothic decibels of the music, the quotidian is inescapable, omnipotent. We dream of other dimensions of paranoid subtexts, of underworlds, because when we awake the actual holds us in its great thingy grasp and we cannot see beyond the material, the event horizon. Whereas here, caught in the empty bubbling of dry air, afraid of roaches, all your frontiers may crumble; are crumbling. The possibility of the terrible is renewed. She has never found it easy to weep, but her body convulses. She cries dry tears, and sleeps. When she awakes there is the sound of a drum, and dancers. In a courtyard, the women and girls are gathered, young and old. The drummer beats out a rhythm and the ladies respond in unison. Their knees bent outward, their splay-fingered hands semaphoring at the ends of peremptory arms, their necks making impossible, lateral shifts, eyes ablaze, they advance across cool stone like a syncopated army. (It is still early, and the courtyard is in shadow; the sun has not yet lent the stone its fire.) At the dancers head, tallest of them all, fiercely erect, showing them how, is Mr Maharajs sister, over sixty years old, but still the greatest dancer in the state. Miss Maharaj has seen the newcomer, but makes no acknowledgement. She is then mistress of the dance. Movement is all. When its finished, they face each other, Mr Maharajs women: the sister, the American. What are you doing? A dance against the firebird. A propitiatory dance, to ward it off. The firebird. (She thinks of Stravinsky, of Lincoln Center.) Miss Maharaj inclines her head. The bird which never sings, she says. Whose nest is secret; whose malevolent wings brush womens bodies, and we burn. But surely there is no such bird. Its just an old wives tale. Here there are no old wives tales. Alas, there are no old wives. Enter Mr Maharaj! Turbaned, with an embroidered cloth flung about his broad shoulders, how handsome, how manly, how winsomely apologetic! She finds herself behaving petulantly, like a woman from another age. He woos and cajoles. He went to prepare her welcome. He hopes she will approve. What is it? Wait and see. In the semi-desert beyond his stinking palace, Mr Maharaj has prepared an extravaganza. By moonlight, beneath hot stars, on great carpets from Isfahan and Shiraz, a gathering of dignitaries and nobles welcomes her, the finest musicians play their mournful, haunting flutes, their ecstatic strings, and sing the most ancient and freshest love-songs ever heard; the most succulent delicacies of the region are offered for her delight. She is already famous in the neighbourhood, a great celebrity. I

Salman Rushdie

invited your husband to visit us, the governor of an adjacent state guffaws, but I told him, if you dont bring your beautiful lady, dont bother to show up. A neighbouring ex-prince offers to show her the art treasures locked in his palace vaults. I take them out for nobody, he says, except Mrs. Onassis, of course. For you, I will spread them in my garden, as I did for Jackie O. While the moonlight lasts, there are camel-races and horse-races, dancing and song. Fireworks burst over their heads. She leans against Mr Maharaj, his absence long forgiven, and whispers, you have made a magic kingdom for me, or (she teases him) is this how you relax every night? She feels him stiffen, smells the bitterness leaking from his words. It is you who have made this happen, he replies. In this ruined place you have conjured this illusion. The camels, the horses, even the edibles have been brought from away. We impoverish ourselves to make you happy. How can you imagine that we are able to live like this? We protect the last fragments of what we had, and now, to please you, we plunge deeper into debt. We dream only of survival; this Arabian night is an American dream. I asked for nothing, she said. This conspicuous consumption is not my fault. Your accusation, your diatribe, is offensive. He has had too much to drink, and it has made him truthful. It is our obeisance, he tells us, at the feet of power. Rainmaker, bring us rain. Money, you mean. What else? Is there anything else? I thought there was love, she says. The full moon has never looked more beautiful. No music has ever sounded lovelier. No night has ever felt so cruel. She says: I have something to tell you. She is pregnant. She dreams of burning bridges, of burning boats. She dreams of a movie she has always loved, in which a man returns to his ancestral village, and somehow slips through time, to the time of his fathers youth. When he tries to flee the village, and returns to the railway station, the tracks have disappeared. There is no way home. This is where the film ends. When she awakes from her dream, in her sweltering room, the sheets are soaked and there is a woman sitting at her bedside. She gathers a wet sheet around her nakedness. Miss Maharaj smiles, shrugs. You have a strong body, she says. Younger, but in other ways not so unlike mine. I would have left him. Now I just dont know. Miss Maharaj shakes her head. In the village they say it will be a boy, she explains, and then the drought will break. Just superstition. But he cant let you leave. And afterwards, if you go, hell keep the child. Well see about that! She blasts. When she is agitated her tones become nasal, unattractive even to herself. In her minds eye the story is closing around her, the story in which sh e is trapped, and in which she must, if she can, find the path of action: preferably of right action, but if not, then of wrong. What cannot be tolerated is inertia. She will not fall into some tame and heat-dazed swoon. Romance has led her into errors enough. Now she will use her head. Slowly, as the weeks unfold, she begins to see. He does not own the casino in his palace in the city, has signed a foolish contract, letting it to a consortium of alarming men. The rent they pay him is absurd, and it is stipulated in the small print that on certain high days each year he must hang around the gaming-tables, grinning ingratiatingly at the guests, lending a tone. The satellite-dish franchises are more lucrative, but this greedy old wreck of a country residence needs to eat off far richer platters if its to be properly fed. This rural palace is ageless: perhaps six hundred years. Most of it lacks electricity, windows, furniture. Cold in the cold season, hot in the heat, and if the rains should come, many of its staterooms would flood. All they have here is water, their inexhaustible palace spring. At the back of the palace, past the ruined zones where the bats hold sway, she picks her way through accumulated guano and sees a line form before dawn. The villagers, rendered indigent by the drought, come under cover of

Salman Rushdie

darkness, hiding their humiliation, filling their supplicant pitchers. Behind the line of the thirsty there stands, like a haunting, the high black shadow of a crenellated wall. A village woman with a few unaccountable words of English explains that this charred fortress was, in former days, the larger part of the princes residence. Great treasures were lost when it burned; also, lives. When did this happen? In before time. She begins to understand his bitterness. Another princess, Miss Maharaj tells her, a dowager even more destitute than we, recently ended her life by drinking fire. She crushed her heirloom diamonds in a cup and gulped them down. So Mr Maharaj, visiting America, had turned himself into an illusion of sophistication and innovation, had won her with a desperate performance. He has learned to talk like a modern man but in truth is helpless in the face of the present. The drought, his unworldliness, the decision of history to turn away her face, things are his undoing. In Greece, the athlete who won the Olympic race became a person of high rank in his home state. Mr Maharaj, however, rots, as does his house. Her own room begins to look like luxurys acme. Glass in the windows, the slow-turning electric fan. A telephone with, sometimes, a dialling tone. A socket for her laptops power line, the intermittent possibility of forging a modem link with that other planet, her earlier life. He has not taken her to his own room because he is ashamed of it. Sensing the life growing inside her, she wants to forgive its father; to help him out of the past, into the flowing, metamorphic present which has been her real life. She will do what she can do. She is America, and brings the rain. Again and again she awakes, sweating, naked, with Miss Maharaj murmuring at her side. Yes, a fine body, it could have been a dancers. It will burn well. Dont touch me! (She is alarmed.) All brides in these parts are brought from far afield. And once the men have spent their dowries, then the firebird comes. Dont threaten me! (Perplexed.) Do you know how many brides he has had? Terrified, raging, bewildered, she confronts him. Is it true? Is that why your sister has never married, why she gathers under her roof, to protect them, all the spinsters of the village, young and old? That interminable dance class of lifetime virgins, too frightened to take a husband? Is it true you burn your brides? Ah, my mad sister has been whispering to you, he laughs. She came to your room at night, she caressed your body, she spoke of water and fire, of womens beauty and the secret, lethal nature of men. She told you about the magic bird, I suppose. The bird of death. No, she remembers, carefully. The one who first named the firebird was you. Mr Maharaj in a fury brings her to his sisters dance class. Seeing him, the dancers stumble, their bell-braceleted feet lose the rhythm and come jangling to a halt. Why are you here, he asks them, raging. Tell my bride why you have come. Are you refugees or students? Sir, students. Are you here because you are afraid? Oh, please, sir, we are not afraid. His inquisition is relentless, bellowing, and all the while his eyes never leave his sisters. Miss Maharaj stands tall and silent. The last question is for her. How many brides have I had? How many do you say? They are locked in each others power, brother and sister, each others eternal prisoner, outside history, beyond time. Miss Maharaj is the first to drop her eyes. She is the first, she says. Its over. He turns to face his bride, and spreads his arms. You heard it with your own ears. Lets have no more of fables.

Salman Rushdie

The heat is maddening. Skeletal bullocks die on the brown lawn. Some days, there are mustard-yellow clouds filling the sky, hanging over the evaporating marshes to the west. Even this hideous yellow rain would be welcome, but it does not fall. Everyone has bad breath. All exhale serpents, dead cats, insects, frogs. Everyones perspiration is thick, and stinks. In spite of all her resolutions, the heat hypnotises her. The child grows. Miss Maharajs dancers grow careless about closing doors and windows. They are to be glimpsed, here and there, painting one anothers bodies in hot colours and wild designs, making love, sleeping with limbs entwined. Mr Maharaj does not come to her, will not, while she is carrying. But each night, Miss Maharaj comes. Since her brothers descent upon her dance class, Miss Maharaj has barely spoken. At night she asks only to sit at the bedside, sometimes, almost primly, to touch. This, Mr Maharajs American bride allows. Her health fails. She begins to sweat, to shiver with fever. Her shit is like thin mud. Only the palace spring saves her from dehydration and swift death. Miss Maharaj nurses her, brings her salt. The only physician hereabouts is an old fellow, out of touch, useless. Both women know the baby is at risk. During these long, sick nights, quietly, absently, the sexagenarian dancer talks. Something frightful has happened here. Some irreversible transformation. Without our noticing its beginnings, so that we did not resist until it was too late, until the new way of things was fixed, there has occurred a terrible, terminal rupture between our men and women. When men say they fear the absence of rain, when women say we fear the presence of fire, this is what we mean. Something has been unleashed in us. Its too late to tame it now. Once upon a time there was a great prince here. The last prince, one could say. Everything about him was gigantic, mythological. The most handsome prince in the world, he married the most beautiful bride, a legendary dancer and temptress, and they had two children, a girl a boy. As he aged, his strength ebbed, his eye dimmed, but she, the dancer, refused to fade. At the age of fifty she had the look of a young woman of twenty-one. As the princes force faded, as that glamour which had been the heart of his power ceased to work its magic, so his jealousy increased (Miss Maharaj shrugged, moved quickly to the storys end.) The fortress burned. They both died. He had suspected his wife of taking lovers but there had been none. The children, who had been left in the care of servants, lived. The daughter became a dancer and the son a sportsman, and so on. And the villagers said that the old prince, consumed by rage, had been transformed into a giant bird, a bird composed entirely of flames, and that was the bird that burned the princess, and returns, these days, to turn other women to ashes at her husbands cruel command. And you, asks the ill woman on the bed. What do you say? Do not condescend to us in your heart, Miss Maharaj replies. Do not mistake the abnormal for the untrue. We are caught in metaphors. They transfigure us, and reveal the meaning of our lives. The illness recedes and the baby seems also to be well. The return of health is like a curtain being lifted. She is thinking like herself again. She will keep the child, but will no longer be trapped in this place of fantasies with a man she finds she does not know. She will go to the city, fly back to America, and after the child is born, what will be, will be. A quick divorce, of course. She has no desire to prevent the father from seeing his child. Extremely free access, including trips East, will be granted. She wants that, wants the child to know both cultures. Enough! Time to behave like an adult. She may even continue to advise Mr Maharaj on his financial needs. Why not? Its her job. She tells Miss Maharaj her decision, and the old dancer winces, as if from a blow. In the dead of night, the American is awakened by a hubbub in the palace, in its corridors and courtyard. She dresses, goes outside. An impromptu armada of motor vehicles has assembled: a rusty

Salman Rushdie

bus, several motor-scooters, a newish Japanese people-carrier, an open truck, a Jeep in camouflage. Miss Maharajs women are piling into the vehicles, angry, singing. They have taken weapons, the domestic weapons that came to hand, sticks, garden implements, kitchen knives. At their head, revving the Jeep, shouting impatiently at her troops, is Miss Maharaj. Whats going on? None of your business. You dont believe in fairies. Youre going home. Im coming with you. Miss Maharaj treats the Jeep roughly, driving it at speed over broken ground, without lights. The motley convoy jolts along behind. They drive by the light of a molten full moon. Ahead of them stands a ruined stone arch, an entrance to nothing, beside a fallen tree. The armada halts, turns on its lights. The dance class pours through the archway, as if it were the only possible entrance to the open waste ground beyond, the portal to another world. When she, the American, does likewise, she has that feeling again: of passing through an invisible membrane, a looking glass, into another kind of truth; into fiction. A tableau, illuminated by the lights of motor vehicles. Remember the old bridegroom, on his way to meet his young, imported bride? Here he is again, guilty, murderous, and his young wife, uncomprehending, at his side. In the background, silhouetted, are the figures of male villagers. Facing the unhappy couple is Mr Maharaj. The women burst shrieking upon the charmless scene, then come raggedly to a halt, intimidated by Mr Maharajs presence. The sister faces the brother. Somebody has left their lights flashing. The siblings faces glow white, yellow, red in the headlights. They speak in a language the American cannot understand, it is an opera without surtitles, she must infer what they are saying from their actions, from their thoughts made deeds, and so, as clearly as if she comprehended every syllable, she hears Miss Maharaj command her brother, what started between our parents stops now, and his response, a response that has no meaning in the world beyond the ruined archway, which he speaks as body turns to fire, as the wings burst out of him, as his eyes blaze; his words hang in the air as the firebirds breath scorches Miss Maharaj, burns her to cinder, and then turns upon the dotards shrieking bride. I am the firebirds nest. Something loosens within the American as she sees Miss Maharaj burn, some shackle is broken, some limit of possibility passed. Unleashed, she crashes upon Mr Maharaj like a wave, and the angry dancers pour behind her, seething, irresistible. They feel the frontiers of their bodies burst and the waters pour out, the immense crushing weight of their rain, drowning the firebird and its nest, flowing over the drought-hardened land that no longer knows how to absorb the flood which bears away the old dotard and his murderous fellows, cleansing the region of its horrors, of its archaic tragedies, of its men. The flood waters ebb, like anger. The women become themselves again, and the universe too resumes its familiar shape. The women huddle patiently under the old stone arch, listening for helicopters, waiting to be rescued from the deluge of themselves, freed from fear. As for the American, her own shape will continue to change. Mr Maharajs child will be born, not here but in her own country, to which she will soon return. Increasing, she caresses her swelling womb. The new life growing within her will be both fire and rain. (in Tibor Fischer and Lawrence Norfolk (eds), New Writing, vol. 9, Vintage, London, 1999, 231-247)

You might also like

- The Firebirds NestDocument12 pagesThe Firebirds Nest윤요섭No ratings yet

- The Firebird's NestDocument9 pagesThe Firebird's NestAlina Adriana BuneaNo ratings yet

- He Rophet S Air: A Short Story by Salman R UshdieDocument7 pagesHe Rophet S Air: A Short Story by Salman R UshdieAvira ShahzadNo ratings yet

- The Arabian Nights - Andrew LangDocument264 pagesThe Arabian Nights - Andrew Lang王少辉No ratings yet

- The Arabian Nights Entertainments (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)From EverandThe Arabian Nights Entertainments (Barnes & Noble Digital Library)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (69)

- PRAKASINA by Professor Puran SinghDocument194 pagesPRAKASINA by Professor Puran SinghtojfaujNo ratings yet

- The Crystal Palace and Other LegendsFrom EverandThe Crystal Palace and Other LegendsRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (1)

- 21 STDocument11 pages21 STLyra Lang-ayan AgustoNo ratings yet

- Andrew Lang - The Arabian NightsDocument101 pagesAndrew Lang - The Arabian Nights12345ikaNo ratings yet

- Daud Kamal and Taufiq Rafaqat PoemsDocument9 pagesDaud Kamal and Taufiq Rafaqat PoemsFatima Ismaeel67% (6)

- Elegy Written in A Country ChurchyardDocument8 pagesElegy Written in A Country ChurchyardÅmîť MâńďáľNo ratings yet

- Symbols and FolkloreDocument4 pagesSymbols and FolkloreCiprian HaretNo ratings yet

- First General Eng PoemsDocument4 pagesFirst General Eng PoemsGomathi SivakumarNo ratings yet

- The Firebird'S Nest: Now I Am Ready To Tell How Bodies Are Changed Into Different BodiesDocument1 pageThe Firebird'S Nest: Now I Am Ready To Tell How Bodies Are Changed Into Different BodiesAnimalute HaioaseNo ratings yet

- Compendium On Elegy Written in A Country Church YardDocument4 pagesCompendium On Elegy Written in A Country Church YardSuyampirakasam.S100% (2)

- Lord Dunsany - The Book of WonderDocument83 pagesLord Dunsany - The Book of WonderenglishalienNo ratings yet

- The Book of WonderDocument33 pagesThe Book of Wonderanon123No ratings yet

- Black Spring - Alison Croggon PDFDocument216 pagesBlack Spring - Alison Croggon PDFShaleni MuthiahNo ratings yet

- Woodbridge,+Sr ,+Samuel+Isett,+The+Golden-Horned+DragonDocument17 pagesWoodbridge,+Sr ,+Samuel+Isett,+The+Golden-Horned+DragonKA WO YIPNo ratings yet

- A Memory of Light - Robert Jordan - 822Document5 pagesA Memory of Light - Robert Jordan - 822nikNo ratings yet

- The Deserted VillageDocument1 pageThe Deserted Villagewaqarali78692100% (2)

- Text Book For B.A BSW 1st Sem EnglishDocument32 pagesText Book For B.A BSW 1st Sem EnglishAdam Crown100% (1)

- LaarniDocument4 pagesLaarniBriandon CanlasNo ratings yet

- Tuan Putri SaadongDocument2 pagesTuan Putri SaadongainaNo ratings yet

- The Book of Wonder: Lord DunsanyDocument32 pagesThe Book of Wonder: Lord DunsanyalvareszNo ratings yet

- Pious Woman's RewardDocument11 pagesPious Woman's RewardummeaimanNo ratings yet

- BANASDocument19 pagesBANASPhyll Jhann GildoreNo ratings yet

- Souloftitree 00 GeacialaDocument100 pagesSouloftitree 00 Geacialabetül koçakNo ratings yet

- Andromeda and Other Poems by Kingsley, Charles, 1819-1875Document102 pagesAndromeda and Other Poems by Kingsley, Charles, 1819-1875Gutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Poetry - Gh. LitDocument13 pagesPoetry - Gh. LitDeon-Danii OwusuNo ratings yet

- The Arabian Nights New Deluxe Muhsin Mahdi 2e5cj6rDocument535 pagesThe Arabian Nights New Deluxe Muhsin Mahdi 2e5cj6rshabaab hasnattNo ratings yet

- Arthur Rimbaud - IlluminationsDocument30 pagesArthur Rimbaud - IlluminationsAnnie WogelNo ratings yet

- The Young King by Pablo NerudaDocument1 pageThe Young King by Pablo NerudajamespollackNo ratings yet

- 20 CSEC PoemsDocument33 pages20 CSEC PoemsMikah StroudeNo ratings yet

- GEE 19 HandoutsDocument13 pagesGEE 19 Handoutsfrancinegalicia0918No ratings yet

- Baguio Patriotic High School: CONSIDERED WRONG. (6 Points)Document3 pagesBaguio Patriotic High School: CONSIDERED WRONG. (6 Points)Ryan BersaminNo ratings yet

- A Summary of The Theology of The BodyDocument2 pagesA Summary of The Theology of The Bodybrainaic100% (1)

- Mallion Vs Alcantara PDFDocument2 pagesMallion Vs Alcantara PDFMaxxNo ratings yet

- Group 6 DubaiDocument12 pagesGroup 6 DubaiAerish RioverosNo ratings yet

- Final ExamDocument31 pagesFinal ExamAlyssa FatimaNo ratings yet

- Evidence of Hanafi Scholars That Marriage Is Valid Without A Guardian (Wali)Document7 pagesEvidence of Hanafi Scholars That Marriage Is Valid Without A Guardian (Wali)Abdullah100% (1)

- Nerito & Len NuptialsDocument3 pagesNerito & Len NuptialsAndrea CenidozaNo ratings yet

- The Letters of Peter Abelard and Heloise (12th Century)Document40 pagesThe Letters of Peter Abelard and Heloise (12th Century)Spun_GNo ratings yet

- General Elective-English Assignment: Mira Manchanda-200556Document3 pagesGeneral Elective-English Assignment: Mira Manchanda-200556Mira ManchandaNo ratings yet

- Netflix Inspired Powerpoint Design Template (BY GEMO EDITS)Document20 pagesNetflix Inspired Powerpoint Design Template (BY GEMO EDITS)Nghi PhuongNo ratings yet

- Effects of Declaration of NullityDocument3 pagesEffects of Declaration of NullityJacqueline PaulinoNo ratings yet

- Civil Wedding Ceremony EDGAR and STEPHANIEDocument4 pagesCivil Wedding Ceremony EDGAR and STEPHANIEQuijano MykNo ratings yet

- Using Die and Get MarriedDocument4 pagesUsing Die and Get Marriedloreva2009No ratings yet

- Shieh v. Kumon North America, Inc. - Document No. 17Document2 pagesShieh v. Kumon North America, Inc. - Document No. 17Justia.com0% (1)

- A Folktale From IndiaDocument2 pagesA Folktale From IndiaAsif KaziNo ratings yet

- Pre-Wedding PeranakanDocument3 pagesPre-Wedding Peranakanintanadiamalina100% (1)

- South Indian Wedding CeremonyDocument2 pagesSouth Indian Wedding CeremonyNavernMNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 - Extra WS 3Document2 pagesUnit 1 - Extra WS 3On the YT LâmNo ratings yet

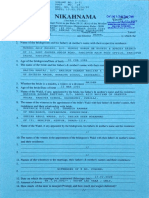

- O. 1601 (From Gha) Nikahnama: Mol .Ammat? 0Document2 pagesO. 1601 (From Gha) Nikahnama: Mol .Ammat? 0htokon75% (4)

- Wedding Traditions Around The WorldDocument12 pagesWedding Traditions Around The WorldАнастасия ФоменкоNo ratings yet

- Hindu Marriage Registration Rules - UP, 1973Document16 pagesHindu Marriage Registration Rules - UP, 1973Tushar GuptaNo ratings yet

- English Grammar, Learn English Verbs, Learn English Verb Forms, Verb List, Forms of VerbsDocument4 pagesEnglish Grammar, Learn English Verbs, Learn English Verb Forms, Verb List, Forms of Verbsnikhil_tiwari809No ratings yet

- Script WeddingDocument6 pagesScript WeddingAnthony Pineda82% (11)

- A Bride For KeepsDocument52 pagesA Bride For KeepsBethany House Publishers75% (4)

- Augusto vs. Dy (Property Relations)Document2 pagesAugusto vs. Dy (Property Relations)Ariane Espina50% (6)

- Wedding March - Violin 1Document1 pageWedding March - Violin 1deny setiawanNo ratings yet

- Rosh Hashanah - The Feast of Trumpets (The Wedding of The Messiah)Document3 pagesRosh Hashanah - The Feast of Trumpets (The Wedding of The Messiah)grace10000No ratings yet

- Case AnalysisDocument7 pagesCase AnalysisKrystal Evangelista PañaNo ratings yet

- Nowhere But Here by Katie McGarry - Chapter SamplerDocument21 pagesNowhere But Here by Katie McGarry - Chapter SamplerHarlequinAustralia100% (1)

- Ilocano CultureDocument8 pagesIlocano CultureKent Alvin Guzman100% (1)