Ear Deformities, Otoplasty, and Ear Reconstruction.37

Ear Deformities, Otoplasty, and Ear Reconstruction.37

Uploaded by

rafafpsCopyright:

Available Formats

Ear Deformities, Otoplasty, and Ear Reconstruction.37

Ear Deformities, Otoplasty, and Ear Reconstruction.37

Uploaded by

rafafpsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Ear Deformities, Otoplasty, and Ear Reconstruction.37

Ear Deformities, Otoplasty, and Ear Reconstruction.37

Uploaded by

rafafpsCopyright:

Available Formats

CME

Ear Deformities, Otoplasty, and Ear Reconstruction

Charles H. Thorne, M.D. Gordon Wilkes, M.D.

Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; and New York, N.Y.

Learning Objectives: After reviewing this article, the participant should be able to: 1. Evaluate patients ears for needed adjustments to size, shape, prominence, and symmetry. 2. Identify common ear deformities and describe methods to repair them. 3. Avoid or manage common complications associated with otoplasty and ear reconstruction. Summary: The essentials of otoplasty will be described/illustrated for the following conditions: Prominent ears, underdeveloped helical rims (shell ear), macrotia, Stahls ear, constricted ear, cryptotia, and question mark ear. (Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 129: 701e, 2012.)

n this section, the authors describe and/or illustrate the essentials of otoplasty for the following conditions: (1) prominent ears, (2) underdeveloped helical rims (shell ear), (3) macrotia, (4) Stahls ear, (5) constricted ear, (6) cryptotia, and (7) question mark ear.

require surgical intervention to avoid the operated ear from being closer to the head than the unoperated ear. Goals of Treatment The goal in standard otoplasty is a normal appearing ear without evidence that there has been surgical intervention. Sharp, unnatural contours, overcorrection, and obliteration of the normal sulcus are not acceptable results. When the surgeon is finishing the procedure, before suturing the incision, the result should be evaluated from three different angles: from the front, from the side, and from behind. From the front, the helical rim should protrude beyond the antihelix in the upper third of the ear. From the side, the contours should be soft and natural in appearance. Finally, and perhaps the best clue that the setback is harmonious, the helical contour should form a straight line when viewed from behind. If, for example, the helical rim forms a C shape, the middle third of the ear is overcorrected and/or the upper and lower thirds are undercorrected. Any such disharmony should be corrected before leaving the operating room.

OTOPLASTY FOR PROMINENT EARS

Essentials of Preoperative Management The overall size and shape of the ears are assessed before evaluating the degree of prominence. In other words, the surgeon makes a distinction between prominent ears that are normal in size and contour, on the one hand, and prominent ears that are also abnormal in size or shape, on the other. Deformities such as macrotia, constricted ear, Stahls ear, cryptotia, or underdeveloped shell-like helical rims are noted. Once a determination has been made regarding the size and shape, the prominence is most easily evaluated by assessing the auricle in thirds: upper third, middle third, and lower third (lobule). The entire ear may be prominent, but in many cases the prominence is more localized (e.g., upper third only, middle third only, upper and lower thirds only). Finally, the symmetry is addressed. Patients tend to obsess about symmetry even though, from an aesthetic point of view, it is frequently not the most important issue. In most cases of asymmetry, both ears

From the Institute for Reconstructive Sciences in Medicine, and the Department of Plastic Surgery, New York University School of Medicine. Received for publication January 27, 2011; accepted October 4, 2011. Copyright 2012 by the American Society of Plastic Surgeons DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182450d9f

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Related Video content is available for this article. The videos can be found under the Related Videos section of the full-text article, or, for Ovid users, using the URL citations printed in the article.

www.PRSJournal.com

701e

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery April 2012

Advantages/Disadvantages of the Treatment Alternatives Traditional techniques that involve scoring the cartilage1 or full-thickness incisions/tubing of the cartilage2 may have the advantage that recurrence of the deformity is less likely. We prefer to avoid these techniques, however, with the hope of achieving more natural appearing results and confining complications to those problems that can be more easily corrected. The approach described below, therefore, incorporates the authors bias that undercorrection, potential recurrence, and suture complications are preferable to overcorrection, unnatural contours, sharp edges, and potentially unrepairable deformities. The reader is also directed to the reference describing incisionless otoplasty.3 Key Elements of the Operation The steps for standard, setback otoplasty are presented below and are depicted in Figure 1 and demonstrated in Video 1. [See Video, Supplemental Digital Content 1, in which Dr. Thorne demonstrates his otoplasty technique, available in the Related Videos section of the full-text article on PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users, at http://links. lww.com/PRS/A473. (From Thorne C. Otoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:291292.)] Incision An incision is made in the retroauricular sulcus. The only skin removed is a small triangle from the medial surface of the lobule, to facilitate later earlobe repositioning,4 taking care to preserve enough tissue for a normal earlobe and retrolobu-

Video 1. Supplemental Digital Content 1, in which Dr. Thorne demonstrates his otoplasty technique, is available in the Related Videos section of the full-text article on PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users, available at http://links.lww.com/PRS/A473. (From Thorne C. Otoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;122:291292.)

lar sulcus and to preserve at all costs the ability to wear an earring. Dissection The cartilage is exposed on its posterior (medial) surface, exposing the helical tail. Soft tissue is excised from deep to the concha. The retrolobular sulcus is dissected deeply, a maneuver that is necessary for lobule repositioning at the conclusion of the procedure. Correction Mustarde sutures of 4-0 clear nylon are placed to recreate the upper portion of the antihelix and

Fig. 1. Otoplasty technique. The combination of Mustarde scaphoconchal sutures, conchal resection with conchal reapproximation, and a Furnas conchal-mastoid suture. (Left) Sutures placed. (Center) Sutures tightened to create the desired contour. (Right) Same sutures as seen through the retroauricular incision.

702e

Volume 129, Number 4 Otoplasty

the superior crus of the triangular fossa.5 It is important that the surgeon appreciate that the antihelix is not a straight line. In fact, the superior crus (the upper termination of the antihelix) curves far forward and becomes almost parallel to the inferior crus. The Mustarde sutures are placed like the spokes on a wheel (not parallel to each other) to create a curved, natural appearing antihelical fold. Approximately three to four Mustarde sutures are required if the deformity is confined to the upper third. If the deformity extends into the middle third, as many as six to eight Mustarde sutures may be required (Fig. 1). To address the middle third, the conchal depth is assessed. If there is excess depth, a minimal resection of the concha is performed at the junction of the posterior wall and floor of the concha. The conchal defect is closed primarily with many more nylon sutures (Fig. 1). We prefer to use a small conchal resection in combination with conchal setback (see below) so that the conchal resection can be limited to approximately 2 mm. Two 5-0 polydioxanone sutures are used to close the triangular skin defect on the medial surface of the earlobe. The sutures also incorporate a bite of the conchal cartilage, deep in the sulcus, which will result in correction of the earlobe prominence. Finally, a 3-0 nylon conchal-mastoid Furnas suture is placed.6 This is the suture that really sets back the ear. The middle and upper third maneuvers only create the contours and should not be used to set back the ear. In other words, most patients are treated with both a small conchal resection and a conchal setback. Only rarely is a conchal-mastoid suture alone adequate. If placement of this suture pushes the posterior wall of the external meatus too far forward (obstructing the meatus), a conchal resection is definitely performed. The skin incision is approximated with interrupted or intracuticular sutures of 5-0 plain gut. Perioperative Management Xeroform (Covidien, Mansfield, Mass.) is placed over each ear and the patients head is wrapped loosely in a bulky gauze dressing. No attempt is made to put pressure on the ears with the dressing. The dressing is removed in 4 to 5 days, after which no further dressing is necessary. The patient is instructed to wear a loosely fitting headband at night only, to prevent inadvertent trauma to the repair. Complications The surgical technique determines which complications are the most likely. The technique described above eliminates the worst complications: overcorrection, sharp edges, unnatural contours, inharmonious setback, telephone deformity, and infection. Suture complications are quite common, however. The nylon Mustarde sutures may eventually protrude through the posterior skin. The potential risk is lessened by pushing the knot flush with the posterior surface of the ear cartilage. This complication may occur within the first few weeks postoperatively but usually several years later. Protruding sutures may be associated with a painful, erythematous pustule. Patients should be informed of this potential problem and encouraged to return to the surgeon immediately. The authors have seen patients with this problem managed with topical antibiotics for months with no improvement, only to be symptom free 1 day after suture removal under local anesthesia. The sutures can be removed without fear of recurrence of the deformity if they have been in place for several months. One author (C.H.T.) has had two instances in which the deformity recurred to a degree that reoperation was necessary. Interestingly, a review of the operative notes indicated that polydioxanone sutures were used for the Mustarde sutures in those cases. Although this is only anecdotal evidence, the author has returned to using nylon sutures in all cases. One remaining problem deserving mention is disharmony of the result. Regardless of the otoplasty technique chosen, a successful but disharmonious setback may be produced; that is, the result just does not appear right. The telephone deformity is a good example. As mentioned above, the helix should appear almost straight when viewed from behind. If the helical contour resembles a hockey stick or a C, the setback will just not appear aesthetically pleasing.

OTOPLASTY FOR OTHER EAR DEFORMITIES

Essentials of Preoperative Management Not uncommonly, patients will present with ears that are prominent but also abnormal in contour and/or size. The first step for the surgeon is to differentiate between deformities such as underdeveloped, flat helical rims (shell ear), excessively large ears (macrotia), Stahls ear, constricted ear, cryptotia, and the question mark ear.

703e

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery April 2012

Fig. 2. Ear reduction and setback for macrotia with prominence. (Above, left) Cartilage is excised from the scapha followed by placement of Mustarde sutures. (Above, right) A small conchal reduction has been performed and the concha is reapproximated. (Below, left) A single Furnas suture is placed. (Below, right) The postoperative result is shown. This patient was a young child, and the amount of reduction was small. In the vast majority of ear reduction cases, it is necessary to remove a wedge from the helical rim. If the helical rim is not shortened, it will be too long for the reduced scaphal circumference, resulting in buckling and irregularities.

Goals of Treatment The goals of treatment are the same as for standard otoplasty except that, depending on the degree of deformity, the results may fall short of normal. All ear deformities exist along a spectrum ranging from mild, almost imperceptible abnormalities to severely affected, underdeveloped structures that bear little resemblance to normal auricles. If the latter is the case, otoplasty may be inappropriate and the patient may be best treated by discarding the cartilage and placing a cartilage framework as discussed below under Total and Subtotal Ear Reconstruction. Advantages and Disadvantages of Treatment Alternatives As with standard otoplasty, numerous techniques have been described to improve the ap-

pearance of the deformities discussed in this article. Each has its own pros and cons. Rather than describe the myriad procedures that exist in the literature, the authors preferred methods, along with the rationale for choosing them, are discussed below. Key Elements of the Surgical Procedure Incision There are only so many acceptable incisions through which to perform otoplasty. The retroauricular incision was described above and is used for standard otoplasty. The correction of shell ear, macrotia, constricted, ear and Stahls ear all require an incision on the lateral (visible) surface of the ear, just inside the helical rim either alone or in combination with the auricular sulcus incision. When placed appropriately,

704e

Volume 129, Number 4 Otoplasty

these anterior incisions usually heal with an acceptable scar. Cryptotia and the question mark ear require different approaches. Shell Ear In the case of shell ear (absence of the helical overhang), the mere performance of the incision through the skin and cartilage, followed by skin closure at the end of the procedure, will create some helical definition. If a wedge of helical rim skin and cartilage is removed so that there is slight tension on the closure, the helical rim will curl into a desirable contour. Macrotia Once the above incision is made, a crescent of skin and cartilage (much less skin than cartilage) is excised from the scapha7,8 (Fig. 2). The result is a helical rim that is excessively long for the newly reduced scaphal circumference. A wedge excision of the helical rim, as described under Shell Ear, is almost always required to avoid irregularities in the redundant helix. Stahls Ear In Stahls ear, there is an abnormal bar of cartilage (sometimes called the third crus), extending from the antihelix to the helix at approximately the junction between the upper and middle thirds of the ear. If that abnormal cartilage is obvious, it must be excised (Fig. 3). The cartilage defect is closed primarily. In addition, there may be excess scapha in the region of the third crus and absence of the normal superior crus of the triangular fossa. Any excess scapha is trimmed as described above for macrotia. These authors prefer the technique described by Kaplan and Hudson,9 in which the excised piece of cartilage is used to augment the deficient superior crus. Constricted Ear In a constricted ear, the fundamental abnormality is that the helical rim is deficient in circumference for the scapha to which it is attached. The inadequate length of the helix constricts the ear and forces it into a cupped shape that pro-

Fig. 3. Repair of Stahls ear. (Above, left) Preoperative appearance. (Above, right) Exposure of the lateral surface of the ear cartilage and plan for resection of extra crus. (Below, left) Appearance after resection of abnormal crus and reconstruction of the superior crus using the resected cartilage. (Below, right) Postoperative result.

705e

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery April 2012

trudes from the head. In the mildest deformities, the overhang can be trimmed. The result is an ear that is slightly small; however, the contour is improved. Any attempt at otoplasty must be accompanied by lengthening of the helix. The usual procedure is to extend the lateral incision described above into the concha, around the crus of the helix. In this manner, the crus of the helix can be recruited into the helix, thereby lengthening it and allowing standard otoplasty maneuvers to set back the ear. The defect in the concha is closed primarily. As described above, severe deformities (Tanzer 3a and 3b) may be better treated as a microtia case with a rib cartilage framework rather than by attempting salvage of the native cartilage. Cryptotia In cryptotia, the superior aspect of the ear is hidden beneath the temporal scalp. In some cases, the auricular cartilage is normal and requires only to be extracted from its hiding place. Lateral traction on the ear will reveal a normal auricle. In other cases, the cartilage is malformed and requires additional modification. The ear is grasped and pulled away from the scalp, and an incision is made around the superior aspect. Various techniques have been described on how to resurface the defect, from skin grafts to ingenious local flaps.10 These authors have found that full-thickness skin grafts from the groin provide the least visible donor site for such extra tissue (Fig. 4). Question Mark Ear In the question mark ear, there is excess scapha in the upper portion of the ear and a deficiency at the junction of the middle and lower thirds, resulting in a question mark shape. The superior excess can be treated as described above under Macrotia. In mild cases, the deficient lower third can be treated using the combination of a V-Y advancement from behind the ear plus a cartilage graft.11 The cartilage graft can usually be taken from the scaphal reduction or from the concha. In severe deformities, however, it is preferable to discard most of the ear cartilage and create a rib cartilage framework as described below under Total and Subtotal Ear Reconstruction.

NONOPERATIVE CORRECTION OF EAR DEFORMITIES

During early infancy, the auricular cartilage retains its fetal plasticity, allowing some of the deformities described above to be corrected by nonsurgical stenting.12,13 The ears are folded over acrylic and taped into the correct position. The splints and tape are changed regularly, and the skin is checked compulsively for erosion. The pro-

Fig. 4. Cryptotia. (Above) Preoperative deformity showing superior aspect of ear cartilage buried beneath scalp skin. (Center) Design of the flap. (Below) Postoperative result. (Used with permission from Gordon Wilkes, M.D.)

cess is continued for several months or until there is no further improvement in auricular contour. Remarkable results from Japan have been pub-

706e

Volume 129, Number 4 Otoplasty

Fig. 5. Neonatal ear molding. (Left) Appearance at birth and (right) after ear molding. (Used with permission from Gordon Wilkes, M.D.)

lished. Dr. Barry Grayson, an orthodontist at New York University, has produced similar superb results. What remains unclear is how many weeks or months this moldability lasts. An illustrative example is shown in Figure 5. It is our impression that the new cartilage will not be formed in those cases where cartilage is deficient, but the shape of the existing cartilage can definitely be altered.

TOTAL AND SUBTOTAL EAR RECONSTRUCTION

In this section, the authors describe and illustrate the essentials of ear reconstruction for total and subtotal defects. Patients with microtia, patients with traumatic or extirpative loss of the auricle, and some patients with the extreme manifestations of the deformities described above are best treated with total or subtotal reconstruction of the ear. In addition to autogenous methods of reconstruction, prosthetic reconstruction and Dr. Reinischs technique of reconstruction14 using polyethylene frameworks is described and illustrated. Excellent results have also been reported by Park using expansion and a two-flap technique.15 Autogenous Reconstruction Essentials of Preoperative Assessment Preoperative assessment consists of an evaluation of the skin quality/laxity, presence or absence of an external auditory canal, presence or

absence of scars, location of the hairline, the extent to which any remnant corresponds to the ideal position of the eventual reconstructed ear, and the underlying skeleton. Although most patients in this category have isolated microtia and have never had previous surgery, there are many patients who have microtia in the setting of severe skeletal and soft-tissue hypoplasia (hemifacial microsomia), microtia that has been operated on previously, posttraumatic deformities, and postextirpative deformities. The microtia classification in the literature with the most practical implications for surgical technique is that of Nagata16 18: lobular type, small conchal type, and large conchal type. In the latter type, a tragus and concha are present, at least to some extent, and this allows placement of a less complex cartilage framework and generally yields superior aesthetic results. Microtia patients who have undergone previous surgical intervention will have scars and cartilage or artificial frameworks, all of which may not be in the ideal position. Even a perfect ear that is located too low or too anterior is frequently worse than no ear at all. Finally, patients with posttraumatic deformities or postablative deformities frequently have the advantage of a tragus and concha but the disadvantage of nondistensible, scarred, sometimes irradiated soft tissue. A more detailed and extremely helpful classification awaits publication by Firmin19 and takes into consideration the type

707e

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery April 2012

Fig. 6. Drawings demonstrate the Brent technique for fabrication of ear framework from rib cartilage. The Brent framework consists of two pieces. The base is obtained from the synchondrosis of two rib cartilages and the helical rim is obtained from a floating rib cartilage. The details are carved into the base using a gouge. The helical rim piece is thinned and attached to the base using nylon sutures.

of incision required, the type of framework required, and the type of additional cartilage that is used for projection. Goals of Treatment The goal in these patients is to create an ear that appears normal from conversational distance and will have little effect on the patients hairstyle and earrings. No reconstructed ear will avoid detection under intimate scrutiny. The framework, whether cartilage or polyethylene, is bulkier and less flexible than a normal ear. A prosthesis, although inconspicuous from a distance, will be obviously artificial in any intimate setting. If the prosthesis is removed, which it has to be for at least 8 hours per day, the metallic suprastructure to which it is attached will be visible, palpable, and potentially embarrassing.20 Advantages and Disadvantages of the Treatment Alternatives The advocates of cartilage reconstruction, including the authors of this article, tout the advantages of autogenous tissue. The advocates of artificial frameworks attempt to sell the avoidance of a chest incision and the biocompatibility of porous polyethylene. Those who prefer prosthetic recon-

struction claim superior aesthetics, less invasive procedures, and a lower cost. The authors rationale for autogenous reconstruction is addressed in more detail under Complications below. Within the category of autogenous reconstruction, the two most popular techniques are those described by Brent21 and Nagata.16 18 The Brent technique is a modification of that originally described by Tanzer22 and involves four stages (described below). Nagata analyzed the results of the Brent technique and designed a two-stage technique (described below) to address its perceived imperfections. The Brent technique is easier to learn and has fewer complications. The Nagata technique condenses the reconstruction into two stages and uses a more detailed, complicated framework. The Nagata technique has the potential to yield a better aesthetic result by providing a more natural tragus, antitragal notch, and conchal bowl region and better antihelical definition.23 The Nagata technique is like swinging for the fences; there are more home runs and more strikeouts. Key Elements of the Surgical Procedure Brent technique. The patient is examined in the upright position and the lowest point of the ear-

708e

Volume 129, Number 4 Otoplasty

Fig. 7. Drawings depict Nagata stage 1 incision, dissection of pocket, and insertion of framework. (Above, left) The W-shaped incision is made, taking the skin from the medial surface of the earlobe to resurface the concha. (Above, right) The pocket is dissected, leaving an intact pedicle at the caudal end of the flap. (Below, left) The framework is inserted. (Below, right) After stage 1, suction drains are in place to encourage coaptation of the skin to the underlying framework.

Fig. 8. Drawings showing the Nagata framework. (Left) In a manner similar to Brent, the base and its details are carved from the synchondrosis of two adjacent rib cartilages. (Right) The four pieces of cartilage that make up the framework are shown and numbered. The base and helical rim are present, as they are in the Brent technique. There is an additional antihelix triangular fossa piece and an additional tragus-antitragus piece that are unique to the Nagata procedure.

Video 2. Supplemental Digital Content 2, in which Dr. Wilkes demonstrates the carving of ear framework using autogenous rib cartilage, is available in the Related Videos section of the full-text article on PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users, at http://links.lww.com/PRS/A474.

lobe on the unaffected side is transferred to the affected side. The attempt is to place the lowest point of the reconstruction so that it, and the patients earring, are at the same level as the normal side. The normal ear is traced on clear x-ray

709e

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery April 2012

The incision is made and the cartilage remnant is removed from the superior portion of the malformed ear. The pocket is dissected so that it extends slightly beyond the markings, especially posteriorly, where skin without hair can be recruited over the framework. Hemostasis is obtained, a moist gauze is placed over the area, and attention is directed to the chest. A transverse incision is made over the caudal aspect of the rib cage. The rectus abdominis muscle is divided and the cartilages are exposed and examined. Two cartilage pieces are required, one that includes the synchondrosis of two rib cartilages to form the base and a second, preferably 10 cm in length, to create the helical rim. The details are applied to the cartilages on the back table using sterilized gouges and scalpels, and the cartilages are attached using nylon sutures (Fig. 6). Once the framework is complete, it is inserted into the pocket, two closed suction drains are placed, and the incision is sutured. A soft bulky dressing is applied. At stage 2, the lobule is rotated, the caudal aspect of the cartilage framework is inserted into the bivalved lobule, and the lobule is inset in the precise position to yield an auricle of the desired length. At stage 3, the auricle is elevated, the retroauricular scalp is undermined and advanced into the sulcus, and the defect on the backside of the elevated ear is resurfaced using a full-thickness graft from the groin. At the final stage, the tragus

Video 3. Supplemental Digital Content 3, in which Sean Boutros, M.D., demonstrates first-stage autogenous reconstruction, is available in the Related Videos section of the full-text article on PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users, at http://links.lww.com/PRS/A475.

film and sterilized. Using this tracing, a template is fashioned of the desired framework, approximately 3 mm shorter and 2 mm narrower than the desired ear. The template is used to mark the exact location and orientation of the desired auricle. An incision is designed to provide access for removal of the superior cartilage remnant and large enough to place the eventual framework. In addition, it is placed such that it can be used at stage 2 for lobule rotation and at stage 4 for construction of the tragus.

Fig. 9. Drawings show Nagata stage 2, elevation of the framework. (Left) The auricle is elevated, the cartilage graft is wedged into the sulcus, the scalp is advanced, and the cartilage graft is covered with a temporoparietal flap and skin graft. (Center) The skin graft is inset. Nagata prefers a split-thickness skin graft, but these authors have noted significant shrinkage of the split grafts and recommend full-thickness grafts. (Right) Cross-section shows the cartilage graft in place providing projection and the temporoparietal flap covering the cartilage graft.

710e

Volume 129, Number 4 Otoplasty

is constructed. An incision is made around the posterior border of the ideal tragus. The skin of the concha is elevated and the concha is deepened by excising subcutaneous tissue. A composite graft from the contralateral concha is placed upside down to resurface the underside of the tragus, and a small full-thickness graft is used to resurface the conchal floor. Nagata technique. The patient is examined in the same fashion, and the lowest point of the desired new ear is marked as described above. A similar tracing is made, but it is helpful to make additional tracings of the antihelix piece and the tragus-antitragus anatomy so that decisions can be made intraoperatively and those pieces carved accordingly. The W-shaped incision is designed to provide the same exposure as in the Brent procedure, but also to rotate the lobule at the first stage (Fig. 7). As mentioned above, Firmin has developed a simplified approach to the incisions/ skin approach.19 The superior remnant is removed and the pocket is dissected. A soft-tissue pedicle is left attached near the apex of the central limb of the W to help with vascularity of the large skin flap. Note that the Nagata technique robs the skin from the back of the earlobe to resurface the concha. This results in a large flap with more potential for ischemia than in the Brent technique but has the advantage of potentially superior conchaltragal definition. The lobule is rotated into position and inset.

Fig. 10. Autogenous reconstruction for microtia with the Nagata technique. (Above, left) Preoperative appearance. (Above, right) Postoperative result. (Below) Rib cartilage framework. (Used with permission from Gordon Wilkes, M.D.)

711e

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery April 2012

Although a transverse chest incision usually results in less tendency for hypertrophic scar, an oblique incision is more versatile and can be extended if the surgeon needs to search for better cartilage pieces. A total of five pieces are needed as opposed to the two for the Brent technique: the base, the helical rim, the antihelix piece, the tragus-antitragus piece, and a piece to bank in the chest for the second stage. Once the cartilages are harvested, it is helpful to leave a catheter in the chest for the continuous administration of bupivacaine postoperatively. The cartilage remnants that remain after the framework is carved can be diced and placed in the perichondrial sleeves to maximize rib cartilage regeneration. Alternatively, neorib cartilages can be constructed by wrapping the diced remnants in an absorbable gauze (e.g., Surgicel; Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, N.J.) gauze and sewing them into the cartilaginous defects. The surgeon then sits at the back table and the cartilages are carved and spliced together as shown in Figure 8. Although Nagata, Firmin, and Wilkes prefer to use double-armed wire sutures on straight needles, Thorne uses sutures of the same design but in nylon. The double-armed short, straight needles allow two pieces of cartilage to be sutured from the anterior surface, rather than from the posterior surface. (See Video, Supplemental Digital Content 2, in which Dr. Wilkes demonstrates the carving of ear framework using autogenous rib cartilage, available in the Related Videos section of the full-text article on PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users, at http:// links.lww.com/PRS/A474.) When the framework is complete, it is inserted into the pocket. Most surgeons use closed suction drains, but Nagata sews bolsters in place to encourage the skin to drape into the interstices of the framework. (See Video, Supplemental Digital Content 3, in which Sean Boutros, M.D., demonstrates first-stage autogenous reconstruction, available in the Related Videos section of the full-text article on PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users, at http://links.lww.com/ PRS/A475.) At the second stage, the ear is elevated, the banked cartilage is removed from the chest and used to augment projection of the framework, a temporoparietal flap is used to cover that cartilage graft, and the sulcus is resurfaced with a skin graft. Nagata prefers a split-thickness graft from the scalp, but others have found those grafts excessively prone to contraction and prefer a full-thickness graft from the groin (Fig. 9). An example of a postoperative result is shown in Figures 10 and 11.

Fig. 11. Close-up view of the patient shown in Figure 10, postoperative result. (Used with permission from Gordon Wilkes, M.D.)

Complications Ischemic wound healing problems are rare when using the Brent technique. There is a definite learning curve with the Nagata procedure, however, and ischemic necrosis of the skin flap at the tip, in the region of the intertragal notch, is not uncommon in inexperienced hands. Even when the surgeon is experienced and there is no complication, the vagaries of wound healing and variations in skin thickness, and variations in the surgeons ability to create a perfect framework, yield a spectrum of postoperative resultsnot uniformly excellent results. This is true for both Brent-type and Nagata-type reconstructions. If exposure of the cartilage framework occurs, it must be dealt with promptly. Small areas of exposure (0.5 cm) that are not over a prominent area of the framework may heal secondarily but require close follow-up. If there is the slightest evidence of infection, local flap coverage is necessary. For larger areas of cartilage exposure or where the exposure is over the helical rim, coverage should be provided on an urgent basis. The type of local flap varies with the size and location of the cartilage exposure. If there is any doubt about the viability of a local flap, a temporoparietal flap and skin graft are the most reliable options. Although use of the temporoparietal flap precludes its use at the second stage, it is vastly preferable to have stable coverage over the frame-

712e

Volume 129, Number 4 Otoplasty

shown in Video 4, produced by Reinisch. (See Video, Supplemental Digital Content 4, in which John Reinisch, M.D., and Joseph Roberson, M.D., demonstrate ear reconstruction using a Medpor framework and canaloplasty in a single stage, available in the Related Videos section of the full-text article on PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users, at http://links.lww.com/PRS/A476.) Reinisch has the most experience with this technique. His complication rate was high (42 percent) when he first began to use Medpor (Porex Surgical, Inc., Newnan, Ga.) frameworks, but the routine addition of temporoparietal flaps has resulted in a very low complication rate at the present time.14 The video also shows concomitant canaloplasty to restore hearing. The authors of this article have seen a number of patients who underwent this procedure performed by surgeons other than Reinisch, who had persistent and difficult problems with exposed Medpor frameworks. Prosthetic Reconstruction Prosthetic reconstruction has a role in ear reconstruction, especially in older individuals who are not interested in or who are not candidates for a multiple stage reconstruction. The best indications are adult patients who have undergone major extirpative surgery, patients with major trauma or burns, and elderly patients with medical comorbidities20,24 (Fig. 12). Prostheses are generally not the best choices in children, however, unless there is no other option. Children tend not

Video 4. Supplemental Digital Content 4, in which John Reinisch, M.D., and Joseph Roberson, M.D., demonstrate ear reconstruction using a Medpor framework and canaloplasty in a single stage, is available in the Related Videos section of the full-text article on PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users, at http:// links.lww.com/PRS/A476.

work than to cheat on the coverage and save the temporoparietal flap for the second stage. Nylon or wire sutures may become visible or palpable months or years later and are easily removed. Reconstruction Using a Medpor Framework Because of space constraints, the steps of this procedure are not discussed in detail but are

Fig. 12. Prosthetic reconstruction of the ear after burn deformity. (Left) Deformity. (Right) After fabrication of implant retained prosthesis. (Used with permission from Gordon Wilkes, M.D.)

713e

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery April 2012

are time consuming and prone to failure, especially in important social situations. The method of retention using osseointegrated implants is more convenient and more secure. Advocates of prostheses say they are cheaper than surgical reconstruction. These authors doubt that is true if cost is calculated over the life of the patient. Prostheses last only approximately 5 years and have to be replaced continually, at significant expense. In addition, soft-tissue problems around the abutments can result in long periods when the prosthesis cannot be worn. In contrast, a talented and experienced anaplastologist can produce an ear prosthesis that is remarkable in its color, texture, and life-like quality. (See Video, Supplemental Digital Content 5, in which Dr. Wilkes and anaplastologist Akhila Regunathan demonstrate the fabrication of an ear prosthesis, available in the Related Videos section of the full-text article on PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users, at http://links.lww.com/PRS/A477.) In fact, without such an individual available to make the prosthesis, prosthetic reconstruction should not be contemplated.

Video 5. Supplemental Digital Content 5, in which Dr. Wilkes and anaplastologist Akhila Regunathan demonstrate the fabrication of an ear prosthesis, is available in the Related Videos section of the full-text article on PRSJournal.com or, for Ovid users, at http://links.lww.com/PRS/A477.

to wear prostheses, if they can help it, and the devices serve as daily reminders of their deformity. The authors feel that an appropriate autogenous reconstruction for congenital deformities is superior and more stable, requires less maintenance, and is cheaper in the long run. Prosthetic ears can be retained by adhesives or by using osseointegrated titanium fixtures attached to transcutaneous abutments. The adhesives still have a role but

RECONSTRUCTION OF PARTIAL EAR DEFECTS

The surgical options for a given partial ear defect depend on the location of the defect. There are fewer options as the defect approaches the lobule. Interestingly, the lower the

Fig. 13. Drawings of Antia-Buch helical advancement. (Left) An incision is designed inside the helical rim and around the crus of the helix. (Center) The incision is made through the skin and the cartilage, but not through the posterior skin. The helical rim is advanced to allow closure and a dog-ear of skin is removed on the posterior surface of the ear. (Right) Closure showing the crus of the helix advanced into the helical rim.

714e

Volume 129, Number 4 Otoplasty

defect, the more important it is aesthetically and the more difficult it is for the patient to conceal. Upper Third Defects The choices for defects of the upper third are as follows: 1. Local skin flaps. 2. Helical advancement (Antia-Buch procedure)25 (Fig. 13). 3. Chondrocutaneous composite flap. 4. Conchal cartilage graft and retroauricular skin flap (two stages). 5. Rib cartilage graft and retroauricular skin flap (two stages). 6. Rib cartilage graft, temporoparietal flap, and skin graft (two stages). Middle Third Defects The choices for defects of the middle third are as follows: 1. Primary closure with excision of accessory triangles (Fig. 14). 2. Retroauricular skin tube for helical rim defects only (three stages). 3. Helical advancement. 4. Conchal cartilage graft and retroauricular skin flap (two stages) (Fig. 15). 5. Rib cartilage graft and retroauricular skin flap (two stages). Lower Third Defects Various techniques have been described to reconstruct earlobe defects using soft-tissue flaps. These techniques are not as effective as those that include cartilage support. The nasal septum provides thin cartilage that is extremely useful in defects of the earlobe. A pocket is dissected corre-

Fig. 15. Two-stage reconstruction of a middle third defect using rib cartilage graft and skin flap. (Left) The incision and retroauricular flap are designed. (Right) The cartilage has been inserted and the flap closed over it.

sponding precisely to the defect, and a piece of septal cartilage is inserted. At a second stage, an incision is made around the earlobe, and the cheek and neck skin is advanced beneath the earlobe as in a face lift.

Charles H. Thorne, M.D. Department of Plastic Surgery New York University School of Medicine 812 Park Avenue New York, N.Y. 10021-2759 ct322@aol.com

PATIENT CONSENT

Patients or parents or guardians provided written consent for the use of patients images.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank John Reinisch, M.D., and Sean Boutros, M.D., who submitted videos for this article.

REFERENCES

1. Stenstrom SJ, Heftner J. The Stenstrom otoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1978;5:465470. 2. Converse JM, Wood-Smith D. Technical details in the surgical correction of the lop ear deformity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1963;31:118128. 3. Fritsch M. Incisionless otoplasty. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2009;42:11991208. 4. Gosain AK, Recinos RF. A novel approach to correction of the prominent lobule during otoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:575583. 5. Mustarde JC. Correction of prominent ears using buried mattress sutures. Clin Plast Surg. 1978;5:459464. 6. Furnas DW. Suture otoplasty update. Perspect Plast Surg. 1990; 4:136145. 7. Gault DT, Grippaudo FR, Tyler M. Ear reduction. Br J Plast Surg. 1995;48:3034. 8. Argamaso RV. Ear reduction with or without setback otoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1989;83:967975.

Fig. 14. Wedge resection and primary closure with excision of accessory triangles. (Left) Wedge excision performed and accessory triangles designed. (Right) Closure of the defect.

715e

Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery April 2012

9. Kaplan HM, Hudson DA. A novel surgical method of repair for Stahls ear: A case report and review of current treatment modalities. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:566569. 10. Yanai A, Tange I, Bandoh Y, Tsuzuki K, Sugino H, Nagata S. Our method of correcting cryptotia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1988; 82:965972. 11. Al-Qattan MM. Cosman (question mark) ear: Congenital auricular cleft between the fifth and sixth hillocks. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:439441. 12. Matsuo K, Hirose T, Tomono T, et al. Non-surgical correction of congenital auricular deformities in the early neonate: A preliminary report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:3851. 13. Grayson B. Personal communication; 2011. 14. Reinisch JF, Lewin S. Ear reconstruction using a porous polyethylene framework and temporoparietal fascia flap. Facial Plast Surg. 2009;25:181189. 15. Park C. Subfascial expansion and expanded two-flap method for microtia reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;106: 14731487. 16. Nagata S. A new method of total reconstruction of the auricle for microtia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1993;92:187201. 17. Nagata S. Modification of the stages in total reconstruction of the auricle: Part II. Grafting the three-dimensional costal cartilage framework for concha-type microtia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:231242; discussion 267268. 18. Nagata S. Modification of the stages in total reconstruction of the auricle: Part III. Grafting the three-dimensional costal cartilage framework for small concha-type microtia. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:243253; discussion 267268. 19. Firmin F. Paper presented at: Plastic Surgery 2011: 80th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, in Denver, Colorado, September 23 through 27, 2011. 20. Thorne CH, Brecht LE, Bradley JP, Levine JP, Hammerschlag P, Longaker MT. Auricular reconstruction: Indications for autogenous and prosthetic techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:12411252. 21. Brent B. Auricular repair with autogenous rib cartilage grafts: Two decades of experience with 600 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1992;90:355374; discussion 375376. 22. Tanzer RC. Total reconstruction of the auricle: A 10-year report. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967;40:547550. 23. Firmin F. Ear reconstruction in cases of typical microtia: Personal experience based on 352 microtic ear corrections. Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 1998;32:3547. 24. Wilkes GH, Wolfaardt JF. Osseointegrated alloplastic versus autogenous ear reconstruction: Criteria for treatment selection. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1994;93:967979. 25. Antia NH, Buch VI. Chondrocutaneous advancement flap for the marginal defect of the ear. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1967; 39:472477.

716e

You might also like

- HTLVNekomancers Grimoireversion9881Document199 pagesHTLVNekomancers Grimoireversion9881ボスぴこぴこNo ratings yet

- Temple Grandin - Animals in TranslationDocument1,774 pagesTemple Grandin - Animals in TranslationВита КинсNo ratings yet

- Essential Tissue Healing of the Face and NeckFrom EverandEssential Tissue Healing of the Face and NeckRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Jose Luis Merlin-Evocation-SheetMusicTradeComDocument1 pageJose Luis Merlin-Evocation-SheetMusicTradeComrafafpsNo ratings yet

- External Parts of FishDocument18 pagesExternal Parts of FishHazel Leah KhaeNo ratings yet

- EMILY West Village MenuDocument1 pageEMILY West Village MenuZagatBlogNo ratings yet

- Ear Deformities Otoplasty and Ear Reconstruction LOVDocument16 pagesEar Deformities Otoplasty and Ear Reconstruction LOVAndy HongNo ratings yet

- Otoplasty Surgical TechniqueDocument12 pagesOtoplasty Surgical TechniqueHNo ratings yet

- Cleft Lip and Palate Management: A Comprehensive AtlasFrom EverandCleft Lip and Palate Management: A Comprehensive AtlasRicardo D. BennunNo ratings yet

- GenioplastyDocument11 pagesGenioplastyMohamed El-shorbagyNo ratings yet

- Surgical Incision Head & NeckDocument31 pagesSurgical Incision Head & Neckromzikerenz0% (1)

- Cervicofacial LymphangiomasDocument11 pagesCervicofacial LymphangiomasCharmila Sari100% (1)

- Parotidectomy: H.Shameer AhamedDocument47 pagesParotidectomy: H.Shameer AhamedAndreas RendraNo ratings yet

- Examination of Head and Neck SwellingsDocument22 pagesExamination of Head and Neck SwellingsObehi EromoseleNo ratings yet

- Surgical Management of Thyroid NeoplasmsDocument15 pagesSurgical Management of Thyroid NeoplasmsalameluNo ratings yet

- Retropharyngeal Abscess: Shumaila Ather 5-1/2012/070Document21 pagesRetropharyngeal Abscess: Shumaila Ather 5-1/2012/070Essam Hassan KhanNo ratings yet

- Microtia Recon Slides 0410Document31 pagesMicrotia Recon Slides 0410Josue Salinas SantosNo ratings yet

- Submental Flap in Head and Neck Reconstruction An Alternative To Microsurgical Flap - February - 2020 - 1580559115 - 2824301Document3 pagesSubmental Flap in Head and Neck Reconstruction An Alternative To Microsurgical Flap - February - 2020 - 1580559115 - 2824301Karan HarshavardhanNo ratings yet

- Le Fort FracturesDocument105 pagesLe Fort FracturesnasimNo ratings yet

- Recent Advances in The Treatment of FracturesDocument29 pagesRecent Advances in The Treatment of Fracturesmanjunatha100% (1)

- Parotidectomy: Anatomy and PhysiologyDocument5 pagesParotidectomy: Anatomy and PhysiologyAgung Choro de ObesNo ratings yet

- Tissue Flaps: Classification and PrinciplesDocument9 pagesTissue Flaps: Classification and PrinciplesTaufik HidayantoNo ratings yet

- Surgical Management of Parapharyngeal AbscessDocument3 pagesSurgical Management of Parapharyngeal AbscessmeyNo ratings yet

- External Ear DisordersDocument48 pagesExternal Ear DisordershemaanandhyNo ratings yet

- Plastic Surgery: Acharya Institute of Allied Health Sciences By: Ishika Basak BHA, 2 YrDocument14 pagesPlastic Surgery: Acharya Institute of Allied Health Sciences By: Ishika Basak BHA, 2 Yrlokitoka zigNo ratings yet

- Zygomatic FXDocument9 pagesZygomatic FXAmisha SilwalNo ratings yet

- Alt FlapDocument60 pagesAlt FlapRAJESH YADAVNo ratings yet

- Hand Anatomy and Infections NewDocument29 pagesHand Anatomy and Infections NewSaranya RNo ratings yet

- TympanoplastyDocument4 pagesTympanoplastyMelly Selvia A100% (1)

- Aesthetic, Breast 2001 PDFDocument124 pagesAesthetic, Breast 2001 PDFAhmed AttiaNo ratings yet

- Anatomical Basis Infection Hand FESSHDocument36 pagesAnatomical Basis Infection Hand FESSHProfesseur Christian DumontierNo ratings yet

- Diseases of External EarDocument66 pagesDiseases of External Earalmazmulu76100% (1)

- Mandible FX Slides 040526Document62 pagesMandible FX Slides 040526azharNo ratings yet

- The Tripod FractureDocument2 pagesThe Tripod FractureWilliam CiferNo ratings yet

- Flaps in Head & Neck Reconstruction: Moderator: DR - Arun Kumar .K.V Presenter: DR - Ananth Kumar.G.BDocument78 pagesFlaps in Head & Neck Reconstruction: Moderator: DR - Arun Kumar .K.V Presenter: DR - Ananth Kumar.G.BisabelNo ratings yet

- Suture LectureDocument42 pagesSuture LectureAniz RataniNo ratings yet

- ApertognathiaDocument45 pagesApertognathiabran makmornNo ratings yet

- Mandible ReconstructionDocument137 pagesMandible ReconstructionShouvik Chowdhury100% (1)

- Cleft Rhinoplasty CMEDocument13 pagesCleft Rhinoplasty CMENaveed KhanNo ratings yet

- Non Surgical Treatment Modalities of SCCHN: Presentation by Post Gradute StudentDocument113 pagesNon Surgical Treatment Modalities of SCCHN: Presentation by Post Gradute StudentZubair VajaNo ratings yet

- Cleft Lip PalateDocument54 pagesCleft Lip PalateGladys AilingNo ratings yet

- Forearm FractureDocument21 pagesForearm FractureBagus Yudha PratamaNo ratings yet

- Plastic Surgery: Volume 3: Craniofacial, Head and Neck Surgery and Pediatric Plastic SurgeryDocument23 pagesPlastic Surgery: Volume 3: Craniofacial, Head and Neck Surgery and Pediatric Plastic SurgeryTugce InceNo ratings yet

- "Mid Face Fractures": Class By: Dr. Prateek Tripathy, Mds (Omfs) Senior Lecturer, HDCH BhubaneswarDocument146 pages"Mid Face Fractures": Class By: Dr. Prateek Tripathy, Mds (Omfs) Senior Lecturer, HDCH BhubaneswarAdyasha SahuNo ratings yet

- Volume Facial e IdadeDocument6 pagesVolume Facial e IdadeJeniffer RafaelaNo ratings yet

- Caldwell Luc IncisionDocument3 pagesCaldwell Luc IncisionabdullahNo ratings yet

- Forearm Fracture 1 BismillahDocument17 pagesForearm Fracture 1 Bismillahamel015No ratings yet

- Gox 1 E07 PDFDocument2 pagesGox 1 E07 PDFUmer HussainNo ratings yet

- Suture PresentationDocument46 pagesSuture Presentationammusuma1999No ratings yet

- Mastectomy/ Modified Radical Mastectomy: IndicationsDocument6 pagesMastectomy/ Modified Radical Mastectomy: IndicationsNANDAN RAINo ratings yet

- Amputation, Surgery and RehabilitationDocument46 pagesAmputation, Surgery and RehabilitationPatrick WandellahNo ratings yet

- Ranula - A Case ReportDocument2 pagesRanula - A Case Reportnnmey20100% (1)

- Pectoralis Major Flap-1Document8 pagesPectoralis Major Flap-1Mashood AhmedNo ratings yet

- Maxillary FracturesDocument22 pagesMaxillary FracturesJacqColumnaNo ratings yet

- Colostomy Care1Document25 pagesColostomy Care1Ely FuaNo ratings yet

- Nasal Fractures: Trauma To NoseDocument38 pagesNasal Fractures: Trauma To NoseSindhura ManjunathNo ratings yet

- Sutures and Suturing TechniquesDocument52 pagesSutures and Suturing TechniquesAditi RapriyaNo ratings yet

- Primary Haemangioma of The Skull: Case ReviewDocument3 pagesPrimary Haemangioma of The Skull: Case ReviewSoemantri Doank100% (1)

- Premalignant Conditions of Oral CavityDocument18 pagesPremalignant Conditions of Oral CavityHaneen Masarwa AtamnaNo ratings yet

- Modified and Radical Neck Dissection TechniqueDocument19 pagesModified and Radical Neck Dissection TechniquethtklNo ratings yet

- Microvascular Free Flaps Used in Head and Neck Reconstruction. / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental AcademyDocument97 pagesMicrovascular Free Flaps Used in Head and Neck Reconstruction. / Orthodontic Courses by Indian Dental Academyindian dental academyNo ratings yet

- Orofacial Pain: A Guide to Medications and ManagementFrom EverandOrofacial Pain: A Guide to Medications and ManagementGlenn T. ClarkNo ratings yet

- Ear Deformities, Otoplasty, and Ear Reconstruction.37Document16 pagesEar Deformities, Otoplasty, and Ear Reconstruction.37rafafpsNo ratings yet

- Benign and Premalignant Skin Lesions.31Document11 pagesBenign and Premalignant Skin Lesions.31rafafpsNo ratings yet

- Juan Martin - Guitarra Flamenca - Solos Flamencos - 42 Solos - Nivel 2Document17 pagesJuan Martin - Guitarra Flamenca - Solos Flamencos - 42 Solos - Nivel 2Dima Lababidi100% (3)

- Practice TestDocument6 pagesPractice TestCỏ May MắnNo ratings yet

- Effect of Age and Cut On The Colour of Turkey, Japanese Quail andDocument3 pagesEffect of Age and Cut On The Colour of Turkey, Japanese Quail andJournal of Environment and Bio-SciencesNo ratings yet

- Idioms and MeaningDocument6 pagesIdioms and MeaningJayden Oliver-CommeyNo ratings yet

- Komparativ - Ednoslozni PridavkiDocument7 pagesKomparativ - Ednoslozni Pridavkiapi-267719463No ratings yet

- Romero Lisbeth - Superlatives and Comparatives ActivityDocument3 pagesRomero Lisbeth - Superlatives and Comparatives ActivityLisbeth RomeroNo ratings yet

- Primitive TransportDocument21 pagesPrimitive TransportAnonymous dmhNTy100% (1)

- Animals MigrationDocument10 pagesAnimals MigrationSvetlana TerzicNo ratings yet

- Diffusion, Exchange & Transport of O2 & Co2Document79 pagesDiffusion, Exchange & Transport of O2 & Co2Darshika Vyas MohanNo ratings yet

- Bee Hive Supplies 2018 CatalogueDocument25 pagesBee Hive Supplies 2018 Catalogueabuye aberaNo ratings yet

- Other Gazette 145-12Document1 pageOther Gazette 145-12Dalhousie GazetteNo ratings yet

- Mammals 2Document2 pagesMammals 2Tien NguyenNo ratings yet

- Price Change by CPDocument3 pagesPrice Change by CPAung Phyoe ThetNo ratings yet

- Taylor & Francis, LTD., Folklore Enterprises, Ltd. FolkloreDocument19 pagesTaylor & Francis, LTD., Folklore Enterprises, Ltd. FolkloreLobsang YeshiNo ratings yet

- DredgeburgDocument20 pagesDredgeburgStoner SomNo ratings yet

- Food Related Interactions: Grade 6Document14 pagesFood Related Interactions: Grade 6primal100% (2)

- Leucodepletion Filter PDFDocument29 pagesLeucodepletion Filter PDFmukeshNo ratings yet

- CVS and RSDocument132 pagesCVS and RSclareawambuiNo ratings yet

- Tuberculosis UNIVALLEDocument33 pagesTuberculosis UNIVALLEPaz VidaNo ratings yet

- Government of West Bengal Health & Family Welfare Department WWW - Wbhealth.gov - in BulletinDocument2 pagesGovernment of West Bengal Health & Family Welfare Department WWW - Wbhealth.gov - in BulletinCSE GR-1No ratings yet

- Legendary Entertainer Ann-MargretDocument2 pagesLegendary Entertainer Ann-MargretA Distinctive Style100% (1)

- Novel Sheet For Lord of The FliesDocument5 pagesNovel Sheet For Lord of The FliesAlexa SchultzNo ratings yet

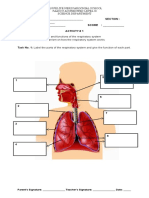

- Activity Sheet Body SystemDocument8 pagesActivity Sheet Body Systemapi-340406981No ratings yet

- 101 Modul Hebat Bio 2021 - PDF - Eng-65-70Document6 pages101 Modul Hebat Bio 2021 - PDF - Eng-65-70BF CLNo ratings yet

- Milk Microbiology: Viable Count Method Dye Reduction Test Direct Microscopic CountDocument14 pagesMilk Microbiology: Viable Count Method Dye Reduction Test Direct Microscopic CountDayledaniel SorvetoNo ratings yet

- Soal AnimalDocument5 pagesSoal AnimalAndy LuthNo ratings yet

- Med-RM Bot SP-3 AnswersDocument7 pagesMed-RM Bot SP-3 Answerskrish masterjee100% (1)