Political Economy

Political Economy

Uploaded by

Bernard OkpeCopyright:

Available Formats

Political Economy

Political Economy

Uploaded by

Bernard OkpeOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Political Economy

Political Economy

Uploaded by

Bernard OkpeCopyright:

Available Formats

Political economy

Political economy was the original term used for studying production and trade, and their relations with

law, custom, and government, as well as with the distribution of national income and wealth. Political

economy originated in moral philosophy. It was developed in the 18th century as the study of the

economies of states, or polities, hence the term political economy.

In the late 19th century, the term economics came to replace political economy, coinciding with the

publication of an influential textbook by Alfred Marshall in 1890.[1] Earlier, William Stanley Jevons, a

proponent of mathematical methods applied to the subject, advocated economics for brevity and with

the hope of the term becoming "the recognised name of a science."[2][3]

Today, political economy, where it is not used as a synonym for economics, may refer to very different

things, including Marxian analysis, applied public-choice approaches emanating from the Chicago school

and the Virginia school, or simply the advice given by economists to the government or public on

general economic policy or on specific proposals.[3] A rapidly growing mainstream literature from the

1970s has expanded beyond the model of economic policy in which planners maximize utility of a

representative individual toward examining how political forces affect the choice of economic policies,

especially as to distributional conflicts and political institutions.[4] It is available as an area of study in

certain colleges and universities.

Contents

1 Etymology

2 Current approaches

3 Related disciplines

4 See also

5 Notes

6 References

7 Journals

8 External links

Etymology

Originally, political economy meant the study of the conditions under which production or consumption

within limited parameters was organized in nation-states. In that way, political economy expanded the

emphasis of economics, which comes from the Greek oikos (meaning "home") and nomos (meaning

"law" or "order"); thus political economy was meant to express the laws of production of wealth at the

state level, just as economics was the ordering of the home. The phrase conomie politique (translated

in English as political economy) first appeared in France in 1615 with the well-known book by Antoine de

Montchrtien, Trait de leconomie politique. The French physiocrats, Adam Smith, David Ricardo, and

German philosopher and social theorist Karl Marx were some of the exponents of political economy. The

world's first professorship in political economy was established in 1754 at the University of Naples

Federico II, Italy (then capital city of the Kingdom of Naples); the Neapolitan philosopher Antonio

Genovesi was the first tenured professor; in 1763, Joseph von Sonnenfels was appointed a Political

Economy chair at the University of Vienna, Austria. In 1805, Thomas Malthus became England's first

professor of political economy, at the East India Company College, Haileybury, Hertfordshire. Glasgow

University, where Smith was Professor of Logic and of Moral Philosophy, changed the name of its

Department of Political Economy to the Department of Economics (ostensibly to avoid confusing

prospective undergraduates) in the academic year 199798, leaving the class of 1998 as the last to be

graduated with a Master of Arts (Scotland) in Political Economy.

In the United States, political economy first was taught at the College of William and Mary, where in

1784, Smith's The Wealth of Nations was a required textbook.[5]

Current approaches

Robert Keohane, international relations theorist

In its contemporary meaning, political economy refers to different, but related, approaches to studying

economic and related behaviours, ranging from the combination of economics with other fields to the

use of different, fundamental assumptions that challenge earlier economic assumptions:

Political economy most commonly refers to interdisciplinary studies drawing upon economics, sociology,

and political science in explaining how political institutions, the political environment, and the economic

systemcapitalist, socialist, or mixedinfluence each other.[6] The Journal of Economic Literature

classification codes associate political economy with three subareas: the role of government and/or

power relationships in resource allocation for each type of economic system,[7] international political

economy, which studies the economic impacts of international relations,[8] and economic models of

political processes.[9] The last area, derived from public choice theory and dating from the 1960s,

models voters, politicians, and bureaucrats as behaving in mainly self-interested ways, in contrast to a

view, ascribed to earlier economists, of government officials trying to maximize individual utilities from

some kind of social welfare function.[10] An early and continuing focus of that research program is what

came to be called constitutional political economy.[11]

Economists and political scientists often associate political economy with approaches using rational-

choice assumptions,[12] especially in game theory,[13] and in examining phenomena beyond

economics' standard remit, such as government failure and complex decision making in which context

the term "positive political economy" is common.[14] Other "traditional" topics include analysis of such

public policy issues as economic regulation,[15] monopoly, rent-seeking, market protection,[16]

institutional corruption,[17] and distributional politics.[18] Empirical analysis includes the influence of

elections on the choice of economic policy, determinants and forecasting models of electoral outcomes,

the political business cycles,[19] central-bank independence, and the politics of excessive deficits.[20]

A recent focus has been on modeling economic policy and political institutions as to interactions

between agents and economic and political institutions,[21] including the seeming discrepancy of

economic policy and economist's recommendations through the lens of transaction costs.[22] From the

mid-1990s, the field has expanded, in part aided by new cross-national data sets that allow tests of

hypotheses on comparative economic systems and institutions.[23] Topics have included the breakup of

nations,[24] the origins and rate of change of political institutions in relation to economic growth,[25]

development,[26] backwardness,[27] reform,[28] and transition economies,[29] the role of culture,

ethnicity, and gender in explaining economic outcomes,[4] macroeconomic policy,[30] the

environment,[31] fairness,[32] the relation of constitutions to economic policy, theoretical[33] and

empirical.[34]

New political economy may treat economic ideologies as the phenomenon to explain, per the traditions

of Marxian political economy. Thus, Charles S. Maier suggests that a political economy approach

"interrogates economic doctrines to disclose their sociological and political premises.... in sum, [it]

regards economic ideas and behavior not as frameworks for analysis, but as beliefs and actions that

must themselves be explained."[35] This approach informs Andrew Gamble's The Free Economy and the

Strong State (Palgrave Macmillan, 1988), and Colin Hay's The Political Economy of New Labour

(Manchester University Press, 1999). It also informs much work published in New Political Economy, an

international journal founded by Sheffield University scholars in 1996.[36]

International political economy (IPE) is an interdisciplinary field comprising approaches to the actions of

various actors. In the United States, these approaches are associated with the journal International

Organization, which in the 1970s became the leading journal of IPE under the editorship of Robert

Keohane, Peter J. Katzenstein, and Stephen Krasner. They are also associated with the journal The

Review of International Political Economy. There also is a more critical school of IPE, inspired by Karl

Polanyi's work; two major figures are Matthew Watson and Robert W. Cox.[37]

Anthropologists, sociologists, and geographers use political economy in referring to the regimes of

politics or economic values that emerge primarily at the level of states or regional governance, but also

within smaller social groups and social networks. Because these regimes influence and are influenced by

the organization of both social and economic capital, the analysis of dimensions lacking a standard

economic value (e.g., the political economy of language, of gender, or of religion) often draws on

concepts used in Marxian critiques of capital. Such approaches expand on neo-Marxian scholarship

related to development and underdevelopment postulated by Andr Gunder Frank and Immanuel

Wallerstein.

Historians have employed political economy to explore the ways in the past that persons and groups

with common economic interests have used politics to effect changes beneficial to their interests.[38]

Related disciplines

Because political economy is not a unified discipline, there are studies using the term that overlap in

subject matter, but have radically different perspectives:

Sociology studies the effects of persons' involvement in society as members of groups, and how that

changes their ability to function. Many sociologists start from a perspective of production-determining

relation from Karl Marx. Marx's theories on the subject of political economy are contained in his book

Das Kapital.

Anthropology studies political economy by investigating regimes of political and economic value that

condition tacit aspects of sociocultural practices (e.g., the pejorative use of pseudo-Spanish expressions

in the US entertainment media) by means of broader historical, political, and sociological processes.

Analyses of structural features of transnational processes focus on the interactions between the world

capitalist system and local cultures.

Archaeology attempts to reconstruct past political economies by examining the material evidence for

administrative strategies to control and mobilize resources.[39] This evidence may include architecture,

animal remains, evidence for craft workshops, evidence for feasting and ritual, evidence for the import

or export of prestige goods, or evidence for food storage.

Psychology is the fulcrum on which political economy exerts its force in studying decision making (not

only in prices), but as the field of study whose assumptions model political economy.

History documents change, often using it to argue political economy; some historical works take political

economy as the narrative's frame.

Human geography at times draws on theories of politico-economic processes. Typically under the

moniker of political ecology, political ecology has been used by geographers to understand human

systems and their relationship with the environment, broadly defined.[40]

Ecology deals with political economy, because human activity has the greatest effect upon the

environment, its central concern being the environment's suitability for human activity. The ecological

effects of economic activity spur research upon changing market economy incentives.

Cultural studies examines social class, production, labor, race, gender, and sex.

Communications examines the institutional aspects of media and telecommuncation systems. As the

area of study focusing on aspects of human communication, it pays particular attention to the

relationships between owners, labor, consumers, advertisers, structures of production, and the state,

and the power relationships embedded in these relationships.

Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Political_economy&printable=yes

You might also like

- The Multifaceted Nature of Civic Participation: A Literature ReviewDocument73 pagesThe Multifaceted Nature of Civic Participation: A Literature ReviewwfshamsNo ratings yet

- B1 End of Year Test Answer Key HigherDocument3 pagesB1 End of Year Test Answer Key HigherXime Olariaga100% (1)

- Rita Lee ResumeDocument2 pagesRita Lee Resumeapi-650394296No ratings yet

- New International Political EconomyDocument8 pagesNew International Political Economybasantjain1987100% (1)

- Rostow ModelDocument4 pagesRostow ModeltubenaweambroseNo ratings yet

- Types of Government: For A Few Countries More Than One Definition AppliesDocument3 pagesTypes of Government: For A Few Countries More Than One Definition AppliesSimona OlteanuNo ratings yet

- Decentralization Is The Process of Redistributing or Dispersing Functions, Powers, People or Things AwayDocument7 pagesDecentralization Is The Process of Redistributing or Dispersing Functions, Powers, People or Things AwayKunal098No ratings yet

- Political SocializationDocument96 pagesPolitical SocializationMelchizedek Beton OmandamNo ratings yet

- Dependency Theory Vs Modernization TheoryDocument2 pagesDependency Theory Vs Modernization TheoryMarjan ArbabNo ratings yet

- Cultural ImperialismDocument7 pagesCultural ImperialismJohny RosarioNo ratings yet

- Global South Versus Third WorldDocument9 pagesGlobal South Versus Third WorldKaryl CrystalNo ratings yet

- International Political EconomyDocument9 pagesInternational Political Economylkg3000No ratings yet

- Contemporary Global Governance FinalDocument18 pagesContemporary Global Governance FinalNikho Schin ValleNo ratings yet

- Economy of PhilippinesDocument9 pagesEconomy of PhilippinesVon Wilson AjocNo ratings yet

- Capitalism Vs SocialismDocument20 pagesCapitalism Vs SocialismShashank Shekhar Mishra100% (1)

- Comparative Public PolicyDocument20 pagesComparative Public PolicyWelly Putra JayaNo ratings yet

- Imperialism: HistoryDocument7 pagesImperialism: HistorysandhyaNo ratings yet

- Notes On The Historical Evolution of International PoliticsDocument10 pagesNotes On The Historical Evolution of International PoliticsDanielNo ratings yet

- Introduction To International Relations Course SyllabusDocument6 pagesIntroduction To International Relations Course Syllabusdov_waxmanNo ratings yet

- Political Economy SyllabusDocument7 pagesPolitical Economy SyllabusApril Gay PugongNo ratings yet

- Vincent Ferraro - Dependency TheoryDocument8 pagesVincent Ferraro - Dependency TheoryTolessaNo ratings yet

- International Relations OutlineDocument42 pagesInternational Relations OutlineIsaac Ip100% (1)

- Globalization: Globalization, As Is Implied by The Word Itself, Is The Is The Process of Integration of SocietiesDocument2 pagesGlobalization: Globalization, As Is Implied by The Word Itself, Is The Is The Process of Integration of SocietiesSorina MariaNo ratings yet

- World System TheoryDocument27 pagesWorld System TheoryThales MacêdoNo ratings yet

- Theory of The State OutlineDocument44 pagesTheory of The State OutlineDayyanealos100% (1)

- Dependency Theory: (Or: Media System Dependency Theory) History and OrientationDocument4 pagesDependency Theory: (Or: Media System Dependency Theory) History and OrientationeaberaNo ratings yet

- Dependency Theory How Relevant Is It Today-AJSen-08Document13 pagesDependency Theory How Relevant Is It Today-AJSen-08ANshutosh Sharma100% (1)

- Heywood CHP 1 What Is PoliticsDocument24 pagesHeywood CHP 1 What Is PoliticsAlper Tunga GüngörNo ratings yet

- The Normative Media TheoriesDocument42 pagesThe Normative Media TheoriesMUNYAWIRI MCDONALDNo ratings yet

- Cultural ImperialismDocument6 pagesCultural Imperialismarwen222No ratings yet

- A Presentation in Political Science 004 A Presentation in Political Science 004 by Jeremiah Carlos by Jeremiah CarlosDocument26 pagesA Presentation in Political Science 004 A Presentation in Political Science 004 by Jeremiah Carlos by Jeremiah CarlosJeremiah Carlos0% (1)

- Third WorldDocument11 pagesThird WorldNeha Jayaraman100% (1)

- Marxist Theory of International Relations-PPT-16Document16 pagesMarxist Theory of International Relations-PPT-16Keith Knight67% (3)

- Jean Francois LyotardDocument5 pagesJean Francois LyotardCorey Mason-SeifertNo ratings yet

- 23 1gudinaDocument27 pages23 1gudinaAmbachew A. AnjuloNo ratings yet

- NeoColonialism AssignmentDocument3 pagesNeoColonialism AssignmentEve Grace SohoNo ratings yet

- 1 Intro To GovernmentDocument87 pages1 Intro To GovernmentJessicaNo ratings yet

- PAPER-1 - Political Science PDFDocument76 pagesPAPER-1 - Political Science PDFVishal TiwariNo ratings yet

- Three Core Values of DevelopmentDocument1 pageThree Core Values of DevelopmentAsh kaliNo ratings yet

- Globalization and Its Discontents: Joseph StiglitzDocument22 pagesGlobalization and Its Discontents: Joseph StiglitzSwapnil Mehare100% (1)

- Effects of Globalization On SocietyDocument7 pagesEffects of Globalization On SocietyIrfan KhanNo ratings yet

- Impacts of Neoliberalism On Development 1Document8 pagesImpacts of Neoliberalism On Development 1Damilola Ade-OdiachiNo ratings yet

- Politics and Leadership StructureDocument33 pagesPolitics and Leadership StructureClaud LiwanagNo ratings yet

- Capitalism Vs Socialism'Document7 pagesCapitalism Vs Socialism'ejaz_balti_1No ratings yet

- Estimation and ProblemsDocument18 pagesEstimation and ProblemsAyush SonthaliaNo ratings yet

- Machiavelli ReportDocument2 pagesMachiavelli Reportjm_omega23No ratings yet

- Ten Principles of EconomicsDocument5 pagesTen Principles of EconomicsANo ratings yet

- Torture Position PaperDocument1 pageTorture Position Paperapi-305211715No ratings yet

- Tradition: ThemesDocument11 pagesTradition: ThemesSheryl C. BalmesNo ratings yet

- Mercantilism Mercantilist Use On International TheoryDocument9 pagesMercantilism Mercantilist Use On International TheoryUdhaya KumarNo ratings yet

- Demand TheoryDocument19 pagesDemand TheoryRohit Goyal100% (1)

- Almond A Discipline Divided ReviewDocument7 pagesAlmond A Discipline Divided ReviewCristinaRusuNo ratings yet

- The Globalization of World Politics EIGH-48-63Document16 pagesThe Globalization of World Politics EIGH-48-63Tatiana Peña Rey100% (1)

- Chapter 1 - Introduction To GlobalizationDocument10 pagesChapter 1 - Introduction To GlobalizationEricaNo ratings yet

- Unit I Introduction To GlobalizationDocument6 pagesUnit I Introduction To GlobalizationArianne FloresNo ratings yet

- Karl MarxDocument10 pagesKarl MarxKasturi Samant100% (1)

- Under Spanish ColonialismDocument82 pagesUnder Spanish ColonialismCiara Janine MeregildoNo ratings yet

- Meaning and Definition of Public Administration PDFDocument3 pagesMeaning and Definition of Public Administration PDFPratima MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Phil EconomyDocument6 pagesPhil EconomyDrey TabilogNo ratings yet

- Neocolonialism FinalDocument23 pagesNeocolonialism FinalGabrielle CatalanNo ratings yet

- A Cosmopolitanism of Nations: Giuseppe Mazzini's Writings on Democracy, Nation Building, and International RelationsFrom EverandA Cosmopolitanism of Nations: Giuseppe Mazzini's Writings on Democracy, Nation Building, and International RelationsNo ratings yet

- FDI NoteDocument4 pagesFDI NoteBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Business Cycle PDFDocument15 pagesBusiness Cycle PDFBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Extreme Value TheoremDocument5 pagesExtreme Value TheoremBernard Okpe100% (1)

- Monetary PolicyDocument17 pagesMonetary PolicyBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Likelihood Ratio TestDocument6 pagesLikelihood Ratio TestBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Lange ModelDocument6 pagesLange ModelBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Modern Portfolio TheoryDocument16 pagesModern Portfolio TheoryBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- TaxationDocument20 pagesTaxationBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Short Run EquilibriumDocument5 pagesShort Run EquilibriumBernard Okpe100% (2)

- Monetary Economics Is A Branch ofDocument2 pagesMonetary Economics Is A Branch ofBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- OLIGOPSONYDocument3 pagesOLIGOPSONYBernard Okpe100% (1)

- Oligopoly:: Firm Industry Monopoly Monopolistic CompetitionDocument19 pagesOligopoly:: Firm Industry Monopoly Monopolistic CompetitionBernard Okpe100% (2)

- Compare and Contrast Classical Theory of Interest Rate and Keynesian Theory of InterestDocument9 pagesCompare and Contrast Classical Theory of Interest Rate and Keynesian Theory of InterestBernard Okpe83% (6)

- Validity Concepts in ResearchDocument8 pagesValidity Concepts in ResearchBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Development EconomicsDocument3 pagesDevelopment EconomicsBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Research Ethics Involves The Application of FundamentalDocument3 pagesResearch Ethics Involves The Application of FundamentalBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Introduction To International Economic SystemDocument16 pagesIntroduction To International Economic SystemBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Assignment On Natural Resource Economics 11 (ECN 315)Document16 pagesAssignment On Natural Resource Economics 11 (ECN 315)Bernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Cover PageDocument1 pageCover PageBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Quantity Theory of MoneyDocument6 pagesQuantity Theory of MoneyBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Development EconomicsDocument3 pagesDevelopment EconomicsBernard OkpeNo ratings yet

- Professional Practice: Codes of EthicsDocument7 pagesProfessional Practice: Codes of EthicsXTINCT Mobile LegendsNo ratings yet

- MA3JJC74WPF133176 FASTag Statement 1692263541213Document2 pagesMA3JJC74WPF133176 FASTag Statement 1692263541213bharani.mudomsNo ratings yet

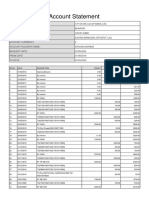

- Account StatementDocument22 pagesAccount Statement18 Shivam SharmaNo ratings yet

- Consent FormDocument2 pagesConsent FormjijibnjiamNo ratings yet

- There Must Be Three or More Continuous Spans in Each DirectionDocument35 pagesThere Must Be Three or More Continuous Spans in Each DirectionKawan EngNo ratings yet

- 143Document2 pages143Dominic VillalbaNo ratings yet

- PCS 7 Advanced Process Library (V9.1 SP2) 0-3022 ALLDocument3,022 pagesPCS 7 Advanced Process Library (V9.1 SP2) 0-3022 ALLÖmer Faruk TemurNo ratings yet

- Nonlinear Mathematical Model Explains How AcupunctureDocument10 pagesNonlinear Mathematical Model Explains How Acupunctureveragomes5787No ratings yet

- Nicolas Carrillo Phet Simulation - Gases Intro - StudentsDocument7 pagesNicolas Carrillo Phet Simulation - Gases Intro - StudentsnicolaswcarrilloNo ratings yet

- Publishedpaper GraniteDocument15 pagesPublishedpaper GranitezakariaalbashiriNo ratings yet

- Control Systems: Lect.8 Root Locus TechniquesDocument49 pagesControl Systems: Lect.8 Root Locus Techniqueskhaled jNo ratings yet

- 01 - List of Machines-Vasai PlantDocument1 page01 - List of Machines-Vasai PlantPress TechNo ratings yet

- House Inspection PDFDocument7 pagesHouse Inspection PDFAnonymous fLKJg0No ratings yet

- Inspiring Design QuotesDocument51 pagesInspiring Design Quotespoonam_ranee3934No ratings yet

- Comac - BMG Sanitizer PDFDocument28 pagesComac - BMG Sanitizer PDFUdit KhannaNo ratings yet

- LA Trobe UniversityDocument1 pageLA Trobe UniversityBaba SitaramNo ratings yet

- How Much Poly-Fill Do I Need For A Sealed Subwoofer - BoomSpeakerDocument7 pagesHow Much Poly-Fill Do I Need For A Sealed Subwoofer - BoomSpeakerPeterNo ratings yet

- Cross Cultural CounsellingDocument17 pagesCross Cultural CounsellingSonya PompeyNo ratings yet

- Technology StreamDocument51 pagesTechnology StreamBudi SaputroNo ratings yet

- Light-Reflection & Refraction - Practice Sheet - 10th Board Booster 2.0 2024Document5 pagesLight-Reflection & Refraction - Practice Sheet - 10th Board Booster 2.0 2024yashasvisharma sharmaNo ratings yet

- Exo UnileverDocument4 pagesExo UnileverfadilaNo ratings yet

- Francis Ran A Good Race That We Won't Forget: Honouring A Great LeaderDocument56 pagesFrancis Ran A Good Race That We Won't Forget: Honouring A Great LeaderKiwanuka AugustineNo ratings yet

- Triple S Truck Repair Jan 2019 To April 30 2020Document3 pagesTriple S Truck Repair Jan 2019 To April 30 2020sidhuNo ratings yet

- SLE123 - Sample Quiz 05 QuestionsDocument14 pagesSLE123 - Sample Quiz 05 QuestionsNinaNo ratings yet

- 312 BDocument2 pages312 BДрагиша Небитни Трифуновић33% (3)

- Ufc 3 400 02 2018 PDFDocument89 pagesUfc 3 400 02 2018 PDFMohsin ShaikhNo ratings yet

- Akbar Anwari CVDocument6 pagesAkbar Anwari CVafshananwari296No ratings yet

- Download Full Handbook of Reinforcement Learning and Control: 325 (Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, 325) Kyriakos G. Vamvoudakis (Editor) PDF All ChaptersDocument50 pagesDownload Full Handbook of Reinforcement Learning and Control: 325 (Studies in Systems, Decision and Control, 325) Kyriakos G. Vamvoudakis (Editor) PDF All Chaptersaseniajuvdal37100% (1)