100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

263 viewsAlchemy Restored - Lawrence M. Principe

Alchemy Restored - Lawrence M. Principe

Uploaded by

FelipeAlchemy's exile as a "pseudoscience" or worse was created in the eighteenth century. Principe: alchemy now holds an important place in the history of science. He says Alchemists have rehabilitated their status by studying the documentary sources.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Alchemy Restored - Lawrence M. Principe

Alchemy Restored - Lawrence M. Principe

Uploaded by

Felipe100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

263 views9 pagesAlchemy's exile as a "pseudoscience" or worse was created in the eighteenth century. Principe: alchemy now holds an important place in the history of science. He says Alchemists have rehabilitated their status by studying the documentary sources.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Alchemy's exile as a "pseudoscience" or worse was created in the eighteenth century. Principe: alchemy now holds an important place in the history of science. He says Alchemists have rehabilitated their status by studying the documentary sources.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

100%(1)100% found this document useful (1 vote)

263 views9 pagesAlchemy Restored - Lawrence M. Principe

Alchemy Restored - Lawrence M. Principe

Uploaded by

FelipeAlchemy's exile as a "pseudoscience" or worse was created in the eighteenth century. Principe: alchemy now holds an important place in the history of science. He says Alchemists have rehabilitated their status by studying the documentary sources.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 9

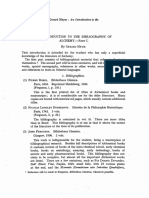

Alchemy Restored

Author(s): LawrenceM. Principe

Source: Isis, Vol. 102, No. 2 (June 2011), pp. 305-312

Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The History of Science Society

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/660139 .

Accessed: 29/08/2011 16:19

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press and The History of Science Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to Isis.

http://www.jstor.org

Alchemy Restored

By Lawrence M. Principe*

ABSTRACT

Alchemy now holds an important place in the history of science. Its current status

contrasts with its former exile as a pseudoscience or worse and results from several

rehabilitative steps carried out by scholars who made closer, less programmatic, and more

innovative studies of the documentary sources. Interestingly, alchemys outcast status was

created in the eighteenth century and perpetuated thereafter in part for strategic and

polemical reasonsand not only on account of a lack of historical understanding.

Alchemys return to the fold of the history of science highlights important features about

the development of science and our changing understanding of it.

P

ROBABLY THE LAST ACADEMIC ORATION ABOUT ALCHEMY given in the

Netherlands took place at Leiden in December 1737. The speaker was the physician

Abraham Kaau, and he entitled his address On the Joys of the Alchemists.

1

While the

title might seem to promise a positive portrayal of alchemy, Kaaus oration was in fact a

mocking account of the ancient art, and one can imagine his audiences laughter at

alchemys expense. By 1737, in the Netherlands at least, alchemy had no serious public

defenders. The subject had become emblematic of foolishness, a relic of the past, a source

of amusing entertainment (as Kaau used it), or an example of what chemistry was not. In

1737, chemistry was a serious academic discipline and an increasingly important com-

mercial practice, and in Kaaus mind alchemy had very little connection with it.

This was not the case just twenty years earlier. In September 1718, an earlier generation

of Leiden professors had gathered to hear the inaugural oratie of their newly appointed

professor of chemistry. This new chemistry professor was, ironically enough, Abraham

Kaaus uncle and a much more famous personHerman Boerhaave. In 1718, the trans-

mutation of metals into gold remained a serious topic of study for many and one of the

enterprises that most readily characterized chemistry for the general public. Boerhaave did

not mock chemistrys past, but he did nd it necessary to apologize for it. Entitled

Chemistry Purging Itself of Its Errors, his oration defended chemistry from critics. I

* Department of the History of Science and Technology and Department of Chemistry, 301 Gilman Hall,

Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland 21218.

1

Abraham Kaau, Declaratio academica de gaudiis alchemistarum, in Perspiratio dicta Hippocrati (Leiden,

1738). I exclude from the list of Dutch alchemical orationes inaugurales the oratie I gave at Utrecht University

on 1 June 2010, which forms a basis for the present essay.

F

O

C

U

S

Isis, 2011, 102:305312

2011 by The History of Science Society. All rights reserved.

0021-1753/2011/10202-0005$10.00

305

must talk about chemistry! Boerhaave lamented. About chemistry! A subject disagree-

able, vulgar, laborious, far from the affairs of intelligent people, and ignored or considered

suspect by the learned . . . a discipline fruitful of errors, the poorest in good fruit, the

progenitor of poverty, the bankruptor of wealth, the destruction and ruin of common

sense.

2

Boerhaave was both embarrassed by and proud of chemistry. We are horried and

embarrassed by the silly nonsense into which the crowd of chemists plunges with sinful

trespass. What fables, superstititions, and fancies! Hardly anywhere can more raving

madness be found. His words are understandable only when we recognize that many in

his audience did not see a clear distinction between what we call alchemy and chemistry.

The search for metallic transmutationwhat we call alchemy but that is more accu-

rately termed chrysopoeiawas ordinarily viewed in the late seventeenth century as

synonymous with or as a subset of chemistry. This terminological issue is why William

Newman and I suggested using the archaically spelled chymistry to refer to the entire

subject before its separation into alchemy and chemistry in the early eighteenth century.

3

Many chymists pursued chrysopoeia as part of their activities, and in doing so they

employed the same techniques, instruments, and guiding principles as in the rest of their

work. All their chymical activities were unied by a common focus on the analysis,

synthesis, transformation, and production of material substances. The sundering of chryso-

poeia from chymistry was under way when Boerhaave spoke in 1718, and he is among

those who promoted it, explaining that the new chemists of his daylike himselfwere

busy making their subject respectable and that his colleagues had nothing to fear from this

questionable subject.

The banishment of chrysopoeiaincreasingly called alchemy in the early eighteenth

centuryfrom respectable chemistry remains a topic of study. Yet it is clear that devel-

opments in the understanding of nature had little to do with it. No new theories or

experiments sounded the death knell for chrysopoeia, and the arguments used against it in

the 1720s were the same as those used routinely and ineffectively since the Middle Ages.

Early eighteenth-century antialchemical rhetoric, however, laid new emphasis on fraud-

ulent practices. It was spokesmen for scientic societies and institutionslike Bernard de

Fontenelle and E

tienne-Francois Geoffroy at the Academie Royale des Sciences and

Boerhaave at Leidenwhere chemistry was struggling to take on a new identity in terms

of professionalization and social legitimacy, who led the charge. They cast alchemy as an

intellectual taboo, its practitioners as socially unacceptable and disruptive, and its content

and practice as something other than the chemistry they represented. This campaign was

so successful that chrysopoeia disappeared from respectable circles within a generation

(although some of the most prominent eighteenth-century chemists who rejected it

publicly continued to pursue it privately).

4

2

Herman Boerhaave, Sermo academicus de chemia suos errores expurgante (Leiden, 1718), rpt. in Elementa

chemiae, 2 vols. (Paris, 1733), Vol. 2, pp. 6477, on pp. 6566; for an English translation see E. Kegel-

Brinkgreve and Antonie M. Luyendijk-Elshout, eds., Boerhaaves Orations (Leiden: Brill, 1983), pp. 193213.

On Boerhaave see John C. Powers, Inventing Chemistry: Herman Boerhaave and the Reform of the Chemical

Arts (Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press, in press).

3

Boerhaave, Sermo academicus de chemia suos errores expurgante, p. 66; and William R. Newman and

Lawrence M. Principe, Alchemy vs. Chemistry: The Etymological Origins of a Historiographic Mistake, Early

Science and Medicine, 1998, 3:3265.

4

This topic forms one major theme of my forthcoming Wilhelm Homberg and the Transmutations of

Chymistry; for a brief version see Lawrence M. Principe, A Revolution Nobody Noticed? Changes in Early

Eighteenth-Century Chymistry, in New Narratives in Eighteenth-Century Chemistry, ed. Principe (Dordrecht:

306 FOCUSISIS, 102 : 2 (2011)

Subsequent developments made alchemys original unity with chemistryor other

scientic practicesseem increasingly implausible. Late eighteenth-century Germany

saw a resurgence of alchemy, but within secret societies. The late nineteenth century

witnessed a broader revival of alchemy, but within the context of Victorian occultism.

These Victorian occultists reinterpreted alchemy as a spiritual practice, involving the

self-transformation of the practitioner and only incidentally or not at all the transformation

of laboratory substances. Early twentieth-century psychoanalysts reexpressed this occult-

ist interpretation in clinical terms and claimed that alchemical texts actually described

psychological processes and archetypal images. These latter-day interpretations became

standard explanations of historical alchemy, such that with every passing generation

alchemy became more and more distanced from chemistry and from scientic thought in

general.

5

Thus, when the history of science emerged as a professional discipline, alchemy

seemed far from anything scientic. The positivist outlooks of the day recapitulated

Enlightenment polemics, and early historians of science presented alchemy as not simply

nonscientic, but antiscientican obstacle to progress. George Sarton penned an ex-

tended rant against the extraordinary muddle of alchemy and labeled alchemists as all

fools or knaves, or more often a combination of both in various proportions. In 1952

Herbert Buttereld famously wrote that modern scholars who study alchemy end up

tinctured by the same sort of lunacy they set out to describe.

6

(Did he have particular

contemporaries in mind?) Alchemys separation from the history of science thus contin-

ued to deepen for over two centuries.

Remarkably, the speed of alchemys rehabilitation today rivals that of its eighteenth-

century demise. Historians of science are now paying unprecedented attention to alchemy,

and other academic elds are likewise acknowledging its wide inuence and cultural

relevance. Has the entire discipline of the history of science become tinctured by lunacy?

A brief retrospective on alchemys rehabilitationand the opposition to its revival

highlights developments in both our discipline and our wider understanding of science.

Several steps paved the way for alchemys revival. The careful researches of Julius

Ruska, Paul Kraus, and others addressed long-standing biobibliographical problems.

Walter Pagel and Allen Debus championed the importance of iatrochemistry, especially in

the cases of Paracelsus, Van Helmont, and their followers. Few scholars, however, dared

approach European chrysopoeia seriously. Among those who did, Frank Sherwood Tay-

lor, founding editor of Ambix, should be singled out. He wrote his 1952 The Alchemists

with great historical sensitivity, insight, and modesty, endeavoring to understand alche-

mists on their own terms at a time when most others relied on supercial or programmatic

assessments. Such foundational work did not, unfortunately, penetrate far into the eld.

Another key step was the revelation that canonical gures of the Scientic Revolution

pursued chrysopoeia seriously. This development threw steadfast believers in Enlighten-

Springer, 2007), pp. 122, esp. pp. 814; and Principe, Transmuting Chymistry into Chemistry: Eighteenth-

Century Chrysopoeia and Its Repudiation, in Neighbours and Territories: The Evolving Identity of Chemistry,

ed. Jose Ramon Bertomeu-Sanchez, Duncan Thorburn Burns, and Brigitte Van Tiggelen (Louvain-la-Neuve:

Memosciences, 2008), pp. 2134. See also John C. Powers, Ars sine arte: Nicholas Lemery and the End of

Alchemy in Eighteenth-Century France, Ambix, 1998, 45:163189.

5

See Lawrence M. Principe and William R. Newman, Some Problems with the Historiography of Alchemy,

in Secrets of Nature: Astrology and Alchemy in Early Modern Europe, ed. Newman and Anthony Grafton

(Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2001), pp. 385431.

6

George Sarton, Boyle and Bayle: The Sceptical Chemist and the Sceptical Historian, Chymia, 1950,

3:155189, on pp. 161162; and Herbert Buttereld, The Origins of Modern Science, 13001800 (New York:

Macmillan, 1952), p. 98.

F

O

C

U

S

FOCUSISIS, 102 : 2 (2011) 307

ment or positivist rhetoric on the horns of a dilemmaeither alchemy was more rational

than they believed or their heroes were less so. Newtons alchemy would not have become

a cause cele`bre of the 1970s and 1980s had eighteenth-century and subsequent genera-

tions not recrafted Newton into the very model of the modern scientist and presented

alchemy as something removed fromindeed, opposed toscience. Nor would Newtons

alchemy have been kept hidden for so long as an embarrassment. The nineteenth-century

biographer David Brewster recoiled at Newtons voluminous notes on the most con-

temptible alchemical poetry and his study of texts that were the obvious product of a

fool and a knave.

7

The commission that examined Newtons manuscripts for Cambridge

University concluded that the alchemical materials were of very little interest and his

theological work not of any great value. These unimportant materials were returned

to their owner and eventually bundled up into lots for the infamous Sothebys auction of

1936.

8

Study of the alchemical papers gathered by John Maynard Keynes and given to

Cambridge in 1946 was sporadic at rst and sometimes took the form of sifting nuggets

of positive chemistry from mystic alchemy using anachronistic or programmatic

criteriathe latter explained away or more often simply ignored.

9

But thanks to persistent

scholars like R. S. Westfall and B. J. T. Dobbsdespite the then-meager understanding

of alchemy they had to draw on and the criticism they received from more hidebound

historiansit is now common knowledge that Sir Isaac Newtons alchemy occupied him

as seriously as optics or mathematics, just as his theological pursuits rivaled his physics

in terms of the time and energy he spent on them.

10

Robert Boyle received similar treatment. The image crafted for him was that of a

Father of Modern Chemistry who cleared the way for modernity by sweeping away

misguided alchemy. When biographers examined Boyles papers in the 1740s, they

discarded many alchemical materials as worthless. Given the disrepute attached to al-

chemy by that time, it was not something they wanted to have connected to their hero.

Ironically, much of this materialsuch as the work on transmutational processes Boyle

called his Hermetick Legacyhad already been pilfered shortly after his death in 1691,

but then probably on account of its perceived value. The surviving material documents

unambiguously Boyles lifelong chrysopoetic activities, his search for the philosophers

stone, and his attempts to contact adepti.

11

Once again, some authors (but not all)

7

David Brewster, Memoirs of the Life, Writings, and Discoveries of Sir Isaac Newton, 2 vols. (Edinburgh,

1855), Vol. 2, pp. 374375. Note how Sarton parroted Brewsters phrasing in Boyle and Bayle.

8

A Catalogue of the Portsmouth Collection of Books and Papers (Cambridge, 1888), p. xix. On Newtons

papers see Rob Iliffe, A Connected System? The Snare of a Beautiful Hand and the Unity of Newtons

Archive, in Archives of the Scientic Revolution, ed. Michael Hunter (Woodbridge: Boydell, 1998), pp.

137157; and Peter Spargo, Sotheby, Keynes, and Yahuda: The 1936 Sale of Newtons Manuscripts, in The

Investigation of Difcult Things: Essays on Newton and the History of the Exact Sciences, ed. Peter Harman and

Alan Shapiro (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1992), pp. 115134.

9

The tendency is visible in the 1888 Catalogue of the Portsmouth Collection of Books and Papers, p. xix; it

is clear in Marie Boas and A. Rupert Hall, Newtons Chemical Experiments, Archives Internationales

dHistoire des Sciences, 1958, 11:113152.

10

Richard S. Westfall, The Role of Alchemy in Newtons Career, in Reason, Experiment, and Mysticism in

the Scientic Revolution, ed. M. L. Righini Bonelli and William R. Shea (London: Macmillan, 1975), pp.

189232 (see Marie Boas Halls critical response, Newtons Voyage on the Strange Seas of Alchemy, ibid.,

pp. 239246); and Betty Jo Teeter Dobbs, The Foundations of Newtons Alchemy; or, The Hunting of the

Greene Lyon (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 1975).

11

Lawrence M. Principe, The Aspiring Adept: Robert Boyle and His Alchemical Quest (Princeton, N.J.:

Princeton Univ. Press, 1998), esp. pp. 1126. On the fate of the papers see Michael Hunter and Principe, The

Lost Papers of Robert Boyle, Annals of Science, 2003, 60:269311; on Boyles biographies see Hunter, Robert

Boyle: By Himself and His Friends (London: Pickering, 1994).

308 FOCUSISIS, 102 : 2 (2011)

endeavored to ignore or explain away Boyles alchemy, simultaneously elevating his 1661

Sceptical Chymist into an epoch-making book, a death warrant that struck at the

root of alchemy (it wasnt and it didnt).

12

As with Newton, revealing Boyles alchemy

was sometimes met with resistance or even outrageI recall being yelled at during an

international conference in the 1990s for defaming Boyle and more recently have had

my claims about Boyle and alchemy attributed to the use of hallucinatory drugs.

Current scholarship now removes any grounds for surprise (or horror) over the likes of

Boyle or Newton studying alchemy. Further research continues to add to the roster of

well-known gures who seriously pursued chrysopoeia. Now that we recognize alchemy

as part of natural philosophy, we should instead be surprised if early modern thinkers

interested in the constitution and manipulation of matter had not studied or pursued

chrysopoeia. Hand-in-hand with historiographical developments beyond earlier great

men narratives, historians of science are revealing how ubiquitous chymical practice

including chrysopoetic endeavorsreally was. Alchemy extends from well-known gures

to a host of lesser-known characters in and out of academic, medical, courtly, and private

settings and across the whole social and intellectual spectrum of projectors, entrepreneurs,

reners, miners, and others, all the way to brewers, shoemakers, and drapers.

13

Indeed, one

of the most important features of the new historiography of alchemy is the recovery of its

diversity and dynamism.

14

Part of the rhetorical strategy of the eighteenth century, and of

debunkers of alchemy ever since, was to lump all chrysopoeians together, enabling the

criticism (or parody) of a part to be extended to the whole. In 1722, for example, Geoffroy

cited the most celebrated instances of transmutational fraud and allowed them to be

extrapolated to the whole of chrysopoeia. Subsequent writers routinely picked marginal

gures or ideas as representative of the whole or lumped excised snippets from authors

widely separated in time and cultural context together into an undifferentiated pastiche.

Interestingly, authors from opposite ends of the spectrumpositivists and occultists

converged on this point. For the former, alchemy was distinguished from progressive

science by being static, an unchanging body of inherited ideas based on a priori reason-

ings and unresponsive to observations. The latter, encouraged by the notion of continuity

promoted by ancient wisdom narratives prominent in esoteric circles, crafted all-

embracing, transtemporal denitions of alchemy. Both viewpoints have been raised even

recently in objection against the new historiography of alchemy.

15

Certainly, some chryso-

poetic authors facilitated such treatment by rhetorically claiming a unity to the alchemical

12

E. J. Holmyard, Alchemy (Hammondsworth: Penguin, 1957), p. 273.

13

One footnote cannot encompass the outstanding work that displays the breadth of alchemy, but see Bruce

T. Moran, The Alchemical World of the German Court (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1991); Tara E. Nummedal, Alchemy

and Authority in the Holy Roman Empire (Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press, 2007); and Pamela H. Smith, The

Business of Alchemy: Science and Culture in the Holy Roman Empire (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton Univ. Press,

1994).

14

Lawrence M. Principe, Diversity in Alchemy: The Case of Gaston Claveus DuClo, a Scholastic

Mercurialist Chrysopoeian, in Reading the Book of Nature: The Other Side of the Scientic Revolution, ed.

Allen G. Debus and Michael Walton (Kirksville, Mo.: Sixteenth Century Press, 1998), pp. 181200; and

Principe, The Alchemies of Robert Boyle and Isaac Newton: Alternate Approaches and Divergent Deploy-

ments, in Rethinking the Scientic Revolution, ed. Margaret J. Osler (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press,

2000), pp. 201220.

15

E

tienne-Francois Geoffroy, Des supercheries concernant la pierre philosophale, Memoires de lAcademie

Royale des Sciences, 1722, 24:6170. For an example of the continued deployment of such outdated notions see Brian

Vickers, The New Historiography and the Limits of Alchemy, Ann. Sci., 2008, 65:127156; see likewise the

trenchant critique of such notions in William R. Newman, Brian Vickers on Alchemy and the Occult: A Response,

Perspectives on Science, 2009, 17:482506.

F

O

C

U

S

FOCUSISIS, 102 : 2 (2011) 309

quest (all the sages say one thing) and by reinterpreting earlier authors to support their

own ideas, thereby creating a supercial impression of uniformity.

But careful contextual readings of alchemical texts now continue to reveal that alchemy

was never monolithic or static. Early modern European alchemy alone displays a stag-

gering diversity of theories, practices, and purposes: Scholastic and anti-Aristotelian,

Paracelsian and anti-Paracelsian, Hermetic, Neoplatonic, mechanistic, vitalistic, and

moreplus virtually every combination and compromise thereof. Arguments ourished

over the starting material(s) for the philosophers stone, just as diverse theories drawing

on substantial forms, semina, particles, principles (one, two, three, four, or vedepend-

ing on the author), and other concepts abounded to explain its transmutational abilities and

the nature of chymical change. Experimental results and observations fed into both theory

and practice. Notwithstanding the caricature of alchemists single-mindedly seeking the

philosophers stone, legions of hopeful chrysopoeians in fact collected, traded, and

experimented with a myriad of processes for less potent transmuting agents known as

particulars, and most practitioners diversied their activitiesfor practical economic

reasons, if nothing elseto include pharmaceutical and commercial production. Such

diversity renders it impossible to make blanket statements about the content and inuence

of alchemy without careful qualication and guarantees that we will have much to learn

about alchemy for many years to come.

Another key step toward resituating alchemy in the history of science required getting

a handle on what alchemists actually did every day. The enigmatic character of alchemical

texts seemed to defy understanding. Rhetorically motivated parodies from the eighteenth

century or misguided interpretations from the nineteenth and twentieth lled the resultant

vacuum, providing a consensus that, whatever alchemists did, it was neither chemistry nor

scientic and in some cases was not even related to the material world. Of course, many

scholars did enumerate specic contributions from alchemy, often by identifying the

earliest appearance of some substance or technique.

16

Such endeavors were valuable but

could do little to rehabilitate alchemy as part of the history of science, both because these

isolated rsts t easily with the notion that alchemists stumbled on things more or less

by accident and because the extraction of such positive nuggets left the bulk and fabric of

alchemical writings, theories, and practices, especially chrysopoetic ones, unexplained.

Thus it was necessary to show that apparently incomprehensible, seemingly fanciful, or

metaphorically expressed texts actually rested on practical chemical foundations. The

desire to know what alchemists actually did in practice led meinitially back in the early

1980sto try to replicate their results, to see what they saw (and often enough smell what

they smelled, although I continue to draw the line at tasting what they tasted). Eventually,

many processes that seemed implausible were found to work once impurities present in

early modern starting materials were taken into account. Boyles transmutation of gold

into silver worked exactly as he described, even if his silver turned out to be silvery

antimony. Even some of the most bizarre alchemical imagery supposedly hiding routes

toward the philosophers stone, once decoded, yielded surprising and workable processes

that must have required astonishingly well-developed experimental techniques.

17

Interest-

16

E.g., John Maxson Stillman, The Story of Early Chemistry (New York: Appleton, 1924), rpt. as The Story

of Alchemy and Early Chemistry (New York: Dover, 1960); and J. R. Partington, A History of Chemistry, 4 vols.

(London: Macmilllan, 19611970).

17

Lawrence M. Principe, Chemical Translation and the Role of Impurities in Alchemy: Examples from Basil

Valentines Triumph-Wagen, Ambix, 1987, 34:2130; Principe, The Gold Process: Directions in the Study of

Robert Boyles Alchemy, in Alchemy Revisited, ed. Z. R. W. M. van Martels (Leiden: Brill, 1990), pp.

310 FOCUSISIS, 102 : 2 (2011)

ingly, just as the revelation of Boyles and Newtons alchemical endeavors did not always

nd a warm welcome, neither did these results or the very technique of replicating

experimentsby either die-hard alchemical skeptics or exponents of the then-prominent

sociological schools. It is particularly encouraging, therefore, to witness the recent interest

in historical replications, not just in alchemy but across the history of science, as a tool for

increasing our historical understanding. Together with fresh understanding of the theo-

retical systems chrysopoeians developed, and the clear-minded interplay between theory

and practice, these new ndings proved that alchemists could not be written off as

fabricators of imagined processes, mere empirics, or frauds.

While prevailing attitudes toward alchemy (formerly among historians, and still today

among much of the general public) required that pioneers in the eld emphasize how

alchemy was truly part of the history of sciencein short, opposing the routine label of

pseudoscienceit would obviously create an unsatisfactory view of alchemys richness,

character, and context to reduce it to some sort of protochemistry. But I know of no

modern scholar who maintains that alchemy is part of science in the modern sense. The

point is that it was fully part of contemporaneous natural philosophy. This important

distinction can be too easily obscured by an automatic usage nowadays of natural

philosophy as a historiographically correct substitute term for science without

adequate reection on the difference of meaning. Over half a century ago, Walter Pagel,

defending the study of topics that positivistic historians of the day saw as rubbish,

emphasized that early modern thinkers pursued Philosophia Naturalis, dened suc-

cinctly as nature in her entirety, cosmology in its widest sensethat is a mixture of

Science, Theology, and Metaphysics.

18

In the eyes of earlier generations, the theological,

religious, and metaphysical content of alchemical texts disqualied them from being part

of the scientic tradition, even while those same eyes overlooked similar features in

early modern physics, astronomy, or natural historyindeed, in all of early modern

science. Alchemical textslike other contemporaneous natural philosophical textsare

implicitly structured on the vision of a tightly interconnected cosmos of God, man, and

nature that is full of meaning, purpose, and symbol. In this context chymical transforma-

tions frequently and easily carried linkages for their authors with ideas in theology,

literature, mythology, and other elds that since the eighteenth century have been con-

sidered extraneous. The shift away from such comprehensive perspectives is clear in

Boerhaaves oration, for example; as a pedagogical reformer and Calvinist biblical

literalist, he was horried by the metaphorical use of Scripture to support specic

laboratory processes and by the linkage of chymical ideas to Christian doctrines. The key

rolesometimes explicit, always implicitof theology and metaphysics in alchemy does

not disqualify it as part of the history of science any more than these same features in, for

example, Kepler or Newton would disqualify their work.

Indeed, the rehabilitation of alchemy helps broaden our understanding of what is meant

by science, its development, and its evolving place in society. Alchemys exile resulted

200205; and Principe, Apparatus and Reproducibility in Alchemy, in Instruments and Experimentation in the

History of Chemistry, ed. Frederic L. Holmes and Trevor Levere (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2000), pp.

5574. Detailed descriptions of decoding and replicating transmutational and other chymical processes appear

in my forthcoming The Secrets of Alchemy (Chicago: Univ. Chicago Press, in press).

18

Walter Pagel, The Vindication of Rubbish, originally published in the Middlesex Hospital Journal (1945),

rpt. in Religion and Neoplatonism in Renaissance Medicine (London: Variorum, 1985), pp. 114, on p. 11; see

the similar denition of natural philosophy as a topic in which physics, metaphysics, and theology could meet

and negotiate their claims in Dennis Des Chene, Physiologia: Natural Philosophy in Late Aristotelian and

Cartesian Thought (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell Univ. Press, 1996), p. 3.

F

O

C

U

S

FOCUSISIS, 102 : 2 (2011) 311

from a conscious redrawing of the boundaries of science, and the modern resistance to

assertions of alchemys importance came from proponents of a narrow view of what

counted as science. This view was shaped by eighteenth-century rhetoric and enhanced by

nineteenth- and early twentieth-century positivism, progressivism, and a priori or norma-

tive philosophical or political formulations about science. Alchemy represented the

other, a convenient foil against which chemistry or science in general could be set off.

Alchemys estrangement exemplies how science does not always develop by means of

cold reason or demonstrable experiment. Transmutational alchemy, vilied by declama-

tion rather than disproved by demonstration, was ostracized for the sake of professional

expedience at a time in which there was no way to know that its goals were physically

unobtainable. Chemists of the day had the problem of their social status and reputation to

solve, and the public sacrice of transmutational alchemy was the way they chose to solve

itcleansing their eld and dening themselves as reputable by marking out a disrep-

utable other. An analogous dynamic explains the antagonism of some twentieth-century

historians and scientists toward claims for alchemys importance and its connection to

major gures. They were invested in a particular foundation myth of science. To maintain

it, they needed alchemy to be something other, something in opposition to which

modern, rational, experimental science could dene itself and upon which they could in

turn dene themselves. Hence the intensely personal nature of some of their attacks. There

was no place for alchemy in accounts of the canonized heroes of modern science. A

similar incredulity or dismissal (and often by the same individuals) sometimes greeted the

fact that religion was a crucial motivating force behind the Scientic Revolution and that

our heroes from the period were almost invariably committed Christians.

19

Over the past

fty years, insistence on the importance of alchemy (and theology) has broadened our

disciplines vision and enhanced our understanding of the ever-evolving thing we call

science.

Alchemys exclusion illustrates strategic redenitions of science, while its rehabilitation

points to the contextual nature of those denitions. One gift offered by the history of

science is the recognition that science is a far messier process than simple models, wishful

thinking, or programmatic philosophies will allow. It collects elements from unexpected

sources and synthesizes them in unexpected and unpredictable ways. It is never a

mechanical or impersonal processnor would we want it to be. While the laws of nature

exist independently of us, the ways we choose to conceive of them, to explore or not to

explore them, to describe or not to describe themthat is to say, scienceis a very human

affair, lled with all the complexities and simplicities, errors and insights, pettiness and

nobility that customarily attend human activity. And, to be sure, alchemy forms an

important part of that story.

19

For the case of religion see Margaret J. Osler, Religion and the Changing Historiography of the Scientic

Revolution, in Science and Religion: New Historical Perspectives, ed. Thomas Dixon, Geoffrey Cantor, and

Stephen Pumfrey (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2010), pp. 7186.

312 FOCUSISIS, 102 : 2 (2011)

You might also like

- Colilli, Paul - The Angels CorpseDocument200 pagesColilli, Paul - The Angels Corpsemathew bilkersonNo ratings yet

- Debus, English ParacelsiansDocument118 pagesDebus, English ParacelsiansPrabhasvara100% (3)

- Alchemy and Rudolf II PDFDocument14 pagesAlchemy and Rudolf II PDFcodytlseNo ratings yet

- Girolamo Cardano - The de Subtilitate of Girolamo Cardano 1 (2013, Arizona Center For Medieval and Renaissance Studies)Document548 pagesGirolamo Cardano - The de Subtilitate of Girolamo Cardano 1 (2013, Arizona Center For Medieval and Renaissance Studies)angelica ferroniNo ratings yet

- Charles G Nauert - 1955 - Agrippa Von Netteshiem (1486-1585) His Life and ThoughtDocument273 pagesCharles G Nauert - 1955 - Agrippa Von Netteshiem (1486-1585) His Life and ThoughtBryan PitkinNo ratings yet

- 2389 Nietszsche Julian Young Bulend O.doghan 2010 983sDocument983 pages2389 Nietszsche Julian Young Bulend O.doghan 2010 983sYılgı OkayNo ratings yet

- Karpenko - Viridarium Chyrnicum PDFDocument3 pagesKarpenko - Viridarium Chyrnicum PDFJames L. KelleyNo ratings yet

- Rafał Prinke, Heliocantharus BorealisDocument38 pagesRafał Prinke, Heliocantharus Borealisbalthasar777100% (1)

- Yeats and OccultDocument13 pagesYeats and Occultsana fatimaNo ratings yet

- Splendor Solis Explaination PDFDocument1 pageSplendor Solis Explaination PDFlinecurNo ratings yet

- Mass Society TheoryDocument2 pagesMass Society TheoryAarthi Padmanabhan67% (6)

- Debus, Allen G. - The Chemical PromiseDocument26 pagesDebus, Allen G. - The Chemical PromiseAngela Maria Jiurgiu100% (2)

- Alchemy and Alchemical Knowledge in Seventeenth-Century New EnglandDocument97 pagesAlchemy and Alchemical Knowledge in Seventeenth-Century New Englandmullen65No ratings yet

- Joannes Baptista Van Helmont 1000003485Document92 pagesJoannes Baptista Van Helmont 1000003485Ivan Portnoy MatijanicNo ratings yet

- Alchemical Theories of MatterDocument7 pagesAlchemical Theories of MatterEric_CrowNo ratings yet

- DEBUS, A. G. Chemists, Physicians, and Changing Perspectives On The Scientific RevolutionDocument16 pagesDEBUS, A. G. Chemists, Physicians, and Changing Perspectives On The Scientific RevolutionRoger CodatirumNo ratings yet

- Newman - Medieval AlchemyDocument19 pagesNewman - Medieval AlchemyTatum100% (1)

- Greek Alchemy From Late Antiquity To Early ModernityDocument200 pagesGreek Alchemy From Late Antiquity To Early ModernityMarthaNo ratings yet

- Antonie FaivreDocument20 pagesAntonie FaivreDrakma AmkardNo ratings yet

- The Aspiring Adept Robert Boyle by Lawrence M. PrincipeDocument179 pagesThe Aspiring Adept Robert Boyle by Lawrence M. PrincipeSolGriffinNo ratings yet

- The Alchemical Corpus Attributed To Raymond Lull Michela PereiraDocument2 pagesThe Alchemical Corpus Attributed To Raymond Lull Michela PereiraB GNo ratings yet

- Ambix 1 - Issue 1.4Document13 pagesAmbix 1 - Issue 1.4Diogo CalazansNo ratings yet

- Heinrich Khunrath and His Theosophical R PDFDocument22 pagesHeinrich Khunrath and His Theosophical R PDFgtnlmnc99235No ratings yet

- The Golden Calf, Which the World Adores, and DesiresFrom EverandThe Golden Calf, Which the World Adores, and DesiresNo ratings yet

- Dispersa Intentio." Alchemy, Magic andDocument19 pagesDispersa Intentio." Alchemy, Magic andMatheusGrohsNo ratings yet

- Prophecy and Alchemy by William NewmanDocument22 pagesProphecy and Alchemy by William NewmanAlexander Robert Jenner100% (2)

- Renaissance Esotericism Alchemy BetweenDocument8 pagesRenaissance Esotericism Alchemy BetweenMarion Meyer Rare BooksNo ratings yet

- Alchemy and Exemplary Poetry in Middle English PoetryDocument211 pagesAlchemy and Exemplary Poetry in Middle English PoetryVopym78No ratings yet

- The Urim and Thummim and The Origins of The Gold Und Rosenkreuz by Dr. Hereward Tilton - Rosicrucian Tradition WebsiteDocument42 pagesThe Urim and Thummim and The Origins of The Gold Und Rosenkreuz by Dr. Hereward Tilton - Rosicrucian Tradition WebsitenickgamasNo ratings yet

- Development of Concept of MindDocument14 pagesDevelopment of Concept of MindLeidy Paola Gamboa GamboaNo ratings yet

- New Platonism and AlchemyDocument26 pagesNew Platonism and AlchemyShagrat All Durr100% (1)

- VICKERS, Brian. The New Historiography and The Limits of Alchemy PDFDocument31 pagesVICKERS, Brian. The New Historiography and The Limits of Alchemy PDFClara LimaNo ratings yet

- The Apocalyptic Eucharist and Religious Dissidence in Stefan Michelspacher's Cabala - Spiegel Der Kunst Und Natur, in Alchymia (1616) PDFDocument25 pagesThe Apocalyptic Eucharist and Religious Dissidence in Stefan Michelspacher's Cabala - Spiegel Der Kunst Und Natur, in Alchymia (1616) PDFVanni100% (1)

- Hereward Tilton - of Electrum and The Armour of AchillesDocument41 pagesHereward Tilton - of Electrum and The Armour of AchillesLibaviusNo ratings yet

- The Philosopher's Stone: Gold Production and the Search for Eternal LifeFrom EverandThe Philosopher's Stone: Gold Production and the Search for Eternal LifeNo ratings yet

- Mapa Astral BachelardDocument19 pagesMapa Astral BachelardGabriel Kafure da RochaNo ratings yet

- Greek Alchemists at Work Alchemical Labo PDFDocument41 pagesGreek Alchemists at Work Alchemical Labo PDFshoulaNo ratings yet

- Calian - Alkimia OperativaDocument29 pagesCalian - Alkimia Operativanahoma68100% (2)

- Two Occult Philosophers in The Elizabethan Age: by Peter ForshawDocument10 pagesTwo Occult Philosophers in The Elizabethan Age: by Peter ForshawFrancesco VinciguerraNo ratings yet

- Stephan Michelspacher in DIVINE WISDOM PDFDocument14 pagesStephan Michelspacher in DIVINE WISDOM PDFNishant ThakkarNo ratings yet

- Zosimos of Panopolis and The Book of Eno PDFDocument23 pagesZosimos of Panopolis and The Book of Eno PDFBrain ShortNo ratings yet

- Issues On Greek AlchemyDocument212 pagesIssues On Greek AlchemyMarthaNo ratings yet

- An Experimental Comparison of The East Asian Hellenistic and Indian Gandh Ran Stills in Relation To The Distillation of Ethanol and Acetic AcidDocument9 pagesAn Experimental Comparison of The East Asian Hellenistic and Indian Gandh Ran Stills in Relation To The Distillation of Ethanol and Acetic AcidshoulaNo ratings yet

- The Alchemical Patronage of Sir William Cecil, Lord BurghleyDocument180 pagesThe Alchemical Patronage of Sir William Cecil, Lord BurghleyJames CampbellNo ratings yet

- A - Aries Book SeriesDocument2 pagesA - Aries Book SeriespilgrimNo ratings yet

- Forays Into Alchemical Pottery-India-1ADocument15 pagesForays Into Alchemical Pottery-India-1AgourdgardenerNo ratings yet

- Pagel - The Paracelsian Elias Artista and The Alchemical TraditionDocument15 pagesPagel - The Paracelsian Elias Artista and The Alchemical TraditionsinderesiNo ratings yet

- 26 2 Schuchard PDFDocument13 pages26 2 Schuchard PDFMauro De FrancoNo ratings yet

- Rene Zandbergen & Rafał T. Prinke, The Voynich MS in Rudolfine PragueDocument108 pagesRene Zandbergen & Rafał T. Prinke, The Voynich MS in Rudolfine Praguebalthasar777No ratings yet

- Plessner The Turba PhilosophorumDocument9 pagesPlessner The Turba PhilosophorumAcca Erma SettemontiNo ratings yet

- Forshaw, 'Alchemy in The Amphitheatre'Document26 pagesForshaw, 'Alchemy in The Amphitheatre'nemoomenNo ratings yet

- The Paracelsian Compromise in Elizabethan EnglandDocument29 pagesThe Paracelsian Compromise in Elizabethan Englandsalah64No ratings yet

- Hermeticism and Alchemy. The Case of Ludovico Lazzarelli PDFDocument16 pagesHermeticism and Alchemy. The Case of Ludovico Lazzarelli PDFMau OviedoNo ratings yet

- Alchemy of Prague Event - 2018Document2 pagesAlchemy of Prague Event - 2018Dennis Montoya ValverdeNo ratings yet

- Sal Ammoniac-A Case History in Industrialization-Robert P. MulthaufDocument24 pagesSal Ammoniac-A Case History in Industrialization-Robert P. MulthaufLuis Vizcaíno100% (1)

- Mercurius SolisDocument18 pagesMercurius SolisAnonymous 77zvHWsNo ratings yet

- Newton ChymistryDocument35 pagesNewton ChymistryJoel KleinNo ratings yet

- Schuchard2011 PDFDocument824 pagesSchuchard2011 PDFManticora Venerabilis100% (1)

- Quispel-Hermes Trismegistus and The Origins of GnosticismDocument20 pagesQuispel-Hermes Trismegistus and The Origins of GnosticismStavros GirgenisNo ratings yet

- The Philosophers Stone - Alchemical Imagination and The Souls LoDocument330 pagesThe Philosophers Stone - Alchemical Imagination and The Souls LoCristian CiobanuNo ratings yet

- The Aspiring Adept: Robert Boyle and His Alchemical QuestFrom EverandThe Aspiring Adept: Robert Boyle and His Alchemical QuestRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Whig HistoryDocument7 pagesWhig HistoryFelipe100% (1)

- Descartes and The Ontology of Subjectivity - B.C. FlynnDocument21 pagesDescartes and The Ontology of Subjectivity - B.C. FlynnFelipeNo ratings yet

- Descartes and Skepticism - M. GreneDocument19 pagesDescartes and Skepticism - M. GreneFelipeNo ratings yet

- Descartes's Ontology - V. ChappellDocument17 pagesDescartes's Ontology - V. ChappellFelipeNo ratings yet

- The Fourth Meditation - Lex NewmanDocument33 pagesThe Fourth Meditation - Lex NewmanFelipe100% (1)

- Cartesian Mechanics - Sophie RouxDocument46 pagesCartesian Mechanics - Sophie RouxFelipeNo ratings yet

- Are There Genuine Mathematical Explanations of Physical Phenomena - Alan BakerDocument17 pagesAre There Genuine Mathematical Explanations of Physical Phenomena - Alan BakerFelipe100% (1)

- Factors Affecting The Academic Performance (Solving Mathematical Problems) of Grade 9 StudentsDocument8 pagesFactors Affecting The Academic Performance (Solving Mathematical Problems) of Grade 9 StudentsCheris GacutanoNo ratings yet

- Balibar Spinoza and PoliticsDocument82 pagesBalibar Spinoza and Politicsedifying100% (4)

- Games and Violence EssayDocument6 pagesGames and Violence EssayFitri Aulia PermatasariNo ratings yet

- Looking Into PicturesDocument436 pagesLooking Into PicturesMarina Ersoy100% (1)

- Educ 128 Module Adapted From Project WRITE SekhfgDocument55 pagesEduc 128 Module Adapted From Project WRITE SekhfgJane Leizl Lozano67% (3)

- BuddhismDocument34 pagesBuddhismKelvin Paul Bamba Panuncio100% (1)

- LECTURE 09 Being An Effective LeaderDocument27 pagesLECTURE 09 Being An Effective LeaderRaahim NajmiNo ratings yet

- Jacob Boehme: Mysterium Magnum, Part One - Free Electronic TextDocument375 pagesJacob Boehme: Mysterium Magnum, Part One - Free Electronic TextMartin Euser100% (10)

- Hypothesis DevelopmentDocument20 pagesHypothesis DevelopmentUmair GurmaniNo ratings yet

- Erin Manning - Politics of Touch - Chapter 5Document25 pagesErin Manning - Politics of Touch - Chapter 5Taylor ApplegateNo ratings yet

- PHI 1010 Course Outline SDocument3 pagesPHI 1010 Course Outline SJoshua BupeNo ratings yet

- Noesis - Chris Langan CommentsDocument124 pagesNoesis - Chris Langan Commentsisotelesis100% (1)

- Economy of Truth by Vizi Andrei SampleDocument32 pagesEconomy of Truth by Vizi Andrei SampleMari Freire100% (1)

- Reference (I) Poem: A Constable Calls (Ii) Poet: Seamus Heaney ContextDocument2 pagesReference (I) Poem: A Constable Calls (Ii) Poet: Seamus Heaney ContextAisha Khan100% (1)

- Assignment PDFDocument2 pagesAssignment PDFHarrison RumeNo ratings yet

- Truth and Self in IqbalDocument7 pagesTruth and Self in IqbalSafha thanviNo ratings yet

- Arete - Excellence, Strength, VirtueDocument7 pagesArete - Excellence, Strength, Virtueenidualc zechnasNo ratings yet

- Quiz-Assignment For Understanding The SelfDocument2 pagesQuiz-Assignment For Understanding The SelfAsuna YuukiNo ratings yet

- Ethics of Scientific Research PDFDocument2 pagesEthics of Scientific Research PDFMaria0% (1)

- Confucianism: The AnalectsDocument1 pageConfucianism: The Analectslomboy elemschoolNo ratings yet

- Capitalism Vs Communism EssayDocument3 pagesCapitalism Vs Communism Essayhtzmxoaeg100% (2)

- Lotsawa Kaba Paltseng - A Manual of Key Buddhist Terms PDFDocument127 pagesLotsawa Kaba Paltseng - A Manual of Key Buddhist Terms PDFwu-wey0% (1)

- Discretionary TraditionDocument11 pagesDiscretionary TraditiondersideriousNo ratings yet

- 52 Codes For Conscious Self EvolutionDocument35 pages52 Codes For Conscious Self EvolutionSorina LutasNo ratings yet

- Craft of ResearchDocument7 pagesCraft of Researchcckan100% (2)

- ZarathustraDocument531 pagesZarathustraAnonymous DsugoSBa100% (1)

- Science 7 Module (Lesson 1)Document5 pagesScience 7 Module (Lesson 1)Ron Marrionne AbulanNo ratings yet

- Science and EthicsDocument4 pagesScience and EthicsFco VsNo ratings yet