ADHD Medications and Risk of Serious Cardiovascular Events in Young and Middle-Aged Adults

ADHD Medications and Risk of Serious Cardiovascular Events in Young and Middle-Aged Adults

Uploaded by

Gary KatzCopyright:

Available Formats

ADHD Medications and Risk of Serious Cardiovascular Events in Young and Middle-Aged Adults

ADHD Medications and Risk of Serious Cardiovascular Events in Young and Middle-Aged Adults

Uploaded by

Gary KatzOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

ADHD Medications and Risk of Serious Cardiovascular Events in Young and Middle-Aged Adults

ADHD Medications and Risk of Serious Cardiovascular Events in Young and Middle-Aged Adults

Uploaded by

Gary KatzCopyright:

Available Formats

ORIGINAL CONTRIBUTION

ONLINE FIRST

ADHD Medications and Risk

of Serious Cardiovascular Events

in Young and Middle-aged Adults

Laurel A. Habel, PhD

William O. Cooper, MD, MPH

Colin M. Sox, MD, MS

K. Arnold Chan, MD, ScD

Bruce H. Fireman, MA

Patrick G. Arbogast, PhD

T. Craig Cheetham, PharmD, MS

Virginia P. Quinn, PhD, MPH

Sascha Dublin, MD, PhD

Denise M. Boudreau, PhD, RPh

Susan E. Andrade, ScD

Pamala A. Pawloski, PharmD

Marsha A. Raebel, PharmD

David H. Smith, RPh, PhD

Ninah Achacoso, MS

Connie Uratsu, RN

Alan S. Go, MD

Steve Sidney, MD, MPH

Mai N. Nguyen-Huynh, MD, MAS

Wayne A. Ray, PhD

Joe V. Selby, MD, MPH

B

ETWEEN 2001 AND 2010, USE

of medications labeled for

treatment of attention-deficit/

hyperactivitydisorder (ADHD)

increased even more rapidly in adults

than in children.

1

According to a 2006

US Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) advisory committee briefing on

the safety of ADHDmedications, more

than 1.5 million US adults were taking

stimulants in2005, andadults received

approximately32%of all issuedprescrip-

tions.

2

The increase in ADHD diagno-

sesislikelytheprimarycauseof increased

prescribing,

3,4

althoughstimulants also

See related article.

Author Affiliations: Division of Research, Kaiser Perma-

nente Northern California, Oakland (Drs Habel, Go,

Sidney, Nguyen-Huynh, and Selby, Mr Fireman, and

Mss Achacoso and Uratsu); Department of Pediatrics

(Dr Cooper), Division of Pharmacoepidemiology, De-

partment of Preventive Medicine (Drs Cooper andRay),

and Department of Biostatistics (Dr Arbogast), Van-

derbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee; Harvard Pil-

grim Health Care Institute, Department of Popula-

tion Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston,

Massachusetts, and Department of Pediatrics, Bos-

ton University School of Medicine, Boston (Dr Sox);

OptumInsight Epidemiology, Waltham, Massachu-

setts (Dr Chan); Pharmacy Analytical Service, Kaiser

Permanente Southern Cal i forni a, Downy (Dr

Cheetham); Research and Evaluation Department, Kai-

ser Permanente Southern California, Pasadena (Drs

CheethamandQuinn); GroupHealthResearchInstitute,

Seattle, Washington(Drs DublinandBoudreau); Depart-

ments of Epidemiology (Dr Dublin) and Pharmacy (Dr

Boudreau), University of Washington, Seattle; Meyers

Primary Care Institute, Worcester, Massachusetts (Dr

Andrade); HealthPartners ResearchFoundation, Bloom-

ington, Minnesota (Dr Pawloski); Institute for Health

Research, Kaiser Permanente Colorado, and School of

Pharmacy, Universityof Coloradoat Denver (Dr Raebel);

Center for Health Research, Kaiser Permanente North-

west, Portland, Oregon(Dr Smith); andDepartments of

Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Medicine, University of

California, San Francisco (Dr Sidney).

Corresponding Author: Laurel A. Habel, PhD, Divi-

sion of Research, Kaiser Permanente Northern Cali-

fornia, 2000Broadway, FifthFloor, Oakland, CA94612

(laurel.habel@kp.org).

Context More than 1.5 million US adults use stimulants and other medications labeled

for treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). These agents can in-

crease heart rate and blood pressure, raising concerns about their cardiovascular safety.

Objective To examine whether current use of medications prescribed primarily to

treat ADHD is associated with increased risk of serious cardiovascular events in young

and middle-aged adults.

Design, Setting, and Participants Retrospective, population-based cohort study

using electronic health care records from 4 study sites (OptumInsight Epidemiology,

Tennessee Medicaid, Kaiser Permanente California, and the HMO Research Net-

work), starting in 1986 at 1 site and ending in 2005 at all sites, with additional covar-

iate assessment using 2007 survey data. Participants were adults aged 25 through 64

years with dispensed prescriptions for methylphenidate, amphetamine, or atomox-

etine at baseline. Each medication user (n=150 359) was matched to 2 nonusers on

study site, birth year, sex, and calendar year (443 198 total users and nonusers).

Main Outcome Measures Serious cardiovascular events, including myocardial in-

farction (MI), sudden cardiac death (SCD), or stroke, with comparison between cur-

rent or new users and remote users to account for potential healthy-user bias.

Results During806182person-years of follow-up(median, 1.3years per person), 1357

cases of MI, 296 cases of SCD, and 575 cases of stroke occurred. There were 107322

person-years of current use (median, 0.33 years), with a crude incidence per 1000 person-

years of 1.34 (95% CI, 1.14-1.57) for MI, 0.30 (95% CI, 0.20-0.42) for SCD, and 0.56

(95%CI, 0.43-0.72) for stroke. The multivariable-adjusted rate ratio (RR) of serious car-

diovascular events for current use vs nonuse of ADHD medications was 0.83 (95% CI,

0.72-0.96). Among new users of ADHD medications, the adjusted RR was 0.77 (95%

CI, 0.63-0.94). The adjusted RR for current use vs remote use was 1.03 (95% CI, 0.86-

1.24); for new use vs remote use, the adjusted RR was 1.02 (95% CI, 0.82-1.28); the

upper limit of 1.28 corresponds to an additional 0.19 events per 1000 person-years at

ages 25-44 years and 0.77 events per 1000 person-years at ages 45-64 years.

Conclusions Among young and middle-aged adults, current or new use of ADHD

medications, compared with nonuse or remote use, was not associated with an in-

creased risk of serious cardiovascular events. Apparent protective associations likely

represent healthy-user bias.

JAMA. 2011;306(24):doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1830 www.jama.com

2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. JAMA, Published online December 12, 2011 E1

by guest on December 14, 2011 jama.ama-assn.org Downloaded from

areapprovedfortreatment of narcolepsy

5

and may be used off-label to treat obe-

sity

6

andfatigue relatedto depression,

7

stroke,

8

ortraumaticbraininjury.

9

Adults

withADHDare commonlytreatedwith

the stimulant classes methylphenidate

andamphetamineandincreasinglywith

a nonstimulant agent, atomoxetine.

Placebo-controlled studies in chil-

dren and adults indicate that stimu-

lants and atomoxetine elevate systolic

blood pressure levels by approximately

2 to 5 mm Hg and diastolic blood pres-

sure levels by 1to3mmHg andalsolead

to increases in heart rate.

10,11

Although

theseeffects wouldbeexpectedtoslightly

increase risk for myocardial infarction

(MI), sudden cardiac death (SCD), and

stroke,

12

clinical trials have not beenlarge

enough to assess risk of these events.

In a summary fromthe FDAAdverse

Event Reporting System, cardiac arrest,

MI, andsuddenunexplaineddeathwere

among the top 50 adverse events re-

ported after use of amphetamines and

methylphenidate.

2

Although 1 study

among children suggested markedly el-

evated risks of SCD,

13

cardiovascular

safety data from pharmacoepidemio-

logic studies are limited and inconsis-

tent,

13-16

especially among adults.

17,18

The aimof this study was to examine

whether current use of medications used

primarily to treat ADHD is associated

withincreasedriskof MI, SCD, or stroke

inadults aged25through64years. Study

drugs included all agents with a labeled

indication for treatment of ADHD in

either children or adults as of Decem-

ber 31, 2005.

METHODS

The study was conducted in parallel

with a study of ADHDdrug use and se-

rious cardiovascular events in youths

aged 2 through 24 years.

19

Data Sites

Study sites included Vanderbilt Uni-

versity (Tennessee State Medicaiddata),

Kaiser Permanente (KP) California

(northern and southern KP regions),

OptumInsight Epidemiology (data from

a large health insurance plan), and the

HMO Research Network (Harvard

Pilgrim Health Care; Fallon Commu-

nity Health Plan; Group Health Coop-

erative of Puget Sound; HealthPart-

ners; KP Georgia; KP Northwest; and

KP Colorado). The selected sites pro-

vide geographic and sociodemo-

graphic diversity and have similar com-

puterized data structures.

Thestartdatefortheavailabilityofcom-

puterizeddatadifferedacrossstudysites,

ranging from 1986 to 2002. Follow-up

concludedat theendof 2005sothat mor-

talitysearches couldbeconductedusing

completestatedeathrecords andtheNa-

tional Death Index. The study was ap-

provedbytheinstitutional reviewboards

of eachparticipatinginstitutionandbythe

FDAResearchinHumanSubjects Com-

mittee. The requirement for participant

informed consent was waived.

Study Participants

Eligibleindividuals wereaged25through

64 years with at least 12 months of con-

tinuous health plan coverage and phar-

macy benefits before cohort entry (time

zero). Individuals were excluded if they

had 1 or more of the following diagno-

ses (based on International Classifica-

tion of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]

or International Classification of Dis-

eases, Tenth Revision [ICD-10] codes)

within 365 days before cohort entry:

sickle cell disease, cancer (other than

nonmelanoma skincancer), humanim-

munodeficiency virus infection, organ

transplant, liver failure/hepatic coma,

end-stage renal disease, respiratory fail-

ure, or congestive heart failure. When

these diagnoses occurredafter cohort en-

try, follow-up time was censored.

Ateachcontributingsite, weassembled

the eligible members and periods when

all eligibility criteria were met. For each

exposedperiod(ie, at least 1ADHDpre-

scription), starting with the earliest, we

randomly selected2 unexposedperiods

fromall members withno ADHDmedi-

cation use at cohort entry and the same

sex and birth year.

Study Medications

and Exposure Categories

Medication use was based on prescrip-

tion fills from electronic pharmacy rec-

ords. ADHD medications included

stimulant-class medications (methyl-

phenidate, amphetamines, pemoline)

andatomoxetine, a selective norepineph-

rine reuptake inhibitor. Amphetamines

included dextroamphetamines and am-

phetamine salts. Although infrequently

used and not structurally similar to the

other stimulants, pemoline was in-

cluded because of its labeled indication

for ADHD. Each person-day of fol-

low-up was classified into mutually ex-

clusive exposure categories according to

ADHD drug use, based on prescription

dispensing dates and days supply.

Current use was defined as the pe-

riodbetweenprescriptionstart date and

end of days supply (including up to a

7-day carryover fromprevious prescrip-

tions). Indeterminate use was the first 89

days after end of current use. Former

use began at 90 days after end of cur-

rent use and ended at 364 days after last

current use. Greater than364days since

end of last days supply was consid-

ered remote use. Nonuse referred to per-

son-days with no current use and no

past use (back to 365 days before co-

hort entry). Past users and nonusers

could become current users during fol-

low-up; when this occurred, their per-

son-time was classified as described

above. Less than 1% of nonusers be-

came users after baseline. Current use

was further categorized based on spe-

cific medications (amphetamines,

methylphenidate, atomoxetine, mul-

tiple ADHDdrugs, or pemoline) and on

prespecified duration categories (1-30

days, 31-90 days, 91-182 days, 183-

365 days, 366 days).

We consider current use the most

etiologically relevant exposure. Risk

during current use was compared with

risk during nonuse. In addition, to ac-

count for potential selection bias or un-

measured confounding that could arise

from users being more or less healthy

than nonusers, we restricted some

analyses to ever users of ADHD medi-

cations. These analyses compared rates

during periods of current use with rates

during periods 365 days or more after

use ended(ie, remote use). These analy-

ses are less influenced by potential con-

ADHD MEDICATIONS AND CV EVENTS IN YOUNGER ADULTS

E2 JAMA, Published online December 12, 2011 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

by guest on December 14, 2011 jama.ama-assn.org Downloaded from

founders that are unmeasured and

stable over time, but analyses assume

no medication effects that remain af-

ter discontinuation.

Study End Points

Potential end points were identified

fromclaims and vital records (diagno-

ses and ICD codes provided in eTable

1, available at http://www.jama.com).

For members with death not identi-

fied from these sources and whose

health plan enrollment ended prior to

end of study period, we performed Na-

tional Death Index searches.

Medical records, including hospital-

izations, reports fromemergency medi-

cal services, autopsies, and death cer-

tificates, were requested for all potential

SCDs (n=411) andstrokes (n=980) and

for a random 31% sample of potential

MIs (n=433) for assessment by trained

adjudicators (primarycare physicians for

MI and SCD, neurologists for stroke).

Of the 371 MI cases with sufficient

records available, 353 (95%) were con-

firmed by adjudication. Myocardial in-

farction was defined as an acute event

involving hospitalization with charac-

teristic changes in cardiac enzyme lev-

els and either symptoms or character-

istic electrocardiographic changes.

20,21

Sudden cardiac death was definedas wit-

nessed sudden death in a community

setting, preceded by typical symp-

toms of cardiac ischemia. Deaths were

excluded when documentation sug-

gested a noncardiac cause (eg, motor

vehicle crash) or if clinically severe

heart disease was present and sudden

cardiac death was not unexpected (eg,

end-stage congestive heart failure).

Stroke was defined as an acute neuro-

logic deficit of sudden onset that per-

sisted more than 24 hours, corre-

sponded to a vascular territory, and was

not explained by other causes such as

trauma, infection, vasculitis, extracra-

nial hemorrhage leading to hypoten-

sion, or profoundhypotensionfroman-

other cause. Strokes that occurred

during a hospitalizationwere excluded.

All MIs, other than those deter-

mined by adjudication to be noncases

(n=18), were included in analyses. For

potential SCD cases without available

or adequate hospital or autopsy rec-

ords (n=203), we used an ICD-9/

ICD-10 codebased definition with a

previously reported positive predic-

tive value of 86%.

22

SCDcases based on

the code-based definition (n=157), as

well as those confirmed by clinical ad-

judication (n=139), were included in

primary analyses. For potential strokes

with insufficient hospital or autopsy

records for clinical adjudication

(n=179) or for which records were un-

available (n=69), we used a code-

based definition to identify probable

strokes. Probable strokes had ICD-9/

ICD-10 codes with a positive predic-

tive value of 80% or greater, based on

those strokes for which records were

available. Strokes confirmed by adju-

dication (n=451) and those with in-

sufficient records meeting the diagnos-

tic codebaseddefinition(n=124) were

included as events in primary analy-

ses (eTable 2A and B). In secondary

analyses, we included all electroni-

cally identified SCDs or strokes ex-

cept those confirmed as nonevents by

adjudication.

Confounders

To control for potential differences in

cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk be-

tween exposed and unexposed indi-

viduals, we constructed a summary car-

diovascular risk score (CRS).

23,24

The

CRS was based on inpatient and out-

patient diagnoses (from claims or

encounter databases) and pharmacy

records and included CVD and medi-

cations, mental health conditions

(excluding ADHD) and use of psycho-

tropic medications, other health con-

ditions (eg, diabetes mellitus, obesity,

smoking-related) and medications, and

health care utilization (TABLE 1 and

eTable 3).

For each end point (MI, SCD, stroke,

or any serious cardiovascular event), a

separate score was created froma Pois-

son regression model among all pa-

tients, adjusted for ADHD medica-

tions and matching variables (age, sex,

data site, calendar year at cohort en-

try). The score was the linear predic-

tor from the coefficients of the result-

ing regression model, excluding the

coefficients for ADHDmedications and

the matching variables.

Inprimary analyses, several CRS vari-

ables not thought to be on the causal

pathway between medication use and

our outcomes were treatedas time vary-

ing (eTable 3). In secondary analyses,

all CRS variables were based on diag-

noses or medication use in the 365 days

prior to cohort entry and fixed at base-

line. For the new-user analyses, we used

the CRS for comparisons of current vs

remote use and constructed a propen-

sity score

25

for current vs nonuse of

ADHD medications at cohort entry,

using variables included in the CRS.

Unmeasured Confounders

To examine the possible extent and di-

rection of unmeasured confounding by

risk factors for CVD on which infor-

mation was not or was inconsistently

available in the electronic health care

records, we conductedsensitivity analy-

ses using information on potential con-

founders from 2 sources. Race/

ethnicity, smoking, obesity, history of

CVD, and drug abuse were obtained

from the adjudicated records of MI,

SCD, andstroke cases. Inaddition, race/

ethnicity, income, education, smok-

ing, obesity, and family history of CVD

were available for approximately

200 000 KP Northern California mem-

bers aged 25 through 64 years who

completed a mailed survey for a differ-

ent study in 2007 (eMethods). Elec-

tronic pharmacy records for ADHD

medications were obtained for survey

participants.

We used multivariable logistic re-

gression to examine the association be-

tween potential confounders (from

either survey or chart reviews) and use

of ADHDmedications. For variables as-

sociated with use of ADHD medica-

tions, we assessedthe extent of their po-

tential confounding effect on rate ratios

(RRs) for MI, SCD, or stroke associ-

ated withADHDmedications, using ex-

ternal adjustment methods.

26-28

This ap-

proachassumedthat associations inour

study population were similar to those

ADHD MEDICATIONS AND CV EVENTS IN YOUNGER ADULTS

2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. JAMA, Published online December 12, 2011 E3

by guest on December 14, 2011 jama.ama-assn.org Downloaded from

in our external samples and did not ad-

dress joint confounding by several un-

measured covariates.

Statistical Analysis

Follow-up began at cohort entry and

endedat 1 of the 4 endpoints (MI, SCD,

stroke, or any of these serious cardio-

vascular events), death, end of insur-

ance coverage or pharmacy benefit, day

before 65thbirthday, or endof study pe-

riod (December 2005), whichever came

first. Poisson regression was used to es-

timate the association of ADHD medi-

cation use with risk of serious cardio-

vascular events, while adjusting for

potentially confounding variables. Co-

variates inthe full model includedstudy

site, age (5-year dummy categories), sex,

calendar year (1986-1992, 1993-1999,

2000-2001, 2002-2003, 2004-2005), and

CRS (specified as decile dummies).

Matching variables (site, age, sex, cal-

endar year at cohort entry) were in-

cluded in the full model because,

althoughmatchingensuredbalance with

respect to these variables at baseline, it

didnot ensure balance duringfollow-up.

To minimize biases related to under-

ascertainment of events occurring early

in therapy,

29

we also conducted analy-

ses restricted to new users of ADHD

medications (no use in the year prior

to baseline). In these analyses, risk dur-

ing periods of current use was com-

pared with risk during periods remote

from last use. Current use among new

users also was compared with nonuse

(in their matches).

To examine whether associations

could be influenced by prior disease

conditions, we conducted subgroup

analyses. In one analysis, users were re-

stricted to those with a prior diagnosis

of ADHDand compared with matched

nonusers. Additional subgroups were

based on prior CVD, prior non-ADHD

psychiatric diagnoses or medicationuse,

age (25-44 vs 45-64 years) during fol-

low-up, and data site.

When examining rates of any seri-

ous cardiovascular event in the full co-

hort, we had 80% power to detect RRs

of 1.23 for current use vs nonuse and

1.30 for current use vs remote use. In

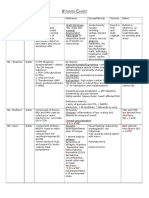

Table 1. Selected Characteristics of Study Cohort at Baseline

a

Characteristic Current Use Nonuse

No. of unique individuals 150 359 292 839

No. of membership periods

b

152 852 293 749

Year of cohort entry, median 2003 2003

Person-years during follow-up

c

107 322 533 540

Demographic and Clinical

Demographics

Age, median (IQR), y 42 (34-49) 42 (34-49)

Male sex 70 245 (46.0) 135 002 (46.0)

Medicaid enrollment 14 786 (9.7) 29 171 (9.9)

ADHD medication

Amphetamines 57 824 (37.8)

Methylphenidate 70 923 (46.4)

Atomoxetine 19 283 (12.6)

Pemoline 3973 (2.6)

Multiple 849 (0.6)

Cardiovascular disease within past year

d

Acute MI 340 (0.2) 689 (0.2)

Ischemia 3998 (2.6) 6857 (2.3)

Coronary revascularization 253 (0.2) 643 (0.2)

Congestive heart failure 1112 (0.7) 1759 (0.6)

Arrhythmia 3560 (2.3) 5076 (1.7)

Stroke/transient ischemic attack 1826 (1.2) 2075 (0.7)

Congenital heart disorder 331 (0.2) 556 (0.2)

Coronary artery anomaly 66 (0.0) 89 (0.0)

Peripheral vascular disease 1225 (0.8) 1651 (0.6)

Hypertension 22 562 (14.8) 39 011 (13.3)

Hyperlipidemia

e

28 613 (18.7) 42 601 (14.5)

Mental health claims within past year

ADHD 46 356 (30.3) 455 (0.2)

Major depression 61 417 (40.2) 23 296 (7.9)

Bipolar disorder 11 196 (7.3) 2682 (0.9)

Anxiety 30 472 (19.9) 15 670 (5.3)

Psychotic disorders 2494 (1.6) 1833 (0.6)

Other selected medical conditions within past year

Diabetes

e

8972 (5.9) 15 862 (5.4)

Obesity 9119 (6.0) 11 439 (3.9)

Smoking 11 579 (7.6) 14 717 (5.0)

Alcohol/substance abuse 7965 (5.2) 4514 (1.5)

Suicide attempt 795 (0.5) 410 (0.1)

Injury 30 655 (20.1) 37 559 (12.8)

Seizure 3062 (2.0) 2854 (1.0)

Asthma 11 627 (7.6) 12 432 (4.2)

Use of cardiovascular drug within past year

d

Loop diuretic 4328 (2.8) 4932 (1.7)

Digoxin 587 (0.4) 1130 (0.4)

Nitrates 1941 (1.3) 3298 (1.1)

Anticoagulant 1768 (1.2) 2421 (0.8)

Platelet inhibitor 996 (0.7) 1675 (0.6)

Antiarrhythmic agents 556 (0.4) 631 (0.2)

ACE inhibitor 10 719 (7.0) 19 796 (6.7)

Angiotensin receptor blocker 3652 (2.4) 5988 (2.0)

-Blocker 12 431 (8.1) 19 091 (6.5)

Calcium-channel blocker 7028 (4.6) 12 233 (4.2)

Thiazide diuretic 12 471 (8.2) 20 008 (6.8)

Other antihypertensive 1668 (1.1) 2192 (0.7)

(continued)

ADHD MEDICATIONS AND CV EVENTS IN YOUNGER ADULTS

E4 JAMA, Published online December 12, 2011 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

by guest on December 14, 2011 jama.ama-assn.org Downloaded from

new-user analyses, the least detectable

RRs were 1.31 for current use vs non-

use and 1.38 for current vs remote use.

All analyses were performed using

SAS version 9.1. For all RR estimates,

95% confidence limits were reported.

RESULTS

The study included a total of 443 198

adults, of whom150 359 were users of

ADHD medications at baseline. Meth-

ylphenidate accounted for 45%of cur-

rent use; amphetamine, for 44%; ato-

moxetine, for 8%; andpemoline, for 3%.

Characteristics of Study Population

Baseline characteristics of users and

nonusers are reported in Table 1; char-

acteristics of person-time by medica-

tion use are reported in eTable 3. Car-

diovascular diseases were generally

uncommon and similar or modestly

more prevalent in users than nonus-

ers. As expected, ADHD was substan-

tially more common among current us-

ers than nonusers. This also was true

for other psychiatric conditions. The

prevalences of cardiovascular risk fac-

tors were modestly higher during pe-

riods of remote use than during peri-

ods of current use or nonuse.

Number of Events and RRs

in the Full Cohort

During 806 182 person-years of fol-

low-up (median, 1.3 [interquartile

range, 0.6-2.6] years per person), 1357

cases of MI, 296 cases of SCD, and 575

cases of stroke occurred. There were

107 322 person-years of current use

(median, 0.33 [range, 0.0-13.5] years

per user), with a crude incidence per

1000 person-years of 1.34 (95% CI,

1.14-1.57) for MI, 0.30 (95%CI, 0.20-

0.42) for SCD, and 0.56 (95%CI, 0.43-

0.72) for stroke.

In analysis adjusted for matching

variables only, the RR of MI, SCD, or

stroke for current vs nonuse of ADHD

medications was 0.97 (95% CI, 0.84-

1.12). After also adjusting for the CRS,

the RR was modestly lower (0.83 [95%

CI, 0.72-0.96]). Results were similar for

specific medications and across end

points (FIGURE 1 and eTable 4). Rate

ratios also were similar for ischemic or

hemorrhagic stroke (eTable 5Aand B).

Findings for SCD and stroke changed

only minimally when all electroni-

cally identified cases were included ex-

cept those adjudicated as noncases

(eTable 6Aand B). Overall results were

essentially unchanged when all vari-

ables in the CRS were fixed at baseline

(eTable 7).

Table 1. Selected Characteristics of Study Cohort at Baseline

a

(continued)

Characteristic Current Use Nonuse

Demographic and Clinical (cont.)

Use of psychotropic medications within past year

Antipsychotic, any 14 618 (9.6) 5371 (1.8)

Tricyclic antidepressant 14 224 (9.3) 9907 (3.4)

Antidepressants, other or SSRI/SNRI 81 639 (53.4) 36 962 (12.6)

Benzodiazepines 43 695 (28.6) 25 956 (8.8)

Lithium 4177 (2.7) 1002 (0.3)

Modafinil 4732 (3.1) 383 (0.1)

Insomnia medications 15 270 (10.0) 6732 (2.3)

Thioridazine 307 (0.2) 181 (0.1)

Mood stabilizers, without seizure 22 426 (14.7) 8631 (2.9)

Clonidine/guanfacine, without hypertension 2000 (1.3) 659 (0.2)

Use of other selected medications within past year

-Agonist 18 971 (12.4) 20 835 (7.1)

Epinephrine 1342 (0.9) 1274 (0.4)

Asthma medications, other 39 645 (25.9) 45 102 (15.4)

Seizure medications, any 24 139 (15.8) 10 397 (3.5)

Theophylline compounds (asthma medication) 960 (0.6) 1200 (0.4)

COX-2 inhibitors 10 666 (7.0) 10 838 (3.7)

Other drugs to improve blood flow 216 (0.1) 250 (0.1)

Clonidine 2602 (1.7) 1787 (0.6)

Phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors 5183 (3.4) 4504 (1.5)

Triptans 7164 (4.7) 5298 (1.8)

Oral contraceptives 18 379 (12.0) 28 590 (9.7)

Hormones, menopausal 18 026 (11.8) 23 388 (8.0)

Health Care Utilization Within Past Year

Cardiovascular visits

Emergency, 1 5728 (3.7) 7697 (2.6)

Inpatient, 1 6022 (3.9) 7130 (2.4)

Physician, 1-4 43 474 (28.4) 65 256 (22.2)

Physician, 5 13 242 (8.7) 17 713 (6.0)

Psychiatric visits

f

Emergency, 1 4417 (2.9) 2897 (1.0)

Inpatient, 1 7761 (5.1) 3827 (1.3)

Physician, 1-4 43 538 (28.5) 26 703 (9.1)

Physician, 5 40 176 (26.3) 11 048 (3.8)

Other visits

Emergency, 1 7885 (5.2) 9594 (3.3)

Inpatient, 1 5812 (3.8) 5595 (1.9)

Physician, 1 55 386 (36.2) 69 134 (23.5)

No. of different medications

g

1 24 309 (15.9) 61 193 (20.8)

2 108 955 (71.3) 116 680 (39.7)

Abbreviations: ACE, angiotensin-converting enzyme; ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; COX-2, cyclooxy-

genase 2; IQR, interquartile range; MI, myocardial infarction; SNRI, serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor;

SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

a

Data are presented as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated.

b

All variables in table included in cardiovascular risk score, except demographics and ADHD. Percentages are based

on membership periods. There were 299 indeterminate and former users at baseline.

c

Follow-up time based on combined end point (MI, sudden cardiac death, or stroke).

d

Variables used to define history of cardiovascular disease for subgroup analyses in Figure 2.

e

Including medications.

f

Excluding ADHD visits.

g

Excluding ADHD medications.

ADHD MEDICATIONS AND CV EVENTS IN YOUNGER ADULTS

2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. JAMA, Published online December 12, 2011 E5

by guest on December 14, 2011 jama.ama-assn.org Downloaded from

Analyses Restricted to Users

of ADHD Medications

(Remote Use Comparison)

Among ever users of ADHD medica-

tions, the adjusted RR of serious car-

diovascular events was nearly the same

during periods of current use as dur-

ing follow-up periods more than 1 year

after use ended(RR, 1.03[95%CI, 0.86-

1.24]) (TABLE 2). This 1.24 estimated

upper bound for the RR would corre-

spond to an absolute risk difference of

0.17 serious cardiovascular events per

1000 person-years in adults aged 25

through 44 years (ages at which the ab-

solute risk was only 0.87 per 1000 per-

son-years) and of 0.68 serious cardio-

vascular events per 1000 person-years

in adults aged 45 through 64 years

(ages at which the absolute risk dur-

ing current use was 3.5 per 1000 per-

son-years).

New-User Analyses

In the new-user cohort, baseline char-

acteristics of newusers of ADHDmedi-

cation were generally similar to charac-

teristics of all ADHD medication users

(eTable 8). Cardiovascular diseases were

similar or slightly more prevalent innew

users than nonusers. ADHD and other

psychiatric conditions were substan-

tially more common in new users than

in nonusers. In the new-user analyses,

RRs for current vs remote use were close

to 1.0 for MI, stroke, and the combined

end point (TABLE 3). Although not sta-

tistically significant, RRs for methylphe-

nidate were 1.26(95%CI, 0.88-1.80) for

MI, 1.44 (95%CI, 0.90-2.30) for stroke,

and 1.20 (95% CI, 0.91-1.59) for the

combinedendpointsomewhat higher

than the RRs for the other drugs.

For the combinedendpoint, there was

no pattern of increasing risk with in-

creasing duration of current use or for

any windowof time. For current use (all

durations combined) vs remote use, the

RRfor the combinedendpoint was 1.02.

The upper boundof the CI was 1.28; this

would amount to an additional 0.19

events per 1000 person-years at ages 25

through44 years and anadditional 0.77

events per 1000 person-years at ages 45

through 64 years.

Subgroup Analyses

Rate ratios were similar in all sub-

group analyses (FIGURE 2 and eTable

9). Although we did observe differ-

ences in event rates, cohort character-

istics, and RRs by data site, RRs for

current use were not statistically sig-

nificantly elevated at any site (eTables

10, 11, and 12).

Sensitivity Analyses

Unmeasured Confounding

Informationfromreviewof medical rec-

ords of MI, SCD, and stroke cases and

the external survey population sug-

gestedthat several factors (obesity, smok-

ing, family history of CVD) were not or

were only very weakly associated with

use of ADHD medications and there-

Figure 1. Adjusted Rate Ratios for Serious Cardiovascular Events Associated With Use vs

Nonuse of ADHD Medications

Lower Risk Higher Risk

0.2 5.0 1.0

Rate Ratio (95% CI)

No. of

Events

Outcome and ADHD

Medication Use Person-Years

Rate Ratio

(95% CI)

MI

152 Current use 113 324.2 0.88 (0.74-1.05)

86 Indeterminate use 53 896.7 1.07 (0.85-1.33)

65 Former use 47 858.5 0.78 (0.61-1.00)

147 Remote use 69 792.9 0.82 (0.68-0.97)

907 Nonuse 559 743.1 1 [Reference]

59 Amphetamines 49 080.1 0.92 (0.70-1.19)

77 Methylphenidate 51 232.8 0.89 (0.71-1.13)

11 Atomoxetine 8424.8 0.87 (0.48-1.57)

5 Pemoline 3047.3 0.71 (0.29-1.71)

0 Multiple 1539.1 NA

0.2 5.0 1.0

Rate Ratio (95% CI)

SCD

32 Current use 107 525.0 0.80 (0.55-1.18)

14 Indeterminate use 51 814.0 0.73 (0.42-1.26)

20 Former use 46 263.5 0.90 (0.57-1.44)

50 Remote use 68 102.6 0.98 (0.71-1.35)

180 Nonuse 535 515.5 1 [Reference]

13 Amphetamines 46 910.0 0.93 (0.52-1.63)

13 Methylphenidate 47 887.1 0.67 (0.38-1.18)

4 Atomoxetine 8257.6 1.04 (0.38-2.82)

2 Pemoline 2995.7 1.08 (0.27-4.37)

0 Multiple 1474.5 NA

0.2 5.0 1.0

Rate Ratio (95% CI)

Stroke

63 Current use 111 935.5 0.76 (0.58-1.00)

31 Indeterminate use 53 327.8 0.83 (0.57-1.19)

39 Former use 47 333.0 1.01 (0.73-1.41)

67 Remote use 69 202.3 0.82 (0.63-1.07)

375 Nonuse 553 458.5 1 [Reference]

19 Amphetamines 48 672.9 0.63 (0.40-1.01)

39 Methylphenidate 50 332.3 0.94 (0.68-1.32)

3 Atomoxetine 8371.1 0.44 (0.14-1.38)

2 Pemoline 3030.1 0.59 (0.15-2.39)

0 Multiple 1529.2 NA

0.2 5.0 1.0

Rate Ratio (95% CI)

MI, SCD, or stroke

234 Current use 107 322.4 0.83 (0.72-0.96)

125 Indeterminate use 51 709.6 0.94 (0.78-1.13)

121 Former use 46 120.8 0.86 (0.72-1.04)

243 Remote use 67 489.0 0.81 (0.70-0.93)

1391 Nonuse 533 540.4 1 [Reference]

88 Amphetamines 46 826.5 0.85 (0.68-1.05)

120 Methylphenidate 47 792.3 0.87 (0.72-1.04)

17 Atomoxetine 8248.2 0.74 (0.46-1.19)

9 Pemoline 2985.2 0.75 (0.39-1.45)

0 Multiple 1470.1 NA

Rate ratios are adjusted for site, age, sex, calendar year, and cardiovascular risk score (some variables

within score are time varying). ADHD indicates attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder; MI, myocardial

infarction; NA, not applicable; SCD, sudden cardiac death.

ADHD MEDICATIONS AND CV EVENTS IN YOUNGER ADULTS

E6 JAMA, Published online December 12, 2011 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

by guest on December 14, 2011 jama.ama-assn.org Downloaded from

fore were unlikely to be important con-

founders. However, in these data, users

of ADHD medications more often had

some college education compared with

nonusers (17% vs 10%, adjusting for

age). Inaddition, 5%of the stimulant us-

ers were black or Hispanic vs 12%of the

nonusers. If similar patterns for race/

ethnicity and education were also pre-

sent in our full study cohort, and if each

of these characteristics independently

multiplied the risk of serious cardiovas-

cular events by 2.4, thenthese 2 unmea-

sured factors would yield a healthy-

user bias substantial enough to account

for an apparent RR of 0.83 (as in our

comparison of current use vs nonuse),

given a true RR of 1.0.

COMMENT

Inour population-based cohort of more

than 440 000 young and middle-aged

adults, including more than150000 us-

ers of ADHD medications identified

through filled prescriptions, we found

no evidence of an increased risk of MI,

SCD, or stroke associated with cur-

rent use compared with nonuse or re-

Table 2. Adjusted Rate Ratios for Serious Cardiovascular Events Associated With Periods of Current Use of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Disorder Medications vs Periods Remote From Last Use

Medication Status Person-Years

No. of

Events

Rate/1000

Person-Years

RR (95% CI)

Unadjusted

Adjusted

Matching-Variables

a

Adjusted

b

MI

Current use 113 324.2 152 1.34 0.64 (0.51-0.80) 0.98 (0.78-1.23) 1.08 (0.86-1.36)

Amphetamines 49 080.1 59 1.20 0.57 (0.42-0.77) 0.99 (0.73-1.34) 1.12 (0.83-1.52)

Methylphenidate 51 232.8 77 1.50 0.71 (0.54-0.94) 1.00 (0.76-1.32) 1.10 (0.83-1.45)

Atomoxetine 8424.8 11 1.31 0.62 (0.34-1.14) 0.99 (0.54-1.84) 1.06 (0.57-1.96)

Pemoline 3047.3 5 1.64 0.78 (0.32-1.90) 0.87 (0.36-2.13) 0.87 (0.36-2.12)

Multiple 1539.1 0 0.00 NA NA NA

Indeterminate use 53 896.7 86 1.60 0.76 (0.58-0.99) 1.19 (0.91-1.56) 1.31 (1.00-1.71)

Former use 47 858.5 65 1.36 0.64 (0.48-0.86) 0.92 (0.68-1.23) 0.96 (0.71-1.28)

Remote use 69 792.9 147 2.11 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference]

SCD

c

Current use 107 525.0 32 0.30 0.41 (0.26-0.63) 0.79 (0.50-1.24) 0.82 (0.52-1.29)

Amphetamines 46 910.0 13 0.28 0.38 (0.21-0.69) 0.85 (0.46-1.58) 0.94 (0.51-1.76)

Methylphenidate 47 887.1 13 0.27 0.37 (0.20-0.68) 0.66 (0.36-1.23) 0.68 (0.37-1.27)

Atomoxetine 8257.6 4 0.48 0.66 (0.24-1.83) 1.14 (0.41-3.18) 1.06 (0.38-2.95)

Pemoline 2995.7 2 0.67 0.91 (0.22-3.74) 1.11 (0.27-4.59) 1.10 (0.27-4.56)

Multiple 1474.5 0 0.00 NA NA NA

Indeterminate use 51 814.0 14 0.27 0.37 (0.20-0.67) 0.70 (0.39-1.28) 0.74 (0.41-1.35)

Former use 46 263.5 20 0.43 0.59 (0.35-0.99) 0.94 (0.56-1.58) 0.92 (0.55-1.55)

Remote use 68 102.6 50 0.73 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference]

Stroke

d

Current use 111 935.5 63 0.56 0.58 (0.41-0.82) 0.90 (0.63-1.28) 0.93 (0.65-1.31)

Amphetamines 48 672.9 19 0.39 0.40 (0.24-0.67) 0.70 (0.42-1.18) 0.77 (0.46-1.29)

Methylphenidate 50 332.3 39 0.77 0.80 (0.54-1.19) 1.15 (0.77-1.72) 1.15 (0.77-1.72)

Atomoxetine 8371.1 3 0.36 0.37 (0.12-1.18) 0.55 (0.17-1.75) 0.54 (0.17-1.71)

Pemoline 3030.1 2 0.66 0.68 (0.17-2.78) 0.74 (0.18-3.04) 0.72 (0.18-2.96)

Multiple 1529.2 0 0.00 NA NA NA

Indeterminate use 53 327.8 31 0.58 0.60 (0.39-0.92) 0.96 (0.63-1.48) 1.01 (0.65-1.54)

Former use 47 333.0 39 0.82 0.85 (0.57-1.26) 1.24 (0.85-1.85) 1.23 (0.83-1.83)

Remote use 69 202.3 67 0.97 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference]

MI, SCD, or stroke

c,d

Current use 107 322.4 234 2.18 0.61 (0.51-0.72) 0.96 (0.80-1.15) 1.03 (0.86-1.24)

Amphetamines 46 826.5 88 1.88 0.52 (0.41-0.67) 0.93 (0.73-1.19) 1.05 (0.82-1.34)

Methylphenidate 47 792.3 120 2.51 0.70 (0.56-0.87) 1.01 (0.81-1.26) 1.07 (0.86-1.34)

Atomoxetine 8248.2 17 2.06 0.57 (0.35-0.94) 0.90 (0.55-1.48) 0.92 (0.56-1.50)

Pemoline 2985.2 9 3.01 0.84 (0.43-1.63) 0.95 (0.49-1.85) 0.93 (0.48-1.82)

Multiple 1470.1 0 0.00 NA NA NA

Indeterminate use 51 709.6 125 2.42 0.67 (0.54-0.83) 1.09 (0.88-1.35) 1.17 (0.94-1.45)

Former use 46 120.8 121 2.62 0.73 (0.59-0.91) 1.06 (0.85-1.32) 1.07 (0.86-1.33)

Remote use 67 489.0 243 3.60 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference]

Abbreviations: MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not applicable; RR, rate ratio; SCD, sudden cardiac death.

a

Adjusted for site, age, sex, and calendar year (ie, matching variables).

b

Adjusted for site, age, sex, calendar year, and cardiovascular risk score (some variables within score are time varying).

c

Analyses excluded the 3 Health Maintenance Organization Research Network (HMORN) sites (Fallon Community, Kaiser Permanente [KP] Georgia, KP Northwest) that did not

provide data on SCD end points.

d

Analyses excluded the 2 HMORN sites (Fallon Community, KP Georgia) that did not provide data on stroke end points.

ADHD MEDICATIONS AND CV EVENTS IN YOUNGER ADULTS

2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. JAMA, Published online December 12, 2011 E7

by guest on December 14, 2011 jama.ama-assn.org Downloaded from

mote use of ADHD medications. We

also found little support for an in-

creased risk with any specific medica-

tion or with longer duration of cur-

rent use. Results were similar when

users were restricted to newusers. Rate

ratios did not appear to be influenced

by prior CVD or by prior non-ADHD

psychiatric conditions. They also were

similar across age groups. As ex-

pected, event rates were substantially

higher in the Medicaid population;

however, the RR for current use was

similar to that in other sites.

Our study has several limitations. Use

of ADHD medications was based on

electronic pharmacy records of filled

prescriptions. Filled prescriptions may

Table 3. Adjusted Rate Ratios for Serious Cardiovascular Events Associated With Periods of New Use of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Disorder Medications vs Periods Remote From Last Use

Medication Status Person-Years

No. of

Events

Rate/1000

Person-Years

RR (95% CI)

Unadjusted

Adjusted

Matching-Variables

a

Adjusted

b

MI

Current use 55 533.9 77 1.39 0.67 (0.50-0.89) 1.04 (0.77-1.39) 1.08 (0.81-1.45)

Amphetamines 23 265.6 24 1.03 0.50 (0.32-0.77) 0.86 (0.55-1.34) 0.94 (0.60-1.46)

Methylphenidate 23 930.8 42 1.76 0.84 (0.59-1.20) 1.23 (0.86-1.75) 1.26 (0.88-1.80)

Atomoxetine 6475.3 9 1.39 0.67 (0.34-1.31) 1.06 (0.54-2.10) 1.06 (0.54-2.10)

Pemoline 1114.4 2 1.79 0.86 (0.21-3.49) 0.76 (0.19-3.07) 0.75 (0.18-3.03)

Multiple 747.7 0 0.00 NA NA NA

Duration, d

c

1-30 7526.3 11 1.46 0.70 (0.38-1.30) 1.26 (0.68-2.33) 1.31 (0.70-2.43)

31-90 9656.8 11 1.14 0.55 (0.29-1.01) 1.01 (0.54-1.88) 1.06 (0.57-1.96)

91-182 9556.3 8 0.84 0.40 (0.20-1.47) 0.71 (0.35-1.47) 0.75 (0.36-1.53)

183-365 11 221.9 16 1.43 0.68 (0.41-1.15) 1.13 (0.67-1.92) 1.19 (0.70-2.01)

366 16 425.2 29 1.77 0.85 (0.56-1.27) 1.09 (0.72-1.64) 1.15 (0.76-1.73)

Indeterminate use 31 090.0 52 1.67 0.80 (0.58-1.11) 1.27 (0.92-1.77) 1.32 (0.95-1.84)

Former use 35 087.7 55 1.57 0.75 (0.55-1.04) 1.08 (0.78-1.49) 1.08 (0.78-1.49)

Remote use 55 194.2 115 2.08 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference]

SCD

d

Current use 52 203.2 15 0.29 0.34 (0.19-0.62) 0.61 (0.34-1.09) 0.62 (0.34-1.11)

Amphetamines 22 002.7 3 0.14 0.16 (0.05-0.53) 0.34 (0.11-1.10) 0.38 (0.12-1.22)

Methylphenidate 22 056.6 8 0.36 0.43 (0.20-0.92) 0.70 (0.33-1.50) 0.69 (0.32-1.46)

Atomoxetine 6348.4 3 0.47 0.57 (0.18-1.82) 0.95 (0.29-3.09) 0.90 (0.28-2.91)

Pemoline 1091.6 1 0.92 1.10 (0.15-7.96) 0.90 (0.12-6.63) 0.93 (0.13-6.77)

Multiple 703.9 0 0.00 NA NA NA

Duration, d

c

1-30 7217.4 2 0.28 0.33 (0.08-1.37) 0.67 (0.16-2.79) 0.68 (0.16-2.81)

31-90 9195.9 2 0.22 0.26 (0.06-1.07) 0.56 (0.13-2.30) 0.56 (0.14-2.33)

91-182 9026.0 4 0.44 0.53 (0.19-2.30) 1.09 (0.39-3.04) 1.11 (0.40-3.10)

183-365 10 511.3 1 0.10 0.11 (0.02-0.83) 0.22 (0.03-1.59) 0.22 (0.03-1.62)

366 15 129.8 5 0.33 0.40 (0.16-1.00) 0.57 (0.22-1.43) 0.57 (0.22-1.43)

Indeterminate use 29 752.7 13 0.44 0.52 (0.28-0.97) 0.94 (0.50-1.75) 0.96 (0.52-1.79)

Former use 33 877.6 16 0.47 0.57 (0.32-1.00) 0.89 (0.50-1.57) 0.88 (0.50-1.56)

Remote use 53 926.6 45 0.83 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference]

Stroke

e

Current use 54 569.3 41 0.75 0.73 (0.49-1.10) 1.10 (0.73-1.65) 1.09 (0.72-1.64)

Amphetamines 22 965.2 10 0.44 0.43 (0.22-0.83) 0.72 (0.37-1.41) 0.77 (0.39-1.53)

Methylphenidate 23 335.7 26 1.11 1.09 (0.68-1.73) 1.53 (0.96-2.45) 1.44 (0.90-2.30)

Atomoxetine 6429.4 3 0.47 0.46 (0.14-1.46) 0.66 (0.20-2.11) 0.64 (0.20-2.04)

Pemoline 1099.7 2 1.82 1.78 (0.43-7.28) 1.48 (0.36-6.08) 1.39 (0.34-5.72)

Multiple 739.3 0 0.00 NA NA NA

Duration, d

c

1-30 7421.0 4 0.54 0.53 (0.19-6.08) 0.93 (0.34-2.57) 0.92 (0.33-2.53)

31-90 9511.8 6 0.63 0.62 (0.27-1.43) 1.10 (0.47-2.57) 1.08 (0.46-2.51)

91-182 9398.0 9 0.96 0.94 (0.46-1.89) 1.59 (0.78-3.23) 1.55 (0.76-3.14)

183-365 11 018.6 4 0.36 0.35 (0.13-0.98) 0.56 (0.20-1.55) 0.55 (0.20-1.53)

366 16 087.6 16 0.99 0.97 (0.56-1.69) 1.19 (0.68-2.09) 1.21 (0.69-2.11)

Indeterminate use 30 657.1 20 0.65 0.64 (0.38-1.06) 1.00 (0.60-1.66) 1.0 (0.60-1.67)

Former use 34 644.6 26 0.75 0.73 (0.46-1.17) 1.05 (0.66-1.68) 1.04 (0.65-1.65)

Remote use 54 702.5 56 1.02 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference]

(continued)

ADHD MEDICATIONS AND CV EVENTS IN YOUNGER ADULTS

E8 JAMA, Published online December 12, 2011 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

by guest on December 14, 2011 jama.ama-assn.org Downloaded from

not represent medications actually con-

sumed, and days supply may not rep-

resent actual periods of use. Nonethe-

less, electronic pharmacy databases

have beenfound to be excellent sources

of information on drug use.

30

We did

not obtaindose data andtherefore could

not examine if risk varied by this fac-

tor. Although we used a strict defini-

tion of current use, minimizing mis-

classification of this exposure, we had

limited ability to assess medication ad-

herence using standard definitions. De-

spite its large size, the study had only

moderate power for several compari-

sons, including current vs remote use

in the new-user analyses and in com-

parisons for individual drugs. The study

did not include adults 65 years and

older; therefore, results cannot be gen-

eralized to this age group.

We reviewed medical records and

death certificates to confirm SCD and

stroke diagnoses. However, records

were unavailable for some of our elec-

tronically identified cases. We used an

ICD-9/ICD-10 codebased definition

for these cases, and misclassification

of some cases may have occurred. If

nondifferential with respect to ADHD

medication use, this misclassification

would bias RRs toward the null.

The accuracy of ADHDdiagnoses in

adults from claims and encounter da-

tabases is limited. However, previous

studies have validated ICD 9/ICD-10

codebased definitions of many impor-

tant covariates, including diabetes, con-

gestive heart failure, peripheral vascu-

lar disease, and hypertension, reporting

positive predictive values exceeding

90% for each condition.

31-33

Although

we adjusted for numerous established

and potential cardiovascular risk fac-

tors, there were some factors, primar-

ily psychiatric conditions and medica-

tions, for which the prevalence was

substantial in users of ADHD medica-

tions but rare innonusers. Thus, we had

limited ability to adjust for these vari-

ables. Important residual confound-

ing by psychiatric conditions and medi-

cations seems unlikely, because most

are not established risk factors for CVD,

they were not or were only modestly re-

lated to risk in our cohort, and results

were similar when we restricted analy-

ses to participants withor to those with-

out these psychiatric conditions or

medication use.

There appears to be a modest amount

of healthy-user bias influencing our RR

comparisons of current use vs nonuse.

Results are less prone to this bias when

analyses are restricted to ever users of

ADHD medications, and we compared

periods of current use withfollow-uppe-

riods remote from use. In these com-

parisons, the RR for serious cardiovas-

cular events was 1.03 in the full cohort

and 1.02 in new users, indicating that

the incidence of these events while cur-

rently receiving ADHD medications is

similar to the incidence during periods

while not receiving these medications.

In sensitivity analyses, we saw evi-

dence for 2 potential sources of a mod-

est amount of healthy-user bias: a higher

percentage of users were white and col-

lege educated.

Clinical trials have provided limited

informationonthe cardiovascular safety

of ADHD medications, primarily be-

cause these trials have been too small to

evaluate serious events suchas MI, SCD,

or stroke.

34,35

Postmarketing surveil-

lance data from the Adverse Event Re-

porting System

2

and from the National

Electronic Injury Surveillance System

36

have suggested a potential elevation in

Table 3. Adjusted Rate Ratios for Serious Cardiovascular Events Associated With Periods of New Use of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Disorder Medications vs Periods Remote From Last Use (continued)

Medication Status Person-Years

No. of

Events

Rate/1000

Person-Years

RR (95% CI)

Unadjusted

Adjusted

Matching-Variables

a

Adjusted

b

MI, SCD, or stroke

d,e

Current use 52 094.6 125 2.40 0.65 (0.52-0.81) 1.00 (0.80-1.26) 1.02 (0.82-1.28)

Amphetamines 21 955.8 37 1.69 0.46 (0.32-0.65) 0.80 (0.56-1.13) 0.87 (0.61-1.23)

Methylphenidate 22 008.8 69 3.14 0.85 (0.65-1.12) 1.22 (0.92-1.60) 1.20 (0.91-1.59)

Atomoxetine 6340.4 14 2.21 0.60 (0.35-1.03) 0.93 (0.54-1.60) 0.91 (0.53-1.56)

Pemoline 1088.1 5 4.60 1.25 (0.51-3.03) 1.07 (0.44-2.61) 1.02 (0.42-2.49)

Multiple 701.4 0 0.00 NA NA NA

Duration, d

c

1-30 7215.7 16 2.22 0.60 (0.36-1.00) 1.08 (0.65-1.80) 1.10 (0.66-1.83)

31-90 9191.7 19 2.07 0.56 (0.35-0.90) 1.04 (0.65-1.66) 1.05 (0.66-1.69)

91-182 9018.3 18 2.00 0.54 (0.33-0.88) 0.96 (0.59-1.55) 0.97 (0.60-1.57)

183-365 10 494.1 20 1.91 0.52 (0.33-0.82) 0.85 (0.53-1.34) 0.86 (0.54-1.37)

366 15 055.5 47 3.12 0.85 (0.62-1.16) 1.06 (0.77-1.46) 1.10 (0.80-1.51)

Indeterminate use 29 694.2 82 2.76 0.75 (0.58-0.97) 1.19 (0.92-1.55) 1.22 (0.94-1.58)

Former use 33 774.3 97 2.87 0.78 (0.61-0.99) 1.13 (0.88-1.44) 1.11 (0.87-1.41)

Remote use 53 450.1 197 3.69 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference] 1 [Reference]

Abbreviations: MI, myocardial infarction; NA, not applicable; RR, rate ratio; SCD, sudden cardiac death.

a

Adjusted for site, age, sex, and calendar year (ie, matching variables).

b

Adjusted for site, age, sex, calendar year, and cardiovascular risk score (some variables within score are time varying).

c

Duration does not include pemoline use (pemoline only and pemoline with other attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications).

d

Analyses excluded the 3 Health Maintenance Organization Research Network (HMORN) sites (Fallon Community, Kaiser Permanente [KP] Georgia, KP Northwest) that did not

provide data on SCD end points.

e

Analyses excluded the 2 HMORN sites (Fallon Community, KP Georgia) that did not provide data on stroke end points.

ADHD MEDICATIONS AND CV EVENTS IN YOUNGER ADULTS

2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. JAMA, Published online December 12, 2011 E9

by guest on December 14, 2011 jama.ama-assn.org Downloaded from

risk of serious cardiovascular events.

However, with these surveillance sys-

tems, which capture only a small per-

centage of adverse events, false signals

may occur if clinicians suspect, and are

thus more likelytoreport, adverse events

for a particular drug.

The findings of the current study

were similar to those of our parallel

study in youths aged 2 through 24

years, in which we found no evidence

of increased risk for serious cardiovas-

cular events in current users of ADHD

medications compared with nonus-

ers.

19

To our knowledge, only 2 phar-

macoepidemiologic studies of ADHD

medications and CVD in adults have

reported results.

17,18

These studies,

which were substantially smaller than

ours, used electronic pharmacy rec-

ords and medical encounter data,

with similarly limited information on

some potentially important risk fac-

tors. In one study, users of ADHD

medications had a more than 3-fold

higher rate of transient ischemic

attacks but a 30% lower rate of cere-

brovascular accidents, although the

latter was not statistically significant.

17

In contrast, no increase in SCDs

among children, adolescents, or

young adults was observed in a sec-

ond cohort study conducted in the

General Practice Research Database.

18

Inconclusion, inthis cohort of young

and middle-aged adults, current or new

use of ADHD medications identified

from filled prescriptions, compared

with nonuse or remote use, was not as-

sociated with an increased risk of seri-

ous cardiovascular events. A modestly

elevated risk cannot be ruled out, given

limited power and a lack of complete

information on some potentially im-

portant risk factors and other factors re-

lated to use of these medications.

Published Online: December 12, 2011. doi:10.1001

/jama.2011.1830

Author Contributions: Dr Habel had full access to all

of the data in the study and takes responsibility for

the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data

analysis.

Study concept and design: Habel, Cooper, Sox, Chan,

Fireman, Cheetham, Ray, Selby.

Acquisition of data: Habel, Cooper, Sox, Chan,

Cheetham, Quinn, Dublin, Boudreau, Andrade,

Pawloski, Raebel, Smith, Uratsu, Selby.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Habel, Cooper,

Sox, Chan, Fireman, Arbogast, Cheetham, Quinn,

Achacoso, Uratsu, Go, Sidney, Nguyen-Huynh, Ray,

Selby.

Drafting of the manuscript: Habel.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important in-

tellectual content: Cooper, Sox, Chan, Fireman,

Arbogast, Cheetham, Quinn, Dublin, Boudreau,

Andrade, Pawloski, Raebel, Smith, Achacoso, Uratsu,

Go, Sidney, Nguyen-Huynh, Ray, Selby.

Statistical analysis: Cooper, Fireman, Arbogast,

Achacoso, Uratsu.

Obtained funding: Habel, Cooper, Chan, Quinn, Selby.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Chan,

Quinn, Andrade, Achacoso, Uratsu, Selby.

Study supervision: Habel, Cooper, Sox, Chan, Quinn,

Andrade, Smith.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have com-

pleted and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure

of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Dr Habel reported

receiving grants fromMerck for a study of herpes zos-

Figure 2. Subgroup Analyses for Combined End Point (Myocardial Infarction, Sudden Cardiac

Death, or Stroke), Use vs Nonuse of ADHD Medications

Lower Risk Higher Risk

0.2 5.0 1.0

Rate Ratio (95% CI)

No. of

Events

Subgroup and ADHD

Medication Use Person-Years

Rate Ratio

(95% CI)

Cohort

Full

234 Current use 107 322.4 0.83 (0.72-0.95)

489 Past use 165 319.4 0.85 (0.77-0.95)

1391 Nonuse 533 540.4 1 [Reference]

New-user

125 Current use 52 094.6 0.77 (0.63-0.94)

376 Past use 116 918.7 0.85 (0.75-0.98)

957 Nonuse 317 514.4 1 [Reference]

0.2 5.0 1.0

Rate Ratio (95% CI)

No

History of CVD

79 Current use 70 748.1 0.79 (0.62-1.00)

148 Past use 106 497.1 0.79 (0.65-0.95)

562 Nonuse 391 881.9 1 [Reference]

Yes

155 Current use 36 574.2 0.87 (0.73-1.03)

341 Past use 58 822.3 0.89 (0.79-1.01)

829 Nonuse 141 658.5 1 [Reference]

0.2 5.0 1.0

Rate Ratio (95% CI)

25-44

Age, y

47 Current use 54 106.9 0.78 (0.57-1.06)

102 Past use 85 786.7 0.79 (0.63-1.00)

250 Nonuse 271 667.1 1 [Reference]

45-64

187 Current use 53 215.5 0.83 (0.71-0.97)

387 Past use 79 532.7 0.86 (0.76-0.97)

1141 Nonuse 261 873.3 1 [Reference]

0.2 5.0 1.0

Rate Ratio (95% CI)

Yes

57 Current use 37 564.9 0.76 (0.57-1.01)

55 Past use 34 264.7 0.79 (0.59-1.05)

283 Nonuse 152 357.3 1 [Reference]

No

ADHD diagnosis

177 Current use 69 757.4 0.86 (0.74-1.01)

434 Past use 131 054.7 0.87 (0.78-0.97)

1113 Nonuse 385 962.7 1 [Reference]

0.2 5.0 1.0

Rate Ratio (95% CI)

Yes

191 Current use 78 966.8 0.87 (0.73-1.03)

386 Past use 115 995.3 0.88 (0.77-1.01)

507 Nonuse 125 558.9 1 [Reference]

No

Non-ADHD psychiatric conditions

43 Current use 28 355.6 0.76 (0.56-1.04)

103 Past use 49 324.2 0.82 (0.67-1.01)

884 Nonuse 407 981.5 1 [Reference]

Rate ratios are adjusted for site, age, sex, calendar year, and cardiovascular risk score (some variables within

score are time varying), except for newusers (adjusted for propensity score). ADHDindicates attention-deficit/

hyperactivity disorder; CVD, cardiovascular disease.

ADHD MEDICATIONS AND CV EVENTS IN YOUNGER ADULTS

E10 JAMA, Published online December 12, 2011 2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

by guest on December 14, 2011 jama.ama-assn.org Downloaded from

ter in patients with cancer, from Takeda for a study

of pioglitazone and cancer, and from sanofi-aventis

for a study of insulin and cancer. Dr Chan reported

receiving support for travel to meetings for the pur-

pose of the study or other purposes fromthe US Food

and Drug Administration (FDA) and that he is a part-

time employee of OptumInsight, a for-profit com-

pany that receives fundingfrommedical product manu-

facturers to provide consultation and conduct research

on medical products; because OptumInsight is a part

of UnitedHealthGroup, Dr Chan has received Unit-

edHealthGroup stock options. Dr Dublin reported re-

ceiving a Merck/American Geriatrics Society NewIn-

vestigator Award (honorarium paid directly to Dr

Dublin) for unrelated work. Dr Andrade reported that

the Meyers Primary Care Institute has received fund-

ing from GlaxoSmithKline and Novartis Pharmaceu-

ticals, manufacturers of medications used to treat

ADHD. Dr Smith reported that the Center for Health

Research received funding from Abbott Laboratories

to conduct a natural history study of patients with

chronic kidney disease and from GlaxoSmithKline to

study the burden of diabetes. Dr Sidney reported re-

ceiving grants or grants pending from the National

Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Insti-

tute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Na-

tional Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney

Diseases, and the Thrasher Research Fund. Dr Nguyen-

Huynh reported receiving grants or grants pending

from the American Heart Association. No other au-

thors reported disclosures.

Funding/Support: This project was funded in part un-

der contract numbers HHSA290-2005-0042 (Van-

derbilt) and HHSA290-2005-0033 (Harvard Pilgrim

Health Care Institute) from the Agency for Health-

care Research and Quality (AHRQ), US Department

of Health and Human Services, as part of the Devel-

oping Evidence to Inform Decisions about Effective-

ness (DEcIDE) program. The project was also funded

by the FDA under contracts 223-2005-10012 (Kai-

ser Permanente Northern California), 223-2005-

10100C(Vanderbilt), 223-2005-20006C(Ingenix), and

223-2005-10012C (Harvard Pilgrim Health Care In-

stitute). The project was also funded by the National

Institute on Aging under contract K23AG028954

(Group Health Research Institute).

Role of the Sponsors: Individuals fromthe AHRQand

FDA were on the study Steering Committee and pro-

vided input into the study design and conduct of the

study and interpretation of the data. The AHRQ and

FDA had no role in the preparation, review, or ap-

proval of the manuscript.

Disclaimer: The authors of this article are responsible

for its content. Statements in the article should not be

construed as endorsement by the AHRQor the US De-

partment of Health and Human Services.

Online-Only Material: The eMethods and eTables

1-12 are available at http://www.jama.com.

Additional Contributions: We acknowledge and thank

the following individuals for their contributions to this

project: Andrew Mosholder, MD (FDA), member of

Scientific Steering Committee; James Daugherty, MS,

and Judith Dudley, BS (Vanderbilt University School

of Medicine), programming; Chantal Avila, MA (Kai-

ser Permanente Southern California), project man-

agement; Yan Luo, PhD, and Wansu Chen, MS (Kai-

ser Permanente Southern California), programming;

Mary Kershner, BSN (Kaiser Permanente Colorado),

chart reviews and abstraction; April Duddy, MS (Har-

vard Pilgrim Health Care Institute), project manage-

ment; Luana Acton, BS, Julie Munneke, BA, and Heidi

Krause, BA (Kaiser Permanente Northern California),

project management; and Jean Lee, BA, and Monica

Highbaugh, AA (Kaiser Permanente Northern Cali-

fornia), medical record retrieval and abstraction. All

individuals acknowledged were compensated for their

time.

REFERENCES

1. NewReport: Americas State of Mind. Medco Web

site. http://medco.mediaroom.com/. 2011. Accessed

November 16, 2011.

2. Food and Drug Administration. Drug Safety

and Risk Management Advisory Committee meeting.

http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/cder06

.html#DrugSafetyRiskMgmt. Food and Drug Adminis-

tration Web site. February 9-10, 2006. Accessed No-

vember 21, 2011.

3. Montejano L, Sasane R, Hodgkins P, Russo L, Huse

D. Adult ADHD: prevalence of diagnosis in a US popu-

lation with employer health insurance. Curr Med Res

Opin. 2011;27(suppl 2):5-11.

4. Wilens TE, Morrison NR, Prince J. An update on the

pharmacotherapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity dis-

order in adults. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(10):

1443-1465.

5. Challman TD, Lipsky JJ. Methylphenidate: its phar-

macology and uses. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75(7):

711-721.

6. LeddyJJ, EpsteinLH, Jaroni JL, et al. Influenceof meth-

ylphenidate on eating in obese men. Obes Res. 2004;

12(2):224-232.

7. Frierson RL, Wey JJ, Tabler JB. Psychostimulants for

depression in the medically ill. AmFamPhysician. 1991;

43(1):163-170.

8. Tharwani HM, Yerramsetty P, Mannelli P, Patkar A,

Masand P. Recent advances in poststroke depression.

Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2007;9(3):225-231.

9. Warden DL, Gordon B, McAllister TW, et al; Neu-

robehavioral Guidelines Working Group. Guidelines for

the pharmacologic treatment of neurobehavioral se-

quelae of traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2006;

23(10):1468-1501.

10. Hammerness PG, Surman CB, Chilton A. Adult at-

tention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder treatment andcar-

diovascular implications. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2011;

13(5):357-363.

11. Stiefel G, BesagFM. Cardiovascular effects of meth-

ylphenidate, amphetamines and atomoxetine in the

treatment of attention-deficit hyperactivitydisorder. Drug

Saf. 2010;33(10):821-842.

12. Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins

R; Prospective Studies Collaboration. Age-specific rel-

evance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a

meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults

in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360(9349):

1903-1913.

13. Gould MS, Walsh BT, Munfakh JL, et al. Sudden

death and use of stimulant medications in youths. Am

J Psychiatry. 2009;166(9):992-1001.

14. Winterstein AG, Gerhard T, Shuster J, Johnson M,

Zito JM, Saidi A. Cardiac safety of central nervous sys-

temstimulants inchildrenandadolescents withattention-

deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2007;120

(6):e1494-e1501.

15. Schelleman H, Bilker WB, Strom BL, et al. Cardio-

vascular events and death in children exposed and un-

exposed to ADHD agents. Pediatrics. 2011;127

(6):1102-1110.

16. Winterstein AG, Gerhard T, Shuster J, Saidi A. Car-

diac safetyof methylphenidateversus amphetaminesalts

in the treatment of ADHD. Pediatrics. 2009;124

(1):e75-e80.

17. Holick CN, Turnbull BR, Jones ME, Chaudhry S,

Bangs ME, Seeger JD. Atomoxetine and cerebrovascu-

lar outcomes in adults. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;

29(5):453-460.

18. McCarthy S, Cranswick N, Potts L, Taylor E, Wong

IC. Mortality associated with attention-deficit hyperac-

tivity disorder (ADHD) drug treatment: a retrospective

cohort study of children, adolescents and young adults

using the general practice research database. Drug Saf.

2009;32(11):1089-1096.

19. Cooper WO, Habel LA, Sox CM, et al. ADHDdrugs

and serious cardiovascular events in children and

young adults. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(20):1896-

1904.

20. Alpert JS, Thygesen K, Antman E, Bassand JP. Myo-

cardial infarction redefineda consensus document of

The Joint EuropeanSociety of Cardiology/AmericanCol-

lege of Cardiology Committee for the redefinition of

myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;36

(3):959-969.

21. Meier MA, Al-Badr WH, Cooper JV, et al. The new

definition of myocardial infarction: diagnostic and prog-

nostic implications in patients with acute coronary

syndromes. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(14):1585-

1589.

22. Chung CP, Murray KT, Stein CM, Hall K, Ray WA.

A computer case definition for sudden cardiac death.

Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(6):563-572.

23. Miettinen OS. Stratification by a multivariate con-

founder score. Am J Epidemiol. 1976;104(6):609-

620.

24. Arbogast PG, Ray WA. Use of disease risk scores

in pharmacoepidemiologic studies. Stat Methods Med

Res. 2009;18(1):67-80.

25. Glynn RJ, Schneeweiss S, Stu rmer T. Indications for

propensi ty scores and revi ew of thei r use i n

pharmacoepidemiology. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol.

2006;98(3):253-259.

26. Suissa S, Edwardes MD. Adjusted odds ratios for

case-control studies with missing confounder data in

controls. Epidemiology. 1997;8(3):275-280.

27. Schneeweiss S. Sensitivity analysis and external ad-

justment for unmeasured confounders in epidemio-

logic database studies of therapeutics. Pharmacoepi-

demiol Drug Saf. 2006;15(5):291-303.

28. Schneeweiss S, GlynnRJ, Tsai EH, AvornJ, Solomon

DH. Adjusting for unmeasured confounders in phar-

macoepidemiologic claims data using external informa-

tion: the example of COX2 inhibitors and myocardial

infarction. Epidemiology. 2005;16(1):17-24.

29. Ray WA. Evaluating medication effects outside of

clinical trials: new-user designs. AmJ Epidemiol. 2003;

158(9):915-920.

30. West SL, StromBL, Polle C. Validity of pharmaco-

epidemiologic drug and diagnosis data. In: Strom BL,

ed. Pharmacoepidemiology. Philadelphia, PA: John Wi-

ley & Sons Ltd; 2005:709-765.

31. de Burgos-Lunar C, Sal i nero-Fort MA,

Ca rdenas-ValladolidJ, et al. Validationof diabetes melli-

tus and hypertension diagnosis in computerized medi-

cal records in primary health care. BMC Med Res

Methodol. 2011;11:146.

32. Thygesen SK, Christiansen CF, Christensen S, Lash

TL, Srensen HT. The predictive value of ICD-10 diag-

nostic coding used to assess Charlson comorbidity in-

dex conditions in the population-based Danish Na-

tional Registry of Patients. BMC Med Res Methodol.

2011;11:83.

33. Grijalva CG, Chung CP, Stein CM, et al. Comput-

erized definitions showed high positive predictive val-

ues for identifying hospitalizations for congestive heart

failure andselectedinfections inMedicaidenrollees with

rheumatoidarthritis. Pharmacoepidemiol DrugSaf. 2008;

17(9):890-895.

34. Adler LA, ZimmermanB, Starr HL, et al. Efficacy and

safety of OROS methylphenidate in adults with

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized,

placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel group, dose-

escalation study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;

29(3):239-247.

35. PetersonK, McDonaghMS, FuR. Comparativeben-

efits andharms of competingmedications for adults with

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systematic re-

view and indirect comparison meta-analysis. Psycho-

pharmacology (Berl). 2008;197(1):1-11.

36. Cohen AL, Jhung MA, Budnitz DS. Stimulant medi-

cations and attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder.

N Engl J Med. 2006;354(21):2294-2295.

ADHD MEDICATIONS AND CV EVENTS IN YOUNGER ADULTS

2011 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. JAMA, Published online December 12, 2011 E11

by guest on December 14, 2011 jama.ama-assn.org Downloaded from

You might also like

- 18 Gut Brain and Pandas PansDocument76 pages18 Gut Brain and Pandas Panslv499446100% (1)

- MTHFR MutationDocument1 pageMTHFR MutationRobin KallisNo ratings yet

- Ospolot 200 MG, Film-Coated Tablets: Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)Document7 pagesOspolot 200 MG, Film-Coated Tablets: Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)ddandan_2No ratings yet

- Battleground Shmuel KatzDocument167 pagesBattleground Shmuel KatzGary KatzNo ratings yet

- ACPA Chronic PainDocument126 pagesACPA Chronic PainFyan FiradyNo ratings yet

- Company ProfileDocument6 pagesCompany ProfileAhmed Eljenan100% (1)

- Law and Ethics ExamDocument22 pagesLaw and Ethics ExamMan Dip100% (1)

- Erectile Dysfunction and Comorbid Diseases, Androgen Deficiency, and Diminished Libido in MenDocument7 pagesErectile Dysfunction and Comorbid Diseases, Androgen Deficiency, and Diminished Libido in MenAfif Al FatihNo ratings yet

- Adverse Effects of FluoroquinolonesDocument10 pagesAdverse Effects of FluoroquinolonesAvelox FloxNo ratings yet

- Food For Mood: 1. Foods Rich in Omega-3 Fatty AcidsDocument7 pagesFood For Mood: 1. Foods Rich in Omega-3 Fatty AcidsakankshaNo ratings yet

- Articles On Wheat ToxicityDocument96 pagesArticles On Wheat ToxicityDr. Heath Motley100% (1)

- Repositioning of Anthelmintic Drugs For The Treatment of Cancers of The Digestive SystemDocument18 pagesRepositioning of Anthelmintic Drugs For The Treatment of Cancers of The Digestive SystemMishael PeterNo ratings yet

- Aditivos Alimentarios PDFDocument38 pagesAditivos Alimentarios PDFANTHONY FARID CABEZAS GUEVARANo ratings yet

- Health Psychology Assignment (MA201477)Document7 pagesHealth Psychology Assignment (MA201477)Syeda DaniaNo ratings yet

- Contemporary and Integrative MedicineDocument10 pagesContemporary and Integrative Medicineapi-649875164No ratings yet

- Day 3Document3 pagesDay 3Karl JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Hereditary HemochromatosisDocument6 pagesHereditary HemochromatosisVijeyachandhar DorairajNo ratings yet

- Defiency Chart and SurveyDocument2 pagesDefiency Chart and Surveyapi-232967376No ratings yet

- Start Low and Go Slow 1-21-2014Document5 pagesStart Low and Go Slow 1-21-2014Ed JonesNo ratings yet

- Vivitrol TreatmentDocument8 pagesVivitrol TreatmentHarish RathodNo ratings yet

- Mcs Under SiegeDocument16 pagesMcs Under Siegeapi-269724919No ratings yet

- An Update On Menopause ManagementDocument10 pagesAn Update On Menopause ManagementJuan FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Ophthalmologic Concerns With Alternative Medicinal TherapiesDocument26 pagesOphthalmologic Concerns With Alternative Medicinal TherapiesBaharudin Yusuf Ramadhani100% (1)

- Mind Body Medicine Mind Body Medicine MiDocument14 pagesMind Body Medicine Mind Body Medicine MiMotea IoanaNo ratings yet

- Alcoholic Liver DiseaseDocument8 pagesAlcoholic Liver DiseaseCassandra ZubeheourNo ratings yet

- Parasite Herbal RemediesDocument10 pagesParasite Herbal Remediesdonaldbrown16No ratings yet

- Magnesium Is Critical For: Balancing Blood Sugar LevelsDocument1 pageMagnesium Is Critical For: Balancing Blood Sugar LevelsmajikNo ratings yet

- The ADAPT Functional Medicine Practitioner Training Program Course GuideDocument18 pagesThe ADAPT Functional Medicine Practitioner Training Program Course Guideerica100% (1)

- Nutritional Psychiatry - Your Brain On Food - Harvard Health Blog - Harvard Health PublishingDocument9 pagesNutritional Psychiatry - Your Brain On Food - Harvard Health Blog - Harvard Health PublishingAna Rica Santiago Navarra-CruzNo ratings yet

- The Rold of Fodmap Diet in IbsDocument4 pagesThe Rold of Fodmap Diet in Ibsapi-236139728No ratings yet

- Elimination Diet Weekly Planner Metricized Sample MenuDocument44 pagesElimination Diet Weekly Planner Metricized Sample MenuAmanda JimenezNo ratings yet

- Vitamin B2Document2 pagesVitamin B2sbornicul100% (1)

- Nutrition Low Purine DietDocument4 pagesNutrition Low Purine DietHuan XinchongNo ratings yet

- Is Diet Important in Bipolar Disorder?Document13 pagesIs Diet Important in Bipolar Disorder?Giovane de PaulaNo ratings yet

- THE INTEGRATIVE MedicineDocument23 pagesTHE INTEGRATIVE MedicineBaihaqi SaharunNo ratings yet

- Alcoholism and Psychiatric - Diagnostic Challenges PDFDocument9 pagesAlcoholism and Psychiatric - Diagnostic Challenges PDFmirtaNo ratings yet

- The 3 Most Important Types of Omega-3 Fatty AcidsDocument168 pagesThe 3 Most Important Types of Omega-3 Fatty AcidsAndreea DumitrescuNo ratings yet

- Itamin Hart: No ToxicityDocument4 pagesItamin Hart: No ToxicityAnonymous Sfcml4GvZNo ratings yet

- Antidepressant Switching TableDocument1 pageAntidepressant Switching TableSimone BelfioriNo ratings yet

- Antiprotozoal Agents: PHR SangitaDocument21 pagesAntiprotozoal Agents: PHR SangitaCurex QANo ratings yet

- Collagen (Protein) PeptideDocument7 pagesCollagen (Protein) PeptideDexter OcsanNo ratings yet

- Hypnotics Anxiolytics GuidelinesDocument28 pagesHypnotics Anxiolytics GuidelinesClarissa YudakusumaNo ratings yet

- Lugol and GraveDocument6 pagesLugol and GraveSeptiandry Ade Putra100% (2)