In This Issue: Child Development, July/August 2014, Volume 85, Number 4, Pages 1323 - 1329

In This Issue: Child Development, July/August 2014, Volume 85, Number 4, Pages 1323 - 1329

Uploaded by

hirsi200518Copyright:

Available Formats

In This Issue: Child Development, July/August 2014, Volume 85, Number 4, Pages 1323 - 1329

In This Issue: Child Development, July/August 2014, Volume 85, Number 4, Pages 1323 - 1329

Uploaded by

hirsi200518Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

In This Issue: Child Development, July/August 2014, Volume 85, Number 4, Pages 1323 - 1329

In This Issue: Child Development, July/August 2014, Volume 85, Number 4, Pages 1323 - 1329

Uploaded by

hirsi200518Copyright:

Available Formats

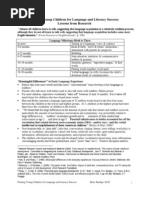

In This Issue

Language Development

Before they begin talking, infants have already

begun learning about the language or languages

surrounding them. For example, by 4 months, most

infants have learned their own name, and prefer lis-

tening to a passage containing it than a passage

that doesnt mention it. And research suggests that

individual infants performance in such speechper-

ception tasks may predict their language in the sec-

ond year and beyond. Cristia, Seidl, Junge,

Soderstrom, and Hagoort (p. 1330) evaluated the

strengths and weaknesses of this notion by review-

ing studies to nd that infants perception of speech

predicted the size of their vocabularies signicantly,

with correlations of similar strength to those found

for other traditional infant predictors. The results

have implications for parents and teachers, as well

as for efforts to identify delays and intervene in the

case of problems such as speechlanguage delays,

disorders, and impairments.

Core language skills are stable from early child-

hood to adolescence, with stability stronger from 4 to

10 to 14 years than from 20 months to 4 years,

according to Bornstein, Hahn, Putnick, and Suwal-

sky (p. 1346). Their longitudinal study evaluated sta-

bility of language in about 325 children from early

childhood to adolescence. Stability measures consis-

tency in individual differences over time, so that chil-

dren who show a high level of language at one point

compared to their peers continue to show high levels

later, while other children show low levels across

time. In this study, stability didnt differ between

girls and boys. By assessing multiple domains of lan-

guage using age-appropriate measures and many

sources to evaluate how different measures go

together at each of several ages across childhood, the

study can inform early intervention programs at ages

when theyre likely to be most effective.

The way words sound, or their covers, and the

contexts in which they occur in sentences, or the

company they keep, provide probable cues to their

semantic properties, or what they mean: Nouns

tend to end in y and occur after a and the

(Look, its a kitty!), especially in speech to babies.

Tracking these kinds of cues is referred to as statis-

tical learning and may be central to infants lan-

guage development. For example, many laboratory

studies suggest that infants can learn highly reliable

statistical patterns. These patterns are much more

imperfect in natural languages, raising questions

about whether infants statistical learning abilities

are truly relevant to their language development.

However, Lany (p. 1727), in her study of 40 primar-

ily White, middle- to upper-middle-class 22-month-

olds, nds that infants can learn probable statistical

regularities, and that this ability is connected to

their ability to learn language in the real world.

Do visual and/or auditory problems contribute

to developmental dyslexia (a specic reading dis-

ability)? Steinbrink, Zimmer, Lachmann, Dirichs,

and Kammer (p. 1711) studied about 240 German

elementary school children over the course of rst

and second grade to nd out. Childrens ability to

rapidly process visual information wasnt associ-

ated with reading and spelling performance, but

their ability to do rapid auditory processing did

predict how well they did on reading and spelling

at the end of the year. Because auditory processing

abilities assessed shortly after they started school

were related to their reading and spelling abilities

later on, the study concludes that rapid auditory

processing contributes to later literacy development.

It also suggests that performance on rapid auditory

processing tasks might provide for early identica-

tion or diagnosis of children at risk for dyslexia.

Ethnic-Minority Teen Moms

Teen moms are more likely to suffer lower self-

esteem and have more symptoms of depression

than adult moms. An important part of positive

development for ethnic-minority teens involves

their feelings about their ethnicity: Latino teens

who afrm their ethnic identity tend to feel better

about themselves. Derlan et al. (p. 1357) examined

factors that affect youths positive feelings toward

ethnicity over time among more than 200 Mexican-

origin teen mothers, focusing on whether teens

perceptions of experiencing discrimination and their

connection to the mainstream U.S. culture affected

their feelings about their ethnic group a year later.

2014 The Author

Child Development 2014 Society for Research in Child Development, Inc.

All rights reserved. 0009-3920/2014/8504-0001

DOI: 10.1111/cdev.12276

Child Development, July/August 2014, Volume 85, Number 4, Pages 13231329

Findings: Teen moms who said they were very con-

nected to mainstream U.S. culture had fewer posi-

tive feelings toward their ethnic group when they

perceived experiencing discrimination for being

Mexican. Teens positive feelings toward their eth-

nicity werent harmed by their perceptions of dis-

crimination if they said they didnt feel strongly

connected to mainstream U.S. culture. The ndings

suggest that perceived ethnic discrimination poses a

signicant risk for Mexican-origin adolescent moms

who are very involved in Anglo cultures; as such,

they have important implications for interventions.

Gender Bias

Elementary school children know who their own

friends are and they think they know who other chil-

drens friends are. But they overestimate the impor-

tance of gender in decisions about who is friends

with whom, especially among older children, nd

Neal, Neal, and Cappella (p. 1366). A pair of children

is nine times more likely to be friends if they share the

same gender, but a child is more than 50 times more

likely to believe two classmates are friends when they

are the same gender. The degree to which childrens

inferences about friendships overestimate the impor-

tance of gender is even stronger for older children.

Thus, while gender matters a lot in howchildren form

friendships, children think it is almost the only rele-

vant factor. This study looked at classroom relation-

ships among about 425 low-income, African

American second through fourth graders.

Cue Attraction

Children as young as 3 typically think more posi-

tively about peers who are attractive, the same gen-

der as they are, or of the predominant race. Rennels

and Langlois (p. 1401) nd that for many children,

especially in middle childhood, attractiveness is as

strong a cue, if not a stronger one, than gender or

race in terms of qualities that children use to discrim-

inate others. Their study investigated social biases

across domains in about 100 children aged 311 from

a variety of racial backgrounds. The ndings can

inform interventions and antidiscrimination policies.

Getting a Head Start

One year of Head Start can make a big difference

for children from homes where parents provide less

early academic stimulation, such as reading to chil-

dren, helping them recognize and pronounce letters

and words, and helping them count, according to

Miller, Farkas, Vandell, and Duncan (p. 1385).

Their study also nds that showing parents how

they can assist their children with reading and

counting may help, too. The research team ana-

lyzed data from the Head Start Impact Study, a

nationally representative sample of nearly 5,000

newly entering, eligible 3- and 4-year-olds. The

results suggest that its particularly important that

Head Start be offered to those children whose par-

ents dont report providing high levels of pre-

academic stimulation.

Science and Gender

Gender differences persist in some areas of science

performance and in youths choice of science-

related careers. Studies suggest that spatial skills

the ability to generate and manipulate mental

representations of objectsmay play a role. Gan-

ley, Vasilyeva, and Dulaney (p. 1419) carried out

two studies: In one, researchers gave more than 110

primarily White, middle-class eighth graders a spa-

tial skills test to measure their ability to mentally

rotate, then looked at the students scores on the

science part of a standardized test. They then ana-

lyzed the relation between gender and performance.

In the other study, they examined the performance

of more than 73,240 eighth graders on a state sci-

ence test to determine (based on the ndings of the

rst study) whether questions involving spatial

skills were more likely to show gender differences.

Across both studies, they nd that gender differ-

ences in students spatial skills can help explain

gender differences in students scores on science

tests. This is important because spatial skills can be

improved through training; in particular, such skills

can be taught at young ages using simple materials

such as building with blocks and doing puzzles.

Parents Contributions to Childrens

Cognitive Skills

Working memorythe ability to hold information

in your mind, think about it, and use it to guide

behaviordevelops through adolescence and is key

for successful performance at school and work.

Children from low-income families have been

found to perform worse on tests of working mem-

ory than their peers from better-off families.

1324 In This Issue

Hackman et al. (p. 1433) nd that differences in

working memory that exist at age 10 persist

through the end of adolescence. They also nd that

parents educationone common measure of socio-

economic status (SES)is related to childrens per-

formance on tasks of working memory, and that

neighborhood characteristicsanother common

measure of SESare not. The study looked at more

than 300 children aged 1013 over 4 years. Under-

standing how disparities in working memory

develop has implications for education, and this

study highlights the value of programs that pro-

mote developing working memory early as a way

to prevent disparities in achievement.

An important human characteristic is the ability

to plan rather than respond to an immediate situa-

tion without deliberation. In their longitudinal

study, Friedman et al. (p. 1446) took a broad, inte-

grative look at the development of planning in mid-

dle childhood, studying more than 1,300 children

and their families who were part of the NICHD

Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development.

The children, from preschool through fth grade,

represented a range of racial, ethnic, and socioeco-

nomic backgrounds. The study nds that mothers

education (measured when the children were 1

month old), through its effect on parenting quality

when children were 4, predicted how children did

on tests of memory, attention, and inhibition. This

performance, in turn, predicted childrens planning

skills in rst grade, which predicted their achieve-

ment in reading and math in third grade. It also

nds this path when the same parenting, cognitive,

and academic constructs were measured at later

time points.

Math Skills

Does childrens understanding of fractions build on

earlier forms of mathematical learning, or does the

conceptual leap from whole numbers to fractions

rely predominantly on nonmathematical cognitive

competencies? In their longitudinal study of more

than 160 mostly low-income children from rst

through fourth grades and a variety of racial and

ethnic backgrounds, Vukovic et al. (p. 1461) sought

to unravel the developmental course of fraction

learning. They nd that nonmathematical compe-

tencies were associated with learning whole-num-

ber arithmetic and number line skills, but not

fractions. Also, fraction knowledge has roots in ear-

lier forms of math learning and in early number

knowledge. Together, the ndings indicate that

learning fractions is an extension of earlier math

learning, with nonmath competencies playing a

supportive role. The results suggest children learn

fractions via the same pathway as whole-number

development, a proportional reasoning learning tra-

jectory, or a yet unspecied developmental course

beginning from their early knowledge of numbers.

But they also suggest that learning fractions

requires a particularly tailored type of instruction.

Shortly after learning to count, children learn to

estimatethey attach words like twenty and a thou-

sand to numerical quantities, and do so even with-

out counting all the things being labeled (such as

when they guess how many people are at a party).

We know that children get better at estimating as

they get older, and that being a good estimator is

related to academic successbut we dont know

why. In their study of 60 primarily White, upper-

middle-class 5- to 7-year-olds, Sullivan and Barner

(p. 1740) sought to determine which learning mecha-

nisms children use to attach number words to the

numerical quantities these words represent. Counter

to some prevailing theories of estimation, they nd

that childrens estimation skill wasnt based on their

experience with specic wordmagnitude pairings

(such as hearing the word twelve refer to 12 bagels,

12 students, and 12 pencils). Instead, children used

the structure of the count list (e.g., that 12 is half as

large as 24 and twice as big as 6) to guide their use

of number language to represent numerical quan-

tity. The ndings provide new information about

how children attach language to perception, an

important topic for psychologists, educators, and

policymakers.

Thanks for the Memories

Infants are limited in how many hidden objects

they can remember at a time, but like adults, they

can overcome this limit by chunking items into

sets (much like adults chunk phone numbers into

groups of digits, rather than remembering a single

string of 10 digits). Stahl and Feigenson (p. 1477)

nd that infants can use their knowledge of the

social world to help them chunk objectsfor exam-

ple, a pair of dolls positioned to face each other that

interact with one anotherusing social cues to

expand memory beyond its usual limits. They stud-

ied about 50 primarily White, middle-class 15- to

17-month-olds.

People remember objects when they appear in

the same context in which they were originally

encounteredwhen you see someone from work at

In This Issue 1325

the grocery store, it may take a minute to recognize

her (a memory error). Do both infants and adults

show context effects, given that brain structures

supporting these effects develop into adolescence?

Edgin, Span o, Kawa, and Nadel (p. 1491) exam-

ined the development of these effects in children

from age 3 into adulthood, and in individuals with

Down syndrome (a total of about 110 individuals).

They nd evidence for context effects even in very

young children (3-year-olds) and in children with

Down syndrome, which suggests that context

effects exist at early ages and in individuals with

memory impairment. In typically developing chil-

dren, these effects seem to disappear after age 4,

then reappear later in life, when they are 10

16 years old. The ndings tell us that development

matters when assessing these complex memory

effects, and they suggest that context effects might

be mediated by different brain systems over the life

span.

From Where I Stand

Everyone believes that infants learn a lot from what

they see, but little is known about what infants see

and how visual input changes over development.

Kretch, Franchak, and Adolph (p. 1503) used head-

mounted eye trackers and motion-tracking sensors

to investigate the visual input of forty 13-month-old

crawlers and walkers. They nd that infants view

of the world changes with the developmental tran-

sition from crawling on all fours to walking

upright. While crawling, infants see mostly the oor

in front of their hands. But when they stand up,

their increased height and greater range of head

motion allow them to see more of the wider envi-

ronment, including their caregivers faces and

objects in the distance. By revealing that infants

visual experiences are intimately tied to their pos-

ture, the study deepens our understanding of learn-

ing and development in infancy.

Theory of Mind

Everyday mind reading or theory-of-mind ability

typically benchmarked through false-belief tasks

helps us appreciate that peoples interpretations of

reality are formed and constrained by particular

experiences of the world. Low, Drummond,

Walmsley, and Wang (p. 1519) nd that measures

of childrens and adults eye gaze appeared to tap

an implicit understanding of false beliefs in simple

contexts (beliefs about where an object is located)

but not more complex contexts (beliefs about how

an object or situation might be regarded). In con-

trast, as measured by more explicit verbal methods,

with age, children and adults were able to exibly

predict other peoples belief-based actions across

different contexts. The study, of almost a hundred

3- to 4-year-olds and more than 30 adults, most of

European descent, suggests that early in develop-

ment, an implicit, automatic system is in place that

efciently tracks the mental states of others in

limited contexts, but only later is a more exible

system in place for more generally making sense of

the complex and varied business of other peoples

minds.

Around ages 4 to 5, children realize that unob-

servable mental states, such as thoughts, beliefs,

and emotions, underlie much of human behavior,

an achievement referred to as theory of mind. Part

of theory of mind is understanding that minds rep-

resent reality, such that actions are based on what

we think is true, rather than whats actually true. In

their longitudinal study, Lillard and Kavanaugh (p.

1535) examined the extent to which various sym-

bolic skills that emerge in the years just prior to

ages 4 and 5pretend play, language, and under-

standing representationsmight undergird theory

of mind. About 60 children, most of them White,

were tested from ages 2 and a half to 4 years on

symbolic precursor skills, and were given theory of

mind tests at ages 4 and 5. A subset of the symbolic

variables was signicantly related to theory of mind

at ages 4 and 5, providing the best evidence to date

that theory of mind is undergirded by a symbolic

element that also supports language, pretend play,

and representational understanding.

Literacy and Language Immersion

Parents of children in early elementary school are

encouraged to help them acquire literacy skills at

home, but parents whose children are in language

immersion programs are faced with a dilemma

should they provide home literacy activities in the

language learned at school even though they may

have minimal knowledge of that language, or

should they provide home literacy activities in Eng-

lish? In their longitudinal work (children were

followed from kindergarten to second grade),

Senechal and LeFevre (p. 1552) tested whether 100

English-speaking Canadian children learning to

read in French would show links between home

literacy experiences and later English reading skills

1326 In This Issue

when parents provided home literacy activities in

English. Findings: Parents home literacy activities

in the home language (English) were related to chil-

drens reading development (in English) even

though their schooling was primarily in French.

This suggests that parents can provide literacy

activities in their rst language at home that might

help how children learn to read in that language

even when a different language is used in school.

The Roots of Shyness

Previous studies have found that children who are

inhibited in their behaviorthose who are shy,

fearful, and withdraw from new situationstend to

have lower language abilities, but its unclear why.

Smith Watts et al. (p. 1569) examined this associa-

tion in more than 800 primarily White toddlers

(ages 14, 20, and 24 months). They nd that chil-

dren who are behaviorally inhibited tended to

speak less but their ability to understand whats

being said was not signicantly different from less

shy peers. In other words, these children had per-

formance problems when speaking with others, but

they didnt lack capability, suggesting that theyre

merely reluctant to respond rather than delayed or

decient in understanding language. They also nd

that girls were shyer and had better language abil-

ity than boys, but the degree to which shyness was

related to language development was similar for

both genders. These results indicate that inhibited

behaviors like shyness dont hamper language

acquisition, but that behaviorally inhibited children

may need support as they develop their speaking

abilities.

Another study on shyness looked at socially

wary children. These children are shy, and their

discomfort with social situations causes them to

withdraw from others and isolate themselves. Being

socially wary is thought to boost childrens risk of

developing emotional, social, and academic prob-

lems. In their longitudinal study of about 100 pri-

marily White, middle-class 2- to 4-year-olds,

Hastings, Kahle, and Nuselovici (p. 1586) nd that

socially wary preschoolers adjusted well in school,

developing good social skills and doing well aca-

demically 5 years later if they were better able to

regulate their physiological responsiveness as pre-

schoolers and had moms who werent overprotec-

tive. But preschoolers who had poor regulatory

capacity or overprotective moms (or both) had

more emotional problems and more social difcul-

ties, and did worse academically. The study can

inform intervention programs to help socially wary

children thrive.

Beliefs and Religion

How do children come to understand knowledge in

people and God? Kiessling and Perner (p. 1601)

looked at about a hundred 3- to 6-year-olds attend-

ing Catholic kindergartens in Austria, focusing on

their understanding of knowledge in different peo-

ple (mother, baby) and God. Younger children

tended to project their own knowledge or ignorance

on people as well as on God, while older children

either anthropomorphized God or, in still older

children, conceived him as knowledgeable. The

ndings challenge the developmental account that

young children are born believers. On the con-

trary, children start thinking that Gods knowledge

is as limited as peoples knowledge and only later

deem God to be omniscient. The study helps us

understand more about childrens belief systems

and how they develop.

Children and adults tend to believe that people

have certain features that are immortal and that

they transcend death and persist forever in some

mental form. Emmons and Kelemen (p. 1617)

explored where that belief originates by examining

almost 300 Ecuadorian 5- to 12-year-olds beliefs

about their mental and bodily capacities prior to

conception, that is, before life. Both urban and rural

indigenous children tended to treat their emotions

and desires as having always existed, even before

they were conceived and independent of their phys-

ical existence. The ndings suggest that from early

in development, children nd it hard to suppress

the idea that people exist in some mental form, and

that beliefs about personal immortality come from

an unlearned and potentially universal psychologi-

cal tendency.

Religious adolescents tend to have fewer prob-

lem behaviors (smoking, stealing, truancy) and to

develop friendships with other peers who are reli-

gious. French, Christ, Lu, and Purwono (p. 1634)

sought to determine how changes in teens religios-

ity over adolescence affected their behavior or their

friendships. Based on their longitudinal study of

about 560 Indonesian Muslim 15-year-olds (a group

thats religiously homogeneous and very religious),

they nd that changes over time in teens religiosity

closely mapped changes in their friends religiosity.

Over the 2-year study, teens religiosity changed

rst and their friends religiosity changed during

the subsequent year, suggesting that adolescents

In This Issue 1327

chose new friends who were similar to them.

Changes in religiosity also were associated with

changes in problem behavior: Teens who increased

in religiosity decreased their engagement in prob-

lem behavior, while teens who decreased in religi-

osity took part in more problem behavior. The

study points to the value of considering teens reli-

giosity as part of their social development.

Focus on Peers

Children perceived as popular by their classmates

arent necessarily well liked or accepted. These chil-

dren are also often arrogant, disobedient, aggres-

sive, and socially dominant. How do teachers

inuence perceived popularity and peer accep-

tance? De Laet et al. (p. 1647), in their study of

almost 600 Belgian fourth through sixth graders,

nd that teachers may increase certain students

perceived popularity by relational conict: Children

who conicted more with their teacher were seen

as more popular by classmates the next year, sug-

gesting that teachers unintentionally boost certain

childrens social standing through conict. Also,

children who were accepted by their peers seemed

to get more support from their teachers the follow-

ing year, which further increased how much their

peers accepted them. The ndings can help teachers

understand their role as social architect and can

inform interventions to promote positive relation-

ships in classrooms.

Effective communication and interpersonal inter-

actionsincluding relationships with peers of the

other genderare a key to successful personal, aca-

demic, and professional success. Yet starting in

early childhood, on average, girls and boys spend

more time with peers of their own gender, a phe-

nomenon termed gender segregation. As a conse-

quence of this time apart, males and females learn

different ways of communicating and relating to

their peers. Zosuls, Field, Martin, Andrews, and

England (p. 1663) studied about 200 fourth graders

and more than 850 seventh and eighth graders from

middle-class families and ethnically diverse back-

grounds. They nd that childrens condence in

their ability to understand and relate to other-gen-

der peers is important to forming positive, mean-

ingful relationships between girls and boys, and

breaking the gender divide.

Adolescence is a time when youth become

increasingly involved in the world beyond the fam-

ily. Yet, whether time spent with peers is a benet

for adolescents well-being remains a question. In

their study of children in about 200 White, middle-

class families that spanned 8 years (children were

811 at the start), Lam, McHale, and Crouter (p.

1677) examined the developmental patterns and

adjustment implications of time with peers during

adolescence. Findings: Time with same-sex peers

peaked in midadolescence, but time with mixed/

opposite-sex peers, when at least one opposite-sex

peer was present, increased from early to late ado-

lescence. Time with mixed/opposite-sex peers with-

out an adult present predicted problem behaviors

and symptoms of depression a year later. Time

with mixed/opposite-sex peer groups in the pres-

ence of an adult, however, was linked to better

grades in the next year. The results underscore the

importance of adults in supervising (but not direct-

ing) youth activities.

Community Violence

Exposure to community violence is an important

risk factor for exhibiting aggression during adoles-

cence, but its only one of many factors that may

affect adolescents adjustment. In their study of

almost 1,200 high-risk sixth graders, Farrell, Mehari,

Kramer, and Goncy (p. 1694) examined the inu-

ence of concentrated disadvantagea cluster of

neighborhood factors such as poverty rate, percent-

age receiving public assistance, education level, and

resident instabilityto nd that its related to more

instances of witnessing violence and victimization,

and more engagement in physically aggressive

behavior among teens. However, more exposure to

violence didnt account for why teens in very disad-

vantaged neighborhoods were more aggressive.

Based on changes during sixth grade, the study

suggests a two-way relation between witnessing

violence and aggression: Witnessing violence

predicted increases in aggression, and frequency of

aggression predicted increases in frequency of

witnessing violence. By identifying neighborhood

and individual factors that affect teens lives, the

study can inform comprehensive prevention efforts.

Getting Sorted

Children of a certain age often have difculty exi-

bly shifting attention between different dimensions

of a task. Jowkar-Baniani and Schmuckler (p.

1373) looked at a popular measure of attention

shifting and executive function, the Dimensional

Change Card Sorting task, in which children have

1328 In This Issue

to sort stimuli depicted on cards on the basis of one

dimension (such as color), then shift to sorting the

stimuli on the basis of a different dimension (such

as shape). In particular, they looked at how changes

to irrelevant features of the cards (such as the back-

ground color or shape of the cards themselves)

affected the way 125 preschoolers sorted. Results

generally indicated that even when such irrelevant

features were changed, young childrens sorting

behavior improved, suggesting that such changes

heighten childrens attention to the overall task,

which leads to better performance. The ndings

help us understand how attention to background,

lower-level perceptual information can inuence

young childrens cognitive ability.

Child Maltreatment

Children begin to lie by age 2, and their early lies

tend to be denials of wrongdoing. Surveys of adults

consistently nd that many who were maltreated as

children never disclosed it to anyone when they

were young. Little research has explored how chil-

drens reluctance to disclose wrongdoing can be

overcome. Lyon et al. (p. 1756) found a new way

to elicit honestywhat they call a putative confes-

sion. They worked with more than 260 primarily

low-income children ages 49, half of whom had

been abused or neglected by parents (the children

were from a range of ethnic and racial back-

grounds). A friendly stranger played with each

child with a series of toys, two of which appeared

to break. The stranger expressed concern that he or

she would get in trouble for playing with the

breakable toys and asked the child to keep the

breakage a secret. An interviewer then questioned

the child about what happened, saying that the

stranger had told me everything that happened

and he wants you to tell the truth. This approach

increased childrens honesty without increasing

false reports. With further study, the approach may

prove useful in investigations of child maltreat-

ment.

Anne Bridgman

In This Issue 1329

You might also like

- ECG Interpretation Cheat SheetDocument1 pageECG Interpretation Cheat Sheethirsi20051883% (30)

- Self-Reinforcement and Self EfficacyDocument6 pagesSelf-Reinforcement and Self EfficacyMoureen NdaganoNo ratings yet

- List of MCQS EndocrineDocument40 pagesList of MCQS Endocrinehirsi200518100% (1)

- History of Present IllnessDocument10 pagesHistory of Present Illnesshirsi200518No ratings yet

- Endocrinology HandbookDocument75 pagesEndocrinology Handbookhirsi200518No ratings yet

- Rowe JCL 2008Document22 pagesRowe JCL 2008bolinha com um BNo ratings yet

- Tamis-LeMonda Rodriguez Encyclopedia Early Childhood Education 2014Document7 pagesTamis-LeMonda Rodriguez Encyclopedia Early Childhood Education 2014alphasouvNo ratings yet

- Parents and Preschool Children Interacting With Storybooks: Children's Early Literacy AchievementDocument16 pagesParents and Preschool Children Interacting With Storybooks: Children's Early Literacy AchievementNurul Syazwani AbidinNo ratings yet

- ASDC Sign Language For All-EnglishDocument28 pagesASDC Sign Language For All-EnglishAlifia Rizki100% (1)

- Bilingual in Early Literacy PDFDocument10 pagesBilingual in Early Literacy PDFsavemydaysNo ratings yet

- Pathways To Literacy: Connections Between Family Assets and Preschool Children's Emergent Literacy SkillsDocument18 pagesPathways To Literacy: Connections Between Family Assets and Preschool Children's Emergent Literacy Skillsapi-277160707No ratings yet

- Visions For Literacy: Parents' Aspirations For Reading in Children With Down SyndromeDocument8 pagesVisions For Literacy: Parents' Aspirations For Reading in Children With Down SyndromeValee ValentinaNo ratings yet

- Priming Young Children For Language and Literacy Success: Lessons From ResearchDocument4 pagesPriming Young Children For Language and Literacy Success: Lessons From ResearchAnindita PalNo ratings yet

- Infant-Language, Shyness and SocialContextDocument9 pagesInfant-Language, Shyness and SocialContextJuan Lino Fernandez GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Hablantes Tardíos (Inglés)Document20 pagesHablantes Tardíos (Inglés)Ana BenítezNo ratings yet

- Chanda Literature Review PaperDocument39 pagesChanda Literature Review Paperapi-399444494No ratings yet

- Elsevier_RelativeEfficacyOfParentAndTeacherInvolvementInASharedReadingInterventionForPreschoolChildrenFromLowIncomeBackgrounds_1998Document28 pagesElsevier_RelativeEfficacyOfParentAndTeacherInvolvementInASharedReadingInterventionForPreschoolChildrenFromLowIncomeBackgrounds_1998Dima ToubajiNo ratings yet

- Arp WalkerDocument18 pagesArp Walkerapi-521335305No ratings yet

- Ingilizce Makale Dil GelişimiDocument13 pagesIngilizce Makale Dil GelişimimuberraatekinnNo ratings yet

- Literacy LanguageDocument20 pagesLiteracy LanguageErsya MuslihNo ratings yet

- Late Talkers: A Population-Based Study of Risk Factors and School Readiness ConsequencesDocument20 pagesLate Talkers: A Population-Based Study of Risk Factors and School Readiness ConsequencesEssa BagusNo ratings yet

- The Influence of Family Factors On Children Early Literacy SkillsDocument28 pagesThe Influence of Family Factors On Children Early Literacy SkillsSalman HasibuanNo ratings yet

- Filipino Parents Used Swear Words in Household Affecting Family RelationsDocument8 pagesFilipino Parents Used Swear Words in Household Affecting Family RelationsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Researchers Discover Environment Influences Children's Ability To Form, Comprehend Complex SentencesDocument3 pagesResearchers Discover Environment Influences Children's Ability To Form, Comprehend Complex SentencesOsman MamatNo ratings yet

- AGIZero To ThreeScienceReviewSept2013 PDFDocument10 pagesAGIZero To ThreeScienceReviewSept2013 PDFMaria AparecidaNo ratings yet

- The Effects of Bilingualism On Theory of Mind DevelopmentDocument16 pagesThe Effects of Bilingualism On Theory of Mind DevelopmentRenata JurevičiūtėNo ratings yet

- Using Story Reading and Explicit Instruction in The Vocabulary Acquisition of Kindergarten ChildrenDocument17 pagesUsing Story Reading and Explicit Instruction in The Vocabulary Acquisition of Kindergarten ChildrenpyriadNo ratings yet

- ELL2-Language DevelopmentDocument16 pagesELL2-Language DevelopmentLaurensia Aptik EvAnJeliNo ratings yet

- Helpful Literacy QuotesDocument149 pagesHelpful Literacy QuotesMaria Angeline Delos SantosNo ratings yet

- Multigenerational Giftedness: Perceptions of Giftedness Across Three GenerationsDocument27 pagesMultigenerational Giftedness: Perceptions of Giftedness Across Three GenerationsBianca AxinteNo ratings yet

- 2011 L Rodríguez-Trajectories of The Home Learning Environment Across 5 Years - Child DevDocument18 pages2011 L Rodríguez-Trajectories of The Home Learning Environment Across 5 Years - Child DevDaniel Castañeda SánchezNo ratings yet

- Parental Involvement in The Development of Children's Reading Skill: A Five-Year Longitudinal StudyDocument16 pagesParental Involvement in The Development of Children's Reading Skill: A Five-Year Longitudinal StudyNurul Syazwani AbidinNo ratings yet

- Schooling Effects HearingDocument24 pagesSchooling Effects HearingIustina SolovanNo ratings yet

- Beginning Reading FinalDocument23 pagesBeginning Reading FinalVon Lloyd Ledesma LorenNo ratings yet

- Children Learn Second Languages Quickly and EasilyDocument15 pagesChildren Learn Second Languages Quickly and EasilyJohn Gerald PilarNo ratings yet

- Language Skills and Nonverbal Cognitive Processes Associated With Reading Comprehension in Deaf ChildrenDocument8 pagesLanguage Skills and Nonverbal Cognitive Processes Associated With Reading Comprehension in Deaf Childrenlope86No ratings yet

- Phonological and Phonemic AwarenessDocument11 pagesPhonological and Phonemic AwarenessMay Anne AlmarioNo ratings yet

- Assessment 1 - Uyen Nguyen - S1441456Document5 pagesAssessment 1 - Uyen Nguyen - S1441456Nguyen UyenNo ratings yet

- Precursorsof DyslexiaDocument26 pagesPrecursorsof DyslexiaiprintslNo ratings yet

- Journal of Child LanguageDocument44 pagesJournal of Child LanguageHeri Zalmes Dodge TomahawkNo ratings yet

- Derasin Final4Document23 pagesDerasin Final4Valdez FeYnNo ratings yet

- The Unique Contribution of Home Literacy Environment To Differences in Early Literacy SkillsDocument12 pagesThe Unique Contribution of Home Literacy Environment To Differences in Early Literacy SkillsmuberraatekinnNo ratings yet

- Language Intervention Research in Early Childhood Care and EducationDocument18 pagesLanguage Intervention Research in Early Childhood Care and EducationRosmery Naupari AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Nihms 429985Document17 pagesNihms 429985Aliana Gonzalez CachoNo ratings yet

- Comm CommResearchProposalDocument9 pagesComm CommResearchProposalWilhemina BrightsNo ratings yet

- Increasing The Expressive Vocabulary of Young Children Learning English As A Second Language Through Parent InvolvementDocument8 pagesIncreasing The Expressive Vocabulary of Young Children Learning English As A Second Language Through Parent InvolvementSamuel AgudeloNo ratings yet

- Readingaloudtochildren Adc July2008Document4 pagesReadingaloudtochildren Adc July2008api-249811172No ratings yet

- Assigment 1 2Document17 pagesAssigment 1 2api-291897845No ratings yet

- Early Communicative Gestures Prospectively Predict Language DevelopmentDocument17 pagesEarly Communicative Gestures Prospectively Predict Language DevelopmentKANIA KUSUMA WARDANINo ratings yet

- Vocal Cues and Children's Mental Representations of Narratives: Effects of Incongruent Cues On Story ComprehensionDocument17 pagesVocal Cues and Children's Mental Representations of Narratives: Effects of Incongruent Cues On Story ComprehensionAdrienn MatheNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0271530916300945 MainDocument10 pages1 s2.0 S0271530916300945 MainMppaolantonio PaolantonioNo ratings yet

- Dialogic ReadingDocument12 pagesDialogic Readingmagar telvNo ratings yet

- Building A Powerful Reading ProgramDocument17 pagesBuilding A Powerful Reading ProgramInga Budadoy NaudadongNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument16 pagesResearch ProposalSuleman SaeedNo ratings yet

- Critical AnalysisDocument39 pagesCritical Analysisapi-283884559No ratings yet

- Parent-Child Conversations About Letters and PicturesDocument21 pagesParent-Child Conversations About Letters and PicturesAndreea DobritanNo ratings yet

- Social Contexts of Development: Parent-Child Interactions During Reading and PlayDocument23 pagesSocial Contexts of Development: Parent-Child Interactions During Reading and PlaybernardparNo ratings yet

- Acquisition of Literacy in Bilingual ChildrenDocument41 pagesAcquisition of Literacy in Bilingual ChildrenGeoff CavanoughNo ratings yet

- Developing Identity in Diversity: A Second Language Acquisition ExperienceDocument10 pagesDeveloping Identity in Diversity: A Second Language Acquisition ExperienceAanindia Brilyainza DiaNo ratings yet

- McburneyjamiebiblioDocument5 pagesMcburneyjamiebiblioapi-401233610No ratings yet

- Child - Language - Development - Kel 5 (1) - 1Document13 pagesChild - Language - Development - Kel 5 (1) - 1Jihan nafisa20No ratings yet

- Variable de Género: Contexto Socio - HistóricoDocument8 pagesVariable de Género: Contexto Socio - HistóricoJoseph NándezNo ratings yet

- Final CapstoneDocument14 pagesFinal Capstoneapi-434974983No ratings yet

- Article The Early Catastrophe AFT Spring 2003Document18 pagesArticle The Early Catastrophe AFT Spring 2003e.sepulvedaferradaNo ratings yet

- Gale Researcher Guide for: Comprehension and Meaning in LanguageFrom EverandGale Researcher Guide for: Comprehension and Meaning in LanguageNo ratings yet

- The Second Year Neurology Lockbook 2016Document2 pagesThe Second Year Neurology Lockbook 2016hirsi200518No ratings yet

- 1472 6874 10 8 PDFDocument7 pages1472 6874 10 8 PDFhirsi200518No ratings yet

- M-Mode Echocardiography: John N. Hamaty D.O. SJHGDocument37 pagesM-Mode Echocardiography: John N. Hamaty D.O. SJHGhirsi200518No ratings yet

- Objectives: Logical Framework Analysis (LFA)Document10 pagesObjectives: Logical Framework Analysis (LFA)hirsi200518No ratings yet

- Introduction To Echocardiography 2Document26 pagesIntroduction To Echocardiography 2Sandra GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Examination of The Newborn BabyDocument44 pagesExamination of The Newborn Babyhirsi200518No ratings yet

- MDR Somalia EID March 2013Document3 pagesMDR Somalia EID March 2013hirsi200518No ratings yet

- Pediatric Clinical ExamintionDocument74 pagesPediatric Clinical Examintionhirsi200518100% (1)

- General Principles of Gastroentorylogy.Document32 pagesGeneral Principles of Gastroentorylogy.hirsi200518No ratings yet

- Neurology MCQDocument16 pagesNeurology MCQSudhakar Subramanian100% (1)

- HistoryDocument64 pagesHistoryhirsi200518No ratings yet

- Application Form: M.SC Scholarship Programme For Eligible Member CountriesDocument9 pagesApplication Form: M.SC Scholarship Programme For Eligible Member Countrieshirsi200518No ratings yet

- Thorndikes Theory of LearningDocument19 pagesThorndikes Theory of LearningRose Marie Jaromay OderioNo ratings yet

- Aisyah Binti MD Nor NO. MATRIK: U2104435 Pensyarah: Dr. Siaw Yan LiDocument7 pagesAisyah Binti MD Nor NO. MATRIK: U2104435 Pensyarah: Dr. Siaw Yan LiEye SyahNo ratings yet

- UNIT-2-NOTES - Self Management Skills-IXDocument8 pagesUNIT-2-NOTES - Self Management Skills-IXVaishnavi Joshi50% (4)

- Master Your Emotions (Workbook)Document36 pagesMaster Your Emotions (Workbook)No tengoNo ratings yet

- Aminotes - NTCC Project Artificial IntelligenceDocument17 pagesAminotes - NTCC Project Artificial IntelligenceShashwat ShuklaNo ratings yet

- 4 - Week 4 - The Self According To PsychologyDocument4 pages4 - Week 4 - The Self According To PsychologySteve RogersNo ratings yet

- EmotiiDocument2 pagesEmotiiCiprian CiobanuNo ratings yet

- OCR-A-Level Psychology Study-Summaries Core-SampleDocument15 pagesOCR-A-Level Psychology Study-Summaries Core-SampleAyaNo ratings yet

- Psychology Theories of Learning From S.K MangalDocument21 pagesPsychology Theories of Learning From S.K MangalAyushi PandyaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Social IdentityDocument28 pagesChapter 2 Social Identityally natashaNo ratings yet

- (IRISH PARAGGUA) Reflection Paper, Theories of Personality-1Document5 pages(IRISH PARAGGUA) Reflection Paper, Theories of Personality-1irish paragguaNo ratings yet

- Multi CritterialDocument38 pagesMulti CritterialRaquel PanillosNo ratings yet

- Awaken The Giant Within - Summary - Review in PDF - The Power MovesDocument11 pagesAwaken The Giant Within - Summary - Review in PDF - The Power MovesAnte Perković100% (1)

- Sample Paper For COLA100Document6 pagesSample Paper For COLA100Bobby HillNo ratings yet

- Theory of Mind AutismDocument2 pagesTheory of Mind AutismLeticia JuradoNo ratings yet

- My Psychology 1st Edition Pomerantz Test BankDocument45 pagesMy Psychology 1st Edition Pomerantz Test Banksamuelhammondbzksifqnmt100% (30)

- Mapeh Q2 W9Document9 pagesMapeh Q2 W9Mickey Maureen DizonNo ratings yet

- PERSONAL DEVELOPMENT Module 3Document10 pagesPERSONAL DEVELOPMENT Module 3Gil PunowskiNo ratings yet

- UTS Module 4 Semi FinalsDocument24 pagesUTS Module 4 Semi Finalsgilbertjustin469No ratings yet

- Schools of Thought in Second Language AcquisitioNDocument19 pagesSchools of Thought in Second Language AcquisitioNMa. Theresa O. MerceneNo ratings yet

- Philosophical Perspective of The Self 2Document24 pagesPhilosophical Perspective of The Self 2ochoapauline02No ratings yet

- SOULMAKINGDocument18 pagesSOULMAKINGNezukoNo ratings yet

- Yourself Externalized (Neville Goddard)Document1 pageYourself Externalized (Neville Goddard)TC EmergeNo ratings yet

- UHV II Lecture 3 - Happiness and Prosperity v4Document10 pagesUHV II Lecture 3 - Happiness and Prosperity v4shashrzNo ratings yet

- University of Zimbabwe: Learning Principles (Psy 213)Document5 pagesUniversity of Zimbabwe: Learning Principles (Psy 213)Enniah MlalaziNo ratings yet

- Neo Behaviorism FinalDocument30 pagesNeo Behaviorism FinalsalviesanquilosNo ratings yet

- AP Psych History and Approaches Interactive NotebookDocument13 pagesAP Psych History and Approaches Interactive NotebookZaina NasserNo ratings yet

- Module 6Document10 pagesModule 6Antonette ArmaNo ratings yet

- A Review of Radical Behaviorism For ABA PractitionDocument6 pagesA Review of Radical Behaviorism For ABA PractitionJimmy MoralesNo ratings yet