0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

109 viewsTurman v. Bell, 54 Ark. 273, 15 S.W. 886 (Ark. 1891)

Turman v. Bell, 54 Ark. 273, 15 S.W. 886 (Ark. 1891)

Uploaded by

richdebtThe Arkansas Supreme Court conducted a careful analysis of the rulings of a number of sister states in connection with the application of the rule that possession of real estate by a party other than the vendor is notice of the rights of the occupant in the case of a grantor who continued in possession of property at the time of the grant and after the execution of the conveyance, and who did so pursuant to some unrecorded right or equity.

After careful consideration, it reached the conclusion that a grantor's continued possession will give notice, not necessarily of any rights the occupant can establish, but notice that will impose a duty upon the subsequent purchaser to make inquiry as to the rights of the occupant. The court's conclusion, prefaced by an observation, follows:

"We think, with all deference to those who deny the application of the rule in such cases, that the controlling fact upon which their argument proceeds is assumed. Ordinarily the terms of a general warranty deed import a declaration that the grantor has reserved no rights in the subject of the grant, and by themselves may always bear such implication. But possession is ordinarily notice of a claim of right; and where a grantor continues in possession at the time of the grant and for a considerable time thereafter, should not the fact of possession be construed as an assertion of reserved rights, and as a limitation upon the provisions of the deed? True, the deed alone denies the reservation of equities, but it denies equally the right to continue in possession. If the grantor then holds open possession against the terms of his deed, is it not a reasonable implication that he has rights not expressed in it? If possession thus qualifies the terms of the deed, and it is open and continued, then the doctrine of estoppel cannot apply, for the grantor may as well expect persons to take notice of his possession as of his deed.

We conclude that open and notorious possession of the lands by Turman from the date of his deed till the date of the bank's mortgage would give notice to the bank. But such notice only imposes a duty to make inquiry as to the rights of the occupant; and if he explain his possession in consonance with the right of his grantee to convey, he cannot attack the conveyances of the latter. If Turman held out Gilbreath as authorized to convey the land, either expressly or by a recognized course of dealing, then the bank would have been warranted in treating Turman's possession as in subordination to Gilbreath's right to convey, and would not be prejudiced by the notice."

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Turman v. Bell, 54 Ark. 273, 15 S.W. 886 (Ark. 1891)

Turman v. Bell, 54 Ark. 273, 15 S.W. 886 (Ark. 1891)

Uploaded by

richdebt0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

109 views6 pagesThe Arkansas Supreme Court conducted a careful analysis of the rulings of a number of sister states in connection with the application of the rule that possession of real estate by a party other than the vendor is notice of the rights of the occupant in the case of a grantor who continued in possession of property at the time of the grant and after the execution of the conveyance, and who did so pursuant to some unrecorded right or equity.

After careful consideration, it reached the conclusion that a grantor's continued possession will give notice, not necessarily of any rights the occupant can establish, but notice that will impose a duty upon the subsequent purchaser to make inquiry as to the rights of the occupant. The court's conclusion, prefaced by an observation, follows:

"We think, with all deference to those who deny the application of the rule in such cases, that the controlling fact upon which their argument proceeds is assumed. Ordinarily the terms of a general warranty deed import a declaration that the grantor has reserved no rights in the subject of the grant, and by themselves may always bear such implication. But possession is ordinarily notice of a claim of right; and where a grantor continues in possession at the time of the grant and for a considerable time thereafter, should not the fact of possession be construed as an assertion of reserved rights, and as a limitation upon the provisions of the deed? True, the deed alone denies the reservation of equities, but it denies equally the right to continue in possession. If the grantor then holds open possession against the terms of his deed, is it not a reasonable implication that he has rights not expressed in it? If possession thus qualifies the terms of the deed, and it is open and continued, then the doctrine of estoppel cannot apply, for the grantor may as well expect persons to take notice of his possession as of his deed.

We conclude that open and notorious possession of the lands by Turman from the date of his deed till the date of the bank's mortgage would give notice to the bank. But such notice only imposes a duty to make inquiry as to the rights of the occupant; and if he explain his possession in consonance with the right of his grantee to convey, he cannot attack the conveyances of the latter. If Turman held out Gilbreath as authorized to convey the land, either expressly or by a recognized course of dealing, then the bank would have been warranted in treating Turman's possession as in subordination to Gilbreath's right to convey, and would not be prejudiced by the notice."

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

The Arkansas Supreme Court conducted a careful analysis of the rulings of a number of sister states in connection with the application of the rule that possession of real estate by a party other than the vendor is notice of the rights of the occupant in the case of a grantor who continued in possession of property at the time of the grant and after the execution of the conveyance, and who did so pursuant to some unrecorded right or equity.

After careful consideration, it reached the conclusion that a grantor's continued possession will give notice, not necessarily of any rights the occupant can establish, but notice that will impose a duty upon the subsequent purchaser to make inquiry as to the rights of the occupant. The court's conclusion, prefaced by an observation, follows:

"We think, with all deference to those who deny the application of the rule in such cases, that the controlling fact upon which their argument proceeds is assumed. Ordinarily the terms of a general warranty deed import a declaration that the grantor has reserved no rights in the subject of the grant, and by themselves may always bear such implication. But possession is ordinarily notice of a claim of right; and where a grantor continues in possession at the time of the grant and for a considerable time thereafter, should not the fact of possession be construed as an assertion of reserved rights, and as a limitation upon the provisions of the deed? True, the deed alone denies the reservation of equities, but it denies equally the right to continue in possession. If the grantor then holds open possession against the terms of his deed, is it not a reasonable implication that he has rights not expressed in it? If possession thus qualifies the terms of the deed, and it is open and continued, then the doctrine of estoppel cannot apply, for the grantor may as well expect persons to take notice of his possession as of his deed.

We conclude that open and notorious possession of the lands by Turman from the date of his deed till the date of the bank's mortgage would give notice to the bank. But such notice only imposes a duty to make inquiry as to the rights of the occupant; and if he explain his possession in consonance with the right of his grantee to convey, he cannot attack the conveyances of the latter. If Turman held out Gilbreath as authorized to convey the land, either expressly or by a recognized course of dealing, then the bank would have been warranted in treating Turman's possession as in subordination to Gilbreath's right to convey, and would not be prejudiced by the notice."

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

109 views6 pagesTurman v. Bell, 54 Ark. 273, 15 S.W. 886 (Ark. 1891)

Turman v. Bell, 54 Ark. 273, 15 S.W. 886 (Ark. 1891)

Uploaded by

richdebtThe Arkansas Supreme Court conducted a careful analysis of the rulings of a number of sister states in connection with the application of the rule that possession of real estate by a party other than the vendor is notice of the rights of the occupant in the case of a grantor who continued in possession of property at the time of the grant and after the execution of the conveyance, and who did so pursuant to some unrecorded right or equity.

After careful consideration, it reached the conclusion that a grantor's continued possession will give notice, not necessarily of any rights the occupant can establish, but notice that will impose a duty upon the subsequent purchaser to make inquiry as to the rights of the occupant. The court's conclusion, prefaced by an observation, follows:

"We think, with all deference to those who deny the application of the rule in such cases, that the controlling fact upon which their argument proceeds is assumed. Ordinarily the terms of a general warranty deed import a declaration that the grantor has reserved no rights in the subject of the grant, and by themselves may always bear such implication. But possession is ordinarily notice of a claim of right; and where a grantor continues in possession at the time of the grant and for a considerable time thereafter, should not the fact of possession be construed as an assertion of reserved rights, and as a limitation upon the provisions of the deed? True, the deed alone denies the reservation of equities, but it denies equally the right to continue in possession. If the grantor then holds open possession against the terms of his deed, is it not a reasonable implication that he has rights not expressed in it? If possession thus qualifies the terms of the deed, and it is open and continued, then the doctrine of estoppel cannot apply, for the grantor may as well expect persons to take notice of his possession as of his deed.

We conclude that open and notorious possession of the lands by Turman from the date of his deed till the date of the bank's mortgage would give notice to the bank. But such notice only imposes a duty to make inquiry as to the rights of the occupant; and if he explain his possession in consonance with the right of his grantee to convey, he cannot attack the conveyances of the latter. If Turman held out Gilbreath as authorized to convey the land, either expressly or by a recognized course of dealing, then the bank would have been warranted in treating Turman's possession as in subordination to Gilbreath's right to convey, and would not be prejudiced by the notice."

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 6

Caution

As of: Jul 25, 2014

TURMAN v. BELL.

[NO NUMBER IN ORIGINAL]

SUPREME COURT OF ARKANSAS

54 Ark. 273; 15 S.W. 886; 1891 Ark. LEXIS 50

February 28, 1891, Decided

PRIOR HISTORY: [***1] APPEAL from Scott Circuit Court in Chancery.

JOHN S. LITTLE, Judge.

Suit to remove cloud upon title. Turman conveyed the land to Gilbreath in 1884 as security for a loan, and took a

deed of defeasance. Gilbreath in 1885 mortgaged the land to the National Bank of Western Arkansas. The bank brought

suit to foreclose the lien without making Turman a party. Plaintiffs, Bell and others, purchased at the foreclosure sale. In

1888 they brought this suit to cancel Turman's deed of defeasance as a cloud upon their title, making Gilbreath's

administrator, Forrester, a party. Turman filed a cross-complaint, asking to redeem the land upon payment of the

amount of the debt due by him to Gilbreath's estate. No summons was issued upon the cross-complaint for the

co-defendant, Forrester, nor did he enter his appearance. Upon the pleadings and evidence the court dismissed the

cross-complaint, and decreed that Turman's deed be canceled. Turman appealed.

The facts are stated in the opinion.

DISPOSITION: Judgment reversed and cause remanded.

CORE TERMS: notice, deed, mortgage, grantor, recorded, foreclosure, defeasance, recorder, certificate, mortgagee,

purchaser, reserved, holder, unrecorded, misconduct, grantee, convey, subsequent purchaser, estopped to assert,

sufferance, registry, stranger, redeem, right of possession, recorders office, warranty deed, gave notice, reservation,

declaration, occupant

HEADNOTES

1. Mortgage foreclosure--Parties.

Page 1

The estoppel of a grantor of an absolute deed, retaining an unrecorded defeasance, as to a mortgagee of his grantee

without notice of his equities, operates only to postpone his rights to the lien of the mortgagee, and does not extinguish

them, nor authorize a foreclosure of them by a suit to which he was not a party.

2. Subrogation--Purchase at mortgage sale.

A purchaser at a foreclosure sale succeeds to all the rights of the holder of the mortgage foreclosed.

3. Priorities--Notice.

A mortgagee with notice that the mortgagor holds as security can enforce his lien only to the extent of the

mortgagor's claim against his grantor; but if he took without notice, he can collect the entire mortgage debt.

4. Withdrawal of unrecorded deed--Negligence.

The rule that the holder of a deed has done all that is necessary under the registry laws to give notice of its contents

when he files it for record and that the subsequent misconduct or neglect of the recorder cannot prejudice his rights, is

subject to the qualification that where he carelessly takes it from the recorders office before it is recorded and without

noticing that it contains no certificate of record, a subsequent bona fide purchaser will be protected. Oats v. Walls, 28

Ark. 244, qualified.

5. Warranty deed--Possession of grantor--Notice of equities.

Where a vendor of agricultural land continued openly and notoriously in possession of the premises six months

after the execution of a warranty deed, and after the time when such lands were usually entered upon for the next

season's cultivation, his possession was sufficient to put a subsequent purchaser upon notice of his equities, unless such

vendor, either expressly or by a recognized course of dealing, held out his vendee as authorized to convey.

6. Equity--New trial.

An equity cause will be remanded for a new trial when both parties have without fault omitted to introduce

testimony upon a material point.

7. Cross-complaint--Service on co-defendant.

Judgment should not be rendered on a cross-complaint against a codefendant who has not been summoned or

warned to appear and who has not appeared.

COUNSEL: J. M. Moore, Geo. H. Sanders and T. P. Winchester for appellant.

L. P. Sandels and C. E. Warner for appellees.

1. Supposing that Turman did file [***2] the deed for record, were his acts in that behalf sufficient? 28 Ark. 244.

2. In view of the facts proven they were not. He placed Gilbreath in a position to perpetrate a wrong upon others.

3. A person is presumed to know the exact state of his title, and ignorance will not help him. And, in invoking the

doctrine of estoppel, it does not matter whether Turman knew or not that his defeasance was not of record. 1 Johns. Ch.

344, 351, top; 129 Mass. 380; 7 Cr., 20; 2 Pom. Eq., sec. 731, and note 3, and sec. 821; 6 A. & E., p. 115; 3 Wash. R.

P., 109-10; Bigelow on Estoppel, pp. 544 et seq.; 6 Johns. Ch. 166; 18 Ark. 142; 24 id., 399; 93 Ind. 575; 51 N.H. 297.

4. Were appellees bona fide purchasers? They were if the bank was. A mortgagee is a bona fide purchaser. 49 Ark. 214.

If Turman could not have set up his claim against the bank, he cannot set it up as against appellees. 2 Pom. Eq., secs.

Page 2

54 Ark. 273, *; 15 S.W. 886, **;

1891 Ark. LEXIS 50, ***1

754, 724; 1 Story, Eq., sec. 409; 78 Mo. 458; 11 Ark. 137.

JUDGES: HEMINGWAY, J.

OPINION BY: HEMINGWAY

OPINION

[*275] [**887] HEMINGWAY, J. As a general rule, no person can be affected by any judicial proceeding to

which he is not a party; and a judgment takes effect only between the parties, [***3] and gives no rights to or against

third persons. Freeman on Judg., sec. 154. So a foreclosure is effectual against only those persons interested in the

equity who were parties; and while the foreclosure of a paramount lien convey's title, it is subject to the right of

redemption of junior incumbrancers who were not parties to the proceeding. 2 Jones on Mort., sec. 1395. In this case the

parties have treated the transactions between Gilbreath and Turman as a mortgage, and we think properly. Turman was

therefore the equitable owner of the land, and Gilbreath held the legal title only by way of security. The mortgagees of

Gilbreath could not therefore foreclose Turman's equity of redemption in a suit to which he was not a party.

1. Parties necessary to mortgage foreclosure.

It is argued that Turman is estopped to assert his equities against the bank, the mortgagee of Gilbreath, because he

permitted the bank to take its mortgage and kept his equities hidden. If the fact be as alleged, the estoppel would only

operate to postpone the rights of Turman to the lien of the bank. It would not extinguish his rights or authorize the bank

to foreclose them by a suit to which he was a stranger.

[***4] It is further argued that he is estopped to assert his equities against the plaintiffs, purchasers at the

foreclosure sale, because he permitted them to purchase without disclosing his interest. This contention, we think, rests

upon no basis of fact. Before the sale under the decree he filed with the recorder and had recorded Gilbreath's deed of

defeasance, and that gave notice of his rights under it to all persons dealing with the property. Moreover he was present

at the sale, and before the land was offered he gave notice of his [*276] equities to all persons in attendance. It is true

that there is a conflict of evidence as to the latter fact, but we think the fair preponderance sustains our statement. He

testified positively that he gave the notice by reading a paper which he had previously prepared. To strengthen his

statement, he produced the paper and incorporated it in his testimony. His narrative is either true or corruptly false; for,

if he in fact did not give the notice, he could not believe that he had given it, or innocently produce as a paper read one

which in fact he had not read. He is corroborated in his statement by a number of witnesses. On the other side several

[***5] witnesses testified that they heard him read no such notice, and one testified that he did not read it. They may be

honest, and nevertheless Turman's statement may be true. That he read one notice all agree; and it may be that, although

he read another, these witnesses failed to observe that the reading included more than one paper. Or, as several years

intervened between the day of sale and that of testifying, they may not have recalled on the latter date all that they

observed on the former.

2. Subrogation.

3. Notice of prior lien.

So we hold that Turman had an interest in the property of which he could not be deprived by a foreclosure to which

he was a stranger, and that he is not estopped to assert it in a proceeding to redeem from the purchaser under the

foreclosure.

Upon what terms is he entitled to redeem? In approaching that question it may be well to say that the plaintiffs, as

purchasers at the foreclosure sale, succeeded to all the rights of the bank as holder of the mortgage foreclosed. 2 Jones

on Mort., sec. 1395, and cases cited. What those rights were as against Turman, we shall now proceed to consider.

Page 3

54 Ark. 273, *; 15 S.W. 886, **;

1891 Ark. LEXIS 50, ***2

If the bank took the mortgage with notice that Gilbreath held [***6] the lands only by way of security and that the

equitable title was in Turman, then the rights conferred by the mortgage could not be greater as against Turman than

Gilbreath actually held. If, on the contrary, Turman invested [*277] Gilbreath with the legal title to the land and

clothed him with the indicia of absolute ownership, and the bank took its mortgage without notice of his qualified

rights, then Turman cannot set up his claim to prejudice the collection of its mortgage debt. That does not imply that

Turman may not set up his right to redeem as against, the mortgage, but only that he cannot set it up so as to prejudice

or defeat the collection of the claim secured. We hold that if the bank took the mortgage with the notice of Turman's

rights, it can collect from the land no more than Gilbreath could; but if it took without notice, it can collect the entire

amount due on its mortgage.

Turman contends that the bank took with notice given, first, by the filing of the instrument of defeasance for record,

and, second, by his open and notorious possession of the land continued from the time that Gilbreath received his deed

until the bringing of this suit.

Negligent withdrawal [***7] of unrecorded deed.

The facts as bearing upon the alleged notice by registry are: that on the day the defeasance was executed--being

about one month after the execution of the deed--Turman left it with the recorder of the county to be recorded, and it

was then indorsed by the recorder as filed for record. Some time afterwards (the date cannot be definitely fixed from the

proof) Turman called for the defeasance, and it was delivered to him by the recorder. It had not been recorded, and there

was attached to it no certificate of the recorder that it had been. Subsequently, after having made a search of the records

which failed to discover the defeasance, the bank took its mortgage. It appears that the bank had no knowledge of the

defeasance. Turman believed that it had been recorded, and did not discover his mistake until after the bank obtained the

[**888] decree of foreclosure. Upon these facts it is contended that notice of the defeasance was given from the time it

was filed for record. That contention is supported by the decision of this court in the case of Oats v. Walls, 28 Ark. 244;

and if it is to be followed without limitation, it is decisive of this [***8] case. In the opinion in that case the court

[*278] used the following language: "In this case, Oats took his deed to the proper office, placed it in the hands of the

person there in charge, and paid the fees for recording--this was all he was required to do. And any acts thereafter to be

done to perfect the record and make the notice full to all subsequent purchasers, etc., devolved upon the clerk, and could

not operate to the prejudice of the mortgagee."

That the holder of the deed has done all that is necessary under our registry laws to give notice of its contents when

he files it for record and that the subsequent misconduct or neglect of the recorder cannot prejudice his rights, is the

established law. But while such holder is exempt from prejudice by the misconduct or neglect of the clerk, we do not

think the exemption should extend to his own acts that through design or negligence affect others. If A should file a

deed to be recorded, and the recorder should so indorse it, and A should immediately take it out of the office, it would

not be contended that such filing imparted any notice. Suppose that A, instead of taking the deed immediately after it is

indorsed by the [***9] officer, should remain long enough in the office for the officer to record it, and should then take

it out, knowing that it had not been recorded, would any one contend that such filing imparted notice to subsequent

purchasers from A's grantor? If not, then if A took the deed out of the recorder's office without knowing whether it had

been recorded or not, and when he might have known, by examining it for a recorder's certificate, that it had not been

recorded, can he insist that such filing imparts notice to subsequent bona fide purchasers? The statute requires, when a

deed has been recorded, that the recorder attach to it a certificate of the fact of record. When the owner takes a deed

from the recorder's office, he can easily ascertain either that the certificate is or is not attached; and if it is not, he has no

right to conclude that the deed has been recorded or to remove it from file. If he remove his deed before it is recorded,

he places it in [*279] the power of the grantor to exhibit a clear title and thus to mislead and deceive subsequent

purchasers. By the exercise of slight care and caution he could have averted such a possibility; but if he fails to do it,

persons [***10] ignorant of the deed, who have examined the records, may be induced to purchase, when they have

exhausted all usual means of inquiry and information. If they do thus purchase, a loss must be borne. Where should it

fall? Upon him whose care and caution could not prevent it, or upon him whose slight care and caution would have

prevented it? The question implies its own answer. The party whose negligence made the loss possible should bear it,

Page 4

54 Ark. 273, *276; 15 S.W. 886, **887;

1891 Ark. LEXIS 50, ***5

and should be estopped to set up his prior right against the party without fault.

The doctrine of constructive notice by registration rests upon the idea that all persons may learn and actually know

that of which the law gives notice and implies knowledge; and it would contravene every principle of right and fair

dealing to permit one to insist upon this constructive notice and claim the benefit of this implied knowledge, when his

act had made such knowledge unattainable. We do not think the filing gave the bank notice of Turman's defeasance.

These are our views, after a careful and serious consideration of Oats v. Walls, 28 Ark. 244, supra. The cases cited

in support of that case have been examined and scrutinized by us, [***11] and do not conflict with the views herein

expressed. In them it was held that where the holder of a deed filed it for record, and subsequent adverse interests were

created before it was recorded, the notice was complete by the filing; but they were cases in which the failure to record

was due to the delay of the recorder, the loss or destruction of the deed, or its abstraction from the files; in none of them

did there enter the element of the owner's misconduct, either wilful or negligent. In so far as that case holds that a deed

is notice of its provisions from the time it is filed for record and that the effect of such notice can not be impaired by the

misconduct of the officer, it is approved; but in so far as it holds [*280] that the notice continues as against those who

in good faith and for value acquire adverse interests after the deed, unrecorded and without a certificate of record, is

withdrawn from the files, it is overruled.

Possession of grantor is notice of equities reserved when.

Turman continued in the possession of the lands from the date of his deed to Gilbreath in August, 1884, until the

execution of the mortgage to the bank in February, 1885--in fact, until [***12] the trial of this cause in the court below;

and it is contended that this gave notice of all his rights. As a general rule the possession of land gives notice to all the

world of the rights of the occupant, when there is no record evidence of his right of possession; but to this rule there are

well-established exceptions. Whether the continuing possession of a grantor, after he has executed a deed of general

warranty, comes within the rule or its exceptions, was suggested but not decided by this court in the case of Gill v.

Hardin, 48 Ark. 409, 3 S.W. 519. We know of no other case in which the question has been alluded to by this court.

Between the appellate courts of other States there is an irreconcilable conflict of ruling, and upon either side are to be

found courts of the highest authority.

Those that sustain the application of the rule say that, by the terms of the deed, the grantor has not the right of

possession, and that his continuing possession gives notice that he has rights reserved not expressed in the deed; that,

inasmuch as the records disclose no right of possession, it is but reasonable to conclude that the continuing possession

rests upon some [***13] right not disclosed by the records, and that the reasonableness of such conclusion imposes

upon persons about to deal with [**889] the land the duty to make inquiry. Illinois Central R. Co. v. McCullough, 59

Ill. 166; Daubenspeck v. Platt, 22 Cal. 330; New v. Wheaton, 24 Minn. 406; Hopkins v. Garrard, 46 Ky. 312, 7 B. Mon.

312; Webster v. Maddox, 6 Me. 256; Seymour v. McKinstry, 106 N.Y. 230, 12 N.E. 348; Wright v. Bates, 13 Vt. 341.

On the other side it is said that the execution of a warranty deed without reservation is a most solemn declaration

[*281] by the grantor that he has parted with all his rights in the property, and directly negatives the reservation of any

right. That those who see the deed are warranted in relying upon such declaration as much as if it had been made to

them orally upon an inquiry, and that if they acquire interests in faith of such reliance, the grantor in possession will be

estopped to assert any right secretly reserved from the grant. That as the grantor has declared that he parted with his

entire [***14] estate, strangers about to deal with the property would reasonably refer his continuous possession to the

sufferance of the grantee, and would not reasonably think to refer it to a reserved right. Eylar v. Eylar, 60 Tex. 315; Van

Keuren v. Central R. Co., 38 N.J.L. 165; Scott v. Gallagher, 14 S. & R. 333; Jaques v. Weeks, 7 Watts 261; Koon v.

Tramel, 71 Iowa 132, 32 N.W. 243; Bloomer v. Henderson, 8 Mich. 395.

If the possession has continued after the making of the deed but a short time, it might be reasonably referred to the

sufferance of the grantee; but where it was long continued, it would much more strongly imply a right in the occupant,

and the implication would be sufficient to cast upon strangers the duty of inquiry. Where the lands were used for

Page 5

54 Ark. 273, *279; 15 S.W. 886, **888;

1891 Ark. LEXIS 50, ***10

agriculture and sold during a crop season, it would not be reasonable to presume that the grantee would permit the

grantor to hold by sufferance after the time when lands were usually entered upon for the purpose of the next year's

cultivation; and possession continued after that time could not be explained upon the presumption [***15] of

sufferance.

We think, with all deference to those who deny the application of the rule in such cases, that the controlling fact

upon which their argument proceeds is assumed. Ordinarily the terms of a general warranty deed import a declaration

that the grantor has reserved no rights in the subject of the grant, and by themselves may always bear such implication.

But possession is ordinarily notice of a claim of right; and where a grantor continues in possession at the time of the

grant and for a considerable time thereafter, [*282] should not the fact of possession be construed as an assertion of

reserved rights, and as a limitation upon the provisions of the deed? True, the deed alone denies the reservation of

equities, but it denies equally the right to continue in possession. If the grantor then holds open possession against the

terms of his deed, is it not a reasonable implication that he has rights not expressed in it? If possession thus qualifies the

terms of the deed, and it is open and continued, then the doctrine of estoppel cannot apply, for the grantor may as well

expect persons to take notice of his possession as of his deed. We conclude that open and notorious [***16] possession

of the lands by Turman from the date of his deed till the date of the bank's mortgage would give notice to the bank. But

such notice only imposes a duty to make inquiry as to the rights of the occupant; and if he explain his possession in

consonance with the right of his grantee to convey, he cannot attack the conveyances of the latter. If Turman held out

Gilbreath as authorized to convey the land, either expressly or by a recognized course of dealing, then the bank would

have been warranted in treating Turman's possession as in subordination to Gilbreath's right to convey, and would not

be prejudiced by the notice.

6. When equity will remand for new trial.

It appears in a general and indefinite way that Gilbreath made sales of portions of the property conveyed to him by

Turman, but the evidence does not disclose the dates or circumstances thereof; and we cannot determine what effect

they should have upon the notice by possession. Moreover, the parties directed their attention to the development of the

facts with reference to the filing and withdrawing from file of the instrument of defeasance, and did not fully develop

the facts relative to Turman's continued possession. [***17] They treated the case of Oats v. Walls, 28 Ark. 244, supra,

as settling the law of notice by registry, and limited their evidence to the good faith of Turman in withdrawing his

unrecorded defeasance from the files. Justice demands [*283] that further proof be permitted to supply the omission as

to the matters above indicated.

It is contended, and the record contains suggestions, that Turman received a part of the money secured by the bank

mortgage, in addition to the amount he owed Gilbreath; if so, he can redeem only by paying it as well as his original

debt. But if the mortgage represented money borrowed by Gilbreath for his own use, or for the purpose of discharging

debts of Turman which he was bound by the terms of his agreement with Turman to pay, then the amount charged on

the land in favor of plaintiffs should be credited on Turman's debt to Gilbreath.

7. Service of process upon filing of cross bill.

It does not appear that Gilbreath's administrator was made a party to Turman's cross-complaint, or that he appeared

to it. In order that the rights of the parties may be fully adjudicated, he should be made a party.

We do not usually remand an equity [***18] cause for a new trial; but we should vary the practice where it is

obvious that a cause cannot be otherwise intelligently determined, and such condition exists without fault of the parties.

We therefore reverse the judgment for the reasons indicated, and remand the cause for further proceedings and retrial.

Page 6

54 Ark. 273, *281; 15 S.W. 886, **889;

1891 Ark. LEXIS 50, ***14

You might also like

- Retail Math Workbook Test W.answersDocument3 pagesRetail Math Workbook Test W.answersc00kiepuss33% (3)

- AP Macroeconomics - Models & Graphs Study GuideDocument22 pagesAP Macroeconomics - Models & Graphs Study GuideLynn Hollenbeck Breindel100% (2)

- Chapter 20 Homework SolutionDocument6 pagesChapter 20 Homework SolutionJackNo ratings yet

- (Goldman Sachs) A Mortgage Product PrimerDocument141 pages(Goldman Sachs) A Mortgage Product Primer00aa100% (1)

- Cruz VDocument16 pagesCruz Vhoward almunidNo ratings yet

- Cameron v. Romele, 53 Tex. 238 (Tex. 1880)Document5 pagesCameron v. Romele, 53 Tex. 238 (Tex. 1880)richdebtNo ratings yet

- Cruz and Cruz v. Bancom Finance CorporationDocument4 pagesCruz and Cruz v. Bancom Finance CorporationYvonne MallariNo ratings yet

- Case HeadnotesDocument18 pagesCase HeadnotesittnocNo ratings yet

- Bautista Vs SilvaDocument5 pagesBautista Vs SilvaJhan MelchNo ratings yet

- Cases Civrev2salesDocument17 pagesCases Civrev2salesjealousmistressNo ratings yet

- Hrs of Eduardo Manlapat vs. CADocument23 pagesHrs of Eduardo Manlapat vs. CARomeo de la CruzNo ratings yet

- Andrus v. St. Louis Smelting & Refining Co., 130 U.S. 643 (1889)Document3 pagesAndrus v. St. Louis Smelting & Refining Co., 130 U.S. 643 (1889)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Santos vs. Santos 366 SCRA 395, October 02, 2001Document14 pagesSantos vs. Santos 366 SCRA 395, October 02, 2001Justin Jomel ConsultaNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Eduardo Manlapat vs. Court of AppealsDocument31 pagesHeirs of Eduardo Manlapat vs. Court of AppealsUfbNo ratings yet

- Digested Cases - Emmelie DemafilesDocument69 pagesDigested Cases - Emmelie DemafilesEmmelie DemafilesNo ratings yet

- Petitioner vs. vs. Respondents: First DivisionDocument11 pagesPetitioner vs. vs. Respondents: First DivisionKimberly GangoNo ratings yet

- Final Digest HW2 Prop. 2Document35 pagesFinal Digest HW2 Prop. 2Quennie Jane SaplagioNo ratings yet

- C. Statement of Personal Circumstances (Sec. 45) : Litam vs. EspirituDocument6 pagesC. Statement of Personal Circumstances (Sec. 45) : Litam vs. EspirituJillandroNo ratings yet

- FactsDocument4 pagesFactsjessamontivillaNo ratings yet

- Sabistana Vs MuerteguiDocument4 pagesSabistana Vs MuerteguiRaphael Antonio AndradaNo ratings yet

- Case No. 31 - Heirs of Arturo Reyes Vs Socco Beltran: IssueDocument69 pagesCase No. 31 - Heirs of Arturo Reyes Vs Socco Beltran: IssueEmmelie DemafilesNo ratings yet

- Effects of Forgery and Void TitleDocument5 pagesEffects of Forgery and Void TitleMeku DigeNo ratings yet

- 21.11 Naval V CADocument3 pages21.11 Naval V CAFrankel Gerard MargalloNo ratings yet

- Tompkins v. Wheeler, 41 U.S. 106 (1842)Document12 pagesTompkins v. Wheeler, 41 U.S. 106 (1842)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Sales 6 Santos To AcabalDocument136 pagesSales 6 Santos To AcabalKim Muzika PerezNo ratings yet

- Hemedes Vs CADocument9 pagesHemedes Vs CAGoodyNo ratings yet

- Digested Oblicon CasesDocument16 pagesDigested Oblicon CasesRaffy Acorda Calayan SarmumanNo ratings yet

- Sales Case Doctrines FinalsDocument9 pagesSales Case Doctrines FinalsZariCharisamorV.Zapatos100% (1)

- Evidence EstoppelDocument9 pagesEvidence Estoppelwabwirejames20No ratings yet

- 1994 Tenio Obsequio v. Court of Appeals20161107 672 QqyoirDocument9 pages1994 Tenio Obsequio v. Court of Appeals20161107 672 QqyoirLei MorteraNo ratings yet

- Trinidad, Mikhail Matrix B. 2E 1. Tuason V.S Rodriguez, G.R. No. L-9372 December 15, 1914Document5 pagesTrinidad, Mikhail Matrix B. 2E 1. Tuason V.S Rodriguez, G.R. No. L-9372 December 15, 1914Mikhail TrinidadNo ratings yet

- Naval V CaDocument2 pagesNaval V CaLawstudentArellanoNo ratings yet

- Eagle Realty Corporation CaseDocument2 pagesEagle Realty Corporation Case1y3kNo ratings yet

- Double Sale and WarrantyDocument4 pagesDouble Sale and WarrantyNorthern SummerNo ratings yet

- Santos V SantosDocument15 pagesSantos V SantosMR100% (1)

- Retro To Certain 3rd Persons, Period of Repurchase Being 3 Years, But She Died inDocument30 pagesRetro To Certain 3rd Persons, Period of Repurchase Being 3 Years, But She Died inMylaCambriNo ratings yet

- Trusts: Bar Questions and AnswersDocument21 pagesTrusts: Bar Questions and AnswersDenver Dela Cruz Padrigo100% (1)

- Sales Case DigestDocument23 pagesSales Case DigestOwen BuenaventuraNo ratings yet

- LTDDocument3 pagesLTDAustine CamposNo ratings yet

- Conde vs. Ca FactsDocument8 pagesConde vs. Ca FactsasdfghjkattNo ratings yet

- CD 7 Cavite Dev. Bank vs. Sps. LimDocument2 pagesCD 7 Cavite Dev. Bank vs. Sps. LimLeeNo ratings yet

- Freiburg v. Dreyfus, 135 U.S. 478 (1890)Document5 pagesFreiburg v. Dreyfus, 135 U.S. 478 (1890)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Dy, Jr. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 92989Document8 pagesDy, Jr. v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 92989Krister VallenteNo ratings yet

- Balatbat vs. Court of AppealsDocument12 pagesBalatbat vs. Court of AppealsLiene Lalu NadongaNo ratings yet

- Who Is The Ostensible OwnerDocument10 pagesWho Is The Ostensible OwnerdeepakNo ratings yet

- Ejectment: Prescription, Possession, Not Ownership Quevada V. Court of Appeals 502 SCRA 233 FactsDocument18 pagesEjectment: Prescription, Possession, Not Ownership Quevada V. Court of Appeals 502 SCRA 233 FactsColeenNo ratings yet

- Sales Case Assignment GR Num and SylabiDocument36 pagesSales Case Assignment GR Num and SylabiArnel MangilimanNo ratings yet

- Lu VS ManiponDocument11 pagesLu VS Maniponbenjamin ladesmaNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Jose S. Fineza For PetitionerDocument28 pagesSupreme Court: Jose S. Fineza For PetitionerFrances Anne GamboaNo ratings yet

- PART II-B - V. Defective ContractsDocument40 pagesPART II-B - V. Defective ContractstagteamNo ratings yet

- 5 Gruenberg v. CADocument5 pages5 Gruenberg v. CAKatherine NavarreteNo ratings yet

- Case Digests2Document8 pagesCase Digests2KwekNo ratings yet

- Veloso Vs CA (1996)Document2 pagesVeloso Vs CA (1996)San Pedro TeamNo ratings yet

- Mariano Vs CADocument3 pagesMariano Vs CApapaburgundyNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Eduardo Manlapat vs. Court of AppealsDocument12 pagesHeirs of Eduardo Manlapat vs. Court of AppealsClaudia LapazNo ratings yet

- Practice Court Pre TrialDocument7 pagesPractice Court Pre TrialAJMordenoNo ratings yet

- Book 3 Land Problems and Remedi EsDocument4 pagesBook 3 Land Problems and Remedi EsBok MalaNo ratings yet

- EstoppelDocument4 pagesEstoppelahmad earlNo ratings yet

- Flegenheimer v. General Mills, Inc, 191 F.2d 237, 2d Cir. (1951)Document7 pagesFlegenheimer v. General Mills, Inc, 191 F.2d 237, 2d Cir. (1951)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Fuentebella and Cea For Appellant. Haussermann, Ortigas, Cohn and Fisher For AppelleesDocument4 pagesSupreme Court: Fuentebella and Cea For Appellant. Haussermann, Ortigas, Cohn and Fisher For AppelleesMil LoronoNo ratings yet

- Mirror DoctrineDocument9 pagesMirror DoctrineJanet Tal-udanNo ratings yet

- Succession - DigestDocument237 pagesSuccession - DigestArianeNo ratings yet

- (No. 9374. February 16, 1915.) FRANCISCO DEL VAL ET AL., Plaintiffs and AppellantsDocument10 pages(No. 9374. February 16, 1915.) FRANCISCO DEL VAL ET AL., Plaintiffs and AppellantsjoyeduardoNo ratings yet

- Cape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyFrom EverandCape Law: Texts and Cases - Contract Law, Tort Law, and Real PropertyNo ratings yet

- EasyKnock v. Feldman and Feldman - Motion To DismissDocument32 pagesEasyKnock v. Feldman and Feldman - Motion To DismissrichdebtNo ratings yet

- A - Baron v. GalassoDocument97 pagesA - Baron v. GalassorichdebtNo ratings yet

- EasyKnock v. Feldman and Feldman - Memorandum and OrderDocument12 pagesEasyKnock v. Feldman and Feldman - Memorandum and OrderrichdebtNo ratings yet

- Cusumano v. Hartland MeadowsDocument70 pagesCusumano v. Hartland MeadowsrichdebtNo ratings yet

- If You Can't Trust Your Lawyer, 138 Univ. of Pennsylvania Law Rev. 785Document10 pagesIf You Can't Trust Your Lawyer, 138 Univ. of Pennsylvania Law Rev. 785richdebtNo ratings yet

- Effect of Persons in Possession of Real Estate Other Than The Owner/Vendor On A Buyer's Status As A Bona Fide Purchaser - Georgia State Court CasesDocument207 pagesEffect of Persons in Possession of Real Estate Other Than The Owner/Vendor On A Buyer's Status As A Bona Fide Purchaser - Georgia State Court CasesrichdebtNo ratings yet

- Undoing Sale Leaseback Foreclosure Scams in Washington StateDocument77 pagesUndoing Sale Leaseback Foreclosure Scams in Washington Staterichdebt100% (1)

- Appellate Brief (Reply Brief) - Equitable Mortgage by Center For Responsible LendingDocument30 pagesAppellate Brief (Reply Brief) - Equitable Mortgage by Center For Responsible LendingrichdebtNo ratings yet

- Armstrong Settlement LetterDocument1 pageArmstrong Settlement LetterrichdebtNo ratings yet

- Opinion/Court Ruling - in Re Fowler, 425 B.R. 157 (Bankr. E.D. 2010)Document91 pagesOpinion/Court Ruling - in Re Fowler, 425 B.R. 157 (Bankr. E.D. 2010)richdebtNo ratings yet

- Scheerer v. Cuddy, 85 Cal. 270 (1890)Document4 pagesScheerer v. Cuddy, 85 Cal. 270 (1890)richdebtNo ratings yet

- Attorney's Fees Order - in Re Fowler, 425 B.R. 157 (Bankr. E.D. 2010)Document1 pageAttorney's Fees Order - in Re Fowler, 425 B.R. 157 (Bankr. E.D. 2010)richdebtNo ratings yet

- Loan AgreementDocument5 pagesLoan Agreement4htcgcnhwdNo ratings yet

- Balance Sheet Prepare and AnalyseDocument9 pagesBalance Sheet Prepare and AnalyseSatyarth GaurNo ratings yet

- Forex BookDocument31 pagesForex Bookibudanish79No ratings yet

- FIDIC 2017 由业主设计的建筑和工程施工合同条件Document20 pagesFIDIC 2017 由业主设计的建筑和工程施工合同条件linglign weiNo ratings yet

- ACT183 - Chapter 6 Capital Gains TaxationDocument3 pagesACT183 - Chapter 6 Capital Gains TaxationNorhanifah R. TampiNo ratings yet

- Conceptual FrameworkDocument5 pagesConceptual Frameworkaluadapril6No ratings yet

- The US Foodservice Accounting FraudDocument14 pagesThe US Foodservice Accounting FraudAnant Agarwal0% (1)

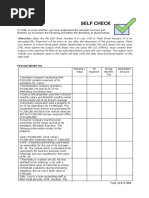

- Self Check: Direction: Open The File Self Check Number 5 in Your LMS or Flash Email Account. It Is AnDocument13 pagesSelf Check: Direction: Open The File Self Check Number 5 in Your LMS or Flash Email Account. It Is AnDanah Paz MamanaoNo ratings yet

- Introduction of TescoDocument25 pagesIntroduction of TescoMuhammad Imran ShahzadNo ratings yet

- CF Assignment Maruti SuzukiDocument6 pagesCF Assignment Maruti SuzukiRuchika SinghNo ratings yet

- 978-1119504306 Financial Accounting - 4thDocument4 pages978-1119504306 Financial Accounting - 4thtaupaypayNo ratings yet

- Lba Ii: 1. Origin and Development of Co-Operative SocietiesDocument36 pagesLba Ii: 1. Origin and Development of Co-Operative SocietiesJimmy KiharaNo ratings yet

- Report On Investment Activities of Islami Bank Bangladesh LimitedDocument93 pagesReport On Investment Activities of Islami Bank Bangladesh Limitedmithila75% (4)

- Gross Profit RatioDocument2 pagesGross Profit RatioShahzad AhmedNo ratings yet

- .Project of Nse and BseDocument77 pages.Project of Nse and BseRavi SutharNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - International Banking & Money MarketDocument21 pagesChapter 1 - International Banking & Money MarketFaiz FahmiNo ratings yet

- Creative Industry EcosystemDocument83 pagesCreative Industry Ecosystemandisboediman100% (3)

- Page Loan FormDocument2 pagesPage Loan FormChukwuemeka Great NwankwoNo ratings yet

- Ranjani-211420631111 RemovedDocument91 pagesRanjani-211420631111 RemovedSangeethaNo ratings yet

- IAL BusinessDocument64 pagesIAL BusinessShouqbsNo ratings yet

- Accion in Rem VersoDocument15 pagesAccion in Rem VersoJohnNo ratings yet

- PT AGIS Tbk.sDocument4 pagesPT AGIS Tbk.sRizka FurqorinaNo ratings yet

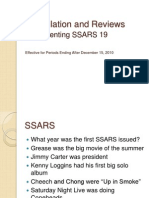

- SSARS 19 - Compilation and ReviewsDocument72 pagesSSARS 19 - Compilation and ReviewsCharles B. HallNo ratings yet

- 05 - 07 July 2024 Istanbul, TurkeyDocument6 pages05 - 07 July 2024 Istanbul, TurkeymscecogerNo ratings yet

- Contract of BailmentDocument22 pagesContract of BailmentRadhika ReddyNo ratings yet

- C. 30% of The Premium On The Base PolicyDocument12 pagesC. 30% of The Premium On The Base PolicyPraveen ChaturvediNo ratings yet