Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Uploaded by

Brian FryCopyright:

Available Formats

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Uploaded by

Brian FryCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Uploaded by

Brian FryCopyright:

Available Formats

CME Topic

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Sara B. Fazio,

MD,

and Amy N. Ship,

MD

Abstract: Disorders of the menstrual cycle are common problems in

ambulatory medicine. Abnormal uterine bleeding describes bleeding

that is excessive or outside the normal menstrual cycle. In the premenopausal woman, the differential diagnosis is broad, and pregnancy must

always be considered. Determining whether the bleeding is ovulatory or

anovulatory is a central part of the evaluation, as anovulation is one of

the most common causes of abnormal uterine bleeding. In patients with

anovulatory bleeding, the goal of treatment is to minimize blood loss

and prevent complications from chronic unopposed estrogen. In women

with oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea, after establishing the etiology, it is

necessary to maintain adequate estrogen to support bone health. In the

peri- and postmenopausal population, because the incidence of endometrial hyperplasia and malignancy rises, it is important to have a low

threshold for endometrial assessment.

Key Words: uterine bleeding, anovulation, menorrhagia, oligomenorrhea

isorders of the menstrual cycle are a common problem in

ambulatory medicine, accounting for up to 30% of outpatient visits to gynecologists.1 While there are many terms

used, abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) is the most accurate,

and describes bleeding that is excessive or occurs outside of

normal cyclic menstruation.2 In this article, we describe the

differential diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding, review

the diagnostic workup, define an approach to etiology, and

discuss treatment options for women with uterine bleeding

abnormalities.

The Normal Menstrual Cycle

To understand abnormal uterine bleeding, it is important

to review the normal menstrual cycle. There is tremendous

cycle variability among women. A typical cycle interval varies from 21 to 35 days, with an average duration of blood

flow of two to eight days. Estimated blood loss in a normal

menstrual cycle is between 30 and 80 mL.3 Traditional methFrom the Division of General Internal Medicine, Harvard Medical School,

Boston, MA.

Reprint requests to Sara B. Fazio, MD, Harvard Medical School, Division of

General Internal Medicine E-CC631H, 330 Brookline Avenue, Boston,

MA 02215. Email: sfazio@bidmc.harvard.edu

Drs. Fazio and Ship have no disclosures to declare.

Accepted August 31, 2006.

Copyright 2007 by The Southern Medical Association

0038-4348/02000/10000-0376

376

ods for estimating blood loss have been notoriously inaccurate. The best predictors of heavy bleeding are the passage of

clots, the presence of iron deficiency anemia, and signs of

volume depletion such as orthostasis or tachycardia.

The menstrual cycle is regulated by the pituitary-hypothalamic axis. Pulsatile production of GnRH from the hypothalamus causes secretion of FSH and LH from the pituitary.

Under the influence of FSH, several ovarian follicles begin to

develop. The ovary subsequently produces more estrogen with

this stimulation, which functions as a negative feedback on

FSH, allowing all but one or two dominant follicles to persist.

During this phase, estradiol feedback on the pituitary causes

increase in LH secretion, which causes a small amount of

progesterone production, stimulating an LH surge 34 to 36

hours before follicle rupture and ovulation. Once this occurs,

the ovarian granulose cells produce progesterone for about 14

days but involute thereafter unless pregnancy is established.

Estrogen acts to increase the thickness and vascularity of the

endometrial lining; progesterone increases its glandular secretion and vessel tortuosity. Withdrawal of sex steroids by

involution of the corpus luteum results in endometrial sloughing and menstrual bleeding. The follicular phase (first half of

the cycle) is variable in length. The luteal phase (from the

time of ovulation to menses) is fairly constant at 14 days.

Definitions

Abnormalities in menstrual bleeding are described by a

number of terms, depending on the presence or absence of

blood flow, regularity and amount of blood loss, as well as

etiology (Table 1).

Key Points

Abnormal uterine bleeding is common, and evaluation is best approached by stratifying into pre-, periand postmenopausal status.

In the premenopausal woman, one must determine if

excessive or irregular bleeding is ovulatory or nonovulatory; pregnancy must always be considered in

the differential.

In the peri- and postmenopausal woman, there is an

increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia and malignancy; thus, evaluation should proceed accordingly.

2007 Southern Medical Association

CME Topic

Table 1. Definitions

Amenorrhea no menstrual bleeding for at least 90 days

Menorrhagia excessive or prolonged bleeding at regular intervals.

Technically defined as blood loss 80 cc or bleeding that lasts 7 days

Polymenorrhea Increased frequency of bleeding (interval 21 days)

Oligomenorrhea Decrease in frequency of bleeding (interval 35 days)

Metrorrhagia Irregular interval of bleeding, typically between cycles

Menometrorrhagia prolonged or excessive bleeding both at time of

menstruation and other irregular intervals

Intermenstrual bleeding bleeding that occurs between regular

menstrual cycles

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding excessive endometrial bleeding that is

unrelated to anatomic or systemic disease; classically anovulatory

bleeding, as this is the primary cause

ically, questions regarding temperature intolerance, abnormal

hair growth, galactorrhea and any recent dramatic weight loss

or gain, as these may point to an endocrine etiology. Other

relevant past medical history should be sought, including history of bleeding diathesis, and renal or liver disease.

A thorough physical examination is critical, including a

pelvic examination, even if the patient is actively bleeding. The

focus of the examination is to identify whether there is an alternative source of bleeding (ie, rectum, urethra), to identify suspicious anatomic lesions on the vulva, vagina, or cervix, and to

palpate the uterus for size and tenderness. In addition, the clinician should look for systemic signs, including hirsutism, bruising, and galactorrhea; perform a thyroid examination and, in the

appropriate setting, calculate body mass index (BMI).

Differential Diagnosis and Approach

Pregnancy

The issues raised by abnormal uterine bleeding vary depending on a womans reproductive status. The evaluation of

symptoms is most easily approached by considering whether

a patient is premenopausal, perimenopausal, or postmenopausal. While considerable overlap in etiology may occur,

there are important differences regarding differential diagnosis, evaluation and management in each group.

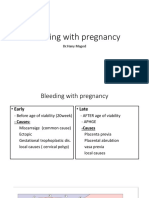

In the premenopausal woman, the differential diagnosis of

abnormal menstrual bleeding is broad. Pregnancy must be considered in any woman of reproductive age; the differential diagnosis of vaginal bleeding differs during pregnancy and includes some diagnoses that can be life-threatening to mother

and/or child (Table 3). Light spotting is common in early pregnancy and may represent implantation. Abdominal cramps may

accompany this, but should be mild and not disabling. Implantation bleeding occurs at approximately 6 to 12 days post ovulation.4 For women who are actively trying to become pregnant

and who know their menstrual history, these symptoms and

appropriate timing suffice to make this diagnosis. Heavy bleeding and/or moderate-to-severe abdominal pain, however, may

indicate ectopic pregnancy. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy

include a history of a previous ectopic pregnancy, history of

pelvic inflammatory disease, prior tubal surgery, cigarette smoking and advanced maternal age, but the vast majority of time,

ectopic pregnancies are spontaneous, with no history of risk

factors; thus, this diagnosis must always be considered.5

In a woman who is known to be pregnant, vaginal bleeding

may indicate spontaneous abortion threatened, complete, or

missed. Placenta previa may present with vaginal bleeding, as

can impending placental abruption. Finally, bleeding may occur

after a therapeutic abortion, and represent retained products of

conception.

The Premenopausal Woman: Excessive or

Irregular Bleeding

In all women, it is important to take a thorough history to

differentiate between various etiologies of bleeding (Table 2).

Questions should elicit information about the timing, duration

and amount of bleeding. A sexual history should be obtained,

with specific attention to the possibility of trauma or domestic

violence. Associated symptoms, such as abdominal pain, vaginal discharge, and fever are important to investigate. A focused review of symptoms is recommended as well, specifTable 2. Bleeding patterns

Intermenstrual bleeding

Benign growths (cervical/endometrial polyps, ectropion, fibroids)

Cancer (uterine, cervical, vulvar, vaginal)

Drugs (oral contraceptives, hormone replacement)

Infection (ulcerations, vaginitis, cervicitis, endometritis)

Intrauterine device (IUD)

Pregnancy

Trauma

Menorrhagia

Benign structural lesions (fibroids, endometrial polyps)

Cancer (endometrial carcinoma, uterine sarcoma)

Coagulopathies (von Willebrand disease, thrombocytopenia, leukemia,

anticoagulants)

Endometrial hyperplasia

Other (hypothyroidism, hyperestrogenemic state (ie, renal/liver

disease), IUD, pregnancy)

Southern Medical Journal Volume 100, Number 4, April 2007

Anovulation

Anovulation is one of the most common causes of abnormal

bleeding. Estrogen is produced by the effect of FSH on the

ovary, but since ovulation never occurs, no progesterone is produced and the uterine lining begins to build up. Over time, this

results in sporadic loss of the endometrial lining. This creates

either extended periods of vaginal bleeding or episodic menstruation at shorter-than-expected intervals (ie, every two weeks),

and eventually results in endometrial hyperplasia. Anovulation

is common during adolescence and at perimenopause.6 In adolescent girls, this is due to a delay in the maturation of the

377

Fazio and Ship Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

precede the development of overt amenorrhea.8 Endocrine etihypothalamic pituitary axis. In the perimenopausal period,

ologies must also be kept in mind in the differential diagnosis of

cyclic hormone production becomes disturbed, and ovulation

anovulatory bleeding. An increase in prolactin either because of

occurs intermittently, interspersed with anovulatory cycles.

a structural pituitary lesion or as a side effect of a medication

As a result, irregular heavy bleeding can occur during longer

(eg, neuroleptic) will cause anovulation. Menorrhagia is often

periods of anovulation.

reported in women with subclinical and overt hypothyroidism.

The most common cause of chronic anovulation in reproCushing syndrome commonly causes menstrual irregularities,

ductive-aged women is polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS).

likely secondary to suppression of GnRH by hypercortisolemia.

Revised criteria for this diagnosis mandate that two of the following be present: oligomenorrhea or anovulation, clinical or

laboratory evidence of androgen excess and polycystic ovaries

Uterine Disease

on ultrasound.7 Ultrasound findings are neither necessary nor

An anatomic or structural problem of the uterus or its

sufficient to make the diagnosis. Controversy persists regarding

lining may cause abnormal bleeding. Uterine fibroids or

the mechanism of disease. The syndrome is felt to be due to

leiomyomata are the most common solid pelvic tumors in

abnormal stimulation of the theca cells by leuteinizing hormone

women, occurring in approximately 20% of women age 35

(LH), which causes them to produce excess androgens, some of

and older.9 They most commonly lead to regular but heavy

which are in turn converted to estrogens. The amount of LH

menstrual cycles (menorrhaproduced exceeds FSH producgia), but may also present as

tion; thus, androgens are prointermenstrual bleeding. Intraduced preferentially to estrogen Differential diagnosis of abnormal menstrual

mural and submucosal fibroids

by the ovary. It is clear that there bleeding in premenopausal women:

may distort the endometrium

is an increased pulse frequency

enough to cause menorrhagia

of GnRH production in PCOS,

1. Pregnancy

in one third of women.10 Other

which is thought to be the reaa. Ectopic pregnancy

benign uterine growths in the

son for LH excess. As a result of

b. Spontaneous abortion

differential include adenomyothese biochemical changes, no

c. Placenta previa abruption

sis (endometrial glands infilovulation occurs. Because of the

2. Polycystic ovarian syndrome

trating the myometrial wall),

constant endometrial stimulation

3. Hypothalamic dysfunction (stress, systemic illness,

endometrial polyps (a common

with estrogen, irregular breaksudden weight changes)

cause of peri- and postmenothrough bleeding can occur, as

4. Endocrine dysfunction (hypothyroidism, elevated

pausal bleeding), and endomewell as endometrial hyperplasia.

prolactin, Cushing disease)

trial hyperplasia. EndometrioWhile PCOS has commonly

5. Uterine disease (fibroids)

sis, a disorder involving

been associated with obesity,

6. Cervical disease

ectopic endometrial tissue outmany women have a normal

7. Vaginal/vulvar disease

side the uterine cavity, is assoBMI; thus, clinicians must con8. Medications (oral contraceptives)

ciated with pelvic pain, dyspasider the diagnosis in all women

9. Systemic illness (von Willebrand disease, coagulopareunia, dysmenorrhea, and

with irregular bleeding.

thy, thrombocytopenia)

abnormal bleeding. Malignant

Anovulation occurs in a vauterine disease is uncommon in

riety of other settings, such as at

the premenopausal population,

times of stress or systemic illness, and with sudden weight

but must still be considered in the differential, particularly in

changes. Such conditions are often classified broadly as hypowomen with risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia, such as

thalamic dysfunction, where a pattern of irregular bleeding may

prolonged unopposed estrogen and tamoxifen use. Endome-

Table 3. Differential diagnosis of bleeding during

pregnancy

Implantation

Ectopic pregnancy

Threatened/complete/incomplete/therapeutic abortion

Molar pregnancy

Placenta previa

Placental abruption

Uterine rupture

378

trial cancer is the most common female genital tract malignancy, and abnormal vaginal bleeding is the most frequent

symptom.11 In contrast, uterine sarcomas represent only a

small percentage of uterine tumors.12 Their usual presentation

is that of abnormal bleeding, or as a rapidly growing fibroid.

Intrauterine devices (IUDs) frequently produce abnormal

uterine bleeding. Endometritis, which is an infection of the

uterine lining, can cause intermenstrual bleeding, and is most

often associated with pregnancy. It is a common complication

associated with a cesarean section, but may also occur after a

spontaneous vaginal delivery, a spontaneous or therapeutic

abortion, as well as IUD insertion.

2007 Southern Medical Association

CME Topic

Cervical Disease

Most cervical etiologies are associated with light intermenstrual bleeding. Cervicitis is caused by a variety of infectious organisms, including Neisseria gonorrhea, Chlamydia trachomatis, Trichomonas vaginalis, or herpes simplex

(HSV) infection. Cervical polyps are benign growths that

commonly cause postcoital bleeding. Ectropian, or endocervical glandular tissue on the exocervix, may also be associated with postcoital bleeding. Cervical cancer commonly presents with abnormal vaginal bleeding.13 Diagnosis of this critical

finding is often delayed because clinicians delay or avoid the

necessary Pap smear because the patient is bleeding.

As previously noted, a variety of endocrine disorders are

associated with anovulation. Cirrhosis can cause excessive

bleeding as it reduces the ability of the liver to metabolize

estrogen, and also decreases production of coagulation factors. Renal failure may have similar consequences because of

interference with the normal excretion of estrogen and progesterone, as well as secondary to abnormal platelet function.

Evaluation

All women who present with abnormal vaginal bleeding

should have a pregnancy test and a complete blood count. If

a recent Pap smear (within the past year) has not been performed, this also should be done. Any suspicious lesions

should be referred for biopsy. If there is a suspicion for cerVaginal/Vulvar Disease

vicitis, cervical cultures should be obtained. In the premenoVaginal or vulvar disease may also be associated with

pausal population, ovulatory status helps to determine subseintermenstrual bleeding. Etiologies include vaginitis/vulvitis,

quent evaluation. There are a variety of methods to ascertain

sexually transmitted disease (eg, syphilitic chancre, HSV simovulatory status. Ovulatory cycles tend to be regular, with the

plex infection, chancroid), or vaginal/vulvar cancer. External

presence of premenstrual symptoms, such as breast tenderor internal trauma should also be considered. Bleeding may

ness, water weight gain, abdominal cramping, mood swings,

occur with intercourse, sexual abuse, foreign bodies (ie, tamand cervical mucous changes.

pons, adult toys), or accidental

Basal body temperature (BBT)

injury.

and serum progesterone conDifferential diagnosis of abnormal menstrual

centrations are two other ways

Medications

bleeding in perimenopausal women:

in which the presence of ovuSeveral medications are

1. Pregnancy

lation can be detected. BBT inassociated with abnormal

2. Anovulation

creases by 0.5 degrees with

menstrual bleeding. Oral con3. Fibroids

ovulation. Serum progesterone

traceptives commonly cause

4. Endometrial disease

concentrations 4.0 to 6.0

breakthrough (intermenstrual)

mIU/mL

(normal luteal phase

bleeding, reflecting endome6

25

mIU/mL)

in the second

trial adjustment to a thinner

half

of

the

cycle

is

consistent

with

luteinization

(ovulation has

state. This is a larger problem with lower estrogen prepara3

occurred).

Unfortunately,

none

of

these

objective

methods

tions, since estrogen serves to stabilize the endometrium. It is

are entirely accurate, because a woman may be ovulating intermore prevalent in smokers, secondary to increased metabomittently, thus it depends on when the assessment is done. Prolism of estrogen in this population. Progestin-only containing

longed bleeding that occurs at irregular intervals following sevcontraceptives frequently cause breakthrough bleeding. Simeral months of amenorrhea is likely anovulatory. Anovulatory

ilarly, medroxyprogesterone acetate injection is commonly

bleeding is also suggested by the suspicion of any of the comassociated with prolonged and irregular spotting. Hormone

replacement therapy in the postmenopausal population is also

monly associated conditions (eg, stress, systemic illness, thyroid

commonly associated with irregular bleeding, particularly

disease, sudden weight loss, PCOS, etc.).

when taken in continuous form. Other medications include

If anovulatory cycles are suspected, thyroid function and

those that cause a relative prolactin excess, such as phea prolactin level should be obtained. In an adolescent with

nothiazines, as they induce anovulatory cycles. Anticoaguheavy bleeding, screening for a coagulopathy is important.

lants may also be associated with increased menstrual loss.

Patients should be assessed via history for a hypothalamic

disorder (stress, eating disorder, excessive exercise). In patients with hirsutism or other signs of androgen excess, evalSystemic Illness

uation should be directed toward the possible diagnosis of

A variety of illnesses may be associated with abnormal

PCOS versus chronic anovulation secondary to an alternative

vaginal bleeding. Disorders of hemostasis, such as a coaguhyperandrogenic state. An LH/FSH ratio 2:1 is highly suglopathy or thrombocytopenia, must always be considered.

gestive of a diagnosis of PCOS, but is not a sensitive finding.

Adolescents with heavy menstrual bleeding should be

A DHEA-S level should be obtained to evaluate for adrenal

screened for partial von Willebrand disease, as this is a fairly

sources of androgen excess, and a serum testosterone level,

common means of presentation. Up to 20% of adolescents

preferably early in the cycle, to evaluate for ovarian sources.

with menorrhagia have a bleeding disorder.6

Southern Medical Journal Volume 100, Number 4, April 2007

379

Fazio and Ship Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

In the case of heavy ovulatory bleeding (menorrhagia),

evaluation should include a complete blood count and coagulation tests, as well as a transvaginal pelvic ultrasound to

evaluate for a structural problem. Leiomyomas (fibroids) are

the most common structural etiology of abnormal bleeding in

the premenopausal population. Submucosal or large fibroids

are more likely to present in this fashion,14 though a myoma

of any size or location may cause bleeding. Recent evidence

suggests that the cause of bleeding may be most highly correlated with growth factor dysregulation causing abnormalities in the vasculature.15 A transvaginal ultrasound is particularly helpful in delineating the position and size of fibroids,

endometrial thickness, and occasionally, the presence of endometrial polyps. A sonohysterogram, which involves instillation of saline into the uterine cavity during a transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasound, may be necessary to better

delineate the position and size of intrauterine pathology. It is

particularly useful in identifying structural lesions of the endometrial cavity that can be hidden within the endometrial

stripe of premenopausal women. Its use is limited by the fact

that it is an uncomfortable procedure for the patient. Referral

for endometrial biopsy, hysteroscopy, or dilation and curettage (D & C) may be warranted in patients over the age of 35

in whom the bleeding cannot be controlled, or those with risk

factors for endometrial hyperplasia/carcinoma, including a

positive family history, prolonged anovulation (typically defined as greater than one year), and obesity.3,8

Treatment

In ovulatory bleeding, NSAIDs are helpful in controlling

menorrhagia by modulating PGE2 and PGI2, two vasodilating prostaglandins. By inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis,

the amount of bleeding decreases by approximately 30%.16

NSAIDs may also be very helpful if dysmenorrhea exists.

Oral contraceptives are also effective in modulating blood

loss, on average providing a 50% decrease.17 Progestin-containing IUDs have been found to be effective as well, decreasing menstrual blood flow by 80 to 90%.17 Given concerns about impaired fertility, they are more appropriate for

women who have completed childbearing. Tranexamic acid

is an option for more severe cases, functioning as a plasminogen activator inhibitor. Studies have demonstrated a reduction in blood loss by 34 to 59%, with no evidence that the

treatment increases the risk of thromboembolic disease.18

For anovulatory bleeding disorders, the etiology of the

anovulation must be addressed eg, correct any underlying

thyroid disease, advise the patient regarding weight loss or

gain, and discontinue any offending medications. However,

in many cases, an etiology is not found. When there is no

identifiable cause for anovulatory bleeding, the disorder is

called dysfunctional uterine bleeding or DUB. This is a

diagnosis of exclusion and can usually be treated medically.

Empiric treatment begins with oral contraceptives or cy-

380

clic progesterone. Oral contraceptives provide added protection against pregnancy in women who intermittently ovulate.

For women who have not had a menstrual period for more

than six weeks, it may be advisable to induce a withdrawal

bleed first with medroxyprogesterone acetate to minimize the

amount of breakthrough bleeding. For moderate bleeding that

can be managed on an outpatient basis, a monophasic oral

contraceptive may be prescribed for q.i.d. dosing for five to

seven days, and subsequently reduced to daily dosing for

three weeks, followed by a withdrawal bleed. Alternatively, a

progestational agent such as medroxyprogesterone acetate or

norethindrone can be given for 10 to 21 days. Subsequently,

a normal regimen of oral contraceptives can be started with

the next cycle. Women with ovulatory bleeding are less likely

to benefit from luteal phase progestins than women with an

anovulatory source.17 If fertility is desired, a progestational

agent may be administered 15 days each month to control the

endometrial lining. In cases of anovulation, clomiphene citrate or pulsatile GnRH agonists may be administered by a

gynecologist to induce ovulation.

For very heavy menstrual bleeding, a variety of hormonal options exist. Parenteral conjugated estrogens are approximately 70% effective in stopping the bleeding entirely.17

In women in whom estrogen is contraindicated, such as those

with underlying liver disease, medroxyprogesterone acetate

may be substituted. GnRH antagonists such as leuprolide,

administered continuously, will induce a reversible chemical

menopause by downregulation of GnRH receptors and consequent diminished gonadotropin secretion. Danazol, a synthetic steroid with strong antigonadotropin properties as well

as direct inhibitory effects at receptors of gonadal steroids,

has also been shown to be effective. Between 50 and 100% of

patients will experience a decline in blood loss, depending on

the dose.16,17 Androgenic side effects may be limiting, which

include hirsutism, weight gain, and acne. Surgical options are

reserved for cases when medical treatment fails, and are necessary in approximately 10% of cases.8 Options include hysteroscopic endometrial ablation, where selective areas of endometrium are destroyed, nonhysteroscopic (or blind)

ablation, or hysterectomy.

The Premenopausal Woman:

Oligomenorrhea and Amenorrhea

Oligomenorrhea refers to bleeding that is infrequent or

scant. Technically, it is defined as bleeding that occurs at

intervals greater than 35 days apart, or fewer than nine menstrual cycles a year.6 It may progress to amenorrhea, which is

an absence of bleeding for at least three months in a woman

with previously normal cycles or nine months in a woman

with a history of oligomenorrhea.19 As usual, pregnancy must

be considered in the differential, as well as anovulatory states

as previously outlined. In particular, patients with PCOS frequently experience oligomenorrhea. It is also important to

2007 Southern Medical Association

CME Topic

consider conditions which are primarily associated with low

The irregularity of bleeding that precedes menopause is due

circulating estrogen levels, such as exercise-induced amento intermittent anovulation. As with any woman who presents

orrhea, anorexia nervosa, and premature menopause.

with irregular bleeding, a focused history, physical examinaSimilar to the evaluation of anovulatory bleeding, all

tion, complete blood count, and thyroid testing is indicated.

patients should have a UCG, TSH and prolactin level meaEven if the patient is closer to 51 (the average age of menosured. If there are signs of hyperandrogenism, DHEA-S and

pause) a pregnancy test should still be performed, as untestosterone should be checked. If all are normal, one may

planned pregnancies are not uncommon in this population,

determine if the patient has adequate circulating levels of

likely because women believe they are no longer fertile and

estrogen with a progesterone withdrawal test. The patient

thus do not always use contraception.

receives 10 mg of a progestin (usually medroxyprogestone

Since chronic anovulation can lead to prolonged periods of

acetate) for 5 to 10 days. On discontinuation, if adequate

unopposed estrogen and an increased risk of endometrial hyperestrogen is present, there should be a withdrawal bleed. Abplasia, the clinician should have a low threshold for endometrial

sence of a withdrawal bleed suggests a hypoestrogenic state

assessment in this population. Irregular bleeding of less than 3

(ie, primary or secondary ovarian failure). Alternatively, in a

months duration without an episode of menorrhagia can be

woman with previously normal cycles, many gynecologists

followed clinically. Irregular bleeding of more than 6 months

will measure FSH, LH and estradiol levels. A high serum

duration, an episode of menorrhagia, or cycle length of less than

FSH indicates ovarian failure. A low nor17 to 19 days is generally an indication for

mal serum FSH is common in women with

endometrial surveillance. The most common

hypothalamic amenorrhea. Typically in this

method of assessment is via office-based enThe most worrisome

scenario, FSH is higher than LH. Head imdometrial biopsy, where a Pipelle is introaging is indicated when no clear etiology of source of bleeding in the duced into the cervix and endometrial samhypothalamic amenorrhea is obvious to rule postmenopausal woman ples are obtained. Typically, several passes of

out pituitary or hypothalamic disease.

the Pipelle are performed with an attempt to

is endometrial cancer,

Exercise-associated amenorrhea (EAA)

obtain tissue from the entire uterus, but the

with a risk of

is a frequent cause of amenorrhea in young

procedure is done blindly. Endometrial biopsy

approximately 10% in

women, most commonly seen in runners and

is slightly less accurate in the perimenopausal

women not on hormone population than the postmenopausal populaballet dancers, but not limited to any one sport.

Disordered eating is common in the young

tion in detecting endometrial hyperplasia and

replacement therapy.

female population, and is especially common

carcinoma, with detection rates of 91% in periThe

most

common

among athletes.20 Excessive exercise and

menopausal women compared with 99% in

sources of bleeding in

weight loss can suppress GnRH release from

postmenopausal women.24 The utility of a

this

age

group

are

the hypothalamus, causing oligomenorrhea.

transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) as a means of

atrophic vaginitis,

Among other health hazards, low estrogen

deferring endometrial biopsy is not well studendometrial atrophy,

levels increase the risk for osteoporosis. Traied in this population. Several small studies

becular bone (hip, spine and femur) reaches

and endometrial polyps. have demonstrated a high negative predictive

peak density in the mid 20s. After this time,

value using an endometrial stripe less than 5

bone density in healthy individuals decreases

to 7 mm,2527 with one study demonstrating

at a rate of approximately 1% per year. Bone

greater sensitivity of TVU in detecting abnordensity has been found to be decreased 22 to 29% in young

malities outside the endometrium. Thus, initial assessment

amenorrheic women compared with age-matched controls.21 Adshould likely include TVU in the perimenopausal population. If

ditional research has shown that current menstrual status as well

the endometrial stripe is less than 4 to 5 mm, and the endomeas a past history of menstrual abnormalities are both important in

trium shows no areas of heterogeneity, some gynecologists will

determining decreased bone density.22 For example, in athletes

defer biopsy. In the presence of ongoing bleeding or risk factors for

who regain normal menstrual cycles, bone density rises, but not

endometrial cancer (family history, obesity, chronic anovulation,

to the level of normal controls. Thus, it is critically important to

tamoxifen use), however, a biopsy is necessary.

begin estrogen replacement, typically in the form of oral conIn a woman under the age of 45 with no risk factors for

traceptives, in a woman who has had six months of a hypoestroendometrial cancer, it may be appropriate to initiate a trial of

genemic state.23

low-dose oral contraceptives to regulate bleeding. Alternatively, cyclic progestin may be administered to induce

monthly withdrawal bleeding.

The Perimenopausal Woman

Abnormal perimenopausal bleeding presents unique challenges to the clinician, as most women will experience a

The Postmenopausal Woman

change in regularity of their bleeding pattern before they

The most worrisome source of bleeding in the postmenoexperience the year of amenorrhea that defines menopause.

pausal woman is endometrial cancer, but it is not, in fact, the

Southern Medical Journal Volume 100, Number 4, April 2007

381

Fazio and Ship Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

most common source. The risk of endometrial cancer in a

postmenopausal woman not on HRT is approximately 10%.28

Atrophic vaginitis, endometrial atrophy, and endometrial polyps

are the most common findings. Endometrial biopsy has long

been the gold standard for diagnosis, but it is an uncomfortable

procedure for an older patient, especially if cervical stenosis is

present. In approximately 2 to 28% of attempts, the biopsy cannot be performed or yields nondiagnostic results.28 In addition,

office-based endometrial biopsy has a false negative rate of up to

5 to 15%.28 At a threshold of 5 mm, transvaginal ultrasound

(TVU) has a high sensitivity for detecting endometrial carcinoma in this population (90%), and has been shown to have a

99% negative predictive value in ruling out serious endometrial

disease.29 While many gynecologists use these data to avoid

unnecessary biopsies, there is some data to suggest that a small

percentage of malignancies would be missed using this cutoff30; therefore, in the presence of continued bleeding, a tissue

diagnosis with office-based biopsy or dilation and curettage under anesthesia is always warranted.

In the circumstance of a postmenopausal woman who

takes continuous hormone replacement therapy, it is not uncommon to have abnormal bleeding for the first 6 months of

treatment. However, if bleeding continues or starts after that

interval, endometrial biopsy is necessary.

Summary

Abnormal uterine bleeding is a common condition, and

evaluation is best approached by stratifying into pre-, periand postmenopausal status. In premenopausal women, after

pregnancy has been excluded, ovulatory versus nonovulatory

bleeding is the most important branch point. Utilizing a systematic approach to the differential diagnosis will help to

avoid a misdiagnosis. Much of the evaluation and treatment

can be done in the office of the internist. In patients with

anovulatory bleeding, the goal of treatment is to regulate

cycles, minimize blood loss, and prevent complications from

chronic unopposed estrogen. In the patient with oligomenorrhea, it is important to maintain adequate estrogen to support

bone health. In the peri- and postmenopausal populations, the

incidence of endometrial hyperplasia and malignancy rises;

thus, it is important to have a low threshold for endometrial

assessment and referral to a gynecological specialist.

References

1. Wren BG. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Aust Fam Physician 1998;

27:371377.

2. Obstetrics AoPoGa. Clinical management of abnormal uterine bleeding.

In: Smith RP BL, Ke RW, Strickland JL, ed. APGO Educational Series

on Womens Health, 2002.

3. Bayer SR, DeCherney AH. Clinical manifestations and treatment of

dysfunctional uterine bleeding. JAMA 1993;269:18231828.

4. Implantation embryogenesis, and placental development. In: Cunningham

G, Grant NF, Leveno KJ, et al, ed. Williams Obstetrics. New York,

McGraw Hill, 2005.

5. Seeber BE, Barnhart KT. Suspected ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol

2006;107:399413.

382

6. Oriel KA, Schrager S. Abnormal uterine bleeding. Am Fam Physician

1999;60:13711380; discussion 13811382.

7. Ehrmann DA. Polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med 2005;352:

12231236.

8. ACOG Committee on Practice BulletinsGynecology. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin: management of anovulatory bleeding. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2001;72:263271.

9. Ryden J, Blumenthal PD, ed. Practical Gynecology: A Guide for the

Primary Care Physician (Womens Health Series). Philadelphia, American College of Physicians, 1998.

10. Uterine leiomyomata. Number 192May 1994. ACOG technical bulletin. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 1994;46:7382.

11. Amant F, Moerman P, Neven P, et al. Endometrial cancer. Lancet 2005;

366:491505.

12. Platz CE, Benda JA. Female genital tract cancer. Cancer 1995;75 (1

Suppl):270294.

13. Pretorius R, Semrad N, Watring W, et al. Presentation of cervical cancer.

Gynecol Oncol 1991;42:4853.

14. Stewart EA. Uterine fibroids. Lancet 2001;357:293298.

15. Ryan GL, Syrop CH, Van Voorhis BJ. Role, epidemiology, and natural

history of benign uterine mass lesions. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2005;48:312

324.

16. Stabinsky SA, Einstein M, Breen JL. Modern treatments of menorrhagia

attributable to dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol Surv 1999;

54:6172.

17. Munro MG. Dysfunctional uterine bleeding: advances in diagnosis and

treatment. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2001;13:475489.

18. Wellington K, Wagstaff AJ. Tranexamic acid: a review of its use in the

management of menorrhagia. Drugs 2003;63:14171433.

19. Master-Hunter T, Heiman DL. Amenorrhea: evaluation and treatment.

Am Fam Physician 2006;73:13741382.

20. Holschen JC. The female athlete. South Med J 2004;97:852858.

21. Cann CE, Martin MC, Genant HK, et al. Decreased spinal mineral

content in amenorrheic women. JAMA 1984;251:626629.

22. Drinkwater BL, Nilson K, Chesnut CH 3rd, et al. Bone mineral content of

amenorrheic and eumenorrheic athletes. N Engl J Med 1984;311:277281.

23. Davis A. A 21-year-old woman with menstrual irregularity. JAMA 1997;

277:13081314.

24. Dijkhuizen FP, Mol BW, Brolmann HA, et al. The accuracy of endometrial sampling in the diagnosis of patients with endometrial carcinoma

and hyperplasia: a meta-analysis. Cancer 2000;89:17651772.

25. Taipale P, Tarjanne H, Heinonen UM. The diagnostic value of transvaginal

sonography in the diagnosis of endometrial malignancy in women with periand postmenopausal bleeding. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1994;73:819823.

26. Dubinsky TJ, Parvey HR, Maklad N. The role of transvaginal sonography and endometrial biopsy in the evaluation of peri- and postmenopausal bleeding. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1997;169:145149.

27. Tongsong T, Pongnarisorn C, Mahanuphap P. Use of vaginosonographic

measurements of endometrial thickness in the identification of abnormal

endometrium in peri- and postmenopausal bleeding. J Clin Ultrasound

1994;22:479482.

28. Smith-Bindman R, Kerlikowske K, Feldstein VA, et al. Endovaginal

ultrasound to exclude endometrial cancer and other endometrial abnormalities. JAMA 1998;280:15101517.

29. Langer RD, Pierce JJ, OHanlan KA, et al. Transvaginal ultrasonography compared with endometrial biopsy for the detection of endometrial

disease. Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions Trial. N Engl

J Med 1997;337:17921798.

30. Tabor A, Watt HC, Wald NJ. Endometrial thickness as a test for endometrial cancer in women with postmenopausal vaginal bleeding. Obstet

Gynecol 2002;99:663670.

2007 Southern Medical Association

You might also like

- 1 Principles PDFDocument24 pages1 Principles PDFCHANDRA BHUSHANNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine BleedingDocument5 pagesAbnormal Uterine Bleedingwuryan dewiNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine Bleeding, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandAbnormal Uterine Bleeding, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- Menopause Semester 6 (IMTU)Document37 pagesMenopause Semester 6 (IMTU)nyangaraNo ratings yet

- Antenatal Care (ANC)Document77 pagesAntenatal Care (ANC)tareNo ratings yet

- APHDocument40 pagesAPHJayarani AshokNo ratings yet

- RH DiseaseDocument9 pagesRH DiseaseYerra SukumalaNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Copy of Fourth Year BSCDocument52 pagesSyllabus Copy of Fourth Year BSCBappaditta KarNo ratings yet

- RH. Lesson PlanDocument14 pagesRH. Lesson PlanNithiya NadesanNo ratings yet

- Polycystic Ovary Syndrome: Dr. Rizwana ShaheenDocument34 pagesPolycystic Ovary Syndrome: Dr. Rizwana ShaheenAmaan Hakim100% (1)

- FEOTAL MEASURE Clinical ParametersDocument13 pagesFEOTAL MEASURE Clinical Parameterssuman guptaNo ratings yet

- Endometriosis Case Presentation by Nkoro Edward-1Document27 pagesEndometriosis Case Presentation by Nkoro Edward-1Brie IpehNo ratings yet

- Labor and Delivery: By: Ma. Kizianne Krystel ManioDocument43 pagesLabor and Delivery: By: Ma. Kizianne Krystel ManioJohn Christian LasalitaNo ratings yet

- Trial of LabourDocument2 pagesTrial of Labourgeorgeloto12100% (1)

- I.U.G.R.: Presented byDocument49 pagesI.U.G.R.: Presented byOjer QuayNo ratings yet

- Recurrent Pregnancy LossDocument61 pagesRecurrent Pregnancy LossHerman Fira100% (1)

- Antenatal Assessment of Fetal Well-BeingDocument18 pagesAntenatal Assessment of Fetal Well-BeingAmritaNo ratings yet

- Endometrial BiopsyDocument72 pagesEndometrial BiopsySatish TatamiyaNo ratings yet

- MenorrhagiaDocument3 pagesMenorrhagiajermie22100% (1)

- CordocentesisDocument6 pagesCordocentesisAyna Salic Pangarungan100% (1)

- AmniocentesisDocument46 pagesAmniocentesisErika ArbolerasNo ratings yet

- Cephalopelvic DisproportionDocument15 pagesCephalopelvic DisproportionPriscilla Sarah PayneNo ratings yet

- AbortionDocument66 pagesAbortionGunu SinghNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine ActionDocument110 pagesAbnormal Uterine ActionAnnapurna DangetiNo ratings yet

- Hiv in PregnancyDocument8 pagesHiv in Pregnancyjh6svdhxmxNo ratings yet

- Malformation of Female Reproductive SystemDocument170 pagesMalformation of Female Reproductive SystemKriti BanstolaNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy 33Document36 pagesHypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy 33Asteway MesfinNo ratings yet

- 3&4 MiscarraigeDocument90 pages3&4 MiscarraigeAbdullah Gad100% (1)

- Hypertensive Disorders in PregnancyDocument40 pagesHypertensive Disorders in PregnancyEzz Aldeen Bani Yaseen100% (1)

- Polyhydramnios 10Document4 pagesPolyhydramnios 10hussain AltaherNo ratings yet

- Before Starting The Presentation, I Am Requesting You All To Get A HandkerchiefDocument35 pagesBefore Starting The Presentation, I Am Requesting You All To Get A HandkerchiefOng KarlNo ratings yet

- Session 1 - PuerperiumDocument66 pagesSession 1 - PuerperiumCHALIE MEQUNo ratings yet

- Rhesus Iso ImmunizationDocument12 pagesRhesus Iso Immunizationapi-3705046No ratings yet

- Diabetes in PregnancyDocument11 pagesDiabetes in PregnancyAlana CaballeroNo ratings yet

- Diseases of The Female Genital TractDocument4 pagesDiseases of The Female Genital Tractsarguss14No ratings yet

- Hepatitis B in PregnancyDocument17 pagesHepatitis B in PregnancysnazzyNo ratings yet

- 001hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy PDFDocument23 pages001hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy PDFRosechelle Bas SamsonNo ratings yet

- Hypertensive Disorder in PregnancyDocument56 pagesHypertensive Disorder in PregnancyESCA Gabriel100% (1)

- Ethical Issues in Assisted Reproductive Technologies ART 2Document49 pagesEthical Issues in Assisted Reproductive Technologies ART 2Pavan chowdaryNo ratings yet

- HELLP SyndromeDocument3 pagesHELLP SyndromeWidyawati TjahjadiNo ratings yet

- Constriction Ring Pathological RingDocument13 pagesConstriction Ring Pathological RingVarna MohanNo ratings yet

- 2 Congenital AbnormalitiesDocument14 pages2 Congenital AbnormalitiesSamba SukanyaNo ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine Bleeding: - Rou'a Eyad - Rahaf EyadDocument35 pagesAbnormal Uterine Bleeding: - Rou'a Eyad - Rahaf EyadYazeed Asrawi0% (1)

- Psychological and Social Aspect of MenopauseDocument16 pagesPsychological and Social Aspect of MenopauseFarheen khanNo ratings yet

- HIV and PregnancyDocument9 pagesHIV and PregnancyUm HamoOdNo ratings yet

- Up Dated Respectiful Maternity Care (RMC)Document21 pagesUp Dated Respectiful Maternity Care (RMC)nyangaraNo ratings yet

- Post Partum Complications I - IIDocument32 pagesPost Partum Complications I - IIkurt94764No ratings yet

- AUBDocument45 pagesAUBJBNo ratings yet

- Malpresentation and Malposition - PostmaturityDocument29 pagesMalpresentation and Malposition - PostmaturityNishaThakuri100% (1)

- AUB CompiledDocument72 pagesAUB CompiledDinesha PaniselvamNo ratings yet

- AbortionDocument19 pagesAbortionGomez VanessaNo ratings yet

- 63 Shock in Obstetrics & GynecologyDocument29 pages63 Shock in Obstetrics & GynecologyGodsonYeboah-AwudziNo ratings yet

- Seva Mandal Education Society College of Nusing Subject: Midwifery and Obstetrical Nursing Seminar ONDocument21 pagesSeva Mandal Education Society College of Nusing Subject: Midwifery and Obstetrical Nursing Seminar ONshraddha singhNo ratings yet

- 29 - Abnormal Uterine ActionDocument31 pages29 - Abnormal Uterine Actiondr_asaleh94% (18)

- E Lert OT LarmedDocument54 pagesE Lert OT LarmedJetty Elizabeth JoseNo ratings yet

- Deep Vein Thrombosis in Pregnancy - Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Diagnosis - UpToDateDocument26 pagesDeep Vein Thrombosis in Pregnancy - Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Diagnosis - UpToDateCristinaCaprosNo ratings yet

- Thrombo Embolism and PregnancyDocument9 pagesThrombo Embolism and Pregnancysangeetha francisNo ratings yet

- Prenatal Care by Connie Sussan AustenDocument31 pagesPrenatal Care by Connie Sussan AustenNoraNo ratings yet

- Case Presentation CPD New 1.1Document57 pagesCase Presentation CPD New 1.1merapi mountainNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Fetal WellbeingDocument24 pagesAssessment of Fetal WellbeingMukesh ThakurNo ratings yet

- Induced AbortionDocument8 pagesInduced AbortionClint FloresNo ratings yet

- EIA Oxidation Pond JUDocument71 pagesEIA Oxidation Pond JUnot now100% (1)

- Assessment in SchoolsDocument169 pagesAssessment in SchoolsCletus Batton100% (1)

- CH 3 PDFDocument80 pagesCH 3 PDFmuhammad saeedNo ratings yet

- Treatment Plan For Intellectual Development DisorderDocument3 pagesTreatment Plan For Intellectual Development DisorderKristina Casandra PalomataNo ratings yet

- Praying As Agents - Notes - Elder Brian L RawsonDocument4 pagesPraying As Agents - Notes - Elder Brian L Rawsonhunter100% (1)

- Modal Verbs For Suggestion and AdviceDocument4 pagesModal Verbs For Suggestion and AdvicePrada NaNo ratings yet

- University of Utah Unofficial TranscriptDocument6 pagesUniversity of Utah Unofficial Transcriptapi-285174624No ratings yet

- Ministry of Electricity & EnergyDocument136 pagesMinistry of Electricity & EnergySayed Abo Elkhair100% (1)

- Engineering Management: University of Eastern Philippines Laoang CampusDocument8 pagesEngineering Management: University of Eastern Philippines Laoang CampusJ. Robert TanNo ratings yet

- Yr34 Art Term 1Document4 pagesYr34 Art Term 1api-485205773No ratings yet

- Role of Entrepreneur in Developing CountryDocument40 pagesRole of Entrepreneur in Developing CountryNeeraj AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Brucellosis BmelitensisDocument38 pagesBrucellosis Bmelitensisalvaro acNo ratings yet

- ANAVIA HT-100 Brochure ENDocument11 pagesANAVIA HT-100 Brochure ENrose stwnNo ratings yet

- Reseña SocialDocument8 pagesReseña Social78z8tb2cdhNo ratings yet

- Drug and Alcohol AbuseDocument18 pagesDrug and Alcohol AbuseSanskriti Jain100% (1)

- FS 2-Ep 5Document6 pagesFS 2-Ep 5Mark Warren Atienza Revellame75% (4)

- Ode On A Grecian Urn: John KeatsDocument12 pagesOde On A Grecian Urn: John KeatsSharmin SultanaNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument22 pagesPDFymagNo ratings yet

- 2902851Document9 pages2902851Homer SilvaNo ratings yet

- Minitab Statguide Time SeriesDocument72 pagesMinitab Statguide Time SeriesSuraj singhNo ratings yet

- Mergers and AcquisitionsDocument21 pagesMergers and AcquisitionsEdga WariobaNo ratings yet

- Raymond Design Warehouse OperationsDocument13 pagesRaymond Design Warehouse OperationsAISHWARYA SHENOY K P 2127635No ratings yet

- Hardness TestingDocument6 pagesHardness TestingLegendaryN0% (1)

- (Quiz 2) EntrepDocument31 pages(Quiz 2) EntrepMichael Eian RanilloNo ratings yet

- TDS - J Cart Univ1Document3 pagesTDS - J Cart Univ1นก กาญนพงNo ratings yet

- The Power of Doing Nothing at AllDocument9 pagesThe Power of Doing Nothing at AllPriyo DjatmikoNo ratings yet

- DLP Mathematics 5Document8 pagesDLP Mathematics 5Monna100% (1)

- Political History of Sri LankaDocument3 pagesPolitical History of Sri LankaDon ZameelNo ratings yet

- CoSt AcCOunting Project RePOrtDocument28 pagesCoSt AcCOunting Project RePOrtsabeen ansari0% (1)