Does Oil Hinder Democracy?

Does Oil Hinder Democracy?

Uploaded by

darkzielCopyright:

Available Formats

Does Oil Hinder Democracy?

Does Oil Hinder Democracy?

Uploaded by

darkzielOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Does Oil Hinder Democracy?

Does Oil Hinder Democracy?

Uploaded by

darkzielCopyright:

Available Formats

Does Oil Hinder Democracy?

Ross, Michael Lewin, 1961World Politics, Volume 53, Number 3, April 2001, pp. 325-361 (Article)

Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press

DOI: 10.1353/wp.2001.0011

For additional information about this article

http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/wp/summary/v053/53.3ross.html

Access Provided by Northwestern University Library at 06/17/10 2:20PM GMT

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY?

By MICHAEL L. ROSS*

INTRODUCTION

OLITICAL scientists believe that oil has some very odd properties. Many studies show that when incomes rise, governments tend

to become more democratic. Yet some scholars imply there is an exception to this rule: if rising incomes can be traced to a countrys oil

wealth, they suggest, this democratizing effect will shrink or disappear.

Does oil really have antidemocratic properties? What about other minerals and other commodities? What might explain these effects?

The claim that oil and democracy do not mix is often used by area

specialists to explain why the high-income states of the Arab Middle

East have not become democratic. If oil is truly at fault, this insight

could help explainand perhaps, predictthe political problems of oil

exporters around the world, such as Nigeria, Indonesia, Venezuela, and

the oil-rich states of Central Asia. If other minerals have similar properties, this effect might help account for the absence or weakness of democracy in dozens of additional states in sub-Saharan Africa, Latin

America, and Southeast Asia. Yet the oil impedes democracy claim

has received little attention outside the circle of Mideast scholars;

moreover, it has not been carefully tested with regression analysis, either within or beyond the Middle East.

I use pooled time-series cross-national data from 113 states between

1971 and 1997 to explore three aspects of the oil-impedes-democracy

claim. The first is the claims validity: is it true? Although the claim has

been championed by Mideast specialists, it is difficult to test by examining

only cases from the Middle East because the region provides scholars with

* Previous versions of this article were presented to seminars at Princeton University, Yale University, and the University of California, Los Angeles, and at the September 2000 annual meeting of the

American Political Science Association in Washington, D.C. For their thoughtful comments on earlier drafts, I am grateful to Pradeep Chhibber, Indra de Soysa, Geoffrey Garrett, Phil Keefer, Steve

Knack, Miriam Lowi, Ellen Lust-Okar, Lant Pritchett, Nicholas Sambanis, Jennifer Widner, Michael

Woolcock, and three anonymous reviewers. I owe special thanks to Irfan Nooruddin for his research

assistance and advice and to Colin Xu for his help with the Stata. I wrote this article while I was a visiting scholar at The World Bank in Washington, D.C. The views I express in this article, and all remaining errors, are mine alone.

World Politics 53 (April 2001), 32561

326

WORLD POLITICS

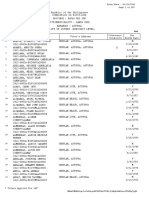

INDEX

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

Brunei (1994)

Kuwait

Bahrain

Nigeria (1991)

Congo, Dem. Rep.

Angola (1996)

Yemen

Oman

Saudi Arabia

Qatar (1994)

Libya (1988)

Iraq (1983)

Algeria

Venezuela

Syria

Norway

Iran (1983)

Ecuador

Malaysia

Indonesia

Cameroon

Lithuania

Kyrgyz Republic (1996)

Netherlands

Colombia

OF

TABLE 1

OIL-RELIANT STATESA

47.58

46.14

45.60

45.38

45.14

45

38.58

38.43

33.85

33.85

29.74

23.48

21.44

18.84

15.00

13.46

11.95

8.53

5.91

5.69

5.63

4.48

4.25

3.14

3.13

a

Oil reliance is measured by the value of fuel-based exports divided by GDP. Most figures

are based on data for 1995 from World Bank (fn. 71).Figures for Brunei, Nigeria, Qatar,

Libya, Iraq, and Iran are the most recent available. Since 1995 figures for Angola and Kyrgyz Republic are not available, 1996 figures are reported.

little variation on the dependent variable: virtually all Mideast governments have been authoritarian since gaining independence. Moreover,

there are other plausible explanations for the absence of democracy in the

Mideast, including the influence of Islam and the regions distinct culture

and colonial history. Does oil have a consistently negative influence on democracy once one accounts for these and other variables?

Second, I examine the claims generality along two dimensions. One

is geographic. For obvious reasons the oil-impedes-democracy claim

has been explored most carefully by Mideast specialists: ten of the fifteen states most reliant on oil wealth are in the Middle East region (see

Table 1). But is oil an obstacle to democracy only in the Mideast, or does

it harm oil exporters everywhere? If the hypothesis is true for all oil-rich

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

INDEX

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

Botswana

Zambia

Bahrain

Chile

Angola (1996)

Papua New Guinea

Togo (1991)

Bolivia

Congo, Dem. Rep. (1983)

Jordan

Peru

Central African Republic

Iceland

Zimbabwe

Norway

Belgium

Canada

Australia

Lithuania

Jamaica

Slovak Republic

South Africa

Morocco

Cameroon

Kyrgyz Republic

OF

327

TABLE 2

MINERAL-RELIANT STATESa

35.11

24.97

16.39

12.63

11.5

10.13

7.79

5.53

7.00

5.28

3.84

3.16

3.11

3.00

2.49

2.23

2.22

2.20

1.96

1.87

1.74

1.69

1.65

1.62

1.56

Mineral reliance is measured by the value of nonfuel mineral exports divided by GDP.

Most figures are for 1995 based on data from World Bank (fn. 71). The figures for Congo

and Togo are the most recent available; the 1996 figure is reported for Angola, since no figure for 1995 is available.

states, then its importance has been underappreciated by other political

scientists. If it holds only for states in the Mideast, why is this so?

The other dimension is sectoral: do other types of minerals and

other types of commodities have similar effects on governments? While

oil exporters tend to be concentrated in the Middle East, exporters of

nonfuel minerals are more geographically dispersed (see Table 2). Have

these states, too, been rendered less democratic because of resource

wealth? Or does petroleum have antidemocratic properties that are not

found in other commodities?

Finally, I explore the question of causality: if oil does have antidemocratic effects, what is the causal mechanism? I test three possible

explanations: a rentier effect, which suggests that resource-rich

328

WORLD POLITICS

governments use low tax rates and patronage to relieve pressures for

greater accountability; a repression effect, which argues that resource

wealth retards democratization by enabling governments to boost their

funding for internal security; and a modernization effect, which holds

that growth based on the export of oil and minerals fails to bring about

the social and cultural changes that tend to produce democratic government.

I also have two broader aims. The first is to encourage scholars who

study democracy to incorporate the Middle East into their analyses.

Many global studies of democratization have avoided the Mideast entirely.1 Influential studies by Przeworski and Limongi and Przeworski,

Alvarez, Cheibub, and Limongi simply drop the oil-rich Mideast states

from their database.2 There is, however, no sound analytical reason for

scholars of democracy to exclude these states from their research, and

doing so can only weaken any general findings. It also tends to marginalize the field of Middle East studies.

My second aim is to address the literature on the resource curse.

Many of the poorest and most troubled states in the developing world

have, paradoxically, high levels of natural resource wealth. There is a

growing body of evidence that resource wealth itself may harm a countrys prospects for development. States with greater natural resource

wealth tend to grow more slowly than their resource-poor counterparts.3 They are also more likely to suffer from civil wars.4 This article

suggests as well that there is a third component to the resource curse:

oil and mineral wealth tends to make states less democratic.

1

See, for example, Guillermo ODonnell, Philippe C. Schmitter, and Lawrence Whitehead, eds.,

Transitions from Authoritarian Rule: Prospects for Democracy (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University

Press, 1986); D. Larry Diamond, Juan J. Linz, and Seymour Martin Lipset, eds., Democracy in Developing Countries (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 1988); Ronald Inglehart, Modernization and Postmodernization (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997).

2

Adam Przeworski and Fernando Limongi, Modernization: Theories and Facts, World Politics 49

( January 1997); Adam Przeworski, Michael Alvarez, Jos Antonio Cheibub, and Fernando Limongi,

What Makes Democracies Endure? Journal of Democracy 7 ( January 1996); idem,Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-Being in the World, 19501990 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2000).

3

Jeffrey D. Sachs and Andrew M. Warner, Natural Resource Abundance and Economic Growth,

Development Discussion Paper no. 517a (Cambridge: Harvard Institute for International Development, 1995); idem, The Big Push, Natural Resource Booms and Growth, Journal of Development

Economics 59 (February 1999); Carlos Leite and Jens Weidmann, Does Mother Nature Corrupt? Natural Resources, Corruption, and Economic Growth, IMF Working Paper, WP/99/85 (1999); Michael

L. Ross, The Political Economy of the Resource Curse, World Politics 51 ( January 1999); R. M. Auty,

Resource Abundance and Economic Development (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001).

4

Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler, On Economic Causes of Civil War, Oxford Economic Papers 50

(October 1998); Indra de Soysa, The Resource Curse: Are Civil Wars Driven by Rapacity or

Paucity? in Mats Berdal and David M. Malone, eds., Greed and Grievance: Economic Agendas in Civil

Wars (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 2000).

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

329

I begin by outlining the oil-impedes-democracy claim and the limitations of previous work on the topic. I then draw on earlier case studies of oil-rich states to specify three causal mechanisms that might

explain how oil makes governments more authoritarian. The next section presents a model of regime types and describes the research design.

I then present the results of the validity and generality tests and follow

that with a discussion of the results of tests on the causal mechanisms

and a conclusion.

THE CONCEPT OF THE RENTIER STATE

Area specialists often describe most of the governments of the Mideast

and North Africa as rentier states, since they derive a large fraction of

their revenues from external rents.5 More than half of the governments

revenues in Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the United Arab Emirates, Oman,

Kuwait, Qatar, and Libya have, at times, come from the sale of oil. The

governments of Jordan, Syria, and Egypt variously earn large locational

rents from payments for pipeline crossings, transit fees, and passage

through the Suez Canal. Workers remittances have been an important

source of foreign exchange in Egypt, Yemen, Syria, Lebanon, Tunisia,

Algeria, and Morocco, although these rents go (at least initially) to private actors, not the state. The foreign aid that flows to Israel, Egypt, and

Jordan may also be considered a type of economic rent.

Economists in the early twentieth century used the term rentier

state to refer to the European states that extended loans to nonEuropean governments.6 Mahdavy is widely credited with giving the

term its current meaning: a state that receives substantial rents from

foreign individuals, concerns or governments.7 Beblawi later refined

this definition, suggesting that a rentier state is one where the rents are

paid by foreign actors, where they accrue directly to the state, and where

only a few are engaged in the generation of this rent (wealth), the majority being only involved in the distribution or utilization of it.8

5

Throughout this article I use the term Middle East to include North Africa. I adopt the World

Banks definition of this region: Algeria, Bahrain, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon,

Libya, Malta, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, and Yemen.

6

According to Lenin, The rentier state is a state of parasitic, decaying capitalism, and this circumstance cannot fail to influence all the socio-political conditions of the countries concerned. V. I.

Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism, in Robert C. Tucker, ed., The Lenin Anthology

(New York: W. W. Norton, 1975).

7

Hussein Mahdavy, The Patterns and Problems of Economic Development in Rentier States: The

Case of Iran, in M. A. Cook, ed., Studies in Economic History of the Middle East (London: Oxford University Press, 1970), 428.

8

Hazem Beblawi, The Rentier State in the Arab World, in Hazem Beblawi and Giacomo Luciani, eds., The Rentier State (New York: Croom Helm, 1987), 51. Note that this definition excludes

330

WORLD POLITICS

Claims about the rentier state can be sorted into two categories:

those that suggest oil wealth makes states less democratic and those

that suggest oil wealth causes governments to do a poorer job of promoting economic development. Often the two are conflated. This article focuses on the first claim.

According to Anderson, The notion of the rentier state is one of the

major contributions of Middle East regional studies to political science.9 Indeed, some scholars of democracy now use a version of this

argument to account for the otherwise puzzling states of the Middle

East. Huntington, for example, suggests that the democratic trend may

bypass the Middle East since many of these states depend heavily on

oil exports, which enhances the control of the state bureaucracy.10

Others have adapted the rentier state idea to oil-rich countries outside the Middle East.11

The claim that oil wealth per se inhibits democratization has not

been subjected to careful statistical tests, however, as most quantitative

studies of democracy simply overlook it as an explanatory variable. And

the handful that even acknowledge that oil-rich states have odd properties do little to explain why. Przeworski and his collaborators, for example, drop countries from their database if their ratio of fuel exports

to total exports in 19841986 exceeded fifty percentan eccentric criterion that excludes six oil-rich states, all of which are located on the

Arabian Peninsula.12 Barros study of democracy includes a dummy

variable for states whose net oil exports represent a minimum of twothirds of total exports and are at least equivalent to approximately one

percent of world exports of oil.13 The Barro oil dummy is statistically

significant and negatively correlated with democracy. But as in the

analyses of Przeworski et al., the dummy variable uses an arbitrary cutworkers remittances. As Chaudhry notes, large flows of remittances have different political implications than do large oil rents. See Kiren Aziz Chaudhry, The Price of Wealth: Economies and Institutions

in the Middle East (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1997).

9

Lisa Anderson, The State in the Middle East and North Africa, Comparative Politics 20 (October 1987), 9.

10

Samuel P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman:

University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 3132.

11

See, for example, Olle Trnquist, Rent Capitalism, State, and Democracy: A Theoretical Proposition, in Arief Budiman, ed., State and Civil Society in Indonesia, Monash Papers on Southeast Asia,

no. 22 (1990); Douglas A. Yates, The Rentier State in Africa: Oil Rent Dependency and Neocolonialism in

the Republic of Gabon (Trenton, N.J.: Africa World Press, 1996); Terry Lynn Karl, The Paradox of

Plenty: Oil Booms and Petro-States (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997); John Clark, PetroPolitics in Congo, Journal of Democracy 8 ( July 1997); idem, The Nature and Evolution of the State

in Zaire, Studies in Comparative International Development 32 (Winter 1998).

12

See Przeworski et al. (fn. 2, 2000), 77.

13

Robert J. Barro, Determinants of Democracy, Journal of Political Economy 107 (December 1999).

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

331

point to distinguish between oil states and nonoil states and implies that oil has little or no influence on regime type until some threshold is reached.

Qualitative studies of the oil-impedes-democracy hypothesis also

have important limitations. The vast majority have been country-level

case studies of oil-rich states in the Mideast. Although many have been

empirically rich and analytically nuanced, the Mideast is nevertheless a

difficult place to test this claim, since virtually all oil-rich Mideast governments have been highly authoritarian since gaining independence.

The absence of variation on the dependent variableas well as on

Islam, an important control variablehas made testing difficult. It has

also allowed Mideast specialists to neglect tasks that would help

sharpen and refine the oil-impedes-democracy claimdefining the key

variables better, specifying the causal arguments in falsifiable terms, and

outlining the domain of relevant cases to which their arguments apply.

As a result, the notion of the rentier state has suffered from a bad case

of conceptual overstretch: assertions about the influence of oil on Middle East politics have become so general that their validity has been diluted. As Okruhlik observes, The idea of the rentier state has come to

imply so much that it has lost its content.14

One way to restore the usefulness of an overstretched concept is by

testing it statistically. I thus evaluate one core facet of the rentier state

conceptthe oil-impedes-democracy claimwith three questions.

First, is there a statistically valid correlation between oil and authoritarianism once other germane variables are accounted for? Second, can the

claim be generalized both beyond the Middle East and beyond the case

of oil? Finally, if oil thwarts democracy, what is the causal mechanism?

Proponents of the oil-impedes-democracy hypothesis naturally suggest both that it is valid and that it can be generalized to oil exporters

outside the Middle East. Some also imply that other types of commodities have similar effects. Nothing in Beblawis definition, which is

widely accepted among Mideast specialists, restricts the set of rentier

states to oil exporters. In fact, the definition appears to cover many

mineral exporters on the grounds that (1) minerals tend to generate

rents, (2) the rents are largely captured by states via export taxes, corporate taxes, and state-owned enterprises, and (3) mineral extraction

employs relatively little labor. The same definition, however, implies

that exporters of agricultural commodities will not be rentier states.

14

Gwenn Okruhlik, Rentier Wealth, Unruly Law, and the Rise of Opposition, Comparative Politics 31 (April 1999), 308.

332

WORLD POLITICS

This is because (1) agricultural commodities generally do not produce

rents, (2) export revenues in most cases go directly to private actors, not

the state, and (3) agricultural production is more labor intensive and

hence employs a larger fraction of the population for a given value of

exports.15

CAUSAL MECHANISMS

At least three causal mechanisms might explain the alleged link between oil exports and authoritarian rule. The first comes largely from

Mideast specialists and might be called the rentier effect. A close

reading of case studies suggests a second mechanism: a repression effect. Modernization theory implies a third possible cause, which I call

the modernization effect.

THE RENTIER EFFECT

The first causal mechanism comes from the work of Middle East

scholars, who have pondered this issue for over two decades.16 In general they argue that governments use their oil revenues to relieve social

pressures that might otherwise lead to demands for greater accountability. Case studies describe three ways this may occur.17

The first is through what might be called a taxation effect. It suggests that when governments derive sufficient revenues from the sale of

oil, they are likely to tax their populations less heavily or not at all, and

the public in turn will be less likely to demand accountability from

and representation intheir government.18

The logic of the argument is grounded in studies of the evolution of

democratic institutions in early modern England and France. Historians and political scientists have argued that the demand for representation in government arose in response to the sovereigns attempts to raise

15

Note that, by contrast, dependency theory suggests that developing states are politically constrained by their reliance on the export of all types of primary commodities to advanced industrialized

states. See, for example, Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Enzo Faletto, Dependency and Development

in Latin America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979); Peter Evans, Dependent Development:

The Alliance of Multinational, State, and Local Capital in Brazil (Princeton: Princeton University Press,

1979); Kenneth A. Bollen, World System Position, Dependency, and Democracy: The Cross-National Evidence, American Sociological Review 48 (August 1983).

16

Perhaps they have thought about it too carefully. Chaudhry (fn. 8), notes that theories of the rentier state far outstrip detailed empirical analysis of actual cases (p. 187).

17

Case studies often conflate these three effects. I treat them here as separate mechanisms to clarify their logic.

18

Giacomo Luciani, Allocation vs. Production States: A Theoretical Framework, in Beblawi and

Luciani (fn. 8).

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

333

taxes.19 Some Mideast scholars have looked for similar correlations between variations in tax levels and variations in the demand for political

accountability. Crystal found that the discovery of oil made the governments of Kuwait and Qatar less accountable to the traditional merchant

class.20 Brands study of Jordan argued that a drop in foreign aid and remittances in the 1980s led to greater pressures for political representation.21 Yet not all Middle East specialists have been persuaded:

Waterbury argues that neither historically nor in the twentieth century is

there much evidence [in the Middle East] that taxation has evoked demands that governments account for their use of tax monies. Predatory

taxation has produced revolts, especially in the countryside, but there has

been no translation of tax burden into pressures for democratization.22

A second component of the rentier effect might be called the

spending effect: oil wealth may lead to greater spending on patronage, which in turn dampens latent pressures for democratization.23

Entelis, for example, argues that the Saudi Arabian government used

its oil wealth for spending programs that helped reduce pressures for

democracy.24 Vandewalle makes a similar argument about the Libyan

government.25 And Kessler and Bazdresch and Levy find that the

Mexican oil boom of the 1970s helped prop upand perhaps prolongone-party rule.26 While all authoritarian governments may use

19

Charles Tilly, ed., The Formation of National States in Western Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975); Robert Bates and Da-Hsiang Donald Lien, A Note on Taxation, Development,

and Representative Government, Politics and Society 14 ( January 1985); Philip T. Hoffman and

Kathryn Norberg, eds., Fiscal Crises, Liberty, and Representative Government, 14501789 (Stanford,

Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1994).

20

Jill Crystal, Oil and Politics in the Gulf: Rulers and Merchants in Kuwait and Qatar (New York:

Cambridge University Press, 1990).

21

Laurie A. Brand, Economic and Political Liberalization in a Rentier Economy: The Case of the

Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, in Iliya Harik and Denis J. Sullivan, eds., Privatization and Liberalization in the Middle East (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992).

22

John Waterbury, Democracy without Democrats? The Potential for Political Liberalization in

the Middle East, in Ghassan Salam, ed., Democracy without Democrats? The Renewal of Politics in the

Muslim World (New York: I. B. Tauris, 1994), 29.

23

Lam and Wantchekon develop a formal model that makes a similar point, that resource wealth

can impede democracy by enhancing the distributive influence of an elite. Ricky Lam and Leonard

Wantchekon, Dictatorships as a Political Dutch Disease (Manuscript, Department of Political Science, Yale University, January 1999).

24

John P. Entelis, Oil Wealth and the Prospects for Democratization in the Arabian Peninsula:

The Case of Saudi Arabia, in Naiem A. Sherbiny and Mark A. Tessler, eds., Arab Oil: Impact on the

Arab Countries and Global Implications (New York: Praeger, 1976).

25

Dirk Vandewalle, Libya since Independence: Oil and State-Building (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1998).

26

Carlos Bazresch and Santiago Levy, Populism and Economic Policy in Mexico, 197082, in

Rudiger Dornbusch and Sebastian Edwards, eds., The Macroeconomics of Populism in Latin America

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991); Timothy P. Kessler, Global Capital and National Politics:

Reforming Mexicos Financial System (Westport, Conn.: Praeger, 1999).

334

WORLD POLITICS

their fiscal powers to reduce dissent, these scholars imply that oil wealth

provides Middle East governments with budgets that are exceptionally

large and unconstrained.27 Rulers in the Middle East may follow the

same tactics as their authoritarian counterparts elsewhere, but oil revenues could make their efforts at fiscal pacification more effective.

The third component might be called a group formation effect. It

implies that when oil revenues provide a government with enough

money, the government will use its largesse to prevent the formation of

social groups that are independent from the state and hence that may

be inclined to demand political rights. One version of this argument is

rooted in Moores claim that the formation of an independent bourgeoisie helped bring about democracy in England and France.28 Scholars examining the cases of Algeria, Libya, Tunisia, and Iran have all

observed oil-rich states blocking the formation of independent social

groups; all argue that the state is thereby blocking a necessary precondition of democracy.29

A second version of the group-formation effect draws on Putnams

argument that the formation of social capitalcivic institutions that lie

above the family and below the statetends to promote more democratic governance.30 Scholars studying the cases of Algeria, Iran, Iraq,

and the Arab Gulf states have all suggested that the governments oil

wealth has impeded the formation of social capital and hence blocked a

transition to democracy.31

Whether Mideast states use their oil revenues to deliberately inhibit

group formation is a matter of some disagreement. In the case of Libya,

First suggests there is not a consistent policy against the development of

27

Lisa Anderson, Peace and Democracy in the Middle East: The Constraints of Soft Budgets,

Journal of International Affairs 49 (Summer 1995).

28

Barrington Moore, Social Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy (Boston: Beacon Press, 1966).

29

On Algeria, see Clement Henry Moore, Petroleum and Political Development in the Maghreb,

in Sherbiny and Tessler (fn. 24); on Libya, see Ruth First, Libya: Class and State in an Oil Economy,

in Petter Nore and Terisa Turner, eds., Oil and Class Struggle (London: Zed Press, 1980); also on Libya,

see Vandewalle (fn. 25); on Tunisia, see Eva Bellin The Politics of Profit in Tunisia: Utility of the Rentier Paradigm? World Development 22 (March 1994); and on Iran, see Hootan Shambayati, The Rentier State, Interest Groups, and the Paradox of Autonomy: State and Business in Turkey and Iran,

Comparative Politics 26 (April 1994).

30

Robert Putnam, Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 1993).

31

On Algeria, see John P. Entelis, Civil Society and the Authoritarian Temptation in Algerian

Politics, in Augustus Richard Norton, ed., Civil Society in the Middle East, vol. 2 (Leiden: E. J. Brill,

1995); on Iran, see Farhad Kazemi, Civil Society and Iranian Politics, in Norton; on the Gulf states,

see Jill Crystal, Civil Society in the Arab Gulf States, in Norton; on Iraq, see Zuhair Humadi, Civil

Society under the Bath in Iraq, in Jillian Schwedler, ed., Toward Civil Society in the Middle East?

(Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 1995). Other scholars have argued that the weakness of civil society

in the Middle East has hampered a transition to democracy, without suggesting that oil wealth is the

source of this weakness.

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

335

an indigenous bourgeoisie, but the growth of this class is in practice constrained by the states own economic ventures and its links with international capital.32 Chaudhry, by contrast, argues that in the 1970s the

Mideast governments used their oil revenues to develop programs that

were explicitly designed to depoliticize the population. . . . In all cases,

governments deliberately destroyed independent civil institutions while

generating others designed to facilitate the political aims of the state.33

Collectively, the taxation, spending, and group-formation effects

constitute the rentier effect. Together they imply that a states fiscal

policies influence its regime type: governments that fund themselves

through oil revenues and have larger budgets are more likely to be authoritarian; governments that fund themselves through taxes and are

relatively small are more likely to become democratic.

THE REPRESSION EFFECT

A close reading of case studies from the Mideast, Africa, and Southeast

Asia suggests that oil wealth and authoritarianism may also be linked

by repression. Citizens in resource-rich states may want democracy as

much as citizens elsewhere, but resource wealth may allow their governments to spend more on internal security and so block the populations democratic aspirations. Skocpol notes that much of Irans

pre-1979 oil wealth was spent on the military, producing what she calls

a rentier absolutist state.34 Clark, in his study of the 1990s oil boom in

the Republic of Congo, finds that the surge in revenues allowed the

government to build up the armed forces and train a special presidential

guard to help maintain order.35 And Gause argues that Middle East democratization has been inhibited in part by the prevalence of the

mukhabarat (national security) state.36

There are at least two reasons why resource wealth might lead to

larger military forces. One may be pure self-interest: given the opportunity to better arm itself against popular pressures, an authoritarian

government will readily do so. A second reason may be that resource

wealth causes ethnic or regional conflict; a larger military might reflect

the governments response. Mineral wealth is often geographically con32

First (fn. 29), 137.

Kiren Aziz Chaudhry, Economic Liberalization and the Lineages of the Rentier State, Comparative Politics 27 (October 1994), 9.

34

Theda Skocpol, Rentier State and Shia Islam in the Iranian Revolution, Theory and Society 11

(April 1982).

35

Clark (fn. 11, 1997).

36

F. Gregory Gause II, Regional Influences on Experiments in Political Liberalization in the Arab

World, in Rex Brynen, Bahgat Korany, and Paul Noble, eds., Political Liberalization and Democratization in the Arab World, vol. 1, Theoretical Perspectives (Boulder, Colo.: Lynne Rienner, 1995).

33

336

WORLD POLITICS

centrated. If it happens to be concentrated in a region populated by an

ethnic or religious minority, resource extraction may promote or exacerbate ethnic tensions, as federal, regional, and local actors compete for

mineral rights. These disputes may lead to larger military forces and

less democracy in resource-rich, ethnically fractured states such as Angola, Burma, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Indonesia, Nigeria,

Papua New Guinea, Sierra Leone, and South Africa. This mechanism

would be consistent with the research of Collier and Hoeffler and de

Soysa, who find that natural resource wealth tends to make civil war

more likely.37

THE MODERNIZATION EFFECT

Finally, a third explanation can be derived from modernization theory,

which holds that democracy is caused by a collection of social and cultural changesincluding occupational specialization, urbanization, and

higher levels of educationthat in turn are caused by economic development.38 Different scholars emphasize different clusters of social and

cultural changes. Perhaps the most carefully shaped position comes

from Inglehart, who argues that two types of social change have a direct

impact on the likelihood that a state will become democratic:

1. Rising education levels, which produce a more articulate public that is better equipped to organize and communicate, and

2. Rising occupational specialization, which first shifts the workforce into the

secondary sector and then into the tertiary sector. These changes produce a more

autonomous workforce, accustomed to thinking for themselves on the job and

having specialized skills that enhance their bargaining power against elites.39

Although modernization theory does not address the question of resource wealth per se, an implicit corollary is that if economic development does not produce these cultural and social changes, it will not

result in democratization. As Inglehart notes: Is the linkage between

development and democracy due to wealth per se? Apparently not: if

democracy automatically resulted from simply becoming wealthy, then

Kuwait and Libya would be model democracies.40 In other words, if

resource-led growth does not lead to higher education levels and

37

See Collier and Hoeffler (fn. 4); de Soysa (fn. 4).

Seymour Martin Lipset, Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and

Political Legitimacy, American Political Science Review 53 (March 1959); Karl W. Deutsch, Social

Mobilization and Political Development, American Political Science Review 55 (September 1961); Inglehart (fn. 1).

39

Inglehart (fn. 1), 163.

40

Ibid., 161.

38

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

337

greater occupational specialization, it should also fail to bring about democracy. Unlike the rentier and repression effects, the modernization

effect does not work through the state: it is a social mechanism, not a

political one.

The rentier, repression, and modernization effects are largely complementary. The rentier effect focuses on the governments use of fiscal

measures to keep the public politically demobilized; the repression effect stresses the governments use of force to keep the public demobilized; and the modernization effect looks at social forces that may keep

the public demobilized. All three explanations, or any combination of

them, may be simultaneously valid.41

MODEL SPECIFICATION AND RESEARCH DESIGN

To test the oil-impedes-democracy claim, I present a model to predict

regime types and test it using a feasible generalized least-squares

method with a pooled time-series cross-national data set, which includes data on all sovereign states with populations over one hundred

thousand between 1971 and 1997. The model includes five causal variables that according to previous studies are the most robust determinants of democracy. It also includes variables that measure a states oil

and mineral wealth to see if they add explanatory power.

The basic regression model is:

Regimei,t = a1 + b1(Oili,t-5 ) + b2(Mineralsi,t-5 ) + b3(Log Incomei,t-5 )

+ b4 (Islami ) + b5(OECDi ) + b6(Regimei,t-5 ) + b7(Year1 ) . . . + b33(Year26 )

where i is the country and t is the year.

The dependent variable, Regime, is derived from the Polity98 data

set constructed by Gurr and Jaggers.42 Gurr and Jaggers compile two

010 interval scale variables, DEMOC and AUTOC; the former differentiates between states that are relatively democratic, while the latter

variable differentiates between authoritarian states. Since the two indicators contain separate, nonoverlapping types of information about

each country year, I combine them into a single measure by subtracting

41

A fourth explanation has been offered by U.S. vice president Richard Cheney, a political scientist

by training: The problem is that the good Lord didnt see fit to put oil and gas reserves where there are

democratic governments. Cited in David Ignatius, Oil and Politics Mix Suspiciously Well in

America, Washington Post, July 30, 2000, A31.

42

Each of the variables is defined more precisely in Appendix 1. Ted R. Gurr and Keith Jaggers,

Polity 98: Regime Characteristics, 18001998, http://www.bsos.umd.edu/cidcm/polity/, 1999 (consulted March 1, 2000).

338

WORLD POLITICS

the autocracy measure from the democracy measure.43 I then rescale it

as a 010 variable, with 10 representing most democratic.

Oil and Minerals are the independent variables; they measure the export value of mineral-based fuels (petroleum, natural gas, and coal) and

the export value of nonfuel ores and metals exports, as fractions of GDP.

These variables capture both the importance of fuels and minerals as

sources of export revenue and their relative importance in the domestic

economy.44

The right-hand side of the equation also includes five control variables designed to capture the factors most robustly associated with

regime type, for which indicators are available for most of the countries

and years. The first is Income, measured as the natural log of per capita

GDP corrected for purchasing power parity (PPP), in current international dollars. Per capita income has been widely accepted as a correlate

of democracy since Lipset; its validity has been confirmed in more recent tests by Burkhart and Lewis-Beck, Londregan and Poole, Przeworski and Limongi, and Barro.45

The second control variable is Islam, which denotes the Muslim percentage of the states population in 1970.46 Previous studies have suggested that states with large Muslim populations tend to be less

democratic than non-Muslim states.47 Of all the religious categories

tested by Barro, Islam (measured the same way with the same data set)

had by far the largest and most statistically significant influence on a

states regime type.48 Placing Islam in this model has special importance

43

Here I am following the practice of John B. Londregan and Keith T. Poole, Does High Income

Promote Democracy? World Politics 49 (October 1996).

44

Oil and Minerals are similar to the indicators used by Sachs and Warner (fn. 3, 1995) and by Leite

and Weidmann (fn. 3) in their studies of the influence of resource wealth on economic performance.

While Sachs and Warner combine fuels, nonfuel minerals, and agricultural goods into a single variable, I consider them as separate variables to see if their regression coefficients (and hence their influence on regime types) differ.

45

Lipset (fn. 38); Ross E. Burkhart and Michael S. Lewis-Beck Comparative Democracy: The

Economic Development Thesis, American Political Science Review 88 (December 1994); Londregan

and Poole (fn. 43); Przeworski and Limongi (fn. 2); Barro (fn. 13).

46

In virtually all cases, the figure for 1980 (the only other year for which data were available) was

identical to the 1970 figure.

47

Salam (fn. 22); Seymour Martin Lipset,The Social Requisites of Democracy Revisited, American Sociological Review 59 (February1994); Manus Midlarsky, Democracy and Islam: Implications for

Civilizational Conflict and the Democratic Peace, International Studies Quarterly 42 (December 1998).

48

Barro (fn. 13). Observers offer different arguments to explain the negative correlation between

democracy and Islamic populations (.38). See, for example, Hisham Sharabi, Neopatriarchy: A Theory

of Distorted Change in Arab Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988); Bernard Lewis, Islam

and Liberal Democracy, Atlantic Monthly 271 (February 1993); and Michael Hudson, The Political

Culture Approach to Arab Democratization: The Case for Bringing It Back In, Carefully, in Brynen,

Korany, and Noble (fn. 36). Although they are negatively correlated for the period covered by this data

set (197197), it is not obvious that they will continue to be negatively correlated in the future. Two

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

339

because many states with great mineral wealth also have large Muslim

populations, not only in the Middle East but also in parts of Asia (Indonesia, Malaysia, Brunei) and Africa (Nigeria). The simple correlation

between Oil and Islam is 0.44.

The third control variable is OECD, a dummy that is coded 1 for

states that are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (excluding newer members Mexico and South

Korea) and 0 for all others. Previous researchers have found that the advanced industrialized states of the OECD are significantly more likely to

be democratic in the postWorld War II era than the states of the developing world, even after the influence of income and other factors are

accounted for.49 There is no consensus on why this is so. It has variously

been attributed to the Wests unique historical trajectory;50 the cultural

influence of Protestantism;51 the residual effects of Western colonialism

on non-Western states;52 and a world system that constrains the

prospects of states in the non-Western periphery.53 Conceivably any

antidemocratic effects from Oil and Minerals might be spurious and

merely reflect the location of most fuel- and mineral-exporting states

in the non-Western world. The OECD dummy helps account for any of

these Western-specific effects, without taking a position on the mechanisms behind it.

The fourth control variable is Regimet-5, which is the dependent variable lagged by five years. Placing it on the right-hand side of the model

has three purposes. First, the most important influence on a states

regime type may often be its own peculiar history; Regimet-5 helps capture any country-specific historical or cultural features that may be

missed by the other right-hand-side variables. Second, including

Regimet-5 helps turn the equation into a change model, transforming

the dependent variable from regime type to the change in a countrys

regime type over a given five-year period. This helps ensure that the restates with large Islamic populations, Nigeria and Indonesia, have recently moved toward democracy,

and some of the most important prodemocracy forces in other Islamic states (including Algeria, Egypt,

Jordan, and Malaysia) are often classified as Islamic traditionalists or fundamentalists. It is instructive to recall that until the third wave of democratization began in the mid-1970s, democracy and

Catholicism were negatively correlated.

49

See Burkhart and Lewis-Beck (fn. 45); Londregan and Poole (fn. 43); Przeworski and Limongi

(fn. 2).

50

See Moore (fn. 28).

51

See Lipset (fn. 38); Huntington (fn. 10).

52

See Robert A. Dahl, Polyarchy: Participation and Opposition (New Haven: Yale University Press,

1971).

53

See Immanuel Wallerstein, The Modern World-System (New York: Academic Press, 1974); Bollen

(fn. 15); Burkhart and Lewis-Beck (fn. 45).

340

WORLD POLITICS

gression will indeed measure both time-series and cross-sectional

changes in regime types. Third, Regimet-5 helps address the problem of

serial correlation that tends to bedevil pooled time-series cross-sectional data sets.54

Finally, the model includes a set of twenty-six dummy variables, one

for each year covered by the data (197197), less one to mitigate autocorrelation. These are designed to capture two types of time-specific effects. The first is the cold war, which may have blocked many transitions

to democracy. The second are contagion effects that influenced states at

different times in Southern and Eastern Europe, Latin America, and

sub-Saharan Africa, where early transitions to democracy appeared to

boost the likelihood of subsequent transitions in proximate states.

The tests were run with a feasible generalized least-squares process

using Stata 6.0.55 Since I include a lagged dependent variable on the

right-hand side of the equation, I correct for first-order autocorrelation

using a panel-specific process, which allows the degree of autocorrelation to vary from country to country.

I use a five-year lag for all independent and control variables. The lag

gives more confidence that the causal arrow is pointing in the right direction; it also enables me to look for factors that have an enduring impact on regime types. As I illustrate below, using shorter lags does not

change the results of the basic model, but it does increase the absolute

value of the coefficient of the lagged dependent variable relative to the

other explanatory variables. Hence with a one-year lag, a countrys current regime type becomes overwhelmingly a function of its regime type

in the previous year, while the influence of other variables is artificially

suppressed.56

RESULTS

For the basic model described below, Stata is able to utilize 2,183

country-year observations from 113 states, out of a possible 3,752

observations from 158 states. The data for each of the variables are summarized in Appendix 2.

54

James A. Stimson, Regression in Space and Time: A Statistical Essay, American Journal of Political Science 29 (November 1985); Nathaniel Beck and Jonathan N. Katz, What to Do (and Not to Do)

with Time-Series Cross-Section Data, American Political Science Review 89 (September 1995).

55

Beck and Katz (fn. 54) recommend using ordinary least squares with panel-corrected standard

errors when working with panel data if the number of units is less than the number of time points. In

this data set the number of units (113) exceeds the number of time points (27).

56

Christopher H. Achen, Why Lagged Dependent Variables Can Suppress the Explanatory Power

of Other Independent Variables (Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Political Methodology

Section of the American Political Science Association, Los Angeles, July 2022, 2000).

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

341

TABLE 3

RESOURCE WEALTH AND DEMOCRACYa

(DEPENDENT VARIABLE IS REGIME)

Regime

Oil

Minerals

Income (log)

Islam

OECD

Food

Agriculture

Observations

States

Log likelihood

.253***

(.0203)

.0346***

(.0051)

.0459***

(.00778)

.922***

(.105)

.018***

(.00208)

1.47***

(.308)

.894***

(.00846)

.0078***

(.0024)

.00718*

(.00317)

.119***

(.0342)

.0031***

(.000665)

.176*

(.0781)

.25***

(.0203)

.0339***

(.00506)

.0438***

(.0081)

.935***

(.106)

.0178***

(.0021)

1.42***

(.305)

.0244*

(.0102)

.246***

(.0204)

.0393***

(.00543)

.0455***

(.00804)

.965***

(.107)

.0173***

(.00211)

1.44***

(.308)

2182

113

3129

2178

113

3123

2183

113

3133

2498

115

3283

.042

(.0239)

* significant at the 0.05 level; ** significant at the 0.01 level; *** significant at the 0.001 level

a

All independent and control variables are entered with five-year lags, except in column

2, where they are entered with a one-year lag. Standard errors are in parentheses below the

coefficients. Feasible Generalized Least Squares regressions run with Stata 6.0; corrected

for first-order autocorrelation using a panel-specific process. Each regression is run with

dummy variables for every year (but one) covered by the data.

The results of the basic model are reported in Table 3, column 1. All

of the variables are highly significant with the expected signs.57 Both

Oil and Minerals have strong antidemocratic effects; these effects are of

roughly the same magnitude, although the Minerals coefficient is somewhat larger.58

57

Most of the coefficients for the year dummies are also significant: for years 197189 the coefficients

are negative and range from marginally to highly significant; for 1990 the coefficient is negative but not significant; and for years 199196 the coefficients are positive, although all but one (1994) are not significant.

58

These results were unaffected by the inclusion of other variables that are sometimes significant in

democracy regressions, including educational attainment, status as a former British colony, Catholic

population, and trade openness. Only the last variable was significant. When run with a randomeffects process, a Hausman test produces a chi2 of 466 and a P value of 0.000. When run with a fixedeffects process, however, none of the right-hand-side variablesexcept for the lagged dependent

variable and Log Incomeare significant.

342

WORLD POLITICS

Regime

0

0

10

20

30

40

50

Value of Oil Exports (U.S. Dollars, Billion per Year)

FIGURE 1

IMPACT OF OIL EXPORTS ON REGIME

a

This figure shows the net predicted impact of oil exports on the 010 variable Regime, for a

hypothetical country of twenty million people with a per capita income of $1,720 dollars a year, which

is the sample mean. Note the scale on the Y-axis is negative.

The results suggest that the antidemocratic properties of oil and

mineral wealth are substantial: a single standard deviation rise in the

Oil variable produces a .49 drop in the 010 democracy index over the

five-year period, while a standard deviation rise in the Minerals variable

leads to a .27 drop. A state that is highly reliant on oil exportsat the

1995 level of Angola, Nigeria, or Kuwaitwould lose 1.5 points on the

democracy scale due to its oil wealth alone. A state that was equally dependent on mineral exports would lose 2.1 points.

The model also implies, however, that the impact of any new oil or

mineral wealth may be partly offset by a rise in income. To complicate

matters, the influence of Oil and Minerals on Regime is nonlinear, and the

magnitude of their impact depends on the states prior level of income.59

As Figure 1 shows, the marginal influence of Oil on Regime is larger

when oil exports are a small fraction of the economy, and it drops as the

country grows more reliant on oil. While Barro and Przeworski et al.

imply that oil wealth matters only when exports reach extraordinarily

59

These effects occur because Income is entered in the model as a logarithmic function and because

an oil discovery will influence both the numerator and the denominator in the Oil variable.

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

343

Regime

0

0

5000

10000

15000

20000

25000

30000

Initial per Capita Income (U.S. Dollars)

FIGURE 2

IMPACT OF $10 BILLION ANNUAL RISE IN OIL EXPORTS ON REGIME, BY INITIAL

PER CAPITA INCOME

a

This figure shows the net predicted impact of a $10 billion rise in oil exports on the 010 variable

Regime, by initial per capita income, for a hypothetical country with a population of twenty million,

with no prior oil exports. Note the scale on the Y-axis is negative.

high levels, this test suggests the opposite: barrel for barrel, oil harms

democracy more in oil-poor countries than in oil-rich ones.

The test also implies that oil and mineral wealth cause greater damage to democracy in poor countries than in rich ones (see Figure 2).

Imagine a country whose per capita income is $800 a yearabout the

level of Chad, Mozambique, and Yemenwith a population of twenty

million and no oil exports. Suppose prospectors find an oil field that

produces $10 billion of petroleum each year, all of which is exported.

The new oil would simultaneously boost per capita income (a prodemocratic effect) and raise the Oil variable (an antidemocratic effect).

The model predicts that after five years the government would become

less democratic, losing about .93 on the 010 democracy scale. A comparable discovery in a state whose initial per capita income was

$1,720the sample meanwould lose .54 points; if the per capita income were $8,000about the level of Mexico and Malaysiathe same

oil field would be associated with a drop of just .16 in Regime. This pattern is consistent with the observation that large oil discoveries appear

344

WORLD POLITICS

to have no discernible antidemocratic effects in advanced industrialized

states, such as Norway, Britain, and the U.S., but may harm or destabilize democracy in poorer countries.

To determine how general and robust these effects are, I carry out

five additional tests. First, to see whether the results are sensitive to the

duration of the lag on the right-hand-side variables, I run the same

model using one-year lags on all the explanatory variables (Table 3, column 2). All of the variables remain significant, although the absolute

value of the coefficient on the lagged regime type variable grows, and

the absolute values and significance of the coefficients on the other

variables are reduced, perhaps artificially.60

Next, to see whether other types of commodity exports also inhibit

democratization, I add two variables to the model: Food, which measures the value of all food exports as a fraction of GDP, and Agriculture,

which measures the value of all nonfood agricultural exports as a fraction of GDP. As columns 3 and 4 of Table 3 show, the coefficients on

Food and Agriculture are both positiveunlike Oil and Minerals, which

are negative. These findings are consistent with the rentier state thesis:

oil and other minerals impede democracy, but other primary commoditieswhich generate few or no rents, produce less export income for

the state, and employ a larger fraction of the labor forcedo not.

The third test is designed to see whether the model is heavily influenced by the inclusion of small states in the sample. Some of the states

most dependent on oil have small populations, including Brunei and

the Persian Gulf states of Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, and the United Arab

Emirates; it would not be surprising if they had a large influence on the

magnitude and significance of the Oil variable. To determine this, I

placed a dummy variable, Large States, in the model; it was coded 0 if a

states population was below one million and 1 otherwise. The results

are displayed in Table 4, column 1. The coefficient on the population

dummy is positive and significant at the 0.05 level, indicating that

small states do tend to be less democratic than large ones; yet its inclusion has only a tiny influence on the Oil and Minerals coefficients and

leaves them highly significant.

The fourth test looks at whether the apparent effects of Oil and

Minerals are caused by cultural or historical impediments to democratization that are specific to the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa,

two regions where these states are most heavily concentrated. I add two

dummy variables to the regression, Mideast and SSAfrica, which were

60

See Achen (fn. 56).

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

345

TABLE 4

RESOURCE WEALTH AND DEMOCRACYa

(DEPENDENT VARIABLE IS REGIME)

1

.209***

(.0205)

.0209***

(.00512)

.0265***

(.00718)

.789***

(.117)

.00538

(.0033)

1.6***

(.31)

.227***

(.0203)

.0138*

(.00557)

.0336***

(.00761)

.895***

(.112)

.013***

(.00238)

1.39***

(.286)

Mideast

.255***

(.0203)

.0333***

(.00511)

.0439**

(.00802)

.947***

(.105)

.0178***

(.00209)

1.41***

(.306)

.828*

(.406)

SSAfrica

Arabian Peninsula

3.65***

(.386)

1.62***

(.2)

2183

113

3133

2183

113

3086

Regime

Oil

Minerals

Income (log)

Islam

OECD

Large States

Observations

States

Log likelihood

.998***

(.194)

3.74***

(.49)

2183

113

3100

* significant at the 0.05 level; ** significant at the 0.01 level; *** significant at the 0.001 level

a

All independent and control variables are entered with five-year lags. Standard errors

are in parentheses below the coefficients. Feasible Generalized Least Squares regressions

run with Stata 6.0; corrected for first-order autocorrelation using panel-specific process.

Each regression is run with dummy variables for every year (but one) covered by the data.

coded 1 if the states were classified by the World Bank as residing in

these regions and 0 otherwise. While the lagged dependent variable

helps control for unspecified country-level effectswhich might

crudely be summarized as the countrys historyMideast and

SSAfrica test for additional region-level effects, or the regions history.

The results are listed in column 2 of Table 4. The coefficients for

both Mideast and SSAfrica are large, negative, and highly significant.

The coefficients on the Oil and Minerals variables are again reduced but

remain highly significant. The Islam variable loses significance, due to

its high correlation with the Mideast variable (=.65).

346

WORLD POLITICS

For the final test, I use a new dummy, Arabian Peninsula, in place of

the Mideast dummy; it was coded 1 for the seven states of the Arabian

Peninsula (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, the United

Arab Emirates, and Yemen) and 0 otherwise. Conceivably the Mideast

dummy is too broad, since it attempts to capture the effects of residing

in a region that is socially and geologically diverse. The antidemocratic

effects of oil might be somewhat more restricted to the Arabian Peninsula, which is dominated by monarchies, sparsely populated, and endowed with spectacular oil wealth. Using Arabian Peninsula instead of

Mideast reduces the problem of collinearity with Islam, although Arabian Peninsula and Oil remain highly collinear (simple correlation

=.74). Still, while including the Arabian Peninsula dummy reduces the

magnitude of the Oil coefficient by about 60 percent, Oil remains significant at the 0.05 level.

These tests support both the validity and the generality of the oilimpedes-democracy claim. They suggest the following: that a states reliance on either oil or mineral exports tends to make it less democratic;

that this effect is not caused by other types of primary exports; that it is

not limited to the Arabian Peninsula, to the Middle East, or to sub-Saharan Africa; and that it is not limited to small states. These findings

are generally consistent with the theory of the rentier state.

Area specialists might also feel vindicated in noting that in these

tests the most powerful impediments to democracy include the variables Regimet-5, Mideast, and Arabian Peninsula, which represent the accumulation of historical and cultural factors in each country, and in the

Arabian Peninsula and Mideast regions, that are not captured by income, resource wealth, Islam, or non-Western status. This underscores

the critical importance of case studies in explaining regime types.

CAUSAL MECHANISMS

To test the three causal mechanisms I add to the basic model a series of

intervening variables, lagged by one year. Adding new variables reduces

the sample size from 2,183 observations to between 2,183 and 426 observations. As the sample shrinks, it becomes increasingly skewed toward states that are relatively wealthy, democratic, and Western,

introducing a pronounced sample bias. To minimize this problem, after

running each of the following regressions, I run a second regression

using the same reduced sample, but without the intervening variable. I

then compare the two regressions. If the intervening variable is valid, it

should be statistically significant, andif the Oil and Minerals variables

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

347

are significant in the reduced sampleits inclusion should reduce the

absolute values of the Oil and Minerals coefficients. This provides at

least a crude test of some of the causal mechanisms.

RENTIER EFFECT

To test the rentier hypothesis, I use three indicators. For the taxation

effect I use the variable Taxes, which is the percentage of government

revenue collected through taxes on goods, services, income, profits, and

capital gains. The taxation effect implies that states that fund themselves through these assorted personal and corporate taxes (and hence

have higher values on the Taxes variable) should be more democratic;

conversely, states that fund themselves through other means (such as

trade taxes, parastatals, external grants, and right-of-way fees) should

be more authoritarian. The variable is constructed from data collected

by the International Monetary Fund and covers 104 of the 113 states

in the basic model.

To test the spending effect I use Government Consumption, which

measures government consumption as a percentage of GDP; this includes all current spending for purchases of goods and services (including wages and salaries) by all levels of government. If the spending effect

is valid, higher levels of government spending should result in less democracy. The data cover 104 states and are compiled by the World

Bank, which in turn collects information from the OECD, national statistical organizations, central banks, and World Bank missions.

The third variable is Government/GDP, which measures the share of

GDP accounted for by government activity, in 1985 international prices;

the data are from Summers and Heston.61 This final indicator is one

way to look for a group-formation effect. Proponents of this effect

imply that as governments increase in size (relative to the domestic

economy) they are more likely to prevent the formation of civic institutions and social groups that are independent from the government, and

that the absence of these groups will hinder a transition to democracy.62

Without good indicators for civic institutions or social groups, this hypothesis cannot be tested directly with regression analysis. Still, the

Government/GDP variable offers an indirect test: the greater the governments size (as a fraction of GDP), the less likely that independent social groups will form.

61

Robert Summers and Alan Heston, Penn World Tables, Version 5.6, http://cansim.epas.

utoronto.ca;5680/pwt/pwt.htm/, 1999 (consulted March 1, 2000).

62

Of course, a larger budget may not be the only cause of such government actions, but it is the only

cause that can be linked to resource wealth in an obvious way.

348

WORLD POLITICS

TABLE 5

THE RENTIER EFFECTa

(DEPENDENT VARIABLE

Regime

Oil

Mineral

Income (log)

Islam

OECD

Taxes

Government

Consumption

Government/GDP

Observations

States

Log likelihood

IS REGIME )

.259***

(.021)

.0223***

(.00647)

.0157

(.0113)

1.005***

(.104)

.0165***

(.00205)

1.19***

(.272)

.02***

(.00373)

.243***

(.0211)

.0323***

(.00544)

.0463***

(.00677)

.889***

(.112)

.0191***

(.00218)

1.57***

(.314)

.251***

(.0203)

.0351***

(.00511)

.0369***

(.00675)

.857***

(.106)

.0161***

(.00212)

1.53***

(.303)

.0305***

(.00866)

1698

104

2320

2121

110

3036

.0332***

(.00739)

2168

111

3107

* significant at the 0.05 level; ** significant at the 0.01 level; *** significant at the 0.001 level

a

Independent and control variables are entered with five-year lags; intervening variables

(Taxes, Government Consumption, Government/GDP) are entered with one-year lags. Standard errors are in parentheses below the coefficients. Feasible Generalized Least Squares

regressions run with Stata 6.0; corrected for first-order autocorrelation using panel-specific

process. Each regression is run with dummy variables for every year (but one) covered by

the data.

As Table 5 shows, the coefficient on Taxes is highly significant and

positive: as the rentier effect implies, higher personal and corporate

taxes are strongly associated with more democratic government. Moreover, the inclusion of Taxes produces a 17 percent drop in the Oil coefficient, which implies that the taxation effect may account for part of

the antidemocratic influence of Oil.63 While it is possible that causality

also runs the other waythat regime type influences taxationit

should be in the opposite direction: more democratic governments

63

The Minerals variable is not significant in this sample, making it difficult to draw inferences about

the mineral-exporting states.

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

349

should be less disposed to fund themselves through personal and corporate taxes, given their unpopularity.

The effect of taxes on regime types turns out to be strictly short

term: when Taxes is introduced into the model with a two- or threeyear lag, its coefficient quickly drops in size and loses significance. This

implies that tax increases have only short-term effects on democracy:

people tend to respond to tax hikes right away or not at all.64

The Government Consumption variable is also highly significant in

the hypothesized direction (Table 5, column 2). When Government

Consumption is included in the model, Oil and Minerals drop slightly,

by 7 and 6 percent, respectively. The spending effect appears to last

longer than the taxation effect: the Government Consumption variable

has much the same effect on regime type after three years as it does

after one.

These results are not likely caused by endogeneity. While there is evidence that regime type influences levels of government consumption,

it is in the opposite direction found here: democratic governments tend

to favor higher levels of social spending than their authoritarian counterparts.65

Finally, Government/GDP is also highly significant with the hypothesized sign: the larger the government, the less movement toward democracy over the following five years. Its inclusion has no effect on the

Oil variable but produces a 12 percent drop in the Minerals variable

(Table 5, column 3).

In short, the results are consistent with all three aspects of the rentier

effect.

REPRESSION EFFECT

I use two variables to test the hypothesis that resource wealth causes

governments to arm themselves more heavily against popular pressures.

The first is Military/GNP, which measures the size of the military budget as a fraction of GNP. The data were originally collected by the Arms

Control and Disarmament Agency (ACDA) of the U.S. government and

64

Note that other studies have found that a governments reliance on personal and corporate tax

revenues is strongly and negatively influenced by per capita income: poor states tend to rely on trade

taxes, rich ones on personal and corporate taxes. See William Easterly and Sergio Rebelo, Fiscal Policy and Economic Growth, Journal of Monetary Economics 32 (December 1993); Howell H. Zee, Empirics of Cross-Country Tax Revenue Comparisons, World Development 24 (October 1996). Since per

capita income is included in the model, the actual effect of Taxes on regime types is probably larger

than the coefficient in this regression suggests.

65

David S. Brown and Wendy Hunter, Democracy and Social Spending in Latin America,

198092, American Political Science Review 93 (December 1999).

350

WORLD POLITICS

cover 101 states between 1985 and 1995.66 Since resource-rich states

tend to have government budgets that are atypically large relative to the

size of their economies, this is a better indicator than military spending as a fraction of government spending.

The second variable is Military Personnel, which measures the size of

the military as a fraction of the labor force; it includes some paramilitary forces if those forces resemble regular units in their organization,

equipment, training, or mission. The data are also from ACDA and are

available from 1985 to 1995 for 105 of the states in the database. Unlike the Military/GNP measure, this indicator helps control for variations

in military wages and the presence of conscription across states.

When Oil, Minerals, and Income are regressed on Military/GNP directly (with a five-year lag), the behavior of oil exporters and mineral

exporters diverges. Oil exports are indeed positively and significantly

correlated with military spending, as the repression hypothesis suggests;

but mineral exports are negatively and significantly associated with

military spending. Neither variable is significantly linked with Military

Personnel.

When Military/GNP is placed in the basic model of regime types, its

coefficient is negative and marginally significant at the 0.10 level; its inclusion produces a 6 percent drop in the Oil coefficient (Table 6). The

Military Personnel coefficient is negative and highly significant, although it paradoxically induces a 7 percent rise in Oil. In both samples

the Minerals coefficient is not significant and cannot be interpreted.

Overall, it appears that oil wealth may be linked to higher levels of

military spending, which in turn tends to impede democracy, as the repression effect suggests. But there is no evidence of a similar pattern for

mineral wealth; nor is there evidence to support the claim that oil or

mineral wealth leads to higher levels of military personnel.

Why do oil-rich governments invest as much as they do on their

militaries? Is it to repress popular pressures, or is it a response to higher

levels of instability? To address this question I use data from the Political Risk Services Group, a private firm that uses subjective measures to

gauge investment risks for its clients. It produces a 06 measure of Ethnic Tensions, which measures the degree of tension within a country attributable to racial, nationality, or language divisions. Scores are

available for 102 states between 1982 and 1997. Higher values indicate

less ethnic tension. When added to the modelfirst separately, then

66

Since the data cover only eleven years, the maximum number of possible observations for these regressions drops from 3,752 to 1,642.

DOES OIL HINDER DEMOCRACY ?

351

TABLE 6

THE REPRESSION EFFECTa

(DEPENDENT VARIABLE

Regime

Oil

Minerals

Income (log)

Islam

OECD

Military/GNP

Military Personnel

Ethnic Tensions

Observations

States

Log likelihood

IS REGIME )

.414***

(.032)

.0591***

(.00566)

.0169

(.0272)

.848***

(.132)

.0173***

(.00266)

.071

(.332)

.0366

(.0197)

.334***

(.0314)

.0679***

(.00632)

.00344

(.0179)

.822***

(.145)

.0158***

(.00235)

.00168

(.355)

.34***

(.0262)

.0517***

(.00609)

.000964

(.0201)

.824***

(.117)

.0263***

(.00251)

.0957

(.3)

.09**

(.0304)

841

101

1228

874

105

1293

.0254

(.0485)

1167

102

1642

* significant at the 0.05 level; ** significant at the 0.01 level; *** significant at the 0.001 level

a

All independent and control variables are entered with five-year lags; intervening variables (Military/GNP, Military Personnel, Ethnic Tensions) are entered with one-year lags.

Standard errors are in parentheses below the coefficients. Feasible Generalized Least

Squares regressions run with Stata 6.0; corrected for first-order autocorrelation using panelspecific process. Each regression is run with dummy variables for every year (but one) covered by the data.

together with Military/GNP, and finally controlling for ethnolinguistic

fractionalizationthe Ethnic Tensions variable is not statistically significant (Table 6, column 3). In other words, tensions caused by racial, national, or language divisions do not explain why oil-rich states spend so

heavily on repression.

MODERNIZATION EFFECT

To test the modernization hypothesis I use eleven indicators to determine whether abnormally low levels of occupational specialization, education, health services, media participation, and urbanization can help

352

WORLD POLITICS

explain the dearth of democracy in the resource-rich states. The large

number of indicators allows me to test both Ingleharts version of modernization theory and earlier versions described by Lerner, Deutsch,

and Lipset.

According to Inglehart, occupational specialization and education

are the key links between economic growth and democracy. To measure

occupational specialization I look at the number of men and women in

the economys secondary (industrial) and tertiary (services) sectors as a

fraction of the men and women in the economically active population.

These data are drawn from the International Labor Organization and

cover 76 of the 113 states used in the basic model.