The Butcher's Trail

The Butcher's Trail

Uploaded by

wamu885Copyright:

Available Formats

The Butcher's Trail

The Butcher's Trail

Uploaded by

wamu885Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

The Butcher's Trail

The Butcher's Trail

Uploaded by

wamu885Copyright:

Available Formats

1.

O P E R AT I O N A M B E R S TA R

The unbearable timidity of the United States and its European

allies to rapidly strategize and then implement an effective means

of apprehending indicted fugitives from justice in the former

Yugoslavia constituted an abdication of responsibility that will haunt

the legacies of these governments and those who led them.

—David Scheffer, former US war crimes envoy 1

the leaders of the NATO alliance and Russia

O N M AY 2 7 , 1 9 9 7 ,

gathered at the Élysée Palace in Paris to bury the Cold War amid

the fin de siècle splendor of a hundred crystal chandeliers and a

thousand bottles of vintage champagne.

In retrospect, the signing ceremony for the Founding Act on

Mutual Relations, Cooperation and Security marked a brief flow-

ering of amity and goodwill before a return to the dangerous

mutual contempt of the Vladimir Putin era.

That Parisian spring, however, everything seemed possible.

Boris Yeltsin was still Russia’s president and at his gregarious

best. High on geopolitics and fine wine, he bestowed heartfelt

kisses on the cheeks of Western leaders.

“You have good eyes, a bright mind, the right age, good expe-

rience. So I believe Great Britain is in good hands,” Yeltsin told a

[1]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 1 11/19/15 12:20 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

blushing Tony Blair, the United Kingdom’s freshly elected forty-

four-year-old prime minister.2

Bill Clinton was hobbling around with a cane after a knee

operation and facing a sexual harassment suit back home,3 but

even he seemed revived and animated by the general spirit of

euphoria, saying that “the veil of hostility between East and West

has lifted.” 4

The French president Jacques Chirac, who was hosting the

event, aimed even higher. “The Paris accord does not shift the

divisions created in Yalta. It does away with them once and for

all,” he promised.5

As a prediction, it has not stood the test of time, but it was

not true even then. As Chirac spoke that evening in Paris, the

foundations of a new east-west divide were being dug. When the

leaders gathered for a banquet, Clinton, Blair, and Chirac formed

a brief huddle to discuss a pressing concern, imminent joint mil-

itary action to arrest war criminals in Bosnia and Herzegovina,

starting with Radovan Karadžić, the Bosnian Serbs’ wartime

leader, who had presided over the wholesale ethnic cleansing of

his territory.

This was something that could not be shared with Moscow,

the Serbs’ longstanding and most powerful ally. So when Yeltsin

found the group and asked his new friends what they were talk-

ing about, they swiftly dropped the subject.

“Nothing, Boris. Come and join us,” Clinton beckoned,

beaming.6

The secret the Western leaders were guarding was new and

fragile. They had only recently agreed to pursue war crimes sus-

pects, after furious debates within their governments which had

pitted civilians against soldiers. In the eyes of the generals, chas-

ing criminals was a job for the police.

[2]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 2 11/19/15 12:20 PM

O P E R AT I O N A M B E R S TA R

After all the blood spilled in Afghanistan and Iraq, it is strik-

ing to look back on the extreme caution of the US military and

its NATO allies about deployment to Bosnia in December 1995.

They had delayed intervening in the Balkan slaughter for years

but once a peace had been signed, the world’s most powerful alli-

ance arrived in force. More than sixty thousand soldiers were

garrisoned in a country smaller than West Virginia with a popu-

lation of less than four million. The NATO-led Implementation

Force (IFOR) — rechristened the Stabilization Force (SFOR)

after its first year7 — was one of the most intensive peacekeeping

missions in history. You could not drive more than a few miles

along the country’s rutted, potholed roads without encounter-

ing a NATO patrol or checkpoint. And this mighty armed pres-

ence faced no real military opposition. The paramilitary bands

who had been so effective at killing civilians and intimidating the

UN’s blue helmets during the Bosnian war had withdrawn to the

shadows with scarcely a shot fired in defiance.

Even in this relatively unchallenging environment, the

force’s American commanders were reluctant to confront the

war crimes suspects roaming openly in their new domain. More

than seventy of these suspects had been identified by the Hague

Tribunal, and the NATO peacekeepers were provided with their

names and pictures. But they were not a priority. Far from it. The

soldiers were under orders that the fugitives should be arrested

only if they were encountered in the normal conduct of NATO

duties. In practice, that meant never.

This timidity was shaped by history. Three years earlier, dur-

ing a humanitarian relief mission in Somalia, the US military

launched an operation to arrest local militia leaders who were

hampering the delivery of food supplies. On October 3, 1993,

a force of US Rangers, Delta Force soldiers, and Navy SEALs

[3]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 3 11/19/15 12:20 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

were sent into Mogadishu to seize two lieutenants of the Somali

warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid. The outcome was a disaster.

Two Black Hawk helicopters were shot down by militiamen,

eighteen US servicemen were killed, and seventy-three were

wounded. It was the bloodiest battle America had fought since

Vietnam.

The experience was seared into the collective memory of the

US officer corps. The operation had been approved by the chair-

man of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Colin Powell, as one of his last

acts in office. He left the job three days before the Mogadishu

raid was launched, and his successor, General John Shalikash-

vili, had to clear up the mess. The video footage of the corpse of

an American soldier being dragged through the streets was being

shown on television when Shalikashvili was sworn in. The gen-

eral never tired of reminding civilians of that when they came to

the Pentagon trying to persuade him to send American troops on

the hunt for war crimes suspects in Bosnia. It was not an experi-

ence he was in a hurry to repeat. He was the living embodiment

of the “Mogadishu syndrome,” the intense risk aversion that

dominated American military thinking throughout the Balkan

episode and which lasted until September 11, 2oo1.

It was not just a psychological hangover. The US generals

deployed in Bosnia firmly believed that their chance of winning

an extra star depended heavily on their ability to achieve zero

casualties on their watch. The overwhelming priority was force

protection. American troops were under orders to don full body

armor when they left their bases, and whenever possible to stay

in their vehicles.

American self-defense measures may have been the most

pronounced, but none of the NATO contingents in IFOR (and

later SFOR) were keen on chasing war criminals. In Prijedor,

[4]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 4 11/19/15 12:20 PM

O P E R AT I O N A M B E R S TA R

an epicenter of mass killing during the war, the British garrison

bought takeout pizzas from a restaurant run by one of the sus-

pects. The guidelines coming down the chain of command were

clear: there would be no “mission creep,” and no arrests.

As Charles Crawford, the British ambassador in Sarajevo at

the time, recalls: “The rules of engagement said in effect: ‘Don’t

pick him up, unless you actually trip over him.’ Anything that

involved going off the road even ten yards was regarded as ‘not

being in the course of your normal duties.’ ” 8

It was not a sustainable policy either for Bosnia or for NATO.

Once the fugitives became convinced of their impunity, they

went about making the country unmanageable. Meanwhile

NATO’s credibility was corroding daily under the caustic deri-

sion of the world press, which delighted in portraying the grand

alliance as hapless and cowardly.

The first impetus toward a change in policy came in the spring

of 1996 from the Dutch. The Netherlands was haunted by the fail-

ure of its army to protect the people of Srebrenica from slaughter

the previous summer. The small Dutch UN garrison in the Mus-

lim enclave had been overwhelmed by the Serb attack and had

been provided only token and belated air support from UN head-

quarters. The garrison capitulated and handed over Muslim civil-

ians who had taken refuge in the Dutch compound under the UN

flag. In so doing, they sent thousands of men and boys to their

death. Nearly a year later, the Dutch were keenly aware that no

one had been held accountable. The ICTY had been established

in their capital, The Hague, but it had hardly any defendants in

its cells. They were as empty as the international community’s

promises of justice.

The Dutch government set about lobbying Washington for

a change in NATO’s approach, and the Clinton White House

[5]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 5 11/19/15 12:20 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

agreed to review the matter. But in reality the administration had

no interest in doing anything practical, at least not until after the

presidential elections in November of that year. Clinton’s poll-

ster, Dick Morris, had surveyed voters when American soldiers

were first deployed to Bosnia and found that, of all the chal-

lenges facing the military, the “arrest of war criminals was the

one Americans opposed most.” 9 And Karadžić only had 2o per-

cent name recognition. Most Americans had no idea who these

people were. Politically, there were far more reasons to do noth-

ing than to act.

The White House nonetheless commissioned a study. Robert

Gelbard, the assistant secretary of state for International Narcot-

ics and Law Enforcement, was told to put together an assessment

of whether a manhunt in Bosnia was militarily and politically

feasible. Gelbard was as qualified as anyone in Foggy Bottom to

venture an opinion. He had firsthand experience of a manhunt

operation in Latin America. In 1989, during his stint as the ambas-

sador to Bolivia, he had masterminded the capture of one of the

country’s most feared figures, Colonel Luis Arce Gómez.

As the interior minister in a military junta in the early eight-

ies, Arce Gómez ran death squads that abducted and executed

dissidents. He hired a fugitive Nazi war criminal, Klaus Barbie, as

an adviser and staged an armed takeover of the narcotics trade.

He was unofficially known as “the minister for cocaine.” When

the junta fell and was replaced by a democratically elected gov-

ernment in La Paz, Arce Gómez went on the run to avoid narco-

trafficking charges in Bolivia and the United States. He remained

at large for six years.

In early December 1989, US intelligence was told that the

fugitive would be visiting his family ranch near Santa Cruz for a

party, so Ambassador Gelbard made an approach to the Bolivian

[6]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 6 11/19/15 12:20 PM

O P E R AT I O N A M B E R S TA R

government and offered three options: “We do nothing, you get

him, or we get him together.” The government chose the third,

and on December 11 a joint team of three dozen Navy SEALs and

Bolivian special police raided the Santa Cruz ranch and seized

Arce Gómez. The next day he was on a plane to Florida to stand

trial, where he was sentenced to spend almost twenty years in jail.

With that experience behind him, Gelbard’s instinct was that

it was eminently feasible for America to track down war crimi-

nals in Bosnia. It was just a question of political will. He set

about writing a proposal with the help of Andrew Bair, a young

American diplomat Gelbard had recruited from the UN ranks

in Sarajevo. They circulated their feasibility study on detention

operations in the ex-Yugoslavia in the fall of 1996, arguing that

the effort would have to include the British, Dutch, and French

as well as the Germans, because operations would probably

have to be run out of US bases in Germany. As for which agency

should take the lead, Gelbard and Bair laid out a range of options,

including US Army Special Forces, Navy SEALs, the CIA, the FBI,

and the Drug Enforcement Administration.

“There was clear high-level interest at the State Department,

and from Madeleine Albright [the ambassador to the UN] but

strong opposition from any entity that would have to be asked to

actually do it,” Gelbard recalled.10

Louis Freeh, the FBI director, was furious the bureau had

even been included as a candidate for what he viewed as a wild-

goose chase in a far-off country. Gelbard and Bair faced even

stiffer resistance from the Pentagon. To Secretary of Defense

William Cohen, and to Shalikashvili, the whole manhunt idea

smelled of mission creep. They argued strenuously that their

soldiers had been sent to Bosnia with a single task, to keep the

peace, and manhunting was not part of that mandate. It would

[7]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 7 11/19/15 12:20 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

bog down their forces in a sideshow that was not essential to

American national security and could easily cause casualties.

On the other side of the argument stood the determined fig-

ure of Albright, who was weeks away from becoming secretary

of state. She maintained that Bosnia would be ungovernable as

long as the top war criminals continued to enjoy impunity. The

policy battle was fought all the way to the White House, and the

breakthrough came only after Clinton won reelection in Novem-

ber 1996. The victory released him from the fear that American

casualties in Bosnia might derail his ambition to be a two-term

president.

At a White House principals meeting a few days after the elec-

tion, Clinton listened to objections from Secretary Cohen, Gen-

eral Shalikashvili, and the director of Central Intelligence, John

Deutch, before overruling all of them. He declared the United

States was duty-bound to pursue the arrests. Vice President Al

Gore backed him enthusiastically. It was the moral course of

action, Gore said.

Once his commander in chief had spoken, Shalikashvili had

little choice. Since a decision had been made, the general said,

the country should use the best tool for the job — US Army Spe-

cial Forces. Cohen looked dismayed. Albright turned around in

her seat and shook Gelbard’s hand. It was a victory in principle,

but there were still months of bureaucratic wrangling ahead

before the first arrest would be made.

Early in 1997, however, the wheels began to turn. David

Scheffer, the State Department’s first ambassador at large for

war crimes, went to Europe in the first week of February to sell

the idea to the allies, with mixed results. The British, Dutch, and

Germans were more open to the idea than the French. The Amer-

icans stressed to their counterparts in Paris that they would

[8]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 8 11/19/15 12:20 PM

O P E R AT I O N A M B E R S TA R

not be making a commitment in blood. They were simply being

invited inside the planning loop with no obligation to contrib-

ute troops to any operation. According to Scheffer, that did not

seem to make the idea any easier to digest: “The French looked

as if they were experiencing collective constipation. They were

pained with our legal explanations and had difficulty with their

own domestic legal authorities. For them, the risks included fail-

ure, the taking of hostages, the consequences for the peace pro-

cess, the lack of secrecy, and the fear that French soldiers would

be the first victims of any Serb retaliation.” 11

The French officials delayed a decision until Albright made

her first trip to Paris as secretary of state at the end of February.

Another few weeks were lost, but ultimately Paris agreed at least

to talk about the initiative.

From the end of February, a committee began to convene reg-

ularly in The Hague, chaired by the Dutch and bringing together

representatives of five nations: the United States, the United

Kingdom, the Netherlands, France, and Germany. It convened

in total secrecy. Gelbard and Bair did not go through the arriv-

als lounge when they flew in for meetings but were picked up by

a black limo on the tarmac at Schiphol Airport in Amsterdam and

driven straight to The Hague.

In Dutch government offices, the five countries wrestled

over the law and terminology that would underpin the manhunt.

No one liked the term “rendition,” and all the defense officials

in the room were nervous about their soldiers carrying out civil-

ian arrests, which was normally the constitutional role of the

police. It did not help that the 1995 Dayton Accords provided

no direct mandate for such operations, despite the effort of the

State Department to get the language written into the text. The

American diplomats at the talks barely managed to fend off Serb

[9]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 9 11/19/15 12:20 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

demands for a war crimes amnesty to be included in the final

treaty.12 That would have rendered the Hague Tribunal pointless

at a stroke.

In the absence of clear wording in the treaty, the State

Department and its allies in European foreign ministries pieced

together a legal case for NATO arrests from a combination of

documents. They argued the Dayton Accords and three UN

Security Council Resolutions — establishing the ICTY in 1993,

implementing the Dayton Accords in 1995, and then establish-

ing SFOR at the end of 1996 13 — together created a legal frame-

work that empowered the military to use all necessary means to

uphold the peace and enforce the will of the tribunal.

A formula was developed to get around legal qualms, involv-

ing a complex minuet of interlocking moves. When an arrest plan

was ready, SFOR would request assistance from NATO member

states to ensure fulfillment of its mission. At the same time, the

ICTY prosecutor would request assistance in making arrests.

The NATO secretary-general would order SFOR troops to coop-

erate with the prosecutor. Special forces would be dispatched

from their home country with the mandate to act on SFOR’s

request to assist in the performance of the mission, which would

include detention of indicted fugitives “if the circumstances and

tactical situation permitted.” The special forces would then find

and detain the suspect, delivering him within hours to tribunal

lawyers whose job it was to perform the actual arrest.14 It was

an elaborate and somewhat fragile legal contraption that, to the

relief of the lawyers who put it together, was never comprehen-

sively challenged at the tribunal.

The military preparations were straightforward by compar-

ison. A secret joint planning operation was established at the

European headquarters of US Special Operations Command at

[ 10 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 10 11/19/15 12:20 PM

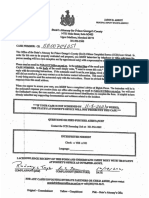

P O S T- D AY T O N B O S N I A

Bosnia in the aftermath of war, split by the Dayton Accords into two halves, the Republika

Srpska and a Bosniak-Croat Federation, and then divided by NATO into three military zones,

run by the British, Americans, and French.

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24a.indd 11 12/2/15 5:16 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

Patch Barracks near Stuttgart, which had been a German Pan-

zer base during the Second World War. The operation was code-

named Amber Star and included special forces, intelligence

agencies, and police officials from the five countries involved.15

THE FIRST HURDLE for Amber Star was to write up a feasibil-

ity study, laying out various tactical options and rating the risk

involved in each.16 But from the very beginning there were deep

differences of opinion on how to go about the task. Three basic

variants were on offer: Amber Star could start by pursuing the

top targets; it could begin with more junior war crimes suspects

who had less protection, the low-hanging fruit, and work its way

up; or it could try to do both, going for a single sweep that caught

as many indictees as possible at the same time.

In general, the bigger the prize the harder the pursuit. Ratko

Mladić, the Bosnian Serb commander who orchestrated the

siege of Sarajevo and the capture of Srebrenica, was wanted for

genocide and crimes against humanity. Catching him would have

been a coup, but he had withdrawn to a mountain stronghold

befitting a Bond villain, a nuclear bunker Tito had built at Han

Pijesak, in eastern Bosnia. There he was surrounded by concen-

tric rings of bodyguards.

Mladić’s mountain hideout, Villa Javor, appeared on the sur-

face to be a modest hunting lodge, but a heavy metal door inside

its garage hid a shaft that led deep into the rock.17 The bunker was

equipped with fresh water supplies, air filtration systems, and a

command center. The quarters were spartan but there was a dou-

ble bed for the general and a cot outside the door for his most

trusted guard, his last line of defense. Risk-averse and highly dis-

ciplined, Mladić hunkered down at Han Pijesak until the summer

[ 12 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 12 11/19/15 12:20 PM

O P E R AT I O N A M B E R S TA R

of 1997, when he decided that even Tito’s nuclear shelter was not

secure enough and slipped across the Drina River into Serbia.

There, Mladić could rely for protection on the man who

did more than any other to unleash war in Yugoslavia, Slobo-

dan Milošević. In 1997, Milošević had yet to be indicted, in part

because Western capitals still viewed him as the guarantor of the

Dayton peace deal and consequently withheld intelligence from

the ICTY that would have incriminated him directly. He was

only charged in May 1999, after he had started his fourth war, in

Kosovo. He became the first sitting head of state to be indicted

by an international tribunal.

In the spring of 1997, Milošević’s Croatian counterpart, Pres-

ident Franjo Tudjman, was also under investigation for his role

in the ethnic cleansing of Muslims in central Bosnia and the mur-

der of Serb civilians in the wake of a major offensive across the

Croatian Krajina in the summer of 1995. But Tudjman died in

December 1999 while those investigations were still under way.

At the time Amber Star was launched, Karadžić was the only

feasible target among Yugoslavia’s wartime leaders. Only he was

under indictment and potentially within reach. Although he had

been forced by Washington to step down from his formal party

and government functions in 1996, he continued to wield influ-

ence behind the scenes and traveled around Bosnia with impu-

nity. There was no mistaking his gray pompadour hairstyle, his

large retinue of bodyguards, and his distinctive Audi A8. But no

one sought to challenge him, let alone arrest him.

Outside Sarajevo, a detachment of Italy’s famous Garibaldi

Bersaglieri Brigade, with their magnificent cockades of black

wood-grouse feathers in their helmets, manned a critical junc-

tion near the Bosnian Serb wartime capital in Pale. When

Karadžić’s motorcade approached the crossing, the plumed

[ 13 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 13 11/19/15 12:20 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

soldiers would turn their backs to the road and face Sarajevo,

choosing not to encounter the wanted man in the “normal

course” of their duties.

Yet despite an outward show of nonchalance, Karadžić was

deeply anxious about his future and even more frightened than

NATO of the Serb gunmen assigned to protect him. Some of

them worked for Milošević’s security apparatus, and Milošević

had no wish to see his former protégé testify before the tribunal.

William Stuebner, a former US soldier and diplomat recruited as

a special adviser to the Hague Tribunal, was struck by Karadžić’s

air of vulnerability in the spring of 1996, when he visited his

office at the Famos car-parts factory in Pale: “He was nervous. He

had bitten his nails. Every time a helicopter went over he went

to the window. He said, ‘If they come for me, there will be blood

on carpet.’ I said, ‘I know these people. It will be your blood.’ We

talked for two hours. He was very interested in turning himself

in. It was the first time I realized just how very scared he was of

his own guards. He knew Milošević had people around him ready

to kill him.” 18

Stuebner tried to persuade Karadžić to hand himself in, tell-

ing him The Hague would offer an opportunity to present his

case on the world stage. Karadžić appeared to be convinced, ask-

ing his Cambridge-educated aide, Jovan Zametica, to make the

arrangements. “He said Jovan will be the intermediary. He would

have been lifted by helicopter, and would have gone to a US air-

craft carrier to make a broadcast saying how he was going to

defend the honor of the Serbs . . . Radovan’s dream was going to

The Hague with smart lawyers and winning, becoming a national

hero and eclipsing Milošević.” 19

Had the plan succeeded, a twelve-year multimillion-dollar

manhunt would have been averted. But at the eleventh hour,

[ 14 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 14 11/19/15 12:20 PM

O P E R AT I O N A M B E R S TA R

Karadžić balked, most likely out of fear of assassination. Then as

the months went by after NATO’s arrival, with no sign that the

alliance had any interest in making arrests, he started to think

that he might not only survive if he stayed put; he might even

have a political future.

In February 1997, Karadžić staged a comeback tour intended

to demonstrate he was still a force to be reckoned with. Point-

edly, he went to Banja Luka, the biggest town in the west of the

Republika Srpska (the Serb-run half of Bosnia) and the political

base of his former deputy and chief rival, Biljana Plavšić, a biology

professor who believed in the genetic superiority of the Serbs.

She was an enthusiast for ethnic cleansing and would be indicted

by the Hague Tribunal for genocide three years later. But in 1997

the West backed Plavšić as a lesser evil than Karadžić. She had

agreed to allow Bosniaks and Croats to return to their villages in

the Republika Srpska, while Karadžić’s activists sought to sabo-

tage any such resettlement effort.

On the stump, Karadžić publicly derided the Hague Tribunal

as “ridiculous.” Less than a year earlier he had been fretting over

whether to turn himself in. Now he dismissed the very notion as

absurd. “It is not a court or a tribunal,” he said. “It is a form of

lynching for the whole nation.” 20

Simply by showing up in Banja Luka, Karadžić was directly

challenging Western efforts to reshape Bosnia, while under-

lining the impotence of both the ICTY and NATO. To cross the

Republika Srpska from Pale, his motorcade had breezed past

SFOR troops, including an American patrol.

“His Audi A8 and escort went straight past a US Humvee col-

umn,” General Montgomery “Monty” Meigs, the US commander

at the time, recalled with regret. “The chairman of the Joint

Chiefs of Staff just didn’t want to get involved. Mission creep is

[ 15 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 15 11/19/15 12:20 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

a legitimate concern, but we missed an opportunity to break up

the old leadership structure.” 21

Ultimately, Karadžić’s brazen defiance helped swing sup-

port in Western capitals behind an arrest strategy in 1997. The

Amber Star talks in The Hague and Stuttgart eventually led to a

provisional agreement to pursue him and thirty-five more-junior

suspects of all ethnicities. The lesser targets would be divided

among the various NATO contingents according to which zones

they lived in. The exception would be the capture of Karadžić.

That great endeavor would be shared, in a flagship joint opera-

tion that would show the alliance at its best.22 At least, that was

the plan.

The Karadžić snatch operation was to rely more on brute

force than guile, much to the anxiety of the British who wor-

ried that the Americans would ask them to demonstrate their

commitment to Amber Star by taking part in a mission they had

no hand in planning. Officials from the Foreign and Common-

wealth Office (FCO) nervously reported back to London from

the Amber Star talks:

On military channels, we understand that it is a large scale

conventional military operation to surround Pale and fight

their way into the point at which Karadžić is presumed to be

hiding. This is not the way UK forces would approach the

problem . . . [The Americans] may ask for UK participation in

a “Sarajevo cell” . . . to pursue planning on Karadžić . The

Defence Secretary is likely to take a cautious line until we have

more answers on the nature of any operation.23

Kim Darroch, the head of the FCO’s Eastern Adriatic Depart-

ment at the time,24 warned in June 1997 that there was “a strong

[ 16 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 16 11/19/15 12:20 PM

O P E R AT I O N A M B E R S TA R

chance” that the Americans and French would ask British sol-

diers to participate in the Karadžić assault.

This would present us with a difficult choice. There are

obvious political and bilateral arguments for a positive

response. But there would also be good reasons for caution.

An operation against Karadžić, however carefully planned,

will be highly hazardous . . . The question is hypothetical

for the moment. No proposition has been put to us. Were such

an approach made, military factors would need to weigh

heavily in any response. Political factors cannot sensibly be

viewed in isolation. 25

The British had their own plans to consider. For several

weeks they had been preparing a separate operation in their sec-

tor in western Bosnia. It involved simultaneously detaining three

provincial Bosnian Serb officials — the former mayor, police

chief, and hospital director — who had run the notorious con-

centration camps around the town of Prijedor.* The Hague had

delivered sealed indictments against the “Prijedor Three,” and

the British military command could not wait to be rid of them.

They ran much of the organized crime in the zone, while using

intimidation and terror tactics to prevent the return of Muslim

refugees.

However, the Prijedor operation had to be put on hold until

Washington and the Stuttgart cell could make a decision about

Karadžić and the other Amber Star targets. In a memo on June 17,

Darroch noted: “If they decide to put Karadžić on hold for the

moment — and depending on how quickly they wish to mount a

* See chapter 3.

[ 17 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 17 11/19/15 12:20 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

wider operation against lesser indictees — they may be happy for

the UK to go ahead separately with an operation on the Prijedor

Three. They have asked for two weeks grace to consider the Pri-

jedor issue.” 26

However, time was slipping away. The British military had

wanted to carry out the Prijedor operation by the end of June, ner-

vous that operational secrecy would be blown if they waited too

long. Yet the Amber Star committee was talking about six more

weeks for “tactical planning, training and rehearsal, subject to

political agreement from the capitals of the countries involved.” 27

All that preparatory work and committee discussion would

last well into September 1997, which is when municipal elec-

tions were supposed to take place across Bosnia. Organizing the

vote was a priority for the international community, and sub-

stantial resources were being provided in the hope that the poll

would diminish the nationalist parties and reshape the political

landscape.

A controversial military operation just before the election

could entrench Serb national resentment and work in favor of

Karadžić’s hardline Serb Democratic Party (Srpska Demokratska

Stranka, or SDS). That meant that if there was to be a grand

Amber Star operation it would most likely have to be put off until

October or later.

In the event, it never happened at all. The idea of large-scale

joint arrest operations by the five allied armies, sweeping up

Karadžić and nearly three dozen other suspects, was a hugely

ambitious scheme, but it was brought crashing down by a single

twenty-eight-year-old French officer, Hervé Gourmelon. The

Gourmelon affair, as it came to be known, would not only eclipse

Amber Star but also sour Franco-American military cooperation

in Bosnia for years to come.

[ 18 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 18 11/19/15 12:20 PM

O P E R AT I O N A M B E R S TA R

GOURMELON, a French army major stationed in Sarajevo since

1995, was instructed by his French superiors in SFOR to liaise

with the Bosnian Serb leadership. Short, blond, and charming,

Gourmelon did not seem to be subject to normal military rules.

He lived in an apartment in town rather than in the French bar-

racks. He was a highly cultured aesthete who seemed to have

hours to spare for drinking coffee and discussing literature and

fine art. He was a fervent admirer of the British romantic painter

J. M. W. Turner, and he usually had a small drawing pad and pen-

cils in his pocket to knock off quick sketches in idle moments.

Gourmelon would beguile the Bosnian women working at

SFOR headquarters, bringing them pastries and showing them

pictures of an idyllic life back in the French countryside, com-

plete with a blond wife and three blond children, an old manor

house with extensive grounds, and a collection of vintage cars.

His rank was an infantry chef de bataillon, equivalent to com-

mandant or major, but he seemed more like a French James

Bond, a cultured spy. It was never clear which intelligence

agency, if any, he worked for. When things turned sour, French

intelligence, both military and civilian, disowned him. But for

a regular infantry major, he was given some surprisingly sensi-

tive jobs. As one of the very few French officers who had been

in Sarajevo during the war for the UN and then stayed on under

NATO, Gourmelon was better connected in Pale than anyone

else in SFOR. He had talked his way into Karadžić’s confidence,

meeting with the separatist leader at least once a month. He sent

reports of these encounters with the man he code-named Teddy

all the way up the French chain of command to the director of

military intelligence, Lieutenant General Bruno Elie.

[ 19 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 19 11/19/15 12:20 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

The CIA was suspicious of Gourmelon’s striking success and

his apparently cozy relationship with the Bosnian Serb hierar-

chy. The Sarajevo station put the urbane Frenchman under sur-

veillance and came to the conclusion the flow of intelligence was

mostly going the wrong way. Gourmelon appeared to be giving

away more valuable information than he was receiving. Every

time an SFOR security sweep through Pale was planned, the

French major would drive up the road from Sarajevo in his Volk-

swagen Golf to visit Serb officials on the other side of the front

lines. After rummaging through Gourmelon’s apartment and

searching his car, the CIA believed it had proof that he had been

leaking classified cables.

The evidence was sent to Langley and quickly landed on the

desk of General Wesley Clark, the commander of US forces and

NATO in Europe, at his headquarters in Mons, Belgium. Clark

immediately took the documents to his French counterparts.

“You have a spy in your midst!” he yelled at them.

The French reaction could best be described as a shrug. Gour-

melon was called back to Paris for interviews, some of which US

intelligence officers were allowed to observe. The French argu-

ment to the Americans was that it was Gourmelon’s job to win

Karadžić’s confidence even if he perhaps used “questionable”

tactics on occasion. And to demonstrate Paris’s faith in its man,

he was sent back to Sarajevo in the fall of 1997 to take up his pre-

vious duties.

The CIA was furious but finally comprehended what had been

going on under its nose in Sarajevo. Gourmelon was not a rogue or a

traitor. He had simply been carrying out the French version of force

protection. Rather than sending out lots of heavily armed soldiers

on every fact-finding or liaison mission, Gourmelon simply let the

Serb leadership know what SFOR was doing and where its patrols

[ 20 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 20 11/19/15 12:20 PM

O P E R AT I O N A M B E R S TA R

were going. The idea was no one would be taken by surprise and

there would be no chance of a spontaneous shootout. Forty-five

French soldiers had been killed over the course of the war, more

than any other UN contingent, and Paris did not want to lose any

more lives in a “misunderstanding” with Karadžić’s bodyguards.

There was little Washington could do about the French pol-

icy, but the CIA was ultimately able to get rid of Gourmelon.

In December 1997, a Bosnian teenage girl appeared at the cen-

tral Sarajevo police station claiming she had been assaulted and

named her attacker as Hervé Gourmelon. Soon afterward the

CIA station chief received a copy of the girl’s testimony from

a police contact along with some vivid pictures of her inju-

ries, including a bite mark on her thigh. He showed them to his

French counterpart, and within hours Gourmelon was on a plane

out of the country, so fast in fact his clothes and personal pos-

sessions were left behind in his apartment and had to be sent on

later by his colleagues. French officials told journalists asking for

an explanation of the sudden disappearance of a popular figure

that there had been a “murky sex scandal.” 28

Female colleagues at SFOR described Gourmelon as some-

times impatient and emotional, but insisted his attitude toward

women, though flirtatious, was always courteous and respectful.

He could have had a hidden dark side, or he could have been set

up by either Bosnian or US intelligence services, both of whom

had been irritated to see him return to Sarajevo. He was certainly

never prosecuted for the alleged assault. Whatever the truth, the

French military was not about to get itself mired in a scandal that

would inevitably become public.*

* I was not able to track Gourmelon down. He does not have a listed address

or phone number, and former military colleagues said they thought he did

not want to be found.

[ 21 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 21 11/19/15 12:20 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

Officially at least, the top brass stuck by their man. Gour-

melon was never subjected to disciplinary action and was even-

tually promoted to lieutenant colonel.29 Franco-American

cooperation in Bosnia, on the other hand, never recovered. The

joint plan to grab Karadžić went no further than the drawing

board in Stuttgart. The French kept liaison officers at Patch Bar-

racks who continued to attend Amber Star meetings, but intel-

ligence sharing and joint planning with the Americans was dead

from that moment on. British diplomats reported that while

France “has favoured continuing efforts against lesser indictees

in their sector,” General Clark was “apparently determined to

concentrate on Karadžić only.” 30

But on both fronts, the FCO report noted, there had been

“little progress towards workable plans.” From the point of view

of Scheffer, the whole episode provided American officialdom a

pretext to dodge involvement in the manhunt: “Unfortunately

the [Gourmelon] affair scared off the Pentagon from coordinat-

ing any Karadžić operations for a long time thereafter and gave

the cynics within the Washington bureaucracy plenty of reasons

to back away from arrest strategies.” 31

The United States had its own Karadžić-hunting operation,

code-named Green Light, but it existed largely as a tasking order

for the CIA and DIA (Defense Intelligence Agency) to keep an

eye out for the fugitive. They failed to track him down, and the

military was clearly unprepared to commit large resources to the

operation, especially while relations with the French in Bosnia

were so dysfunctional.

By late May 1998, Scheffer described the arrest strategy as

“dead in the water . . . The British remained supportive, but the

French appeared to have shut down, no doubt still chastened

by the [Gourmelon] affair. There was no real operation against

[ 22 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 22 11/19/15 12:20 PM

O P E R AT I O N A M B E R S TA R

Karadžić or Mladić . . . Karadžić might have been located within

days if a full-court press were applied to the challenge.”

Secretary of Defense Cohen remained adamantly opposed

to the whole project and continued to insist until his last days

in office that detentions were not in the SFOR mandate. He and

the generals played a waiting game until even Albright seemed to

lose her stamina.

Scheffer, the most persistent advocate for the pursuit of the

war criminals, was told in November 1999 that Albright no lon-

ger wanted him involved in the Karadžić pursuit. He would

henceforward be excluded from all meetings on the subject.32

He never learned if he was squeezed out because of pressure

from the Pentagon, the intelligence agencies, or the French.

His determination to go after Karadžić had made him plenty

of enemies.

For all the champagne-fueled triumphalism in Paris in May

1997, Operation Amber Star was rendered virtually meaningless

before it could get off the ground, hobbled by the Gourmelon

affair, Franco-American distrust, and the ingrained resistance

of the Western military establishments. British officials noted

as early as 1997 that the focus for planning was shifting away

from Stuttgart. It was gravitating instead toward General Clark’s

NATO headquarters in Mons. Decisions were also devolving to

individual capitals.

Each of the five nations involved in Amber Star ultimately

took action to arrest second-tier war crimes suspects in their

zones, and the Stuttgart meetings were used for “deconfliction,”

ensuring national special forces units did not pursue the same

quarry at the same time and stumble into a shootout with one

another. It was a banal end for such an ambitious and expensive

undertaking.

[ 23 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 23 11/19/15 12:20 PM

THE BUTCHER’S TRAIL

The initiative that finally broke the paralysis surrounding

war crimes arrests was everything Amber Star was not: cheap,

improvised, and unexpected. As would happen again and again

in the course of the Balkan manhunt, a small operation by a few

determined individuals succeeded where the grandiose plans of

military juggernauts failed.

[ 24 ]

Butcher's Trail_page layouts_24.indd 24 11/19/15 12:20 PM

You might also like

- Secure DC Omnibus Committee PrintDocument89 pagesSecure DC Omnibus Committee Printwamu885No ratings yet

- Music Theory For Electronic Music ProducersDocument247 pagesMusic Theory For Electronic Music ProducerswillibongaNo ratings yet

- Collision Course - NATO - Russia - Kosovo PDFDocument361 pagesCollision Course - NATO - Russia - Kosovo PDFAndrei Alexandru Micu100% (2)

- Crisis: The Anatomy of Two Major Foreign Policy CrisesFrom EverandCrisis: The Anatomy of Two Major Foreign Policy CrisesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Lawsuit Against D.C. Over Medical Care at The D.C. JailDocument55 pagesLawsuit Against D.C. Over Medical Care at The D.C. Jailwamu885No ratings yet

- The First Conspiracy: The Secret Plot to Kill George WashingtonFrom EverandThe First Conspiracy: The Secret Plot to Kill George WashingtonRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (121)

- USDA List of Active Licensees and RegistrantsDocument972 pagesUSDA List of Active Licensees and Registrantswamu885No ratings yet

- Bece English Language Past Questions 2018Document5 pagesBece English Language Past Questions 2018Anonymous lnC6IDg100% (4)

- American Literature: Lecture OneDocument27 pagesAmerican Literature: Lecture OneLiza Salvador VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- Solids Flow Meter, Type DLM Solids Flow Feeder, Type DLD: Operating ManualDocument20 pagesSolids Flow Meter, Type DLM Solids Flow Feeder, Type DLD: Operating ManualArturMirandaNo ratings yet

- Selective Remembrances: Archaeology in the Construction, Commemoration, and Consecration of National PastsFrom EverandSelective Remembrances: Archaeology in the Construction, Commemoration, and Consecration of National PastsNo ratings yet

- The Butchers Trail, Chapter 1 ExcerptDocument24 pagesThe Butchers Trail, Chapter 1 Excerptwamu885No ratings yet

- The World's Greatest Military Spies and Secret Service AgentsFrom EverandThe World's Greatest Military Spies and Secret Service AgentsNo ratings yet

- Rebel Yell The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson by S. C. GwynneDocument10 pagesRebel Yell The Violence, Passion, and Redemption of Stonewall Jackson by S. C. GwynneSimon and Schuster100% (2)

- Road from Sarajevo: British Army Operations in Bosnia, 1995-1996From EverandRoad from Sarajevo: British Army Operations in Bosnia, 1995-1996No ratings yet

- From Russia With Thanks, Major George Racey Jordan DiariesDocument28 pagesFrom Russia With Thanks, Major George Racey Jordan DiariesklinnskuttNo ratings yet

- Innocent Abroad: An Intimate Account of American Peace Diplomacy in the Middle EastFrom EverandInnocent Abroad: An Intimate Account of American Peace Diplomacy in the Middle EastRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1)

- Legacy WAR The People: A AgaiDocument32 pagesLegacy WAR The People: A AgaiCollier MeyersonNo ratings yet

- But Not in Shame: The Six Months After Pearl HarborFrom EverandBut Not in Shame: The Six Months After Pearl HarborRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (18)

- Sierra Leone: Revolutionary United Front: Blood Diamonds, Child Soldiers and Cannibalism, 1991–2002From EverandSierra Leone: Revolutionary United Front: Blood Diamonds, Child Soldiers and Cannibalism, 1991–2002Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Yang Murray History of Military Necessity Ch2 in Historical Memories of The Japanese InternmentDocument42 pagesYang Murray History of Military Necessity Ch2 in Historical Memories of The Japanese InternmentLuiz FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Remember the Liberty!: Almost Sunk by Treason on the High SeasFrom EverandRemember the Liberty!: Almost Sunk by Treason on the High SeasNo ratings yet

- Declassified: 50 Top-Secret Documents That Changed HistoryFrom EverandDeclassified: 50 Top-Secret Documents That Changed HistoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (30)

- L F. Stone's Weekly: A Strategy Only Fellow Con-Men Can AppreciateDocument4 pagesL F. Stone's Weekly: A Strategy Only Fellow Con-Men Can AppreciateJohn NadaNo ratings yet

- The World's Greatest Military Spies and Secret Service Agents: The History of Espionage – True Crime StoriesFrom EverandThe World's Greatest Military Spies and Secret Service Agents: The History of Espionage – True Crime StoriesNo ratings yet

- Anglo-Soviet Circles That Created Kissinger by Scott Thompson - 6 PDFDocument6 pagesAnglo-Soviet Circles That Created Kissinger by Scott Thompson - 6 PDFyunusNo ratings yet

- Workers Vanguard No 594 - 18 February 1994Document12 pagesWorkers Vanguard No 594 - 18 February 1994Workers VanguardNo ratings yet

- Secrets of the Cold War: US Army Europe's Intelligence and Counterintelligence Activities Against the Soviets During the Cold WarFrom EverandSecrets of the Cold War: US Army Europe's Intelligence and Counterintelligence Activities Against the Soviets During the Cold WarRating: 2 out of 5 stars2/5 (4)

- American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy's Forgotten CrisisFrom EverandAmerican Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy's Forgotten CrisisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (51)

- Gothic Ripples 84Document12 pagesGothic Ripples 84gensgeorge4328No ratings yet

- Review of Peter Grose, - Operation Rollback - by Johanna GranvilleDocument6 pagesReview of Peter Grose, - Operation Rollback - by Johanna GranvilleJohanna Granville100% (1)

- H 1992Document60 pagesH 1992Hal ShurtleffNo ratings yet

- T5 B17 Misc Articles On Terrorism FDR - Entire Contents - 1st Pgs For Reference 295Document6 pagesT5 B17 Misc Articles On Terrorism FDR - Entire Contents - 1st Pgs For Reference 2959/11 Document Archive100% (2)

- Military Reminiscences of the Civil War: Autobiographical Account by a General of the Union ArmyFrom EverandMilitary Reminiscences of the Civil War: Autobiographical Account by a General of the Union ArmyNo ratings yet

- 1996-01-01 President Nixon and The Role of Intelligence in The 1973 Arab-Israeli WarDocument10 pages1996-01-01 President Nixon and The Role of Intelligence in The 1973 Arab-Israeli Warmary engNo ratings yet

- Stay the Hand of Vengeance: The Politics of War Crimes TribunalsFrom EverandStay the Hand of Vengeance: The Politics of War Crimes TribunalsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- The Rise of the G.I. Army, 1940–1941: The Forgotten Story of How America Forged a Powerful Army Before Pearl HarborFrom EverandThe Rise of the G.I. Army, 1940–1941: The Forgotten Story of How America Forged a Powerful Army Before Pearl HarborRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (9)

- Washington's Undersea War: The secret development of the submarine in the American RevolutionFrom EverandWashington's Undersea War: The secret development of the submarine in the American RevolutionNo ratings yet

- Military Reminiscences of the Civil War (Vol.1&2): An Autobiographical Account by a General of the Union Army (Complete Edition)From EverandMilitary Reminiscences of the Civil War (Vol.1&2): An Autobiographical Account by a General of the Union Army (Complete Edition)No ratings yet

- Hanover; Or The Persecution of the Lowly: A Story of the Wilmington MassacreFrom EverandHanover; Or The Persecution of the Lowly: A Story of the Wilmington MassacreNo ratings yet

- Letter From D.C. Open Government Coalition On Secure DC BillDocument46 pagesLetter From D.C. Open Government Coalition On Secure DC Billwamu885No ratings yet

- D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser Public Safety Bill, Spring 2023Document17 pagesD.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser Public Safety Bill, Spring 2023wamu885100% (1)

- Letter From Dean Barbara Bass Update On Residents and Fellows UnionizationDocument3 pagesLetter From Dean Barbara Bass Update On Residents and Fellows Unionizationwamu885No ratings yet

- Razjooyan CommentDocument1 pageRazjooyan Commentwamu885No ratings yet

- Affidavit in Support of Arrest of Larry GarrettDocument3 pagesAffidavit in Support of Arrest of Larry Garrettwamu885No ratings yet

- February 2022 Council Quarterly Meeting MinutesDocument5 pagesFebruary 2022 Council Quarterly Meeting Minuteswamu885No ratings yet

- Tridentis LawsuitDocument9 pagesTridentis Lawsuitwamu885No ratings yet

- In The United States District Court For The District of ColumbiaDocument55 pagesIn The United States District Court For The District of Columbiawamu885No ratings yet

- Tridentis LawsuitDocument9 pagesTridentis Lawsuitwamu885No ratings yet

- Captain Steve Andelman Lawsuit Against MPDDocument25 pagesCaptain Steve Andelman Lawsuit Against MPDwamu885No ratings yet

- Letter To Governor Hogan On Funding Abortion TrainingDocument3 pagesLetter To Governor Hogan On Funding Abortion Trainingwamu885No ratings yet

- NZCBI Reply To Holmes Norton Visitor Pass Inquiry - 2023 - 01 - 11Document1 pageNZCBI Reply To Holmes Norton Visitor Pass Inquiry - 2023 - 01 - 11wamu885No ratings yet

- Judge Trevor N. McFadden OpinionDocument38 pagesJudge Trevor N. McFadden Opinionwamu885No ratings yet

- Undelivered: The Never-Heard Speeches That Would Have Rewritten History ExcerptDocument11 pagesUndelivered: The Never-Heard Speeches That Would Have Rewritten History Excerptwamu8850% (1)

- Public Defender Service For DC Lawsuit Against BOP Alleging Unequal TreatmentDocument33 pagesPublic Defender Service For DC Lawsuit Against BOP Alleging Unequal Treatmentwamu885No ratings yet

- Lawsuit by Family of Darryl BectonDocument29 pagesLawsuit by Family of Darryl Bectonwamu885No ratings yet

- FordBecton Complaint Filed in Arlington, VA Circuit Court On 03.11.2022Document29 pagesFordBecton Complaint Filed in Arlington, VA Circuit Court On 03.11.2022wamu885No ratings yet

- Lawsuit Alleging Pattern of Racial and Gender Discrimination in MPD Internal AffairsDocument56 pagesLawsuit Alleging Pattern of Racial and Gender Discrimination in MPD Internal Affairswamu885No ratings yet

- WAMU Council Meeting Minutes 202112Document5 pagesWAMU Council Meeting Minutes 202112wamu885No ratings yet

- Jerry Holly ChargingDocument5 pagesJerry Holly Chargingwamu885No ratings yet

- D.C. Court of Appeals On McMillanDocument7 pagesD.C. Court of Appeals On McMillanwamu885No ratings yet

- Karon Hylton-Brown LawsuitDocument60 pagesKaron Hylton-Brown Lawsuitwamu885No ratings yet

- WAMU Community Council Meeting Minutes 09 2021Document6 pagesWAMU Community Council Meeting Minutes 09 2021wamu885No ratings yet

- 2017-08-23 - USDA IR - Jerry HollyDocument3 pages2017-08-23 - USDA IR - Jerry Hollywamu885No ratings yet

- 2015-02-11 USDA Inspection Report - Jerry HollyDocument1 page2015-02-11 USDA Inspection Report - Jerry Hollywamu885No ratings yet

- 2015-10-07 USDA Inspection Report Jerry HollyDocument1 page2015-10-07 USDA Inspection Report Jerry Hollywamu885No ratings yet

- 2021-05-06 - USDA Inspection Report - Jerry L HollyDocument2 pages2021-05-06 - USDA Inspection Report - Jerry L Hollywamu885No ratings yet

- Biology Paper Two (CSEC)Document14 pagesBiology Paper Two (CSEC)Mario PalmerNo ratings yet

- Learning Plan: Analogy To Show Relationships of WordsDocument2 pagesLearning Plan: Analogy To Show Relationships of WordsMonaliza PawilanNo ratings yet

- Case Digests On Arts 247 248 249Document35 pagesCase Digests On Arts 247 248 249Jenaro CabornidaNo ratings yet

- Tajweed English Full Pack Master SheetDocument4 pagesTajweed English Full Pack Master Sheetmaryamhassansaleh4949No ratings yet

- Hostel Management SystemDocument11 pagesHostel Management SystemMaryamNo ratings yet

- Krolikowski - Vertical Densification. The Structural Architecture of BBVA HQ Tower Mexico City - VoRDocument8 pagesKrolikowski - Vertical Densification. The Structural Architecture of BBVA HQ Tower Mexico City - VoROrcunNo ratings yet

- An Album of Indian Big Tops (History of Indian Circus)Document5 pagesAn Album of Indian Big Tops (History of Indian Circus)A Surya TejaNo ratings yet

- Cloud Computing and SaasDocument18 pagesCloud Computing and SaasSyairah HusnaNo ratings yet

- Lindt Phases 1 and 2Document30 pagesLindt Phases 1 and 2api-24727320550% (2)

- Exegetical Essay - Part 3Document7 pagesExegetical Essay - Part 3api-583124304No ratings yet

- Legal Doctrines Used in IndiaDocument14 pagesLegal Doctrines Used in IndiaAkanksha PandeyNo ratings yet

- SR Eng Added Seen Passgaes With Key (Telangana)Document7 pagesSR Eng Added Seen Passgaes With Key (Telangana)medigachaithu9No ratings yet

- Entrep Midterm ReviewerDocument6 pagesEntrep Midterm ReviewerRyza Mae BascoNo ratings yet

- Certificate PranayDocument5 pagesCertificate Pranaypranaykaje9765No ratings yet

- Sleep Disorders Lecture Notes 13Document9 pagesSleep Disorders Lecture Notes 13rupal arora100% (1)

- World Teacher's Day CelebrationDocument1 pageWorld Teacher's Day CelebrationMichael LuNo ratings yet

- Roland Factory ResetDocument10 pagesRoland Factory ResetMiguel ReyesNo ratings yet

- Certifications - Process - Document - For - Associates V2.0 PDFDocument28 pagesCertifications - Process - Document - For - Associates V2.0 PDFMadhuri MalayathiNo ratings yet

- PF 11084Document85 pagesPF 11084Laboratorio Hope GlobalNo ratings yet

- Class II AS - 2023-24Document7 pagesClass II AS - 2023-24محمدضيأ الدينNo ratings yet

- The Sacramental Celebration of The Paschal MysteryDocument19 pagesThe Sacramental Celebration of The Paschal MysteryChrizzle TamponNo ratings yet

- Email Sample QuestionsDocument5 pagesEmail Sample QuestionsArmanVerseNo ratings yet

- CLIL - Content and Language Integrated Learning - PresentationDocument14 pagesCLIL - Content and Language Integrated Learning - PresentationTường CátNo ratings yet

- Celtic Cross SpreadDocument1 pageCeltic Cross SpreadDean PlattsNo ratings yet

- Jeremy Tan Resume and CVDocument3 pagesJeremy Tan Resume and CVapi-359540985No ratings yet

- How To Clean An Agilent GCMS Ion Source - Customer Community 25mar2021Document35 pagesHow To Clean An Agilent GCMS Ion Source - Customer Community 25mar2021Kakha ChogovadzeNo ratings yet