Toyota

Toyota

Uploaded by

api-375761159Copyright:

Available Formats

Toyota

Toyota

Uploaded by

api-375761159Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Toyota

Toyota

Uploaded by

api-375761159Copyright:

Available Formats

Toyota Paper

Toyota

Chairman: Hiroshi Okuda

By Kiichiro Sakichi in 1933 within Toyoda Automatic Loom,

Founded:

independent as of 1937

Headquarters: Toyota City, Japan (US HQ in Torrance, CA)

Philosophy 1. Belief in Mono-zukuri (Making good products); Just-in-time => Lean Management

The Toyota 2. Principle of Customer first; Customer Satisfaction No.1, Quality No.1

Way: 3. Respect for People (employees); Mono-zukuri is Hito-zukuri (Making good product is

equal to making good people); Mutual trust of management and employees

Business Daihatsu Motor Products: the Lexus line of luxury cars

Units: Co., Ltd.

Prius (hybrid-powered [gas

New United Motor and electric] sedan)

Manufacturing, Inc.

Cars, pickups, minivans, and

Toyota Motor Credit

SUVs including:

Corporation

Toyota Motor o Camry

Sales, U.S.A., Inc. o Celica

Toyota Motor o Corolla

Thailand Company Limited o 4Runner

And, as of 1984: o Echo

Toyoda Automatic o Land Cruiser

Loom o Sienna

Aichi Steel o WiLL

Toyoda Machine

Works V-8 Tundra pickup truck

Toyota Auto Body Industrial vehicles

Aisin Seiki Cellular phones

Nippon Denso Financial services

Toyota Gosei

Kanto Auto Works

Koito Works

Aisan Industries

Manufacturing: Japan (15 plants), Rest of East Asia (17), North America (8), Latin America (5),

Europe (4), Middle East & Southwest Asia (4), Africa (2), Oceania (1)

R&D: Japan (1 HQ, 1 tech center, 1 proving ground), USA (1 engineering, 1 design),

Belgium (1 engineering, 1 design), France (1 design)

Financial Data Millions $ (FY ends 12/31)

2000 1999

Sales 119,656 105,797

Net Income 4,540 3,746

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 1

Toyota Paper

Employees: World 214,631 183,917

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 2

Toyota Paper

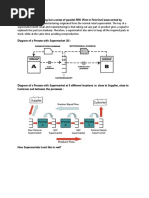

Site Background: Toyotas Tsutsumi factory is located in Toyota City, close to the worldwide

headquarters of Toyota Motor company. In and around this site in Aichi

Prefecture are situated a total of 12 Toyota plants.

This factory was opened in 1970 and employed 5,700 workers by 1999.

This makes it the third largest Toyota plant in Japan, by workforce.

The factory occupies an area of 600,000m2 on a site nearly twice as large.

As of March 1999, according to our data, the main products being

produced here were the Camry, Caldina, Corona, Mark II, Vista, Windom

(ES300). However, weve been told to expect to see the production of

Lexus luxury vehicles at the plant so either there have been some changes

to the plants lines or some of our information is wrong.

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 3

Toyota Paper

Toyota Paper: Introduction

Welcome to the MIT Sloan 2001 Japan/Korea Trip Toyota Team Paper

In this paper we aim to present some information essential to understanding Toyota and its place

in the Japanese economy and the global auto industry, to prepare for our visit to the company

and its production facilities on Monday 26th March 2001.

We have designed the paper as easily-digestible chapters which can be read stand-alone in

spare moments while in transit around airports and on buses, to suit the specialized needs of Trip

participants.

To cut down the overhead in reading this paper we have as much as possible removed filling

sections such as transitions from chapter to chapter, and kept introductory remarks extremely

brief.

The chapters are as follows:

ONE State of the global auto industry

The main trends in automobile production and marketing today

TWO Characteristics of the Japanese auto industry

Whats special about the way this industry developed?

THREE History of Toyota

A straightforward account of the timeline from 1937 to 2001

FOUR Current company facts

Financials and production figures; stated strategy and direction

FIVE Toyota Production System

A primer, with glossary of terms, to this famous system

SIX Toyotas relationships

How Toyota deals with its employees, suppliers and customers

If you have any further questions, please contact one of us:

Aaron Fyke

Gary Mi

Tony Palumbo

Yukihiro Wada

Grace Webber

March 19th, 2001

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 4

Toyota Paper

ONE: State of the Global Auto Industry

In 2001, there are four major trends impacting the global auto industry:

Overcapacity, mergers and alliances

With overcapacity estimated at around 30%

(Economist Feb 11th 1999) or the capacity to

produce 23 million more cars per year than the

market will take (Robert Eaton of Chrysler, quoted in

the Economist), this is an industry in trouble. We

have seen mergers and alliances, for instance

Daimler-Benz with Chrysler. There is speculation

(Jac Nassar of Ford) that there is only room for six

volume car makers in the future: two in Japan, two in

Europe and two in the US. Smaller manufacturers

without the highest production expertise and

economies of scale will simply disappear.

Economic downturn

Over the last couple of years, demand for new

vehicles has slowed, putting pressure on automakers all round the world to slim down

their operations, close unproductive plants and focus on core strategic activities.

Shifting consumer demands

Led by the US, consumers are no longer satisfied

with mid-sized family cars. Increasingly they are

demanding more specialized vehicles such as

SUVs, minivans and light trucks.

The adjacent graph from the Economist shows the

dramatic shift in sales from cars to light trucks.

Increasing variety in demand is causing a growing

emphasis on flexible manufacturing systems to

enable rapid response to market variations, and

mass-customized product to be ordered for the

customer straight off the production line.

Removal of European trade barriers

Until 2000, Europe had strict quota limits on the import of Japanese cars. This had

encouraged investment by Japanese car firms in manufacturing plants within European

borders and had also protected the domestic markets of the smaller European

manufacturers. With the removal of these trade barriers, the European market is being

opened up to more competition. However, it remains to be seen how far governments

will go in removing the safety net from their domestic auto industries. Industry

consolidation would lead to plant closures, with large-scale job losses, which are difficult

for many European governments to swallow, and the calls for intervention and subsidy

introduction could be too loud to be ignored.

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 5

Toyota Paper

TWO: Characteristics of the Japanese Auto Industry*

From followers to leaders

For many years, Japanese companies struggled to produce automobiles up to the standards of

the US and Europe. They were producing much lower volumes, which hindered them from

achieving scale economies. They also lacked learning, technology and the ability to produce

quality that the US companies had. Many of the products developed by the Japanese car

companies in the first half of the 20th century were manufactured from kits supplied by, or based

on designs reverse-engineered from, foreign competitors. The up-and-coming leaders of the

Japanese automotive industry spent their time touring production facilities in the US, learning

manufacturing techniques and automobile engineering from (it seems) proud and willing tutors at

Ford and GM.

During the 1960s and 1970s the Japanese automobile industry continued to work on process

improvements to increase their quality and production efficiency, and on their own designs of

smaller, more-affordable cars to suit their domestic market more appropriately. They developed

their supplier networks of subsidiaries and partly-owned companies to provide them with the high-

quality components they needed.

Suddenly from the 1970s/1980s, Japanese cars had become well-made and inexpensive. In

manufacturing systems the Japanese had leapt ahead of the west they had so diligently studied

earlier in the century. In the coming years, car manufacturers from all over the world would be

studying Japanese automakers (especially Toyota) to learn their production techniques. Indeed

these firms had become the new most-admired engineering organizations in the world.

From domestic market to exporters

At the dawn of the Japanese car industry, there were many manufacturers vying principally for

domestic business. Large volumes of imports were arriving from overseas on Japanese shores,

since Japanese consumers preferred the more reliable imports.

Capital available to the Japanese firms was fairly limited and they concentrated on developing

their production to compete in their domestic market. Yet, as improvements in efficiency and

quality came through, and excess capacity grew as home market growth slowed, Japans auto

exports grew rapidly. By 1974, Japan had displaced West Germany as the worlds largest

automobile exporter, and by 1976 most of Japans auto output was exported.

History of government intervention, direction and regulation

From 1936 onwards, successive Japanese governments had protectionist policies and levied

huge import taxes (e.g. 40%) on foreign automobiles. Support for domestic manufacturing was

seen as a way of preventing the foreign currency drain of imports.

The Ministry of Commerce & Industry (MCI), after 1949 the Ministry of International Trade &

Industry (MITI), set tariff policies. MITI also provided low-interest loans with tax privileges for

investment, tried to reduce competition in an overcrowded industry, and urged the industry to

focus on particularly promising market segments.

When Japanese products had achieved a quality leadership position and well-recognized brands

in their home market, MITI removed the now-redundant import tariffs.

*

most data for this page is taken from Michael Cusumanos 1991 book, The Japanese Automobile

Industry

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 6

Toyota Paper

THREE: History of Toyota

Toyota started in 1937, growing out of Toyoda Automatic Loom Works, headed by Sakichi Toyoda.

Toyota Motor Company was founded by Kiichiro Toyoda, Sakichi's son. Due to the fact that

Toyoda had a meaning in Japanese, it was decided, after a large contest, that the company

name would be changed to Toyota, which held no meaning in Japanese.

In 1950 the company experienced its one and only strike. This strike proved to be a major turning

point in the history of Toyota as Toyotas labor policies and management style emerged from this

stoppage. Both sides were firmly committed to establish the principles of mutual trust amongst its

members, a corporate philosophy that still guides Toyotas growth today.

Due to the lack of resources in post war Japan, a production system that concentrated on

improving efficiency and eliminating waste emerged. Taiichi Ohno, the systems founder, based

TPS on the principles of continuous improvement, and Just-in-time manufacturing. Lean

production, as it later became known is a major factor in the reduction of inventories and defects

in the plants of Toyota and its suppliers, and it underpins all the operations across the World.

Toyota launched its first car in 1947 and production of vehicles outside Japan began in 1959.

The first expansion overseas for Toyota was in a small plant in Brazil. Toyota claims to believe in

locating its operations locally to provide customers with the products they need where they need

them. Whether this is actually the case, or only really true when mandated by government policy

is another story. Nevertheless, in addition to their manufacturing facilities, Toyota has design and

R&D facilities located throughout the world, servicing the three major car markets of Japan, North

America and Europe.

Toyota Production Volumes

5

Yearly Production (millions of vehicles)

Domestic Production

4 Total Production

0

1935 1936 1937 1940 1957 1960 1972 1980 1982 1988 1996 1999

Year

Source, Toyota Motor Company

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 7

Toyota Paper

FOUR: Current Facts

1. Business Segments

Automotive:

The automotive business involves the design, manufacturing and sale of passenger cars,

recreational vehicles, sport utility vehicles, minivans, trucks and related parts. Automobiles are

manufactured mainly by Toyota and Daihatsu Motor Co. Automobile parts are manufactured by

Toyota and their suppliers, such as companies like Denso Corporation.

These products are sold through Tokyo Toyo-Pet Motor Sales Co., Ltd. and other dealers. Some

sales, to certain large customers, are made directly by Toyota in Japan, bypassing the dealership

network. Overseas, sales are made through Toyota Motor Sales, U.S.A., Inc. and other

distributors and dealers. Volkswagen and Audi vehicles are also sold through the Toyota

dealership network in Japan.

Financial Services:

This business involves providing loans and leases to customers and loans to dealers. The Toyota

Finance Corporation handles this business in Japan, whereas Toyota Motor Credit Corporation

and others provide sales financing of Toyotas products and the products of its affiliates,

overseas.

All other:

Other businesses include the manufacturing and sale of industrial vehicles such as forklifts and

logistics systems, and the design, manufacturing and sale of prefabricated housing,

telecommunications and other business. Industrial vehicles are manufactured by Toyoda

Automatic Loom Works, Ltd. and sold through dealers in Japan and distributors and dealers

overseas. Housing is manufactured by TMC and sold through domestic housing dealers. In the

telecommunication business, IDO Corporation provides domestic telephone services. Toyoda

Tsusho Corporation engages in the purchase and sale as well as import and export of various

products.

2. Business results (fiscal year) (million yen)

1996 1997 1998

Period April 1995 April 1996 April 1997

- March 1996 - March 1997 - March 1998

Consolidated accounts Net Sales 10,718,740 12,243,834 11,678,397

Income before income tax 420,801 708,299 828,791

Net income 256,977 385,915 454,349

Vehicle production (units) 3,849,817 4,293,682 4,233,371

Vehicle sales (units) 4,148,641 4,559,515 4,456,344

Employees 146,855 150,736 159,035

Unconsolidated accounts Net sales 7,957,152 9,104,792 7,769,486

Income before income tax 340,734 620,412 625,640

Net income 182,534 303,312 365,140

Vehicle production (units) 3,174,300 3,500,782 3,421,729

Vehicle sales (units) 3,250,681 3,543,778 3,468,544

. Consolidated subsidiaries (261 companies): domestic consolidated subsidiaries

(152 companies), overseas consolidated subsidiaries (109 companies)

. Affiliates accounted for under the equity method (60 companies): domestic affiliates

(44 companies), overseas affiliates (16 companies)

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 8

Toyota Paper

3. Outlook and Strategy

Mid-term and long-term management strategy

Toyota plans to enhance its competitiveness in the global market through advanced technology,

and improvements in production efficiency and sales.

In technological development, Toyota aims to lead other automakers in the field of

environmental technologies. These include targets such as reduced emissions,

improved fuel efficiency, and higher vehicle recoverability rate. To meet these

criteria, Toyota is investing to develop technology in hybrid electric vehicles, fuel cell

vehicles and other next-generation automobiles with the aim of commercializing them

Prius hybrid vehicle from Toyota,

as quickly as possible. available in Europe (image source:

www.globaltoyota.com)

Toyota plans to continue promoting cost reduction efforts such as the common use of vehicle

platforms, reductions in component types and the streamlining of production lines.

In order to respond to the customers overall needs, which are bound to expand from automobiles

to include other related areas, Toyota intends to develop its business strategically by effectively

allocating management and other resources to its finance, information and communication

businesses.

Product Diversification

Toyota traditionally has regarded customers principally as buyers of automobiles and of a very

limited range of closely related products, such as financing and replacement parts. Now, Toyota is

deepening its relationships with automobile customers through new products and services, such

as innovative packages that combine financing and insurance. And it is diversifying into markets

where it develops customer relationships through products unrelated-or indirectly related-to

automobiles, such as cellular telephones and credit cards.

Finance business

Much of the increased value that Toyota plans to cultivate downstream in its value chains is in

financial services. As Toyota expands its activity in the financial sector, it needs to manage risk

systematically and manage operations efficiently. Therefore Toyota placed all the financial

services operations under a newly-established financial management company in July 2000.

Information technology development

Toyota intends to get onto the cyberspace map through multimedia ventures

supporting value-added functions in automobiles, such as navigation. Toyotas

GAZOO website, which began as an automobile information service, is being developed into a

provider of diverse services. Its most developed functions provide price estimates and

brochureware for Toyota vehicles and the nearest located dealers, and it also hosts a growing

array of virtual shops for Internet shopping, including access to music downloading sites.

Toyota is the second-largest shareholder of KDDI Corporation (with 13% of shares), formed in

2000 through the merger of Toyotas IDO subsidiary and KDD corporation. KDDI Corporation is a

leading provider of international and cellular telephone services in Japans highly competitive

telecommunications industry.

Development of Environmental Technology

Creating automobiles with low environmental impact is no longer "just an option" for Toyota - it

has become a crucial part of corporate strategy. The development of technology to reduce

environmental impact enables Toyota to sit in the driving seat setting new global standards, so

gaining competitive advantage in exploiting them. The Prius hybrid vehicle was launched to

critical acclaim and much positive PR. In addition, leading Toyotas sales growth in Japan is its

small car, the Vitz, and its derivative models, which are very popular for their high fuel efficiency.

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 9

Toyota Paper

FIVE: The Toyota Production System

Toyota is known for quality vehicles, produced the world over. However, what Toyota has done

exceptionally well, is implement a manufacturing system so successful it has influenced not just

auto making, but manufacturing standards across many other products all over the world.

Through the Toyota Production System (TPS) Toyota has managed to cut costs, reduce time to

market, and dramatically improve quality. This allows Toyota to be one of the few companies able

to compete simultaneously as a premium and as a low cost producer.

There are several important aspects to TPS. These relate to either cost reduction, or quality

improvement, or both. The underlying philosophy of TPS is a relentless desire to continually find

and remove waste wasted time, wasted money, wasted material. This attitude results in

continual improvement of quality and efficiency. Some of the mechanisms for this improvement

are listed below:

JIT (Just in Time) Just in time inventory control reduces the amount of inventory in a system to

its bare minimum. Material is only provided when needed. This is opposed to having large

amounts of inventory being piled up waiting to be processed (WIP work in progress). JIT has

many advantages over conventional systems. Eliminating WIP inventories results in reduced

holding costs. JIT also improves quality as it allows for quick detection of quality problems.

Because units are only produced on an as needed base, there will not be the situation in which

large amounts of defecting WIP needs to be reworked. JIT also tightens the relationship between

the producer and supplier, allowing for better linking of engineering, product development and

quality control as it becomes in the suppliers best interest to reduce variability in their production

line.

5 Whys Quality Control For lack of a better name, this is an example of the thinking in the

Toyota plants. Errors are not vehicles for blame. Instead, they are symptoms of root causes

which must be investigated. Therefore, if an error is detected, two things will occur. The first is

that the production line will be stopped to ensure the error is fixed and will not happen on

subsequent vehicles. Second, an investigation is launched to identify the root cause of the error

(so called the 5 Whys because the question why? is asked five times to tunnel to the source of

the error).

SMED (Single Minute Exchange of Dies) A die is the shaped surface of a metal stamping

press which determines the final shape of the produced part. The dies of a manufacturing press

need to be aligned to extremely tight tolerances to avoid damage to the equipment. Due to the

lengthy process of exchanging dies and the high cost of stopping the production line, many

manufacturing companies would produce thousands of similar parts before changing dies. This

led to high batch quantities and large inventories. JIT required the flexibility to be able to reduce

setup time for dies to a matter of minutes. This allowed for individual parts to be made on an as-

needed basis, reducing large inventories, improving quality, and balancing throughput.

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 10

Toyota Paper

Pull System Manufacturing

Central to the idea of lean manufacturing and JIT inventory controls is a pull system of

manufacturing. This is contrasted from the other manufacturing system, which is a push

system. There are situations when either situation is optimal; however, Toyota has made great

progress by using a predominantly pull approach.

A push system is one wherein demand for the customer is forecast and then the required

number of units is produced. These units are sold on the market. Stockouts result in lost

revenue and excess production must be deeply discounted to be sold. A pull system however is

one where no product is made until it is requested. Therefore, as parts are needed for

production, and not before, they are produced and integrated into the assembly. Use of a

kanban, or marker, card, or tag, is done to indicate that more parts are needed and should be

produced. This limits the amount of inventory in the system and reduces the factorys

vulnerability to fluctuating demand.

History of the Toyota Production System

The Toyota production system was not devised to revolutionize the manufacturing world. Indeed,

it took several decades of improvement to do that. Rather, it was born out of necessity. Many of

the best innovations and changes in the auto industry have been done, not because the company

wanted to, but because the company had to, and Toyota was no exception.

In post war Japan, resources were scarce and the auto industry faced a number of problems.

The domestic market was tiny and demanded a wide range of vehicles, the Japanese work force

was not willing to be treated as a variable cost or as interchangeable parts, the Japanese

economy was starved for capital and foreign exchange, and the outside world was full of huge

motor-vehicle producers, ready to defend their markets. Mass production was roaringly

successful and Eiji Toyoda (Toyotas founding family) and Taiichi Ohno (designer of TPS)

determined that mass production would never work in Japan. (By 1950, the cumulative

production of Toyota, after 13 years of operation, was 2685 automobiles, as compared to the

7000 vehicles Fords Rouge plant was putting out per day.)

Toyota needed a system that could be flexible and scalable. They could not afford to have one

production line dedicated to a single line of cars they only had a few lines in total. So, because

they could not afford multiple production lines with dedicated stamping presses, they began

looking for ways in making the whole system more flexible. Hence was born the notion of single

minute exchange of dies, and Heijunka (described below) a means of producing several

vehicles on one line in accordance with the demand mix. Toyota began developing the JIT

system because they could not afford to purchase large amounts of inventory. Their resource

constraints forced them to adopt the lean manufacturing approach out of sheer necessity to keep

the whole production moving.

Given that Toyota was walking such a precarious line with their production, they had absolutely

no tolerance for quality errors they couldnt afford to. From this, and from the supplier

relationships forged while establishing JIT, Toyota developed the fanatical quality control system

that they are now famous for today. Each of the TPS initiatives of lean manufacturing, waste

reduction, and quality improvement were born out of the necessity to produce in the demanding

environment of post-war Japan.

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 11

Toyota Paper

*

Glossary of Terms

Andon Andon, a Japanese word for lantern, describes the notice board used for quality control.

The board hangs over the aisle between production lines and alerts supervisors to any problem.

In assembly, the board normally indicates the line name in green at the top. When a team

member pulls a cord on the line, the board lights up a number corresponding to the troubled

station in yellow, which then changes to red when the line actually comes to a halt. The board

also shows whether the line stop is temporary or not, and whether the line is starved (body short),

blocked (body full), or stopped by internal problems. This device quickly informs a supervisor of

only what he or she needs to know to take immediate actions and thereby allows a small number

of supervisors to control a large area; it also prompts supervisors to develop countermeasures for

recurring problems in the longer term.

Heijunka This is Toyotas terminology describing the idea of distributing volume and different

specifications evenly over the span of production such as a day, a week, and a month. Under this

practice, the plants output should correspond to the diverse mix of model variations that the

dealers sell every hour.

Kaizen Kaizen literally means changing something for the better. The object of change

usually includes the standardized work, equipment, and other procedures for carrying out daily

production. The purpose is to eliminate waste in seven categories: (1) overproduction, (2) waiting

imposed by an inefficient work sequence, (3) handling inessential to a smooth work flow, (4)

processing that does not add value, (5) inventory in excess of immediate needs, (6) motion that

does not contribute to work, and (7) correction necessitated by defects. Kaizen requires that a

process be first standardized and documented so that ideas for improvement can be evaluated

objectively.

Kanban Kanban means signboard in Japanese. The one used for a part supplied by an

outside supplier indicates the name of the supplier, the receiving area at Toyota, the use-

point inside the Toyota plant, the part number, the part name, and the quantity for one

container. A bar code is used to issue an invoice based on actual part usage.

*

these definitions are taken from HBS case 9-693-019, Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A.,

Inc. 1992 the President and Fellows of Harvard College

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 12

Toyota Paper

SIX: Toyotas Relationships

The Toyota Motor Company has developed a unique relationship network with its employees,

suppliers, dealers and customers. Toyota's most powerful change agent, Mr. Taiichi Ohno,

instituted most of the relationship network. Mr. Ohno achieved many gains for his company while

developing Toyota from a small automotive company into the worlds third largest automotive

company in just four decades. Ohno had a very demanding personality and tremendous

persistence. Many inside Toyota, including the top brass, disliked Ohno. In the end, those whom

Mr. Ohno alienated retired from Toyota while Ohno was forced out of Toyota to finish his working

life in a supplier company. This transition was not necessarily unusual as Toyota and its suppliers

often shared employees such as engineers and managers. This practice was seen as valuable in

sharing information between company networks for improving product quality. Even though the

Japanese take pride in their flexible supplier employee relationships, a strict hierarchy remains

with the assembler, Toyota, at the top. Therefore, Taiichi Ohno, after contributing so much to

Toyota, was shunned in the end.

Toyotas relationships with its Employees

Toyota employees treat each other like family. Their culture fosters the utmost respect for one

another inside and outside the plant. Toyota current employment structure allows employees to

expect lifetime employment. Toyota's guarantees are the result of a strike in 1946. At this time,

with sales depressed, Kiichiro Toyoda of the founding family fired twenty-five percent of the work

force. The union was outraged and staged a sit-in strike at the factory. To resolve the strike,

Kiichiro Toyoda had to resign and accept responsibility for mismanagement. The union accepted

the twenty-five percent termination, in exchange for concessions that revolutionized Toyota's

management-union relations. One concession was lifetime employment, the other was pay tied

to seniority and profitability through bonus payments. In return, Toyota expected employees to

remain loyal for life. Toyota and many Japanese companies instituted an increasing pay scale

linked to employee seniority. This Japanese thread discourages people from migrating from one

company to the next, because an employee's pay is directly linked to company service years and

independent of the employees age. For example, a forty-five year old with five years service

makes the same as a twenty-five year old with five years service, regardless of the task they

perform. This gives incentives for employees, in this system, to stay with one company for life.

With the 1946 strike agreement of employment for life, workers became fixed costs, more

permanent even than capital equipment and production machinery. Out of this situation Toyota

developed a relationship of education and continuous improvement since employees were fixed

costs great investments could be made into improving their value. Other initiatives, such as

quality circles developed, wherein teams of factory workers are expected to develop quality and

cost improvements. Continuous improvements are incremental, a reflection of the Japanese

conservative culture.

Further improvements came. Following on the notion that the employee is a valuable asset, team

leader positions were established for every seven or eight assemblers. The team leaders role is

to ensure that the team members have the resources they need to continue working productively.

Part of this philosophy is evident with regards to stopping an assembly line. If an assembler

cannot perform his/her task in the designated time or work area, the assembler is expected to

stop the line and address the issue. With the team leader in close proximity and quick to

respond, line stops are brief. This link between organizational excellence and product quality is

just one of the benefits of the team environment fostered. Teams working together on the

assembly floor in quality circles resolve issues quickly. Assemblers are expected to generate

solutions to problems, not just identify problems and call management for a solution. This can be

contrasted with the more employee/supervisor hierarchical relationship sometimes experienced

in the non-team environments in the West.

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 13

Toyota Paper

Toyotas relationships with its Suppliers

Toyota has a much tighter relationship with its suppliers than seen at a Western assembly plant.

A Japanese assembly plant has only 300 suppliers while typical Western assemblers have

anywhere from 1000 to 2500 suppliers. The supplier pecking order is designated in tiers. First

tier suppliers are highly involved in the manufacturing and design of the vehicle early in the

process. Typically, first tier suppliers are working on vehicles three years ahead of production. In

addition, their responsibilities are much broader than a Western suppliers. For example,

Western assemblers design the whole car and deliver prints to the suppliers. Suppliers bid on the

exact specifications drawn up, and the assembler awards contracts based primarily on the lowest

bid. Western suppliers rely on most of their profit to come from design changes. This gives

Western assemblers a very strong disincentive to make design changes, even if it would improve

the quality of the product. However, Japanese assemblers specify whole systems: for example, a

braking system must fit within certain space dimensions and be able to stop the car within a

certain distance. With such liberty in specifications, designers can design in low cost, instead of

the Western method of cost cutting to win the bid. Since Toyota has their suppliers perform most

of the design, Toyota's design and engineering staff is smaller than a Western manufacturers.

Even though the suppliers are incurring design and engineering costs in their parts, Japanese

suppliers are lower cost than Western suppliers, since Japanese suppliers can leverage their

design cost savings on new model releases.

After production begins, continuous improvement initiatives focus on quality and costs. The

assembler and supplier will work together to improve the supplier's performance. In this sense it

is very much a collaborative relationship. For example, Toyota will incur the cost of sending TPS

experts to the supplier. Toyota funds these efforts through shared gains. Toyota and its suppliers

work together to divide the cost savings so that both companies benefit. The rewards are aligned

with the desired behavior.

Western automotive manufacturers maintain relationships with several suppliers to avoid

subjecting themselves to the power of any one supplier. Toyota follows this practice as well.

Toyota will maintain contracts, where financial beneficial to do so, with a primary supplier, and a

secondary supplier. Both will produce a certain quantity of parts for Toyotas line. However, if

either supplier starts performing poorly in terms of cost or quality, Toyota can then shift the

proportions of parts purchased from one supplier to the other. This shifting of purchases is

enough to send a signal that Toyota is looking for improvements, without the need of cutting off

the supplier completely.

To motivate their suppliers to reduce inventory costs and improve incoming quality, Toyota

requires frequent deliveries to its factory and has their suppliers carry the inventory necessary to

support this. This is discussed in the previous section under JIT. If a quality defect occurs and

rework becomes required, the supplier rework will be equal to the inventory; hence the supplier

will be motivated to keep inventory at a minimum. Again the rewards are aligned with the desired

behavior.

The Japanese model establishes lean production in their value chain to analysis cost and

continuous improvement. The assembler and supplier work together to maximize efficiency. The

mind set is supplier cost plus profit, instead of the Western mind set market price minus discount.

Incrementally cost savings are shared and mutually respected.

Toyotas relationships with its Customers and Dealerships

In Japan the Toyota Dealership network consists of five channels Toyota, Toyopet, Auto, Vista

and Corolla. The dealerships are named Toyota Vista, Toyota Corolla, etc. Each channel sells a

portion of the total Toyota product range. For example, one channel may sell less expensive

models, another sportier ones, and so forth. This enables Toyota to market to different groups of

customers. Every channel clearly identifies the Toyota brand name to establish a link from

manufacturer to customer. Unlike the American and European dealerships, Toyota owns all the

dealerships in the supply chain.

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 14

Toyota Paper

Each channel is directly tied into the product development process. During the entire

development period for a new car model, staff members from the channel are on loan to

development teams. This helps bring the voice of the customer into the design phase of the

process. A Toyota employee knows exactly what the customer wants. Often, Western engineers

can be surprised when they learn what their customers truly desire. The Toyota dealership sales

force is well-educated, being comprised typically of college graduates, who have undergone an

intensive training program at the Toyota University, studying sixty courses mostly related to

marketing. Once the students graduate the Toyota University they begin selling cars. Toyota

salespeople also have a tremendous knowledge of the engineering attributes of the vehicles they

sell, in contrast to Western salespeople who are more commonly professional negotiators with

very little engineering or marketing knowledge.

The Japanese salespeople are assigned to dealerships in teams of seven or eight, similar to the

teams discussed at the assembly site. Within the dealerships, the focus of the groups work is to

solve their customers' problems. The dealerships keep open communication channels with the

manufacturer continuously exchanging information. Employees in the dealerships take as equal

an ownership in Toyota vehicles as the assemblers that build Toyotas in distant factories. The

amount of ideas and customer feedback that is captured at the dealerships are typically lost at

Western dealerships. This is an important channel for determining improvements to the vehicles

quality and performance.

Outside of the dealerships, Toyota salespeople sell door-to-door. The Toyota salesperson can

then know as much about their customer's family as the family physician and stock broker

combined, for example, age of parents, age of children, the number of vehicles, age of the

vehicles, the amount of available parking space, etc. The salesperson utilizes the data and

optimizes their sales calls to be most effective. Also, the salesperson uses their knowledge of

their customers to suggest the most appropriate product. Most automobile orders are placed

directly onto the factory, as opposed to buying off the lot. In keeping with Toyotas lean inventory

system, Toyota dealerships in Japan have very little inventory, while Western dealerships have on

average sixty days of inventory.

For the Western manufacturers, forecasting to demand is critical and often wrong. Occasionally,

vehicles sit on the dealer lot for many months, because they have an undesirable color or

options. The customers ultimately pay for this excessive inventory. The associated inventory

holding cost adds no value to the vehicle and is simply a loss. However, by being able to

respond, through flexible manufacturing, to a customers order within six weeks, Toyota is able to

encourage more orders directly from the factory. Since the Toyota sales force communicates

directly with the factories, the manufacturer knows exactly what the customer demand is at any

one time. This assures Toyota the ability to optimize the factories and the right mix and quantity

of vehicles. Western factories need to depend on the less effective communication link with the

independent dealerships, who themselves have their own objectives for inventory. This causes

excess inventory holding costs, adding to the cost of the vehicle.

All of Toyota, from assembler to the salesperson, respect each other like family. They all work for

the same company and their profit sharing and job security depend on each other. Salespeople

usually stay at their assigned dealership for long periods of time as they have good incentives to

stay. In addition, the Toyota family is extended to the customer. Salespeople sell vehicles with

the intention of their 'family' to be repeat customers. Also, since Toyota salespeople share

commission from the team's performance there is less unproductive competition between

salespeople for commissions to detract from the customer experience. The Toyota sales team,

much like the approach taken between assembler and supplier, works together to improve each

other's abilities, raising all members' commission.

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 15

Toyota Paper

Sources/Further Reading

General sites of interest:

www.toyota.com

www.globaltoyota.com

www.gazoo.com

www.kddi.com

finance.yahoo.com

Specific articles:

FT.com: HIROSHI OKUDA: Toyota's man of vision, by Alexandra Harney

Japanauto.com: Hiroshi Okuda, Toyota Chairman, Elected to Lead Japan Automobile

Manufacturers Association

APEC 1999: Keynote Speech by Hiroshi Okuda, APEC Symposium on the Asian Economy,

Tokyo, Japan, July 23, 1999

Preview NetClipping http://www.fiepr.com.br/netclip/2000/1505wsj.htm: Founding Clan Vies With

Outsider For a Place at the Top of Toyota May 15, 2000

PeopleSoft.com: ERP Implementation at Toyota

www.economist.com: Wave goodbye to the family car Jan 11, 2001

HBS Case 9-693-019: Toyota Motor Manufacturing, U.S.A., Inc. by Professor Kazuhiro Mishina

and Kazunori Takeda, copyright 1992 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Books:

The Machine That Change The World, 1990, James P. Womack, Daniel T. Jones, and Daniel

Ross, Rawson Associates - New York, Publisher Simon & Schuster New York

The Japanese Automobile Industry, Technology & Management at Nissan & Toyota, 1985

(reprinted 1991), Michael Cusumano, Harvard East Asian Monographs 122

A Fyke, G Mi, C A Palumbo, Y Wada, G Webber 16

You might also like

- Intralox Compliance Letter 2021Document6 pagesIntralox Compliance Letter 2021Celia PaoloniNo ratings yet

- Care and Training of The Trotters and PacersDocument184 pagesCare and Training of The Trotters and PacersLazar SimicNo ratings yet

- MUDIM ZAKARIA Ent.Document25 pagesMUDIM ZAKARIA Ent.Ziza Yusup50% (6)

- Space Age Furniture Company Case StudyDocument11 pagesSpace Age Furniture Company Case StudySimonNo ratings yet

- Toyota Production System GlossaryDocument9 pagesToyota Production System GlossaryJuan Pablo100% (1)

- Together Digital Agency Credentials 11-17 PDFDocument20 pagesTogether Digital Agency Credentials 11-17 PDFAnonymous nFFkqRNo ratings yet

- Our Health Ourselves - Uganda LTD Mem - Articles of Association - FinalDocument86 pagesOur Health Ourselves - Uganda LTD Mem - Articles of Association - Finalagula joseph ogororNo ratings yet

- Plant Manager Director Operations Quality in Washington DC Resume Sanders HolstonDocument3 pagesPlant Manager Director Operations Quality in Washington DC Resume Sanders HolstonSandersHolstonNo ratings yet

- Lean Enterprise Plant Manager in Indiana IN Resume Michael MakarewichDocument3 pagesLean Enterprise Plant Manager in Indiana IN Resume Michael MakarewichMichaelMakarewichNo ratings yet

- LEC-2010 Value-Stream Mapping The Chemical ProcessesDocument5 pagesLEC-2010 Value-Stream Mapping The Chemical ProcessesMustafa Mert SAMLINo ratings yet

- Process Engineer Lean Manufacturing in Freeport TX Resume Douglas WilkinsDocument2 pagesProcess Engineer Lean Manufacturing in Freeport TX Resume Douglas WilkinsDouglasWilkinsNo ratings yet

- QI Macros User Guide 2016 PDFDocument36 pagesQI Macros User Guide 2016 PDFVagnoNo ratings yet

- TOYOTA (Guru)Document49 pagesTOYOTA (Guru)Gurudatt BakaleNo ratings yet

- Inventory Control KaizenDocument32 pagesInventory Control KaizenAriel TaborgaNo ratings yet

- Applications of Statistics SixSigmaDocument30 pagesApplications of Statistics SixSigmaSanz LukeNo ratings yet

- Applying Lean Assessment Tools at A Maryland Manufacturing CompanyDocument11 pagesApplying Lean Assessment Tools at A Maryland Manufacturing Companyg_berry208No ratings yet

- Introduction To Lean Manufacturing: DR K K Sharma 1Document54 pagesIntroduction To Lean Manufacturing: DR K K Sharma 1K K SHARMANo ratings yet

- Airvent FansDocument17 pagesAirvent FansPamela ValleNo ratings yet

- The Two Key Principles of Toyota Production System Were Just in Time and JidokaDocument2 pagesThe Two Key Principles of Toyota Production System Were Just in Time and JidokaF13 NIECNo ratings yet

- Oee For Operators Overall Equipment Effectiveness PDFDocument2 pagesOee For Operators Overall Equipment Effectiveness PDFRayNo ratings yet

- Benchmark ArticleDocument38 pagesBenchmark ArticleMd.Tarik ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- ToshibaDocument6 pagesToshibaYandri Harianda0% (2)

- 1 Lean GlossaryDocument7 pages1 Lean GlossaryHilalAldemirNo ratings yet

- Shook On VSM MisunderstandingsDocument5 pagesShook On VSM Misunderstandingsali al-palaganiNo ratings yet

- Going LeanDocument54 pagesGoing LeanShubham GuptaNo ratings yet

- 1973 TPS Handbook - Chapter 1 - A4Document50 pages1973 TPS Handbook - Chapter 1 - A4jdpardoNo ratings yet

- 3M LeanDocument21 pages3M LeanNAMAN GUPTANo ratings yet

- Value Stream Mapping On Gear Manufacturing CompanyDocument7 pagesValue Stream Mapping On Gear Manufacturing CompanyAmandeep SinghNo ratings yet

- Material Handling AutomationDocument4 pagesMaterial Handling AutomationSundar Kumar Vasantha GovindarajuluNo ratings yet

- HeijunkaDocument6 pagesHeijunkajosegarreraNo ratings yet

- Director Food Manufacturing Operations in USA Resume Alan GoldsteinDocument3 pagesDirector Food Manufacturing Operations in USA Resume Alan GoldsteinAlanGoldsteinNo ratings yet

- QI Macros Quick Start GuideDocument6 pagesQI Macros Quick Start Guidejuande69No ratings yet

- Ch15 IndirectStandDocument10 pagesCh15 IndirectStanddaNo ratings yet

- LBP A3 Example Office Case StudyDocument1 pageLBP A3 Example Office Case StudyOsvaldo ColinNo ratings yet

- Lean MFG - GoldDocument4 pagesLean MFG - Goldpragthedog100% (1)

- Project Report Submitted To: Submitted By:: Operations & Production Management Bba Vi-C Bahria University IslamabadDocument29 pagesProject Report Submitted To: Submitted By:: Operations & Production Management Bba Vi-C Bahria University IslamabadMuhammad DanishNo ratings yet

- A3 Format From LEIDocument2 pagesA3 Format From LEIterhexNo ratings yet

- Indian Footwear Industry AnalysisDocument14 pagesIndian Footwear Industry AnalysisnishankNo ratings yet

- Celitron - Sterilizers - Software Update PDFDocument9 pagesCelitron - Sterilizers - Software Update PDFyahiateneNo ratings yet

- ValueStreamMap (HLI)Document29 pagesValueStreamMap (HLI)Ana Cristina RamirezNo ratings yet

- Charles A. Tryon Jr.-Project Identification - Capturing Great Ideas To Dramatically Improve Your Organization-CRC Press (2015)Document140 pagesCharles A. Tryon Jr.-Project Identification - Capturing Great Ideas To Dramatically Improve Your Organization-CRC Press (2015)wossenNo ratings yet

- Lean Six Sigma Aviation MROs Nadeem MBBDocument4 pagesLean Six Sigma Aviation MROs Nadeem MBBSyedNadeemAhmedNo ratings yet

- Plant: Truck Factory: Kaizen Idea - Sheet Machine No: 5000T PressDocument1 pagePlant: Truck Factory: Kaizen Idea - Sheet Machine No: 5000T PressMoufuja ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- CEOs Commitment To Process Improvement Propels IPL To World Class TRACC 3458Document37 pagesCEOs Commitment To Process Improvement Propels IPL To World Class TRACC 3458Ruddy Morales MejiaNo ratings yet

- Lean Principle On RMSDocument11 pagesLean Principle On RMSAhmad SyihanNo ratings yet

- 2011 Toyota Case StudyDocument5 pages2011 Toyota Case Studycotal7950% (2)

- 3Cs Principle Document Lean ModelDocument9 pages3Cs Principle Document Lean ModelJoaquim ReisNo ratings yet

- SupermarketDocument4 pagesSupermarketvijayakum ar100% (1)

- TQM - 601 Module 12 - Quality Method PDCA and PDSADocument17 pagesTQM - 601 Module 12 - Quality Method PDCA and PDSA512781No ratings yet

- Flight Simulators For Management EducationDocument4 pagesFlight Simulators For Management EducationSana BhittaniNo ratings yet

- CUSUM and EWMA Charts PDFDocument10 pagesCUSUM and EWMA Charts PDFLibyaFlowerNo ratings yet

- INN Product Design and DevelopmentDocument23 pagesINN Product Design and Developmenthsvzsd44100% (1)

- Lean Mro ProductivityDocument6 pagesLean Mro ProductivityDeepak BindalNo ratings yet

- 8D:Corrective Actions Request: Claim N°Document16 pages8D:Corrective Actions Request: Claim N°Alex ReséndizNo ratings yet

- Manufacturing StrategyDocument17 pagesManufacturing Strategycastco@iafrica.com100% (1)

- Going Beyond LeanDocument7 pagesGoing Beyond Leanลูกหมู ตัวที่สามNo ratings yet

- Toyota LEAN ProgramDocument56 pagesToyota LEAN ProgramJohn Christopher ElizonNo ratings yet

- Theory of Constraint and Drum Buffer RopeDocument19 pagesTheory of Constraint and Drum Buffer RopeSandeepNo ratings yet

- Shopfloor Management DefintionDocument6 pagesShopfloor Management DefintionAdetya Ika SaktiNo ratings yet

- Worldwide Operations of ToyotaDocument42 pagesWorldwide Operations of Toyotaniom0250% (2)

- The RULES of WORK A Practical Engineering Guide To ErgonomicsDocument189 pagesThe RULES of WORK A Practical Engineering Guide To ErgonomicsMabano Alit EnriqueNo ratings yet

- Beyond the Tps Tools: Preparing the Soil for a Lean TransformationFrom EverandBeyond the Tps Tools: Preparing the Soil for a Lean TransformationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Math Workplan LSDocument4 pagesMath Workplan LSJohhahawie jajwiNo ratings yet

- NSCC Guided Pathway: Accounting (ACD) - Business and Administration PathwayDocument1 pageNSCC Guided Pathway: Accounting (ACD) - Business and Administration Pathwayapi-385512612No ratings yet

- Classical TuningDocument8 pagesClassical TuningElena Mariana CristeaNo ratings yet

- DysarthriaDocument5 pagesDysarthriaShruti RajivNo ratings yet

- Immediate download ICAEW Accounting Study Manual 2020 Thirteenth Edition Institute Of Chartered Accountants In England And Wales ebooks 2024Document55 pagesImmediate download ICAEW Accounting Study Manual 2020 Thirteenth Edition Institute Of Chartered Accountants In England And Wales ebooks 2024yukkinjuneaNo ratings yet

- Implementation Methodology of MB Lal Committee Recommendations For Automation - 1Document18 pagesImplementation Methodology of MB Lal Committee Recommendations For Automation - 1chhandak beraNo ratings yet

- Public Sensitisation On The Adoption of Renewable Energy in Nigeria: Communicating The Way ForwardDocument9 pagesPublic Sensitisation On The Adoption of Renewable Energy in Nigeria: Communicating The Way ForwardLandon Earl DeclaroNo ratings yet

- Drama Theatrical GenreDocument18 pagesDrama Theatrical Genrekimberlygange23100% (1)

- Manual: Original InstructionsDocument82 pagesManual: Original InstructionsSouhailee raihanounee100% (1)

- Thesis Book ContentDocument3 pagesThesis Book ContentKristine MalabayNo ratings yet

- Vastu Shastra Tips ArchiveDocument6 pagesVastu Shastra Tips Archiverohan.sheethNo ratings yet

- Properties of Matter TestDocument6 pagesProperties of Matter TestCamila SilvaNo ratings yet

- Swot Analysis of Paytm-2019089Document4 pagesSwot Analysis of Paytm-2019089Yogesh GirgirwarNo ratings yet

- Hila - Efa and K To 12 Inclusion PolicyDocument2 pagesHila - Efa and K To 12 Inclusion PolicyJerwin Estares Hila100% (1)

- List of Schools in TamilnaduDocument7 pagesList of Schools in Tamilnaduprince_charming17110% (1)

- Japanese Story The Spider's ThreadDocument2 pagesJapanese Story The Spider's ThreadNard Emsoc100% (1)

- Calvin's Theology: Providentially Evil God Free Corrupt SinDocument5 pagesCalvin's Theology: Providentially Evil God Free Corrupt SinAyra ArcillaNo ratings yet

- Manual Práctica Telefonia IPDocument129 pagesManual Práctica Telefonia IPfesqueda2002No ratings yet

- Green and Pink Doodle Hand Drawn Science Project PresentationDocument8 pagesGreen and Pink Doodle Hand Drawn Science Project PresentationKevin KibirNo ratings yet

- eDocument114 pagesePercy Cusihuaman TorresNo ratings yet

- All 6 Pages - Preeti-2Document6 pagesAll 6 Pages - Preeti-2kutta1944No ratings yet

- People Vs Tomotorgo, 136 SCRA 238Document2 pagesPeople Vs Tomotorgo, 136 SCRA 238Name Toom100% (1)

- Feminist Criticism in The WildernessDocument3 pagesFeminist Criticism in The WildernessRoja SankarNo ratings yet

- Design Calculations of Chiller FoundationDocument15 pagesDesign Calculations of Chiller FoundationStressDyn Consultants100% (1)

- Senior Manager Indirect Tax in Cincinnati OH Resume Linda TattershallDocument2 pagesSenior Manager Indirect Tax in Cincinnati OH Resume Linda TattershallLindaTattershallNo ratings yet

- Sample ContractDocument2 pagesSample Contractraimo lorcamaNo ratings yet