Assigned Case Digests Succession

Assigned Case Digests Succession

Uploaded by

Adrian HughesOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Assigned Case Digests Succession

Assigned Case Digests Succession

Uploaded by

Adrian HughesCopyright:

Available Formats

BEATRIZ NERA, ET AL., vs.

NARCISA RIMANDO

G.R. No. L-5971 February 27, 1911

FACTS:

The only question raised by the evidence in this case as to the due execution of the

instrument propounded as a will in the court below, is whether one of the subscribing

witnesses was present in the small room where it was executed at the time when the

testator and the other subscribing witnesses attached their signatures; or whether at that

time he was outside, some eight or ten feet away, in a large room connecting with the

smaller room by a doorway, across which was hung a curtain which made it impossible

for one in the outside room to see the testator and the other subscribing witnesses in the

act of attaching their signatures to the instrument.

ISSUE:

Whether the attaching of signatures should be done in an actual and physical

presence of the subscribing witness.

HELD:

No, not necessarily. The question whether the testator and the subscribing

witnesses to an alleged will sign the instrument in the presence of each other does not

depend upon proof of the fact that their eyes were actually cast upon the paper at

the moment of its subscription by each of them, but that at that moment existing

conditions and their position with relation to each other were such that by merely casting

the eyes in the proper direction they could have seen each other sign. To extend the

doctrine further would open the door to the possibility of all manner of fraud,

substitution, and the like, and would defeat .the purpose for which

this particular condition is prescribed in the code as one of the requisites in the

execution of a will.

Reiterating the case of Jaboneta vs. Gustilo, the court ruled that “ "The true test of

presence of the testator and the witnesses in the execution of a Will is not whether they

actually saw each other sign, but whether they might have seen each other sign, had they

chosen to do so, considering their mental and physical condition and position with

relation to each other at the moment of inscription of each signature."

But it is especially to be noted that the position of the parties with relation

to each other at the moment of the subscription of each signature, must be such that they

may see each other sign if they choose to do so. This, of course, does not mean that the

testator and the subscribing witnesses may be held to have executed the instrument in

the presence of each other if it appears that they would not have been able to see each

other sign at that moment, without changing their relative positions or existing

conditions.

FAUSTO E. GAN v. ILDEFONSO YAP

G.R. No. L-12190, August 30, 1958

FACTS:

On November 20, 1951, Felicidad Esguerra Alto Yap died of heart failure in the

University of Santo Tomas Hospital, leaving properties in Pulilan, Bulacan, and in the

City of Manila.

REZEILE S. MORANDARTE | Page 1 of 2

On March 17, 1952, Fausto E. Gan initiated these proceedings in the Manila court

of first instance with a petition for the probate of a holographic will allegedly executed by

the deceased.

Opposing the petition, her surviving husband Ildefonso Yap asserted that the

deceased had not left any will, nor executed any testament during her lifetime.

After hearing the parties and considering their evidence, the lower court judge

refused to probate the alleged will. A seventy-page motion for reconsideration failed.

Hence the petition.

The will itself was not presented. Petitioner tried to establish its contents and due

execution by the statements in open court of four witnesses.

ISSUE:

Whether a holographic will be probated upon the testimony of witnesses who have

allegedly seen it and who declare that it was in the handwriting of the testator.

HELD:

NO. The execution and the contents of a lost or destroyed holographic will may not

be proved by the bare testimony of witnesses who have seen and/or read such will. The

will itself must be presented; otherwise, it shall produce no effect. The law regards the

document itself as material proof of authenticity.

"In the probate of a holographic will" says the New Civil Code (Art. 811), "it shall

be necessary that at least one witness who knows the handwriting and signature of the

testator explicitly declare that the will and the signature are in the handwriting of the

testator. If the will is contested, at least three such witnesses shall be required. In the

absence of any such witnesses, (familiar with decedent's handwriting) and if the court

deem it necessary, expert testimony may be resorted to."

The witnesses so presented do not need to have seen the execution of the

holographic will. They may be mistaken in their opinion of the handwriting, or they may

deliberately lie in affirming it is in the testator's hand. However, the oppositor may

present other witnesses who also know the testator's handwriting, or some expert

witnesses, who after comparing the will with other writings or letters of the deceased,

have come to the conclusion that such will has not been written by the hand of the

deceased. (Sec. 50, Rule 123). And the court, in view of such contradictory testimony may

use its own visual sense, and decide in the face of the document, whether the will

submitted to it has indeed been written by the testator.

Obviously, when the will itself is not submitted, these means of opposition, and of

assessing the evidence are not available. And then the only guaranty of authenticity3 —

the testator's handwriting — has disappeared.

REZEILE S. MORANDARTE | Page 2 of 2

You might also like

- 24 Ramos V CondezDocument1 page24 Ramos V CondezJulius ManaloNo ratings yet

- Cam To Cam Sex ChatDocument2 pagesCam To Cam Sex ChatStevensRaahauge480% (2)

- 6 Pineda v. Heirs of Eliseo Guevara PDFDocument13 pages6 Pineda v. Heirs of Eliseo Guevara PDFjuan dela cruzNo ratings yet

- Dominion Insurance V CADocument3 pagesDominion Insurance V CAPio MathayNo ratings yet

- SEC. 3 I.: Ramirez V Ca G.R. No. 93833Document7 pagesSEC. 3 I.: Ramirez V Ca G.R. No. 93833maanyag6685No ratings yet

- Case MatrixDocument5 pagesCase MatrixFatima Blanca SolisNo ratings yet

- Dagdag vs. Nepomuceno Et Al.Document5 pagesDagdag vs. Nepomuceno Et Al.CofeelovesIronman JavierNo ratings yet

- Sec 13 Consti DigestDocument18 pagesSec 13 Consti DigestCaleb Josh PacanaNo ratings yet

- Hernandez v. NAPOCORDocument3 pagesHernandez v. NAPOCORMaria AnalynNo ratings yet

- Chiquita Brands, Inc. v. Omelio, G.R. No. 189102Document2 pagesChiquita Brands, Inc. v. Omelio, G.R. No. 189102Rich ReyesNo ratings yet

- Almeda vs. Bathala Marketing Industries, 542 SCRA 470Document3 pagesAlmeda vs. Bathala Marketing Industries, 542 SCRA 470Gem Martle PacsonNo ratings yet

- II. Formalities of AgencyDocument38 pagesII. Formalities of AgencyAndrea RioNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-32312 - Tiro vs. HontanosasDocument3 pagesG.R. No. L-32312 - Tiro vs. Hontanosassean100% (1)

- Philippine National Bank vs. Intermediate Appellate Court: - First DivisionDocument6 pagesPhilippine National Bank vs. Intermediate Appellate Court: - First DivisionDorky DorkyNo ratings yet

- in Re Estate of JohnsonDocument8 pagesin Re Estate of JohnsonaudreyNo ratings yet

- Tayco vs. Heirs of Tayco-FLoresDocument7 pagesTayco vs. Heirs of Tayco-FLoresLuke VerdaderoNo ratings yet

- Caniza Case and Republic V CADocument3 pagesCaniza Case and Republic V CAEmiaj Francinne MendozaNo ratings yet

- 006 Prats-v-CADocument3 pages006 Prats-v-CAdorianNo ratings yet

- Nunez Et Al Vs GSIS Family BankDocument6 pagesNunez Et Al Vs GSIS Family BankColeen Navarro-RasmussenNo ratings yet

- 3rd BATCHDocument14 pages3rd BATCHAnonymous 2UPF2xNo ratings yet

- People v. BarroDocument20 pagesPeople v. Barromceline19No ratings yet

- EMAS - Rule 3 - Sustiguer v. TamayoDocument2 pagesEMAS - Rule 3 - Sustiguer v. TamayoApollo Glenn C. EmasNo ratings yet

- Conflict of Laws Appilicable Laws Laws Governing Contracts (1992)Document11 pagesConflict of Laws Appilicable Laws Laws Governing Contracts (1992)Cecille Therese PedregosaNo ratings yet

- PP V Eduarte (DIGEST)Document1 pagePP V Eduarte (DIGEST)Camella AgatepNo ratings yet

- US V BarriasDocument3 pagesUS V BarriasTheodore BallesterosNo ratings yet

- 6 Naawan Community vs. CA (2003)Document1 page6 Naawan Community vs. CA (2003)BananaNo ratings yet

- Sempio V CADocument2 pagesSempio V CAAidyl PerezNo ratings yet

- Won vs. Wack Wack Golf (104 Phil 466) - DigestDocument1 pageWon vs. Wack Wack Golf (104 Phil 466) - DigestMichelle LimNo ratings yet

- South City Homes Vs BA Finance Corporation - G.R. No. 135462. December 7, 2001Document9 pagesSouth City Homes Vs BA Finance Corporation - G.R. No. 135462. December 7, 2001Ebbe DyNo ratings yet

- I. Shimizu Phils Contractors Vs MagsalinDocument3 pagesI. Shimizu Phils Contractors Vs MagsalinLA RicanorNo ratings yet

- SPOUSES CONSUELO and ARTURO ARANETA, Petitioners, v. THE COURT OF APPEALS, PILIPINAS BANK and DELTA MOTOR CORPORATIONDocument2 pagesSPOUSES CONSUELO and ARTURO ARANETA, Petitioners, v. THE COURT OF APPEALS, PILIPINAS BANK and DELTA MOTOR CORPORATIONjemsNo ratings yet

- Vda. de Agatep vs. LimDocument1 pageVda. de Agatep vs. LimlchieSNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines Vs Erick MontierroDocument3 pagesPeople of The Philippines Vs Erick Montierromelrene jalmanzarNo ratings yet

- #185 - People vs. AbulonDocument3 pages#185 - People vs. AbulonGenerousdeGuzmanNo ratings yet

- OrmacheaTin-Congcovs TrillanaDocument1 pageOrmacheaTin-Congcovs TrillanaTelle Marie100% (3)

- MWSS Vs CADocument2 pagesMWSS Vs CAKarez MartinNo ratings yet

- Royal Crown Internationale VS NLRCDocument1 pageRoyal Crown Internationale VS NLRCKevin CrosbyNo ratings yet

- Alvarez V. Iac G.R. No. L-68053 May 7, 1990 FactsDocument2 pagesAlvarez V. Iac G.R. No. L-68053 May 7, 1990 FactsMichaelNo ratings yet

- Gochan v. Young, 354 SCRA 207 (2001)Document31 pagesGochan v. Young, 354 SCRA 207 (2001)inno KalNo ratings yet

- Necess OrioDocument2 pagesNecess OrioJuanDelaCruzNo ratings yet

- Ramos Vs EscobalDocument2 pagesRamos Vs EscobalCecille Garces-SongcuanNo ratings yet

- Saldana vs. Phil. GuarantyDocument1 pageSaldana vs. Phil. GuarantyKeilah ArguellesNo ratings yet

- CASE No. 51 Agbada vs. Inter-Urban DevelopersDocument2 pagesCASE No. 51 Agbada vs. Inter-Urban DevelopersAl Jay Mejos100% (1)

- Co-Ownership, Partition, Possession: Property Lecture 4 - 2019Document18 pagesCo-Ownership, Partition, Possession: Property Lecture 4 - 2019Cindy-chan DelfinNo ratings yet

- Anaya Vs ParaloanDocument3 pagesAnaya Vs Paraloanms_paupauNo ratings yet

- A.M. No. P-04-1857 - Dagooc v. ErlinaDocument2 pagesA.M. No. P-04-1857 - Dagooc v. ErlinaJoshua John EspirituNo ratings yet

- Celestino Balus vs. Saturnino BalusDocument3 pagesCelestino Balus vs. Saturnino BalusDiosa Mae SarillosaNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila Second Division: Supreme CourtDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila Second Division: Supreme CourtChris InocencioNo ratings yet

- Pacific Rehouse Corporation vs. Ngo PDFDocument17 pagesPacific Rehouse Corporation vs. Ngo PDFElvin BauiNo ratings yet

- Agency - Modes of Extinguishment of Agency - Barba, Daylinda C.Document1 pageAgency - Modes of Extinguishment of Agency - Barba, Daylinda C.gongsilogNo ratings yet

- St. Mary Crusade vs. RielDocument2 pagesSt. Mary Crusade vs. RielPATRICIA MAE GUILLERMONo ratings yet

- Somodio v. CADocument3 pagesSomodio v. CAJohayrah CampongNo ratings yet

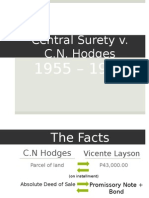

- Central Surety v. CN HodgesDocument12 pagesCentral Surety v. CN Hodgeskrys_elleNo ratings yet

- SALVADOR V. REBELLION, Petitioner, vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, RespondentDocument2 pagesSALVADOR V. REBELLION, Petitioner, vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, RespondentJay-r Mercado ValenciaNo ratings yet

- 227 - Luna vs. IACDocument3 pages227 - Luna vs. IACNec Salise ZabatNo ratings yet

- Valdevieso v. DamalerioDocument5 pagesValdevieso v. DamalerioAsHervea AbanteNo ratings yet

- Severino V SeverinoDocument2 pagesSeverino V SeverinoFrancis MasiglatNo ratings yet

- Panganiban Vs Tara Trading Ship Management, Inc. GR 187032Document4 pagesPanganiban Vs Tara Trading Ship Management, Inc. GR 187032April BetonioNo ratings yet

- UMC v. VelascoDocument4 pagesUMC v. VelascobusinessmanNo ratings yet

- Art. 810 819 CASESDocument5 pagesArt. 810 819 CASESAngelica CrisostomoNo ratings yet

- Succ - Gan vs. YapDocument4 pagesSucc - Gan vs. YapCheCheNo ratings yet

- Escalante vs. People of The Philippines G.R. No. 192727 January 9, 2013Document5 pagesEscalante vs. People of The Philippines G.R. No. 192727 January 9, 2013Adrian HughesNo ratings yet

- Partylist Topic Case DigestDocument9 pagesPartylist Topic Case DigestAdrian HughesNo ratings yet

- Table of Testate & Intestate SuccessionDocument7 pagesTable of Testate & Intestate SuccessionAdrian Hughes100% (2)

- CIR vs. OcierDocument9 pagesCIR vs. OcierAdrian HughesNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument1 pageCase DigestAdrian HughesNo ratings yet

- Cang vs. CADocument17 pagesCang vs. CAAdrian HughesNo ratings yet

- Illegitimate ChildrenDocument57 pagesIllegitimate ChildrenAdrian HughesNo ratings yet

- Civil Code of The Philippines: Conflicts of Law Provisions, Arts. 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18Document4 pagesCivil Code of The Philippines: Conflicts of Law Provisions, Arts. 14, 15, 16, 17, and 18Adrian HughesNo ratings yet

- Castillo vs. CastilloDocument6 pagesCastillo vs. CastilloAdrian HughesNo ratings yet

- Cang vs. CADocument17 pagesCang vs. CAAdrian HughesNo ratings yet

- Sir JohnDocument14 pagesSir JohnMaestro Mertz50% (6)

- Frank Chavez Complaint Against Gloria Macapagal ArroyoDocument23 pagesFrank Chavez Complaint Against Gloria Macapagal ArroyoVERA Files100% (3)

- Recreatinal ActivitiesDocument2 pagesRecreatinal ActivitiesRose Ann GrandeNo ratings yet

- China Friend or FoeDocument289 pagesChina Friend or FoeZaheer Khan50% (2)

- Peoria County Jail Booking Sheet For Sept. 18, 2016Document8 pagesPeoria County Jail Booking Sheet For Sept. 18, 2016Journal Star police documentsNo ratings yet

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogDocument3 pagesGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson LogWenjun50% (2)

- Importance of Foreign Language in International BusinessDocument32 pagesImportance of Foreign Language in International BusinessHarshini AHNo ratings yet

- Police AttitudeDocument9 pagesPolice Attitudegym-boNo ratings yet

- NTLNG in Nglish: How Givesuccessful PresentationsDocument5 pagesNTLNG in Nglish: How Givesuccessful PresentationsTrần Thanh KhiếtNo ratings yet

- Susan Lawrence FileDocument7 pagesSusan Lawrence FilePoliceabuse.comNo ratings yet

- Read The Text and Choose The Correct AnswersDocument2 pagesRead The Text and Choose The Correct AnswersSylvia YeoNo ratings yet

- The History of Tour GuidingDocument5 pagesThe History of Tour GuidingPatriciaNo ratings yet

- Leadership & Mgt.Document21 pagesLeadership & Mgt.Abhijit DeyNo ratings yet

- Eo 376Document3 pagesEo 376Jad ManapatNo ratings yet

- Broadacre CityDocument8 pagesBroadacre CitySuresh Twanabasu A PositiveNo ratings yet

- St. Vincent de Ferrer College of Camarin, IncDocument5 pagesSt. Vincent de Ferrer College of Camarin, IncTricia ForondaNo ratings yet

- Governance and Corruption Constraints in The Middle East - Overcoming The Business Ethics Glass CeilingDocument57 pagesGovernance and Corruption Constraints in The Middle East - Overcoming The Business Ethics Glass CeilingKamal JoshiNo ratings yet

- Ns 53art05 Dyachenko PDFDocument4 pagesNs 53art05 Dyachenko PDFAtif KhanNo ratings yet

- YIJC 2019 GP Prelim P2 - InsertDocument5 pagesYIJC 2019 GP Prelim P2 - InsertTimothy HandokoNo ratings yet

- QualitativeDocument8 pagesQualitativeCmc Corpuz AbrisNo ratings yet

- Marketing Plan For A New ProductDocument14 pagesMarketing Plan For A New ProductAhmer NaveerNo ratings yet

- Art AppreciationDocument4 pagesArt Appreciationmikee jane sabilloNo ratings yet

- Study On Customer Satisfaction For Surya Roshni LTD Under Various Segments in Bangalore CityDocument63 pagesStudy On Customer Satisfaction For Surya Roshni LTD Under Various Segments in Bangalore CityLayana Uthaman100% (1)

- Study Notebook-OstulanoDocument34 pagesStudy Notebook-OstulanoJonathan BulawanNo ratings yet

- TCWD Reviewer From CanvasDocument34 pagesTCWD Reviewer From Canvasjhanelle ibañezNo ratings yet

- Chart and Compass (London Zetetic Society)Document8 pagesChart and Compass (London Zetetic Society)tjmigoto@hotmail.comNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document46 pagesUnit 1navdeepNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Literature On Recruitment and Selection ProcessDocument10 pagesA Systematic Review of Literature On Recruitment and Selection ProcessJAYANT SINGHNo ratings yet

- Economic Value of Forestland: - Market Values - DirectDocument21 pagesEconomic Value of Forestland: - Market Values - DirectAgung Jati PramonoNo ratings yet