Chapter 2 Solutions: Solutions To Questions For Review and Discussion

Chapter 2 Solutions: Solutions To Questions For Review and Discussion

Uploaded by

Albert CruzCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 2 Solutions: Solutions To Questions For Review and Discussion

Chapter 2 Solutions: Solutions To Questions For Review and Discussion

Uploaded by

Albert CruzOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 2 Solutions: Solutions To Questions For Review and Discussion

Chapter 2 Solutions: Solutions To Questions For Review and Discussion

Uploaded by

Albert CruzCopyright:

Available Formats

CHAPTER 2 SOLUTIONS

Solutions to Questions for Review and Discussion

1. The cost objective is defined as any purpose for which costs are accumulated. The cost driver

is the activity necessary to achieve the desired result or objective. These activities require the

use of resources that cost money.

2. The term "cost" has meaning only in a specific set of circumstances and for a particular

purpose. A modifier is needed to convey a set of circumstances and to suggest the purpose

for which the cost will be used. Each modifier dictates the term's proper usage and the costs

relevant for that usage.

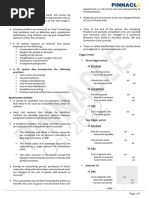

3. Figure 2.1 shows the relationship among activities that use resources to generate products or

services. The boxes represent the physical flow of resources (materials, labor, and overhead

resources) to the production process called activities. Out of these activities comes the

product or service.

Now, resources cost money. The level of resources used is determined by the cost driver.

The costs incurred by the activities are attached to the products and services according to the

cost objective.

Work goes on within the activities. The resources are often called inputs to the production

process. And, the result is the outputs – products or services.

This diagram reflects the basic cost accounting relationships: costs of resources are

eventually attached to outputs of the production process.

4. $100,000 + $12X is a quantitative version of the cost function of a + b (x), where "a" is the

fixed cost term, "b" is the variable cost per unit, and "x" is the volume or activity level. The

fixed costs for a specific time period are $100,000, and the variable cost per unit of output or

activity is $12. Total production costs will be $100,000 plus $12 times "x" amount of output or

activity.

5. Service firms commonly divide expenses between direct client expenses (traceable to specific

revenues) and operating expenses. All costs are essentially period costs since service firms

maintain only nominal supplies inventory.

Merchandising firms hold inventories of the goods that they buy and sell, which are called

merchandise inventory. This is the product cost and, when sold, creates cost of goods sold.

All other expenses in a merchandising firm are operating expenses or period costs.

Manufacturing firms will have many inventory accounts: raw materials inventory for purchased

materials, work in process inventory for products that are still in the production stage, and

finished goods inventory for products ready for sale. When products are sold, a cost of goods

sold account is created. All nonmanufacturing costs are operating expenses or period costs.

6. Cost of goods manufactured is the cost of all products finished and transferred from work in

process inventory to finished goods inventory during the time period. Cost of goods

manufactured is found by taking manufacturing costs, adding beginning and subtracting

ending work in process inventories.

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-1

Cost of goods sold is the cost of all products sold during the time period. The dollars

transferred from finished goods inventory when a sale occurs are cost of goods sold. Cost of

goods sold is found by taking cost of goods manufactured, adding beginning and subtracting

ending finished goods inventories.

Total manufacturing costs is the sum of all resources used in the manufacturing process

during a given time period. Traditionally, this is the total of materials used, direct labor, and all

manufacturing overhead. It represents all costs added to work in process inventory during the

period.

7. A period cost is identified with a time period and not with the production of products and

services. The time period in which the benefit is received is the period in which the cost

should be deducted as an expense. Costs incurred in manufacturing products, however, are

attached to the product outputs and become expenses only when these products are sold.

Generally speaking, a product cost is any cost incurred in the factory, while period costs are

incurred in sales, administration, distribution, and financing activities.

The distinction is important in income determination where the rules of the financial

accounting concept of matching revenues and expenses come into play. Product costs are

inventoried if not sold. Period costs are always expensed. Thus, product costs are expensed

only when revenue is recognized.

8. The three traditional cost elements are direct materials, direct labor, and factory overhead. In

new manufacturing environments with activity-based costing, many other groupings of costs

are used and are discussed in Chapters 4 and 6.

Direct materials and direct labor are traced to the products produced. Materials costs are

easily attached to products; because, in most cases, materials are visible parts of the product.

Direct labor is also fairly easy to trace to products since we know who is working on what

products. All other expenses are factory overhead costs or indirect costs. Rarely does a clear

relationship exist between overhead expenses and products. Some activity measure, a cost

driver such as units or direct labor costs, is used to apportion factory overhead to products.

Chapter 4 will discuss this in detail.

But even in materials and direct labor categories, gray areas exist. Glue and nails in a

furniture factory might be classed as materials or supplies, a factory overhead cost. A quality

inspector's wage might be direct labor in one factory but indirect labor in another factory.

Policies and accounting rules will be written for each factory to define these terms.

9. Total variable costs vary in direct proportion to changes in the activity base. Total fixed costs,

on the other hand, remain constant in total and do not change as activity changes. A

semivariable cost has both a fixed cost component and a variable cost component. A certain

portion remains fixed throughout the relevant activity range, while the other component moves

in direct proportion to any activity change. Combining the two elements gives a cost that

varies in total but not in direct proportion to the change in activity.

On a per unit basis, a variable cost is constant throughout the relevant range. The per unit

amount represents the slope of the total variable cost curve. Fixed costs per unit decrease as

activity increases. This occurs because the total fixed costs are constant and are divided by

an ever increasing number. A semivariable cost will decrease as activity increases, similar to

the fixed cost behavior; but, the decrease is not as pronounced because the variable cost per

unit component remains constant.

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-2

10. Inasmuch as total fixed costs remain at a set amount, the fixed cost per unit changes as the

number of units increases or decreases. Since the cost per unit of product or service

depends on the number of units or activity for a period of time, fixed costs cause unit costs to

change as volume changes.

Certain resources can be purchased only in lumps or large quantities – a machine to make

thousands of units or a manager to supervise high or low production levels. Thus, fixed costs

can represent indivisible resources. We must decide when to acquire more capacity.

Certain costs are fixed with respect to one activity measure (i.e., units produced), but variable

with some other activity measure (i.e., number of employees hired).

Fixed costs are often indirect costs and are difficult to trace to specific products. A cost driver

must be found that links the resource use and outputs.

11. The level of activity is needed. Then, variable cost per unit is converted to total variable costs

using the variable rate and the activity level. And the fixed cost lump is converted into fixed

cost per unit using the activity level.

12.

(a) In the real world, very few costs are constant either in total (fixed costs) or in an amount per

unit of volume or activity (variable costs). In the real world, actual costs are incurred in

specific amounts for specific time periods and for specific amounts of resources. Costs are

related to some activity but not as an exact mathematical form. Also, the relevant range limits

the practical span of the linearity assumption. For variable costs, economies and

diseconomies of scale can cause variable costs per unit to change as activity changes. For

fixed costs, additional costs may be needed at higher activity levels. Many costs have both

fixed and variable characteristics.

(b) These four terms are often used interchangeably. But, some people prefer precise definitions

as follows:

Semivariable cost is a cost that changes in total amount with changes in output or activity but

does not change in direct proportion. Semivariable costs tend to be predominately

variable but with a change in per unit cost as activity changes.

Semifixed cost is a cost that increases in lumps of cost with changes in output or activity.

Semifixed costs are predominately fixed but change in dollar lumps at some point within

the relevant range.

Step cost is a cost that increases by a fixed amount as certain levels of activity are reached.

Step costs may have a few large steps and be fixed over broad ranges of activity or have

many small steps and appear to act like variable costs.

Mixed cost frequently can be divided into a variable rate and a fixed lump.

13. Comments on each statement:

(a) This is true. If a cost is sunk, it is either a past cost which cannot be changed or a future

committed cost that cannot be avoided. In either case, it is irrelevant to a decision since it

cannot change.

(b) This is not true. All past costs are irrelevant, but any cost that does not change among the

choices being considered is also irrelevant to the decision being made.

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-3

(c) This is true. Only present and future costs can be relevant to a decision since these costs can

differ among the choices being considered. But not all present and future costs are relevant.

Those that are the same for the choices being considered are irrelevant to the decision being

made.

(d) This is not true. Only future costs which differ among choices are relevant.

(e) This is true. A cost may be the same for all choices for one decision and, therefore, be

irrelevant; however, that same cost's value may differ among the choices for another decision

and be relevant.

14. A direct cost in one situation may be an indirect cost in another. For example, the salary of a

production departmental supervisor is a direct cost of the plant and that department, but it is

an indirect cost with respect to an array of products produced in that department.

A cost is controllable by a given manager if that manager has the authority to spend or to use

the resource. That cost is noncontrollable to other managers. In a department, a manager

can control spending on supplies, local advertising, telephone, wages of employees, and any

salaries of assistant managers. But a person does not control his or her own salary.

Therefore, the manager's salary is not controllable by that manager but is controllable by that

manager's supervisor. Controllability is determined by who has the authority to spend.

15. (This answer is from the viewpoint of the student taking a managerial accounting course about

the costs of taking the course.)

Direct cost: Tuition (if paid on a per credit basis), textbook, and any supplies purchased

specifically for this course.

Common cost: Room and board costs, entertainment costs if taking more than one course,

and tuition if paid as a lump sum for enrolling regardless of the number of courses or

credits.

Indirect cost: Costs of room and board and travel from home to school, if taking more than

one course.

Controllable cost: Cost of hiring a tutor or buying a study guide.

Variable cost: Tuition if paid on a per credit basis or per course. To measure variability, it is

assumed that credits are the activity base.

Fixed cost: Tuition, if paid as a lump sum, and room and board costs.

Opportunity cost: Wages foregone by electing to go to college. Not studying a foreign

language or astronomy because you elected to take the managerial accounting course.

Avoidable cost: Costs of a textbook, tuition, and course supplies if you do not take the

course. Room and board if you elect not to go to college.

Note: Specific students at specific schools may have different definitions.

16. (The answer is from the viewpoint of a chairperson of a Department of Accounting about the

costs of offering an advanced managerial accounting course.)

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-4

Direct cost: Costs of copying handouts and exams. Possibly salary of instructor if the

instructor is hired to teach this course only. Any rental costs for rooms and audio-visual

equipment.

Common cost: All costs of the college administration including the salaries of the president,

the chairperson, and any maintenance people.

Indirect cost: All common costs above. Departmental secretaries, telephones, and financial

aid office costs. Instructor's salary if that person is teaching other courses, does advising,

conducts research, or is active in professional organizations on behalf of the college.

Controllable cost: Probably very few items, such as number of handouts that the instructor

provides to students during the term.

Variable cost: Costs of any handouts and exams that vary with the number of students in the

course. Instructor's salary if the person is paid on the basis of the number of enrollees.

Fixed cost: Salary of the instructor if the activity base is the number of students taking the

course.

Opportunity cost: Tuition that could be earned if the instructor taught an additional taxation

course. Or costs that could be avoided if the managerial accounting course was canceled

and the instructor taught the taxation course.

Avoidable cost: Instructor's salary, if he or she would not be hired if the course is not taught.

Costs of any handouts if the course is not taught.

Out-of-pocket cost: Costs of any supplies or handouts if the course is taught. Salary of the

instructor that would be hired to teach the course.

Note: Specific answers for this question depend on the administrative structure, the specific

course situation, and the chairperson's responsibilities at your college.

17. Yes, but very likely the change is small. If a product is eliminated, less activity will occur in

many areas. The change may be very small and not easily measurable. If ten products are

eliminated, the impacts may be measurable. Inventory handling, purchasing, insurance, and

bill paying are probably indirect activities that will have decreased volumes, but the impact on

costs may be small or nonexistent.

The property tax on a factory building is an indirect cost to all departments inside the building.

If a department is eliminated, the property tax will not change. On the other hand, any indirect

costs that are incurred by only one department can be eliminated if the department shuts

down (for example, the maintenance and repairs on equipment if the department is closed

and the equipment is sold).

18. Prime costs: G + H

Conversion costs: H + C or H + (A + B)

Direct costs: G + H (Assumes that no factory overhead is direct.)

Indirect costs: A + B or C

Total manufacturing costs: G + H + C or G + H + (A + B)

Costs transferred to finished goods inventory: G + H + C + D - I

Cost of goods sold: G + H + C + D - I + E - J

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-5

19. The criteria for determining a direct cost and a controllable cost differ. Glenda's salary can be

traced directly to the Admissions Department and is therefore a direct cost. However, Glenda

does not have authority to set her own salary, so the salary is a noncontrollable cost to her. If

the purpose of the departmental cost report is to provide accountability over those costs

controlled by Glenda, she is correct in saying her salary should not be in the cost report for

the department she supervises. A basic principle of responsibility accounting is that only

controllable costs should appear on the cost control report. However, if the report is used to

evaluate the department itself as an operating unit, Glenda’s salary is a key part of the

department's financial performance. It must be included in any evaluation of the unit itself.

20. Contribution margin is the portion of revenue that remains after a certain set of costs are

subtracted. Variable contribution margin is calculated using only variable items, and it is used

to determine how much revenue (margin) is left to cover fixed costs and to make a profit. It is

generally used to determine the profitability of a product. The controllable contribution margin

represents sales minus all the costs controllable by the manager of the profit center. It is used

to evaluate a manager's performance. Direct contribution margin represents total segment

revenues minus all costs that can be traced to that segment. It explains how much profit a

segment contributes before common costs are allocated to it.

21. Allocated costs will exist regardless of whether or not we keep the subsidiary. The costs

allocated to the French subsidiary would simply be reallocated to the remaining subsidiaries.

Therefore, profitability of the subsidiary should be determined without using the allocated

costs. If the segment shows a profit ignoring allocated costs, then the company would be

worse off without it. If the subsidiary does not show a profit before allocated costs are

deducted, it is not covering even its direct costs.

Solutions to Exercises

2-1.

(1) Beginning direct materials – 8/1 $ 18,000

Plus direct materials purchased 80,000

Direct materials available $ 98,000

Less ending direct materials – 8/31 (10,000)

Direct materials used $ 88,000

Direct labor 30,000

Factory overhead 120,000

Total manufacturing costs $238,000

Plus beginning work in process – 8/1 12,000

Minus ending work in process – 8/31 -16,000

Cost of goods manufactured $234,000

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-6

(2)

Direct Materials Work in Process

$ 18,000 | $ 12,000 |

80,000 | $ 88,000 88,000 | $234,000

$ 10,000 | 30,000 |

120,000 |

$16,000 |

Direct Labor Finished Goods

$ 30,000 | $ 30,000 $ 45,000 |

234,000 | $241,000

$ 38,000 |

Manufacturing Overhead Cost of Goods Sold

$120,000 | $120,000 $241,000 |

2-2. Cost Behavior Product Direct/

Cost Item Var/Semivar/Fix /Period Indirect

(a) Sales commissions Variable Period Either2

(b) Plant manager's salary Fixed Product Indirect

(c) Lubricating oils Var or Semivar Product Indirect

(d) Brass rods Variable Product Direct

(e) Property taxes: Factory Fixed Product Indirect

Office Fixed Period

(f) Labor – repairs and maintenance Probably Semivar Product Indirect

(Could be Var or Fix)

(g) Supervisor's salary – grinding Fixed Product Indirect

(h) Crude oil Variable Product Direct1

(i) Artists' wages – grocery ads Probably Fixed Period

(j) Depreciation – office furniture Fixed Period

(k) Quality assurance personnel Fixed Product Indirect

(l) Robotics software engineers Fixed Product Indirect

(m)Union auto assembly work wages Fixed & Variable Product Possibly both 3

1

This is a joint cost and could be considered to be indirect for specific products.

2

Commissions expense could be a direct period expense if commissions are paid on

specific products; otherwise, they are an indirect period expense.

3

An interesting case. The guaranteed wage acts like a fixed salary. The hours spent

doing assembly work would be variable and be direct product costs. The hours spent

not doing assembly (or other direct labor) work would be considered overhead and be

indirect product costs.

2-3. Beginning materials inventory $8,000 (2006 ending balance)

Plus materials purchases 30,000

Minus ending materials inventory (15,000) (2008 beginning balance)

Materials used $23,000

Direct labor 20,000

Factory overhead 40,000

Total manufacturing costs $83,000

Plus beginning work in process inventory 24,000 (2006 ending balance)

Minus ending work in process inventory (18,000) (2008 beginning balance)

Cost of goods manufactured $89,000

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-7

2-4.

Department 1: Given: (a) DL + FOH = $200,000

(b) DL + DM used = $300,000

(c) Beginning DM – Ending DM = ($20,000)

DM purchases + (Beginning DM – Ending DM) = DM used = $200,000 – $20,000 = $180,000

Substitute DM used to solve for DL: DL + $180,000 = $300,000; DL = $120,000

Substitute DL in (a) to solve for FOH: $120,000 + FOH = $200,000

Factory overhead = $80,000

Department 2: Given: (a)DL + FOH = 3DM

(b) DM + DL + FOH = $600,000

(c) Indirect product costs = FOH = 0.5 x (DL + FOH)

Since FOH is IPC, DL and FOH must be equal (50 percent each)

Let A represent DL and FOH in (a): A + A = 3DM or 2A = 3DM

Substitute 3DM for (DL + FOH) in (b): DM + 3DM = $600,000

Direct materials = ($600,000 4) = $150,000

Department 3: Given: (a) TMC – CC = DM 1.00 – 0.60 = 0.40

(b) CC = DL + FOH 0.40 = (0.25 x 0.40) + 0.75 x 0.40)

(c) FOH = $600,000

(d) FOH = 0.30 (TMC)

(e) TMC = $600,000 / 0.30

Total manufacturing costs = $2,000,000

2-5.

(1) Cost Element Costs Units Cost Per Unit

Materials HK$200,000 10,000 HK$20.00

Direct labor 50,000 10,000 5.00

Factory overhead 250,000 10,000 25.00

Total manufacturing costs HK$500,000 10,000 HK$50.00

(2) Cost Per Unit Units Total Costs

Cost of goods sold HK$50.00 8,000 HK$400,000

Ending inventory 50.00 2,000 100,000

Total manufacturing costs HK$500,000

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-8

2-6.

(a) Kramer:

High Activity – Low Activity Cost of 2,000 Turkeys Variable Cost

($25,000 – $22,000) = $3,000 = $1.50 per turkey

(8,000 – 6,000) 2,000

Fixed cost: $25,000 – (8,000 x $1.50) = $13,000 or $22,000 – (6,000 x $1.50) =

$13,000

Cost function: a + b (x) = $13,000 + $1.50 (x)

(b) Bradburn:

Total costs – Fixed costs = Variable costs or $600,000 – $240,000 = $360,000

Variable cost per unit: $360,000 120,000 units = $3 per unit

Cost function: Total costs = a + b (x) = FC + VC per unit (x)

TC = $240,000 + $3 (x)

Next year’s cost estimate = $240,000 + $3 (140,000) = $660,000

(c) Slowik:

Cost Function Costs of 50 Contracts Costs of 30 Contracts

Variable costs $3,000 per contract $150,000 $90,000

Fixed costs $30,000 per month 30,000 30,000

Total costs $180,000 $120,000

Average cost $3,600 $4,000

2-7. Joyce's costs: $20,000 + $0.10 (x) Diana’s costs: $2,000 + $0.40 (x)

Indifferent point: $20,000 + $0.10 (x) = $2,000 + $0.40 (x); x = 60,000 boxes

Below 60,000 boxes, Diana is the low cost producer. Above 60,000 boxes, Joyce is the low-

cost producer. At high volumes, Joyce has the advantage because of her low per unit cost

and because her higher fixed costs have less impact. At low volumes, Diana's low fixed costs

are important even though her unit cost is three times Joyce's unit cost.

2-8.

(a) Variable, although some semivariability probably exists.

(b) Variable, based on sales or number of pizzas.

(c) Fixed, assumes that a supervisor's salary is a fixed cost. However, if the supervisor is paid

only on an as-needed basis, then it would be a semifixed (step-fixed) cost.

(d) Variable, probably with the number of pizzas delivered. If some waiting time is assumed, the

wages could be semivariable.

(e) Fixed.

(f) Semifixed, if ovens are operating when the business is open and if power use fluctuates only

due to 24-hour openings and severe peak and slow periods.

(g) Semivariable or mixed. A lease partially based on sales implies that each month a base

amount (fixed portion) plus a sum calculated as a percentage of sales are paid.

(h) Variable, assumes that the fixed cost of the drink machine is excluded.

(i) Fixed.

(j) Semifixed, assumes maintenance costs are always incurred, maybe as an extended warranty

contract (fixed). Actual repairs are probably cost lumps that occur irregularly (maybe step-

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-9

fixed). Some may be related to use.

2-9.

(1) The sunk cost is the $50,000 cost of producing the jeans. It is a past cost, cannot be

changed,

and does not affect the decision to be made.

(2) Choices: Rework & Sell Sell to Mexico Sell as Waste

Revenue $15,000 $6,000 $2,200

Additional expenses:

Rework (8,000)

Freight (750)

$ 7,000 $5,250 $2,200

Select "rework and sell" choice. It gives the highest net cash inflow.

(3) Quantitatively, the "wait" alternative is weak. The annual storage cost is $2,400. These are

out-of-pocket dollars. The waiting period is eight to ten years. Subtracting $19,200 to

$24,000 of storage costs would leave only $6,000 to $10,800 profit, even if her prediction is

accurate. She can get $7,000 today. She would have to wait eight to ten years for a chance

of getting a larger return. The longer into the future we must wait for an event, the more

uncertain the outcome of the event is. Given that this is style merchandise, the predicted

salability is uncertain; the $30,000 is clearly uncertain; and the timing is uncertain.

Students should suggest the time value of money issue. Dollars received today have more

value than dollars eight to ten years into the future. The $7,000 she would get from the

"rework and sell" alternative can be earning returns for the next eight to ten years. Instead, if

she waits, she is paying storage costs every month, with no firm promise of $30,000. And the

other alternatives may also disappear.

2-10.

(a) Mydlowski Co. cost function:

Cost at highest activity – Cost at lowest activity = ($36,000 – $28,000) = $20 per unit

Highest activity – Lowest activity (1,100 – 700)

Total fixed cost = Total cost at highest activity – (Variable cost per hour x Highest activity)

or

Total fixed cost = Total cost at lowest activity – (Variable cost per hour x Lowest activity)

Total fixed cost = $36,000 – ($20 X 1,100) = $14,000

Cost function: a + b (x) = $14,000 + $20 (x)

(b) Coppo Credit Checking Agency cost function: $2,000 + $5 (x)

Budgeted costs (2,100 credit checks): $2,000 + $5 (2,100) $12,500

Actual costs (given) 13,200

Actual spending over budget $700

Coppo Credit Checking Agency’s actual total costs were higher than the adjusted budget

costs by $700, implying that it was unable to perform at its expected level of spending.

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-10

(c) Puidokas Lub Services cost function:

Cost at highest activity – Cost at lowest activity = ($21,000 – $18,000) = $15 per unit

Highest activity – Lowest activity (1,200 – 1000)

Total fixed cost = Total cost at highest activity – (Variable cost per hour x Highest activity)

or

Total fixed cost = Total cost at lowest activity – (Variable cost per hour x Lowest activity)

Total fixed cost = $18,000 – ($15 x 1,000) = $3,000

Cost function: a + b (x) = $3,000 + $15 (x)

2-11.

(1) Using the high-low method:

Cost at highest activity – Cost at lowest activity = ($20,000 – $15,000) = $2.50 variable cost per MH

Highest activity – Lowest activity (6,000 – 4,000)

Total fixed cost = Total cost at highest activity – (Variable cost per hour x Highest activity)

or

Total fixed cost = Total cost at lowest activity – (Variable cost per hour x Lowest activity)

Total fixed cost = $20,000 – ($2.50 X 6,000) = $5,000

Cost function: a + b (x) = $5,000 + $2.50 (x)

(2) October cost estimate using the cost function in part (1):

$5,000 + $2.50 (4,300 hours) = $15,750

2-12.

(1) Total costs = a + b (x)

$500,000 = $300,000 + b (200,000)

b = $1 variable cost per gallon

Marginal cost would equal $1 per gallon, which is the cost of producing one additional gallon

of

“Good Stuff.”

(2) Average cost per gallon for 180,000 gallons: Total cost Gallons produced

$300,000 + ($1 * 180,000) = $480,000

$480,000 180,000 = $2.67 per gallon (rounded)

(3) Total costs for 220,000 gallons using the cost function:

$300,000 + $1 (220,000) = $520,000

$520,000 220,000 = $2.36 per gallon (rounded)

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-11

2-13.

(1) Variable costs: Change in cost Change in hours

October and November: £5,000 1,000 = £5 per hour

November and December: £10,000 2,000 = £5 per hour

Next, subtract the variable costs at each level from total costs to see if the fixed portion is

constant:

October November December

Total costs £17,000 £22,000 £12,000

Variable cost:

£5 per hour x 3,000 hours 15,000

x 4,000 hours 20,000

x 2,000 hours 10,000

Fixed cost per month £ 2,000 £ 2,000 £ 2,000

The cost function is: £2,000 + £5 per unit. As can be shown, this cost function explains

exactly the total costs for the three months.

(2) Yes, one cost function works for all three month. See the calculations for Part (1).

(3) New fixed costs: £2,000 + £1,500 = £3,500 per month

New variable costs: £5 + (£5 * 0.05) = £5.25 per hour

Total budgeted cost for 3,500 hours: (£3,500 * 12) + (£5.25 * (3,500 * 12)) = £262,500

2-14.

To: Cynthia Golden

From: Fellow student

Certain costs are very important to your decision of whether or not to return to school. One of the

most important is your opportunity cost. This is the salary from your current job that you will

forego, $25,000.

Unless you change your living patterns, your living costs of $16,000 per year are irrelevant to the

decision since they are the same under either alternative. However, since the $16,000 is a future

cost, you may be able to change your living costs. No other costs in the data you have provided

are irrelevant or sunk. The tuition and books costs of $9,000 and the salary foregone are relevant

costs.

It is important to note that the most important missing piece of information is your expected

earnings after you complete your degree. As a personal decision, the financial facts may not be

the most critical. However, as a financial decision, you will need to measure the increased

earnings resulting from the degree to decide whether going back to school is a wise economic

decision.

2-15.

A. Materials used $42,000

Direct labor 33,000

Factory overhead 51,000

Total manufacturing costs $126,000

Plus beginning work-in-process 21,000

Minus ending work-in-process (23,500)

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-12

Cost of goods manufactured $123,500

B. Materials purchased $25,000

Plus beginning materials inventory 24,000

Minus decrease in materials inventory (18,000)

Materials used $31,000

Direct labor 50,000

Factory overhead 60,000

Total manufacturing costs $141,000

Minus cost of goods manufactured (129,000)

Increase in work-in-process inventory $12,000

Plus beginning work-in-process inventory 16,000

Ending work-in-process inventory $28,000

C. Cost of goods sold $186,000

Plus ending finished goods inventory 21,000

Minus beginning finished goods inventory (30,000)

Cost of goods manufactured $177,000

Plus ending work-in-process inventory 33,000

Minus beginning in work-in-process inventory (21,000)

Total manufacturing costs $189,000

Notice that the pluses and minuses are reversed as we move from COGS to TMC in this part.

2-16. Unknowns are in bold: Kumamoto Kawasaki Kanazawa

Company Company Company

Sales ¥108,000 ¥90,000 ¥92,000

Cost of goods sold:

Direct materials ¥15,000 ¥19,000 ¥22,000

Direct labor 25,000 20,000 15,000

Factory overhead 60,000 25,000 21,000

Total manufacturing costs ¥100,000 ¥64,000 ¥58,000

Plus work in process – Beginning 4,000 9,000 9,000

Minus work in process – Ending (12,000) (4,000 (6,000)

Cost of goods manufactured ¥92,000 ¥69,000 ¥61,000

Plus finished goods – Beginning 6,000 19,000 8,000

Minus finished goods – Ending (21,000) (22,000) (1,000)

Cost of goods sold ¥77,000 ¥66,000 ¥68,000

Gross margin ¥31,000 ¥24,000 ¥24,000

Operating expenses (25,000) (18,000) (13,000)

Net income ¥6,000 (¥6,000) ¥11,000

2-17.

(1) Product Lines

Green Pink Purple

Revenue $900,000 $600,000 $1,500,000

Cost of sales (490,000) (390,000) (1,040,000)

Variable contribution margin $410,000 $210,000 $460,000

Traceable fixed costs (250,000) (200,000) (350,000)

Direct contribution margin $160,000 $10,000 $110,000

Variable contribution margin ratio 45.6% 35.0% 30.7%

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-13

(2) Product Line Green is the best alternative. Profitability of a product line should be determined

without common costs being included since these costs will be incurred regardless of the

operations of the three product lines. Both the direct contribution margin and the variable

contribution margin ratio give the same answer.

(3) Allocation based on sales dollars: Product Lines

Green Pink Purple

Contribution margin $160,000 $10,000 $110,000

Common costs: (900 3,000) x $300,000 (90,000)

(600 3,000) x $300,000 (60,000)

(1,500 3,000) x $300,000 (150,000)

Net profits $70,000 ($50,000) ($40,000)

No. Product Line Green would still be the most attractive.

Common costs allocated equally: Product Lines

Green Pink Purple

Contribution margin $160,000 $ 10,000 $110,000

Common costs: 1/3 x $300,000 (100,000)

1/3 x $300,000 (100,000)

1/3 x $300,000 (100,000)

Net profits $60,000 ($90,000) $10,000

No. But the shifts for Product Lines Pink and Purple are dramatic. Again, Product Line Green

would still be the most "profitable." The changes in profitability in all the above scenarios

should make one aware of the dramatic effects that common cost allocation have on each

product line.

Note: The method of allocating common costs to the three products has no impact on the

operations, the sales levels, or the level of common costs themselves. While the

resources provided by the common cost expenditures must have benefited the

company and the three products, the analysis of each product is not helped by the

allocation of common costs to products (however it is done).

2-18.

Direct Materials Work in Process

$128,000 | $385,000 (2) $ 82,000 | $845,000 (9)

(1) 346,000 | (2) 385,000 |

$ 89,000 | (4) 155,000 |

(8A) 410,000 |

Direct Labor Cost $187,000 |

(4) $155,000 | $155,000 (4)

Factory Overhead Expenses Finished Goods Inventory

(3) $ 93,000 | $410,000 (8A) $172,000 | $860,000 (12)

(5) 22,000 | (9) 845,000 |

(6) 186,000 | $157,000 |

(7) 26,000 |

(8) 83,000 |

Supplies Inventory Cost of Goods Sold

$ 65,000 | $ 93,000 (3) (12) $860,000 |

(1) 98,000 |

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-14

$ 70,000 |

Accumulated Depreciation Sales

| $56,000 | $1,262,000 (10)

| 22,000 (5)

| $78,000

Accounts Payable Accounts Receivable

(13) $424,000 | $49,000 $122,000 | $1,195,000 (11)

| 346,000 (1) (10) 1,262,000 |

| 98,000 (1) $189,000 |

|$69,000

Cash

$ 36,000 | $ 98,000 (4) Note: Transaction 8A above transfers

(11) 1,195,000 | 186,000 (6) overhead costs to work in process.

| 26,000 (7)

| 83,000 (8)

| 424,000 (13)

$414,000 |

2-19. Total Dollars Per Test Ratio

Sales ($15 x 15,000) $225,000 $15 100.0%

Minus variable costs:

Variable lab costs ($8 x 15,000) $120,000 $8 53.3

Other variable costs ($3 x 15,000) 45,000 3 20.0

Total variable costs $165,000 $11 73.3%

Variable contribution margin $60,000 $4 26.7%

Minus fixed costs:

Fixed lab costs $25,000

Fixed administrative costs 15,000

Total fixed costs $40,000

Net income $20,000

2-20. (a) Factory overhead, factory burden, or manufacturing overhead

(b) Fixed cost

(c) Relevant range

(d) Period cost

(e) Committed cost, sunk cost

(f) Avoidable cost

(g) Opportunity cost

(h) Controllable cost

(i) Common cost, joint cost, or indirect cost

(j) Cost per unit or unit cost, average product cost, or full cost

(k) Marginal cost or incremental cost

(l) Noncontrollable direct cost

2-21.

Case 1: ($250,000 – $240,000) = $10,000 = $0.10 per dozen variable cost per unit

(500,000 – 400,000) 100,000

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-15

$250,000 – ($0.10 X 500,000) = $200,000 fixed cost

Cost function: $0.10 (x) + $200,000

Case 2: $20,000 – $10,000 = $10,000 / 5,000 = $2 per plant potted variable cost

$2 x 6,000 = $12,000 variable plus $10,000 fixed = $22,000 estimated total cost

Case 3: Variable costs: $90,000 / $2,000,000 = 0.045 (S)

Cost function: 0.045 (S) + $80,000

2-22.

(1) Costs controlled by Marie Heltzel:

Equipment maintenance charges – Frankfurt office €2,600

Supplies used – Frankfurt office 1,400

Labor cost – Frankfurt office 14,600

Total controllable costs €18,600

(2) Direct costs of the Frankfurt Branch:

Equipment maintenance charges – Frankfurt office €2,600

Supplies used – Frankfurt office 1,400

Salary – Marie Heltzel 2,500

Labor cost – Frankfurt office 14,600

Equipment depreciation – Frankfurt office 2,300

Total direct costs €23,400

(3) Costs to be allocated in part to the Frankfurt office and suggested cost drivers are:

Home office superintendent's salary €3,000 (effort study, estimate of time spent)

Home office heat and light 2,200 (square footage occupied)

Home office maintenance and repairs 1,700 (investment in equipment, past actual use or

budgeted use of maintenance and repair time)

Home office depreciation 1,000 (square footage occupied)

Total costs to be allocated €7,900

2-23.

(1) Controllable contribution margin = Total sales – Direct controllable costs (Fixed & Variable)

= $480,000 – ($100,000 + $55,000 + $185,000)

= $140,000

(2) Segment or direct contribution margin = Total sales – Direct controllable costs (Fixed &

Variable) – Direct noncontrollable fixed expenses

= $480,000 – ($100,000 + $55,000 + $185,000) – $85,000

= $55,000

2-24. The regional manager may be sensing a pattern of actions by the manager of Store 9 to

temporarily improve that store's profits. Decreasing training costs reduces expenses in the

short run but will hurt profitability in the long run through higher turnover, less efficient

performance, and poorer customer service. Eliminating community involvement may again be

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-16

a temporary cost savings with long-term negative community goodwill. The poorer

performance in Store 6 may reflect the new manager's need to incur operating expenses

(training, maintenance, advertising, etc.) to recover from the deteriorating conditions left by

the manager now at Store 9. The timing of advertising spending also leads to the impression

of the manager's focus on showing strong short-term results with little concern for next year.

On the other hand, every action taken may have come as a result of careful analysis by the

Store 9 manager. A cost-benefit analysis may show shifting priorities on spending may be

best for the total long-term operation of Store 9. And perhaps the new manager of Store 6

could not maintain the strong pace set by the then-Store 6 manager.

The regional manager needs to investigate the personnel morale and quality at Store 9,

examine the reasons for Store 6's profit decline, and analyze other decisions that may focus on

whether the Store 9's manager is too short-sighted and too obsessed with "looking good" at all

costs.

2-25.

(1) Sales $2,000,000

Minus cost of sales (600,000)

Minus variable selling expenses (300,000)

Variable contribution margin $1,100,000

Minus direct controllable fixed marketing expenses (100,000)

Controllable contribution margin $1,000,000

Minus direct noncontrollable fixed marketing expenses (500,000)

Direct noncontrollable contribution margin $ 500,000

Red Pop contributed $500,000 to corporate profits. Allocated costs should be ignored in

determining a segment's performance since they are incurred regardless of whether the

segment operates.

(2) The manager is evaluated on all the costs controlled by that manager. Therefore, the

controllable contribution margin of $1,100,000 should be used to evaluate the manager.

Solutions to Problems

2-26. Cost patterns:

A 1. a + b (x) where...

G 2. Straight-line depreciation...

K 3. Shift supervision salaries...

B 4. Utility costs...

H 5. Sales commissions paid...

L 6. Workers' wages plus overtime...

C 7. Water and waste water costs...

F 8. Payroll taxes that are based...

J 9. Mixed cost within a relevant range.

I 10. Cost of hourly messenger service...

D 11. Wage costs as more hourly telephone callers...

E 12. Materials costs where cost per pound decreases...

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-17

2-27. Rizwan Corporation

Income Statement For the Year Ended December 31

Sales $850,000

Cost of goods sold:

Materials

Beginning raw materials inventory $ 45,000

Plus purchases of raw materials 140,000

Materials available for use $185,000

Less ending raw materials inventory (40,000)

Raw materials used $145,000

Direct labor 225,000

Factory overhead:

Indirect labor $40,000

Factory rent 84,000

Depreciation – machinery 35,000

Insurance – factory 18,000

Repairs & maintenance 12,000

Miscellaneous – factory 26,000

Total factory overhead 215,000

Total manufacturing costs $585,000

Plus beginning work in process inventory 30,000

Less ending work in process inventory (35,000)

Cost of goods manufactured $580,000

Plus beginning finished goods inventory 105,000

Less ending finished goods inventory (110,000)

Cost of goods sold $575,000

Gross margin $275,000

Operating expenses:

Salespersons' salaries $72,000

Administrative salaries 50,000

Miscellaneous – office 40,000

Total operating expenses 162,000

Operating income $113,000

2-28. Unknowns are in bold as follows:

2003 2004 2005

Sales $101,000 $118,700 $125,000

Cost of goods sold:

Direct materials inventory 1/1 $ 8,000 $ 6,000 $ 9,000

+ Direct materials purchases 15,000 20,000 30,000

Direct materials available $23,000 $26,000 $39,000

– Direct materials inventory 12/31 - 6,000 - 9,000 - 12,300

Direct materials used $17,000 $17,000 $26,700

Direct labor 20,000 23,500 40,200

Factory overhead 16,000 21,300 24,000

Total manufacturing costs $53,000 $61,800 $90,900

+ Work in process inventory 1/1 12,000 18,000 16,300

– Work in process inventory 12/31 - 18,000 - 16,300 - 22,300

Cost of goods manufactured $47,000 $63,500 $84,900

+ Finished goods inventory 1/1 15,000 21,000 18,300

Goods available for sale $62,000 $84,500 $103,200

– Finished goods inventory 12/31 - 21,000 - 18,300 - 20,000

Cost of goods sold $41,000 $66,200 $78,200

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-18

Gross profit $60,000 $52,500 $46,800

2-29.

(1) Meters serviced: 500 Meters 800 Meters

Costs Per Unit Costs Per Unit

Variable costs:

Labor costs $15,000 $30.00 $24,000 $30.00

Replacement parts 10,000 20.00 16,000 20.00

Other variable refurbishing expenses 6,000 12.00 9,600 12.00

Total variable costs $31,000 $62.00 $49,600 $62.00

Fixed refurbishing expenses 20,000 40.00 20,000 $25.00

Total refurbishing expenses $51,000 $102.00 $69,600 $87.00

Cost function:

Refurbishing cost per unit = Variable cost per unit (x) + Fixed costs

= $62.00 (x) + $20,000

(2) General and administrative expenses appear to be a mixed cost. To find the variable and

fixed components, first determine the differences in the activity and the cost between the two

levels. The activity difference is 300 meters (800 – 500). The cost difference is $6,000

($15,000 – 21,000). By dividing the $6,000 by the 300 meters, the variable cost per unit is

found – $20 per meter. The fixed cost portion is found by subtracting the variable cost portion

at any level. The remainder is the fixed portion. The fixed portion must be $21,000 minus

$16,000 ($20 x 800) or $5,000. The 500 meter level could also have been used: $15,000 –

(500 meters x $20 per meter) or $5,000, again.

(3) Meters serviced: 500 Meters 800 Meters

Costs Per Unit Costs Per Unit

Total refurbishing expenses $51,000 $102.00 $69,600 $87.00

General and administrative expenses:

Variable portion $10,000 $20.00 $16,000 $20.00

Fixed portion 5,000 10.00 5,000 6.25

Total $15,000 $30.00 $21,000 $26.25

Total costs $66,000 $132.00 $90,600 $113.25

2-29.

(1) Pie costs: 200,000 Pies Per Year

Costs Cost Per Pie

Variable costs:

Direct materials $105,000 $ .525

Direct labor 91,000 .455

Supplies used 36,000 .180

Total variable costs $232,000 $1.160

Direct fixed costs:

Supervision $123,000 $ .615

Depreciation – pie department 32,000 .160

Telephone expenses 8,000 .040

Other pie department expenses 25,000 .125

Total direct fixed costs $188,000 $0.940

Allocated fixed costs:

Utilities, insurance, and taxes $ 52,000 $ .260

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-19

Rent 48,000 .240

Total allocated fixed costs $100,000 $ .500

Total fixed costs $288,000 $1.440

Total costs $520,000 $2.600

(2) If a pie is sold for $2.90:

Per Pie Ratio Total

(a) Selling price $2.90 100.0% $580,000

Variable costs (1.16) (40.0%) (232,000)

Variable contribution margin $1.74 60.0% $348,000

(b) Direct fixed costs (188,000)

Direct contribution margin $160,000

(c) Costs allocated to pies (100,000)

Gross margin (Revenue minus all product costs) $60,000

(3) (Volume x Variable costs per pie) + Total fixed costs = Total pie costs

(150,000 x $1.16) + $288,000 = $462,000

Price per pie = $3.08

2-31. First, find the cost function:

Variable costs = $7,500 5,000 = $1.50 per resume

Fixed costs = $2,000

($1.50 per resume x resumes prepared) + $2,000 = Total cost

Second, prepare a new budget using the cost function and 4,600 resumes:

Original Revised

Budget Budget Actual Fav/(Unfav)

Number of resumes prepared 5,000 4,600 4,600

Variable costs $7,500 $6,900 $7,000 ($100)

Fixed costs 2,000 2,000 2,100 (100)

Total costs $9,500 $8,900 $9,100 ($200)

(a) No, April spent $200 more than it should have in January.

(b) Yes, fixed is fixed is fixed, regardless of volume, as long as it is within April's relevant

range. Barrett spend $100 more than it should have.

(c) Yes, at $1.50 per resume, April should have spent $6,900 on 4,600 resumes. At $7,000,

April overspent by $100 on variable expenses.

(d) No, April should have spent no more than $8,900 in January, given 4,600 resumes processed.

2-32.

(1) Materials: $50,000 25,000 suits = $2 per suit

Direct labor: 2,000 hours x $10 per hour = $20,000

$20,000 2,500 suits = $0.80 per suit

Factory overhead:$2 per suit + $40,000

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-20

Cost function: ($4.80 x Suits produced) + $40,000

($4.80 x 25,000) + $40,000 = $160,000

$160,000 25,000 = $6.40 per suit

(2) Cost of goods sold = $6.40 per suit x 22,000 suits = $140,800

(3) Product costs: $140,800

Period costs: ($1 per suit x 22,000 suits) + $50,000 = $72,000

2-33.

(1) Costs per barrel: Variable Cost Prime Cost

Direct materials $6.25 $6.25

Direct labor 2.00 2.00

Various supplies 1.80

Costs per barrel $10.05 $8.25

(2) Conversion costs per barrel: For 50,000 Barrels

Costs Per Barrel

Direct labor $ 100,000 $2.00

Various supplies 90,000 1.80

Direct other costs 96,000 1.92

Allocated factory overhead 75,000 1.50

($250,000 x 30 %)

Total conversion costs $361,000 $7.22

(3) Controllable costs:

Direct materials (50,000 x $6.25) $312,500

Direct labor (50,000 x $2.00) 100,000

Various supplies (50,000 x $1.80) 90,000

Controllable direct other costs:

Supervision ($85,000 – $48,000) 37,000

Equipment and operating costs 6,000

Repairs and maintenance of equipment 5,000

Total controllable costs $550,500

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-21

4) Total cost per barrel:

40,000 Barrels 50,000 Barrels

Costs Per Barrel Costs Per Barrel

Variable costs:

Direct materials $250,000 $6.25 $312,500 $6.25

Direct labor 80,000 2.00 100,000 2.00

Various supplies 72,000 1.80 90,000 1.80

Fixed costs:

Direct other costs 96,000 2.40 96,000 1.92

Allocated factory o/h 75,000 1.875 75,000 1.50

Total costs $573,000 $14.325 $673,500 $13.47

2-34.

(1) Variable cost per unit = $20,000 20,000 units = $1 per prescription

Cost function: Fixed costs + Variable cost per prescription

($60,000 + $60,000) + $1 per prescription

$120,000 + $1 per prescription

(2) Cost per prescription: Budget Actual

Pharmacists' salaries $ 60,000 $ 64,000

Variable overhead costs 20,000 21,500

Fixed overhead costs 60,000 59,000

Total expenses $140,000 $144,500

Divided by prescriptions filled 20,000 22,000

Cost of filling a prescription: $7.00 $6.568

(3) $120,000 + ($1 x 22,000) = $142,000

(4) Revised budget: Adjusted Budget Actual Fav/(Unfav)

Number of prescriptions filled 22,000 22,000

Pharmacists' salaries $ 60,000 $ 64,000 ($4,000)

Variable overhead costs 22,000 21,500 500

Fixed overhead costs 60,000 59,000 1,000

Total expenses $142,000 $144,500 ($2,500)

Pike's big cost problem is the pharmacists' salaries. Because volume of prescriptions

exceeded budget, perhaps she paid a bonus for working more than expected. Perhaps

salary raises occurred which were not budgeted. Perhaps newly hired pharmacists were

paid more than expected. The other expenses were under budget.

2-35.

(1) Budgeted cost per rivet: Monthly Number of Cost

Budget Rivets Per Rivet

Variable costs:

Prime costs M$80,000 200,000 M$0.40

Utilities for the factory 20,000 200,000 0.10

Total variable costs M$100,000 M$0.50

Fixed costs:

Depreciation of machinery and building M$ 30,000 200,000 M$0.15

Supervision salaries and benefits 60,000 200,000 0.30

Total fixed costs M$ 90,000 M$0.45

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-22

Total budgeted cost of rivets M$190,000 M$0.95

Cost function: M$0.50 (rivets) + M$90,000

(2) Actual cost per rivet: January February

Variable costs:

Prime costs M$75,000 M$82,000

Utilities for the factory 22,000 23,000

Total variable costs M$97,000 M$105,000

Fixed costs:

Depreciation of machinery and building M$30,000 M$30,000

Supervision salaries and benefits 60,500 62,000

Total fixed costs M$90,500 M$92,000

Total budgeted cost of rivets M$187,500 M$197,000

Total rivets produced 180,000 210,000

Total actual cost per rivet M$1.0417 M$0.9381

(3) Comparison of actual to budget:

January February

Budget Actual Fav/(Unf) Budget Actual Fav/(Unf)

Rivets produced 180,000 180,000 210,000 210,000

Prime costs M$72,000 M$75,000 (M$3,000) M$84,000 M$82,000 M$2,000

Utilities 18,000 22,000 (4,000) 21,000 23,000 (2,000)

Depreciation 30,000 30,000 0 30,000 30,000 0

Supervision 60,000 60,500 (500) 60,000 62,000 (2,000)

Total costs M$180,000 M$187,500 (M$7,500) M$195,000 M$197,000 (M$2,000)

Expense control problems existed in both months. No expense was underbudget. Variable

costs caused the largest share of overbudget spending. In January, utilities costs were the

largest problem, perhaps a seasonal heating problem. In February, materials and labor

(cannot tell which is the major cause) showed the biggest variance. Depreciation expense,

which is noncash, is as budgeted. Supervision, supposedly fixed however, is overbudget in

both months. These fixed costs may behave a little like semivariable costs, rising a little as

volume increases. Some closer examination of costs may be helpful in better controlling and

budgeting the expenses.

2-36.

(1) The parties involved appear to be:

The Director of the BBER who contracted with the FPO: This person should have

understood the scope and the intent of the contract when it was negotiated.

The FPO contract person: This person should also have had a clear understanding of the

costs to be incurred to support the contracted work.

The university computer center: Their charges are an important part of the contract and

are set based on many demands made on the computer center.

The taxpayers of the state: They should get a reasonable return on the spending.

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-23

Faculty and graduate students working on the contract: Access to powerful software

models can generate a variety of personal benefits, including research publications,

consulting fees, employment opportunities, and improved reputations.

Students and faculty: They get ancillary use of the equipment at low or no cost.

Note: Students can identify others. Try to focus on major participants.

(2) Issues:

1. Copy machine: The questions related to this issue are: Is other adequate copy

equipment available? What was the intent of the contract? What are incremental costs of

additional use? Can the costs of copying can be allocated or traced in some way?

2. Computer time charges: This area is notorious for abuse within university computer

centers. "Funny money" is often given to faculty to perform research work at no cash cost

or at an extremely low rate relative to externally funded work. The fact that other outsiders

are charged this rate may cause many to argue that it is fair and reasonable, just as other

prices are set without much consideration of cost. This is not, however, a competitive

market. And the rates are almost universally based on some cost allocation process.

Often, these cost accountants should be ashamed of their cost accounting!

3. Personnel time costs: Many will argue that the FPO should have known that a high-

priced faculty person would not be doing the analysis quarter after quarter. Perhaps

naivety at the FPO may be the cause. This allows discussions to turn to the "a sucker is

born every minute" argument.

4. Use of modeling software: This is very troublesome – double dipping, faculty

consulting time, and whose is what. If the FPO contracted for exclusive use of the model,

all other uses are illegitimate. Many gray areas exist here. It is unlikely that the faculty

use for outside consulting work is within reasonable use guidelines.

Some persons will argue that if it's in the contract, it's okay. Yet the pattern of costing in just

this small set of facts raises relevant costing issues. Are average costs applicable to specific

users? Does the incremental need for more capacity (perhaps the copy machine) justify

charging that user for all costs of acquiring more capacity? Should the next student admitted

to the university have to pay for costs of the next mathematics professor hired because some

breakpoint has been reached?

All four costing issues raise serious questions. It is important that students understand the

issues, regardless of how they resolve the issues for themselves. Some students will argue

that the pattern of issues indicates that an ethical problem exists. But this set is only a small

sampling of many cost allocation, identification, and linkages problems that arise routinely.

2-37. Sales $100,000 100%

Less variable costs:

Spinach & direct labor $35,000 35%

Processing overhead 6,000 6

Selling expenses 4,000 4

General expenses 2,000 2

Total variable costs $47,000 47%

Variable contribution margin $53,000 53%

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-24

Cost function: 47% (Sales dollars) + ($15,000 + $10,000 + $15,000)

47% (Sales dollars) + $40,000

2-38. Determine the variable and fixed portion of each cost to create a cost function:

Change in cost Change in requests = Variable cost per request

Typists’ wages: ($1,600 – $1,200) (400 – 300) = $4 per request

Rent, supp & util: ($1,600 – $1,500) (400 – 300) = $1 per request

Total costs: ($3,200 – $2,700) (400 – 300) = $5 per request

$5 per request x 300 requests = $1,500

$2,700 – $1,500 = $1,200 fixed cost *

Cost function: $5 per request + $1,200

*

If we use 400 papers instead of 300, the result will still be the same.

Budget for 320 requests:

Variable Costs Fixed Costs Total Costs

Typists' wages$1,280 $1,280

Rent, etc. 320 $1,200 1,520

Total costs $1,600 $1,200 $2,800

2-39.

Case 1: Relevant costs of living in an apartment versus a dorm room:

Dorm Costs Apartment Costs

Rent (x 9 months) $3,600

Rent (x 12 months) $7,200

Gas for commuting 250

Extra telephone calls 200

Food costs (x 9 months) 900

Irrelevant costs: Depreciation on your car (equal under both alternatives) and CDs (cost feeds

your addiction under both alternatives).

Note: The alternative of subletting your apartment for the summer is excluded because of no

information about it given in the problem – a good discussion point.

Case 2: Relevant costs regarding trading cars:

Keep the Nova Trade for the Mustang

Trade-in value of the Nova $500

Car operating costs $1,500 1,250

Incremental cost of insurance 600

Tires and transmission costs 900

Irrelevant costs: Book value of the Nova, garage rent, and parking tickets are the same under

both alternatives.

2-40.

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-25

(1) Relevant costs for each alternative:

Note: The cost of microfilming is a relevant cost if the choices are:

1. Status quo

2. Rent

3. Produce new product

The cost of microfilming is irrelevant if only the choices renting and producing the new

product are considered. The status quo is always an option.

Option 1: Continue to use the space as storage – status quo.

Option 2:

One-Time Costs Annual Rev & Costs

Microfilming ($20,000) ($3,000)

Rent from space 25,000

Net profits ($20,000) $22,000

Option 3:

One-Time Costs Annual Rev & Costs

Microfilming ($20,000) ($3,000)

Incremental sales 268,000

Direct materials costs (50,000)

Direct labor costs (32,000)

Supervision and other costs (50,000)

Net profits ($20,000) $133,000

This assumes that the allocated costs will not change whether Option 1, 2, or 3 is selected.

(2) Option 1: No change in profits.

Option 2: First year, $2,000 profit; $22,000 profit each year thereafter.

Option 3: First year, $113,000 profit; $133,000 profit each year thereafter.

(3) The superintendent should ask whether any of the allocated costs would change depending

on the option chosen. If so, these costs would become relevant in the decision making. Are

there any costs associated with using the microfilm records? Are the new product costs and

revenue estimates credible?

2-41.

(1) An answer to question 1 is presented below with missing data omitted and assumes no cost

allocations.

Technical General Children

Budget Actual Budget Actual Budget Actual

Direct costs:

Salaries ? $ 78,000 ? $52,000 ? $43,000

Books and periodicals ? 47,700 ? 16,300 ? 11,500

Supplies ? 2,900 ? 2,800 ? 4,600

Total direct costs $120,000 $128,600 $70,000 $71,100 $50,000 $59,100

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-26

2. Fundamentally, the board is interested in providing the best library services to its constituency

as possible, given limited funding. Funds should be allocated to areas of greatest need or

benefit. Measuring usage, matching costs and benefits, setting priorities, meeting goals and

targets, and evaluating operations are among the uses of cost analysis to the board.

Where possible, identifying links between costs (particularly people costs and book costs) and

activities that drive the costs is important, such as which services customers are using,

requesting, or waiting to receive. In a service and nonprofit organization such as this library,

care must be taken by the board to provide the most services possible to the intended various

audiences. Working with school systems in the area, with senior citizen groups, and with

clubs and other groups will undoubtedly bring more demands than this library's resources can

provide. Choices must be based on the goals of the organization, actual usage, and program

commitments.

(3) Costs can be related to use of the services. The problem is that different measures of usage

could cause resources to be reallocated in different ways. Probably no one measure will give

a fair appraisal. But activity and cost should be related. If technical services, which is an

expensive area, are used very lightly, the large staff might better be used in developing

children's programs.

Measures could include:

For performance and budget, comparisons of:

Books checked out

Space occupied

Number of customer inquiries answered

Employees in each area

Total budgeted dollars in each area

Volume of book titles in each area

Surveys of customers and community residents:

Level of satisfaction

Additional services

For control purposes:

Actual versus budget each month and year to date

Cost of performing certain services such as order processing

General administration as a percentage of the total budget

For political and tax support purposes:

Percentage of the community using services

Other community or public services offered through the library

Cost per citizen to support library services

No one measure will give the board the exact answer of where, how much, or even which

budget items should be expanded or contracted.

(4) It is difficult to determine which departments were responsible for what portion of the

administrative overhead. However, if it can be determined that some activity drives the

overhead costs, then it would be important to allocate the costs to the departments based on

each department's level of such activity. This implies that, with less activity, overhead costs

could be reduced.

No good purpose exists to allocate the general library operating costs to the three operating

units. If the instructor insists on allocating the two library-wide costs, the occupancy and

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-27

utilities can be allocated on a percentage of space occupied. Administration could be

allocated using employees, space occupied, or total budgeted dollars. If allocations are done,

the instructor should point out how arbitrary the allocations are and that for control purposes

these allocated costs contribute little.

Solutions to Cases

CASE 2A – Walt's Bus Routes

(1) (in thousands) Passenger Total

Freight Route 1 Route 2 Route 3 Total

Operations

Revenue $3,500 $900 $450 $150 $1,500 $5,000

Minus variable costs 2,000 670 400 130 1,200 3,200

Variable contrib margin $1,500 $230 $50 $20 $300 $1,800

Minus direct controllable

fixed costs - 500 - 30 -18 - 12 - 100 - 600

Controllable contrib margin $1,000 $200 $32 $ 8 $200 $1,200

Minus direct noncontrollable

fixed costs - 400 - 40 -20 - 15 - 100 - 500

Segment contrib margin $ 600 $160 $12 ($7) $100 $700

Minus common costs - 500

Net income $200

(2) The various contribution margins tell Walt that he is covering variable costs in every segment

of the business. But, the variable contribution margin ratios vary considerably, as follows:

Passenger Total

Freight Route 1 Route 2 Route 3 Total Operations

Contribution margin ratio 42.9% 25.6% 11.1% 13.3% 20.0% 36.0%

Clearly, Freight and Route 1 are carrying the firm. All managers are making profits on the

revenues and costs they control in their respective segments. But after all direct costs are

deducted, Route 3 is losing money. Depending on the interrelationships among routes,

Walter might consider using the Route 3 resources (people and equipment) elsewhere. Even

Route 2 is not a strong performer.

The $500,000 of common costs cannot be allocated to segments. He can get no better

measure of profits by allocating these costs to the segments. He might examine the contents

of the common costs to see if any of these costs are driven by a cost driver that would allow

Walter to link the costs with activities in each segment.

CASE 2B – Holiday Grammy

(1) Bazaar selection process: Alternatives

A B C D

Units 350 400 500 600

Selling price per house $6.75 $5.95 $5.45 $5.00

Sales revenue $2,362.50 $2,380 $2,725 $3,000

Variable costs:

Materials & labor ($2.50) $875.00 $1,000 $1,250 $1,500

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-28

Bazaar fee 300

Total variable costs $875.00 $1,000 $1,250 $1,800

Variable contribution margin $1,487.50 $1,380 $1,475 $1,200

Fixed costs:

Kitchen ($60 per weekend) $120.00 $ 120 $ 120 $ 120

Bazaar fee 50.00 30 24

Total fixed costs $170.00 $ 150 $ 144 $ 120

Total costs $1,045.00$1,150 $1,394 $1,920

Net profit $1,317.50 $1,230 $1,331 $1,080

Minimum profit per house ($1.25) $437.50 $500 $625 $750

Residual profit after minimum $880.00 $730 $706 $330

Contribution margin per house $4.25 $3.45 $2.95 $2.00

Pick Alternative C if the goal is the highest total net profit. On the other hand, if her minimum

profit is viewed as a cost of her time, Alternative A is preferred. This is a useful discussion

point. Is her time "free?" Is the "most" profit the real goal?

(2) The answer to Part (2) depends on Holiday Grammy’s deal with her hired assistant. Assume

that she takes all the profit from the bazaar she attends (C) and gives all the profits above the

minimum of $1.25 per house to the person she hires.

Decision Rule # 1: She wants to make the most money in total from selling gingerbread

houses at the two bazaars (Her hired person is a daughter; she views profit as “family profit.”).

Assume that she selected Alternative C in Part (1). The maximum amount she could pay

would be the profit earned from the next most profitable bazaar adjusted for any changes in

costs or revenues. Here it is important to consider the minimum of $1.25 per house as a cost

since she would not participate if she could not clear the $1.25 per house.

Alternatives

A B D B (for Part 3)

Units 350 400 600 250

Selling price per house $ 6.75 $5.95 $5.00

$5.95

Sales revenue $ 2,362.50 $2,380 $3,000 1,475.50

Variable costs:

Materials & labor ($2.50) $ 875.00 $1,000 $1,500 625.00

Bazaar fee 300

Total variable costs $ 875.00 $1,000 $1,800 $625.00

Fixed csts:

Kitchen ($60 per weekend) $ 60.00 $ 60 $ 120

Bazaar fee 50.00 30 $30.00

Total fixed costs $ 110.00 $ 90 $ 120 $30.00

Total costs $ 985.00 $1,090 $1,920 $655.00

Net profit $1,377.50 $1,290 $1,080 $820.50

Minimum profit per house ($1.25) $ 437.50 $500 $750 $312.50

Residual profit after minimum $ 940.00 $790 $330 $508.00

Note: Use the total number of houses to be made in calculating the kitchen cost when

combining alternatives.

Alternative A would be selected. She could pay up to $940 and cover her costs, make a

minimum of $1.25 per house, and still breakeven.

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-29

If the alternative selected in Part (1) was Alternative A, the same analysis would show that

Alternative C is the choice in Part (2). $766 is the amount that could then be paid, while she

covers costs, makes her $1.25 minimum, and breaks even.

Decision Rule # 2: She wants to make the most money for herself only from selling

gingerbread houses at the two bazaars. If this is the case, she will select Alternative D, since

Alternative D sells the most houses (600) giving her the profit from Alternative C plus $1.25

per house from Alternative D, or a total profit for her of $2,081.

(3) Again, the answer depends on her decision rule (with surprising results if we focus only on her

earnings alone.

Decision Rule # 1: Maximize profits for the business as a total; and pay all helpers 50% of

the profit above the $1.25 per house minimum for Holiday Grammy. She can make and sell

only 1,200 units (4 weekends x 300 units). If she goes to Alternative C, she would begin with

the residual profit from Part (2):

Alternatives

A B D

Residual profit after minimum $940 $790 $330

She would hire someone to go to Alternative A and pay $470 ($940 2). The Gingerbread

Lady would earn an additional $470 (over the $1.25 minimum), in addition to the profits from

Alternative C.

Now, the question that remains is: Should she send someone to either Alternative B or D with

the remaining houses? Of the original 1,200 houses, she will send 350 to Alternative A and

500 to Alternative C, leaving 350 houses that could be made and sold at either Alternative B

or D. The analysis now is:

Alternatives

B D

Units 350 350

Selling price per house $5.95 $5.00

Sales revenue $2,082.50 $1,750

Variable costs:

Materials & labor ($2.50) $875.00 $875

Bazaar fee 175

Total variable costs $875.00 $1,050

Fixed costs:

Kitchen ($60 per weekend) $ 60.00 $ 60

Bazaar fee 30.00

Total fixed costs $ 90.00 $ 60

Total costs $965.00 $1,110

Net profit $1,117.50 $640

Minimum profit per house ($1.25) $437.50 $437.50

Residual profit after minimum $680.00 $202.50

She could hire a second person to attend Alternative B. This would mean splitting the $680

with the second person. But it would contribute $340 to her overall profits, even after the

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-30

$1.25 per house has been earned.

The business profit (without payments of helpers) then is: $1,331 + $1,377.50 + $1,117.50 or

$3,826. After paying helpers 50% of the residual profit, her profit is: $1,331 + ($437.50 +

$470) + ($437.50 + $340) or $3,016.

Decision Rule # 2: Maximize profits for the Holiday Grammy only; and pay the first helper all

the profit over the minimum of $1.25 and the helper for the 3 rd bazaar 50% of the profit above

the $1.25 per house minimum for Holiday Grammy. Now, the decision result changes. If she

were to attend C, send 2nd helper to A, and the 3rd helper to B she would earn $2,546 – $1,331

+ $437.50 + ($437.50 + $340).

Because Alternative D sells more houses, using this specific decision rule – assuming Part (3)

follows Part (2), she should actually do Alternative A, then Alternative D, and finally Alternative

B. At the margin and since she is selling all houses she can make, she would like to sell the

houses with the highest contribution margin per house. (Except that the 2 nd bazaar attended

will generate her profit only to the extent of $1.25 per unit.) Therefore, she would send her 1 st

helper to the bazaar that sells the most units and pays the helper the lowest profits. It also

means that the 3rd bazaar sells 250 units. Profits from this option are: $1,331 + $750 +

($312.50 + $254) or $2,647.50 – a higher profit than C, then A, and then B.

Managerial Accounting Solutions, Schneider/Sollenberger, 4th Edition, Chapter 2, Page 2-31

You might also like

- GG Toys WAC (Final)Document9 pagesGG Toys WAC (Final)Jasper Andrew Adjarani78% (9)

- Merchandising - Review Materials (Problems)Document65 pagesMerchandising - Review Materials (Problems)julsNo ratings yet

- 4a Standard Costs and Analysis of VariancesDocument3 pages4a Standard Costs and Analysis of VariancesGina TingdayNo ratings yet

- Labor Law Module 1Document8 pagesLabor Law Module 1ALYSSA NOELLE ARCALAS100% (1)

- xACC 213Document10 pagesxACC 213CharlesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 Managerial AccountingDocument4 pagesChapter 6 Managerial AccountingLydia SamosirNo ratings yet

- Ident IFICATIONDocument17 pagesIdent IFICATIONJamaica MarjadasNo ratings yet

- D7Document11 pagesD7neo14No ratings yet

- Final Exam Finacc1Document11 pagesFinal Exam Finacc1Grace A. ManaloNo ratings yet

- College Grading System PDFDocument85 pagesCollege Grading System PDFFlor DamasoNo ratings yet

- IA3 Correction of ErrorsDocument4 pagesIA3 Correction of ErrorsRC PalabasanNo ratings yet

- ACTG22a Midterm B 1Document5 pagesACTG22a Midterm B 1Kimberly RojasNo ratings yet

- Activity 3Document3 pagesActivity 3Alexis Kaye DayagNo ratings yet