Language Learning Strategies of Turkish PDF

Language Learning Strategies of Turkish PDF

Uploaded by

irfan8791Copyright:

Available Formats

Language Learning Strategies of Turkish PDF

Language Learning Strategies of Turkish PDF

Uploaded by

irfan8791Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Language Learning Strategies of Turkish PDF

Language Learning Strategies of Turkish PDF

Uploaded by

irfan8791Copyright:

Available Formats

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching

ISSN: 2537 - 1754

ISSN-L: 2537 - 1754

Available on-line at: www.oapub.org/edu

10.5281/zenodo.202896 Volume 1│Issue 1│2016

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC

STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

Prof. Dinçay Köksal1, Ömer Gökhan Ulum2i

1Çanakkale 18 Mart University, Turkey

2Adana Science and Technology University, Turkey

Abstract:

This study investigates the language learning strategy use of Turkish and Arabic

students enrolled in middle schools and having different cultural and linguistic

backgrounds. Using a strategy inventory for language learning, the study examines the

cross-cultural differences in strategy use of the mentioned students while learning

English as a foreign language. The study has found out that though there are a number

of cross-cultural similarities in the language learning strategy use between Turkish and

Arabic students, there are also significant differences between them. For instance,

Turkish students prefer to use a dictionary while reading English texts, but Arabic

students generally do not use a dictionary in their reading activities. Conclusions and

pedagogical implications of the findings are discussed in the study.

Keywords: language learning strategies, cross cultures, Strategy Inventory for

Language Learning (SILL)

1. Introduction

There has been an outstanding deviation within the issue of language learning

and teaching over the last decades with more and more stress put on students and

learning rather than on teachers and teaching. With this transformation, how students

deal with new data and what type of strategies they use to comprehend, to acquire or to

remember the data have been the main interest of the researchers in the field of foreign

language learning (Hismanoglu, 2000; Lessard-Clouston, 1997). Learning outcomes are

highly determined by learning strategies. Thus, making students perceive particular

Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved 122

Published by Open Access Publishing Group ©2015.

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

strategies is a fundamental element which upgrades the learning competence (Lihui

and Yanmin, 2014). Strategies are not one time actions, but a productive order of actions

that learners industriously employ. There are a large number of English language

learning strategies (Oxford, 1996). Language learning strategies refer to both language

learning strategies and language use strategies. Being together, they form the actions

chosen by learners either to develop the learning of a language, the practice of it, or

both together (Cohen, 1995).

Learning strategies which are generally intentional and goal-oriented,

particularly in the initial phases of working on a different language activity are

practices that assist learning. Whenever a learning strategy is well known after ongoing

use, it may be employed automatically, if needed however; many learners will be able

to bring out the strategy again (Chamot, 2005). Every language learner uses language

learning strategies in the learning practices. It is not sensible to favor the idea that each

language learner uses identical language learning strategies and tries to look for same

solutions to various problems, because the determinants like age, gender, personality,

motivation, self-concept, life-experience, learning style, excitement, anxiety, culture, etc.

influence the manner in which learners acquire the target language (Tseng, 2005). With

all these in mind, the ultimate aim of this study is to discover whether there is any

difference between Turkish and Arabic students’ learning English as a foreign

language. Therefore, the following research questions were put forward:

1. What are the language learning strategies the 6th grade Turkish students prefer

to use?

2. What are the language learning strategies the 6th grade Arabic students prefer to

use?

3. Is there any significant difference between Turkish and Arabic students in terms

of language learning strategy use?

2. Language Learning Strategies

Since 1970s, cognitive revolution has given way to a piling attraction of language

learning and language learners, and considerable sympathy has been felt for language

learning strategies ever since. The science was transformed from behaviouristic one into

cognitive one in both psychology and education fields. Studies contributed many

attempts to define the cognitive actions in all facets of learning, containing language

learning as well. First language researches emphasized outwardly observable

behaviours of learners, defined strategic behaviours, eventually classified those

strategic behaviours, and associated them with language competency (Zare, 2012).

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 123

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

Learning strategy is a significant determinant of learning sufficiency, as well as being

the subject of psycholinguistics. Strategies may concentrate on opted dimensions of new

data such as examining and controlling data through acquisition, arranging and

clarifying new data through encoding, testing learning when finished, confirming that

learning will be adequate to pacify nervousness etc. (Lihui and Yanmin, 2014).

The significance of language learning strategies has been confirmed and stressed

extensively. Language learning strategies are one of the fundamental dimensions of

successful language learning (Su, 2005). It’s necessary to teach a spectrum of methods

and strategies and get learners to have a more progressive portrayal in the learning

phase. Learners, who are aware of a series of learning strategies, can apply the most

suitable strategy, conclude how to follow it and when to replace it with another one.

Through teaching various strategies, teachers can also consider learners’ multiple

intelligences and let the learners take the advantage of diverse strengths (Edvardsdóttir,

2010). There is no agreement on what forms a learning strategy or how it is different

from other forms of learner actions. Learning strategies are often mixed with each other

in language learning process and are often applied to the same approach. Moreover,

even within the range of activities based on specific learning strategies, there is a high

complication about the explanations of particular strategies and the hierarchic

connection within these strategies (O’Malley et al, 1985).

Although Pask (1988) states that there are apparently unique learning strategies,

according to what Oxford (1990) puts forward that there is no full consensus on

absolutely what and how strategies exist, how they should be labeled and classified,

and also on whether it will be probable to form an authentic, scientifically confirmed

hierarchy of strategies.

2.1. Categorization of Language Learning Strategies

A large number of strategies can be employed by students: meta-cognitive

techniques for regulating, checking and focusing on one's own learning; affective

strategies for dealing with emotions or approaches; social strategies for collaborating

with others in the learning phase; cognitive strategies for connecting new data with

remaining background knowledge and for evaluating and grouping it; memory

strategies for putting new data in memory box and for getting it back when necessary;

and compensation strategies like figuring out or using gestures to prevail failures and

cracks in one's existing language competency (Oxford, 1989). That’s to say, Oxford

(1990) classified language learning strategies in 6 categories. Oxford's (1990)

categorization covers meta-cognitive strategies assisting students to adjust their

learning, affective strategies including the learner's emotional necessities like courage,

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 124

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

social strategies giving way to boosting interaction with the objected language and also

cognitive strategies in which students deal with their learning, memory strategies

employed to store data, as well as compensation strategies supporting students to

surmount the data gaps to carry on conversation.

3. Culture and Language Learning Strategies

The student’s objectives, the context of the learning atmosphere, and the cultural

values of the student’s community can be assumed to have a strong effect on selection

and approval of language learning strategies. For instance, in a culture that values

personal competition; excellent language learners may choose strategies that let them

work alone instead of social strategies that necessitate cooperation with others (Chamot,

2004).

As Oxford (1990) has emphasized, it would be unreasonable to make an effort for

ascribing one specific language learning approach to a particular cultural community.

Versions in strategy employment established on cultural schemata and environment

have naturally been argued in terms of strategy counts. For example, learners from

diverse cultures are said to employ particular groups of strategies more commonly than

others. Nevertheless, probably it is the use of strategies that has a bigger role in cultural

variation (Nisbet, Tindall and Arroyo, 2005). In English language instruction, teachers

generally stressed conveying language knowledge and working on language skills, but

disregarded the analogy of the diversities between Chinese and English cultures, for

instance. Consequently, it is not easy for learners to discard the impact of native

language. So, the learners are incapable of having the appropriate conversation skills in

English.

However, nowadays the case is no longer what it was before. Teachers certainly

own the capability to welcome the knowledge of the diversities between English and

Chinese cultures. Thus, it has become one of the teaching goals of English teachers to

include cultural knowledge and direct the learners to approve logical and practical

study strategies intently (Lihui and Yanmin, 2014). The Chinese EFL students had

identical learning strategies in conversations as western second language students did.

Yet Huang (1984) expressed that some strategies employed by the Chinese EFL students

were affected by Chinese culture (cited in Su, 2005).

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 125

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

4. Method

4.1. Participants

The data for the study were collected from Turkish and Arabic students who

were the 6th class EFL students. The Turkish students in the study were selected from

the most convenient and accessible schools in Adana, Turkey, while the Arabic students

in the study were selected from two Syrian primary schools in Adana, Turkey, as well.

The sample consisted of 251 Turkish and Arabic students in total: 126 Turkish and 125

Arabic, both of whom voluntarily participated in the study. High consideration was

taken in choosing urban and suburban Turkish schools from diverse populations that

represent the composition of students in Turkey, while two Syrian schools were

selected for the study as there were only two schools serving to Syrian refugees in

Adana, Turkey. In selecting the students, we employed the convenience sampling

method as the target population was too large, and therefore, not accessible (Castillo,

2009).

4.2. Instruments and Data Procedure

The study was carried out through quantitative and qualitative methods of data

collection. The instruments employed in the study were: (1) the Strategy Inventory for

Language Learning (SILL) designed by Oxford (1989), (2) a semi-structured interview

formed by the researchers. The inventory was administered to 126 Turkish students and

125 Arabic students while the interview was administered to 32 Turkish students and

14 Arabic students. The data of the interview were evaluated and presented in the

paper while the data gathered from the inventory were analyzed by means of

descriptive statistics. In other words, based on a descriptive research design, this paper

contained the data analysis of descriptive statistics. In this sense, SPSS 20.0, a Statistical

Program for Social Sciences was capitalized on to report the perceptions of language

teachers in numerical data. For the analysis of the data obtained from the inventory,

mean(×) was used as a statistical technique to find out the rate of agreement related to

the items about language learning strategies. The following scores were used in order to

compare the means (×) of the views specified: (1) Never or almost never true of me:

1.00 – 1.49, (2) Usually not true of me: 1.50 – 2.49, (3) Somewhat true of me: 2.50 – 3.49,

(4) Usually true of me: 3.50 – 4.49, (5) Always or almost always true of me: 4.50 – 5.00.

The assumption of normality was tested via examining Kolmogorov-Smirnov

and Shapiro-Wilk suggesting that normality was a reasonable assumption. As a result

of these assumptions, t-test was used for the gender. When looking at the t-test results

of the participants, gender is not an effective factor influencing the participants’

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 126

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

responds on language learning strategies. Besides, Cronbach’s Alpha was used in order

to test the reliability of the scale, which was found highly reliable. Responds from 251

participants in total were used in the analysis.

5. Data Analysis and Results

In this section, the results of the study and the findings are described based on

the data obtained from the participants by means of the instruments. They are grouped

under the titles of the categories from the questionnaire, as well as the interview.

5.1. Results Pertaining to Remembering More Effectively

There are 9 items related to the part remembering more effectively in Strategy

Inventory for Language Learning (SILL), the aim of which is to specify the perspectives

of Turkish and Arabic EFL students. Table 1 clarifies the results pertaining to the related

strategies.

Table 1: Remembering More Effectively

Turkish Arab

M SD M SD

1. I think of relationships between what I already know and new things I 4.11 0.825 3.78 1.222

learn in English.

2. I use new English words in a sentence so I can remember them. 3.86 1.045 3.79 1.444

3. I connect the sound of a new English word and an image or picture of the 4.07 .877 4.23 0.824

word to help me remember the word.

4. I remember a new English word by making a mental picture of a situation 3.79 1.161 3.55 1.393

in which the word might be used.

5. I use rhymes to remember new English words. 2.88 1.210 3.08 1.473

6. I use flashcards to remember new English words. 3.31 1.306 2.89 1.424

7. I physically act out new English words. 3.30 1.286 3.00 1.385

8. I review English lessons often. 4.09 1.023 3.98 1.099

9. I remember new English words or phrases by remembering their location 3.80 1.009 4.10 1.045

on the page, on the board, or on a street sign.

Note. SD=Standard Deviation

First of all, for the 1st item, regarding I think of relationships between what I already

know and new things I learn in English it is clearly understood from the table that the

mean (x̅) score for this part is 4.11 for Turkish students, while it is 3.78 for Arabic

students. These scores indicate that Item 1 is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic

students.

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 127

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

When it comes to the 2nd item, regarding I use new English words in a sentence so I

can remember them one can easily understand from the table that the mean (x̅) score for

this part is 3.86 for Turkish students, while it is 3.79 for Arabic students, which clearly

indicate that Item 2 is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

In terms of the 3rd item, regarding I connect the sound of a new English word and an

image or picture of the word to help me remember the word comprehension, the mean (x̅) score

for this part is 4.07 for Turkish students, while it is 4.23 for Arabic students, which mean

that Item 3 is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

Regarding the 4th item I remember a new English word by making a mental picture of a

situation in which the word might be used, the table illustrates that the mean (x̅) score for

Turkish students’ strategy use is 3.79, while it is 3.55 for Arabic students, which point

out that Item 4 is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

For the 5th item, it is clearly observed from the table that it is somewhat true of

both Turkish and Arabic students by looking at the mean (x̅) scores: 2.88 for Turkish

students, and 3.08 for Arabic students.

Besides, for the 6th item I use flashcards to remember new English words, the mean (x̅)

score for Turkish students (3.31), as well as for Arabic students (2.89) simply display

that this item is somewhat true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

By looking at the 7 th item, regarding I physically act out new English words, it is

easily understood that this item is again somewhat true of both Turkish and Arabic

students based on the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students which is 3.30, besides the

mean (x̅) score for Arabic students which is 3.00.

Moreover, for the 8 th item I review English lessons often, we can easily comprehend

from the table that this item is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students, which

is observed from the mean (x̅) score 4.09 for Turkish students, and 3.98 for Arabic

students.

At the same time, by looking at the 9 th item, one can easily see that the mean (x̅)

score for this part is 3.80 for Turkish students, while it is 4.10 for Arabic students. These

scores suggest that Item 9 is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

5.2. Results Pertaining to Using all your Mental Processes

There are 14 items related to the part using all your mental process in Strategy

Inventory for Language Learning (SILL), the aim of which is to specify the perspectives

of Turkish and Arabic EFL students. Table 2 clarifies the results pertaining to the related

strategies.

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 128

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

Table 2: Using all your Mental Processes

Turkish Arab

M SD M SD

10. I say or write new English words several times. 4.44 0.942 3.87 1.191

11. I try to talk like native English speakers. 3.55 1.434 3.71 1.424

12. I practice the sounds of English. 3.76 1.036 3.24 1.347

13. I use the English words I know in different ways. 3.50 1.237 3.62 1.400

14. I start conversations in English. 3.76 1.182 3.84 1.016

15. I watch English language TV shows spoken in English or go to movies 2.88 1.451 3.48 1.147

spoken in English.

16. I read for pleasure in English. 3.03 1.376 3.24 1.416

17. I write notes, messages, letters, or reports in English. 3.12 1.453 3.26 1.350

18. I first skim an English passage (read over the passage quickly) then go 3.70 1.271 3.24 1.522

back and read carefully.

19. I look for words in my own language that are similar to new words in 4.18 1.091 3.62 1.365

English.

20. I try to find patterns in the English. 3.58 1.188 3.12 1.325

21. I find the meaning of an English word by dividing it into parts that I 4.23 1.013 3.58 1.345

understand.

22. I try not to translate word for word. 3.73 1.363 3.70 1.211

23. I make summaries of information that I hear or read in English. 3.09 1.364 3.65 1.338

Note. SD=Standard Deviation

By looking at the 10 th item I say or write new English words several times it is clearly

understood from Table 2 that the mean (x̅) score for this part is 4.44 for Turkish

students, while it is 3.87 for Arabic students. These scores clearly display that Item 10 is

usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

Regarding the 11th item I try to talk like native English speakers it can easily be

observed that the mean (x̅) score for this part is 3.55 for Turkish students, while it is 3.71

for Arabic students, which clearly suggests that Item 11 is also usually true of both

Turkish and Arabic students.

On the other hand, by looking at the 12 th item I practice the sounds of English, the

mean (x̅) score for this part is 3.76 for Turkish students and 3.24 for Arabic students,

which means that Item 12 is usually true of Turkish students, while it is somewhat true

of Arabic students.

With reference to the 13th item I use the English words I know in different ways, the

table illustrates that the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students’ strategy use is 3.50, while it

is 3.62 for Arabic students, which highlights that Item 13 is usually true of both Turkish

and Arabic students.

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 129

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

For the 14th item I start conversations in English, it is figured out from the table that

it is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students by looking at the mean (x̅) scores:

3.76 for Turkish students, and 3.84 for Arabic students.

Besides, for the 15th item I watch English language TV shows spoken in English or go

to movies spoken in English, the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students (2.88), as well as for

Arabic students (3.48) simply display that this item is somewhat true of both Turkish

and Arabic students.

By looking at the 16th item, regarding I read for pleasure in English, it is easily

perceived that this item is somewhat true of both Turkish and Arabic students based on

the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students which is 3.03, besides the mean (x̅) score for

Arabic students which is 3.24.

Moreover, for the 17 th item I write notes, messages, letters, or reports in English, we

can easily comprehend from the table that this item is somewhat true of both Turkish

and Arabic students, which is observed from the mean (x̅) score 3.12 for Turkish

students, and 3.26 for Arabic students.

Additionally, by looking at the 18th item I first skim an English passage (read over the

passage quickly) then go back and read carefully, one can easily see that the mean (x̅) score

for this part is 3.70 for Turkish students, while it is 3.24 for Arabic students, which

reveals that Item 18 is usually true of Turkish students and somewhat true of Arabic

students.

Furthermore, seeing the 19th item, it is clearly recognized from the table that the

mean (x̅) score for this part is 4.18 for Turkish students, while it is 3.62 for Arabic

students, which reveals that Item 19 is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

By looking at the 20th item I try to find patterns in the English, the mean (x̅) score

for Turkish students (3.58), as well as for Arabic students (3.12) simply emphasize that

this item is usually true of Turkish students and somewhat true of Arabic students.

With respect to the 21st item I find the meaning of an English word by dividing it into

parts that I understand, it is easily comprehended that this item is usually true of both

Turkish and Arabic students based on the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students which is

4.23, besides the mean (x̅) score for Arabic students which is 3.58.

At the same time, regarding the 22nd item I try not to translate word for word, we

can easily understand that this item is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

This is clarified by the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students (3.73), besides the mean (x̅)

score for Arabic students (3.70).

Finally, by looking at the 23 rd item, one can easily see that the mean (x̅) score for

this part is 3.09 for Turkish students, while it is 3.65 for Arabic students. These scores

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 130

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

highlights that Item 23 is somewhat true of Turkish students, while usually true of

Arabic students.

5.3. Results Pertaining to Compensating for Missing Knowledge

There are 6 items related to the part compensating for missing knowledge in Strategy

Inventory for Language Learning (SILL), the aim of which is to specify the perspectives

of Turkish and Arabic EFL students. Table 3 clarifies the results pertaining to the related

strategies.

Table 3: Compensating for Missing Knowledge

Turkish Arab

M SD M SD

24. To understand unfamiliar English words, I make guesses. 4.00 1.165 3.18 1.526

25. When I can't think of a word during a conversation in English, I use 3.57 1.248 3.57 1.398

gestures.

26. I make up new words if I do not know the right ones in English. 2.73 1.448 3.24 1.272

27. I read English without looking up every new word. 2.44 1.675 4.05 1.049

28. I try to guess what the other person will say next in English. 3.45 1.156 3.74 1.237

29. If I can't think of an English word, I use a word or phrase that means 4.06 0.927 3.99 0.893

the same thing.

Note. SD=Standard Deviation

The 24th item regarding To understand unfamiliar English words, I make guesses

displays that the mean (x̅) score for this part is 4.00 for Turkish students, while it is 3.18

for Arabic students. These scores illustrate that Item 24 is usually true of Turkish

students, but somewhat true for Arabic students.

Regarding the 25th item When I can't think of a word during a conversation in English,

I use gestures it can easily be observed that the mean (x̅) score for this part is 3.57 for

both Turkish and Arabic students, which clearly shows that Item 25 is usually true of

both Turkish and Arabic students.

On the other hand, by looking at the 26 th item I make up new words if I do not know

the right ones in English, the mean (x̅) score for this part is 2.73 for Turkish students and

3.24 for Arabic students, which means that Item 26 is somewhat true of both Turkish

and Arabic students.

With respect to the 27th item I read English without looking up every new word, the

table highlights that the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students’ strategy use is 2.44, while

it is 4.05 for Arabic students, which highlights that Item 27 is usually not true of Turkish

students, yet usually true of Arabic students.

For the 28th item I try to guess what the other person will say next in English, it is

found out from the table that it is somewhat true of Turkish students, but usually true

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 131

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

of Arabic students by looking at the mean (x̅) scores: 3.45 for Turkish students and 3.74

for Arabic students.

Besides, for the 29th item If I can't think of an English word, I use a word or phrase that

means the same thing, the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students (4.06), as well as for Arabic

students (3.99) simply display that this item is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic

students.

5.4. Results Pertaining to Organizing and Evaluating your Learning

There are 9 items related to the part organizing and evaluating your learning in

Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL), the aim of which is to specify the

perspectives of Turkish and Arabic EFL students. Table 4 clarifies the results pertaining

to the related strategies.

Table 4: Organizing and Evaluating Your Learning

Turkish Arab

M SD M SD

30. I try to find as many ways as I can to use my English. 4.14 1.025 3.80 1.299

31. I notice my English mistakes and use that information to help me do 4.23 0.964 4.20 0.879

better.

32. I pay attention when someone is speaking English. 4.22 0.866 3.92 1.333

33. I try to find out how to be a better learner of English. 3.97 1.189 4.13 1.010

34. I plan my schedule so I will have enough time to study English. 3.42 1.273 3.57 1.206

35. I look for people I can talk to in English. 3.49 1.337 3.76 1.320

36. I look for opportunities to read as much as possible in English. 3.53 1.100 3.63 1.341

37. I have clear goals for improving my English skills. 4.15 1.028 3.60 1.367

38. I think about my progress in learning English. 4.18 0.991 3.17 1.032

Note. SD=Standard Deviation

When looking at Table 4, for the 30th item I try to find as many ways as I can to use

my English, it is clearly understood that the mean (x̅) score for this part is 4.14 for

Turkish students, while it is 3.80 for Arabic students, which indicate that Item 30 is

usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

By looking at the 31st item regarding I notice my English mistakes and use that

information to help me do better, one can easily understand from the table that the mean

(x̅) score for this part is 4.23 for Turkish students, while it is 4.20 for Arabic students,

which display that Item 31 is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

In terms of the 32nd item, regarding I pay attention when someone is speaking

English, the mean (x̅) score for this part is 4.22 for Turkish students, while it is 3.92 for

Arabic students, which means that Item 32 is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic

students.

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 132

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

Regarding the 33rd item I try to find out how to be a better learner of English, the table

illustrates that the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students’ strategy use is 3.97, while it is

4.13 for Arabic students, which points out that Item 33 is usually true of both Turkish

and Arabic students.

For the 34th item I plan my schedule so I will have enough time to study English, it is

easily seen from the table that it is somewhat true of Turkish students, but usually true

of Arabic students by looking at the mean (x̅) scores: 3.42 for Turkish students, and 3.57

for Arabic students.

Besides, for the 35th item I look for people I can talk to in English, the mean (x̅) score

for Turkish students (3.49), as well as for Arabic students (3.76) illustrate that this item

is somewhat true of Turkish students, yet usually true of Arabic students.

By looking at the 36th item, regarding I look for opportunities to read as much as

possible in English, it is simply conceived that this item is usually true of both Turkish

and Arabic students based on the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students which is 3.53,

besides the mean (x̅) score for Arabic students which is 3.63.

Moreover, for the 37th item I have clear goals for improving my English skills, we can

easily comprehend from the table that this item is usually true of both Turkish and

Arabic students, which is observed from the mean (x̅) score 4.15 for Turkish students,

and 3.60 for Arabic students.

On the other hand, by looking at the 38 th item, one can easily see that the mean

(x̅) score for this part is 4.18 for Turkish students, while it is 3.17 for Arabic students.

These scores suggest that Item 38 is usually true of Turkish students, but somewhat true

of Arabic students.

5.5. Results Pertaining to Managing Your Emotions

There are 6 items related to the part managing your emotions in Strategy Inventory

for Language Learning (SILL), the aim of which is to specify the perspectives of Turkish

and Arabic EFL students. Table 5 clarifies the results pertaining to the related strategies.

Table 5: Managing Your Emotions

Turkish Arab

M SD M SD

39. I try to relax whenever I feel afraid of using English. 3.96 1.189 3.60 1.344

40. I encourage myself to speak English even when I am afraid of making a 4.00 1.193 3.96 1.207

mistake.

41. I give myself a reward or treat when I do well in English. 3.69 1.267 3.63 1.370

42. I notice if I am tense or nervous when I am studying or using English. 3.43 1.305 3.76 1.403

43. I write down my feelings in a language learning dairy. 2.60 1.475 3.12 1.396

44. I talk to someone else about how I feel when I am learning English. 3.35 1.292 3.72 1.375

Note. SD=Standard Deviation

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 133

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

With respect to the 39th item regarding I try to relax whenever I feel afraid of using

English, the mean (x̅) score is 3.96 for Turkish students, while it is 3.60 for Arabic

students. These scores show that Item 39 is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic

students.

Regarding the 40th item I encourage myself to speak English even when I am afraid of

making a mistake, it can easily be observed that the mean (x̅) score for this part is 4.00 for

Turkish students and 3.96 for Arabic students, which clearly show that Item 40 is

usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

Additionally, by looking at the 41st item I give myself a reward or treat when I do

well in English, the mean (x̅) score for this part is 3.69 for Turkish students and 3.63 for

Arabic students, which mean that Item 41 is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic

students.

However, with respect to the 42nd item I notice if I am tense or nervous when I am

studying or using English, the table highlights that the mean (x̅) score for Turkish

students’ strategy use is 3.43, while it is 3.76 for Arabic students, which highlight that

Item 42 is somewhat true of Turkish students, yet usually true of Arabic students.

For the 43rd item I write down my feelings in a language learning dairy, it is found out

from the table that it is somewhat true of both Turkish and Arabic students, by looking

at the mean (x̅) scores: 2.60 for Turkish students and 3.12 for Arabic students.

Besides, for the 44th item I talk to someone else about how I feel when I am learning

English, the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students (3.35), as well as for Arabic students

(3.72) simply display that this item is somewhat true of Turkish students, but usually

true of Arabic students.

5.6. Results Pertaining to Learning with Others

There are 6 items related to the part learning with others in Strategy Inventory for

Language Learning (SILL), the aim of which is to specify the perspectives of Turkish

and Arabic EFL students. Table 6 clarifies the results pertaining to the related strategies.

Table 6: Learning with Others

Turkish Arab

M SD M SD

45. If I do not understand something in English, I ask the other person to slow 4.35 1.091 3.70 1.263

down or say it again.

46. I ask English speakers to correct me when I talk. 3.91 1.213 3.99 1.167

47. I practice English with other students. 3.83 1.129 4.03 1.135

48. I ask for help from English speakers. 3.86 1.188 3.77 1.249

49. I ask questions in English. 4.10 1.026 3.56 1.297

50. I try to learn about the culture of English speakers. 3.64 1.299 3.74 1.149

Note. SD=Standard Deviation

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 134

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

When we look at the 45th item regarding If I do not understand something in English,

I ask the other person to slow down or say it again, the mean (x̅) score is 4.35 for Turkish

students, while it is 3.70 for Arabic students. These scores show that Item 45 is usually

true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

Regarding the 46th item I ask English speakers to correct me when I talk, it can easily

be observed that the mean (x̅) score for this part is 3.91 for Turkish students and 3.99 for

Arabic students, which clearly show that Item 46 is usually true of both Turkish and

Arabic students.

Additionally, by looking at the 47 th item I practice English with other students, the

mean (x̅) score for this part is 3.83 for Turkish students and 4.03 for Arabic students,

which mean that Item 47 is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

Besides, with reference to the 48th item I ask for help from English speakers, the table

highlights that the mean (x̅) score for Turkish students’ strategy use is 3.86, while it is

3.77 for Arabic students, which display that Item 48 is usually true of both Turkish and

Arabic students.

For the 49th item I ask questions in English, it is understood from the table that it is

usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students, by looking at the mean (x̅) scores: 4.10

for Turkish students and 3.56 for Arabic students.

Finally, for the 50th item I try to learn about the culture of English speakers, the mean

(x̅) score for Turkish students (3.64), as well as for Arabic students (3.74) show that this

item is usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students.

5.7. Interview Results

As already discussed in the methodology above, interviews were implemented

with 32 Turkish students and 14 Arab students who voluntarily took part in the study.

According to what they declared, the Syrian (Arab) students had been learning English

since the 5th class of their primary education, while Turkish students had been learning

English since the 4th class of their primary education. The interview data were recorded

by the interviewers. The interviewers tried to stimulate the interviewees to declare their

perceptions appropriately. To present diverse views regarding language learning

strategies of diverse cultures, the data were tabulated accordingly under each question

in the interview. The questions and some main comments were summed up and

introduced in the Table 7. Furthermore, quotations, codes and frequencies from the

answers to the interview questions were given in Table 7, as well.

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 135

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

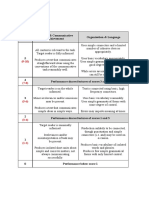

Table 7: Interview Results

Codes Frequency Quotations From Remarks of Students

Turkish Arab

The need of English 10 3 For my future career

6 7 To talk with foreigners

5 1 For enjoying English

4 - For course success

2 4 As lingua-franca

Definition of Language Learning Strategies 7 6 Memorization

5 - Revision

4 - Note-taking

3 - Writing everything 10 times

1 - Repetition

1 Translation

- 8 Reading

- 6 Watching original films

The usefulness of language learning strategies 32 14 Useful

- - Not useful

The most used language learning strategies 12 - Memorization

9 - Revision

8 - Note-taking

- 12 Asking the teacher

The least used language learning strategies 7 - Memorization

7 - Note-taking

4 - Revision

2 Asking others

What teachers can do to make use of language

learning strategies 5 Give homework

3 - Teach through games

2 - Give word lists

2 - Make us take notes

2 - Make us memorise

2 - Give tests

2 - Speak English rather than Turkish

- 14 Using modern equipment and educational

technologies

What is most difficult about learning English 11 - Learning vocabulary

4 - Pronunciation

6 8 Grammar

2 - Writing

- 4 Speaking

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 136

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

By looking at the interview results, we can easily see that in terms of how

Turkish and Arabic students see the need of English, most of the Turkish students (10

respondents) defined the need for their future career, while some Arabic students (3

respondents) mentioned about the same reason. On the other hand, while most of the

Arabic students (7 respondents) clarified the need as to talk with foreigners, almost the

same number of Turkish students (6) stated the same. Meanwhile, a high number of

Turkish students (5 respondents) stressed the need as for enjoying English, but only 1

Arabic respondent expressed this reason. Furthermore, 4 Turkish respondents specified

the need as to be successful at their courses, while no such answer was given by Arabic

participants. Lastly, while 4 Arabic respondents saw the need of English for it is a lingua

franca, only 2 Turkish participants suggested the same reason.

In terms of the definition of Language Learning Strategies, 7 Turkish students

defined it as Memorization, while 6 Arabic respondents defined it the same. Besides, 5

Turkish students defined it as Revision, 4 as Note-taking, 3 as Writing everything ten times,

1 as Repetition, and 1 as Translation, while 8 Arabic students defined it as Reading, and 6

as Watching original films.

Regarding the Usefulness of Language Learning Strategies, neither Turkish

respondents, nor Arabic respondents suggested that they are useless. That’s to say,

while 32 Turkish respondents found them useful, 14 Arabic respondents found them

useful as well. In other words, every respondent in the interview declared that he or she

believes in the usefulness of the Language Learning Strategies.

Referring to the most used Language Learning Strategies, 12 Turkish participants

stated Memorization, 9 Revision, and 8 Note-taking, while 12 Arabic students expressed

that they ask the teacher. However, for the least used Language Learning Strategies, 7

Turkish respondents declared Memorization, 7 Note-taking, and 4 Revision, while 2 Arabic

students expressed Asking others.

Considering What teachers can do to make use of language learning strategies, Turkish

students think that the teachers should give homework (5 respondents), teach through

games (3 respondents), give word lists (2 respondents), make students take notes

(2respondents), make students memorize (2 respondents), give tests (2 respondents),

and speak English rather than Turkish (2 respondents), while 14 Arabic students think

the teachers should use modern equipment and educational technologies.

Upon looking at What is most difficult about learning English, 11 Turkish students

declared Learning vocabulary, 6 Grammar, 4 Pronunciation, and 2 Writing, while 8 Arabic

students mentioned difficulty on Grammar, and 4 on Speaking.

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 137

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

6. Discussion and Conclusion

Researchers in educational field have diagnosed the significance of motivation

for successful second language learning for a very long time (Gardner and Clément,

1990). On looking at the need of learning English language, most of the Turkish

students perceive that English is significant for their future careers, while most of the

Arabic students see English language as a required tool for talking with foreign people.

The concept of Learning Strategy refers to learning-to-learn skills (Lee, 2010). When both

cross cultural groups defined Language Learning Strategies, the Turkish group put

forward the memorization concept and the Arabic group mentioned reading concept.

Both of these cross cultural groups find English useful. Besides, for most of the Turkish

students, learning vocabulary is the most difficult activity in learning English, while

grammar is the hardest aspect of English for most of the Arabic students. Additionally,

the most used language learning strategy is memorization for Turkish students, but the

case for Arabic students is that they ask the teacher. A number of factors have an effect

on learners’ using of language learning strategies. These factors may be age, gender,

approach, motivation, individual and cultural differences, learning styles, learner

beliefs on language learning, and teacher expectation (Ehrman and Oxford, 1990). When

it comes to the teacher’s role in language learning strategies, while most of the Turkish

students think that the teacher should give more homework (Cooper, Robinson, and

Patall, 2006), the Arabic students are in the view that the teacher should use modern

educational equipment and technology, the use of which aid teachers for a more

successful learning environment (Gömleksiz, 2004).

Strategy Inventory for Language learning (SILL) is the most effective tool in the

area of language learning strategies and covers the most extensive hierarchy of learning

strategies (Oxford, 1990). Vocabulary learning strategies are for instance seemingly

attractive for both teachers and learners (Gu, 2010). Regarding the section Remembering

More Effectively in the strategy inventory, both Turkish and Arabic students support

most of the items by indicating that the mentioned points are usually true of them,

though there are some items like using rhymes and flashcards to remember new English

words, and physically acting out new English words which are somewhat true of both

Turkish and Arabic students. Cognition is best comprehended by reviewing a form of

cognitive structure in which the mind focuses on the neural system and its biological

action (Ellman, 1997).

In terms of Using all Mental Processes in the strategy inventory, both Turkish and

Arabic students again support the mentioned points by revealing that the items are

usually true of them, however there are some items like watching TV shows in English or

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 138

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

going to movies in English, reading in English for pleasure, and writing notes, messages,

letters, or reports in English which are somewhat true of both Turkish and Arabic

students. Furthermore, while items like practicing the sounds of English, first skimming an

English passage then going back and reading carefully, and trying to find patterns are usually

true of Turkish students, they are somewhat true of Arabic students. The case is vice

versa in making summaries of information that the students hear or read in English, since it is

somewhat true of Turkish students, but usually true of Arabic students. It is necessary

to recognize the advantages of using a dictionary, especially in the early stages of

learning. Even an insufficient bilingual dictionary can help users by being a practical

reference resource. It is clear that by making the students more independent of the

teacher, the dictionary be a highly beneficial resource (Sarıgül, 2009).

When it comes to the section Compensating for Missing Knowledge in the strategy

inventory, there are cross culturally significant differences. First of all, referring to

reading English without looking up every new word, it is usually not true of Turkish

students, but amazingly usually true of Arabic students. The item making guesses to

understand unfamiliar English words is usually true of Turkish students, but somewhat

true of Arabic students. The case is again vice versa for the item trying to guess what the

other person will say next in English: somewhat true of Turkish respondents, usually true

of Arabic respondents. While the item making up new words if not knowing the right ones in

English is somewhat true of both Turkish and Arabic students, the rest of the items are

usually true of both groups. A metacognitive system has been formed for developing

learning strategy instruction covering four circular phases: planning, monitoring,

problem-solving, and evaluating (Chamot, 2004).

With reference to Organizing and Evaluating Learning, most points in the

inventory are usually true of both Turkish and Arabic students. Yet, some items under

this section like planning schedule to have enough time to study English, and looking for

people to talk in English are somewhat true of Turkish students, however usually true of

Arabic students. On the other hand, thinking about one’s his or her own progress in learning

English is usually true of Turkish students, yet somewhat true of Arabic students.

Managing emotions covers the competence to avert disturbing impulses and to

eliminate negative feelings (Goleman, 1995). When we look at the section Managing

one’s his or her emotions, most of the Turkish and Arabic students usually follow the

related strategies, though writing down their feelings in a language learning diary is

somewhat true of both groups. However, noticing tension or nervousness when studying or

using English, and talking to someone else about feelings when learning English are somewhat

true of Turkish students, but usually true of Arabic students. Most of kids’ knowledge

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 139

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

comes not from their involvement in the surrounding, but rather through the input of

others (Gelman, 2009).

Addressing to the section Learning with others in the strategy inventory, it is

clearly observed that all the related items within this category are usually true of both

Turkish and Arabic students. Learning strategy use resembles footballers’ tactics used

to win a match. Learners just like football players use tactics in order to be successful in

their learning (Lee, 2010). Like the tactical similarities and differences among football

players, here in this study there are a number of cross cultural similarities in the

language learning strategy use between Turkish and Arabic students, as well as

significant differences.

About the authors

Prof. Dinçay Köksal is the head of English Language Teaching Department at

Çanakkale 18 Mart University, Turkey. His research interests cover language

assessment, educational research, language teaching and learning, culture and

language, and foreign language education policy.

Ömer Gökhan Ulum is an instructor of English at Adana Science and Technology

University, Turkey. His research interests cover culture and language, applied

linguistics, pragmatics, discourse analysis, and educational research.

References

1. Castillo, J.J. (2009). Convenience Sampling. Retrieved 10 Nov. 2012 from

http://explorable.com/convenience-sampling.html

2. Chamot, A. U. (2004). Issues in language learning strategy research and teaching.

Electronic journal of foreign language teaching, 1/1, 14-26.

3. Chamot, A. U. (2005). Language learning strategy instruction: Current issues and

research. Annual review of applied linguistics, 25, 112-130.

4. Cohen, A. D. (1995). Second language learning and use strategies: Clarifying the

issues. University of Minnesota, the Center for advanced Research on Language

Acquisition.

5. Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve

academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987–2003. Review of

educational research, 76(1), 1-62.

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 140

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

6. Ehrman, M. & Oxford, R. (1990). Adult language learning styles and strategies in

an intensive training setting. Modern Language Journal, 74, 311-317.

7. Edvardsdóttir, E. (2010). Popular and useful learning strategies in language

acquisition amongst teenagers.

8. Ellman, R. (1997). Mental Processes--How the Mind Arises from the Brain.

9. Gardner, R. C., & Clément, R. (1990). Social psychological perspectives on second

language acquisition. John Wiley & Sons.

10. Gelman, S. A. (2009). Learning from others: Children’s construction of concepts.

Annual review of psychology, 60, 115.

11. Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ.

New York: Bantam Books.

12. Gömleksiz, M. N. (2004). Use of education technology in English classes. TOJET:

The Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 3(2).

13. Gu, Y. (2010). Learning strategies for vocabulary development. Reflections on

English Language Teaching, 9(2), 105-118.

14. Hismanoglu, M. (2000). Language learning strategies in foreign language

learning and teaching. The Internet TESL Journal, 6/8, 12-12.

15. Huang, X. H. (1984). An investigation of learning strategies in oral

communication that Chinese EFL learners in China employ. Master thesis,

Chinese University of Hong Kong. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No.

ED 249796)

16. Lessard-Clouston, M. (1997). Language learning strategies: An overview for L2

teachers. The Internet TESL Journal, 3/2, 69-80.

17. Lee, C. K. (2010). An overview of language learning strategies. Arecls, 7, 132-152.

18. Lihui, C. & Yanmin, Z. (2014). Application of Learning Strategies to Culture-

Based Language Instruction. Studies in Literature and Language, 9/1, 57-61.

19. Nisbet, D. L., Tindall, E. R., & Arroyo, A. A. (2005). Language learning strategies

and English proficiency of Chinese university students. Foreign Language Annals,

38/1, 100-107.

20. O'malley, J. M., Chamot, A. U., Stewner-Manzanares, G., Russo, R. P., & Küpper,

L. (1985). Learning strategy applications with students of English as a second

language. TESOL quarterly, 19/3, 557-584.

21. Oxford, R. (1989). The Role of Styles and Strategies in Second Language

Learning. ERIC Digest.

22. Oxford, R. (1989). Strategy Inventory for Language Learning (SILL). Retreived on

the 8th of May, 2016 from https://richarddpetty.files.wordpress.com/2010/03/sill-

english.pdf

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 141

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

23. Oxford, R.L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should

know. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle Publishers.

24. Oxford, R. L. (1996). Language learning strategies around he world: Cross-

cultural perspectives. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

25. Pask, G. (1988). Learning strategies, teaching strategies, and conceptual or

learning style. In Learning strategies and learning styles. Springer US. 83-100.

26. Sarıgül, E. (2009). The Importance of Using Dictionary in Language Learning and

Teaching. Selçuk Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakültesi Dergisi, (22), 153-157.

27. Su, M. H. M. (2005). A study of EFL technological and vocational college

students' language learning strategies and their self-perceived English

proficiency. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 2/1, 44-56.

28. Tseng, S. F. (2005). Language learning strategies in foreign language education.

WHAMPOA An Interdisciplinary Journal, 49, 321-328.

29. Zare, P. (2012). Language learning strategies among EFL/ESL learners: a review

of literature. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 2/5, 162-169.

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 142

Dinçay Köksal, Ömer Gökhan Ulum –

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGIES OF TURKISH AND ARABIC STUDENTS: A CROSS-CULTURAL STUDY

Creative Commons licensing terms

Author(s) will retain the copyright of their published articles agreeing that a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Internationa l License (CC BY 4.0) terms

will be applied to their work. Under the terms of this license, no permission is required from the auth or(s) or publisher for members of the community

to copy, distribute, transmit or adapt the article content, providing a proper, prominent and unambiguous attribution to the authors in a manner that

makes clear that the materials are being reused under permission of a Creative Commons License. Views, opinions and conclusions expressed in this

research article are views, opinions and conclusions of the author(s). Open Access Publishing Group and European Journal of Social Sciences Studies

shall not be responsible or answerable for any loss, damage or liability caused in relation to/arising out of conflicts of interest, copyright violations and

inappropriate or inaccurate use of any kind content related or integrated into the research work. All the published wo rks are meeting the Open Access

Publishing requirements and can be freely accessed, shared, modified, distributed and used in educational, commercial and non -commercial purposes

under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0).

European Journal of Foreign Language Teaching - Volume 1 │ Issue 1 │ 2016 143

You might also like

- Lesson Plan 3 - Parts of SpeechDocument5 pagesLesson Plan 3 - Parts of SpeechLovely Grace Garvez86% (7)

- Co Teaching and Push in Therapy Models HandoutDocument3 pagesCo Teaching and Push in Therapy Models HandoutvalentiakilianNo ratings yet

- RIASSUNTO Harmer Fifth EditionDocument156 pagesRIASSUNTO Harmer Fifth EditionpersefonekoretarotNo ratings yet

- Edtpa Pfa Planning CommentaryDocument9 pagesEdtpa Pfa Planning Commentaryapi-302413891100% (1)

- Framework For Language TeachingDocument5 pagesFramework For Language TeachingSantiago DominguezNo ratings yet

- Reading Writing and Learning in Esl 312 316Document5 pagesReading Writing and Learning in Esl 312 316JOSEFINA VIVALDA MATUSNo ratings yet

- Language and Literacy Levels Module 1.2 C: NominalisationDocument33 pagesLanguage and Literacy Levels Module 1.2 C: NominalisationNoureddine MaoudjNo ratings yet

- A Guide to the Teaching of English for the Cuban Context IFrom EverandA Guide to the Teaching of English for the Cuban Context IRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Picture PromtsDocument57 pagesPicture PromtsOxana Marinescu100% (2)

- 2015 - Language Learning Strategies in Chinese StudentsDocument8 pages2015 - Language Learning Strategies in Chinese StudentsDao Mai PhuongNo ratings yet

- Skripsi Nur Fitria LestariDocument218 pagesSkripsi Nur Fitria LestariLuckys SetiawanNo ratings yet

- Clil ModuleDocument80 pagesClil ModuleCut RifaNo ratings yet

- English CGDocument247 pagesEnglish CGJestia Lyn EngracialNo ratings yet

- Week 6 Planning To Teach (Formats of Lesson Plan)Document43 pagesWeek 6 Planning To Teach (Formats of Lesson Plan)Joyce Voon Ern CzeNo ratings yet

- English 5Document112 pagesEnglish 5gu50No ratings yet

- Teaching VocabularyDocument52 pagesTeaching VocabularyIca IcaNo ratings yet

- Aisha's Revised Peer ObservationDocument4 pagesAisha's Revised Peer ObservationHuda HamadNo ratings yet

- Six Proposals For Classroom TeachingDocument2 pagesSix Proposals For Classroom TeachingFebriRotamaSilabanNo ratings yet

- Language Teaching MethodologyDocument6 pagesLanguage Teaching MethodologyNoraCeciliaCabreraNo ratings yet

- Digital Literacies For Language Learning and TeachingDocument15 pagesDigital Literacies For Language Learning and TeachingOdette GabaudanNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan BookDocument97 pagesLesson Plan BookKhritish SwargiaryNo ratings yet

- Final Project Reading: Student's Name: Lizeth Mezquite ReyesDocument30 pagesFinal Project Reading: Student's Name: Lizeth Mezquite ReyesLizeth ReyesNo ratings yet

- Elements of Communicative Learning TaskDocument10 pagesElements of Communicative Learning TaskFernandoOdinDivinaNo ratings yet

- Teaching Reading in The Foreign Language Classroom: ResumoDocument8 pagesTeaching Reading in The Foreign Language Classroom: ResumoManu NogueiraNo ratings yet

- Cursive FirstDocument11 pagesCursive Firstsajid100% (1)

- Esol Lesson Plan TemplateDocument2 pagesEsol Lesson Plan TemplateMy Hanh MaiNo ratings yet

- Storytelling To Enhance Speaking and Listening Skills For English Young Learners: A Case Study at Language Centers in Binh Duong ProvinceDocument8 pagesStorytelling To Enhance Speaking and Listening Skills For English Young Learners: A Case Study at Language Centers in Binh Duong ProvinceHai Hau Tran100% (1)

- Points On A Continuum ESL Teachers Reporting On Collaboration (Pages 488-515)Document28 pagesPoints On A Continuum ESL Teachers Reporting On Collaboration (Pages 488-515)danigheoNo ratings yet

- Classroom Strategies For English Medium Teaching and LearningDocument56 pagesClassroom Strategies For English Medium Teaching and Learningsamanik swiftNo ratings yet

- Direct MethodDocument14 pagesDirect Methodapi-321172081No ratings yet

- Evaluation of English Textbook For 8Document13 pagesEvaluation of English Textbook For 8Lê Anh Thư - ĐHKTKTCNNo ratings yet

- Telegram App in Learning English: EFL Students' PerceptionsDocument12 pagesTelegram App in Learning English: EFL Students' Perceptionsnur colisNo ratings yet

- Fullerton Literature ReviewDocument8 pagesFullerton Literature Reviewapi-317399698No ratings yet

- Translanguaging in The ClassroomDocument26 pagesTranslanguaging in The ClassroomMihad BelmirNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Analysis WorksheetDocument3 pagesCurriculum Analysis WorksheetPauline HornerNo ratings yet

- Students' Errors in Using Inflectional MorphemesDocument28 pagesStudents' Errors in Using Inflectional MorphemesMayangsari DzulkifliNo ratings yet

- Long, M. H. (1983) - Does Second Language Instruction Make A Difference? TESOL Quarterly. 17-3, Pp. 359 - 382Document28 pagesLong, M. H. (1983) - Does Second Language Instruction Make A Difference? TESOL Quarterly. 17-3, Pp. 359 - 382anouar_maalej3624No ratings yet

- Theory - Total Physical ResponseDocument7 pagesTheory - Total Physical ResponseJorge PeluffoNo ratings yet

- Training IELTS Candidates For Writing Tasks A Comparative Study ofDocument20 pagesTraining IELTS Candidates For Writing Tasks A Comparative Study ofaridNo ratings yet

- Seminar Paper - RevisionsDocument22 pagesSeminar Paper - RevisionsMikhael O. SantosNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus (SEEL 106)Document5 pagesCourse Syllabus (SEEL 106)Aroma MangaoangNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical Approaches To Improving Reading ComprehensionDocument16 pagesPedagogical Approaches To Improving Reading ComprehensionLory-Anne PanemNo ratings yet

- Developing Reading Com PDFDocument10 pagesDeveloping Reading Com PDFAnDreez CamphozNo ratings yet

- Article About Reflective TeachingDocument12 pagesArticle About Reflective TeachingMary Grace RafagaNo ratings yet

- Teaching by Principle - Chapter 3Document128 pagesTeaching by Principle - Chapter 3Abdul Khalik Assufi100% (2)

- Harmer, Jeremy - Managing For Success - The Practice of English Language TeachingDocument9 pagesHarmer, Jeremy - Managing For Success - The Practice of English Language TeachingArthurNo ratings yet

- Sociolinguistics and Second Language Acquisition: Cahyo Setiyo Budiono Saiko Rudi Kasenda FalliandaDocument12 pagesSociolinguistics and Second Language Acquisition: Cahyo Setiyo Budiono Saiko Rudi Kasenda FalliandaFallianda Yanda100% (1)

- Teaching Reading-Reading StrategiesDocument2 pagesTeaching Reading-Reading StrategiessusudoNo ratings yet

- Differentiated Instruction: The Basic Steps Towards DifferentiatingDocument25 pagesDifferentiated Instruction: The Basic Steps Towards DifferentiatingkheirenNo ratings yet

- Reading: Principles of VocabularyDocument8 pagesReading: Principles of VocabularyJulie Ann GernaNo ratings yet

- Application For English LearnersDocument3 pagesApplication For English Learnersapi-257754554No ratings yet

- Klingner Et Al Collaborative Strategic ReadingDocument13 pagesKlingner Et Al Collaborative Strategic ReadingDONEHGUantengbanggetNo ratings yet

- Learning StrategiesDocument8 pagesLearning StrategiesAid EnNo ratings yet

- Communicative Approach To EslDocument1 pageCommunicative Approach To EslMario LandioNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER II - ANITA JATI LAKSANA - PBI'16-dikonversiDocument13 pagesCHAPTER II - ANITA JATI LAKSANA - PBI'16-dikonversiFebian AgungNo ratings yet

- Description of Krashen's Theory of Second Language AcquisitionDocument3 pagesDescription of Krashen's Theory of Second Language Acquisitionherlinda_effNo ratings yet

- Pedagogical ModelDocument28 pagesPedagogical ModelekanathNo ratings yet

- Teaching As Second Language in Indian Context.Document3 pagesTeaching As Second Language in Indian Context.gauri horaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Total Physical Response On The Dynamics and Interaction in The English ClassDocument130 pagesThe Effect of Total Physical Response On The Dynamics and Interaction in The English ClassMily SabagNo ratings yet

- Competency Based Language Teaching PDFDocument10 pagesCompetency Based Language Teaching PDFmichael torresNo ratings yet

- English ProficiencyDocument1 pageEnglish Proficiencyclaudia bayonaNo ratings yet

- Reading Interventions for the Improvement of the Reading Performances of Bilingual and Bi-Dialectal ChildrenFrom EverandReading Interventions for the Improvement of the Reading Performances of Bilingual and Bi-Dialectal ChildrenNo ratings yet

- World-Readiness Standards (General) + Language-specific document (GERMAN)From EverandWorld-Readiness Standards (General) + Language-specific document (GERMAN)No ratings yet

- All World Is Stage (Notes)Document6 pagesAll World Is Stage (Notes)irfan8791100% (1)

- The Shadow in The Rose Garden Short StoryDocument3 pagesThe Shadow in The Rose Garden Short Storyirfan8791No ratings yet

- Honesty Pays Honour and Corruption DishonourDocument2 pagesHonesty Pays Honour and Corruption Dishonourirfan8791100% (6)

- Realism and Its Implication To EducationDocument2 pagesRealism and Its Implication To Educationirfan8791No ratings yet

- La Historia Oculta de Cristo y Los 11 Pasos de Su Iniciacion 4 DVD by Jose Luis Parise 9870805930Document5 pagesLa Historia Oculta de Cristo y Los 11 Pasos de Su Iniciacion 4 DVD by Jose Luis Parise 9870805930Daniela Bernal Salavarrieta0% (1)

- Messenger That Deals With The Online Messaging. According To Statistics, A Total of 1.1Document17 pagesMessenger That Deals With The Online Messaging. According To Statistics, A Total of 1.1Nilcie LizarondoNo ratings yet

- Mythology and Folklore ModuleDocument20 pagesMythology and Folklore Modulecollegeofeducation161100% (1)

- PTE Templets (EDU - PLANNER)Document17 pagesPTE Templets (EDU - PLANNER)Bhishan officialNo ratings yet

- Learners Collocation Use in Writing Do ProficiencDocument9 pagesLearners Collocation Use in Writing Do ProficiencJaminea KarizNo ratings yet

- DEMO Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesDEMO Lesson PlanThao NganNo ratings yet

- Elevator TB 2Document113 pagesElevator TB 2Henny AngNo ratings yet

- SMR Sophia November2017Document1 pageSMR Sophia November2017Malvin NicodemusNo ratings yet

- Reading Circle Role SheetDocument5 pagesReading Circle Role SheetHusna KhaliesahNo ratings yet

- Microteach2-Figurativelanguage-Idioms-5 1Document5 pagesMicroteach2-Figurativelanguage-Idioms-5 1api-431617197No ratings yet

- (Group 2) Strategies and AutonomyDocument18 pages(Group 2) Strategies and Autonomyandri jupanoNo ratings yet

- Introductory Lesson For Hero/Morality UnitDocument4 pagesIntroductory Lesson For Hero/Morality UnitCaitlin HawkinsNo ratings yet

- Secrets of Quick Learning of A Foreign LanguageDocument4 pagesSecrets of Quick Learning of A Foreign LanguageResearch ParkNo ratings yet

- The Cambridge Ielts Course WorkbookDocument4 pagesThe Cambridge Ielts Course Workbookf5df0517100% (1)

- Fun With FlashcardsDocument350 pagesFun With FlashcardsIsmail OmranNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Clasa A 7aDocument3 pagesLesson Plan Clasa A 7aDragu VioletaNo ratings yet

- The Effect of Films With and Without Subtitles On Listening Comprehension of EFL LearnersDocument13 pagesThe Effect of Films With and Without Subtitles On Listening Comprehension of EFL LearnersIsabel BlackNo ratings yet

- Formal November ObservationDocument14 pagesFormal November Observationapi-267162784100% (1)

- Glossary Learning Log UNOi PDFDocument19 pagesGlossary Learning Log UNOi PDFBryan CastañedaNo ratings yet

- Tips For Developing The Literacy Skills of EllsDocument7 pagesTips For Developing The Literacy Skills of Ellsapi-501283068No ratings yet

- Teachers Guide 2015 PDFDocument28 pagesTeachers Guide 2015 PDFMiguel RabiaNo ratings yet

- PROJECT 2 - Daily Routines - Inglés I PDFDocument2 pagesPROJECT 2 - Daily Routines - Inglés I PDFmafe cardenas100% (1)

- Language Learning Materials DevelopmentDocument9 pagesLanguage Learning Materials DevelopmentEric MalasmasNo ratings yet

- Rubrik PenskoranDocument2 pagesRubrik PenskoranNORPAMELA BINTI MUHAMAD MOHTAR MoeNo ratings yet

- Report Card Rubric Grade 5Document4 pagesReport Card Rubric Grade 5stuart5271% (14)

- The Great GatsbyDocument5 pagesThe Great GatsbyTom HopkinsNo ratings yet