Date Time Co Curriculum - Final PDF

Date Time Co Curriculum - Final PDF

Uploaded by

Sarabjeet SinghCopyright:

Available Formats

Date Time Co Curriculum - Final PDF

Date Time Co Curriculum - Final PDF

Uploaded by

Sarabjeet SinghOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Date Time Co Curriculum - Final PDF

Date Time Co Curriculum - Final PDF

Uploaded by

Sarabjeet SinghCopyright:

Available Formats

DATE & TIME

CO-CURRICULUM

LESSON PLANS &

WORKSHOP GUIDE

OTTO VOCK

EDITING, CURRICULAR

RESOURCES & ADDITIONAL

LESSON PLANS

MOLLY NESTOR & PHIL KAYE

GUIDING PRINCIPLES

SARAH KAY & PHIL KAYE

MADE IN PARTNERSHIP WITH

PROJECT VOICE

BASED ON POEMS FROM

THE BOOK DATE & TIME

BY PHIL KAYE

Table of Contents

Overview

2 - Introduction & Guiding Principles For Teaching Spoken Word

4 - Standards Addressed

Lessons

5 - Speaking to Ourselves, Based on “The Author & The Author at 7 Years Old

Choose a Movie to Watch”

7 - Poems that are the Sum of Two Stories, Based on “Succulent”

9 - Personifying Our Objects, Based on “Numbers Man”

11 - Memories and Place, Based on “Camaro”

13 - Poems that Borrow Language, Based on “On Starting”

15 - Turning People into Places, Based on “My Grandmother’s Ballroom”

16 - Repetition as Theme, Based on “Appreciation Meditation”

Pedagogy

18 - General Workshop Guide / Sample Structure

20 - Tips for Including All Learners in Workshops - Universal Design for

Learning Strategies

22 - Influential Texts

23 - Contact Us

1 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Introduction

Thank you for reading Date & Time. We are so happy that you are interested in bringing

some of the pieces into the classroom. This co-curriculum contains several lesson plans based on

poems throughout the book, as well as a poetry workshop format to help you create your own

lesson plans. This is not a definitive guide - all of these are suggestions, and we encourage you to

shape the curriculum as you would like. We are hoping this curriculum will provide you with the

principles we find successful for engaging students and the practical tools to develop your own

approaches, prompts, and curriculum. Hopefully, these resources will give you a place to start, or

a new perspective to revamp approaches you’ve tried before. Feel free to use all of it, some of it,

or just bits and pieces that catch your eye. It is yours to shape!

Guiding Principles For Teaching Spoken Word

1. Facilitate confidence and vulnerability. If you are going to create a group of students who

are writing poetry and putting their heart and soul into their work, it is important to foster an

atmosphere of respect, trust, and safety. Having everyone at least introduce themselves and be

on a first name basis can go a long way in making people feel more comfortable sharing

themselves. In addition, when accommodating LGBTQ students, we strongly encourage that you

prompt students to share their gender pronouns if they feel comfortable doing so. This provides

support to gender questioning students and gives them the space to assert and affirm their

identity. Spoken word poetry allows students to talk about the things that are more personal than

a textbook. It gives students a space to discuss what they are working through, especially topics

that might be surrounded by a culture of shame or silence. (Divorce, gender, body image, etc.) It

creates a space for community support and camaraderie, which gives them permission to both be

vulnerable and share that vulnerability openly with the people around them.

2. Empower: Students who are convinced that they are “bad” at writing may shut off from

workshops altogether. Spoken word poetry is a perfect way to remind students that they have the

power to tell a story and contribute ideas, rather than just recieve them. By highlighting students’

ideas and creativity first before their grammar and spelling, spoken word can help students

discover that they are compelling communicators that can have control over language. Spoken

word can create an opportunity for students to fall in love with language by removing some of

the traditional barriers up front. Once someone is regularly excited about sharing their poetry,

reading and writing start to be framed as additional tools to assist them in communicating instead

of obstacles to creative expression.

2 Date & Time Co-curriculum

3. Focus on process, not product. In order for spoken word poetry to be the most effective,

(and we honestly believe this!) this art form must be something that students can only succeed at,

not something they can fail. This is a space for them to be free. Uncensored when possible.

Focus on how well they collaborate, how big the risks are that they take in their performance,

how well they take feedback, their demonstrated growth, etc.

4. Poetry does not necessarily have to be about love. Or about politics. Or about the meaning

of life. Poetry can be about anything and everything (including love, politics and life - if they so

choose). Writers (especially new writers!) tend to get nervous about writing poetry when they

think they need to be "deep" or "heavy" or "universal". Writing prompts that shoehorn students

into those kinds of topics can sometimes stifle creativity, or alienate students who aren’t ready to

write and share at such high stakes. All they really need to be is true to themselves, and be

reassured that there isn’t one way to write or perform spoken word poetry. It is important to

encourage your students to write poetry about things they care about, that they are genuinely

excited to talk about. If they are drawn to writing about big abstract topics such as politics, love

or life - push them to be as specific as possible. Don’t allow them to escape behind abstract

words and language - anchor their writing in sensory details to make it come alive.

5. Explore other poets' work as much as possible. Seeing other other examples of poetry can

help students expand their definition of what poetry is (and who is allowed to share it). Search on

youtube for examples of different styles of poetry, different types of performance, different poets

from different backgrounds. Also you can engage students in the exploration process by making

time during class for them to share poems they find. The more diverse of a group you bring in,

the more opportunities there are for students to find something they can connect with. Make sure

to make time for poets with backgrounds that have been underrepresented in the established

literary canon. To find a wide range of poets and poems, three good places to start are:

speakeasynyc, Button Poetry, and The Poetry Foundation

3 Date & Time Co-curriculum

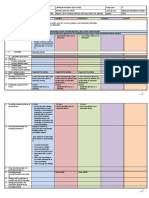

Standards Addressed

All lessons address the following Common Core Anchor Standards. These are standards

common to all grades 6-12 under Narrative Writing (CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.6.3).

Additional standards addressed can be found at the top of specific lessons.

Writing Standards:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.3.D

Use precise words and phrases, telling details, and sensory language to convey a vivid picture of the

experiences, events, setting, and/or characters.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.10

Write routinely over extended time frames (time for research, reflection, and revision) and shorter time

frames (a single sitting or a day or two) for a range of tasks, purposes, and audiences.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W3.B

Use narrative techniques, such as dialogue, pacing, and description, to develop experiences, events, and/or

characters.

Reading Standards:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.2

Determine a theme or central idea of a text and how it is conveyed through particular details; provide a

summary of the text distinct from personal opinions or judgments.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.6.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative and

connotative meanings; analyze the impact of a specific word choice on meaning and tone

Speaking and Listening Standards:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.SL.6.1

Engage effectively in a range of collaborative discussions (one-on-one, in groups, and teacher-led) with

diverse partners on grade 6 topics, texts, and issues, building on others' ideas and expressing their own

clearly.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.CCRA.L.5

Demonstrate understanding of figurative language, word relationships, and nuances in word meanings.

4 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Speaking To Ourselves, Based on “THE AUTHOR & THE AUTHOR AT 7

YEARS OLD CHOOSE A MOVIE TO WATCH”

Recommended Age: Middle School or High School

Additional Standards Addressed: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.L.6.5.A

Interpret figures of speech (e.g., personification) in context. See all standards this prompt

addresses on Page 4.

Goals: Participants will be able to interpret and use tone and temporal language to personify a

memory of their younger self in writing. They will be able to engage with their personification

through writing to reflect on the impact of media in their personal development.

Introduction (5-10 min): Ice breaker question that ties into the theme of the piece could be, “If

you could bring only one thing from your childhood to comfort you on a desert island, what

would it be?”

Read Out (5-7 min): Hand out the text of the poem, ask everyone to have a pencil in hand as we

read through the dialogue together and to mark anything they find interesting or wonder about.

Model what this might look like after a reading begins, “I am underlining this phrase because I

don’t understand why he would ask that. I am circling this word because it’s so impactful.” Ask

for one student volunteer to read part of the dialogue, whichever side they prefer, do not reveal

who is who.

Discussion (15-20 min):

Who is who? And where in the poem can we know for sure?

What movies do you recognize? Have you seen any of them? What are they about?

What might the questions the younger Phil asked reveal about him?

What does the interruption about “gender stuff” indicate about younger Phil?

What is happening during some of the moments of silence (...)?

What is similar about the things young Phil pays attention to, asks more about?

How is the last line different from younger Phil’s other questions?

What does Phil do to personify his younger self? How does he make his younger voice distinct

from his current one?

Pre-Writing (5-7 mins):

Before we start writing our own poems we’re going to do a little brainstorming.

5 Date & Time Co-curriculum

List five objects that you lost or left behind. Five things that would be laying on the floor of your

childhood room. Five things your parents wouldn’t want you to see. Five things you spent a lot

of time playing with/watching as a kid that might embarrass you now.

Now, list as many words or phrases as you can think of that your younger self may have used

that you wouldn’t use anymore.

Prompt (15-20 mins): Write a poem having a conversation with your childhood self using one

or some of the items from your lists. It can be in the form of a scene, like Phil’s poem, or a letter

to or from your younger self.

As you focus on a few of the items, start to consider these questions:

What was your younger self’s first impression of this item?

What questions would your younger self-ask about them?

How would you explain your relationship to these items in terms your younger self might

understand?

What might you younger self not understand?

6 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Poems that are the Sum of Two Stories, Based on “Succulent”

Recommended Age: High School

Additional Standards Addressed: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.2.D

Use precise language, domain-specific vocabulary, and techniques such as metaphor, simile, and

analogy to manage the complexity of the topic. See all standards this prompt addresses on Page

4.

Goals: Participants will be able to structure a poem around a central analogy and use descriptive

language to make that analogy apparent to their reader.

Introduction (5-10 min): Possible question: “If your hands had to be replaced with a hand-sized

version of an animal, what animal would you replace them with?”

Read out (5 min): Have the poem read twice, once by a student volunteer and once by the

facilitator. Ask everyone to have a pencil in hand during both readings and to mark any strong

lines or imagery they notice.

Discussion (15 min):

What is this poem about?

What role does the succulent play in the poem? What does is represent? How do you know?

How is the idea of growth explored in the poem? What is the speaker growing?

Who is the voice coming from the other room? What does that show about the speaker?

What imagery stuck out to you in the poem? How does it relate to the poem’s deeper meaning?

When does the narrative of the poem change or “turn”? How does it feel to read that?

Where is the poem literal? Where is it figurative?

What would happen if we separated the two stories? What meanings, messages, and images

would we lose from the poem? Would the voice in the end have the same meaning?

If we were to write a one-line analogy based on this poem, what would it be?

Pre-writing (10 mins): Pass out some index cards. Ask everyone to fold it down it’s length, and

then for everyone to write a mundane, or unassuming task on the top half (ie. mowing the lawn,

cleaning dishes, dropping an ice cream cone or something small you noticed today) Fold the line

back so you can’t see the first image, and pass your index card twice to the left. On the bottom

half of the index card write down a pivotal or dramatic change someone might experience (ie.

moving away, going through a break up, etc) then pass the index card twice to your left again.

Now let's unfold our index card, and turn them into an analogy by adding “is like (a/n)”

7 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Does anyone want to share the analogy they have on their index card? Silly or surprising? Now

we’re going to take a second to revise our analogies, change the first or second half with either a

image your wrote or heard earlier in the space that you feel might better resonate with the other

half of the analogy.

Prompt (15 mins): Write a poem that explores the analogy on your index card, or feel free to

modify or make a new one that you feel is more powerful or more specific to your experiences or

personal changes.

As you write, consider:

How does the smaller, seemingly less significant moment have parallels with the larger moment?

What advice or guidance, good or bad, might the mundane moment have for your bigger change?

How can you use imagery or descriptive language to make your analogy apparent to your reader?

Alternative Set Up: Do the same as above, although rather than using an index card and passing

the cards, simply have students generate their own lists of unassuming tasks and pivotal changes.

Then, have them choose an item from each of their own lists that they think would make an

intriguing pair, and explore their analogy.

8 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Personifying Our Objects, Based on “Numbers Man”

Recommended Age: High School

Additional Standards Addressed:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.11-12.2.D

Use precise language, domain-specific vocabulary, and techniques such as metaphor, simile, and

analogy to manage the complexity of the topic. See all standards this prompt addresses on Page

4.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.7.5

Analyze how a drama's or poem's form or structure (e.g., soliloquy, sonnet) contributes to its

meaning. See all standards this prompt addresses on Page 4.

Goals: Participants will be able to write a soliloquy from the perspective of a personified object

that they have a close relationship to.

Introduction (5-10 min): A suggestion that ties into the poem’s themes: “If you had to become

an object you use regularly for a day, what object would you be?” (If cell phone seems like too

obvious an answer, see if students can push beyond that!)

Read Out (5-7 min): Have the poem read twice, once by a student volunteer and once by the

facilitator or Phil's performance in addition. Encourage everyone to have a pencil in hand during

both readings and to mark any lines or images they find interesting, surprising, or that they

wonder about.

Discussion (15-20 min):

Does anyone know what a soliloquy is?

Do you think Numbers Man is a soliloquy? Why or why not?

What does it mean for someone to be a “numbers man”?

How would you describe the speaker in this poem? Which aspects of the speaker betray its

identity as a “numbers man?

How would you characterize the relationship between the numbers man and its owner?

How does Phil Kaye develop a sense of intimacy between the owner and the numbers man?

What details or lines tell us that the speaker isn’t human?

What is significant about a “numbers man” learning how to draw?

What’s different about the last stanza? Does it surprise you?

Prompt and Pre-Writing (15-20 mins):

9 Date & Time Co-curriculum

List 5 objects you’ve broken but held onto, 5 guilty pleasures or throwback songs, movies etc, 5

professions you wouldn’t want to be in, 5 objects you have the newest version of.

Choose an item from your list that might feel left behind by you and write a soliloquy from its

perspective. Write “I am a ____” and fill in the blank with a profession or a role the object

might call itself. For example, a wristwatch might say “I am a clingy mathematician”

Would anyone like to share their first line before we start?

As you write, consider:

What might that object miss about you?

What is a shared memory you might have found trivial, but that meant a lot or something

different to the object?

What embarrassing dirt does it have on you? What could it divulge about you if it could speak?

How might the object interpret your absence? How might it project that on to humanity in

general?

Reread the last stanza of Numbers Man. How could you add a turn of narrative in your poem to

add depth or interest?

10 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Memories and Place, Based on “Camaro”

Recommended Age: High School

Additional Standards Addressed: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.7.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative and

connotative meanings; analyze the impact of rhymes and other repetitions of sounds (e.g.,

alliteration) on a specific verse or stanza of a poem or section of a story or drama. See all

standards this prompt addresses on Page 4.

Goals: Participants will be able to write a narrative poem using repetition to examine a memory

through the perspective of a past self and present self.

Introductions (5 mins): Possible question tied to the themes of the poem: “If you suddenly had

an extra $100 dollars to spend on something unimportant, what would you spend it on?”

Low Risk Writing Exercise (5 mins): To get warmed up we’re gonna do a free write. For the

next five minutes, we’re going to write continuously without stopping. What you write down

does not have to be amazing or even coherent - there are no expectations except that your pen is

moving. If you’re having trouble getting something on the page, one strategy is to write ‘nothing,

nothing, nothing,’ until something pops up, though I also recommend establishing a different

word in place of nothing like ‘orange orange orange.’ Feel free to start the free write on what

you’d spend 100 dollars on.

Follow Up Discussion (5 mins): What challenged or surprised you while writing? Does anyone

want to share a piece of what they wrote?

Read Out (5 mins): Now we’re going to switch gears and read a poem. While listening and

reading along with the poem, pay attention to where there is repetition, and mark lines that strike

you or surprise you. (We recommend one reading by a student or facilitator, and then hearing

Phil Kaye's performance of the poem)

Discussion (10 mins):

What are some lines that struck you or surprised you? Why?

Where does this poem repeat itself? What meaning does the repetition add to the poem?

How many stories are in the poem? What are they? How are they connected together?

What does the speaker mean when he says he is “trespassing” in stanza fifteen?

How does the tone change from the beginning of the poem to the end?

How is the first time the Speaker says “I remember” different from the last?

11 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Pre-writing (5 mins): Today we’re going to write a poem that tries to return back to a

conversation or a memory you felt you didn’t say everything you wish you could, and how that

place or memory has changed in meaning for you over time.

First, list five physical landmarks or specific places that are charged with lots of memories.

Choose one of those places and list five important or difficult conversations you’ve had in that

place over time. List five questions you feel like you don’t have the answers to, related to those

memories or not. List five phrases that have re-occurred in your life, such as family sayings or

personal mantras.

Prompt (10-15 mins): Select a conversation that came up for you during your pre-write. Write a

poem about what went unsaid in the memory and perhaps how that memory has changed over

time.

If there are several related conversation that happened over time, free to jump between different

times in the same location, or between different specific conversations with the same person. If

you’d like, use a question or the phrase that has stuck with you as a way to transition in between

these different moments, similar to “Camaro”.

As you write, consider:

What did you actually do or say? How did you feel about it at the time?

How do you feel about what you said now?

What has happened in your life between then and now?

What do you wish you could have said in that moment, knowing every you do now?

12 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Poems that Borrow Language Based on “On Starting”

All Ages, particularly younger groups

Additional Standards Addressed:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.5.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative

language such as metaphors and similes. See all standards this prompt addresses on Page 4.

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.6.5

Analyze how a particular sentence, chapter, scene, or stanza fits into the overall structure of a

text and contributes to the development of the theme, setting, or plot. See all standards this

prompt addresses on Page 4.

Goals: Participants will be able to use a central metaphor to describe an abstract concept

including concrete sensory details.

Introduction (5 mins): Possible introductory question: “What was the last thing you borrowed?”

Pre-Read Out Discussion (5-7 mins): Can anyone tell me what a fish looks like? Write up a list

of characteristics students mention on a board. Now can anyone tell me what an idea looks like?

Can you describe how you find ideas in your own mind? Put any associations or near

characteristics people mention on the board. We're going to read a poem someone wrote

describing what finding an idea looks and feels like using a metaphor.

Read Out (3-5 mins): One reading by a student, one reading by the facilitator

Discussion (10-15 mins):

What is a metaphor? What is the metaphor of this poem?

What would it be like to go fishing with your bare hands?

How might coming up with an idea be similar to fishing with just your hands?

Where might the speaker be standing in this poem? What location? How do we know?

What language is used to describe what an idea looks like? (squirming gift, wide-eyed & fat)

What might it mean for an idea be “stunned by its own reflection”?

How does a fish feel out of water? How does the speaker suggest an idea “out of water” feels?

Pre-Writing and Prompt (10-15 mins): Now we’re going to write poems about something

that's hard to describe, like an idea, using language from something we can describe with our

hands or our senses. First let’s list 5 things that are abstract, like ideas, problems, love, jealousy,

friendship etc. Now, let's list a few activities we know we can describe with our senses, like

13 Date & Time Co-curriculum

fishing, cleaning a bathroom, riding a bike etc. Now, set up this sentence: “____ is ____”. Fill by

choose one thing from each list- try a few different combinations until you find something that

really jumps out to you. (i.e. friendship is cleaning a bathroom / friendship is bike riding.) Does

anyone want to share their metaphor?

Now, describe what the abstract concept looks and feels like using your concrete activity. Reread

On Starting if you need inspiration.

As you write, consider:

How are you using sight, sound, touch, and taste to make your experience come alive for your

reader?

Are you hoping to convey a universal experience or are you expressing something personal to

you?

14 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Turning People into Places, Based on “My Grandmother’s Ballroom”

Recommended Age: Middle School or High School

Additional Standards Addressed: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.5.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative

language such as metaphors and similes. See all standards this prompt addresses on Page 4.

Goals: Participants will be able to write a poem based on a central metaphor comparing a

familiar person with a location.

Introduction (5 mins): Possible question: if you suddenly turned into a fruit, what would you be

an why?

Read out (5-7 mins): Today we’re going to read a poem someone wrote about their

grandmother, but in way that you wouldn’t typically describe a person. One reading from a

student or facilitator, and then one reading from Phil Kaye's performance.

Discussion (10-15 mins):

What is the speaker describing in this poem?

What is the initial tone of the poem?

How does the tone of the poem change throughout?

Why might Kaye have chosen a ballroom as the metaphor for his grandmother’s mind?

What does the memory of the strawberries show about the speaker’s grandmother at the

beginning of the poem? What does it show about her at the end?

How might this poem be different without the ballroom analogy? How would it have felt to read?

How might it have felt to write this poem?

Prewriting (5 mins): List 5 people from any part of your life, 5 important or difficult

experiences you’ve dealt with, 5 general recognizable locations (ie: swimming pool, roller rink,

front porch), 5 natural features (ie: valley, waterfall, etc)

Prompt (10-15 mins): Write a poem describing someone in your life as though they are a place,

choose a spot from you list and think about what might be in that space, who would be there, and

what they might be doing. How could you make those actions and things represent memories or

characteristics of your person? If you need a place to start, write down a metaphor like, “My

brother is an empty pool” or “My best friend is a rainforest” and expand the world of your poem

from there.

15 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Repetition as Theme, Based on “Appreciation Meditation”

Recommended Age: Middle School or High School

Additional Standards Addressed: CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.7.4

Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including figurative and

connotative meanings; analyze the impact of rhymes and other repetitions of sounds (e.g.,

alliteration) on a specific verse or stanza of a poem or section of a story or drama. See all

standards this prompt addresses on Page 4.

Goals: Participants will be able to write a poem exploring a central theme, using line repetition

and sensory language.

Introduction: Possible question: What is the most useless superpower you can imagine? (i.e.

can look at any color in nature and know the exact crayola crayon color match).

Read out: Today we’re going to read a poem exploring gratitude. As we read, underline or circle

anything that stands out to you. On second read, notice any reactions you have to the repetition

in the poem. Facilitator reads then invites students to read the line, “Whoa, be thankful” with

them each time it repeats.

Discussion:

How does repetition add to this poem? Do you like it?

Why does the speaker repeat this line?

Where do you notice sensory language in the poem?

How would the poem be different without sensory language?

How does the speaker use sensory language to invoke emotion?

Where does the poem turn? How does repetition indicate a turn in the poem?

Other than thankfulness, what other themes do you notice? (nature, body)

Prewriting: Complete the following sentence starters in as many ways as you can:

Whoa, be thankful for

I am nothing without

I would never

Oh, I love the

My anger rises when

We were us until

16 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Prompt: Write a poem that repeats one of the starters above or one of your own creation in each

stanza. As you write, see if you can develop a theme and narrow your stanzas to that theme,

similar to how Kaye has done in “The Appreciation Meditation” by focusing in on thankfulness

for elements of nature and the body.

As you write, consider:

How can you add sensory language to make your description more focused or emotional for your

reader?

Notice places where you have written a broad idea instead of a description, can you identify

sensory elements or memories tied to that idea?

17 Date & Time Co-curriculum

General Workshop Guide / Sample structure

(5-10 min )Introductions/Ice Breaker: Going around the room and having everyone say their

name, their preferred gender pronouns, and answer a low stakes icebreaker can go a long way in

setting a comfortable, communal environment, especially if the educator participates as well

(though not necessarily first). An example of a low stakes ice breaker question is, “if you had to

turn your hands into animals what animals would you replace them with?” Questions like these

allow everyone to get silly or creative, without the pressure to make it personal or profound. If

you’re feeling particularly clever, you can utilize the ice breaker question as a form of

pre-writing by relating it to themes in the poem or prompt you’re facilitating. In this way you can

have students begin their writing process without realizing the idea they’re coming up with at the

beginning of the workshop can be useful for what they’ll end up writing. For example, if you

have a workshop about writing odes, your ice breaker could be, “what is an embarrassing thing

from your childhood that you secretly love?”

(5-7 min) Read Out: Present the poem for the workshop by handing out the poem, accompanied

with either a video of the poet reading their poem, or a student volunteer to read. Make sure as

the facilitator you read it once again so that the room can hear what the poem sounds likes in

multiple voices. If there is a version of the poem with the author reading it themselves, that is

often helpful to show. Encourage everyone to have a pencil in hand and ready to mark up the

page during these readings. Tell them they can mark the poem however they wish, but some

suggestions are: lines that surprised them, lines they wonder about, and lines that resonate with

them.

(15-20 min) Discussion: Making the space for students to share and connect with one another

about what they noticed in the piece can be a powerful practice. It gives them the space to choose

where the conversation begins, and most importantly the moments that struck them. In our

approach to discussion, we find that following our student’s curiosity by mirroring and

reiterating their findings can be an empowering driving force for active discourse. Your

questions that move their curiosity and energy forward should encourage them to interrogate the

inner workings of the poem - going into the how and why these lines are striking. By following

student interest and pushing it further, the discussion can lead organically to students discovering

for themselves the tools the poet uses to convey their message. Have a handful of pre-written

questions that specifically interrogate the tools the poet is using and highlight the learning point

for crafting. However, instead of asking questions in a strict order, ask them as student interest

moves toward a moment from the poem you wish to highlight and examine more closely. Take

into consideration how well you know the participants, their level of experience with poetry, and

18 Date & Time Co-curriculum

other factors of the group identity while writing your questions to look for the best angle for

engagement.

(5 min or less) Pre-writing and Introducing the Prompt: The prompt should ask an engaging,

thoughtful, question that's hard to answer (an “ill-defined problem” in educational psych terms).

It should exercise one or more of the tools/forms/strategies used in the mentor text. Pre-writing

exercises can be a great way to loosen up and quiet the apprehensive writing voice inside our

head while also getting a ton of ideas on the page to choose from. It also helps break up tackling

the problem of the prompt into more manageable steps. Pre-writing is the cardio of writing,

getting us warmed up to use the tools and techniques the prompt will ask us to exercise. One

example of a pre-writing exercise is list making. Come up with a few list categories based on

themes or images used in the poem and ask your students to write 3-5 things for each category.

Go one category at a time, checking the room to see if most people have five items on their list

before moving on. The most important thing to make clear to your students about their lists is

that they’re made to be answered quickly and off the top of their heads, without the pressure of

having to come up with the idea for the prompt that has to work. It’s after the lists are made that

the writers should survey their massive stock of words, ideas, or phrases, looking for the ones

that jump out to them to fuel a response to the prompt.

(10-20 mins) Writing: During the writing time, around the 10 or 15-minute mark, take a look

around the room to gauge how far everyone is generally in their poem. Make sure you never end

the writing segment unannounced, give three or five minutes warnings, ask if people feel they

need a few minutes, etc. Not every person has to have their poems finished in the allotted time,

you should emphasize that the purpose of the workshop is not to create a final product in under

an hour, but to get started on our first drafts together.

(Remaining Time) Share Out: An opportunity to share at the end of a workshop can do a lot for

the lesson as a whole. It can build confidence for students, provide them with creative feedback,

showcase a variety of poems, voices, and directions taken from the same prompt, provide

inspiration or solutions for those who may have struggled through the prompt, and offers a low

stakes space for new poets to get experience performing. Make sure you taking time to prioritize

all voices, at all levels of experience, not just those who seem to take to the prompts more

naturally and are most excited to share. Try to encourage those who seem more hesitant to read

just a piece or a few lines from their poems, and emphasize that everyone is only expected to

have a draft, not a final product.

19 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Tips for Including All Learners in Workshops

Universal Design for Learning strategies for removing barriers to content for all students

Any educator knows that workshop-style lessons can be incredibly fruitful for creativity and skill

acquisition. They are also full of barriers for students. The strategies below use Universal Design

for Learning (UDL) principles to imagine ways you could open up the lessons in this curriculum

to be more accessible to all students. These may be particularly helpful for students who speak

multiple languages, are managing language or print-based learning difficulties, are emerging

readers, or live on the autism spectrum.

(5-10 min)Introductions/Ice Breaker:

- Students share their ice breaker with a partner first, then can choose to share their answer

or their partner’s with the group

- Students are welcomed to write and share in their home language for the session, even if

the facilitator will not understand

(5-7 min) Read Out:

- Poem always read aloud and given in print

- Teacher gives listening focus for read-out such as, “as I’m reading, listen for places

where there is repetition”

- If possible, provide the option of translated texts or text read in a home language by a

peer or staff

(15-20 min) Discussion:

- All discussion questions posted and read aloud

- Students may choose to answer discussion questions with the whole group or with an

assigned partner/small group

- Students are given time to write individually or talk about their answers with a partner to

discussion questions before sharing out to the whole group

(5 min or less) Pre-writing and Introducing the Prompt:

- Students may choose to work in a small group with the teacher or with an assigned

partner during pre-write while others work independently

- Teacher may provide pre-writes for students that struggle with idea generation

(10-20 mins) Writing:

- Print and audio copies of mentor poem are available during work time

- Poems with similar target-skill or theme are also available during work time

20 Date & Time Co-curriculum

- Students may co-write a poem with a small group and teacher before trying their own

- Teacher may provide sentence starters or menu of topics related to the prompt

(Remaining Time) Share Out:

- Students may share with whole group, trusted peer, or teacher in the building

- Students may record their poem on their phone and share the video

21 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Influential Texts

For White Folks Who Teach in the Hood… and the Rest of Ya’ll Too

By Dr. Christopher Emdin

Pedagogy of the Oppressed

By Paulo Freire

Workshopping the Workshop, Professional Development Session

By Geoff Kagan-Trenchard, Jon Sands, & Mahogany L. Browne

The Heart of a Teacher, Identity and Integrity in Teaching

By Parker J. Palmer

Universal Design for Learning

http://www.cast.org/our-work/about-udl.html#.W7v5ohNKjBI

22 Date & Time Co-curriculum

Contact Us

Otto Vock

web: http://ottovock.com/

contact: msg.otto.vock@gmail.com

instagram: @otton.of.feelings

facebook: facebook.com/OttoVocksPoetry/

Phil Kaye

web: www.philkaye.com

contact: info@philkaye.com

instagram: @peekaye

facebook: facebook.com/philkaye

Molly Nestor

contact: melindanestor@gmail.com

instagram: @mknest

Sarah Kay

web: www.kaysarahsera.com/

contact: emailsarahkay@gmail.com

twitter: https://twitter.com/kaysarahsera

facebook: facebook.com/kaysarahsera/

Jeremy Geddes - Cover Art

web: http://www.jeremygeddesart.com/

instagram: @jeremyispainting

Web: www.projectvoice.co/

Contact: booking@projectvoice.co

Instagram: @projvoice

23 Date & Time Co-curriculum

You might also like

- CELPIP - Writing Task 1 & 2 - Sample AnswersDocument26 pagesCELPIP - Writing Task 1 & 2 - Sample Answersx6q6ky4qdt100% (2)

- Barren Grounds Novel Study ELAL 6 COMPLETEDocument113 pagesBarren Grounds Novel Study ELAL 6 COMPLETEslsenholtNo ratings yet

- Lei de Bases Da Educação (ENG) - Timor-LesteDocument36 pagesLei de Bases Da Educação (ENG) - Timor-LesteEmbaixadora de Boa Vontade para os Assuntos da EducaçãoNo ratings yet

- Exam View Time ZonesDocument2 pagesExam View Time ZonesHitoshi Sukari50% (4)

- Week 9 DLL (Information Literacy)Document3 pagesWeek 9 DLL (Information Literacy)NestorJepolanCapiñaNo ratings yet

- Collins - GermanDocument163 pagesCollins - GermanGabriela Diaconu100% (6)

- Unit Plan Poetry Grade 9 EnglishDocument28 pagesUnit Plan Poetry Grade 9 Englishapi-465927221No ratings yet

- Ela 7 - Poetry Unit PlanDocument14 pagesEla 7 - Poetry Unit Planapi-301884082No ratings yet

- Integrated Lesson Plan Mod 4Document9 pagesIntegrated Lesson Plan Mod 4api-520773681No ratings yet

- AU19 English 1101Document9 pagesAU19 English 1101Jacinta YandersNo ratings yet

- Unit 4: Poetry UnitDocument7 pagesUnit 4: Poetry UnitNeha ShahNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1Document28 pagesLesson 1Roushiell LondonNo ratings yet

- Literacy Module 5 OgdimalantaDocument6 pagesLiteracy Module 5 OgdimalantaSunshine ArceoNo ratings yet

- Approaches in Teaching LiteratureDocument38 pagesApproaches in Teaching LiteratureKai SubidoNo ratings yet

- Teaching Prose and Dramatic ProseDocument20 pagesTeaching Prose and Dramatic ProseCarina Margallo Celaje100% (4)

- Lecture 2Document39 pagesLecture 2JeremiasNo ratings yet

- 6th Grade Language ArtsDocument11 pages6th Grade Language ArtsKracel AvelinoNo ratings yet

- A Functional Approach To LanguageDocument7 pagesA Functional Approach To Languageカアンドレス100% (2)

- Name: Heterae C. Dairo: Teaching-LiteratureDocument3 pagesName: Heterae C. Dairo: Teaching-LiteratureDairo Heterae C.No ratings yet

- Melanie Burchard TE 848 Final Project: Writing Portfolio DraftDocument19 pagesMelanie Burchard TE 848 Final Project: Writing Portfolio Draftapi-299395976No ratings yet

- Literature AssessmentDocument10 pagesLiterature AssessmentBryan Robert Maleniza BrosulaNo ratings yet

- Teaching of ProseDocument6 pagesTeaching of ProseJeah BinayaoNo ratings yet

- W6. Principles and Practices of Teaching LiteratureDocument13 pagesW6. Principles and Practices of Teaching LiteratureAnna Lou S. Espino100% (2)

- U7 Educ 5271 WaDocument9 pagesU7 Educ 5271 WaTomNo ratings yet

- Critical Book Review: LiteratureDocument11 pagesCritical Book Review: LiteratureFH UnudAde Clara HutapeaReguler PagiNo ratings yet

- Approaches in Teaching Literature Classes Information-Based ApproachDocument2 pagesApproaches in Teaching Literature Classes Information-Based ApproachLezil O. CalutanNo ratings yet

- Module 14 Teaching WritingDocument12 pagesModule 14 Teaching WritingJana VenterNo ratings yet

- MODULE 1 in Teaching EnglishDocument7 pagesMODULE 1 in Teaching EnglishAnalisa SalangusteNo ratings yet

- The Writer's Workshop: Imitating Your Way to Better WritingFrom EverandThe Writer's Workshop: Imitating Your Way to Better WritingNo ratings yet

- Real Deal - Part IDocument57 pagesReal Deal - Part Iapi-271057680No ratings yet

- English Unit Plan - Grade 6Document18 pagesEnglish Unit Plan - Grade 6api-490524431No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan For Patrick Henry Speech To The Virginia ConventionDocument3 pagesLesson Plan For Patrick Henry Speech To The Virginia ConventionLynn Green FoutsNo ratings yet

- Tips To Teach LiteratureDocument5 pagesTips To Teach LiteraturerabailrattarNo ratings yet

- ENGL 1302 SP 2014 Composition II SyllabusDocument9 pagesENGL 1302 SP 2014 Composition II SyllabusKatt Blackwell-StarnesNo ratings yet

- Informed Arguments A Guide To Writing and ResearchDocument198 pagesInformed Arguments A Guide To Writing and ResearchCheryl100% (1)

- Ci 403 Unit Plan Lesson 1Document12 pagesCi 403 Unit Plan Lesson 1api-302766620No ratings yet

- Common Core Aligned Lesson Plan Template Subject(s) : - Grade: - Teacher(s) : - SchoolDocument2 pagesCommon Core Aligned Lesson Plan Template Subject(s) : - Grade: - Teacher(s) : - Schoolapi-296640646No ratings yet

- Flores Ce Du 517 Final 121323Document7 pagesFlores Ce Du 517 Final 121323Cynthia Flores-LombayNo ratings yet

- Teaching LiteratureDocument11 pagesTeaching Literaturesha100% (2)

- English Language Arts Travel Learning TasksDocument5 pagesEnglish Language Arts Travel Learning Tasksapi-181927398No ratings yet

- Academic Conversations Classroom Talk That Fosters Critical Thinking and Content Understandings by Crawford, MarieZwiers, JeffDocument280 pagesAcademic Conversations Classroom Talk That Fosters Critical Thinking and Content Understandings by Crawford, MarieZwiers, Jeffwacwic wydadNo ratings yet

- Teaching Writing in Interactive EnglishDocument29 pagesTeaching Writing in Interactive EnglishjhoeyaxNo ratings yet

- 6th Grade Assignment Term 3Document11 pages6th Grade Assignment Term 3api-237229446No ratings yet

- 2021-22 Edci Lesson PlanDocument9 pages2021-22 Edci Lesson Planapi-743671953No ratings yet

- GR 6 Making Connections Lessons 1-3 2Document7 pagesGR 6 Making Connections Lessons 1-3 2Sheila Marie De VeraNo ratings yet

- MS MemoirDocument72 pagesMS MemoirAllwe Maullana100% (3)

- Lesson PlanDocument16 pagesLesson Planapi-507843140No ratings yet

- Text StructDocument43 pagesText StructDinno JorgeNo ratings yet

- Notes For The T Notes For The T Notes For The T Notes For The T Notes For The Teacher Eacher Eacher Eacher EacherDocument16 pagesNotes For The T Notes For The T Notes For The T Notes For The T Notes For The Teacher Eacher Eacher Eacher Eacherashu tyagiNo ratings yet

- English BookDocument180 pagesEnglish Bookkimcartoon.officialNo ratings yet

- Pre-Observation DR Mulhall 2015Document7 pagesPre-Observation DR Mulhall 2015api-279291777No ratings yet

- PCM Unit Short Story WritingDocument31 pagesPCM Unit Short Story Writingapi-253146124No ratings yet

- Edu 542 Lessonmodel 2Document8 pagesEdu 542 Lessonmodel 2api-347962298No ratings yet

- Beyond "Is This OK?": High School Writers Building Understandings of GenreDocument10 pagesBeyond "Is This OK?": High School Writers Building Understandings of Genreapi-297629759No ratings yet

- Haiku and Cinquain Lesson Plan - OGER Landscape OrientationDocument5 pagesHaiku and Cinquain Lesson Plan - OGER Landscape OrientationSonia Caliso100% (2)

- ED505 Course Syllabus, Irby, Summer 2009Document7 pagesED505 Course Syllabus, Irby, Summer 2009mclaughaNo ratings yet

- Itl 520 Learning MapDocument7 pagesItl 520 Learning Mapapi-535727969No ratings yet

- Unlocking the Poem: A Guide to Discovering Meaning through Understanding and AnalysisFrom EverandUnlocking the Poem: A Guide to Discovering Meaning through Understanding and AnalysisNo ratings yet

- Family Memoir LessonDocument14 pagesFamily Memoir Lessonapi-236084849100% (1)

- Beehive - Eng Textbook (NCERT)Document121 pagesBeehive - Eng Textbook (NCERT)Gitanjali NayakNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 2 Ci 403Document12 pagesLesson Plan 2 Ci 403api-311232043No ratings yet

- Project Planning Form Meth 4 - KopieDocument14 pagesProject Planning Form Meth 4 - Kopieapi-734164891No ratings yet

- Ya Lit Unit Plan WrevisionsDocument17 pagesYa Lit Unit Plan Wrevisionsapi-224612708No ratings yet

- EDU 542 Lesson Plan Format Macbeth: Constructivist ModelDocument7 pagesEDU 542 Lesson Plan Format Macbeth: Constructivist Modelapi-558491172No ratings yet

- Usaid Schools ProjectDocument25 pagesUsaid Schools ProjectDennis ItumbiNo ratings yet

- Ms Lesson Plan - Lesson 3 Value WaterDocument15 pagesMs Lesson Plan - Lesson 3 Value WaterApril Mae ArcayaNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Spring 2018 Yoruba 7Document4 pagesSyllabus Spring 2018 Yoruba 7api-392906636No ratings yet

- Social Studies Simulation Teaching Presentation Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesSocial Studies Simulation Teaching Presentation Lesson Planapi-241322150100% (1)

- Trends and Issues (Obtl)Document14 pagesTrends and Issues (Obtl)Jonathan Luke MallariNo ratings yet

- QuestionaireDocument5 pagesQuestionaireMohsan SheikhNo ratings yet

- Science 4 Catch Up FridayDocument6 pagesScience 4 Catch Up Fridayjessyl cruzNo ratings yet

- How To Apply For PHD in NorwayDocument2 pagesHow To Apply For PHD in NorwayMohsen AnvaariNo ratings yet

- To de Aulas MICROLINS Book 1Document3 pagesTo de Aulas MICROLINS Book 1Arlete RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Form R1 - 2 Report On Family StatusDocument1 pageForm R1 - 2 Report On Family StatusOmakoi MalangNo ratings yet

- PhysicalEducation Teachingandlearning PDFDocument66 pagesPhysicalEducation Teachingandlearning PDFChoirulNo ratings yet

- A Profile of Bullying at School: Educational Leadership, March 2003Document8 pagesA Profile of Bullying at School: Educational Leadership, March 2003johnknown1No ratings yet

- Education Act of 1982Document18 pagesEducation Act of 1982Joellen Mae LayloNo ratings yet

- Olweus (1997) Bully-Victim Problems in School PDFDocument16 pagesOlweus (1997) Bully-Victim Problems in School PDFSara Alejandra EspinozaNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Dates School / College / Training Body Certification(s)Document8 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Dates School / College / Training Body Certification(s)Pancuss Abdul-Fataw PancussNo ratings yet

- Case Study IepDocument5 pagesCase Study Iepapi-168258709No ratings yet

- EF WORK CHINA All High Flyers On Stage Lesson PlansDocument128 pagesEF WORK CHINA All High Flyers On Stage Lesson Planslibrary364No ratings yet

- NDC 2010 Debater TabsDocument28 pagesNDC 2010 Debater TabsKristian CaumeranNo ratings yet

- Cocker's Decimal ArithmetickDocument1 pageCocker's Decimal ArithmetickAnonymous vcdqCTtS9No ratings yet

- Melody of DharmaNo4Document60 pagesMelody of DharmaNo4chen350No ratings yet

- M.ed Dissertation In Urdu ایم ایڈ کامقالہ MD AbsharuddinDocument81 pagesM.ed Dissertation In Urdu ایم ایڈ کامقالہ MD AbsharuddinMd Absharuddin ChishtiNo ratings yet

- Changes in The Curriculum Adaptation Skills of Teachers A 2024 Teaching andDocument13 pagesChanges in The Curriculum Adaptation Skills of Teachers A 2024 Teaching andalbertus tuhu100% (1)

- Joan Resume 2013-MsuDocument4 pagesJoan Resume 2013-Msuapi-132951007No ratings yet

- LESSON PLAN FOR Past TenseDocument12 pagesLESSON PLAN FOR Past TensehezrinNo ratings yet

- Social Science ExhibitionDocument14 pagesSocial Science ExhibitionRavindra RaiNo ratings yet