2013 - Bhutta - Lancet - Interventions

2013 - Bhutta - Lancet - Interventions

Uploaded by

nomdeplumCopyright:

Available Formats

2013 - Bhutta - Lancet - Interventions

2013 - Bhutta - Lancet - Interventions

Uploaded by

nomdeplumCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

2013 - Bhutta - Lancet - Interventions

2013 - Bhutta - Lancet - Interventions

Uploaded by

nomdeplumCopyright:

Available Formats

Series

Childhood Pneumonia and Diarrhoea 2

Interventions to address deaths from childhood pneumonia

and diarrhoea equitably: what works and at what cost?

Zulfiqar A Bhutta, Jai K Das, Neff Walker, Arjumand Rizvi, Harry Campbell, Igor Rudan, Robert E Black, for The Lancet Diarrhoea and Pneumonia

Interventions Study Group*

Global mortality in children younger than 5 years has fallen substantially in the past two decades from more than Lancet 2013; 381: 1417–29

12 million in 1990, to 6·9 million in 2011, but progress is inconsistent between countries. Pneumonia and diarrhoea are Published Online

the two leading causes of death in this age group and have overlapping risk factors. Several interventions can effectively April 12, 2013

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

address these problems, but are not available to those in need. We systematically reviewed evidence showing the

S0140-6736(13)60648-0

effectiveness of various potential preventive and therapeutic interventions against childhood diarrhoea and pneumonia,

See Comment page 1335

and relevant delivery strategies. We used the Lives Saved Tool model to assess the effect on mortality when these

This is the second in a Series of

interventions are applied. We estimate that if implemented at present annual rates of increase in each of the 75 Countdown four papers about childhood

countries, these interventions and packages of care could save 54% of diarrhoea and 51% of pneumonia deaths by 2025 pneumonia and diarrhoea

at a cost of US$3·8 billion. However, if coverage of these key evidence-based interventions were scaled up to at least 80%, *Members listed at end of paper

and that for immunisations to at least 90%, 95% of diarrhoea and 67% of pneumonia deaths in children younger than Division of Woman and Child

5 years could be eliminated by 2025 at a cost of $6·715 billion. New delivery platforms could promote equitable access Health, Aga Khan University,

and community platforms are important catalysts in this respect. Furthermore, several of these interventions could Karachi, Pakistan

(Prof Z A Bhutta PhD,

reduce morbidity and overall burden of disease, with possible benefits for developmental outcomes.

J K Das MBA, A Rizvi MSc);

Bloomberg School of Public

Introduction poverty, undernutrition, poor hygiene, and deprived home Health, Johns Hopkins

Although global mortality in children younger than environments making children more likely to develop University, Baltimore, MD, USA

(Prof Z A Bhutta, N Walker MPH,

5 years has substantially reduced in the past two decades these diseases. Improvements in socioeconomic develop- Prof R E Black MD); and Centre

from more than 12 million deaths in 1990, to 6·9 million ment with corresponding increases in maternal education, for Population Health Sciences,

in 2011,1 improvements have been inconsistent world- falling fertility rates, and improved living conditions University of Edinburgh Medical

wide. Whereas some countries and regions have reduced (with reduced crowding) are important contributors to School, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK

child mortality by more than half,2 progress in others has

been much slower. Half of all deaths worldwide in

children younger than 5 years are concentrated in only Key messages

five countries: India, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of • Worldwide, pneumonia and diarrhoeal diseases are the two major killers of children

the Congo, Pakistan, and China.1 In the past decade, the younger than 5 years

number of child deaths decreased by 2 million worldwide, • Each year, 1·3 million children die from pneumonia and 700 000 from diarrhoea

with reductions in deaths due to pneumonia and • Preventive and therapeutic interventions exist that could have a role in reducing the

diarrhoea contributing to 40% of the overall reduction.3 morbidity and mortality burden due to diarrhoea and pneumonia, especially in children

Notwithstanding this success, pneumonia diseases still younger than 5 years

account for 1·3 million deaths and diarrhoeal diseases for • Few interventions with wide range of outcomes have been assessed at a sufficient scale

0·7 million deaths, and both are major causes of post- • Interventions with maximum effect include breastfeeding, oral rehydration solution, and

neonatal child deaths.2,3 Pneumonia is the largest cause of community case management

child deaths worldwide. Corresponding reductions in • Despite persistent burden, childhood diarrhoea and pneumonia deaths are avoidable and

burden of disease and morbidity have been much slower 15 interventions delivered at scale can prevent most of these avoidable deaths

than those for global child mortality. Incidence of • Estimates modelled with the Lives Saved Tool show that if the interventions are scaled up

diarrhoea has fallen from 3·4 episodes to 2·9 episodes by 80% in the 75 Countdown countries, they could save 95% of diarrhoeal and 67% of

per child-year, and that of pneumonia from 0·29 episodes pneumonia deaths in children younger than 5 years by 2025

to 0·23 episodes per child-year between 1990 and 2010.4 • Scaling up of diarrhoea and pneumonia interventions would cost US$6·715 billion, only

Despite such decreases, these disorders are two of the $2·9 billion more than present levels of spending; costs needed for lives saved calculated

most common reasons for health service attendance and on the basis of estimates of projected spending based on historic trend

hospital admission, with an estimated 1731 (uncertainty • Scaling up of these interventions could also ensure equitable delivery of care

range 1376–2033) million episodes of childhood diarrhoea • The cost-effectiveness of these interventions in national health systems needs

(uncertainty range 26·6–42·4 million severe episodes) urgent assessment

and 120 (60·83–277·03) million episodes of pneumonia • With an increasing number of countries deploying community health-worker programmes

(10·03–40·04 million severe episodes) in 2011.5,6 to reach unreached populations, real opportunities exist to scale-up community advocacy

Pneumonia and diarrhoea deaths are closely associated, and education programmes and early case detection and management strategies

with overlapping risk factors such as those related to

www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013 1417

Series

(Prof H Campbell MD, reductions in child mortality.7 However, to reduce selected these interventions from several previous

Prof I Rudan PhD) childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea, interventions are reports that identified their benefits and effects.9,14–26 We

Correspondence to: needed that directly lower disease transmission and specifically reviewed the interventions to identify data

Prof Zulfiqar A Bhutta, Division severity, and promote access to life-saving treatment once for their effectiveness on diarrhoea or pneumonia, or

of Woman and Child Health,

Aga Khan University,

a child becomes sick. Previous reviews8–11 have shown that both; incidence; and morbidity or mortality. Systematic

Karachi 74800, Pakistan increases in coverage with present evidence-based inter- reviews of potential interventions were undertaken by

zulfiqar.bhutta@aku.edu ventions could greatly reduce child mortality and deaths teams of researchers in Karachi, Pakistan; Baltimore,

from diarrhoea and pneumonia. However, little consensus USA; and Toronto, Canada, and were done with

exists about approaches to scale up coverage and about standard methodologies. Reviews were done in line

delivery strategies to reduce disparities and provide with Lives Saved Tool (LiST) methods,13 employing

equitable access to marginalised populations.12 Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Develop-

In this Series paper, we systematically review evidence ment, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria (appendix).

See Online for appendix for the effectiveness of various potential health inter- Researchers did 26 reviews for various interventions,

ventions on morbidity and mortality due to diarrhoea and consisting of 15 new reviews done to generate estimates

For the Child Health pneumonia in line with guidelines from the Child Health of effect, and assessment of 11 existing reviews for

Epidemiology Reference Group Epidemiology Reference Group.13 We used a standardised possible updates.

see http://www.cherg.org

method with criteria from the Child Health and Nutrition

Research Initiative (CHNRI) to identify priority areas for Interventions for both diarrhoea and

research and future interventions. We modelled the pneumonia

potential effect of delivery of these interventions to the Strategies to promote breastfeeding

75 high-burden countries that are part of the Countdown Table 1 summarises the available evidence and effect

For more on Countdown to to 2015 initiative and assessed the result of scaling-up of estimates for interventions to prevent and manage

2015 see http://www. interventions on diarrhoea and pneumonia mortality diarrhoea and pneumonia. Breast milk provides various

countdown2015mnch.org/

across poverty quintiles in three countries (Bangladesh, immunological, psychological, social, economic, and

Pakistan, and Ethiopia). environmental benefits, and is therefore recommended

as the best feeding option for newborn babies and young

Interventions reviewed and the conceptual infants in developing countries, even in HIV-infected

framework populations.31 Lamberti and colleagues27 reviewed

We used a conceptual framework to assess preventive 18 studies from developing countries reporting the effect

and case management interventions for diarrhoea of breastfeeding on diarrhoea morbidity and mortality.

and pneumonia, including preventive and therapeutic The investigators estimated that not breastfeeding was

interventions common to both disorders (figure 1). We associated with a 165% increase in diarrhoea inci-

dence in 0–5-month-olds and a 32% increase in

6–11-month-olds. Not breastfeeding was also associated

Environmental with a 47% increase in diarrhoea-related mortality in

WASH,* reduce overcrowding

and household air pollution Increased 6–11-month-olds and a 157% increase in 12–23-month-

susceptibility Delivery platforms

Promotion of community-based olds. Overall, not breast feeding was associated with a

Nutrition health and behavioural change 566% increase in all-cause mortality in children aged

Breastfeeding promotion,* 6–11 months, and a 223% increase in mortality in those

preventive vitamin A or zinc

supplementation* aged 12–23 months.

Financial incentives to promote We assessed the effect of various educational and

care seeking

Vaccines Exposure promotional strategies on rates of exclusive, predominant,

Measles, Haemophilus influenzae partial, and no breastfeeding.28 Rates of exclusive breast-

type b, pneumococcal infection, Integrated community case

rotavirus, cholera management

feeding increased significantly because of breastfeeding

promotional interventions; rates of not breastfeeding

Treatment reduced significantly. The effects reported for rates of

Oral rehydration solution, predominant and partial breastfeeding were not signifi-

continued feeding after

diarrhoea, zinc for diarrhoea Pneumonia

Facility-based IMCI cant. After 6 months, educational interventions had no

treatment, probiotic use, significant effect, but did increase rates of partial

Diarrhoea

antibiotics and oxygen therapy breastfeeding by 19%. Subgroup analyses suggested that

for pneumonia, antibiotics for

dysentery combined individual and group counselling was more

effective than either technique alone. Overall, in develop-

Survival Death

ing countries, facility and combined facility-based and

community-based interventions led to greater improve-

ments in breastfeeding rates, with greater effects of

Figure 1: Conceptual framework of the effect of interventions for diarrhoea and pneumonia

WASH=water, sanitation, and hygiene. IMCI=Integrated Management of Childhood Illness. *Interventions breastfeeding promotion and support interventions, than

common to both diarrhoea and pneumonia. routine care.

1418 www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013

Series

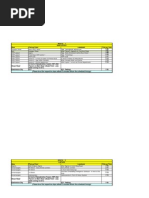

Evidence reviewed Effect estimates

Breastfeeding and Existing review of 18 studies Not breast feeding was associated with a 165% (RR 2·65, 95% CI 1·72–4·07) increase in diarrhoea

the risk for from developing countries27 incidence in babies aged 0–5 months, a 32% (1·32, 1·06–1·63) increase in those aged 6–11 month, and a

morbidity and 32% (1·32, 1·06-1·63) increase in those aged 12–23 months. No breastfeeding is also associated with a

mortality 47% (1·47, 0·67–3·25) increase in diarrhoea mortality in babies aged 6–11 months, and a 157% (2·57,

1·10–6·01) increase in those aged 12–23 months

Breastfeeding New review of Significant increases were reported in rates of exclusive breastfeeding as a result of promotional

education and 110 randomised trials and interventions: 43% at 1 day, 30% at 0–1 months, and 90% at 1–6 months. Rates of no breastfeeding

effects on quasi-experimental studies28 decreased by 32% at 1 day, 30% at 0–1 month, and 18% for 1–6 months. Effects on rates of predominant

breastfeeding rates and partial breastfeeding were not significant. After 6 months, educational interventions had no

significant effect except to increase rates of partial breastfeeding by 19%

Water, sanitation, Existing review of randomised Risk reductions for diarrhoea of 48% with hand washing with soap, 17% with improved water quality,

and hygiene trials and quasi-experimental and 36% with excreta disposal

interventions and observational studies29

Preventive zinc Existing review of Preventive zinc supplementation resulted in an 18% (RR 0·82, 95% CI 0·64–1·05) non-significant

supplementation 18 randomised trials from reduction in diarrhoea-related mortality and a 9% non-significant reduction in all-cause mortality

developing countries30 (0·91, 0·82–1·01). Preventive supplementation resulted in a 15% (0·85, 0·65–1·11) non-significant

reduction in ALRI-related mortality

RR=relative risk. ALRI=acute lower respiratory infection.

Table 1: Interventions common to both childhood diarrhoea and pneumonia

Strategies for improved water provision, use, diarrheoa mortality and of 15% in pneumonia mortality.

sanitation, and hygiene promotion Preventive zinc supplementation was associated with a

Consensus exists about the importance of improved 13% reduction in the incidence of diarrhoea (relative risk

water supply and excreta disposal for prevention of [RR] 0·87, 95% CI 0·81–0·94) and a 19% reduction in

diseases, especially diarrhoeal diseases. Waddington and pneumonia morbidity (0·81, 0·73–0·90).

colleagues32 assessed the effectiveness of these inter-

ventions and concluded that those for water quality Diarrhoea-specific interventions

(protection or treatment of water at source or point of Preventive interventions

use) were more effective than those to improve water Table 2 summarises the evidence and effect estimates for

supply (improved source of water or improved distri- interventions to prevent and manage diarrhoea. Rotavirus

bution, or both). Interventions for water quality were is the most common cause of severe dehydrating diar-

associated with a 42% relative reduction in diarrhoea rhoea in infants worldwide.5 In their review of six studies

morbidity in children, whereas those for water supply assessing the effectiveness of new rotavirus vaccines,

had no significant effects. Overall, sanitation inter- Munos and colleagues34 estimated that use of these

ventions led to an estimated 37% reduction in childhood vaccines was associated with a 74% reduction in very

diarrhoea morbidity and hygiene interventions to a 31% severe rotavirus infections, a 61% reduction in severe

reduction. Subgroup analysis suggests that provision of infections, and reduced rotavirus-related hospital admis-

soap was more effective than education only. Cairncross sion in young children by 47%. These summary effects

and colleagues29 estimated the effect of water, sanitation, do not show the reduced effectiveness of the vaccine in

and hygiene strategies and estimated risk reductions for different geographic settings, with studies reporting 54%

diarrhoea of 48% for hand washing with soap, 17% with effectiveness in Malawi,40 and even lower efficacy (43%)

improved water quality, and 36% with excreta disposal. in Mali.41

Although the investigators regarded much of the Although case management with oral rehydration

evidence to be of poor quality, the findings were therapy has substantially improved case-fatality rates for

consistent enough to support the provision of water cholera, the infection can still kill rapidly, especially in

supply, sanitation, and hygiene for all. outbreak settings.42 Old-generation injectable cholera

vaccines have been abandoned since the 1970s because of

Preventive zinc supplementation their restricted effectiveness and local side-effects. We

About 17·3% of the world’s population is zinc deficient identified 12 studies, all from developing countries,

and this deficiency is most prevalent in children younger which assessed the efficacy and effectiveness of oral

than 5 years in developing countries.33 Yakoob and cholera vaccine.35 We estimated that this vaccine reduced

colleagues30 assessed 18 studies from developing risk of cholera infection in children younger than 5 years

countries and showed that preventive zinc supple- by 52%. Such evidence for the effectiveness of oral

mentation was associated with a non-significant cholera vaccines makes them good candidates for cholera

reduction of 9% in all-cause mortality (table 1). Zinc control in endemic areas. Research shows that because

alone resulted in a non-significant reduction of 18% in of herd protection, even moderate coverage levels of

www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013 1419

Series

Evidence reviewed Effect estimates

Preventive interventions

Rotavirus vaccine Existing review of six randomised Rotavirus vaccines were 74% (95% CI 35–90) effective against very severe rotavirus infection and 61% (38–75) against

trials and quasi-experimental severe infection. Effectiveness against hospital admission for rotavirus was 47% (22–64)

studies34

Cholera vaccine New review of 12 randomised Cholera vaccine was 52% (RR 0·48, 95% CI 0·35–0·64) effective against cholera infection. Vibriocidal antibodies increased by

trials and quasi-experimental 124% (2·24, 1·32–3·80). Relative risk of one or more adverse events was 1·42 (1·06–1·89)

studies35

Therapeutic interventions

ORS and recommended home Existing review of 205 studies Use of ORS reduced diarrhoea mortality by 69% (51–80) and treatment failure by 0·2% (0·1–0·2). Evidence for the benefit of

fluids mostly from developing recommended home fluids was insufficient

countries36

Zinc Existing review of 13 randomised Zinc administration for diarrhoea management significantly reduced all-cause mortality by 46% (RR 0·54, 95% CI

trials from developing countries37 0·32–0·88) and hospital admission by 23% (0·77, 0·69–0·85). Zinc treatment resulted in a non-significant reduction in

diarrhoea mortality by 66% (0·34, 0·04–1·37) and diarrhoea prevalence by 19% (0·81, 0·53–1·04)

Zinc administration for diarrhoea management resulted in a 28% reduction in pneumonia-specific mortality (RR 0·72,

95% CI 0·23–2·09), a 50% reduction in hospital admissions for pneumonia (0·50, 0·18–1·39), and an observed 23%

reduction in pneumonia prevalence (0·77, 0·47–1·25)

Feeding strategies and New review of 29 randomised In acute diarrhoea, lactose-free diets significantly reduced the duration of diarrhoea compared with lactose-containing diets

improved dietary trials from developing countries38 (SMD –0·36, 95% CI –0·62 to –0·10). Treatment failure was also significantly reduced (RR 0·53, 0·40–0·70). Weight gain did

management of diarrhoea not have any significant effect (SMD 0·05, –0·22 to 0·33)

Antibiotics for treatment of New review of four randomised Antibiotic treatment of shigella reduced clinical failure by 82% (RR 0·18, 0·10–0·33), whereas bacteriological failure

shigella trials from developing countries39 decreased by 96% (0·04, 0·01–0·12)

Antibiotics for treatment for New review of two randomised Findings showed a 63% (RR 0·37, 95% CI 0·19–0·71) reduction in clinical failure and a 75% (0·25, 0·12–0·53) reduction in

cholera trials39 bacteriological failure

Antibiotics for treatment for New review of three randomised Findings showed a 52% (RR 0·48, 0·30–0·75) reduction in rates of clinical failure, a 38% (0·62, 0·46–0·83) reduction in

cryptosporidiosis trials39 parasitological failure, and a 76% (0·24, 0·04–1·45) non-significant reduction in all-cause mortality

RR=relative risk. ORS=oral rehydration solution. SMD=standardised mean difference.

Table 2: Interventions for the prevention and management of diarrhoea

targeted populations with killed oral cholera vaccine continued feeding alongside administration of oral

could lead to almost complete control of cholera;43,44 rehydration solution and zinc therapy. However, some

however, this control would not prevent outbreaks in debate surrounds what the optimum diet or dietary

other populations. ingredients are to hasten recovery and maintain nutri-

tional status in children with diarrhoea. We did an

Therapeutic interventions extensive review38 of all studies of feeding strategies and

Because the immediate cause of death in most cases of food-based interventions in children younger than 5 years

diarrhoea is dehydration, deaths are almost entirely with diarrhoea in low-income and middle-income coun-

preventable if dehydration is prevented or treated. In a tries. Although illness duration was shorter and risk of

review of the efficacy and effectiveness of oral rehydration treatment failure 47% lower in children with acute

solution and recommended home fluids, Munos and diarrhoea who consumed lactose-free rather than lactose-

colleagues36 assessed 205 studies, mostly from developing containing liquid feeds, we noted no effect of lactose

countries. Use of oral rehydration solution reduced avoidance on stool output or weight gain. Pooled analyses

diarrhoea specific mortality by 69% and rates of treatment of trials comparing commercial preparations or specialised

failure by 0·2% (table 2). Since 2004, WHO and UNICEF ingredients to foods available in the home showed no

have recommended zinc for the treatment of diarrhoea. beneficial effects in either acute or persistent diarrhoea,

Walker and colleagues37 reviewed 13 studies from suggesting that locally available ingredients can be used to

developing countries of zinc supplementation for manage childhood diarrhoea at least as effectively as can

diarrhoea and concluded that zinc administration was commercial preparations or specialised ingredients.

associated with a significant reduction of 46% in all- Moreover, when we restricted this analysis to lactose-free

cause mortality and of 23% in diarrhoea-related hospital diets only, weight gain in acute diarrhoea was higher in

admissions. The effects on prevalence of diarrhoea and children who consumed foods available in the home.

mortality were not significant. Several of the large studies Antibiotics are used to treat some forms of bacterial

of zinc treatment for diarrhoea were also associated with diarrhoea, especially dysentery. A review by Traa and

reported benefits for pneumonia mortality, hospital colleagues45 assessed the effectiveness of WHO-recom-

admission, and prevalence, albeit not significantly. mended antibiotics—ciprofloxacin, ceftriaxone, and

Current WHO guidelines for the management and pivmecillinam—for the treatment of dysentery, and

treatment of diarrhoea in children strongly recommend concluded that antibiotics are effective in reducing the

1420 www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013

Series

clinical and bacteriological signs and symptoms of this an 18% non-significant reduction in pneumonia-specific

disorder and can thus be expected to decrease diarrhoea mortality.57 Large-scale use of these vaccines is associated

mortality attributable to dysentery by more than 99%. We with important positive effects related to herd immunity

assessed the effectiveness of WHO-recommended anti- and population benefits, and negative indirect effects

biotics in diarrhoea in relation to cholera, shigella, and related to serotype replacement and emergence of

cryptosporidium infections.39 The mainstay of treatment resistant strains. The magnitude and importance of these

in cholera is rehydration; WHO recommends antibiotics indirect effects is likely to vary by setting.

for severe cases. We identified two46,47 randomised trials

from developing countries and showed that antibiotic Therapeutic interventions

management of cholera resulted in a 63% reduction in Treatment with appropriate antibiotics and supportive

rates of clinical failure and a 75% reduction in rates of management in neonatal nurseries is the cornerstone of

bacteriological failure.39 management of neonatal sepsis and pneumonia, with

A range of antibiotics are used to treat shigella strong biological plausibility that such treatment saves

dysentery, dependent on variations in resistance patterns lives. A review60 of community-based management of

by region. We analysed four studies48–51 from developing neonatal pneumonia showed a 27% reduction in all-

countries, which showed that antibiotic management of cause neonatal mortality and a 42% reduction in

shigella resulted in an 82% reduction in rates of clinical pneumonia-specific mortality. Zaidi and colleagues57

failure and a 96% reduction in rates of bacteriological estimated the effect of provision of oral or injectable

failure.39 Cryptosporidium can cause life-threatening antibiotics at home or in first-level facilities, and of in-

disease in people with AIDS and contributes greatly to patient hospital care on neonatal mortality from

morbidity in children in developing countries. We pneumonia and sepsis. Results suggested a 25%

systematically analysed three studies52–54 from developing reduction in all-cause neonatal mortality and a 42%

countries. Antibiotics for treatment of cryptosporidiosis reduction in neonatal pneumonia mortality. Similar

reduced mortality by 76%, rates of clinical failure by 52%, studies in older infants and children younger than

and rates of parasitological failure by 38%.39 None of 5 years have focused on choice and duration of antibiotic

these studies assessed the effect of a given treatment treatment for pneumonia in various settings.61–63

regimen on emergence of antibiotic resistance over time; Information is scarce about the effect of low-cost pulse

however, the investigators noted that use of nalidixic acid oximetry and oxygenation systems. A large multihospital

for treatment of shigellosis could be associated with quasi-experimental study59 in Papua New Guinea with an

rapid emergence of quinolone resistance.55 intervention of hypoxaemia detection by pulse oximetry,

together with oxygen therapy with an assured oxygen

Pneumonia-specific interventions supply from oxygen concentrators, resulted in a 35%

Preventive interventions significant reduction in mortality from severe pneumonia

Table 3 summarises the evidence and effect estimates for in patients admitted to hospital.

interventions to prevent and manage pneumonia. Several

effective vaccines are available for prevention of various Delivery platforms

causes of pneumonia. In regions where measles is a Community-based promotion and case management

substantial cause of childhood morbidity and mortality, Although evidence shows the efficacy and effectiveness

measles vaccination is an important intervention that of many interventions, these interventions are not

can also affect risk of subsequent complications, includ- accessible to people in need; hence, focus on delivery

ing secondary bacterial infections and diarrhoea. Sudfeld strategies has increased. One of the main contributors to

and colleagues56 proposed that measles vaccination was the delay in meeting the targets of Millennium

85% effective for prevention of measles in children Development Goal 4 is the paucity of trained human

younger than 1 year. resource professionals in first-level health services, and

We assessed the effectiveness of Haemophilus influenzae the reduced awareness of and accessibility to services for

type b and pneumococcal conjugate vaccines.57 For those living in large socioeconomically, geographically

prevention of invasive H influenzae type b and pneumonia, deprived, ethnically marginalised populations. One

we identified six studies from developing countries method of community-based case management is to

yielding estimates of an 18% non-significant reduction in provide these amenities through community health

radiologically confirmed pneumonia, a 6% reduction in workers with home visitation and community-based

severe pneumonia, and a 7% non-significant reduction in sessions for education and promotion of care seeking.

pneumonia-specific mortality. We reviewed six studies These approaches have been assessed for both newborn

from developing countries for the prevention of invasive babies and children aged 1–59 months.

pneumococcal disease and pneumonia with pneumococcal Lassi and colleagues64,65 estimated that community-

conjugate vaccines, which were associated overall with a based packaged interventions delivered by community

29% significant reduction in radiologically confirmed health workers significantly increase levels of care-

pneumonia, an 11% reduction in severe pneumonia, and seeking behaviour for neonatal morbidy by 52%. The role

www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013 1421

Series

Evidence reviewed Effect estimates

Preventive interventions

Measles vaccine Existing review of five randomised Measles vaccines was 85% (95% CI 83–87) effective in prevention of disease before age 1 year

and quasi-randomised trials56

Hib vaccine Existing review of four randomised Hib vaccines resulted in a 6% (RR 0·94, 95% CI 0·89–0·99) significant reduction in severe pneumonia, an 18% (0·82,

trials and two case-control studies 0·67–1·02) non-significant reduction in radiologically confirmed pneumonia, and a 7% (0·93, 0·81–1·07) reduction in

from developing countries57 pneumonia mortality

Pneumococcal conjugate Six randomised trials from Pneumococcal vaccines resulted in a 29% (RR 0·71, 95% CI 0·58–0·87) significant reduction in radiologically confirmed

vaccine developing countries57 pneumonia, an 11% (0·89, 0·81–0·98) reduction in severe pneumonia, and an 18% (0·82, 0·44–1·52) non-significant

reduction in pneumonia mortality

Therapeutic interventions

Antibiotics for the treatment Existing review of four Oral or injectable antibiotics at home or in first-level facilities, and in-patient hospital care, resulted in a 25% (RR 0·75,

and management of neonatal quasi-experimental studies58 0·64–0·89) reduction in all-cause neonatal mortality and a 42% (0·58, 0·41–0·82) reduction in neonatal pneumonia

pneumonia mortality

Oxygen systems One quasi-experimental study Detection of hypoxaemia by pulse oximetry together with oxygen therapy with an assured oxygen supply from oxygen

from Papua New Guinea59 concentrators resulted in a 35% (RR 0·65, 0·52–0·78) significant reduction in severe pneumonia mortality

Hib=Haemophilus influenzae type b. RR=relative risk.

Table 3: Interventions for the prevention and management of pneumonia

of these health workers has also been assessed in various such incentives have been recommended as an important

settings in large-scale programmes in which their strategy to reduce barriers to access to health care.69 An

presence improved immunisation uptake and care extensive review was undertaken to identify relevant

seeking for childhood illnesses.66 We estimated the effect studies reporting the effect of financial incentives on

of community-based delivery strategies with community coverage of health interventions and behaviours targeting

health workers on the coverage and uptake of essential children younger than 5 years.12 Investigators assessed

commodities for diarrhoea and pneumonia: oral the effect of financial incentive programmes on five

rehydration solution, zinc therapy for diarrhoea, and categories of intervention: breastfeeding practices,

antibiotics for pneumonia.67 We also assessed the effect immunisation coverage, diarrhoea management, health-

of these interventions on care-seeking behaviour and on care use, and other preventive strategies. Findings

potentially harmful practices, such as prescription of showed that financial incentives could promote increased

unnecessary antibiotics for diarrhoea. Theodoratou and coverage of several important child health interventions,

colleagues68 estimated that community case management but the quality of available evidence was low. Of all

of pneumonia could result in a 70% reduction in financial incentive programmes, more pronounced

pneumonia mortality in children younger than 5 years. effects seem to be achieved by those that directly removed

We updated the previous estimate and also estimated the user fees for access to health services. Some indication of

effect of case management on diarrhoea mortality. We effect was also reported for programmes that conditioned

included 26 studies and estimated that community-based financial incentives on the basis of participation in health

interventions are associated with a 160% significant education and attendance to health-care visits.

increase in use of oral rehydration solution (RR 2·60,

95% CI 1·59–4·27) and an 80% increase in use of zinc in Emerging interventions for diarrhoea and

diarrhoea.67 Furthermore, findings showed a 13% (1·13, pneumonia

1·08–1·18) increase in care-seeking for pneumonia, and Research priorities to develop and deliver interventions

a 9% (1·09, 1·06–1·11) increase in that for diarrhoea. We We undertook a systematic analysis of various emerging

noted a 75% significant decline (0·25, 0·12–0·51) in interventions for diarrhoea and pneumonia on the basis

inappropriate use of antibiotics for diarrhoea, and a 40% of priorities emerging from the global research priority

(0·60, 0·51–0·70) reduction in rates of treatment failure review process.70,71 Preventive interventions assessed were

for pneumonia. Community case management for reductions in levels of household air pollution,72,73 and

pneumonia by community health workers was associated vaccines for Shigella43,74–77 and enterotoxigenic Escherichia

with a 32% (0·68, 0·53–0·88) reduction in pneumonia- coli.43 Therapeutic interventions were probiotics for

specific mortality, whereas evidence for diarrhoea-related diarrhoea78 and antiemetics for gastroenteritis.79 The

mortality was weak.67 appendix summarises the evidence for some of these

interventions, which are promising, but not yet

Reduction of financial barriers recommended for inclusion in programmes.

Financial incentives are becoming widely used as policy We undertook two expert panel methods to assess the

strategies to alleviate poverty, to promote care seeking, feasibility and effectiveness of ten emerging health

and to improve the health of populations. Additionally, interventions for childhood diarrhoea and 23 for

1422 www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013

Series

Panel: Research priorities to prevent childhood diarrhoea and pneumonia mortality

We undertook two expert panel methods to assess feasibility however, product development cost was considered to be

and potential effectiveness of ten emerging health feasible. Introduction of oxygen systems was considered

interventions against childhood diarrhoea and 23 against answerable and there were no major cost concerns, but these

pneumonia (see appendix for the list of interventions for both systems were not deemed sustainable, sufficiently acceptable,

illnesses). For each method we assembled a group of 20 leading or equitable. By comparison, common protein vaccines for

international experts from international agencies, industry, influenza were considered sustainable, acceptable, and

basic science, and public health research, who took part in a equitable, but concerns remained about answerability and costs

Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative (CHNRI) priority of development. Emerging point-of-care diagnostic techniques

setting process. The experts used nine different criteria relevant were restricted with suboptimum levels of access to care,

to successful development and implementation of emerging care-seeking behaviour, and the availability of first-line and

interventions. They assessed the likelihood of answerability (in second-line antibiotics.

an ethical way), affordable cost of development and The top ten research areas in the delivery categories for both

implementation of the intervention, efficacy and effectiveness the diarrhea and pneumonia process are:

against the disease, deliverability, sustainability, maximum 1 Identify the barriers to increases in coverage and ensure that

effect on mortality reduction, acceptability to health workers, hard to reach populations have access to effective

acceptability to end users, and positive effect on equity. Further interventions—ie, oral rehydration solution, zinc,

details about the modified CHNRI framework, the criteria used, Haemophilius influenza type b and pneumococcal vaccines,

and the process of the expert opinion exercise have been WHO’s seven-point plan, and WHO’s strategy for acute

published elsewhere.82 respiratory infection

For pneumonia interventions, when the scores against all nine 2 Identify contextual or cultural factors that positively or

criteria were analysed, the experts showed mostly collective negatively affect care-seeking behaviour and which factors

optimism towards improvement of low-cost pneumococcal most effectively drive care-seeking behaviour

conjugate vaccines, development of non-liquid and mucosal 3 Investigate the effectiveness of culture-appropriate health

antibiotic paediatric formulations, and development of education and public health messages on changes in

common-protein pneumococcal vaccines. The second level of health-seeking behaviour, hospital admission, and

priority was assigned to improvements in existing vaccines (eg, mortality, and which communication strategies are best to

measles or Haemophilius influenzae type b) to enable needle-free spread knowledge and generate care-seeking behaviour

delivery and heat stability. This assignment was followed by 4 Identify the main barriers to increase demand for and

assessments of maternal immunisation, improved use of compliance with vaccination schedules for available

oxygen systems, and the development of combination vaccines vaccines in different contexts and settings

and vaccines against major viral pathogens. The fourth level of 5 Identify the added effect of integrated Community Case

priority was assigned to improved point-of-care diagnostic Management or Integrated Management of Childhood

techniques. The lowest scores were assigned to passive Illness on early and equitable administration of appropriate

immunisation, action on risk factors such as indoor air pollution treatment for acute diarrhoea and for pneumonia

or poor sanitation, or development of vaccines against neonatal 6 Identify the best indicators for measurement of uptake of

bacterial pathogens that cause sepsis. The method suggested interventions and effectiveness of communication

that most of the emerging interventions are still not feasible. strategies

7 Identify the effect on child health outcomes of interventions

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, which were still regarded as

to support mothers, for example to reduce maternal

an emerging intervention because of low uptake in low-income

depression, strengthen maternal coping, and develop

and middle-income countries at the time, achieved scores of

problem-solving skills for child health

more than 80% for all criteria apart from low product cost,

8 Identify the capacity of health systems worldwide to

which became the main point of discussion once they were

correctly diagnose and manage childhood pneumonia, and

introduced. By comparison, common protein pneumococcal

the obstacles to correct diagnosis and case management in

vaccines are still hindered by concerns about answerability

developing countries

(although answerability is getting closer to 80%), and about all

9 Identify how trained health workers can be effectively

criteria related to their future cost. Other interventions have

trained and sustained and whether they can be trained to

quite different score profiles. For example, antirespiratory

adequately assess, recognise danger signs, refer, and treat

syncytial virus vaccine for use in infants showed no feasibility

acute respiratory infections, including safe and effective

for all criteria apart from acceptance for health workers,

administration of antibiotics

whereas monoclonal antibodies for passive immunisation

10 Identify the effectiveness of a community-led approach to

against respiratory syncytial virus was completely unfeasible for

total sanitation

product cost, affordability, and sustainability concerns;

www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013 1423

Series

pneumonia (appendix). We undertook a method to Community Case Management and Integrated Manage-

develop research priorities in line with the CHNRI80–82 ment of Childhood Illness (IMCI) on early and equitable

with various experts worldwide.83 For diarrhoea, we administration of appropriate treatment. Furthermore,

expanded on previous methods84,85 by identifying priorities prioritisation process for pneumonia identified the need

to reduce morbidity and mortality caused by childhood to establish whether community health workers or

diarrhoea in the next 15–20 years.83 For pneumonia, we community volunteers could be trained to adequately

used a research method to define priorities to reduce assess, recognise danger signs of, refer, or treat acute

mortality caused by childhood pneumonia by 2015,86 respiratory infections effectively.

including health policy and systems research. The panel

shows the highest ranked research questions in these LiST modelling effects on mortality outcomes

two areas. In these areas, research priorities including for 75 Countdown countries

identification of barriers to health-care access—eg, imple- We selected a set of interventions from those reviewed

mentation barriers to increase coverage of existing, for modelling on the basis of their proven benefits and

effective interventions—and identification of drivers of availability in public-health programmes. We used LiST

care-seeking behaviour, ranked highly. Respondents to model the potential effect of introduction of these

prioritised assessment of the effect of Integrated interventions with a standard sequential introduction in

health systems of the 75 high-burden Countdown

100 countries. LiST estimates the effect of increases in

90 intervention coverage on deaths from one or more

80 causes, or in reduction of the prevalence of a risk factor

70 (appendix). We modelled the effect of increased coverage

Coverage (%)

60 of individual interventions from present levels for each

50 country (figure 2) on child mortality. We used two

40 approaches—historical trends and ambitious scale-up—

30 to project coverage trends and scaling up of various

20 interventions identified to 2025.

10

With the first approach (historic trends), we assessed the

0

pragmatic trends of increased coverage on the basis of

di of

ta in A

ou ed

om on

ile a

lu ion

nt or

on r

ol f

m fo

to ret

cin

sto l o

se s f

r s ov

ee n

e h ti

ng

rce

t)

An ion

ia

historical rates of change for the individual interven-

so rat

eu ics

n’s sa

stf tio

en m

er

or xc

ac

th ec

tio

dy iotic

te pr

re po

t

a

ne d e

d

t

bv

in nn

ea o

pn io

wa Im

lem Vit

hy

br rom

ild is

tib

tib

co

tri ve

tions in each country to predict the coverage of specific

Hi

re

d

(la ro

An

ch nic

er

P

al

al p

at

Or

e

os Im

pp

interventions to 2025 if trends continued unchanged. In

gi

W

Hy

su

the second approach (ambitious scale-up) we used a

sp

di

predefined target coverage level of 80% for all interventions

Figure 2: Coverage of interventions in 75 Countdown countries by quartiles

except vitamin A supplementation and vaccines, for which

Figure shows medians and IQRs. Hib=Haemophilus influenzae type b.

we used a 90% target coverage. Table 4 shows the effect of

these two approaches on diarrhoea and pneumonia deaths

Estimated deaths (2011) Deaths averted (2025 vs 2011)

by 2025. The data show that based on country-specific

Historical trends (2025) Ambitious scale-up (2025) historic trends 54% of diarrhoea and 51% of pneumonia

All deaths deaths in children younger than 5 years can be averted by

Children aged <5 years 7 038 418 1 821 329 (26%) 2 378 492 (34%) implementation of these interventions by 2025. However,

Neonatal deaths 2 918 004 787 783 (11%) 874 217 (12%) ambitious scaling up of interventions would eliminate

Infants aged 1–59 months 4 120 414 1 033 546 (15%) 1 504 275 (21%) almost all diarrhoea deaths, but only two-thirds of

Diarrhoea deaths pneumonia deaths, which shows the continued need to

Children aged <5 years 711 569 382 415 (54%) 673 743 (95%) develop and implement more effective interventions to

Neonatal deaths 49 902 16 016 (2%) 35 174 (5%) prevent and treat pneumonia (figure 3).

Infants aged 1–59 months 661 667 366 399 (51%) 638 569 (90%) We also assessed the potential effect of individual

Pneumonia deaths interventions on lives saved by scaling up interventions to

Children aged <5 years 988 578 499 859 (51%) 662 495 (67%)

reach 90% coverage for vaccines and vitamin A, and 80%

Neonatal deaths 326 308 150 143 (15%) 224 501 (23%)

coverage for all other interventions and projected lives

Infants aged 1–59 months 662 270 349 716 (35%) 437 994 (44%)

saved due to diarrhoea and pneumonia up to 2025. The

analysis showed that water, sanitation, and hygiene

Results are based on implementation of 15 interventions: improved water source, hand washing with soap, improved interventions could prevent almost 0·5 million child

sanitation, hygienic disposal of children’s stools, breastfeeding promotion, Haemophilus influenzae type b vaccine,

deaths due to diarrhoea and pneumonia by 2025; almost

pneumococcal vaccine, rotavirus vaccine, vitamin A supplementation, zinc supplementation, oral rehydration solution,

zinc for diarrhoea treatment, antibiotics for dysentery, oral antibiotics for pneumonia, and case management. the same number as that shown for the projected effect of

H influenzae type b, pneumococcal, and rotavirus vaccines.

Table 4: Diarrhoea and pneumonia deaths averted in the 75 high-burden Countdown countries between

Similar effects are noted in scaling up of community case

2011 and 2025 with the historical trends and ambitious scale-up approaches

management in children younger than 5 years (figure 4,

1424 www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013

Series

appendix). These findings have policy relevance and 800 000 Scale up Historical trends

suggest that countries should consider a range of best

Number of deaths averted

700 000

buys to address childhood diarrhoea and pneumonia. 600 000

500 000

400 000

Cost analysis 300 000

Table 5 shows results of our cost analysis with LiST of 200 000

interventions and packages in 2025 for the 75 Countdown 100 000

countries. The costs are based on four components: 0

ea n

ar deat ea

on at

at year s

m ea ia

on at

5 th

Ne <5 y hs i

d on

personnel and labour, drugs and supplies, other direct

ho

m hs

m hs

rs

hs

ag on ths

s

Ne n < dea

th

th

m

n at

9 at

9 at

r

ar

eu

re de

–5 de

–5 de

re ia

di

costs, and indirect costs. We obtained assumptions about

ild on

pn

ild a

e 1 ea

e 1 ia

al

ch rhoe

ch m

at

ag rho

al

in eu

on

time needed for an intervention and costs for drugs and

ar

on

Pn

eu

Di

Di

Pn

supplies from the One Health Model87 developed by the

UN. Costs shown for daily zinc supplementation are for Figure 3: Additional effect of the ambitious scale-up approach on diarrhoea

and pneumonia deaths averted for the 75 Countdown countries up to 2025

6–36 months. For breastfeeding, there was difficulty in

translation of breastfeeding prevalence to breastfeeding

promotion for our costing analysis; therefore, breast-

feeding costs for the trend scenario were done by hand Pneumococcal vaccine

Case management of neonatal infections

with country-specific unit costs, prevalence, and births. Breastfeeding promotion

For scaling up of low-cost latrines, we estimated costs for Case management of pneumonia infections

Improved water source

all households, not just those with children younger than Zinc supplementation

5 years, and for H influenzae type b vaccine we used the Hib vaccine

Hand washing with soap

present cost of pentavalent vaccine for our estimates Improved sanitation

(US$2·95 per dose; appendix). Oral rehydration solution

On the basis of estimates of historic trend coverage, Rotavirus vaccine

Hygienic disposal of children’s stools

$3·8 billion dollars would be needed to avert Vitamin A supplementation

882 274 deaths due to diarrhoea and pneumonia, and for Zinc for treatment of diarrhoea

Antibiotics for dysentery

the ambitious scale-up plan, $6·715 billion dollars would

0 50 000 100 000 150 000 200 000 250 000 300 000 350 000

be needed—an extra $2·914 billion to save an additional

Number of deaths averted

557 163 lives. Drugs and supplies are the main cost items.

The cost breakdown by intervention showed that for Figure 4: Sequential effect of individual interventions on deaths due to diarrhoea and pneumonia

some interventions (oral rehydration solution and Haemophilus influenzae type b.

antibiotic treatment of dysentery), our analysis indicates

cost savings because the number of diarrhoea cases has discrepancies in provision of health care across various

fallen substantially in most places, whereas for other strata of socioeconomic status. To assess the effect of

interventions the costs increase because initial coverage reaching the poorest individuals through community-

levels are low and any increase in use results in a net based platforms, we assessed the benefit of three strategies

increase in cost (appendix). (breastfeeding promotion, scale up of interventions for

zinc or oral rehydration solution, and case management

Equitable delivery of interventions and effect of pneumonia) deploying community health workers in

A major limitation in previous strategies used to establish these strata. Our model showed that if 90% coverage were

outcomes has been relatively little emphasis on reducing achieved for these three interventions, 64% of diarrhoea

of inequities and targeting. We assessed the effect of deaths and 74% of pneumonia deaths could be averted in

interventions across equity strata for three countries the poorest quintiles in the three countries assessed. This

(Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Ethiopia). We estimated the finding shows that community-based platforms deploying

potential effect and cost-effectiveness of targeting of the community health workers could not only reduce overall

same set of interventions to address neonatal mortality burden, but also ensure equitable delivery of these inter-

and mortality in children younger than 5 years within ventions to those who need them most (appendix).

wealth quintiles. We computed all inputs except cause of

death for the two wealth quintiles by reanalysing the most Discussion

recent Demographic and Health Survey for the country Our findings are in line with those from previous reviews

(appendix). We estimated the effect of interventions on and studies, emphasising that effective interventions

lives saved for the two quintiles of socioeconomic status: exist to address childhood diarrhoea and pneumonia,

poorest (Q1) and poorer (Q2). The effect of various which are still major killers of children younger than

evidence-based interventions is greatest in the poorest 5 years worldwide. We refined and updated the evidence

quintiles (figure 5, appendix). Scaling up of these for a range of preventive, promotive, and therapeutic

interventions would not only reduce the overall burden of interventions, and by application of these estimates to

childhood mortality but would also greatly reduce the the LiST model, reaffirmed that these interventions

www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013 1425

Series

Historical trends Scale-up strategy

Personnel and Intervention Other direct Indirect Total Personnel and Intervention Other direct Indirect costs Total

labour costs costs labour costs costs

Water, sanitation, and hygiene*† $253·3 $1410·7 ·· ·· $1664·1 $404·2 $1678·3 ·· ·· $2082·4

Nutrition‡ $108·6 $2·5 $4·4 $15·1 $130·6 $368·9 $1785·4 $49·3 $171·0 $2374·7

Vaccines§ $45·3 $1623·7 $35·9 $124·6 $1829·5 $52·1 $1938·9 $42·1 $146·1 $2179·2

Case management¶ $41·5 $107·1 $6·4 $22·0 $177·1 $–0·5 $65·6 $3·2 $10·7 $79·1

Total $448·7 $3144·1 $46·7 $161·8 $3801·3 $824·7 $5468·2 $94·7 $327·8 $6715·4

*Includes $4 per year per household for latrines, hand washing, and hygienic disposal of excreta. No costs are included for the improved water supply or piped water. †Water connection in the home, improved water

source, improved sanitation (use of latrines or toilets), hygienic disposal of children’s excreta, and hand washing with soap. ‡Breastfeeding promotion, and supplementation of vitamin A and

zinc.§Haemophilus influenzae type b, pneumococcal, and rotavirus vaccines. ¶Oral rehydration solution, zinc for treatment of diarrhoea, antibiotics for dysentery, case management, and oral antibiotics.

Table 5: Estimated incremental costs (US$ million) by packages in 2025 for the 75 Countdown countries

Pakistan that allow mothers to practise exclusive breastfeeding for

Pneumonia deaths the first 6 months after childbirth and implementation of

Diarrhoea deaths

the International Code on Marketing of Breast Milk

Deaths averted Ethiopia Substitutes is insufficient. The same situation applies for

in poorest Pneumonia deaths interventions to address intrauterine growth retardation,

quintiles Diarrhoea deaths

a recognised risk factor for neonatal mortality and

Deaths averted Bangladesh childhood illnesses including diarrhoea and pneumonia.

in poorer Pneumonia deaths

quintiles Diarrhoea deaths

In view of the global burden of low birthweight, which

0 20 40 60 80 100

encompasses both prematurity and intrauterine growth

Proportion of deaths averted (%) retardation, this problem is a crucial risk factor that must

receive greater attention.

Figure 5: Equity analysis for Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and Pakistan

The remarkably low coverage of oral rehydration

solution for diarrhoeal episodes, and the almost negligible

could potentially eliminate diarrhoea deaths and prevent use of zinc for the management of diarrhoea, emphasises

almost two-thirds of childhood pneumonia deaths by the fundamental challenges faced in public health. About

2025 if implemented at scale. Many of these interventions four decades after findings showed the effectiveness of

would clearly affect morbidity and other outcomes, oral rehydration solution in population settings,88 global

although our present models do not allow for assessment coverage rates are negligible. Even a decade after WHO

of effect on disease incidence and adverse outcomes and UNICEF released recommendations for treatment of

contributing to overall disability. diarrhoea with improved oral rehydration solution and

Most the interventions exist within present health zinc, global uptake of zinc for the treatment of diarrhoea

systems, although their coverage and availability to poor is abysmally low. Our findings show that several

and marginalised populations varies greatly. Strategies for opportunities exist for scaling up the use of these

scaling up and emerging evidence of delivery platforms interventions with community health-worker program-

for key interventions have received relatively little focus. mes, free distribution, social marketing, and co-packaging

In addition to structural changes needed to reduce of zinc and oral rehydration solution, which can increase

environmental pollution and provide safe water and coverage by several times.89 Promising indications show

sanitation, many of the risks associated with development that such scaling up is beginning to happen and is being

of diarrhoea and pneumonia also need behavioural recommended as a strategy to reduce inequities in child

change at the household level. Our analysis emphasised survival in high-burden countries.90

the importance of focus on delivery strategies that target The forthcoming Decade of Vaccines initiative offers a

the poor, and hence a balance of demand creation and unique possibility that reductions in diarrhoea and

service delivery is needed to address these issues. pneumonia burden can be achieved with some of the

Our data show that key nutrition interventions for new effective vaccines for pneumonia and diarrhoea

prevention of childhood diarrhoea and pneumonia have through global financing and country-support mechan-

received scant attention, which is shown by poor rates of isms.91 Our estimates show that 27% of childhood

exclusive breastfeeding worldwide, especially in low- diarrhoea and pneumonia deaths can be averted by

income and middle-income countries. Several reasons deployment of three key vaccines: H influenzae type b,

exist for this finding, including low awareness of the pneumococcal conjugate, and rotavirus vaccines. A 90%

benefits of exclusive breastfeeding. In many low-income improvement in coverage of a package of life-saving

and middle-income countries there is no enabling childhood vaccines in 72 countries eligible for support

environment for exclusive breastfeeding. Few laws are in from the GAVI Alliance between 2011 and 2020 would

place to protect the employment and work conditions prevent the deaths of roughly 6·4 million children

1426 www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013

Series

younger than 5 years, corresponding to $231 billion Harry Campbell, Igor Rudan (University of Edinburgh, UK);

(uncertainty range $116–$614 billion) in the value of Lindsey Lenters, Diego Bassani, Kerri Wazny, Michelle Gaffey,

Alvin Zipursky (Sick Kids, Toronto).

statistical lives saved.91 The maximum benefits accrued

from pneumococcal and H influenzae type b vaccines, Conflicts of interest

We declare that we have no conflicts of interests.

contributing $105 billion ($52–$270 billion) from scale

up of pneumonia and rotavirus vaccines contributed Acknowledgments

Funding was provided by an unrestricted grant from the Bill & Melinda

$54 billion ($27–$138 billion) to these estimates.91 Gates Foundation to Aga Khan University and to collaborating universities

Despite persistent burden, childhood deaths from and institutions (Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins

diarrhoea and pneumonia are avoidable and 15 inter- University, Boston; University School of Public Health and Program for

ventions delivered at scale can save most of these avoidable Global Pediatric Research, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto). The

funding source had no role or control over the content and process of

deaths. In some of the high-burden countries with existing development of these papers, or in drafting of the report. The views

inequities in intervention coverage and a high burden of expressed in this report are solely those of the authors. We thank Yvonne

mortality in poor populations, strategies exist that can Tam (Johns Hopkins University) for assisting with LiST modelling,

Margaret Manley (Program for Global Pediatric Research, Toronto), and

reach these individuals and reduce the disproportionate

Asghar Ali (Aga Khan University, Karachi) for administrative support.

burden of diarrhoea and pneumonia mortality therein.

References

With an increasing number of countries deploying 1 UNICEF. Levels and trends in child mortality, estimates developed

community health-worker programmes to reach the by the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation. New

unreached, real opportunities exist to scale up community York: UNICEF, 2012.

advocacy and education programmes and early case 2 Countdown to 2015. Building a future for women and children:

the 2012 report. June, 2012. http://www.countdown2015mnch.

detection and management strategies. The new vaccines org/documents/2012Report/2012-Complete.pdf (accessed

for H influenzae type b, pneumococcal pneumonia, and March 18, 2013).

rotavirus diarrhoea could save at least 0·5 million lives in 3 Liu L, Johnson HL, Cousens S, et al. Child Health Epidemiology

Reference Group of WHO and UNICEF. Global, regional, and

the next decade. Nevertheless, major gaps remain in national causes of child mortality: an updated systematic analysis

implementation and strategies for scaling up. Operational for 2010 with time trends since 2000. Lancet 2010; 379: 2151–61.

research needs to be done urgently to establish the best 4 Fischer Walker CL, Perin J, Aryee MJ, Boschi-Pinto C, Black RE.

Diarrhea incidence in low- and middle-income countries in 1990

strategies to improve community uptake of the best and 2010: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 220.

practices and encourage household-level behaviour 5 Fischer Walker CL, Rudan I, Liu L, et al. Global burden of childhood

change. Furthermore, the best delivery channels need to pneumonia and diarrhoea. Lancet 2013; published online April 12.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016.S0140-6736(13)60222-6.

be identified to reach marginalised and disenfranchised 6 Nair H, Simões EAF, Rudan I, et al, for the Severe Acute Lower

populations, especially the urban poor. In view of the need Respiratory Infections Working Group. Global and regional

to optimise treatment strategies and reduce inappropriate burden of hospital admissions for severe acute lower respiratory

infections in young children in 2010: a systematic analysis.

use of antibiotics, the balance of antibiotic access and Lancet 2013; published online Jan 29. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

excess92 must be defined and research to address the S0140-6736(12)61901-1.

benefits and population-level safety of programmes for 7 Feng XL, Theodoratou E, Liu L, et al. Social, economic, political and

health system and program determinants of child mortality

Integrated Community Case Management should be reduction in China between 1990 and 2006: a systematic analysis.

done. Major advances in improvement of practical aspects J Glob Health 2012; 2: 10405.

of point-of-use water purification, low-cost sanitary 8 Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS, and the

Bellagio Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can

facilities, and improved housing and living conditions we prevent this year? Lancet 2003; 362: 65–71.

offer an opportunity to address some of the fundamental 9 Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, et al, and the Maternal and Child

challenges in reducing diarrhoea and pneumonia burden, Undernutrition Study Group. What works? Interventions for

maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet 2008;

but these methods need cost-effectiveness analyses. 371: 417–40.

Contributors 10 Fischer Walker CL, Friberg IK, Binkin N, et al. Scaling up diarrhea

ZAB conceptualised the review of interventions and led the process, prevention and treatment interventions: a Lives Saved Tool analysis.

supported by JKD and REB. The following members contributed to PLoS Med 2011; 8: e1000428.

specific reviews: LL to community case management, strategies for oral 11 Ozawa S, Stack ML, Bishai DM, et al. During the ‘decade of

rehydration solution, and financial platforms; MG to feeding practices vaccines,’ the lives of 6.4 million children valued at $231 billion

in diarrhoea and financial platforms; DB and KW to financial platforms; could be saved. Health Aff (Millwood) 2011; 30: 1010–20.

RAS to cholera vaccines, antiemetics, antibiotics for cholera and 12 Chopra M, Sharkey A, Dalmiya N, Anthony D, Binkin N, and the

shigella, and community case management; and ZL to community case UNICEF Equity in Child Survival, Health and Nutrition Analysis

management. KW and AZ led the Child Health and Nutrition Research Team. Strategies to improve health coverage and narrow the equity

Initiative (CHNRI) method for setting of research priorities, overseen gap in child survival, health, and nutrition. Lancet 2012; 380: 1331–40.

by ZAB. HC and IR contributed to the review of strategies to prevent 13 Walker N, Fischer-Walker C, Bryce J, Bahl R, Cousens S, and the

and treat pneumonia. ZAB wrote the first draft of the review with CHERG Review Groups on Intervention Effects. Standards for

CHERG reviews of intervention effects on child survival.

substantial input from JKD. NW and AR contributed to the lives saved

Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39 (suppl 1): i21–31.

estimates in the Lives Saved Tool (LiST). IF and NW contributed

14 Bhutta ZA, Ahmed T, Black RE, et al. What works? Interventions for

estimates for costs with LiST.

maternal and child undernutrition and survival. Lancet 2008;

The Lancet Diarrhoea and Pneumonia Interventions Study Group 371: 417–40.

Zulfiqar A Bhutta, Jai K Das, Rehana A Salam, Zohra Lassi (Aga Khan 15 Bhutta ZA, Shekar M, Ahmed T. Mainstreaming interventions in

University, Pakistan); Robert E Black, Neff Walker, Ingrid Friberg the health sector to address maternal and child undernutrition.

(Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, USA); Matern Child Nutr 2008; 4 (suppl 1): 1–4.

www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013 1427

Series

16 Bhutta ZA, Ali S, Cousens S, et al. Alma-Ata: Rebirth and Revision 39 Das JK, Ali A, Salam RA, Bhutta ZA. Antibiotics for the treatment

6 Interventions to address maternal, newborn, and child survival: of Cholera, Shigella and Cryptosporidium in children. BMCPH

what difference can integrated primary health care strategies make? (in press).

Lancet 2008; 372: 972–89. 40 Cunliffe NA, Witte D, Ngwira BM, et al. Efficacy of human rotavirus

17 Darmstadt GL, Bhutta ZA, Cousens S, Adam T, Walker N, vaccine against severe gastroenteritis in Malawian children in the

de Bernis L, for the Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. first two years of life: a randomized, double-blind, placebo

Evidence-based, cost-effective interventions: how many newborn controlled trial. Vaccine 2012; 30 (suppl 1): A36–43.

babies can we save? Lancet 2005; 365: 977–88. 41 Sow SO, Tapia M, Haidara FC, et al. Efficacy of the oral pentavalent

18 Kerber KJ, de Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, Okong P, Starrs A, rotavirus vaccine in Mali. Vaccine 2012; 30 (suppl 1): A71–78.

Lawn JE. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child 42 Piarroux R, Barrais R, Faucher B, et al. Understanding the cholera

health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet 2007; 370: 1358–69. epidemic, Haiti. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17: 1161–68.

19 Imdad A, Bhutta ZA. Nutritional management of the low birth 43 Ali M, Emch M, von Seidlein L, et al. Herd immunity conferred by

weight/preterm infant in community settings: a perspective from killed oral cholera vaccines in Bangladesh: a reanalysis. Lancet 2005;

the developing world. J Pediatr 2013; 162 (3 suppl): S107–14. 366: 44–49.

20 Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS; Bellagio 44 Longini IM Jr, Nizam A, Ali M, Yunus M, Shenvi N, Clemens JD.

Child Survival Study Group. How many child deaths can we prevent Controlling endemic cholera with oral vaccines. PLoS Med 2007;

this year? Lancet 2003: 362: 65–67. 4: e336.

21 Victora CG, Barros AJ, Axelson H, et al. How changes in coverage 45 Traa BS, Walker CL, Munos M, Black RE. Antibiotics for the

affect equity in maternal and child health interventions in treatment of dysentery in children. Int J Epidemiol 2010;

35 Countdown to 2015 countries: an analysis of national surveys. 39 (suppl 1): i70–74.

Lancet 2012; 380: 1149–56. 46 Kabir I, Khan WA, Haider R, Mitra AK, Alam AN. Erythromycin

22 Barros FC, Bhutta ZA, Batra M, Hansen TN, Victora CG, Rubens CE. and trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole in the treatment of cholera in

Global report on preterm birth and stillbirth (3 of 7): evidence for children. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res 1996; 14: 243–47.

effectiveness of interventions. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2010; 47 Roy SK, Islam A, Ali R, et al. A randomized clinical trial to compare

10 (suppl 1): S3. the efficacy of erythromycin, ampicillin and tetracycline for the

23 UNICEF. Diarrhoea: why children are dying and what can be done. treatment of cholera in children. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1998;

New York: UNICEF, 2009. 92: 460–62.

24 WHO. Global action plan for the prevention and control of 48 Zimbabwe, Bangladesh, South Africa (Zimbasa) Dysentery Study

pneumonia in children aged under 5 years. Wkly Epidemiol Rec Group. Multicenter, randomized, double blind clinical trial of short

2009; 84: 451–52. course versus standard course oral ciprofloxacin for Shigella

25 UNICEF. Pneumonia and diarrhoea: tackling the deadliest diseases dysenteriae type 1 dysentery in children. Pediatr Infect Dis J 2002;

for the world’s poorest children. New York: UNICEF, 2012. 21: 1136–41.

26 WHO. The optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding: results of a 49 Alam AN, Islam MR, Hossain MS, Mahalanabis D, Hye HK.

WHO systematic review. Indian Pediatr 2001; 38: 565–67. Comparison of pivmecillinam and nalidixic acid in the treatment

27 Lamberti L, Walker CF, Noiman A, Victora C, Black R. of acute shigellosis in children. Scand J Gastroenterol 1994;

Breastfeeding and the risk for diarrhea morbidity and mortality. 29: 313–17.

BMC Public Health 2011; 11 (suppl 3): S15. 50 Salam MA, Dhar U, Khan WA, Bennish ML. Randomised

28 Haroon S, Das JK, Salam RA, Imdad A, Bhutta ZA. Breastfeeding comparison of ciprofloxacin suspension and pivmecillinam for

promotion interventions and breastfeeding practices: a systematic childhood shigellosis. Lancet 1998; 352: 522–27.

review. BMCPH (in press). 51 Varsano I, Eidlitz-Marcus T, Nussinovitch M, Elian I. Comparative

29 Cairncross S, Hunt C, Boisson S, et al. Water, sanitation and efficacy of ceftriaxone and ampicillin for treatment of severe

hygiene for the prevention of diarrhoea. Int J Epidemiol 2010; shigellosis in children. J Pediatr 1991; 118: 627–32.

39 (suppl 1): i193–205. 52 Amadi B, Mwiya M, Musuku J, et al. Effect of nitazoxanide on

30 Yakoob MY, Theodoratou E, Jabeen A, et al. Preventive zinc morbidity and mortality in Zambian children with cryptosporidiosis:

supplementation in developing countries: impact on mortality and a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002; 360: 1375–80.

morbidity due to diarrhea, pneumonia and malaria. 53 Rossignol JF, Ayoub A, Ayers MS. Treatment of diarrhea caused by

BMC Public Health 2011; 11 (suppl 3): S23. Cryptosporidium parvum: a prospective randomized, double-blind,

31 WHO. Guidelines on HIV and infant feeding 2010. Principles and placebo-controlled study of Nitazoxanide. J Infect Dis 2001;

recommendations for infant feeding in the context of HIV and a 184: 103–06.

summary of evidence. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/ 54 Wittenberg DF, Miller NM, van den Ende J. Spiramycin is not

9789241599535_eng.pdf (accessed March 18, 2013). effective in treating cryptosporidium diarrhea in infants: results of a

32 Waddington H, Snilstveit B, White H, Fewtrell L. Water, sanitation double-blind randomized trial. J Infect Dis 1989; 159: 131–32.

and hygiene interventions to combat childhood diarrhoea in 55 Gu B, Cao Y, Pan S, et al. Comparison of the prevalence and

developing countries. New Delhi: International Initiative for Impact changing resistance to nalidixic acid and ciprofloxacin of Shigella

Evaluation, 2009. between Europe-America and Asia-Africa from 1998 to 2009.

33 Wessells KR, Brown KH. Estimating the global prevalence of Int J Antimicrob Agents 2012; 40: 9–17.

zinc deficiency: results based on zinc availability in national food 56 Sudfeld CR, Navar AM, Halsey NA. Effectiveness of measles

supplies and the prevalence of stunting. PLoS One 2012; vaccination and vitamin A treatment. Int J Epidemiol 2010;

7: e50568. 39 (suppl 1): i48–55.

34 Munos MK, Walker CLF, Black RE. The effect of rotavirus vaccine 57 Theodoratou E, Johnson S, Jhass A, et al. The effect of

on diarrhoea mortality. Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39 (suppl 1): i56–62. Haemophilus influenzae type b and pneumococcal conjugate

35 Das JK, Tripathy A, Hassan A, Ali A, Dojosoeandy C, Bhutta ZA. vaccines on childhood pneumonia incidence, severe morbidity and

Vaccines for the prevention of diarrhea due to cholera, shigella, mortality. Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39 (suppl 1): i172–85.

ETEC and rotavirus. BMCPH (in press). 58 Zaidi AKM, Ganatra HA, Syed S, et al. Effect of case management

36 Munos MK, Walker CL, Black RE. The effect of oral rehydration on neonatal mortality due to sepsis and pneumonia.

solution and recommended home fluids on diarrhoea mortality. BMC Public Health 2011; 11 (suppl 3): S13.

Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39 (suppl 1): i75–87. 59 Duke T, Wandi F, Jonathan M, et al. Improved oxygen systems for

37 Walker CLF, Black RE. Zinc for the treatment of diarrhoea: effect on childhood pneumonia: a multihospital effectiveness study in Papua

diarrhoea morbidity, mortality and incidence of future episodes. New Guinea. Lancet 2008; 372: 1328–33.

Int J Epidemiol 2010; 39 (suppl 1): i63–69. 60 Bhutta ZA, Zaidi AKM, Thaver D, Humayun Q, Ali S, Darmstadt GL.

38 Gaffey MF, Wazny K, Bassani DG, Bhutta ZA. Dietary management Management of newborn infections in primary care settings:

of childhood diarrhea in low- and middle-income countries: a review of the evidence and implications for policy?

a systematic review. BMCPH (in press). Pediatr Infect Dis J 2009; 28 (suppl): S22–30.

1428 www.thelancet.com Vol 381 April 20, 2013

Series

61 Punpanich W, Groome M, Muhe L, Qazi SA, Madhi SA. Systematic 77 Bruce N, Dherani M, Das JK, et al. Control of household air

review on the etiology and antibiotic treatment of pneumonia in pollution for child survival: estimates for intervention impacts.