International Society of Nephrology 0 by 25 Project: Lessons Learned

International Society of Nephrology 0 by 25 Project: Lessons Learned

Uploaded by

LilisCopyright:

Available Formats

International Society of Nephrology 0 by 25 Project: Lessons Learned

International Society of Nephrology 0 by 25 Project: Lessons Learned

Uploaded by

LilisOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

International Society of Nephrology 0 by 25 Project: Lessons Learned

International Society of Nephrology 0 by 25 Project: Lessons Learned

Uploaded by

LilisCopyright:

Available Formats

Safe Water and Healthy Hydration

Ann Nutr Metab 2019;74(suppl 3):45–50 Published online: June 14, 2019

DOI: 10.1159/000500345

International Society of Nephrology 0 by

25 Project: Lessons Learned

Etienne Macedo a Guillermo Garcia-Garcia b Ravindra L. Mehta a

Michael V. Rocco c

a Department of Medicine, University of California San Diego, San Diego, CA, USA; b Nephrology Service, Hospital

Civil de Guadalajara Fray Antonio Alcalde, University of Guadalajara Health Sciences Center, Guadalajara, Mexico;

c Wake Forest School of Medicine, Medicine, Winston-Salem, NC, USA

Keywords J Am Soc Nephrol 2017]. In this review, we will comment on

Acute kidney injury · Dehydration · Mortality · Epidemiology the main findings and lessons learned from the 0 by 25 ini-

tiative. © 2019 The Author(s)

Published by S. Karger AG, Basel

Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common disorder with a high

risk of mortality and development of chronic kidney disease.

With the validation of the recent classification systems, RI- Introduction of 0 by 25 Projects

FLE in 2004 and KDIGO, in use today, our understanding of

AKI has evolved. We now know that community-acquired The worldwide application of the RIFLE/AKIN (Risk,

AKI is also associated with an increased risk of worse out- Injury, Failure, Loss of kidney function, and End-stage

comes. In addition, several epidemiological studies, includ- kidney disease/Acute Kidney Injury Network) and KDI-

ing cohorts from low-income and low-middle income coun- GO (Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes) clas-

tries, have confirmed common risk factors for community- sification systems has confirmed the increasing incidence

acquired AKI. In 2013, the International Society of of AKI in different settings [5–9]. The efforts of nephrology

Nephrology launched the 0 by 25 campaign with the goal and critical care societies to create a unified classification

that no patient should die from preventable or untreated system have enabled comparisons of AKI incidence and

AKI in low-resource areas by 2025 [Mehta et al.: Lancet 2015; outcomes across diverse populations. The resultant epide-

385:2616–43]. The initial effort of the initiative was a meta- miological studies have shown increasing severity of AKI

analysis of AKI epidemiology around the world. The second cases and a higher risk of death associated with AKI, in both

project of the 0 by 25 initiative, the Global AKI Snapshot hospital and community settings [10–12]. In addition, AKI

(GSN) study, provided insights into the recognition, treat- is now a recognized important risk factor for new-onset

ment, and outcomes of AKI worldwide [Mehta et al.: Lancet chronic kidney disease (CKD), determining acceleration in

2016; 387: 2017–25]. Following the GSN, a Pilot Project was the progression to end-stage renal disease [13–15].

designed to test whether education and a simple protocol- The International Society of Nephrology (ISN) 0 by 25

based approach can improve outcomes in patients at risk of initiative aims to eliminate or at least reduce avoidable

community-acquired AKI in low-resource settings [Macedo: AKI-related deaths around the world by 2025 [1]. Two key

© 2019 The Author(s) Etienne Macedo

Published by S. Karger AG, Basel Department of Medicine

University of California San Diego

E-Mail karger@karger.com This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-

NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (CC BY- 9500 Gilman Dr, La Jolla, CA 92093 (USA)

www.karger.com/anm E-Mail emmacedo @ ucsd.edu

NC-ND) (http://www.karger.com/Services/OpenAccessLicense).

Usage and distribution for commercial purposes as well as any dis-

tribution of modified material requires written permission.

points were essential for the initiative: defining preventable initions, plus 266 papers based on KDIGO or equivalent

death from AKI and promoting local recommendations AKI definitions, were analyzed [1]. The pooled incidence

for AKI care considering the health-care infrastructure rate by KDIGO stage in 266 studies (4,502,158 subjects)

and socioeconomic conditions [1, 16–19]. Based on previ- showed an overall rate of 20.9% of hospital admissions and

ous studies, preventable deaths from AKI are known to affected 3,000–5,000 patients per 1 million population per

occur as a result of 3 different situations [1]: (1) secondary year. Recent studies have described an incidence as high as

to public health problems such as unclean water, diarrhea, 15,000 per 1 million population per year. The data from

and endemic infections; (2) delayed or lack of recognition, these studies showed that the mortality rates continue to

lack of access to laboratory studies, inadequate response, be high in all regions and that there was a continued asso-

or iatrogenic factors resulting in additional insults to a fail- ciation of nonrenal recovery following AKI.

ing kidney; and (3) lack of dialysis support to treat life- Nevertheless, AKI incidence in low-middle income

threatening hyperkalemia, fluid overload, and acidosis [1]. countries (LMICs) is still uncertain as some studies have

Although knowledge of the epidemiology of AKI has im- shown lower levels than in high-income countries (HICs).

proved immensely since the use of a standardized AKI clas- It is likely that underreporting is the most common rea-

sification system, few studies have focused on community- son for the discrepancy when comparing HICs and com-

acquired AKI in low-resource settings. In the meta-analysis bined low-incomes plus LMIC. In addition, epidemiolog-

by the 0 by 25 initiative, the main issues regarding the epi- ical data from LMICs are difficult to interpret as there are

demiology of AKI were raised [1]. Information was pre- nonuniform cohorts and involve heterogeneous methods

sented regarding the increasing associated mortality of even of reporting as well as wide variations in ability to diag-

mild AKI, the effects of an AKI episode on long-term out- nose and treat AKI [1].

comes, and early detection and treatment of AKI in outpa- Another factor to consider is the high incidence of AKI

tient and low-resource settings. However, to reduce AKI- in the hospital settings of areas with more resources, in

related mortality and morbidity, knowledge of the factors contrast to community hospitals and rural areas, where

that affect AKI outcomes is a key step in implementing ini- AKI is often not detected [8, 19, 22–26]. Nonetheless, AKI

tiatives. The strategies to reduce the burden of AKI need to in this population is often preventable and reversible, af-

be based on the identification of patients at risk, implemen- fecting young, previously healthy individuals and might be

tation of preventive actions, application of diagnostic meth- secondary to tropical infectious diseases, animal venoms,

ods, and timely referral for specialist care [20, 21]. Develop- the use of herbal medicine, complications of pregnancy in-

ment of educational and training tools for raising awareness cluding septic abortion, and infectious diarrhea (Table 1).

and standardizing care of AKI cases is also essential.

As most studies on AKI are derived from developed

countries and mainly focus on ICU populations, the 0 by 25 GBD Study

initiative developed 2 projects to assess how AKI contrib-

utes to the global burden of health loss: the Global AKI Snap- The Global Burden of Disease (GBD) Study is an effort

shot (GSN) study, and the Pilot Study. The GSN study was of the World Health Organization to quantify leading

a prospective multinational cross-sectional project that in- causes of health loss secondary to illness or injury through-

cluded all patients with AKI who presented to the participat- out the world [27]. The GBD Study categorizes causes of

ing physicians on a given index day in 2014 [2]. The study health loss by age, sex, and geography for a specific time

included 4,018 patients with AKI across 6 continents and 72 point. This time-based measure combines years of life lost

countries. The Pilot Study is a prospective cohort of patients due to premature mortality (YLL) and years of life lost

with high risk for community-acquired AKI in 3 different due to time lived in states of less than full health (DALY).

countries [3, 4]. The following paragraphs will comment on The DALY metric was developed in the original GBD

the main findings from the 0 by 25 initiative so far. 1990 study to assess the burden of disease consistently

across diseases, risk factors, and regions.

As a part of the 0 by 25 initiative, the ISN has collabo-

AKI Meta-Analysis rated with the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation

that coordinates the GBD study to include AKI in future

A systematic search of the literature was performed, in- GBD reports. Incorporating AKI into the GBD will in-

cluding papers from January 2012 to August 2014. Four volve determining the relationship between AKI as an in-

hundred and ninety-nine papers that included all AKI def- termediate event associated with disability or death. It

46 Ann Nutr Metab 2019;74(suppl 3):45–50 Macedo/Garcia-Garcia/Mehta/Rocco

DOI: 10.1159/000500345

Table 1. Main risk factors for developing AKI

Patient Exposures

nonmodifiable modifiable environmental infrastructure

Comorbid medical conditions Dehydration Diarrhea Inadequate sanitation

Chronic kidney disease Intravascular volume Obstetric complications (including Limited clean water availability

Diabetes mellitus depletion septic absorption) Inadequate control of parasites

Cancer Hypotension Infectious diseases (malaria, Inadequate control of

Chronic heart disease Anemia leptospirosis, dengue, cholera, infection-carrying vectors

Chronic lung disease Hypoxia yellow fever, tetanus, Hantavirus) Poor transportation

Chronic gastrointestinal Use of nephrotoxic Animal venoms (snakes, bees and Inadequate health budget

disease agents (antibiotics, wasps, Loxosceles spiders, Lonomia Insufficient health care human

Demographic factors iodinated contrast, caterpillars) resources

Gender nonsteroidal Natural medicines Insufficient health services and

Older age anti-inflammatory drugs, Natural dyes hospitals

anticancer drugs, Prolonged physically overwhelming

antiretroviral, work in an unhealthy environment

calcineurin blockers)

Modified from [1].

AKI, acute kidney injury.

will be possible to follow the leading causes of AKI and munity. Most patients (46%) were at the ward or step-

the segments of the population most susceptible to AKI- down unit when AKI diagnosis occurred, with similar

related health loss. The main goal is to add strength to the rates across all country categories. Eighty percent of the

concept that a high proportion of cases of AKI in the com- cases were considered de novo AKI.

munity setting of low resource areas are preventable; it Hypotension/shock and dehydration were the more

also attempts to demonstrate that investment toward ear- frequent risk factors associated with AKI development.

ly recognition can be translated into reduce mortality and In HIC and UMIC, hypotension/shock was the most

improve outcomes. prevalent cause, whereas dehydration was the most fre-

In order to enable the inclusion of AKI in GBD, the ISN quent contributory factor for the development of AKI in

0 by 25 initiative helped to generate AKI epidemiological LMIC. Most dehydration episodes were associated with

data at the population level. The 0 by 25 initiative enabled inadequate oral intake (60%), followed by vomiting

the AKI Global Snapshot, a prospective observational co- (44%).

hort study, to compare risk factors, etiologies, diagnoses, Patients with stage 3 AKI were higher in LMICs than

management, and outcomes of AKI. The study was con- in HICs and UMICs (58 vs. 47 and 41%, respectively).

ducted from September 29, 2014, to December 7, 2014, However, more patients in LMICs experienced recovery

with over 600 participating centers in over 93 countries [2]. from AKI than did patients from HICs and UMICs. The

Patients were classified as having community-acquired large proportion of patients presenting with stage 3 AKI

AKI if they presented with AKI and hospital-acquired AKI has important implications.

if they developed it in the hospital setting. Patients were In a separate analysis of children, the main factors as-

considered as de novo AKI, AKI on CKD, or AKI with un- sociated with AKI in HIC were hypotension (30%), post-

known prior kidney history if a baseline creatinine was not surgical complications (27%), and dehydration (26%). In

known. Countries were classified into HICs, upper-mid- contrast, dehydration was the most common etiologic

dle-income countries (UMICs), and LMICs according to factor in LMIC (43.5%) and UMIC (30.6%) [9].

their 2014 gross national income per person, using thresh- Mortality rate varied from 11.45% in patients from

olds defined by the World Bank Atlas method [28]. LMIC to 13.6% in patients from UMIC. In pediatric pa-

Overall, community-acquired AKI was more frequent tients, the mortality rate was significantly different

than hospital-acquired AKI, and the difference was great- (19.6%) in LMIC compared to 1.2% in HIC [9]. Mortality

er in LMIC, where 79% of AKI cases occurred in the com- in community-acquired AKI was higher in LMIC (11%)

ISN 0 by 25 Project: Lessons Learned Ann Nutr Metab 2019;74(suppl 3):45–50 47

DOI: 10.1159/000500345

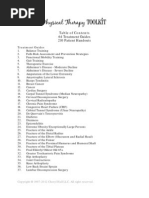

Risk

Identifying high-risk individuals for primary

prevention of AKI

• Use of risk scores to predict risk of AKI

• Identification of modifiable risk factors

Rehabilitation

Post-discharge care of AKI

patients Recognition

• Follow-up of kidney Prompt diagnosis

function • Early and sequential sCr and UO

• Educational campaigns on assessment

the importance of • Availability of point of care tests

long-term follow-up and diagnostic tools

Response

Interventions for incipient and established

Renal support AKI

Renal replacement therapy in AKI • Use of protocol-based management of

• Timely intervention with RRT hemodynamic and fluid status

• Education and training of personnel • Avoidance of nephrotoxic drugs

for peritoneal dialysis • Appropriate drug dose adjustment for

kidney function

Fig. 1. ISN AKI 0 by 25 key elements for a sustainable infrastructure to support AKI care. sCr, serum creatinine;

RRT, renal replacement therapy; UO, urine output; AKI, acute kidney injury. Modified from [1].

vs. 9% in HIC. In the pediatric population, this difference bility of implementing an education and training pro-

was even more pronounced, 3% in HIC and 20% in LMIC. gram to optimize care of AKI, based on a protocol-driv-

In LMIC, mortality was higher among ICU patients (21%) en approach in rural areas. The Pilot feasibility study

in comparison to HIC (13%). AKI recovery was more of- was conducted at 3 sites located in Asia (Dharan, Ne-

ten complete in LMIC (39%) than in HIC (33%) or UMIC pal), Africa (Blantyre, Malawi), and Latin America (Co-

(28%). Recovery rates from community vs. acquired AKI chabamba, Bolivia). Each site comprised a health-care

were very similar in HIC and UMIC. In LMIC, the recov- cluster (including 3–4 community health centers, 1 dis-

ery occurred in 79% of patients with community-ac- trict hospital, 1 regional referral hospital) that provided

quired AKI and in only 20% of patients with hospital- services to the population around the site area. The

acquired AKI. study was approved by the Institutional Review Board

The results of the GSN underline the need to raise and the Ethics Committee of University of California

awareness of AKI to increase the detection of patients San Diego and by the 3 local sites. Patients were screened

who present with earlier stages of AKI. It also indicates for signs or symptoms a priori associated with high/

that the main causes of AKI in LMICs are dehydration, moderate risk of developing AKI. AKI was confirmed

infection, and sepsis. within 7 days by a serum creatinine concentration in-

crease or decrease of 0.3 mg/dL, or 1.5 times from the

reference value.

Pilot Study The results of the pilot study, soon to be published, will

provide an assessment of the current approach to diagno-

In the GSN study [2], we were able to demonstrate sis and management of AKI in community health centers

that there are significant similarities in the risk factors and will identify barriers to optimize care of these pa-

and causes of AKI worldwide; however, there was an tients. It will demonstrate the effect of simple interven-

underrepresentation of community-acquired AKI, par- tions, including education and provision of point-of-care

ticularly in rural settings. The primary aim of the 0 by tests, on the course and outcomes of patients with a high

25 AKI Pilot Feasibility Project was to assess the feasi- risk of developing AKI. As a part of the project, we devel-

48 Ann Nutr Metab 2019;74(suppl 3):45–50 Macedo/Garcia-Garcia/Mehta/Rocco

DOI: 10.1159/000500345

oped partnerships with the governments of the partici- training of health-care personnel is fundamental to

pating countries to establish the best approaches to de- achieve increased awareness and better care delivery in

crease preventable deaths from AKI. AKI. Additional key elements include improvement in

health care and diagnostic tool availability and provision

of acute renal replacement therapy for those in need. The

Next Steps worldwide heterogeneity in the cause, setting, and course

of AKI demands an integrative approach. The 0 by 25 ini-

AKI has been associated with high mortality rates; tiative proposed the utilization of the 5R framework: Risk

however, it is likely that a significant number of deaths assessment, Recognition, Response, Renal support, and

associated with AKI could be avoided. In addition, AKI is Rehabilitation (Fig. 1) [1, 30].

now a recognized important risk factor for new-onset Furthermore, this initiative is enabling the develop-

CKD, determining acceleration in progression to end- ment of sustainable infrastructure to improve education,

stage renal disease, leading to poor quality of life, disabil- training, care delivery, and implementation of diagnostic

ity, and long-term costs [29]. The Global Snapshot was and intervention studies. It provided evidence suggesting

the first large, epidemiologic study to map and scale the that the majority of AKI cases would be treatable and of-

outcomes associated with AKI around the world, includ- ten reversible, with early identification in high-risk pa-

ing data from ICU and non-ICU patients. It provided a tients and implementation of basic treatment.

solid basis to direct efforts for the ambitious goal of zero

deaths from AKI by 2025.

The ISN 0 by 25 initiative offers a critical opportunity Disclosure Statement

to help improve education, training, care delivery, and E.M., G.G.-G., and M.R. received travel expenses and registration

the implementation of diagnostic and intervention stud- fee from Danone Research to participate in the 2018 Hydration for

ies in AKI. A comprehensive approach for education and Health Scientific Conference. R.L.M. has nothing to disclose.

References

1 Mehta RL, Cerdá J, Burdmann EA, Tonelli M, 6 Sawhney S, Fluck N, Fraser SD, Marks A, veloping country. Clin Nephrol. 2012 Dec;

García-García G, Jha V, et al. International Prescott GJ, Roderick PJ, et al. KDIGO-based 78(6):449–55.

Society of Nephrology’s 0by25 initiative for acute kidney injury criteria operate different- 12 Susantitaphong P, Cruz DN, Cerda J, Abulfar-

acute kidney injury (zero preventable deaths ly in hospitals and the community-findings aj M, Alqahtani F, Koulouridis I, et al.; Acute

by 2025): a human rights case for nephrology. from a large population cohort. Nephrol Dial Kidney Injury Advisory Group of the Ameri-

Lancet. 2015 Jun;385(9987):2616–43. Transplant. 2016 Jun;31(6):922–9. can Society of Nephrology. World incidence

2 Mehta RL, Burdmann EA, Cerdá J, Feehally J, 7 Hoste EA, Kellum JA, Selby NM, Zarbock A, of AKI: a meta-analysis. Clin J Am Soc

Finkelstein F, García-García G, et al. Recogni- Palevsky PM, Bagshaw SM, et al. Global epide- Nephrol. 2013 Sep;8(9):1482–93.

tion and management of acute kidney injury miology and outcomes of acute kidney injury. 13 Chawla LS, Kimmel PL. Acute kidney injury

in the International Society of Nephrology Nat Rev Nephrol. 2018 Oct;14(10):607–25. and chronic kidney disease: an integrated

0by25 Global Snapshot: a multinational 8 Hsu CN, Chen HL, Tain YL. Epidemiology clinical syndrome. Kidney Int. 2012 Sep;

cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2016 May; and outcomes of community-acquired and 82(5):516–24.

387(10032):2017–25. hospital-acquired acute kidney injury in chil- 14 Coca SG. Long-term outcomes of acute kid-

3 Macedo E. Use of a serum creatinine point of dren and adolescents. Pediatr Res. 2018 Mar; ney injury. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens.

care test in low resource settings: correlation 83(3):622–9. 2010 May;19(3):266–72.

and agreement with hospital based assess- 9 Macedo E, Cerdá J, Hingorani S, Hou J, Bagga 15 Coca SG, Singanamala S, Parikh CR. Chronic

ment. In: Sharma S, Hemmila U, Claure-Del A, Burdmann EA, et al. Recognition and man- kidney disease after acute kidney injury: a sys-

Granado R, Cerda J, Burdmann EA, Rocco M, agement of acute kidney injury in children: tematic review and meta-analysis. Kidney Int.

et al., editors. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017. p. 415. the ISN 0by25 Global Snapshot study. PLoS 2012 Mar;81(5):442–8.

4 Macedo E. Spectrum of AKI in Patients from One. 2018 May;13(5):e0196586. 16 Yang L, Xing G, Wang L, Wu Y, Li S, Xu G, et

Low Income Countries Participating in the 10 Coca SG, Yusuf B, Shlipak MG, Garg AX, al.; ISN AKF 0by25 China Consortiums. Acute

ISN0by25 Initiative. In: Sharma KS, editor. J Parikh CR. Long-term risk of mortality and kidney injury in China: a cross-sectional sur-

Am Soc Nephrol – Abstract Supplement; Oc- other adverse outcomes after acute kidney in- vey. Lancet. 2015 Oct;386(10002):1465–71.

tober 2017. jury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. 17 Feehally J. The ISN 0by25 Global Snapshot

5 Mesropian PD, Othersen J, Mason D, Wang Am J Kidney Dis. 2009 Jun;53(6):961–73. Study. Ann Nutr Metab. 2016; 68(Suppl 2):

J, Asif A, Mathew RO. Community-acquired 11 Daher EF, Silva Junior GB, Santos SQ, R Be- 29–31.

acute kidney injury: A challenge and oppor- zerra CC, Diniz EJ, Lima RS, et al. Differences 18 Perico N, Remuzzi G. Prevention programs

tunity for primary care in kidney health. in community, hospital and intensive care for chronic kidney disease in low-income

Nephrology (Carlton). 2016 Sep; 21(9): 729– unit-acquired acute kidney injury: observa- countries. Intern Emerg Med. 2016 Apr;

35. tional study in a nephrology service of a de- 11(3):385–9.

ISN 0 by 25 Project: Lessons Learned Ann Nutr Metab 2019;74(suppl 3):45–50 49

DOI: 10.1159/000500345

19 Wang Y, Wang J, Su T, Qu Z, Zhao M, Yang 23 Emmett L, Tollitt J, McCorkindale S, Sinha S, 27 Murray CJ, Ezzati M, Flaxman AD, Lim S, Lo-

L, et al.; ISN AKF 0by25 China Consortium. Poulikakos D. The Evidence of Acute Kidney zano R, Michaud C, et al. GBD 2010: design,

Community-Acquired Acute Kidney Injury: Injury in the Community and for Primary definitions, and metrics. Lancet. 2012 Dec;

A Nationwide Survey in China. Am J Kidney Care Interventions. Nephron. 2017; 136(3): 380(9859):2063–6.

Dis. 2017 May;69(5):647–57. 202–10. 28 World Bank. GNI per capita, Atlas method

20 Chawla LS, Amdur RL, Shaw AD, Faselis C, 24 Holmes J, Geen J, Phillips B, Williams JD, (current US$) [cited April 2015]. Available

Palant CE, Kimmel PL. Association be- Phillips AO, Welsh AKI Steering Group. from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/

tween AKI and long-term renal and cardio- Community acquired acute kidney injury: ny.gnp.pcap.cd.

vascular outcomes in United States veterans. findings from a large population cohort. 29 Sawhney S, Marks A, Fluck N, Levin A,

Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014 Mar; 9(3): 448– QJM. 2017 Nov;110(11):741–6. McLernon D, Prescott G, et al. Post-discharge

56. 25 Inokuchi R, Hara Y, Yasuda H, Itami N, Tera- kidney function is associated with subsequent

21 Leung KC, Tonelli M, James MT. Chronic da Y, Doi K. Differences in characteristics and ten-year renal progression risk among survi-

kidney disease following acute kidney injury- outcomes between community- and hospital- vors of acute kidney injury. Kidney Int. 2017

risk and outcomes. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2013 acquired acute kidney injury: A systematic re- Aug;92(2):440–52.

Feb;9(2):77–85. view and meta-analysis. Clin Nephrol. 2017 30 Lewington AJ, Cerdá J, Mehta RL. Raising

22 Jha V, Chugh KS. Community-acquired acute Oct;88(10):167–82. awareness of acute kidney injury: a global per-

kidney injury in Asia. Semin Nephrol. 2008 26 Bernardo EO, Cruz AT, Buffone GJ, Devaraj spective of a silent killer. Kidney Int. 2013 Sep;

Jul;28(4):330–47. S, Loftis LL, Arikan AA. Community-ac- 84(3):457–67.

quired Acute Kidney Injury Among Children

Seen in the Pediatric Emergency Department.

Acad Emerg Med. 2018 Jul;25(7):758–68.

50 Ann Nutr Metab 2019;74(suppl 3):45–50 Macedo/Garcia-Garcia/Mehta/Rocco

DOI: 10.1159/000500345

You might also like

- University of Makati College of Allied Health Studies Center of Graduate and New ProgramsDocument47 pagesUniversity of Makati College of Allied Health Studies Center of Graduate and New ProgramsAina HaravataNo ratings yet

- Osce Cranial Nerves PDFDocument42 pagesOsce Cranial Nerves PDFriczen vilaNo ratings yet

- Medication: Expected Pharmacological Action Therapeutic UseDocument1 pageMedication: Expected Pharmacological Action Therapeutic UseMike EveretteNo ratings yet

- Infections and KidneyDocument17 pagesInfections and Kidneybc8d9yjzt2No ratings yet

- Paper - Improving The Cascade of Global Tuberculosis Care Moving From What To How Harvard 2019Document7 pagesPaper - Improving The Cascade of Global Tuberculosis Care Moving From What To How Harvard 2019HARY HARDIAN PUTRANo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Kidney Injury in PediatricsDocument13 pagesDiagnosis and Treatment of Acute Kidney Injury in PediatricsagungNo ratings yet

- Clinical Characteristics, Sepsis Interventions and ObesityDocument13 pagesClinical Characteristics, Sepsis Interventions and ObesityMatheusNo ratings yet

- 645 FullDocument8 pages645 FullCarrie Joy DecalanNo ratings yet

- Profilaxis Strepto 2022 IDSADocument17 pagesProfilaxis Strepto 2022 IDSAisabelitamanceraNo ratings yet

- Chelsey (Chapter 2 RRL) LocalDocument3 pagesChelsey (Chapter 2 RRL) LocalChester ArenasNo ratings yet

- Diverticulitis 2021 UptodateDocument23 pagesDiverticulitis 2021 UptodateEgdar Allan PoeNo ratings yet

- Acp Statement On Global Covid-19 Vaccine Distribution and Allocation On Being Ethical and Practical 2021Document3 pagesAcp Statement On Global Covid-19 Vaccine Distribution and Allocation On Being Ethical and Practical 2021Suleymen Abdureman OmerNo ratings yet

- JournalDocument6 pagesJournalAngel ViolaNo ratings yet

- Erc Adulto MayorDocument4 pagesErc Adulto MayorMario Ivan De la Cruz LaraNo ratings yet

- 2013 - Bhutta - Lancet - InterventionsDocument13 pages2013 - Bhutta - Lancet - InterventionsnomdeplumNo ratings yet

- Mendelson-Optimising Blood Cultures - SAMJ June 2022Document2 pagesMendelson-Optimising Blood Cultures - SAMJ June 2022Phoun PhornNo ratings yet

- GA HS 3311 Unit 4(1)Document8 pagesGA HS 3311 Unit 4(1)Elizee -aNo ratings yet

- Acute Kidney InjuryDocument15 pagesAcute Kidney InjuryManish VijayNo ratings yet

- Djaa 048Document17 pagesDjaa 048Satra Azmia HerlandaNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 2589537019301877Document2 pagesPi Is 2589537019301877prince BoadiNo ratings yet

- Paper 2-1Document16 pagesPaper 2-1shilohNo ratings yet

- Surviving Sepsis: Going Beyond The Guidelines: Review Open AccessDocument6 pagesSurviving Sepsis: Going Beyond The Guidelines: Review Open AccessTasya Arsy LiyanaNo ratings yet

- Assess the Knowledge Regarding Care of Patients Diagnosed With Chronic Kidney Disease Among Nursing Officers in KolarDocument5 pagesAssess the Knowledge Regarding Care of Patients Diagnosed With Chronic Kidney Disease Among Nursing Officers in KolarBIOMEDSCIDIRECT PUBLICATIONSNo ratings yet

- J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle - 2022 - Paval - A Systematic Review Examining The Relationship Between Cytokines and CachexiaDocument15 pagesJ Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle - 2022 - Paval - A Systematic Review Examining The Relationship Between Cytokines and CachexiaYohana Elisabeth GultomNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive-care-for-all-individuals-with-tubercDocument2 pagesComprehensive-care-for-all-individuals-with-tubercelitepakistani34No ratings yet

- Two Decades of Diabetes Prevention EffortsDocument9 pagesTwo Decades of Diabetes Prevention EffortsKarem CarrionNo ratings yet

- 2016 - Article - AbstractsForThe17thIPNACongres UrotomografiaDocument219 pages2016 - Article - AbstractsForThe17thIPNACongres UrotomografialeydyNo ratings yet

- A Critical Assessment of Vector Control For Dengue Prevention-PRINTEDDocument26 pagesA Critical Assessment of Vector Control For Dengue Prevention-PRINTEDNg Kin HoongNo ratings yet

- Cancers 14 02230 v2Document12 pagesCancers 14 02230 v2bisak.j.adelaNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Towards COVID 19 Among People Living With HIV/AIDS in Kigali, RwandaDocument6 pagesKnowledge, Attitude, and Practice Towards COVID 19 Among People Living With HIV/AIDS in Kigali, RwandamadawiNo ratings yet

- Rapid Systematic Review of Interventions To Improve Antenatal Screening RatesDocument24 pagesRapid Systematic Review of Interventions To Improve Antenatal Screening Ratesayu2007No ratings yet

- Cost InfluenzaDocument11 pagesCost InfluenzacasteltenNo ratings yet

- Does Mass Drug AdministrationDocument21 pagesDoes Mass Drug AdministrationlauraNo ratings yet

- 216035-Article Text-532364-1-10-20211014Document9 pages216035-Article Text-532364-1-10-20211014hello byeNo ratings yet

- Captura de Tela 2023-09-08 À(s) 09.17.35Document26 pagesCaptura de Tela 2023-09-08 À(s) 09.17.35Isabela Di PardiNo ratings yet

- Acute Kidney Injury Due To Diarrheal Illness Requiring Hospitalization: Data From The National Inpatient SampleDocument8 pagesAcute Kidney Injury Due To Diarrheal Illness Requiring Hospitalization: Data From The National Inpatient SampleCherry SmileNo ratings yet

- EFFECT OF CANCER ON NIGERIA EPE A CASE STUDY OF EPE PROJECT (Repaired)Document63 pagesEFFECT OF CANCER ON NIGERIA EPE A CASE STUDY OF EPE PROJECT (Repaired)Oyewale EmmanuelNo ratings yet

- El Futuro de Una IRADocument7 pagesEl Futuro de Una IRAKev Jose Ruiz RojasNo ratings yet

- Ol 20 1 441 PDFDocument7 pagesOl 20 1 441 PDFeka satyani belinaNo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular_Health_Priorities_in_Sub-Saharan_Af_240704_084645Document8 pagesCardiovascular_Health_Priorities_in_Sub-Saharan_Af_240704_084645pavadesousa9teveNo ratings yet

- 14 - Towards Best Practice in Acute Stroke Care in Ghana A Survey of Hospital ServicesDocument11 pages14 - Towards Best Practice in Acute Stroke Care in Ghana A Survey of Hospital ServicesChristel CibalonzaNo ratings yet

- Danmusa Nigeria 2016Document10 pagesDanmusa Nigeria 2016sinta.wulandari-2023No ratings yet

- Burden of Disease From Helicobacter Pylori InfectiDocument11 pagesBurden of Disease From Helicobacter Pylori InfectisathiyasuthanNo ratings yet

- Jurnal RadiologiDocument9 pagesJurnal RadiologiAndrean HeryantoNo ratings yet

- Bacteriuria AsintomaticaDocument28 pagesBacteriuria AsintomaticaMauricio CifuentesNo ratings yet

- Applsci 14 05518 v2Document3 pagesApplsci 14 05518 v2otdelseocherkassyNo ratings yet

- American J Hematol - 2022 - Osunkwo - Burden of Disease Treatment Utilization and The Impact On Education and EmploymentDocument10 pagesAmerican J Hematol - 2022 - Osunkwo - Burden of Disease Treatment Utilization and The Impact On Education and EmploymentHijaz HijaNo ratings yet

- September CDC HAISDocument11 pagesSeptember CDC HAISnoval firdausNo ratings yet

- Tropical Med Int Health - 2019 - Bardach - Interventions for the control of Aedes aegypti in Latin America and theDocument23 pagesTropical Med Int Health - 2019 - Bardach - Interventions for the control of Aedes aegypti in Latin America and thekenmelin58No ratings yet

- AKI NowDocument10 pagesAKI NowMOHAMMED NAJJARNo ratings yet

- epidemiological-analysis-of-chronic-kidney-disease-from-1990-to-2019-and-predictions-to-2030-by-bayesian-age-period-cohort-analysisDocument14 pagesepidemiological-analysis-of-chronic-kidney-disease-from-1990-to-2019-and-predictions-to-2030-by-bayesian-age-period-cohort-analysisCorrêa ACNo ratings yet

- DOTSDocument3 pagesDOTSTammy Utami DewiNo ratings yet

- Ajbsr MS Id 001564Document3 pagesAjbsr MS Id 001564Rodrigo AlpizarNo ratings yet

- 2024 - Optimizing Artificial Intelligence in Sepsis Management Opportunities in The Present and Looking Closely To The FutureDocument12 pages2024 - Optimizing Artificial Intelligence in Sepsis Management Opportunities in The Present and Looking Closely To The Futurejedewe2439No ratings yet

- Hepatitis C Virus: Annals of Internal MedicineDocument17 pagesHepatitis C Virus: Annals of Internal MedicineMax CamargoNo ratings yet

- Emergency care of sepsis in sub-Saharan AfricaDocument20 pagesEmergency care of sepsis in sub-Saharan AfricathegroutNo ratings yet

- Dci 240026Document3 pagesDci 240026kk2020antijackersNo ratings yet

- LANCET LOCKDOWN NO MORTALITY BENEFIT A Country Level Analysis Measuring The Impact of Government ActionsDocument8 pagesLANCET LOCKDOWN NO MORTALITY BENEFIT A Country Level Analysis Measuring The Impact of Government ActionsRoger EarlsNo ratings yet

- cr-12-080-1Document6 pagescr-12-080-1medeval.pages.devNo ratings yet

- jcm-11-02573-v2Document20 pagesjcm-11-02573-v2Graziella AguiarNo ratings yet

- CKD - Small DatasetDocument25 pagesCKD - Small DatasetJames AmirNo ratings yet

- Achieving an AIDS Transition: Preventing Infections to Sustain TreatmentFrom EverandAchieving an AIDS Transition: Preventing Infections to Sustain TreatmentNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Final All Merged 2022Document309 pagesPediatric Final All Merged 2022mukul jindalNo ratings yet

- test1 محولDocument85 pagestest1 محولTojan Faisal Alzoubi100% (1)

- Inborn Errors of Metabolismiem Lecture 1Document32 pagesInborn Errors of Metabolismiem Lecture 1EMMANUEL ABEL IMAH100% (1)

- Anaphylactic ShockDocument25 pagesAnaphylactic ShockMaham BushraNo ratings yet

- Final Year Bhalani QuestionsDocument83 pagesFinal Year Bhalani QuestionsFaltuNo ratings yet

- GI BleedingDocument8 pagesGI BleedingNemanja VukcevicNo ratings yet

- Lecture 14 A Radiographic InterpretationDocument120 pagesLecture 14 A Radiographic InterpretationAlex AnderNo ratings yet

- PT Toolkit Table of ContentsDocument9 pagesPT Toolkit Table of ContentsCherylNo ratings yet

- Cerebrospinal Fluid CSFDocument60 pagesCerebrospinal Fluid CSFpikachuNo ratings yet

- Chronic Suppurative Otitis MediaDocument34 pagesChronic Suppurative Otitis Mediafreelancer.am1302No ratings yet

- Schwann Desmielinización 3Document12 pagesSchwann Desmielinización 3berenice laraNo ratings yet

- Fælles Kodningsdok. D. 13.03.2019. Sidste Kode 178Document4 pagesFælles Kodningsdok. D. 13.03.2019. Sidste Kode 178te buNo ratings yet

- Adrenergic Drugs: S. Parasuraman, M.Pharm., PH.D.Document25 pagesAdrenergic Drugs: S. Parasuraman, M.Pharm., PH.D.Zakaria salimNo ratings yet

- For Drug Recitation 1Document33 pagesFor Drug Recitation 1Abigail LonoganNo ratings yet

- DRUG STUDY FormatDocument3 pagesDRUG STUDY FormatJohn Edward CapistranoNo ratings yet

- Degenerative Disc Disease Concept MapDocument1 pageDegenerative Disc Disease Concept MapashleydeanNo ratings yet

- Pharmacotherapy of Peptic Ulcer: DR ZareenDocument50 pagesPharmacotherapy of Peptic Ulcer: DR ZareenGareth BaleNo ratings yet

- Congenital AnomaliesDocument22 pagesCongenital Anomaliesjessy100% (1)

- Gastrointestinal Pathology Case Studies ParDocument2 pagesGastrointestinal Pathology Case Studies Pardr nirupamaNo ratings yet

- Skin and Systemic DiseasesDocument19 pagesSkin and Systemic DiseasesEman FatimaNo ratings yet

- BPH PSPD 2012Document43 pagesBPH PSPD 2012Nor AinaNo ratings yet

- Pathogenesis and epidemiology of multiple sclerosis - UpToDateDocument28 pagesPathogenesis and epidemiology of multiple sclerosis - UpToDateMaimuna MarshedNo ratings yet

- MLS3174 Clinical Haematology FEB 18 PDFDocument9 pagesMLS3174 Clinical Haematology FEB 18 PDFVisaNathanNo ratings yet

- CPR - Basic Life SupportDocument84 pagesCPR - Basic Life SupportAzra Durak-Nalbantic100% (1)

- 2nd Drug StudyDocument39 pages2nd Drug StudyYanna Habib-Mangotara100% (3)

- ADAS - COG v1 85ptDocument9 pagesADAS - COG v1 85ptAnaaaerobiosNo ratings yet

- Download Complete Atlas of Ocular Optical Coherence Tomography 2nd Edition Fedra Hajizadeh PDF for All ChaptersDocument65 pagesDownload Complete Atlas of Ocular Optical Coherence Tomography 2nd Edition Fedra Hajizadeh PDF for All ChaptersmathiijuguNo ratings yet

- ICD 9 Diagnosis CodesDocument41 pagesICD 9 Diagnosis CodesEvy Liesniawati0% (1)