Production of Liquid Fuel From Plastic Wastes Using Integrated Pyrolysis Method With Refinery Distillation Bubble Cap Plate Column

Production of Liquid Fuel From Plastic Wastes Using Integrated Pyrolysis Method With Refinery Distillation Bubble Cap Plate Column

Uploaded by

vjtiitCopyright:

Available Formats

Production of Liquid Fuel From Plastic Wastes Using Integrated Pyrolysis Method With Refinery Distillation Bubble Cap Plate Column

Production of Liquid Fuel From Plastic Wastes Using Integrated Pyrolysis Method With Refinery Distillation Bubble Cap Plate Column

Uploaded by

vjtiitOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Production of Liquid Fuel From Plastic Wastes Using Integrated Pyrolysis Method With Refinery Distillation Bubble Cap Plate Column

Production of Liquid Fuel From Plastic Wastes Using Integrated Pyrolysis Method With Refinery Distillation Bubble Cap Plate Column

Uploaded by

vjtiitCopyright:

Available Formats

“Towards global technological excellence”

A

SEMINAR REPORT

ON

“Production of liquid fuel from plastic wastes using integrated pyrolysis method with

refinery distillation bubble cap plate column”

Submitted By:

ARJUN B. MOHOD

(STUDENT ID: - 19052005)

For the partial fulfilment of Degree of

Master of Technology in

Thermal Power Engineering

GOVERNMENT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, AMRAVATI

(An Autonomous Institute Of Govt. Of Maharashtra)

DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING

2019-2020

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 1

GOVERNMENT COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, AMRAVATI

(An Autonomous Institute Of Govt. Of Maharashtra)

DEPARTMENT OF MECHANICAL ENGINEERING

CERTIFICATE

This is to certify that the seminar report entitled “Production of liquid fuel from plastic

wastes using integrated pyrolysis method with refinery distillation bubble cap plate

column”, is being submitted and completed successfully by,

ARJUN B. MOHOD

(STUDENT ID:-19052005)

Dr. A. M. MAHALLE Dr. A.M. MAHALLE

(Guide) (Head of Department)

Mechanical Engineering

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 2

DECLARATION

I hereby declare that seminar report entitled “Production of liquid fuel from

plastic wastes using integrated pyrolysis method with refinery distillation bubble cap

plate column”,completed and written by me under the guidance of Dr. A. M. Mahalle,

Department of Mechanical Engineering, Government College of Engineering, Amravati. This

has not been previously performed for the award of any degree or diploma or any educational

certification.

ARJUN B. MOHOD

(STUDENT ID: - 19052005)

Place: Amravati

Date: / /

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 3

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

I am grateful to my respected guide Dr. A. M. Mahalle, for his kind, disciplined and

invaluable guidance which inspired me to solve all the difficulties that came across during

completion of the project.

I express my special thanks to Dr. A. M. Mahalle, Head of the Department, for his

kind support, valuable suggestions and allowing me to use all facilities that are available in

the Department during this project.

My sincere thanks are due to Dr. R. P. Borkar, Principal for extending the all

possible help and allowing me to use all resources that are available in the Institute.

I would like to thanks all the faculty members of Mechanical Engineering Department

for their support, for the successful completion of this project work. The acknowledgement

shall remain incomplete without expressing my warm gratitude to the almighty God.

I would also like to thank Family members and Friends for their continue support and

standing with me in all difficult conditions during this work.

ABSTRACT

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 4

The objective of this paper is to optimise the liquid product of pyrolysis from as much as

500g of polypropylene (PP) plastic waste, using a fixed bed type reactor in a vacuum

condition (−3mm H2O), to minimise the oxygen entering the reactor. The vapour flows

through the 4tray distillation bubble cap plate column for fractionation by utilising heat from

the reactor. Process conditions at 500–650 °C and of 580 °C optimum liquid oil yield is 88

wt.%, comprising of kerosene in tray I with a volume of 350 ml, gasoline in tray II and III

with a volume of 228 ml, and tray IV had no condensate. Gas yield is 5 wt.% and the rest is

char. At the conditions between 500 °C and 560 °C, gasoline yield in 6–67 wt.% comprises of

kerosene and gasoline. However, at process conditions between 600 °C and 650 °C yields of

64–83 wt.% comprising of diesel oil was obtained at tray I and II, while kerosene and

gasoline were obtained in the next tray. The characteristics of fuel obtained from plastic such

as density, viscosity, octane–cetane number, ash content and calorific value have similar

properties with those of fossil fuels.

Table of content

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 5

Sr. No. Topic Page No. Sign

1 Introduction

2 Literature Review

3 Materials and Methods

4 Result and discussion

5 Conclusion

6 References

Sr.No. Name of table Page no.

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 6

4.1 The product of distillation bubble cap column of each tray

Fuel products from plastic wastes integrated pyrolysis method

4.2 with distillation bubble plate column

Specific gravity and API gravity of crude oil and selected

4.3

products

The fuel kinematic viscosity (40) of distillation bubble cap

4.4

column product and standard parameter

The ash content of distillation bubble cap column product and

4.6

standard parameter ASTM standards 2008

Fuel calorific value of distillation bubble cap column product

4.6

and standard parameter of gasoline, diesel and kerosene

Effects of pyrolysis temperature on octane and cetane number of

4.7 each tray and standard parameter of gasoline, diesel and

kerosene

Sr. No. Name of figure Page no.

Thermal cracking pyrolysis integrated with distillation

4.1

bubble cap column

The fuel density of product through the distillation bubble cap

4.2

column

The pyrolysis products (yield %wt) as a response of process

4.2 temperature

1. INTRODUCTION

Nowadays plastic materials have become an indispensable part of social life and the fact that

they generate excessive amounts of waste causes large economic losses. For purposes of

recovering these plastic materials various pyrolysis techniques (thermal, catalytic, inert

atmosphere, oxygen environment, under high pressure pyrolysis, etc.) have been developed.

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 7

Due to its unique structure and properties (cheap, high resistance against impact, easy

processing, etc.), polyethylene is used more commonly in comparison to other plastic types

such as PS, PET, PVC and consequently more waste is formed. Furthermore, it has been

indicated that the pyrolysis mechanism could be brought to light as such and asserted that

kinetic parameters could be determined with the help of this mechanism. Due to the fact that

plastic material could stay a very long time without degradation in the environment, great

effort has been expanded for the production of biodegradable polymer materials especially in

recent years. In a study involving the thermal and BaCO3catalytic pyrolysis of HDPE

material, it has been reported that the liquid products obtained at 450˚C temperature and 0.1

catalyst/plastic ratio display the properties similar to gasoline, kerosene and fuel oil In the

subject matter study, catalytic and thermal degradation of HDPE and PP were studied and the

effects of some factors such as catalysts and temperature on degradation products were

analyzed. In pyrolysis studies, the yield of the liquid product obtained was determined and

the characterization of this liquid product was elucidated by GC/MS analysis

Pyrolysis is a decomposition process of long-chain hydrocarbon (polymer) molecules into

smaller sizes (monomer) with the use of high heat (450–800 °C) [8] in a shorter duration and

a condition with the absence of oxygen, generating products in form of carbon, as residues

and volatile hydrocarbons which can be condensate as fuel and non-condensible as gaseous

fuel. The reaction of this polymer is a weak bond chain and is damaged by increasing

temperature, followed by the formation of the free radical propagation stage. These free

radicals will then separate again to form smaller ones which produce more stable compounds.

These smaller free radicals produce stable compounds in the form of paraffin compounds,

isoparaffins,, naphthenes and aromatics with the general reaction mechanism for plastics

thermal degradation [1]. Pyrolysis of waste plastics PP has been investigated by many

researchers who discovered liquid pyrolysis products to be similar to crude oil [9]. The liquid

fuel obtained from the pyrolysis process cannot be directly used as fuel, due to the presence

of impurities (ash) and wax from the feedstock hence, the pyrolysis product is used in

reducing the ash and wax content in fuel products. The purification of the pyrolysis products

was conducted using distillation bubble cap tray column which reduces the ash and wax

content in fuel products. Moreover, used for separate the pyrolysis product has based on

different boiling points. This review therefore focuses on the effect of temperature on the

pyrolysis results which have been integrated with the bubble cap distillation column. This is

carried out by utilising the heat from the reactor to separate the liquid product in a vacuum

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 8

condition which minimises the oxygen entering the reactor. However, in vacuum conditions,

organic vapour leaves the reactor faster, thereby reducing vapour residence time and shifting

evaporation to lower temperature areas, thus reducing the average vapour temperature. This

establishes a more favourable mass transfer condition, and obtains the highest liquid yield.

The obtained liquid product is analysed of physical characteristics to determine the specific

type of product and compare fuel oil with the fossil. In the last five years however, a limited

number of plastic pyrolysis processes have been developed to overcome these limitations.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

1.Lee, K.-H., 2006, Describes the thermal and catalytic degradation of waste high-density

polyethylene (HDPE) in order to recover the fuel oil from waste plastics. Among waste

plastics, the polyolefinic type that is a material of high potential for alternative oil production

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 9

is more than 70% of the total plastic content in municipal solid waste (MSW). Waste HDPE

in polyolefinic plastic is a difficult material in the pyrolysis process by treatment at high

temperature, because of its high degradation temperature and high viscosity products such as

low-quality wax.

2.Wong, S.L., Ngadi, N., Abdullah, T.A.T., Inuwa, I.M., 2017, A study has been

conducted to investigate the effects of temperature and LHSV on catalytic cracking of LDPE

dissolved in benzene. Increase in temperature was found to increase the extent of LDPE

conversion, thus increasing the C5 and C6 aliphatic compounds, and decreased the amount of

unidentified products, which are mostly large hydrocarbons oligomers.

3.Scheirs, J. (Ed.),investigated the plastic pyrolysis involves the thermal degradation of the

wastes in the absence of oxygen/air. It provides for the disposal of plastic wastes with

recovery of valuable gasoline and diesel-range hydrocarbons. During pyrolysis, the polymeric

materials are heated to high temperatures, such that their macromolecular structures are

broken down into smaller molecules, resulting in a wide range of hydrocarbons being formed.

These pyrolytic products can be divided into a non-condensible gas fraction, a liquid fraction

(consisting of paraffins, olefins, naphthenes and aromatics), and solid residues (i.e. char).

4. Lopez, G., Artetxe, M., Amutio, M., Bilbao, J., Mabood, F., Jan, M.R., Shah, J.,

Jabeen, F., Hussain, Z., 2010, A review on the routes for the valorization of wastes

polyolefinic plastic to produce fuel and chemicals also review on degree of development of

pyrolysis technologies in order to ease their definitive implementation.

5.Kalghatgi, G.T., 2001, Experimental investigation on measuring knock intensity in single

cylinder engine and concluded that, the antiknock quality of fuel in given engine operation

condition is given by its octane index OI=RON-KS, higher the octane number index better

the antiknock quality.

6. Silvarrey, L.S. Diaz, Phan, A.N., 2016,Investigatedfive types of MPW (HDPE, LDPE,

PP, PET and PS) were used during this study. They were collected from O'Brien Recycling

Centre in Wallsend (Newcastle upon Tyne, UK). HDPE, LDPE, PP and PET were cut into

circular samples of 1 mm size while PS was cut into circular sample of 4 mm size. Individual

components in MPW were then characterised for its properties. HDPE, LDPE and PP

consisted mainly of carbon and hydrogen with very low ash content, except to HDPE. Their

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 10

high heating value was found around 44e46 MJ/kg, which is comparable with that of diesel

oil. PET had the lowest high heating value, which was 22.96 MJ/kg. This is because it

contains around 30% oxygen content and high ash content (around 8 wt%). High ash content

in HDPE could be caused by alterations in the structure of plastic due to additives. The

volatile matters for all MPW samples were high, in a range of 80e90% while moisture

content was negligible for all of them.

7.Barbarias, I., Artetxe, M., Arregi, A., Alvarez, J., Lopez, G., Amutio, M., Olazar, M.,

2015, Investigated the effect of temperature in the catalytic cracking 0f high density

polyethylene over a spent FCC catalyst on the product distribution ha been studied using two

step reaction system. Thermal pyrolysis of HDPE has been carried out in a conical spouted

bed reactor and the volatiles formed have been fed in-line into a catalytic fixed bed reactor

under the temperature range 450 c- 550 c at this temperature gasoline and light olefins are the

main product fractions obtained.

8.Arena, U., Mastellone, M.L., 2006. In: Scheirs, J. (Ed.), studied the Gas–solid

fluidization operation by which a bed of solid particles is led into a fluid-like state through

suspension in a gas. Compared with other methods of gas–solid contacting (such as fixed

beds, rotary cylinders, flat hearths, etc.), fluidized beds have some rather unusual and useful

properties that can lead to desirable characteristics for waste thermal treatments in general,

and for plastic waste pyrolysis in particular.

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1. Materials

Samples were sorted according to resin codes developed by the Society of Plastic Industries.

The raw materials utilised in this study were derived from Polypropylene (PP) type plastic

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 11

Density (ρ) = 1.30–1.58 g/cc; Crystalline melting temperature (TM) = 168–175 °C such as

plastic bottle waste gathered from scavengers around Keputih Sukolilo Surabaya, Indonesia.

Dirt was washed off the plastic waste, after which it was then cut into small pieces, with sizes

of 1×3 cm with the use of enumerator machines, to significantly reduce the volume of the

sample chamber in the reactor.

3.2. Apparatus and experimental procedures

This study employed a fixed bed type reactor, made of stainless steel (2). The reactor heating

process reaches a maximum temperature of 750 °C (3), in a space that has been isolated to

reduce the heat emanating from the system (1). This reactor can work either as a thermal or

catalytic pyrolysis process. The temperature is measured and regulated in an electric heating

source, using the Integral Proposal (PI) method with Off-Set 2 °C as a process variable

controller. The heating rate is 15.46 K/min, including the slow pyrolysis category.

Temperatures varied at 500, 520, 540, 560, 580, 600, 620 and 650 °C under vacuum (Pinput=

−7 mm H2O; Pout = −10 mm H2O) to remove the air (oxygen) in the reactor. The

experiments were conducted with a prepared 500 g of plastic waste. The sample was then

heated and melted in the reactor, producing organic vapour. The vapour flows through

distillation of bubble cap column as a result of the heat from the reactor and vacuum pressure.

Ash residue and wax carried by the vapour will go down to the reactor due to the condensate

or resistance beneath the column plate. Whereas, un-condensed vapour flows through the

riser (reverse current below the cap), moves down through the annular space (between the

riser and the cap), and eventually forms a liquid bubble (vapour mixture with condensate)

through a series of available slots along the edge of the lid at the bottom. Condensed vapour

is stored on a column plate which then flows into tray I (4) as an oil product. Vapours that are

un-condensate in tray I, are inhibited under the column plate II through column I. Vapour

having a higher boiling point will be condensed through column I, then collected in tray I.

Whereas, the un-condensate vapour flows through the riser, moving down through space

annular, and forms bubbles through a series of slots. The condensate then flows on the

column plate II and is then stored in tray II. The same process is repeated for tray III.

However, the vapour that does not condense in tray III is a volatile compound (low boiling

point), condensed with the aid of a condenser using a water cooler (± 5 °C), leaving the

condensed vapour to be accommodated in tray IV. Unconditioned vapour flows through a

gas-washing bottle filled with H2O2 (10%, v/v) solution to absorb acidic and toxic

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 12

compounds with the use of a vacuum pump, before being disposed of into the environment.

The temperature of each condensate passing through the tray has been measured using a

digital thermocouple. The mass percentage of product composition could then be calculated

for % conversion, % oil, % residue and % gas according to the formula given below.

Conversion of thermal cracking:

Conversion (wt.%) = Mass of polypropylene (PP) − Mass of residue /Mass of polypropylene

(PP) × 100%

Liquid Yield: Oil (wt.% ) = Mass of oil/ Mass of polypropylene (PP) × 100%

Residue (Char) Yield: Residue (wt.% ) = Mass of residue /Mass of polypropylene (PP) ×

100%

Gas Yield: Gas (wt.%) = 100% − (Oil + Residue)

4. RESULT AND DISCUSSION

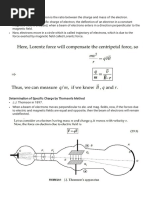

This study made use of a pyrolysis reactor integrated with bubble cap distillation column to

pyrolyse plastic and separate liquid products, in order to reduce the energy requirement of the

process. The vapour phase reactor will condense in each tray due to contact with the cold

surface. The component with the heaviest oil will condense in tray I, and so on. The

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 13

distillation in the study was carried out without reflux, because each tray served as a cold

surface to condense the vapour, meaning that fractionation can occur in each tray. The

maximum number of trays that can be operated by the bubble cap distillation column process

is four. This is because there is no condensate in the fourth tray at optimum process

conditions (580 °C), even though a condenser unit with cooling water (± 5 °C) has been added

(see Fig.4.1)

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 14

Fig4.1 Thermal cracking pyrolysis integrated with distillation bubble cap column

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 15

4.1. Polypropylene conversion and liquid yield

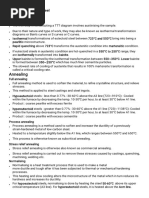

The pyrolysis process of plastic waste generates fuel, offering an alternative to gas. But in

general, the composition of pyrolysis liquid product may differ, depending on the

composition of the feedstock and its process parameters . The results of pyrolysis products

(liquid, gas and char) were obtained within the range of 500–650 °C. From the degradation of

polypropylene (PP), plastic waste pyrolysis was calculated using Eqs. (1)–(3), and the results

are illustrated in Fig. 4.2. Also, the product of distillation bubble cap column of each tray (ml

fuel oil /g PP plastic) is presented in Table 1. The quantity of gas and fuel oil yield has its

conversion (wt.%) illustrated in Fig. 2. There was an increase in the conversion of PP plastic

waste from 9% (at 500 °C) to 99.87% (at 650 °C). Theoretically, the yield will increase

alongside an increase in temperature due to the fact that the reaction rate is faster at high

temperatures. Therefore, as temperature increased, more heat was supplied to the polymer in

order to weaken its chain structure, and this resulted in more polymer chains being cracked.

However, to obtain liquid products such as fuel, optimum process conditions are required

(Table 4.1). This research obtained optimum conditions for fuel oil at 580 °C (1156 ml fuel/g

PP) or 578 ml fuel oil in 500 g PP. Under the optimum process conditions, PP polymers

experience melting temperature (TM) at first, and then proceed to decomposition temperature

(Td) conditions for the polymer bonds to form hydrocarbon compounds (monomers). These

compounds then undergo degradation of thermal cracking recombination in order to form

hydrocarbon products such as paraffins, olefins, naphtha and aromatic. Simultaneously, the

combination of free radicals as a result of secondary reactions in stable hydrocarbon

compounds also forms PONA compounds. Process conditions above optimum, polymers

experience cracking recombination and combination degradation to form hydrocarbon

products such as PONA. Increasing temperature results in oligomeric cracking, i.e. in the

primary reaction, there is a termination of imperfect polymer bonds (wax forming), and the

secondary reactions of free radicals form short chain hydrocarbons (gas compounds are

formed). As a result, the gas yield rises and yields fuel oil falls, as illustrated in Fig. 4.2.

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 16

Total product

Pyrolysis product of distillation (ml fuel/g pp)

temperature

(°C) Tray I Tray II Tray III Tray IV

500 0.08 - - - 0.08

520 0.12 - - - 0.12

540 0.544 0.066 - - 0.611

560 0.348 0.136 0.072 - 0.556

580 0.7 0.376 0.08 - 1.156

600 0.574 0.438 0.058 0.022 1.092

620 0.846 0.074 0.018 0.024 0.962

650 0.150 0.244 0.126 0.308 0.828

Table 4.1 The product of distillation bubble cap column of each tray

Fig 4.2. The pyrolysis products (yield %wt) as a response of process temperature

Moreover, carbon residue rises together with the vapour due to heat and rising

pressure in the reactor (ash content rises). This is however responsible for the obtained low

product quality in trays I to IV within the temperature range 620–650 °C. Condensate (fuel

oil) cannot be used directly due to its high ash and wax content. The product came out

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 17

looking brownish-black and viscous, which is an indication that it needs to be

recycled(Tables 4.2 and 4.3). (See Fig. 4.3.) The vapour flows through the 4-tray distillation

bubble cap plate column by utilising heat from the reactor, and this is due to the heat

emanating from the reactor or vapour pressure which can condensate in the tray III at

optimum conditions (580 °C). Whereas, at temperatures above the optimum conditions

vapour can be condensate in tray IV, but a higher energy is required to obtain high ash and

wax content (tray I and II), which will then require a cost to separate. In addition, various

characteristics of the fuel obtained in accordance with the boiling point of each product are

achieved. However, vapour which is left un-condensate in tray IV is processed using H2O2

10% (v/v) in gas washing bottles to absorb acidic gas and CO2 formed from pyrolysis before

being discharged into the environment.

Fig 4.3. Fuel products from plastic wastes integrated pyrolysis method with distillation

bubble cap column

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 18

4.2. Physical properties and characteristics of oils

Fuel derived from pyrolysis is very similar to crude oil, and therefore cannot be directly used

as fuel or other sources of energy, given that it must meet certain standard specifications to

ensure the performance of the combustion engine. Plastic pyrolysis products are considered

to be sources of hydrocarbons from petroleum in the form of naphtha products. As a result,

the fuel characteristics of these products are modified to standard fuel products. It therefore

needs to be refined, and this research made use of the distillation bubble cap plate column in

doing so. As a result, a wide range of fuels obtained is expected to be used on an engine, in

accordance with the characterisation of the fuel oil. The characterisation or specifications for

standard fuels have been established by ASTM/IP or instrument tools that conform to ASTM

standards [4].

4.2.1. Characterisation of oils by density

Density is one of the parameters indicating the characteristics of the product. A specific

gravity was measured according to ASTM D 1298 standard at 60 °F. Table 4.2 shows fuel

specification results of Distillation Bubble Cap Tray Column based on Specific Gravity, °API

from Handbook of Petroleum Product Analysis [5]. Liquid fuel specification standard based

on specific gravity or °API of Handbook of Petroleum Product Analysis is shown in Table 3.

The obtained results demonstrated that the condensate fuel at different temperatures resulted

in different types of fuel. The condensate fuel in tray I resulted in gasoline at temperatures of

500–560 °C, kerosene at temperatures of 580 °C and 600 °C, and diesel at temperatures of

620 °C and 650 °C. However, the condensate fuel on tray II yielded gasoline at temperatures

of 540–620 °C and kerosene at the temperature of 650 °C. The condensate fuel on tray III

resulted in gasoline at temperatures of 580–650 °C, and the condensate fuel on tray IV

resulted in gasoline at temperatures of 600–650 °C.

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 19

Pyrolysis Tray I Tray II Tray III Tray IV

temperatur

ρ60 S.g.60 °API ρ60 S.g.60 °API ρ60 S.g.60 °API ρ60 S.g.60 °API

e (°C)

500 0.7512 0.7518 56.71 - - - - - - - - -

520 0.7520 0.7528 56.46 - - - - - - - - -

540 0.7512 0.7521 56.64 0.7457 0.7463 58.1 - - - - - -

560 0.7608 0.7614 54.34 0.7248 0.7254 63.56 - - - - - -

580 0.7756 0.7762 50.80 0.7457 0.7464 58.08 0.7121 0.7130 66.96 - - -

600 0.7789 0.7800 49.98 0.7453 0.7454 58.33 0.7163 0.7169 65.87 0.6910 0.6916 73.09

620 0.7853 0.7860 48.52 0.7221 0.7228 64.27 0.7252 0.7258 63.46 0.7184 0.7199 65.10

650 0.8241 0.8249 40.05 0.8082 0.8089 43.43 0.7707 0.7714 51.93 0.7383 0.7390 59.98

Table 4.2The fuel density of product through the distillation bubble cap column

Material S.G 60°F/60°F API gravity, deg.

Crude 0.65 - 1.06 87 - 2

Casinghead liquid 0.62 - 0.70 97 - 70

Gasoline 0.70 - 0.77 70 - 52

Kerosene 0.77 - 0.82 52 - 40

Lubricating Oil 0.88 - 0.98 29 - 13

Residual and cracked residual 0.88 - 1.06 29 - 2

Table 4.3Specific gravity and API gravity of crude oil and selected products

4.2.2. Characterisation of oils by kinematic viscosity

Viscosity is an important property of oil products which affects the handling or storage,

pumping and burning (including the selection of burner types used) of these products. If the

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 20

kinematic viscosity value is low, it will influence the oil fuel quality, giving it a low heating

value [1]. Kinematic viscosity was measured according to ASTM D 445 standard at 40 °C

[4]. The values of the fuel kinematic viscosity of each tray are presented in Table 4.4. It can

be observed from Table 4.4 that the temperature pyrolysis and height of the column (tray)

significantly affected the products’ kinematic viscosity. The high process temperature

pyrolysis accelerates the breaking of the polymer structural bonds. Moreover, under certain

process conditions, the termination of the polymer bonds is imperfect, and results in the

vapour containing polymers due to the influence of pressure and temperature in the reactor.

According to the presented data, the product has high kinematics viscosity at condensate tray

I and II at temperatures of 620 °C and 650 °C. The results of the kinematic viscosity analysis

shown in Table 4.4 indicate that fuel oil products obtained through the distillation bubble cap

plate column possess similar properties with those of fossil fuels. It is in accordance with the

characteristics of kerosene and gasoline in the process conditions of 500–600 °C, while above

the temperature optimum is obtained by diesel, kerosene, and gasoline in the process

conditions of 620–650°C.

Pyrolysis kinematic viscosity at 40°C(mm²/g) Standard Kinematic viscosity at 40°C

temperatur Gasoline(mm²/g Kerosene(mm²/g

Tray I Tray II Tray III Tray IV Diesel(mm²/g)

e (°C) ) )

500 0.652 - - - 1.3 - 2.4 1.4 - 3.0 1.9 - 5.5

520 1.006 - - - - - -

540 1.121 0.897 - - - - -

560 1.578 0.960 - - - - -

580 2.445 1.080 0.92 - - - -

600 2.850 1.236 1.11 0.450 - - -

620 3.150 1.590 1.26 0.666 - - -

650 4.140 1.860 1.46 1.044 - - -

Table 4.4The fuel kinematics viscosity (40°C) of distillation bubble cap column product and

standard parameter [4]

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 21

4.2.3. Characterisation of oils by ash content and wax

The ash content is the amount of impurities in the form of burning ash. During pyrolysis,

there is a decomposition of plastic polymers which produces vapour and char. The ash

content is carried by vapour, and this can diminish the quality of fuel products as regards the

nature of fuel cleanliness which can have consequences on the performance combustion

engines. Ash content from each tray is shown in Table 4.5. From Table 4.5, it can be

observed that ash acquisition content for tray I, met the standards at 500 °C and 520 °C, tray

II met the standards at 540 °C and 600 °C, tray III met the standards at 580 ◦C and 600 °C,

and tray IV met the requirements at 600–650 °C. This is due to the lack of oxygen entering

the reactor (vacuum process conditions), and as a result, there is no oxidation reaction in the

reactor. The effect of pyrolysis temperature on the ash content of each product shows the

tendency that an increase in pyrolysis temperature will lead to an increase in the ash content

of each tray. This can be attributed to an increase in temperature and pressure which allows

carbon from the pyrolysis process to carry vapour in column distillation (620–650 °C). Fuel

is classified as low-quality when it contains ash and wax. The ash content from plastic

degradation residues appears in form of carbon residue. However, it is very important for the

ash content to not exceed the standard set, because if it does, it could damage the internal

combustion engine piston when used as fuel.

Pyrolysis Ash content(%w/w) Standard ash content. %wt

temperature (°C) Tray I Tray II Tray III Tray IV Light Oil Heavy Oil

500 0.01 - - - 0.015 0.15

520 0.01 - - - - -

540 0.02 0.008 - - - -

560 0.02 0.011 - - - -

580 0.03 0.012 0.005 - -

600 0.32 0.014 0.005 0.011 - -

620 0.39 0.022 0.018 0.002 - -

650 0.39 0.026 0.025 0.022 - -

Table 4.5The ash content of distillation bubble cap column product and standard parameter

ASTM standards 2008 [4]

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 22

4.2.4. Characterisation of oils by calorific value

One of the important properties of fuel is its calorific or heating value, which is defined as the

energy given when the fuel mass unit is burned without sufficient air. The equipment

employed in determining these calorific values was calorimeter 5E-C5500 Series Digital in

accordance with ASTM D-4809. The calorific values of each tray as shown in Table 4.6 were

similar to those reported by Silvarrey and Phan (2016) [6] which were within the range of

44–48 MJ/kg. These values were also similar to heating values of conventional

fuel/petroleum and fuel oil product from plastics pyrolysis reported by many studies which

are within the range of 33.6– 53.4 MJ/kg, depending on the original plastic polymer

composition. The production of liquid fuel from plastic waste using this method is therefore

feasible to be applied.

Pyrolysis Calorific value(MJ/kg) Standard Calorific value(MJ/kg)

temperature Gasoline(MJ/kg Kerosene(MJ/kg

Tray I Tray II Tray III Tray IV Diesel(MJ/kg)

(°C) ) )

500 47.205 - - - 45.6 46.5 43.5-55.7

520 46.289 - - - - - -

540 46.944 46.006 - - - - -

560 46.441 46.503 - - - - -

580 46.851 46.561 46.745 - - - -

600 46.823 47.205 46.312 46.347 - - -

620 45.154 46.334 46.214 46.9 - - -

650 44.945 46.319 46.316 47.231 - - -

Table 4.6Fuel calorific value of distillation bubble cap column product and standard

parameter of gasoline, diesel and kerosene [7].

4.2.5. Characterisation of oils by octane and cetane numbers

The octane number is a measure of a fuel’s ability to resist ‘knock.’ The octane requirement

of an engine varies with compression ratio, geometrical and mechanical considerations, and

operating conditions. The higher the octane number, the greater the fuel’s resistance to

knocking or pinging during combustion. The anti-knock or octane quality as indicated by the

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 23

Research and Motor Octane numbers (RON and MON), is an essential property of fuel.

Generally speaking, the anti-knock quality of a fuel in a given engine operating condition is

defined by its octane index OI = RON −KS where K is a constant for that condition, and S is

the sensitivity (RON − MON). The higher the octane index, the better the antiknock quality

of the fuel. K is often assumed to be 0.5 so that OI=(RON + MON)/2 [7]. Cetane number

(CN) on the other hand, is an empirical parameter associated with the ignition delay time of

diesel fuels. Octane and cetane numbers were measured using portable octane metre, Kohler

K88600 instrument. Test results were equivalent to ASTM D2699 and D2700 for octane

number of gasoline, and equivalent to ASTM D613 for cetane number of diesel fuel. Octane

and cetane numbers from each tray and standards parameter are shown in Table 4.7.

Table 4.7 indicates that the octane number is significantly influenced by the

temperature and tray position. The higher the pyrolysis temperature, the lower the octane

number for each tray and the compounds become non-volatile (the lower the boiling point).

This is due to the formation of branched, aromatic and polyaromatic compounds (aromatic

groups, naphtha and isoalkanes), whereas at high temperatures, non-volatile compounds such

as long-chain olefins and n-paraffins are formed, and this increases the cetane number value.

High octane numbers are better for internal engine combustions, but aromatic groups cannot

be tolerated by the environment due to the fact that it is difficult to degrade. As a result, the

aromatic content (40%, v/v) which is the maximum limit in fuel oil.

Pyrolysis temperature (°C) Standard octane/cetane number

650 Gasoline

540 560 580 600 600 Diesel ASTM

ASTM

Tray I Tray I Tray I Tray I Tray II Tray IV D613

D2699

Gasoline

RON 97.1 97.2 89.1 88.7 92.2 93.8 90.2-107.1

MON 83.7 83.5 81.8 81.5 84.0 85.0 82.6-103.1

(R+M)/

90.4 90.3 85.4 85.1 88.1 89.4 87.3-105.1

2

Diesel

CN 1.70 0.00 45.50 45.50 48.00 48.70 Min. 30

Table 4.7Effects of pyrolysis temperature on octane and cetane number of each tray and

standard parameter of gasoline, diesel and kerosene

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 24

5. CONCLUSION

A study has been conducted to investigate the effects of temperature and optimise liquid

products through refinery distillation bubble cap plate column. There are differences in liquid

fuel characterisation yielded on each tray depending on the pyrolysis temperature. The type

of fuel is based on an analysis of the characterisation of any condensate. Fuel condensate on

tray I at temperatures of 500–560 °C, 580–600 °C, and 620–650 °C yielded liquid fuels with

specifications of gasoline, kerosene, and a mixture of diesel and polymer PP (wax),

respectively. Fuel condensate on tray II at temperatures of 540–620 oC and 650 °C yielded

liquid fuels with specifications of gasoline and kerosene, respectively. Fuel condensate on

tray III at temperatures of 580–650 °C yielded gasoline, and fuel condensate on tray IV at

temperatures of 600– 650 °C yielded gasoline. The characteristics of fuel obtained from

plastic such as density, viscosity, octane–cetane number, ash content and calorific value have

similar properties with those of fossil fuels. Based on the characteristic analysis, fuel oil from

plastic waste through Integrated Pyrolysis Method with Refinery Distillation Bubble Cap

Plate Column can be used directly for engine or transportation fuel for gasoline type and

kerosene, while the diesel fuel is recycled again to meet specifications of fuel oil.

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 25

6. REFERENCES

[1] Lee, K.-H., 2006. Thermal and catalytic degradation of waste HDPE. In: Wiley, John

(Ed.), Feeds Stock Recycling and Pyrolys S of Waste Plastics. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd,

Canada, http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/0470021543.ch5.

[2] Scheirs, J. (Ed.), Feedstock Recycling and Pyrolysis of Waste Plastics: Converting Waste

Plastics into Diesel and Other Fuels. Canada https://doi.org/10.1002/0470021543.ch15

[3] Lopez, G., Artetxe, M., Amutio, M., Bilbao, J., Mabood, F., Jan, M.R., Shah, J., Jabeen,

F., Hussain, Z., 2010. Catalytic conversion of waste low density polyethylene into fuel oil. J.

Iran. Chem. Res. 3, 121–131. MaXiaolong, Ridner, D., Zhang, Z., Li, X., Li, H., Sui, H., Gao,

X., 2017. Study on vacuum pyrolysis of oil sands by comparison with retorting and nitrogen

sweeping pyrolysis. Fuel Process. Technol. 163, 51–59. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.

2017.04.011

[4] ASTM Standards, 2008. D396-17 - Standard Specification for Diesel Fuel Oils. ASTM

International, United States, http://dx.doi.org/10.1520/D0396-17.

[5] Speight, J.G., 2002. Handbook of petroleum product analysis. In: Wiley-Interscience.

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey, Published simultaneously in Canada.

Tadmor, Zehev, 2006. Principle of polymer procesing. In: Wliey. An SPE Technical, vol. A,

second ed. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., United States of America

[6] Silvarrey, L.S. Diaz, Phan, A.N., 2016. Kinetic study of municipal plastic waste. nt. J.

Hydrog. Energy 41 (37), 16352–16364. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhydene. 2016.05.202.

[7] Kalghatgi, G.T., 2001. Fuel Anti-Knock Quality - Part I. Engine Studies. http://dx.doi.

org/10.4271/2001-01-3584.

[8]. Arena, U., Mastellone, M.L., 2006. In: Scheirs, J. (Ed.), Fluidized Bed Pyrolysis of

Plastic Wastes. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, Canada, ISBN: 0-470-02152-7, http:

//dx.doi.org/10.1002/0470021543.ch16.

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 26

[9]Wong, S.L., Ngadi, N., Abdullah, T.A.T., Inuwa, I.M., 2017. Conversion of low density

polyethylene (LDPE) over ZSM-5 zeolite to liquid fuel. In: Fuel, vol. 192. pp. 71– 82.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.fuel.2016.12.008.

[10] Sharma, B.K., Moser, B.R., Vermillion, K.E., Doll, K.M., Rajagopalan, N., 2014. Production,

characterization and fuel properties of alternative diesel fuel from pyrolysis of waste plastic grocery

bags. Fuel Process. Technol. 122. http://dx. doi.org/10.1016/j.fuproc.2014.01.019.

[11] Barbarias, I., Artetxe, M., Arregi, A., Alvarez, J., Lopez, G., Amutio, M., Olazar, M., 2015.

Catalytic cracking of HDPE pyrolysis volatiles over a spent FCC catalyst. Chem. Eng. Trans. 43,

2029–2034. http://dx.doi.org/10.3303/CET1543339.

Government College of Engineering, Amravati 27

You might also like

- Raw Material Specification Sheet - Petroflo 20Y3437 New50% (4)Raw Material Specification Sheet - Petroflo 20Y3437 New2 pages

- Pyrolysis of Waste Tires, A Modeling and Parameter Estimation Study Using Aspen Plus PDFNo ratings yetPyrolysis of Waste Tires, A Modeling and Parameter Estimation Study Using Aspen Plus PDF12 pages

- Cts Automata Fix Previous Error Debugging: Cognizant Telegram Group50% (2)Cts Automata Fix Previous Error Debugging: Cognizant Telegram Group56 pages

- Design and Fabrication of Extraction of Fuel From Waste Plastics Using PyrolysisNo ratings yetDesign and Fabrication of Extraction of Fuel From Waste Plastics Using Pyrolysis5 pages

- Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) Nanoparticle Filled PolypropyleneNo ratings yetCalcium Carbonate (CaCO3) Nanoparticle Filled Polypropylene8 pages

- 2sustainable Utilization of Value-Added Products From The CatalyticNo ratings yet2sustainable Utilization of Value-Added Products From The Catalytic13 pages

- Aswan 2020 J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1500 012061No ratings yetAswan 2020 J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 1500 0120619 pages

- Production of Fuels From Nigeria's Untapped Waste Wealth' Using PyrolysisNo ratings yetProduction of Fuels From Nigeria's Untapped Waste Wealth' Using Pyrolysis14 pages

- 4. Kinetics and fuel properties of the oil obtained from the pyrolysis ofNo ratings yet4. Kinetics and fuel properties of the oil obtained from the pyrolysis of8 pages

- An Introduction To Molecular Thermal Energy Storage: A Seminar Report Submitted ToNo ratings yetAn Introduction To Molecular Thermal Energy Storage: A Seminar Report Submitted To20 pages

- Analysis and Production of Fuel From Waste Plastic Using Thermal Cracking ProcessNo ratings yetAnalysis and Production of Fuel From Waste Plastic Using Thermal Cracking Process58 pages

- Waste Plastic Pyrolysis Oil As Alternative For SI and CI EnginesNo ratings yetWaste Plastic Pyrolysis Oil As Alternative For SI and CI Engines8 pages

- Characterization Studies Waste Plastic Oil and Its BlendsNo ratings yetCharacterization Studies Waste Plastic Oil and Its Blends12 pages

- Hot Air Plastic Welding For PolyethyleneNo ratings yetHot Air Plastic Welding For Polyethylene24 pages

- Production of Liquid Fuel From Plastic Waste Using Integrated Pyrolysis Method With Refinery Distillation Bubble Cap Plate Column-1No ratings yetProduction of Liquid Fuel From Plastic Waste Using Integrated Pyrolysis Method With Refinery Distillation Bubble Cap Plate Column-19 pages

- Feasibility Study of Conversion of Selected Plastic in To Synthetic Fuel (Synthetic Diesel) - A ReviewNo ratings yetFeasibility Study of Conversion of Selected Plastic in To Synthetic Fuel (Synthetic Diesel) - A Review5 pages

- Simulation Study For Production of Hydrocarbons From WasteNo ratings yetSimulation Study For Production of Hydrocarbons From Waste9 pages

- Sharif 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. E PDFNo ratings yetSharif 2019 IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. E PDF12 pages

- Applications of Fuel Cells: A Seminar Report OnNo ratings yetApplications of Fuel Cells: A Seminar Report On5 pages

- Engineering Journal Duplex Stainless Steel Self-Ligating Orthodontic Brackets by Micro-Powder Injection MouldingNo ratings yetEngineering Journal Duplex Stainless Steel Self-Ligating Orthodontic Brackets by Micro-Powder Injection Moulding10 pages

- Composite Materials Journal of ThermoplasticNo ratings yetComposite Materials Journal of Thermoplastic12 pages

- CHEM-E-CAR - PEM FUEL CELL 250 WATT - UnlockedNo ratings yetCHEM-E-CAR - PEM FUEL CELL 250 WATT - Unlocked133 pages

- The University of Bradford Institutional RepositoryNo ratings yetThe University of Bradford Institutional Repository45 pages

- Low-Impact Friction Materials For Brake Pads: Andrea BonfantiNo ratings yetLow-Impact Friction Materials For Brake Pads: Andrea Bonfanti214 pages

- Energy Recovery From Biomass by Fast PyrolysisNo ratings yetEnergy Recovery From Biomass by Fast Pyrolysis6 pages

- University College of Engineering, Rajasthan Technical University, Kota, Rajasthan, IndiaNo ratings yetUniversity College of Engineering, Rajasthan Technical University, Kota, Rajasthan, India5 pages

- Advanced Process Modeling and Optimization of Amine-Based CarbonNo ratings yetAdvanced Process Modeling and Optimization of Amine-Based Carbon190 pages

- Production of 20 000 MTPD of Methyl Tertiary Butyl Ether From Methanol and Butylenes by Catalytic ConversionNo ratings yetProduction of 20 000 MTPD of Methyl Tertiary Butyl Ether From Methanol and Butylenes by Catalytic Conversion177 pages

- Polymer Composite Material for the Manufacture ofNo ratings yetPolymer Composite Material for the Manufacture of7 pages

- Handbook of Composites from Renewable Materials, Design and ManufacturingFrom EverandHandbook of Composites from Renewable Materials, Design and ManufacturingNo ratings yet

- Ultrasonic: 1. Piezoelectric Generator 2. Magnetostrictive GeneratorNo ratings yetUltrasonic: 1. Piezoelectric Generator 2. Magnetostrictive Generator6 pages

- Interference and Diffraction: Division of WavefrontNo ratings yetInterference and Diffraction: Division of Wavefront3 pages

- Determination of Specific Charge by Thomson's MethodNo ratings yetDetermination of Specific Charge by Thomson's Method5 pages

- Metrolgy: Measurement Instrument and GaugesNo ratings yetMetrolgy: Measurement Instrument and Gauges5 pages

- Foundry Equipments: Casting and ApplicationsNo ratings yetFoundry Equipments: Casting and Applications5 pages

- HKKJRH Foekuirru Izkfìdjæ: Airports Authority of India Notice Revised Answer KeyNo ratings yetHKKJRH Foekuirru Izkfìdjæ: Airports Authority of India Notice Revised Answer Key52 pages

- 2018 - 10 - Assistant Engineer (Mechanical) - Fnalanswerkey - Withquestion PDFNo ratings yet2018 - 10 - Assistant Engineer (Mechanical) - Fnalanswerkey - Withquestion PDF18 pages

- Kamdar Et Al 2023 Use of Mesquite Hardwood Derived Biochar For Stabilization and Solidification of Lead ContaminatedNo ratings yetKamdar Et Al 2023 Use of Mesquite Hardwood Derived Biochar For Stabilization and Solidification of Lead Contaminated9 pages

- Technical Review On Biomass Conversion Processes Into Required Energy FormNo ratings yetTechnical Review On Biomass Conversion Processes Into Required Energy Form6 pages

- Nanobiochar and Biochar Based NanocompositesNo ratings yetNanobiochar and Biochar Based Nanocomposites12 pages

- Final Year Project Charles Daniel ChrisNo ratings yetFinal Year Project Charles Daniel Chris49 pages

- Alternative Fuel Produced From Thermal Pyrolysis of Waste Tires andNo ratings yetAlternative Fuel Produced From Thermal Pyrolysis of Waste Tires and9 pages

- Instant Download Drying of biomass, biosolids, and coal: for efficient energy supply and environmental benefits First Edition Shusheng Pang PDF All Chapters100% (2)Instant Download Drying of biomass, biosolids, and coal: for efficient energy supply and environmental benefits First Edition Shusheng Pang PDF All Chapters55 pages

- Epitaxial Growth Mechanism of Pb (Zr,Ti) O3 Thin Films on SrTiO3 by Chemical Solution Deposition via Self-Organized Seed Layer (0118老師給的)No ratings yetEpitaxial Growth Mechanism of Pb (Zr,Ti) O3 Thin Films on SrTiO3 by Chemical Solution Deposition via Self-Organized Seed Layer (0118老師給的)11 pages

- Enthalpy For Pyrolysis For Several Types of BiomassNo ratings yetEnthalpy For Pyrolysis For Several Types of Biomass7 pages

- Reactivity of Coal Gasification With Steam and CO2No ratings yetReactivity of Coal Gasification With Steam and CO29 pages

- An Overview On The Preparation of Rice Husk BiocharNo ratings yetAn Overview On The Preparation of Rice Husk Biochar11 pages

- Practical Manual ON Renewable Energy and Green TechnologyNo ratings yetPractical Manual ON Renewable Energy and Green Technology48 pages

- Hazardous Waste: Management and Treatment: StructureNo ratings yetHazardous Waste: Management and Treatment: Structure45 pages

- Polymer Waste: Controlled Breakdown or Recycling? by Brigitta BODZAY and György BÁNHEGYI, Ijdst v22n2 (2016) Paper 6No ratings yetPolymer Waste: Controlled Breakdown or Recycling? by Brigitta BODZAY and György BÁNHEGYI, Ijdst v22n2 (2016) Paper 640 pages

- Synthesis of Carbon Matrix With Tunable Carbide Formation Ability For Reactive Infiltration TechniquesNo ratings yetSynthesis of Carbon Matrix With Tunable Carbide Formation Ability For Reactive Infiltration Techniques6 pages

- Plastic Waste Management Assignment-Week 6: NPTEL Online Certification Courses Indian Institute of Technology KharagpurNo ratings yetPlastic Waste Management Assignment-Week 6: NPTEL Online Certification Courses Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur14 pages

- Raw Material Specification Sheet - Petroflo 20Y3437 NewRaw Material Specification Sheet - Petroflo 20Y3437 New

- Pyrolysis of Waste Tires, A Modeling and Parameter Estimation Study Using Aspen Plus PDFPyrolysis of Waste Tires, A Modeling and Parameter Estimation Study Using Aspen Plus PDF

- Cts Automata Fix Previous Error Debugging: Cognizant Telegram GroupCts Automata Fix Previous Error Debugging: Cognizant Telegram Group

- Design and Fabrication of Extraction of Fuel From Waste Plastics Using PyrolysisDesign and Fabrication of Extraction of Fuel From Waste Plastics Using Pyrolysis

- Calcium Carbonate (CaCO3) Nanoparticle Filled PolypropyleneCalcium Carbonate (CaCO3) Nanoparticle Filled Polypropylene

- 2sustainable Utilization of Value-Added Products From The Catalytic2sustainable Utilization of Value-Added Products From The Catalytic

- Production of Fuels From Nigeria's Untapped Waste Wealth' Using PyrolysisProduction of Fuels From Nigeria's Untapped Waste Wealth' Using Pyrolysis

- 4. Kinetics and fuel properties of the oil obtained from the pyrolysis of4. Kinetics and fuel properties of the oil obtained from the pyrolysis of

- An Introduction To Molecular Thermal Energy Storage: A Seminar Report Submitted ToAn Introduction To Molecular Thermal Energy Storage: A Seminar Report Submitted To

- Analysis and Production of Fuel From Waste Plastic Using Thermal Cracking ProcessAnalysis and Production of Fuel From Waste Plastic Using Thermal Cracking Process

- Waste Plastic Pyrolysis Oil As Alternative For SI and CI EnginesWaste Plastic Pyrolysis Oil As Alternative For SI and CI Engines

- Characterization Studies Waste Plastic Oil and Its BlendsCharacterization Studies Waste Plastic Oil and Its Blends

- Production of Liquid Fuel From Plastic Waste Using Integrated Pyrolysis Method With Refinery Distillation Bubble Cap Plate Column-1Production of Liquid Fuel From Plastic Waste Using Integrated Pyrolysis Method With Refinery Distillation Bubble Cap Plate Column-1

- Feasibility Study of Conversion of Selected Plastic in To Synthetic Fuel (Synthetic Diesel) - A ReviewFeasibility Study of Conversion of Selected Plastic in To Synthetic Fuel (Synthetic Diesel) - A Review

- Simulation Study For Production of Hydrocarbons From WasteSimulation Study For Production of Hydrocarbons From Waste

- Engineering Journal Duplex Stainless Steel Self-Ligating Orthodontic Brackets by Micro-Powder Injection MouldingEngineering Journal Duplex Stainless Steel Self-Ligating Orthodontic Brackets by Micro-Powder Injection Moulding

- The University of Bradford Institutional RepositoryThe University of Bradford Institutional Repository

- Low-Impact Friction Materials For Brake Pads: Andrea BonfantiLow-Impact Friction Materials For Brake Pads: Andrea Bonfanti

- University College of Engineering, Rajasthan Technical University, Kota, Rajasthan, IndiaUniversity College of Engineering, Rajasthan Technical University, Kota, Rajasthan, India

- Advanced Process Modeling and Optimization of Amine-Based CarbonAdvanced Process Modeling and Optimization of Amine-Based Carbon

- Production of 20 000 MTPD of Methyl Tertiary Butyl Ether From Methanol and Butylenes by Catalytic ConversionProduction of 20 000 MTPD of Methyl Tertiary Butyl Ether From Methanol and Butylenes by Catalytic Conversion

- Handbook of Composites from Renewable Materials, Design and ManufacturingFrom EverandHandbook of Composites from Renewable Materials, Design and Manufacturing

- Thermal Spray Coatings: Materials, Techniques & ApplicationsFrom EverandThermal Spray Coatings: Materials, Techniques & Applications

- Ultrasonic: 1. Piezoelectric Generator 2. Magnetostrictive GeneratorUltrasonic: 1. Piezoelectric Generator 2. Magnetostrictive Generator

- Interference and Diffraction: Division of WavefrontInterference and Diffraction: Division of Wavefront

- Determination of Specific Charge by Thomson's MethodDetermination of Specific Charge by Thomson's Method

- HKKJRH Foekuirru Izkfìdjæ: Airports Authority of India Notice Revised Answer KeyHKKJRH Foekuirru Izkfìdjæ: Airports Authority of India Notice Revised Answer Key

- 2018 - 10 - Assistant Engineer (Mechanical) - Fnalanswerkey - Withquestion PDF2018 - 10 - Assistant Engineer (Mechanical) - Fnalanswerkey - Withquestion PDF

- Kamdar Et Al 2023 Use of Mesquite Hardwood Derived Biochar For Stabilization and Solidification of Lead ContaminatedKamdar Et Al 2023 Use of Mesquite Hardwood Derived Biochar For Stabilization and Solidification of Lead Contaminated

- Technical Review On Biomass Conversion Processes Into Required Energy FormTechnical Review On Biomass Conversion Processes Into Required Energy Form

- Alternative Fuel Produced From Thermal Pyrolysis of Waste Tires andAlternative Fuel Produced From Thermal Pyrolysis of Waste Tires and

- Instant Download Drying of biomass, biosolids, and coal: for efficient energy supply and environmental benefits First Edition Shusheng Pang PDF All ChaptersInstant Download Drying of biomass, biosolids, and coal: for efficient energy supply and environmental benefits First Edition Shusheng Pang PDF All Chapters

- Epitaxial Growth Mechanism of Pb (Zr,Ti) O3 Thin Films on SrTiO3 by Chemical Solution Deposition via Self-Organized Seed Layer (0118老師給的)Epitaxial Growth Mechanism of Pb (Zr,Ti) O3 Thin Films on SrTiO3 by Chemical Solution Deposition via Self-Organized Seed Layer (0118老師給的)

- Enthalpy For Pyrolysis For Several Types of BiomassEnthalpy For Pyrolysis For Several Types of Biomass

- Reactivity of Coal Gasification With Steam and CO2Reactivity of Coal Gasification With Steam and CO2

- An Overview On The Preparation of Rice Husk BiocharAn Overview On The Preparation of Rice Husk Biochar

- Practical Manual ON Renewable Energy and Green TechnologyPractical Manual ON Renewable Energy and Green Technology

- Hazardous Waste: Management and Treatment: StructureHazardous Waste: Management and Treatment: Structure

- Polymer Waste: Controlled Breakdown or Recycling? by Brigitta BODZAY and György BÁNHEGYI, Ijdst v22n2 (2016) Paper 6Polymer Waste: Controlled Breakdown or Recycling? by Brigitta BODZAY and György BÁNHEGYI, Ijdst v22n2 (2016) Paper 6

- Synthesis of Carbon Matrix With Tunable Carbide Formation Ability For Reactive Infiltration TechniquesSynthesis of Carbon Matrix With Tunable Carbide Formation Ability For Reactive Infiltration Techniques

- Plastic Waste Management Assignment-Week 6: NPTEL Online Certification Courses Indian Institute of Technology KharagpurPlastic Waste Management Assignment-Week 6: NPTEL Online Certification Courses Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur