L 6: S G O:: How Do The Outcomes of Our Actions Unfold As Time Passes?

Uploaded by

Urban EcoLab CurriculumCopyright:

Available Formats

L 6: S G O:: How Do The Outcomes of Our Actions Unfold As Time Passes?

Uploaded by

Urban EcoLab CurriculumOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

L 6: S G O:: How Do The Outcomes of Our Actions Unfold As Time Passes?

Uploaded by

Urban EcoLab CurriculumCopyright:

Available Formats

Seven Generations

Module 8 Lesson 6

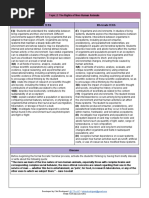

LESSON 6: SEVEN GENERATIONS OVERVIEW:

In this lesson, students will consider the benefits and trade-offs of their action plans over an extended period of time. Students will consider and discuss a quote attributed to the Great Law of the Iroquois and predict and complete a timeline of the benefits and tradeoffs of their action plan for ecological communities (human and non-human) seven generations into the future. This lesson allows you and your students to consider the future impact of their action plans, and allows your students to consider making any modifications to their action plans.

SUB-QUESTION:

How do the outcomes of our actions unfold as time passes?

Ways of Knowing Urban Ecology:

Understand Talk Do

Students will Understand that the final product of an action plan will change and have consequences over time. (ecosystem change) Discuss the nature of benefits and trade-offs for choices and actions as time progresses. Predict the benefits and trade-offs of their actions as embodied in their action plans for future generations of members of the ecological community, human and non-human. Complete a timeline to chart the benefits and trade-offs of their action plans over seven generations. Consider the consequences of an action plan over time.

Act

SAFETY GUIDELINES:

No safety precautions are needed.

PREPARATION:

Gather materials Reserve computer lab, if necessary Time: 1 - 45 minute period Materials: Activity 6.1 Seven Generations quote, written on the board or projected

Seven Generations

Module 8 Lesson 6

Activity 6.2 Student Timeline Sheets

INSTRUCTIONAL SEQUENCE

Activity 6.1: Introducing The Seven Generations Idea 1. Direct students to the quote attributed to the Great Law of the Iroquois:

In every deliberation we must consider the impact on the seventh generation even if it requires having skin as thick as the bark of a pine

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seven_generation_sustainability) TEACHER BACKGROUND KNOWLEDGE The Iroquois were a confederacy of Native American Nations in New York State, Wisconsin, Ontario and Quebec. The Iroquois Constitution, or Great Binding Law (Gayanashagowa; http://www.indigenouspeople.net/iroqcon.htm), to which this quote is attributed, is one of the documents which strongly influenced the US Constitution. While this quote is often attributed to this document, it may not be taken directly from it (translators may have taken license). For more information on the Gayanashagowa and an interview with Dr. Donald Grinde, Jr., a history professor at the University of Vermont, visit http://www.spiritofmaat.com/archive/may2/iroquois.htm. He discusses an Iroquois sense of ecocentrism and how the Great Binding Law influenced the authors of the US Constitution. 2. Ask your students to consider what this quote may be referring to. You may want to discuss this quote in two parts, on either side of the ellipsis (). You can write students ideas on the board as the discussion continues. The first part of the quote, for the purposes of the action plan, refers to the idea that we should consider the benefits and trade-offs of our decisions and actions over an extended period of time into the future. The second part refers to the idea that we really need to be honest about the trade-offs and how there may be negative consequences to our wellintentioned plans and actions.

3. Ask your students to think about how their action plans may have benefits and trade-offs for future generations of the ecological community, both human (socially, economically, etc.) and non-human (plants, animals, etc.).

Seven Generations

Module 8 Lesson 6

Activity 6.2: Constructing the Timeline to the Seventh Generation 1. Distribute the Seven Generations timeline sheet to your students. You may ask students to work individually, in small groups, or as a class, although each student should have their own timeline sheet. 2. Note that there are no absolute time designations on the timeline sheet. You may want to decide ahead of time how long each generation is, or discuss with your class what an appropriate length of time would be. A generation is technically defined as, the average interval of time between the birth of parents and the birth of their offspring, or for humans, 30 years (http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/generation). Seven generations, therefore, would be approximately 210 years. Each segment of the timeline would be 30 years. This length of time may be difficult for high school students to visualize and predict, but may also be rewarding in the end. 3. Ask your students to complete their timelines, considering both benefits and trade-offs of their action plans for both human and non-human members of the ecological community. Remind them to be truthful and honest, especially when considering trade-offs, and to have skin as thick as pine bark. 4. Remind your students of the biophysical and social drivers from the Land Use Module, and to consider the benefits and trade-offs along these drivers.

Seven Generations

Module 8 Lesson 6

Teacher Background Knowledge

These are the biophysical and social drivers from Module 2, Land Use. Biophysical Drivers:

1. Climate: factors such as precipitation patterns and temperature can influence the way that land is 2. 3. 4. 5.

used by ensuring that buffer flood zones are maintained around rivers. Nutrient cycling: Critical nutrients in an ecosystem such as nitrogen (found in proteins) and phosphorus (found in DNA) can severely limit the growth of populations. The rates at which nutrients move through an ecosystem can alter the distribution and density of organisms Geologic features and topography: being surrounded by water or mountains/hills on more than one side can constrain urban growth and promote denser growth patterns, while a flatter topography can potentially result in easier access to developable land and lower development costs Natural history: The historical composition of plant and animal populations can influence land use patterns. Fore instance, fire dominated ecosystems have a very different pattern of forest growth than do moist woodlands. Community composition (ecological): Referring to the distribution and abundance of species, the healthiest ecosystems have a complex community structure that is resilient to disturbance.

Social Drivers:

1. Governance: the type of leadership in a city, state, and/or country can influence the way that land 2. 3.

is used and what the priorities are in land use planning. This is especially true with respect to the degree to which neighborhoods can chart their own futures. Land use policies: The policies, rules, and restrictions in place inform the way that land is used and where a (human) community's priorities are placed. This is typically where we consider zoning regulations as having their greatest impacts. Human demography: a growing human population requires a greater amount of land or a denser urbanization pattern. The age distribution of the population has a huge influence as well. School system budgets are very different in retirement communities versus neighborhoods of starter homes and apartments. Economics: higher income areas are usually provided with land use patterns aligned with the desires of the local human population (e.g., more parks, bigger yards, shops, etc.), while lower income areas are usually provided with less desirable land use patterns (industry, fewer parks, higher population densities, etc.) Cultural practices and beliefs: the larger cultural ideas around land use greatly informs the way that land is used and what the priorities are in land use patterns. If a culture favors public interaction, then common green space is more likely to be built in that neighborhood. Social history: The historical record legacy of a community influences land use patterns. The mill towns of Massachusetts have factories along the waterfront that remain to modern times, even though the rivers are no longer used for hydropower or transportation .

4.

5. 6.

Seven Generations

Module 8 Lesson 6

5. If students are completing individually or in small groups, reconvene and ask individuals or small groups to discuss their timelines with the class. Concluding the Lesson 1. Ask your students what they think about considering the benefits and tradeoffs of environmental action not just in the present, but for the future. Has their ideas around their action plan changed or shifted? If so, allow your students to update their action plan(s). If the discussion becomes negative (i.e. their action will not have a positive impact), remind them that imperfect environmental action toward a just and good future is better than no action at all. Inaction effectively allows others to take advantage and potentially cause more environmental and social degradation and harm. Even small actions have a positive impact, especially if many people complete small positive actions. Together those small impacts will have a large one.

You might also like

- Wassce Waec Integrated Science Teaching Syllabus PDFNo ratings yetWassce Waec Integrated Science Teaching Syllabus PDF68 pages

- Excerpt From Elkhart County's Zoning OrdinanceNo ratings yetExcerpt From Elkhart County's Zoning Ordinance9 pages

- Lesson 6: C U E O:: Omplex Rban Cosystems VerviewNo ratings yetLesson 6: C U E O:: Omplex Rban Cosystems Verview8 pages

- ELC Bottle Biosphere Outline For Pitch 2018No ratings yetELC Bottle Biosphere Outline For Pitch 20186 pages

- Developed by Clint Rodriguez / / Free For Educators: @ctrodgtNo ratings yetDeveloped by Clint Rodriguez / / Free For Educators: @ctrodgt2 pages

- Sustainability Science - and What's Needed Beyond Science: Community EssayNo ratings yetSustainability Science - and What's Needed Beyond Science: Community Essay4 pages

- "Sustainable Development" A MGN 231 Project: Bachelor of Technology in Department of Computer Science EngineeringNo ratings yet"Sustainable Development" A MGN 231 Project: Bachelor of Technology in Department of Computer Science Engineering31 pages

- SOE 110 Writing Assignment Environmental JusticeNo ratings yetSOE 110 Writing Assignment Environmental Justice4 pages

- Population Dynamics for Conservation Louis W. Botsford download pdf100% (2)Population Dynamics for Conservation Louis W. Botsford download pdf41 pages

- Discussion Guide: State of The World 2010: Transforming Cultures: From Consumerism To SustainabilityNo ratings yetDiscussion Guide: State of The World 2010: Transforming Cultures: From Consumerism To Sustainability9 pages

- Grade 7: Tropical Rain Forest Ecosystem Booklet: To The TeacherNo ratings yetGrade 7: Tropical Rain Forest Ecosystem Booklet: To The Teacher7 pages

- Activity No. 1 and 2 Envi - Sci (12174)No ratings yetActivity No. 1 and 2 Envi - Sci (12174)14 pages

- Problematizing Neoliberal Biodiversity Conservation: Displaced and Disobedient KnowledgeNo ratings yetProblematizing Neoliberal Biodiversity Conservation: Displaced and Disobedient Knowledge25 pages

- L 8: H F S S O:: Esson Abitat Ragmentation and Pecies Urvival VerviewNo ratings yetL 8: H F S S O:: Esson Abitat Ragmentation and Pecies Urvival Verview6 pages

- Whitaker - Commodity Ecology Wheel (130 Version), Description, Biography, June 2019 W Prototype Link On First PageNo ratings yetWhitaker - Commodity Ecology Wheel (130 Version), Description, Biography, June 2019 W Prototype Link On First Page3 pages

- Revisiting The Commons Local Lessons, Global ChallengesNo ratings yetRevisiting The Commons Local Lessons, Global Challenges6 pages

- World Scientists ' Warning: The Behavioural Crisis Driving Ecological OvershootNo ratings yetWorld Scientists ' Warning: The Behavioural Crisis Driving Ecological Overshoot22 pages

- Streams of Revenue: The Restoration Economy and the Ecosystems It CreatesFrom EverandStreams of Revenue: The Restoration Economy and the Ecosystems It CreatesNo ratings yet

- L 6: F C C C O:: How Do Our Food Choices Impact Energy Use?No ratings yetL 6: F C C C O:: How Do Our Food Choices Impact Energy Use?9 pages

- Taking Action For Environmental Sustainability - : RecicladoresNo ratings yetTaking Action For Environmental Sustainability - : Recicladores6 pages

- Where Does Garbage Go in Massachusetts?: Module 4 Lesson 2No ratings yetWhere Does Garbage Go in Massachusetts?: Module 4 Lesson 26 pages

- What Is Type 2 Diabetes: Module 5 Lesson 7No ratings yetWhat Is Type 2 Diabetes: Module 5 Lesson 79 pages

- BEEF CATTLE BREEDER FARM ACCREDITATION PROGRAM Feb 19 2018 PDFNo ratings yetBEEF CATTLE BREEDER FARM ACCREDITATION PROGRAM Feb 19 2018 PDF1 page

- Dallas, TX City Plan Commission Agenda 3-21-2013.doc - CPC - Agenda - 032113No ratings yetDallas, TX City Plan Commission Agenda 3-21-2013.doc - CPC - Agenda - 032113286 pages

- Rezoning Application RZ100320 (Beedie Group - 60 Avenue)No ratings yetRezoning Application RZ100320 (Beedie Group - 60 Avenue)13 pages

- Resource Conservation Techniques in Rice Wheat Cropping System100% (4)Resource Conservation Techniques in Rice Wheat Cropping System47 pages

- St. Croix County Property Transfers For July 20-26 2020No ratings yetSt. Croix County Property Transfers For July 20-26 202038 pages

- Unit 4-Urban Planning & Urban Renewal-Urban Renewal 2 PDF100% (1)Unit 4-Urban Planning & Urban Renewal-Urban Renewal 2 PDF14 pages

- Agriculture and The City A Method For Sustainable Planning of New Forms of Agriculture in Urban Contexts PDFNo ratings yetAgriculture and The City A Method For Sustainable Planning of New Forms of Agriculture in Urban Contexts PDF14 pages

- An Analysis On Land Use Land Cover Using Remote Sensing Techniques A Case Study of Pudukkottai District, Tamil Nadu, I PDFNo ratings yetAn Analysis On Land Use Land Cover Using Remote Sensing Techniques A Case Study of Pudukkottai District, Tamil Nadu, I PDF5 pages

- Wassce Waec Integrated Science Teaching Syllabus PDFWassce Waec Integrated Science Teaching Syllabus PDF

- Developed by Clint Rodriguez / / Free For Educators: @ctrodgtDeveloped by Clint Rodriguez / / Free For Educators: @ctrodgt

- Sustainability Science - and What's Needed Beyond Science: Community EssaySustainability Science - and What's Needed Beyond Science: Community Essay

- "Sustainable Development" A MGN 231 Project: Bachelor of Technology in Department of Computer Science Engineering"Sustainable Development" A MGN 231 Project: Bachelor of Technology in Department of Computer Science Engineering

- Population Dynamics for Conservation Louis W. Botsford download pdfPopulation Dynamics for Conservation Louis W. Botsford download pdf

- Discussion Guide: State of The World 2010: Transforming Cultures: From Consumerism To SustainabilityDiscussion Guide: State of The World 2010: Transforming Cultures: From Consumerism To Sustainability

- Grade 7: Tropical Rain Forest Ecosystem Booklet: To The TeacherGrade 7: Tropical Rain Forest Ecosystem Booklet: To The Teacher

- Problematizing Neoliberal Biodiversity Conservation: Displaced and Disobedient KnowledgeProblematizing Neoliberal Biodiversity Conservation: Displaced and Disobedient Knowledge

- L 8: H F S S O:: Esson Abitat Ragmentation and Pecies Urvival VerviewL 8: H F S S O:: Esson Abitat Ragmentation and Pecies Urvival Verview

- Whitaker - Commodity Ecology Wheel (130 Version), Description, Biography, June 2019 W Prototype Link On First PageWhitaker - Commodity Ecology Wheel (130 Version), Description, Biography, June 2019 W Prototype Link On First Page

- Revisiting The Commons Local Lessons, Global ChallengesRevisiting The Commons Local Lessons, Global Challenges

- World Scientists ' Warning: The Behavioural Crisis Driving Ecological OvershootWorld Scientists ' Warning: The Behavioural Crisis Driving Ecological Overshoot

- Streams of Revenue: The Restoration Economy and the Ecosystems It CreatesFrom EverandStreams of Revenue: The Restoration Economy and the Ecosystems It Creates

- L 6: F C C C O:: How Do Our Food Choices Impact Energy Use?L 6: F C C C O:: How Do Our Food Choices Impact Energy Use?

- Taking Action For Environmental Sustainability - : RecicladoresTaking Action For Environmental Sustainability - : Recicladores

- Where Does Garbage Go in Massachusetts?: Module 4 Lesson 2Where Does Garbage Go in Massachusetts?: Module 4 Lesson 2

- BEEF CATTLE BREEDER FARM ACCREDITATION PROGRAM Feb 19 2018 PDFBEEF CATTLE BREEDER FARM ACCREDITATION PROGRAM Feb 19 2018 PDF

- Dallas, TX City Plan Commission Agenda 3-21-2013.doc - CPC - Agenda - 032113Dallas, TX City Plan Commission Agenda 3-21-2013.doc - CPC - Agenda - 032113

- Rezoning Application RZ100320 (Beedie Group - 60 Avenue)Rezoning Application RZ100320 (Beedie Group - 60 Avenue)

- Resource Conservation Techniques in Rice Wheat Cropping SystemResource Conservation Techniques in Rice Wheat Cropping System

- St. Croix County Property Transfers For July 20-26 2020St. Croix County Property Transfers For July 20-26 2020

- Unit 4-Urban Planning & Urban Renewal-Urban Renewal 2 PDFUnit 4-Urban Planning & Urban Renewal-Urban Renewal 2 PDF

- Agriculture and The City A Method For Sustainable Planning of New Forms of Agriculture in Urban Contexts PDFAgriculture and The City A Method For Sustainable Planning of New Forms of Agriculture in Urban Contexts PDF

- An Analysis On Land Use Land Cover Using Remote Sensing Techniques A Case Study of Pudukkottai District, Tamil Nadu, I PDFAn Analysis On Land Use Land Cover Using Remote Sensing Techniques A Case Study of Pudukkottai District, Tamil Nadu, I PDF