XBRL

XBRL

Uploaded by

Shi SyngeCopyright:

Available Formats

XBRL

XBRL

Uploaded by

Shi SyngeCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

XBRL

XBRL

Uploaded by

Shi SyngeCopyright:

Available Formats

XBRL-Beyond the Basics by Bizarro, Pascal A, Garcia, Andy | May 2010

Benefits for Financial Reporting and Auditing Those CPAs who understand Extensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL) can use it to automate portions of the accounting and financial reporting processes, as well as enhance auditing capabilities. The SEC has mandated that all U.S. publicly traded companies file their financial statements using XBRL by the year 20 11. Large accelerated filers using U.S. GAAP were required to begin reporting in XBRL in 2009 (www.tryxbrl.com). The SEC's mandate may be based on the way that XBRL enables organizations to take greater advantage of Internet-based technologies without using proprietary products and services that result in dependence on a specific platform or vendor. According to a recent survey by the Institute of Internal Auditors, 51% of internal auditors confess that they lack a good understanding of XBRL technology and bemoan meir absence from the financial reporting process using XBRL (Stephen Taub, "In Data Tagging, Auditore Feel Left Out," www.CFO.com, October 16, 2008). Auditors are interested in receiving more guidance on how to use XBRL throughout the different phases of the financial reporting supply chain. Articles on XBRL often list and describe the benefits of XBRL for the financial reporting of aggregated or summarized financial information only. This article goes back to the start of the financial reporting process - the transaction-level data - and shows how XBRL can be used to store these data in a systems-independent manner that can be used to automate the aggregation process (i.e., consolidating and summarizing to the financial statements). XBRL can do this automatically for multiple reporting formats (e.g., U.S. GAAP and IFRS). XBRL also has benefits for auditors, both internal and external. The implementation of XBRL, however, presents certain challenges that all CPAs should be aware of. XBRL for Financial Reporting XBRL can be used to distribute summarized financial statement information. The data hi an XBRL instance document can be used to generate hard copies of the financial statements in whatever form the user selects, or downloaded directly for other purposes (e.g., financial statement analysis). XBRL is an XML-based application that supports information modeling (e.g., data structure, constraints, and data types) and the expression of accounting concepts required in financial reporting (e.g., cash and cash equivalents). The original purpose of XBRL was to define, store, and exchange summarized financial information, such as that contained in the financial statements. It is commonly referred as XBRL Financial Reporting (FR). The data structure is defined by the XBRL Specification 2.1 and composed of a series of taxonomies (available at www.xbrl.org) that define

financial reporting concepts and their relationships. They are equivalent to XML schemas, which define the structure, content, and semantics of XML instance documents. These accounting concepts are arranged in a hierarchical structure using a parent-child relationship. Exhibit I illustrates the typical process of using XBRL FR to generate and distribute financial statement information. First, the company maps the financial statements to the standard taxonomy following the company's chosen reporting framework (e.g., GAAP). Next, a taxonomy entity-specific extension is created to address the company's own accounting concepts and adjusted taxonomy relationships. This collection of taxonomies is called a discoverable taxonomy set (DTS). An XBRL instance document is created based on financial data stored in the reporting system. The DTS is then used to validate the instance document. This validation process is critical to guarantee that the data are correct and complete. Data validation takes place in two stages: 1) XML "well-formedness," DTS discovery, and XML schema validation; and 2) XBRL validation and consistency checking. During the first stage, the document is checked to ensure that it is a valid, wellformed XML document - meaning that the opening tag matches the corresponding closing tag and conforms to the relevant XML schemas, including the specific XBRL taxonomy for the entity. During the second stage of validation checks, the data are checked for conformance with the validation and consistency rules laid down in the XBRL Specification. These rules ensure that the submitted document is a valid XBRL instance document, and that it conforms to the appropriate (userspecified) taxonomy. In the final step, validated XBRL instance documents can be supplied to users in two ways: 1) instance documents can be imported into any application that supports the technology for analysis (e.g., financial analysis, audit programs), or 2) Extensible StyLesheet Language (XSL) style sheets coupled with XSL Transformations can be used to render the instance documents according to the user's specifications (e.g., textual, tabular, graphical). Users could be regulators, shareholders, or potential investors. The cote syntax for XBRL FR instance documents is defined in the selected taxonomy. Exhibit 2 represents the data model for a typical XBRL FR instance document. Element terminology is used to represent XML tags in the implementation of an XBRL instance document Every XBRL FR instance document starts with the xbri root element The link-SchemaRef element is the fust child element nested within the xbrl root element. This element points to a taxonomy that supporte the concepts used in the instance document An XBRL instance document can contain multiple context, unit, and item elements. The context element contains information about the entity being described (the subordinate entity element), the reporting period (the subordinate period element), and the optional reporting scenario. This information is required to obtain full understanding of a business fact captured through the XBRL item element The entity element describes the organization (e.g., corporation, governmental agency, or individual department) to which the financial fact applies; it also contains an identifier element and possibly multiple optional segment elements. The period element contains the instant element (e.g., cash balance at a point in time) or an interval of time with startDate and endDate subelements (e.g., sales over a period of time) for reference by an item element through the contextRef attribute. The optional scenario element allows financial facts to be reported as actual, budgeted, restated, or

pro forma. The unit element specifies the units in which the business facts are measured; this contains a single measure (e.g., currencies) or several measures combined with the multiplication and division operator elements (e.g., earnings per share). The item element represents business facts corresponding to accounting concepts defined in the chosen taxonomy; item also contains the following attributes to provide additional information: decimals attribute to specify how many decimal places, contextRef attribute to link the reported information with a specific context element, and unitRef attribute to identify the corresponding unit element. The link: footnoteLink element contains locator elements that point to the business facts to provide footnote information. Exhibit 3 shows a sample XBRL FR instance document representing a partly displayed, unaudited consolidated balance sheet Two context elements are created to store the financial data for two reporting . years (Contextl for the year ending September 30, 2008, and Context! for the year ending December 31, 2007). These two contexts are referred to in the individual financial items through their id attributes. One unit measure is defined (iso4217:USD for U.S. dollar currency). Exhibit 3 also illustrates the use of footnotes through the Unk:footnote1Jnk tag. XBRL Standardized Global Ledger XBRL FR has recently been extended beyond its original purpose. XBRL FR only provides a standardized way to exchange aggregated or summarized financial statement information. Subsequent development efforts have led to the creation of XBRL Global Ledger (GL), including a sp cule set of taxonomies that make many additional capabilities available. XBRL GL was created as a way to store financial and nonfinancial data at the transactional data level. Organizations can adopt this XBRL GL application to standardize the creation, storage, and exchange of their entire accounting database, making the transactional data independent of the systems that generate and use the data. In the absence of XBRL FR and GL, the information flow from the capture of transaction data to the production of consolidated financial reports often requires the manual re-entry of data, making the process error-prone, redundant, and inefficient. The XBRL GL Core Taxonomy is a stand-alone taxonomy, appropriate for representing basic accounting databases and business transactions (www.xbrl.org/ GLTaxonomy). To meet company-specific needs, XBRL GL Core can be accompanied with additional add-on modules, such as the Advanced U.S. Accounting (GL-USK), Multi-currency (GL-MUC), and Advanced Business Concepts (GLBUS) taxonomies, forming what is called the XBRL GL Palette (company taxonomy extension). The XBRL GL Core Taxonomy can work either alone or in combination with these add-on taxonomies to store transactional data coming from different systems, forming a central repository and an automated audit trail (Neal J. Hannon, "XBRL GL: The General Ledger Gets Its Groove," Strategic Finance, September 2005). These taxonomies are designed to standardize the collection and storage of accounting and operational data for consolidation, data transfer, archival, and audit purposes. In accordance with the XBRL GL Palette, the XBRL GL instance document is divided into sections modeling a typical accounting system (Exhibit 4). The root element of XBRL GL, as for any XBRL document, is the xbrl element, and it includes multiple context and unit elements. From the root

element, multiple accountingEntries elements can be specified to represent both transactions and master files. For each accountingEntries element, three child elements are created. The documenrlnfo element holds information about the accountingEntries in question. The critical element within the documentlnfo element is the entriesType, which determines what kind of data the accountingEntries relate to (e.g., chart of accounts, journal entry, or other business documents). The entitylnformalion element contains information about the reporting organization. The entryHeaderetement is the repository for journal entries, source document data, or individual accounts. It also stores the header of journalizing (source JournallD, entryType, and entryOrigifl), and holds multiple entoyDetail elements. XBRL GL applies the journal entry analogy as a framework to capture accounting master files, asset listings, and journal entries. Each eniryOetail element references one or multiple account elements to allow reporting under different sets of rules (e.g.( U.S. GAAP and IFRS). The xbrllnfo element ties a particular financial account to multiple reporting taxonomies, such as Unking an XBRL GL to the corresponding XBRL FR. The identiflerReference element refers to a customer, vendor, or employee. Finally, the measurable element stores data at the line level. The measurable element may represent inventory, services, supplies, processes, fixed assets, and other things that are matched to a code as opposed to an account; it collects numeric information with the measurableQuantity element. A typical invoice would have at least one measurable per entryDetail line. The amount element would be the product of the measurableQuantity element and measurableCostPerUnit element. There are several additional elements wit iin the measurable structure, such as the necessary measurableDescription element and the optional measurableUnitOfMeasure elementTo illustrate the application of XBRL GL instance documents to store business data, Exhibits 5 and 6 represent samples of a chart of accounts and a customer invoice, respectively. In the chart of accounts sample (Exhibit 5), the XBRL GL/FR connection is expressed by the use of the xbrUnfo element that includes the xbrlTaxonomy and xbrlElement elements for the U.S. and international accounting principles (highlighted). Inside the customer invoice sample (Exhibit 6), two interesting elements included in the enlryHeader element are worth mentioning for audit trail purposes (highlighted). First, the entryOrigin element captures whether the data came in from another automated system or were manually entered. Second, information can be maintained regarding the physical location of source documents (e.g., a filing cabinet or electronic storage), helping an auditor find the source documentation. XBRL GL and XBRL FR Integration The real power of XBRL lies in integrating XBRL GL with XBRL FR. Exhibit 7 represents the integration of XBRL FR and XBRL GL into a combined system with the benefit of single entry (Hannon 2005); streamlined data flow without user intervention to reduce errors, inefficiency, and uncontrolled spreadsheet proliferation. A complete automated audit trail is discussed below. XBRL GL/FR has considerable benefits for organizations adopting the technology. First, it links the financial statements to the underlying transactional data. XBRL facilitates the flow of business information through the financial reporting supply chain and provides an automated audit trail (D. Amrhein and S.M. Farewell, "Using REA as an Ontology for Creating Extensions to the XBRL GL

Taxonomy," presented at the 7th Annual Research Workshop on Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technologies in Accounting, Auditing, and Tax, Anaheim, CaUf., August 2, 2008; Gianluca Garbellotto, "The Global Ledger for Financial Services," Strategic Finance, April 2007). The audit trail is the primary source of necessary evidence to support a CPA's opinion about the fair presentation of the financial statements (E e E. Cohen, "The Need for and Issues Surrounding the Seamless Audit Trail," www.oasis-open.org, 2008). That evidence is preserved inside XBRL GL and XBRL FR instance documents and validated by their corresponding taxonomies and schemas. Second, XBRL GUFR has the ability to automatically consolidate financial data from subsidiaries to a parent company. Because XBRL-tagged transactionai data are independent of the system that created them, data integration is greatly enhanced, offering interoperability between applications within the company's operational environment and between regulatory requirements (Garbellotto 2007). Business information hosted by the individual subsystems stored in XBRL format can be imported directly into XBRL GL instance documents. XBRL-tagged transactional data can then be shared across diverse hardware and software systems without human intervention (Hannon 2005; Mike Willis and William M. Sinnett, "XBRL: Not Just for External Reporting," Financial Executives International, May 2008). Although automating data collection may not sound like a major benefit, consider the following: According to Fonester Research data from 2002, companies spend $404 billion paying workers to find and rekey information, representing 1 1% of all wages paid in the United States (Stephanie Farewell and Robert Pinsker, "XBRL and Financial Information Assurance Services," TTi^ CPA Journal, May 2005). Third, XBRL CSJFR provides a means to validate the content and structure of an instance document against standardized taxonomies or extensions of those taxonomies. Finally, XBRL GL/FR has the potential to change how information is aggregated, consolidated, and shared within and across organizations (Amrhein and Farewell 2008). Through enhanced data flow and data sharing, XBRL provides support for both financial reporting and audit processes. XBRL GL was developed to represent transactional data captured and processed by accounting systems and to generate financial and nonfinancial reporting. Structure is provided by the XBRL GL Core taxonomy, which is used to generate instance documents representing charts of accounts, the mappings between charts of accounts, and the mappings from charts of accounts to reporting taxonomy concepts, creating an audit trail. In today's reporting environment, one of the big advantages of XBRL GL taxonomies is the mapping of a particular transaction to multiple taxonomies so the same data can be included in multiple reporting document instances. Thus, the XBRL GL/FR integration can aggregate transactional data to multiple reporting taxonomies, such as U.S. GAAP, IFRS, or industry-specific formats, enabling automated reconciliation between different sets of reporting rules. Benefits of XBRL for Auditors Improving data analysis. Auditors using XBRL can get error-free financial data faster and spend more time performing higher-level investigative tasks and analyses. The data can be checked for accuracy automatically via XBRL's data and taxonomy validation processes. XBRL enables

auditors to quickly and reliably obtain key financial metrics and incorporate data from statistical models, rating agencies, market sources, and other third parties easily, as well as quickly perform other analytical procedures and make critical judgments regarding risk assessment and subsequent audit effort. In short, XBRL can free resources from low-value-added manual processes to higher-value-added aspects of analysis, review, reporting, and decision making. Better risk assessment. Regardless of the kind of risk assessment to be performed, XBRL can make the process faster, more accurate, more comprehensive, and more current Risk assessment is faster and more accurate because of improved data flow and data sharing. It can be more comprehensive and up-to-date because more information can be used in risk assessment models, and that data can be updated in close to real time. Risk assessment using XBRL financial information can increase the quality, timeliness, and frequency of risk assessment, while decreasing the overall cost of risk assessment. When older financial information is used for risk assessment, it can distort the current financial status and inaccurately describe the underlying economic reality; an organization's financial condition can change quickly. The greatest danger in risk assessment is mat noncurrent information may cause errors in an auditor's judgment. Accelerated implementation of continuous auditing. Although auditing each and every transaction as it occurs is impossible, an auditor can audit the internal control processes and systems used to capture and report business information. XBRL will help auditors obtain and validate business data on a much closer to realtime basis. XBRL will also give auditors an efficient means to quickly capture and audit transactions at lower materiality levels because capturing and processing the data will require less time and effort. As a result, there is a higher likelihood of discovering discrepancies or even fraud. Finding problems at earlier processing stages means that corrections can be made sooner, limiting Josses (Mike Willis and Brad Saegesser, "XBRL: Streamlining Credit Risk Management," Credit & Financial Management Review, Second Quarter, 2003). XBRL can assist in the control of data being passed from one process to the next, and might soon form the basis for a kind of process assurance. Improved internal controls. Because XBRL is machine-readable, it eliminates mathematical errors, and because XBRLformatted business data can be transferred from machine to machine, XBRL can be used to eliminate manual intervention - the rekeying of data or manipulation via a spreadsheet - with its associated labor costs and possibility for error. Both abilities improve overall internal control. Reducing spreadsheet proliferation. The problem of proliferating spreadsheets has historical momentum; previously paperbased manual systems have been replaced with labor-intensive, information aggregation and analyses tasks conducted via electronic spreadsheets. Such manual efforts have significant process and control risks. Given that some highly publicized restatements may have been caused by spreadsheet proliferation (Willis and Sinnett 2008), auditors should be concerned with spreadsheet-based processes and controls. XBRL data downloaded to a spreadsheet retain information regarding then- content and origin, helping to maintain an audit trail. XBRL can even eliminate spreadsheets: Manual intervention is not necessary because XBRL-tagged data can flow directly between applications, and computers can exchange data directly using a parser.

Enhanced audit trails. In the past, the automation of accounting functions has generally caused the loss of a paper-based audit trail, because electronic accounting systems may not generate any hard copies of source documents to provide evidentiary support for past transactions (Cohen 2008). XBRL-tagged information that is shared between applications retains its context and identity (Exhibit 6), enabling an automated audit trail and enhanced internal control. The automated capture and reporting of audit trail data improve accuracy and enhance the timeliness of audit systems. The benefits of audit trail automation increase significantly as the volume of activity captured by the system increases. Even when the volume of current transactions is not great, automated audit trail systems still provide significant enhancements to monitoring and notification systems, as well as a sound foundation upon which enhanced audit capabilities can be constructed. XBRL Challenges Although the successful implementation of XBRL has tremendous benefits for an organization, there are some challenges that must be overcome. Challenging and complex to learn and use. For now, XBRL is not easy to understand and use. The specifications and data structures in XBRL are complex and require technical training to understand and manipulate. Because XBRL is new, there are few colleges and universities that offer business or accounting courses on XBRL. In addition, the lack of standardization in XBRL software hampers available training. Enhanced general and application controls. Just like any automated accounting information system, XBRL requires enhanced general and application controls. General controls relevant to XBRL include application development, maintenance, and access. Application controls relevant to XBRL include input, eiror coirection, and output. For example, when a particular taxonomy is initially assigned, modified, or added, an auditor should check an instance document against the taxonomy to ensure that the tags are all from lhe appropriate taxonomy. Accounting systems control issues are related to the tagging of accounting data, the integrity of tagged data, and the use of the appropriate taxonomy. Researchers have found that a few critical controls are responsible for the differences between companies with and without highly efficient and effective IT operational processes (Dwayne Meian on, "Security Controls That Work," information Systems Control Journal, vol. 4, no. 1, 2007). One of these critical con Ols is change management, and XBRL can help. If companies adopting XBRL for the storage and reporting of financia] data make changes in the choice of taxonomy or within these taxonomies, it is important to track these modifications for internal control purposes. The versioning report defined by the XBRL Versioning Working Group (www.xbrl.org/workinggroups) maintains and communicates any changes made to the concept definitions when companies adopt a new version of UK DTS used for their mapping process. This functionality allows for automated change management (International Accounting Standards Board, IFRS Taxonomy Guide 1.0, 2008).

Copyright New York State Society of Certified Public Accountants May 2010 Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved Enhanced network security. XBRL can provide live links from financial documents back to the underlying databases. In this case, substantial security risks exist if the security of the operating system, application, and database is inadequately configured. Such configuration errors could allow unauthorized changes or even the destruction of the transactional data supporting the financial statements. When such links are present, an auditor should consider the adequacy of the entity's security policies and procedures for configuring firewalls, hardening operating systems, and other relevant security controls, based upon the nature of the data. Capitalizing on the Benefits XBRL has the potential to yield tremendous benefits for financial reporting and auditing processes. With the SEC actively spurring the adoption of XBRL and IFRS, accountants and auditors should start learning about XBRL now. Readers should note that organizations will get the most benefit from this technology if both XBRL GL and XBRL FR are completely integrated. The main benefit for accountants is improved data flow and data sharing, as well as the automation of many information consolidation and aggregation processes. The main benefits for auditors are improved data flow and data sharing, permitting higher levei analyses with more real-time data. The benefits from an information technology perspective are improved efficiency and effectiveness of data entry and processing. Although these are tremendous benefits, XBRL also presents challenges that must be overcome. Given the potential upside, accountants and auditors will find it worthwhile to start learning more about XBRL and overcome these challenges. Pascal A. Bizarro, PhD, C/SA, and Andy Garcia, PhD, CPA, are assistant professors of accounting in the department of accounting and management information systems at Bowling Green State University, Bowling Green, Ohio. Copyright New York State Society of Certified Public Accountants May 2010 Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa5346/is_201005/ai_n53930788/pg_7/?tag=content;col1

Implementing XBRL Reporting by Sledgianowski, Deb, Fonfeder, Robert, Slavin, Nathan S | Aug 2010

Options and Issues to Consider

In January 2009, the SEC ruled that public companies will now be required to file their financial statements using Extensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL) interactive data to be phased in beginning in 2009, with all U.S. publicly traded companies complying by 2011. As such, high-level accounting personnel and CPAs should consider their options when making decisions and recommendations related to XBRL implementation. Three options for accountants to consider are discussed below, along with eight characteristics of sourcing decisions to consider when developing the implementation plan and deciding whether the project should be outsourced or done in-house. For a primer on how XBRL works, see "How CPAs Can Master XBRL," by Jianing Fang (The CPA Journal, May 2009). XBRL and the SEC Interactive Data Ruling XBRL is a standards-driven, opensource markup r>rogramming language that uses common tags based on a standardized taxonomy to label each individual element of data, which together are stored in an instance document. These instance documents can be read by the many software applications that follow the standards. XBRL has recen y come into the spotlight as an information technology (G?) tool to facilitate the transmission of financial statements that publicly held companies file with the SEC. For example, when electronically filing their 10-K and 10-Q statements using XBRL, a company would code a tag (in this case, "usfr-pte:NetIncome") along with its U.S. Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) net income figure on its income statement This tag signifies that the following data are the amount of the "Net Income" element from their financial statement. The SEC's ruling requiring public companies and mutual funds to file their financial reports using XBRL necessitates that companies contemplate how to implement this requirement The SEC rules, which are being phased in over the next three years, require 2009 financial statements to be filed in XBRL for domestic and foreign accelerated filers that are using U.S. GAAP and have a public float (common equity owned by unaffiliated persons) greater than $5 billion. Those companies with a public float between $700 million and $5 billion are required to file in XBRL by 2010, and all other regulated filers, including smaller reporting companies and aU foreign filers using International Financial Reporting Standards (EFRS), are required to file in XBRL by 2011. First-time filers must include tags for each element amount with this requirement escalating in subsequent year filings to include detailed tagging of amounts, tables, and narrative text within footnotes and related schedules. In addition to mandatory XBRL filings with the SEC, companies are required to publish the XBRL files on their corporate website, if they have one. Besides being in compliance with the SEC mandate for publicly traded companies, there are other benefits for companies using XBRL. XBRL US, the consortium developing XBRL taxonomies and specifications for the United States, suggests that benefits include the automation of manual data entry and validation, which can provide a better quality of information to facilitate more accurate and timely decision making. XBRL could also make it more convenient for financial analysts to compare companies, which could increase their coverage of smaller reporting companies, potentially making these companies more visible to equity markets. Analyst coverage is often viewed as unattainable for public firms with relatively small market values due to the economics of analyst research. Early adopters of XBRL filing who believed there is a benefit to

leveraging an emerging financial reporting technology may have wanted to capitalize on early-mover status. By differentiating themselves from others, these adopters expected to be rewarded for their efforts in increased transparency through an increased share price and market capitalization (Sandra J. Cereola, Gregory A. Jonas, and Ronald J. Cereola, "Evaluating the Benefits of XBRL Adoption: An Empirical Study of the SEC Voluntary Filing Program," Proceedings of the American Accounting Association Annual Conference, 2009). Getting Started The SECs interactive data ruling affects more than 10,000 domestic and foreign issuers that prepare their financial statements under U.S. GAAP or EFRS. In a survey of chief audit executives taken in 2008, one year prior to the SEC mandate, 51% of respondents indicated that they are not at aU familiar with XBRL, 42% indicated they only know the very basics, and almost 90% said that more knowledge and guidance should be provided to the internal audit profession (Institute of Internal Auditors, "Interactive Data - extensible Business Report Language Survey," 2008). A recent survey of leading filing agents, conducted by the XBRL US consortium, found that 340 of the estimated 500 companies required to use XBRL in the first riiase starting June 2009 have converted their financial statements to XBRL. This means there are still thousands of public companies in the process of considering how to implement. The SEC estimates that the direct costs to a company submitting its first interactive data financial statements, with block-text footnotes and schedules, could average $40,510 with an upper bound of $82,220. The costs for subsequent block -text filings could average $13,450 with an upper bound of $21,340. The estimated costs to a company for its first submission with detailed footnotes and schedules could average $30,700 with an upper bound of $ 60,150; subsequent detailed filings could average $21,075 with an upper bound of $37,940. The SEC estimates the number of hours required to tag face financi is averages 125 hours for the first submission and 17 hours for subsequent submissions. But these numbers may decrease as the learning curve falls. Paul Penler, executive director of assurance sendees for Ernst & Young, suggests 30 to 50 hours for the first submission and 200 to 250 hours for initial submissions tagged with detailed footnotes (Alexandra DeFelice, 'Panelists Advise Companies to Take Responsibility for XBRL Tagging - Even When Outsourcing," Journal of Accountancy, November 2009). While these costs and time requirements may be modest for large complex organizations, they may have a larger impact on smaller filers. There is clearly a need for a greater understanding of XBRL implementation options. Victor Choi, Gerry Grant and Andrew Uiz ("Insights from the SECs XBRL Program," The CPA Journal, December 2008) made the following suggestions for companies required to implement XBRL filing: Give careful consideration to whether the project should be outsourced or developed in-house, aUow more time for completion if the project is done in-house, allow ample time for training and learning XBRL processes, expect a steep learning curve, and engage high-level accounting personnel in the decision-making process of how to implement XBRL. Implementation Options

U.S. public companies following SEC regulations need to consider the potential alternatives and whether they only want to meet external reporting compliance requirements or whether they want to extend the use of XBRL to their internal reporting processes. Gianluca GarbeUotto, current chair of the XBRL global ledger (GL) working group, suggests three implementation options organizations should consider: * Tagging financial statements at the end of the reporting process as an extension to the traditional process in order to convert the statements to XBRL format Ox>lt-on), * Integrating XBRL mapping capability within information systems across the firm's value chain as part of the reporting process (built-in), and * Standardizing the internal reporting process by embedding it in enterprise resource planning (ERP) applications and ledgers (embedded) ("How to Make Your Data Interactive," Strategic Finance, March 2009). The bolt-on option is probably the easiest and fastest to implement because it is most similar to what many organizations currently do when they prepare documents in Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) or American Standard Code for Information Interchange (ASCII) format to comply with Electronic Data Gathering, Analysis, and Retrieval system (Edgar) filing requirements. (The Edgar database will eventually be replaced with the SECs Interactive Data Electronic Applications [EDEA] database, which is better structured to store tagged data for easier and faster querying.) The same data used to create the original files are converted into XBRL format using data mapping and instance document creation software applications, such as those listed on the XBRL organization's software tools site (www.xbrl.org/tools/). These software tools often require the manual mapping of data elements to tags that are identified in the standard financial reporting taxonomies using drag-and-drop software features. GarbeUotto suggests there is no benefit to this option other than achieving compliance; he claims that for complicated filings with detailed tagging of amounts, tables, and narrative text within footnotes and related schedules, an automated approach not relying on manual mapping is more desirable. The built-in option, using the XBRL GL taxonomy, enables reporting data to be automatically mapped, on demand, using this standard taxonomy to generate the instance documents. Instead of generating XBRL as an extension to the traditional filing process, the built-in option requires that the business software applications that maintain the source data for financial statements support mapping to the XBRL taxonomies. The embedded option represents the ultimate use of XBRL, going beyond SEC compliance for external reporting. With this option, a company embeds XBRL into its corporate performance management and business analytic information systems so that it can leverage this standardized integrated data to provide information that increases the value of the business (Michael Smith, French Caldwell, and Mary Knox, "XBRL Mandate on Financial Reporting Will Improve Transparency," Gartner Research Report, December 19, 2008). Business analytics entails the use of analytical software algorithms on large amounts of data in order to identify patterns in the

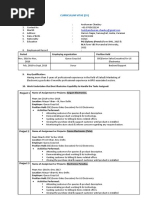

data that are useful in making explanatory and predictive models to facilitate an organization's decision-making. The implementation of each of the three options - bolt-on, built-in, and embedded - can either be outsourced to a thirdparty vendor or carried out in-house by the filer, but each option may require the company to include new custom tags as extensions to the standard XBRL tag set to capture all of the information on their SEC filing. Research shows that there is a good match between the standard tag set and filers' reporting requirements, but significant differences exist across industries (Matthew Bovee, Michael L. Ettredge, Rajendra P. Srivastava, Miklos A. Vasarhelyi, "Does the Year 2000 XBRL Taxonomy Accommodate Current Business Financial-Reporting Practice?" Journal of Information Systems, Fall 2002, vol. 16, no. 2). Joel Levine, assistant director at the office of interactive disclosure for the SEC, suggests that if a standard tag name doesn't match a filing company's element name, the filing company should re-label the tag to reflect the name it uses, and it should only create an extension if a tag does not exist in the standard taxonomy with an appropriate definition of the filing company's element. XBRL Sourcing Considerations The following eight characteristics (see the Exhibit) should be considered when developing an XBRL implementation plan and deciding whether to handle the project in-house or outsource it. These are adapted from the model of characteristics of client-vendor outsourcing relationships found in "SME ERP System Sourcing Strategies: A Case Study," by Deb Sledgianowskl Mohammed Tafti, and Jim Kierstead (Industrial Management and Data Systems, 2008). Client-vendor relationship. Companies should consider whether they have an existing relationship with a service provider who can also provide XBRL conversion services. Currently, there are no licensing or certification requirements for XBRL filing service providers. Public accounting firms, filing agencies, financial printers, and providers of financial statement conversons to HTML may provide XBRL conversion services in addition to their traditional services. It may be more beneficial to continue an established relationship than to develop a new one. Filers need to be aware that interactive data are subject to the same liability under federal securities laws as a corresponding traditional filing, and as such they are responsible for the content even if they do not directly create the XBRL documents. The SEC's Rule 406T provides for a temporary grace period from compliance failure until October 31, 2014, as long as good faith attempts were made to comply. XBRL filings are excluded from officer certification requirements of the Exchange Act Rules and are not required to obtain auditor assurance. Companies can, however, obtain third-party assurance under the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) Interim Attestation Standards, AT Section 101. The SEC plans to monitor corporate implementations of the interactive data ruling and adjust the officer certification exclusion if necessary.

Company size. Companies should consider their size relative to the size of the outsourcing vendor. Many companies, especially small to medium-sized companies, tend to engage services from similarly sized providers. Smaller companies may prefer to work with vendors similar in size because they may perceive that they receive better service from them than from larger vendors, who may give preference to more lucrative customers. When using vendors of similar size, the ability to monitor the vendor's performance and reduce the risk of noncompliance is enhanced (Wonseok Oh, Michael Gallivan, and Joung Kim, 'The Market's Perception of the Transactional Risks of Information Technology Outsourcing Announcements," Journal of Management Information Systems, 2006, vol. 22, no. 4). Outsourcing contract. Best practices for outsourcing suggest the use of a formal, detailed, and comprehensive contract The implementation costs of a bolt-on approach may be low enough to fall under a firm's multiple bid policy; therefore, the company may select its existing filing agent or other established service provider without seeking competitive bids and without utilizing a contract Because XBRL filing is a new endeavor, typical implementation costs have yet to be fully established and are more frequently best-guess estimates. Not having a contract could be problematic if costs were underestimated. Having a high level of trust in a vendor, established by a preexisting client-vendor relationship, can reduce the transaction costs inherent in a relationship between two parties. In new client-vendor relationships, where a high level of trust has not yet been established, additional resources may be needed to manage the unknown risk that the other party will not comply with the agreement. Intellectual property. According to transaction-cost theory, the collaboration between an entity and its outsourcing partner creates an asset whose ownership must be agreed upon by both sides (Benoit Aubert, Suzanne Rivard, and Michel Patry, "A Transaction Cost Model of IT Outsourcing," Information & Management, vol. 41, no. 7). Ownership of both the data and the process to derive the data may seem inconsequential to the bolt-on implementation option because the resulting interactive data are derived from the same publicly available data used to fulfill traditional Edgar filing requirements and the software tools used for this implementation option are commercially available to all filers. But ownership rights may be more consequential in the built-in and embedded options because the data and processes are integrated with the internal reporting data and processes, which may be integral to the company's competitive advantage. Businesses considering outsourcing the built-in and embedded options of XBRL implementation should consider having explicit nondisclosure and ownership agreements with their service provider and may prefer to use a service provider offering an independent Statement on Auditing Standards 70 (SAS 70) audit report or another form of assurance as to their internal controls for safeguarding data and other content. Communication. Effective communication skills across internal functional areas and with external vendors are important for the successful implementation of interactive data filing. Proper documentation of the tagging process and the rationale behind mapping decisions are tools that can be archived and accessed during future filings. The ability for a mutual "meeting of the minds" resulting from unambiguous communication leaves less room for misinterpretation of expectations and requirements. Although CPAs, auditors, and other accounting personnel need not know the details of programming XBRL, as project leaders they should be familiar with YT

terminology. Likewise, the IT professionals working on the implementation should be familiar with accounting and finance terminology and concepts. Research has shown that clear communication of objectives and information exchange can lead to a higher level of team commitment and performance (Ting-Peng Liang, Chih-Chung Liu, Tse-Min Lin, and Binshan Lin, 'Tiffect of Team Diversity on Software Project Performance," Industrial Management & Data Systems, vol. 107, no. 5, 2007). A recent article reporting on the 2009 XBRL US Conference indicated that some panelists observed a "disconnect ' between management and the project team responsible for preparing the XBRL filing, which they inferred could lead to a last-minute, rushed review of the information as the filing deadline approached (Alexandra DeFelice, "Panelists Advise Companies to Take Responsibility for XBRL Tagging - Even When Outsourcing," Journal of Accountancy, November 2009). A mutual understanding of processes and terminology, and documenting this understanding, can facilitate a successful implementation. Custom functionality. A common practice when deciding whether to develop an IT solution in-house, purchase a commercially available solution, or outsource is to determine whether a commercially available solution is readily available or whether a custom solution is required. Assets highly specific to an organization are less available in the marketplace and therefore more expensive (Lei-da Chen and Khalid Soliman, "Managing IT Outsourcing: A Value-Driven Approach to Outsourcing Using Application Service Providers," Logistics Information Management, vol. 15, no. 3, Fall 2002). If a process is not seen as a core competency, which in many cases financial reporting isn't then it makes more sense to outsource its implementation; as further confirmation, the majority of XBRL filers so far have utilized a third-party service provider for their interactive data implementation. If a business can easily use one of the existing XBRL software packages to solve its business requirements, then it can be a much faster and le ss expensive solution than developing a solution in-house or outsourcing. But if an organization's business requirements require custom functionality to provide a unique capability - for example, if it wants to leverage advantages of XBRL reporting throughout the financial information system value chain to collect unique data for predictive business analytics - then a solution implemented in-house may be necessary. Most major enterprise software providers, such as Microsoft, SAP, and Oracle, have announced XBRL support in their core products to facilitate data integration and financial reporting. Many companies are already using software applications from these vendors. This could lead to a natural progression of a phased-in implementation plan that starts with a bolton solution to meet impending compliance needs, but eventually evolves so that XBRL is integrated into internal accounting information systems. Task complexity. One of the main determinants of a sourcing strategy for an IT implementation is the degree of task complexity. Less complex applications with a highly structured development process are more likely to be successfully outsourced (Rajesh Mirani, 'Client-Vendor Relationships in Offshore Applications Development: An Evolutionary Framework," Information Resources Management Journal, vol. 19, no. 4, 2006). Early adopters participating in the SECs Voluntary Filers Program found that the project managers for the XBRL implementation were primarily middle- to upperlevel accounting managers, not technical managers (Choi, Grant, and Uiz 2008). If managers perceive the implementation to be a complex task, then they may be more comfortable outsourcing the process. Early adopters have found that the learning curve

quickly diminishes after the initial filing. Initially, the reporting task may be seen as complex, but then becomes more structured and less complex after the process is developed and implemented. Organizations may want to initially outsource XBRL filing and then, as they become more comfortable with the process, consider implementing it in-house. Vendor's skills. Organizations should consider the level of experience a vendor has with XBRL filing and its understanding of different XBRL standards. If extensions to standard tagging are needed, does the vendor have this experience? One of the main reasons for outsourcing is to take advantage of the vendor's technical skills (Aubert, Rivard, and Patry 2004). If the sendee provider does not fully understand XBRL as it relates to an organization's specific business, then its needs may not be properly met. Both www.sec.gov and www.xbrl.org include lists of companies that provide XBRL services. Many service providers are members of the XBRL US consortium. Capitalizing on XBRL The requirement for U.S. public companies to file their financial reports in XBRL is being phased in over the next few years. As with any other information technology, companies implementing XBRL need to consider both internal business needs, such as using financial data for added business value, and environmental factors, such as evolving taxonomy standards, and consider how these may manifest over time. With the compliance deadlines rapidly approaching, there may be a shortage of skilled XBRL experts. Companies should hire consultants if they do not have qualified in-house personnel for XBRL deployment and consider outsourcing to solution providers who, along with providing transaction and compliance services, are now offering XBRL filing services. Companies should consider moving beyond a bolt-on approach to take full advantage of XBRL technology. Copyright New York State Society of Certified Public Accountants Aug 2010 Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved XBRL has the potential to have a farreaching impact on public and private businesses, regulators, banking and investment institutions, accounting firms, and software vendors. Now is the time to develop an XBRL implementation plan. Organizations should consider their sourcing needs and, if outsourcing, should consider the clientvendor relationship, company size, the outsourcing contract, intellectual property assurances, communication, custom functionality, task complexity, and vendor skills. Deb Sledgianowski, PhD, PMP, is an assistant professor, Robert Fonfeder, PhD, CPA, CMA, is a professor, and Nathan S. Slavin, PhD, CPA, is a professor and chair of the department of accounting, taxation and legal studies in business; all at the Frank G. Zarb School of Business, Hofstra University, Hempstead, NY. This research was sponsored by a Summer Research Grant from the Frank G Zarb School of Business. Copyright New York State Society of Certified Public Accountants Aug 2010 Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved

http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa5346/is_201008/ai_n55485350/pg_7/?tag=content;col1 XBRL: Not Just for Public Companies by Quinlan, Patrick | Jun 2010 Nearly a decade ago, experts said that Extensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL) would revolutionize financial reporting and bring visibility, consistency, and transparency to often confusing financial statements. But the recent financial crisis and resulting recession, along with a wave of high-profile debacles that eluded the attention of the SEC and other regulators (such as the Bernard Madoff fraud), took precedence over computing and coding. During the summer of 2009, however, the efforts of former SEC Chairman Christopher Cox to transform the way financial analysts, regulators, journalists, and others read, parse, and analyze data were realized. An SEC-mandated threeyear phase-in for public companies to file their financial statements using interactive data began. The first wave of companies, beginning with the Fortune 500, started filing their financial statements in XBRL. Under the regulations of the SarbanesOxley Act, CEOs and CFOs of public companies in the United States are now criminally liable for the accuracy of their financial information. According to a survey conducted by the AICPA and XBRL US in September 2009, 73% of public companies reported they have already begun preparations for the adoption of XBRL. The main driver for preparedness today is compliance, but public companies aren't the only ones that should be paying attention. Regulators around the globe are using the standard for both private and public companies. Perhaps even more compelling is the argument that XBRL offers cost savings, increased efficiency, reporting accuracy, and reliability. XBRL is ushering in an era of financial transformation that has the potential to change the way businesses are managed. Ultimately, the interactive data that XBRL provides will be used in the internal financial systems of a company - public or private - to improve the accuracy, interoperability, and speed of reporting and internal analysis. XBRL, at its core, simplifies and streamlines the financial information supply chain that includes public and private companies, accountants, data aggregators, members of the investment community, and, essentially, consumers of financial information. As soon as a significant bulk of corporate financial and operational information is available in XBRL format and accessible via the web, new ways of business management will begin to emerge. This will happen primarily in the areas of corporate performance benchmarking, activity alerting, and the visualization of first national - and then global - business trends. Using XBRL opens a new financial ecosystem that allows accounting data to be tagged and easily retrievable across multiple documents. XBRL can be thought of the same way as a barcode on a can of soup at the grocery store. When that can is scanned, all types of information appears when the can was received from the warehouse, the price being charged to consumers, the

expiration date of the item in the can. When looking at a corporation's financial statement, XBRL will reveal a variety of details, such as the type of document, when the document was created, its author, the reporting period, and the company name and size. The purpose of XBRL is not just to increase financial transparency, but to transform the way a business operates. This means that not just more information is available to the public, but that the available information is clearer and more accessible, making it easier to compare financial information across companies. This assists both investors and corporations in making better decisions and, in turn, helps companies be more accountable in their business practices. XBRL provides the foundation for a new generation of financially oriented web services that will make it easier for analysts to identify the best-performing stocks, for executives to monitor competitors, and for regulators to identify potential problems in a company's financial data As XBRL edges ever closer to the tipping point of a relatively homogeneous corporate financial data ecosystem, it becomes even more important to balance current "compliance" thinking with future "control" and "communication" thinking. Private companies should consider adopting XBRL even if they are not required to comply with the SECs mandate. Companies that lead the integration of XBRL into their systems will reap the rewards. ? Patrick Quinlan, MBA, is CEO of Rivet Software, based in Denver, Colo. Copyright New York State Society of Certified Public Accountants Jun 2010 Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa5346/is_201006/ai_n54717694//

Regulatory mandates for XBRL expand globally by Brad Monterio | Dec, 2010 XBRL International, Inc. (XII), the global standardsetting body of the XBRL business reporting standard, held its most recent international conference October 19-21, 2010, in Beijing, China, Several IMA[R] XBRL Committee members attended, as well as more than 700 delegates that included11 vice ministers from various Chinese government agencies, senior executives, accountants, attorneys, technology vendors, analysts, bankers, and consultants. IMA is a founder of the XBRL standard and a member of XII. [ILLUSTRATION OMITTED] The International Steering Committee (ISC), XII's governing body, elected new leaders during the conference. Arleen Thomas, senior vice president of the AICPA, was elected chair, and David van den Ende, director with Deloitte Netherlands, was elected vice chair. Both serve on the XII board of directors as well. Five at-large members also were elected: Li Dan, China Ministry of Finance; John Turner, CoreFiling; Caetano Nobre, MZ Consult S.A.; Shiping Liu, Global Business Intelligence

Consulting Corporation (GBICC); and Avinash Chander, Institute of Chartered Accountants of India (ICAI). In addition, several significant announcements were made during the event, including expanded regulatory mandates for the use of XBRL and a new technical working group designed to stimulate development of more software applications around the world. This working group is the first outcome of XII's recently published Preserve. Promote. Participate. Moving XBRL Forward, a core vision document that outlines six strategic initiatives to continue the momentum of the XBRL standard. CHINA: The China Ministry of Finance released its General Purpose XBRL Taxonomy that requires the use of XBRL across several Chinese Ministries, including those responsible for taxation, audit, securities, banking, insurance, information technology, and others. This represents the largest implementation of the XBRL standard in the world to date. Companies of all types, including listed and privately held, banks, insurance providers, mutual fund companies, and more, will be required to file tax and financial information to the appropriate oversight bodies. In 2005, China became the first country to mandate XBRL for listed companies on both the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges. It also already has a requirement for mutual funds to file reports to the securities regulator. IRELAND: Revenue Commissioners Ireland has announced that, as part of mandatory e-filing of tax information, it's at the preliminary stages of building an XBRL-enabled filing platform that private and listed companies will use to file their taxes. The U.K., Germany, Denmark, China, and others are now using XBRL for tax reporting requirements for a few million private and listed companies. Add this to the millions of companies using XBRL to file annual accounts across Europe, as well as listed companies in the U.S., Japan, and China, and XBRL is now used to report information from companies representing more than 75% of the world's market capitalization. Working with XBRL for more than 11 years, I'm excited to see the explosive growth in its use around the world. IMA members, whether at privately held or publicly listed companies, will be impacted by XBRL. Whether they use it for external reporting to tax authorities, banking institutions, or securities commissioners, or for internal performance measurement and decision making, they will probably be using it soon, even if they don't realize it. Software tools will include built-in XBRL capabilities that members won't necessarily realize are there. Along those lines, XII also announced the formation of a technical working group of software vendors from around the world that will come together in January 2011 to design an abstract model for XBRL software development. This is a strategic initiative to catalyze development of more XBRL-enabled software solutions by lowering product development hurdles for software vendors and providing software engineers with a consistent blueprint to develop their own XBRL-enabled tools. This will widen IMA members' choices as they seek easy-to-use tools for their own analysis and/or creation of XBRL-tagged data for decision making, performance measurement, business intelligence, and reporting.

Participants in the abstract modeling group span a wide cross section of the software vendor community, including the largest global enterprise resource planning (ERP) vendors, as well as specialty solution providers, accounting firms, and regulatory bodies. Without a standard XBRL abstract model, software architects, engineers, and developers must create their own proprietary models--a costly process that's prone to interoperability issues because other vendors may not formulate models that are in complete agreement. A standard abstract model leads to a more unified understanding of the XBRL technical specification and can potentially lower development costs and remove barriers to entry for software vendors--another good thing for IMA members. COPYRIGHT 2010 Institute of Management Accountants COPYRIGHT 2010 Gale, Cengage Learning It's difficult to realize the benefits of XBRL to your company if you don't have the proper analytical tools to use all the data that's being enabled through the standard. XII's abstract modeling group will stimulate the development of a broader set of tools that IMA members can use from the vendors they prefer. Business intelligence tools are increasingly in demand by many companies today, so this XII effort will lay the foundation for these types of solutions to be created more easily. http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb6421/is_6_92/ai_n56532655/pg_2/?tag=content;col1

The buzz about XBRL and interactive data by Kristine Brands | Oct, 2010 | The combination of XBRL (eXtensible Business Reporting Language) and interactive data is gaining momentum to meet many business reporting needs. And the buzz about XBRL is growing. The technology has gone beyond the drawing board and is becoming more accessible, is easier to use, and is a tool that you'll want to learn more about to meet your business reporting and analysis needs. It's no longer used just to meet the external Securities & Exchange Commission (SEC) reporting requirement--now it has broad application for internal data also. XBRL is the ticket out of "spreadsheet hell." You won't need to worry about rekeying Excel data from spreadsheet to spreadsheet and risking errors because you can design applications that pull your data from a secure and validated source.

The good news is that you don't have to be a programmer to understand XBRL and to learn what it can do for you. More good news is that there are many free and low-cost resources available to help you learn about this exciting tool. Let's take a look at some of the quick and easy resources that you can use to learn more about XBRL. A good place to begin understanding XBRL and how it affects your organization is to read XBRL for Dummies by Charles Hoffman and Liv Watson. One of the initial proponents of XBRL, Liv is a

former IMA(r) Board of Directors member and has been a driving force behind the development and adoption of XBRL worldwide. Charles Hoffman is the "father of XBRL." Written in plain English and nontechnical terms, their book is a great resource to help you learn basic XBRL concepts and find out about current applications that you can use in your organization today. IMA's XBRL Advisory Committee, founded in August 2009, created an XBRL Resources Group that you can access through LinkUp IMA (www.link upima.com). Choose Groups, then Subject Matter Groups, then click on the XBRL Resources Group. There you'll find XBRL information, including XBRL basics, case studies about internal company applications, articles, podcasts, demos, and an online discussion forum. Check this site often because it's constantly updated. IMA's popular free webinar series has presented several programs about XBRL. You can view the archives of these programs under Programs & Events at the IMA website (www.imanet.org). Additional programs about XBRL will be offered next year covering XBRL business applications; how to use XBRL for data analysis; demos of easy-to-use tagging and data analysis software; and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), which addresses sustainability reporting and XBRL. When you attend IMA's live webinars, you can earn IMA--and NASBAapproved CPE. IMA's 92nd Annual Conference & Exposition in Orlando, Fla., next June will include XBRL and interactive data sessions. Check the Conference program for details when it's released in early 2011, and visit www.imaconference.org for Conference updates and information. If you work for a publicly traded U.S. company, you'll be required to submit your financial reports using XBRL. The mandate is being phased in over three years, and it started with the largest companies in June 2009. The SEC's Office of Interactive Disclosure provides resources about the filing requirements. Also, XBRL US offers several free training sessions, including how to implement XBRL for SEC reporting and how to avoid common mistakes when you prepare your XBRL financial reports. Even if you don't face the SEC mandate, these webinars, presented by experts from XBRL US, give a clear overview of an XBRL data implementation and can help you understand the concepts and the process. You can attend these webinars live or watch the archives. XBRL International's website is being relaunched at its conference in Beijing this month. The site will contain many resources, including discussion forums, vendor directories, case studies, articles, event calendars, blogs, and much more. It will be a useful resource for XBRL users around the world. IMA is interested in your ideas about the type of training that you need. If you have some suggestions that you would like to share, please send me an e-mail at kmbrands@yahoo.com. Kristine Brands, CMA, CPA, is an assistant professor at Regis University in Colorado Springs, Colo., and is a member of IMA's XBRL Advisory Committee and IMA's Pikes Peak Chapter. You can reach her at kmbrands@yahoo.com. A Few Resources

XBRL for Dummies by Charles Hoffman and Liv Watson, Wiley, New York, N.Y., 2009. SEC Office of Interactive Disclosure www.sec.gov/spotlight/xbrl.shtml XBRL US www.xbrl.us/Pages/default.aspx XBRL for Filers: Implementing XBRL for SEC Reporting (webinar) www.xbrl.us/events/Pages/current.aspx Avoid Common Errors, Establish Proper Controls (webinar) www.xbrl.us/events/Pages/commonerrors.aspx IMA Resources www.imanet.org IMA LinkUp IMA XBRL Resources Group (http://linkupima.com/groups/7eab42efae/summary) IMA Programs & Events Webinars and Webinar Archives (www.imanet.org/programs_events/webinars.aspx) By Kristine Brands, CMA, CPA COPYRIGHT 2010 Institute of Management Accountants COPYRIGHT 2010 Gale, Cengage Learning http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_hb6421/is_4_92/ai_n56479353//

Using XBRL to Analyze Financial Statements by Tribunella, Thomas, Tribunella, Heidi | Mar 2010 A Step-by-Step Spreadsheet Guide

Accounting and financial data has long been contained in paper documents, but it is now possible to identify, transfer, and store financial information electronically. XML (Extensible Markup Language) and XBRL (Extensible Business Reporting Language) can give us the ability to tag specific pieces (elements) of financial information so they can be used and reused in a variety of reports. XBRL is a text and data markup language similar to HTML (Hyper Text Markup Language), created in the metalanguage of XML. XBRL allows content such as financial statement elements to be electronically labeled with conceptual tags. The discussion below will demonstrate how to use XBRL data with a spreadsheet for financial analysis. It will show how XBRL data can be easily updated in the spreadsheet as new financial data becomes available. Both Microsoft Office versions 2003 and 2007 are XML compliant as are most databases, accounting systems, and enterprise systems. This means that these systems can automatically tag and export data and information in XML format. Accordingly, this information can be imported into another application, such as a spreadsheet, for analysis. In addition. XML-compliant documents can be posted directly to the Internet for display, as most web browsers can read XML documents. Step 1: Prepare the Spreadsheet The steps outlined below use Microsoft Excel 2007. Before starting the procedures outlined in this article, make sure that you have the developer tab displayed. If it is not displayed, simply click on the Microsoft Office Button in the top left corner and then choose "Excel Options" from the drop down menu. In the dialog box, under "Top options for working with Excel," check the third box, "Show Developer tab in the Ribbon," and then click "OK." Step 2 Identify the Company and Report This example uses the financial statements from Adobe Systems Inc., specifically its Form 10-Q for the quarter ended August 29, 2008. To download the financial statements as a PDF for use as a reference while developing the sample spreadsheet, go to www.sec.gov. Click on "Search" in the upper right comer. In the "Search Company Filings" pane on the left, enter Adobe into the "Company name" field and click on "Find Companies." As the example uses Adobe Systems Inc., click on CTK number 0000796343 to see the filings. Scroll down to the 10-Q filing dated 2008-10-02 and click on the "Documents" button. From the resulting list, click on the file "formlOqunofficiaL pdf.pdf." Pages 1 to 5 of the 10-Q of the PDF can be used as a reference. Step 3: Download the XBRL Report

To download the XBRL-compliant report from the SEC for 10-Q, follow the steps above. Then, look down the list of documents, below the PDF, and right-click the XBRL Instance Document file named "adbe-20080916.xml." Choose "Save Target As . . ." and save the file to the desktop or other desired location. Refer to Exhibit 1. Step 4: Open the XML Source within an Excel Spreadsheet The next step is to integrate the tagged data source into the spreadsheet. To access the tagged data, complete the following procedures: * From within Microsoft Excel, open the XML file downloaded in step 3. * Excel will recognize the file as an XML file, and an 'Open XML" dialog box will appear. Select "Use the XML Source task pane" and click "OK." A dialog box that states: 'The specified XML source does not refer to a schema. Excel will create a schema based on the XML source data" will then appear. The user should click "OK." The tagged data will be shown in a sidebar of the Excel spreadsheet. Excel has created a taxonomy of tags from the structured XML-compliant document. Step 5: Determine the Output Information and Identify the Input Data With the data in hand, a user can determine whatever information is needed, such as financial ratios, horizontal analysis, and vertical analysis. Four ratios will suffice to demonstrate the process. Exhibit 2 shows the input data and the related XBRL tags and cell locations. After the data needs are determined, a user can work on importing the input data to produce the output information. Input data should only be entered once. Step 6: Map the XBRL Tags into the Input Section Once all of the XBRL tags are shown in the source task pane, it is a simple process to map the data elements to the cells in the input data section of the spreadsheet. Two methods can be used to map the data: 1) click on the data element and drag it to the target cell or 2) select the target cell on the spreadsheet and double-click on the data item shown in the source task pane. Data elements can only be mapped to one cell; the same element cannot be mapped to two different cells. If the data is needed in more than one cell, simply add a formula (e.g., A2) to put the data in a second cell. It may be helpful to show the actual numerical data in the XML Source task pane while mapping. To do so, simply click the "Options" menu on the bottom of the XML Source task pane and select "Preview Data in Source Pane." Once mapped, the cell has a blue background, and in die source task pane, the data element is bolded to indicate it has already been mapped. When bringing the tags into the spreadsheet, the name of me tag is automatically placed above the data. To remove the tag names and use custom names, simply uncheck the "Header Row" box within the 'Table Style Options" on the Design Tab.

The input data required to calculate the desired output information in this example are: current assets, current liabilities, cash, short-term investments, accounts receivable, net income, sales, and gross profit. The following steps will include this data in the input section and program the cells in the output section to calculate the desired ratios: current ratio, quick ratio, profit margin, and gross profit margin. The data will appear in the spreadsheet cells once the import function is complete. When the data is imported, the financial statements are comparative, so the data will take up two rows for the balance sheet: one for the current year, listed first, and one for the prior year. The data will take up four rows on the income statement, as four columns appear on the Adobe income statement. Refer to Exhibit 3 for a view of the completed spreadsheet prior to importing the XML data. Step 7: Populate the Spreadsheet by Importing the Data Once the spreadsheet is mapped and labeled, it is time to import the data. The authors have found that it is easier to enter the formulas for the output section after the data has been imported. To do so, simply place me cursor in any cell. Click on the "Developer Tab" and then click "Import." An XML Import dialog box will appear. Select the file with the XML data in it and click "Import." The data will be pulled into the spreadsheet cells. See Exhibit 4 for a Screenshot of an Excel spreadsheet with the imported XMLcompliant data. One can now format the data with commas and decimals, as well as place lines and borders as appropriate. Compare the data imported to the printout of the 10-Q to note that the imported data is comparative financial information. Step 8: Create the Formulas At this point, the cell formulas can be entered into the output section of the spreadsheet. The Excel formulas and their related addresses are shown in Exhibit 5. The spreadsheet is organized with input and output sections so that changes in the input data have no effect on the output information. As a result, the data can be updated quickly without re-creating the cell formulas. Exhibit 6 presents the completed spreadsheet, which includes the formatted data as well as formulas for the financial statement analysis. Step 9: Change the Input Section The real power of this technique comes from the ability to update the spreadsheet with additional data. To show this, download the next quarter's 10-Q for Adobe Systems, the quarter ending February 28, 2009. It is under the filing date 2009-04-03 and has the file name of adbe-20090227.xml (see Step 2). Follow the instructions to import the data (Step 7). The data from this file can now be incorporated into the spreadsheet, and the financial statement ratios are automatically recalculated. Possibilities of Electronic Data

SEC Chair Mary Schapiro recently announced that the EDGAR (Electronic Data Gathering and Retrieval) system will be replaced by a new system. EDGAR was developed in the 1980s to store public company filings, such as 10-Ks and 10-Qs. The EDGAR system is a textbased document system, which makes it difficult to retrieve individual pieces of data from the stored financial information. The SECs new IDEA (Interactive Data Electronic Applications) system will be data-based, allowing users to search and retrieve data items, such as revenue or retained earnings. The new IDEA system will place electronic XBRL tags around data items so that they can be efficiently searched and retrieved for financial analysis. Because XBRL and XML are open source systems, they are free of license fees. In addition, XBRL is extensible so companies can modify the basic taxonomy (with XML) to fit their needs. Copyright New York State Society of Certified Public Accountants Mar 2010 Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved The uses of such technologies are numerous. Auditors can use these skills to quickly look at benchmarking data and use during analytical procedures within an engagement. This can also be helpful when analyzing companies as potential investment and acquisition targets. The advantages of XBRL are manifold. For example, automatic tagging of data and information is now available with accounting software, database, and enterprise systems. With XBRL, analysts can drill down to the transaction level from the financial reports. Another advantage is quicker and more periodic reporting capabilities, as well as real-time reporting and auditing.

With the recent SEC mandate for the 500 largest publicly held companies to use XBRL, the data is there. Accordingly, CPAs must learn how to work with, and profit from, this new form of information. Thomas Tribunella, PhD, CPA, is an associate professor of accounting and information systems in the school of business, State University of New York at Oswego, Oswego, N.Y. Heidi Tribunella, MS, CPA, is a senior lecturer in accounting at the Simon Graduate School of Business Administration, University of Rochester, Rochester, N.Y. Copyright New York State Society of Certified Public Accountants Mar 2010 Provided by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights Reserved http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa5346/is_201003/ai_n53082109/pg_3/?tag=content;col1 XBRL implementation strategies: the deeply embedded approach by Gianluca Garbellotto | Nov, 2009 In the final column of the XBRL Implementation Strategies series, I will discuss in detail the "deeply embedded" approach, the third approach to XBRL implementation introduced in the March 2009 column, "How to Make Your Data Interactive."