Nakpil Vs Valdes

Nakpil Vs Valdes

Uploaded by

Patricia Anne RamelCopyright:

Available Formats

Nakpil Vs Valdes

Nakpil Vs Valdes

Uploaded by

Patricia Anne RamelOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Nakpil Vs Valdes

Nakpil Vs Valdes

Uploaded by

Patricia Anne RamelCopyright:

Available Formats

Nakpil vs. Valdez, 288 SCRA 75 (A.C. No.

2040 March 4, 1998)

FACTS:

In 1965, Jose Nakpil became interested in purchasing a summer residence in Moran Street, Baguio City. For

lack of funds, he requested respondent, Carlos Valdes to purchase the Moran property for him. They agreed that

respondent would keep the property in trust for the Nakpils until the latter could buy it back. Pursuant to their

agreement, respondent obtained two (2) loans from a bank (in the amounts of P65,000.00 and P75,000.00) which he

used to purchase and renovate the property. Title was then issued in respondent's name.

When Jose Nakpil died on 1973, respondent acted as the legal counsel and accountant of his widow,

complainant IMELDA NAKPIL. The ownership of the Moran property became an issue in the intestate proceedings. It

appears that respondent excluded the Moran property from the inventory of Jose's estate. On 1978, respondent

transferred his title to the Moran property to his company, the Caval Realty Corporation.

During the pendency of the action for reconveyance, complainant filed administrative case to disbar the

respondent for excluding the Moran property in the estate's inventory and transferring it to his corporation, for charging

the loan secured to purchase the said excluded property as a liability of the estate, and for representing conflicting

interests when his accounting firm prepared the list of claims of creditors Angel Nakpil and ENORN, Inc. against her

husband's estate which was represent ed by respondent's law firm.

ISSUES:

Whether or not respondent is guilty of misconduct

RULING:

Yes. It ought to follow that respondent's act of excluding the Moran property from the estate which his law firm

was representing shows a lack of fidelity to the cause of his client. If respondent truly believed that the said property

belonged to him, he should have at least informed complainant of his adverse claim. If they could not agree on its

ownership, respondent should have formally presented his claim in the intestate proceedings instead of transferring

the property to his own corporation and concealing it from complainant and the judge in the estate proceedings.

Respondent's misuse of his legal expertise to deprive his client of the Moran property is clearly unethical.

Second, respondent seeks to exculpate himself from this charge by disclaiming knowledge or privity in the

preparation of the list of the estate's liabilities. He theorizes that the inclusion of the loans must have been a mere

error or oversight of his accounting firm. It is clear that the information as to how these two loans should be treated

could have only come from respondent himself as the said loans were in his name. Hence, the supposed error of the

accounting firm in charging respondent's loans against the estate could not have been committed without

respondent's participation. Respondent wanted to "have his cake and eat it too" and subordinated the interest of his

client to his own pecuniary gain. Respondent violated Canon 17 of the Code of Professional Responsibility which

provides that a lawyer owes fidelity to his client's cause and enjoins him to be mindful of the trust and confidence

reposed on him.

As regards the third charge, we hold that respondent is guilty of representing conflicting interests. It is

generally the rule, based on sound public policy, that an attorney cannot represent adverse interests. In the case at

bar, there is no question that the interests of the estate and that of its creditors are adverse to each other.

Respondent's accounting firm prepared the list of assets and liabilities of the estate and, at the same time, computed

the claims of two creditors of the estate. There is clearly a conflict between the interest of the estate which stands as

the debtor, and that of the two claimants who are creditors of the estate.

However, Canon 15, Rule 15.3 explains that representation of conflicting interests may be allowed where the

parties consent to the representation, after full disclosure of facts. The lawyer must explain to his clients the nature

and extent of the conflict and the possible adverse effect must be thoroughly understood by his clients. The fact,

however, that complainant that did not object to the set-up cannot be taken against her as there is nothing in the

records to show that respondent or his law firm explained the legal situation and its consequences to complainant.

Prescinding from these premises, respondent undoubtedly placed his law firm in a position where his loyalty

to his client could be doubted. Thus, violating Canon 15.

Members of the Bar are expected to always live up to the standards embodied in the Code of Professional

Responsibility as the relationship between an attorney and his client is highly fiduciary in nature and demands utmost

fidelity and good faith.

IN VIEW WHEREOF, the Court finds respondent ATTY. CARLOS J. VALDES guilty of misconduct. He is

suspended from the practice of law for a period of one (1) year effective from receipt of this Decision, with a warning

that a similar infraction shall be dealt with more severely in the future.

You might also like

- Sample Opposition To Heggstad Petition For CaliforniaDocument3 pagesSample Opposition To Heggstad Petition For CaliforniaStan Burman100% (1)

- Declaration of TrustDocument2 pagesDeclaration of TrustKara Marcelo100% (2)

- Tex Lee Mason Trust 15 May 2015Document12 pagesTex Lee Mason Trust 15 May 2015Thomas Odzilone100% (11)

- UCC Lien Perfection and Priority Scott HelbingDocument35 pagesUCC Lien Perfection and Priority Scott Helbingtrustkonan100% (23)

- Juan G. Frivaldo, V. Commission On Elections, and Raul R. Lee G.R. No. 120295 - June 28, 1996Document4 pagesJuan G. Frivaldo, V. Commission On Elections, and Raul R. Lee G.R. No. 120295 - June 28, 1996Kyle BanceNo ratings yet

- 0001 When You Are BornDocument3 pages0001 When You Are Bornrhouse_1100% (3)

- Ethics CasesDocument6 pagesEthics CasesdianedeeNo ratings yet

- Arde Vs Atty. de SilvaDocument7 pagesArde Vs Atty. de SilvaFacio BoniNo ratings yet

- People Vs MamarilDocument2 pagesPeople Vs MamarilLloyd David P. VicedoNo ratings yet

- Pantaleon v. AmEx Co - Case DigestDocument2 pagesPantaleon v. AmEx Co - Case DigestJohamil AzisNo ratings yet

- Hernandez VS AlbanoDocument7 pagesHernandez VS AlbanoAgatha GranadoNo ratings yet

- Abragan Vs RodriguezDocument6 pagesAbragan Vs RodriguezHomer Simpson100% (1)

- Mariveles Vs MallariDocument3 pagesMariveles Vs MallariNelia Mae S. VillenaNo ratings yet

- Diaz v. Mandagan, A.C. No. 12669, June 28, 2021Document2 pagesDiaz v. Mandagan, A.C. No. 12669, June 28, 2021Sidrick GalecioNo ratings yet

- Digest Sy Vs Estate of Ogos R 1Document2 pagesDigest Sy Vs Estate of Ogos R 1Jane Zahren AustriaNo ratings yet

- Alegre Vs Reyes DigestDocument3 pagesAlegre Vs Reyes DigestEric TamayoNo ratings yet

- Dalupan V GacottDocument4 pagesDalupan V GacottJack BeanNo ratings yet

- Grace Poe Disqualification Case (Essay)Document2 pagesGrace Poe Disqualification Case (Essay)John Bryan AldovinoNo ratings yet

- EDocument12 pagesEPrankyJellyNo ratings yet

- Compiled May 5, 2017 Case DigestDocument16 pagesCompiled May 5, 2017 Case DigestGrace CastilloNo ratings yet

- 21-Cruz Vs IturraldeDocument6 pages21-Cruz Vs IturraldeLexter CruzNo ratings yet

- Williams & Ferrier For Petitioner. Cohn, Fisher & Dewit For RespondentDocument26 pagesWilliams & Ferrier For Petitioner. Cohn, Fisher & Dewit For RespondentDiane UyNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument2 pagesCase DigestLance Cedric Egay Dador100% (1)

- Adm. Case No. 4673. April 27, 2001 ATTY. HECTOR TEODOSIO, Petitioner, vs. MERCEDES NAVA, Respondent. FactsDocument6 pagesAdm. Case No. 4673. April 27, 2001 ATTY. HECTOR TEODOSIO, Petitioner, vs. MERCEDES NAVA, Respondent. FactsshahiraNo ratings yet

- Cayetano Vs MonsodDocument2 pagesCayetano Vs MonsodDayanski B-mNo ratings yet

- Fil-Garcia Inc. v. Hernandez, AC 7129, 2008Document8 pagesFil-Garcia Inc. v. Hernandez, AC 7129, 2008Jerald Oliver MacabayaNo ratings yet

- Chavez Vs LazaroDocument1 pageChavez Vs LazaroCeresjudicataNo ratings yet

- Piatt v. Abordo 58 Phil. 350 (1933)Document2 pagesPiatt v. Abordo 58 Phil. 350 (1933)Unknown userNo ratings yet

- Re Atty. Lynda Changuile PDFDocument10 pagesRe Atty. Lynda Changuile PDFLaindei Lou TorredaNo ratings yet

- Sta. Maria vs. TuazonDocument15 pagesSta. Maria vs. Tuazonchan.aNo ratings yet

- Basic Legal and Judicial Ethics NotesDocument6 pagesBasic Legal and Judicial Ethics NotesJS Sarmiento Jr.No ratings yet

- Aquino V ComelecDocument16 pagesAquino V ComelecJanMikhailPanerioNo ratings yet

- Villanueva V Sta AnaDocument1 pageVillanueva V Sta AnaGio RuizNo ratings yet

- Occena vs. MarquezDocument4 pagesOccena vs. MarquezGodofredo Ponteras IIINo ratings yet

- Susan Go and The People of The PhilippinesDocument11 pagesSusan Go and The People of The PhilippinesSam ting wongNo ratings yet

- People Vs Galvez ScriptDocument10 pagesPeople Vs Galvez ScriptAnonymous BvmMuBSwNo ratings yet

- in Re ArgosinoDocument2 pagesin Re ArgosinoMir SolaimanNo ratings yet

- Rule 138Document4 pagesRule 138Adalia L. DinapoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-4221Document1 pageG.R. No. L-4221Teresa CardinozaNo ratings yet

- CONSTI Magalona vs. ErmitaDocument2 pagesCONSTI Magalona vs. ErmitaPafra BariuanNo ratings yet

- Cases Legal EthicsDocument57 pagesCases Legal EthicsPipoy AmyNo ratings yet

- Tria-Samonte V Obias (2013)Document2 pagesTria-Samonte V Obias (2013)katrina_petillaNo ratings yet

- Piczon V Piczon GR No L29139Document3 pagesPiczon V Piczon GR No L29139Mary LeandaNo ratings yet

- Section 7-D Azarcon-v-SandiganbayanDocument2 pagesSection 7-D Azarcon-v-SandiganbayanKristelle IgnacioNo ratings yet

- CD - 91. Zuo v. CabredoDocument2 pagesCD - 91. Zuo v. CabredoCzarina Cid100% (1)

- CrimPro G.R. No. 158763 Miranda Vs TuliaoDocument5 pagesCrimPro G.R. No. 158763 Miranda Vs TuliaoJimenez LorenzNo ratings yet

- 005-Caltex (Philippines) Inc. v. Philippine Labor OrganizationDocument1 page005-Caltex (Philippines) Inc. v. Philippine Labor OrganizationwewNo ratings yet

- Mercado V VitrioloDocument2 pagesMercado V VitrioloGillian CalpitoNo ratings yet

- Buenavista vs. Atty. Amado by Justice LeonenDocument9 pagesBuenavista vs. Atty. Amado by Justice LeonenRojbNo ratings yet

- Luceres v. Trinidad-AbayaDocument2 pagesLuceres v. Trinidad-AbayaMaya Angelique JajallaNo ratings yet

- Case Digest AssignmentDocument37 pagesCase Digest AssignmentNichol GamingNo ratings yet

- Gacad vs. ClapisDocument1 pageGacad vs. ClapismwaikeNo ratings yet

- 114.) People v. BacangDocument2 pages114.) People v. BacangRose de Dios100% (1)

- Concrete Aggregates v. CADocument1 pageConcrete Aggregates v. CASerneiv YrrejNo ratings yet

- Chiongbian Vs OrbosDocument5 pagesChiongbian Vs OrbosSophiaFrancescaEspinosaNo ratings yet

- Glynna Foronda-Crystal Vs Aniana LawasSon G.R. No. 221815 November 29, 2017Document9 pagesGlynna Foronda-Crystal Vs Aniana LawasSon G.R. No. 221815 November 29, 2017MakilingE.CarlosNo ratings yet

- Catalan v. Silvosa AC No. 7360Document2 pagesCatalan v. Silvosa AC No. 7360MistakenNo ratings yet

- 25.) Pedro vs. Provincial Board of RizalDocument1 page25.) Pedro vs. Provincial Board of RizalAphrNo ratings yet

- Gachalan Promotions vs. NaldozaDocument5 pagesGachalan Promotions vs. NaldozaReth GuevarraNo ratings yet

- ROMULO ABROGAR AND ERLINDA ABROGAR v. COSMOS BOTTLING COMPANY AND INTERGAMESINCDocument3 pagesROMULO ABROGAR AND ERLINDA ABROGAR v. COSMOS BOTTLING COMPANY AND INTERGAMESINCKylie DanielleNo ratings yet

- d3. Labay v. Sandiganbayan (Criminal Due Process)Document4 pagesd3. Labay v. Sandiganbayan (Criminal Due Process)MarkNo ratings yet

- Minoza V LopezDocument1 pageMinoza V LopezajyuNo ratings yet

- 29 Centeno Vs PornillosDocument1 page29 Centeno Vs PornillosAngie DouglasNo ratings yet

- CASE 6 - NAKPIL v. VALDESDocument3 pagesCASE 6 - NAKPIL v. VALDESrudilyn.palero9No ratings yet

- Nakpil vs. ValdesDocument11 pagesNakpil vs. ValdesAdrianne BenignoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. L-18924 - PEOPLE OF THE PHIL. vs. WONG CHENGDocument4 pagesG.R. No. L-18924 - PEOPLE OF THE PHIL. vs. WONG CHENGPatricia Anne RamelNo ratings yet

- Southern Hemisphere vs. Anti-Terrorism G.R. Nos. 178552, 178554, 178581, 178890, 179157, 179461Document17 pagesSouthern Hemisphere vs. Anti-Terrorism G.R. Nos. 178552, 178554, 178581, 178890, 179157, 179461Patricia Anne RamelNo ratings yet

- People vs. Dacuycuy G.R. No. L-45127Document5 pagesPeople vs. Dacuycuy G.R. No. L-45127Patricia Anne RamelNo ratings yet

- Liang Vs People G.R. No. 125865Document2 pagesLiang Vs People G.R. No. 125865Patricia Anne RamelNo ratings yet

- Integrative Performance TaskDocument4 pagesIntegrative Performance TaskPatricia Anne RamelNo ratings yet

- Contracts Which Can Be Specifically EnforcedDocument19 pagesContracts Which Can Be Specifically EnforcedUditanshu Misra100% (1)

- Property and Equity 2Document101 pagesProperty and Equity 2Bc Violá100% (2)

- PowerpointDocument15 pagesPowerpointJames PandianNo ratings yet

- CD - 2. Sinaon v. SoronganDocument1 pageCD - 2. Sinaon v. SoronganCzarina CidNo ratings yet

- Topic Management Prerogative To Discipline EmployeesDocument13 pagesTopic Management Prerogative To Discipline EmployeesPaul100% (1)

- Ch. VII Breach of Fiduciary Duty Causes of Action and Defenses 65pagesDocument65 pagesCh. VII Breach of Fiduciary Duty Causes of Action and Defenses 65pagesQreus One100% (1)

- 2021 Pre Week Notes in Commercial Law Based On Reduced SyllabusDocument97 pages2021 Pre Week Notes in Commercial Law Based On Reduced SyllabusMich FelloneNo ratings yet

- Last Will and TestamentDocument10 pagesLast Will and TestamentAbdullaNo ratings yet

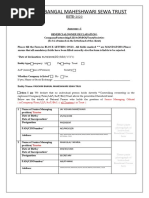

- Maheshwari Trust Anx IDocument4 pagesMaheshwari Trust Anx ISoumojit DuttaNo ratings yet

- Heirs of Francisco Narvasa Vs ImbornalDocument13 pagesHeirs of Francisco Narvasa Vs ImbornalLyceum LawlibraryNo ratings yet

- Business Trust Agreement Contract FormDocument5 pagesBusiness Trust Agreement Contract Formnelson rodriguezNo ratings yet

- CS in Practice Ready Reckoner (July 2019) ICSIDocument282 pagesCS in Practice Ready Reckoner (July 2019) ICSIbuchasiaNo ratings yet

- The Informer: "Those Who Say It Cannot Be Done Should Not Interfere With Those of Us Who Are Doing It"© - S. HickmanDocument4 pagesThe Informer: "Those Who Say It Cannot Be Done Should Not Interfere With Those of Us Who Are Doing It"© - S. HickmanNatasha MyersNo ratings yet

- Sample Comprehensive Married WillDocument18 pagesSample Comprehensive Married WillKings TGNo ratings yet

- Charitable Trust OrdinanceDocument23 pagesCharitable Trust OrdinanceAzrieNo ratings yet

- Compare and Contrast The Testamentary Freedom in Ethiopian Civil Code With That of Civil Law Legal SystemDocument3 pagesCompare and Contrast The Testamentary Freedom in Ethiopian Civil Code With That of Civil Law Legal Systemliya100% (1)

- Wealth, Income, and Power - G. William DomhoffDocument18 pagesWealth, Income, and Power - G. William DomhoffCocceiusNo ratings yet

- Bar Questions 1 3 MergedDocument48 pagesBar Questions 1 3 MergedAerith Alejandre100% (2)

- Related Case LawsDocument12 pagesRelated Case LawsNikita HasijaNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University: Submitted To Submitted byDocument23 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University: Submitted To Submitted bySushil JindalNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals Third CircuitDocument5 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals Third CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Southpac Trust - Offshore Trustee ServicesDocument5 pagesSouthpac Trust - Offshore Trustee Servicesomninetltd100% (2)

- 10 - Chapter 7Document53 pages10 - Chapter 7Manas Ranjan SamantarayNo ratings yet

- Form 26AS: Annual Tax Statement Under Section 203AA of The Income Tax Act, 1961Document3 pagesForm 26AS: Annual Tax Statement Under Section 203AA of The Income Tax Act, 1961Manav ChaudharyNo ratings yet