Long Term Outcome of Functional Independence and Quality of Life After Traumatic SCI in Germany

Long Term Outcome of Functional Independence and Quality of Life After Traumatic SCI in Germany

Uploaded by

Luis Diego Verastegui LeguaCopyright:

Available Formats

Long Term Outcome of Functional Independence and Quality of Life After Traumatic SCI in Germany

Long Term Outcome of Functional Independence and Quality of Life After Traumatic SCI in Germany

Uploaded by

Luis Diego Verastegui LeguaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Long Term Outcome of Functional Independence and Quality of Life After Traumatic SCI in Germany

Long Term Outcome of Functional Independence and Quality of Life After Traumatic SCI in Germany

Uploaded by

Luis Diego Verastegui LeguaCopyright:

Available Formats

www.nature.

com/sc

ARTICLE OPEN

Long term outcome of functional independence and quality of

life after traumatic SCI in Germany

1✉ 1

Florian Möller , Rüdiger Rupp , Norbert Weidner1, Christoph Gutenbrunner 2

, Yorck B. Kalke 3

and Rainer F. Abel 4

© The Author(s) 2021

STUDY DESIGN: Multicenter observational study.

OBJECTIVE: To describe the long-term outcome of functional independence and quality of life (QoL) for individuals with traumatic

and ischemic SCI beyond the first year after injury.

SETTING: A multicenter study in Germany.

METHODS: Participants of the European multicenter study about spinal cord injury (EMSCI) of three German SCI centers were

included and followed over time by the German spinal cord injury cohort study (GerSCI). Individuals’ most recent spinal cord

independence measure (SCIM) scores assessed by a clinician were followed up by a self-report (SCIM-SR) and correlated to selected

items of the WHO short survey of quality of life (WHO-QoL-BREF).

RESULTS: Data for 359 individuals were obtained. The average time passed the last clinical SCIM examination was 81.47 (SD 51.70)

months. In total, 187 of the 359 received questionnaires contained a completely evaluable SCIM-SR. SCIM scores remained stable

with the exception of reported management of bladder and bowel resulting in a slight decrease of SCIM-SR of −2.45 points (SD

16.81). SCIM-SR scores showed a significant correlation with the selected items of the WHO-QoL-BREF (p < 0.01) with moderate to

strong influence.

CONCLUSION: SCIM score stability over time suggests a successful transfer of acquired independence skills obtained during

primary rehabilitation into the community setting paralleled by positively related QoL measurements but bladder and bowel

management may need special attention.

Spinal Cord (2021) 59:902–909; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-021-00659-9

INTRODUCTION Objectives

Achieving the highest level of functional independence is one Within the GerSCI project, we describe and analyze individuals’

of the main objectives of primary rehabilitation of individuals long-term changes of functional independence in a community-

with SCI. dwelled setting. We hypothesize that (1) an overall stable course

Former studies were able to show a favorable relationship of these variables can be observed, and (2) individuals’

between functional independence at discharge and multiple long- reported QoL is positively related to their level of functional

time outcomes such as rehospitalization rates, probability of living independence.

in a community setting, and employment status. There is a wealth

of data analyzing the course of functional independence within

the first year after the onset of SCI and the relationship with METHODS

different aspects of quality of life (QoL) for individuals living with Study design

SCI. However, data following individuals’ independence and Multicenter observational study linking clinical data of individuals with

correlation with QoL over a long-time period are rare [1–3]. traumatic or ischemic SCI obtained in the first year after the onset of SCI as

In 2013, with their initiative “International perspectives on spinal part of the European multicenter study about spinal cord injury (EMSCI) to

cord injury” the World Health Organization (WHO) invited to long-term data derived from a longitudinal study (GerSCI) on self-reported

independence and QoL.

investigate the “lived experience of people with SCI across the life

course and throughout the world” [4]. In response to the request

of the WHO a cooperative effort of two major German scientific Participants and collection of data

societies with a strong focus on rehabilitation of individuals with The participants of our survey were followed within the context of the

SCI (German Medical SCI society (DMGP) and German Society for GerSCI study. GerSCI inclusion criteria are at least one SCI-related hospital

admission (initial admission as well as any other in the course of time) at a

Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (DGPRM)) started the project minimum age of 18 years in the participating centers between January

“German Spinal Cord Injury Cohort Study” (GerSCI) as part of the 1995 and December 2016, sufficient knowledge of German language,

“International Spinal Cord Injury Survey” (InSCI). domestic residency, completed initial rehabilitation and SCI onset at least

1

Spinal Cord Injury Center, Heidelberg University Hospital, Heidelberg, Germany. 2Department of Rehabilitation Medicine, Hannover Medical School, Hanover, Germany.

Orthopedic Department, SCI Centre - Ulm University, Ulm, Germany. 4Klinik Hohe Warte, Hospital Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany. ✉email: florian.moeller@chiru.med.uni-giessen.de

3

Received: 11 December 2020 Revised: 12 June 2021 Accepted: 14 June 2021

Published online: 25 June 2021

F. Möller et al.

903

12 months ago. GerSCI excluding criteria as congenital and neurodegen- regression was used to determine a relationship between differences of

erative SCI correspond with the excluding criteria of EMSCI [5, 6]. SCIM sum-scores and sub-scores and time since the last EMSCI

For three EMSCI centers (Bayreuth, Heidelberg, and Ulm) participants examination. Paired t-testing was used to analyze differences between

were systemically screened for possible participation in the GerSCI study. SCIM sum-scores and sub-scores obtained in EMSCI and at follow-up in

The dataset of the EMSCI examination contains results from five defined GerSCI.

points (<15 days, 1, 3, 6, and 12 months) after SCI onset. The results of the Scores to items of the WHO-QoL-BREF are presented by descriptive

latest available examination and contact details were extracted from the statistics, the connection between these scores and the level of lesion

EMSCI database. Individuals were designated with a GerSCI ID and the EMSCI (tetra-/paraplegia) was analyzed by Kruskal–Wallis-testing, Spearman’s rank

ID was deleted from the dataset. The GerSCI questionnaire was mailed to the correlation analysis was performed to investigate the dependency of QoL

EMSCI participants in April 2017 (Ulm), July 2017 (Bayreuth), and November on individuals’ SCIM-III-SR sum scores and sub-scores.

2017 (Heidelberg) followed by a reminder in case no response has been Possible center effects were investigated for key demographic

received within 4 weeks. characteristics (responding and non-responding individuals), differences

After mailing the reminder remaining individual-related data (e.g., in SCIM sub-scores and sum-score over time (responding individuals), and

contact details) were deleted from our dataset which was thereby for QoL measurements (responding individuals) by Kruskal–Wallis-testing.

anonymized. The subsequent individual allocation of GerSCI results to

the dataset solely was performed with the help of individuals GerSCI ID.

All GerSCI responses were individually mailed by the study participants RESULTS

to the GerSCI coordinating site, the Department for Rehabilitation Sample characteristics

Medicine of the Hannover Medical School (Prof. Dr. Gutenbrunner), and

entered into a database using dedicated software (Weingabe; Rolf A total of 1209 individuals enrolled in the EMSCI data collection of

Rimmele, Altenholz, Germany) by trained staff members. Data input was the study centers met the GerSCI inclusion criteria. Due to a

performed twice and any deviations were retraced and cleared by a senior foreign residency, 20 individuals could not be included in the

staff member. Alternatively, individuals could answer an online ques- GerSCI survey. In 21 cases we were informed about the death of

tionnaire. When using the paper-pencil questionnaire data was checked for the individuals and 271 individuals could not be contacted, e.g.,

incoherent responses to connected items with conditional response due to invalid address information (Fig. 1). We were able to

options. Finally, individuals GerSCI results were connected to the dataset. contact 917 (75.85%) persons successfully.

Within the four weeks response time to the initial invitation for

1234567890();,:

Outcome measures GerSCI participation, 235 replies were received. After an additional

The spinal cord independence measure (SCIM) is an established outcome reminder, 124 additional responses were collected. Until February

measure for functional independence. It was developed to account for the 2018, in total 359 questionnaires were received corresponding to

specific aspects of measuring the functional independence of individuals 39.15% of all successfully contacted individuals.

with SCI. Its third version (SCIM-III), developed from the initial version Key demographic and neurologic lesion characteristics of

introduced in 1997, has gained large acceptance in the SCI community as a responding individuals are shown in Table 1 grouped by para-

reliable assessment of functional impairments [7]. The SCIM-III consists of 19

items organized in the three sub-scales “self-care”, “respiration and sphincter and tetraplegia as last documented in the EMSCI database [13].

management” and “mobility” [8]. The EMSCI database is inter alia including The majority (74.4%) of responding persons are male with a mean

International Standards of Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury last observed SCIM-III total score of 61.67 (SD 26.70) points. The

(ISNCSCI) and SCIM-III assessments at defined time points during the first year average total follow-up is 81.47 (SD 51.70) months. In 82.70% of all

after injury, representing the largest collection of SCIM assessments ever cases, the average follow-up time was longer than 24 months.

recorded. The SCIM-III is available in a validated observation-based, interview- Further analyzing key demographic and lesion characteristics of

based, and self-reported (SCIM-III-SR) version. The latter was introduced into all non-responding and non-successfully contacted individuals (n

the GerSCI survey. Even if possibly biased by a home-dwelled setting and = 850) showed a mean difference of age at the point of

unsupervised self-reporting, former studies have found the self-reported

contacting of +3.12 (mean: 59.30 vs. 56.18) years, a slightly

version to be comparable to the interviewed and observed versions [7–9].

Differences of participants’ sum-score and sub-scores between the last SCIM-

increased proportion of female individuals of +4.40% (30.00% vs.

III examination within the EMSCI study and the SCIM-III-SR surveyed within 25.60%) and an increased time since SCI onset of +1.36 (mean:

GerSCI were analyzed. Whenever possible (fully completed SCIM-III-SR within 8.78 vs. 7.42) years. The proportion of tetraplegia did only differ

GerSCI) differences of the sum-scores were analyzed. In addition, differences minor (+0.3%) from those of the responding individuals. There

of all sub-scores were analyzed. were no significant center effects for key demographic character-

The questionnaire of the GerSCI study also contained six selected items istics for responding and non-responding individuals. Only the

of the short survey of quality of life by the WHO (WHO-QoL-BREF) [10]. difference in time since SCI onset was statistically significant

Included items address the perceived overall life quality (WHO-QoL-BREF (Mann–Whitney–U-testing: U = 120255.50, p = 0.01, n = 1209)

item 1), overall health status (item 2), ability to perform daily living with a merely weak effect size according to Cohen.

activities (item 17), self-satisfaction (item 19), satisfaction with personal

relationships (item 20), and the satisfaction with the conditions of the There is conformity of self-reported classification of para-/

personal living place (item 23) reported on a five-tier Likert-scale [11]. Since tetraplegia and the classification according to the last available

GerSCI only included six items of this inventory the analysis performed was ISCNSCI neurological level of injury (NLI) documented in the EMSCI

different from the standardized evaluation as defined by the WHO. As database. The NLI refers to the most caudal segment with intact

target measurement for QoL item 1 (“How would you rate your quality of sensory and motor function [14]. Tetraplegia was divided into two

life?”) addressing the overall life quality was chosen. As target measure- subgroups with NLI of C1–C5 and C6–Th1 as suggested by the

ment for independence item 17 (“How satisfied are you with your ability to International Spinal Cord Society. There is good agreement of self-

take care of everyday tasks?”) addressing the ability to perform daily living reported level of lesion (tetra-/paraplegia) within GerSCI to EMSCI

activities was selected. data for all responding individuals (85.53% for NLI from C1 to C5,

79.50% for NLI C6-T1, and 83.50% for NLI rostral to Th1).

Statistics

Data analysis was carried out using “Statistical Package for the Social SCIM-III-SR analysis

Sciences (SPSS)” version 22 (International Business Machines (IBM) As can be seen from Fig. 1, from all 359 questionnaires considered

Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

for further analyses 187 (52.09%) included a complete correctly filled

Descriptive statistics present the sample characteristics of responding

and non-responding individuals as well as of evaluability of the returned out SCIM-III-SR section corresponding to 15.47% of all 1209

SCIM-III-SR questionnaires. In addition, the connection between frequently individuals eligible for the survey. In the incomplete 172 ques-

occurring incoherent responses to SCIM-III-SR and level of lesion (tetra-/ tionnaires, in total 436 items were not completely evaluable because

paraplegia) (Mann–Whitney–U-testing), age (regression analysis), and level of incoherent responses to connected items with conditional

of formal education (correlation analysis) was investigated [12]. Linear response options or missing answers. Figure 2 provides information

Spinal Cord (2021) 59:902 – 909

F. Möller et al.

904

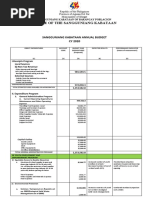

Fig. 1 STROBE flowchart. Flowchart in line with the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology)

statement (http://www.strobestatement.org) illustrating the process, numbers, and dropout of study participants.

on these items grouped by lesion level (tetra-/paraplegia) according completed and analyzed. As can be seen from Fig. 2 apart from a

to the EMSCI database. As displayed in Fig. 1, in total 187 SCIM-III-SR baseline of 10–20 non-evaluable entries per item, the items bladder

sum-scores, 322 self-care sub-scores, 245 respiration, and sphincter management (VI), bowel management (VII), stair management (XV),

management sub-scores and 262 mobility sub-scores were transfer from wheelchair to the car (XVI), and transfer from ground

Spinal Cord (2021) 59:902 – 909

F. Möller et al.

905

to a wheelchair (XVII) contained the highest number of non-

Table 1. Demographic and neurologic characteristics of individuals

evaluable entries and were thereby identified as error-prone.

responding to the GerSCI survey.

Analysis showed no correlation between the education degree

Classification of para- and tetraplegia according to the according to the classification of the UNESCO [12] as generated from

EMSCI database the GerSCI questionnaire and the number of non-evaluable SCIM-III-

SR items. A weak regression between the age of the individuals and

Paraplegia Tetraplegia Total

the number of non-evaluable items was identified. With the

(n = 170) (n = 189) (n = 359)

increasing age of individuals also the number of non-evaluable

Age at follow-up (years) items increases (F (1,356) = 8.561, p = 0.004) corresponding to a

Mean 53.82 58.29 56.18 weak effect size of f = 0.15 according to Cohen [15]. Further focusing

Range 20–87 19–90 19–90 on the items VI, VII, XV, XVI, and XVII with the highest number of

non-evaluable SCIM-III-SR entries, the last documented correspond-

Median 53.00 62.00 57.00

ing SCIM-III item results from the EMSCI database were analyzed.

SD 15.20 18.42 17.10 Individuals being not able to answer the corresponding SCIM-III-SR

Gender item tended to have higher SCIM-III item scores in the EMSCI

Male 126 (74.1%) 141 (74.6%) 267 (74.4%) examination for all error-prone items. Significance in

Mann–Whitney–U-testing has been seen for the items VI (U =

Female 44 (25.9%) 48 (25.4%) 92 (25.6%)

−2.316, p = 0.02, n = 359), XV (U = −3.669, p = 0.00, n = 359), and

ASIA Impairment Scale according to the latest available EMSCI examination XVII (U = −2.598, p = 0.01, n = 227) corresponding to a weak to

A 66 (38.8%) 39 (20.6%) 105 (29.2%) moderate effect size according to Cohen for all three analyzes.

B 19 (11.2%) 15 (7.9%) 34 (9.5%) We matched the retraceable (fully completed) entries of the

sub-scores (ncategory 1 = 322; ncategory 2 = 245; ncategory3 = 262) and

C 25 (14.7%) 25 (13.2%) 50 (13.9%)

the sum-score (n = 187) of the SCIM-III-SR from the GerSCI survey

D 59 (34.7%) 108 (57.1%) 167 (46.5%) to the last SCIM-III sum-score and sub-scores of each individual in

Missing 1 (0.6%) 2 (1.0%) 3 (0.9%) the EMSCI database. The detailed results can be found in Table 2

Demographic and neurologic characteristic of individuals who participated and Fig. 3 divided by the sub-scores and individual’s level of the

in the GerSCI survey. ASIA Impairment Scale definition: A = no motor or lesion as documented in the EMSCI database. Due to varying

sensory function is preserved in the sacral segments S4–S5; B = sensory numbers between followed sub-scores and sum-scores also

but not motor function is preserved below the neurological level and cumulated differences of all sub-scores deviate from the

includes the sacral segments S4–5 (light touch or pinprick at S4–5 or deep difference of the sum-score over time (Table 2 + Fig. 3). The

anal pressure) AND no motor function is preserved more than three levels mean follow-up time was 82.54 (SD 53.28) months and thereby

below the motor level on either side of the body. C = motor function is

similar to the average follow-up of 81.47 (SD 51.70) months of all

preserved at the most caudal sacral segments for voluntary anal

contraction (VAC) OR the patient meets the criteria for sensory incomplete

returned questionnaires. The mean last SCIM-III assessed by a

status (sensory function preserved at the most caudal sacral segments clinician also closely matches one of all individuals responding

S4–5 by LT, PP, or DAP), and has some sparing of motor function more than (61.25 vs. 61.67 points).

three levels below the ipsilateral motor level on either side of the body. At first glance, SCIM-III-SR sum-score (n = 187) with a mean

(This includes key or non-key muscle functions to determine motor difference of −2.45 (SD 16.81) over time stayed more or less the same

incomplete status). For AIS C—less than half of key muscle functions below in comparison with the last SCIM-III assessed within EMSCI with a

the single NLI have a muscle grade ≥ 3; D = motor function is preserved slight tendency of a deterioration. Further focusing on the sub-scores

below the neurological level, and at least half of key muscles below the with a difference close to zero the sub-scores for self-care (mean

neurological level have a muscle grade of 3 or more.

difference = −0.83 points, SD 4.20) and mobility (mean difference =

ASIA American spinal injury association.

0.22 points, SD 7.44) stayed stable over time but sub-score for

respiration and sphincter management showed an alteration of −2.38

(SD 9.043) points. The slight deterioration of the sum score is mainly

caused by this alteration. Further describing this alteration, we

70

analyzed differences overtime for all items (items 5–8) of the sub-scale

number of non-evaluable datasets

60 “respiration and sphincter management”. With an average change of

50 −0.09 points (SD 0.996) the respiration score (item 5) stayed stable

40 over time. As can be seen from Fig. 4, the deterioration is based on a

30 lower level of independence in the bladder (mean total difference

20

item 6: −1.20 points, SD 5.514) and bowel management (mean total

10

difference item 7: −1.23 points, SD 4.412) over time throughout all

groups. In this case too, due to varying numbers of followed items,

0

I Iia IIb IIIa IIIb IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII XII XIV XV XVI

XVI

I

numbers in analysis differ.

Paraplegia (NLI below Th1) 9 8 8 8 5 3 5 20 27 4 3 5 10 5 5 9 13 5 5 Linear regression showed no influence of the time passed since

Tetraplegia (NLI C6-Th1) 1 2 1 2 1 1 3 4 8 4 1 3 1 4 3 4 4 3 6 the last examination within EMSCI to the difference in SCIM-III

Tetraplegia (NLI C1-C5) 8 5 3 3 3 3 6 31 30 12 5 11 14 8 10 9 22 18 22

sum- and sub-scores over time. Furthermore, no influence of time

SCIM-III-SR-items

since SCI onset to SCIM-III last assessed by a clinician or SCIM

Fig. 2 Histogram of the number of non-evaluable SCIM-III-SR differences over time was seen. Kruskal–Wallis-testing showed no

items of the GerSCI questionnaires grouped by level of the lesion. center effects. Paired t-testing showed significant differences (p <

Legend: I: Feeding, IIa: Bathing (upper extremities), IIb: Bathing 0.01) for sub-scales “self-care” and “mobility” and for sum-scores

(lower extremities), IIIa: Dressing (upper extremities), IIIb: Dressing (p < 0.05) within GerSCI and EMSCI. These differences do not even

(lower extremities), IV: Grooming, V: Respiration, VI: Sphincter reach a weak effect size according to Cohen (r < 0.1).

management bladder, VII: Sphincter management bowel, VIII: Use

of the toilet, IX: Mobility in bed, X: Bed to wheelchair transfer, XI: Focusing on the lesion level categories, also the deviation for

Wheelchair to toilet transfer, XII: Mobility I, XIII: Mobility II, XIV: individuals with NLI between C6 and T1 is striking (Table 2 and

Mobility III, XV: stair management, XVI: Wheelchair to car transfer, Fig. 3). Individuals with this lesion level tend to worsen in all sub-

XVII: Ground to wheelchair transfer. NLI: Neurological level of the scores more than all other individuals. Due to the relatively small

lesion. number of individuals significance only can be seen for the

Spinal Cord (2021) 59:902 – 909

F. Möller et al.

906

Table 2. SCIM follow-up.

Classification according to EMSCI database

Tetraplegia NLI C1–C5 Tetraplegia NLI C6–Th1 Paraplegia NLI below Th1 total

SCIM sub-score category I—self care (0–20)

Sub-scores available 134 36 152 322

SCIM-III (EMSCI) 10.68 15.56 17.05 14.19

SCIM-III-SR (GerSCI) 10.31 12.92 16.16 13.36

Difference −0.37 −2.64 −0.89 −0.83b

SDdifference 4.252 5.144 3.808 4.202

SCIM sub-score category II—respiration and sphincter management (0–40)

Sub-scores available 96 25 124 245

SCIM-III (EMSCI) 24.01 31.12 30.52 28.03

SCIM-III-SR (GerSCI) 23.56 26.24 27.15 25.65

Difference −0.45 −4.88 −3.37 −2.38

SDdifference 8.641 8.941 9.152 9.043

SCIM sub-score category III—mobility (0–40)

Sub-scores available 98 29 135 262

SCIM-III (EMSCI) 15.06 21.90 20.11 18.42

SCIM-III-SR (GerSCI) 15.42 20.97 20.48 18.64

Difference 0.36 −0.93 0.37 0.22b

SDdifference 7.823 9.098 6.779 7.442

SCIM sum-score—(0–100)

Sum-scores available 67 21 99 187

SCIM-III (EMSCI) 48.52 69.67 68.09 61.25

SCIM-III-SR (GerSCI) 49.28 61.57 64.66 58.80

Differencea 0.76a −8.10a −3.43a −2.45a,b

SDdifference 18.008 21.222 14.534 16.811

SCIM follow-up divided by classification of tetraplegia/paraplegia as assigned within the EMSCI survey.

a

Due to varying numbers between followed (fully completed) sum-scores and sub-scores also cumulated differences of all sub-scores deviate from the

difference of the sum-score over time.

b

Paired t-testing showed significance for differences (p < 0.05). Differences do not reach a weak effect size according to Cohen (r < 0.1).

Fig. 4 SCIM follow-up (respiration & sphincter management).

Boxplot illustrating the delta of SCIM-III and SCIM-III-SR items 6–8

Fig. 3 SCIM follow-up. Boxplot illustrating the delta of SCIM-III and overtime (y-axis [points]) grouped by the level of lesion (x-axis) as

SCIM-III-SR sub-scores over time (y-axis [points]) grouped by the well as cumulated for all respondents (=total). Numbers included:

level of lesion (x-axis) as well as cumulated for all respondents item 6: n = 304 (NLI C1–C5 = 119, NLI C6-T1 = 35, paraplegia = 150);

(=total). Underlying data is displayed in Table 2. item 7: n = 294 (NLI C1–C5 = 120, NLI C6-T1 = 31, paraplegia= 143)

item 8: n = 339 (NLI C1–C5 = 138, NLI C6-T1 = 35, paraplegia = 166).

Spinal Cord (2021) 59:902 – 909

F. Möller et al.

907

Table 3. Correlation of SCIM-III-SR to WHO-QOL-BREF.

WHO-QoL-BREF:

“How would you rate your quality of life?” (1 “How satisfied are you with your ability to take care of everyday

[very poor]–5 [very good]) (WHO-QoL-BREF-1) tasks?” (1 [very dissatisfied]–5 [very satisfied]) (WHO-QoL-BREF-17)

SCIM-III-SR

Sub-score 1

Correlation coefficent r = 0.371a r = 0.482a

N 304 313

Sub-score 2

Correlation coefficent r = 0.248a r = 0.334a

N 235 242

Sub-score 3

Correlation coefficent r = 0.266a r = 0.399a

N 247 254

Sum-score

Correlation coefficent r = 0.310a r = 0.409a

N 178 185

Spearman-Rho’s correlation of SCIM-III-SR to selected target measurements of WHO-QoL-BREF (1 + 17) included in the GerSCI questionnaire. Sub-score 1 =

self-care, sub-score 2 = respiration and sphincter management, sub-score 3 = mobility.

a

Correlation is significant at level 0.01 (2-sides).

difference of SCIM-III sub-score addressing self-care It is questionable that the small deterioration of the respective sub-

(Mann–Whitney–U-testing: U = −1.994, p = 0.04) with a weak scores is linked in general to a relevant loss of independence in

effect-size according to Cohen (r = 0.11). individuals’ daily life but we emphasize that this deterioration is

linked to a worsening of management of bowel and bladder. In

WHO-QoL and correlation with SCIM-III-SR particular, our findings are consistent with former surveys char-

Individuals rated their overall QoL (WHO-QoL-BREF item 1—“How acterizing bladder and bowel dysfunction a rising and even life-

would you rate your quality of life?”) with 3.43 and their limiting functional problem for individuals with SCI over time mostly

independence in an everyday setting (WHO-QoL-BREF item 17 based on growing incontinency and obstipation [16–18].

—“How satisfied are you with your ability to take care of everyday Before the GerSCI study, there were no reliable, systemically

tasks?”) with 3.23 on a five-tier Likert-scale. Kruskal–Wallis-testing collected, community-based data available about the subjective

showed no center effects or significant differences for overall QoL wellbeing or the life situation of individuals affected by SCI in

between individuals with tetra- or paraplegia but a significantly Germany [19]. There are existing registries and databases, e.g., the

higher perceived independence (Chi-Square (2) = 25.623; p < 0.01) EMSCI database, but they focus on clinical data. The GerSCI study

for individuals with paraplegia compared to individuals with gave us the unique possibility to systemically combine clinical

tetraplegia with NLI C1–C5 (post hoc Dunn–Bonferroni-testing: data with an exploratory cross-sectional study [19]. Thereby our

z = −5.048, p < 0.01). group had the opportunity to analyze individuals’ long-time

The results of the Spearman-Rho correlation of the SCIM-III-SR course of functional independence and related QoL in addition to

sum-score and the sub-scores to the selected items are shown in the original study objectives of the EMSCI and GerSCI survey.

Table 3. The numbers of individuals included in the correlation The response rate of 39.15% (n = 359) can be considered as

analyses vary due to the partly usable sub-scale scores of the SCIM- gratifying high.

III-SR and the numbers of evaluable answers to the WHO-QoL-BREF For responding individuals’ the average age at the time of study

items within the GerSCI questionnaires. The numbers included are participation, gender distribution and proportion of tetra- and

shown in Table 3. A significant correlation (p < 0.01) of all SCIM-III- paraplegia mostly fit those of the non-responders. Furthermore,

SR sub-scores and for the sum-score can be seen with moderate to almost exact matching in comparison to the responders of the

partly strong effect-size (r > 0.5) for both selected items of WHO- nationwide GerSCI sample and good comparison to multiple other

QoL-BREF [15]. Detailed information on single sub-scores and western European InSCI samples can be seen for this parameter

target measurements selected can be found in Table 3. [20]. The time between SCI onset and current age was slightly

increased for the non-responding individuals. However, since this

only shows significance with a weak effect size for the difference

DISCUSSION in time since SCI onset between responders and non-responders,

It can be concluded that the functional independence achieved by we believe that the representativeness of the results from our

rehabilitative measures during primary rehabilitation was successfully study is comparable to other cohort studies such as the Swiss

maintained in the home environment after individuals’ discharge study (SwiSCI) [8].

from inpatient rehabilitation. As hypothesized, we did only identify Analyzing the returned questionnaires showed that filling in a

minor differences between the last SCIM-III score obtained within self-reported SCIM-III questionnaire imposed a higher challenge to

EMSCI and the GerSCI related SCIM-III-SR, which was determined on the participants than initially expected. In 2013, a Swiss validation

average 81 months later. Additionally, as initially expected we found a study under restricted conditions (e.g., inpatient-recruitment as

moderate to strong positive relationship between individuals’ well as the exclusion of patients with severe health conditions and

functional independence and their reported QoL. cognitive impairments) showed a quote of missing entries in 8.1%

However, deterioration of functional independence related to the of the SCIM-III-SR assessments. We recorded an almost six times

SCIM sub-scale of management of bowel and bladder was observed. higher rate of 47.91% under unsupervised conditions [8, 21].

Spinal Cord (2021) 59:902 – 909

F. Möller et al.

908

Particularly challenging were items concerning bladder and also closely match the one recorded in all EMSCI centers [23]. Taken

bowel management including connected items with conditional together, we strongly believe that our results concerning indepen-

response options. It has to be pointed out that our data does not dence and connected QoL are representative of a German collective

indicate a general trend of the inability to correctly fill out the of individuals with traumatic or ischemic SCI and possibly might be

questionnaire considering tetra- and paraplegia, complete and even transferable to other health care systems of industrialized

incomplete lesions, or the level of formal education. Solely striking in countries.

the analysis are cases connected with higher age and a higher score Another limitation is the restriction of our QoL analyses to only

of the corresponding SCIM-III item at the EMSCI survey showing a two items of the WHO-QOL-BREF questionnaire of the GerSCI

significantly lower ability to correctly fill out corresponding SCIM-III- survey. Life quality is an extensive, multi-faceted and somewhat

SR items. We must note, that individuals with a higher grade of contradictory concept hardly to be described in six dimensions

independence are more challenged to complete a SCIM-III-SR according to the WHO-QoL-BREF approach [24]. Even multi-

questionnaire. Explicit research concerning these difficulties is dimensional complex surveys like the SF-36 and the “Satisfaction

lacking. We saw more frequent non-selection or faulty multiple with life survey” (SWLS) are accompanied by limitations and do

selections of items with increasing independence. This may be due not automatically grant a widely accepted measurement of QoL

to a more difficult selection of the best-fitting item. [25]. The focus on only two specific items of the WHO-QoL-BREF

In this context, we strongly suggest offering a low-threshold reduces our possibilities to investigate life quality to a one-

possibility of using an online questionnaire in future surveys to dimensional approach. Furthermore, QoL is not solely impacted by

avoid incoherent responses. Whenever staff resources are avail- functional independence. For example, perceived high distress or

able, structured telephone interviews could be performed. For the exhaustion in accomplishing related demands (e.g., self-care or

future use of paper-pencil questionnaires, we suggest providing sphincter management) could negatively affect individuals QoL

more detailed and case-related fill-in instructions at least for the even without any real functional deterioration.

error-prone items concerning bladder and bowel management.

In addition, we were able to show a moderate to the strong Strengths

relationship between the SCIM-III-SR sum-score and sub-scores The high-quality documentation of clinical data in the ISO-9001

and our selected items for life-quality from WHO-QoL-BREF. As this certified EMSCI network is a clear strength of this analysis. Also,

instrument is supposed to be the most acceptable and established the size of the analyzed cohort renders the conclusions sound. The

one for QoL after spinal cord injury [2] we believe that our results approach of comparing each individual’s observed SCIM score to

are in line with the common understanding of functional the long-term follow-up self-reported SCIM score by data pooling

independence and QoL as affiliated outcome measures of initial is unique. The results provide new insights about the course of

rehabilitation investigating aspects not necessarily connected with functional independence and limitations of a truly self-reported

one another [22]. SCIM in home-dwelling collectives.

Taken together, our data suggest that comprehensive primary

rehabilitation efforts by dedicated SCI centers achieve levels of

independence and QoL which remain stable over time. Only CONCLUSION

independence in bowel and bladder management appears to In summary, we were able to create a long-term follow-up that

deteriorate. This requires more detailed analysis for better demonstrates the stability of functional independence in large parts.

understanding and possible prevention. In addition, we identified a slight deterioration concerning sphincter

and bowel management in a home-dwelling environment. We were

able to identify and analyze error-prone parts of the self-reported

LIMITATIONS SCIM-III questionnaire, which have not been previously reported.

This study has several limitations: according to the EMSCI inclusion Finally, we were able to show a moderate to the strong relationship

and exclusion criteria only traumatic and ischemic causes were between SCIM-III-SR scores and the perceived QoL.

included in the survey, therefore excluding a substantial and We conclude that empowering individuals with the highest

growing portion of non-traumatic causes of SCI such as tumors or level of independence achievable within their primary rehabilita-

degenerative diseases. tion is a long-lasting investment in their quality of life.

Several individuals were reported dead, in comparison to other

western European InSCI samples an elevated quote of close to

22% of individuals eligible were lost to follow-up and a substantial

number of individuals did not participate. DATA AVAILABILITY

The dataset generated and analyzed in the current study is available from the

Also following individuals by using the SCIM-III-SR is a limitation. corresponding author on request.

Even though formerly validated with comparable validity to the

SCIM performed by clinicians, the results might be biased by the

unsupervised self-report [8]. The poor reporting for items REFERENCES

connected to the bladder- and bowel management also might 1. Cohen JT, Marino RJ, Sacco P, Terrin N. Association between the functional

impair the reliability of our results. Nonetheless, it has to be independence measure following spinal cord injury and long-term outcomes.

pointed out that only a weak to moderate effect of increasing age Spinal Cord. 2012;50:728–33. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.50.

and independence of individuals were identified as significant 2. Hill MR, Noonan VK, Sakakibara BM, Miller WC. Quality of life instruments and

factors for poor reporting of SCIM-III-SR. definitions in individuals with spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord.

Furthermore, data have been collected in only 3 out of the overall 2010;48:438–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2009.164.

28 centers specialized in the rehabilitation of people with SCI in 3. Wirth B, van Hedel HJA, Kometer B, Dietz V, Curt A. Changes in activity after a

complete spinal cord injury as measured by the Spinal Cord Independence

Germany. Since treatment facilities are quite comparable between

Measure II (SCIM II). Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2008;22:145–53. https://doi.org/

centers in Germany, we have not seen any center effects and the 10.1177/1545968307306240.

demographic and lesion characteristics of our sample almost exactly 4. World Health Organization. International perspectives on spinal cord injury.

match those of the whole GerSCI sample we believe that our findings Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013.

are reliable enough for generalized conclusions about the long-term 5. Gutenbrunner C, Stokes EK, Dreinhöfer K, Monsbakken J, Clarke S, Côté P, et al.

progression of the functional independence in a community-dwelled Why rehabilitation must have priority during and after the COVID-19-pandemic: a

environment. As additional proof, the distribution of the American position statement of the Global Rehabilitation Alliance. J Rehabil Med. 2020;52:

spinal injury impairment scale (AIS) grades in the investigated cohort jrm00081 https://doi.org/10.2340/16501977-2713.

Spinal Cord (2021) 59:902 – 909

F. Möller et al.

909

6. Bökel A, Egen C, Gutenbrunner C, Weidner N, Moosburger J, Abel F-R, et al. Lobbach, Germany. The EMSCI study has been funded by the International

Querschnittlähmung in deutschland—eine befragung zur lebens- und versor- Foundation for Research in Paraplegia (IRP, Zuerich, Switzerland), Wings for Life

gungssituation von menschen mit querschnittlähmung. Rehabilitation. (WfL, Salzburg, Austria), and the German Foundation of Spinal Cord Injury (DSQ,

2020;59:205–13. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-1071-5935. Nürnberg, Germany).

7. Catz A, Itzkovich M, Agranov E, Ring H, Tamir A. SCIM—spinal cord independence

measure: a new disability scale for patients with spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord.

1997;35:850–6. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

8. Fekete C, Eriks-Hoogland I, Baumberger M, Catz A, Itzkovich M, Lüthi H, et al. FM was responsible for including patients in the survey, performing the survey at the

Development and validation of a self-report version of the Spinal Cord Independence single participating SCI centers, extracting and analyzing data, defining target

Measure (SCIM III). Spinal Cord. 2013;51:40–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2012.87. measurements writing the report, performing literature research, and creating tables

9. Itzkovich M, Shefler H, Front L, Gur-Pollack R, Elkayam K, Bluvshtein V, et al. SCIM and figures. RR was responsible for designing the study protocol, recruiting

III (Spinal Cord Independence Measure version III): reliability of assessment by participating centers, and defining target measurements. He is in charge of the

interview and comparison with assessment by observation. Spinal Cord. EMSCI database and contributed to writing the report and performing literature

2018;56:46–51. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2017.97. research. NW was contributing to defining target measurements, writing the report,

10. Gross-Hemmi MH, Post MWM, Ehrmann C, Fekete C, Hasnan N, Middleton JW. and performing literature research. YK was contributing to defining target

et al. Study protocol of the international spinal cord injury (InSCI) community measurements and provided feedback on the report. CG is the scientific head of

survey. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96(2 Suppl 1):S23–S34. https://doi.org/ the GerSCI project. He defined target measurements of the GerSCI survey, recruited

10.1097/PHM.0000000000000647. participating SCI centers for the GerSCI survey, and provided feedback on the report.

11. Harper A. WHOQOL-BREF: introdution, administration, scoring and generic verion RA was responsible for designing the study protocol, selecting target measurements,

of the assessment; 1996. and recruiting the participating SCI centers. He participated in writing the report. As a

12. Unesco. International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) 2011. Paris: senior author, he supervised the complete study process.

UNESCO 2012.

13. Roberts TT, Leonard GR, Cepela DJ. Classifications in brief: american spinal injury

association (ASIA) impairment scale. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2017;475:1499–504.

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-5133-4. FUNDING

14. Kirshblum SC, Burns SP, Biering-Sorensen F, Donovan W, Graves DE, Jha A. et al. Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

International standards for neurological classification of spinal cord injury

(revised 2011). J Spinal Cord Med. 2011;34:535–46. https://doi.org/10.1179/

204577211X13207446293695. STATEMENT OF ETHICS

15. Cohen J. A power primer. Psychological Bull. 1992;112:155–9. The EMSCI study (https://www.emsci.org, ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01571531) is

16. Lynch AC, Wong C, Anthony A, Dobbs BR, Frizelle FA. Bowel dysfunction fol- approved by the Committee of Ethics of the medical faculty of the University of

lowing spinal cord injury: a description of bowel function in a spinal cord-injured Heidelberg (Germany) under registration S-188/2003 and is under continuous

population and comparison with age and gender matched controls. Spinal Cord. internal and external quality management and control. The GerSCI study is approved

2000;38:717–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.sc.3101058 by the Committee of Ethics of the Medical University of Hannover (Germany) under

17. Biering-Sørensen F, Nielans HM, Dørflinger T, Sørensen B. Urological situation five registration 2017/7374.

years after spinal cord injury. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1999;33:157–61. https://doi.

org/10.1080/003655999750015925.

COMPETING INTERESTS

18. Autonomic dysfunction after spinal cord injury. Elsevier; 2006.

The authors declare no competing interests.

19. Blumenthal M, Geng V, Egen C, Gutenbrunner C. People with spinal cord injury in

Germany. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96(2 Suppl 1):S66–S70. https://doi.org/

10.1097/PHM.0000000000000584.

20. Fekete C, Brach M, Ehrmann C, Post MWM, Stucki G, Middleton J, et al. Cohort

ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

profile of the international spinal cord injury community survey implemented in Correspondence and requests for materials should be addressed to F.M.

22 countries. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2020;101:2103–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

apmr.2020.01.022 Reprints and permission information is available at http://www.nature.com/

21. Myers AM, Holliday PJ, Harvey KA, Hutchinson KS. Functional performance reprints

measures: are they superior to self-assessments? J Gerontol. 1993;48:M196–206.

22. Tramonti F, Gerini A, Stampacchia G. Individualised and health-related quality of Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims

life of persons with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2014;52:231–5. https://doi.org/ in published maps and institutional affiliations.

10.1038/sc.2013.156.

23. Pavese C, Schneider MP, Schubert M, Curt A, Scivoletto G, Finazzi-Agrò E. et al. Pre-

diction of bladder outcomes after traumatic spinal cord injury: a longitudinal cohort

study. PLoS Med. 2016;13:e1002041 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002041. Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons

24. The WHOQOL Group. The World Health Organization quality of life assessment Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing,

(WHOQOL): position paper from the World Health Organization. Soc Sci Med. adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give

1995;41:1403–9. appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative

25. Steeves JD, Lammertse D, Curt A, Fawcett JW, Tuszynski MH, Ditunno JF, et al. Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party

Guidelines for the conduct of clinical trials for spinal cord injury (SCI) as devel- material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless

oped by the ICCP panel: clinical trial outcome measures. Spinal Cord. indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the

2007;45:206–21. article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory

regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly

from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.

org/licenses/by/4.0/.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study is implemented and has been financed in the framework of the GerSCI

study as part of the InSCI study and was supported by the Manfred Sauer Foundation, © The Author(s) 2021

Spinal Cord (2021) 59:902 – 909

You might also like

- Sandy Hook ReportDocument284 pagesSandy Hook ReportLeakSourceInfoNo ratings yet

- Research Article CritiqueDocument8 pagesResearch Article Critiqueapi-654257930No ratings yet

- Prognosis of Six-Month Functioning After Moderate To Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review of Prospective Cohort StudiesDocument12 pagesPrognosis of Six-Month Functioning After Moderate To Severe Traumatic Brain Injury: A Systematic Review of Prospective Cohort StudiesYan Sheng HoNo ratings yet

- Time Since Injury Is Key To Modeling Trends in Aging and OverallDocument11 pagesTime Since Injury Is Key To Modeling Trends in Aging and OverallJuciara MouraNo ratings yet

- Structural and Functional Brain Abnormalities in Chronic Low Back Pain - A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesStructural and Functional Brain Abnormalities in Chronic Low Back Pain - A Systematic ReviewRodolfo MoraesNo ratings yet

- 1-s2.0-S0165032724001757-mainDocument8 pages1-s2.0-S0165032724001757-mainsergilpzrNo ratings yet

- Jung Yeon Choi Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment andDocument18 pagesJung Yeon Choi Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment andJean SolisNo ratings yet

- s40520 023 02681 8Document16 pagess40520 023 02681 8Moazzim Ali BhattiNo ratings yet

- Functioning of Stroke Survivors - A Validation of The ICF Core Set For Stroke in SwedenDocument9 pagesFunctioning of Stroke Survivors - A Validation of The ICF Core Set For Stroke in SwedenMuhammadMusa47No ratings yet

- Elderly ResectionDocument15 pagesElderly ResectionMaria MontañoNo ratings yet

- Rehabilitation of Social Communication Skills in PDocument10 pagesRehabilitation of Social Communication Skills in Pt6zyhmkdbrNo ratings yet

- Cervical Motor Dysfunction and Its Predictive Value For Long-Term Recovery in Patients With Acute Whiplash-Associated Disorders: A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesCervical Motor Dysfunction and Its Predictive Value For Long-Term Recovery in Patients With Acute Whiplash-Associated Disorders: A Systematic ReviewAndreea CristinaNo ratings yet

- Hyx 079Document7 pagesHyx 079Indira AndiningtyasNo ratings yet

- AVC Han2024Document14 pagesAVC Han2024antmoreiraNo ratings yet

- Journal Critique 1Document3 pagesJournal Critique 1刘宇瞳No ratings yet

- In The Quest of A Standard Index of Intrinsic Capacity. A Critical Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesIn The Quest of A Standard Index of Intrinsic Capacity. A Critical Literature ReviewDaniel HenriqueNo ratings yet

- FOUR - Peds Manuscript REV Oct 21Document24 pagesFOUR - Peds Manuscript REV Oct 21Riandini Pramudita RNo ratings yet

- Interrater Reliability of The Full Outline of Unresponsiveness Score and The Glasgow Coma Scale in Critically Ill PatientsDocument9 pagesInterrater Reliability of The Full Outline of Unresponsiveness Score and The Glasgow Coma Scale in Critically Ill PatientsDaniel Rivas VillarroelNo ratings yet

- PIIS1526590022004096Document14 pagesPIIS1526590022004096Martina SimangunsongNo ratings yet

- Sci1603 104Document27 pagesSci1603 104Roseanne BressanNo ratings yet

- Bell 'S Palsy: Clinical and Neurophysiologic Predictors of RecoveryDocument5 pagesBell 'S Palsy: Clinical and Neurophysiologic Predictors of RecoveryMarsya Yulinesia LoppiesNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0300957223007724Document11 pagesPi Is 0300957223007724sssvandestraat010No ratings yet

- Gross Motor Function Classification System: Impact and UtilityDocument6 pagesGross Motor Function Classification System: Impact and UtilityPatricia González SánchezNo ratings yet

- Effects of Not Intubating Non-Trauma Patients With Low Glasgow Coma Scale Scores A Retrospective StudyDocument8 pagesEffects of Not Intubating Non-Trauma Patients With Low Glasgow Coma Scale Scores A Retrospective Studyeditorial.boardNo ratings yet

- Validity and Reliability of The Novel Thyroid-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire, ThyproDocument7 pagesValidity and Reliability of The Novel Thyroid-Specific Quality of Life Questionnaire, ThyproPriyanaka NaraniyaNo ratings yet

- Cam4 10 1860Document12 pagesCam4 10 1860amirhhhhhhhhh8181No ratings yet

- Manual Therapy: Original ArticleDocument6 pagesManual Therapy: Original Articleubiktrash1492No ratings yet

- 10 1002@msc 1498Document13 pages10 1002@msc 1498Ricardo PietrobonNo ratings yet

- 1-s2.0-S0022399922000447-main (1)Document8 pages1-s2.0-S0022399922000447-main (1)David Villarreal-ZegarraNo ratings yet

- Sleep Duration-Quality Woth Health OutcomesDocument15 pagesSleep Duration-Quality Woth Health OutcomesRaúl Alexis Delgado EstradaNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Studies in The Contributions of The Work Environment To Ischaemic Heart Disease DevelopmentDocument8 pagesA Systematic Review of Studies in The Contributions of The Work Environment To Ischaemic Heart Disease DevelopmentKurnia Fitri AprillianaNo ratings yet

- Original Research Oral Research Presentations E19Document1 pageOriginal Research Oral Research Presentations E19Jaivant VassanNo ratings yet

- Predictive Utility of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy For The Outcomes of Hypoxic-Ischemic EncephalopathyDocument15 pagesPredictive Utility of Near-Infrared Spectroscopy For The Outcomes of Hypoxic-Ischemic EncephalopathyJulio CidNo ratings yet

- Chronic IntoxiationDocument10 pagesChronic IntoxiationStefhani GistaNo ratings yet

- Assessing Validity and Reliability of GL E3932ec1Document14 pagesAssessing Validity and Reliability of GL E3932ec1Gracia BarimanNo ratings yet

- Children 10 01862Document11 pagesChildren 10 01862Sinan Adnan Al-AbayechiNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review of The Psychometric Properties of The Boston Carpal Tunnel QuestionnaireDocument10 pagesSystematic Review of The Psychometric Properties of The Boston Carpal Tunnel QuestionnaireSirfandi NurNo ratings yet

- ResuscitationDocument10 pagesResuscitationrizki heriyadiNo ratings yet

- Prognostic Tools For ....Document15 pagesPrognostic Tools For ....I'am AjhaNo ratings yet

- Acl Rehab ProtocolDocument6 pagesAcl Rehab ProtocolPricy DevNo ratings yet

- Cancer 001 ConfiabilidadDocument9 pagesCancer 001 ConfiabilidadKARLA WONGNo ratings yet

- Vonpiekartz2020 PDFDocument18 pagesVonpiekartz2020 PDFKinjal SharmaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal 5Document9 pagesJurnal 5raraNo ratings yet

- 2024.02.28.24303514v1.full - Sleep Hygiene IndexDocument13 pages2024.02.28.24303514v1.full - Sleep Hygiene Index170211201076No ratings yet

- Jurnal PoneDocument21 pagesJurnal PoneTina HerreraNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review Protoco1Document7 pagesSystematic Review Protoco1Joiis PinoNo ratings yet

- Proactive Integrated Consultation Liaison PsychiatDocument12 pagesProactive Integrated Consultation Liaison PsychiatDragutin PetrićNo ratings yet

- Kozak 2015Document19 pagesKozak 2015ilham Maulana ArifNo ratings yet

- ImportantDocument15 pagesImportantanimut alebelNo ratings yet

- 1752 2897 4 7Document7 pages1752 2897 4 7ruba azfr-aliNo ratings yet

- Mendukung Simple SizeDocument7 pagesMendukung Simple SizeDevita ImasulyNo ratings yet

- Lee 2018Document7 pagesLee 2018Kings AndrewNo ratings yet

- Development and Validation of A Paediatric Long-Bone Fracture Classification. A Prospective Multicentre Study in 13 European Paediatric Trauma CentresDocument13 pagesDevelopment and Validation of A Paediatric Long-Bone Fracture Classification. A Prospective Multicentre Study in 13 European Paediatric Trauma CentresArul WidyaNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Sleep Quality and Related Factors in Stroke PatientsDocument8 pagesAssessment of Sleep Quality and Related Factors in Stroke PatientsajmrdNo ratings yet

- Jurnal TiwiDocument5 pagesJurnal Tiwisahrulagus366No ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0972978X23002064 Main 2 8Document7 pages1 s2.0 S0972978X23002064 Main 2 8Gonzalo ReitmannNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal DisordeDocument13 pagesPrevalence of Work-Related Musculoskeletal DisordeAmelia RahmahNo ratings yet

- Comparison Between FOUR Score and GCS in AssessingDocument8 pagesComparison Between FOUR Score and GCS in AssessingDaniela MosqueraNo ratings yet

- JCM 11 02308Document3 pagesJCM 11 02308Camila CorrêaNo ratings yet

- Sleep Duration and Depression Among AdultsDocument7 pagesSleep Duration and Depression Among AdultsGeorgiana PopescuNo ratings yet

- Instant download Lifespan development 7th, global Edition Denise Boyd pdf all chapterDocument66 pagesInstant download Lifespan development 7th, global Edition Denise Boyd pdf all chaptermantuleboney100% (10)

- Gta 5-LafdDocument4 pagesGta 5-Lafdkai.odonoghue9No ratings yet

- Ashwinikumar Medical Relief SocietyDocument2 pagesAshwinikumar Medical Relief Societyhitesh humaneNo ratings yet

- Risk Assessment Stainless Steel Equipments 00Document8 pagesRisk Assessment Stainless Steel Equipments 00emmz20No ratings yet

- ContraceptionDocument1 pageContraceptionSibel ErtuğrulNo ratings yet

- UCSP Reviewer LawDocument6 pagesUCSP Reviewer LawEJ RaveloNo ratings yet

- Letter Roof SpacesDocument1 pageLetter Roof Spacesrobert_hampson1No ratings yet

- WASH and Gender Technical Brief July 2020Document9 pagesWASH and Gender Technical Brief July 2020Paolo SordiniNo ratings yet

- Dukun Beranak: Indonesia's Birth WitchdoctorsDocument5 pagesDukun Beranak: Indonesia's Birth WitchdoctorsVerene Ysabell Litenia -No ratings yet

- Compilation of AnswersDocument4 pagesCompilation of AnswersShannon YapNo ratings yet

- Interviewing A Psycopathic SuspectDocument13 pagesInterviewing A Psycopathic SuspectJessica LopezNo ratings yet

- Grade 11 Finals: Get 1 Whole Sheet of PaperDocument25 pagesGrade 11 Finals: Get 1 Whole Sheet of PaperMethushellah AdolfoNo ratings yet

- Asthma Molecular and Drug DevelopmentDocument17 pagesAsthma Molecular and Drug DevelopmentTira MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Intradermal-Injections 2nd Semester 2022-2023!2!1Document35 pagesIntradermal-Injections 2nd Semester 2022-2023!2!1AinaB ManaloNo ratings yet

- Health Insurance Claim Inflation Report 20102016Document20 pagesHealth Insurance Claim Inflation Report 20102016Mayank AamseekNo ratings yet

- Prevention To Tackling MSDsDocument53 pagesPrevention To Tackling MSDssnuparichNo ratings yet

- Techniques and Benefits of Freestyle SwimmingDocument8 pagesTechniques and Benefits of Freestyle Swimmingjonna mae ranzaNo ratings yet

- Elysia MageTower PDFDocument11 pagesElysia MageTower PDFBruno Samuel Cunha De AbreuNo ratings yet

- CV of Christopher LibreaDocument6 pagesCV of Christopher LibreaChristopher Federico LibreaNo ratings yet

- Thesis - Final...Document45 pagesThesis - Final...Shaira Mae Reyes AbellareNo ratings yet

- Head and Neck NCPDocument2 pagesHead and Neck NCPAngelo AbiganiaNo ratings yet

- NCPDocument7 pagesNCPRuth MontebonNo ratings yet

- 2022 GPHR Workbook Module 6 PreviewDocument20 pages2022 GPHR Workbook Module 6 PreviewChandra GuptaNo ratings yet

- Intracavitory Brachy in Cervix: - The History and Systems To 2D PlanningDocument64 pagesIntracavitory Brachy in Cervix: - The History and Systems To 2D PlanningnitinNo ratings yet

- Women in The PhilippinesDocument8 pagesWomen in The PhilippinesChristian Nathaniel Ramon PalmaNo ratings yet

- Part 2 - Guidance For Palliative, Hospice and Bereavement Care For COVID-19 and Other Patients Facing Life-Threatening Illness in Hospitals (Updated)Document31 pagesPart 2 - Guidance For Palliative, Hospice and Bereavement Care For COVID-19 and Other Patients Facing Life-Threatening Illness in Hospitals (Updated)Louije Mombz100% (1)

- Case Study of ThalassemiaDocument9 pagesCase Study of ThalassemiaQaisrani Y9No ratings yet

- Office of The Sangguniang KabataanDocument4 pagesOffice of The Sangguniang KabataanReynan HorohoroNo ratings yet

- Rorschach Inkblot TestDocument2 pagesRorschach Inkblot TestBhaswati SahaNo ratings yet