Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Weste

Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Weste

Uploaded by

Pablo GuedesCopyright:

Available Formats

Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Weste

Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Weste

Uploaded by

Pablo GuedesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Weste

Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Weste

Uploaded by

Pablo GuedesCopyright:

Available Formats

C.

DOUGLAS RUSSELL

Freemasonry in

Academic Studies of

Western Esotericism

Part Two

DAVID HARRISON

The Masonic Engravings

by Pierre Lambert

de Lintot

Part Two

KENNETH JACK

Masonic Book Collecting

and Eureka Moments

JOHN BELTON

A Presentation

to Kenneth Jack

PHILALETHES

The Journal of Masonic

Research & Letters

Volume 75 • No- 2 Volume seVenty-fiVe • number two 45

Freemasonry in Academic Studies

of Western Esotericism

Part Two

C. Douglas Russell on the scholarly discussion of a key issue in Masonic studies

P

art one oF thIS StuDy begins by citing a published works on the esoteric, and Arthur Ver-

2002 paper by Brother Jay Kinney, exploring sluis, who has written several books emphasizing

the idea that Freemasons have a “love-hate theosophy.2 Versluis also founded an association

relationship” with the esoteric.1 As we proceed to for esoteric studies and was editor of the online

review writings by scholars of Western esotericism, journal Esoterica: The Journal of Hermetic Studies,

we find that they see Freemasonry as a significant with nine issues on esoteric topics.3

and influential aspect of esoteric traditions. The Another important author, Nicholas Go-

writings reviewed in Part One tend to emphasize odrick-Clarke (1953–2012), was Professor of West-

study of esotericism within the history of ideas: ern Esotericism at the University of Exeter and the

esotericism as a form of thought. Here we focus on third professor in the world to occupy a chair of

two other major approaches: esotericism as gnosis, esoteric studies, after Antoine Faivre and Wouter

and esotericism as dialectic. J. Hanegraaff. Goodrick-Clarke is author of The

There are many more respected academics Western Esoteric Traditions, A Historical Introduction

whose publications might well have been reviewed (2008) that Faivre describes as “a most valuable

here; but each deserves to have their views pre- presentation of the main Western esoteric cur-

sented in like detail, which is not possible in the rents, which keeps abreast with the current state of

limited space of this paper. The intention here is research.”4 We will proceed with some details from

simply to introduce a complex and multifaceted three more academics: (1) Wouter J. Hanegraaff,

literature. Among those who might have been for his emphasis on modern Western esotericism

included is Roger Dachez, who wrote the article as gnosis; (2) Kocku von Stuckrad, for presenting

“Freemasonry” in Hanegraaff’s Dictionary of Gnosis esotericism as discourse; and (3) Henrik Bogdan,

and Western Esotericism. There are also two Amer- for writing an entire book on Western esotericism

ican scholars: Jocelyn Godwin, with numerous and Freemasonry.

Wouter J. Hanegraaff is professor of History of

C. Douglas Russell, MPS, is a Former Master of Hermetic Philosophy and Related Currents at the

the Southern California Research Lodge. University of Amsterdam and editor of the Dictio-

Volume seVenty-fiVe • number two 51

C. Douglas Russell, mps

nary of Gnosis and Western Esotericism (2006).5 His at the site of the Temple. In the Holy Land, these

perspective on the history of modern (speculative) knights established contact with ancient sects

Freemasonry, expressed in numerous publications, that had “preserved the ancient secrets from the

6

is summarized here. By the late 1500s, a new kind Orient, including the supreme Pythagorean art

of organization developed in Scotland, through of geometry. After the dissolution of the Order in

transformation of medieval stonemasons’ guilds. 1307, surviving Templars were believed to have

This led to stonemasons’ lodges accepting “Gen- brought its secrets to Scotland, often considered

tlemen Masons” as members during the 1600s. In the homeland of Freemasonry.”10

a parallel development, from 1614 to 1616, three In the 1600s and early decades of the 1700s,

Rosicrucian Manifestos were published that had “Freemasons were widely perceived as Rosi-

a huge impact across Europe over many decades. crucians and practitioners of alchemy; and the

Legend has it that the Rosicrucians were a myste- brotherhood attracted much curiosity because

rious brotherhood based on occult sciences that of suspicions that it might have preserved the

their founder had learned through travels in the mysterious secrets of antiquity, including that of

Middle East. Whether this brotherhood ever ex- the philosophers’ stone.”11 In England, after the

isted other than as a literary movement, the idea formation of the Premier Grand Lodge in 1717, Ma-

behind it is a powerful one—that of a secret orga- sonry “distanced itself from such esoteric pursuits

nization preserving and transmitting wisdom “that as it developed into an essentially rationalist and

would transform European culture along the lines humanitarian movement.”12 On the Continent,

of the ancient Hermetic and related sciences.”7 especially in France, esoteric pursuits including

Before the 1600s, there were no formal orga- alchemy, hermeticism and theosophy were flour-

nizations like that of the mythical Rosicrucians; ishing in the higher Masonic grades beyond the

however, there was a long-standing belief “that first three degrees, attracting new members with

ancient wisdom or the secrets of nature had been interests in the ancient mysteries. After 1750, with

transmitted and kept alive by wise men through increasing separation of church and state, many

the ages”—a belief that “belongs to the central new religious or initiatic organizations came into

8

tenets of Western esotericism.” Antoine Faivre has existence that called themselves Rosicrucians—

referred to this tenet, or esoteric current, as “the most of them inspired by models derived from

9

perennial philosophy or primordial Tradition.” Freemasonry.13

Paralleling this current, medieval stonemasons Hanegraaff’s views on the history of Western

had created an historical pedigree that extended at esotericism will be summarized next, beginning

least as far back as Noah and his sons, who trans- with his perspective on the 1600s to 1700s—the

mitted knowledge of geometry and architecture era of the late Renaissance and the Enlighten-

to humankind after the great flood. The masons’ ment—when modern Freemasonry was taking

interest in architecture—particularly Solomon’s shape. He explains that studies of Western eso-

Temple—was reflected in speculative historical lin- tericism have progressed beyond Frances Yates’

eages of their craft, connecting them to the Knights thesis that esoteric traditions of centuries past

Templar, whose headquarters were in Jerusalem stood in opposition to Christianity and rationalism.

52 philalethes • The Journal of Masonic Research & Letters

Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Western Esotericism

An example is that the term “Gnosticism” was relationship between the Enlightenment and

coined as a degrading or critical term in the 1600s, phenomena such as Freemasonry and related

used by some Christian factions “to cement their associations . . . the clearer it becomes that the

own identity as ‘true’ Christians by construing a boundaries between reason and its “other” were

14

negative other.” However, Western esotericism in fact blurred and shifting, with many important

before the Enlightenment was not a countertradi- figures finding themselves with one foot in each

tion to Christianity. It was “a neglected dimension camp.20

of Christian culture”; thus, historians have been

“discovering that Christian culture as such is a far Hanegraaff’s thoughts about these complexi-

more complex phenomenon than one might infer ties of history led to his defining what we now call

from traditional church histories (based on simple “Western esotericism” as a domain of knowledge

15

church-sect or orthodoxy-heresy oppositions).” rejected by the mainstream religious and intellec-

Hanegraaff warns against the view that the En- tual culture that evolved during the 1600s and

lightenment, or Age of Reason, was an era charac- 1700s. The esoteric was not simply “a random

16

terized by “religion versus science” propositions. collection of discarded materials . . . [because] a

For a proper historical view of the 1700s, “it is broad consensus had emerged around the [1700s]

simplistic to imagine a movement of ‘esotericists’ about the chief characteristics of the rejected do-

pitted against the defenders of ‘reason.’ . . . the key main.21 . . . The category of ‘rejected knowledge’

term is historical complexity; . . . the study of West- that emerged during the Enlightenment, and

ern esotericism challenges the simplicity of grand that we have inherited, is the final outcome of

17

narratives of modernity and secular progress.” complicated apologetic and polemical debates

This notion of complexity applies to hermeticism, dominated by Christian intellectuals from antiq-

which was not limited to a magical subculture but uity to the [1700s].”22 Even so, “religion in Europe

was “abundantly present in ‘mainstream’ religious, has always been marked by religious diversity

philosophical and scientific discourse . . . and its and pluralistic competition. [ . . . ] Next to Chris-

great representatives were complex thinkers tianity and its various denominations, Judaism

whose perspective can by no means be reduced and Islam should be seen as integral parts of the

18

to hermeticism and magic alone.” For example, story of religion in Europe, and the same goes for

Giordano Bruno’s voluminous and influential the various ‘pagan’ traditions from antiquity and

writings show that he was very interested in both indigenous European cultures that continue to

hermeticism and “questions of strict philosophy exert an important influence in learned discourse

19

of science.” Similarly, not all proponents of the and popular practice.”23

Enlightenment based their identity on “construing Hanegraaff has made highly significant con-

a negative other” by rejecting esoteric currents as tributions by presenting in-depth research on

superstition and unreason. developments in Western esotericism all the way

through the 1900s and into the 2000s. He is among

Careful historical research reveals a much more those who have provided a course correction for

complex picture. The more we learn about the scholarly studies that he explains thus:

Volume seVenty-fiVe • number two 53

C. Douglas Russell, mps

Academic research [on esotericism] . . . has been and a superior spirituality.”28 Hanegraaff describes

most seriously neglected by earlier generations modern Theosophy as “the most influential esoter-

(mostly due to the influence of the now discred- ic movement of the [1800s].”29 He notes that some

ited “secularization thesis” according to which adherents considered this theosophy a revival of

these domains could not be anything more than ancient wisdom, but

marginal “survivals” that would eventually suc-

cumb to the pressures of rationalization and sec- it was a radically new synthesis grounded in con-

24

ularization). cerns that are typical of the [1800s]. Not least by

adopting and integrating terms and concepts

Far from being marginal, esotericism has from Indian religions that had never been a part

survived, and evolves into new forms over time, of Western esotericism before—the notion of

because it “is continually reinterpreted in the light karma is a particularly clear example—Theoso-

25

of new social and cultural circumstances.” phy became a force of religious innovation that

Another example of esotericism taking new created essential foundations for much of twen-

forms is seen in the history of theosophy. The tieth-century esotericism.30

word “theosophy” was used in many ways by the

ancients with the overall significance being a ref- Hanegraaff’s scholarly approach is well repre-

erence to the “Wisdom of God,” or the “science of sented in his New Age Religion and Western Culture,

26

divine things.” A version of it was formulated and Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought (1998).

practiced by Jacob Böhme (1575–1624) in Germa- He provides a similar but simplified presentation in

ny, and is considered foundational for the major Western Esotericism, A Guide for the Perplexed (2013),

Western esoteric current known as “Christian where one chapter is titled “Practice”—devoted to

theosophy.” The social and cultural circumstanc- the experiential side of the esoteric. It is a welcome

es of Böhme reflected in his writings include his contrast to the many scholarly writings that focus

being influenced by Protestant Christianity and by on esotericism within the history of ideas. Here we

works of the Swiss physician and alchemist Para- see Western esotericism as gnosis, with sections

celsus (c. 1493–1541). Böhme’s work evolved into commenting on Freemasonry. One section, “Initi-

new forms. It inspired the formation of spiritual atic Societies,” includes a “recommended reading”

communities in the 1600s, and influenced authors list of works by prominent scholars of Masonry.31

who proceeded to take it in new directions. In the Hanegraaff has offered this perspective on gnosis:

late 1700s, a network of Christian theosophers was “It was prominent in the very currents of late antiq-

inspired in part by German Idealist philosophy and uity . . . and it emphasizes the conviction that true

by contemporary German physician Franz Mesmer and fully convincing ‘knowledge’ of divine things

27

(1734–1815). In the late 1800s, modern Theosophy can be attained not by means of reasoning, the

was formulated in the works of Helena P. Blavatsky, senses, or revealed scriptures, but only by gaining

reflecting developments in that century, including direct, experiential access to the higher spiritual

the comparative study of religions, and the great realities themselves.”32

influence of India “as a home of ancient wisdom In this attempt to summarize Hanegraaff’s

54 philalethes • The Journal of Masonic Research & Letters

Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Western Esotericism

views, their breadth and complexity become ob- (1856–1939); the other by Swiss psychiatrist Carl

vious, and a great deal has been left out or simpli- Jung (1875–1961). Freud’s psychoanalysis points

fied. Let us close with two key aspects of his take toward the “psychologization of the sacred,”

on contemporary esoteric spirituality. One is the wherein “spiritual realities may be no more than

idea that, from the 1900s into the 2000s, we have psychological projections of our own hopes and

been living in a time of “the religious supermar- wishes.”36 Jung’s analytical psychology is more

ket,” which is to say that there is a great variety of about “‘numinous’ energies of the collective un-

spiritual practices for each of us to choose from. conscious . . . seen as mysterious forces somehow

Before the separation of church and state, esoteric more primary and original than the products of

spiritualities were necessarily grounded in a spe- human reflection. [ . . . ] This means that the sa-

cific religion. In modern secular societies, these cralization of the psyche trumps the reductionist

spiritualities can be independent of any organized trends of psychologizing the sacred mostly asso-

religion, and can even take “entirely individual ciated with Freud.”37 This openness to esoteric

forms [of a mixture of beliefs and practices] . . . realms beyond the mind, to which the mind has

33

without any organizational structure at all.” access, led to Jungian psychology becoming “one of

While there are “esoteric religions,” i.e., organi- the most important influences on how esotericism

zations based on a specific set of esoteric ideas, has developed after World War II.”38

there are also “esoteric spiritualities [which are] According to Hanegraaff, developments in

individual mixtures of esoteric and other elements contemporary psychology since the mid–1900s

that are fine-tuned, so to speak, to the personal have been strongly influenced by Carl Jung’s work.

34

needs and interests of the religious consumer.” While Freud’s psychoanalysis addressed issues

A second key aspect of contemporary eso- around mental illness and dysfunctional behavior,

tericism is Hanegraaff’s view that it is greatly in- Jung’s analytical psychology inspired the develop-

fluenced by psychology. We might well say that ment of transpersonal psychology that addresses

psychology is a contemporary form of modern issues of mentally healthy individuals, such as life

Western esotericism. After all, it is the study of crises around loss, change and growth; and the

the psyche or soul—the esoteric or inner life of psychology of creativity, genius, and spirituality.

humans. Historical developments from the 1800s According to Hanegraaff, in the transpersonal

into the mid–1900s—many of them in the modern movement, American philosopher Ken Wilber “is

science of psychology—led to great questioning regarded as the foremost theoretician . . . . [Wilber

about “the human mind and its relation to God sees the] different Western psychological schools

or the supernatural. That human beings have an are not mutually exclusive but complementary.

inborn capacity of knowing the divine is a core They address different levels of consciousness.”39

belief in Western esotericism.”35 However, is the Hanegraaff has provided considerable detail on

fundamental reality God, or is it the human soul, Wilber’s work, noting its connections to two prom-

or mind? Opposite answers to this question come inent esoteric currents, neoplatonism and the

from two very influential schools of thought —one perennial philosophy.

founded by Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud We turn now to the work of Kocku von Stuck-

Volume seVenty-fiVe • number two 55

C. Douglas Russell, mps

rad, Professor of Religious Studies at the University rhetoric of a hidden truth, which can be unveiled

of Groningen, Netherlands. By contrast with the in a specific way and established contrary to other

scholars who focus on the esoteric as a form of interpretations of the universe and history—often

thought or the esoteric as gnosis, Stuckrad em- that of the institutionalized majority.”42

phasizes the esoteric as discourse. He has written Discourse in religion could take the form of

a comprehensive introduction to our topic in West- dialogue or debate—for example, among Catholic

40

ern Esotericism, A History of Secret Knowledge. scholars, between Catholics and Protestants, or

between Christians and Jews. It could also be ex-

Whenever I talk about ‘esotericism’ in this book, changes between proponents of the exoteric and

I conceive of the esoteric . . . as an element of dis- the esoteric aspects of a tradition; for example, in

course in the European history of religion. This Christianity, between orthodox clergy and Chris-

element of discourse can be identified as follows: tian theosophists. It is through such social inter-

The pivotal point of all esoteric traditions are actions that individuals and institutions define

claims to ‘real’ or absolute knowledge and the themselves. This process also involves “othering”:

means of making this knowledge available. This for example, “I am not a Muslim.” Thus, religious

might be through an individual ascent as in Gnos- identities have formed through discourse, often

tic or Neoplatonic texts, or through an initiatory with a sense of belonging to a particular religious

event as in secret societies of the modern period, tradition. “The concept of tradition plays a signifi-

or through communication with spiritual beings, cant role in discourses of European identity. . . . The

th

as in the ‘channeling’ of the 20 century. [. . . S]uch idea of a coherent line of philosophical and reli-

means of acquiring knowledge can also be found gious tradition that comprised doctrines stemming

41

in scientific contexts. from the scriptural religions had been present in

European culture from late antiquity onwards.”43

Discourse, then, involves acquiring knowledge From the perspective of esoteric discourse, it

and communicating about it—through speaking becomes apparent that religious identity is not a

and writing. “Real or absolute knowledge” is ac- simple matter. Studies of Western esotericism have

quired in various ways. For a gnostic it might come debunked the narrative of a “monolithic Christian

through meditation; for a member of a religious Occident.”44 “Religious pluralism and the existence

group, through faith; for a scientist, through ob- of alternatives are the normal case, rather than the

servation, analysis and reasoning. Discourse is exception in Western history of culture.”45 The

polemical; that is, it is not simple dialogue but Western world has seen three scriptural religions

an exchange that is contentious or combative. with claims of tradition: Judaism, Christianity

Engaging in discourse involves taking a position. and Islam. “Far from being isolated social groups,

It could involve expressing a point of view (“this [these] religions interacted on several levels in a

is what I believe”), presenting a narrative (“this pluralistic religious world.”46 In addition, there

is my story, this is our history,”) or it could be ad- were a number of influential esoteric historical

vocating for a particular way of interpreting the currents in the mix. Among them were prisca

world. “What makes a discourse esoteric is the theologia (“first theology”) or philosophia perennis

56 philalethes • The Journal of Masonic Research & Letters

Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Western Esotericism

(“eternal philosophy,” the “perennial philosophy”) his identity as a Christian Kabbalist. “What we see

that influenced religious discourses in the 1300s. in the intense exchange of thoughts and positions

between Pico and other Christian Kabbalists on

Prisca theologia and the notion of a superior tra- the one hand and their Jewish contemporaries on

dition shaped identities that formulated genealo- the other, is exactly this shared passion for certain

gies of knowledge which [go beyond the bounds models of interpretation that fostered religious and

of] the revelation of Jewish or Christian tradi- philosophical identities. It was the discourse of the

tion. Usually connected to authorities that are day. [ . . . T] he driving force behind this exchange

potentially older than Moses that stood outside was not dialogue but polemical dissociation and

the biblical revelation—Hermes Trismegistus, competition.”51

Zoroaster, Pythagoras, Orpheus, Plato, etc.—this Stuckrad’s perspectives on tradition, identity

invented tradition played a crucial role in the and interpretation challenge some ideas about

inter-religious and intra-religious debates of sub- historical periods and what it means to be modern.

47

sequent centuries. For example, he has concluded that:

In the context of discourse, we see that tra- the image of the Middle Ages as an era of brutal vi-

ditions are “quite different from history,” as they olence and the lack of science and enlightenment

are “claimed in a situation of competition. [ . . . ] is a misleading oversimplification. . . . The char-

Like identities, traditions are negotiated in the acterization of the Renaissance as the birth period

48

complex process of cultural exchange.” Religious of enlightened modernity is today more doubtful

and cultural pluralism has implications for indi- than ever. On closer investigation, many of the

vidual as well as group identities. Historians have revolutions between the [1400s] and [1600s] turn

challenged the idea of “one person, one religion,” out to be a continuation of medieval thought. 52

viewing it as “singularization.”49 “Large parts of the

European population had no clue what the Chris- Additionally, Stuckrad questions narratives

tian doctrine really meant, let alone were able to about how technological advances, particularly

translate this doctrine into their everyday life; they the printing press, have shaped the modern world.

could not follow the Latin services and adhered to

a variety of non-Christian beliefs at home.”50 Some In a dialectic between hiding and revealing

Christian thinkers had considerable interest in primordial knowledge, the role of the printing

pagan philosophers, including Aristotle and Plato, press should not be underestimated. . . . esoteric

but interpreted them in light of Christian teach- treatises [were disseminated] even more widely

ings. Similarly, in the late 1400s, priest and scholar than new scientific treatises [which] fostered a

Pico della Mirandola studied Kabbalah, because he new trend in “arcanization.” Thus, “one should

was intrigued by it as a “model of interpretation” not think only about new forms of enlighten-

that linked language, magic and creation. His in- ment when considering the effects of printing

teractions with his Jewish contemporaries did not on scholarship. New forms of mystification were

serve to reconcile the religions, but rather affirmed encouraged as well.” 53

Volume seVenty-fiVe • number two 57

C. Douglas Russell, mps

In modernity, we see discourses between such “despite its emphasis on tradition, transmission

fields as “religion and science, religion and art, or and authority, Freemasonry has always been a

religion and Hermeticism. These fields serve as non-dogmatic organisation in the sense that its

examples of important ‘locations of knowledge’ rituals, symbols and practices have not had official

54

and the formation of European identities.” A and final interpretations.”58

close examination of such discourse challenges the Sometimes proponents of esoteric versus ex-

narrative that we live in an age of secularization, oteric interpretations of Masonry have engaged in

in which esoteric traditions are what Hanegraaff critical discourse and “othering”—advocating for

called “rejected knowledge.” In this light, Stuck- their perspectives in a contentious way in which

rad argues “that the narratives that Europeans each side portrays a “negative other.” The idea

construct about themselves are simplifications of Freemasons having a “love-hate relationship”

55

that are worthy of reassessment.” with the esoteric then takes the form of division

In light of studies by scholars of Western es- and conflict between brothers with apparently

otericism, the narratives that some Freemasons opposing views. This aspect of our Craft has a

have constructed about aspects of Masonry might long history, and includes a large group of Masons

also be seen as simplifications. One such narrative forming a Grand Lodge of “ancients” in England in

suggests that modern Masonry is largely secular—a the mid–1700s, in opposition to the grand lodge

reflection of values of the Enlightenment; that formed in 1717 whose members were designated

Masonry has little of the esoteric in it. However, the “moderns.” A similar division was seen on

according to Stuckrad, “the traditions of Freema- the continent (in Germany) as noted by Stuck-

sonry have been a significant factor in the institu- rad. “In 1782 at the international Wilhelmsbad

tionalization of esotericism over the past 300 years. Convention attempts were made to establish a

One must speak of traditions in the plural, for no new binding constitution, but unity could not be

56

single type of Freemasonry actually exists.” achieved owing to the gulf between lodges guided

In the context of the present paper, two major by Enlightenment values and Rosicrucian lodges

types of Freemasonry could be characterized as interested in alchemy and esotericism.”59

esoteric and exoteric—each having its own inter- Stuckrad acknowledges that, in the second

pretations and practices. Proponents of these two half of the 1700s, many Masons supported the

viewpoints have sometimes spoken and written ideals of the French Revolution, and engaged in

about their views in a spirit of dialogue. That in- the political struggle against the absolutist state

volves honoring Masonic principles: the principle for human rights. Although most lodges did not

of equality—“meeting on the level”; and the prin- take positions officially in matters of religion and

ciple of toleration—accepting diversity and main- politics, they were influential in Enlightenment

taining harmony. It also aligns with an idea about societies, fostering ideals of universal education,

interpretation often seen in Masonic writings. For tolerance and human progress.

example, “As no individual has the right to speak

for Freemasonry as a whole, no interpretation can Once adopted by the educated elite, the craft

57

possibly be authoritative.” Another version is: motif of the dressed stone became a symbol for

58 philalethes • The Journal of Masonic Research & Letters

Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Western Esotericism

the education of the new human being, while the tos published early in that century, “the idea of

lodge hierarchy of novice, apprentice and mas- secret or closed societies that were considered to

ter represented degrees of individual progress. be guardians of an esoteric doctrine, was firmly

The esoteric aspect of these ideals concerned embedded in Western culture.63

the “higher knowledge” frequently sought by

Enlightenment societies. The esoteric motif is also The Rosicrucian manifestos caused a great in-

obvious in the idea, often expressed in alchemical terest in this mythical fraternity, and as a result,

symbolism, of transforming and refining the a boom of secret and closed societies emerged.

60

individual into a perfect human being. Most of these societies worked out systems of

initiation, which transmitted the esoteric form

Freemasonry also served as a model for vari- of thought through symbols and allegories. The

ous initiatic orders that were forming by the late rituals of initiation that were employed are the

1700s. Among them were the Rosicrucians, who focus of the present study.64

built a degree system starting with versions of the

first three degrees of Masonry. “The Rosicrucian Bogdan’s book has a chapter on the three Craft

groups and ‘irregular’ high-degree masonry, in the degrees of Masonry, another on the high degrees,

sense of ‘unaccepted’ by the English Grand Lodge, and others on The Hermetic Order of the Golden

created a basis for the secret societies and magical Dawn, and “the first Western esoteric initiatory

orders of the [1800s], which are so important in New Religious Movement in the true sense of the

61

the history of modern esotericism.” word, Gerald Gardner’s witchcraft movement of

We will offer in conclusion some highlights of the 1950s.”65

the work of Henrik Bogdan, Associate Professor Our focus here is the chapter on the Craft

of Religious Studies at University of Gothenburg degrees of Masonry, in part because “the Craft

in Sweden. He is author of Western Esotericism rituals of Freemasonry [are] the blueprints, as it

and Rituals of Initiation (2007). In 2007, there were were, of all later masonic rituals of initiation.”66

few scholarly works on Western initiation rituals. Bogdan addresses the importance of Anderson’s

Bogdan focuses on exploring “the relationship of Constitutions and the Old Charges in the history of

Western esotericism and masonic ritual texts,” and Freemasonry. Referencing the Old Charges points

62

places them in historical context. He considers to an “historical link between the medieval oper-

“masonic ritual texts” to be those within Free- ative masons and the later nonoperative masons.

masonry, and others with structural components [ . . . ] And most important [for Bogdan’s study of

derived from Freemasonry. Bogdan chose texts ritual], the Old Charges are crucial to our under-

written in various historical periods, from 1697 standing of Masonic rituals of initiation as they

through the 1950s, to study trends in develop- contain the earliest references to the admission

ment of “Western esoteric rituals of initiation.” He procedures that later developed into this particular

discusses the influence of Rosicrucianism. There type of rituals.”67

was probably no Rosicrucian organization in the In presenting a mythical history of Freema-

1600s; however, due to the Rosicrucian manifes- sonry based on the Old Charges, James Anderson

Volume seVenty-fiVe • number two 59

C. Douglas Russell, mps

probably intended to glorify the Craft by giving such as Long Livers (1722) by Bro. Robert Samber,

68

it a past suggesting that it is important. This that includes references to Rosicrucianism, al-

was done in part by presenting a list of greatly chemy, astrology, and Neoplatonism.75 Bogdan’s

respected sages who passed down the teachings speculation is that “the masonic initiation could

of geometry and masonry through the genera- have been interpreted as the alchemical idea of

tions: Adam, Noah, Moses, Solomon, Pythagoras, transmutation, which often implied a spiritual

Vitruvius, and others. This Masonic mythistory refinement of the alchemist himself.”76

“has clear similarities with that connected to the As to the third or Master Mason degree, it

69

Renaissance philosophia perennis.” The perennial had been introduced into the Craft no later than

philosophy is an esoteric historical current “seen as the mid–1720s. There are several indications of

a ‘true philosophy’ that was transmitted through esoteric interests in Freemasonry from documents

a chain of initiates”: Enoch, Noah, Moses, Hermes generated during this period. In A Letter to the

70

Trismegistus, Pythagoras, Plato, and others. The Grand Mistress (1724), “masonry is virtually iden-

legendary history of Freemasonry echoes this tified as kabbalah.”77 The author suggests that the

current by pointing to “a secret tradition that has quintessence of Masonry can be found by under-

71

been handed down through the ages.” standing the works of the medieval cleric Ramón

Bogdan also sees Freemasonry being inspired Lull, who was believed to be an alchemist, and

by elements of Rosicrucianism, which, by 1629, well known for his interest in kabbalah and the

was seen not as an actual organization but as a esoteric art of memory. In The Grand Mystery Laid

“spiritual brotherhood”—a “Company of Spiritual Open (1726), we find “the first explicit references

Builders.” This parallels the idea of masons being in Masonic catechisms to not only kabbalah, but

72

builders of a new, spiritual temple. Solomon’s also to Western esotericism in general.”78

Temple became the model for that spiritual edifice, Bogdan notes that an early version of the

and by 1696 was an important part of Masonic Hiramic legend appears in an Old Charges doc-

ritual. Over the next three decades it became “one ument, the Graham mS, in 1726, with Noah as

of the most important characteristics of the Craft the central character. In 1730, Prichard’s Masonry

rituals, especially with the emergence of the third Dissected presented text of all three degrees and

degree from 1730 onward. The building site of Sol- included the legend with Hiram as the central

omon’s Temple becomes the mythological scene character. It was popular among Masons, and

73

of the rituals.” “is the perhaps most influential of all Masonic

Bogdan argues that, while it is often assumed exposures published in the [1700s].” 79

that Western esotericism entered Freemasonry by There was a “peculiar mysticism” connected

the mid–1700s from various systems of Masonic to the development of the Masonic third degree. It

high degrees, in fact, “as early as the first half of the was clearly influenced by the “Cabalistical” esoteric

[1600s], masonry was often perceived of as linked current. In Masonry Dissected, Prichard “seems to

74

to what we today call Western esotericism.” He imply that the old form of masonry needed to be

gives examples from non-Masonic sources as well ‘repair’d by some occult mystery,’ or would soon

as examples in the writings of Masons themselves, be annihilated.”80 Bogdan writes, “It is tempting

60 philalethes • The Journal of Masonic Research & Letters

Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Western Esotericism

to interpret the ‘occult mystery’ as the legend of that this includes esoteric rituals of initiation as

81

Hiram.” As to the quest for the lost word in that well, are essentially interpretative. It is through

legend, Masonic scholar A.E. Waite (1847–1942) an act of interpretation of the experience of the

had related it to a similar quest found in the kab- ritual, and the ritual as such, that the ritual of ini-

balist tradition. Research by contemporary scholar tiation becomes an initiation in the strict sense

82

Jan A.M. Snoek tends to confirm Waite’s view. of the word. The interaction of experience and

Snoek also sees the original version of the interpretation is essential to the understanding

Hiram legend as an “initiation myth” that in later of rituals of initiation. Without the experience

83

versions became a “moralistic story.” In the early there is nothing but meaningless symbols for the

version, the name of God was placed on the tomb esotericist to interpret, and without the interpre-

of Hiram, tation the experience fails to become initiatic.87

a functional equivalent to his being buried in the In his article on Masonry’s “love-hate rela-

Sanctum Sanctorum. . . . which renders the third tionship” with the esoteric, Jay Kinney suggests

degree ritual an initiation of a very well-known an interpretation that is both psychological and

kind: the candidate is identified with the hero, spiritual:

who turns out to be (a) God. In that way, the ritual

Unio Mystica [or Mystical Union] between the can- Through our initiations, every Master Mason

84

didate and the divinity is expressed and realized. becomes symbolically in charge of building his

own inner temple—“that house not made with

At the core of the Jewish Kabbalah lies the fun- hands”— in which to hold the “holy of holies,”

damental aim of the individual experience of symbolized by the Ark of the Covenant in the

the Godhead, or a Unio Mystica. . . . the [early] inner chamber of Solomon’s Temple. There are

Master degree initiation . . . aimed at the same many ways to look at this inner temple: as one’s

85

goal found in Kabbalah. higher self; one’s spirit; one’s connection to God;

as the spark of the divine within, that we have

These highlights of Bogdan’s book empha- the opportunity to fan into a warm and light-im-

size the influence of esoteric historical currents— parting flame. This isn’t a sectarian religious

Western esotericism as a form of thought. He matter—it is a broad spiritual and psychological

does discuss gnosis at some length, as a feature symbol system that has the potential to speak to

of many rituals of initiation—“the experiential everyone.88

aspect of esotericism,” wherein “the revelatory

form of knowledge” is transmitted to a candidate.86 Brother Kinney lists esoteric currents of in-

Bogdan agrees that initiation is transformative: terest to Masons that are addressed by the above

authors: Kabbalah, Rosicrucianism, Hermeticism

but it is not so much the experience as the inter- and Alchemy. He does not mention theosophy—a

pretation of it that has a transmutative effect upon prominent esoteric current in the writings of aca-

the initiate. Esoteric discourses, and I suggest demics.89 Kinney does include “Sacred Geometry

Volume seVenty-fiVe • number two 61

C. Douglas Russell, mps

2013), 33–36.

and Sacred Architecture” in his short list of “eso- 7 Ibid., 34.

teric traditions,” while the academics sometimes 8 Ibid., 33.

allude to sacred geometry and architecture without 9 Faivre discusses a primordial tradition and “The Pe-

rennialist Current” in Western Esotericism, 3–5, 98–100.

naming them as specific “currents.”90 According

10 Hanegraaff, Western Esotericism, 36.

to Kinney, one Masonic author used the term, 11 Ibid., 35.

“lunatic fringe” when referring to Masons with es- 12 Ibid.

oteric interests. Kinney says it is risky to thus label 13 This paragraph paraphrases Hanegraaff, Western

those who “see connections or parallels between Esotericism, 34–35.

14 Hanegraaff, Dictionary, “Introduction,” vii.

Masonry and the Ancient Mysteries, the great

15 Wouter J. Hanegraaff, “Beyond the Yates Paradigm,

myths, and esoteric traditions.”91 He argues that The Study of Western Esotericism between Coun-

some notable Masons have held esoteric beliefs, terculture and New Complexity,” in Aries, Vol.1. no.

and it is important to acknowledge this, and not 1, 2001, 30. Hanegraaff was Editor in Chief of Aries

from 2001-2010.

deny our history.92 Besides, criticism of esoterical-

16 Hanegraaff, Dictionary, viii.

ly-minded brothers could discourage them from 17 Hanegraaff, “Beyond the Yates Paradigm,” 30.

digging deeper into Masonic myths and symbols. 18 Hanegraaff, Dictionary, x.

A good strategy for Masons facing such criticism 19 Hanegraaff, “Beyond the Yates Paradigm, 16.

20 Hanegraaff, Dictionary, x.

is “to arm themselves with a realistic assessment

21 Hanegraaff, Western Esotericism, 13.

of Masonry’s relationship to the esoteric.”93 22 Ibid., 15. The italics are Hanegraaff’s.

23 Ibid.

Notes 24 Hanegraaff, Dictionary, xii.

1 Jay Kinney, “Is Freemasonry Afraid of Its Own Shad- 25 Wouter J. Hanegraaff, New Age Religion and Western

ow? Masonry’s Love/Hate Relationship with Esoteric Culture (New York: State University of New York Press,

Traditions,” in Heredom: The Transactions of the Scottish 1998), 407.

Rite Research Society 10 (2003), 139–53. 26 Antoine Faivre, Theosophy, Imagination, Tradition,

2 In Western Esotericism, Antoine Faivre (p. 113) lists Studies in Western Esotericism (Albany, N.Y.: State

Jocelyn Godwin, The Theosophical Enlightenment (Al- University of New York Press, 2000), 4.

bany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press, 1994), 27 Hanegraaff, Western Esotericism, 32–33.

describing it as a “fundamental work for what con- 28 Ibid., 130.

cerns certain major representatives of the Western 29 Ibid.

esoteric currents, notably of the [1700s and 1800s].” 30 Ibid., 130–31.

3 Information on the journal is available here: http:// 31 Ibid., 174.

www.esoteric.msu.edu. A comprehensive presentation 32 Wouter J. Hanegraaff, “Teaching Experiential Dimen-

of theosophy is in Arthur Versluis, Wisdom’s Children, sions of Western Esotericism,” in William B. Parsons,

A Christian Esoteric Tradition (Albany, N.Y.: State Uni- ed., Teaching Mysticism (Oxford University Press, 2011),

versity of New York Press, 1999). an uncorrected proof p. 158, accessed 2/27/2022 at

4 Antoine Faivre, Western Esotericism: A Concise History https://www.academia.edu/3461756/Teaching_Expe-

(New York: State University of New York Press, 2010, riential_Dimensions_of_Western_Esotericism_2011_

originally published as L’Ésotérisme in 1992), 113. 33 Hanegraaff, Western Esotericism, 140.

5 Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Ed., Dictionary of Gnosis and 34 Ibid., 141.

Western Esotericism (Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, 2006). 35 Ibid., 135.

6 For details, see Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Western Esoter- 36 Ibid., 136.

icism, A Guide for the Perplexed (London: Bloomsbury, 37 Ibid., 138.

62 philalethes • The Journal of Masonic Research & Letters

Freemasonry in Academic Studies of Western Esotericism

38 Ibid., 137–38. 74 Ibid., 70.

39 Hanegraaff, New Age Religion, 58–59. 75 Ibid., 74–75. Here, Bogdan discusses references to Ros-

40 Kocku von Stuckrad, Western Esotericism: A History icrucianism and alchemy in Long Livers. Additional

of Secret Knowledge (London: Equinox, 2005, first references are noted in endnote 35, page 188. Samber

edition in German, 2004). There is a brief section on wrote under the pseudonym “Eugenius Philalethes.”

Freemasonry (pages 116–18). 76 Ibid., 76.

41 Ibid., 10. 77 Ibid., 84.

42 Ibid. 78 Ibid.

43 Kocku von Stuckrad, Locations of Knowledge in Medieval 79 Ibid., 85.

and Early Modern Europe, Esoteric Discourse and Western 80 Ibid., 86.

Identities (Boston: Brill, 2010), 25. 81 Ibid.

44 Ibid., 4. 45 Ibid., 22. 82 Bogdan presents A.E. Waite’s ideas on pp. 90–91, and

46 Ibid., 27. 47 Ibid., 25–26. proceeds to discuss Snoek’s view, using a quote cited

48 Ibid., 41. 49 Ibid., 15. here in endnote 84.

50 Ibid., 13. 51 Ibid., 69. 83 Bogdan, Western Esotericism, 92.

52 Ibid., 133. 84 Ibid. This is a quote taken by Bogdan from J.A.M.

53 Ibid., 134. Stuckrad is summarizing and quoting from Snoek, “The Evolution of the Hiramic Legend from

Elizabeth L. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent Pritchard’s Masonry Dissected to the Emulation Ritual,

of Change (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, in England and France” in Aries No. spécial (1999), 79.

1979), 77. 85 Bogdan, Western Esotericism, 92–93.

54 Ibid., 137. 86 Ibid., 22.

55 Ibid., 138. 87 Ibid., 47–48. The italics are Bogdan’s.

56 Stuckrad, Western Esotericism, 116. 88 Kinney, 149.

57 Carl H. Claudy, ”The Doctrine of Freemasonry,” The 89 Antoine Faivre’s 2010 bibliography mentions the work

Short Talk Bulletins II, Vol. 22, No. 1, January, 1944. of three American scholars who have explored the

(Burtonsville, Md.: The Masonic Service Association, theosophical esoteric current. In addition to Jocelyn

2014), S. Brent Morris, Ed., 309.] Godwin and Arthur Versluis, cited earlier (notes 2 & 3),

58 Henrik Bogdan and Jan Snoek, Eds., “Chapter 1, In- Faivre lists James A. Santucci, editor of the quarterly

troduction,” Handbook of Freemasonry (Leiden, The journal, Theosophical History. See www.theohistory.org.

Netherlands: Koninkligke Brill, 2014), 1. 90 Kinney, 140. One author briefly discussed in the pres-

59 Stuckrad, Western Esotericism, 118. ent paper does name sacred geometry among the

60 Ibid., 117. esoteric historical currents (in Part One, p. 17): Glenn

61 Ibid., 118. Alexander Magee, Editor of The Cambridge Handbook

62 Henrik Bogdan, Western Esotericism and Rituals of of Western Mysticism and Esotericism.

Initiation (Albany: State University of New York Press, 91 Ibid.,141.

2007), 2. 92 There have been numerous notable Masons with es-

63 Ibid. oteric interests. Three books that document this are:

64 Ibid., 66. Angel Millar, Freemasonry, Foundation of the Western

65 Ibid., 3. Esoteric Tradition (2013) with copious examples of such

66 Ibid., 2. Masons and Masonic texts from the 1600s through

67 Ibid., 69. the present; Joy Hancox, The Byrom Collection (1992),

68 Ibid., 68. focusing on Bro. John Byrom (1692–1763); and Susan

69 Ibid. Mitchell Sommers, The Siblys of London, A Family on the

70 Ibid., 68. Esoteric Fringes of Georgian England (2018), focusing

71 Ibid. on Ebenezer Sibly (1750–1799) and his brothers.

72 Ibid., 74. 93 Kinney, 142.

73 Ibid., 78.

Volume seVenty-fiVe • number two 63

The Philalethes Society

2501 Highway 37

Hibbing, mn 55746 usa

ELECTRONIC SERVICE REQUESTED

ON THE COVER

Free Masons at Work

Stipple etching on paper, 150 × 120 mm, undated

In this edition of Philalethes, David Harrison

continues his exploration of the artistic works

produced by the Rite of Seven Degrees established

by Pierre Lambert de Lintot.

In this image, which is “Dedicated to the

Learned Brethren,” a richly symbolic tableau draws

the observer into a mystical world. Here, Masonic

symbolism unites with visuals reminiscent of the

diagrams of Jakob Böhme to suggest a complex

realm of inner teachings. The esotericism of the

image is undeniable, but its interpretation is

by no means straightforward. For example, the

inner circle of the heavenly chart slightly alters

the Vulgate’s Latin of Psalm 110:10 to read initium

sapientiæ amor Domini, “The love [amor, replacing

timor, “fear”] of the Lord is the beginning of

wisdom.” It seems that mysteries abound.

Known as the Rite of Seven Degrees, this highly

cryptic Masonic system is discussed at length by

Harrison in his article on page 22. His recent book

on the subject, The Rite of Seven Degrees (Lewis

88 philalethes • Masonic,

The Journal of Masonic Research 2021), was reviewed by Marsha Keith

& Letters

Schuchard in the prior edition of Philalethes.

You might also like

- Copy of THE MARTINISM OF SEMELAS - ENG (Ver 2013)Document10 pagesCopy of THE MARTINISM OF SEMELAS - ENG (Ver 2013)Joe DickersonNo ratings yet

- Alchemical Keys To Masonic Ritual Timothy W Hogan PDFDocument52 pagesAlchemical Keys To Masonic Ritual Timothy W Hogan PDFJuan Tenorio100% (11)

- Amorc ApplicationDocument2 pagesAmorc Applicationchili talesNo ratings yet

- Legenda Lodge of Perfection 4-14 - Albert PikeDocument56 pagesLegenda Lodge of Perfection 4-14 - Albert PikePablo Guedes100% (1)

- Rose+Croix LivingDocument22 pagesRose+Croix LivingEn MahaksapatalikaNo ratings yet

- A Basic Model of Western Hermetic TraditionDocument50 pagesA Basic Model of Western Hermetic TraditionAlkimist100% (1)

- A History of Organized Masonic Rosacrucianism PDFDocument41 pagesA History of Organized Masonic Rosacrucianism PDFmiguelorencioNo ratings yet

- Skinner's Key To The Hebrew-Egyptian Mystery (1875)Document405 pagesSkinner's Key To The Hebrew-Egyptian Mystery (1875)Nestor David MoralesNo ratings yet

- JADT Vol10 n3 Fall1988 Levine Condee Riggs Gill JohnsonDocument84 pagesJADT Vol10 n3 Fall1988 Levine Condee Riggs Gill JohnsonsegalcenterNo ratings yet

- THE MELISSINOS RITE A Contribution To SPDocument40 pagesTHE MELISSINOS RITE A Contribution To SPWilly WakkerNo ratings yet

- Pansophic EA Study GuideDocument54 pagesPansophic EA Study GuideEcorajesNo ratings yet

- Historical Data of The Pre MMDocument5 pagesHistorical Data of The Pre MMTMNo ratings yet

- Raisone Occult - Rosacruz - ScanDocument138 pagesRaisone Occult - Rosacruz - ScanismaelNo ratings yet

- The Rose Cross & The Age of ReasonDocument222 pagesThe Rose Cross & The Age of ReasonKuka the KageNo ratings yet

- The Judge Case Volume IDocument490 pagesThe Judge Case Volume IMario DiasNo ratings yet

- Initiation Alchemy and LifeDocument12 pagesInitiation Alchemy and LifeFaith Lenor100% (1)

- An Exposition of The Mysteries Ov FM Fellows, John 1835Document435 pagesAn Exposition of The Mysteries Ov FM Fellows, John 1835Ricardo Sendra Sáez100% (2)

- Arcane SchoolsDocument275 pagesArcane SchoolsTiffany Brooks100% (1)

- F. de P. Castells - The Apocalypse of FreemasonryDocument230 pagesF. de P. Castells - The Apocalypse of FreemasonryCosmomindNo ratings yet

- Hermetic Rose Cross StoryDocument2 pagesHermetic Rose Cross StoryIt's Just Me100% (1)

- Gould - History of Freemasonry Throughout The World Vol. 1 (1936)Document437 pagesGould - History of Freemasonry Throughout The World Vol. 1 (1936)Diego FigueroaNo ratings yet

- Vail, Charles H. - Ancient Mysteries and Modern MasonryDocument256 pagesVail, Charles H. - Ancient Mysteries and Modern MasonryCosmomind100% (7)

- Gould - History of Freemasonry Throughout The World Vol. 3 (1887) (361 PGS)Document361 pagesGould - History of Freemasonry Throughout The World Vol. 3 (1887) (361 PGS)CosmomindNo ratings yet

- Overtone Fuller Blavatsky and Her TeachersDocument305 pagesOvertone Fuller Blavatsky and Her Teachersramano1942No ratings yet

- The Kabbalah: Secret Tradition of The West: PapusDocument4 pagesThe Kabbalah: Secret Tradition of The West: PapusQuentin LawsonNo ratings yet

- SRIA Greater London Pamphlet Dec. MMXXDocument33 pagesSRIA Greater London Pamphlet Dec. MMXXAB1614No ratings yet

- Arcana Saitica - Masonic Tracing Boards (1879) PDFDocument38 pagesArcana Saitica - Masonic Tracing Boards (1879) PDFAlkimist100% (1)

- The True and Invisible Rosicrucian Order, P F Case, 1933Document150 pagesThe True and Invisible Rosicrucian Order, P F Case, 1933gtk1807632105100% (1)

- J D BUCK Symbolism of Freemasonry or Mystic Masonry and The GREATER MYSTERIES of ANTIQUITY First VersionDocument175 pagesJ D BUCK Symbolism of Freemasonry or Mystic Masonry and The GREATER MYSTERIES of ANTIQUITY First VersionVak Amrta100% (1)

- To Be A True Noachidae The Noachite LegeDocument14 pagesTo Be A True Noachidae The Noachite LegeAlbert Le Roux100% (1)

- Orderoferi R PDFDocument41 pagesOrderoferi R PDFnlbrochadoNo ratings yet

- Xxxii SRDocument176 pagesXxxii SRMaya Marinkowitch100% (1)

- A Ritual and Illustrations of FreemasonryDocument308 pagesA Ritual and Illustrations of FreemasonryRicardo Sendra SáezNo ratings yet

- Manly P Hall - A Vital Concept of Personal GrowthDocument35 pagesManly P Hall - A Vital Concept of Personal GrowthMauro DiasNo ratings yet

- Contemplative Geometry in FreemasonryDocument7 pagesContemplative Geometry in FreemasonryAlexander ElderNo ratings yet

- History of The Rose-CroixDocument65 pagesHistory of The Rose-CroixdjhlllNo ratings yet

- Mystic Symbolism of Ancient Guilds (1915-1918?) by ProfundisDocument11 pagesMystic Symbolism of Ancient Guilds (1915-1918?) by Profundissauron385100% (16)

- JSM Ward - Gone WestDocument188 pagesJSM Ward - Gone WestSax_CrusNo ratings yet

- Voorhis Harold - History of Masonic RosicrucianismDocument56 pagesVoorhis Harold - History of Masonic RosicrucianismIgnacio AndreattaNo ratings yet

- The Temple LegendDocument6 pagesThe Temple LegendDavid MartinNo ratings yet

- Capitular MasonryDocument4 pagesCapitular MasonryjoeNo ratings yet

- Magical Writings of Thomas Vaughan PDFDocument198 pagesMagical Writings of Thomas Vaughan PDFAtanas KrastevNo ratings yet

- Frater Acher - On The Order of The Asiatic Brethren PDFDocument72 pagesFrater Acher - On The Order of The Asiatic Brethren PDFJonnyC9No ratings yet

- A Christian Rosenkreutz AnthologyDocument3 pagesA Christian Rosenkreutz AnthologyJavierLeón25% (4)

- Flowers Stephen Edred - Freemasonry and The Germanic Tradition PDFDocument31 pagesFlowers Stephen Edred - Freemasonry and The Germanic Tradition PDFCenizas de un Hoguera - Los Autores de la Barbarie100% (2)

- J. Ross Robertson - Talks With Craftsmen 1890Document200 pagesJ. Ross Robertson - Talks With Craftsmen 1890Alkimist100% (1)

- Arsquatuorcoronatorumv7 PDFDocument348 pagesArsquatuorcoronatorumv7 PDForvatsNo ratings yet

- The Golden Calf, Which the World Adores, and DesiresFrom EverandThe Golden Calf, Which the World Adores, and DesiresNo ratings yet

- Man or Matter: Introduction to a Spiritual Understanding of Nature on the Basis of Goethe's Method of Training Observation and ThoughtFrom EverandMan or Matter: Introduction to a Spiritual Understanding of Nature on the Basis of Goethe's Method of Training Observation and ThoughtNo ratings yet

- The Golden Builders: Alchemists, Rosicrucians, and the First FreemasonsFrom EverandThe Golden Builders: Alchemists, Rosicrucians, and the First FreemasonsNo ratings yet

- Babylonian-Assyrian Birth-Omens and Their Cultural SignificanceFrom EverandBabylonian-Assyrian Birth-Omens and Their Cultural SignificanceNo ratings yet

- 44 Letters to Gustav Meyrink: English TranslationFrom Everand44 Letters to Gustav Meyrink: English TranslationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Patron Saints and The Point Within The CircleTheDocument10 pagesPatron Saints and The Point Within The CircleThePablo GuedesNo ratings yet

- PM 57 Franklin Freemason Paris LegDocument11 pagesPM 57 Franklin Freemason Paris LegPablo GuedesNo ratings yet

- Bedes de Tabernaculo and de TemploDocument15 pagesBedes de Tabernaculo and de TemploPablo GuedesNo ratings yet

- The Hiramic Legend and The Creation of The Third Degree - Christopher PowellDocument27 pagesThe Hiramic Legend and The Creation of The Third Degree - Christopher PowellPablo GuedesNo ratings yet

- The Esotericism of The Esoteric School of Quatuor Coronati Lodge - Henrik BogdanDocument13 pagesThe Esotericism of The Esoteric School of Quatuor Coronati Lodge - Henrik BogdanPablo GuedesNo ratings yet

- The Noah Legend and The Graham Manuscript - John AcasterDocument22 pagesThe Noah Legend and The Graham Manuscript - John AcasterPablo GuedesNo ratings yet

- The Evolution of The Second Degree by Lionel Vibert (PL 1926)Document15 pagesThe Evolution of The Second Degree by Lionel Vibert (PL 1926)Pablo GuedesNo ratings yet

- The Spirit of Masonry in Moral and Eluci PDFDocument281 pagesThe Spirit of Masonry in Moral and Eluci PDFPablo GuedesNo ratings yet

- Ahiman Rezon - Laurence Dermott (1764) PDFDocument273 pagesAhiman Rezon - Laurence Dermott (1764) PDFPablo Guedes100% (1)

- The Development of The Trigradal System by Lionel Vibert (PL 1925)Document15 pagesThe Development of The Trigradal System by Lionel Vibert (PL 1925)Pablo GuedesNo ratings yet

- Performance Task 1Document3 pagesPerformance Task 1api-236548202No ratings yet

- (Charles A. Poynton) A Technical Introduction To D PDFDocument270 pages(Charles A. Poynton) A Technical Introduction To D PDFrajeshksmNo ratings yet

- Carlos - Movimientos La Serie 49gurdjieffDocument6 pagesCarlos - Movimientos La Serie 49gurdjieffCarlos De La Garza0% (1)

- Intimations of Immortality From Recollections of Early ChildhoodDocument5 pagesIntimations of Immortality From Recollections of Early ChildhoodMoga CosminNo ratings yet

- CollisionsDocument28 pagesCollisionsIndushika SubasingheNo ratings yet

- CH 4 Part II - CH 5 American RevolutionDocument2 pagesCH 4 Part II - CH 5 American RevolutionMichael SinclairNo ratings yet

- Lesson PlanDocument8 pagesLesson PlanNoelle LuadNo ratings yet

- BHIKHU PAREKH - Some Reflections On Hindu Tradition of Political ThoughtDocument15 pagesBHIKHU PAREKH - Some Reflections On Hindu Tradition of Political ThoughtPooja Pandey100% (1)

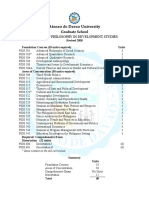

- Ateneo de Davao University: Graduate SchoolDocument1 pageAteneo de Davao University: Graduate Schoolkfbrand71No ratings yet

- Chapter 9 - 10 Questions FrankensteinDocument2 pagesChapter 9 - 10 Questions Frankensteinbotato. exeNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Influence of Twitter On Nigerian Youths During The ENDSARS Protest by Ofure AmenkhienanDocument34 pagesUnderstanding The Influence of Twitter On Nigerian Youths During The ENDSARS Protest by Ofure AmenkhienanamenkhienanoNo ratings yet

- Erpedana Company Profile 2009Document25 pagesErpedana Company Profile 2009ErpedanaNo ratings yet

- Philosophy Module 1 Lesson 1 Nature of PhilosophyDocument26 pagesPhilosophy Module 1 Lesson 1 Nature of PhilosophyRemar Jhon Paine100% (1)

- Physics 104 Optics NewDocument199 pagesPhysics 104 Optics Newbitconcepts9781No ratings yet

- Ethics GuideDocument10 pagesEthics GuideNATHANIEL GUIANANNo ratings yet

- Florentino Vs Encarnacion - DigestDocument2 pagesFlorentino Vs Encarnacion - Digestcmv mendoza100% (3)

- Mangaoil - Poetry ProjectDocument21 pagesMangaoil - Poetry Projectapi-408316181No ratings yet

- Wallerstein (2000) - Olver Cox As Word-Ystems Analyst (OCR)Document11 pagesWallerstein (2000) - Olver Cox As Word-Ystems Analyst (OCR)Armando GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Ashvarudha Mantra JapaDocument10 pagesAshvarudha Mantra JapaRNNo ratings yet

- The Source in Homeopathy Irene Schlingensiepen Brysch.03960Document14 pagesThe Source in Homeopathy Irene Schlingensiepen Brysch.03960Tzadi0% (1)

- Dirac Delta FunctionDocument5 pagesDirac Delta FunctionkrishnaNo ratings yet

- JJJJDocument284 pagesJJJJthoth11No ratings yet

- Revisiting Fit Between AIS Design and Performance With The Analyzer Strategic-TypeDocument16 pagesRevisiting Fit Between AIS Design and Performance With The Analyzer Strategic-TypeYeni Puri RahayuNo ratings yet

- Knowledge International University: Final AssignmentDocument4 pagesKnowledge International University: Final AssignmentHassan BasarallyNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Arguments and Truth ClaimsDocument59 pagesEvaluating Arguments and Truth ClaimsGhulam Mehr Ali ShahNo ratings yet

- Mingala SuttaDocument25 pagesMingala SuttaJohn SwarminatorNo ratings yet

- Un Symmetrical Bending and Shear CentreDocument11 pagesUn Symmetrical Bending and Shear CentreanilNo ratings yet

- Second Language Teaching MethodsDocument3 pagesSecond Language Teaching MethodsHernán ArizaNo ratings yet

- Do You Think The Rational Actor Model Is Applicable To Understanding Addictive Behavior?Document4 pagesDo You Think The Rational Actor Model Is Applicable To Understanding Addictive Behavior?wilsonv92No ratings yet