Violent Acts and Violent Times: A Comparative Approach To Postwar Homicide Rates

Violent Acts and Violent Times: A Comparative Approach To Postwar Homicide Rates

Uploaded by

ripistheword360Copyright:

Available Formats

Violent Acts and Violent Times: A Comparative Approach To Postwar Homicide Rates

Violent Acts and Violent Times: A Comparative Approach To Postwar Homicide Rates

Uploaded by

ripistheword360Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Violent Acts and Violent Times: A Comparative Approach To Postwar Homicide Rates

Violent Acts and Violent Times: A Comparative Approach To Postwar Homicide Rates

Uploaded by

ripistheword360Copyright:

Available Formats

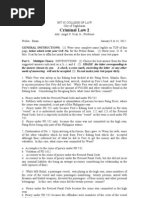

Violent Acts and Violent Times: A Comparative Approach to Postwar Homicide Rates

Author(s): Dane Archer and Rosemary Gartner

Source: American Sociological Review , Dec., 1976, Vol. 41, No. 6 (Dec., 1976), pp. 937-963

Published by: American Sociological Association

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2094796

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

American Sociological Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend

access to American Sociological Review

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES:

A COMPARATIVE APPROACH TO POSTWAR HOMICIDE RATES *

DANE ARCHER AND ROSEMARY GARTNER

University of California, Santa Cruz

American Sociological Review 1976, Vol. 41 (December):937-963

The idea that waging war might increase the level of domestic violence in warring

societies has occurred to many researchers. Discussions of this possibility have been limited

to a very small number of case studies-often as limited as the experience of a single

nation in a single war. A major obstacle to the general investigation of this question

has been the unavailability of comparative data on homicide rates. Over a three-year

period, a Comparative Crime Data File was assembled. The file includes time-series

rates of homicide for roughly 110 nations beginning in about 1900. Postwar rather than

wartime homicide rates were analyzed, since postwar data appear much less problematic

and are likely to be affected by artifacts in only a conservative direction. The homicide

data were analyzed to: (1) determine if postwar increases did occur and (2) identify

which of seven competing theoretical models appeared to offer the most adequate expla-

nation. The homicide rate changes after 50 "nation-wars" were compared with the

changes experienced by 30 control nations. The major finding of the study was that most

of the nation-wars in the study did experience substantial postwar increases in their

rates of homicide. These increases were pervasive, and occurred after large wars and

smaller wars, with several types of homicide rate indicators, in victorious as well as

defeated nations, in nations with both improved and worsened postwar economies,

among both men and women offenders and among offenders of several age groups.

Homicide rate increases occurred with particular consistency among nations with large

numbers of combat deaths. Using homicide and other data, it was possible to disconfirin

or demonstrate the insufficiency of six of the seven explanatory models.

During the Vietnam War, the murder Although the sudden increase in violent

and nonnegligent manslaughter rate in the crimes during the Vietnam War suggests

United States more than doubled. The inci- some theoretically interesting possibilities,

dence of these homicides was 4.5 (per more information obviously is required

100,000 inhabitants) in 1963 and 9.3 in before any general relationship between

1973 (F.B.I., 1963-73, Uniform Crime war and criminal homicide can be inferred

Reports). This rapid increase was some- -the case of a single nation during a

what more remarkable because it followed single war can only be a point of departure.

a period of almost monotonic decline in This paper attempts to address two con-

the homicide rate since record-keeping ceptually separable questions: (1) the

began in 1933. empirical question of whether, in general,

homicide rates do increase after wars and,

* This project and the development of the 110- if such increases are found, (2) the inter-

nation Comparative Crime Data File were sup- pretive question of which of seven theo-

ported by NIMH Grants Number MH 25881

retical models appears to provide the most

and MH 27427 from the Center for Studies of

Crime and Delinquency, by the Socity for the adequate explanation of these increases.

Psychological Study of Social Issues and by the The idea that war might foster crime and

Faculty Research Fund of the University of violence has occurred to many. Although

California. The authors are indebted to several

the first appearance of the idea is difficult

people for helpful comments and advice, includ-

ing Marshall Clinard, John Kitsuse, Thomas Pet-

to trace with certainty, Erasmus, Sir

tigrew, Robert Rosenthal, Thorsten Sellin, Mur- Thomas More and Machiavelli each specu-

ray Straus, Marvin Wolfgang and the hundreds lated that wars left a postwar legacy of

of people around the world who helped us during increased crime and lawlessness (Abbott,

the collection of the Comparative Crime Data

1918; 1927; Hamon, 1918).

File. Responsibility for the findings and interpre-

tations in this paper belongs, of course, to the Perhaps not surprisingly, much of the

authors alone. popular and scholarly writing on this ques-

937

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

938 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

tion has appeared during or immediately Most research published in this period,

following wars. Shortly after World War I however, was concerned with the impact

ended, for example, several public figures of the First World War itself. There were

and writers suggested that the war had in- studies of this question in Austria (Exner,

creased crime. Among these were Winston 1927), France (Calbairac, 1928), Italy

Churchill, Clarence Darrow and Abbott (Levi, 1929), Czechoslovakia (Solnar,

Lawrence Lowell, then President of Har- 1929), Germany (Leipman, 1930), the

vard University (Abbott, 1927:213; Dar- United States, (Engelbrecht, 1937; Suther-

row, 1922:218; Lowell, 1926:299). The land, 1943) and England (Mannheim,

rich history of the idea that wars affect the 1941; 1955). The most influential of these

level of violence in postwar societies is researchers appear to have been Exner

reviewed elsewhere (Archer and Gartner, (1927), who attributed crime increases to

forthcoming). economic problems after wars, and Mann-

The end of the First World War also saw heim, who emphasized non-economic fac-

the appearance of some of the first schol- tors like "the general cheapening of all

arly work on the question. For reasons values; loosening of family ties; [and]

discussed below, the comparability of dif- weakened respect for the law, human life,

ferent case studies is complicated by a and property" (Mannheim, 1955:112).

number of factors. A number of these In the most rigorous study of this per-

early studies dealt with nineteenth century iod, Sellin (1926) compared postwar hom-

(and, in one case, eighteenth century) icide changes in five belligerent nations in

wars. Tarde (1912), Bonger (1916) and World War I and four nonbelligerent na-

Roux (1917) discussed changes in various tions. Sellin concluded that the warring na-

crimes in France following the Revolution tions did experience increases, although

of 1848 and in both France and Germany differences between the warring and non-

after the 1870 Franco-Prussian War. belligerent nations were not uniform.

Based on a review of six nineteenth cen- World War II renewed interest in this

tury case studies, Sorokin (1928:340-4) question. A number of discussions dealt

concluded that whether a war increased with crime changes during wartime years,

crime depended upon the success of the including Sellin (1942), Reckless (1942),

war, its popularity, whether it was fought Glueck (1942), Bromberg (1943) and

at home or abroad and other factors. von Hentig (1947). Wartime changes in

Based on legislation and published ac- nine Allied and neutral nations were also

counts of the era, Nevins (1924) con- surveyed by an international group of

cluded that the American Revolution had criminologists (Commission Internationale

produced an upsurge of horse-stealing and Penale et Penitentiaire, 1951). Postwar

highway robbery in many states. Abbott changes were examined for five countries by

(1927) reviewed prison records from 11 Lunden (1963; 1967) who compared the

states and concluded that the Civil War raw number of crimes committed after the

had greatly increased the number of men war with the number committed during the

single year prior to the outbreak of the

sent to prison, and that many of these

war. Lunden reported finding increases

men were veterans. Abbott concluded that

after the war and he attributed these to

the imprisonment of these veterans con-

social changes attendant upon war, includ-

tributed to the formation of a prison re-

ing social disorganization, increased mobil-

form movement in 1867; she quotes from

ity and disruption of community life.

a contemporary author:

There have been very few recent studies

"A man who has lost one arm in the de- of crime changes during wars. As part of a

fense of the nation working with the other study of American political turmoil during

at the convict's bench is not an agreeable the Vietnam War, Tanter (1969) noted

spectacle, nor do we like to see the com-

the increase in crimes of violence during

rades of Grant and Sherman, of Foote and

Farragut, exchange the blue coat of victory the war years. The increase prompted

for the prison jacket." (Abbott, 1927:234) Tanter (1969:436) to suggest the possi-

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES 939

ability that "as the war continues, it facili- (1918) reported that this practice is at

tates a state of 'normlessness' in which least as old as the Civil War and Mann-

traditional strictures against criminal acts heim (1965) found that it has occurred

lose their effectiveness." in other nations as well; (3) the tendency

This body of research is extremely diffi- of persons arrested during major wars not

cult to evaluate critically. Part of this diffi- to be convicted or imprisoned-Abbott

culty stems from differences of focus. (1918), Mannheim (1941) and von Hen-

Three of these differences, which have not tig (1947) reported evidence of a reduced

always been made explicit by individual re- willingness to prosecute offenders and a

searchers, have been between (1) re- tendency for wartime employers to pay the

searchers who have been concerned with fines of their workers rather than lose

crime rate changes during wars and re- them to imprisonment; (4) the fact that

searchers concerned with postwar changes, parolees too old for the armed services,

(2) researchers who have studied homicide unlike their peacetime counterparts, have

and researchers who have studied theft, easily found employment due to labor

violent crime or crime in general, undiffer- shortages created by wars-von Hentig

entiated by type and (3) researchers who (1947) found that many more jobs were

have been concerned with the direct effects found for New York State parolees during

of wars upon the behavior of returned vet- World War II than before it; (5) the

erans and researchers interested in the pos- wartime shortages of commodities often in-

sibility of more general effects upon the volved in crimes, particularly alcohol

civilian populations of combatant nations. (Abbott, 1918; Exner, 1927; Mannheim,

These differences of focus have had 1941); (6) changes in national systems of

important implications, since individual re- law enforcement, including a shortage of

searchers have tended to generate hypoth- policemen (Mannheim, 1965). The im-

eses appropriate to only one possible effect pact of all of these factors seems likely

of war-e.g., postwar homicides commit- to vary directly with the level of wartime

ted by returned veterans. These differences mobilization-crime rates will be more de-

among researchers also have made a com- pressed by these factors in large wars than

parison of their findings a formidable task, in small wars.

since they have frequently been discussing During some wars, there also may be

quite different phenomena. social changes that increase crime rates,

For several reasons, some aspects of including (1) the disruption of families by

the study of war and crime are more prob- conscription, long employment hours and,

lematic than others. For example, the inter- sometimes, evacuation (Mannheim, 1941);

pretation of crime rates during major wars (2) the existence of special crime oppor-

is severely complicated by the large number tunities like blackouts, bombed-out houses

of simultaneous social changes. During and other unguarded property (Mannheim,

major wars, crime rates are likely to be 1941:131); (3) the creation of new types

depressed by many of these social changes of crimes by special wartime regulations

including: (1) the massive removal of like rationing (Sutherland and Cressey,

young men from the civilian population 1960:208).

through conscription and enlistment-for Finally, other factors that have limited

example, von Hentig (1947) reported that the usefulness of wartime offense data

New York City shrank by three-quarters are (1) the confusion of crimes and acts

of a million people, mostly young males, of resistance in occupied nations (Mann-

during World War II, and Bennett (1953) heim, 1965); (2) a persistent belief that

estimated that when World War II broke "crime-prone" persons tend to enlist-as

out 82% of American men between 20 Tarde (1912) proposed; (3) changes in

and 25 enlisted or were drafted; (2) the the boundaries of warring nations (Suther-

premature release of convicts on the con- land, 1943); (4) the fact that record-

dition that they enter the armed forces keeping often has been interrupted during

rather than return to civilian life-Abbott wartime.

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

940 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

Because of all these simultaneous social (von Hentig, 1947:349). Since young men

and economic changes during a major war, are universally overrepresented in many

many researchers have concluded that the offense rates, particularly homicide (Wolf-

immediate effects of wars on offense rates gang and Ferracuti, 1967), massive losses

are extremely difficult to discern (von Hen- of young men remove from the population

tig, 1947; Sutherland and Cressey, 1960; precisely those who would be most likely

Mannheim, 1965). Some researchers (e.g., to commit these offenses in the postwar

Willbach, 1948) have completely aban- years.

doned hope of making meaningful com- A second factor, which would also oper-

parisons between wartime years and peace- ate in a conservative direction, involves the

time years. Despite the inherent and per- possibility that veterans arrested for or

haps insurmountable problems with the in- convicted of certain crimes would be

terpretation of crime rates during war years, treated with leniency because of their mil-

the pattern generally has been one of a itary service. Such a practice has existed

sharp drop during the initial year or years for some time-for example, Abbott

of a war, followed by a gradual return (1918) said that after the Civil War

late in the war to prewar levels (Mann- judges often pardoned first offenders who

heim 1965; Lunden, 1967). were veterans. Leniency toward arrested

Although there are also a number of veterans also has been cited by researchers

complexities in the interpretation of post- of the First World War, even in cases in-

war rates, this topic is more promising volving very serious offenses (Mannheim,

methodologically than the analysis of rates 1941: 119).

during wars. In general, this is because Leniency of this kind would affect some

many of the special characteristics of war- offense indicators more than others, and

time society diminish or disappear with the the indicators farthest removed from the

end of the war. The beginning of peace offense itself would be most affected. Data

generally (1) returns large numbers of on convictions and prison population,

young men to civilian society and reunites therefore, would be most influenced. Data

families; (2) eliminates tremendous war- on the number of offenses known to the

time labor needs; (3) restores law enforce- police, however, would be unaffected by

ment agencies to normal manpower levels; judicial leniency. This difference between

(4) ends war-related commodity shortages. types of crime indicators was emphasized

There may be some social and demo- in a discussion of wartime crime by Suther-

graphic changes, however, that could con- land (1956), who concluded that convic-

tinue to affect offense levels in postwar tion rates were potentially misleading (i.e.,

periods. Virtually all of these postwar too low) because of factors like judicial

factors would affect rates in a conservative leniency. At any rate, judicial leniency

direction-i.e., reduce levels of various (like the loss of young men) could only

offenses in the postwar years compared to operate in a conservative direction, so that

the prewar period. the observed rates of some offenses would

One of the most important of these post- understate the actual incidence of these

war factors, particularly after major wars, crimes.

involves changes in the age and sex struc- Although the data needed for studies of

ture of a nation's population due to the postwar changes are therefore relatively

number of young men killed during the interpretable, available studies on this ques-

war. These losses sometimes have been of tion have left important questions un-

enormous magnitude. For example, at the answered. For example, a critical issue

end of World War I, out of every 1000 which has not been adequately addressed is

men who had been between 20 and 45 whether only warring nations experience

at the outbreak of the war, 182 had died postwar increases or whether all nations

in France, 166 in Austria, 155 in Ger- (combatant and noncombatant) experience

many, 101 in Italy, and 88 in Britain comparable increases. With apparently a

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES 941

single exception (the study by Sellin national war participation led him to con-

(1926) cited earlier), case studies of post- clude that, "For these reasons, the effect

war crime rate trends have not analyzed of wars on crimes is not a good theoretical

a "control" group of nations uninvolved in problem" (Sutherland, 1956:120).

war. Without such a controlled comparison In summary, studies of wartime or post-

based on a large sample of nations, it is war changes in crime rates have tended

impossible to separate the direct effects of to be inconclusive for a number of different

war from international crime rate trends reasons. Studies of crime changes in war-

which happen to include the warring time probably cannot go beyond simple de-

nations. scription, because of the large number of

One reason a strategy of controlled com- interdependent social changes which have

parison has not been attempted is simply occurred during most wars. Studies of

the unavailability of historical and com- crime changes in postwar years, while more

parative crime data. Time-series crime data promising, have been weakened in the

have not been accumulated in any cen- past by: (1) extremely small sample sizes,

tralized manner, and individual researchers often as small as a single nation during a

often have been limited to one or at most single war; (2) the absence of a control

a handful of nations. The problem has group of nations uninvolved in the war

been aggravated by variation in the types of studied; (3) different types of crime rate

indicators kept by individual nations indicators that may be differentially suscep-

(Wolfgang, 1967). It has been recognized tible to artifacts and therefore incompar-

for some time (Sellin, 1931) that arrest able; (4) the failure to operationalize

and conviction data are more subject to characteristics of different types of national

judicial and police discretion than data on participation in wars.

the number of known offenses. Since these

types of discretion could be important fac- THEORETICAL MODELS

tors in postwar societies (particularly in the

case of veterans suspected of some offense), A number of theoretical models have

the net effect of this variation in record- been advanced to explain crime rate

keeping is to reduce the comparability of changes during war years, during postwar

data kept by certain nations. Variation in years or both. Some indication of the va-

indicators, therefore, increases the difficulty riety of competing explanations is con-

of obtaining a sufficiently large number of tained in a comment by Sutherland (1956:-

combatant and control nations. 120-1):

A second limitation of studies of post- One theory states that war produces an in-

war changes has been their inattention to crease in crimes because of the emotional

differences in national war experiences, instability of wartime, and another states

that wars produce a decrease in crimes be-

since these differences are likely to produce

cause of an upsurge of national feeling.

dissimilar effects on crime rates-as sug- One states that crimes of violence increase

gested by Sorokin (1928), Mannheim in wartime because of the contagion of vio-

(1941) and Sutherland (1956). In part, lence, and another that they decrease be-

this omission has been an inevitable con- cause of the vicarious satisfaction of the

need for violence.

sequence of the extremely small samples

available. However, Sutherland (1956) We have identified seven theoretical

concluded that an examination of the ef- models which attempt to explain the effects

fects of different types of war participation of war on wartime and postwar rates of

was impossible -at the time he wrote, since various offenses, and we have tried to de-

variations in the experiences of individual rive expectations or predictions from each

nations in individual wars had not been of the seven models. There is some agree-

quantified. Since Sutherland believed that ment between the predictions implicit in

these differences could be important, the two or more of the theoretical explanations.

absence of empirical bases for comparing However, the seven models are sufficiently

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

942 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

distinct theoretically to justify a separate social disorganization model predicts that

discussion of each. postwar crime increases would occur as a

function of rapid social changes which any

1. Social Solidarity Model warring nation could experience. As used

Several researchers have suggested that by other researchers, this model predicts

wars increase social solidarity and, as a that crime rate increases would be con-

result, reduce crime rates. For example, fined to defeated nations.

Sumner wrote in his classic Folkways

(1906:12) that wars increased discipline 3. Economic Factors Model

and the strength of law. It has even been Economic factors often have been cited

suggested that habitual "criminals" are in- as a cause of wartime and postwar crime

fluenced by the exigencies of war. For ex- rate changes. Commodity shortages and

ample, Mannheim (1941:108) quoted a other economic changes were the main var-

1914 article from The Times of London: iables in Exner's (1927) theory concern-

"The criminal like the honest citizen is ing wartime property crime, and Mann-

impressed by the War conditions which heim (1941:205) also concluded that

make it every man's duty to give as little property offenses "invariably thrive during

trouble as possible." and after wars." The general relationship

The social solidarity model leads to the between economic changes and homicide

expectation that rates of crime would de- is, however, much less clear (e.g., Henry

cline during wartime compared to the pre- and Short, 1954; Radzinowicz, 1971).

war period. The social solidarity model Discussions of war-related economic

also predicts that postwar crime rates changes have reflected two quite different

should, with the passing of the temporary explanatory variables: (1) scarcities cre-

crisis, be comparable to prewar rates. ated by wars and (2) the general level of

employment and other economic indica-

2. Social Disorganization Model

tors. This second explanation reflects the

Wars may disrupt the established order fact that while wartime years frequently

of societies, and some researchers have have brought full employment, postwar

attributed crime increases to this disorgan- years often have not. If economic factors

ization. The concept of social disorganiza- are related to violent crimes, different hom-

tion has been used with considerable im- icide rate changes would be expected as

precision, and there are really two versions a function of the relative economic health

of this model. Some researchers use it to of prewar and postwar society.

describe anomic changes which could occur The economic factors model predicts a

in any warring nation, victorious or de- decrease in postwar property crime rates

feated: property losses, rapid industrializa- in cases where the postwar economy is

tion, changes in the labor force, sudden relatively better than prewar and an in-

population migrations, the breaking up of

crease where the postwar economy is rela-

families, etc. tively worse. The implications of this model

Most researchers, however, have used for homicide rates are, however, unclear.

the concept to describe the social and

psychological changes in a defeated nation 4. Catharsis Model

(Mannheim, 1965:595; Lunden, 1963; A persistent belief about wars has been

1967:77-97). Sutherland and Cressey the idea that wars substitute public violence

(1960:209) used this version of the social for private violence. Sorokin (1925:146)

disorganization model: ". . . postwar crime claimed that revolutions temporarily abated

waves are confined largely to countries "criminal murders" only to have them re-

which suffer rather complete disintegration turn to normal levels at the end of the

of their economic, political and social sys- revolution when legally sanctioned killing

tems as a result of the war." became impossible once again. Many other

As used by some researchers, then, the researchers have suggested that wars pro-

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES 943

vide an outlet or catharsis for aggressive have become habituated, whether by in-

sentiments or "instincts" (e.g., Mannheim, dulging in antisocial or criminal behavior

1941:128). or by offering their services to the highest

The catharsis model predicts that crimes bidder."

of violence would decrease during wartime. 6. Artifacts Model

The implications of this model for postwar

Some researchers have suggested that

rates depend upon how long the cathartic

any changes its wartime or postwar crime

effects are thought to last. However, a

rates are due to various artifacts (e.g.,

corollary of the catharsis model might be

Reckless, 1942:378). Two examples of

the prediction that societies whose exper-

demographic artifacts are the depression

iences in war had been the most violent,

of wartime crime rates by conscription and

and therefore the most cathartic, would ex-

the depression of postwar rates by the loss

perience postwar decreases in violent

of men killed and maimed in the war. In

crimes.

addition, specific artifacts may operate for

5. Violent Veteran Model individual nations in a given war. For ex-

ample, American crime rates in the 1960s

At least since the American Revolution,

began to be influenced by the age structure

people have wondered whether war veter-

changes produced by the "baby boom" of

ans would be more likely than others to

the post-World War II period (President's

commit crimes of violence. In a famous

Commission on Law Enforcement and Ad-

charge to a Charleston grand jury in 1783,

ministration of Justice, 1967:25).

Judge Aedanus Burke said that contem-

It may be possible to control for some

porary violent crime was being committed

artifacts. For example, in the case of the

by men who had become accustomed by

effect of the "baby boom," data on the age

the Revolutionary War to plundering and

of persons arrested could be examined to

killing their enemies and who had since

see if age groups other than the "baby

turned upon their neighbors (Wecter,

boom" cohort experienced changes. The

1944:70). The essential idea of this model

artifacts model does not make any general

is that the experience of war may have re-

predictions, but suggests the need to inspect

socialized soldiers to be more accepting of

any observed crime changes to control for

violence and more proficient at it.

possible artifacts.

It has been suggested, for example, that

combat developed in some men an "appe- 7. Legitimation of Violence Model

tite for violence" (Hamon, 1918:355) and The seventh way in which war could

the "habit" of violent solutions to problems affect postwar homicide rates is through a

(Abbott, 1918:40), and attorney Clarence legitimation of violence. The central con-

Darrow (1922:218) attributed post-World cept of this explanation is that some mem-

War I crime increases to returned veterans bers of a warring society are influenced by

who had been "innoculated with the uni- the "model" of officially approved wartime

versal madness." The idea of the homicide- killing and destruction. During a war, a

prone veteran has also appeared as a fre- society reverses its customary prohibitions

quent theme in fiction (e.g., Remarque's against killing and instead honors acts of

The Road Back, 1931) . violence which would be regarded as mur-

This recurring idea has surfaced again derous in peacetime. Several researchers

in connection with veterans of the Vietnam have suggested that this social approval

War. The potential problems of these vet- or legitimation of violence produces a last-

erans are the subject of several articles in ing reduction of inhibitions against taking

a collection edited by Mantell and Pilisuk human life (Sorokin, 1925:139; Engel-

(1975), and Lifton (1970:32) makes the brecht, 1937: 188-90). This model can be

following prediction about these veterans: illustrated by this quote from a Reverend

"Some are likely to seek continuing out- Charles Parsons around the time of World

lets to a pattern of violence to which they War I:

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

944 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

When the rules of civilized society are sus-

minimize the idiosyncratic experiences of

pended, when killing becomes a business individual nations or of individual wars.

and a sign of valor and heroism, when the

wanton destruction of peaceable women

Inspection of a large number of cases

and children becomes an act of virtue, and would also maximize the chances of dis-

is praised as a service to God and country,covering differential effects of various types

then it seems almost useless to talk about of wars and various types of participation.

crime in the ordinary sense. (Parsons,

In addition, we believe that only a strategy

1917:267)

of controlled comparison between com-

If wartime killing does legitimate homi- batant and noncombatant societies can dis-

cidal violence in some lasting or general count the possibility that both experience

way, as this model suggests, then one would the same crime rate changes.

expect increases in violent crime in postwar

societies. In addition, since civilians and

METHODS AND PROCEDURES

soldiers alike could be influenced by this

legitimation process, this model predicts Comparative Crime Data

that homicide increases will occur among The major obstacle in this area of re-

both veterans and nonveterans. search has been the absence of a dependent

Having listed these seven theoretical variable. For this reason, our first task was

models and the predictions associated with to construct an inventory of crime rate

each one, it should be mentioned that an data with historical and comparative depth.

empirical test of their relative strengths Over a period of three years, we have col-

contains serious pitfalls. As discussed ear- lected a 110-nation Comparative Crime

lier, predictions concerning wartime crime

Data File with time-series rates of various

are probably not investigable. There also offenses for the period 1900-1970.

may be some difficulties in evaluating pre- The principal sources for the creation of

dictions concerning postwar crime. For ex- our data file have been: (1) correspon-

ample, it may be that more than one of dence with national and metropolitan gov-

the models operates after a given war, and ernmental sources in a large number of

their interaction could make a comparison societies; (2) examination of documents

of the models extremely difficult-i.e., the and annual reports of those nations which

effects of one model could mask the effects have published data on their annual inci-

of another. dence of various crimes; (3) correspon-

It is also interesting to consider what dence with other record-keeping agencies.

kinds of evidence would constitute discon- For many nations, of course, the main-

firmation of each theoretical model. In tenance of crime records did not begin as

some previous studies, crime rate changes early as 1900. Developing nations, for ex-

in one society have been treated as suffi- ample, generally have data only for rela-

cient evidence upon which to ground or to tively recent periods. However, several na-

discount certain explanations. For example, tions have crime data from the beginning

Mannheim (1941) based his major work of the century, and a few even have records

on a single nation during a single war- from the mid-1800s-a longer span than

England during World War I. Mannheim we had assumed could be studied. As

interpreted the fact that English homicide might be expected, the records for some

rates did not increase after that war to nations contain gaps due to national emer-

mean that violent crimes do not in general gencies and bureaucratic lapses.

increase after wars. The same single case There are now about 110 nations in our

was used by Sutherland and Cressey comparative data file. For most of the

(1960) as evidence for a refutation of the nations, we have data on the annual inci-

violent veteran model. dence of five types of offenses: homicide,

It is our belief that a fair test of the assault, robbery, theft and rape.

different predictions requires a large and As part of our collection of the 110-

heterogeneous number of cases. This would nation data file, we have reviewed the

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES 945

literature on possible sources of unrelia- offense like homicide (offenses known to

bility and invalidity in official crime data,the police, arrests, convictions, incarcera-

and have used this literature to identify a tions, prison population, etc.), the most

research design that minimizes these prob- accurate is certain to be the number of

lems. The literature concerning these ques- homicides known to the police (Sellin,

tions is large and has been reviewed else- 1931; Ferinand, 1967; Mulvihill and

where (Kitsuse and Cicourel, 1963; Wolf- Tumin, 1969; Clinard and Abbott, 1973:-

gang, 1963; Biderman and Reiss, 1967; 22; Hindelang, 1974). This suggests that

Wheeler, 1967; Hindelang, 1974; Archer a conservative procedure in a cross-na-

and Gartner, 1975), and so will not be tional study would be to limit comparisons

dealt with extensively here. Most research to nations using the best indicators of hom-

on these questions has been done with re- icide. For analyses of trends, however,

spect to U.S. record-keeping practices, there is some evidence that different indi-

specifically the Uniform Crime Reports cators of homicide are highly correlated

(UCR) currently maintained by the FBI over time (Archer and Gartner, 1975).

(1962-1971). We have chosen a research design to

One of the main concerns has been the minimize the effects of these problems.

degree to which official figures underenu- There are three essential features of this

merate the actual incidence of offenses. A design: (1) comparisons will be limited to

number of victimization surveys have esti- homicide; (2) only longitudinal indices of

mated that the magnitude of the "hidden" trends within societies will be compared,

figure of unreported crime is large for cer-

rather than levels across different societies;

tain offenses (Ennis, 1967; Biderman, (3) the analysis will control for the var-

1967; Santarelli et al., 1974a; 1974b). Aiable validity of different indices of homi-

few researchers also have discussed the cide. This third feature will consist of a

interpretability of crime data from other data quality control procedure (Naroll,

countries (Verkko, 1953; Wolfgang, 1967; 1962) that analyzes the national homicide

Wolf, 1971; Clinard and Abbott, 1973). data in two stages. The first of these in-

Three general conclusions emerge from cludes all nations with any type of homi-

research on the possible impact of under- cide indicator (offenses known, arrests,

reporting: (1) underreporting appears to etc.). The second stage, however, will be

be more of a problem for data on the less restricted to only those nations with the

serious offenses and not a major problem best indicator-the number of homicides

for data on homicide (Ferdinand, 1967; known to the police.

Hindelang, 1974); (2) official crime data

from many other nations appear less sub- Records of Wars

ject to underreporting than American data Previous discussions of the possible ef-

(Verkko, 1953; 1956; President's Com- fects of wars on crime also have considered

mission on Law Enforcement and Admin- problems with the independent variable-

istration of Criminal Justice, 1967:20); i.e., the meaningful measurement of char-

(3) although comparisons of the level of acteristics of different wars. For example,

an offense across several societies do not one of the problems cited by Sutherland

appear justified because of national idio- (1956:120) was variation among wars:

syncracies in definition and reporting (cf.

Wolfgang, 1967), comparisons of trends Wars vary widely in many respects, and

the constituent elements have not been

within various societies seem valid be-

standardized, nor have their comparative

cause these idiosyncrasies are likely to weights in the total complex of war been

remain relatively constant within a society determined. Consequently, we do not know,

(Sellin, 1926:31). even approximately, how much more "war"

A second area of concern has been the is involved in one war than in another.

comparability of different indicators of the Since Sutherland wrote, efforts have

same offense. Of all the indicators of an been made to operationalize measures of

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

946 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

the kind he indicated had been lacking. fied for France for discrete wars in this

The most comprehensive analysis has been period.

published by Singer and Small (1972). Two indices of change have been con-

These authors reviewed wars between structed to compare prewar and postwar

1816 and 1965 and, for each war, recorded rates. The first of these is the ratio of the

the number of war dead, the length of each mean homicide rate of the five postwar

nation's participation, the size of each na- years over the mean rate of the five prewar

tion's standing army, etc. Although the years. This index can be expressed as a

Singer and Small study may not have oper- percent comparing the postwar homicide

ationalized all the variables of possible rate to the prewar level.

relevance to our study, it has provided in- The second index of change is a t-test

dices which can be used to compare some between the mean prewar homicide rate

of the ways different wars have affected and the mean postwar rate. This index is

individual nations. similar to the percent measure, but it also

takes into account the variance of the pre-

Procedures

war and postwar rates. The Mtest corrects

This study compares postwar homicide for the degree of fluctuation in the prewar

rates with prewar rates, but, for reasons and postwar periods. In the case of a coun-

discussed earlier, will not discuss wartime try with wildly erratic fluctuations, the t

rates.' The basic design involves a com- would tend to be conservative-i.e., would

parison of the mean level of the rate of diminish the importance of the change. In

homicide during a fixed prewar period withthe case of a country with very stable rates,

the mean level during a fixed postwar however, the index of a postwar increase

period. Somewhat arbitrarily, the length wouldof be enhanced.

both periods has been set at five years, al-

The t-test in this instance is best thought

though homicide data are only available

of as an effect size index, rather than as a

for fewer than five years in a few cases.

conventional test of statistical significance

This length was preferred over shorter

(Cohen, 1969). This is because a t-test

periods (e.g., one year) to minimize the

based on ten observations (five prewar

impact of special social forces in the single

years and five postwar years) is a low

year before and after a war and to reduce

power test, and differences have to be very

the effect of annual fluctuations. The five-

large to reach significance with samples this

year interval was chosen instead of longer

small. In addition, significance levels are

periods for pragmatic reasons-the history

potentially misleading when large numbers

of the twentieth century has not been char-

of t-tests are calculated. For these reasons,

acterized by long intervals of peace. Even

the t-test is used here only as an effect

using a five-year interval, some wars can-

size index which takes into account both

not be interpreted. For example, the

the means and variances of the prewar and

Korean War cannot be included in this postwar periods.2

design, because the five years preceding it

The two indices of change provide dif-

include the years immediately following

ferent kinds of information. The percent

World War II. Use of the five-year interval

measure provides an easily interpretable

also made it impossible to interpret some

index of the overall magnitude and direc-

smaller wars. For example, France was in-

tion of change. The t provides a rough

volved in overlapping and consecutive co-

index of how unusual the change is in

lonial wars for many years after World

terms of the general variability of the na-

War II. For this reason, no peacetime pre-

tion's homicide rate. Although the direc-

war and postwar periods could be identi-

1 Data from the Vietnam War is an exception 2 Indeed, since the number of prewar years and

to this general rule. For this war, the comparison postwar years are the same (five), t bears a

will be between crime rates in the prewar period linear relation to d, and effect size index sug-

and those in the wartime years. This procedure gested for comparisons of two means (Cohen,

was necessary for this war because postwar data 1969:18). In general, d=2t/N'< and, in this

was unavailable. case, d = .707t.

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES 947

-4 o ON C o o- 0 o c Ch Ch t- 't o ~o

* ; * . * .4 *4 *4 * t. * *4 * *6 * .l *4 . * *

N 00 oo q t 0 en q h en en en en WI- * t t e >

8~~~~~~~~~1 6>t^mN ".4 "^_

2 ti E ; t-^ t w E _ = E E e ~~~~ w X

O &. 0 m 'z S a o^t

3 ,,! > - 00 > > > ,,: > W > ] e~~~~~~cd.-(

3 Q e I = 2 2 > z C aii +Q ew 3 =

x~~~~~~~c 11 1 -d I~ I X

| ~ ~~~~ ~ 04 z z g !F

sX~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~e C; coo -o Z

b Ot Ot~~~~~vv

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

948 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

tion (positive or negative) of the two file were used to test specific predictions

measures is always identical, their magni- derived from the seven theoretical models

tudes can be very different. discussed earlier.

There were several steps involved in

using the Comparative Crime Data File. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

First, homicide data for some nations had

Our analysis indicates that combatant

to be converted from raw numbers to rates. nations in the two World Wars were more

This was done using available demo- likely to experience homicide rate increases

graphic data (chiefly the U.N. Demo- than control nations. The two measures

graphic Yearbook 1955; 1963; 1970-3). (% and t) of homicide rate change for

For many nations, the data was already combatant and control nations are shown

in the form of rates per 100,000 inhabi- in Table 1.

tants. In control nations for these two wars,

Second, the tables in Singer and Small homicide rate changes were evenly dis-

(1972) were used to determine the dates tributed, with some nations decreasing,

of entrance and withdrawal for each nation some increasing and some remaining un-

participating in a war. This information changed. For the 25 "nation-wars," how-

was used to identify the five prewar years ever, postwar increases outnumbered de-

and the five postwar years. creases by 19 to six.3 Combatant nations

in these two wars, therefore, were more

Third, comparison or control nations not

likely to experience postwar increases than

participating in a given war were identified

were control nations.4

from the comparative file. For both World

War I and II, the control group consisted The increases experienced by some com-

of all the nations in the file for those years batant nations in Table 1 were very large.

which did not participate in these wars. In Italy following World War II, for ex-

The control nations for other wars were ample, the homicide rate more than dou-

chosen using procedures discussed below. bled (an increase of 133%). The large

effect size index (t) associated with this

Fourth, the two measures of change in

change (3.07) indicates that this increase

homicide rates (% and t) were calculated

was very unusual with respect to Italy's

for both participating and control nations.

The changes for individual nations then

3.The unit of analysis is the "nation-war"~-i.e.,

were grouped into three categories accord-

one nation in one war. The number of individual

ing to the magniture of the percent mea- nations in Table 1 is less than the number of

sure. Nations which changed downward units, since some nations were involved in more

more than 10% were categorized as de- than one war. In Tables 1 and 2 combined, the

total number of nation-wars is 50 and the total

creasing, nations which changed upward

number of different combatant nations in these

more than 10% were categorized as in- wars is 28.

creasing, and nations in which the changes 4Although most of the control nations in

had an absolute magnitude of 10% or less

Table 1 indicate no homicide increases, or only

were categorized as unchanged. Then the

small increases, there are two anomalous cases:

Finland and Thailand after World War I. Both

number of combatant and control nations

of these nations show large homicide increases

falling into each of these categories was after World War I, and the size of these increases

compared. prompted us to investigate further the classifica-

Fifth, using only combatant nations, an tion of these nations as controls. A letter to the

Finland Consulate revealed that Finland under-

effort was made to determine what types went an "internal" or civil war in 1918, and

of war participation produce the greatest Thailand is identified in the Encyclopedia

changes. Two of the variables examined Britannica as having sent troops to the Allied

were: (1) the number of men killed dur- cause during World War I. This information

ing the war, as a proportion of the nation's raises questions about the wisdom of classifying

these two nations as controls for World War I.

total population and (2) whether the However, since neither nation was listed as a

nation was victorious or defeated. combatant by Singer and Small (1972), they are

Finally, other data in the comparative retained as controls in Table 1.

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES 949

V!W"oo o t " Il t- "I o _

to > P-4 m .-"s

z~~~~~~~

zD o *>^tu

z Xn z o 1, V-4t

oo en~r WI No o o c ^ . -tee -I

vo 0 f

a te V U5 _A.0 ena

Q ,lll ,llllllll i

X t~mt Oneeen"^00 en

q 8 g S 02 V V V~~~"1 cm

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

950 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

general variability.5 There were also cases only the population "at risk" for homicide

of modest increases that were still rela- (e.g., males over 15), the increases for

tively large when judged in terms of the combatant nations would be even larger

general variability of the homicide rate. than shown in Table 1 (Nettler, 1974:59).

For example, the homicide rate in Belgium The fact that combatant nations still

after World War I experienced a 24% showed increases greater than the control

increase, but the t associated with this in- nations, despite the conservative effect of

crease (5.36) suggests that the change was these two demographic changes, is there-

very big in terms of Belgium's general fore particularly striking.6

variability. For smaller wars, the differences are in

Finally, there was at least one case the same direction, although less pro-

where the percent increase was compara- nounced. For the Vietnam War, since post-

tively larger than the corresponding t-test. war data were unavailable, the measure of

For Norway following World War II, a change involves a comparison of wartime

fairly large increase in the homicide rate years with the prewar period. This war

(65%) was tempered by only a moderate did not involve total mobilization of the

t (1.90), indicating that Norwegian homi- combatant societies (except for Vietnam

cide rates were characterized by consider- itself), and therefore wartime rates were

able variation during this period. unlikely to have been distorted by major

Even though the difference between demographic changes. Data for six com-

combatant and control nations in Table 1 batant nations in this war are included in

is quite large, this comparison is a con- Table 2.

servative test. As discussed earlier, the All six combatant nations in the Viet-

large numbers of young men killed in these nam War experienced homicide rate in-

wars dramatically changed the age and sex creases, although three of these increases

structures of the populations of combatant were less than 10 percent. The selection of

nations. As a result, the postwar homicide control nations for this war posed some

rates for the combatant nations were based problems, since the 1960s are a thickly

on populations depleted of young men- covered period in our 110-nation file. The

the group most likely to commit homicide. control nations shown in Table 2 were

The analysis in Table 1 may be conserva- matched with the six Vietnam combatants

tive for a second reason as well; the birth on the basis of geographic proximity. Three

of postwar babies in combatant nations of the six control nations experienced in-

(particularly after World War II) tends creases, but the other three controls exper-

to reduce postwar homicide rates by inflat- ienced decreases.

ing the population denominator on which Although the number of combatant and

they are based. control nations for the Vietnam analysis is

The net effect of these two demographic small, there is a tendency toward more

changes is to reduce postwar homicide consistent increases among the combatants.

rates in the combatant nations. If refined There is also reason to think that post-

homicide rates were available based on Vietnam War homicide rates may be even

higher than the wartime rates used in

5 The increase is even larger when judged Table 2. In the U.S., for example, the

only in terms of the prewar variation. We calcu-

homicide rate continued to increase with

lated a z-score measure of change which was

the difference between the prewar mean and

postwar mean, divided by the prewar standard 6 The comparison is probably a conservative

deviation. For Italian homicide rate increases test for a third reason as well. That is, there may

after World War II, this z-score measure was be some ways in which even control societies

11.62-larger than the corresponding t of 3.07. are affected by large wars like the two World

This indicates that the war not only increased Wars. The idea that the crime rates of even neu-

the level of the homicide rate but also increased tral nations might be influenced by massive wars

the instability or variance of the rate. For all has been suggested by Lunden (1963:5). If

the nation-wars in the study, however, this z-score changes did occur in neutral nations, of course,

index of change was significantly correlated withthey would be reflected in inflated increases in

t (r = .66, p <.001). the control nations in Table 1.

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES 951

0

u

cd

cl

cd

t0

cc 00 0 g ".4

cd 0-i

CIS

0 cis

4-4 .4 +5 0 C's

c5s" C'd O 'm 4 Q

E.-4 U 44

(D

cd

>c

co

z aA

0 aA

cod V-4 r-4 X

co

C'd

C's C'S

cd cd

C's

cd

C4

WI

C13 C4 t-

kn o

a-, C's

VI cd

0

u cd cd cd 0 cd cd

(D __l

4

w 0

>1

cd

k cd 0 4)

0 +_ cd

0-4 0.4 00 0-4 m U W4 01-41 04

cri

S

cd 19

cd u

4.0

(D 0

-cod 0

E-4 O z u z

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

952 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

each year of the Vietnam War. As a result, war data on homicide convictions could be

although the mean U.S. wartime rate was depressed by judicial leniency toward vet-

42% higher than the prewar rate (as erans. The possibility of this type of error

shown in Table 2), the rate in the last led Sutherland (1956) to conclude that

years of the war was much higher-e.g., the indicator of convictions was seriously

in 1973 the U.S. homicide rate was 107% misleading. To control for the variable

higher than the mean prewar rate. validity of different indicators, the analyses

The magnitude of the U.S. homicide rate of Tables 1 and 2 have been repeated using

increase during the Vietnam War was also only nation-wars for which the best homi-

very large when judged by the t measure cide indicator is available-the number of

of change. The t associated with this war offenses known. This data quality control

(2.58) indicates that the wartime increase procedure, which removes nations with

was very large when compared to the gen- indicators like arrests and convictions, pro-

eral stability of the homicide rate. duces the results shown in Table 3.

A similar pattern occurs in the other The results in Table 3 produce the same

small wars for which analysis is possible. conclusion as the analyses in Tables 1 and

The number of interpretable nation-wars 2; combatants were more likely to exper-

is constrained by: (1) the need for control ience homicide increases than controls. The

nations, (2) the need for a prewar and difference between combatants and con-

postwar five-year period of peace and (3) trols, therefore, remains even when only

the absence of homicide data for some so- the best homicide indicator is used. The

cieties for certain periods. Despite these general conclusion, which seems justified

constraints, the effects of an additional 11 on the basis of these comparisons, is that

small wars can be assessed and the results combatants are more likely than controls

of this analysis are included in Table 2. to experience homicide increases.

Because of the large number of possible There were some combatants, however,

control nations for some of these wars, the which did not experience postwar in-

controls shown in Table 2 were selected creases. This suggests that some types of

as the closest noncombatant neighbors of participation are more likely to produce

participating nations. increases than others, as a number of re-

The results of this analysis are consistent searchers have speculated (e.g., Sorokin,

with those for World Wars I and II. The 1928).

nations participating in these 12 wars were In an effort to assess one dimension of

somewhat more likely to experience in- participation, we operationalized the degree

creases than were the controls. For com- to which participation was mortal for a

batant nations in these small wars, those nation-i.e., costly in terms of lives lost

with increases outnumbered those with in battle. We divided the combatant nations

decreases by eight to four. into two groups: nation-wars with more

The data in Tables 1 and 2 can be than 500 battle deaths per million prewar

pooled for an overall test of significance. If population and those with fewer than 500

Table 1 and 2 are superimposed, the dif- battle deaths per million prewar population

ferences between the 50 combatant nation- (Singer and Small, 1972). This rough

wars and the 30 controls are easily signifi- classification provides one way of group-

cant (X2=9.54, p=.0088). The same ing nation-wars according to the "amount"

result is obtained if the combatant and con- of war experienced by each.

trol nations are contrasted on the difference These two groups of combatants can be

between their mean prewar homicide rate compared. If changes in the homicide rate

and their mean postwar rate (Mann- are a function of the level of a nation's war

Whitney U= 1006.5, z= 2.55, p =.0054). involvement, then one would expect hom.-

As discussed earlier, it is important in icide increases to be greatest for the na-

comparative crime research to control for tions with the greatest losses. A compar-

differences in the types of indicators kept ison of the changes in the two groups of

by individual nations. For example, post- nation-wars is shown in Table 4.

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES 953

0 0~~~~~~~'

'~~~~4 c~~cd c

~~ '~~~ '~~~~'Z0 0 -4

c~o

co CPO,~~~~~

Z o0-

o ~~~~~~ b~~~~~~cIco e

0 ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ 0 k

0 ~~~~~~~~0

CU~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ .

0 '0~~~~ d

241 a L 'C 4 )

O eO. 0

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

954 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

The differences are in the expected di- the predictions derived from the seven

rection. Nations with large combat losses theoretical models discussed earlier. Al-

showed homicide increases much more fre- though a conclusive test of some models is

quently than nations with fewer losses. difficult, many of their predictions can be

This comparison is certain to understate inspected to see if they are consistent with

the actual differences between the two our findings or are disconfirmed by them.

groups. Nations with large combat losses

had greatly reduced numbers of young men1. Social Solidarity Model

and, if rates were available for men over One of the predictions of this model was

15, the differences between the two groups that homicide rates would decline during

would be even larger than that shown in wartime and then, at or soon after war's

Table 4. end, return to prewar levels. As the evi-

We interpret this result as an internal dence in Tables 1 and 2 indicates, this

validation since the nations most likely to explanation does not appear to be sup-

show homicide increases are precisely those ported: postwar homicide rates were gen-

nations which experienced the largest erally higher than prewar rates for com-

"amounts" of war. The analysis in Table 4 batant nations.

suggests an explanation for some of the

anomalous cases in Tables 1 and 2: nations 2. Social Disorganization Model

with only limited participation and losses in As discussed earlier, there are really two

war may not exhibit postwar homicide in- versions of this model. One suggests that

creases. any crime increases would be due to dis-

The effect of other dimensions of war ruptions all warring societies could exyer-

participation also can be assessed. For ex- ience: rapid industrialization, population

ample, nations can be compared on the movements, breaking up of families, etc.

outcome of the war. Combatant nations Since these social changes apply to most

were classified as victorious or defeated or all wars, this version of the model is

using Singer and Small (1972) and other not easy to test and may even be untest-

sources for more recent wars. Table 5 able. The second version of the social dis-

shows the effect of adding this variable to organization model predicts that homicide

the analysis in Table 4. increases would be confined to defeated

Both victorious and defeated nations ex- nations. This second version of the social

perienced homicide increases, although vic- disorganization model can be considered

torious nations were more prone to in- disconfirmed; as shown in Table 5, post-

creases than defeated nations. The results war increases were not limited to defeated

in Table 5 confirm our finding that wars nations and were actually more frequent

with heavy combat losses produce hom- among victorious nations than defeated

icide increases and indicate that these in- nations.

creases occur more often when these wars

are won than lost. 3. Economic Factors Model

In summary, combatant nations exper- An explanation derived from this model

ienced increases in homicide more often was that postwar increases if they occurred,

than control nations. This is the major would be a function of worsened economic

finding of this study. In addition, nations conditions. As a rough test of this explana-

with high battle deaths experienced hom- tion, we have compared homicide changes

icide increases more often than nations in two groups of nations: those with wors-

with fewer battle deaths. Finally, victorious

ened postwar economies (compared to the

nations experienced homicide increases prewar period) and those with improved

more often than defeated nations. The war postwar economies. We were able to find

most likely to produce an increased hom- prewar and postwar unemployment rates

icide rate, therefore, is a war which is both for only a portion of the nation-wars in

deadly and won. Tables 1 and 2. These nations were classi-

It is also possible to examine some of fied according to the direction of unem-

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES 955

~~~~~ _~~~~0 e

~~~~~~~4)~~~~~~~~P.

4)U%.-

'- IN

0 C-)~~~~~~~~~-o,%,

0~~~~~~1 c

o -~~~5c

- OU 0 v

0~~~~

cd~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~~~~'04~

4)~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~e

F-~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~0 ;

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

956 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

ployment rate change between the five pre-

N I I I 4)

war years and five postwar years. The hom-

icide changes experienced by these nations

are shown in Table 6, along with the

percent change in each nation's unemploy-

ment rate.

-~~~~~~~~~-

The results in Table 6 do not support

an economic explanation of postwar hom-

icide rate increases. Both nations with

4)

worsened economies and those with im-

proved economies experienced postwar

homicide increases. In fact, nations with

improved economies were slightly more

prone to homicide increases than nations

with worsened economies. This finding ap-

00 %n 0 00

pears to disconfim an economic explana-

N ~ 00e 1

tion of postwar homicide rate increases.

4. Catharsis Model

A prediction derived from this model

was that societies whose wartime exper-

iences had been the most violent would

experience postwar decreases in violent

crimes. This prediction appears to be dis-

confirmed by the results shown in Table 4:

nations with the most fatal experiences in

war were precisely those most likely to

show homicide increases.

CAA

5. Violent Veteran Model

A prediction of this model was that post-

war increases would be due to the acts of

veterans. Direct evidence of whether vet-

V 4

erans are overrepresented in the commission

of homicide is difficult to obtain, and re-

search on this question will not be re-

0

viewed here. However, we have found

some evidence that this model is not suffi-

cient to explain the observed increases.

Specifically, there is evidence that in-

CO~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~C

creases have occurred among groups who

could not have been combat veterans. Dur-

ing the Vietnam War, for example, U.S.

arrests for homicide increased dramatically

'4.4 ~ ~ CA0 4) C

for both men and women. The increases in

homicide arrests between 1963 and 1973

4) .~~ 4)'O. were 101% for men and 59% for women

(F.B.I., 1963-73, Uniform Crime Re-

ports). Homicide arrests also increased for

all age groups-including people over the

age of 45-as discussed below. For the

Vietnam War, therefore, this explanation

is inadequate since increases also occurred

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES 957

00 as en 00 eq VI wIt It

CN Ch - en

v 0 ch 0;

.0

.0

cq cN en v en C4 Go 'tt lr m cq W 00

cq

cd Cd >1 Cd Cd

Cd 0 , u 0 -cc

Iwo

z z

1.4

424

c

C

00

Am

4;

v

'o

0 0

z z Cd

12. >

z z 0

0

Cd .1-4

Cdw w

0

It

m 0

eq

Cd 0

Cd

o Cd

0

Cd

00

4)

w

Cd

0

0

0

I.C3 > 'd 0 0 0 0

C o C)

v C!

0 0 vvv

0 4Qu o 0,

0

o

t

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

958 AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL REVIEW

among people who could not have been nation-wars in the study; but there is also

combat veterans. evidence that this argument cannot suffi-

Evidence on this question also can be ciently explain even these Vietnam War

obtained for other wars. Although sex- increases. As shown in Table 8, U.S. hom-

specific data for homicide is not available icide arrest data, analyzed by the age of

for all nation-wars, it is available for sev- offenders, show that increases occurred in

eral. Data on offenses by men and women all age groups, not just the "baby boom"

in five nations after World War II were cohort.

published by the Commission Internation- All age groups in Table 8 show an in-

ale Penale et Penitentiaire (1951), and crease in arrests for homicide during the

data on an additional six nation-wars were Vietnam War. For example, the age group

obtained from our Comparative Crime of 25 or older could not have included the

Data File. Postwar changes in offense rates "baby boom" cohort until 1970. But as

are shown separately for men and women Table 8 indicates, the homicide rate for

for 11 nation-wars in Table 7. this age group as well as older groups

As Table 7 indicates, the postwar increased throughout the Vietnam War.

changes for women were comparable to The "baby boom" clearly did have an

those for men in these 11 nation-wars. effect on American homicide rates, as

Even if postwar increases do occur among shown by the increase in the number of

veterans, therefore, these increases are not arrests for those under 25. However, older

confined to them but occur among both cohorts also showed increases, indicating

sexes. The model of the violent veteran, that the "baby boom" argument is not a

while difficult to disconfirm, cannot be a sufficient explanation of U.S. homicide in-

sufficient explanation of postwar increases. creases in this period.

6. Artifacts Model 7. Legitimation of Violence Model

The major finding of our analysis runs Our findings are consistent with this ex-

counter to the effects of some artifacts. planation. This may mean either that the

Combatant nations experienced postwar in- model has some validity-that wars do

creases in homicide, despite large losses of tend to legitimate the general use of vio-

young men. The effect of this demographic lence in domestic society-or that we have

artifact seems to be masked or over- not identified a compelling and testable

whelmed by the size of the increases in prediction which can be derived from the

homicide these nations experienced. model. Merely showing that rival explana-

Another demographic artifact often cited tions are disconfirmed or insufficient does

as a factor in American crime increases not mean that the surviving theory is au-

during the 1960s (e.g., President's Com- tomatically the correct one. Although we

mission on Law Enforcement and Admini- have tried to formulate and test all the

stration of Justice, 1967) involves the theoretical models that seem suggested by

effects of the post-World War II "baby classical and recent discussions of the pos-

boom" on homicide rates a generation sible effects of wars upon violent crimes,

later. It is important to note that the "babyit is possible that an alternate explana-

boom" argument could not explain in- tion remains unseen. However, the legiti-

creases following any wars in our analysis mation model is the only one of the seven

other than Vietnam. In addition, only three discussed in this paper that is completely

of the six Vietnam combatant nations were consistent with our finding of frequent and

World War II combatants who could have pervasive postwar homicide increases in

experienced the maturation of a "baby combatant nations.

boom" cohort during the Vietnam War: If wars do act to legitimate violence,

the U.S., Australia and New Zealand. The it is interesting to speculate about the

"baby boom" could only be a factor in ways in which this effect could be medi-

these three nation-wars and cannot explain ated. Since this model suggests that the

homicide rate increases after the other 47 public acts of governments can influence

This content downloaded from

198.161.51.147 on Tue, 30 Jan 2024 19:56:31 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

VIOLENT ACTS AND VIOLENT TIMES 959

4_ W? - > tto N Os~ 0%

_,len XN

O cq en

e n lq "tW~om

ON oo ON wmwtw 6moe

0 oo en " t- lV4e 0;

9~~~~~~~W N6 , t N, { 0~O, M 4

N e V)00"14"1 t-M O e el 10

.~~~~~e l ^ t- t b- WI ON el t ^

"~~~~~~. I. I-- V. I .44 V--4 I- I- V- - 04

B O

" .o

on t Y o ~n en k 'R v-f 0 r- o r- 0 ON M o N B 0

O s u t O Ch O ~~~~00 00 04 - O DO WQ

t A38~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~t

.o A vD ^ b ? vD ? b vD ^. m oo o

e > t Y 0 t t Om eq " N tn eq F >q

co t.. t- 0 ; -,> C4 c ti W; N6 rW t- cq Noz

*~~~~~I

oo

00 0 v--l '- ' t- rnt % 0

o g r- W 0 kn '.o m m k o 6t ? t

o ~ ~~~~~~~~ c4 N en 't *- 10 VD 10 -- D bb I I 1 Z

_ W > > o o > OF o o o > o > > > o ^ ^~~~~~~~c