Sikhism For Modern Man

Sikhism For Modern Man

Uploaded by

ravindrasinghsainiCopyright:

Available Formats

Sikhism For Modern Man

Sikhism For Modern Man

Uploaded by

ravindrasinghsainiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Sikhism For Modern Man

Sikhism For Modern Man

Uploaded by

ravindrasinghsainiCopyright:

Available Formats

FOREWORD Sikhism For the Modern Man discusses the predicament in which modem man finds himself placed.

Numerous discoveries of far-reaching consequence, made in the fields of Natural Sciences and accumulation of vast amount of scientific knowledge during the last couple of centuries, had shaken mans faith in religious dogma. This is particularly so in respect of the genesis of the universe, its expanse and nature, which man had been taught to believe and marvel at. Various faiths have had their own fanciful notions on this account. Disturbed in his faith by new discoveries and prompted by material advancement in Science, the modem man sought to build for himself a kingdom of heaven on earth. This gave rise to different types of political systems each aiming at Utopia. But these advances too soon shattered his dreams and added to his frustrations. The author sees a retreat to religion as an inevitable consequence. It is in this perspective that the message of universal teachings of Sikhism has a special relevance. This work is being published posthumously by an arrangement made with the Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee who had originally sponsored the writing of this book by Sirdar Kapur Singh on the occasion of Indian Philosophical Congress held at Delhi University in January 1976. Though suffused with rather overladen expressions, the thought-content itself makes for compelling and diligent reading. The author lends evidence of fresh and original thinking. On many a subject touched upon by him, he stimulates further thought and research. I would also love to place on record my keen appreciation of the ready and valued cooperation the University has received from Prof. Kapur Singh's distinguished son, Dr. Inderjit Singh, Principal Economist, I.B.R.D. Washington, D.C., U.S.A. Guru Nanak Dev University Amritsar. (G.S. Randhawa) Vice-Chancellor

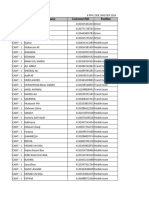

CONTENTS PRELIMS - Note from Sponsors of the Book - Editors Note - Key to Transliteration - Abbreviations CHAPTERS I. II. III. IV. V. VI. VII. VIII. Retreat from and Return to Religion Phenomenality of Sikhism The Heart of Sikhism The Sikh Thought Social Implications of Sikhism A Perspective The Axial Ritual Sikh Congregational Prayer Bibliography Doctrinal Index General And Bibliographical Index 1 23 81 102 130 145 158 175 181 186 188 (ix) (xi) (xvi) (xviii)

NOTE FROM SPONSORS OF THE BOOK The present publication is a monumental work of Sirdar Kapur Singh which interprets Sikhism in the background of crisis of conscience of modem man and, thus, simultaneously serves the cause of the Sikh Panth. Sirdar Kapur Singh accomplished the task of writing this book during his fatal illness and consequent upon that, he could not complete the manuscript in its finished form. Therefore, a certain scholar was assigned a duty to go through the manuscript and to write a preface to it. Later on, on the advice of some eminent scholars, it was decided to publish the book without adding preface or introduction to it. Furthermore, it was considered that writing an introduction to the seminal work of Sirdar Sahib would amount to an act blasphemous in nature. Page one hundred and eighty (p. 180), we found, was missing in the original manuscript. We did our best to trace the missing page but were disappointed. Consequently, we have left the said page blank expecting the scholars to supplement the matter through their independent intellectual exercise so as to complete the subject-matter in the context of the preceding paragraphs of the missing page. It would not be out of place to briefly describe the events and motivations that led to the writing and publishing of the present book. On January 1, 1976 University of Delhi held Indian Philosophical Congress at the Golden Jubilee Session of World Philosophy Congress to commemorate the sacred memory of Sri Guru Tegh Bahadur on the occasion of his Tricentenary Martyrdom Day. About four score scholars from various countries participated in the Congress. The speeches delivered at the Congress on the life and teachings of the Great Guru and his unique and exemplary sacrifices in defence of Mans Right to Freedom of Worship so much impressed the scholars that they asked for reading-list on the life and works of the Great Guru. S. Narinder Pal Singh, the representative of Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee presented a good number of sets of books to the interested scholars and delegates, but could not do much in this regard. He, however, promised that the literature on Sikh religion and philosophy would be made available to the inquisitive readers soon. S. Narinder Pal Singh, Information Officer of Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee, approached Sirdar Kapur Singh with the request to write a book on the subject. His request to Sirdar Sahib worked and the latter agreed to the proposal. The present work is the fruit of that effort. President Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee New Delhi

EDITORS NOTE On the recommendation of Vice-Chancellor G.S. Randhawa who happens to be a serious scholar of Sikhism and a great admirer of the erudition and insight into the writings of Late Bhai Sahib Sirdar Kapur Singh (formerly I.C.S.), the Guru Nanak Dev University Authorities (the Syndicate) sanctioned a research project for collection, scrutiny, compilation, editing and publishing of his works in a plausible form. Apart from Praraprana, The Baisakhi of Guru Gobind Singh, one volume entitled Guru Nanaks Life And Thought was brought out under the project after a good deal of incessant labour, raising the number of the series to two. During the execution of our project an intense desire grew in us to see if we could make Sirdar Kapur Singhs last but hitherto unpublished work, Sikhism For Modern Man, a part or adjunct of the series too. Designed to take full account of the Sikh thought, phenomenality of Sikhism and the development of Sikh self-identity in changing historical circumstances under the Turko-Afghan rule and the Mughal Empire in India, Sikhism For Modern Man, is an important new addition in the series, Selected Works of Late Sirdar Kapur Singh being published by Guru Nanak Dev University. It is a self-contained volume dealing with the interpretation of Sikhism in the background of crisis of conscience of modern man in the present context, led by the material advancement in science and technology but shaken in his faith and beliefs. The experiment of socio-political systems-Socialism, Communism and Fascism-too did not solve his problems. Horrified by the destruction caused by the two World Wars and the use of atomic energy, the modern man can, now, easily visualize probable apprehension of annihilation of, not only the human race but signs of all life on earth also in the wake of race for armaments and supremacy in power-politics. This disillusionment of man with Science and Technology and all the materialistic institutions and social systems built on its force had once-again taught him to look for composure and solace in the lap of religion. It is in this respect that the distinguished author explores the social implications of Sikhism and points out the significant perspective of the message of the Sikh faith as a universal religion. He visualizes in it all claims to be a modern religion, capable of meeting the deepest aspirations, the spiritual and secular needs of the mankind of today. Recalling the stunning advances made by scientists in macro and micro fields of the known and unknown universes, which have shown a remarkable unicity underlying the whole phenomenon, the author feels that modern man will not be satisfied and be at peace until he succeeds in creating for himself a cover having similar unicity towards which the emerging study of Comparative Religion is just one but a plausible step. The book Sikhism For Modern Man written in a compact form had been got prepared by the Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee on special assignment and was hanging fire in the drawers of some printing press at Delhi. We through our earlier experience of publishing Praraprana had sensed the difficulty the publishers and the printing press must be feeling in seeing the book through the press. We could gauge their difficulty, because we knew the amount of labour and the type of expertise the great Sirdars manuscripts needed for making them press-worthy from the view-point of the format. We therefore, with the blessings of our Vice-Chancellor, Professor G.S. Randhawa, approached the authorities of the Delhi Gurdwara Management Committee with the suggestion to entrust its publication to us in exchange for a number of copies, they wanted. To this they agreed, and we owe them thanks for this kind gesture.

Sirdar Kapur Singh, as will be clear to the readers, drew his material from a large number of sources. Sweep of his knowledge was, indeed, very staggering. Yet his method of documentation was very slipshod. He would, very often give incomplete information of the source he has used and at times would miss that much even. Then, he would sometime tuck it up in the body of the text and at times carry them in footnotes. The footnotes were sometimes marked with asterisks and sometimes with numerals. All this presented a very poor shape for this important treatise. We have, now, given it a homogeneous format by transferring as many references as could be possible to footnotes and have completed them with whatever information could be culled from different libraries and other sources. To authenticate references to texts taken from non-English sources, we have, along with their transliterations, added texts from their original sources i. e. Punjabi, Sanskrit, or Persian also and in doing so, we have corrected many quotes for which the author seems to have depended on his memory. Likewise, events and dates reported by the author have undergone scrutiny too. Our check up of the English Version of the Ards appearing in this book disclosed that a part of it covered by lines 2 to 5 of page 177 of this book, was missing. We have taken care to retrieve it from Sirdar Kapur Singhs Praraprana, the Baisakhi of Guru Gobind Singh, and, thus, remove the omission. Conscious of the difficulty involved in transliterating names and words from different languages, we have chosen the less incumberous path of noting them as easily understood in Punjabi and not by the typical scholar. For that reason Mujaddid-i-Alif-i-Sn appears with /s/ and not the sophisticated /th/. Likewise in reporting Sanskrit texts // has been preferred to, /ch/ which remains reserved for the Punjabi sound. For the sake of consultation a Key to Transliteration stands added to these prelims. Likewise a Bibliography as could be prepared from S. Kapur Singhs notes and texts, completed and supplemented by us from different sources, appears at the end of the text of this book. Conscious of the fact that this work may be used as a hand book for knowing what the great Sirdar had to say on certain specific subjects and concepts of Sikhism to the modern man, we have, along with a General and Bibliographical Index, added a Doctrinal Index too, which we hope will prove to be of great help to the keen reader and researcher, interested in Sikh studies and Indian Culture. We have refrained from repeating life-history of the author considering it to be unnecessary. The inquisitive reader may look for it in the first work of this series namely Guru Nanaks Life And Thought. We have come across a pamphlet which is entitled Postscript to Sikhism And The Modern Man. This deals with the problem of sex in the permissive societies vis-a-vis Sikhism. Evidently this was conceived as a part of the present work but either it was not completed, or was dropped as an afterthought deeming it to be unsuitable for a book of this nature. We have refrained ourselves from including it in this book considering it as a pious trust of the Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee. We, however, hope to give it in our next compilation of Sirdar Kapur Singhs Works. The title given to the pamphlet mentioned above suggests that the author had proposed to name his new work as Sikhism And The Modern Man. This was, however, changed by the sponsors to Sikhism For Modern Man at the suggestion of some reviewer. We have, with due

deference to their wish, retained it as such without even adding The to Modern Man, needed by it grammatically. Our acknowledgements are due to the Delhi Sikh Gurdwara Management Committee which conceded to our request to edit and publish this work. Thanks are also due to S. Inderjit Singh, Principal Economist, the World Bank, Washington U.S.A., for his co-operation and generous consent extended to us for undertaking to publish the complete works of his late father, Bhai Sahib Sirdar Kapur Singh. The editors would also like to thank Mrs. Vinod Duggal, wife of late Prof. Devinder Singh Duggal, who has generously placed at our disposal the photograph of Sirdar Kapur Singh from her family album to be printed in this book. Thanks are also due to the Director S. Jagjit Singh Walia and Publication Officer G.S. Marwah and others particularly Shri S.S. Narula, for coming to grips with the not easy computer technology involved in the printing of this book. Finally, we must express our gratitude to our colleagues of the Department of Sanskrit particularly Dr. K.L. Sharma and Dr. Shukdev Sharma, who have extended us considerable help in checking up Sanskrit quotes appearing in this book. Madanjit Kaur and Piar Singh

ABBREVIATIONS AG BG DG M [] () The di Granth / Guru Granth Sahib Bhai Gurdas / Vrn Bhai Gurdas The Dasam Granth Mohall Crochets show sound added to make the pronunciation conform to the modern practice. Parentheses indicate the sound which is not pronounced although it appears in the script.

CHAPTER I RETREAT FROM AND RETURN TO RELIGION When an intelligent person tries to comprehend clearly mans recent historical past of two or three centuries, he becomes aware of two well marked trends in the feelings and attitudes of mankind. One such trend is the expansion of the political and cultural frontiers and influence of the West beginning round about the fifteenth century of the Christian era. The other, an intellectual and emotional estrangement from religion as an organising principle of individual attitudes and human societies and a consequent idealisation of Science and Technology, which gains prominence from about the seventeenth century. A combination of these two has largely gone to make up, what we know today, as the modern world and the modern man. It was in the eighteenth century that the West began its movement of physical expansion, beginning with the discovery and domination of the so far little known surface of the globe, the new world, and a part of the well-known and recognised, old world by the restless seafaring and adventurous peoples of the West. The expansion impingement of one society into another is not a new thing in our history, but what is unique about the expansion of the modern west is that it has been literally world-wide, a thing which has never happened in the past. Previously, societies and civilizations had expanded but for want of sufficiently adequate means of communication, their expansion had been contained and limited. The expansion of the West, which we are considering, is unique in its ubiquity as being world-wide, and the means by which it has been possible for it to be so, have resulted in what may be called, the contraction and near annihilation of the distance that separates and confirms separate identity. It is this annihilation of distance that has made the modern world almost unique in history in terms of its impact on the social and spiritual planes of modern man. It is for the first time in the history of the world that this mutual impact and impingement of human societies and civilizations has become so assaultive and intimate, and so pervasive and contemporaneous. The other trend characteristic of our recent past is almost seen to be a marked retreat, revulsion, both sentimental and intellectual, from religion of the modern man. This phenomenon becomes obtrusively marked in the West, for the first time, after the Middle ages, in the seventeenth century, and this has had deep repercussions on the mind of the East from the eighteenth century onwards. The reasons for this retreat from religion in the West are different from those that pertain to the mind of the East. But this marked change in the feelings and attitudes of modern man in the West and East, both, is unmistakable. The reasons for this revolution or revulsion in the Western mind since the seventeenth century are two-fold, moral and intellectual. The moral reasons are traceable to the historical development of Christian institutions in the West. Certain events took place during the last two hundred years and more, which made sensitive and independent minds reject the institutional Christian religion, which to them was the Religion, as such. The main reason for this was the conflict between Papacy and the secular authority of Emperor Frederick II, which surfaced in the thirteenth century, the course of which conflict gradually projected the Papacy, the supreme repository and upholder of the Christian religion, as self-centred and worldly institution, unmindful of and unconcerned with its professed and proclaimed spiritual principles, motivated by naked desire for worldly power and basically moved by the sentiment of revenge against those who opposed its desire for political power, in as much as the Popes engaged in a persistent and malignant persecution of the heirs of their opponent, Frederick II. Again, when in A.D. 1305 a French Archbishop was elected as Pope, he chose to set up his seat at Avignon in France rather than at Rome in Italy, and, thus, for over seventy years, there was a line of Avignon Popes who were unwilling to move to Rome, which meant sacrifice of French luxury for Roman austerity,

with the result that in A.D. 1378, a new Pope at Rome was set up and thus, for a period, there were two popes leading to endless confusion in the common mans mind, loss of prestige of the established religion, and general decline in the faith of the people that encouraged rise of heretical doctrines. Besides, the French Popes were instrumental in the extermination of the order of Knight Templars at the instigation of the French king who wanted their property; and further, the second French Pope, Pope John XXII, built up a grasping and predaceous financial organisation to increase the papal revenue, since many would not recognise the Avignon Popes, which financial imposts were seen as disgustingly mercenary and commercial in character, such as the spolia, a right of seizure of the movable property of a deceased bishop originally belonging to his relatives, the tith, a ten percent tax made universal on all incomes except those of certain ecclesiastical dignitaries and functionaries, revenues from vacant benefices, visitation fees, proceeds from the sales of indulgences, fees for legal settlements or for special dispensations. The convergence of bankers, merchants, usurers and prostitutes who flocked to Avignon during this period to share in the loot, further added to the impetus towards a sharp decline of faith of honest people in religion. The split in the church called the Great Western Schism, which resulted on account of this double papacy, one at Rome and the other at Avignon, gave a very severe shock to the cause of religion, and the matters were not improved when in 1409, the Council of Pisa agreed that an Ecumenical Council, rather than the Pope, was the supreme authority in Church and then, it proceeded to depose both the Popes and elected a new one. But as neither of the old Popes would recognise his deposition, the result was, three popes functioning instead of one, as originally desired. This certainly could not have diminished the shock the peoples minds had received by the earlier events. Contemporaneous with these unedifying spectacles, there had arisen an intellectual movement, which was called Renaissance, the essence of which was an attitude of mind which regarded the principle of the Greek way of life and thought as an authority on human values, independent of Christianity. If Hellenism was valid independently of Christianity, it was necessarily in rivalry with the authority of the Christian church. This intellectual movement of regarding as something fundamentally valid outside Christianity and the Christian church, was further reinforced by certain scientific discoveries and speculations of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries which were in open conflict with certain dogmas of Christianity, particularly those pertaining to the Genesis. It was found that the beginning of the evolution of the world, as Science revealed through independent and un-biased observations, was in basic conflict with the account in the revelations of the Bible. It was for these reasons, in the main, that the Western mind felt a moral revulsion and intellectual distrust towards the religion which they had been, throughout the centuries, taught to believe as the Religion of their ancestors and, for these reasons, they also felt that the dogmas of religion were intellectually unacceptable. They further felt that the religious dominance of the West had led to nothing but social strife and unquenchable hatred. They saw further that this strife was motivated by nakedly sordid worldly objectives which had little to do with the high spiritual professions of Christianity. They argued and concluded that the Religion as such and of this nature, was a sham and a cloak for worldly motives, devoid of any genuine spiritual content, capable of nothing but producing blood-shed and mutual hatred amongst men. They, in addition, had perceived that the account of the origin of the universe and man, as given in the basic authority of the religion of their ancestors, was demonstrably erroneous, as being in conflict with the direct evidence of unbiased observation and speculation. The great pyramid of cosmology which had been built up by such great minds, as Saint Paul and Saint Thomas Aquinas, out of the elements of Jewish lore, Greek philosophy and Christian myths, no longer could command the assent of independent and intelligent minds. Both these revulsions, moral and intellectual, which took birth in the mind of the western man, reinforced each other and it is difficult to say whether the one or the other played the

conclusive role in finally alienating the sensitive and intelligent minds of the West from Christianity, the only form of religion which the West knew as valid. Since religion no longer held the central interest of the sensitive and intelligent minds of the West, their vast reservoirs of energy were diverted towards another channel, that of noncontroversial Natural Sciences. In the eighteenth century France, for instance, Diderot, in his Encyclopaedia, encouraged men to follow Natural Sciences in preference to Theology, for, the one leads to certitude and the other to mere controversy. As the data collected in respect of the Physical Sciences accumulated and the speculative thought based upon this data assumed more and more definite collections, the result was a progressive demolition of the dogmas of medieval Western Christianity, which had constituted the spiritual heritage of the West for the last 1500 years and more, and as a consequence the Western life was secularised. It is this movement towards secularisation which has given birth to the dominant political systems of the modern world, which swear by socialistic and regimented forms of society. The ancestral spiritual tradition of the Western man of the past 1500 years or so, had held before his mind the vision of a life of a far superior quality and abundance than the one he was leading on earth. This was the Paradise of the religion, located in the life hereafter. It was the Kingdom of Heaven that would compensate for all the ills and deprivations of the earthly life that had enthralled the soul of the Western man all these long centuries. Now that Christianity which was equated with Religion by the Western man, stood discredited as a way of life and as a system of understanding and insights, it appeared to him that although the Kingdom of Heaven was itself an illusion, a kind of paradise on earth was, nevertheless, a practicable possibility. The advancement in Applied Sciences had opened up a vista of tremendous technological progress which could make production of material goods possible in such abundance that no man may suffer for want of them. Thus, an economic reorganisation of society, so as to eliminate the possibility of exploitation of man by man, appeared as the obvious next step to achieve progressive satisfaction of material necessities of man. It was, as it now appears, somewhat uncritically presumed that full satisfaction of material necessities of man was the only precondition for the full unfoldment of the intellectual and finer potentialities of man. Socialistic abundance and communistic consumerism will raise most, if not all, men to the, moral and intellectual height, such as that of Plato and Socrates. Since this appeared to be a practicable and the loftiest objective, the Western man inferred mistakenly, as it would seem now, that this is the only desirable objective for man to pursue on this earth and that the means necessary for the realisation of this objective, therefore, stand in need of no further justification. That both these inferences are erroneous can now be seen. That it is these inferences and this line of thought which lies at the back of the political movements and systems which have engulfed the whole world of today, during the last fifty years or so, is also apparent. This movement of thought and the change in feelings and attitudes of the Western man during the last two centuries and more, resulting in the secularisation of life in all its aspects, has permeated into the Eastern societies also, and has gripped the mind of the intellectual minority of the Eastern man till it has become the chief motivation for social transformation in the East. Only very recently, in the Muslim world, in particular, there has emerged a visible painful reaction against stranglehold of Eastern cultures and societies by this alien secular sickness of human mind that has almost succeeded in banishing religion as the central organising principle of human life and societies.

The reasons that had led to this secular stranglehold on the human mind in the East, were not identical with those that had prevailed in the West. The technological inventions and the powers which they placed in the hands of the Western man were primarily instrumental in giving him economic and political dominance over the Eastern societies, apart from his superior organisational skills during the last two hundred years. The reactions this dominance aroused in the Eastern man were varied and confused. It was felt and assumed, particularly by those whose ancestral religion and culture were non-Judaic, that the superiority of the Western man was a necessary ingredient of his religion and culture, though disillusionment followed with the realisation that adoption of Christianity and the Western culture did not provide a sure key to the power which, in all cases was in the hands of the Western man. In the Islamic-Judaic societies the prestige and lure of the Western religion and culture remained inconsiderable, but the impact on the non-Semitic religions and cultures was, for a time, tremendous, although the keen minds even of non-Semitic societies were quick to comprehend that the homo-occidentalise subjugating the Eastern societies, was essentially a non- religious and unmoral species. To Dr. Wolff, who visited Lahore in 1832, Maharaja Ranjit Singh said, You say, you travel about for the sake of religion, why then do you not preach to the English in Hindustan? When Dr. Wolff repeated this to Lord William Bentick in Simla, the Governor General observed, Alas, this is the opinion of all the natives all over India.1 It was thus realised that the real source of power was not the Western religion which the West had itself discarded, nor the Western culture which was unmoral essentially, but that this power was grounded in the scientific knowledge and superior technology. It was after a painful process of trial and error that the Eastern mind came to cherish the distressing belief that the modes in which this power of technology and organisational skills was expressed and utilised, were, in some mysterious way, inseparable from the mental and physical habits of the Western man. For instance, it was realised that the superiority of the Western fighting soldier, through whom the West had established and through whom the West maintained its dominance, political and economic, over the Eastern societies, did not lie in his superior personal courage and physical powers of endurance over the Eastern soldier, but in the methods of training, the superiority of arms, and the techniques of his warfare. It was then discovered, again after a painful process of trial and error, that the Western methods of military training could be successfully adopted only by and in a society which has certain well-defined social bases; for instance, in a society based on caste, an army trained on European methods of discipline could not be properly raised. Again, the superior arm of the Western man were the results of not only a sustained scientific tradition of his racial history but were also the product of a certain attitude of mind, such as views the facts revealed by the physical observation as the only, or at least, the main aspect of what is real. The Eastern mind, thus, by a slow and painful process discovered that he could not shake off the humiliating domination of the West except by accepting and adopting his oppressors methods of military training and techniques of warfare. He further realised that he could not adopt these methods and techniques unless he changed the theoretical bases of his society which could not be changed unless he abandoned and discarded the fundamental postulates of his religious and spiritual traditions. He, in short, discovered that he could not compete on equal terms with the Western predator, his political master, unless he could compete with him in acquisition and practical application of scientific knowledge; and he realised, first with horror and then with resignation, that this was impossible unless his whole attitude towards life and his basic views on the nature of man and universe underwent a fundamental change. It was through this process, entirely different from the road followed by the Western man, that the Eastern societies have come to adopt a secularised version of life similar to that accepted and adopted by the West.

By the end of the nineteenth century and in the first decades of the twentieth century, we find that mankind had undergone a change and a metamorphosis, comparable to which there is nothing to be pointed out in the previous periods of history of mankind. This consists of the fusion of the various societies of mankind into almost a world and global society, if not in actual feelings, at least in nascent attitudes and aims. Such a world society, a global human society, had never been within the domain of possibilities in the past, though international Muslim society was a grand historical phase of organised and sustained efforts at setting up a monolithic, closed world society, such as was unheard of and inconceivable before the Communist phenomenon in the twentieth century. We also find that, at this period, this global society is not only physically continuous, such as is capable of inter-communication without impassable barriers, but also has accepted a secularised attitude of mind which, at least tentatively, regards the purpose of human life as somatic, mundane, as primarily centred on this planet, which we call the earth. This is the basic principle of secularisation accepted as the main, if not the only, standard by which human and social activity and progress is primarily judged by the modern man. It is in this context that the generality of mankind had deviated from a deep interest in the domain that belongs to religion, the domain of Numenon, as contradistinguished from the domain of the phenomena. The mankind has tacitly accepted, by this point of time, that what is worthy of the attention of serious and pragmatic sensible minds, is that which is revealed to the ten categories of the Smkhya, the jnnendriyas and karmendriyas, the five abstract powers of cognition arid the five physical sense-organs, lumped together by the West as the five physical senses, the information received, gathered through them, collected and formulated as the Physical Sciences, and that the only practical and rational acceptable ideal, which should animate and afflare the human society, is one which is grounded in the knowledge and reality thus revealed. In this context and in this climate of mind, religion has no significant place. But during the recent decades of this century, there has come to pass another revolution, as yet no more than an adumbration but, nevertheless, real in the minds of intelligent men, which is no less fundamental and all-embracing than the one already considered. It is this latter revolution in the minds of men, the men of the global society, the humanity of the whole world as represented by its keen, sensitive and intelligent minds, which has tended to arouse a new and intense interest in the values of religion and its revival, a reversal of the process of retreat from it in the preceding centuries. The reasons for this revival of interest in religion are, mainly three: The first, the movement of scientific activity and interest which started in the seventeenth century, and the speculative edifice which it built to explain the nature of man and the universe has, clearly and definitely, come to a dead-end, a cul-de-sac. The keen minds of men of science, throughout the world, and from more directions than one, have converged on to a single realisation that the scientific activity and the speculations based upon its achievements is necessarily incomplete and errant, and thus unsatisfying and that, therefore, something more and perhaps something altogether and qualitatively different, is necessary. To begin with, the basic postulate of the Physical Sciences is the principle of continuity, though there are, and always have been philosophers who believed that the world is a plurality; that it was composed of things essentially distinct. But the principle of continuity, that is, all distinctness must, at the base, arise from an all-pervading identity, is not only a fruitful

hypothesis of Science which has worked so well so far, but it also seems to be the very ground of what we deem as rational, the foundation of the web of human reason, the principle which the Smkhya, calls satkryvda, the principle that ex nihilo nihil fit, from nothing nothing can come out whatever is always is; and whatever is not, never is; the utterly different and distinct creation is unthinkable; only modification is there. When Einstein gave us E=mc2 explaining that Energy and Matter are substitutables, that is, matter is convertible into energy obeying a uniform law, he merely demonstrated the soundness of this basic postulate of Physical Sciences and when he refused to accept further scientific discoveries of Niels Bohr, Schrodinger and Heisenberg proposing that matter behaved both as particles and as waves, that within the atom this motion was governed by probability, that structure of matter was like a dice game decided by chance, he was not only being fanatical, opposing fact with faith, but was simultaneously subordinating science to religion by his credo and firm faith that fundamental indeterminism that relied on a throw of the dice simply cannot be the true structure of the Universe. I shall never believe that God plays dice with the world, he said. He did not succeed in constructing his unified field theory that would unite electromagnetism, gravity, space and time under one set of equations, but he did succeed in showing that science cannot prove conclusively that what it says is the final truth and that what the priest says is altogether trivial. Science cannot make religion redundant or invalid and nor can it otherwise shove it away. Whether, therefore, we postulate some rudimentary form of consciousness for the ultimate particles of matter, or postulate an initial dualism between mind and matter, this basic problem of nature of Reality bristles not only with unsolved but unsolvable problems and, in the ultimate analysis, the human nature and the physical nature remain enigmas, incapable of being accounted for, one in the terms of the other, and whether we accept the mathematico-physical aspect of the universe as ultimately real, or the mental aspect, our reason refuses to accept it so, simultaneously with its refusal to accept a plurality of principles as ultimately rationals. The recognition of the existence of the sub-conscious and unconscious levels of the human mind by the secular west in the recent years, has merely deepened this enigma of the nature of the ultimate Reality. Again, the scientific account of our universe appears clearest and most convincing only when it deals with inanimate matter, and that too it just appears so. Here the account appears as relatively satisfactory, because it, more or less, satisfies the kind of interest that we take in these phenomena. For instance, when we are told that matter consists of little electrified particles arranged vis-a-vis one another in certain ways, our curiosity about matter is largely satisfied. Or, when we are told the age, position, size, velocity and chemical constitution of a star, we feel that we have acquired the necessary scientific knowledge about this star. But, is the last craving of our curiosity on the subject finally set at rest there-by? In other words, has the ultimate truth about these matters been revealed to us by this knowledge? When Physical Science encounters these questions, it then admits that the only answer to these questions is in the negative, but it is forced to admit further that the methods of scientific investigation have their inherent limitations such as make science basically incapable of returning final answers on the nature of the universe and man. Not that the Physical Science has not, as yet, returned the final answers, but that in the very nature of things, it shall never be able to do so. This is so in respect of the sciences dealing with the inanimate matter, but the state of affairs is even less satisfactory as regards sciences dealing with life. Many of the questions that are quite fundamental appear to be unanswerable by science. What, for instance, makes us regard a living organism as a whole and not merely as an aggregate of its parts? There is this notion of wholeness or individuality and the logical trick employed by the Buddhist scholar, Nagsena, in his Malindapannha, of arguing that since a chariot is nothing but the sum-total of its parts, such as the axil, the wheels, etc., likewise all individualities, animate or inanimate, are mere aggregates, is not an ultimately satisfying answer. Even if every bodily activity of a living creature was explained in terms of physical and chemical changes, an accomplishment which prima-facie

appears ab initio impossible, our original question will still remain unanswered unless the purposive order of these changes, which obviously intrudes into the future, is asserted as either obviously misconceived and absurd or a mere tautology; that is, when we say purpose we merely mean to say, non-purposive existence, which is no explanation; it is a piece of affrontry. A true psycho-analyst introduces primary concepts which are non-technical and these concepts are far too vague and indefinite to be called scientific. To say that the most amazingly diverse manifestations of human conduct, all come about through the libido, whatever that may be, is to say nothing scientific. It is merely a vulgar paraphrase of the much more dignified and respectable statement that all these come about through the Will of God. Since the explanation seeks to explain everything, it, in fact, explains nothing. These predicaments of the Physical Sciences are inherent in the nature and scope of the scientific method, of which nature and scope were determined by certain historical causes. The founders of the scientific method, quite consciously began by deliberately abstracting and selecting from the totality of human experience, only such elements as possessed quantitative aspects. Later attempts, therefore, to make that method unravel and explain the totality of human experience, were bound to prove inadequate. Since mathematical relations subsist between those quantitative aspects of the experienced universe, it was assumed that Mathematics was the key to the ultimate secrets of the universe. Neo-platonism, containing important Pythagorean elements, which was prevalent in Europe at that time, reinforced this bias. The belief that Mathematics is the one true key to the secrets of the physical nature, has been well justified by the recent success in causing the atomic fission, though that is no good reason to suppose that only those elements which acquaint us with the quantitative aspect of the material phenomena are real, or more real, as the pseudo scientific outlook tacitly assumes. Nor, that such elements alone refer to the real objective world. It is a false and unwarranted assumption of science that our perceptions of colour, our response to beauty, our sense of mystic communion with God, have no objective counterpart, though this astonishing presumption has been tacitly made by men of science or the advocates of science, the protagonists of the materialistic outlook which, in the words of Bertrand Russel, means: Man is the product of causes which had no provision of the end they were achieving, that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and beliefs are but the outcome of accidental collections of atoms, that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave, that all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noon-day brightness of the human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of mans achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins; all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand.2 All these terrible and dismal conclusions were endowed with a certitude which was assumed to be the sole prerogative of the scientific method, and wherein, quite without any warrant, the real was identified with the quantitative, till recently when the science began getting self-conscious, and as the Sikh Scripture says, Suavity of speech and humility of conduct is the apogee of knowledge and virtue,3 and as T.S. Eliot has said, The only wisdom we can hope to acquire is the wisdom of humility, the men of science no longer teach that the scientific method of approach is the only valid method of acquiring true knowledge about reality. With enthusiasm that at first appears strange, eminent scientists now insist that science can give us but a partial knowledge of reality, and that the knowledge lying outside the domains of science is not illusory or in any way less real. It is ungrudgingly conceded now that exact science deals wholly with

structure and not with the nature or attributes of the phenomena. This concession which the science now willingly and even with a positive show of enthusiasm makes, has far-reaching implications in respect of the subject of religion, for, it means that the nature of reality is not prejudged, the science no longer requires us to believe that our response to beauty or the mans mystic communion with God, has no objective counterparts. It is perfectly possible, so far as science is concerned that they are, as they are claimed to be, genuine clues and visions of reality; and science is no longer in a position to contest the claim that these clues constitute better awareness of the reality than that revealed by the scientific method. It is, thus, revolution in the thoughts of intelligent minority of the modern mankind that has turned the scales in favour of a deep and significant revival of religious interest, the magnitude of the results of which revolution will manifest fully as the present century closes. The second reason for the revival of interest in religion is that secularisation of life has led to political theories and systems which have thrown up organisations of society, the basis of which is progressive and all-inclusive regimentation. The state, as the embodiment of the spiritual yearnings of these societies, finds it necessary to acquire and exercise more and more and growing control over almost every activity of individuals life till no real personal freedom of any kind is left to the individual. This is not merely the reality of modern political systems and societies but is also me logical outcome of the postulates on which such societies are based. If a state has to be socialistic, it must exercise control over the labour activities of its citizens. If it is to be a welfare state, it must have the power to control and regiment the resources, the whole of them if necessary, physical and mental, of its citizens; and, thus, the State tends to be truly totalitarian, not merely by the logic of necessity, but by the inner dynamics of its postulates. It is not only that practical considerations make it necessary for the state to control its citizens in almost all aspects of their lives, but also, it is a logical outcome of the theories of the nature of the world and the significance of individual life in it, which these societies accept as fundamental. There is, therefore, no substance in the hope or promise that this all-inclusive and total regimentation of man is only a transitory phase, a necessary but passing evil. On the other hand, this regimentation is inherent in the very theoretical bases of such societies. In a welfare society, the area of freedom of the individual must be progressively restricted, till it almost vanishes into a zero, as the quantum of welfare granted by the state becomes ampler and ampler. This then is the fundamental inner contradiction of all socialisms. Though the initial motivation in the theory of Socialism is the abolition of the exploitation of man by man, its dynamism is a regimentation, but the only purpose which direction and regimentation might arguably serve, are the purposes of war, and not of peace and progress. Again, its reality in the world, no where has achieved its aim without converting the entire community into slaves and without creating a privileged class to run the socialist state machine. Further, socialist experimental experience shows that tremendous material progress is compatible with an oppressive system of rule and complete denial of social justice. Industrial and technological advance, and even cultural progress, do not per se, bring about social justice, though it might be argued that they constitute a starting point for its attainment. Faced with this predicament and confronted by these necessary and progressive restrictions in the area of individual freedom in relation to physical and mental planes both, keen and sensitive minds have realised that in this context the only field of freedom which is capable of being left intact is the primary concern of religion. The third reason, the fervent reliance on technology which was believed to be a panacea for all human ills, capable of ushering in a new era of limitless, abundance and unalloyed happiness for mankind on earth, but in itself quite neutral and innocuous, incapable of generating strife and hatred as the religion had done in the past, has belied these high hopes. In the year 1979 the main concern of sensitive human minds is not how to encourage continuous

advancement in technology, but how to control the devastating consequences to which it can and may lead the mankind. The main problem today is not how to ensure further advancement in the use of the vast atomic power harnessable, but how to control it so that it does not result in the annihilation of mankind. Technology is no longer a harmless and beneficent power, from the progress and advancement of which nothing but the good can result to man. It is now seen as one of the deadliest and the most evil of forces that has ever been let loose upon earth in the history of mankind. As in the case of the djinn in the Arabian Nights, the best place for it was to lie corked up in the bottle at the bottom of the sea instead of being uncorked out in the open, and it will be an act of deep wisdom to cork it in again before consigning the magic bottle to the place from where it was unwittingly dragged out. The alternative progress of making peaceful uses of it, are fraught with dangers unlimited, till human nature itself is first transmuted and reintegrated. This has led the sensitive enquiring minds to cogitate that there must be some other set of values to which the values of science and technology must be subordinated and they have awakened to a growing realization that unless these values are discovered and truly comprehended, there are no means of saving mankind from almost certain annihilation. There is another orientation of thought, now assuming shape in the disquietude filled human mind which, though indirectly, is bound to lend support to a deep revival of human interest in religion and it is the modern philosophic outlook. Until the end of the nineteenth century, Philosophy was primarily concerned with attempts to devise a systematic schemata whereby all existence could be explained. Platonic Idealism and Marxist Materialism are the two polarities of this trend. In the beginning of the present century, there came about a sort of general agreement that these system-builders were wrong basically, for, it was argued, our knowledge can never become complete enough for there to be an all-embracing explanation of man and the universe. There, thus, grew up a school of philosophers who held that all metaphysical speculation rested on a basic error, an error which supposes that there can be true proposition about something which is over or beyond all experience, and that, therefore, the proper and legitimate task of philosophy is logical analysis, they asserted. These logico-linguists avoided discussing the problems such as those of freedom and absolute values, without clearly realising that thus, by implication, they were making a metaphysical statement in so far that they seem to assert that these problems are unreal. If all can be shown to be senseless by the method of logical analysis then what about the propositions of this logical analysis itself? No sooner this question was seriously raised, its implications were not long in being perceived. Wittgenstein (1889-1951) agrees that, The result of philosophy is not a number of philosophical propositions but to make propositions clear,. . . My propositions are lucidatory in this way: he who understands finally recognises them as senseless, when he has climbed out through them, on them, over them. (He must, so to speak, throw away the ladder after he has climbed on to it). He must surmount these propositions; then he sees the world rightly. Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.4 This last sentence might well have been taken out of the sayings of a religious mystic. The result of this development of philosophic thought is that it is not conceded that Metaphysics is the truest form of philosophical speculation, and that philosophical activity satisfies a genuine and basic hunger of human mind, the fundamental curiosity as to what is the nature of man and universe, how are they inter-related, and how this inter-relationship may best be adjusted. This last limb of this implicated concession brings mans mind straight into the fields of religion and the philosophical trend out of which this concession stems is favourable for, and fertile to, the revival of a genuine and deep interest in religion.

These three main reasons and the fourth subsidiary reason that, there has come about an earnest search for a world-view which besides satisfying the highest and the deepest quest and curiosity of man is also capable of operating as a ferment for a peaceful advancement towards evergrowing prosperity and happiness of all the men on this earth, knit into a global society, imbued with a variegated plural universal culture, that have fixed the human focus on religion today. Apart from these four there is yet another and fifth circumstance of a general and negative character which is more than likely to give a new stimulus to the revival of a wide interest in religion. A new generation, grown accustomed to the achievements of science and technology, is more likely to be impressed with what science cannot do than with what it can, and thus their minds will inevitably turn towards religion as of supreme interest. The annihilation of distance and the consequent emergence of a de facto global society has made this earnest yearning of mankind, at this moment of its history, for a religion which is available to all castes and colours, all races and nationalities, not only urgent but also such a hope and yearning that seems more capable of actual realisation today than it ever has been the case in the history of the world before. In this context, an acquaintance with the outlines of the origin and history, doctrines and tenets of the Sikh religion is desirable, for this religion not only professes to be an ecumenical religion, available to all men without discrimination but also claims to be a modern religion capable of meeting with the deepest aspirations, the spiritual and secular needs of the mankind of today. The fact that this religion was founded in the fifteenth century when the historical development towards annihilation of distance that has made possible the emergence of a human global society possible and imperative, that it was finalised in the seventeenth century when the modern scientific outlook and activity assumed a definiteness and finitude, both of which factors have led to the rise of problems that have now resulted in the revival of interest in the religion as, perhaps, the only hope of mankind, may not be merely fortitutous or accidental. Footnotes: 1. Joseph Wolff, Reverend, Travels and Adventures, p. 375. 2. Bertrand Russel, Religion and Science. 3. mitthat(u) nv nnak gun changi [n] tatt(u). (imTqu nIvI nwnkw gux cMigAweIAw qqu [) M 1, AG, 470. 4. Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

-Var

Asa,

CHAPTER II PHENOMENALITY OF SIKHISM In the preceding chapter were named some reasons for mans retreat from religion during the last two centuries and to certain recent trends in the domains of Physical Sciences, the realities of political systems, and the dead ends into which analytico-linguistic philosophical speculations have reached, that tend to stimulate return towards religion. Mental energy which this retreat from religion released in the West, was primarily turned towards Natural Sciences, but the very methodology of these Sciences provided man with new tools for studying the history and phenomena of religion as such, and the methods of approach and the results obtained thereby are likely to mould and influence the direction of this newly awakened interest. It was the German philosopher, Hegel (1770-1831), who dominated the philosophical thought of the West during the nineteenth century. His assumption that the essential nature of the movements of human thought resembled vertical crawling of a snake wherein the first movement constituted the thesis, and the second the antithesis, the opposite of that assertion, and the third movement, the synthesis, in which both the first and the second movement were amalgamated. Hegel saw this basic characteristic of human thought as the essential nature of all movement of Reality, whether physical or mental, and he built his metaphysical system and his interpretation of human history this wise. This methodology of speculation is still the basis of, what is called, the Materialistic interpretation of History, and the Communist systems of thought, currently dominating a large part of the political globe. It was Hegel who made the assumption, unwarranted as is now demonstrably clear, that an Age of Magic preceded the Age of Religion. He asserted that in the History of mankind, there were periods when ancient and primitive human societies were preoccupied with magic as their sole theory and activity of their understanding and adjustment in relation to the universe. Magic is a theory as well as a practice. The basic idea underlying the theory of magic is that the processes of Nature can be strictly controlled by man through spells and incantations. This theory is as old as the Vedas and is still held by the widespread tantrik practices in most parts of India. The practice of magic depends upon the way in which certain things are done and said for a given desired purpose by those who have the necessary knowledge and power to put the relevant supernatural force into effect. The specialist in this practice is the medicine-man or the magician, equivalent to the purohit of the vedic sacrifices. Sir James Frazer, in his famous book, The Golden Bough, and his other work, the Worship of Nature (1926), tries to uphold the theory that a time existed when man believed that they could coerce the forces of Nature to do what they wanted. He supposes that it was when this belief was no longer found as pragmatically sound that the Age of Religion dawned. Religion presupposes the existence of spiritual beings, external to man and the world around him, and that it is this spiritual Being or beings who control mens affairs. These beings cannot be coerced or dictated to, and the proper method of approach towards them, therefore, is that of supplication and prayer. This is essentially the difference between magic and religion, that while magic is coercive and dictatorial, religion is supplicatory and propitiatory. Archaeological and sociological studies which have been conducted on a vast scale in the recent past, however, have yielded ample data to confirm the fact that magic is not related to religion chronologically, and that both existed simultaneously in ancient times, as they still do in modern times. The priest of religion, is not a lineal descendant of the magician, as Frazer had thought, and nor is religion the sequel to ineffective magic. They are both distinct activities, and mostly simultaneous, in which man indulges to achieve similar or identical objectives.

Sir R. B. Tyior (1832-1917) in his great book. Primitive Culture (1871), rested the entire structure of his history of religion on what he called Animism. His theory was that animism was the essence of religion, the minimum definition of religion, as he called it, the final source from which the whole paraphernalia of religion has developed. His argument was that from observation of such phenomena as dreams, trances and visions, man had transferred to the natural order, the sun, the moon, the stars, the trees and the rivers, a concept of animating spirits whereby these natural objects perform their functions in the universe like men and animals. In this way, as Sir James Frazer put it, man had located in every nook and hill, every tree and flower, every brook and river, every breeze that blew and every cloud that flaked with silvery white, the blue existence of Heaven, a spirit such as he believed animated his own corporeal frame. From this notion, man advanced to the stage, when eventually from these innumerable spirits, a polytheistic system of gods emerged which controlled the various departments of Nature. For instance, instead of a separate spirit for every tree, there was supposed and conceived a god of Woods in general, and similarly a god of the Wind with a distinct character and features. From this polytheism to strict monotheism is only a logical step. Sir Herbert Spencer (1820-1903), a speculative philosopher, who has exerted much influence on the thought of the second half of the nineteenth century, believed and argued that the idea of God and religion in general had originated from the theory of ghosts and the practice of the worship of ancestors. He attempted to demonstrate that the root of every religion was in the worship of ancestors, which ancestors, after death, were believed to live in the form of ghosts and which later on were deified. Since these ancestors were regarded with awe and reverence during their life-time, they were apotheosised after their death, and consequently a complicated system of worship developed. This, he thought, was the whole story of religion. This speculation was in line with the evolutionary thought which dominated the nineteenth century and this mode is still there in the popular mind and literature of today, although the evidence which has been painfully accumulated since, refuses to fit in with this theory of the origin of religion, as Andrew Lang, in his book. The Making of Religion (1898) was believed to have shown. There has been, as the irrefutable data now shows, no unilineal development from animism to polytheism and to monotheism, or from illustrious mortals to deified immortals. The argument behind all such speculations was twofold: The first, that there has been evolution in religious thought i.e. there were certain phases of religious thought which were chronologically anterior to certain other phases; and, the second, that, these so-called later phases were, therefore, superior and higher than the former phases, it being a postulate of the Theory of Evolution that the later in time is qualitatively superior to the earlier. It is this kind of speculation and argument which has occupied the minds of intelligent men during the last one hundred years or so in respect of religion, but it is now no longer dogmatically held that both, or either of these two propositions, are self-evident or demonstrably true. It is not correct that, in fact, certain phases of religious thought and practice, such as magic or ancestor-worship, preceded, in the history of human society, the other phases. Viewed chronologically, they are often found to be simultaneous, and they run along side by side with each other. Secondly, it is fallacious to argue that chronology is a spiral measure of value. To argue that because ancestor-worship precedes polytheism, therefore polytheism is a superior religious practice

to ancestor-worship, is a fallacious argument. That one is superior to or more excellent than the other, depends not upon whether its chronological origin is earlier or later. Its mode of assessment is quite different and it consists in a certain power of perception of quality, of evaluation, which forms the part of a properly developed, trained and a cultured mind. To argue that the origin of a thing determines its value, is the naturalistic fallacy. It is a fallacy which wrongly supposes that the value of a fact is dependent upon and is determined by its origin. Whatever, therefore, may be the hang-over of these nineteenth century speculations and modes of approach in the popular mind of the uninformed, the intelligent minds have already perceived clearly that a true understanding and appraisal of religion can only be achieved through the interior religious experience itself and not through the discipline of other sciences and philosophy. This realisation has been made possible in the recent years, firstly by the analytical thought of logician and philosophers such as Dr. G. E. Moore, who in his Principia Ethica clearly explains the nature and implications of what has been called the, naturalistic fallacy, and it was Dr. Otto, who in his The Idea of the Holy (1928) clearly showed that the core of religious experience consisted of an awareness of non-moral holiness as a category of value, which was quite distinct from the aesthetic and the moral experiences. This category of value he called numina i.e. a spiritual experience of reality peculiar to religion. It is this numinous experience which is the core and base of religion; and its ingredients, awe and reverential wonder, abound in a religiously sensitive mind in relation to his apprehension of himself and the universe around him. This word numina is etymologically related to the Samskrit word nman, the English word name. Its antonym is phenomena. Phenomena is that which appears as reality to the sensory motor apprehension of man, precisely the subject matter of investigation of Physical Sciences. Numenon is that which lies at the root of the phenomena and which causes and supports the phenomena but which is not discernible either through sensory motor apprehension or even through speculative processes grounded in the data of the sensory motor apprehension. They are not these, but other eyes, with which my Beloved may be seen, says Guru Nanak the Fifth.1 In other words, what the Physical Sciences investigate through observation and controlled experiment is all phenomena. The theories which the Physical scientist subsequently builds to explain the data which he thus collects is also phenomena-grounded. This data and these theories are both like-wise phenomenal and they, therefore, pertain to a category of reality which is not the subject matter of religion. The presupposition and basic postulate of all great religions is that this category of reality which the Sciences investigate into and speculate over, is illusory and not real and that the ultimate Reality is something which lies at the base of all phenomena, which is numenon, about which the Hindu Brihadrnyaka (III. 2. 12) says that when a man dies, what does not foresake him, na jahiti, is his numenon, nman. It is this that is meant when it is said that the ultimate Reality is numenon and that numenon alone endures. The numenon alone endures, as the essence of the purified soul, as the divine light in the heart of man, and as the God of the Universe. Nanak (approves of him) who holds steadfast to this Testament of the Guru, while actively operative in the vista-scope of the phenomenal forms, that the numenon, as explicit in the Self-realised man, as the Light and Guide of mankind and as the God Almighty, alone endures.2 The real subject matter of all true religious activity is the apprehension of or an attempt to establish contact with this numenon, and the true religion tempts the man with nothing less than the vision of this ultimate Reality. Put thus there is no real antagonism between Science and Religion, as religion implicates an activity which is independent of scientific activity and relates to a category of

experience which is neither confirmed nor falsified by whatever the scientific discoveries or speculations may reveal or establish. Sikhism is essentially, and more than anything else, the religion of the Numenon, and throughout the voluminous Sikh Scripture, consisting of approximately 30,000 hymns, there are not many hymns or pages of this Book, where it is not asserted and brought home through repeated statements, literary similies and allusion, that the essence of true religious theory and practice is the Name: There is nothing comparable to the Name in all religions.3 The Congregational Prayer of the Sikhs ends by fervently beseeching God to grant progressive prevalence of the Religion of Name, preached by Nanak.4 It is in this context that the historical epiphany of Sikhism is of interest to the modern man. Sikhism is not a history-grounded religion, i.e. the truth and validity of Sikhism does not depend upon any event that has occurred in History, as is the case with certain other religions. Islam, Christianity, and Judaism, all maintain and proclaim that there is, in their possession, a special and unique self-revelation of God through their own divinely appointed channels. It is a matter of history that the Nazarene Jew who is claimed as the Christ of God, or Abul Qasim who became The Praised One, Mohammad, and who is asserted as the prophet of Allah par excellence, or Moses, to whom God spake directly through a burning bush, appear as historical individuals. If, in fact, these special channels of the revelations of God did not exist in history, as is claimed, and are only myths or fictions, then the whole basis of the claim of these religions that their dogma carries its own validity with it, falters and falls to the ground. This is a point of strength in these religions in so far as it guarantees to them an element of psychological certitude and a historical continuity. But it is a weakness in so far as it binds these religions to a pre-determined interpretation of the reality. Thus, the Christian theologians would normally start with the postulate that there can be no advance on the Revelation, which is already fully given in the life and teaching of the Christ as the Son of God. The whole task of the Christian theologian is to render what has already been revealed, more explicit. The Muslim and Jewish theologians would proceed on similar lines in respect of their final terms of reference. Similarly, though in a somewhat different way, their Hindu counterparts in India, are circumscribed in respect of their final terms of reference in the form of the Veda which, though not conceived of as a self-revealing living God in the Western sense, nevertheless, is postulated as eternal and complete revelation of the final Truth. Sikhism, on the other hand, makes no such well-chiselled claim or any such draconian assertion. It merely asserts the following three simple, though fundamental, propositions: (a) That the ultimate Reality is not comprehensible through the sensory motor perceptions or pure speculations of thought; (b) That this ultimate Reality is continuous with and partakes of the religious experience of the numenon, which experience is the matrix of other values of Truth, Beauty and Good, and which experience is implicit in and inheres in the universal human religious consciousness. (c) That there is a way of cultivating and making explicit this consciousness of the numena such as leads to the vision of God. The founders of the Sikh religion have merely asserted that there is a technique and there is a discipline, which is called the Practice of the Name in the Sikh Scripture, which is more suitable and

efficacious for achieving this vision of God than others in the present Age and in the current mental climate of mankind. There is no other claim which Sikhism makes and there is no other dogma which it asserts as basic to its teachings, and in a way, therefore, the time-point of the epiphany and the historical origin and growth of Sikhism is not strictly relevant to the truth or validity of Sikhism. The epiphany and the history of the Sikh faith, however, is of interest in another respect. In recent years, in Europe, a school of thought has arisen which goes by the name of Phenomenology, the study of the development of the human consciousness and self-awareness itself in abstraction from any claims concerning existence. Its adherents seek to determine the meaning of what has happened in history on the presumption that all knowledge is phenomenon and all existence is phenomenal. They have adopted this term from Edmund Husserl (1859-1939) who inaugurated a philosophy which is passionately interested in the tiniest details of experience as providing a clue to art, law, religion, history and all other aspects of the Universe. Husserl insists that philosophy which he calls Pure phenomenology, is distinguished from all empirical sciences in its peculiar method which, though not easy to expound, is a form of intuition concerned not with the appearance of facts but with their essences, forms or structures. These structures are not the perceived aspects of things or the ideas of them; they are obscurely akin to the Sambhogky of the Triky doctrine of the Mahayana Buddhism, and intuitive prehension of these accounts in the historical events and human experiences is stated as the true task of philosophy to be accomplished through an intricate process of phased perception, analysis and meditation, called presuppositionless method, an exposition which remains somewhat obscure even in the texts of Husserls Ideas, General Introduction to Pure Phenomenology. When, however, this term, Phenomenology, is applied to the investigation of the structure and significance of religious phenomena, independently of its setting in a particular culture or at a particular time, it is used in a somewhat different sense from that of Husserl. The method employed is to collect material from all ages, states of culture and parts of the world without laying stress on chronology, environments, function in society or validity. That what appears, i.e. appears as a phenomenon, is collected and correlated for the purpose of pure description without making any attempt to pass a judgment on it. Since God does not fall within the purview of the presuppositionless method either as a subject or an object, a phenomenologist would describe it as beyond his scope of enquiry. This, he would say, is the business of theology and not philosophy, as his sole aim is to understand the religious fact as it appears to the religious man and as he reacts to it. It is, thus, a method of enquiry to assess the meaning and significance of religious phenomena; and Phenomenology, therefore, concerns itself with the study of the history of a religion for its material postulating that this study of history of a religion is itself conditioned by the results of historical research and, as such, the inner religious experience, and the outward manifestation of the phenomena are really complimentary aspects of the same whole and discipline. It is on the basis of some such approach that Malinowsky, B. in his Magic, Science and Religion and other Essays, concedes that, The comparative science of religion compels us to recognise religion as the master force of human culture. Religion makes man do the biggest things he is capable of, and it does for man what nothing else can do; it gives him peace and happiness, harmony and sense of purpose; and it gives all this in an absolute form. It is in this context that a birds eye-view of the history of Sikhism is of special interest. Sikhism was founded by Guru Nanak (1469-1539), who was born in that part of the Punjab which is now in Pakistan. His nine Successor-Nanaks (1539-1708) exegetised, developed and