Archaeology of Kiev

Uploaded by

NikArchaeology of Kiev

Uploaded by

NikThe Archaeology of Kiev to the End of the Earliest Urban Phase

Author(s): JOHAN CALLMER

Source: Harvard Ukrainian Studies , December 1987, Vol. 11, No. 3/4 (December 1987),

pp. 323-364

Published by: Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41036279

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to Harvard Ukrainian Studies

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Archaeology of Kiev

to the End of the Earliest Urban Phase

JOHAN CALLMER

I. INTRODUCTION. SOME METHODOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

There are two kinds of source material available for the study o

development of Kiev in the earliest urban phase. First are the w

sources, which provide us with so much valuable and unique informa

These must be studied together with the source criticism and accordi

the philological methods the material calls for. The contemporary wr

sources and the later written sources based on contemporary notes are

narrow in scope and restricted mainly to the personal and state histo

the Rurikid dynasty, short geographical and historical notes by M

scholars, and one rich and a few less informative Byzantine sources.

number of these sources will probably not grow considerably.

The second source base is archaeological material from surveys

excavations and from stray finds. These must be treated with m

developed by archaeologists. Archaeological sources, generally spe

can say something about the chronology of sites, the character of se

ments, economic specialization, the social structure of the popul

exchange systems, and to a certain extent beliefs and some other asp

Seldom can archaeology contribute directly to the illumination of hist

problems. Indirectly, however, archaeology is of great importance fo

torical processes beyond the periods and areas covered by written sou

Of course, the written sources of medieval history and the archaeolo

sources give us answers to very different questions (Callmer 1981, p.

It is often difficult to combine them and to evaluate them in relation to each

other. This is, of course, an elementary remark but it is also a point of

utmost importance for the scholarly study of Early Medieval Eastern and

Northern Europe.

To judge from the literature on the early development of Kiev, argu-

ments from written sources and arguments from archaeological sources are

often woven together into theories difficult to comprehend. This is not to

deny that both kinds of sources are necessary to solve the problems of the

development of Kiev, but it is obligatory that philologists and historians

make their analyses and and that archaeologists reach their conclusions

independently (or as independently as possible). Only if this procedure is

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

324 JOHAN CALLMER

strictly followed is it fruitful at

results. A synthesis is only possible

characters of the source materials. We now turn to a consideration of the

archaeological sources and their implications.

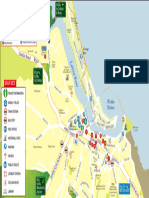

II. THE LANDSCAPE OF KIEV

The geographical position of Kiev is a central one. It is situated on

Dnieper, Europe's third largest river, ca. 10km (kilometers) downst

from the confluence of the Dnieper and its major tributary from the east,

Desna (fig. 1). As is often the case in this part of Eastern Europe,

river's west bank is high, with steep slopes cut by many ravines - jary

balky - in a pattern resembling the veins of a leaf. The riverbed itself

more than two kilometers wide at Kiev, and there are numerous islands

shifting banks and shallows in the river due to the masses of sand that

transported downstream during spring and autumn. Today the Dnieper

main artery is ca. 500m (meters) wide at Kiev. By contrast, the river's

bank is very low and marshy, and rises only slowly.

Kiev is situated on a plateau, ca. 3km long and ca. lkm wide, cut

from the major portion of high ground between the Dnieper and the Irp

Rivers. The latter flows from the southwest towards the northeast and

the Dnieper ca. 30km north of Kiev. The valleys of the small Lybid

Syrec' Rivers are the boundaries of the Kiev plateau to the west and to

south, with the Dnieper to the east and the Pocajna River to the north

The Kiev plateau is divided into a number of distinct parts by numero

ravines. The ravines usually run at right angles to the main rivers, wh

are orientated more or less north-south. As a consequence of the w

developed system of primary, secondary, and even tertiary ravines, the

a large number of promontories with excellent natural defenses; these n

only minor man-made complements to become first-rate, secure habit

sites. The ravine system as it exists today is to a certain extent the resu

rapid erosion, which in turn is a consequence of successive (and now alm

complete) deforestation and exposure from the tenth -eleventh centur

onward. The essential character of the landscape is, however, unchange

The Kiev plateau or, as it is often called, the Kiev hills stand up to ca.

meters above the Dnieper. The subsoil of the hills is loess on clay, and

river valley is composed of sand and clay. The natural vegetation is a le

forest with a dominance of oak. Maple, elm, ash, aspen and lime are als

components of the natural forests in this part of the East European w

land region.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 325

Traditionally, the Kiev area is divide

The northern part of the Kiev plateau, w

hills of St. Cyril. Further down, toward

divided by a deep ravine where the Jur

from the plateau land stretches for m

Luk"janivs'ka Hill. The hill's western bou

flows in a semicircle towards the Dnieper

this northern part of the Kiev plateau i

Hlybocycja brook, which runs almos

southeast of the Kiev plateau is its centr

tories facing the Dnieper. Furthest to th

by the much smaller Dytynka Hill a

Starokyjivs'ka Hill. To the north of thes

the Hlybocycja lies the Kyselivka Hill, c

plateau as a result of water activity. The

part of the Kiev plateau is the Xrescatyk

runs towards the northeast. The valley f

the end of the Xrescatyk ravine is th

downstream, on the west bank of the Dn

row. To the north of the Jurkovycja th

Both the Jurkovycja and Hlybocycja broo

baylike tributary of the Dnieper.

To the south of the Xrescatyk are th

Monastery (Uhors'ke) and Vydubyci fur

divided from each other by ravines with

Lybid' River. On the west side of th

northwest to the southeast, is a new succ

the dominating Batyjeva Hill

Although the Kiev plateau today is par

the wooded steppe zone begins not far s

A.D., the border between the two zon

further south.

III. SETTLEMENT IN THE KIEV REGION

BEFORE THE END OF THE NINTH CENTURY

Due to the favorable geographical situation, human settlement in the Kie

region goes back to the Paleolithic era. The area was especially rich in set

tlements during the Roman Iron Age. In the fifth century A.D. there seem

to have been a certain lacuna in the settlement sequence. However, alread

by the end of the sixth century the Kiev plateau was resettled. A number

stray finds are datable to this period (Karger 1959, pp. 92-97), and there

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

326 JOHAN CALLMER

are also settlement finds dating to t

pp. 104-105;Tolocko 1978, p. 85).

Detailed knowledge of the settlem

better understanding of the develop

nology of Slavic settlement in the e

worked out as we would like. The p

Kiev is situated in a border area bet

In the western part of the Ukraine

pottery. Later development include

stages (Rusanova 1976). The latter

ninth centuries. Korcak-type pot

Starokyjivs'ka Hill (Karger 1959,

from the Obolon' district close t

Luka-Rajkovec'ka pottery has also

(Kilijevyc 1976, p. 187) and on th

In the wooded steppe zone there w

changing definitions called the

Pryxodnjuk 1980; Sedov 1982, pp.

were some types of handmade p

wheel-turned ware. The latter type

nomad culture; strong interconnec

patterns involving, the nomad po

steppe can be noted. The majority

have disappeared as early as the sev

On the east bank of the Dnieper, n

settlements, one meets another cul

early eighth century, settlements o

1975). Like the Pen'kivka complex,

Middle Dnieper area north of Kiev,

the last fifteen years Kolocyn sites

(Kravcenko et al. 1975, pp. 95-96

the settlements on the Desna and t

developed into the Volyncevo type

turies is not altogether clear. For ou

Kiev, it is enough to say that in the

ments of the Volyncevo type wer

upper Sula and Psel Rivers (Gorj

important to note that the Volync

distinct sites of this type have bee

Xodosivka on the Dnieper (Suxobo

River, a small tributary of the

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 327

Kravcenko 1978). Both localities are sit

the center of Kiev.

The date of the Volyncevo settlements

This is mainly due to the very few finds f

well dated in other complexes. The Xodo

ably more precise dating through finds

found in the early catacomb graves of th

mainly dated from the end of the eight

1982). Already in the first half of the ni

distinctive wheel-thrown Volyncevo w

called Romny-Borsevo cultural complex

In the ninth century Kiev was situated a

Luka-Rajkovec'ka area. Pottery of the pe

main pattern, for example, through the

impressions on the shoulders of vessels.

with the Romny-Borsevo complex furth

earliest urban phase in Kiev, which prob

some Eastern elements. In some cases

Borsevo pottery (Tolocko 1981 A, p. 72).

Cultural development in the Kiev regio

first millennium brought considerable

versus Western cultural traditions. Sometimes the Western elements were

stronger and sometimes the Eastern ones predominated.

Ninth-century settlement in the Kiev region consisted of a number of

small habitation sites (fig. 3), situated on easily fortified promontories.

Whether the sites were always fortified remains uncertain. Traces of ninth-

century settlement have been documented on the Starokyjivs'ka Hill. The

relatively small but mostly well-spaced areas that have been available for

excavation have not allowed a detailed evaluation of the size of the settle-

ment (cf. Kilijevyc 1982, fig. 94). It is reasonable to suppose that it

comprised an area of no more than one hectare. In fact, there are only two

or three sunken-featured buildings there that can be dated to the ninth cen-

tury; indeed, it is doubtful whether one of them actually predates the early

urban phase or whether it is contemporary with its onset. The pottery

shows clear Romny-Borsevo elements (ibid., p. 28). One house sits on a

ledge a little below the plateau on the hill's northwestern slope. About

100m further to the east, also close to the slope, another, probably contem-

porary, house has been excavated (ibid., p. 141). Of the two early sunken-

featured buildings in the southwestern part of the Starokyjivs'ka, one

undoubtedly belongs to a period much earlier than the ninth century and the

other might as well.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

328 JOHAN CALLMER

Among the constructions connec

settlement on the Starokyjivs'ka, t

found by Xvojka in 1908 and reex

more important role. The existe

place has been a chief argument fo

tlement in Kiev as a great center.

time of the first excavation had th

gray sandstone slabs of differen

were set on clay and formed an e

In each direction there was a recta

dation parts of a clay floor were

was also a "pillar" of considerab

superimposed on each other in ma

bones were found nearby (Xvojka

tion" Xvojka believed was a paga

dated it quite early, to the eight

Tolocko 1970, pp. 48-49; Kilijev

ever, some problems with both the

date. First of all, Karger showed in

stone construction that Xvojka' s

the published drawing of the kap

oval and the offshoots are also ve

rectangular than oval, and in tw

Karger, however, does not doubt t

sacrificial place (1959, pp. 1 10- 1

as curious as the foundation. It must have been a construction similar to an

ashpit excavated at 3 Volodymyrs'ka Street in 1975 by the Kiev Archaeo-

logical Expedition (Tolocko and Borovs'kyj 1979). In that case, the ashpit

was probably connected with a pagan place of worship. The ashpit "pil-

lar" in Xvojka's trench is not clearly connected with the "foundation."

The top level of the pillar, for example, is considerably above the level of

the stone construction. Recent work on the earliest tenth-century stone

architecture has brought to light some sections of a building or buildings

that are conspicuously similar to the "foundation" of Xvojka (Xarlamov

1985, p. 110). This similarity has been rightly stressed by the excavator,

who has carefully suggested a close connection between the building and

the "foundation." The same type of handmade pottery, it should be noted,

was found in a layer beneath both. It should also be remembered that

Xvojka observed a floor of white clay in the vicinity of the foundation

(Xvojka 1913, p. 66). Clay floors were more likely inside buildings than

outside them. It must be concluded that the interpretation of the

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 329

"foundation" remains uncertain, althoug

nected with the pagan cult. The date of

certainly much later than the usual datin

probably the early urban phase in Kiev.

In addition to the small number of sun

sacrificial spot, the moat cutting off

Starokyjivs'ka Hill is usually mentioned a

(Kilijevyc 1982, pp. 27-28). The occurrenc

the fill of the moat has been taken a

fortifications. As has already been point

observations have little relevance to the qu

the rampart. In some sections of the moat

(Tolocko and Hupalo 1975, p. 7). Since t

the tenth century and since the fill is p

rampart which, in turn, is the material th

the moat, a late date for the moat could

cal attitude toward the early dating seems

When we consider the extant evidence o

tlement (except the last two decades), the

ously existing fortified settlement with

Starokyjivs'ka. From excavations in both

know how densely built with sunken-fea

fortified and unfortified, often wer

Novotrojic'ke (Kuxarenko 1957; Ljapusk

on the Starokyjivs'ka Hill is consider

important. Material from the Volyncevo

there are no imports from the Saltiv-Maj

ical of settlements dating to the late eigh

as yet, no early Abbãsid dirhams from ei

of dirhams and metal artifacts of the Sal

tic of major settlements of the period

Opisnja (Ljapuskin 1947, 1958).

Castle Hill, or the Kyselivka, is a ra

70 -80m above the surrounding terrain

was easily fortified. The only serious dr

of the hills to the south in relation to

these hills could severely menace defend

there are cultural layers dating to the eigh

erable parts of the hill. Pottery here is lik

featured building excavated by Karge

1939 - mostly of the distinct Luka-Ra

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

330 JOHANCALLMER

1959, 1963). Unfortunately, no h

is partly due to subsequent intens

tion with burials in the cemetery

some indications of sixth-century

that on the Starokyjivs'ka already

The long but narrow promontory

Dytynka (Sovkopljas 1958, p. 14

tery with Luka-Rajkovec'ka chara

ever, and no details about the cha

Early handmade pottery has a

(Tolocko 1982, p. 24).

Some finds of handmade potte

stray finds and excavation finds,

(Tolocko 1965; Hupalo 1976). Bu

earlier than the last two decades o

are no houses from the period in

tery in this part of Kiev have eit

downhill from the Kyselivka (H

very earliest settlements in the Po

handmade pottery was in use in t

(Suxobokov 1977, p. 75ff.).

As has already been noted, settle

and seventh centuries) has been e

in the Obolon' district, north of the Podil. The Obolon' is situated at a

higher level above the river than the Podil and was accessible to settlers

before the ninth century.

Evidence of eighth- and ninth-century settlement in other parts of central

Kiev is lacking. This does not mean that there were no other settlements

there, for unfortunately, excavations in Kiev have been done largely in just

some central areas. If such settlements did exist, they were most probably

of the same type - small and basically rural in character.

Consequently, no early center is discernible in the Kiev region. There

was no definite princely site with administrative and economic functions

extending beyond the vicinity of Kiev. There is no evidence of long-

distance trade connections in the period. The numismatic evidence, which

is completely non-existent, seems in this case to be decisive. It is uncertain

whether there were any eighth- and ninth-century Arabic dirhams at all in

the Kiev region in the ninth century (cf. Callmer 1981, p. 46). A find of

four ninth-century dirhams "from Kiev" must be considered suspect (Fas-

mer 1931, p. 15). Imports from the Saltiv-Majaky culture are known from

at least one settlement in the vicinity of Kiev belonging to the Volyncevo

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 33 1

settlement type, but they are unknown fo

for a very small number of sherds (Tolock

Kiev was certainly not a likely tribal cen

logical material of the eighth and early nin

the idea of Kiev as the center of a hom

analysis of material culture remnants in

indicates a rather extreme border zone character of settlement. In some

parts of the Right Bank, as in Kiev itself, the Luka-Rajkovec'ka settlements

centered in southern Polissja, Volhynia, and Podolia reached the Dnieper;

elsewhere, the Volyncevo-type settlements centered in Severia reached the

Left Bank. This borderland character goes back even further: in the

sixth- seventh centuries the parallel occurrence of Kolocyn-type sites and

Korcak-type settlements in the Kiev region can be noted.

IV. KIEV IN THE LAST DECADES OF THE NINTH CENTURY

AND THE FIRST HALF OF THE TENTH CENTURY

Given the commonplace character of settlement and the modest size of it

early settlements, the subsequent development of Kiev was clearly co

nected with a rapid and tremendous change in economic, social, and cer-

tainly also in political conditions over a period of only one to two genera

tions. A few decades into the tenth century, a completely new hum

society must have evolved.

Unfortunately, a detailed chronology allowing a close study of the

dynamics of development from the late ninth century to the late tenth an

early eleventh centuries has not been worked out. Pottery, the most impor

tant evidence for the dating of settlement, cannot as yet be dated closer tha

within two generations to a century. Hoards, single coins, and jewelry ca

give certain suggestions for a closer dating, but generally this is also vague

Architecture, especially stone architecture, can be used for certain chrono-

logical grouping. But dating the dynamic development of Kiev by observa

tions of these categories of material is still unsatisfactory. Only in the Pod

can dendrochronological samples from wooden architecture furnish us with

more precise information about the development of settlement. Here we

follow that development from the late ninth century to the beginning of th

eleventh century in two stages. The mid- tenth century is the divide betwe

the two stages. For most materials it is possible to separate early from la

material within the period from the late ninth century to the early elevent

century (e.g., Tolocko 1981B, pp. 298-301).

Settlement in the Kiev region from the end of the ninth century onward

is known from a number of different localities (fig. 5). The main settleme

areas were located along the hills and in the Podil. The northernmos

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

332 JOHAN CALLMER

settlement area was probably on th

can be dated to the late ninth and e

and consists mostly of stray finds.

Jurkovycja Hill, above the Iordaniv

to tenth-century fortified settleme

tor suggest that the fortified settle

bynci culture of the Pre-Roman Iro

Ages. The idea of a fortified, late ni

part of Kiev should not be dismisse

vations in the vicinity suggest t

gravesites. The settlement may hav

erosion and clay digging along the

type sword found near the Iord

which probably belongs to the late

also graves on the heights, of which

of these graves were excavated by X

(Xvojka 1913, p. 57). His scanty exc

these graves were tenth-century c

and in some cases displaying the lo

of cremation remains (Sedov 1982,

burials in pits, which were characte

Romny graves (ibid., p. 138). Nume

in barrows were also excavated. Oth

Scandinavian-type artifacts (Karg

about graves in this area, gather

cemetery II, strongly suggests th

perhaps already at the end of the n

with varying mortuary rites. The

centrated in the region close to wh

be built. It is, as already stressed

existed because of considerable sett

a tenth-century, sunken-feature

obtained, and in this connection co

(Tolocko 1970, p. 68; Maksymov

antiquarians also describe the rem

immediate vicinity of the Iordan

exact date of the building's construc

Considering the total archaeologica

this area, settlement and populatio

extensive. It is not likely that the

Podil. If the populace dug their gra

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 333

more likely location, as were the hills

implications must be given their due we

this part of Kiev derives mostly from ou

of the excavation in 1965 already mentio

has been carried out in the area. Yet this

role in the earliest stage of the center's

reasons for this interpretation. First, the

from others further south was consider

plexity of the archaeological material

developed settlement with its own popula

tlement, which may or may not have been

tress Iccfißaxac mentioned by Constantin

speculative (cf. Bulkin et al. 1978, p. 14).

a number of prominent households, pe

prince's residence. The population was ob

ous local and exogenous elements includ

dence about habitation and graves indicate

restricted mainly to the tenth century.

As in the eighth century and probably

tury, settlement on the Kyselivka Hi

material about the settlement, although

from the Jurkovycja area. On the north

three sunken-featured buildings have be

kopy 1947; Bohusevyc 1952). Also found

brick building, probably rudera of a secul

or eleventh-century date. The tenth-centu

Petrov (1987 p. 260) and is uncertain. T

Bohusevyc actually found brick fragmen

p. 68). Although major parts of the plate

the layers have been severely damaged, it

of the hill was settled in the course of th

tained that there were never any graves

65). In view of the state of preservation

hill, this is a questionable position. Due to

that during more intensive settlement o

established away from the hill. Arch

Kyselivka indicates a large settlement a

this case, too, the full dynamics of develo

be gathered from the the archaeological

ever, that the structure of the settlement o

neighboring settlement to the north just de

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

334 JOHAN CALLMER

Archaeological material from t

nous and differentiated, due to m

better preservation. The Staroky

steep slopes to the southwest, t

towards the southeast are there

about 20m higher than the Kyseliv

(ca. 150m wide) ravine (cf. Karger

For the Starokyjivs'ka, there are

material from the late ninth and t

there are very few indications of

the rampart and the moat on the

fortifications, set off in an area of

hill. In many respects the topogra

plateau both inside and outside th

all remnants of postbuilt, sunken-

Although for Kiev a considerable

of the area inside the rampart - v

been found there. Nine houses have been documented in the northwestern

and northeastern parts, all close to the steep slope. The central part of the

hill was obviously not built in usual rural architecture, namely, postbuilt

sunken-featured buildings. The lack of such evidence is telling, since no

fewer than twenty sunken-featured buildings dating to the eleventh and

twelfth centuries have been excavated in Kiev by Xvojka and others (Kili-

jevyc 1982, p. 161ff.). Other types of houses with horizontal timberwork

built on the surface might well have existed, however. This type of build-

ing is typical of Slavic and perhaps also of Baltic and Finnish building tradi-

tions in the forest zone; it is alien to the loess area in which Kiev is situated.

In fact, there is one documented case of this type of construction on the hill.

Partly cut short by the Tithes Church, a quadrangular timber construction of

exactly this type was excavated by Mileev (Karger 1959, pp. 172-73); it is

probably of mid-tenth century date. Sunken-featured buildings constructed

by this technique were excavated by Bohusevyc on the Kyselivka

(Bohusevyc 1952). It is possible that some large timber buildings were

constructed in the earliest phase, in the late ninth and early tenth century, as

well. It is most probable that there were wooden precursors to the later,

tenth-century representative stone architecture. We know nothing at all

about the construction of these dwellings from the archaeological sources.

Were they large halls of the North European type, were they wooden imita-

tions of Byzantine palace buildings, or were they something else?

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 335

Some time in the middle of the tenth ce

its first appearance on the hill. This is und

sive cultural and other contacts with the Greeks in Crimea and in the central

parts of the empire. Byzantine court life and the way of life of its elite had

become a mental template in Kiev for some time, but it was only now that it

influenced building construction. Two buildings probably belong to this

earliest phase of stone architecture on the hill. They may date to the middle

of the tenth century or even a little earlier. A little to the south of the

center, inside the rampart and the moat, remains of an early stone construc-

tion have been found (Borovs'kyj 1981, pp. 175-181; Xarlamov 1985, pp.

106- 1 10) (fig. 6). Their fragmentary character makes complete reconstruc-

tion infeasible, but some general features can be noted. The building was

constructed from materials transported a considerable distance, including

heavy granite stones, sandstone, and rosy slate from the Ovruc quarries.

Brick fragments further confirm the high standard of the building tech-

niques. The building was richly embellished with frescoes and decorations

of marble from Prokonnesos. The floor was covered with polychrome tiles.

The excavators probably rightly interpreted the amounts of charcoal from

large timber in the upper debris layer as evidence of a collapsed wooden

upper floor.

The shape of the building is indicated only by a slightly curved, short

segment of the wall. This could suggest a circular layout (Xarlamov 1985,

pp. 106- 107). The outer diameter of the building was probably about 17m.

Yet other reconstructions are possible: what was found may be a curved

section of a more complicated building. There are foundations of large but-

tresses which might have been in harmony with a circular construction.

Several are very similar to the sacrificial place found nearby, discussed

above. Could the findings at that site actually be architectural fragments?

The other palace building was situated about 13m north of the northern

corner of the Tithes Church. It stood only a few meters outside the moat of

the late ninth- and tenth-century fortifications and originally just above the

steep slope. This building had a distinctly rectangular shape: it was 21m in

length and about 10m in width (Xvojka 1913, pp. 66-69; Karger 1961, p.

67; Tolocko 1970, pp. 56-57). The structure was divided into one large

and two smaller rooms. The building material was stone and brick, with

decorations of marble and slate. Frescoes ornamented the walls, and there

is evidence of mosaics. In this case, too, there was probably a wooden

upper floor.

These two stone buildings are probably among the earliest in Kiev.

However, Xvojka has found seven instances of early stone architecture at

various sites on the central part of the hill (Xvojka 1913, pp. 63-74). New

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

336 JOHANCALLMER

excavations are needed to determi

the earliest phase of stone archite

with the late tenth-century buildi

constructed in Byzantine style alr

tury. Inside the fortification the

probably with idols and sacrificial

Outside the fortifications exte

1959, p. 138ff.; Kilijevyc 1982,

century it probably contained ma

in coffins and chambers and crem

tinct Scandinavian features. On

Karger 1959) in every detail re

chamber graves (fig. 7). There

graves. Two finds of Scandinav

(Karger 1959, p. 218). It should al

living outside the rampart in area

It is now possible to visualize w

the middle of the tenth century

1959, p. 99) and the earthen ramp

high and which may have been

fortifications, stood a complex of

with wooden second floors. In ad

buildings and small timbered, q

also some remains of a complex of

antedated the stone buildings. The

of the fortified area and the sma

phery, especially towards the slo

side the fortifications, wide ex

were, however, also plots with sm

on the edge of the slope close to t

surrounded by minor wooden b

own).

Let us now look at the other parts of Kiev at that time. During the ninth

and especially the tenth century, the riverbank, which had always been of

moderate breadth and very wet, was rapidly rising and becoming more and

more suitable for settlement. The formation of the territory of the low river

bank, the Podil, was the result of a number of deluvial and alluvial

processes. The sedimentation of enormous quantities of sand by the

Dnieper was the most important factor, but erosion from the hills also

played a role. The latter process was rapidly becoming more and more not-

able in the destruction of the natural vegetation cover on the hills and

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 337

slopes. The gradually rising riverbank was

ing from the ravines, the northern one b

ern, the Hlybocycja.

Excavations begun in the early 1970s cl

settlement in the Podil until the late nin

38-39; Hupalo 1982, pp. 18-33; Mezents

able for settlement earlier, and even the

for a long time, at least through the tenth

early settlement in other parts of Kiev, t

dated quite accurately, thanks to a detaile

dence for dendrochronology, numism

design (Sahajdak 1981, 1982A, 1982B). T

are dated to A.D. 887 (Hupalo 1982, p. 15)

certain extent a calculation of statistical

not be considered absolute, although resu

ments of more than a decade are unlikely.

Already from the early tenth century

suitable for settlement were divided into

two sizes: the smaller ca. 300 square mete

800 square meters (Tolocko 198 ID, pp

with generally larger plots, also existed in

Novgorod. Each plot was claimed for g

proved very conservative and stable. The

from the outset of settlement, may indi

lowers and retainers of land previous

probably - originally claimed by the elite

Constructed on the plots were timberh

work, in some cases of the regular pjaty

otherwise known only further north, in

house stood back from the street, with a

street. Due to the very wet conditions, h

foundations. During the tenth century

times by new sediment layers. Reconstru

the earlier pattern.

There is little variation in the architectu

and the high water table made it ver

buildings - in fact, no early ones are kno

second terrace) at the foot of the hills m

buildings in the course of the tenth centu

erected there. Until recently, graves fro

the river bank area. Now excavations h

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

338 JOHAN CALLMER

eleventh and twelfth centuries at

and Stepanenko 1985, pp. 83-85).

(Hupalo and Tolocko 1975, p. 46).

The economic specialization of the

centuries was trade and crafts, and i

very beginnings of settlement. On

plosca in 1972 was probably a merc

coin, a weight, and some other item

and Tolocko 1975, pp. 41-61), alth

cialization from the earliest period i

The Podil of the late ninth and fi

extensive area with rather dense set

of two riverbank terraces. Here an

higher, there was also settled land s

grew constantly. Streets and alleys

were fenced. The timber buildings

frequently had a second floor. It is

the banks of the Pocajna.

Traces of settlement, albeit vague

localities in central Kiev. Cultural l

both the Scekavycja and the Kudrja

well as on the Dytynka (Tolocko 19

If we review the entire settlement

early tenth century, we now have

rapid development. From a populat

sons before the late ninth century

hills large areas were rapidly cleare

ings or set aside as cemeteries. T

parts, possibly due in part to topog

of early Kiev. In this early phase,

tinct area of the hills with their r

area had buildings and adjoining plot

guard, etc. The preeminant part of

early tenth century or even earlier

the seat of the leading elite family.

slightly different character, that is

that on the hills and only partly in

tem.

By the early tenth century, the population must have grown into the

thousands. Even if the rich loess on the hills was ploughed and cattle,

sheep, and horses grazed on meadows in the valleys of the Dnieper and the

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 339

Pocajna, it is most unlikely that the subs

based on the production of food and comm

The population of proto-urban Kiev was

influx of products from tributary tribes an

It is very likely that craft production de

elite and among the population of the Po

early phase is the rapid development of

potters' craft. It was not centralized (Tol

Elements of the population were cert

trade already at the beginning of the ten

Samãnid dirhams indicate that part of th

Muslim East (Tolocko 1976, pp. 3-6; C

evidently also conducted with the Byza

(Tolocko 1976, pp. 6-10; Callmer 1981

hams belong mainly to the first half of t

must have been channeled along the m

started in Central Europe, passed throug

Khazar center on the lower Volga (Jacob

the Bulgar state at the bend of the Volg

the archaeological material, which, amo

Ugric artifacts (Karger 1959, pp. 216-1

Rybakov 1969, pp. 194-95, and Kropotkin

If one judges by the coin finds, the vol

Byzantium was less voluminous. This imp

ever, because the lack of coins could be du

tines to export their currency. By contra

minted for export (cf. Noonan 1988). P

with the Byzantines are amfora finds. T

century, suggesting that trade with Byza

The social structure of Kiev in the early

tioned in connection with architecture

society was highly complex, including pri

and retainers with families. These househ

of food and ordinary commodities for da

ing jewelry, weapons (perhaps armou

aggregates probably did not include the

eral population there were also a number

nected with them, and there may also ha

men.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

340 JOHAN CALLMER

Some idea of the social divisions i

tinct group of high-rank burials, o

1959, graves 103ff.). Then there is

conspicuous graves (e.g., Karger 19

86). Very simple graves with few

Karger 1959, graves 1-7, 9-13). C

graves, since cremation graves, few

documented.

The variation in building techniques and grave rites strongly indicates a

very complex cultural milieu and a polyethnic society (Mocja 1979). Local

East Slavs certainly made up a considerable proportion of the inhabitants.

Architecture and some grave rites suggest the presence of a large group of

people from the forest zone north of Kiev who were familiar with horizon-

tal timber construction and cremation burials. There were also high-ranking

Scandinavians among the population (Callmer 1981, p. 47). The archaeo-

logical data does not prove that there were Oriental merchants and artisans

in Kiev at this time, but the obvious importance of long-distance trade and

later evidence of such craftsmen's visits or permanent residence in Kiev

would indicate that they were present already in the early phase. Greek

architects, builders, and craftsmen certainly lived in Kiev for some time.

Also, Byzantine clergymen and their servants were probably present.

The large Kiev settlement was not an isolated community in the Dnieper

valley. There were certainly hamlets and possibly also manors in the sur-

rounding countryside. It is curious that evidence of settlement in nearby

territory seems to date mainly from a somewhat later period than the late

ninth and early tenth centuries (cf. Movcan 1985). It is uncertain whether

these neighboring settlements resulted from the establishment of Kiev or if

they were part of an old system of agrarian settlements in the region. Prob-

ably both factors were at play.

V. KIEV AT THE SECOND HALF OF THE TENTH CENTURY

AND THE BEGINNING OF THE ELEVENTH CENTURY

The ongoing development that occurred in the second half of the tenth cen-

tury established the early medieval center of Kiev as it would exist up to the

sack of the capital of Rus' by the Mongols in 1240. It was a period of very

rapid expansion. Several aspects of the economic and social structure

which earlier could only just be perceived now became distinct. Again we

proceed with a survey of the various parts of Kiev (fig. 8).

In the northern part of Lysa Hill, settlement continued in the second half

of the tenth century. Graves and other indicators of settlement can be dated

to this period (Tolocko 1970, p. 147; Maksymov and Orlov 1982). It

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 34 1

seems, however, that in the eleventh centu

the same scale as before; in fact, to some

the end of the tenth century (Tolocko

yet, we do not know if this was a gradual

either case, the entire character of an earl

of distinct and equal centers is lost. To jud

the population of this part of Kiev had bee

northern part of the Kiev Hills did continu

seems to have been only farms and suburba

part of the urban complex. By the end of t

definitely become secondary to the admin

the Starokyjivs'ka Hill.

Settlement on the Kyselivka continued t

indications of craft production on the hil

eleventh century. Two major collections o

their waste products were found in excav

(Karger 1959, p. 47); subsequent excavat

(Sovkopljas 1954). Among the items found

features (ibid., plate 11:10, 12). Some of th

eleventh century, as already pointed out,

continuity in production. In the northwest

the 1930s uncovered traces of bronze ca

workshop, which can also be dated to the

(Kilijevyc and Orlov 1985). Various mold

the production of buttons, have been f

1970, p. 145; Kilijevyc and Orlov 1985, p. 6

evidence of craft production indicates the

producing district, or whether the product

princely residence or a prominent fam

development of the princely center on th

tenth and eleventh century, and the lack o

ment on the Kyselivka, indicates that the l

tance.

In the late tenth and early eleventh centuries the settlement on the

Starokyjivs'ka clearly emerged as the political center of Kiev. Monumental

stone architecture became more impressive, and the number of buildings

increased markedly. During the last decades of paganism, a new or addi-

tional pagan shrine was constructed outside the old fortifications. This

place of worship was situated in a free zone between the barrow cemeteries.

Archaeological excavations have uncovered the foundations of this shrine

and of an ashpit similar to the one near the kapysce (cf. above, Tolocko and

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

342 JOHAN CALLMER

Borovs'kyj 1979). The most import

tlement outside the primary fortifi

these defenses and the tumulus gr

ones, now encircling an area of ca.

In the previous phase, the centr

defenses, was already dotted with

second half of the tenth century, m

become a more dominant element,

larger. With the beginning of work

(cf. Komec 1987, p. 168), Christia

became a notable feature on the

churches stood in Kiev is most uncertain. Historical sources indicate the

prior existence of at least one or two churches, but they have not been

located archaeologically (Tolocko 1970, p. 133). It is most unlikely that

they were in any sense prominent. The Tithes Church was built in a tradi-

tion which clearly indicates that the masters in charge of construction were

Greeks (Karger 1961, p. 10). This large structure (ca. 43 x 35m) was

erected only 4.5m beyond the old fortifications of a pagan tumulus

cemetery. The whole area was carefully leveled, and numerous kilns,

ovens, and stone masonries operated near the church site for about a decade

(Kilijevyc 1982, pp. 70-77). The church was first consecrated in 996. The

interior was richly decorated with floors of tile and mosaics and with details

of slate and marble (Karger 1961, pp. 56-59).

Only about 17m to the southeast of the Tithes Church, the foundations of

a large, secular stone building were excavated by Mileev and Vel'min in

1911-1914 (Karger 1961, pp. 67-72). The structure measured more than

30m in length and was about 8m wide. The foundation was built in a tech-

nique corresponding closely to that used for the Tithes Church (ibid., p. 71).

The building must have been a large palace constructed at about the same

time as the church. It was obviously one of the major structures in the new

princely compound outside the old fortifications. Another large rectangular

building measuring more than 35m in length and ca. 8.75m in width stood

about 60m southwest of the church (ibid., pp. 73-76; Xarlamov 1985, pp.

1 10-12). There the interior was obviously divided into a number of rooms.

Also, this building was erected on a substructure of concrete, on a wooden

carcass. Traces of its stone foundations and brick walls are almost totally

absent. Evidently this was another large secular building erected in the late

tenth century in connection with the replanning of the central area on the

Starokyjivs'ka, probably in connection with the building of the Tithes

Church. This second building was orientated almost exactly as was the

church, a feature shared with no other known building on the hill. Both the

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 343

palace buildings probably had second floo

Let us visualize, then, what the central

like in the late tenth century. There was

Church in the center and two large palat

tance to the southeast and the southwest

on the edge of the hill, there still stood a

stone and brick palace. It is unclear wheth

there was another palace building or whe

been destroyed. The whole central ar

assembly of monumental architecture, a

Eastern Europe north of Xersones (Jakob

must have witnessed the most important

society, there were less conspicuous b

made of timber. As we know from Novg

tures could have had several stories. Of t

ture there is archaeological evidence. The

buildings along the periphery around t

1982, fig. 94). In several cases we have ev

craft production. Recent excavations in th

prove the existence of bronze casting, inc

cial sort of earring, finger-rings, and bu

61ff.). The excavation trench is situated

about 22m to the southwest of the early,

is also evidence of artifacts of antler and

crafts may have been closely connected w

items as jewelry, toilet accessories, cloth

played an important role in the economy

between the elite and their entourage. Co

was an obvious goal for any prince seekin

We know that settlements on the Starokyjivs'ka became more

widespread, but we are uncertain about their plot system and the economic

and social character. Sunken-featured buildings of rather indistinct charac-

ter were the primary indicators of settlement. It has been argued that the

discovered building fragments are actually parts of much larger buildings

(Tolocko 198 ID, pp. 46-48), but there is little concrete evidence for such

speculation. Many of the sunken-featured buildings (with ovens) were

small dwellings in the local tradition of the forest-steppe zone.

The center on the Starokyjivs'ka Hill may have been surrounded by

compounds of the prince's followers. The archaeological data are, how-

ever, too meager to shed light on this possibility.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

344 JOHAN CALLMER

The new fortifications on the Sta

part may have stood more than 6m

deep, especially since it partially f

pp. 51-57). There was at least on

ably crowned by a low tower (Sam

As we know, a distinct feature of

its rapid development in the south

was the development of settlemen

pp. 24-26) and in areas between t

(Borovs'kyj and Sahajdak 1985). S

already in the late tenth century,

grave found at the intersection of

1959, pp. 169-72) may indicate ev

hood (early tenth and mid-tenth c

the Kopyriv Kinec' and adjoining a

buildings or square, timbered hous

a rampart and a dry moat (Tolocko

Already in the early tenth centur

considerably. In the second half of

to grow up the riverbank, followi

its. In fact, the settled area of the

tury. Only during the eleventh

become secure from recurrent inu

know, plot boundaries remained u

The economic and social character of the settlement in the Podil became

more distinct. Also, there is now unambiguous evidence of craft produc-

tion. An important find was that of four slate molds for belt mounts along

the Podil's northern periphery (Hupalo and Ivakin 1977). The molds,

recovered inside the remains of a burnt-down dwelling, are made of Ovruc

slate, which must have been transported to Kiev over land or more probably

by boat via the Horyn', Pryp"jat', and Dnieper Rivers. An Arabic inscrip-

tion on one of the molds is evidence that the owner or the artisan who made

the mold came from the East. This was the time when Khazar towns were

in rapid decline. The concurrent rise of political and economic life in Kiev

suggests that merchant and artisan emigrants from Khazar towns may have

moved to the flourishing new center.

Iron production and perhaps especially iron working were of importance

in the Podil. Excavations by Bohusevyc in 1950 of cultural layers going

back to the eleventh or perhaps even the late tenth century gave much evi-

dence of iron working (Bohusevyc 1954). Considering the topography, it is

likely that iron working was also located along the peripheries of the Kiev

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 345

settlement. The identification of a s

Starokyjivs'ka (Kilijevyc 1982, p. 160)

were actually along each distinct distr

played various roles in different district

hold smithying and specialized smithying

In the second half of the tenth century

there probably existed a number of settle

of Kiev along the heights above the D

tecja) and Uhors'ke (Askol 'dova mohy

already during the tenth century (Toloc

Kiev, a number of settlements also ex

Rivers, the natural boundaries of the Ki

right bank of the Lybid' traces of settle

eleventh century have been excavated op

station (Movcan 1985, pp. 121-22). The

lier settlement nearby, connected in

Batyjeva Hill (Golubeva 1949, p. 106).

At the western end of Luk"janivs'ka

small promontory overlooking the Syre

(Movcan 1985, pp. 122-24). Findings indi

the tenth century. Settlements probably

Dnieper, for instance, at Darnycja (Callm

Kiev in the second half of the tenth cen

growth. In the last decades of the tenth

gious center on the Starokyjivs'ka Hill b

Kiev, with an appearance resembling t

cities with a long urban tradition. Altho

would have taken on such a character ev

introduction of Christianity in A.D. 9

transformation in the development of K

With the beginning of the construction o

tral Kiev gained the character of a Euro

still a barbarian one.

The second half of the tenth century is also the period when Kiev

definitely loses its polycentric character. Gone is the structure of the early

stage, when a number of distinct areas of settlement were strung along the

Kiev Hills for some four kilometers. This does not mean that some districts

were abandoned altogether, but the center of gravity did move south. Both

demographically and functionally, the center of Kiev becomes the

Starokyjivs'ka Hill and the Podil below. Settlement now developed most

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

346 JOHAN CALLMER

vigorously in the Podil and to

Starokyjivs'ka.

As already noted, there is an

findings for study of the Podil.

settlement there is probably also c

less well-preserved remains. The

the buildings strongly indicates

or two families.

The social and ethnic structure of Kiev's population becomes less dis-

tinct during this period. This may be due partly to a process of strong and

continuous cultural integration. After all, by now some of the population

had lived in Kiev for two generations or more. The rapidly diminishing

number of pagan graves makes it difficult to trace different ethnic groups.

The social structure is now best studied through architecture and the layout

of buildings and plots.

VI. THE DEVELOPMENT OF EARLY KIEV

The rapid growth of Kiev from the late ninth century to the early elev

century occurred not only in size, but also in social, economic, and poli

life. From a couple of small agrarian settlements in the ninth century,

grew into an extensive settlement already in the first half of the tenth

tury. Probably the growth in settled territory during this period was f

ca. 2-3 hectares to more than thirty hectares, that is, by a factor of

than ten. Growth continued to be strong to the end of the eleventh cen

From the middle to the end of the tenth century or the beginning of

eleventh century, Kiev's settled territory expanded to ca. 48-50 hectare

The structure of the early center of Kiev also changed considerably. T

agrarian settlements that existed in the Kiev area before the late ninth

tury probably did not differ from other rural settlements in the region

uncertain whether these settlements were fortified or not.

From the late ninth century a complex social structure came into being,

producing a social stratification notable both in graves and in the architec-

ture and layout of the town. The archaeological evidence seems to suggest

the existence of at least five social groups. Of course, princes together with

their families were the ruling group. In the early phase, more than one

princely residence seems to have stood in the topographically distinct parts

of the settlement. A second stratum of the princes' high-ranking followers,

retainers, and mercenaries is discernible in the grave material. Merchants

and artisans formed foreign colonies, but some were part of the princely

households. A stratum of low-ranking followers and household people

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 347

formed a large part of the population. La

slaves in considerable numbers.

This social stratification was made more complex by the highly varied

ethnic and cultural composition of the population (Mocja 1979). A majority

of residents were undoubtedly people of the local Slavic forest and forest-

steppe. Easterners, that is, people from the Khazar towns and those

involved in the long-distance trade that went through Kiev, certainly formed

another distinct cultural group, probably one ethnically and confessionally

diverse. At times and also in some numbers, especially towards the end of

our period, Greeks were permanent residents of Kiev. Scandinavians were

another ethnic group belonging in part to a higher social stratum.

With the formation of Kiev in the late ninth and tenth centuries, there

began a process of cultural integration which may have had an impact on

the ethnic character of some groups of the population. Certain ethnically

associated habits, like details of dress (ornaments), became less and less

prominent.

The formation of Kiev was also an important economic event marking

the emergence of a new economic system in the Middle Dnieper region.

From the outset Kiev depended to some extent on tribute from surrounding

areas as well as more distant lands. Goods collected and brought to Kiev

not only contributed to the well-being of the population, but also attracted

the attention of traders. The concentration of people and the importance of

gift-giving and rewards also contributed to the appearance of producers-

artisans.

There are no close parallels to Kiev in construction and layout during the

earliest phase. There were, however, some complexes not very different

from early Kiev. A number of Khazar centers (in the political sense and not

to be confused with authentic Khazarian cities such as Itil and Sarkel) in the

Don-Donee' basin had similar characteristics. The center at Verxnij Saltiv

is one example (Berezovec' 1962). In addition to a fortified nucleus of ca.

3.75 hectares, there was an extensive settlement inside a second, earthen

rampart on the high, west bank above the Donee' River. The valley floor

was too wet to allow settlement there, but an extensive open settlement

stood on the east bank. The total extent of the settlement has been

estimated at ca. 120 hectares. Although there are some problems with chro-

nology (cf. Icenskaja 1982), it may well be that the settlement at Verxnij

Saltiv grew very rapidly to its maximum size in no more than one or two

generations. There were no precursors to that settlement. Another very

large settlement complex existed concurrently at Vovcans'k (Pletneva

1967, pp. 34-35). There, it has been suggested, the central fortificatio

was the site of cult worship. Smaller, but similar to the Verxnij Saltiv

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

348 JOHAN CALLMER

settlement, was the site of Majak

and the Don (Pletneva 1984). It h

rounding open settlement ca. 20

of these settlements and their d

both as food for the population a

mon with Kiev. Part of the po

lived a semi-nomadic life, but th

their general character. They p

whereas, as we have seen, Kiev fr

A few West Slavic settlements

and Prague. Both towns had at

large settlements. These centers

the tenth century. Prague, in pa

Kiev settlement (Borkovs'kyj 1

fortified places connected by un

the open settlements in Prague is

picture of the growth of these d

however, that an open, commerci

the tenth century. In Cracow co

one fortified settlement, Wawel

there was an extensive area of op

the OkoL During the tenth centu

of ca. 14-15 hectares. Although

very strong and rapid, the impe

are indications that the general d

was more gradual.

Byzantine towns were certainly

in the latter part of the tenth ce

however, only a vague likeness b

Kirsten 1958). Any likeness to

was also only very general (Stanc

The development of Kiev was a

Eastern Europe, the first, tent

centers. The background to thi

economic factors, which made

foodstuffs and of goods in deman

when Kiev was connected with t

phate. Ideas about the administrat

goods from the subjugated ter

Europe. These preconditions mad

mentality, who perhaps scarcely

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 349

of the period but nonetheless accept

states and urban centers.

Kiev's growth was not merely as a conglomerate of villages. Urbaniza-

tion brought about a totally new situation. In research concerning the

development of early towns in Kievan Rus' two theoretical models have

been proposed. The first model can be called the Novgorod or koncy model

(Janin and Aleskovskij 1971; Kolcin and Janin 1982, pp. 104-114).

Advocates of this model maintain that the early centers of Kievan Rus'

developed as a result of a synoecism of a number of earlier settlements.

The second model is the bipartite one (Tolocko 1985, p. 5). Advocates of

this model maintain that the fortified center (dytynec' ) with an adjoining

open settlement (posad) is the original, basic structure of all urban centers

in Kievan Rus'.

It is difficult to maintain that the early northern towns of Rus' developed

as a result of a synoecism between a number of closely situated settlements.

As Tolocko has rightly put it, at that time in Eastern Europe the town was a

completely new social phenomenon (ibid., p. 12). In the case of Novgorod,

there is a growing amount of evidence of an earlier center at Gorodisce, to

the south of Novgorod (cf. Karger 1947, pp. 145-48; Nosov 1985, pp.

63-64), and there are as yet no indications of early settlements that could

later have formed Novgorod. The dichotomy proposed in the second model

is not applicable to the earliest proto-urban and urban centers of Northern

Rus', like Pskov, Ladoga, and Gorodisce (the precursor of Novgorod).

Also, the second model is hardly ideal for explaining the early development

of Kiev. The later phase, or what we tentatively date as the late tenth cen-

tury, certainly brought an urban structure to Kiev, which conforms to the

bipartite model. The earliest phase, however, does not fit the theory well.

Even if it is assumed that the urban topography was strongly influenced by

the landscape, there was a marked difference between the layout of settle-

ment in the early versus the late phase. Kiev in the late ninth and early

tenth century cannot be analyzed simply within the framework of the

dytynec1 -posad dichotomy. The earliest phase in Kiev was characterized

much more by a concentration of political power in groups of people than

by a single center. It then rapidly attracted economically specialized indivi-

duals.

The development of Kiev is the change from an originally complex and

fragmented settlement area to an enormous - for its time - urban center

with a clearly bipartite structure. Late tenth- and eleventh-century Kiev

strongly influenced the layout of many towns in Kievan Rus' that began to

develop in the eleventh and twelfth centuries. At that time it became the

model city for Kievan Rus' - it was in this sense that Kiev was the true

mother of the towns of Rus'.

Lund University

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

350 JOHAN CALLMER

LIST OF REFERENCES

Berezovec' (Berezovec), D. T. 1962. "Raskopki v Verxnem Saltove 1959-1960

gg.: Pecenezkoe vodoxranilisce." Kratkie soobscenija Instituía arxeologii A

USSR, no. 12. Kiev.

Bohusevyc, V. A. 1952A. "Rozkopy na hori Kyselivci." Arxeolohicni pam"jatk

URSR3. Kiev.

arxeolohicnymy danymy." Arxeolohija

Borisevic, G. V. 1982. "Xoromnoe zodcestvo N

nik: 50 let raskopok Novgoroda. Moscow.

Borkovs'kyj (Borkovsky), I. 1961. "Der altböhm

Praha." Historical. Prague.

Borovs'kyj, Ja. E. 1981. "Svetskie postrojki." N

verxnego Kieva v 1978-1982 gg." In Arxeolog

1978-1983 gg. Kiev.

Bulkin, V. A., Dubov, I. V., and Lebedev, G. S. 19

Drevnej Rusi IX- XI vekov. Leningrad.

Callmer, J. 1981. "The Archaeology of Kiev ca. A.D. 500-1000: A Survey."

Figura, n.s. 19. Uppsala.

Fasmer, R. R. 1931. "Zavalisinskij klad kuficeskix monet VIII-IX vv." Izvestija

Gosudarstvennoj akademii istorii material' noj kul'tury 7, no. 2. Moscow and

Leningrad.

Golubeva, L. A. 1949. "Kievskij nekropol'." Materialy i issledovanija po arxeo-

logii SSSR, no. 11. Moscow.

Gorjunov, E. A. 1975. "O pamjatnikax volyncevskogo tipa." Kratkie

soobscennija o dokladax i polevyx issledovanijax Instituía arxeologii AN

SSSR, no. 144. Moscow.

Hupalo, K. M. 1976. "Do pytannja pro formuvannja p

Arxeolohicni doslidzennja starodav' noho Kyjeva. Kie

arxeolohicnyx doslidzen'." Starodav nij Ky

noe iskussivo SSSR, 1977, no. 7. Moscow.

Icenskaja, O. V. 1982. "Osobennosti pogrebal'nogo obrjada i datirovka nekotoryx

ucastkov Saltovskogo mogil'nika." Maierialy po xronologii arxeologiëeskix

pamjaínikov Ukrainy. Kiev.

Ivakin, G. Ju., and Stepanenko, L. Ja. 1985. "Raskopki v severozapadnoj casti

Podóla v 1 980 - 1 982 ge. " In AIK. Kiev.

Jacob, G. 1927. "Arabische Berichte von Gesandten an germanischen Fürstenhöfe

aus dem 9. und 10. Jahrhundert." Quellen zur deutschen Volkskunde 1. Berlin

and Leipzig.

Jakobson, A. L. 1959. Rannesrednevekovyj Xersones. (=M1A, no. óJ). Moscow

and Leningrad.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 35 1

Janin, V. L. and Aleskovskij, M. X. 1971. "

novkeproblemy." IstorijaSSSR, 1971, no.

Karger, M. K. 1947. "Osnovnye itogi arx

Novgoroda." Sovetskaja arxeologija9. Mos

Kilijevyc, S. R. 1976. "Arxeolohicna karta K

doslidzennja starodavn ' oho Kyjeva . Kiev .

materialam arxeologiceskix issledovanij. Kiev

AIK. Kiev

Kirsten, E. 1958. ''Die byzantinische Stadt." Berichte zum XL Internationalen

Byzantinisten-Kongress. Munich.

Kolcin, B. A., and Janin, V. L. 1982. "Arxeologija Novgoroda 50 let."

Novgorodskij sbornik: 50 let raskopok Novgoroda. Moscow.

Komec, A. I. 1987. Drevnerusskoe zodcestvo konca X-nacala XII v. Moscow.

Kravcenko, N. M. 1978. "Issledovanie slavjanskix pamjatnikov na Stugne."

S lav jane i Rus' . Kiev.

tysjacolittja n.e. v Kyjivskomu Podniprov'ji."

Kropotkin, V. V. 1973. "Karavannye puti v Vostocnoj Evrope." Kavkaz i

Vostocnaia Evropa v drevnosti. Moscow.

Kuxarenko, Ju. V. 1957. "Raskopki na gorodisce i selisce Xotomel'." Kratkie

soobscenija o dokladax i polevyx issledovanijax Instituía istorii material1 noj

kuVtury AN SSSR, 68. Moscow and Leningrad.

Ljapuskin, I. I. 1947. "O datirovke gorodisc romensko-borsevskoj kul'tury."

Sovetskaja arxeologija 9. Moscow and Leningrad.

Mahura, S. S. 1932. "Rozkopy na hori Kyselivci

Instytutu istorii material' noj kul'tury VU AN 1. K

Maksymov, E. V., and Orlov, R. S. 1982. "Mohyl'ny

Kyjevi." Arxeolohija 41 . Kiev.

Mezentsev, V. I. 1986. ' The Emergence of the Podi

Kiev: Problems of Dating." Harvard Ukrainian

bridge, Mass.

Mocja, O. P. 1979. "Pytannja etnicnoho skladu naselennja davn'oho Kyjeva: Za

materialamy nekropoliv. ' ' Arxeolohija 3 1 . Kiev.

Movcan, 1. 1. 1985. "K voprosu o zapadnoj okolice drevnego Kieva." AIK. Kiev.

Noonan, T. S. Forthcoming (1988). "The Impact of the Silver Crisis in Islam upon

Novgorod's Trade with the Baltic." Berichten der Römisch-Germanischen

Kommission 69. Mainz.

Nosov, E. N. 1985. "Novgorod i Rjurikovo gorodisce v IX-X vv.: K voprosu o

proisxozdenii Novgoroda." Tezisy dokladov Sovetskoj delegacii na V

Mezdunarodnom Kongresse slavjanskoj arxeologii, Kiev, sentjabf 1985. Mos-

cow.

Petrov, N. I. 1897. Istoriko-topograficeskie ocerki drevnego Kieva. Ki

Pletneva, S. A. 1967. Ot kocevij k gorodam. Moscow.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

352 JOHAN CALLMER

èkspedicii. Moscow.

Pryxodnjuk (Prixodnjuk), O. M. 1980. "

pen'kovskix drevnostej." Tezisy dokl

Mezdunarodnom kongresse slavjanskoj arx

Radwarîski, K. 1975. Krakow przedlokacyjn

"Rozkopy v Kyjevi na hori Kyselivci v 1940

Rusanova, I. P. 1976. Slavjanskie drevnosti

Moscow.

Rybakov, B. A. 1969. "Put' iz Bulgara v Kiev." Drevnosti Vostocnoj Evropy.

(=MIA, no. 169). Moscow.

Sahajdak, M. A. 1981. "Pro sco rozpovila stratyhrafija Podolu." Znannja ta

pracja, no. 3. Kiev.

xeologii Kieva. Kiev.

rialy po xronologii arxeologiceskix pamjatn

Samojlovs'kyj, I. M. 1965. "Mis'ka bram

Kiev.

Sedov, V. V. 1982. Vostocnye slavjane v VI-XIII vv. (=Arxeologija SSSR). Mos-

cow.

Sovkopljas, H. M. 1954. "Nekotorye dannye o kostereznom remes

Kieve." KSIAANUSSR, no. 3. Kiev.

KSIAANUSSR, no. 7. Kiev.

Kyjivs'koho derzavnoho istoryënoho muze

8. Kiev.

108. Moscow.

goda. Moscow.

Stancev, S. 1960 "Pliska und Preslav: Ihre archäolo

Erforschung." Antike und Mittelalter in Bulgarien

Suxobokov, O. V. 1975. Slavjane dneprovskogo Lev

21. Kiev.

Tolocko, P. P. 1965. "Do topohrafiji drevn'oho Kyjeva." Arxeolohija 18. Kiev.

Vizantijeju u VIII -X st." Arxeolohicni doslidzennj

Kiev.

Kiev.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 353

Moscow.

drevnerusskix gorodov." 'nAIK. Kiev.

myra." Arxeolohija Kyjeva: Doslidzennja i mat

nijKyjiv. Kiev.

Xarlamov, V. A. 1985. "Issledovanija kamenno

Kieva X-XIIIvv." In AIK. Kiev.

Xvojka, V. V. 1913. Drevnie obitateli srednego Podneprov'ja i ix kul'tura

doistoriceskie vr emena. Kiev.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

354 JOHAN CALLMER

Fig. 1

Oro-hydrographic map of the Kiev area.

There are 20 meters between the equidistances.

The Starokyjivs'ka Hill is just northeast of center.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 355

Fig. 2

Topography of Kiev.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

356 JOHAN CALLMER

Fig. 3

Early medieval settlement in Kiev

(sixth-seventh centuries to the mid-ninth century).

This content downloaded from

80.2ff:ffff:ffff:ffff:ffff on Thu, 01 Jan 1976 12:34:56 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 357

Fig. 4

The kapysce according to Xvojka.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

358 JOHAN CALLMER

Fig. 5

The settlement of Kiev in the early tenth century.

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 359

Fig. 6

An early palace building in Kiev

(according to Xarlamov 1985).

/ '

/ i

i i

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

360 JOHAN CALLMER

Fig. 7

Chamber grave excavated in the cemetery

on the Starokyjivs'ka Hill.

o ~* °]

/ '

/ '

p /

O O.5M

IL

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 36 1

Fig. 8

The settlement of Kiev

in the late tenth and early eleventh century.

°_

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

362 JOHAN CALLMER

Fig. 9

The central part of the settlement

on the Starokyjivs'ka Hill in the late tenth century.

'

/ '' I:

X;

0 15 M

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ARCHAEOLOGY OF KIEV 363

Fig. 10

A suggested reconstruction of the center of Kiev

in the late tenth century after the completion of the Tithes Church.

■

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

364 JOHAN CALLMER

Fig. 77

Excavated sections of two tenth-century plots in the Podil.

I &

k-^i P

W loirTÌ Till ¡!

li IP Off

s li IP all a Off

§^^^^0 1/

This content downloaded from

80.233.34.88 on Sat, 08 Apr 2023 02:48:57 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Finkelstein I Etal 1993 Shiloh - The Archaeology of A Biblical Site100% (1)Finkelstein I Etal 1993 Shiloh - The Archaeology of A Biblical Site411 pages

- Becton Dickinson: Designing The New Strategic, Operational, and Financial Planning Process0% (1)Becton Dickinson: Designing The New Strategic, Operational, and Financial Planning Process2 pages

- Dorothy F Zeligs Psychoanalysis and The Bible A Study in Depth o 1979No ratings yetDorothy F Zeligs Psychoanalysis and The Bible A Study in Depth o 19794 pages

- The Archaeology of The Early Islamic Settlement in Palestine - Jodi Magness - 2003 - Eisenbrauns - 9781575060705 - Anna's ArchiveNo ratings yetThe Archaeology of The Early Islamic Settlement in Palestine - Jodi Magness - 2003 - Eisenbrauns - 9781575060705 - Anna's Archive246 pages

- Archaeology of The Slavic Migrations Michel KazanskiNo ratings yetArchaeology of The Slavic Migrations Michel Kazanski22 pages

- LLU Landscape Architect Art Vol 19 2021-43-51No ratings yetLLU Landscape Architect Art Vol 19 2021-43-519 pages

- The Normans and The Khazars in The South of Rus'No ratings yetThe Normans and The Khazars in The South of Rus'9 pages

- Russia and Ukraine in Their Historical EncounterNo ratings yetRussia and Ukraine in Their Historical Encounter11 pages

- Thomas Noonan-The Monetary History of Kiev in The Pre-Mongol Period PDFNo ratings yetThomas Noonan-The Monetary History of Kiev in The Pre-Mongol Period PDF61 pages

- (American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 49 Iss. 3) Vesvolod Avdiyev - Achievements of Soviet Archaeology (1945) (10.2307 - 499622) - Libgen - LiNo ratings yet(American Journal of Archaeology Vol. 49 Iss. 3) Vesvolod Avdiyev - Achievements of Soviet Archaeology (1945) (10.2307 - 499622) - Libgen - Li6 pages