41724744

41724744

Uploaded by

Gokhan MermiCopyright:

Available Formats

41724744

41724744

Uploaded by

Gokhan MermiCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

41724744

41724744

Uploaded by

Gokhan MermiCopyright:

Available Formats

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AND MEROITIC AGES

Author(s): G. A. Wainwright

Source: Sudan Notes and Records , 1945, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1945), pp. 5-36

Published by: University of Khartoum

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41724744

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Sudan Notes and Records

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AND MEROITIC AGES

By G. A. Wainwright

The Napatan Age

The pyramids of both the earlier and later capitals of Ethi

Napata and Meroc, have been, cxcavated. Hence when the

results are published in detail we shall have a complete record of the

development generation by generation of the objects and materials

that were regularly deposited under each of them at their foundation.

Model tools of bronze and iron are among such deposits.

At Napata the scries of pyramids begins with Kashta, c.75 o>-j^

B.C., and bronze models are the regular thing until at last after four

hundred years we reach Pyramid xiii, that of Harsiotef, c. 397-362 B.C.

Here at last iron models are found for the first time among the usual

bronze ones. Iron as well as bronze models are similarly found in

Pyramid xiv1, that of Akratan, to whom Reisner allots the years

342-328 B.C., and whom he puts as the immediate predecessor of Nastas-

en, with whom the dynasty of Napata came to an end in c.308 B.C.2

Pyramid' xv, that of Nastasen himself, had no deposits,3 though no

doubt, if it had had, it would have have had some iron like those of

the two previous kings. Thus, the valuable point is made that in

the period c.750-308 B.C. iron does not appear at Napata until the

years between c. 397-362 B.C.

The evidence of the deposits in the pyramids is confirmed by the

fact that Tirhakah's (688-663 B.C.) foundation deposits in his temple

i. Reisner in Harvard African Studies ii (1918) pp. 59, 43, and PI. viii, 2.

2. Id. in J.E.A., ix (1923) p. 75. In the original publication where the iron is

mentioned, Pyramid xiv is spoken of as belonging to Piankhalara ( ?) , who reigned between

Harsiotef and Nastasen (Harvard African Studies ii, p. 63). Piankhalara now proves to

have been buried in another cemetery, that of Kurru (J.E.A.,. ix, p. 75 No. 24), which

does not seem to have been published yet.

3. Id. in Harvard African Studies ii, pp. 41, 59.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

6 SUDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

at Napata were of gold, silver, bronze and lead,4 but t

Nor was there any iron, though there was plenty

deposits óf his next succášsoř, Atíanersa, c. 653-643

the great days of Ethiopia, those of Shabaka and Tir

B.C., she was clearly as much, or more, in the Bronz

It is a warning against giving too early a date to the scra

now come under discussion.

The first of these is the iron from the Sanam cemetery at Napata.

Here the iron proves to be somewhat earlier than that of Harsiotef,

indeed the few earliest specimens are likely to be as much as two hundred

years earlier. To obtain results it is necessary to divide the graves

into as many groups as possible with their sequence. Such indications

as there are seem to be

1. Cave graves are the earliest, beginning not earlier than Piankhy,

c.744-710 B.C.«

2. The larger rectangular graves,7 on the whole are somewhat

later.

Both these classes contained mummies, or bead network or car-

tonnage, indicating that mummies had originally been there.» Pottery

of Type I was often found in these graves. It is dated by the found-

ation deposits of the pyramids at Napata (Nuri), where it disappears

after Amtalqa, c. 568-553 B.C.» These graves may, therefore, be

said to be earlier than that date.

3. Extended and contracted burials in the sand. These had

not bèen mummified.10

The contracted burials almost monopolize the Type III pottery

in all its varieties. This dates the burials as not earlier than the

4. Griffith in L.A.A.A. ix, p. 81 and PI. xxii. This particular portion of the great

site at Napata is called Sanam, pp. 67, 79.

5. Reisner in I.E. A., v, p. 107.

6. Griffith in L.A.A.A., x, p. 83.

7. Cf. 'à.,-op. cit., pp. 83, 85, 89.

8. pp. 84, 85.

9. pp. 86, 89. Cf. also p. 87 where the mummies are thought roughly to date trom

Piankhy to Amtalqa.

10. p. 89.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AND MEROITIC AGES 7

reign of Amtalqa, c. 568-553 B.C. and probably later, for this p

only begins in the foundation deposits of this king's pyram

Napata (Nuri).11 It seems probable, however, that some

extended non-mummified burials begin in the period before Am

4. The end of the cemetery seems to come perhaps a cen

after the Persian conquest of Egypt.13 That would p

to about 400 B.C., and a hundred years before the tr

ference of the capital from Napata to Meroe.

With this meagre skeleton of a chronology we must do wh

can at assessing dates for the few scraps of iron which were fo

the cemetery. The following is the list of graves with the iron

found in them separated into those which are probably before A

and those which are probably after his time. Each group is arr

as far as possible in order of the graves' degradation, and he

one supposes, of their probable sequence. The page number is a

in each case to facilitate reference.

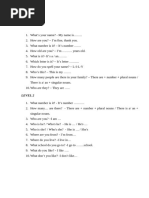

Grave Iron object Description of Grave and Burial ! Page

Before Amtalqa i.e. before c. 568-553 B.C.

but well after Piankhy, c. 744-710 B.C.

968B bangle small cave j 162

714 arrow rect. brick, cartonnage, j 157

pilgrim flasks. :

523 tweezers rect. brick, mummy. 152

963 remains. rect. brick, rich deposits, 86,120,162.

ointment spoon.

587 arrow brick, extended. 153

701 hook small brick, extended. 126,157

162 tweezers rectangular. 145

After Amtalqa i.e. after c. 568

but before c. 400 B.C.

706 large tweezers, ' sand, extended. ! 126,157

razor (?)

771 tweezers sand, extended. ! 158

646/7 razor j sand, rect. contracted ' 126,154

. Type III pottery.

671 hoop staples rect. contracted. 155

362/1 razor sand, contracted. j 126,149

Type III pottery.

899A j small tweezers ¡ sand, contracted. 126,161

632 small earrings | shallow, sand, roughly rect., 123,153

contracted.

1042 razor irregular, contracted. 164

768 2 bangles small irregular, contracted. 158

1366 blade sand. 168

77 tanged spearhead shallow 126,143

ll> p. $9. 12. p. 89. 13. p. 90.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

8 SÜDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

On considering the above table certain point

In the first place the majority of the graves th

datable to a time after Amtalqa. That this a

specimens is in general correct is supported by t

with the exception of one small grave, No. 968 B

caves, which form the earliest group of all.14 N

that it does occur to some extent in the rectan

which would be a slightly later group, but, as

the iron probably comes mostly at the end of th

hand we find that most of the iron comes from the extended and con-

tracted burials in the sand. These are the latest of all the graves.15

The lateness of the appearance of iron in the series of rectangular

bricked graves is suggested by its general absence in those which con-

tained the Syro-Cappadocian cylinder seal and the piilgrim flasks.14

It seems probable that these objects would have been imported in the

period of Shabaka and Tirhakah, say about 710-663 B.C., when

Ethiopia was in close contact with the Assyrians. With only two

exceptions the cylinder seal and the pilgrim flasks were found in

rectangular graves with extended burials ; one even had a mummy,

and practically all the graves were bricked. Only one pilgrim flask,

No. 1033, came from a contracted burial. The indication, therefore,

is that the graves with northern imports, belong to the earlier, but not

the earliest, portion of the cemetery, and it is worthy ci note that only

one specimen of iron was found with them. It was the arrowhead in

No. 714, which also had originally contained a mummy. The evidence,

therefore, is that iron did not begin to- appear until the end of the

' pilgrim flask ' period. Hence, the iron shews signs of being later

than C.710-663 B.C.,

On the other hand the greater part of the iron comes from the

time wheft mummification had ceased, i.e. from the extended burials

14. p. 8g.

15. pp, 84. 09.

16. Cylinder seal, Grave 396» Hogarth and Griffith in vui, fi. xxv, 19 and

pp. % 1 5» 216; Pilgrim flasks in Graves 224, 419» 428, 458, 522, 714, 1009, 1033, 1100 aiid

cf. the Cypriote vase in 1416, Griffith i nL.A.A.A.tx, pp. 146-169. No. 1009 was irregular.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AND MEROITIC AGES 9

in the sand and also from the contracted burials which seem to close

the history of the cemetery.17

Thus, taking it all in all, we shall hardly be wrong if we suppose

that the few specimens which come from before Amtalqa's reign,

c.568-553 B.C., are not much earlier than that. In fact, as will be seen

in the next pages, there is reason to suspect that they would come

from the reign of his immediate predecessor, Aspelt. This is the time

to which the iron in the Treasury may be dated, if indeed it belongs to

the Ethiopian period. It was also in Aspelt's reign, c. 593-568, that

the iron-using Ionians and Carians came up into Nubia with Psametik II.

On the other hand, the majority of the iron pieces from the cemetery,

as the table shews, come from after Ámtalqa's period. The proportion

is 7 before Amtalqa as against 11 after his reign, i.e. 39% before and

61% after. And small enough too is the grand total of both groups,

for of the 1550 odd graves that were dug, representing a probable span

of some 350 years, only 18 produced any iron at all. What was dis-

covered was only in the form of very small and unimportant things,

in fact mostly for toilet use. Herodotus' statement, VII, 69, about

the Ethiopians in Xerxes' army, is in complete agreement with this

state of affairs. He says that their arrows were tipped ' not with iron,

but with a sharpened stone, that stone wherewith seals are carved;

moreover they had spears pointed with a gazelle's horn sharpened to

the likeness of a lance.' In other words Herodotus tells us that for

all intents and purposes the Ethiopians were still without iron in 480 B.C.

• Before leaving the subject it should be remarked that both the

arrowheads, Nos. 714, 587, come from before Amtalqa's reign. This

makes them exceptionally early, for such things do not begin to be-

come common for another six hundred years or more, see p. 29. The

one that is figured, No. 587, PI. xxxv, 9, is of the non-barbed type,

which is comparatively rare at the later date.

The results obtained from this study of the cemetery go far to

elucidate the state of affairs at the Treasury at Napata, and, if the finds

really are of Ethiopian date, they provide singular confirmation of

17. Griffith in op. cit., pp. 84, 89.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IO SUDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

these results. In the Treasury there was

a fragment of Piankhy's loot from Herm

iron tools, a few objects with the names of

of small odds and ends.1» The names are

B.C., Shabaka c.710-700 B.C., Atlaners

seken c.643-623 B.C., and Aspelt c.593

potsherds of Meroitic date there was no

any period, and it is important to not

potsherds there was no indication that

in Meroitic days.19 Hence, the iron to

either of the time of those kings whose

Meroitic date.

Under these conditions the four iron tools are either Meroitic or

•fairly early Ethiopian. It is of course always possible that they date

from the time of Shabaka and Tirhakah. In Egypt this was the

time of the Assyrian conquests, and in Tirhakah's reign the first group

of iron tools to be recorded in that country was left behind at Thebes.

The tools are of non-Egyptian type and were in company with an

Assyrian helmet of well-known shape.80 They must, therefore, have

been left behind in one of Asshurbanipal's two occupations of Thebes

in 667 and 663 B.C.21 Asiatic influences also percolated up into

Ethiopia at this time, as may be seen in the presence there of the Syro-

Čappadocian cylinder seal and the pilgrim flasks, which have already

been discussed. But it has just been pointed out that in the Sanam

cemetery at any rate iron was not used as early as that. The occurrence

18. Griffith in L.A.A.A., ix, pp. 118-124 and Pis. liv-lxii.

19. Id., in op, cit., p. 118. The dates are added from Reisner in J.E.À., ix, p. 75.

20. Petrie, Six Temples at Thebes , PI. xxi and pp. 18, 19. Two of these heavy iron

chisels with shoulders and handle-rings are of the same type as the one found at Buhen

in the plundered cemetery of the Eighteenth Dynasty and later. It is, however, more

probably an import of Romano-Nubian, rather than of, Assyrian date, for a Romano-

Nubian pòt was also found in the gràve (Macl ver and Woolley, Buhen , p. 130, p. 171 Tomb

J 22 and PI. lxiii and p. 224 No. 10338). It is a regular type of Roman chisel, Petrie,

Tools and Weapons , PI. xxi, 118 and cf. 123. On the other hand it is not an X-Group

type, cf. Emery and Kirwan, The Royal Tombs of Bajlana and Qustul, pp. 336, 337.

21. Cambridge Ancient History 111, pp. 283, 285.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AND MERÓITIC AGES II

of the single arrowhead in grave Nö. 714 is an isolat

which cannot vitiate the general trend of the rest

On the other hand the latest of the royal names i

who was the immediate predecessor of Amtalqa, bef

iron was already just beginning at the Sanam cemeter

likely that this would be about the date that iron mi

where, a,nd so Aspelt's reign, c. 593-568, is quite a lik

to appear in the Treasury.

It is, moreover, scarcely a mere coincidence that a

the Pharaoh Psametik II, .593-588 B.C., sent an expe

This was rio small affair, but impressed posterity. A hu

years later Herodotus, II, 161, found it worth mentip

wise quite unimportant and short reign, whereas he

the expedition which this same king made into Syri

hundred and fifty years later again a Jewish writer of

to it claiming that there were Jews among the

therefore, evidently knew such a detail about it as t

Semites among the mercenaries, and supposed th

Jews, though we now know them to , have been

information must have come to him from some s

Herodotus, who does not mention the composition o

expedition has also left unusually full records of its

graffiti which the foreigners scribbled on the legs of

at Abu Simbel, some forty miles north of Wadi Hai

Cataract. One of those in Greek leaves no doubt t

to this campaign, for it names the king, Psametic

Psamatichos son of Theocles, Potasimto the leader of

22. We know of this from Egyptian sources, F.LI. Griffith, Cata

Papyri in the John Rylands Library Manchester iii, pp. 92-97.

23. H. St. J. Thackeray, The Letter of Aristeas (1917) p. 24 §

probably written about the year 100 B.C., pp. xiii, xiv.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12 SUDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

and Amasis tbe leader of the Egyptia

are well-known from Egyptian sourc

formed of eight written in Greek,

Phoenician.2* The Greeks prove t

immediate neighbourhood,27 just as

mercenaries all through the Twenty

The Carians got at least as far up

of the Second Cataract, where opposi

of their graffiti has been found. Thi

relic we have of them.29

24. It has been published, translated, and discussed many times. Probably the

translation in the Cambridge Ancient History iii, p. 301 is the most readily accessible to

the general reader. It runs ' When king Psametichos came to Elephantine, those who

sailed with Psametichos son of Theokles wrote this ; now they came above Kerkis as

far as the river let them go ; and Potasimto led the foreigners, Amasis the Egyptians ;

and Archon son of Amoibichos and Pelekos son of Oudamos (or Axe son of Nobody)

wrote us' (i.e. the letters). M.N. Tod, A Selection of Greek Historical Inscriptions, p. 7

rejects the emendation ' son of Nobody ' in favour of the. traditional reading ' son of

Eudamus.' ' Kerkis ' probably represents Kertis, i.e. the Egyptian qrti at the First

Cataract where the Nile of Egypt was considered to rise. ' As far as the river let them

go ' of course means 'as far as the Second Cataract,' E.L. Hicks and G. F. Hill, A Manual

of Greek Historical Inscriptions (1901) p. 5.

25. Rowe m Annales du service des antiquités d bgypte (Cairo, 1930) xxxvm, pp. 157-

194 and Pis. xxii-xxvi. Each of them formed his own second name on Psametik II's

throne-name, and in a number of other ways identify themselves with the leaders of the

expedition to Nrçbia^ pp. 169, 170. 173.

26. Sayce in Trans. Soe. Bibl. Archy ix (1893) pp. 123, 144, 145. lhe Greek ones

have been published and commented on by Hicks and Hill, op. cit., pp. 4, 5, and more

recently by Tod, op. cit., pp. 6, 7.

27. 1 wo of the graniti were written by men trom tne loman cities 01 1 eos and coiopnon

respectively. Another was written by a man from Ialysos in Rhodes just off the Carian

coast and south of the two former cities. It was a Dorian colony, hence Homgusob, the

writer of another graffito in the Dorian dialect (Sayce in Trans., p. 124), would have come

fiom that neighbourhood also and not from the mainland of Greece. Further the long

graffito quoted above uses several Doric forms, though the alphabet in which it is written

is Ionic, Tod, op. cit., p. 7 Yet again it has been pointed out that the general himself,

Psamatichos son of Theocles, was no doubt the son of one of Psametik 1's original mer-

cenaries, Theocles haying evidently named his son after his royal master, Camb. Anc.

Hist, iii, p. 301. His name shows Theocles to have been a Greek, not a Carian, hence

an Ionian, so that his son, Psamatichos the general of the army in Nubia, would have been

of Ionian extraction. Thus, five out of the eight Greek soldiers came demonstrably from

the same south-western corner of Asia Minor as did their companions in arms the Carians.

Moreover, they were led by a general who also with little doubt originated from the same

district. Though Herodotus does not mention them, Asshurbanipal says that Gyges,

king of Lydia, sent soldiers to help Psametik I revolt from the Assyrians (E. Schräder,

Keilinschriftliche Bibliothek II, pp. 173, 177, 11. 95, 114), and a graffito in what appears to

be Lydian has been found at Silsilah iji southern Egypt (Sayce in Proc. Soc. Bibl. Archy ,

1895, pp. 41-43 ; 1905, p. 123).

28. ±idts il, 152 lor ťsametik X ; 11, 103 Apnes ; 11, 154 Amasis ; in 111, ix, tney are

merely called Greeks in Psametik iii's unsuccessful battle against Cambyses. Cf. note 30

infra for Necho.

29. Sayce in Proc. Soc. Bibl. Archy., 1910, p 261. One of the Phoenicians says that

he ascended the river as far as Soharu, a place which unfortunately is not yet identified,

Id. in Trans. Soc . Bibl. Archy., ix (1893), P- I24-

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AND MEROITIC AGES 1 3

In Egypt itself the Carians and Ionians are mentione

each reign from Psametik I, 663 B.C., to Psametik III, 52

They have left records of themselves all over Egypt.81 H

not surprising that in Nubia also their presence was no passi

menon, in fact they were established as garrisons througho

country between the First and the Second Cataracts. At Buhen

opposite Wadi Haifa itself, about five or six miles north of Mainarti,

there are more Carian graffiti.32 These in themselves are evidence

of a permanent occupation, for Sayce says that the script for-

bids us to think that they were the work of the Abu Simbel ex-

pedition. He says the difference in writing implies that a garrison

must have been maintained in Nubia in the Twenty Sixth Dynasty

or in the Persian period which followed.83 Presumably the sending

up of re-inforcements for such a garrison would lie behind the state-

ment in one of the Greek graffiti ' what time the king sent the army

for the first time '34 It must mean that the writer came with the

original army and that other drafts followed.

Archaeologically there is evidence of this occupation' of Nubia by

the northerners, and also that they were using iron. Ikhmindi is about

half-way between Aswan and Abu Siinbel, and in Meroitic times at

any rate, was the site of a fortress. The cemetery, though much

30. See note 28 above. Though the Carians and Ionians are not mentioned by name

in Necho's reign, yet we are told that this king dedicated his corselet to Apollo of Bran-

chidae (Hdts ii, 159) on the coast of Ionia.

3 1 . Besides those mentioned in the text there are those at Memphis, Sayce in P.S.B. A . ,

1906, pp. 173, 174. Trans., ix (1886) pp. 145-147, and cf. p. 124 ; Abydos, Id. in Trans.,

147-153 ; Silsilah, Id., in P.S.B. A., 1895, pp. 40, 41, 207 ; 1905, p. 124 ; 1906, pp. 171-

173 » 1908, p. 28. Inscriptions on objects from Naukratis, Id. in Trans., p. 153 ; Sais,

Id. in P.S.B. A., 1905, p. 125 ; Zagazig, Id. in Trans., p. 147, and cf. p. 126 ; Hu, Id. in

P.S.B. A., 1905, p. 126 ; from an unknown provenance, Id. in. P.S.B.A. , 1905, pp. 124,

125. One of those from Memphis proves to be that of one of the Abu Simbel mercenaries,

Mesnabai son of Skha, who fortunately identifies himself by giving his father's name

in each case. He states that he made his tomb (at Memphis), Sayce in Trans., p. 146,

No. ii, 4 and cf. p. 144, No. i, 1.

32. Id. in P.S.B.A., 1895, pp. 39-40.

33. Id. in op. cit., p. 39. At the northern frontier of Nubia a garrison established by

Psametik I in the middle of the seventh century was still maintained by the Persians at

Elephantine at the First Cataract at least as late as about 450 B.C., Hdts ii, 30.

34. Camb. Anc. Hist., iii, p. 301.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

14 SUDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

plundered, still included a few graves of the ' E

in Egyptian terms of the Twenty Sixth Dynasty,

age of Psametik II. It is, therefore, significan

graves produced several iron spears36 of a type

is well-known from the settlements of the fo

Defennah (Daphnae) and at Nebeshah not far off,

from their settlement at Naukratis on the other side, of the Delta.38

This is not the only connection that there is between the Nubian iron

and that of the Carian and Ionian mercenaries. Besides this all the

iron ingots that have been found in Nubia are of the shape and length

of one from Naukratis though not so heavy. It is unfortunate that

we have none from the early days of the Meroitic smelting industry

but only from the X-Group Age, so that nearly twelve hundred years

separate the two lots.39 But still we know that Africa is a conservative

place.

In view òf all this it is likely that these iron-using foreigners from

the north would have introduced some knowledge of iron to the

Ethiopians. Its rarity for at least two hundred years afterwards

suggests that perhaps it would not have been a knowledge of how to

smelt iron that they brought but only that of the ready-made metal.

The Carians and Ionians undoubtedly taught the Egyptians the use

of iron, and it may be that it was from them at secondhand that the

Ethiopians acquired the knowledge of smelting iron and making it

up into ingots of Carian and Ionian shape, though smaller. Further,

it cannot be doubted that, if the iron implements in the Treasury at

Napata are Ethiopian and not Meroitic, they belong to the period

of Aspelt and not to that of Shabaka and Tirhakah. They would,

35. C.M. Firth, The Archaeological Survey of Nubia 1910-11, p. .186 and cf. p. 176.

36. Id., op. cit. pl. xxix, a, i, 2. Fig. 3 of similar type is not mentioned in the text.

37. Petrie, Defenneh, PI. xxxvii, 4 and p. 77 Nebesheh, Pl. iii, 17 and p. 21 ; both

are bound with Tanis ii. Note that the bronze spears from Nebeshah, Nos. 1, 2, 14, 17, 29,

are still of the native Egyptian type known elsewhere at an earlier date, as for instance,

Petrie, Wainwright and Mackay, The Labyrinth, Gerzeh and Mazghuneh, PI. xxii, 9 and

p. 28.

38. Petrie, Naukratis i, PI. xi, 27 and p. 39

39. For the details see p. 33 note 40.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IBON IN THE NAPATAN AND MEROITIC AGES 1 5

therefore, be contemporary with the earlier pieces of iron that we

found in the Sanam cemetery at Napata, and with the coming of th

Carian and Ionian mercenaries.

Apropos of all this we may add that the foreign mercenaries wer

very ready to establish themselves in Nubia or even in- Ethiopia. In

the reign of Apries, 588-569 B.C., who was Psametik II's successo

we have the inscription of Nesuhor. He was ' Governor of the Door

of the Southern Countries,' i.e. of Elephantine at the First Cataract

He narrates how ' the mercenaries, Libyans (?), Greeks, Asiatics and

foreigners ' intended to mutiny and to decamp to Shas-heret, an uni

entiiied region of Upper Nubia, but he succeeded in preventing them

from doing so.*4

In 525 B.C. or so other northerners invaded Ethiopia, i.e. the

Persian under Cambyses,41 and they also would have been iron

users. But archaeologically there are no signs of Cambyses' presence

40. J, H. Breasted, Ancient Records iv, §994. Naturally it has been noticed befor

that this i» what the ' Deserters ' had been successful in doing under Psametik i in t

previous century (Hdts ii, 30, 31). These people clearly got as far south as the Bahr e

Ghazal and the Bahr el- Arab, for Herodotus says categorically that the Nile was known

as far as ther country, where ' it flows from the west and from the sunset quarter.' Th

could not, tlerefore, have settled in Sennar or even Abyssinia as is often supposed. I

by " Meroe, which is said to be the capital of the other Ethiopians" Herodotus reall

means Meroe and not Napata, the distance on to the Bahr el Ghazal is about three quarte

of that from Elephantine to the city. If, however, he means Napata, which in his da

was still the capital, the two parts of the journey aré just about equal, as he says. Th

' Deserters/ however, were native Egyptians nçt foreign mercenaries, and so would not

have brought 1 knowledge of iron with them.

41. Herodotus iii, 25, tells how Cambyses marched up into Ethiopia and in iii, 97

says that the northern Ethiopians brought gifts but no settled tribute to Darius, an

Darius in his ovn funerary inscription includes the Kushiya (Cushites, Ethiopians) amon

his tributaries (Pauly-Wissowa, Rcal-Encyclopadie, s.v. Kambyses, col. 1817). Later

they had to send a contingent to Xerxes' army (Hdts vii, 69). Though in connection

with the conquest of Ethiopia Herodotus does not mention Meroe, by the last centur

B.C. Cambyses had become intimately connected with that city. Diodorus says, i, 3

that he founded Meroe and named it after his mother. Strabo, xvii, i, §5, says that

advanced as far as Meroe, and gave the name to both the city and the island because hi

sister Msroe, or as some say, his wife, died there. In any case, he says the name was give

in honour of a woman. Writing about A.D. 93, Josephus says in The Antiquities of t

Jews, ii 249, that Cambyses renamed the city ' Meroe ' after his own sister. By the secon

century A.D. Ptolemy entered in his Geography ' Storehouse of Cambyses ' as the name

of a vilkge, which he puts far up in Ethiopia above the Third Cataract about one hundre

miles dDwn the river from Napata (C. Muller. Cl. Ptolemaei Geographia, p. 770, Bk. iv,

§5). II must be remembered of course that like Sesostris and Alexander Cambyses i

due time became the hero of a complete legend. For the Coptic (i.e. Egyptian Christian

version see Schäfer in Sitzungsberichte K. Preuss. Ak. Wtss. zu Berlin, 1899, pp. 727-74

In spitt of a certain similarity of names, the defeat of ' the man Kambusauden ' which

is recoided by the Ethiopian king Nastasen (H. Schäfer, Die A äthiopische Konigsinschrif

des...mstesen des Gegners des Kambyses, p. 18. and the commentary pp. 45-50) canno

refer t> Cambyses' expedition, for a matter of two hurj^red years separates the two events

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 6 SUDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

in Ethiopia, and in any case a military expedit

the cultural effect that a long-continued occu

the Carians and Ionians, must have had.

This long excursus on the date of the iron in the Treasury at Napata

and the cause of its appearance there at so comparatively early a date

makes it almost certain that, if it was Napatan and not Meroitic, it

belonged to the reign of Aspelt, c.593-568, or even later, and was the

result of the invasion and subsequent garrisoning of Nubia by Psametik

II's Carians and Ionians. We must now devote a few lines to the litile

that can be said about the objects themselves. They only consisted

of the blade of a large adze or small mattock with a ring-socket an

axe-head, a triangular blade, and a socketed knife-like blade.42 The

fact that two of the implements are socketed is important, for tiiis is

a northern technique and not Egyptian, for Egypt was very stow in

adopting this method of hafting its tools. In this they are in accord

with what has gone before and show themselves to be probably imports

to Ethiopia by way of Egypt from further north, or perhaps it more

suggests that the tools are late, i.e. Meroitic, for mattocks vith ring

sockets occur elsewhere at this time.*3 Unfortunately the axe-head

type has far too long a history to give any indication as tc its date.

Egypt preferred the old-fashioned method of lashing the blade to its

handle, and it was for this kind of hafting that the axe-head was made,

for it has the lugs necessary for binding it to the handle. The type

had been evolved in Egypt about the Twelfth Dynasty, c.1900 B.C.,

from a. still earlier one. For many centuries it was made in bronze,

and then in due time in iron. A very çarly Egyptian example in iron

can probably be dated to about 800 B.C.44 In Ethiopia the type had

42. Griffith in L.A.A.A., ix, pp. 118, 119 arid Pl. liv, Nos. 1, 2, 3,

43. A similar mattock was found in the Meroitic (Romano-Nubian) cemetery at

Karanog, Woolley and Maclver, Karanog, PL 35, No. 7459. Bates and Dunham, Ganmai,

PL Ixvii, fig. 29 ; Emery and Kirwan, The Royal Tombs of Ballana and Quštul , PL lixxiii

B. 80/57,

44. Petrie, Tools and Weapons, pp. 8, 9 §12 arid Pis. ii, iv, v, Nos. 72, 73, 122-132.

Nos. 72, 73, 131, 132, 133 are of iron.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AND MEROITIC AGES 1 7

naturally long been known in bronze4®, and, made of iron, it was

in the Meroitic (Romano-Nubian) Period.44

The results of the foregoing enquiry are that :• -

1. There was no iron in Ethiopia's great days, those of Piankh

Shabaka, and Tirhakah, c. 744-663 B.C.

2. Iron spear-heads were found at Ikhmindi, where in later da

at any rate there was a fortress. They were of the shape used by

Carian and Ionian mercenaries. They, therefore, date to the time

Psametik II, c. 593-588 or of his successors down to about 525 B.C

3. At the Treasury of Napata, if the iron is not Meroitic, it p

bably begins under Aspelt, c.593-568 B.C. or during the next hun

years.

4. In the Sanam cemetery at Napata iron probably just beg

slightly before Amtalqa's reign, c.568-553 B.C., but most of the l

that there was is later than that.

5. In 480 B.C. the Ethiopians were still without iron tor all

practical purposes.

6. Iron does not appear in the foundation deposits of the pyra-

mids at Napata until well after all this, i.e. in those of Harsiotef, c. 397-

362 and Akhratan, c. 342-328 B.C.

Thus, it seems probable that a knowledge of iron came to Ethiopia

through the Ionian and Carian mercenaries from Egypt, and that then

it was perhaps only a knowledge of the ready-made metal that was

brought and not that of how to smelt it from the ore.

Thus, in the persons of these Ionian and Carian mercenaries iron

was brought to Ethiopia by very much the same people as had brought

it to Palestine long before and were to bring it long afterwards to the

45. For instance examples dating to the late Eighteenth or early Nineteenth Dynas-

ties, c. 1350 B.C., were placed in the foundation deposits of the temple B. 500 at Napata

(Gebel Barkal), Reisner in J.E.A. , iv, p. 222 and PI. xlv, 2. Axes of this type were also

made long after Aspelt's reign, having been found in the foundation deposits of Pyramids

xi, xii, xix, xiii, xiv, xxix, xxxii, xxxi at Napata (Nuri), Reisner in Harvard African Studies

ii, Pis. viii, X. The earliest of this series of pyramids are No. xix dating to c. 458-453 B.C.,

Reisner in J.E.A., ix, ç. 75, and No. xxix, a queen's tomb which is contemporaneous with

it, Id. in Harvard African Studies ii, p. 12.

46. Griffith in L.A.A.A., xi, PI. lxxi, No. 9 and p. 179 and xii, p. 160 No. 2733. It

came from a grave of the A class, i.e. of the first century B.C. to the first century A.D. ;

Karanog, Woolley and Maclver, Karanog, PI. xxxv, No. 7299; Bates and Dunham,

Excavations at Gammai (pubd. in Harvard African Studies , viii) PI. lxvii, fig. 30.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

1 8 SUDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

coasts of Somaliland. The earlier of these peoples w

who before 1200 B.C. were arriving in Palestine at the

Age and the opening of the Iron Age.47 The Egyp

this time shew them as an Asianic people among o

origin,48 and in Palestine their pottery is of ' for

northern and western connections.49 It. may

Philistines came from Pisidia50, which is only roun

Ionia and Caria. On this ocasion they came as ra

any rate of the tribes were drafted into his arm

In both characters they are entirely comparable

Carians who raided Egypt and were taken into his s

about 663 B.C. In the sixth century B.C. the Io

came as mercenaries to Nubia, and iron begins to b

as it did in Palestine when the Philistines were ar

century B.C. mercenaries went to the coasts o

Somaliland to hunt elephants for the Ptolemies

the natives of those parts to the value of iron. Th

across the Mediterranean. Two at least of the leaders are known

to have come from Pisidia, though now most of them come from

further to the west.81 Three hundred years after that, in the f

century A.D., ' Greeks' were trading up and down the Red Sea

actually importing ready-made iron there as an article of commer

47. Petrie, Beth Pelet i, pp. 6-9. For their iron work see pp. 7. 8, §23 and PI.

90, 96.

48. Wainwright in L.A.A.A. , vi, p. 64 note 4; Id, in Journal, of Hellenic Stud

li, pp. 10-13, 15, 16; Id. in Palestine Exploration Fund : Quarterly Statement, 193

pp. 206-216.

49. Petrie, op . cit., p. 6 §18 and PI. xxiii. Most unfortunately the homeland o

very distinctive pottery has not yet been found.

50. Wainwright in Palestine Exploration Fund : Quarterly Statement, 1931, p

51. Id. in Man , 1942, pp. 84, 85. Pisidians were so numerous in Ptolemaic Egy

that a district in Alexandria was called Aspendia, after Aspendos the port on the P

coast. No doubt it was at Aspendos that they were recruited, Hall in The Classical R

xii p. 278.

52. W.H. Schoff, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, pp. 24-26 §§6, 8, 10. As

author wrote in Greek he would have been a ' Greek ' writing for guidance of other

' Greeks.' For the ' Greek ' colony on the Island of Socotra see p. 34 §30 and note on

pp. i33ff. For the way in which trade all round the shores of the Arabian Sea, and even

to the Far East, was in ' Greek ' hands see E.H. Warmington, The Commerce- between the

Roman Empire and India, passif.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AND MEROITIC AGES 1 9

The Meroitic and X-GrouP Ages

Having studied the question of iron in the earlièr, or as it is call

the Napatan period, we now come on to iron in the later, or Mero

age. In Napatan times it did not begin at all until the middle of th

sixth century B.C., and did not appear in the foundation deposits

the pyramids until the middle of the fourth century, that is to s

in the reigns of the last kings of that dynasty. No doubt had t

finds in the pyramids been published, it would have been seen that i

went on gradually increasing in use generation by generation.

as they have not, we are thrown back for the history of iron in t

Meroitic period on the other finds. These are those of the slag hea

at Meroe itself, and the objects in the cemeteries of the ordinary people

While these give a perfectly sound view of what was happening th

cannot of course be so detailed as one built up generation by gener

ation. While it will be shewn that the slag heaps at Meroe begin ve

early, strangely enough the cemeteries of the ordinary people do

seem to begin before a time running from the first century B.C.

the first century A.D. In this way there is a gap of some three hund

years in which no burials of ordinary people seem to have been fou

This gap covers all the period of the earlier kings of the Meroitic dynas

and comes down to the destruction of Napata by Petronius in B.C.

Perhaps it may be accounted for to some extent by the fact th

excavations have been carried on almost exclusively to the north o

Meroe. If we had any information as to what was going on to

south round Meroe itself, we should very likely be able to fill in t

lacuna.

By the Meroitic age, which begins in the first century B.C., the

most astonishing change had come over the scene. Smelting works

on a gigantic scale had already been initiated at Meroe by the middle

of that century or even earlier, and we are fortunate in being able

to fix a terminus ante quem. The immensity of the scale on which

operations were carried on has been well described by both Garstang

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

20 SUDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

and Sayce. Garstang says ' The buildin

was of the Meroitic style, cover jpg the to

itself was one of a kind which freely ab

largely composed, it would seem, of the

working and similar industries. The surf

covered with black stone-like slag ' left fr

of iron ore ' 1, and the great quantity of

dence of very extensive workings continu

In this mound the deposit of such slag a

in depth, and numerous broken objects

in it..'®

Mr. Arkell, the Commissioner for Archaeology, visited Meroe in

February 194Ó and kindly sent mé some samples of this slag and refuse,

which Professor Desch of the Iron and Steel Institute has been good

enough to inspect for me; In a letter to the present writer he says

' I have looked at the specimens of slag which you sent me, and there

is no doubt that these are typical cinder from a bloomery process.

Part of the material shows the viscous flow structure which is quite

characteristic of bloomeries found in Europe. It represents a well

developed small scale iron industry. One lump which I will mark

separately, is a piece of iron-ore, having a very coarse oolitic structure.

According to the work on the iron ore resources of the world, oolitic

iron ores occur in some parts of Nubia. I will see whether the geo-

logical survey of Egypt gives more details. Such an ore would be

suitable for smelting in a bloomery.' Professor Desch's opinion,

therefore, entirely confirms Mr. Burton's 'ás expressed to Professor

Garstang long ago. Iron ore of the nature referred to by Professor

Desch is found freely on the surface of the Nubian sandstone which

forms large areas of the northern Sudan. Thus, it is reported that

over large areas of the Nubian sandstone a biack crust of iron ore

several inches thick lies on the surface of the rock and gives the district

I. Quoting from ¿ letter from Mr. William Burton M.A., F.C.S., Director and

Manager of , Messrs Pillçington's .Tile and Potteiy Çp.,; July, n, J9i°-

2. Garstang, Sayce and Griffith, Meroe, p. 21.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE N^PATAN AND MEROITIC AGES 2 i

a volcanic appearance. It. is liable to form small accumulations of

nodules and fragments around the hills.® There is, therefore, no question

but that Meroe was well situated as regards supplies of iron ore, and

that the refuse lying about on the site is slag from An iron-smelting

industry ¿ We can only marvel at its immense quantities.

Nor was there any lack of firing in those days. In the middle of

the sixth century B.C. a fire of palm-wood had been used to destroy

some statues at Napata4, and Nero's expedition reported that in the

vicinity of Meroe 'greener herbage begins, and a certain amount of

forest came into view and the tracks of rhinoceroses and elephants

were seen' (Pliny, Nat. Hist, vi, 29 (35) ). The forests would no

doubt have been of stmt trees (acacia), such as today cover many square

miles of the country south of Sennar. The sunt is not a large tree,

such as the forest trees of Europe nor, does it cast a thick shade, and

this no doubt would account for Pliny's expression silvarum aliquid

instead of merely silvas. Hard wood such as the sunt is considered

necessary by various negro smelters of today for the, production of

good iron.5 Besides the sunt the heglig (Balanites aegyptiaca) is

another tree in the Nile Valley which provides very good charcoal.

Strangely enough the Beja think it wrong to use it for any such

purpose. (G. W. Murray, Sons of Ishmael, p. 161.)

3. S.C, Dunn, Notes on the Mineral Deposits of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (Khartoum,

1911) p. li.

4. Reisner in J.E.A., vi, p. 253, cf. also pp. 252,263. The destruction took place

not long alt** che time of Aspelt, who is estimated to have reigned B.C. 593-568. However,

palm- wood charcoal might not perhaps give a sufficiently fierce heat for the smelting of

iron. There had been a considerable conflagration at the time the Treasury, at Napata

was destroyed (Griffith in L.A.A.A., ix, p. 118), presumably soon after the time of Aspelt.

5. The charcoal is made from various species of acacia in the district of the Black

Volta River in West Africa, H. Labouret, Les tribus du rameau Lobi , p. 67. Elsewhere

in West Afiica the Fans say that the charcoal must be specially ' strong ' and therefore

can only be procured from five special trees, G . Tessmann, Die Pan give, p. 227. In, south-

eastern Angola it has to be made of a suitable hard wood, Read in Journal of the African

Society, 1902, p. 44. The Boloki smiths make their charcoal from hard wood, J. H.

Weeks, Among Congo Cannibals , p. 88. The Shambala smiths of German East Africa

make their charcoal from the wood of members of the heath-family (Johanssen and Döring

in Zeits, für Kolonialsprachen, v, p. 144. They use a word Erikastrauch) . These, I am

told, produce a hard wood and can grow to some size. On the Uele River the Ababua

are careful to select the right wood in order to obtain a sufficiently fierce fire, Halkin and

Viaene. Lea Ababua, p. 238, as are the smelters of Unyoro, J. Roscoe, The Northern Bantu,

p. 75. In Kenya the Kikuyu use charcoal màde from the mutumaiyu tree (Olea chrysophylla)

for smelting their iron ore, but for forging their iron they use charcoal from the mutar akwa

tree {Juniperus procera ), C. W. Hóbley, Bantu Beliefs and Magic, -p. 168. Many other

instances might be quoted of care' iräken in the selection of wood for the charcoal, but

n none of them is the botanical name of the species given or the requisite virtue stated.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

22 SUDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

Sayce was present at Garstang's exca

greatly impressed by these vast quantiti

«he readèr who had not seen them his acc

But after visiting the site Arkell says in

' I entirely endorse Sayce in the Annals

pology, iv; p. 55, where he says ' Mounta

city mounds on their northern and easte

brought to light the furnaces in which the

ed into tools and weapons. Meroe, in fa

mingham of ancient Africa ; the smoke o

must have been continually going up t

northern Africa might have been suppli

iron.' Arkell also confirms Garstang's a

the slag and refuse covers the natural sur

the depth of perhaps a metre. This mean

and as will be seen there are many others

of material, for the mound is large enou

(the Lion Temple) on its top.

The iron-smelting had been going on f

the temple, for Arkell and his companio

iron slag used in the rubble filling of the

lumps in the core of at least one pyrami

Thus, if we can date the building of the

the time before which its mound of slag

fortunately we are able to do with consi

contained a number of inscriptions to wh

assigned palaeographically. Thus, inscr

' Style g ' which was in use in the third

was in full use by that time, but that wa

for inscription No. 6 gives a much earlie

. 6. Without particulars as to wtiiçh ¿he pyramid

help, for the cemetery ran from about 300 B.C. t

.Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin , xxi (Boston* 1923) p.

.7. Griffith in Garstang, bayce and Griffith, Meroe

For the period of ' Style g ' see p. 58. 'Nos. 8, 9, 10.

(Griffith in J.E~A., xv, p. .70), who, as the g^tffitp F

252-253, Griffith, Catalogne of the Demotic Úřaffiti

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAP ATAN AND MER0I7IC AGES 23

writing ' ' appears to be not earlier than the first century B.C. and

might well be later' according to Professor Griffith.8 Dr. Lamin

Macadam tells me that he would prefer to date this inscription rath

to the beginning of the period than to the latter part, i.e. he woul

put it to the first century B.C., about the time of Petronius ' invasi

(B.C. 23) or before. Hence the temple was already in use at som

time as early as the first century B.C. Inscribed stelae ¿re not set u

in a temple until its building is àt least some way advanced, so w

shall not err on the early side if we suppose the Lion Temple to ha

been founded not later than the middle of the first century B.C. Hence,

as the temple was founded on the top of this slag-covered mound an

slag was found in the interior of its walls, the iron smelting industr

must have been established there some long time before that.

That all this accumulation belongs to the Meroitjc age is furthe

guaranteed by the presence of the broken objects of faience which a

scattered all through the layer. Arkell takes the evidence of the pure

Meroitic date one step further, for he says that * there is no trace of th

continuation of iron working at Meroe after A.D. 350 - in fact ther

seems to be no sign of occupation of that site after that date (excep

at the ' Kenisa ' to the north).' These observations as to date wou

hold good for the other mounds, of which Arkell says ' There mus

be a dozen mounds of nothing but slag (each about 12 feet high) roun

the outskirts of the city site from north to south via the east - i.e. o

all sides but the river side ; one close to the Lion temple, through which

the railway cutting goes, we examined very carefully. It is solid sla

and debris from iron smelting from top to bottom. It is a lar

mound 12 feet high at least. In trial trenches at both top and botto

we found fragments of furnace wall impregnated with iron, and trac

of ostrich feather - presumably used for fanning the furnaces : als

considerable charcoal mixed up with the debris : and from the t

we collected a number of pieces of tuyères, and finally just at the en

sticking out of the top of the mound point uppermost I found one ir

arrowhead of Meroitic type. There is no doubt whatever that there

was iron smelting there on a large scale before the Lion temple was

8. Griffith in op. ' cit., p. 64. For the inscription itself see PI. xxiii.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

24 SUDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

ever built.' Thus, we arrive at the firmly esta

industry which grew to vast proportions was bein

from the beginning of the first century B.C. or

it had ceased to exist by the end of the fourth c

Meroe was by no means the only place where

of refuse were accumulated. There are others at Kerma, Kawa

(Primis Parva), Napata (Gebel Bar kal), and on the island of Argo

In each case these mounds were in connection with a Meroitic temple

Mr. Dunn adds to this that the mounds of Kerma are at the Defufah

about four miles to the southwards, and that ' many hundred tons of

this crucible refuse is deposited here, one large mound being at least

90 feet long by 20 feet high, and there are many outlying heaps.10

The presence of crucibles, which Sayce also mentions, is hardly explic-

able by reference to the iron industry, and raises the question whether

some other industry did not also contribute to the almost incredible

piles of refuse, Sayce 's mention of blue faience in so many of the

mounds, which Arkell also reports (in limited quantity) from Meroe,

indicates that the manufacture of this material was also carried on at

these sites, and faience does require the use of crucibles. Sayce also

reports the existence of mounds of burnt bones, which appear to have

been used in the manufacture of the faience. Reisner mentions in

passing that the crucibles at the Defufah sometimes had traces of copper

inside.11 This may of course be the relics of a copper melting and

casting industry, or it may be the remains of the preparation of the

colouring matter for the faience.18 The Defufah was built in, the

first years of the Twelfth Dynasty, c.2000 B.C., and the site had already

been occupied in the Sixth Dynasty, c.2550 B.C., at both of which

times any metallurgical operations that were carried on would have

concerned copper and not iron. But still this does little to detract from

the gigantic proportions of the iron works that were established up

and down the country in Meroitic days.

9. Sayce in P.S.B. A., 1911, p. 96 ; Id. in L.A.À.A., iv. p. 55. But the once wide-

spread idea that "the followers of Horus" Were iron-smiths is now known to be a fallacy.

10. S C. Dunn, Notes on the Mineral Deposits of the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan (Khartoum,

19 II) p. 56. On p. 23 he also mentions the enormous mounds of broken crucible and

slag at Kawa opposite Dongola el Ordi and at Meroe.

II« Reisner, Kerma 1, p. 36. To Sayce s statement that they were conical, Keisner

adds that they were small and had been subjected to great heat.

12. Such as was made there, Id., op. cit., p. 39.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AND MEROITIC AGES 2$

The nice iron spoon and the three iron needles set in a silver kn

oí the Ferlini Treasure13 would ha,ve been products of this intens

activity. The hoard came from Meroe from the pyramid of Qu

Amanshakhete, who according to Reisner's chronological sche

would have reigned 45-15 B.C.1* Though surprising efforts have b

made to disparage the genuineness of the find, 16 one of the traduc

Reisner, himself brings the proof of its genuineness. On his o

archaeological grounds he dates the pyramid in which it was found

the very period to which belong the Roman objects included in

Professor Beazley of Oxford kindly informs me that he sees noth

in any of the bronze buckets, cameos, or signet rings to contradi

such a date as 45-15 B.C., which, as said above, is the date whic

Réìsner assigns to the builder of the pyramid. One of the causes o

doubt was that the type of jewellery was unknown until recen

Now, however, Reisner himself again brings evidence of the genuinenes

of the hoard, for he has published jewellery of the same general ty

and has dated some of it to the first century B.C. and more of it to

first century A.D.16 Pyramid W. v. of the Western Cemetery

Meroe was that of a queen, and is dated to about 25 B.C. Amo

the objects buried with this queen was an iron bar, at least tw

pairs of iron shears, and broken iron chi sel. 18 A Besides these find

Reisner's at Meroe, Griffith has found at Faras several pieces of a simil

sort of workmanship as Ferlini's and of similar daté.17 In classifying

13. Schäfer, Möller, and Schubart, Ägyptische Goldschmiedearbeiten , p. i88, Nos. 3

319 and figs.. The whole collection is published on Pis. i in colour, xxi-xxxvi, and m

of the pieces are figured in colour in Lepsius, Denkmaeler aus Aegypten und Âethiop

v, Pl. 42.

14. Reisner in Sudan Notes and Records v, p. 190 ; J.E.A ., ix, p. 76, where he numb

her pyramid N. VI. She is the queen called Amen-Shipalta by Budge, The Egypt

Sudan i, p. 373, who numbers the pyramid 6 and tells us that it is numbered F by CaUlia

R by Hoskins and 15 by Lepsius.

15. Budge, op. cit.t i, p. 299 says that Birch thought the jewellery to be a forgery.

On pp. 295-298 he elaborately disparages the whole thing, and without giving theslightest

reason concludes with his belief that Ferlini bought his collection at Kus or some similar

place and that his narrative is a mixture of his own experiences and those of natives in

Egypt with whom he had come in cqntact. In Sudan Notes and Records , V, p. 190 Reisner

refers to Ferlini's ' fantastic story of his finds/ The unique places in which the queen

had her jewels immured have preserved them to us, whereas all that which was buried

in the usual places by other rulers has long ago been stolen.

16. Reisner in Museum of Fine Arts Bulletin (Boston, 1923) xxi, figs, on pp. 24, 25,

27. Similarly gold signet rings were found which he also put to the same period, p. 27

and figs, on p. 19.

16 A. Dows Dunham, Two Royai Ladies of Meroe p. 10 (Museum of Fine Arts

Boston: Comunication» to the Trustees« vii).

47, Gruma m xi, pp. x66*i68 and Pl. ma; xu, pp. 8o, 81 and Pl. xx.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

26 SUDAN NOTES ANĎ RECORDS

tombs by their shape and some of their contents he

from which his jewellery came falls into the A Period,

extended from the first century B.C. to the first ce

not escape notice that with these pieces of jeweller

ironwork was found just as it was with Ferlini's

was the remains of the iron binding of a casket an

In the middle or latter part of this period, that i

somewhat later tha,n the period running from Au

a man was killed at Wa,di es-Sebua with an iron arrow,

sticking in his chest.80 A? Tiberius died in A.D. 35

earliest iron arrow yet encountered, and would come

A or at the beginning of Class B of the Faras classi

set out below. A cha,nce remark concerning the co

the pyramids at Meroe gives us another fixed point

iron, arrows. In the pyramid which he numbers W

place archaeologically to the middle of the seco

Reisner found a quiver containing 73 iron arrowhe

seen shortly this proves to have been the time that

becoming common.

Thus, a number of accurately dated things ha

enquiry well into the Romano-Nubian, or as it i

called, the Meroitic period. We now proceed to the

in that period which can only be placed within les

this time it is found in considerable quantities, an

the centuries go by. Wherever Meroitic cemeter

there iron has been reported. It is not helpful mere

objects in iron which repeat themselves indefini

except for Protessor Griffith at Faras and Bate

Gammai, no one has attempted to study the sequ

18. Id. in op. cit., xii, pp.. 64, 162. For the duration of Per

19, Id. in op. cit., xi, p» 162.

20. Emery and Kirwan, The Excavations ana Smvey between

Adindan . 1929-31, p. 93 No. 229, 13. For the date which is sup

ware see p. 511. But it should be added that an imported piece l

no doubt be later than a similar piece in Europe. Also its buria

be later again.

31. Reisner in op, ctt,, fig. on p. 23, For the date see p. 26

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AND MEROlTlC AGES 27

The publications and studies of the principal excavations of Mero

cemeteries are listed in the attached footnote,82 so that they can

found without difficulty by anyone who wishes to work through the

further.

The iron objects which Griffith found at Faras are arranged in

the following table according to class and in the periods to which the

discoverer allotted each of the graves. It is no doubt representative

of what would have been seen at the other sites had the attempt to

sequence the bigger ones been made, or had the rest been sufficiently

rich for such an attempt. Proofs of its general accuracy accumulate.

Thus, it has just been shewn that it is correct to place tomb 2782 in

Period A, and the masses of arrowheads in Period C, second to third

centuries A.D. Again, although the arrowheads had become increasing-

ly common in the latter part of the Meroitic Age, they cease suddenly

in the succeeding one, Period D, that of the Nuba-Blemmyes, other-

wise called the X-Group people. It seems strange, but is amply borne

out by the excavation of the great X-Group tumuli at Ballana and

Qustul.23 Then again the general aspect of the following table of iron

objects proclaims the general accuracy of the sequencing of the graves.

It is independent of the original arrangement, for iron was not taken

into consideration in planning the sequence.24 The table shews that

iron increases as time goes on, which is what would be expected.

Moreover, this increase is gradual and steady in all the classes of objects,

and there is no sudden unaccountable peak of frequency nor any in-

explicable gaps. That the original sequencing of the graves gives

consistent results in one of the details is satisfactory proof of its accuracy.

Thus, we can approach a study of the table with the fullest confidence.

22. MacI ver and Woolley, Areika, pp. 23-42 ; Woolley and Maclver, K arano g ;

Gar3tang, Meroe, pp. 29-47 '> Reisner, Kerma ii, ch. v ; Griffith in L.A.A.A. , xi, pp. 119-

125, 141-180, xii, pp. 57-172 ; Junker, Ermenne, pp. 77-125 ; Bates and Dunham Ex-

cavations at Gammat pubd in Harvard African Studies viii, pp. 19-28, 34-68 ; Firth, The

Archaeological Survey of Nubia, 1910-11, pp. 29-31 ; Emery and Kirwan, The Excavations

and Survey between Wadi es-Sebua and Adindan, 1929-1931, pp. 21-25, 70-102, 152-168,

206-208, 210-211, 417-450, 488-493, 509-514.

23. See footnote 41 on p. 33 infra.

24. It was based primarily upon the gradual change in tomb design checked by

observation of some of the larger classes of objects contained in the tombs, L.A.A.A., xi#

PP' T44. Mi.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

28 SUDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

Table of Iron Found at Faras26

Objects Class A Class ClàssB Class Class C r2

ist cent AB I-II cents BC II-III cents A.D. S O Ř

B.C.- ist A.D. H

A.D.

Kohl-sticks .... 474.586A 868 151.786 1092, a, 136. 142. 1007 19

894 998 early.

2057.2065 1052.1509B.1513

23302333 1519

Tweezers .... 596.691, 2888.2952 106.2633 7

2491A.

Shears .... .... 923?.ino 955, 972.2718 1019.1206 8

2383

Finger-rings .... 536 868 494B.2001 919.2830 8

2054?. 2073

Iron blades .... 2383 868> <«326.2663 291 71.96.166. 1019 224 11

and knives 2952

Cateket-fittings, r 2782 795.2596 1092, a. 661ate.345 10

Key, etc. 2952 1043. 1217.2648

Rings

Arrow-heads .... 697.2838 29J. 309.353 71.72.82.90.9^. 27

400.2095 104. 106. 140.374?

598. 1008. 1035 A

1043B.1044.1129

1206.1509C.2551?

2648.2984

JPiecesand 829A. 937A 2342.2820 2746 66 latë.90.i054 14

Fragments 2800 2376 2859.2888 1502.2934

Rods

Spatula .... 639 i

Chisel-like 923, 1

Implement

Axe-head .... 2733 , 1

Mattock? .... 2016 i

Forceps .... 955 1

Plate

Hôpks

Tongs

Saucer or Shield 1087 1

boss

Leather-cutters? 1035 A. 1037 2

Sword .... .... 1 129 i

Spearhead? .... 2741 1

Anklet

Instruments hung 2984 1

on bronze ring

Varions .... 224 1

Totals

2 5. Abstracte

Far the dating

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAtf AND MEROITIC ApES 2 9

To this table it may be added that at Sanam Griffith found fiv

graves belonging to Period A. They produced a bronze plate wit

an iron rivet, and a thin iron plate ox blade,®8 each of which would take

its place comfortably at Faras.

In the Faras table we find that throughout the Meroitic Age iron

was steadily becoming more common, though it was still only being

used for very small things ; in fact largely for toilet implements an

fittings to caskets. It is important to note that although so compar

tively common the iron arrowheads do not appear at all in the Class

Period or in the transitional period between Classes A and B.27 But

once they do begin, which is in the Class B Period, they steadily increase

until in the Class C Period they are often found in great numbers, th

suddenly, as has just been pointed out, they cease. The C Period run

approximately from about A.D. 150-250 and so includes the dat

(middle of the second century) to which Reisner assigns the pyram

at Meroe where he found the quiverful of 73 arrows with iron points.48

Elsewhere, at Gammai, Bates and Dunham counted a group of 72 from

a burial which belongs to the end of the Meroitic period.29 At Karano

Woolley and Maclver counted groups of 12, 16, 23, 42 and 48 arrowhea

respectively,30 while at Faras Griffith records one group of 14 gtn

another of 25, and on other occasions speaks if ' many,' ' a number of

' a mass of ' arrowheads.81

26. L.A.A.A., xiii, pp. 19,20, Nos. 618, 1203.

27. On pp. 7, 8, 9 it was seen that of some 1550 graves of the Ethiopian period two

produced a single arrowhead each. As these are among the few things that came from

before Amtalqa's reign, c.568-553 B.C., they are among the earliest specimens of iron yet

found in Ethiopia. They were of the non-barbed type, which is not the usual one" in

Meroitic days.

28. See p. 26 supra.

29. Bates and Dunham, Excavations at Gammai , p. 95. The type óf the grave was

E i; i.e., the beginning of the last age which runs on to about A.D. 600. It would, however

be of the earliest possible period of this age, for it also contained an amphora with a Meroitic

inscription, p. 96. It would, therefore, not have been much after A.D. 350, and probably

before that date. For the statement that the E graves are late see pp. 115, 116.

30. Karanog, p. 243 Nos. G. 324, 259, 141, 254 ; p. 244, No. G. 294, 271.

31. L.A.A.A., xii, pp. 88-171, Nos. 49, 71, 697, 2095, 2551, 2838, 2984. It is well

to draw attention to the curious fact that these masses of iron arrow heads were commonly

accompanied by a single one in bronze ! Why ? Griffith can only suggest some magical

purpose, xi, p. 166. Emery and Kirwan, The Excavations and Survey between Wadi es-

Sebua and A dindan 1929^31, pp. 146, 422, similarly report a number of iron arrowheads

accompanied by a single bronze one.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

30 SUDAN NOTES AND RECORDS

Large as these collections of iron arrowheads w

and steady as was the increase in the use of iron

necessary to keep a proper perspective. It then be

very slight the use of iron still was, at any rate am

Out of 783 recorded graves at Kara nog only 68 co

at all,»* that is to say only 8.7% . At Faras the propo

double, for out of some 613 recorded graves 107 cont

i.e. 17%. But even 17% is still only a small proportio

it should be remembered that the things made of th

very small and light. It is, however, of considera

iron was becoming sufficiently common and chea

to be made of it, for arrows are things that are lost

when once shot away in war.88 The survey of the or

shews that, whoever it may have been, it was not t

that was providing occupation for the great iron in

existence of which we have such ample evidence. It

noting that in the following table of the iron at Gam

portion of the objects come from the comparativ

These are thought, no doubt rightly, to belong to t

It must, however, be remarked that most of those f

iron came belong to the E type, which seems to be t

series (p.in).

Faras seems to come to an end by or before the faU o

kingdom, which took place about 350 A.D. But the

which has been sequence dated, Gammai, runs through

ing period, called the X-Group, which gives evidenc

3 2. The last grave is recorded on p. 236, and the finds of iron h

from the records on pp. 243, 244.

33. An arrowhead sticking in the body of the dead man has alr

p 26 Woolley and Macl ver, Karanog, pp. 217, 237, quote two mor

these the arrowhead was embedded for half its length in one of th

young man having been shot from behind between the shoulders.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AND MEROITIC AGES 3 1

until about A.D. 6oo.#4 It is reported to have been a poor and bac

ward place,35 which perhaps accounts for the fact that iron does

shew much sign of increasing even in its later ages. Bates and Dun

are able to arrange their tombs into types of which the order is

C,B,E,.86

34. Bates and Dun

35. id., loc. cit.

36. Id. op. cit., p. m.

Table of Iron Found at Gammai.

Type Tomb Iron Objects Page

A ii ? T. 14 3 arrowheads 65

Cii 116 nails 43

Cii 147 kohl-stick 48 •

C iv 115 ! chain attaching cover to a bronze askos 41 No. 11

42 Nos. 16

a-b

Bi in j fittings to toilet box 37» 38

B i 132 ¡ nails and traces of other objects 47

B i? E. 64 tool, ornament of sheet iron, finger-ring 59»6o

B? Mound J clappers to bronze bells 84

E i E. 14 anklet, finger-rings, many fragments 55

E i E. 115 2 anklets, finger-rings, fragments 63

E i E. 146 j knife 64

E i ! Mound Z | dagger, hatchet, m

! ments, 72 arrowheads, nai

E ii C. 6 arrow-heads 54

Eii E. 85 coiled ring 61

E iii j E. 50 finger-ring 58

E iii i Mound T bracelet 86

E iv ; E. 17 ! io fragments 56

Eiv i E. Í30 j sword 64

E iv? j E 40 i knife or sword 57

Inter-

between ' Mcund B 1 arrows, fragment j 71

E i & iv j

E Mound U j rod, spike, fragments 87

K Mound Y i horse- bit, clappers to bronze bells, 2 arrowheads 89,91

E? Mcund E ' nails, mace-head, bodkin, fittings to casket, bar, 75,76,79,80

rings, hooks, etc., many lanceheads, fragments 81,82

Unclass- ! j '

if ied ; Ei ' mattock, shoe to staff or spear 54

i

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

32 SUSAN NOTES AND RECORDS

A certain number of the tombs listed here are capa

archaeological sequencing. Thus, Types A and C a

Meroitic date, for the well-known painted pottery wa

Similarly tomb 115 is also Meroitic, for it contain

incised with regular Meroitic scenes and a Meroit

also contained bronzes of classical workmanship like

late Meroitic cemetery at Begarawiyeh (Meroe) (p

Again Mound Z produced an amphora with a Mero

and, as it appears to be neither very early or very lat

the cemetery, it is probably of about the third ce

such a date agrees the mass of 72 iron arrowheads

Reisner's similar quiverful of 73 has already beeii da

middle of the second century A.D. Mound T on the o

be later, for a piece of a broken inscription in the latest

writing was found in the earth composing the mo

possibly it is not much later, as like Mounď Z it did

very late. On the other hand Mound Y contained the

the excavations at Ballana and Qustul have shewn to

of the X-Group age. Bates and Dunham are, therefore,

diagnosis of the mound as late. Hence, having been r

they are probably also correct in considering Mound

be late also (p. 112). Although Mound J is said to

of being early (p. 112), actually it is probably lete

cavators themselves type it as B?. Moreover, bells

horse-burial in it, and while they do not occur at eit

Karanog, they are common in the X-Group graves

graves there was only one, Mound Y, which definitely pr

as of X-Group date. Thus, at this poor and backward

the use of iron continued on just into the X-Group a

it had been throughout the Meroitic age at more pro

37. Reisner found three bells at Meroe and dated them to the m

century A.D., see p. 26 supra , They did not, however, belong t

attached to a quiver.

This content downloaded from

88.246.199.217 on Sun, 19 May 2024 19:23:44 +00:00

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

IRON IN THE NAPATAN AHD MEROITIC AGES 33

At Ballana and Qustul, just north of Wadi Haifa and the Second

Cataract, a cemetery of great tumuli has been discovered. These

tumuli prove to have been made for the kings of the X-Group people.»8

This period fills the gap between the fall of Meroe or possibly rather

earlier and the coming of the Christian age,3» i.e. it runs from about

A.D. 250 at the earliest to about A.D. 600. In these great' tumuli

iron is the normal metal of everyday use, and the objects made of

it are no longer merely small, light, things as hitherto. We get great

heavy spears and swords (pp. 219-232), knives, hóeblades, saws, axes,

adzes, hammers, pincers, metal-cutters, chisels (ppi 327-337), a cooking

tripod (p. 382) and a sifting-pan, all of iron. The bits of the horses'

bridles are of iron, if they are not of silver (pp. 254-6), and, móst astonish-

ing of. all, even folding camp-stools were used and they also were made

of iron (pp. 359-361). Iron is now so common that even the tenon

fastening the silver crest to one of the silver crowns is of that metal

(p. 183). In keeping with its utilitarian use the employment of iron

tor making toilet implements and personal ornaments has now been

reduced to such a minimum as almost to have ceased. Most remark-

able of all were the hoards of iron ingots, 31 of which came from one of

the tombs and 5 from another.40 Here, then, the people were in the

full Iron Age at last.41 The X-Group people of the tumuli at the

smaller cemetery of Firka were similarly in the full Iron Age.42

38. Emery and Kirwan, The Royal Tombs of Ballana and Qustul, p. 18.

39. For all this and studies of the period see Emery and Kirwan, op. cit, pp. 18-24,

399; Kirwan, The Oxford Excavations at Firka, pp. 40, 41 ; Reisner, The Archaeological

Survey of Nubia 1907-08, pp. 345-346 ; Firth The Archaeological Survey of Nubia 1908-09,

PP- 35"38' 88-98 : Id., op. cit. 1910-11, pp. 31-33, 118-124 and figs 4, 5, pp. 156-164.

40. Emery and Kirwan, op. c%t. p. 128 No. 77, p. 338 and PI. 83, fig. E ; pp. 137, 337.

They averaged 34 and 38 cms in length respectively, and tapered to the ends. Judging

trom the photograph they seem to measure about 5 to 5 i cms at the widest part. Another

one was found at Gammai. It was 39 cms long and of square section measuring 4x4 cms