Week 12

Uploaded by

Luba SimoniaWeek 12

Uploaded by

Luba SimoniaTheoretical Course of English Grammar

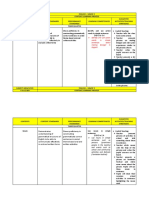

Types of connection of clauses in a composite sentence

Clauses in a composite sentence may be linked in the following ways:

a) syndetically, i.e. by means of coordinating and subordinating conjunctions

and connective words such as adverbs and pronouns (“It was very cold, and

the children stayed at home.” “I know where he lives.” “I know what he

said.”).

When more than two clauses are linked by ‘and’ or ‘or’, it is usual to

insert the coordinator only once – between the last two units (“The wind

roared, the lightning flashed, and the clouds raced across the sky.”). In po-

lysyndetic coordination, however, the coordinator is repeated between

each clause (“The wind roared, and the lightning flashed, and the clouds

raced across the sky.”).

The conjunctions and, or and that are not members of the sentences.

The connective words where, when, which are parts of the subordinate

clauses: where is an adverbial modifier of place, when is an adverbial mod-

ifier of time, what is an object, etc.

“I know where he lives.” “I know when he will arrive.”

“I know what he said.”

b) asyndetically, i.e. without a conjunction or a connective word. In writing,

asyndetical coordination is always marked by a comma, a semicolon, or a

colon, while asyndetical subordination is not marked. When speaking,

clauses are joined within the sentence by means of intonation.

c) with some clauses the inverted word order serves as a means of subordina-

tion and is equivalent to a conjunction. For instance, “Had she been near

him, she would have told him everything.” – is a complex sentence in

which an adverbial clause of condition is marked by inversion (“Had she

been near him… = “If she had been near him…”). Or another sentence: “I

wonder who he is.” – in which an object subordinate clause - “who he is”,

is marked by inversion.

Script by prof. Nino Kirvalidze 75

Theoretical Course of English Grammar

Functional-semantic types of subordinate clauses

Subordinate clauses may function as subject, subject complement (i.e. predicative clause),

object, relative (i.e. attributes clauses) and adverbial clauses of the complex sentence. On the

basis of their potential functions, grammarians (Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech, Tallerman and

others) distinguish four major categories of subordinate clauses: nominal, relative (i.e. attribu-

tive), adverbial and comparative.

Survey of the nominal subordinate clauses

Like noun phrases, nominal clauses may function as subject, subject complement (predica-

tive), object and its complements (i.e. indirect and prepositional objects). But the occurrence of

nominal clauses is more limited than that of noun phrases, because semantically the clauses are

normally abstract; i.e. they refer to such abstractions as events, facts, and ideas.

Complex sentences with subject subordinate clauses. There are two types of complex sen-

tences with subject clauses in English:

1. The subject subordinate clause precedes the main clause which is incomplete,

the clause functioning as the subject of the complex sentence:

That Chris liked Lee so much didn’t surprise me.

That we need a larger computer is obvious.

Whether she likes the present is not clear to me.

2. The subject clause follows the main clause which begins with anticipatory it :

It was evident that he did not understand anything.

It is a miracle how he managed to escape the danger.

In modern English, due to the fixed word order, the subject cannot follow the

predicate unless some formal element is used to fill in the place of the subject.

Therefore, it and the subject clause are correlated to form a compound subject of

Script by prof. Nino Kirvalidze 76

Theoretical Course of English Grammar

the main clause in which the anticipatory it constitutes its formal part, the sub-

ject clause representing its lexical part.

Complex sentences with predicative clauses. Predicative clause performs the function of the

nominal part of the predicate, following the link verb, the so-called ‘copula’. The link-verb is

mostly expressed by the pure copula be, as well as by the specifying links seem and look. The

use of other specifying links is occasional. The predicative clause, like other nominal clauses,

can be introduced by the conjunctions: that, whether, as if, as though. For example:

“The trouble is that I don’t know him at all.”

“She looks as though she has never met him.”

Complex sentences with object clauses. Object clauses perform the function of an object

denoting a situation of the process expressed by the verbal predicate of the main clause. Object

clauses may be non-prepositional and prepositional:

“I noticed that he spoke English well enough.”

“I’m sorry for what I said to you yesterday.”

The preposition connected with a conjunctive pronoun in an object clause may occur at the end

of the subordinate clause. Such a proposition is called detached or end-preposition. For

example: “I don’t understand what they are talking about.”

“I wonder what you are looking at.”

Types of relative (attributive) clauses

Relative clauses represent a type of subordinate clause which modifies a head noun. They

are embedded within the main clause by means of relative pronouns (who, whom, whose,

which) or relative adverbs (when, where, how, why), as well as by the subordinating conjunc-

tion that. They are classified into four main types: a) restrictive, b) descriptive, i.e. non-

restrictive, c) continuative, and d) appositive.

The restrictive relative clause performs a purely identifying function, singling out the re-

ferent of the antecedent which is always preceded by the definite article the. In other words,

Script by prof. Nino Kirvalidze 77

Theoretical Course of English Grammar

this type of relative clauses restricts the possible set of the class of things just to the subset that

the speaker wants to talk about. For example: I met the students who had not read the book

(the head noun is in bold type, the relative clause is underlined). In this sentence the speaker

implies that he didn’t just meet the students, he met a specific subset of students – only those

ones who hadn’t read the book.

The descriptive relative clause exposes some characteristic of the antecedent as such. It

should be noted, that the antecedent in descriptive relative clauses is always preceded by the

indefinite article a/an. For instance, in the complex sentence - “At last we found a place where

we could make a fire.”- the relative clause is descriptive.

The continuative relative clause gives some additional information about the antecedent,

thus developing the chain of situations denoted by the sentence as a whole. Since the antece-

dent in the continuative relative clause is usually represented by a proper name which refers to

a concrete individual, it can be left out without destroying the meaning of the sentence. This

can be tested easily if we replace relative subordinator by the coordinative conjunction and +

personal pronoun. Cf.: “I phoned to Mr. Smith, who recognized me at once and invited me to

his office.” “I phoned to Mr. Smith, and he recognized me at once and invited me to his

office.”

The appositive relative clause refers to a substantive antecedent of abstract semantics, de-

fining or clarifying its concrete meaning in the context. Therefore, appositive clauses are nearer

to restrictive clauses than the rest of relative clauses. According to the type of the antecedent

(i.e. head noun), all the appositive clauses fall into three groups:

a. appositive clauses which modify abstract nouns like fact, idea, question, suggestion,

news, information, etc. Cf.:

“The news that John had married Helen made a stir among their friends.”

“The fact that he has lost all his money is a great shock for him.”

b. appositive clauses which modify abstract names of adverbial relations, such as time,

moment, place, condition, purpose, etc. which are usually preceded by the definite ar-

ticle the:

“We saw him at the moment (when) he was opening the door.”

Script by prof. Nino Kirvalidze 78

Theoretical Course of English Grammar

“I remember the time (when) we went to school together.”

“They did it with the purpose that no one might escape the punishment.”

c. appositive clauses which define the meaning of the antecedent represented by indefi-

nite or demonstrative pronouns:

“I can’t agree with all what you are telling me.”

“Everything what you see in this room is your.”

Functional-semantic types of English adverbial clauses

Adverbial clauses refer to a verb, an adjective or an adverb of the main clause. They are

usually joined to the main clause by means of subordinating conjunctions. When an adverbial

clause precedes the main clause it is set off with a comma.

Adverbial clauses constitute a vast domain (sphere) of syntax which falls into many subdi-

visions according to their functional-semantic peculiarities. Speaking of the semantics of

adverbial clauses, we should remember that we are concerned with generalized grammatical

meanings which are of syntactic relevance. Therefore, the classification of adverbial clauses

into subtypes is mainly based on their functional meanings, according to which the whole

system of adverbial clauses is divided into four groups:

1. The first group of adverbial clauses includes clauses of time and of place;

2. The second group of adverbial clauses comprises clauses of manner and compari-

son;

3. The third group of adverbial clauses includes clauses of attendant circumstances

(თანმხლები გარემოება), condition, cause, purpose, reason, result, concession

(დათმობითობა);

4. The fourth group of adverbial clauses is formed by parenthetical or insertive claus-

es.

The first group includes clauses of time and of place. Their common semantic basis can be

defined as “localization” – respectively, temporal (answering the question when), and spatial

(answering the question where).

Script by prof. Nino Kirvalidze 79

Theoretical Course of English Grammar

Adverbial clauses of time are introduced by the subordinating conjunctions when, as,

since, before, after, until, as soon as, now that, etc. For example:

“We lived in London when the war ended.”

“We had lived in London all through the war until it ended.”

“After the war ended our family moved to Glasgow.”

Adverbial clauses of place are introduced by the subordinating conjunction where, which

can be sometimes preceded by the prepositions from and to: from where(bookish equivalent –

whence) and to where:

“The swimmers gathered where the beach formed a small mound.”

“We decided to go back from where we had started on our journey.”

The second group comprises adverbial clauses of manner and comparison. The common

semantic basis of their functions can be defined as “qualification”, since both of them modify

the action or event denoted by the main clause. The identification of these adverbial clauses can

be achieved by applying the question-transformation of the how -type.

Adverbial clauses of manner are introduced by the subordinating conjunctions: as, as if, as

though:

“He spent the evening as he had been told.” (How did he spend the evening?)

“You talk to him as if he were your Boss.” (How do you talk to him?)

Adverbial clauses of comparison are introduced by the subordinating conjunctions: as …

as, not so … as, than. Cf.:

“That summer he took a longer holiday than he had done before.”

“Mary received the guests as nicely as her mother would have done.”

“It is not so hot today as it was yesterday.”

The third and most numerous group of adverbial clauses includes clauses of different se-

mantics connected with the meaning of the main clause by various circumstantial associations.

Accordingly, this group comprises clauses of attendant circumstances, condition, cause (reason),

purpose, result and concession.

Adverbial clauses of attendant circumstances (თანმხლები გარემოება) by their semantics

are very close to clauses of time. The difference lies in the fact that, unlike clauses of time, the

Script by prof. Nino Kirvalidze 80

You might also like

- Why Do You Want To Work in U.K?Job Interview Questionnaire88% (8)Why Do You Want To Work in U.K?Job Interview Questionnaire7 pages

- 7 - M17 - S3, Grammar3, The Remaining Lectures, Weeks 7+8+9+10, Pr. ElmouhtarimNo ratings yet7 - M17 - S3, Grammar3, The Remaining Lectures, Weeks 7+8+9+10, Pr. Elmouhtarim18 pages

- Dependent and Independent Clauses-Nana TatarashviliNo ratings yetDependent and Independent Clauses-Nana Tatarashvili9 pages

- Subordinate Clause (Also Called Dependent Clauses)No ratings yetSubordinate Clause (Also Called Dependent Clauses)4 pages

- Complex Sentence Subject, Predicative, Objective, Attributive ClauseNo ratings yetComplex Sentence Subject, Predicative, Objective, Attributive Clause12 pages

- Adjective Clause Definition:: Which, Who, Whom, Whose) That Connects The Clause To The Noun or Pronoun It ModifiesNo ratings yetAdjective Clause Definition:: Which, Who, Whom, Whose) That Connects The Clause To The Noun or Pronoun It Modifies6 pages

- The Complex Sentence: (Cronin) (CONNECTIVE)No ratings yetThe Complex Sentence: (Cronin) (CONNECTIVE)15 pages

- Clauses:: A Clause Is A Part of A Sentence, A String of Words Which Expresses ANo ratings yetClauses:: A Clause Is A Part of A Sentence, A String of Words Which Expresses A15 pages

- Estudos Avançados de Língua Inglesa - Estudos Gramaticais: Aula 6No ratings yetEstudos Avançados de Língua Inglesa - Estudos Gramaticais: Aula 615 pages

- Writing Fifty - Essential.Strategies - Quick.List PDFNo ratings yetWriting Fifty - Essential.Strategies - Quick.List PDF4 pages

- English Grammar - Master in 30 Days (Not Printed)100% (5)English Grammar - Master in 30 Days (Not Printed)181 pages

- English For Everyone English Vocab - Bak-Compressed100% (8)English For Everyone English Vocab - Bak-Compressed362 pages

- Exame de Equivalência À Frequência de InglêsNo ratings yetExame de Equivalência À Frequência de Inglês4 pages

- Identify and Use Action Words in Simple Sentences About Making Binagol in DagamiNo ratings yetIdentify and Use Action Words in Simple Sentences About Making Binagol in Dagami2 pages

- Pause Phenomena in Spontaneous English Speech by The Teachers ofNo ratings yetPause Phenomena in Spontaneous English Speech by The Teachers of6 pages

- The Doctor Visited Her Patients in The Hospital.: Complete SubjectNo ratings yetThe Doctor Visited Her Patients in The Hospital.: Complete Subject4 pages

- 22pam0062 Intermediate Academic English Part5No ratings yet22pam0062 Intermediate Academic English Part520 pages

- EF-4 Upper-Intermediate Relative-Clauses Adults-5 STNo ratings yetEF-4 Upper-Intermediate Relative-Clauses Adults-5 ST3 pages

- 1 - M34 - S6P2, Semantics and Pragmatics, Introductory Course, Pr. Zanzoun & Pr. KoubaliNo ratings yet1 - M34 - S6P2, Semantics and Pragmatics, Introductory Course, Pr. Zanzoun & Pr. Koubali62 pages

- Why Do You Want To Work in U.K?Job Interview QuestionnaireWhy Do You Want To Work in U.K?Job Interview Questionnaire

- 7 - M17 - S3, Grammar3, The Remaining Lectures, Weeks 7+8+9+10, Pr. Elmouhtarim7 - M17 - S3, Grammar3, The Remaining Lectures, Weeks 7+8+9+10, Pr. Elmouhtarim

- Dependent and Independent Clauses-Nana TatarashviliDependent and Independent Clauses-Nana Tatarashvili

- Subordinate Clause (Also Called Dependent Clauses)Subordinate Clause (Also Called Dependent Clauses)

- Complex Sentence Subject, Predicative, Objective, Attributive ClauseComplex Sentence Subject, Predicative, Objective, Attributive Clause

- Adjective Clause Definition:: Which, Who, Whom, Whose) That Connects The Clause To The Noun or Pronoun It ModifiesAdjective Clause Definition:: Which, Who, Whom, Whose) That Connects The Clause To The Noun or Pronoun It Modifies

- Clauses:: A Clause Is A Part of A Sentence, A String of Words Which Expresses AClauses:: A Clause Is A Part of A Sentence, A String of Words Which Expresses A

- Estudos Avançados de Língua Inglesa - Estudos Gramaticais: Aula 6Estudos Avançados de Língua Inglesa - Estudos Gramaticais: Aula 6

- A Short New Testament Syntax: Handbook with ExercisesFrom EverandA Short New Testament Syntax: Handbook with Exercises

- English for Academic Correspondence and SocializingFrom EverandEnglish for Academic Correspondence and Socializing

- Writing Fifty - Essential.Strategies - Quick.List PDFWriting Fifty - Essential.Strategies - Quick.List PDF

- English For Everyone English Vocab - Bak-CompressedEnglish For Everyone English Vocab - Bak-Compressed

- Identify and Use Action Words in Simple Sentences About Making Binagol in DagamiIdentify and Use Action Words in Simple Sentences About Making Binagol in Dagami

- Pause Phenomena in Spontaneous English Speech by The Teachers ofPause Phenomena in Spontaneous English Speech by The Teachers of

- The Doctor Visited Her Patients in The Hospital.: Complete SubjectThe Doctor Visited Her Patients in The Hospital.: Complete Subject

- EF-4 Upper-Intermediate Relative-Clauses Adults-5 STEF-4 Upper-Intermediate Relative-Clauses Adults-5 ST

- 1 - M34 - S6P2, Semantics and Pragmatics, Introductory Course, Pr. Zanzoun & Pr. Koubali1 - M34 - S6P2, Semantics and Pragmatics, Introductory Course, Pr. Zanzoun & Pr. Koubali