HECHO Positive Actionj

HECHO Positive Actionj

Uploaded by

palomaCopyright:

Available Formats

HECHO Positive Actionj

HECHO Positive Actionj

Uploaded by

palomaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

HECHO Positive Actionj

HECHO Positive Actionj

Uploaded by

palomaCopyright:

Available Formats

ARTICLE

Effects of 2 Prevention Programs on High-Risk

Behaviors Among African American Youth

A Randomized Trial

Brian R. Flay, DPhil; Sally Graumlich, EdD; Eisuke Segawa, PhD; James L. Burns, MS;

Michelle Y. Holliday, PhD; for the Aban Aya Investigators

Objective: To test the efficacy of 2 programs designed lence, provocative behavior, school delinquency, sub-

to reduce high-risk behaviors among inner-city African stance use, and sexual behaviors (intercourse and con-

American youth. dom use).

Design: Cluster randomized trial. Results: For boys, the SDC and SCI significantly re-

duced the rate of increase in violent behavior (by 35%

Setting: Twelve metropolitan Chicago, Ill, schools and and 47% compared with HEC, respectively), provoking

the communities they serve, 1994 through 1998. behavior (41% and 59%), school delinquency (31% and

66%), drug use (32% and 34%), and recent sexual inter-

Participants: Students in grades 5 through 8 and their course (44% and 65%), and improved the rate of in-

parents and teachers. crease in condom use (95% and 165%). The SCI was sig-

nificantly more effective than the SDC for a combined

Interventions: The social development curriculum behavioral measure (79% improvement vs 51%). There

(SDC) consisted of 16 to 21 lessons per year focusing on were no significant effects for girls.

social competence skills necessary to manage situations

in which high-risk behaviors occur. The school/ Conclusions: Theoretically derived social-emotional pro-

community intervention (SCI) consisted of SDC and grams that are culturally sensitive, developmentally ap-

school-wide climate and parent and community compo- propriate, and offered in multiple grades can reduce mul-

nents. The control group received an attention-placebo tiple risk behaviors for inner-city African American boys

health enhancement curriculum (HEC) of equal inten- in grades 5 through 8. The lack of effects for girls de-

sity to the SDC focusing on nutrition, physical activity, serves further research.

and general health care.

Main Outcome Measures: Student self-reports of vio- Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:377-384

V

IOLENCE, SUBSTANCE USE, lence, substance use, delinquency, and

and unsafe sexual prac- risky sexual activity reflect an underly-

tices are major public ing “problem behavior” construct,13-15 and

health problems challeng- empirical evidence increasingly supports

ing today’s urban African this premise,16,17 regardless of ethnicity or

American youth.1,2 Urban African Ameri- race. Given the strong correlations among

can youth are at high risk for violence ow- these behaviors and their predictors, pre-

ing to exposure to violence in their com- vention efforts may best be served by ad-

munities.3-6 They also experience more dressing multiple behaviors concur-

exposure, easy access, and daily pressure rently.13,18,19 Only a handful of interventions

to use or traffic illicit drugs.7-9 Compared aimed at multiple behaviors have been

with white youth, African Americans are tested,20-23 and most have not used ran-

more likely to report earlier initiation of domized designs. The current study was

sex, higher lifetime rates of sexual inter- designed to overcome this methodologi-

From the Health Research and

course, and more sexual partners in their cal limitation and to meet recommenda-

Policy Centers, University of lifetimes, with resulting high rates of preg- tions for effective prevention programs.24

Illinois at Chicago. A complete nancy and human immunodeficiency vi- The Aban Aya Youth Project—

list of the Aban Aya rus infection.10-12 which derives its name from 2 Ghanian

investigators appears on Investigators have theorized that the symbols, aban, a fence signifying double

page 383. seemingly separate behaviors of vio- (social) protection, and aya, an unfurl-

(REPRINTED) ARCH PEDIATR ADOLESC MED/ VOL 158, APR 2004 WWW.ARCHPEDIATRICS.COM

377

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

ing fern signifying self-determination—compared 3 in- INTERVENTIONS

terventions that were implemented in grades 5 through

8. Two experimental interventions (one a classroom- The conceptual framework of the experimental interventions was

based curriculum and one that also included school and derived from established theories of behavior change14 to focus

community-wide components) targeted the risk behav- the interventions on risk and protective factors and skills re-

lated to the targeted behaviors. Activities and materials were either

iors of violence, provoking behavior, substance use, school developed de novo or adapted from other theoretically derived

delinquency, and sexual practices (engaging in sexual in- prevention curricula (eg, New Haven Social Development Pro-

tercourse and using condoms). The control program tar- gram,26 Youth AIDS Prevention Project,27 and Know Your Body28).

geted health-enhancing behaviors (nutrition, exercise, and New or adapted activities were piloted before being added to the

health care) and was of equal length and intensity. We curricula, and each grade-level curriculum was piloted the year

hypothesized that both experimental conditions would before its use in the main study. As a result of piloting, minor

result in reductions in the rate of increase of targeted be- changes were made to improve flow or language.

haviors compared with the control condition. Studies suggest that programs for African American youth

should incorporate components that (1) enhance growth of sense

of self and cultural pride and (2) strengthen family and com-

METHODS munity ties.29,30 Hence, the interventions included the Nguzo

Saba principles,31 which promote African American cultural val-

SCHOOL SELECTION AND RANDOMIZATION ues such as unity, self-determination, and responsibility; cul-

turally based teaching methods32 (eg, storytelling and prov-

The longitudinal trial of 3 interventions was conducted in a high- erbs) and African and African American history and literature;

risk sample of 12 poor, African American metropolitan Chi- and homework assignments that involved parents to encour-

cago, Ill, schools (9 inner-city and 3 near-suburban) between 1994 age review and generalization of the information and skills and

and 1998. School inclusion criteria included enrollment of greater to expand the target of the intervention to parents.33

than 80% African American and less than 10% Latino or His- The 2 experimental conditions were the social develop-

panic students; grades kindergarten through 8 (or through 6 if ment curriculum (SDC) and the school/community interven-

students were tracked to 1 middle school); enrollment greater tion (SCI) (Table 1). The SDC was classroom based, consist-

than 500; not on probation or slated for reorganization; not a ing of 16 to 21 lessons per year in grades 5 through 8. The

special designated school (ie, magnet, academic center); and mod- SDC was designed to teach cognitive-behavioral skills to build

erate mobility (⬍50% annual turnover, meaning approxi- self-esteem and empathy, manage stress and anxiety, develop

mately ⬍25% transferred in and ⬍25% transferred out). Eli- interpersonal relationships, resist peer pressure, and develop

gible schools (n=141 inner-city and 14 near-suburban) were decision-making, problem-solving, conflict-resolution, and

stratified into 4 quartiles of risk on the basis of a score that com- goal-setting skills. It was structured to teach application of

bined proxy risk variables using the procedures described by Gra- these skills to avoid violence, provocative behavior, school

ham et al.25 The proxies of risk came from school report card delinquency, drug use, and unsafe sexual behaviors.

data (1991-1992) and included enrollment, attendance and tru- The SCI included the SDC plus parental support, school cli-

ancy, mobility, family income, and achievement scores. Using a mate, and community components to impact all social domains

randomized block design, we assigned to each condition 2 inner- of influence on children.34,35 The parent support program rein-

city schools from the middle of the highest risk quartile, 1 inner- forced skills and promoted child-parent communication. The

city school from the middle of the second risk quartile, and 1 school staff and school-wide youth support programs integrated

near-suburban school (also from the second quartile) per con- skills into the school environment. The community program forged

dition. One inner-city school refused to participate and was re- linkages among parents, schools, and local businesses. Each SCI

placed with one from the same risk level. Schools signed an agree- school formed a local school task force consisting of school per-

ment to participate in the study for 4 years and agreed not to sonnel, students, parents, community advocates, and project staff

participate in another prevention initiative during that time. Study to implement the program components,36 propose changes in

schools were 91% African American. Each school received the school policy, develop other school-community liaisons support-

intervention free of charge (provided to all students in the ap- ive of school-based efforts, and solicit community organizations

propriate grade levels) plus $250 for each participating class- to conduct activities to support the SCI efforts. A goal of these

room up to a maximum of $1000 each year of the study. linkages was to “rebuild the village” and create a “sense of own-

ership” by all stakeholders to promote sustainability of these ef-

PARTICIPANTS forts on completion of the project.37

The control condition was the health enhancement cur-

Participants were students in fifth-grade classes in the 12 schools riculum (HEC). It consisted of the same number of lessons as

during the 1994-1995 school year or who transferred in dur- the SDC and taught some of the same skills (eg, decision mak-

ing the study; students who transferred out were not followed ing and problem solving), but with a focus on promoting healthy

up, but their data from the times before they transferred out behaviors related to nutrition, physical activity, and general

were included in the analysis sample. Students who trans- health care (see Table 1). It also integrated the importance of

ferred into study schools were similar to students who trans- cultural pride and communalism.

ferred out; both groups were more likely to engage in risky be-

havior than students who stayed in the same school for the STAFF TRAINING AND IMPLEMENTATION

duration of the project (significant only for violence and sub-

stance use). Parents or legal guardians were informed of the University-based health educators delivered curricula in all 3

study and procedures and were provided with an opportunity conditions, usually in social studies classes. Each health edu-

to opt out in grades 5 through 7 and then again in grade 8. Less cator delivered 1 of the curricula to 1 or more schools and, in

than 1% of parents denied consent during grades 5 through 7 most cases, health educators stayed with the same school from

and 1.7% did so at grade 8. The University of Illinois at Chi- year to year. This avoided contamination across conditions and

cago Institutional Review Board approved the research proto- developed continuity in relationships between educators and

col and informed consent procedures. the schools and students. To ensure fidelity of implementa-

(REPRINTED) ARCH PEDIATR ADOLESC MED/ VOL 158, APR 2004 WWW.ARCHPEDIATRICS.COM

378

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Table 1. Intervention Content by Condition*

Health Enhancement Curriculum Social Development Curriculum School/Community

Target Behaviors Target Behaviors Target Behaviors

• Nutrition • Violence • Violence

• Physical activity • Provoking • Provoking

• Dental hygiene • Safe sex and abstinence • Safe sex and abstinence

• Injury prevention • Substance use • Substance use

• Mental health • School delinquency • School delinquency

Content Content Components

Skills Skills Social development curriculum

• Decision making • Anger management • See middle column

• Problem solving • Communication Teacher and staff in-service training

• Goal setting • Negotiation, conflict resolution • Review and model curriculum skills

• Refusal skills • Social networking • How to integrate prosocial skills into school

• Stress management • Decision making environment

• Health assessment: physical, mental, • Problem solving • Provide example of school activities to reinforce

and social • Goal setting curriculum skills

• Cardiovascular fitness: taking pulse and • Refusal skills • Model proactive classroom management skills

target ranges • Stress management • Promote interactive and cultural teaching methods

• Strengthening and flexibility exercises

Sense of self and purpose Sense of self and purpose Local school task force

• Feelings • Empathy • Propose school policy

• Personal strengths • Career planning • Conduct school-wide fairs

• Cultural pride • Feelings • Provide annual field trips for program parents

• Mentors • Personal strengths and children

• Communalism • Cultural pride • Write grants for local monies

• Mentors • Solicit monies and supplies from local businesses

• Communalism

Culture, values, and history Culture, values, and history Parent training workshops

• African American heritage • Influence of racism and stereotypes on self • Reinforce skills taught in social development

• Ethnic values—Nguzo Saba and community curriculum

• Normative beliefs • African American heritage • Improve child supervision and methods

• Environmental influences • Ethnic values—Nguzo Saba of discipline

• Role models • Normative beliefs • Enhance anger and stress management

• Environmental influences • Enhance parent-child communication

• Role models • Promote parent-teacher communication

*The first 2 columns show the content of the 2 curricula. Note that when the same skills were taught in the 2 curricula, the targeted behaviors always differed

by condition. The third column shows the content of the school/community condition—the social development curriculum (column 2) plus the other

components listed.

tion across health educators, experimental conditions, and times, dom use were added at grade 6. Each behavior was assessed

2 training sessions were held before each lesson. The health with multiple items. For violence, provoking behavior, and sub-

educators role-played each activity and senior staff provided stance use, scale scores were formed for each behavior by sum-

feedback. Weekly debriefings were held to discuss issues that ming multiple items. For sexual behaviors (having sexual in-

may have affected implementation. Senior staff also con- tercourse and use of condoms), single item scores were used.

ducted observations to ensure fidelity and help target training For school delinquency, a more complicated approach was nec-

needs. In addition, each year the regular classroom teachers re- essary to produce a “scale score” because of “planned missing-

ceived a 4-hour workshop to provide an overview of program ness.”42 To reduce respondent burden, starting in the spring

philosophy, curriculum content, and clarification of their sup- of fifth grade, 3 versions of the survey, each containing the core

port roles. and 2 of the modules, were randomly assigned to classrooms

(evenly distributed across the 3 interventions) at each wave of

ASSESSMENT data collection. The core unit, answered by every student, in-

cluded items assessing demographics and all of the behavioral

Constructs were derived from the theory of triadic influence14 outcomes except school delinquency. Each of the 3 modules

and program content, and included background covariates, pro- contained two thirds of the items from the measure of school

cess variables, mediating variables, and behaviors. Only stu- delinquency. The scale and change scores were computed by

dent self-reports of behaviors (violence, provoking behaviors, fitting growth curves to each item simultaneously by means of

school delinquency, substance use, and sexual behaviors) are mixed-effect models and summing them to form the intercept

reported in this article. Measures were based on instruments (baseline score) and growth (change) of delinquency. We cre-

previously used with inner-city populations.20,27,38-41 Survey ques- ated a combined behavior measure by adjusting the range of

tions were modified for grade 4 readability and cultural sensi- the variables to be the same (0-10) and reversing the direction

tivity by means of feedback from focus groups and piloting. of scoring for condom use.

The items, response categories, scale score ranges, and re-

liability coefficients of each behavioral scale at each grade are DATA COLLECTION

available from one of us (B.R.F.). Violence, school delin-

quency, and substance use were measured from grade 5 on- Students completed surveys in classrooms at the beginning and

ward; provoking behaviors, recent sexual intercourse, and con- end of grade 5 and at the end of each subsequent year. We took

(REPRINTED) ARCH PEDIATR ADOLESC MED/ VOL 158, APR 2004 WWW.ARCHPEDIATRICS.COM

379

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

(4%-9%) or opting out. An average of 20% turnover oc-

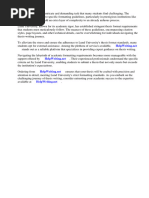

7

curred each year, resulting in an average sample of 644

6 students (range, 597-674) at each wave, with 339 (51%)

of the 668 original grade 5 students still present at the

School Delinquency (0-10)

5

end of grade 8 and a total analysis sample (students with

4 one or more waves of data) of 1153. The final sample was

49.5% male, with an average age of 10.8 years (SD, 0.6

3

year) at the beginning of grade 5; approximately 77% re-

2 ceived federally subsidized school lunches, and 47% lived

HEC Boys SDC and

HEC Girls SCI Girls in 2-parent households.

1 SDC Boys SCI Boys Table 2 shows baseline (grade 5 or grade 6), end

0

point (grade 8), and change in scale scores or propor-

5 6 7 8 tions engaging in behaviors, percentage relative reduc-

Grade tions, significance levels, and effect sizes by condition for

boys and girls. Boys engaged in higher levels of behav-

Changes in school delinquency for boys and girls by condition from the

beginning of grade 5 to the end of grade 8. Baseline intercepts shown are iors at baseline than girls for all behaviors (P⬍.001) ex-

the average of the 3 conditions for each sex. HEC indicates health cept provoking (P = .17). The prevalence of all behav-

enhancement curriculum; SDC, social development curriculum; and iors increased over time across sex and conditions. There

SCI, school/community intervention.

was one significant baseline (grade 5) difference be-

tween conditions: boys receiving the SCI engaged in more

several precautions to ensure the validity of the data. To en- violence than boys in the SDC (P=.02).

sure even completion, staff read the survey aloud to students. There were no significant program effects for girls.

To minimize underreporting of behaviors, trained project staff, Program effects for boys were significant for all 6 behav-

not the teacher or health educator assigned to that classroom, iors in the SCI and marginally so in the SDC (except for

administered the surveys. To emphasize the confidential na- condom use); boys receiving the SDC and SCI increased

ture of their answers, we assured students that results would these behaviors less (more for condom use) than boys in

not be shared with anyone and we used identification num- the HEC. The Figure shows the developmental pattern

bers rather than names to track students over time. Students of behavior change and program effects for school delin-

without consent completed teacher-assigned tasks during sur- quency. It exemplifies the nature of program effects for

vey administration.

boys, occurring gradually between grades 6 and 7.

ANALYTICAL METHODS Effect sizes for the comparison of SDC and SCI with

HEC for boys ranged from 0.29 to 0.66, and relative im-

To estimate mean responses at baseline and in response to the provements were 31% to 165%. For boys in the SDC and

program, we used hierarchical statistical models that accom- SCI, the increase in negative behaviors from fifth to eighth

modate nested observations (times within subjects, subjects grade was less than in the HEC: violence by 35% and 47%,

within schools) and missing data.43-45 For the major reported respectively; provoking behavior, 41% and 59%; school

analyses, we included all students who provided one or more delinquency, 31% and 66%; drug use, 32% and 34%; and

waves of data. recent sexual intercourse, 44% and 65%. The relative im-

We used mixed models for continuous outcomes (vio- provement in the rate of condom use was 95% and 165%.

lence, provoking behavior, school delinquency, and the com-

The effect sizes for the combined behavior score were 0.52

bined behavior) and generalized estimating equations for or-

dinal outcomes (substance use, sexual activity, and condom use). for the SDC and 0.82 for the SCI, and the relative im-

We present 2-level models throughout, as school effects proved provements were 51% and 79%.

negligible in 3-level models for continuous outcomes (and the In addition, all 6 behaviors increased less (more for

pattern of results were the same) and 3-level software for or- condom use) for boys in the SCI than for boys in the SDC.

dinal outcomes is not available. All models included terms for This difference was significant for the combined behav-

condition, sex, time (quadratic trends where necessary), and ior measure (mean difference in change, −3.35; effect size,

all interactions, except for condom use, which was estimated 0.82 vs 0.52; or 79% vs 51% relative improvement) but

separately for boys (because of low rates of sexual intercourse only for one of the individual behaviors (school delin-

for girls). Inference was based on tests of regression coeffi- quency: effect size, 0.61 for the SCI and 0.29 for the SDC;

cients and contrasts among estimated means. Contrasts were

relative reductions of 66% and 31%, respectively).

used to test baseline differences between boys and girls and be-

tween conditions (HEC, SDC, and SCI), change from baseline

to end point within condition, and differences between con- COMMENT

ditions in the amount of change, or program effects. All statis-

tical tests are 2-tailed. This randomized controlled study provides evidence

that a prevention program that teaches skills and is

RESULTS theoretically derived, developmentally appropriate, and

culturally sensitive can have concurrent effects on mul-

We first describe our sample, then baseline differences tiple risk behaviors for inner-city African American

by sex, and finally program effects. Survey completion boys in grades 5 through 8. The effect sizes for violence

rates were 93.2% of students with consent at baseline, (0.31 and 0.41) and substance use (0.42 and 0.45) are

and between 89.5% and 92.7% at the other waves. Non- substantially better than those reported in meta-analy-

completions were due primarily to school absenteeism ses for interactive school-based violence (0.16),23 drug

(REPRINTED) ARCH PEDIATR ADOLESC MED/ VOL 158, APR 2004 WWW.ARCHPEDIATRICS.COM

380

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Table 2. Baseline, End Point, and Growth of Risk Behaviors With P Values From Growth Curve Analysis by Condition and Sex

Relative Reduction, P Value, Effect Size*

Measure HEC SDC SCI SDC-HEC SCI-HEC SCI-SDC

Boys

(n = 184) (n = 204) (n = 185)

Violence (0-21)

Baseline score† 3.39 (0.29)‡ 3.17 (0.25) 4.04 (0.26) .58 .09 .01

End point score 7.63 (0.53) 5.92 (0.50) 6.28 (0.58)

Growth 4.25 (0.57) 2.75 (0.53) 2.24 (0.60) 35%, .05, 0.31 47%, .02, 0.41 19%, .52, 0.10

Provoking behavior (0-40)

Baseline score§ 8.99 (0.75)‡ 9.55 (0.69) 10.71 (0.77) .58 .11 .26

End point score 14.70 (0.90) 12.89 (0.85) 13.06 (0.97)

Growth 5.71 (1.05) 3.35 (0.98) 2.35 (1.16) 41%, .10, 0.29 59%, .03, 0.41 30%, .51, 0.12

School delinquency (0-10)

Baseline score† 3.14 (0.21)‡ 3.06 (0.18) 3.53 (0.19) .76 .17 .07

End point score 6.00 (0.33) 5.03 (0.31) 4.49 (0.37)

Growth 2.86 (0.35) 1.97 (0.33) 0.97 (0.38) 31%, .06, 0.29 66%, ⬍.001, 0.61 51%, .04, 0.32

Substance use

Baseline proportion† 0.31 (0.23-0.41)㛳 0.30 (0.24-0.38) 0.32 (0.25-0.41) .87 .91 .77

End point proportion 0.83 (0.75-0.89) 0.69 (0.59-0.77) 0.69 (0.57-0.79)

Growth 0.52 0.38 0.37 32%, .05, 0.42 34%, .05, 0.45 4%, .89, 0.03

Recent sexual intercourse

Baseline proportion§ 0.16 (0.11-0.25)¶ 0.29 (0.22-0.38) 0.38 (0.29-0.47) .02 .001 .18

End point proportion 0.55 (0.43-0.66) 0.53 (0.43-0.63) 0.53 (0.41-0.65)

Growth 0.38 0.24 0.16 44%, .08, 0.44 65%, .02, 0.65 37%, .38, 0.21

Condom use

Baseline proportion§ 0.47 (0.34-0.61)# 0.49 (0.36-0.61) 0.34 (0.24-0.45) .89 .12 .09

End point proportion 0.65 (0.51-0.77) 0.80 (0.67-0.88) 0.78 (0.66-0.86)

Growth 0.18 0.31 0.44 95%, .28, 0.38 165%, .045, 0.66 35%, .42, 0.28

Combined model (0-60)**

Baseline score 15.65 (0.86)‡ 16.06 (0.77) 19.22 (0.80) .72 .002 .004

End point score 27.33 (1.15) 21.84 (1.09) 21.65 (1.36)

Growth 11.68 (1.41) 5.78 (1.31) 2.43 (1.55) 51%, .002, 0.52 79%, ⬍.001, 0.82 58%, .10, 0.30

(continued)

(0.24),46 sex (0.05),47 and other problem behavior (0.16)48 the side of making the HEC too similar to the SDC, in

prevention programs that address only 1 behavioral do- that the HEC included some of the same skills as the SDC,

main. Schools and communities should be encouraged but with a focus on different behaviors. This means that

to adopt programs that have effects on multiple out- the HEC might have been more effective than a stan-

comes. Public pressure on schools has resulted in school dard placebo-attention condition or than “standard care”

systems being mandated or expected to provide mul- in most schools. If so, this would mean that our re-

tiple prevention programs. Adoption of one effective mul- ported results underestimate the actual effectiveness of

tiple-behavior program would reduce the costs and bur- the SDC and SCI. It might also partially explain the lack

dens on school personnel. It may also lead to reduced of effects detected for girls.

school dropout rates and improved learning.13 Our program effects are of practical significance for

Previous studies suggest that comprehensive pro- public health and education. From a public health per-

grams that address multiple behaviors (like the SDC) and spective, reducing these risk behaviors can decrease mor-

involve families and the community (like the SCI) are bidity and mortality related to these behaviors. For ex-

generally more effective than programs that address single ample, a reduction in the use or carrying of weapons not

behaviors or do not involve families or commu- only can prevent homicides, the leading cause of death

nity.13,36,49,50 Both programs significantly reduced the rate for young African American males, but also can help de-

of increase of multiple risk behaviors for boys. The sig- crease other crimes that impact African American com-

nificantly larger effect found for SCI in the combined be- munities. Reduced drug use and safer sexual practices

haviors analysis (and the generally larger effect sizes for can diminish the substantial morbidity and social prob-

SCI) suggest that the SCI may be even more effective than lems associated with human immunodeficiency virus in-

the SDC in reducing the targeted behaviors. fection, unintended pregnancy, and sexually transmit-

The effects of our programs may be underesti- ted diseases.

mated because of the design of our control condition. We Because the incidence of all measured risk behav-

wanted to design a placebo-attention condition that would iors increased for girls, and no program effects were

involve providing the same amount of attention to stu- found, an obvious question is why. Others have also re-

dents as the SDC and be seen as equally interesting, en- ported sex-specific results for these behaviors.51-54 One

gaging, and helpful by students. We probably erred on possibility is that the targeted behaviors are more diffi-

(REPRINTED) ARCH PEDIATR ADOLESC MED/ VOL 158, APR 2004 WWW.ARCHPEDIATRICS.COM

381

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Table 2. Baseline, End Point, and Growth of Risk Behaviors With P Values From Growth Curve Analysis by Condition and Sex (cont)

Relative Reduction, P Value, Effect Size*

Measure HEC SDC SCI SDC-HEC SCI-HEC SCI-SDC

Girls

(n = 188) (n = 213) (n = 181)

Violence

Baseline score† 2.34 (0.26)‡ 2.16 (0.24) 1.88 (0.25) .60 .21 .44

End point score 6.39 (0.50) 6.97 (0.47) 5.20 (0.57)

Growth 4.05 (0.52) 4.81 (0.49) 3.31 (0.58) .28 .35 .049

Provoking behavior

Baseline score§ 8.72 (0.70)‡ 8.89 (0.67) 9.23 (0.72) .86 .61 .73

End point score 12.77 (0.84) 12.57 (0.79) 11.95 (0.95)

Growth 4.05 (0.95) 3.68 (0.91) 2.73 (1.08) .78 .36 .50

School delinquency

Baseline score† 1.35 (0.19)‡ 1.55 (0.18) 1.50 (0.18) .42 .55 .84

End point score 3.81 (0.30) 3.55 (0.29) 3.50 (0.35)

Growth 2.46 (0.31) 2.00 (0.30) 1.98 (0.34) .27 .30 .98

Substance use

Baseline proportion† 0.21 (0.15-0.28)㛳 0.17 (0.11-0.24) 0.12 (0.08-0.19) .38 .05 .03

End point proportion 0.73 (0.63-0.80) 0.76 (0.67-0.83) 0.60 (0.47-0.72)

Growth 0.52 0.59 0.48 .26 .86 .37

Recent sexual intercourse

Baseline proportion§ 0.05 (0.02-0.09)¶ 0.08 (0.05-0.13) 0.09 (0.05-0.15) .26 .13 .65

End point proportion 0.19 (0.12-0.29) 0.25 (0.18-0.35) 0.18 (0.10-0.30)

Growth 0.14 0.18 0.09 .80 .22 .28

Condom use

Baseline proportion§ 0.18 (0.08-0.36)# 0.19 (0.10-0.34) 0.23 (0.13-0.39) .97 .60 .61

End point proportion 0.86 (0.62-0.96) 0.87 (0.74-0.94) 0.56 (0.36-0.75)

Growth 0.67 0.68 0.33 .91 .08 .03

Combined model (0-60)**

Baseline score 13.87 (0.93)‡ 13.77 (0.88) 13.59 (0.85) .94 .83 .89

End point score 19.86 (1.53) 19.19 (1.38) 19.14 (1.77)

Growth 5.99 (1.77) 5.43 (1.61) 5.54 (1.94) .81 .87 .96

Abbreviations: HEC, health enhancement curriculum; SCI, school/community intervention; SDC, social development curriculum.

*Assessed for baseline and growth in continuous or log odds scale (substance use, recent sexual intercourse, and condom use). Reduction in growth is relative

to comparison group (HEC or SDC). For condom use, increase in growth relative to comparison group (HEC or SDC) is shown. P values are from 2-tailed tests.

Only the P value is shown for girls, as there were no significant program effects. Effect size is the difference in growth between groups divided by the pooled

standard deviation of growth. Effect sizes for substance use, recent sexual intercourse, and condom use are the differences in growth divided by the square root of

2/3. Combined model effect size accounts for covariance between behaviors.

†Baseline at beginning of grade 5. End point at end of grade 8.

‡Mean (SE).

§Baseline at end of grade 6. End point at end of grade 8.

㛳Proportion and 95% confidence interval of students responding yes to any of the 4 substance use items; generalized estimating equation (GEE) regression

models logarithm of cumulative odds, In[p i ⬎ j /(1−p i ⬎ j )], where p i ⬎ j is proportion, with j equal to possible response 0 to 4.

¶Proportion and 95% confidence interval of students reporting recent sexual intercourse; GEE regression models logarithm of odds, In[p/(1−p)], where p is

proportion.

#Proportion and 95% confidence interval of students reporting condom use “all the time”; GEE regression models logarithm of cumulative odds,

In[p i ⬎ j /(1−p i ⬎ j )], where p i ⬎ j is proportion, with j equal to possible response 0 to 4.

**Baseline for each behavior in the combined model is the same as in models of each behavior. Condom use is reverse coded in the combined model.

cult to reduce among girls because they already occur at possible that our male health educators contributed to

lower levels. The fact that the interventions reduced the the observed effects for boys.

frequency of the targeted behaviors for boys down to Another possible explanation for the lack of female

the levels for girls in some cases provides some support effects may be that, like at least one other interven-

for this possibility. Nevertheless, the fact that the inci- tion,51 the SDC did not address the types of aggressive

dence of these behaviors increased for girls is still of behaviors used more by girls, ie, indirect aggressive be-

concern. haviors, such as spreading rumors, and creating friend-

In 2 previous studies, differential effects may have ship alliances for the purpose of revenge.56 In addition,

resulted from program implementers being male; they the SDC did not take into consideration the functions that

may have served as more effective role models for boys violence may provide for girls in high-risk environ-

than girls.51,54 Findings from one review55 suggested ments (ie, presenting a tough persona for protection).57

that programs that provide positive female role models Our study supports evidence that the dominant

might improve intervention effects for girls. However, prevention strategies may work better for boys than

in our study, about equal numbers of classes were girls.58 Although research focusing on sex differences is

taught by men and women. Nevertheless, given the sparse,58 current research is identifying factors that may

relative lack of male teachers in public schools, it is still enhance prevention strategies for young girls. This lit-

(REPRINTED) ARCH PEDIATR ADOLESC MED/ VOL 158, APR 2004 WWW.ARCHPEDIATRICS.COM

382

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

The Aban Aya Investigators What This Study Adds

Brian R. Flay, DPhil, principal investigator, Public Health Most school-based prevention programs are of short du-

and Psychology, University of Illinois at Chicago; Shaf- ration and address only one behavioral domain (eg, sub-

fdeen A. Amuwo, PhD, School of Public Health; Carl C. stance use) or one behavior (eg, smoking). High corre-

Bell, MD, Psychiatry and Public Health, and Commu- lations among risky behaviors suggest the need for

nity Mental Health Council; Michael L. Berbaum, PhD, multibehavior programs, but few have been developed

Methodology Research Core, Health Research and Policy and even fewer have been tested in randomized trials.

Centers; Richard T. Campbell, PhD, Sociology, and Meth- Risky behaviors are particularly problematic for Afri-

odology Research Core, Health Research and Policy Cen- can American youth; however, few school-based pre-

ters; Julia Cowell, RN, PhD, Nursing (now at Rush Uni- vention interventions have been developed for them.

versity, Chicago); Judith Cooksey, MD, Public Health The Aban Aya Youth Project developed a cultur-

(now at University of Maryland, College Park); Barbara ally sensitive classroom curriculum and community pro-

L. Dancy, PhD, Nursing; Sally Graumlich, EdD, Health gram for inner-city African American students (grades

Research and Policy Centers; Donald Hedeker, PhD, Bio- 5-8) that targeted multiple risky behaviors (violence, pro-

statistics, Public Health, and Methodology Research Core, vocative behavior, school delinquency, substance use, and

Health Research and Policy Centers; Robert J. Jagers, PhD, sexual behavior). This study evaluated the curriculum

African American Studies and Psychology (now at Mor- and a combined curriculum plus community interven-

gan State University, Baltimore, Md); Susan R. Levy, PhD, tion in a school-based randomized trial. Results dem-

Public Health; Roberta L. Paikoff, PhD, Psychiatry; In- onstrate that a single curriculum or intervention can have

dru Punwani, DDS, Pediatric Dentistry; Roger P. Weiss- large effects on multiple behaviors, at least for boys, re-

berg, PhD, Psychology. ducing their risky behavior to the levels observed in girls

by the end of grade 8. A lack of effects for girls repli-

cates other investigators’ findings, suggesting an area for

new research.

erature suggests that to be effective for girls, programs

may need to focus more on internal manifestation of

risks and on connectedness to school and family.54,59 In

addition, further studies are warranted to help preven- approach was successful and needs to be adopted by fu-

tion researchers better understand when and how risk ture prevention studies in high-risk schools and com-

factors come into play at the various stages of female de- munities.

velopment so that programs can address these crucial Further analyses are needed to determine whether

variables. the interventions enhanced student bonding with their

A major strength of the SCI program was the strong parents, connection with their heritage, and attachment

partnership that was developed with community orga- to their school and community. Analyses are also needed

nizations, including a community-based mental health to explore the role of mediators (eg, intentions and at-

organization. All stakeholders, including academia, the titudes) in reducing the growth of problem behaviors in

schools, and their communities, had very different African American boys. Finally, further research is needed

strengths and weaknesses that provided challenges as well on why programs like this are ineffective for girls.

as opportunities.59 The community mental health orga-

nization was instrumental in developing collaborative re- Accepted for publication December 4, 2003.

lationships and facilitating implementation of SCI com- This study was one of several funded in 1992 by the

ponents. However, it is not clear that this would be easily Office for Research on Minority Health to conduct research

replicated in other communities because of the amount on the prevention of violence, unsafe sex, and drug use

of coordination required, or worth the additional effort among minority students, administered by the National In-

for what appears to be marginal improvement. stitute for Child Health and Human Development,

Some limitations of this study need to be noted. First, Bethesda, Md, grant U01HD30078 (1992-1997). Grade 8

the number of schools was small. This leads to low sta- data collection and statistical analyses were funded by

tistical power to detect small differences, especially be- grant R01DA11019 from the National Institute on Drug

tween the 2 intervention conditions. However, the sig- Abuse, Bethesda (1998-2003).

nificant effects have clear practical public health and We thank the principals, teachers, students, and par-

educational relevance and application. ents of the Chicago-area schools that participated in the Aban

Second, as expected with a high-risk sample, stu- Aya Youth Project. Without their willing participation, this

dent turnover in study schools was relatively high. This project would not have been possible. We also thank the Com-

led us to adopt program and analytical strategies that in- munity Mental Health Council/Foundation and the many

cluded all students for whom we had 1 or more waves of health education, evaluation, data management (with spe-

data and who received at least some of the program, re- cial thanks to Ling Zou Gurnack, MSc), and other staff who

gardless of how much of the program they received. The worked on the project during the 10 years of its conception,

idea was that the intervention would diffuse through- implementation, and reporting.

out the grade level and affect all students in that cohort. Corresponding author: Brian R. Flay, DPhil, Health

The curriculum was designed so that appropriate re- Research and Policy Centers, University of Illinois at Chi-

view and sequencing of content allowed new students to cago, 850 W Jackson Blvd, Suite 400, Chicago, IL 60607

“catch up” reasonably well. Our results suggest that this (e-mail: bflay@uic.edu).

(REPRINTED) ARCH PEDIATR ADOLESC MED/ VOL 158, APR 2004 WWW.ARCHPEDIATRICS.COM

383

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

A Quest for Equity and Excellence. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers;

REFERENCES 1989:201-208.

30. Hammond WR, Yung B. Psychology’s role in the public health response to as-

1. Herrenkohl T, Maguin E, Hill K, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD, Catalano RF. Develop- saultive violence among young African-American men. Am Psychol. 1993;48:

mental risk factors for youth violence. J Adolesc Health. 2000;26:176-186. 142-154.

2. Dahlberg L. Youth violence in the United States: major trends, risk factors, and 31. Karenga M. The African American Holiday of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family,

prevention approaches. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14:259-272. Community and Culture. Los Angeles, Calif: University of Sankore Press; 1988:

3. Bell C, Jenkins E. Community violence and children on Chicago’s southside. Psy- 143.

chiatry. 1993;56:46-54. 32. Boykin AW, Ellison C. The multiple ecologies of black youth socialization: an Afro-

4. Garbarino J, Kostelny K, Dubrow N. What children can tell us about living in dan- graphic analysis. In: Taylor R, ed. African American Youth Socialization: Their

ger. Am Psychol. 1991;46:376-383. Social and Economic Status in the United States. Westport, Conn: Praeger Pub-

5. Shakoor BH, Chalmers D. Co-victimization of African-American children who wit- lishing; 1995:83-128.

ness violence: effects on cognitive, emotional and behavioral development. J Natl 33. Sussman S. Curriculum development in school-based prevention research. Health

Med Assoc. 1991;83:233-238. Educ Res. 1991;6:339-351.

6. Jenkins E, Bell C. Violence among inner city high school students and post- 34. Friedman J. Empowerment: The Politics of Alternative Development. Cam-

traumatic stress disorder. In: Friedman S, ed. Anxiety Disorders in African Ameri- bridge, Mass: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1992:196.

cans. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Co; 1994:76-88. 35. Fawcett SB, Paine AL, Francisco VT, et al. Promoting health through community

7. Kann L, Kinchen SA, Williams BI, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance— development. In: Glenwick DS, Jason LA, eds. Promoting Health and Mental Health

United States, 1999. MMWR CDC Surveill Summ. 2000;49(5):1-32. in Children, Youth and Families. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Corp; 1993:

8. Kosterman R, Hawkins DJ, Guo J, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. The dynamics of al- 233-255.

cohol and marijuana initiation: patterns and predictors of first use in adoles- 36. Comer J. Educating poor minority children. Sci Am. 1988;259:42-48.

cence. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:360-366. 37. Bell C, Fink P. Psychiatric Aspects of Violence: Understanding Causes and Is-

9. Cherry V, Belgrave FZ, Jones W, et al. NTU: an Africentric approach to sub- sues in Prevention and Treatment. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass Publish-

stance abuse prevention among African American youth. J Prim Prev. 1998;18: ers; 2000:37-47.

319-339. 38. Graham JW, Flay BR, Johnson CA, Hansen WB, Grossman L, Sobel JL. Reliabil-

10. Division of STD Prevention. Tracking the Hidden Epidemics: Trends in STDs in ity of self-report measures of drug use in prevention research: evaluation of the

the United States. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2000. Project SMART questionnaire via the test-retest reliability matrix. J Drug Educ.

Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchstp/dstd/Stats_Trends/Trends2000.pdf. 1984;14:175-193.

11. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in the HIV & AIDS Epi- 39. Hansen W, Johnson AC, Flay B, Graham JW, Sobel J. Affective and social influ-

demic. Atlanta, Ga: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1998. Available ences approaches to the prevention of multiple substance abuse among sev-

at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchstp/od/Trends.htm. enth grade students: results from project SMART. Prev Med. 1988;17:135-154.

12. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National and state-specific preg- 40. Pentz MA, Dwyer JH, MacKinnon DP, et al. A multicommunity trial for primary

nancy rates among adolescents—United States, 1995-1997 [published correc- prevention of adolescent drug abuse: effects on drug use prevalence. JAMA. 1989;

tion appears in MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:672]. MMWR Morb Mor- 261:3259-3266.

tal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:605-611. 41. Uehara E, Chalmers D, Jenkins EJ, Shakoor B. Youth encounters with violence:

13. Flay BR. Positive youth development requires comprehensive health promotion results from the Chicago Community Mental Health Council Violence Screening

programs. Am J Health Behav. 2002;26:407-424. Project. J Black Stud. 1996;26:768-781.

14. Flay BR, Petraitis J. The theory of triadic influence: a new theory of health be- 42. Graham JW, Hofer SM, MacKinnon DP. Maximizing the usefulness of data ob-

havior with implications for preventive interventions. In: Albrecht GS, ed. Ad- tained with planned missing value patterns: an application of maximum likeli-

vances in Medical Sociology, Vol IV: A Reconsideration of Models of Health Be- hood procedures. Multivariate Behav Res. 1996;31:197-218.

havior Change. Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press; 1994:19-44. 43. Bryk A, Raudenbush SW. Hierarchical Linear Models. Newbury Park, Calif: Sage

15. Jessor R, Jessor S. Problem Behavior and Psychosocial Development. New York, Publications; 1992:265.

NY: Academic Press; 1977:281. 44. Diggle PJ, Liang K, Zeger SL. Analysis of Longitudinal Data. New York, NY: Ox-

16. Donovan JE. Problem-behavior theory and the explanation of adolescent mari- ford University Press; 1994.

juana use. J Drug Issues. 1996;2:379-402. 45. Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: our view of the state of the art. Psychol

17. Resnick MD, Bearman P, Blum RW, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm: find- Methods. 2002;7:147-177.

ings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. JAMA. 1997; 46. Tolber N, Stratton HH. Effectiveness of school-based drug prevention pro-

278:823-832. grams: a meta-analysis of the research. J Prim Prev. 1997;10:71-128.

18. Allensworth D, Lawson E, Wyche J. Schools and Health: Our Nation’s Invest- 47. Johnson BT, Carey MP, Marsh KL, Levin KD, Scott-Sheldon LA. Interventions to

ment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1997:498. reduce sexual risk for the human immunodeficiency virus in adolescents, 1985-

19. Kolbe LJ. An essential strategy to improve health and education of Americans. 2000: a research synthesis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:381-388.

Prev Med. 1993;22:544-560. 48. Wilson DB, Gottfredson DC, Najaka SS. School-based prevention of problem be-

20. Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Morrison DM, O’Donnell J, Abbott R, Day LE. The Se- haviors: a meta-analysis. J Quant Criminol. 2001;17:247-272.

attle Social Development Project: effects of the first four years on protective fac- 49. Elliot DS, Tolan P. Youth violence prevention, intervention and social policy: an

tors and problem behaviors. In: McCord J, Tremblay R, eds. Preventing Anti- overview. In: Flannery DJ, Huff CR, eds. Youth Violence, Intervention and Social

Social Behavior: Interventions From Birth Through Adolescence. New York, NY: Policy. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1999:3-46.

Guilford Press; 1992:139-161. 50. Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Kosterman R, Abbott R, Hill KG. Preventing adoles-

21. Piper DL, Moberg D, King R. The Healthy for Life Project: behavioral outcomes. cent health-risk behaviors by strengthening protection during childhood. Arch

J Prim Prev. 2000;21:47-73. Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:226-234.

22. Flay BR, Allred CG, Ordway N. Effects of the Positive Action program on achieve- 51. Farrell A, Meyer A. The effectiveness of a school-based curriculum for reducing

ment and discipline: two matched-control comparisons. Prev Sci. 2001;2:71- violence among urban sixth-grade students. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:979-

89. 984.

23. Derzon J, Wilson SJ, Cunningham CA. The Effectiveness of School-Based Inter- 52. O’Donnell J, Hawkins DJ, Catalano RF, Abbott RD, Day LE. Preventing school

ventions for Preventing and Reducing Violence: Center for Evaluation Research failure, drug use, and delinquency among low-income children: long-term inter-

Methodology. Nashville, Tenn: Center for Evaluation Research Methodology, vention in elementary schools. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1995;65:87-100.

Vanderbilt University; 1999. 53. The National Site Evaluation of High-Risk Youth Programs: Making Prevention

24. Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development. Turning Points: Preparing Ameri- Effective for Adolescent Boys and Girls: Gender Differences in Substance Use

can Youth for the 21st Century: Report of the Task Force on Education of Young and Prevention. Rockville, Md: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Ad-

Adolescents. Washington, DC: Carnegie Council on Adolescent Development; June ministration; 2002. Monograph Series No. 4. DHHS publication SMAA-003375.

1989. 54. Perry CL, Komro KA, Veblen-Mortenson S, et al. A randomized controlled trial of

25. Graham J, Flay B, Johnson CA, et al. Group comparability: a multi attribute util- the middle and junior high school D.A.R.E. and D.A.R.E. Plus programs. Arch

ity measurement approach to the use of random assignment with small num- Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157:178-184.

bers of aggregated units. Eval Rev. 1984;8:247-260. 55. Blake SM, Amaro H, Schwartz P, Flinchbaugh LJ. A review of substance abuse

26. Weissberg RP, Barton HA, Shriver TP. The Social Competence Promotion pro- prevention interventions for young adolescent girls. J Early Adolesc. 2001;21:

gram for young adolescents. In: Albee GW, Gullotta TP, eds. Primary Prevention 294-324.

Works. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 1997:268-290. 56. Lagerspetz K, Bjorkqvist K. Indirect aggression in boys and girls. In: Huessman

27. Levy S, Perhats C, Weeks K, Handler AS, Zhu C, Flay BR. Impact of a school- L, ed. Aggressive Behavior. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1994:131-150.

based AIDS prevention program on risk and protective behavior for newly sexu- 57. Campbell A. Men, Women and Aggression. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1993.

ally active students. J Sch Health. 1995;65:145-151. 58. National Center on Addiction and Substance Abuse. The Formative Years: Path-

28. Williams C, Carter BJ, Eng A. The “Know Your Body” program: a developmental ways to Substance Abuse Among Girls and Young Women Ages 8-22. New York,

approach to health education and disease prevention. Prev Med. 1980;9:371- NY: Columbia University; 2003.

383. 59. Tolan P, Keys C, Chertok F, Jason L. Researching Community Psychology: Is-

29. Hilliard AG III. Reintegration for education: black community involvement with sues of Theory and Methods. Washington, DC: American Psychological Asso-

black students in schools. In: Smith WD, Chunn EW, eds. Black Education: ciation; 1990.

(REPRINTED) ARCH PEDIATR ADOLESC MED/ VOL 158, APR 2004 WWW.ARCHPEDIATRICS.COM

384

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

You might also like

- Development of Oncology and Mental Health - v310% (1)Development of Oncology and Mental Health - v31122 pages

- Child Abuse and Compliance On Child Protection PolNo ratings yetChild Abuse and Compliance On Child Protection Pol8 pages

- A Rights-Based Sexuality Education Curriculum For Adolescents 1-Year Outcomes From A Cluster-Randomized TrialNo ratings yetA Rights-Based Sexuality Education Curriculum For Adolescents 1-Year Outcomes From A Cluster-Randomized Trial8 pages

- Cluver 2020 Parenting Mental Health and EconomiNo ratings yetCluver 2020 Parenting Mental Health and Economi8 pages

- Chinese Adolescents Sexual and Reproductive HealtNo ratings yetChinese Adolescents Sexual and Reproductive Healt10 pages

- Chinese Adolescents' Sexual and Reproductive Health Education: A Quasi-Experimental StudyNo ratings yetChinese Adolescents' Sexual and Reproductive Health Education: A Quasi-Experimental Study10 pages

- 1-s2.0-S1054139X16307352-main Intimate Partner ViolenceNo ratings yet1-s2.0-S1054139X16307352-main Intimate Partner Violence2 pages

- Across Sectionalstudyontheassociationbetweensocialmediaaddictionbodyimageandsocialcomparisonamongyoungadultfilipinowomenaged18 25yearsoldinMetroManilaNo ratings yetAcross Sectionalstudyontheassociationbetweensocialmediaaddictionbodyimageandsocialcomparisonamongyoungadultfilipinowomenaged18 25yearsoldinMetroManila11 pages

- Effects of Bystander Programs On The Prevention of Sexual Assault Among Adolescents and College Students: A Systematic ReviewNo ratings yetEffects of Bystander Programs On The Prevention of Sexual Assault Among Adolescents and College Students: A Systematic Review40 pages

- The Use of Drugs Between University Student and The Relation With Abuse During Childwood and AdolescenceNo ratings yetThe Use of Drugs Between University Student and The Relation With Abuse During Childwood and Adolescence9 pages

- Ajol File Journals - 197 - Articles - 175537 - Submission - Proof - 175537 2341 449087 1 10 20180802No ratings yetAjol File Journals - 197 - Articles - 175537 - Submission - Proof - 175537 2341 449087 1 10 2018080210 pages

- Long Proposal Template For The 2009 NCFR Annual Conference: ProcedureNo ratings yetLong Proposal Template For The 2009 NCFR Annual Conference: Procedure6 pages

- Adult Identity Mentoring: Reducing Sexual Risk For African-American Seventh Grade StudentsNo ratings yetAdult Identity Mentoring: Reducing Sexual Risk For African-American Seventh Grade Students10 pages

- Understanding Bullying: From Research To Practice: Wendy M.CraigNo ratings yetUnderstanding Bullying: From Research To Practice: Wendy M.Craig8 pages

- Guerra Et Al-2011-Child Development PDFNo ratings yetGuerra Et Al-2011-Child Development PDF16 pages

- Bully Prevention Single Subject ResearchNo ratings yetBully Prevention Single Subject Research13 pages

- Widman Et Al 2017 Sexual Assertiveness Skills and Sexual Decision Making in Adolescent Girls Randomized ControlledNo ratings yetWidman Et Al 2017 Sexual Assertiveness Skills and Sexual Decision Making in Adolescent Girls Randomized Controlled7 pages

- Sistematic Review - Homophobic Bullying (2020)No ratings yetSistematic Review - Homophobic Bullying (2020)14 pages

- Engaging Boys and Young Men in The Prevention of Sexual ViolenceNo ratings yetEngaging Boys and Young Men in The Prevention of Sexual Violence72 pages

- Problems Faced by Children in School and Counselors RoleNo ratings yetProblems Faced by Children in School and Counselors Role10 pages

- Association Between Bullying Victimization and Health Risk Behavior in AdolescentsNo ratings yetAssociation Between Bullying Victimization and Health Risk Behavior in Adolescents7 pages

- IJCBNM - Volume 6 - Issue 4 - Pages 285-292No ratings yetIJCBNM - Volume 6 - Issue 4 - Pages 285-2928 pages

- Body Image and Risk Behaviors in Youth With HIVNo ratings yetBody Image and Risk Behaviors in Youth With HIV6 pages

- Risky Sexual Behavior and Associated Factors Among Preparatory School Students in Arsi Negelle Town Oromia, EthiopiaNo ratings yetRisky Sexual Behavior and Associated Factors Among Preparatory School Students in Arsi Negelle Town Oromia, Ethiopia7 pages

- A Systematic Review of Universal Campaigns Targeting Child Physical Abuse PreventionNo ratings yetA Systematic Review of Universal Campaigns Targeting Child Physical Abuse Prevention45 pages

- Parenting Programs For The Prevention of Child Physical Abuse Recurrence: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisNo ratings yetParenting Programs For The Prevention of Child Physical Abuse Recurrence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis15 pages

- A Scoping Review of Anti-Bullying Interventions ReNo ratings yetA Scoping Review of Anti-Bullying Interventions Re16 pages

- Global Prevalence of Past-Year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum EstimatesNo ratings yetGlobal Prevalence of Past-Year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum Estimates15 pages

- Being Silenced Loneliness and Being HeardNo ratings yetBeing Silenced Loneliness and Being Heard18 pages

- Social Determinants of Child Abuse: Evidence of Factors Associated With Maternal Abuse From The Egypt Demographic and Health SurveyNo ratings yetSocial Determinants of Child Abuse: Evidence of Factors Associated With Maternal Abuse From The Egypt Demographic and Health Survey10 pages

- Transforming Truancy: Exploring Factors and Strategies That Impact Truancy Among YouthFrom EverandTransforming Truancy: Exploring Factors and Strategies That Impact Truancy Among YouthNo ratings yet

- Understanding and Addressing Girls’ Aggressive Behaviour Problems: A Focus on RelationshipsFrom EverandUnderstanding and Addressing Girls’ Aggressive Behaviour Problems: A Focus on RelationshipsNo ratings yet

- The Psychological Nature of Bullying and Its Determinants: A Study of Teenagers Living in the Country of GeorgiaFrom EverandThe Psychological Nature of Bullying and Its Determinants: A Study of Teenagers Living in the Country of GeorgiaNo ratings yet

- Child Adoles Ment Health - 2022 - Ma - Review School Based Interventions To Improve Mental Health Literacy and ReduceNo ratings yetChild Adoles Ment Health - 2022 - Ma - Review School Based Interventions To Improve Mental Health Literacy and Reduce11 pages

- HECHO The Incredible Years Teacher Classroom Management ProgramNo ratings yetHECHO The Incredible Years Teacher Classroom Management Program18 pages

- School Based Interventions Targeting Stigma of Mental Illness Systematic ReviewNo ratings yetSchool Based Interventions Targeting Stigma of Mental Illness Systematic Review8 pages

- Systematic Literature Review Example Psychology100% (3)Systematic Literature Review Example Psychology6 pages

- Peter Farrall - Feasibility Studies an Architect's GuideNo ratings yetPeter Farrall - Feasibility Studies an Architect's Guide152 pages

- Case Study: TOPIC: Motivation in Difficult EconomyNo ratings yetCase Study: TOPIC: Motivation in Difficult Economy18 pages

- Understanding Identity Integration: Theoretical, Methodological, and Applied IssuesNo ratings yetUnderstanding Identity Integration: Theoretical, Methodological, and Applied Issues11 pages

- Scitech 101 Course Pack Final Revision Edited 8-11-2021No ratings yetScitech 101 Course Pack Final Revision Edited 8-11-2021111 pages

- Arnold Et Al 2015 Long Term Outcomes of Adhd Academic Achievement and PerformanceNo ratings yetArnold Et Al 2015 Long Term Outcomes of Adhd Academic Achievement and Performance13 pages

- Evacuation Patterns in High Rise Buildings PDFNo ratings yetEvacuation Patterns in High Rise Buildings PDF2 pages

- MCQ Testing of Hypothesis With Correct Answers93% (15)MCQ Testing of Hypothesis With Correct Answers7 pages

- Statistics Sheet III (Probability Distributions)No ratings yetStatistics Sheet III (Probability Distributions)6 pages

- Narrative Study Experience of An Engineer Pursuing Another CareerNo ratings yetNarrative Study Experience of An Engineer Pursuing Another Career33 pages

- Research Methodology and Stats M.ed SPCL Edn Notes For NetajiNo ratings yetResearch Methodology and Stats M.ed SPCL Edn Notes For Netaji286 pages

- Child Abuse and Compliance On Child Protection PolChild Abuse and Compliance On Child Protection Pol

- A Rights-Based Sexuality Education Curriculum For Adolescents 1-Year Outcomes From A Cluster-Randomized TrialA Rights-Based Sexuality Education Curriculum For Adolescents 1-Year Outcomes From A Cluster-Randomized Trial

- Chinese Adolescents' Sexual and Reproductive Health Education: A Quasi-Experimental StudyChinese Adolescents' Sexual and Reproductive Health Education: A Quasi-Experimental Study

- 1-s2.0-S1054139X16307352-main Intimate Partner Violence1-s2.0-S1054139X16307352-main Intimate Partner Violence

- Across Sectionalstudyontheassociationbetweensocialmediaaddictionbodyimageandsocialcomparisonamongyoungadultfilipinowomenaged18 25yearsoldinMetroManilaAcross Sectionalstudyontheassociationbetweensocialmediaaddictionbodyimageandsocialcomparisonamongyoungadultfilipinowomenaged18 25yearsoldinMetroManila

- Effects of Bystander Programs On The Prevention of Sexual Assault Among Adolescents and College Students: A Systematic ReviewEffects of Bystander Programs On The Prevention of Sexual Assault Among Adolescents and College Students: A Systematic Review

- The Use of Drugs Between University Student and The Relation With Abuse During Childwood and AdolescenceThe Use of Drugs Between University Student and The Relation With Abuse During Childwood and Adolescence

- Ajol File Journals - 197 - Articles - 175537 - Submission - Proof - 175537 2341 449087 1 10 20180802Ajol File Journals - 197 - Articles - 175537 - Submission - Proof - 175537 2341 449087 1 10 20180802

- Long Proposal Template For The 2009 NCFR Annual Conference: ProcedureLong Proposal Template For The 2009 NCFR Annual Conference: Procedure

- Adult Identity Mentoring: Reducing Sexual Risk For African-American Seventh Grade StudentsAdult Identity Mentoring: Reducing Sexual Risk For African-American Seventh Grade Students

- Understanding Bullying: From Research To Practice: Wendy M.CraigUnderstanding Bullying: From Research To Practice: Wendy M.Craig

- Widman Et Al 2017 Sexual Assertiveness Skills and Sexual Decision Making in Adolescent Girls Randomized ControlledWidman Et Al 2017 Sexual Assertiveness Skills and Sexual Decision Making in Adolescent Girls Randomized Controlled

- Engaging Boys and Young Men in The Prevention of Sexual ViolenceEngaging Boys and Young Men in The Prevention of Sexual Violence

- Problems Faced by Children in School and Counselors RoleProblems Faced by Children in School and Counselors Role

- Association Between Bullying Victimization and Health Risk Behavior in AdolescentsAssociation Between Bullying Victimization and Health Risk Behavior in Adolescents

- Risky Sexual Behavior and Associated Factors Among Preparatory School Students in Arsi Negelle Town Oromia, EthiopiaRisky Sexual Behavior and Associated Factors Among Preparatory School Students in Arsi Negelle Town Oromia, Ethiopia

- A Systematic Review of Universal Campaigns Targeting Child Physical Abuse PreventionA Systematic Review of Universal Campaigns Targeting Child Physical Abuse Prevention

- Parenting Programs For The Prevention of Child Physical Abuse Recurrence: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisParenting Programs For The Prevention of Child Physical Abuse Recurrence: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

- A Scoping Review of Anti-Bullying Interventions ReA Scoping Review of Anti-Bullying Interventions Re

- Global Prevalence of Past-Year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum EstimatesGlobal Prevalence of Past-Year Violence Against Children: A Systematic Review and Minimum Estimates

- Social Determinants of Child Abuse: Evidence of Factors Associated With Maternal Abuse From The Egypt Demographic and Health SurveySocial Determinants of Child Abuse: Evidence of Factors Associated With Maternal Abuse From The Egypt Demographic and Health Survey

- Transforming Truancy: Exploring Factors and Strategies That Impact Truancy Among YouthFrom EverandTransforming Truancy: Exploring Factors and Strategies That Impact Truancy Among Youth

- Understanding and Addressing Girls’ Aggressive Behaviour Problems: A Focus on RelationshipsFrom EverandUnderstanding and Addressing Girls’ Aggressive Behaviour Problems: A Focus on Relationships

- The Psychological Nature of Bullying and Its Determinants: A Study of Teenagers Living in the Country of GeorgiaFrom EverandThe Psychological Nature of Bullying and Its Determinants: A Study of Teenagers Living in the Country of Georgia

- Child Adoles Ment Health - 2022 - Ma - Review School Based Interventions To Improve Mental Health Literacy and ReduceChild Adoles Ment Health - 2022 - Ma - Review School Based Interventions To Improve Mental Health Literacy and Reduce

- HECHO The Incredible Years Teacher Classroom Management ProgramHECHO The Incredible Years Teacher Classroom Management Program

- School Based Interventions Targeting Stigma of Mental Illness Systematic ReviewSchool Based Interventions Targeting Stigma of Mental Illness Systematic Review

- Peter Farrall - Feasibility Studies an Architect's GuidePeter Farrall - Feasibility Studies an Architect's Guide

- Case Study: TOPIC: Motivation in Difficult EconomyCase Study: TOPIC: Motivation in Difficult Economy

- Understanding Identity Integration: Theoretical, Methodological, and Applied IssuesUnderstanding Identity Integration: Theoretical, Methodological, and Applied Issues

- Scitech 101 Course Pack Final Revision Edited 8-11-2021Scitech 101 Course Pack Final Revision Edited 8-11-2021

- Arnold Et Al 2015 Long Term Outcomes of Adhd Academic Achievement and PerformanceArnold Et Al 2015 Long Term Outcomes of Adhd Academic Achievement and Performance

- Narrative Study Experience of An Engineer Pursuing Another CareerNarrative Study Experience of An Engineer Pursuing Another Career

- Research Methodology and Stats M.ed SPCL Edn Notes For NetajiResearch Methodology and Stats M.ed SPCL Edn Notes For Netaji