Unfair Labor Practices by Employers

Unfair Labor Practices by Employers

Uploaded by

Mhatet Malanum Tagulinao-TongcoCopyright:

Available Formats

Unfair Labor Practices by Employers

Unfair Labor Practices by Employers

Uploaded by

Mhatet Malanum Tagulinao-TongcoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Unfair Labor Practices by Employers

Unfair Labor Practices by Employers

Uploaded by

Mhatet Malanum Tagulinao-TongcoCopyright:

Available Formats

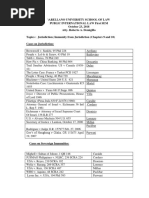

UNFAIR LABOR PRACTICES BY EMPLOYERS Non-Membership or Withdrawal from Union VISAYAN STEVEDORE TRANSPORTATION COMPANY (VISTRANCO) andRAFAEL XAUDARO,

petitioners, vs. CIR, UNITED WORKERS' & FARMERS' ASSN. (UWFA) VENANCIO DANOOG,BUENAVENTURA AGARCIO and 137 others, respondents.G.R. No. L-21696; February 25, 1967; CONCEPCION, C.J. Facts: VISTRANCO is engaged in the loading and unloading of vessels, with a branch office inH i n i g a r a n , N e g r o s O c c i d e n t a l , u n d e r t h e m a n a g e m e n t o f R a f a e l X a u d a r o . I t s w o r k e r s a r e supplied by the United Workers and Farmers Association (UWFA) whose men (affiliated tovarious labor unions) have regularly worked as laborers of the Company during every millingseason since immediately after World War II up to the milling season immediately precedingNovember 11, 1955, when the Company refused to engage the services of Venancio Dano-og,Buenaventura, Agarcio and 137 other persons. At the behest of the UWFA and theComplainants, a complaint for unfair labor practice was, accordingly, filed against the Companyand Xaudaro with the CIR which ruled that the company is guilty of unfair labor practice henceordered the company to ceases and desist from such unfair labor practice and to reinstate thecomplainants with back wages. The said order was affirmed by CIR en banc. Issue: Whether or not VISTRANCO is guilty of unfair labor practice. Held:Yes. The said charge is substantially borne out by the evidence of record, it appearingthat the workers not admitted to work beginning from November, 1955, were precisely thosebelonging to the UWFA and the Mr. Xaudaro, the Company Branch Manager, had told thempoint-blank that severance of their connection with the UWFA was the remedy, if they wanted tocontinue working with the Company.The order and resolution appealed from are hereby affirmed.

Company Domination PROGRESSIVE DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, JORGE L. ARANETA, JUDY A.ROXAS, MANUEL B. JOVER , RAMON LLORENTE and PROGRESSIVEEMPLOYEES UNION, petitioners, vs.

CIR and ARANETA COLISEUM EMPLOYEES ASSN., respondents.G.R. No. L-39546; November 29, 1977; FERNANDEZ, J.: Facts: Araneta Coliseum Employees Association (ACEA) a legitimate labor organization inbehalf of forty-eight (48) members, instituted a case for unfair labor practice in the CIR againstProgressive Development Corporation (PDC), operating the Araneta Coliseum, Jorge Araneta,Judy A. Roxas, Manuel B. Jover and Ramon Llorente, as officers of the corporation PDC andProgressive Employees Union (PEU), a labor organization existing in the PDC. The complaintalleged that the PDC, through its officers, initiated a move to disauthorize the counsel of thecomplainant ACEA from appearing in a union conference with the company; that the supervisorsof PDC encouraged, and assisted in, the formation of the Progressive Employees Union (PEU)and coerced the employees, particularly the individual complainants, to disaffiliate from thecomplainant union and to affiliate with the PEU; that in July and August 1962 the respondents,petitioners herein, discriminated against the individual complainants by either not giving themtheir working schedules, lessening their number of working days and eventually dismissing themfrom their employment, because of their refusal to disaffiliate from their union and join theProgressive Employees Union.T h e C I R r u l e d t h a t t h e c o m p a n y i s g u i l t y o f u n f a i r l a b o r p r a c t i c e h e n c e o r d e r e d t h e company to ceases and desist from such unfair labor practice and to reinstate the complainantswith back wages. Issue: Whether or not petitioners are guilty of unfair labor practice. Held:Yes. From the facts of record, it is clear that the individual complainants were dismissedbecause they refused to resign from the Araneta Coliseum Employees Association and to affiliatewith the Progressive Employees Union which was being aided and abetted by the ProgressiveDevelopment Corporation. There is reason to believe that had the individual complainants agreedto resign from the ACEA and to transfer to the PEU, they would not have been separated fromt h e i r w o r k a n d w o u l d e v e n h a v e b e e n m a d e p e r m a n e n t e m p l o y e e s . P r o g r e s s i v e E m p l o y e e s Union was organized to camouflage the petitioner corporation's dislike for the Araneta ColiseumEmployees Association and to stave off the latter's recognition.The petitioners were correctly found to have committed acts constituting unfair labor practice. Dismissal-Union Activities ZAMBOANGA WOOD PRODUCTS, INC., petitioner, vs. THE NLRC, NATIONAL FEDERATION OF LABOR, DIONISIO ESTIOCA and THESTRIKERS, respondents.G.R. No. L-82088; October 13, 1989; GRINO-AQUINO, J.: Facts: Dionisio Estioca, supervisor of the company and president of the union, NFL posted anannouncement on the bulletin board of the employees' coffee shop

criticizing the Company for having earmarked the sum of P250,000 for the inter-department athletic tournament (which hec a l l e d " a f a r c e a n d baloony") to be held that year, instead of using the money to pay t h e employees' claims for living allowance. He urged the employees to boycott the sports event.S u b s e q u e n t l y h e w a s terminated by the company for loss of trust and confidence i n h i m . Thereafter, the union after filing a notice of strike with the Regional Director of the MOLE inZamboanga City stuck. Meanwhile the company asked the MOLE for arbitration. Estioca filed acomplaint for illegal dismissal with the NLRC. The Minister of Labor certified the labor disputeto the NLRC for compulsory arbitration. In obedience to the Secretary's order, the strikers triedto return to work on August 19, 1982, but were rebuffed by the Company. Backtracking from itsearlier request for compulsory arbitration, the Company filed a motion for reconsideration of theMinister's order on the pretext that there was nothing more to arbitrate because the strikers hadbeen dismissed. When its MR was denied, the Company brought the matter up to SC which ruledthat the company must respect the right of the eighty-one petitioners to resume their respectivepositions as of the time the strike was called. Pursuant thereto the NLRC on September 27, 1988,ordered the Company to readmit the striking employees including those who had been dismissed.The Company alleged that the positions of the dismissed strikers had been filled up.In the meantime, Estioca's complaint for illegal dismissal had also reached the SC.TheSC consolidated the cases and it required the NLRC to hold a formal hearing to determine thelegality of the strike and the dismissal of Estioca and other incidental questions. Complying withthat directive, the NLRC held hearings where evidence were presented by both sides. Later,NLRC reiterated its earlier decision. Issue: Whether or not the company is guilty of unfair labor practice. Held:Yes. Celso Abastillas and Lilio Navarro, Comptroller and Production Manager,respectively called the employees on separate occasions sometime in April 1982 and asked themto withdraw their membership from the union. The company also dismissed Dionisio Estioca,which is too harsh in view of Estioca's subsequent apology for his action in posting a bellicoseannouncement critical of the Company and based on false or erroneous information.Union busting, or interference with the formation of a union, constitutes an unfair labor practice (Art 248, subpar. 4, Labor Code), hence a valid ground for the declaration of a strike.

GENERAL MILLING CORPORATION VS. HON. COURT OF APPEALS G.R. No. 146728. February 11, 2004 Facts: General Milling Corporation employed 190 workers. All the employees were members of a union which is a duly certified bargaining agent. The GMC and the union entered into a collective bargaining agreement which included the issue of representation that is effective for a term of three years which will expire on November 30, 1991. On November 29, 1991, a day before the expiration of the CBA, the union sent GMC a proposed CBA, with a request that a counter proposal be submitted within ten days. on October 1991, GMC received collective and individual letters from the union members stating that they have withdrawn from their union membership. On December 19, 1991, the union disclaimed any massive disaffiliation of its union members. On January 13, 1992, GMC dismissed an employee who is a union member. The union protected the employee and requested GMC to submit to the grievance procedure provided by the CBA, but GMC argued that

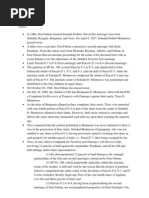

there was no basis to negotiate with a union which is no longer existing. The union then filed a case with the Labor Arbiter but the latter ruled that there must first be a certification election to determine if the union still enjoys the support of the workers. Issue: Whether or not GMC is guilty of unfair labor practice for violating its duty to bargain collectively and/or for interfering with the right of its employees to self-organization. Held: GMC is guilty of unfair labor practice when it refused to negotiate with the union upon its request for the renegotiation of the economic terms of the CBA on November 29, 1991. the unions proposal was submitted within the prescribed 3-year period from the date of effectivity of the CBA. It was obvious that GMC had no valid reason to refuse to negotiate in good faith with the union. The refusal to send counter proposal to the union and to bargain anew on the economic terms of the CBA is tantamount to an unfair labor practice under Article 248 of the Labor Code. Under Article 252 of the Labor Code, both parties are required to perform their mutual obligation to meet and convene promptly and expeditiously in good faith for the purpose of negotiating an agreement. The union lived up to this obligation when it presented proposals for a new CBA to GMC within 3 years from the effectivity of the original CBA. But GMC failed in its duty under Article 252. What it did was to devise a flimsy excuse, by questioning the existence of the union and the status of its membership to prevent any negotiation. It bears stressing that the procedure in collective bargaining prescribed by the Code is mandatory because of the basic interest of the state in ensuring lasting industrial peace. The Court of Appeals found that the letters between February to June, 1993 by 13 union members signifying their resignation from the union clearly indicated that GMC exerted pressure on the employees. We agree with the Court of Appeals conclusion that the ill-timed letters of resignation from the union members indicate that GMC interfered with the right of its employee to selforganization. UNIONS; UNFAIR LABOR PRACTICE; STRIKES; ILLEGAL DISMISSAL STAMFORD MARKETING CORP., ET AL. VS. JOSEPHINE JULIAN, ET AL. G.R. No. 145496. February 24, 2004 Facts: On November 2, 1994, Zoilo de la Cruz, president of the Philippine Agricultural Commercial and Industrial Workers Union (PACIWU-TUCP), sent a letter to Rosario Apacible, treasurer and general manager of Stamford Marketing Corporation, GSP Manufacturing Corporation, Giorgio Antonio Marketing Corporation, Clementine Marketing Corporation and Ultimate Concept Phils., Inc. The letter informed her that the rank-and-file employees of the said companies had formed the Apacible Enterprises Employees Union-PACIWU-TUCP and demanded that it be recognized. After such notice, the following three cases arose: In the First Case, Josephine Julian, president of PACIWU-TUCP, Jacinta Tejada and Jecina Burabod, a Board Member and a member of the said union, were dismissed. They filed a suit with the Labor Arbiter alleging that their employer had not paid them with their overtime pay, holiday pay/premiums, rest day premium, 13th month pay for the year 1994 salaries for services actually rendered, and that illegal deduction had been made without their consent from their salaries for a cash bond. Stamford alleged that the three were dismissed for not reporting for work when required to do so and for not giving notice or explanation when asked. In the Second Case, PACIWU-TUCP filed, on behalf of 50 employees allegedly dismissed illegally for union membership by the petitioners, a case for unfair labor practice against GSP which denied such averments. GSP countered that the BLR did not list Apacible Enterprises Employees Union as a local chapter of PACIWU or TUCP. Thus, the strike that said union organized after the GSP refused to negotiate with them was illegal and that they refused to return to work when asked. The Third Case was filed for claims of the 50 employees dismissed in the second case. Petitioner corporations, however, maintained that they have been paying complainants the wages/salaries mandated by law and that the complaint should be dismissed in view of the execution of quitclaims and waivers by the private respondents. The Labor Arbiter ordered the three cases consolidated as the issues were interrelated and the respondent corporations were under one management.

First Case: The dismissal was illegal and Stamford was ordered to reinstate the complainants as well as pay the backwages and other benefits claimed. It was held that the reassignment and transfer of the complainants were forms of interference in the formation and membership of a union, an unfair labor practice. Stamford also failed to substantiate their claim that the said employees abandoned their employment. It also failed to prove the necessity of the cash deposit of P2,000 and failed to furnish written notice of dismissal to any complainants. Further, it failed to prove payments of the amounts being claimed. Second Case: The strike was illegal and the officers of the union have lost their employment status, thus terminating their employment with GSP. GSP is however ordered to reinstate the complainants who were members of the union without backwages, save some employees specified. It was established that the union was not registered, and thus had staged an illegal strike. The officers of the union should be liable and dismissed, but the members should not, as they acted in good faith in the belief that their actions were within legal bounds. Third Case: GSP was ordered to pay each complainant their claims, as computed by each individual. All other claims were dismissed for lack of merit. The Labor Arbiter found petitioners liable for salary differentials and other monetary claims for petitioners failure to sufficiently prove that it had paid the same to complainants as required by law. It was also ordered to return the cash deposits of the complainants, citing the same reasons as in the First Case. On appeal, the NLRC affirmed the decision in the First and Third Cases, but set aside the judgment of the Second Case for further proceedings in view of the factual issues involved. On May 14, 1996, a Petition to Declare the Strike Illegal was filed which was decided in favor of Stamford, upholding the dismissal of the union officers. The officers made no prior notice to strike, no vote was taken among union members, and the issue involved was non-strikable, a demand for salary increases On elevation to the appellate court, it was ruled that the officers should be given separation pay, and that Jacina Burabod and the rest of the members should be reinstated without loss of seniority, plus backwages. It provided for the payment of the backwages despite the illegality of the strike because the dismissals were done prior to the strike. Such is considered an unfair labor practice as there was lack of due process and valid cause. Thus, the dismissed employees were still entitled to backwages and reinstatement, with exception to the union officers who may be given separation pay due to strained relations with their employers. Issues: (1) Whether or not the respondents union officers and members were validly and legally dismisses from employment considering the illegality of the strike. (2) Whether or not the respondents union officers were entitled to backwages, separation pay and reinstatement, respectively. Held: (1) The termination of the union officers was legal under Article 264 of the Labor Code as the strike conducted was illegal and that illegal acts attended the mass action. Holding a strike is a right that could be availed of by a legitimate labor organization, which the union is not. Also, the mandatory requirements of following the procedures in conducting a strike under paragraph (c) and (f) of Article 263 were not followed by the union officers. Article 264 provides for the consequences of an illegal strike, as well as the distinction between officers and members who participated therein. Knowingly participating in an illegal strike is a sufficient ground to terminate the employment of a union officer but mere participation is not sufficient ground for termination of union members. Thus, absent clear and substantial proof, rankand-file union members may not be terminated. If he is terminated, he is entitled to reinstatement. The Court affirmed the ruling of the CA on the illegal dismissal of the union members, as there was non-observance of due process requirements and union busting by management. It also affirmed that the charge of abandonment against Julian and Tejada were without credence. It reversed the ruling that the dismissal was unfair labor practice as there was nothing on record to show that Julian and Tejada were discouraged from joining any union. The dismissal of the union officers for participation in an illegal strike was upheld. However, union officers also must be given the required notices for terminating employment, and Article 264 of the Labor Code does not authorize immediate dismissal of union officers participating in an illegal strike. No such requisite notices

were given to the union officers. The Court upheld the appellate courts ruling that the union members, for having participated in the strike in good faith and in believing that their actions were within the bound of the law meant only to secure economic benefits for themselves, were illegally dismissed hence entitled to reinstatement and backwages. (2) The Supreme Court declared the dismissal of the union officers as valid hence, the award of separation pay was deleted. However, as sanction for non-compliance with the notice requirements for a lawful termination, backwages were awarded to the union officers computed from the time they were dismissed until the final entry of the judgment.

You might also like

- Industrial Relations in Canada 4th Edition by Fiona McQuarrieDocument481 pagesIndustrial Relations in Canada 4th Edition by Fiona McQuarriekimberlynfrt100% (1)

- Labor Rel Case DigestDocument3 pagesLabor Rel Case DigestRalph JuradoNo ratings yet

- 6.5 Pasagui V VillablancaDocument1 page6.5 Pasagui V VillablancaLyssa TabbuNo ratings yet

- Aquino Vs Pacific PlansDocument3 pagesAquino Vs Pacific PlansPhil JaramilloNo ratings yet

- 3-T PP Vs AcostaDocument2 pages3-T PP Vs AcostaShaine Aira ArellanoNo ratings yet

- St. Michael School of Cavite Inc. v. MasaitoDocument10 pagesSt. Michael School of Cavite Inc. v. Masaitojuju_batugalNo ratings yet

- Rogelio Baronda, Petitioner Vs - Hon. Court of Appeals, and Hideco Sugar Milling Co., Inc., Respondents. G.R. No. 161006 October 14, 2015 FactsDocument5 pagesRogelio Baronda, Petitioner Vs - Hon. Court of Appeals, and Hideco Sugar Milling Co., Inc., Respondents. G.R. No. 161006 October 14, 2015 FactsDyannah Alexa Marie RamachoNo ratings yet

- Labor Law DigestDocument2 pagesLabor Law DigestnorzeNo ratings yet

- Rule 58 (Nos.1-4)Document5 pagesRule 58 (Nos.1-4)Jocelyn B. GuifayaNo ratings yet

- Baguio, Parilla v. PillarDocument6 pagesBaguio, Parilla v. PillarLorenz BaguioNo ratings yet

- Mendoza Vs DizonDocument3 pagesMendoza Vs DizonJan McZeal BandaoNo ratings yet

- T Wu 'An Unjust Enrichment Claim For Mistaken Improvements of LandDocument22 pagesT Wu 'An Unjust Enrichment Claim For Mistaken Improvements of LandTony ZhouNo ratings yet

- Page 3 Syllabus Full Text W DigestDocument227 pagesPage 3 Syllabus Full Text W Digesttwenty19 lawNo ratings yet

- Ang-Abaya v. AngDocument7 pagesAng-Abaya v. AngEnan Inton100% (1)

- Tabas v. CMCDocument12 pagesTabas v. CMCKenneth ManuelNo ratings yet

- Abs CBN V Cta 1981Document1 pageAbs CBN V Cta 1981Frances Ann TevesNo ratings yet

- ALS Policies and Procedures On Academic Integrity and Plagiarism 11-23-18 PDFDocument7 pagesALS Policies and Procedures On Academic Integrity and Plagiarism 11-23-18 PDFArtisticLawyerNo ratings yet

- Contex Vs CirDocument16 pagesContex Vs CirJAMNo ratings yet

- DR. RUBEN C. BARTOLOME, PETITIONER, VDocument2 pagesDR. RUBEN C. BARTOLOME, PETITIONER, Vauslconsti.oneNo ratings yet

- Magallona V ErmitaDocument23 pagesMagallona V ErmitaTacoy DolinaNo ratings yet

- Gaboya v. Cui - UsufructDocument6 pagesGaboya v. Cui - UsufructFiona ShakiraNo ratings yet

- The Heirs of Haberer Vs CADocument1 pageThe Heirs of Haberer Vs CAmamp05No ratings yet

- 24 - Universal Food Corporation Vs CA, 33 Scra 1Document7 pages24 - Universal Food Corporation Vs CA, 33 Scra 1R.A. GregorioNo ratings yet

- 69 Fernandez Hermanos Vs CIRDocument22 pages69 Fernandez Hermanos Vs CIRYaz CarlomanNo ratings yet

- 8 - Catan V NLRCDocument6 pages8 - Catan V NLRCKar EnNo ratings yet

- Property Digests Prefinals (Yu To Edca)Document27 pagesProperty Digests Prefinals (Yu To Edca)Cyrus Vincent Tronco100% (1)

- Spouses Rodrigo Imperial JRDocument3 pagesSpouses Rodrigo Imperial JRNoel Christopher G. BellezaNo ratings yet

- Gonzales vs. CFIDocument4 pagesGonzales vs. CFIBestie BushNo ratings yet

- Frustrated MurderDocument116 pagesFrustrated MurderrizaNo ratings yet

- Case Assignment October 26, Friday Class 2018 First Sem SEMDocument3 pagesCase Assignment October 26, Friday Class 2018 First Sem SEMRobert Ross DulayNo ratings yet

- Maralit Case DigestDocument1 pageMaralit Case DigestKim Andaya-YapNo ratings yet

- Phil. National Bank vs. Vda. de Villarin 66 SCRA 590, September 05, 1975Document8 pagesPhil. National Bank vs. Vda. de Villarin 66 SCRA 590, September 05, 1975Eunice AmbrocioNo ratings yet

- Patricio Bello vs. Eugenia Ubo DigestDocument3 pagesPatricio Bello vs. Eugenia Ubo DigestElla ThoNo ratings yet

- Patalinghug vs. CADocument4 pagesPatalinghug vs. CAjhonadheljacabanNo ratings yet

- Antichresis - SottoDocument2 pagesAntichresis - SottoPia SottoNo ratings yet

- Case DigestsDocument24 pagesCase DigestsMa Nikka Flores OquiasNo ratings yet

- Monteroso Vs CA - DigestDocument3 pagesMonteroso Vs CA - DigestVern Villarica Castillo0% (1)

- 08 Angat Hepp - Motion For Partial Reconsideration 07 November 2012Document10 pages08 Angat Hepp - Motion For Partial Reconsideration 07 November 2012batusay575No ratings yet

- Obillos Vs CIRDocument2 pagesObillos Vs CIRGeorge HabaconNo ratings yet

- Kepco Vs CirDocument1 pageKepco Vs CirMatthew ChandlerNo ratings yet

- Loquias Vs OmbudsmanDocument1 pageLoquias Vs OmbudsmanGillian Caye Geniza BrionesNo ratings yet

- Martin vs. RevillaDocument4 pagesMartin vs. RevillaXsche XscheNo ratings yet

- People V Estibal y Calungsag G R No 208749 November 26 2014Document3 pagesPeople V Estibal y Calungsag G R No 208749 November 26 2014Jappy AlonNo ratings yet

- Radiowealth Finance Company vs. PalileoDocument4 pagesRadiowealth Finance Company vs. PalileoNullus cumunisNo ratings yet

- Carpio V CA (Civil Procedure)Document2 pagesCarpio V CA (Civil Procedure)Jovita Andelescia MagasoNo ratings yet

- People V Villacorta GR NR 186412 September 7, 2011Document11 pagesPeople V Villacorta GR NR 186412 September 7, 2011Mayrll SantosNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 138774 March 8, 2001 Regina Francisco and Zenaida PASCUAL, Petitioners, Aida Francisco-ALFONSO, Respondent. Pardo, J.Document12 pagesG.R. No. 138774 March 8, 2001 Regina Francisco and Zenaida PASCUAL, Petitioners, Aida Francisco-ALFONSO, Respondent. Pardo, J.JuralexNo ratings yet

- 9th WeekDocument6 pages9th WeekStephanie GriarNo ratings yet

- OMB Vs EstrandeDocument3 pagesOMB Vs EstrandeShivaNo ratings yet

- Director of Lands vs. Register of Deeds of RizalDocument2 pagesDirector of Lands vs. Register of Deeds of RizalMay RMNo ratings yet

- 150 in Re Petition For Change of Name of Julian Wong v. CCCRDocument10 pages150 in Re Petition For Change of Name of Julian Wong v. CCCRJoem MendozaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Bill of Rights 1. Republic vs. SandiganbayanDocument15 pagesIntroduction To Bill of Rights 1. Republic vs. SandiganbayanJosel SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Conflicts 4&10Document4 pagesConflicts 4&10Don SumiogNo ratings yet

- PNB v. Intestate Estate of de Guzman DigestDocument3 pagesPNB v. Intestate Estate of de Guzman DigestkathrynmaydevezaNo ratings yet

- Fernandez vs. Dimagiba: Sequitur To Allow Public Policy To Be Evaded On The Pretext of EstoppelDocument2 pagesFernandez vs. Dimagiba: Sequitur To Allow Public Policy To Be Evaded On The Pretext of Estoppelcarlo_tabangcuraNo ratings yet

- TUCP Vs CosculluelaDocument4 pagesTUCP Vs CosculluelaAsHervea AbanteNo ratings yet

- Torts - A19 - Manuel vs. Court of Appeals, 227 SCRA 29 (1993)Document7 pagesTorts - A19 - Manuel vs. Court of Appeals, 227 SCRA 29 (1993)John Paul VillaflorNo ratings yet

- Wills Case Digest MATEODocument13 pagesWills Case Digest MATEOMegan Mateo100% (1)

- 36.02 Ynigo Vs Republic 95 Phil 244Document3 pages36.02 Ynigo Vs Republic 95 Phil 244LalaLanibaNo ratings yet

- Labrel DigestDocument3 pagesLabrel DigestdaphvillegasNo ratings yet

- Group 5 Round 2 ULP DigestDocument11 pagesGroup 5 Round 2 ULP DigestDeurod JoeNo ratings yet

- SRRVDocument25 pagesSRRVMhatet Malanum Tagulinao-TongcoNo ratings yet

- Ladia NotesDocument115 pagesLadia NotesMhatet Malanum Tagulinao-TongcoNo ratings yet

- SRRVDocument25 pagesSRRVMhatet Malanum Tagulinao-TongcoNo ratings yet

- Requirements of A Valid ProxyDocument10 pagesRequirements of A Valid ProxyMhatet Malanum Tagulinao-TongcoNo ratings yet

- The CaseDocument6 pagesThe CaseMhatet Malanum Tagulinao-TongcoNo ratings yet

- What R The Recent Trends in Industrial Relations in India - Employment OpportunitiesDocument9 pagesWhat R The Recent Trends in Industrial Relations in India - Employment OpportunitiesSangram Pradhan0% (2)

- Labrel Art 287 Case DigestsDocument5 pagesLabrel Art 287 Case DigestsRoy DaguioNo ratings yet

- 2.7 Industrial and Employee RelationDocument65 pages2.7 Industrial and Employee RelationadhityakinnoNo ratings yet

- Magic Carpet Airlines Union CaseDocument9 pagesMagic Carpet Airlines Union CasepameladewandaruNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction of Labor ArbitersDocument6 pagesJurisdiction of Labor Arbiterstwenty19 law100% (1)

- ORGANIZATIONAL RESTRUCTURING AND ITS CONSEQUENCES: Rhetorical and StructuralDocument19 pagesORGANIZATIONAL RESTRUCTURING AND ITS CONSEQUENCES: Rhetorical and StructuralSilvio CandidoNo ratings yet

- StaffingDocument141 pagesStaffingRochelle BaticaNo ratings yet

- Escorpizo V University of BaguioDocument8 pagesEscorpizo V University of BaguioMp CasNo ratings yet

- What Is The Works Committee?Document2 pagesWhat Is The Works Committee?Stephen Hickman100% (1)

- Mark Joseph Anthony D. Laus Prof. Leonora Divina Labor Relation and ManagementDocument12 pagesMark Joseph Anthony D. Laus Prof. Leonora Divina Labor Relation and ManagementMark LausNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1: Virtue Ethics - Aristotle: Atomos, or SeedsDocument5 pagesLesson 1: Virtue Ethics - Aristotle: Atomos, or SeedsJustin Paul GallanoNo ratings yet

- Wcms 721934Document2 pagesWcms 721934manisheleenggNo ratings yet

- NLRB Decision Re: NovelisDocument49 pagesNLRB Decision Re: Novelisjdsmith78No ratings yet

- Labor 2 D2019 Finals Reviewer (Daway)Document66 pagesLabor 2 D2019 Finals Reviewer (Daway)JDR JDRNo ratings yet

- 29 G.R. No. 165881 April 19, 2006 Villamaria, JR Vs CADocument9 pages29 G.R. No. 165881 April 19, 2006 Villamaria, JR Vs CArodolfoverdidajrNo ratings yet

- Women Employee Work-Life and Challenges To Industrial Relations: Evidence From North KeralaDocument8 pagesWomen Employee Work-Life and Challenges To Industrial Relations: Evidence From North KeralaInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementNo ratings yet

- Collective Bargaining & Collective AgreementDocument38 pagesCollective Bargaining & Collective Agreementnorsiah_shukeriNo ratings yet

- Human Work Is The Essential Key For Moral and Social DevelopmentDocument45 pagesHuman Work Is The Essential Key For Moral and Social DevelopmentJohn Villacorte CondesNo ratings yet

- Chapter 8 - Human Resource Management Answers: Learning The LanguageDocument13 pagesChapter 8 - Human Resource Management Answers: Learning The LanguageM. MujahidNo ratings yet

- Labour Law ProjectDocument23 pagesLabour Law ProjectMohammad Shaique50% (2)

- Agrarian Law and Social Legislation NotesDocument18 pagesAgrarian Law and Social Legislation Notesmcris101No ratings yet

- Case Digest, Art 82 LCDocument34 pagesCase Digest, Art 82 LCNeapolle FleurNo ratings yet

- Trade Union Movements in IndiaDocument4 pagesTrade Union Movements in IndiaAshwini RaiNo ratings yet

- Gr89894 Ramirez V LaborsecDocument12 pagesGr89894 Ramirez V LaborsecmansikiaboNo ratings yet

- Module-3 Trade Unions: 12/07/21 1 Ir-Mamoria & MamoriaDocument73 pagesModule-3 Trade Unions: 12/07/21 1 Ir-Mamoria & Mamoriaazaruddin_mhmdNo ratings yet

- Time: 3 Hours Maximum Marks: 100 (Weightage 70%)Document5 pagesTime: 3 Hours Maximum Marks: 100 (Weightage 70%)2912manishaNo ratings yet

- Unfair Labor PracticesDocument16 pagesUnfair Labor PracticesMareca DomingoNo ratings yet

- Labor RelationsDocument10 pagesLabor RelationsDyane Garcia-AbayaNo ratings yet

- Farrell DobbsDocument15 pagesFarrell Dobbsjoallan123No ratings yet