BPH, Prostate Cancer, Testicular Cancer

- 1. BPH, Testicular Cancer and Prostate CancerPatrick Carter MPAS, PA-CClinical Medicine IMarch 4, 2011

- 2. Objectives For each of the following diseases describe the etiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, risk factors, signs and symptoms, diagnostic work-up, and treatment:Urethral, penile and scrotal injuriesBenign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH)Testicular cancerProstate cancerCompare and contrast the pathophysiology, clinical presentation, diagnostic work-up and treatment of BPH and prostate cancer

- 3. Urethral, Penile and Scrotal Injuries

- 4. PhimosisInability to retract the foreskinPhysiologic at birthIn 90% of uncircumcised males the foreskin becomes retractable by the age of 3 yearsMay become pathologic from inflammation and scarring at the tip of the foreskinTreatmentCorticosteroid cream to the foreskin three times daily for 1 monthAfter age 10, circumcision is recommended

- 5. Phimosis

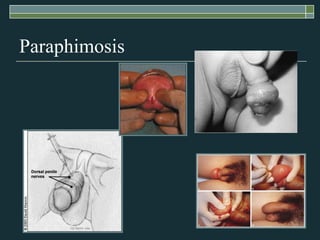

- 6. ParaphimosisForeskin is retracted behind the coronal sulcus and cannot be pulled back over the glansLeads to painful venous stasis in the retracted foreskin results, with edema leading to severe pain Treatment Lubrication of the foreskin and glans and then compressing the glans and simultaneously placing distal traction on the foreskinIn rare cases, emergency circumcision under general anesthesia is necessary

- 7. Paraphimosis

- 8. Penile FractureTraumatic rupture of the corpus cavernosum, occurs when the tunica albuginea is torn Usually associated with sexual activityPatient may hear a snapping sound and experience localized pain, detumescence, and a slowly progressive penile hematoma

- 10. Penile Fracture

- 11. Penile FractureTreatmentNonsurgical – bed rest and ice packs for 24 to 48 hours followed by local heat and a pressure dressingSurgical (most common) – hematoma is evacuated, torn tunica albuginea is sutured, and a pressure dressing is appliedPrognosis – 10% will experience a permanent deformity, suboptimal coitus, or impaired erections, especially if managed nonoperatively

- 12. Peyronie’s DiseaseAcute phase – pain and inflammation as the plaque is formingMedical therapy with p-aminobenzoic acid, vitamin E, colchicines, or tamoxifen may be modestly successfulChronic phase – pain subsides and the plaque is stableSurgical correction if the curvature interferes with sexual intercourse

- 14. Testicular CancerEssentials of diagnosisMost common neoplasm in men aged 20–35Typical presentation as a patient-identified painless noduleOrchiectomy necessary for diagnosis

- 15. Testicular CancerGeneral ConsiderationsRare (2–3 new cases per 100,000 males in the United States each year)90–95% of all primary testicular tumors are germ cell tumorsSlightly more common on the right than on the left, bilateral in 1–2%

- 16. Testicular CancerGeneral ConsiderationsCause unknown, but increased risk with a history of unilateral or bilateral cryptorchismRisk of malignancy is highest for an intra-abdominal testis (1:20) and 1:80 for an inguinal testis Orchiopexy does not alter the risk in the cryptorchid testis; it does help examination and tumor detection5–10% of testicular tumors occur in the contralateral, normally descended testis

- 17. Testicular CancerSigns and symptomsMost common symptom is painless enlargement of the testisSensation of heavinessAcute testicular pain from intratesticular hemorrhage in ~10%Symptoms relating to metastatic disease in 10%Asymptomatic at presentation in 10%

- 18. Testicular CancerPhysical examination findingsTesticular mass or diffuse enlargement of the testis most commonSecondary hydroceles in 5–10%Supraclavicular adenopathyRetroperitoneal massGynecomastia in 5% of germ cell tumors

- 19. Testicular CancerDifferential DiagnosisEpidermoid cystLaboratory TestsSerum human chorionic gonadotropin, alpha-fetoprotein, and lactate dehydrogenaseLiver function tests

- 21. Testicular CancerImaging StudiesScrotal ultrasoundCT scan of abdomen and pelvisSurgical treatmentRadical orchiectomy by inguinal exploration with early vascular control of the spermatic cord structuresScrotal approaches and open testicular biopsies should be avoided

- 23. Testicular CancerSeminomasStage I and IIa seminomas treated by radical orchiectomy and retroperitoneal irradiation have 5-year disease-free survival rates of 92 - 98%Stage IIb and III seminomas are treated with primary chemotherapyAmong stage III patients, 95% will attain a complete response following orchiectomy and chemotherapy

- 24. Testicular CancerNonseminomasUp to 75% of stage A nonseminomas are cured by orchiectomy aloneModified retroperitoneal lymph node dissections have been designed to preserve the sympathetic innervation required for ejaculation

- 25. Testicular CancerPrognosisPatients with bulky retroperitoneal or disseminated disease treated with primary chemotherapy followed by surgery have a 5-year disease-free survival rate of 55–80%

- 28. Zonal Anatomy

- 29. Constituents of Prostate Fluid

- 30. The Prostate and Aging

- 31. Prostate Calculi

- 32. X-Ray with Extensive Prostatic Calculi

- 33. Transrectal Ultrasound - Prostatic Calculi

- 35. Prostate Size by Age

- 36. Prevalence of BPH with Age

- 37. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaEssentials of diagnosisObstructive or irritative voiding symptomsMay have enlarged prostate on rectal examinationAbsence of urinary tract infection, neurologic disorder, urethral stricture disease, prostatic or bladder malignancy

- 38. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaDefinition = smooth, firm, elastic enlargement of the prostateEtiologyMultifactorialEndocrine: dihydrotestosterone (DHT)Aging

- 39. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaEpidemiologyThe most common benign tumor in menIncidence increases with agePrevalence ~20% in men aged 41–50~50% in men aged 51–60> 90% in men aged 80 and olderSymptoms are also age related: at age 55, ~25% of men report obstructive voiding symptoms

- 40. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaObstructive symptoms HesitancyDecreased force and caliber of streamSensation of incomplete bladder emptyingDouble voiding (urinating a second time within 2 hours)Straining to urinatePostvoid dribbling

- 41. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaIrritative symptoms UrgencyFrequencyNocturiaAmerican Urological Association symptom index

- 42. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaDifferential diagnosisProstate cancerUrinary tract infectionNeurogenic bladderUrethral stricture

- 43. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaDiagnosisPhysical examinationDRE to note size and consistencyFocused neurologic examinationExamine lower abdomen for a distended bladderRenal insufficiency from BPH If possibility of cancer, do serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA), transrectal ultrasound, and biopsy

- 44. PE - Bladder Distention

- 45. Elevated Serum PSAProstate carcinomaGlandular hyperplasia associated with BPHAcute bacterial prostatitis and prostate abscess (transitory)Prostatic infarction (transitory)Manipulation of prostate (transitory)

- 46. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaMedicationsAlpha-blockers PrazosinTerazosin5 alpha-reductase inhibitors FinasterideDutasterideSaw palmetto is of no benefitCombination therapy

- 47. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaIndications for surgeryRefractory urinary retention (failing at least one attempt at catheter removal)Large bladder diverticulaRecurrent urinary tract infectionRecurrent gross hematuriaBladder stonesRenal insufficiency

- 48. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaTypes of surgeryTransurethral resection of the prostate (TURP)Postoperative complications Retrograde ejaculation (75%)Impotence (5–10%)Urinary incontinence (< 1%)

- 49. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaTypes of surgeryTransurethral incision of the prostate (TUIP) Removes the zone of the prostate around the urethra leaving the peripheral portion of the prostate and prostate capsuleLower rate of retrograde ejaculation reported (25%)Open simple prostatectomy when Prostate is too big to remove endoscopically (> 100 g)Bladder stone is present

- 50. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaMinimally invasive approaches TULIP (transurethral laser-induced prostatectomy) under transrectal ultrasound guidanceAdvantages of laser surgery include Outpatient surgeryMinimal blood lossAbility to treat patients while they are receiving anticoagulation therapy

- 51. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaMinimally invasive approaches TULIPDisadvantages of laser surgery include Lack of tissue for pathologic examinationLonger postoperative catheterization timeMore frequent irritative voiding complaintsExpense of laser fibers and generatorsTransurethral needle ablation of the prostate (TUNA)

- 52. Benign Prostatic HyperplasiaOther optionsWatchful waiting: only for patients with mild symptoms (AUA scores 0–7)With watchful waiting, ~10% progress to urinary retention, and half demonstrate marked improvement or resolution of symptomsFollow-UpFollow AUA Symptom Index for BPH

- 53. Prostate Cancer

- 54. Prostate CancerEssentials of DiagnosisProstatic induration on digital rectal examination (DRE) or elevated level of serum prostate-specific antigen (PSA)Most often asymptomaticRarely, systemic symptoms (weight loss, bone pain)

- 55. Prostate CancerGeneral ConsiderationsMost common cancer in American menSecond leading cause of cancer-related death in menAbout 234,500 new cases of prostate cancer, about 27,350 deaths in 2006At autopsy, > 40% of men aged > 50 years have prostate carcinoma, most often occult

- 56. Prostate CancerIncidence increases with ageRisk factors Black raceFamily history of prostate cancerHistory of high dietary fat intakeMajority of prostate cancers are adenocarcinomas

- 57. Prostate CancerSigns and symptomsFocal nodules or areas of induration on DREObstructive voiding symptomsLymph node metastasesLower extremity lymphedemaBack pain or pathologic fracturesRarely, signs of urinary retention or neurologic symptoms as a result of epidural metastases and cord compression

- 58. Prostate Coronal Section - Carcinoma

- 59. Prostate CancerLaboratory testsElevations in serum PSA (normal < 4 ng/mL)PSA correlates with the volume of both benign and malignant prostate tissue18–30% of men with PSA 4.1–10.0 ng/mL have prostate cancerElevations in serum BUN or creatinine in patients with urinary retention or ureteral obstructionElevations in alkaline phosphatase or hypercalcemia in patients with bony metastases

- 60. Prostate CancerImaging StudiesTransrectal ultrasound (TRUS)MRI of the prostateCT imaging to detect regional lymphatic and intra-abdominal metastasesRadionuclide bone scan for PSA level > 20 ng/mL

- 61. Prostate CancerDiagnostic proceduresTRUS-guided biopsy from the apex, mid portion, and base of the prostate Fine-needle aspiration biopsies should be considered in patients at increased risk for bleeding

- 62. Prostate CancerMedicationsAdrenal (adrenal insufficiency, nausea, rash, ataxia)KetoconazoleAminoglutethimideCorticosteroids (prednisone) for gastrointestinal bleeding or fluid retention

- 63. Prostate CancerMedicationsPituitary, hypothalamus (gynecomastia, hot flushes, thromboembolic disease, erectile dysfunction)EstrogensLuteinizing hormone-releasing hormone (LHRH) agonistsAntiandrogens (flutamide)Chemotherapy with Docetaxel

- 64. Prostate CancerTherapeutic proceduresSurveillanceFor minimal capsular penetration, standard irradiation or surgeryFor locally extensive cancers, combination therapy (androgen deprivation combined with surgery or irradiation)For metastatic disease, androgen deprivation

- 65. Prostate CancerTherapeutic proceduresRadical prostatectomy For stages T1 and T2 prostatic cancers, local recurrence is uncommon after radical prostatectomy Adjuvant therapy (radiation for patients with positive surgical margins or androgen deprivation for lymph node metastases)Radiation therapy External beam radiotherapyTransperineal implantation of radioisotopes

- 66. Prostate CancerScreening for prostate cancerScreening tests currently available include DRE, serum PSA, TRUSDetection rates with DRE are low, varying from 1.5% to 7.0%TRUS has low specificity (and therefore high biopsy rate)Elevation of PSA is not specific for cancer, occurs in BPH

- 67. Prostate CancerAge-specific reference ranges for PSA increase specificity For men aged 40–49 years, range is < 2.5 ng/mLFor men 50–59, < 3.5 ng/mLFor men 60–69, < 4.5 ng/mLFor men 70–79, < 6.5 ng/mLLower Ranges for Black Males

- 68. Prostate CancerPSA testing Annually in men with a normal DRE and a PSA > 2.5 ng/mL Biennially in men with a normal DRE and serum PSA < 2.5 ng/mL

- 69. Questions?